HD Hyundai Heavy Industries: The Shipyard That Built Modern Korea

I. Introduction: A Company Born on an Empty Beach

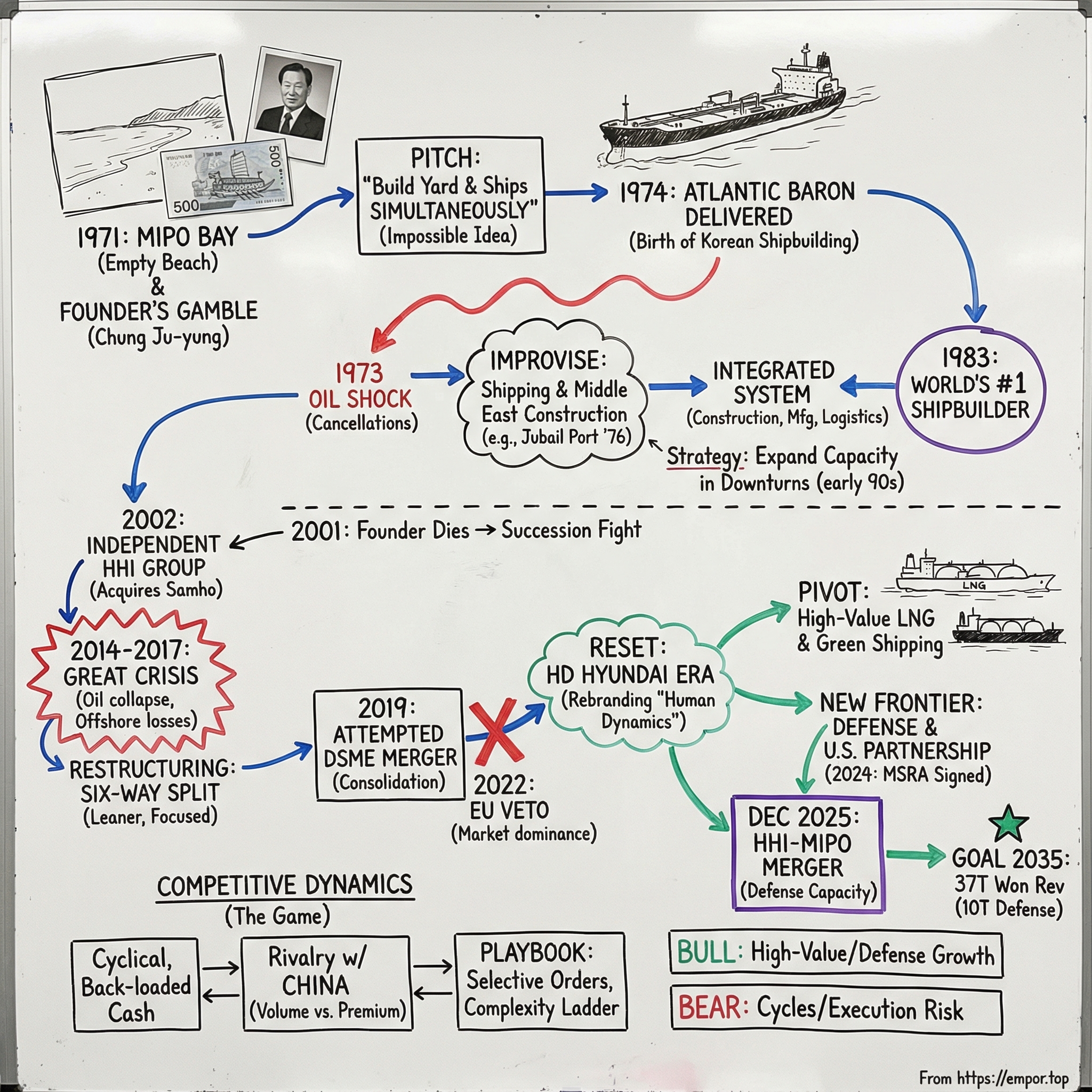

The year was 1971. Picture a windswept strip of sand on Mipo Bay in Ulsan, South Korea. On one side: gray water, rocky edges, and relentless wind. On the other: bare hills and scrub. No pier. No drydock. No cranes. No steel. Nothing—absolutely nothing—that looked like the starting point for what would soon become the largest shipyard on Earth.

And yet, that’s exactly what happened.

The origin story turns on two objects: a 500-won banknote and a photograph. Founder Chung Ju-yung used the bill—printed with the Turtle Ship, Korea’s legendary 16th-century ironclad—and a picture of that empty beach to persuade bankers that Hyundai could build a super-large oil tanker and the shipyard to make it, even though it had no shipbuilding experience, no technology, and no obvious right to win the work. The pitch was so brazen that, at first, European financiers assumed it had to be a stunt.

Fast forward, and the company that started as an impossible idea on a blank shoreline became HD Hyundai Heavy Industries, headquartered in Ulsan—the same place where the sand once was. Its rise isn’t just a corporate success story. It’s one of the clearest business mirrors of South Korea’s own transformation: from postwar hardship to industrial heavyweight.

Scale is part of what makes the story so hard to believe. Beginning with landmark deliveries like the 260,000-ton ultra-large crude oil tanker Atlantic Baron in 1974, HD Hyundai went on to build and deliver thousands of ships for customers around the world. By early 2025, its parent, HD Korea Shipbuilding & Offshore Engineering, reported a massive order backlog—spread across HD Hyundai Heavy Industries, HD Hyundai Mipo Dockyard, and HD Hyundai Samho Heavy Industries.

But this isn’t really a story about tonnage, cranes, or steel. It’s about how a country and a company learned to play the same game: state-directed industrial strategy, entrepreneurial nerve, brutal cycles, labor tension, and global trade that can turn on a single commodity price.

Because the journey doesn’t run in a straight line. There’s a near-death corporate moment in the shipbuilding crisis of 2016. There’s the attempted mega-merger—so logical on paper—that Europe ultimately blocked. And there’s the current reinvention: a pivot toward high-value LNG shipping, defense work, and partnerships with the United States that could define the next half-century.

That sets up the big questions. Can Korean shipbuilders keep their edge as China pushes harder and cheaper? Does “Make American Shipbuilding Great Again” actually translate into profitable work for a Korean champion? And will the merger between HD Hyundai Heavy Industries and HD Hyundai Mipo be remembered as a smart consolidation—or simply the beginning of the next bet?

II. The Founder's Gamble: Chung Ju-yung and the Birth of Korean Shipbuilding (1971-1974)

To understand HD Hyundai Heavy Industries, you have to start with its founder. Chung Ju-yung’s life didn’t begin in boardrooms or shipyards. It began in poverty.

He was born on November 25, 1915, in Tongchon County, Korea—then under Japanese rule (today part of Kangwon Province in North Korea). As a boy, he helped on the family farm and spent time at his grandfather’s Confucian school. On trips into town, he hustled—selling wood to bring money home. Even then, the pattern was clear: Chung didn’t wait for opportunities to arrive. He went looking for them.

At sixteen, he tried to leave the farm life behind. He and a friend set out for Seishin in search of work, trekking roughly 15 miles through the Paechun Valley. They made it as far as Kōgen, where they found construction jobs. They worked for about two months before Chung’s father tracked them down and brought him back. But the attempt mattered. That trip planted something enduring—an interest in building things, and the personal confidence that comes from escaping the path laid out for you, even if only briefly.

And it wasn’t his last attempt.

Chung ran from the farm multiple times, taking whatever work he could find: railway construction, bookkeeping, dock labor. In 1938, he got his first real taste of entrepreneurship by opening a rice store. It didn’t last—Japanese occupation policies forced him to shut it down a year later. After World War II and Korea’s liberation, he found his way into truck repair work for the U.S. Armed Forces.

That repair shop became the seed of everything that followed. Chung later bragged, “We repaired in only five days what took other companies twenty.” It wasn’t just a boast. It was a worldview: move faster, execute cleaner, outwork the assumptions.

In 1947, he founded Hyundai as a construction company. Korea was rebuilding, and Chung intended to build it. Hyundai won major projects, including the Gyeongbu Expressway—high-visibility proof that the company could deliver at national scale.

The Decision to Build Ships

By the early 1970s, Hyundai was South Korea’s largest construction company. For most founders, that would’ve been the destination. For Chung, it was a platform.

South Korea was beginning to muscle into shipbuilding through aggressive state-directed industrial policy. At the time, shipbuilding in traditional centers like Europe and the United States looked tired—high costs, slowing momentum. Seoul saw a rare opening in a capital-intensive industry and leaned in: guarantees for foreign loans, investment in industrial complexes, and a system designed to keep labor costs competitive. Chung, for his part, played a central role in securing technological help and convincing lenders to take Korea seriously.

So when Chung decided Hyundai would enter shipbuilding, it wasn’t because Hyundai was ready. It was because he believed Korea could become ready faster than the world expected.

The problem was obvious. Hyundai had no shipbuilding experience, no shipbuilding technology, and no shipyard. Even the capital wasn’t really there. But Chung treated those as obstacles to be engineered around, not reasons to quit.

The Legendary Sales Pitch

The financing story has become the company’s founding myth for a reason. In 1971, Chung went to England with shipyard plans and a photograph of the empty beach at Mipo Bay—little more than sand and wind, the same blank canvas from the opening of our story. He made his case not with an impressive balance sheet, but with confidence and a symbol: a 500-won bill printed with the Turtle Ship, Korea’s famed 16th-century warship. The message was simple and audacious: Koreans had built great ships before, and they would do it again.

In September 1971, Chung signed a loan agreement with Barclays in the UK for shipyard construction. Hyundai also lined up technical partnerships with A&P Appledore and Scott Lithgow. But there was still one more hurdle: lenders wanted proof there would be real customers.

So Chung did something that sounds insane if you say it out loud—he sold ships before Hyundai had a shipyard.

He secured a contract for two super-large, 260,000-ton oil tankers from Greek shipowner Livanos. The order didn’t just bring credibility. It unlocked the logic of the whole plan: build the shipyard and the ships at the same time. Dig the dock while you assemble the steel. Construct the factory while fulfilling the first customer order.

Building Simultaneously—A Feat Never Attempted

In March 1972, Hyundai broke ground on that empty stretch of Ulsan coastline. The goal was breathtaking: construct what would become the world’s largest shipyard—while simultaneously building two VLCCs for a demanding foreign customer.

Two years later, in 1974, Hyundai held a joint ceremony: dedicate the shipyard and name the two tankers, together, as if this had been the plan all along. The global maritime community took notice because it wasn’t just a delivery. It was a declaration that Korea had entered the industry in the loudest possible way.

The contrast with where Korea started is what makes this moment land. Until then, the largest ship Korea had ever built was a 17,000-dwt cargo ship. The country’s global shipbuilding share was under one percent. Before the 1970s, South Korea had built no ships larger than 10,000 tons.

Hyundai delivered the tankers on time after just 27 months—an unprecedented pace. And with that, Hyundai’s shipbuilding division was born.

If you want the enduring takeaway, it’s not the tonnage. It’s the muscle memory. The company’s culture was forged under extreme constraint: skepticism from abroad, limited domestic experience, brutal timelines, and the need to improvise without blinking. That willingness to attempt what other companies—and other countries—called impossible became part of the organization’s DNA.

III. The Rise to Global Dominance (1974-2000)

The naming ceremony for the Atlantic Baron and Atlantic Baroness in 1974 looked like the start of a clean, upward trajectory. Hyundai had proven it could build a shipyard from nothing and deliver two massive tankers on time. In most industries, that’s the moment you exhale.

In shipbuilding, it’s often the moment the cycle turns.

Surviving the First Oil Shock

Almost immediately, Hyundai ran into the worst possible timing. The 1973 oil crisis slammed the global economy and, with it, global shipping demand. Oil prices jumped, trade slowed, and the logic behind a wave of new supertankers suddenly broke. Around the world, shipowners tried to unwind commitments. Cancellations spread across shipyards that had counted on years of steady work.

Hyundai’s response was pure Chung Ju-yung: don’t retreat, improvise forward.

Instead of treating cancellations as a stop sign, he kept building—even when customers tried to walk away. And to deal with the uncomfortable reality of having ships with no home, Hyundai pushed into shipping itself to absorb that capacity. It was risky and expensive, but it kept the yard active, kept skills developing, and preserved momentum. When the market eventually recovered, Hyundai wasn’t trying to restart an idle machine. It was already running.

The Middle East Strategy

At the same time, Hyundai was building another engine for growth: overseas construction. In the 1970s, Korean construction firms poured into the Middle East in what later became known as the industry’s golden age. Hyundai Engineering & Construction landed one of the era’s defining wins in 1976: a $930 million contract to build an industrial port in Jubail, Saudi Arabia—so large that it was comparable to nearly a quarter of the South Korean government’s annual budget at the time.

Even the upfront payment carried outsized meaning. During a period when the oil shock had tightened global finances, the advance alone—$200 million—was described as about ten times South Korea’s foreign exchange reserves held by the Bank of Korea back then.

Hyundai didn’t win by being the most established name. It won by being the most creatively integrated. Instead of sourcing everything locally or through slow, expensive channels, Hyundai shipped roughly 120,000 tons of materials by sea from Ulsan to Saudi Arabia. That move cut costs and shortened the schedule by about eight months. Jubail went on to earn a reputation in construction circles as one of the “wonders of the world.”

And, more importantly, it set a pattern: Hyundai could combine construction, manufacturing, and maritime logistics into one coordinated system. Competitors might have been good at one piece. Hyundai could pull the whole chain together.

Becoming Number One

By 1983, Hyundai Heavy Industries had become the world’s largest shipbuilder. And it got there with startling speed.

Within ten years of that first VLCC delivery, HHI had delivered 231 vessels and surpassed 10 million deadweight tons of aggregate production in 1984. The pace continued: hundreds more ships by the late 1980s, and by the mid-1990s the cumulative total had climbed dramatically again. In a little over a decade, Hyundai went from a blank beach to the industry’s benchmark.

Exports were the proof. After completing the shipyard in 1974, HHI became the first Korean company to reach $100 million in exports, and it went on to export around 80 percent of its products each year. The yard in Ulsan wasn’t just a factory. It was one of the country’s clearest pipelines to the global economy.

Expansion and Diversification

Hyundai didn’t stop at ships. It pushed outward into offshore plants, machinery, construction equipment, and robotics—moving from “shipbuilder” toward something closer to a full heavy-industries ecosystem.

Crucially, it also kept investing in the core. In the early 1990s, when the shipbuilding industry turned cautious in a downturn, Hyundai expanded anyway. The second yard—anchored by docks No. 8 and 9—came online in 1995. While others consolidated, Hyundai built capacity. When demand rebounded, that extra room to build became leverage.

By the end of this era, Hyundai’s story had become inseparable from modern South Korea’s industrial ascent. Chung Ju-yung was steering a shipbuilding champion even as other Hyundai businesses, like automobiles, were scaling into global players. The formula wasn’t a single breakthrough that competitors couldn’t copy. It was something harder to replicate: relentless execution, close alignment with national industrial strategy, and the willingness to grow precisely when the cycle told everyone else to shrink.

IV. The Hyundai Group Breakup & Independence (2000-2002)

Chung Ju-yung died on March 21, 2001, at age 85. With him went the single gravitational center that had held Hyundai together. What followed wasn’t a tidy handoff. It was one of the most tangled succession fights in modern Korean business—made even more complicated by the sheer scale of what was at stake.

Chung had eight sons and one daughter. And Hyundai by then wasn’t one company so much as an industrial continent: cars, construction, shipping, heavy machinery, finance. When the founder was gone, the question wasn’t simply who would lead. It was what “Hyundai” would even mean.

The Succession Battle

In the early 2000s, Hyundai’s heirs clashed over control. The main struggle played out between the second son, Chung Mong-koo, and the fifth son, Chung Mong-hun. But the move that matters most for this story came from the sixth son, Chung Mong-joon.

He broke away—taking the heavy industries arm with him.

This fragmentation didn’t happen in a vacuum. After the 1997–1998 Asian Financial Crisis, the old model of a tightly intertwined, debt-fueled chaebol was under pressure. Hyundai Motor and affiliate Kia Motors became an independent chaebol, and Hyundai Motor Co. became publicly traded. In the aftermath, Hyundai Motor Co., Hyundai Heavy Industries Co., the Hyundai Group, and other divisions increasingly operated as separate entities.

In other words: the founder’s death accelerated a separation that the crisis years had already made inevitable.

Birth of the Independent HHI Group

By 2002, the break became formal. Hyundai Heavy Industries was spun off from the Hyundai Group and launched as the Hyundai Heavy Industries Group.

That independence came with a tradeoff. On the upside, the heavy industries business could finally steer its own strategy without competing for capital and attention inside a sprawling conglomerate. On the downside, it no longer had the same built-in financial cushion and diversification benefits that come from being part of a wider family empire.

Then, in the same year, HHI moved quickly to bulk up. It acquired Samho Heavy Industries from Halla Group and renamed it Hyundai Samho Heavy Industries. The timing mattered: it added capacity just as shipbuilding was heading into a growth stretch—and it cemented the multi-yard structure that still defines HD Hyundai’s shipbuilding operations today.

For investors and competitors, 2002 was the moment the story snapped into a new shape. Hyundai Heavy Industries was no longer “one powerful division inside Hyundai.” It was now a stand-alone heavy-industries group, with shipbuilding at the center of its identity—and its exposure.

V. The Great Shipbuilding Crisis (2014-2017)

If the founding story was Hyundai’s triumph of audacity, 2015–2016 was the moment that audacity nearly caught up with it. The company didn’t just hit a normal downturn. It ran into a once-in-a-generation pileup: global trade slowed, ship orders dried up, and oil prices collapsed—right when Korean yards had bet heavily on offshore projects tied to the oil boom.

To understand what HD Hyundai would become in the 2020s, you have to sit with how close the shipbuilding champion came to the edge—and what it was willing to do to survive.

The Perfect Storm

By 2016, sentiment was so bleak that for the first time, none of the Korean shipbuilders won a single order in April. From January through May 2016, new contracts for South Korean shipbuilders fell 95% year-on-year.

Losses piled up fast. South Korea’s three largest shipbuilders—Daewoo Shipbuilding & Marine Engineering, Hyundai Heavy Industries, and Samsung Heavy Industries—reported combined losses of W6.4 trillion in 2015 in their offshore plant businesses. They were carrying enormous debt, too: together, the Big Three held $42.1 billion in loans, and they finished 2015 with combined losses of more than $6 billion. For an industry that accounted for about 6.5% of South Korea’s GDP, this wasn’t just a corporate problem. It was a national one.

And underneath the headline numbers was a more uncomfortable diagnosis: too many contracts were priced too low, and capabilities in offshore work weren’t as mature as the bids implied.

The Offshore Plant Disaster

The epicenter of the crisis was offshore oil and gas infrastructure—big, bespoke engineering projects like drillships and FPSOs. During the boom years, Korean yards had charged into the category to capture higher margins than standard merchant ships.

Then oil fell, and the market froze.

With crude prices down, customers canceled or delayed offshore orders, and new demand nearly stopped. Korean shipbuilders were left holding massive projects with thin margins, complex execution risk, and suddenly no forgiving market on the other side. In 2015 alone, HHI and its major peers incurred heavy operating losses—reported at $6.1 billion across the big yards—driven by weak offshore demand and intensifying competition, including from China.

Survival mode kicked in: layoffs, voluntary resignations, executive pay cuts, and asset sales. The goal wasn’t elegance. It was liquidity.

The Human Cost

Restructuring quickly became personal. The Big Three implemented layoffs and pushed voluntary resignations. Hyundai Heavy Industries began cutting office staff in 2015 and planned to extend cuts to factory workers the following year.

This wasn’t a small employment ecosystem. Modern Korean shipbuilding employed more than 200,000 workers, and projections suggested roughly 10% of that workforce could disappear in the next couple of years. The government poured money into supporting the sector—but there was an obvious limit. If demand didn’t return, South Korea couldn’t subsidize its way out forever.

Restructuring: The Six-Way Split

HHI’s answer was as sweeping as it was divisive: a corporate split designed to make the core shipbuilding business lighter, and to separate other operations so they could stand on their own.

Shareholders approved the plan by a 98% margin. The motion carved the company into six separate entities: the shipbuilding business, plus five independent firms spanning electronics, robotics, services, alternative energy, and construction equipment.

Inside the yard, the reaction was furious. The plan affected about 5,000 employees, and union leaders warned it would expose workers to wage cuts and layoffs. Pay negotiations turned toxic: management called for an across-the-board 20% pay cut, while the union argued for a 7% raise. The conflict spilled into the shareholder meeting itself. More than 1,000 union workers tried to disrupt the session, halting proceedings multiple times.

In the end, the split went forward. Hyundai Heavy Industries moved to divide into six firms, including Hyundai Global Service, Hyundai Green Energy, Hyundai Electric, Hyundai Construction Machinery, and Hyundai Robotics. The shipbuilding company—now stripped of much of the non-shipbuilding portfolio—was meant to be slim enough to react quickly to a brutal cycle.

The crisis left a scar that still shapes the company’s instincts. HD Hyundai came out leaner and more focused, with a governance structure built to contain volatility. It also came out with hard-earned skepticism about offshore plant work—and a renewed respect for disciplined order-taking, because in shipbuilding, the wrong contract can be worse than no contract at all.

VI. The Failed DSME Mega-Merger (2019-2022)

After the 2016 crisis, Korean shipbuilding clawed its way back. But the recovery came with an uncomfortable conclusion: Korea still had three “national champions” swinging at the same pool of global orders. In a cyclical industry where pricing discipline is survival, that looked like one competitor too many.

So the next big idea wasn’t a new dock or a new ship type. It was consolidation—the industry trying to fix itself through a deal instead of another round of government triage.

The Consolidation Logic

In 2019, Hyundai Heavy Industries reached an agreement with the Korea Development Bank to acquire Daewoo Shipbuilding & Marine Engineering, better known as DSME—one of the world’s largest shipbuilders and Hyundai’s fiercest domestic rival. To do it, Hyundai created Korea Shipbuilding & Offshore Engineering (KSOE) as an intermediate holding company to sit above the operating yards.

The terms were straightforward, and enormous. Hyundai agreed to buy a 55.7% stake from KDB for 2 trillion won, and pledged an additional 1.5 trillion won capital injection into Daewoo. The pitch to the market was equally clear: fewer Korean yards fighting each other meant less self-inflicted price competition, more scale against China, and a more stable base for the next upcycle.

Daewoo’s backstory made the logic feel even more urgent. Ever since the Daewoo Group collapsed after the 1997 financial crisis, DSME had limped along under restructuring and repeated rescues. Since 2015, it had received roughly $8.8 billion in bailout loans and public funds. The acquisition was meant to end that saga—stabilize capacity, reduce rivalry, and concentrate Korea’s shipbuilding firepower.

The EU Veto

Then the deal ran into the wall that matters most in global industries: regulators outside your home country.

The European Commission rejected the merger, arguing it would reduce competition in the global market for large LNG carriers—exactly the high-value segment Korean yards had leaned into as their strategic answer to cheaper Chinese shipbuilding. The Commission’s view was that a combined DSME-Hyundai would control at least 60% of that market, and Europe, as a major buyer of LNG carriers, would be exposed to higher prices and fewer options.

EU Executive Vice-President Margrethe Vestager framed it in terms of energy security: large LNG carriers are critical to moving LNG around the world, and LNG helps diversify Europe’s energy supply.

The Commission offered a path forward: approve the merger if Hyundai and Daewoo sold off part of their LNG carrier business to bring the combined share below 50%. Hyundai wouldn’t do it. From its perspective, divesting LNG capability—the crown jewel of Korean shipbuilding, and the very reason consolidation was attractive—would hollow out the deal.

Strategic Implications

By the time Europe said no, Hyundai had already secured approvals in places like China, Kazakhstan, and Singapore. It didn’t matter. The EU veto killed the transaction, and the planned reshaping of Korean shipbuilding collapsed with it.

KSOE, however, remained. It still exists as the intermediate holding company overseeing Hyundai Heavy Industries, Hyundai Mipo Dockyard, and Hyundai Samho Heavy Industries—an organizational artifact from a merger that never happened.

The bigger consequence was competitive. Korea stayed at three major players, not two, which meant the industry kept its built-in temptation: win the next order, even if the pricing is ugly. And the battleground wasn’t just conventional tankers and container ships, but the “future” categories too—eco-friendly carriers and autonomous concepts that everyone wanted to lead.

After the failed merger, DSME found a different fate: it was acquired by Hanwha Group and renamed Hanwha Ocean. Since the takeover, Hanwha Ocean has more than doubled its orders compared to 2023.

For investors, the message was blunt. HD Hyundai still had to fight Samsung Heavy Industries and a newly re-energized Hanwha Ocean in a market where pricing power can vanish the moment yards get hungry. And the EU decision made something else clear: even if consolidation makes perfect sense inside Korea, global antitrust scrutiny sets the outer boundary on how the industry can restructure.

VII. Rebirth: The HD Hyundai Era (2022-Present)

When the DSME deal collapsed, HD Hyundai didn’t just shrug and move on. It came out of that episode looking in the mirror: still the world’s biggest shipbuilder, but operating in an industry where pricing power is fragile, China is getting stronger, and regulators can veto your best-laid consolidation plans from thousands of miles away.

So the company did what it often does after a shock. It reset. Internally, leadership framed it as a “second founding”—not because the shipyards were new, but because the mission had to be.

Rebranding and New Identity

In 2022, timed to its 50th anniversary, the group renamed itself from Hyundai Heavy Industries Group to HD Hyundai. “HD” was positioned as shorthand for “Human Dynamics” or “Human Dreams,” a signal that the organization wanted to be seen as more than a shipbuilder—more like a modern industrial tech group with shipbuilding at the core, not the ceiling.

The Pivot to High-Value Vessels & Green Shipping

The comeback wasn’t powered by volume. It was powered by mix.

As LNG and other gas carriers became the industry’s premium product category, HD Hyundai leaned into the high-value end of the order book. By 2025, that shift was showing up clearly in results: in the April–June quarter, the company reported operating profit of 471.5 billion won, up 141% year over year, while revenue rose 6.8% to 4.15 trillion won. Analysts at IBK Securities tied the improvement to LNG carrier orders signed in 2023 that had started flowing into revenue.

Inside the sales mix, gas carriers became the story. Orders secured from 2023 represented 29% of sales at the time, with expectations that the share would climb sharply by year-end. The order backlog—weighted heavily toward gas carriers—covered roughly three years of production, giving the company something shipbuilders crave: visibility.

The broader group numbers told the same tale of recovery and operating leverage. HD Hyundai projected 2024 revenue of 67.7656 trillion won, up 10.5% from the year prior, while operating profit rose 46.8% to 2.9832 trillion won. Within the shipbuilding-and-offshore cluster, performance improved sharply: HD Korea Shipbuilding & Offshore Engineering posted revenue of 25.5386 trillion won, up 19.9%, and operating profit of 1.4341 trillion won, up 408%. HD Hyundai Heavy Industries reported revenue of 14.4865 trillion won and operating profit of 705.2 billion won.

The headline takeaway: after years where the wrong contracts nearly sank the business, HD Hyundai rebuilt momentum by taking the kinds of orders that can actually support profit—especially as the world pushed toward lower-carbon shipping.

Defense Expansion & U.S. Partnership

Then came the next strategic frontier: defense—and, specifically, the United States.

On July 11, 2024, HD Hyundai Heavy Industries became the first Korean company to sign a Master Ship Repair Agreement (MSRA) with the U.S. Naval Supply Systems Command. That agreement matters because it’s the gate pass: without an MSRA, you don’t even get to bid for U.S. Navy maintenance, repair, and overhaul work.

HD Hyundai’s path to that signature wasn’t quick. The company applied in May 2023, went through facility and quality inspections that wrapped in January 2024, then moved through security audits in March and financial audits in May. Along the way, U.S. Secretary of the Navy Carlos Del Toro visited the Ulsan headquarters, where HD Hyundai briefed him on its shipbuilding footprint and technical capabilities. The prize on the other side is substantial: the U.S. Navy’s MRO market has been valued at around 20 trillion won annually.

The timing also wasn’t accidental. The MSRA landed amid a larger political push for South Korea–U.S. shipbuilding cooperation, branded as “Make American Shipbuilding Great Again” (MASGA), backed by a proposed $150 billion initiative.

And HD Hyundai didn’t stop at repair work. It also moved toward deeper industrial cooperation with the U.S. shipbuilding base. HD Hyundai Heavy Industries and Huntington Ingalls Industries (HII) signed an MOU to collaborate on building warships and commercial ships and developing next-generation shipbuilding technologies, with the stated goal of strengthening the maritime industrial base in both countries and opening doors to future U.S. Navy work.

The HHI-Mipo Merger (December 2025)

On Dec. 1, HD Hyundai announced that HD Hyundai Heavy Industries and HD Hyundai Mipo had completed their merger procedures and relaunched as an integrated HD Hyundai Heavy Industries. The company presented it as a landmark moment: a consolidation designed to reinforce its position as the world’s number one shipbuilder and to set a new growth path, including a stated ambition to reach 37 trillion won in revenue by 2035. HD Hyundai Chairman Chung Ki-sun called it “the day when a new chapter in our country’s shipbuilding industry begins.”

Strategically, the logic was defense capacity.

The merger aimed to turn Mipo’s docks into a dedicated base for military vessel production, pairing HD Hyundai Heavy’s warship-building experience with Mipo’s facilities and workforce to accelerate entry into the U.S. naval vessel market. Mipo’s four docks are smaller than HD Hyundai Heavy’s, but they’re built for mid-sized commercial ships—container ships and oil tankers—giving the company a platform that management argued could be repurposed effectively as defense demand rises. The move also came as Mipo faced intensifying competition from Chinese yards, and as MASGA promised fresh momentum for Korea-linked participation in U.S. shipbuilding.

Under the company’s targets, the merged entity aims for 37 trillion won in revenue by 2035, with 10 trillion won expected to come from defense.

VIII. The Business Model & Competitive Dynamics

To understand HD Hyundai’s position today, you have to understand the game it’s playing. Shipbuilding looks like manufacturing. Economically, it behaves more like a long-dated project finance business strapped to one of the most cyclical end markets on Earth.

How Shipbuilding Works

Shipbuilding requires enormous upfront capital, and it runs on a clock that’s painfully slow by normal business standards. From the day a ship is contracted to the day it’s delivered, two to three years can pass. That means the profits you see in any given quarter are often the echo of decisions made years earlier—and the deals signed today won’t show up in earnings for a long time.

By the end of May 2025, HD Hyundai’s backlog stood at 451 vessels, roughly 2.5 years of work. But backlog isn’t the same thing as cash. The industry’s payment pattern is back-loaded: shipbuilders collect progress payments along the way, but a large portion of the money arrives at delivery. If the yard slips, the cash slips with it.

That’s why refund guarantees, or RGs, matter so much. Shipowners pay deposits and progress payments, then ask the shipbuilder to provide an RG—essentially insurance that those payments will be returned if the ship isn’t delivered as promised. And shipowners want those guarantees issued by financial institutions whose credit is as strong as a sovereign rating, which is one reason state-owned financial institutions end up issuing many of them. In this industry, public finance isn’t just a bystander; it’s part of the plumbing. These institutions aren’t only optimizing for standard lending returns—they’re also supporting national industrial competitiveness.

Product Portfolio Today

On the product side, HD Hyundai builds across the major commercial categories: crude oil carriers, LNG carriers, container ships, and more. But the strategic center of gravity has moved. The company has increasingly prioritized high-value, technically demanding vessels—especially LNG carriers—where fewer shipyards can compete, and pricing tends to be more rational.

For 2025, the delivery schedule reflected that mix: LNG carriers and other specialized gas-related ships, alongside a large slate of containerships and crude oil and product tankers. It’s not an accident. As China grows more formidable in standard ship types, South Korea’s broader industry playbook has been to climb the complexity ladder—toward ships that require tighter tolerances, deeper experience, and more specialized know-how.

The China Competition

If there’s one force that sets the strategic temperature for everyone in global shipbuilding, it’s China.

Across the global orderbook, China has captured the dominant share, while South Korea’s slice has shrunk sharply from its early-2000s peak. The fear in Seoul isn’t just that China is building more ships. It’s that China is steadily expanding capacity and pushing into higher-value segments that Korea once treated as protected ground.

The result is a market-share narrative that whipsaws with the cycle. During the 2016 downturn, South Korea fell to 15.5% of the orderbook—an uncomfortable reminder that even world-class yards can go hungry. More recent data has offered a bit of relief: Korea’s share improved in 2025 versus 2024, while China’s eased from the prior year’s highs. Even with total orders down, Korean officials pointed to the shift as evidence that the “high-value focus” strategy can work.

And the monthly order data tells the same story in miniature. South Korea ended 2024 with a brutal month where it captured only a sliver of new orders while China took the lion’s share. Then in January 2025, Korea bounced back into the top spot for new bookings for the first time in months—less a victory lap than a reminder of what matters in this industry: not winning every order, but winning the right ones.

Because for HD Hyundai, the competition with China isn’t just about volume. It’s about where the industry’s profits will live. If China can win the commodity segments, Korea has to own the premium ones—and keep moving the goalposts with greener ships, more complex designs, and capabilities that are hard to replicate at scale.

IX. Playbook: Strategic Lessons & Investment Considerations

Founder's Vision & Audacity

If you strip HD Hyundai’s story down to its essence, it starts with a founder who treated “not ready” as a temporary condition. Chung Ju-yung took orders before he had a yard, built the yard while building the ships, and repeatedly jumped into businesses where Hyundai had no prior right to win.

That origin matters because it didn’t stay in the 1970s. It hardened into a cultural reflex: when the cycle turns or the market shifts, HD Hyundai tends to respond with action and scale, not caution. For investors, the implication is simple: this is a company that’s historically been willing to make big, counter-cyclical bets—sometimes brilliantly, sometimes painfully—rather than play defense.

State-Directed Industrialization

HD Hyundai also can’t be separated from the state strategy that made Korean heavy industry possible. Early on, government-backed financing and loan guarantees helped open doors that a young shipbuilder couldn’t have opened alone. Later, during the 2016 industry crisis, policy support helped keep the shipbuilding base from collapsing under the weight of the downturn. And today, the broader push for South Korea–U.S. shipbuilding cooperation sits in the same lineage: geopolitics and industrial policy shaping commercial opportunity.

That support is a feature—and a risk. It can act as a backstop that purely private competitors don’t have. But it also creates political exposure, and it has limits. The failed DSME mega-merger is the cleanest reminder: domestic industrial logic can be overruled by foreign regulators when global competition is at stake.

Cyclicality and the Selective Order Strategy

Shipbuilding punishes anyone who forgets it’s cyclical. The lesson of 2014–2017 wasn’t just “don’t chase offshore plants at the wrong time.” It was the deeper truth that in shipbuilding, a bad contract can be worse than no contract.

That’s why Korean yards have increasingly talked about “selective order-taking”: leaning into higher-value ships where Korea still has a technical edge, and avoiding pure volume battles in commoditized segments. Under KSOE, HD Hyundai has been pushing further into greener designs, efficiency improvements, and automation—while continuing to load the backlog with premium categories like LNG carriers. The group has also been positioning to translate the U.S. Navy repair qualification into real bids, a different kind of demand signal than commercial shipping cycles.

Competitive Analysis: Porter's Five Forces Perspective

Threat of New Entrants: Extremely low. Shipbuilding takes enormous capital, deep engineering talent, and decades of accumulated process know-how. The 2016 downturn also showed how brutal the industry can be even with state support—many yards simply couldn’t survive the cycle.

Buyer Power: Moderate to high. Shipowners and energy majors are sophisticated, price-aware buyers. But in specialized categories—especially large LNG carriers—the field narrows, and proven quality and delivery credibility matter more.

Supplier Power: Moderate. HD Hyundai’s vertical integration—particularly in engines and key components—reduces dependence on outside suppliers and helps it control quality and economics.

Threat of Substitutes: Low in the near term. Ocean shipping remains the only practical way to move bulk commodities and energy at global scale. Over time, shifts in energy systems and trade patterns can change what ships the world needs, but not the core fact that the world still moves by sea.

Industry Rivalry: Intense, and getting tougher. China’s growth keeps pressure on pricing across many segments, and the collapse of the HHI-DSME merger left Korean yards still competing with each other at home.

Hamilton Helmer's 7 Powers Framework

Scale Economies: Large yards matter in shipbuilding. Scale helps in procurement, overhead absorption, and throughput. The HHI–Mipo merger strengthens this advantage by consolidating capacity and capabilities.

Network Effects: Limited in the classic sense, but long relationships with major shipowners can create preference and information advantages—especially when repeat orders depend on trust.

Counter-Positioning: Korea’s counter-move to China has been to climb the complexity ladder: focus on technologically demanding, high-value vessels where experience and track record are hard to fake.

Switching Costs: Moderate. A shipowner can switch yards, but confidence in execution, quality, and delivery reliability creates friction—particularly for safety-critical ship types like LNG carriers.

Branding: HD Hyundai has strong brand equity in “can you actually deliver this safely and on time?” In LNG carriers, that reputation is part of the product.

Cornered Resource: Decades of accumulated expertise in complex vessel construction and large-scale production is a resource competitors can’t replicate quickly, even with capital.

Process Power: Shipbuilding is a process business. HD Hyundai’s advantage compounds through production discipline, learning curves, and execution systems refined over fifty-plus years.

Key Performance Indicators to Monitor

For investors, the story shows up in a few metrics that matter more than most headlines:

-

Order Backlog Value and Composition: Backlog signals future revenue, but composition signals future margin. A backlog heavy in LNG and other high-spec ships usually means better economics than one filled with commoditized tonnage. In Q1 2025, HD Korea Shipbuilding & Offshore Engineering reported an order backlog of $74.228 billion.

-

Operating Margin Progression: Because revenue lags orders by years, margins often reflect decisions made long ago. Watching margins improve as higher-priced contracts flow through is a key reality check. HD Korea Shipbuilding & Offshore Engineering reported a 12.7% operating profit margin in Q1 2025—well above what shipbuilding has often achieved in weaker cycles.

-

Defense Revenue as a Percentage of Total: Defense is the diversification bet. The merged entity has stated a goal of reaching 10 trillion won of defense-sector revenue by 2035. Whether that line starts to meaningfully show up in results will be one of the clearest indicators that the strategy is working.

Bull Case Summary

The optimistic view is that HD Hyundai is positioned where profits are likely to live: high-value LNG carriers and other complex, lower-carbon ships, plus a real opening into U.S.-linked defense work as MASGA-style cooperation evolves. Combine that with improving profitability as better-priced orders roll through the backlog, and add the operational leverage and coordination benefits of the HHI–Mipo merger, and you get a company that can plausibly grow into a larger, more diversified industrial champion.

Management has said it expects the merger to help lift sales from 19 trillion won in 2024 to 37 trillion won by 2035.

Bear Case Summary

The pessimistic view is that shipbuilding never stops being shipbuilding. Cycles return, often violently. China keeps moving upmarket into categories Korea once treated as defensible. Defense diversification may prove slower, more political, and harder to monetize than hoped. And U.S.–Korea cooperation could shift with alliances, budgets, and domestic shipbuilding pressures, limiting how much opportunity actually becomes profitable work.

Regulatory and Accounting Considerations

There’s also a practical investor caution embedded in the industry’s mechanics: shipbuilding uses percentage-of-completion accounting. That means reported revenue and profit depend on management estimates about progress, cost, and risk—exactly the kind of assumptions that can unravel on large, complex projects. The offshore plant losses from 2015–2016 were a brutal demonstration of how quickly a contract can flip from “profitable backlog” to “massive write-down.”

Currency matters too. Many contracts are denominated in U.S. dollars, while a large share of costs are in won. That mismatch can help or hurt depending on FX moves, and it can meaningfully change reported profitability even when execution stays constant.

Conclusion

HD Hyundai Heavy Industries has lived multiple lives: the empty-beach miracle, the rise to global dominance, the near-death experience in 2016, the merger that made perfect sense until Europe said no, and now a reinvention built around high-value ships and defense-linked partnerships.

The December 2025 merger with HD Hyundai Mipo created a consolidated platform that management believes can compete across a wider range of vessel types while building serious naval shipbuilding capacity. Whether this becomes the next great chapter—or the next difficult bet—will hinge on execution: converting defense ambition into repeatable revenue, riding the LNG and eco-ship upcycle without overreaching, and staying ahead of increasingly capable Chinese competitors.

For long-term investors, HD Hyundai is exposure to critical global infrastructure: the ships that move the world’s energy and trade. The company’s history shows the upside is real—and so is the volatility. The same audacity that built the shipyard on an empty beach still defines the strategy. The open question is whether it can carry HD Hyundai through the next era of change as successfully as it carried it through the last.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music