Seven & I Holdings: The Empire of Convenience

I. Introduction: The Global Giant & The Hostile Gate

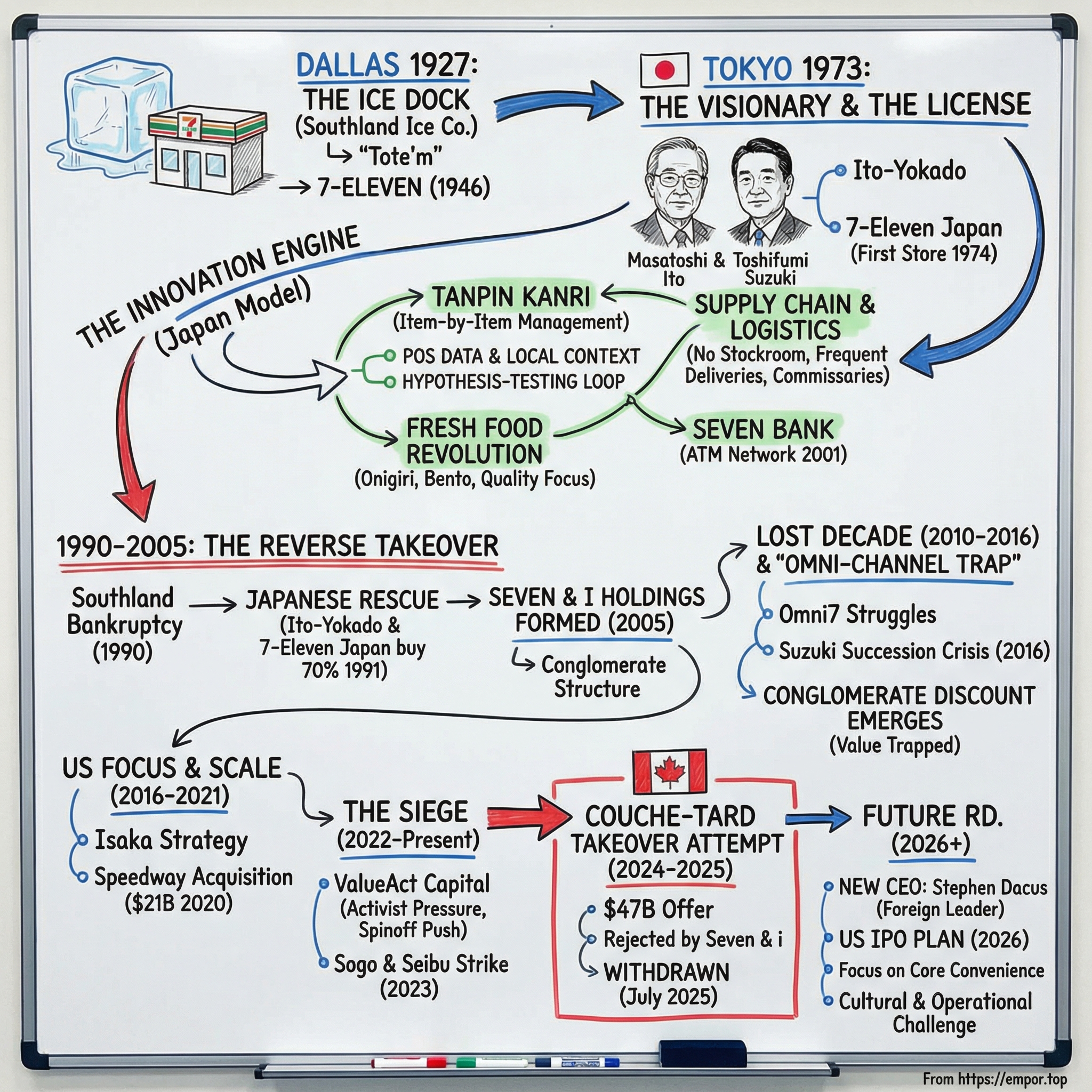

Picture this: July 16, 2025. In a boardroom in Laval, Quebec, executives at Alimentation Couche-Tard—the Canadian giant behind Circle K—hit send on what amounts to a corporate breakup letter.

After nearly a year of courtship, a $47 billion offer, and months of talks that went nowhere, Couche-Tard walked away from what would have been the largest foreign acquisition of a Japanese company in history.

“There has been no sincere or constructive engagement from 7&i that would facilitate the advancement of any proposal, contrary to comments made publicly by 7&i representatives,” the company said.

Tokyo fired back, just as sharply. “7&i confirms that ACT has unilaterally decided to end discussions and withdraw its proposal to acquire the company,” Seven & I responded. “While we are disappointed by ACT’s decision, and disagree with their numerous mischaracterizations, we are not surprised.”

The market didn’t take it well. Seven & I shares dropped hard on the news—down more than 7% on the day, after falling even further earlier in the session. And just like that, the dream scenario died: a combined empire that would have stitched together Circle K’s roughly 16,700 stores with 7-Eleven’s 85,000-plus locations into a single, globe-spanning convenience-store superpower.

But the more interesting question isn’t why this deal collapsed. It’s why it was so hard to do in the first place.

How did a struggling ice dock company in Dallas—an American invention from nearly a century ago—turn into something Japan treats like critical infrastructure? And what happens when the student doesn’t just learn from the master, but so thoroughly outclasses it that the original business becomes inseparable from the student’s culture?

On paper, Seven & I is a sprawling portfolio: convenience stores, superstores, supermarkets, specialty retail, food service, financial services, and IT. In reality, it’s one asset wearing a lot of other assets like weights. Seven & I owns and operates more than 85,000 7-Eleven stores globally, including huge footprints in the U.S. and Canada. Japan alone accounts for nearly a quarter of the world’s 7-Elevens—and Tokyo has thousands of them.

The numbers still don’t quite capture what it feels like on the ground. In Tokyo, you’re never more than a few minutes from a 7-Eleven. And these aren’t the grim, flickering, gas-adjacent boxes many Americans picture. They’re spotless, fast, and obsessively designed around daily life: pay your bills, ship a package, grab cash from an ATM that works with foreign cards, and buy a meal that would embarrass most American fast-casual chains.

That’s why the takeover fight escalated beyond normal M&A.

In August 2024, Seven & I asked to change its legal classification from “non-core” to “core”—a designation that increases government oversight of foreign investment, requiring notification before a foreign buyer can build a stake beyond 10%. Tokyo appeared supportive. A convenience store company was being treated the way countries usually treat defense suppliers or telecom networks.

This is a story about what strategists call Process Power: the kind of moat that comes from operations so disciplined, so culturally embedded, and so systematized that competitors can’t copy them—even when they can see every moving part. It’s also a story about the friction between conglomerate holding-company structures and the brutal clarity of a pure-play retailer. And maybe most intriguingly, it’s a rare attempt at exporting culture backwards—Japanese management trying to teach Americans how to run an American invention.

The thesis is simple, but uncomfortable: Seven & I is both one of the most valuable collections of retail assets on earth and one of the hardest to “unlock.” The Couche-Tard saga was never just about price. It was about whether anyone—foreign or domestic—could actually capture the value trapped inside this uniquely Japanese corporate machine.

II. Origin Story: The Ice Dock & The Japanese Visionary

Dallas, 1927: The Accidental Invention

The story begins with a simple observation in the Texas heat.

In 1927, John Jefferson Green approached Joe C. “Jodie” Thompson, one of the founding directors of the Dallas Southland Ice Company, with an idea that didn’t sound like a revolution. Southland ran ice docks around Dallas—places where people bought blocks of ice to keep food from spoiling. But Green had noticed a pattern: when the docks stayed open a little later, and when they stocked a few basics like bread, milk, and eggs, customers didn’t just show up. They came back.

They weren’t only buying ice. They were buying time.

Southland leaned into it. The early stores were called “Tote’m” stores—because customers would “tote” their purchases away—and some even had totem poles out front as a branding gimmick. Over time, the concept sharpened into something America would recognize instantly: a small footprint, self-service retail, designed around daily needs.

In 1946, Southland renamed the stores 7-Eleven—an advertisement for the expanded hours, 7 a.m. to 11 p.m. At the time, that was radical. Most retailers shut down by late afternoon. 7-Eleven stayed lit, catching the after-work crowd, the late-night snacker, and the early commuter.

The company grew fast. It franchised in 1961. By the 1970s, 7-Eleven was the dominant convenience-store chain in the United States.

And then, in 1973, the model crossed the Pacific.

Tokyo, 1973: The Skeptics and the Visionary

Masatoshi Ito came up in a very different kind of retail.

After World War II, he worked at a small, family-run dry goods shop in Tokyo. When he took over after his older brother died in 1956, the business had just 20 employees. Over the next 15 years, he turned it into a chain of one-stop stores selling everything from groceries to clothing.

Ito wasn’t guessing. In 1961, at age 39, he traveled through the United States and Europe to study modern retail. He came back convinced that Japan’s future wasn’t scattered single-shop operators—it was chains, systems, and scale.

Ito-Yokado, as the business became known, listed on the Tokyo Stock Exchange in 1972. But even then, Ito wasn’t satisfied with superstores alone. On his travels, he’d seen something else: small stores that stayed open late and won by being easy.

The spark came from one of his younger executives: Toshifumi Suzuki.

Suzuki, born in 1932 in Nagano prefecture, graduated from Chuo University in 1956 and joined Ito-Yokado in 1963 after working in publishing sales. By 1971, he was a director—ambitious, persuasive, and constantly searching for the next growth engine.

That mattered, because Japan’s retail landscape was tense. Small shopkeepers had succeeded in imposing legal limits on superstores, squeezing the growth path Ito-Yokado had been riding. So Suzuki went hunting for alternatives. In 1973, he helped license the Denny’s name for Japan, and those repeated trips to the U.S. exposed him to America’s convenience-store boom—especially the category leader in Dallas: 7-Eleven.

Inside Ito-Yokado, the prevailing view was clear: small stores were yesterday’s news. Japan was already blanketed with neighborhood mom-and-pop shops. They were everywhere. Streets were narrow, storage space was limited, and consumers were famously demanding about freshness. To many executives, adding yet another small-format store sounded pointless.

Suzuki heard all that—and saw opportunity.

Japanese consumers were already shopping frequently, often multiple times a day, for small quantities. Homes were smaller, kitchens were tighter, and storage space was scarce. Freshness mattered. Convenience, in Japan, wasn’t about stocking up for the week—it was about solving today.

Suzuki’s key insight was that the mom-and-pop ecosystem wasn’t unbeatable. It was simply entrenched. Many of those stores were undercapitalized, run with outdated management, and at the mercy of distributors and manufacturers. A disciplined chain could win not by being cheaper, but by being reliably better—and by being consistent, every day, in every neighborhood.

He also saw the political angle. Instead of trying to steamroll small shopkeepers, a franchise model could recruit them. Owners could trade independence for security and higher revenues, while the chain gained prime locations and local trust.

Ito-Yokado struck a deal with Southland. In exchange for 0.6 percent of total sales, Southland granted Ito-Yokado exclusive rights throughout Japan. In May 1974, the first Seven-Eleven store opened in Tokyo—launched by Suzuki in the bayside Toyosu district.

What followed wasn’t simple imitation. It was reinvention.

In America, convenience meant longer hours and quick transactions. Suzuki redefined it for Japan as a quality solution: not just open late, but a place you could trust—especially for food—every single day.

The concept took off. Seven-Eleven Japan expanded rapidly: 591 stores by 1979, 2,001 by 1984, and continued growing to 16,086 stores by 2014.

And that’s the twist at the heart of this entire saga: within a decade, the Japanese licensee wasn’t just growing faster than the American parent. It was beginning to outclass it—turning a Dallas invention into a Japanese operating masterpiece.

III. The Secret Sauce: Tanpin Kanri & The Supply Chain

The Philosophy That Changed Everything

Walk into a typical American convenience store around 1990 and you’d often see the same pattern: shelves stuffed with the wrong things, empty slots where the bestsellers should be, tired hot food, and an ordering process that amounted to, “The distributor stops by and tops you up.”

Walk into a Seven-Eleven in Japan in that same era and it felt like a different species of retail.

Suzuki’s big bet wasn’t just “stay open longer” or “add more SKUs.” It was an operating philosophy—fresh merchandise, relentless iteration, and technology used as a weapon. The system that tied it all together had an unglamorous name: Tanpin Kanri.

Tanpin Kanri translates roughly to “item-by-item management.” It sounds like something out of an operations textbook. In practice, it’s the engine that turned Seven-Eleven Japan from a licensee into the highest-grossing retailer in the country.

The twist is who does the managing.

Most chains push ordering decisions down from headquarters. Computers look at historical sales, then auto-generate replenishment. Tanpin Kanri flips that logic. At 7-Eleven Japan, the person making the call is in the store—often a part-time clerk—using POS data plus local context: the weather forecast, a nearby school event, a festival, even whether construction down the street is about to choke off foot traffic.

It’s a hypothesis-testing loop: the employee forms an expectation for demand, places an order, then checks the results and adjusts. Not gut feel—structured experimentation, repeated constantly, product by product.

Suzuki’s view of POS data was also the opposite of what most retailers expect. “POS is not meant for observing popular items,” he argued. “It reveals slow-moving, less successful products.” The goal wasn’t to celebrate winners. It was to expose losers, clear them out, and keep the assortment moving as customer tastes and seasons changed.

In 2003, Seven-Eleven Japan reviewed its sales and concluded that this constant flow—matching supply to demand as it shifted—let it replace and refresh products at an extraordinary pace. Tanpin Kanri was how the stores stayed relevant without ever feeling chaotic.

The Logistics Revolution

Of course, a brilliant ordering system is useless if you can’t actually deliver what the store ordered.

So Seven-Eleven Japan made another radical choice: stores would operate with essentially no stockroom. That sounds risky—until you realize what it forces. If you can’t hide inventory in the back, you have to build a supply chain that hits the store like clockwork.

That’s where Suzuki’s “dominant strategy” came in: saturate a region with stores before expanding outward. Concentration didn’t just build brand presence. It made distribution ruthlessly efficient. Trucks could run dense routes. Fresh items could arrive fast. A single food factory could serve many nearby stores, raising factory productivity while keeping the store shelves constantly replenished.

By the mid-2000s, the system was humming at enormous scale. In 2004, Seven-Eleven Japan recorded 3.6 billion store visits—roughly 986 visits per store per day. Most customers lived within five minutes of a store, and many visited multiple times per week. A meaningful share came in every day.

And when your customers show up daily, freshness isn’t a perk. It’s the whole product.

The Food Revolution

This is where Seven-Eleven Japan stopped looking like “a convenience store chain” and started looking like a food company with a retail network.

The guiding idea was “fast food rooted in Japanese life.” Onigiri, bento, oden—foods that, at the time, were more commonly made at home than bought at a store—became daily staples. But Seven-Eleven didn’t just put them on shelves. It engineered them.

They developed packaging that kept onigiri’s nori crisp until the moment you ate it. They refined bento designs. They built dedicated commissaries and a development machine obsessed with texture, temperature, and how food would hold up over the day.

The results showed up in the economics. By the fiscal year ending February 2005, more than 90% of Ito-Yokado’s consolidated operating profit—211.9 billion yen—was coming from the convenience store business. The stock market was telling the same story: Seven-Eleven Japan’s market value had climbed to roughly 2.39 trillion yen, ahead of Ito-Yokado’s 1.637 trillion yen.

The subsidiary wasn’t just thriving. It was outgrowing—and outshining—the parent.

Seven Bank: Monetizing the Corner

Then Suzuki found another way to turn daily foot traffic into an advantage.

In 2000, Japanese banks were closing branches, squeezed by the country’s long economic slump. That retreat created an opening: people still needed cash, but the infrastructure was shrinking. Seven & I decided to build the infrastructure themselves.

The Financial Services Agency granted a provisional banking license in 2000. The bank launched on April 10, 2001 as IY Bank—named for Ito-Yokado—built around an unusual premise: a bank that operated primarily through a network of ATMs placed inside Seven-Eleven stores (and Ito-Yokado locations), supported by internet-based services.

Takashi Anzai was tasked with making it real: a new kind of banking business built on retail locations instead of branches. It took time. After five years, it had worked off its initial cumulative losses. By its seventh year, Seven Bank’s shares listed on JASDAQ.

The ATM footprint kept spreading—across all 47 prefectures, then outward into train stations and commercial facilities, and even into jointly operated ATM setups with financial institutions. Along the way it captured a meaningful slice of Japan’s ATM market.

The insight was simple: Seven-Eleven didn’t need to win by becoming a traditional bank. It could win by being the most convenient place in the country to access cash—because millions of people were already walking through its doors. By 2022, Seven Bank logged 980 million ATM transactions, making it one of Japan’s biggest ATM networks.

By the end of the 1990s, the story had fully flipped. The Japanese licensee hadn’t just surpassed the American original—it had built a superior machine.

And soon, it would need that machine for something even more dramatic: rescuing the parent company that invented the whole idea.

IV. The Reverse Takeover: The Child Swallows the Parent (1990–2005)

The Collapse in Dallas

In the late 1980s, the Thompson family—the ones who’d built Southland Corporation into America’s convenience-store champion—made a bet that would break the company.

In December 1987, John Philp Thompson Sr., chairman and CEO, led a $5.2 billion management buyout. Then the market cracked. After the 1987 stock crash, the financing got harder, the debt got heavier, and Southland was forced into asset sales just to stay upright. Between 1987 and 1990, it sold off pieces of itself—Chief Auto Parts, the ice division, and hundreds of store locations—anything that could bring in cash and relieve the pressure.

But the leverage was still too much.

In October 1990, after defaulting on $1.8 billion of publicly traded debt, Southland filed a bankruptcy plan of reorganization, with bondholder support lined up. It emerged less than five months later—but the damage was done.

It’s worth sitting with the irony. The company that helped invent modern convenience retail—extended hours, self-service, franchising—wasn’t dying because customers stopped coming. It was collapsing under financial engineering.

Meanwhile, across the Pacific, the licensee was thriving.

The Rescue

After Southland went under, Ito-Yokado and Seven-Eleven Japan stepped in—and they didn’t just help. They took control.

Ito-Yokado announced it had completed a cash purchase of a 70% equity stake in Dallas-based Southland, worth $430 million, framing it as a friendly rescue. When Southland officially exited bankruptcy in March 1991, that same $430 million infusion from Ito-Yokado and Seven-Eleven Japan had rewritten the ownership table: the Japanese entities controlled 70% of the company, while the founding Thompson family held on to 5%.

By then, Ito-Yokado itself was no small player. In 1988, it crossed one trillion yen in sales. And now, with Southland weakened, the Japanese team could do something almost no one would’ve predicted in 1973 when they licensed the brand: they could apply the management discipline they’d built in Japan to the U.S. business and make 7-Eleven profitable again.

This was the moment the center of gravity moved from Dallas to Tokyo. The licensee had become the owner. The student had bought the master.

The symbolism only got clearer with time. In 1999, Southland changed its name to 7-Eleven, Inc., reflecting the divestment of everything that wasn’t the core convenience-store business. Then, in 2005, Seven-Eleven Japan made a tender offer—turning 7-Eleven, Inc. into a wholly owned subsidiary.

The Birth of Seven & I Holdings

With the U.S. parent absorbed, the group turned to a different kind of risk: the market itself.

On April 20, 2005, Ito-Yokado, Seven-Eleven Japan, and Denny’s Japan announced a new structure: a holding company called Seven & I Holdings, effective September 1. The idea was straightforward. Put the major operating companies under one umbrella, consolidate control, and make the whole group harder to pick apart—especially in the face of hostile takeovers.

The irony would take decades to fully reveal itself: the structure designed as a shield would eventually help create the very conditions that invited an attack.

There was also a family dynamic inside the numbers. Ito-Yokado’s performance was declining, while Seven-Eleven Japan was surging. At the time, Ito-Yokado’s market capitalization sat at roughly 70% of Seven-Eleven’s, an uncomfortable imbalance for a group where the “parent” was starting to look like the weaker sibling. The holding-company reset was meant to clean that up. After the restructuring, all three companies became 100% subsidiaries of Seven & I Holdings.

Even the name carried intent. The “I” was for Ito—a tribute to Masatoshi Ito, the honorary chairman.

And Seven & I didn’t stop at defense. It went on offense.

On December 25, 2005, Seven & I moved to merge with Millennium Retailing, owner of the Seibu and Sogo department stores. Simply added together, the two groups’ domestic sales would reach about 5 trillion yen—enough to surpass Japan’s largest retailer at the time, Aeon.

This was empire building: convenience stores, superstores, department stores, restaurants, financial services—all under one roof. It looked, on the surface, like synergy: shared procurement, combined logistics, cross-selling. A retail supergroup built for scale.

What it also created—quietly, but decisively—was complexity. And eventually, a target.

V. The Lost Decade: Identity Crisis & The Omni-Channel Trap (2010–2016)

The Amazon Fantasy

By the early 2010s, Seven & I ran into the same problem that haunted big-box and department-store empires everywhere: the internet was changing how people shopped, and the old playbook didn’t feel like enough.

Their answer came wrapped in a fashionable phrase at the time: “omni-channel retailing.” The pitch was simple and seductive. Seven-Eleven had the densest retail footprint in Japan. What if every store became a pickup point for online orders? What if Seven & I could stitch its supermarkets, department stores, and specialty retailers into one unified digital storefront—eventually branded Omni7—and become Japan’s Amazon?

They started buying the pieces.

On December 4, 2013, Seven & I bought 44.99% of Barneys Japan, a luxury retailer with 10 stores in Japan, including five outlet stores. A month later, on January 29, 2014, Seven & I—through its subsidiary Seven & i Net Media—acquired 50.71% of Nissen Holdings, a long-running catalog and online seller of clothing and daily necessities, plus gift retail and wholesale through stores, catalogs, the internet, and mobile.

On paper, it sounded like a toolkit: Nissen for direct-to-consumer know-how and logistics, Barneys for aspiration, and Seven-Eleven for distribution. In reality, the pieces never clicked. Money went into platforms that didn’t quite deliver, into partnerships that didn’t produce real synergies, and into assets that didn’t naturally belong inside a convenience-store-led ecosystem.

Omni7 became less “Japan’s Amazon” and more a lesson in what happens when technology becomes the plan. Digital didn’t magically fix legacy retail. It just made the weaknesses more expensive.

The Suzuki Succession Drama

As painful as the omni-channel detour was, the deeper shock came from inside the company.

Toshifumi Suzuki wasn’t just another executive. He was the architect of Seven-Eleven Japan—the person who took a U.S. convenience-store concept and rebuilt it into a national habit and a world-class operating system. He’d helped orchestrate the rescue of the American parent. He’d spent decades proving, again and again, that process could beat size.

And then, suddenly, he was out.

In April 2016, Suzuki resigned amid a governance fight that spilled into public view. Activist investor Daniel Loeb, through Third Point, raised concerns about reports that Suzuki was grooming his son, Yasuhiro Suzuki, as a successor. Inside the company, tensions escalated over leadership control and appointments. After the board rejected Suzuki’s proposal to remove the then-president of 7-Eleven Japan, Ryuichi Isaka, Suzuki announced his retirement from active duty. He later became an honorary advisor to Seven & I.

The leadership slate shifted quickly. Ryuichi Isaka became president of Seven & I on May 26, 2016, replacing Noritoshi Murata, who resigned along with Suzuki.

However you interpret the internal politics, the outcome was unmistakable: the “God of Retail” was gone. And with him went the gravitational force that had kept this sprawling group pointed in one direction.

The Conglomerate Discount Emerges

That’s when the numbers started speaking louder than the strategy.

The convenience-store business was the engine: 37.4% of revenue, but 76.1% of operating income. In other words, the part of the company that looked like “just another retailer” from the outside was quietly generating almost all of the profit.

Everything else was harder to defend.

Department stores were struggling. Sogo & Seibu’s flagship Seibu Ikebukuro—Japan’s third-largest department store by sales—sat inside a business that had been in the red for four straight years. The superstores were under pressure from more specialized competitors. And the omni-channel push was consuming resources without producing the breakthrough it promised.

Investors began to see Seven & I for what it had become: a world-class convenience business trapped inside a conglomerate that couldn’t stop carrying underperforming weight. The sum of the parts looked worth more than the whole, and the market price started reflecting that.

ValueAct put it bluntly: “We invested in Seven & i Holdings at an estimated P/E ratio of 11 times, while global peers trade at 15 times to 25 times.”

The structure Masatoshi Ito built to protect the empire was now doing something else. It was creating a discount so persistent, and so visible, that it turned a national champion into an obvious target.

VI. "The American Problem": Speedway & The Quest for Global Scale (2016–2021)

Two Different Animals

Here’s the uncomfortable truth about 7-Eleven as a global brand: there were really two businesses sharing one logo.

In the United States, 7-Eleven had long been seen as a pit stop—cigarettes, beer, gasoline, lottery tickets, and a Big Gulp or Slurpee for the ride. In 2003, more than half of merchandise revenue at 7-Eleven’s 6,361 U.S. outlets came from tobacco and non-alcoholic beverages.

In Japan, the story was the opposite. By February 2005, Seven-Eleven Japan’s 10,826 stores functioned as food centers for busy daily life. This was a place where you grabbed a real meal, not a regret. The stores were clean, the shelves felt deliberate, and the food—onigiri, bento, prepared items—was good enough that customers chose it, not just tolerated it.

The economics followed the culture. Fresh food carries premium margins. Tobacco and fuel don’t. Japanese stores squeezed profit out of every square foot. American stores used fuel to pull cars in and hoped customers bought something inside.

So when Seven & I talked about “global scale,” it was really talking about one thing: fixing America.

The Isaka Strategy: Buying Scale

When Ryuichi Isaka became CEO in 2016, he had a clear theory. The U.S. business didn’t just need better sandwiches—it needed the conditions that made the Japan model possible. Density. Purchasing power. Logistics. Scale.

The first major step came in 2017, when 7-Eleven acquired about 1,100 convenience stores from Sunoco LP for $3.3 billion, strengthening its footprint, especially on the East Coast.

But that wasn’t the real swing.

In August 2020—mid-pandemic—7‑Eleven announced an agreement to buy Speedway, Marathon Petroleum’s convenience-store chain. Roughly 3,900 stores across 35 states. A $21 billion all-cash deal.

Twenty-one billion dollars. For gas stations. In 2020.

“This acquisition is the largest in our company’s history and will allow us to continue to grow and diversify our presence in the U.S., particularly in the Midwest and East Coast,”

VII. The Siege: Activists, Geopolitics & Couche-Tard (2022–Present)

ValueAct Opens the Playbook

The Speedway bet was about scale. But almost immediately, another force showed up with a very different agenda: clarity.

In May 2021, activist investor ValueAct Capital disclosed that it had built a $1.53 billion stake in Seven & i—about 4.4% of the company—and it wasn’t subtle about what it wanted next. In a letter to its own investors, ValueAct argued that Seven & i’s market value didn’t reflect what it actually owned. The reason, in their view, was simple: the company was being priced like a muddled conglomerate, not like the global convenience powerhouse sitting at its center.

ValueAct’s message was that 7-Eleven wasn’t just the best part of the portfolio—it was the portfolio. The hedge fund suggested the convenience-store business could be worth more than double what the parent company was being valued at, if Seven & i restructured itself around 7-Eleven or spun it out entirely.

It also tried to reframe 7-Eleven as something bigger than retail. In the U.S., ValueAct argued, you can point to McDonald’s and Starbucks as exports of American operating excellence. In Spain, Inditex. In Germany, Aldi. Japan, they said, could have that too—if 7-Eleven accelerated digitalization globally, leaned harder into food in the U.S. (because it can be tailored quickly to local tastes), and cut corporate costs.

And then ValueAct put numbers on the thesis. In January, it urged shareholders to push the board toward a spinoff of the 7-Eleven business, arguing it would improve valuation, governance, and ultimately shareholder returns. ValueAct estimated that, over a decade, a full spinoff and capital restructuring could deliver shareholder value roughly 80% higher than keeping the conglomerate intact.

That was the conglomerate discount, quantified—and it landed like a challenge.

The Sogo & Seibu Strike

If ValueAct’s case was analytical, the next chapter was emotional.

Seven & i had already agreed in 2022 to sell its unprofitable department store unit, Sogo & Seibu, to Fortress for about $1.5 billion—right as the Japanese government was proposing new guidelines to encourage M&A. On paper, the sale was rational. The business had been bleeding. Seven & i needed to focus.

But in Japan, restructuring isn’t just numbers on a slide. It’s social fabric. And the sale ripped it.

Workers at Seibu Ikebukuro—one of the country’s most prominent department stores—walked out for a one-day strike after negotiations over the deal collapsed. It was the first strike in that store’s history, and the first major walkout at a Japanese department store since 1962.

Strikes are extremely rare in Japan, where wages and working conditions are typically resolved through quiet compromise. This one made headlines precisely because it felt like a different Japan: louder, tenser, less certain.

The scene was unforgettable. About 900 workers gathered in front of Seibu Ikebukuro holding signs and handing out leaflets. And in the most Japanese detail of all, they apologized to passersby—on camera—for any inconvenience.

The transaction itself also got messier. Fortress was set to close the deal at an enterprise value of roughly ¥220 billion, about ¥30 billion less than the price first announced in November. The sale was completed on September 1, 2023, with reporting later describing a price of JP ¥85 million. After the acquisition, reports said Fortress sold the real estate to Yodobashi Holdings for ¥300 billion.

To the union, the fear was that they weren’t just selling a store—they were selling its identity. Fortress planned to bring in discount electronics retailer Yodobashi Camera as a major tenant, a “shop-in-shop” move the union believed would cheapen the brand and ultimately cost jobs.

For Seven & i, it was a milestone divestiture. For Japan, it was a warning flare: globalization and modern capital markets were starting to change the rules of how corporate change gets done.

Couche-Tard Comes Calling

Then the siege turned external.

In August 2024, Alimentation Couche-Tard—the Canadian convenience-store operator best known for Circle K—launched an attempted takeover of Seven & i worth about $39.9 billion. Seven & i rejected it, saying the proposal “grossly undervalues” the company. The initial offer was $14.86 per share.

A special committee of independent outside directors was formed to evaluate the approach. The board rejected the proposal twice, again citing undervaluation. Couche-Tard came back with more money, raising the bid to $18.19 per share—about $47.2 billion.

This wasn’t just a fight over price. It was a fight over who would control the most strategically important convenience-store platform on earth.

And it triggered a response from inside the company’s own history.

The Ito family, seeing the possibility of losing the empire it helped build, moved to mount a counter-offensive. Seven & i acknowledged receiving a non-binding proposal from Ito-Kogyo, linked to vice president Junro Ito—widely viewed as a white-knight offer, reportedly valued around $58 billion.

For a moment, it looked like the founding family might take the company private.

Then the financing started to wobble. Itochu withdrew from the effort. By February 2025, it decided not to participate, citing limited synergies with Seven & i and an obvious conflict: Itochu’s ownership of FamilyMart, one of 7-Eleven’s biggest rivals in Japan.

Without enough backing, the family’s buyout attempt collapsed. Seven & i shares plunged more than 12% in Tokyo trading, heading for their biggest one-day drop since the holding company was formed in 2005. The failed counterbid didn’t just hurt sentiment—it gave new oxygen to Couche-Tard’s push.

The New CEO and the Withdrawal

Into that pressure cooker, Seven & i made a choice that would have been unthinkable for most of its modern history: it appointed a foreign CEO.

More than two months after announcing its leadership succession plan, Seven & i formally named Stephen Dacus as president and CEO at its annual board meeting, replacing Ryuichi Isaka. At 64, Dacus became the first non-Japanese CEO in the company’s history—taking the job with a Couche-Tard bid still looming and with Seven & i planning a 2026 IPO of 7-Eleven, Inc. in North America.

Dacus had a resume built for multinational execution: his first CEO role in 2001 at MasterFoods, more than eight years at Walmart including senior vice president and CEO of Walmart Japan Holdings, and later leadership at Hana Group SAS.

But he also had something rarer: personal proximity to the brand. His father was a 7-Eleven franchisee, and Dacus worked the midnight shift as a kid. “7-Eleven has always been important in my life,” he said at a March press conference.

He arrived with a transformation plan that sounded like a direct response to the activist critique: pursue an IPO of 7-Eleven, Inc. by the second half of 2026, divest the superstore business, and refocus on the convenience core. Seven & i also signed a definitive agreement to sell its Superstore Business Group to Bain Capital for JPY 814.7 billion (USD 5.37 billion), and committed to return roughly JPY 2 trillion (about USD 13.2 billion) of combined proceeds from the IPO and sale to shareholders through buybacks by FY2030.

And yet, even as Seven & i tried to reset its story, the Couche-Tard negotiations kept grinding—until they didn’t.

In July 2025, Couche-Tard walked away, withdrawing its roughly $47 billion proposal and blaming Seven & i for what it described as a deliberate stall. “As you know, earlier this year we submitted a proposal of ¥2,600 per ordinary share in cash, representing a 47.6% premium to your unaffected stock price,” Couche-Tard wrote. It said that after signing an NDA, there had been “no sincere or constructive engagement,” and that the due diligence allowed—including two tightly constrained management meetings—had been “negligible.”

That’s the kind of line you write when you want the world to believe the other side never intended to sell.

Whether Seven & i was protecting a national treasure, defending a negotiating position, or simply running out the clock is still the central question. And the answer depends entirely on whom you ask.

VIII. Analysis: Power & Forces

Hamilton's 7 Powers Framework

Process Power is Seven & i’s true superpower. Tanpin Kanri—the item-by-item management system that pushes ordering decisions down to the store level—doesn’t live in software. It lives in training, habits, incentives, supplier coordination, and decades of muscle memory. Competitors can study it up close and still fail to reproduce it, because what they’re trying to copy isn’t a tool. It’s a culture.

The fresh-food supply chain turns that culture into something you can taste. In Japan, stores get multiple deliveries a day. Meals come from dedicated commissaries, built around exclusive recipes and constant iteration. The effect is simple: shelves that feel fresh, reliable, and surprisingly high-quality. This isn’t “tech-enabled retail.” It’s operational choreography—tight timing, tight standards, repeated thousands of times a day.

Cornered Resource shows up as density. The “dominant strategy” of saturating an area before moving on created an advantage that compounds: more stores in one neighborhood makes logistics cheaper and faster, which makes freshness easier, which makes each store more attractive, which justifies even more stores. That’s how you get to a world where, in Tokyo, you’re rarely more than a few minutes from a 7-Eleven. It took decades to build—and it’s not something a challenger can conjure with capital alone.

Scale Economies are the lever Seven & i tried to pull in America with Speedway. The acquisition created a North American footprint of roughly 14,000 stores—big enough to rival anyone on purchasing power. But scale is only potential energy. The real question is whether Seven & i can convert that scale into a different operating model—less gas-and-tobacco, more food-and-frequency—without losing what makes convenience stores work in the U.S.

Porter's 5 Forces Analysis

Threat of New Entrants: low in physical stores. Good sites are scarce, buildouts cost money, and the supply chain is hard. But the threat rises sharply from a different angle: quick-commerce and delivery platforms like Gopuff and DoorDash Convenience. They’re not trying to out-7-Eleven 7-Eleven on street corners. They’re trying to redefine “convenient” as speed-to-door instead of distance-to-store.

Industry Rivalry: intense everywhere. In Japan, Lawson (Mitsubishi) and FamilyMart (Itochu) fight on the same turf, with similar playbooks and relentless product cycles. In the U.S., regional players like QuikTrip, Wawa, and Sheetz have built cult-like loyalty by taking food seriously. And nationally, Circle K remains a formidable operator even after its failed run at buying the whole company.

Supplier Power: unusually low, by design. Seven-Eleven Japan doesn’t just buy products—it co-develops them through “Team Merchandising” partnerships, building exclusivity into the assortment. Suppliers benefit from Seven-Eleven’s distribution and volume, which means the leverage tilts toward the retailer, not the manufacturer.

Buyer Power: moderate. Customers can switch instantly—whichever store is closest usually wins. But repeat behavior creates its own kind of lock-in. When a large share of customers visits multiple times per week, the brand isn’t protected by contracts; it’s protected by trust. You don’t have to love 7-Eleven. You just have to believe it won’t disappoint you when you’re hungry and in a hurry.

Threat of Substitutes: rising. Food delivery, supermarket prepared meals, and fast-casual chains are all competing for the same moment: “I need something quick.” Convenience stores keep their place only by staying ahead of that moment—new products, better food, better execution, all the time.

The Conglomerate Tax

The Couche-Tard saga exposed an uncomfortable reality: the holding-company sprawl that was supposed to protect Seven & i helped create the conditions that put it in play. Years of “diworsification” into struggling department stores and other non-core assets weighed down the stock, making the crown jewel look cheaper than it should have.

“Investors may question whether Seven & i is doing all it can to make an ACT bid viable,” analyst Travis Lundy observed.

The underlying tension is easy to describe. If the convenience-store business produces the vast majority of operating income, but the whole company trades at a steep discount to pure-play peers, then value is trapped—not because the core business is broken, but because the structure blurs it. ValueAct’s claim that a spinoff could unlock dramatically higher shareholder value was aggressive, but it wasn’t coming out of nowhere.

The broader takeaway is as old as public markets: structure matters. Even an exceptional business can be undervalued when it’s bundled inside a portfolio that investors don’t trust—or don’t understand.

IX. Playbook: Lessons for Builders & Investors

Lesson 1: Contextual Innovation Beats Imitation

Toshifumi Suzuki didn’t win by copying American 7-Eleven. He won by understanding why convenience stores worked in America, then rebuilding the idea around Japanese life.

Same small footprint. Completely different product. In Japan, the store became a fresh-food machine instead of a packaged-goods shelf. It became a place you could trust for dinner, not a place you ended up when everything else was closed. It became a neighborhood service hub—bills, parcels, ATMs—not just a quick transaction.

The meta-lesson is simple: when you transplant a business model, don’t ask, “What do they do?” Ask, “What job are customers hiring this for?” Then design the local version like you’ve never seen the original.

Lesson 2: The Innovator's Dilemma of Legacy

Seven & I held onto the “prestige” of department stores like Sogo & Seibu and the founding family business, Ito-Yokado, long after the economics stopped working. Those assets weren’t just business units; they were identity. Letting go felt like admitting the past was over.

But legacy doesn’t pay dividends.

The longer the group carried those underperforming businesses, the more it weighed down the stock, muddied the strategy, and widened the conglomerate discount. And when the reckoning finally came, it was sharper. The Sogo & Seibu strike showed the human cost of waiting: change that might have been gradual became abrupt. Earlier divestiture wouldn’t have been painless—but it likely would have been less disruptive.

Lesson 3: Reverse Exporting Is Harder Than It Looks

Here’s the humbling part: even when you perfect a model in Country A, you can’t simply force it onto Country B—even if you own the company in Country B.

Seven-Eleven Japan has spent decades trying to upgrade the American operation. The stores have improved. The food program has gotten better. But the fundamentals still push back: car culture, urban layout, eating habits, and labor dynamics. In Japan, 7-Eleven is built around frequent foot traffic and daily meal solutions. In much of the U.S., convenience is still welded to the fuel pump.

If you’re an operator, this is the warning: cultural context isn’t a layer you add at the end. It’s the operating system your entire business runs on.

Lesson 4: Operational Excellence as Moat

Technology gets the headlines. Tanpin Kanri gets the results.

Getting fresh egg-salad sandwiches to thousands of stores multiple times a day is a harder problem than building an app. The moat is the unsexy stuff: the commissary network, the delivery cadence, the training, the quality control, the feedback loop that turns local demand signals into real product decisions.

For investors, the takeaway is straightforward: the most durable advantage often looks like operations, not invention. When the “secret” is discipline at scale, it’s brutally hard to copy—and it compounds over time.

Key Performance Indicators

If you’re watching Seven & I from the outside, two metrics tell you most of what you need to know:

Same-store sales growth in Japan: This is the pulse of the core machine. Japan is a mature market, so strong growth is rare; flat performance over time is a warning sign that the model is losing relevance.

U.S. operating margin progression: This is the transformation story. If Speedway integration, fresh food, and supply chain investment are working, margins should improve. If they don’t, then scale was bought—but the Japan model still didn’t travel.

X. Conclusion: The Future of the Corner Store

As of January 2026, Seven & I Holdings is standing at a crossroads—and this time, it can’t hide behind the comfort of inertia. The company has laid out an ambitious revised midterm strategy: roughly 1,300 new stores in North America by fiscal 2030, and another 1,000 in Japan.

The Couche-Tard bid collapsed six months ago. The founding family’s buyout never came together. In the wake of that turmoil, Seven & I now has an American CEO, a North American IPO on the calendar, and a stated commitment to simplify the story: focus on convenience, and make the convenience business easier for markets to value.

Dacus has been unusually direct about why the IPO matters—and about what still isn’t working.

“The initial public offering gives us the financial flexibility to invest a bit more aggressively in our stores,” Stephen Dacus said. “How long that takes depends on actual performance, which is unpredictable. It’s a fact that we haven’t yet fully realized 7-Eleven’s potential, and that its performance is still insufficient.”

That’s a striking admission from a sitting CEO: the American operation is, in his words, “insufficient.” The open question is whether Dacus—with his food-industry background, fluent Japanese, and childhood experience working the midnight shift at his father’s 7-Eleven franchise—can bridge the cultural and operational gap that has resisted fixes for decades.

Whatever happens next, the last two years have also made something else clear: Japanese corporate culture remains a formidable barrier for foreign investors trying to force change from the outside. The attempted takeover became a case study in resistance—special committees, boardroom tactics, and political gravity that can bend even the biggest global players off course.

But the real question here is bigger than one failed deal.

What is the future of the corner store in an age of instant delivery, quick-commerce apps, and ghost kitchens? Does physical convenience—being there, on the corner, at 3 a.m. when you need something—still matter when the internet promises to bring everything to your door?

Seven-Eleven Japan suggests the answer is yes, but with a condition: “convenience” can’t just mean proximity. It has to mean quality you can trust. The Japanese model shows that a convenience store can become a place people choose, not a place they settle for.

Whether that model can be exported—to the United States, to Europe, to the world—remains the central unanswered question of Seven & I’s next chapter.

“The 7-Eleven story is amazing and inspiring; we started as a small local ice house and have grown over the years store by store, community by community and country by country,” former CEO Joe DePinto once said.

From an ice dock in Dallas, to a national treasure in Tokyo, to a global empire spanning more than 85,000 stores—the arc is extraordinary. The destination, though, is still unresolved. For students of business history, there are few cleaner case studies in how innovation travels, how culture hardens into process, and how hard it is to modernize a great machine without breaking what made it great.

The corner store, it turns out, is never simple.

Chat with

this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with

this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music