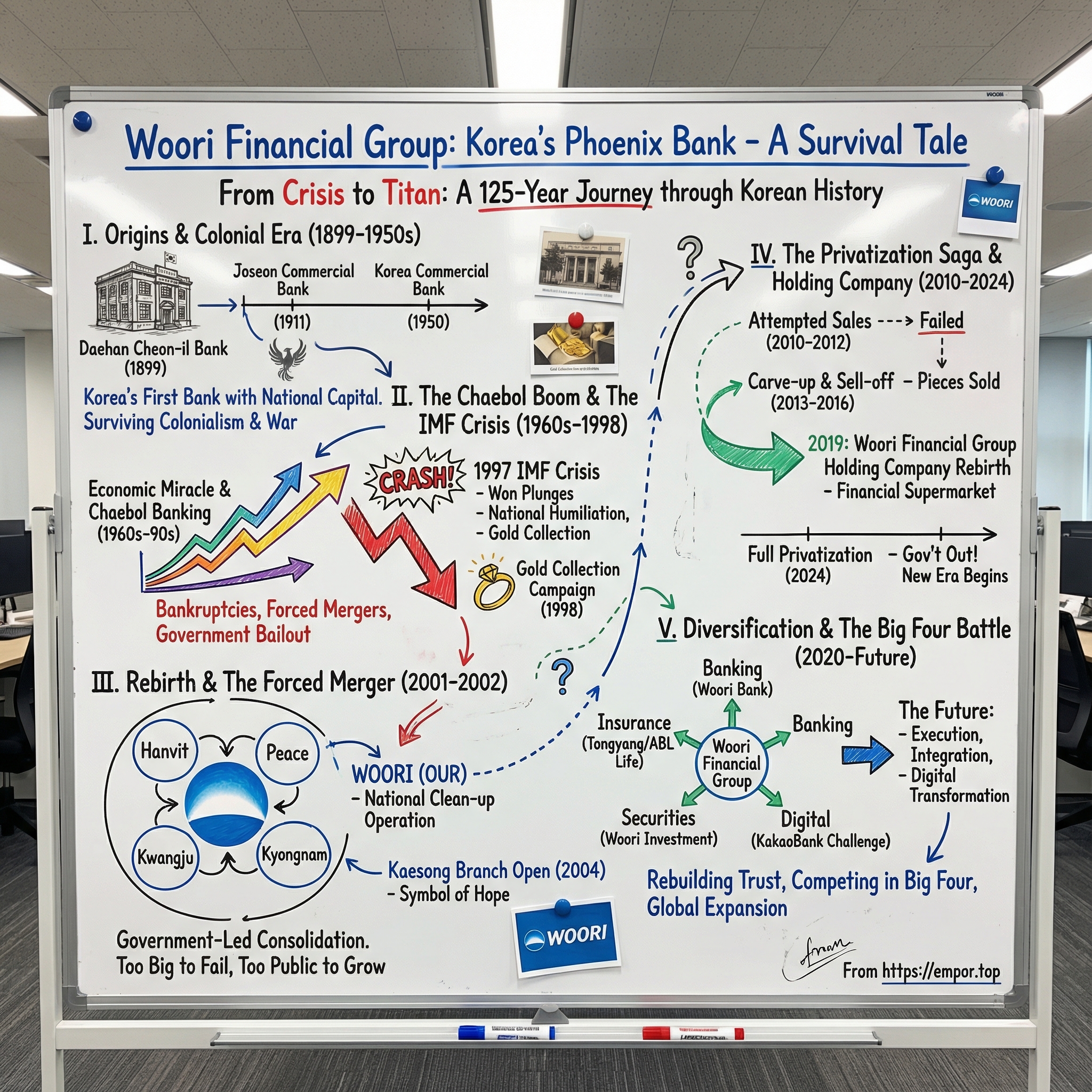

Woori Financial Group: Korea's Phoenix Bank

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

Picture Seoul in January 1998. The won has plunged—from roughly 800 to nearly 2,000 per dollar. Across the country, lines curl around gold-collection sites as ordinary Koreans—schoolteachers, factory workers, retired grandmothers—hand over wedding bands, medals, and family heirlooms to help pay down the nation’s emergency debt to the International Monetary Fund. This is the moment people still refer to as simply “the IMF Crisis,” a two-word shorthand for national humiliation and collective trauma.

Today, Woori Financial Group is a Seoul-based banking and financial services holding company, home to one of South Korea’s largest banks. But the reason Woori is so compelling is the contradiction at its center: it wasn’t built in a boom. It was assembled in failure.

In 2001, the Korean government forced together four battered commercial banks—Hanvit, Peace, Kwangju, and Kyongnam—plus Hanaro Investment Banking and their subsidiaries. These institutions had been taken over and recapitalized after falling below the Basel I minimum capital adequacy requirement of eight percent. Woori began life not as a challenger with a clever product, but as a national clean-up operation.

So here’s the question driving this story: how did a bank born out of catastrophe—cobbled together from broken balance sheets during one of the worst financial crises in modern history—turn into a roughly $355 billion financial giant?

Part of the answer starts with the rescue. In 1998, when the aftershocks of the 1997 Asian financial crisis were still ripping through the economy, a 12.7 trillion won (about $10.6 billion) government bailout kept Woori’s predecessor, Hanvit Bank, from going under. And for more than two decades after, the institution didn’t just survive—it remained a core pillar of Korean finance, even as it carried the baggage of how it had been saved.

But Woori’s story doesn’t begin in 1997 or 1998. It begins in 1899, with Daehan Cheon-il Bank—an early attempt to build modern Korean finance with national capital. From there came name changes, restructurings, and reinventions, until the group adopted the Woori name in 2002. In other words: this isn’t just a bank story. It’s 125 years of Korean economic history—colonialism, war, the Miracle on the Han River, collapse, and reinvention—told through one institution that somehow kept finding a way to continue.

Along the way, we’ll hit the big turning points: the IMF crisis that shattered the old system, the forced merger that created Woori, the privatization saga that dragged on for years, and the 2019 rebirth as a modern holding company.

And then there’s the name. “Woori” means “Our” or “We” in Korean. It’s not subtle. It was a deliberate signal: this was meant to be the nation’s bank—built from the wreckage of a national crisis and rebuilt in a country where sacrifice had become a civic duty. Follow that thread from 1899 to today, and you get a rare case study in state capitalism, crisis management, and what happens when an institution becomes too economically important—and too culturally loaded—to simply be allowed to fail.

II. Origins: Korea's First Bank & The Colonial Era (1899–1950s)

On January 30, 1899, in the waning years of the Korean Empire, a group of merchants gathered in Hanseong—today’s Seoul—to do something Korea had never done before: build a modern bank funded by Koreans.

That institution was Daehan Cheon-il Bank. It was created by merchants with ostensible backing from the Joseon government, which had proclaimed the Korean Empire just two years earlier. Only Korean nationals could hold shares, and the government itself became the single largest investor. In a region crowded with imperial ambitions, that structure mattered. This wasn’t just a new company—it was a statement about sovereignty.

At the turn of the century, Korea was caught between China, Russia, and an increasingly aggressive Japan. Daehan Cheon-il Bank became the first viable domestic joint-stock bank in the country, and in its early years it was one of only two Korean-owned, Western-style banks, alongside Hanseong Bank. In other words, Korea’s experiment with modern finance was still small enough to count on one hand.

The bank’s founding is often tied to Emperor Gojong and the imperial family’s funds—an urgent attempt to modernize national financial infrastructure before outside powers made that kind of self-determination impossible. But it wasn’t a broad-based institution. Ownership stayed concentrated: the shareholder count reached just 24 in 1901 and 38 by the end of 1902. Its first president was senior official Min Byeong-seok, succeeded in 1902 by Prince Imperial Yeong.

Then geopolitics arrived at the front door. The bank became associated with Russian interests, and when Russia lost the Russo-Japanese War, Daehan Cheon-il Bank took the hit too. In August 1905, it had to suspend payments. Even in near-collapse, the symbolism was hard to miss: from the beginning, the bank’s fate was entangled with forces far beyond Korea’s control.

Still, it operated—lending not only to Korean merchants but also to Chinese and Japanese merchants, while taking deposits. Much of the bank’s colonial-era paper trail has vanished with time, but a few remnants survive. An old account book, for example, is preserved today in Woori Bank’s private museum in the basement of its headquarters in central Seoul.

The colonial period forced adaptation, and it also left its mark in names. Woori traces its lineage from Daehan Cheon-il Bank (1899) to Joseon Commercial Bank (1911) and then Korea Commercial Bank (1950). Those name changes aren’t trivia. They capture a shift from “Daehan,” a declaration of Great Korea, to “Joseon,” the term imposed under Japanese rule—language tracking power.

After World War II and liberation, the institution turned outward. It dispatched employees to financial institutions in the United States, Europe, and Japan to study modern banking systems. In the 1950s, it pushed automation, installing electronic bookkeeping and cash dispensers, while the country struggled through reconstruction after the 1950–53 Korean War and the division of the peninsula.

During the war years, the bank continued operating and providing basic financial services amid national chaos, supporting broader efforts to stabilize and rebuild the economy. That continuity—simply staying open and functioning—helped cement its reputation as a durable institution in a society that had very few stable pillars.

Today, the bank’s origin story is treated less like corporate heritage and more like national history. Its founding documents—“Establishment & Accounting for Daehan Cheon Il Bank”—are designated as Seoul Tangible Cultural Property. Few companies can credibly say their paperwork is literally protected as cultural heritage, but that’s what happens when your origin predates occupation and becomes a symbol of what the country once tried to build for itself.

And there’s a physical relic, too. Woori Bank’s Jongno branch sits inside the Gwangtonggwan building, considered the oldest continuously operating bank building in Korea. Walk through those doors and you’re stepping into a place that has watched an empire fall, a colony rise, a war tear the peninsula in two, and a nation rebuild itself—again and again. The building is still there, still doing its job, which is about as clean a metaphor as you can get for the institution that would eventually be called Woori.

III. The Korean Economic Miracle & Chaebol Banking (1960s–1990s)

From the early 1960s through the mid-1990s, South Korea pulled off one of the fastest economic transformations in modern history. What Western textbooks label the “Korean Economic Miracle” was, in practice, a state-directed industrialization drive—and banks were the engine. The government pushed savings and deposits at home, then used the banking system to funnel capital into the industries it wanted to win.

This is where Woori’s predecessor institutions became central characters. In 1965, the bank hit a milestone no Korean bank had reached before: total deposits topping 10 billion won. It kept innovating on savings products, because in this model, deposits weren’t just a funding source—they were national fuel.

And as Korean companies started selling to the world, the bank followed. It launched a currency exchange business in 1967, the first among local lenders, and then did something even more symbolic: it opened a foreign branch in Tokyo in 1968. Korea wasn’t just rebuilding anymore. It was stepping onto the global stage, and its banks needed to be there to settle trade, move money, and support Korean firms abroad.

The basic playbook was straightforward. The government identified strategic sectors, and banks extended credit—often on preferential terms—to the chaebols, the family-controlled conglomerates like Samsung, Hyundai, and LG. Lending decisions weren’t purely about credit risk. They were also about national strategy.

It worked—until it didn’t. The same system that accelerated growth also encouraged extreme leverage. In the 1970s and 1980s, chaebols had unusually easy access to credit, and tax rules made debt even more attractive by allowing deductions for debt-related expenses. By 1997, the average debt-to-equity ratio in manufacturing was nearly 400%, about double the OECD average. Among the top 30 chaebols, it was over 500%.

The takeaway wasn’t the exact ratios. It was what they signaled: Korean industry was built on borrowed money, and a lot of it.

Underneath that was an even more corrosive dynamic—moral hazard. The expectation, reinforced over decades, was that major chaebols would not be allowed to fail. If you were a bank, that belief dulled the urgency to price risk properly. If you were a chaebol, it made leverage feel less like danger and more like a growth strategy with a government safety net.

During these decades, Woori’s predecessors expanded alongside the economy, building domestic scale and moving overseas to serve Korean exporters and expatriates. Branches and offices appeared in global financial centers—places like New York and London—because Korean business had become global business, and Korean banks needed to clear payments, provide trade finance, and look credible in international markets.

Two institutions mattered most to Woori’s later formation: Korea Commercial Bank and Hanil Bank. They thrived in the high-growth era and were considered among the country’s major banks up until the crisis years. Like the chaebols they financed, they grew fast, expanding their balance sheets in step with the national boom.

But the boom had a hidden vulnerability. Korean banks increasingly relied on short-term borrowing from abroad—often in dollars and yen—because it was cheap and plentiful. They then lent that money domestically in won, and often for longer periods. That created a dangerous double exposure: a currency mismatch (borrowing in foreign currency, lending in won) and a maturity mismatch (borrowing short-term, lending long-term). As long as global capital kept flowing in, the system looked stable. If it ever reversed, the whole structure would wobble at once.

That reversal came in 1997. After years of strong performance, structural weaknesses in Korea’s corporate and financial sectors collided with a sudden shift in global sentiment. As foreign investors took losses elsewhere in Asia and started pulling back, the capital inflows that had quietly financed Korea’s model began to run in reverse.

The boom years didn’t just set the stage for the crisis. They wrote its script. The real question wasn’t whether the system would crack—it was how quickly confidence would vanish, and how much of the banking sector would be left standing when it did.

IV. The 1997 Crisis: National Humiliation & Banking Collapse

In January 1997, South Korea still looked like the success story of the decade. Twelve months later, it was on an IMF lifeline.

The first domino fell on January 23, 1997, when Hanbo Steel declared bankruptcy. That alone was shocking: chaebols weren’t supposed to fail. But Hanbo wasn’t the last. Over the months that followed, household-name groups like Sammi, Jinro, Hanshin—and then Kia in July—hit the wall too. The old assumption that the state would quietly catch everyone started to crumble in public.

Hanbo’s collapse wasn’t a mystery of bad luck. The company had started as a modest steelmaker, then bet big on a massive new plant beginning in 1992, financing it with expensive loans. Then the global steel market turned. By mid-1996, Hanbo was already in deep trouble. Creditors tried to keep it alive with emergency lending, but it still defaulted. It entered receivership days after its bankruptcy announcement.

What made Hanbo different wasn’t just the failure. It was what the failure revealed. In June 1997, a court found that Hanbo had received illegal preferential treatment—loans pushed through under political pressure after bribery involving high-ranking politicians and bankers. Losses were estimated around $6 billion. Hanbo didn’t just break. It exposed the wiring.

International lenders had been heavily financing Korean firms for years, and they weren’t naïve about leverage. What rattled them was something else: the government let Hanbo go down. For decades, foreign banks had lent with an implicit guarantee in the background—Korea would stand behind its champions. Hanbo’s bankruptcy punched a hole in that belief.

That was the real inflection point: a psychological regime change. If Hanbo could fail, then maybe any Korean borrower could fail. And once that question enters the market, it spreads fast.

At first, many expected Korea to absorb the shock. Hanbo wasn’t huge, and the broader economy still looked strong. But optimism drained away as more corporate failures piled up. Then Kia collapsed in July—an automaker with global recognition, one of the country’s biggest conglomerates. By that point, the crisis wasn’t theoretical. If Kia could go under, nobody seemed untouchable.

And then the regional storm hit. The Thai baht’s collapse in July 1997 kicked off the Asian financial crisis, and confidence across the region began to crack. The Hong Kong market turmoil in late October sent another wave through global capital markets. Ratings agencies joined in: Standard and Poor’s downgraded Korea’s sovereign status, and Moody’s cut South Korea from A1 to A3 on November 28, 1997, then down again to B2 on December 11.

With confidence sliding, lenders did what lenders always do in a panic: they stopped rolling over short-term loans. American and Japanese banks, in particular, began refusing to renew funding to Korean financial institutions. Korea’s banks had borrowed short-term abroad and lent longer-term at home. That mismatch was manageable in good times. In a funding freeze, it becomes existential.

The Korean government tried to bridge the gap with its foreign currency reserves, helping banks meet near-term obligations. But reserves aren’t infinite, and the more it spent, the more investors worried there wasn’t enough left. A substantial portion of the nation’s reserves was even advanced to overseas branches of Korean banks, underscoring how acute the dollar shortage had become.

On November 21, 1997, the government formally asked the IMF for standby loans—an admission that Korea couldn’t meet its external debt payments on its own.

The rescue package was massive: $21 billion from the IMF, $14 billion from the World Bank and the Asian Development Bank, and $20 billion from individual governments including the U.S., Japan, Germany, and Canada. It was, at the time, the largest IMF bailout ever, and it came with stringent conditions: austerity, sweeping financial reforms, and corporate restructuring.

The won collapsed to levels nobody thought they’d see, plunging to an all-time low around 1,995 per U.S. dollar, effectively breaching the 2,000-per-dollar mark.

And then the crisis hit the real economy. Businesses failed in waves. In 1998, output fell sharply—an economic drop equal to roughly a third of the prior year’s GDP by one measure cited at the time—and millions of people were pushed toward poverty in 1997–1998.

The human toll was brutal and visible. By May 1998, about 80% of households had suffered income declines. Unemployment more than tripled from about 2% in 1997 to nearly 7% in 1999.

Then came the moment that still defines the era in the public imagination: the gold collecting campaign. Ordinary people brought wedding bands, jewelry, medals—anything with gold—to collection sites, hoping to help pay down the nation’s IMF-era debt. Roughly a quarter of the population participated. The campaign raised about $2.2 billion.

That’s why the phrase “the IMF Crisis” still lands like a punch in Korea. It isn’t just an economic label. It’s shorthand for humiliation, for lost sovereignty, for the feeling that the country had to melt down its own symbols of family and pride to survive.

And it was in that crucible—out of bank failures, forced mergers, and an urgent national effort to stabilize the system—that Woori’s modern story begins. Under the IMF program, hundreds of insolvent financial institutions were closed or merged by June 2003. Among those consolidations was the merger that would eventually become Woori.

V. The Forced Merger: Birth of Woori (2001–2002)

In the aftermath of the crisis, the Korean government faced an impossible choice: let the banking system collapse, or nationalize the wreckage and rebuild it into something stable. They chose nationalization.

One of the most consequential rescues centered on Korea Commercial Bank and Hanil Bank—two major institutions that had ridden the boom years and then slammed into the wall. Korea Commercial Bank was rescued by the Korea Deposit Insurance Corporation and merged with the similarly troubled Hanil Bank. The merged, recapitalized entity—now effectively controlled by the state, which held about a 95% equity stake—was named Hanvit Bank. It then acquired the distressed Peace Bank in 2001, and in 2002 it took on the name it still carries: Woori Bank.

This wasn’t a gentle courtship between equals. It was a post-crisis stitch-up. A bank that had been considered part of Korea’s top tier before the crisis was now being fused, on government terms, with another major lender simply to keep the system standing. By April 30, 2002, the rebranding to Woori Bank made the merger official in the public imagination—one institution, one name, one attempt at a clean slate.

To manage this new creature, Korea leaned on a structure designed for exactly this kind of moment: the financial holding company. In April 2001, the government created Woori Finance Holdings as a state-majority holding company, a vehicle to consolidate Hanvit Bank, Peace Bank, and the regional Kwangju and Kyongnam Banks. Those regional banks had been placed into receivership in 1999 and 2000 after insolvency tied to local economic downturns. Under ongoing IMF-era monitoring, the mandate was blunt: forced synergies, cost-cutting, and a faster cleanup of bad loans.

In December 2001, Hanvit absorbed Peace Bank, creating a combined institution with roughly 85 trillion won in assets. Then came the name change to Woori.

That name wasn’t cosmetic. “Woori” means “Our” or “We” in Korean, and it carried a message the government needed the public to accept: taxpayers had socialized the losses to keep the financial system alive, so this rebuilt bank would be framed as belonging to everyone. The rebrand helped sell an uncomfortable reality—that the state was now the dominant shareholder in a bank born from bailout money.

The government’s decision to “invest” taxpayers’ money in 1998 raised concerns at the time, but the bailout went ahead, with funds funneled into the group in stages until 2006. And that state presence didn’t just shape the bank’s origin story; it shaped its operating life. Even as Woori stabilized, incomplete privatization and public ownership dynamics weighed on its ability to expand freely, and on how the market perceived it.

Structurally, the new Woori was built to be big. At the time, it was enormous—South Korea’s second-largest bank, behind Kookmin Bank. But scale didn’t mean smooth sailing. Woori had been cobbled together from institutions with different cultures, incompatible technology systems, and overlapping branch networks. Integration wasn’t a quarter-long project. It took years.

And the human side was even harder. Woori became known for an internal divide that lingered after the merger between Korea Commercial Bank and Hanil Bank. The merger was crucial in creating the country’s fourth-largest lender, but it also left behind factions and identity issues inside the organization. More than two decades later, those cultural fault lines have been persistent enough that the bank even held team-building gatherings for employees who entered after the merger to strengthen solidarity. Forced mergers can create institutions. They don’t automatically create a unified culture.

Still, in the early 2000s, culture wasn’t the main metric. Survival was. The government injected capital, worked through non-performing loans, and imposed new governance structures. Slowly, the group stabilized—and that turnaround set up the next, longer chapter of the story: how to get the government out.

Because once Woori’s business normalized, the logic of state ownership flipped. The government wanted to recoup its investment and redirect public funds elsewhere. Woori, meanwhile, had an appetite to compete and grow—but faced restrictions that came with being treated as a state-run institution. The institution had been rebuilt. Its identity crisis hadn’t been resolved.

Even so, Woori began moving outward again. Early international expansion included the opening of a Moscow representative office in June 2003, and the acquisition of U.S.-based Panasia Bank in August 2003 after receiving Federal Reserve Board approval. Domestically, it opened the Bank History Museum in July 2004, billed as Korea’s first dedicated banking history exhibit—an institution trying to anchor its legitimacy in a lineage far older than the crisis that created modern Woori.

And then came one of the most symbolically loaded moves a Korean bank has ever made. In December 2004, Woori opened a branch inside the Kaesong Industrial Complex in Gaeseong, North Korea—an inter-Korean economic zone and a rare experiment in cooperation. It was the first financial institution branch in that joint zone, and it meant Woori was, quite literally, operating across the most tense border in modern geopolitics: two countries still technically at war.

Economically, the Kaesong presence was modest. Symbolically, it was enormous. It fit the “nation’s bank” identity perfectly—finance as infrastructure for a political hope.

That hope didn’t last. The Kaesong industrial park was shut down in 2016, when the South closed the complex in retaliation for nuclear provocations by the North. The branch had to close with it, though a temporary office later opened at Woori headquarters and remains in operation.

The North Korea connection underscored the paradox at the heart of Woori. Its government ties enabled projects of national symbolism. But those same ties constrained Woori’s commercial flexibility and kept it in a kind of limbo—too public to act fully like a private competitor, too important to be treated like an ordinary bank. Escaping the government’s embrace would prove far more difficult than anyone expected.

VI. The Privatization Saga: Twenty Years in Limbo (2010–2024)

For more than two decades, Woori lived in a strange middle state—listed and operating like a normal financial group, but still tethered to the government through the Korea Deposit Insurance Corporation. Everyone agreed on the end goal. Almost nobody could agree on how to get there.

From 2010 to 2012, the government tried three times to sell its stake in one clean transaction. Each time, it ran into the same wall: Woori was simply too much bank. No single buyer—or even a consortium—wanted to take the whole thing, with all the political scrutiny and balance-sheet baggage that came with it. The next few years turned into a stop-and-start roller coaster: rivals like NongHyup Financial Group and JB Financial Group picked up certain units, and on another attempt a major bidder, Kyobo Life Insurance, walked away.

The underlying problem was brutally simple. Woori was too big to sell in one piece, too politically sensitive to break up neatly, and too economically important to leave in government hands indefinitely. Every attempt to move it into the private sector triggered the same questions: Who should be allowed to own a national champion bank? How do you protect taxpayers who funded the rescue? And what price is “fair” when the seller is the state?

In June 2013, the government—through the Public Funds Oversight Committee under the Financial Services Commission—reset the plan. Instead of one blockbuster sale, it would segregate Woori Finance Holdings and its former subsidiaries into three groups, then sell the government’s interests through a series of transactions.

That’s when privatization started to look less like a single event and more like a dismantling.

In 2014, pieces of the Woori empire were sold off. Woori Financial, Woori Asset Management, and Woori F&I went to KB Financial Group, Kiwoom Securities, and Daishin Securities. Woori Investment & Securities, Woori Aviva Life Insurance, and Woori FG Savings Bank went to NongHyup Financial Group. Later that year, KDIC’s stakes in Kwangju Bank and Kyongnam Bank were acquired by JB Financial Group and BS Financial Group.

The irony was hard to miss: to privatize Woori, the government had to carve it up, selling assets to the very rivals Woori was supposed to compete against. KB, NongHyup, and JB strengthened their own portfolios with pieces of the government’s post-crisis creation—while the core of Woori Bank remained under state influence.

The first real breakthrough came on November 13, 2016. On its fifth attempt since 2010, the Financial Services Commission selected seven winning bidders—including Tong Yang Life Insurance, which was Chinese-owned—to buy a combined 29.7% stake for about 2.4 trillion won. That sale cut KDIC’s ownership from 51.1% down to 21.4%, and it was framed as the completion of the “first stage” of Woori’s privatization.

After that, the state’s grip loosened in visible increments. The government reduced its stake again in November 2021, selling another 9.3%. Five buyers were selected for that block: Eugene Private Equity, KTB Asset Management, an Align Partners-led consortium, Dunamu, and Woori’s employee share ownership association. The Financial Services Commission described it as the system finally turning a page: more room for shareholder-oriented management, less shadow of public ownership.

But Woori still wasn’t fully out. Not yet.

That final step arrived in March 2024. Woori disclosed it would acquire all remaining shares held by KDIC and cancel them—9,357,960 shares, equal to 1.24% of total shares—immediately turning the last government stake into treasury stock and retiring it. The group described the move as the end of a repayment process that had stretched 26 years from the 1998 public funds injection to full privatization.

With the government finally gone from the cap table, Woori moved quickly to behave like a fully private institution. In 2024, it repurchased and canceled KDIC’s remaining shares for about 136.6 billion won. It initiated quarterly dividends beginning in the first quarter—180 won per share for each of the first three quarters—then declared a year-end dividend of 660 won per share. The company reported a total shareholder return of roughly 33.3%.

So why did it take so long? Korean banking is never just banking. State ownership gave the government influence over lending—power that becomes especially tempting during downturns. KDIC also had a mandate to maximize recovery for taxpayers, which meant waiting for better prices rather than forcing a rushed sale. And for any would-be buyer, especially a foreign one, a controlling stake in a major Korean bank came with intense political scrutiny.

The result was a generation-long pause: Woori spent years operating with one foot in the private market and one foot in the public sector. And in that time, its rivals built out diversified profit engines—insurance, securities, asset management—while Woori stayed heavily concentrated in traditional banking.

Full privatization in 2024 didn’t just close a chapter. It finally let Woori write new ones—on its own terms.

VII. The 2019 Rebirth: Holding Company Transformation

Woori didn’t wait for full privatization to start acting like it wanted to compete. In January 2019, it made one of the biggest structural moves in Korean finance: it reconstituted itself as a holding company.

Formally, Woori Financial Group was established in January 2019 through a comprehensive stock transfer under Korean law. Once that transaction closed, Woori Bank sat underneath a new parent alongside a set of wholly owned operating companies: Woori FIS Co., Ltd., Woori Finance Research Institute Co., Ltd., Woori Credit Information Co., Ltd., Woori Fund Services Co., Ltd., and Woori Private Equity Asset Management Co., Ltd.

That sounds like corporate plumbing, but the intent was strategic and very human: turn a bank into a financial “department store.” The holding company structure is built for exactly that—developing and cross-selling a wider menu of products to the same base of retail and corporate customers, and doing it across banking, cards, capital, asset management, and investment businesses. It also makes M&A easier, because the parent can buy, fund, and reorganize subsidiaries in a way a standalone bank can’t.

Woori used the holding company shift to broaden its portfolio—into asset management, real estate trusts, capital, and savings—while operating at scale through a domestic network of 920 branches across 14 subsidiaries, plus 480 global networks across 24 countries.

There was also an element of playing catch-up. By the end of 2008, the other major Korean banking groups—KB Kookmin, Shinhan, and Hana—were already operating under holding companies. Woori was the last one to make the transition, about a decade behind its closest peers.

The reason this structure matters comes down to how Korean financial regulation draws boxes. A holding company can own stakes across banks, securities firms, insurance companies, and other financial entities, which creates both commercial leverage (cross-selling and internal referrals) and regulatory flexibility. Capital can be raised at the parent level and deployed where it’s needed most, instead of being trapped inside a single banking balance sheet.

Once the new parent was in place, Woori began methodically pulling more businesses under the umbrella via stock-based integrations. It issued 680,164,306 common shares at the holding company’s establishment in January 2019, then issued an additional 42,103,377 shares in September 2019 through a comprehensive stock exchange with Woori Card. It issued another 5,792,866 shares on August 10, 2021 to integrate Woori Financial Capital as a wholly owned subsidiary. In August 2023, it issued 32,474,711 more shares through stock exchanges to bring in Woori Investment Bank Co., Ltd.

The build-out continued beyond the big integrations. Woori Financial F&I was established in January 2022. Woori Venture Partners was acquired in March 2023. As of December 31, 2024, Woori Venture Partners had $0.2 billion in total assets, operating revenue of $42.1 million, and $24.9 million in net income.

Underneath the parent, the core bank remained the anchor. As of December 31, 2024, Woori Bank operated 684 branches and offices in Korea, plus 16 overseas branches, 8 overseas branch offices, and 4 overseas offices. At that same date, it had $328.7 billion in total assets and $2.1 billion in net income.

Around it sat the rest of the modern Woori stack: credit cards, capital and leasing, investment banking, asset management, private equity, and the service companies that quietly keep a large financial group running. Woori Card Co., Ltd. reported $11.2 billion in assets, $1.6 billion in operating revenue, and $0.1 billion in net income as of December 31, 2024. Woori Financial Capital Co., Ltd. reported $8.7 billion in total assets, $1.2 billion in operating revenue, and $0.1 billion in net income.

And in 2024, Woori took another step toward rounding out the platform: Woori Investment Securities Co., Ltd. was formed by the merger of Korean Foss Securities Co., Ltd. and Woori Investment Bank Co., Ltd. for the year ended December 31, 2024.

The holding company rebirth was Woori’s way of admitting a hard truth: traditional banking alone wasn’t enough anymore. The structure gave it the chassis for a broader financial group. But turning that chassis into a true competitor—less dependent on bank earnings—would require bigger moves. And those moves were far easier to make once full privatization finally removed the last government constraints.

VIII. The Diversification Push: Building a Financial Supermarket (2020–2025)

For years, Woori had a structural problem hiding in plain sight: almost all of its profits still came from the bank. Roughly 90% of earnings were tied to traditional lending and deposit-taking—exactly the part of finance most exposed to rate cycles, regulation, and fierce competition. Meanwhile, peers like KB had spent years building real profit engines in insurance, securities, and asset management. Woori, by comparison, looked lopsided.

That’s why the diversification push in 2024 and 2025 wasn’t incremental. It was a land grab.

The headline move was insurance. Woori agreed to buy a 75.34% stake in Tongyang Life for 1.28 trillion won and 100% of ABL Life for 265.4 billion won—both from China’s Dajia Insurance Group. Tongyang Life was the sixth-largest of Korea’s domestic life insurers by insurance premiums, sitting behind the household names: Samsung Life, Kyobo, Hanwha Life, Shinhan Life, and NH NongHyup Life.

The regulator sign-off mattered here. Woori Financial Group, the country’s fourth-largest financial services provider, received conditional approval from the Financial Services Commission after an eight-month review. The transaction followed a share purchase agreement signed the previous August as part of a 1.55 trillion won deal with Dajia. The strategic point was simple: add a major insurance pillar to an organization that had been overwhelmingly a bank.

And the backstory is almost as interesting as the deal itself. Tongyang Life and ABL Life weren’t just “assets for sale.” They were caught up in the unraveling of Anbang Insurance—once a high-profile Chinese insurer that entered Korea by acquiring Tongyang Life in June 2015 and ABL Life in December 2015. After Anbang fell into a severe management crisis, Chinese authorities set up Dajia Insurance to take control of, manage, and restructure Anbang’s assets. Multiple privatization attempts from 2020 onward failed, and the process ultimately ended with the decision to declare bankruptcy—creating the opening for Woori to buy two sizable Korean insurers from a Chinese-run wind-down vehicle.

Woori completed the acquisition on July 2, about ten months after signing. Afterward, it appointed industry veterans Kwak Hee-pil and Sung Dae-kyu as CEOs of ABL and Tongyang, respectively.

Put it together, and you can see the shape of the new Woori taking form. The group had established a securities affiliate the year prior, and now it had added insurance. Tongyang and ABL brought a combined $40 billion in assets—enough to put them among the top five life insurers in Korea by that measure. They were also expected to lift Woori’s overall profitability. ABL earned $77 million in profit in 2024, up 14.9% from 2023, while Tongyang’s net income reached $228 million, up 17.1%. Combined, the two insurers accounted for 13.1% of Woori Financial’s overall profit.

As Leaders Index CEO Park Ju-gun put it: “Woori has a set of tasks to rise to the top of Korea's financial powerhouse league and one of them was to complete its business portfolio. The group finished the job this time, and that means something.”

The securities leg was moving in parallel. Woori’s brokerage business launched after merging Korea Foss Securities—an online fund sales platform Woori acquired in May—with Woori Investment Bank, the country’s last merchant bank known for commercial loans and real estate project financing. On Aug. 1, Woori formally launched the combined brokerage arm, Woori Investment & Securities.

Chairman and CEO Yim Jong-yong framed the intent clearly: these acquisitions were designed to “enhance the group's portfolio, which has been predominantly focused on banking.” That’s also why the insurance move carried extra symbolism. After selling Aviva Life Insurance to DGB Financial Group in 2013, Woori had become the only one of the nation’s five major banking groups without an insurance arm. This deal ended that anomaly.

Diversification wasn’t only domestic, either. Overseas growth was the second engine running at the same time. “Woori Bank's global division reported a net profit of $340 million last year, and it has achieved an average annual asset growth of 9 percent during the last three years,” said Yun Seog-mo, head of Woori Bank’s global business division. Overseas net profit made up 15.4% of total net profit, and Woori put special emphasis on Southeast Asia—Indonesia, Vietnam, and Cambodia—which together generated 43% of overseas net profit. As of the end of September, Woori Bank operated 466 branches in 24 countries.

To press that advantage, Woori planned in the first half of 2024 to inject $500 million into those Southeast Asian units—$200 million each into Indonesia and Vietnam, and $100 million into Cambodia.

Woori’s internal target, set in 2023, was to lift the share of global revenue to 25% by 2030. But the results have been uneven. Net profits from 11 overseas branches fell 21% in 2023 and declined another 7.9% year-on-year in 2024. Still, Woori kept prioritizing Indonesia, Vietnam, and Cambodia, with Bank Woori Saudara in Indonesia positioned as a centerpiece. Woori invested $192 million in the Indonesian lender in 2024, raising its stake from 84.2% to 90.7%.

Vietnam showed what the upside could look like when the model works. Woori Bank Vietnam reported its best performance since launching in 2017, posting operating profit of $103 million and net profit of $50 million in 2024. The bank credited the surge to its digital strategy and retail customer growth, with operating profit up 50% and net profit more than doubling from the prior year.

Still, none of this happened without friction. Woori’s insurance acquisitions hit a regulatory snag when the Financial Supervisory Service downgraded the group’s management assessment rating from Level 2 to Level 3—an issue because a financial holding company must maintain at least Level 2 to incorporate new subsidiaries.

The scrutiny intensified after an illegal loan scandal involving relatives of former Woori Financial Chairman Sohn Tae-seung. In August 2024, the FSS found Woori affiliates had improperly lent 35 billion won to those relatives.

Even with the hurdles, the deals ultimately closed. With Woori Financial’s assets at 525 trillion won at the end of the prior year, plus about 52 trillion won in assets coming from Tongyang and ABL, the acquisition pushed Woori further into the top tier of Korean financial groups by asset size. And strategically, it did what Woori needed most: it finally gave the group a full three-legged platform—banking, securities, and insurance—with the promise of cross-selling and a less fragile earnings mix.

In other words, Woori has now built the portfolio its competitors assembled years ago. The question shifts from architecture to execution: can management integrate these businesses, deliver real synergies, and narrow the profitability gap with rivals who have had a long head start in insurance and securities?

IX. The Competitive Landscape: Korea's Big Four Banking Battle

Zoom out from Woori’s internal rebuild and you run straight into the reality of Korean banking: it’s a crowded field on paper, and a concentrated one in practice.

Formally, South Korea’s banking sector includes national banks, regional lenders, three digital banks, government-affiliated specialized banks, and dozens of foreign bank branches. But when people talk about the center of gravity, they mean the Big Four: KB Kookmin, Shinhan, Hana, and Woori—each massive, each systemically important, and each fighting for share in a market that rarely reshuffles the leaderboard.

The numbers tell you how tight the grip is. The five major commercial banks collectively control roughly three-quarters of deposits and well over half of loans. That kind of concentration tends to limit brutal price wars. The battle is real, but it’s often fought in distribution, product breadth, and brand—while the industry structure keeps profitability unusually resilient.

You can see it in earnings. In the first half of 2025, the four largest financial groups—KB, Shinhan, Hana, and Woori—posted a combined net profit of 10.33 trillion won, a record. And 2024 was also a banner year: the Big Four’s combined profits reached about 16.80 trillion won on a preliminary basis, beating the prior high set in 2022.

What makes this even more controversial is how the profit showed up. South Korea’s major banks have been criticized for widening the gap between what they charge borrowers and what they pay depositors. The average spread between lending and deposit rates, around 0.5 percentage points in 2023, jumped to over 1.3 points in the first five months of 2025—an unusually sharp move that reflects muted competition and a regulatory environment that, at least in practice, hasn’t forced the spread back down quickly.

But that profitability has started to cast a shadow. Through the first three quarters of 2025, the four largest groups collectively cleared 15 trillion won in cumulative profits, even as credit stress built in the background. By the end of the third quarter, “precautionary loans”—delinquencies in the one-to-three month range—rose to 18.35 trillion won, the highest since early 2019. At the same time, the average non-performing loan coverage ratio across the four groups fell to 123.1%, the lowest level on record. In other words: the engine is still running hot, but the road is getting rougher.

Inside that oligopoly, Woori’s position is both clear and slightly awkward. It’s typically fourth by most measures, behind KB, Shinhan, and Hana. The ranking rarely changes, and all four are extremely profitable—so “winning” is often less about beating the others this quarter, and more about building a mix of businesses that holds up over the next cycle.

That’s where diversification becomes the defining contest. KB has been the benchmark: its non-bank subsidiaries contribute roughly 40% of earnings. Woori, historically, has been the opposite—more than 90% of profit tied to traditional banking. The Tongyang Life and ABL Life acquisitions are meant to narrow that gap, potentially bringing Woori’s banking dependence down toward 80% and giving it a more balanced, KB-like earnings profile.

Woori’s recent financial trajectory shows why management is pushing so hard. In 2024, Woori Financial Group reported revenue of 11.47 trillion won, up from 9.50 trillion the year before, and earnings of 2.93 trillion won, also up strongly year-on-year. In the quarter ending September 30, 2025, Woori Bank recorded revenue of 2.47 trillion won, essentially flat versus the prior period, with last-twelve-month revenue reaching 11.31 trillion won, up meaningfully year-over-year.

The twist is that the next competitive threat isn’t necessarily another megabank. It’s your phone.

South Korea’s mobile banking adoption has surged, and digital challengers—backed by some of the country’s most powerful tech platforms—have forced the incumbents to compete on speed, user experience, and cost. Kakao Bank is the emblem of that shift. Launched as a mobile-only bank in July 2017, it attracted over 300,000 subscribers in its first 24 hours and crossed two million customers within two weeks, while rapidly pulling in deposits and making loans. Its growth didn’t really slow down—it scaled into the mainstream.

By the end of 2024, KakaoBank had reached 24.88 million customers and 18.9 million monthly active users, with penetration across demographics that traditional banks can’t ignore. It competes directly with other internet-only banks like K Bank and Toss Bank, and indirectly with every incumbent that has had to rebuild its digital offering just to defend its existing base.

Now KakaoBank is approaching a new problem: saturation. With 25.8 million users—close to half of Korea’s adult population—domestic growth is getting harder, especially as digital competition intensifies. That raises the stakes for new digital services and for expansion beyond Korea.

For the incumbents, the response has been visible and physical: fewer branches. Shinhan has planned a reduction that would leave it with 665 outlets at end-March; Woori planned to shut down 52 offline branches over the same period to operate 659. NH NongHyup and KB Kookmin have also planned cutbacks. The direction is unmistakable: branches are being rationalized as digital becomes the default, even if banks still keep physical presence for complex products and customers who prefer face-to-face service.

And yet, this is where Woori’s legacy advantage still matters. Woori Bank’s corporate client list includes many of South Korea’s most powerful and prestigious institutions—Samsung Electronics, CJ Group, Hanwha, KAIST, POSTECH, Yonsei University, and the Korean University of Foreign Studies among them. Those relationships are sticky. They generate fee income, recurring loan demand, and a kind of institutional trust that’s hard for a digital-first newcomer to replicate overnight.

This is the competitive landscape Woori is rebuilding for: a highly profitable Big Four that rarely changes order, an oligopoly under political scrutiny, and a digital wave that forces every incumbent to modernize while defending the corporate relationships that made them powerful in the first place.

X. Porter's Five Forces & Hamilton's 7 Powers Analysis

Threat of New Entrants: MODERATE-LOW

On paper, Korean banking is one of the hardest markets to break into. A full banking license demands real capital, heavy regulatory scrutiny, and proof you can run a complex, risk-managed operation. Incumbents also sit on decades of customer relationships and nationwide distribution—advantages that take years to build the slow way.

Digital banks don’t get a free pass. In South Korea, they largely operate under the same regulatory framework as traditional banks, with two limited breaks: a temporary waiver from applying Basel III rules until two years after launch, and a smoother path to credit card license approval. As one observer put it, the “favor” is modest.

But modest regulatory differences don’t mean modest competitive impact. The real threat is distribution. KakaoBank’s 2017 launch—built on top of KakaoTalk, the country’s dominant messaging platform—was a genuine wake-up call for incumbents. It opened as mobile-only in July 2017 and drew about 300,000 accounts in its first 24 hours, then reached two million customers within two weeks. At that point, traditional banks couldn’t dismiss digital banking as a niche experiment. A new entrant had shown it could scale faster than branches ever could.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers: LOW

For banks, funding is the raw material—and it’s largely interchangeable. Deposits, interbank borrowing, and capital markets are competitive and liquid. No single funding source has durable leverage over a major bank.

Labor is also relatively standardized. Korea produces a steady pipeline of finance talent, and pay practices across major banks are similar enough that people move around—but not in a way that creates a structural edge for any one player.

Bargaining Power of Buyers: LOW-MODERATE

Retail customers should be easy to win and lose. Opening an account can take minutes, especially now. In practice, though, customers are sticky. Salary deposits, mortgages, credit cards, and automatic bill payments create friction that makes switching feel annoying even when it’s technically simple.

Big corporate clients have more negotiating power, especially the largest conglomerates. But Korean corporate banking is still relationship-heavy. Companies place real value on banks that understand their business, can move fast in a crisis, and have supported them through cycles.

Threat of Substitutes: GROWING

Substitutes are no longer theoretical. Fintech platforms, digital payments, and peer-to-peer lending keep expanding into what used to be “bank-only” territory. When financial services are embedded inside the places people already spend time—e-commerce platforms like Naver and Coupang, or messaging apps like KakaoTalk—basic transactions can drift away from the bank as the primary interface.

Cross-border payments are another pressure point. Stablecoins and fintech remittance providers could chip away at international transfers, a business banks have traditionally treated as dependable and profitable.

The incumbents aren’t standing still. As branch networks shrink, traditional banks have poured effort into online and mobile banking, rebuilding apps and digital onboarding to match shifting customer expectations. The open question is where the equilibrium lands: how far digital banks can replace traditional banks, and how effectively the incumbents can defend their core relationships as the front door to banking moves onto the phone.

Industry Rivalry: HIGH but COORDINATED

Competition among the Big Four is intense—but rarely suicidal. The market’s oligopolistic structure discourages destructive price wars. Instead, banks fight on service quality, digital experiences, product breadth, and relationship management.

Policy has also shaped the competitive dynamics. Efforts to curb household debt and cool housing markets have given banks both political cover and regulatory justification to keep lending disciplined. At the same time, state-backed mortgage products—guaranteeing up to 90% of principal—have reduced default risk on new housing loans, supporting a stable, lower-volatility lending model. The combined effect is a system where rivalry is real, but profitability remains protected in ways that aren’t common in more fragmented markets.

Hamilton's 7 Powers Analysis:

Scale Economies: MODERATE

Branch networks and IT platforms create operating leverage: once the infrastructure exists, serving one more customer is cheap. Scale also helps with regulatory capital efficiency. The twist is that digital banks have proven you can achieve meaningful scale faster—and with less physical infrastructure—than the old model assumed.

Network Effects: LIMITED

There are some network effects in payments and cards: broader merchant acceptance makes a bank’s payment products more valuable. In corporate banking, relationships can expand into ecosystems where one bank serves multiple companies across a supply chain. But these effects are modest compared to software or social networks.

Counter-Positioning: NOT APPLICABLE

Woori is defending an incumbent franchise. It isn’t a challenger using a fundamentally new model that incumbents can’t adopt without cannibalizing themselves.

Switching Costs: MODERATE

Customers get locked in through payroll deposits, mortgages, and credit history. For corporates, switching is even harder: treasury operations, credit facilities, and day-to-day payments are deeply integrated, and changing banks creates real operational disruption.

Brand: MODERATE

Brand matters, but not in the way it does in consumer tech. In Korean banking, relationships and service quality typically matter more than logos. Woori’s heritage carries credibility, but it doesn’t automatically translate into pricing power or prevent customers from moving.

Cornered Resource: LIMITED

Woori doesn’t have exclusive access to scarce inputs—talent, technology, or regulatory permissions—at least not in a way peers can’t match.

Process Power: LIMITED

There’s no clear evidence here of uniquely superior operating processes that deliver a durable cost or quality advantage over other major Korean banks.

Key KPIs for Ongoing Monitoring:

If you’re tracking whether Woori’s strategy is actually working, three metrics do most of the heavy lifting:

-

Non-Banking Profit Contribution: Banking still accounts for roughly 90% of profits. The diversification push should show up as that figure falling toward about 80% or lower, signaling insurance and securities are becoming meaningful earnings pillars.

-

CET1 Ratio: Woori targets 12.5% for 2025. This capital buffer is the governor on everything—dividends, buybacks, and acquisition capacity. The story here is whether Woori can keep capital strong while still funding growth and shareholder returns.

-

Net Interest Margin (NIM): NIM remains the core earnings engine. If competition intensifies or rates shift, margin compression hits profits quickly. And because the lending-deposit spread has recently been unusually wide, any normalization would put pressure on earnings.

Conclusion: The Phoenix's Next Chapter

Woori Financial Group’s story is, in many ways, Korea’s story: a bank born in the twilight of empire, pushed through colonization and war, carried upward by the country’s compressed industrialization miracle, nearly broken by the IMF Crisis, nationalized to keep the financial system standing, and then—after more than two decades of limbo—finally returned to private ownership.

With that last chapter closed, Woori has been eager to show what a fully privatized Woori looks like. On July 25, 2024, it became the first Korean bank holding company to announce a Corporate Value Enhancement Plan. And on February 7, 2025, the board resolved to acquire and cancel additional treasury shares, with a planned acquisition amount of 150 billion won—part of a broader push to lift shareholder returns. The plan also set out a mid-to-long-term total shareholder return target of 50%, and Woori used its February 7, 2025 disclosure to publish a look back at 2024 and lay out priorities for 2025.

Step back, and the investment case is easy to understand. Woori is an entrenched player inside a profitable, concentrated banking market. It is no longer tethered to government ownership. And it has spent the last few years building the portfolio its peers assembled long ago—using the holding company structure to add new pillars and create room for further M&A. The insurance deals, in particular, plug the most obvious hole in the product lineup.

The list of risks is just as legible. Integration is never just operations and org charts—Woori’s own history is proof that mergers can leave cultural scars that take years to fade. Digital competitors keep grinding away at retail banking. Rising delinquencies are a reminder that credit cycles always turn eventually. And the group has faced sharper regulatory scrutiny after the inappropriate loan scandal involving relatives of its former chairman.

Woori Financial Chairman Yim Jong-yong put the moment bluntly when he announced the group would operate under an emergency management system throughout 2025 after the incidents of the prior year, including the inappropriate loans. “Rebuilding Woori Financial on a stronger foundation of trust is the task we must undertake now.”

That’s the heart of the next chapter. Woori is trying to execute from behind. KB, Shinhan, and Hana have spent years learning how to run diversified financial conglomerates. Woori is newer to that game. On paper, the platform is now complete—banking, securities, insurance. In reality, the hard part starts after the deals close: making the pieces work together, and doing it fast enough to narrow the gap.

For long-term investors, Woori is ultimately a bet on execution. The assets are real: a 125-year franchise, 684 domestic branches, deep relationships with Korea’s largest institutions, a growing Southeast Asian footprint, and newly acquired insurance platforms with meaningful scale. The market, meanwhile, has often valued Woori at a persistent discount to peers. The question is whether management can earn its way out of that penalty.

If Woori pulls it off, the phoenix rises again—this time not just to survive, but to compete at the top of Korean finance. If it doesn’t, Woori stays what it has been for much of the post-crisis era: a profitable institution that never quite escapes fourth place in a race where the leaders are separated by inches—and stay that way, year after year.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music