MatsukiyoCocokara & Co.: The Drugstore That Became Japan's Beauty Empire

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

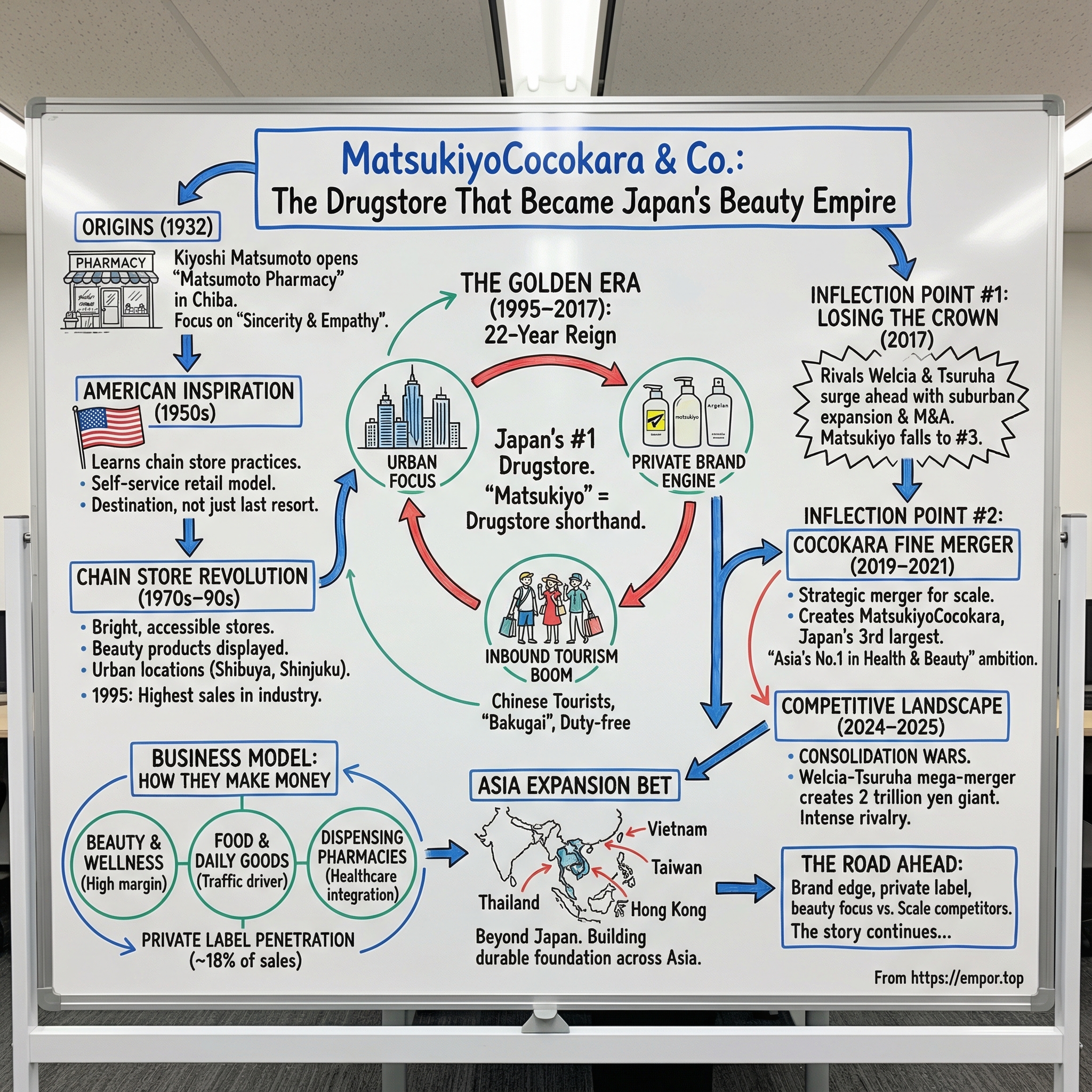

Picture this: a corner drugstore in the Tokyo suburbs. Not quiet. Not clinical. Instead, it’s buzzing—packed with Chinese tourists snapping photos in front of immaculate walls of sheet masks and serums. Shopping baskets are piled high with collagen drinks, eyedrops, and sunscreen. Staff in crisp uniforms switch seamlessly into Mandarin. Digital screens blink through tax-free shopping instructions.

This is Matsumotokiyoshi—“Matsukiyo” to pretty much everyone in Japan—and it’s not just a pharmacy chain. It’s a cultural landmark that somehow grew from a single shop opened in 1932 by a 23-year-old entrepreneur into one of the most recognizable retail brands in the country.

Today, MatsukiyoCocokara & Co. sits at roughly a $7.68 billion market cap, with trailing twelve-month revenue around $7.27 billion. It runs retail drugstores and insurance dispensing pharmacies across Japan through three main segments: the Matsumotokiyoshi Group Business, the Cocokara Fine Group Business, and the Management Support Business.

But the numbers are just the scoreboard. The real story is what the brand meant. For decades, Matsukiyo didn’t just participate in Japan’s drugstore industry—it defined it. From 1995 onward, it led the country in sales for 22 straight years, to the point where “Matsukiyo” became almost shorthand for “drugstore,” the way “CVS” is used in the U.S.—but with more brand heat, more beauty focus, and a growing pull for international shoppers.

And then the ground shifted. In 2017, the reign ended. Rivals with a different playbook—suburban expansion, relentless store openings, and aggressive M&A—surged past. Matsukiyo’s premium, urban-heavy footprint, once a strength, started to look like a constraint in a market that was rapidly consolidating around scale.

What came next was reinvention under pressure: a high-stakes merger courtship, a transformative combination with Cocokara Fine, and a new ambition—to become “Asia’s No.1 in Health & Beauty.” But the consolidation wave didn’t stop there. By late 2025, the landscape is tilting again: Tsuruha, based in Sapporo, announced it will integrate its operations with Welcia—currently the biggest force in Japanese pharmacy retail—in December 2025. If completed, it creates a giant with sales over 2 trillion yen, more than double MatsukiyoCocokara’s revenue.

This is a story about consolidation as survival, private brands as a profit engine, inbound tourism as rocket fuel, and the strategic chess match playing out inside Japan’s drugstore wars. Let’s dive in.

II. Origins: The Founder & His American Inspiration (1932–1960s)

On December 26, 1932—93 years ago today—a 23-year-old pharmacist named Kiyoshi Matsumoto opened a small shop in the Kogane district of Matsudo, Chiba Prefecture, not far from Tokyo. He called it Matsumoto Pharmacy. It was a modest start. But it contained the blueprint for what Japan would eventually come to call “Matsukiyo.”

Even the choice of location was a strategy. He set up along the Joban railway line, in a town that didn’t yet have a pharmacy. And from day one, he ran the business with an almost stubborn devotion to customer service. He displayed empty boxes simply to signal how wide the product selection could be. If a customer asked for something he didn’t have, he would go buy it from another store and deliver it anyway. Not because it was efficient—because it was the point.

That wasn’t just hustle. It was philosophy. Kiyoshi’s ideals didn’t match the standard business thinking of the time. He built the store around sincerity and empathy, distilled into two simple slogans: Consideration for Customers, and Good Products at Better Prices.

To understand how unusual that was, you have to picture Japan in the early 1930s. The country was still feeling the effects of the global depression. Modern consumer culture hadn’t really arrived. And pharmacies weren’t places you browsed—they were places you went when you were sick, often dim and clinical, more intimidating than inviting.

Kiyoshi Matsumoto saw a different future. Customer satisfaction became the foundation, and then came the catalyst: a trip to the United States, where he learned chain store practices. He saw what self-service retail could do—not just sell medicine, but create a store people actually wanted to enter. The lesson was simple and radical: make the pharmacy a destination, not a last resort.

In 1954, the business was renamed Matsumoto Kiyoshi after its founder, and it began expanding while steadily widening its assortment. Postwar Japan was about to absorb a wave of American-style consumerism—and Matsumoto Kiyoshi was positioned to translate that energy into a distinctly Japanese retail experience.

What’s striking is how long the founding mindset endured. Chairman Namio Matsumoto later became the founding chairman of the Japan Association of Chain Drugstores, recognized for promoting the role of drugstores in society and advancing the idea of self-medication—encouraging people to take a more active role in protecting their own health.

In other words, the Matsumoto family didn’t just build a chain. They helped legitimize the category. And that early DNA—customer obsession, accessibility, and service rooted in sincerity—didn’t fade as the company grew. It became the through-line that carried Matsukiyo from a single shop in Chiba into a national institution.

III. The Chain Store Revolution: Remaking the Japanese Pharmacy (1970s–1990s)

One store opening in Ueno’s Ameyoko market captured the shift Matsumotokiyoshi was betting the company on. This wasn’t the old-style Japanese pharmacy—quiet, dim, and slightly intimidating. It was designed to feel friendly and accessible, a place where you could ask questions, get guidance, and walk out not just healthier, but happier. The stated goal was simple: make customers cheerful and bring them greater health and beauty.

The playbook came from American drugstores, but the execution was distinctly Matsukiyo. Brighter interiors. Inviting storefronts. A broader mix of products. Cosmetics out where you could actually see them—and try them—rather than hidden behind a counter. The pharmacy stopped being a place you visited only when something was wrong, and started becoming somewhere you could browse.

That was the real insight: healthcare retail could be aspirational. Matsumotokiyoshi helped turn the Japanese drugstore into a lifestyle destination—where beauty, wellness, and everyday convenience all lived under the same roof.

Making that shift meant rebuilding the entire experience. Layouts opened up. Sampling became normal. Staff training emphasized approachability, not just clinical authority. The job wasn’t merely to dispense medicine. It was to welcome people in, and keep them coming back.

And it worked. From its start as a privately owned “Matsumoto Pharmacy” in Kogane, Matsudo City in Chiba Prefecture in 1932, the company grew into a dominant player across the Kanto, Tokai, and Kansai regions—then hit a major milestone: in 1995, it reached the highest sales in the industry.

The timing mattered. Japan’s bubble had burst, but daily-life spending didn’t disappear—it got more value-conscious. Matsumotokiyoshi positioned itself right in that gap: not luxury retail, but accessible aspiration. Premium enough to feel like an upgrade, affordable enough to become a habit.

The broader category was expanding fast too. According to the Japan Association of Chain Drug Stores, the Japanese drugstore market was about 6.5 trillion yen, and it had been growing quickly year after year, fueled by low prices and longer operating hours. Drugstores weren’t just competing with other pharmacies anymore. In the 1990s, they started driving growth by selling toiletries and food—products that used to belong to supermarkets and convenience stores. That shift didn’t just add revenue; it pulled drugstores into the center of everyday shopping.

Chairman Namio Matsumoto’s push for “self-medication,” through his role at the Japan Association of Chain Drugstores, reinforced the trend. As over-the-counter products became more accepted and accessible, the addressable market for chains kept widening—helped along by a government that had its own incentive to encourage consumers to manage more health needs outside the doctor’s office.

By the early 2000s, Matsumotokiyoshi had real scale. It kept opening stores, but it also expanded through business partnerships, capital alliances with regional players, and franchise agreements. By the fiscal year ended March 2001, the store count had reached 500.

This is where the growth model becomes important. Franchises and regional alliances let Matsumotokiyoshi extend its footprint without paying for every new store itself. It was a smart way to spread the brand quickly—one that built national presence while keeping expansion relatively capital-light. Later, though, as rivals leaned harder into full acquisitions and consolidation, that same approach would start to show its limits.

IV. The Golden Era: 22-Year Reign as Japan's #1 Drugstore (1995–2017)

For more than two decades, Matsumotokiyoshi wasn’t just the biggest drugstore chain in Japan—it was the category’s north star. The yellow-and-blue storefront wasn’t merely recognizable; it became visual shorthand for “drugstore.”

The company had been building toward that moment since 1932, but by the early 2000s, the scale was unmistakable. Matsumotokiyoshi was already operating more than 1,000 stores, and its mix was dialed in: health essentials, beauty, daily goods—whatever customers needed, all in one stop. It was mass retail, but with a point of view.

And the brand power was real, not just retail muscle. In 2018, Interbrand Japan ranked Matsumotokiyoshi No. 34 on Japan’s Best Domestic Brands—making it the only drugstore to appear on the list. It also ranked 4th in year-over-year brand value growth. In a space known for price tags and point cards, Matsumotokiyoshi had achieved something rarer: it had become a brand people actually felt something about.

A lot of that came down to a strategic choice that looked obvious in hindsight, but risky at the time: Matsumotokiyoshi leaned urban. While rivals like Welcia and Tsuruha built suburban empires—big boxes, big parking lots, big weekly baskets—Matsumotokiyoshi bet on density and foot traffic. It planted flags in places like Shibuya, Shinjuku, Ginza, and Harajuku.

That choice shaped everything. Urban stores generated strong sales in compact footprints, pulled in younger and more trend-aware customers, and kept Matsumotokiyoshi plugged into Japan’s fashion-and-beauty bloodstream. These weren’t just convenient pharmacies; they became destinations. Tourists didn’t merely stumble into Matsumotokiyoshi—they put it on the itinerary.

Then came the margin engine: private brand. Instead of treating store-brand products as the bargain bin, Matsumotokiyoshi built them as a premium pillar of the business. The “matsukiyo” private brand wasn’t positioned as “good enough.” It aimed to be desirable—products that promised real skincare benefits while also feeling emotionally uplifting, with formulations and packaging that could stand next to national brands without flinching.

Lines like Argelan organic skincare and The Retinotime anti-aging range didn’t win by copying incumbents—they competed on quality. And because private label changes the economics of retail, it wasn’t just a branding play. It let Matsumotokiyoshi capture more of the value chain and reinvest the gains into sharper pricing, better merchandising, and more product development. Over time, private label became a meaningful portion of the business; by FY 2023, it accounted for about 18% of total sales, up from around 15% the year before.

The company also pushed into digital, investing in e-commerce and customer engagement tools as consumer behavior diversified. E-commerce sales grew 25% year-over-year. Point programs, app promotions, and data-driven marketing didn’t just move product—they built habits, strengthened retention, and gave the company a clearer read on what customers actually wanted.

But even at the peak, the pressure was building underneath the floorboards. The same urban focus that made Matsumotokiyoshi special also capped how far it could spread. The company did move to diversify formats—operating large drugstores with parking lots along suburban thoroughfares—but that meant fighting on terrain where competitors already had years of reps, and where scale and logistics mattered as much as brand heat.

In other words: Matsumotokiyoshi had spent two decades perfecting one kind of dominance. The market was about to reward a different one.

V. The Inbound Tourism Boom: When Chinese Tourists Discovered "Matsukiyo"

The 2010s delivered a growth engine nobody in Japan’s drugstore business could ignore: inbound tourism. Millions of visitors—especially from China—didn’t just shop in Japan. They came with shopping lists.

In 2015, Japan even gave the phenomenon a name. “Bakugai,” meaning “explosive buying,” won the Japan Times’ grand prize for the year’s most memorable buzzword. The image was vivid: tour buses rolling into major shopping districts, groups fanning out with purpose, and drugstores turning into high-speed depots for cartons of skincare, OTC medicine, and health products—piled into baskets and wheeled straight to the register.

The spend was staggering. In 2015, Chinese travelers accounted for roughly $12.2 billion of tourism consumption in Japan—about 41% of the total. And what did they want? Exactly what drugstores were built to sell: cosmetics and perfume (purchased by 63% of visitors), food, spirits, and cigarettes (55%), and over-the-counter medicines and toiletries (52%). The shopping lists leaned heavily toward cosmetics and health products like baby formula and skin-whitening items, with electronics and high-end luxury brands also in the mix.

Matsumotokiyoshi was perfectly positioned for this moment, almost by accident. Remember that urban footprint—Shibuya, Shinjuku, Ginza—the thing that limited suburban scale? Those were the same neighborhoods where tourist foot traffic concentrated. And the brand equity Matsukiyo had built domestically translated surprisingly well overseas. On Chinese social media, “Matsukiyo” started to function like a stamp of authenticity: a place to buy real Japanese beauty products, not questionable knockoffs.

Japanese retailers across Tokyo, Osaka, and Fukuoka raced to roll out the red carpet—tax rebates, multilingual staff, signage that made the process frictionless. Matsumotokiyoshi leaned in hard. The chain became widely known as a go-to stop for foreign travelers, converting 380 stores into duty-free shops. That meant real investment: tax-free infrastructure, multilingual store materials, and Mandarin-speaking staff. During peak inbound years, it paid off.

And then—like a switch flipped—COVID-19 arrived.

The pandemic didn’t merely slow tourism. It effectively erased it. International arrivals to Japan fell to near zero from 2020 through 2022, and urban drugstores lost what had become a structurally meaningful source of sales.

But when Japan reopened, the rebound was just as dramatic. In 2024, the country welcomed a record 36.87 million visitors who spent JPY 8.14 trillion, lifting sales across major urban corridors. Inbound tourist spending of roughly JPY 8.1 trillion became Japan’s second-largest “export” sector, behind automobiles—a striking reminder that tourism wasn’t a side story anymore. It was macro.

MatsukiyoCocokara felt that recovery in real time. In Q1 2025, the company posted a 5.3% year-over-year revenue increase to JPY 273.6 billion, supported by the return of urban foot traffic and growing inbound demand. The Cosmetics and Food segment grew by 8.7% and 8.6%, respectively, helped along by tourist purchasing and app-based promotions that nudged shoppers toward repeat visits and bigger baskets.

For investors—and for the company’s own strategy—this is the tradeoff. Inbound tourism is rocket fuel when it’s on. But it’s also inherently fragile. Geopolitics, currency swings, public health shocks—any of them can hit spending overnight. And because MatsukiyoCocokara is so concentrated in the very cities tourists flock to, it gets the upside and the downside in higher doses than most of its rivals.

VI. INFLECTION POINT #1: Losing the Crown & The Wake-Up Call (2017)

The fiscal 2017 results delivered a message Matsumotokiyoshi couldn’t brush off. After 22 straight years on top, the company had been passed.

Welcia surged ahead, and Tsuruha did too. Matsumotokiyoshi—long the default “No.1” in the public imagination—fell to third.

So what changed? Not the basic demand. Japan still bought plenty of everyday health and beauty. What changed was the playbook for winning.

Matsumotokiyoshi had spent years perfecting an urban, brand-forward model: dense neighborhoods, high foot traffic, and stores that felt closer to beauty retail than old-school pharmacies. Meanwhile, rivals like Welcia and Tsuruha played a different game: expand relentlessly, then get even bigger through acquisition. In Japan’s drugstore market, two things were happening at once—companies opened more stores, but the number of independent operators shrank as the biggest chains bought the rest.

That consolidation dynamic mattered. Scale in drugstores isn’t a vanity metric; it shows up in purchasing power, distribution efficiency, and the ability to spread advertising, loyalty programs, and back-office costs across thousands of locations. Matsumotokiyoshi’s mix of franchises and alliances helped it grow, but it didn’t create the same unified, fully integrated machine that M&A could.

Welcia is the cleanest contrast. It built a huge footprint—around 1,500 stores—mostly suburban. And that “boring” suburban strategy turned out to be structurally advantaged: cheaper real estate, bigger floor space, parking, and a customer base aligned with where Japan’s demographics were heading. Families stocking up. Older shoppers with recurring needs. Bigger baskets, more routine trips.

All of a sudden, Matsumotokiyoshi’s greatest strength started to look like a ceiling. It had optimized for younger, urban, trend-aware shoppers—an important segment, but not the one expanding fastest as the standard drugstore format shifted toward large-floor suburban stores.

That’s what made 2017 such a jolt. The question wasn’t simply “How do we catch Welcia?” It was more existential: do you abandon what makes you special to fight on suburban turf? Do you double down on being premium and accept that the market crown is gone? Or do you find a third path—one that gives you scale without losing your identity?

Matsumotokiyoshi’s leadership landed on a hard conclusion: in an industry now defined by consolidation, organic growth wasn’t going to be enough. If the market was going to reward scale economies in purchasing, distribution, and marketing, then Matsumotokiyoshi would need a move big enough to change its trajectory.

And that set the stage for what came next.

VII. INFLECTION POINT #2: The Cocokara Fine Merger Drama (2019–2021)

What Matsumotokiyoshi did next wasn’t a slow, incremental “let’s open a few more stores” plan. It was corporate maneuvering that reads like a business school case on competitive M&A.

Cocokara Fine suddenly became the prize. As The Japan News put it at the time, if Cocokara Fine merged with either Sugi Holdings or Matsumoto Kiyoshi, the combined company would leapfrog Welcia and become Japan’s largest drugstore chain.

And Cocokara Fine had a very specific kind of value. It wasn’t an old, single-brand empire like Matsumotokiyoshi. It was a roll-up—born from the merger of major chains, technically less than twenty years old, but built from businesses with long histories and deep local trust. Cocokara Fine itself framed the story around “omotenashi,” the idea that the combined know-how of its predecessor companies would be unified around customer service.

The consolidation history mattered. In April 2008, Cocokara began integrating Seijo and Segami Medics, both national-level drugstore chains. In 2010, it merged with Allied Hearts Holdings, which included Zip Drug and Lifort—strong brands in Kansai and Tokai. Piece by piece, Cocokara Fine had assembled a footprint with real weight.

Now drop that into the competitive map. The three players formed a clean puzzle: Cocokara Fine had breadth across Kanto and Kansai, Matsumotokiyoshi was powerful in the Tokyo metropolitan core, and Sugi Holdings had built a network aimed at suburbia. Put any two together and you didn’t just get bigger—you got more complete.

That’s what set off the drama. Sugi Holdings announced it was in talks with Cocokara Fine and said it had made a formal proposal the prior April, aiming for a basic agreement by July 31. Almost simultaneously, Cocokara Fine announced it was also in discussions with Matsumotokiyoshi to form a capital and business alliance.

For a stretch, it looked like a classic two-suitor race. Cocokara Fine considered a tie-up with Sugi—but ultimately chose Matsumotokiyoshi’s offer.

From Matsumotokiyoshi’s perspective, the logic was straightforward: scale, fast, without walking away from its identity. The first step was financial. Matsumotokiyoshi Holdings announced it would take a minority stake in Cocokara Fine—20% of common stock via a third-party allotment—making Cocokara Fine an affiliate. The stated ambition was bold: domestic sales of ¥1 trillion and 3,000 stores, with the longer-term goal of becoming the number one company in Asian beauty and healthcare.

Then the structure kept evolving as the finish line approached. On February 26, 2021, the companies issued a press release announcing they had entered into a merger agreement ahead of an October 1, 2021 effective date. The original plan—creating a holding company through a joint share transfer—was revised into a share swap, with Matsumotokiyoshi becoming the full parent and Cocokara Fine the full subsidiary.

That change didn’t land quietly. Some shareholders argued Cocokara Fine was being undervalued. But the strategic rationale held: together, the companies could aim to dominate health and beauty with the scale to compete.

By October 2021, the integration created what the companies described as a “social and lifestyle infrastructure” business, with more than 3,400 domestic stores.

The synergy expectations were big too. The companies projected roughly JPY 20 billion in operating profit synergies on a consolidated basis—driven by the classic retail playbook: stronger purchasing leverage, eliminating overlapping functions, and optimizing store formats.

And those formats became a key part of the post-merger plan. Stores nationwide were organized into five types: “Standard Type,” “Suburban Daily Type,” “Urban Flagship Type,” “matsukiyoLAB Type,” and “Global Type.” It was an admission, and a strategy: different customers shop drugstores for different reasons, but a scaled operator can still standardize enough behind the scenes to run efficiently.

The result was a newly bulked-up MatsukiyoCocokara—Japan’s third-largest drugstore operator, and finally large enough to fight the consolidation war on more even footing with Welcia and Tsuruha.

But the industry wasn’t done moving. The landscape was about to shift again.

VIII. The Competitive Landscape: Understanding Japan's Drugstore Wars

Japan’s drugstore market is enormous—and still getting bigger. In 2023, it was valued at about US$103.65 billion, and projections put it at roughly US$140.82 billion by 2029, growing at a mid-single-digit pace through 2029.

What makes the market so intense isn’t just the size. It’s the structure. Japan’s drugstore industry has long been fragmented, with a huge number of operators fighting for the same customer trips. And yet, a handful of national champions—chains like Matsumoto Kiyoshi, Tsuruha Holdings, and Welcia Holdings—sit at the center of gravity, using sprawling store networks and brand recognition to pull the market toward consolidation.

The really interesting part is that the competition doesn’t stay neatly inside the “drugstore” category. These companies don’t just fight supermarkets and convenience stores—they sometimes partner with them. The first major convenience-store tie-up came in August 2009, when Matsumotokiyoshi partnered with Lawson. Then in December 2009, Cocokara Fine partnered with Circle K Sunkus. In other words: in Japan, today’s competitor can become tomorrow’s distribution channel.

That blur reflects how Japanese retail evolved. Drugstores pushed into food and household goods to drive traffic and increase basket size. Convenience stores moved the other way, adding pharmacy counters to better serve an aging population. The boundaries didn’t just soften—they became contested. “What is a drugstore?” stopped being obvious.

Meanwhile, as the sector has become increasingly dominated by major chains, the default store format has tilted suburban: larger floor plates, more parking, more categories. Add in the growing acceptance of self-medication and Japan’s aging demographics, and the product mix keeps widening—nursing care goods, health foods, functional foods, plus the daily necessities that make these stores part pharmacy and part neighborhood general store. The expectation is that larger stores, capable of carrying that entire range efficiently, will keep gaining share.

Within that environment, the big competitors have carved out distinct identities. Welcia leaned into dispensing pharmacy integration, building healthcare credibility alongside retail. Tsuruha expanded through aggressive regional acquisitions—often preserving local brands on the front door while unifying the back-end operations. Sundrug differentiated through operational efficiency and value pricing. Cosmos leaned hard into a discount format that resonates with price-sensitive shoppers.

And then there’s the healthcare layer that’s increasingly shaping the whole battlefield: Medication Therapy Management, or MTM. In plain terms, MTM is pharmacists working with patients—and coordinating with other healthcare professionals—to ensure medications are being used correctly and effectively. In a country with a large elderly population, and many seniors managing multiple chronic conditions, that kind of hands-on medication management becomes a real service, not just a nice-to-have. Drugstores are uniquely positioned for it because they’re accessible, visited frequently, and staffed by people who can build ongoing relationships with patients.

But MTM isn’t free. It requires pharmacist training, dispensing infrastructure, and systems that can connect into broader healthcare workflows. That tilts the playing field toward large incumbents, who can afford the investment and navigate the regulatory complexity—making it one more force pushing the industry toward scale.

IX. INFLECTION POINT #3: The Welcia-Tsuruha Mega-Merger (2024–2025)

Just as MatsukiyoCocokara was still absorbing the Cocokara Fine integration, the ground shifted again—only this time, the move was bigger than any single operator.

In February 2024, retailer Aeon and drugstore chains Tsuruha and Welcia said they planned to combine their businesses by 2027, creating what would become Japan’s largest pharmacy group.

The structure was straightforward and ruthless: Tsuruha Holdings and Welcia Holdings announced a business integration through a share exchange, aiming to create a drugstore giant with annual revenue exceeding 2 trillion yen and a network of more than 5,600 stores. The logic, as they framed it, was that industry consolidation was accelerating under the pressures of population decline, drug price revisions, and labor shortages.

The deal was set up with a clear near-term milestone, too. Subject to conditions being met, the share exchange would take effect on December 1, 2025.

It didn’t glide through, though. The transaction drew shareholder opposition—most notably from Orbis, which publicly criticized the proposed tripartite “Capital and Business Alliance” between Tsuruha, Aeon, and Welcia. Orbis argued the terms undervalued Tsuruha and failed to provide a sufficient control premium.

But the train kept moving. Despite the resistance, Tsuruha shareholders approved the merger plan with Welcia. On Monday, May 26, 2025, shareholders voted through all proposals presented at the general meeting.

Under the plan, Tsuruha would make Welcia a wholly owned subsidiary through an equity swap. Then Aeon—Welcia’s parent—would make Tsuruha a consolidated subsidiary through a tender offer. In effect, the industry’s biggest force was being stitched together with the backing of one of Japan’s retail titans.

The timeline was brisk and highly choreographed: the business integration and share exchange agreement was formally signed on April 11, 2025; shareholder approvals followed on May 26 and 27, 2025; Tsuruha executed a 1-to-5 stock split on September 1, 2025; Welcia was delisted on November 27, 2025; and on December 1, 2025, the share exchange became effective.

For MatsukiyoCocokara, this wasn’t just another headline—it reset the competitive math. A combined Welcia-Tsuruha, backed by Aeon, would operate more than 5,500 stores with annual sales exceeding JPY 2 trillion, forming Japan’s largest pharmacy retail group.

And the scale gap is the point. A player that large can squeeze more out of purchasing, push harder in supplier negotiations, and blanket the market with marketing and loyalty infrastructure in ways a smaller rival simply can’t match. The result is asymmetric competition: when the biggest operator gets bigger, the whole industry feels it.

But scale still isn’t everything. MatsukiyoCocokara’s differentiation—urban concentration, beauty credibility, private brand strength, and international expansion—gives it options that a pure scale machine doesn’t automatically have. The question is whether those options are enough in a Japan that’s rapidly consolidating into retail superpowers.

X. Business Model Deep Dive: How MatsukiyoCocokara Makes Money

Zoom in past the merger headlines and the store counts, and MatsukiyoCocokara is, at its core, a modern retailer: a nationwide chain of drugstores and pharmacies that sells what people need every day—and what they want when they’re trying to feel better, look better, or live a little healthier.

The shelves tell you the business model. Yes, there are medical and pharmaceutical products. But there’s also a wide mix of cosmetics, health products, general merchandise, and food. And importantly, MatsukiyoCocokara doesn’t just resell other people’s brands. It actively builds its own, selling products under names like matsukiyo, Argelan, The Retinotime, and matsukiyo LAB. It’s also experimented with higher-touch concepts like a healthcare lounge, a beautycare studio, and even a supplement bar—signals that this is as much “beauty and wellness” as it is “drugstore.”

Operationally, the company is organized into three segments. The Matsumotokiyoshi Group Business is the Matsumotokiyoshi-branded store network. The Cocokara Fine Group Business is the Cocokara Fine-branded network. And the Management Support Business sits behind both, handling procurement, groupwide operations, and indirect functions like advertising and promotion. Most of the revenue comes from the Matsumotokiyoshi Group Business segment.

If you want to understand what’s happening in Japan’s drugstores more broadly, look at the revenue mix. In 2023, food dominated the market. “Food” here doesn’t mean fresh produce—it’s the high-velocity consumables that make drugstores a weekly habit: snacks, beverages, health foods, and dietary supplements. Growth has been driven by two forces that compound each other: people want convenient grab-and-go options, and more shoppers are actively seeking products that fit a health-and-wellness mindset.

But food is largely a traffic business. The real profit story sits in beauty.

MatsukiyoCocokara’s operating profit rose 14.6% year over year, helped by operational efficiency initiatives and a richer mix of higher-margin cosmetics. Margin improved by 50 basis points to 7.2%. This is the retail playbook at its best: get the customer in the door with staples, then win the wallet with products that carry more margin and more brand pull.

Private label is the centerpiece of that margin strategy. The company’s private label products have earned strong recognition and account for 35% of total sales. In retail, private brands typically generate meaningfully higher gross margins than national brands, so when more than a third of what you sell is yours, you’re no longer just a distributor—you’re a product company with a retail channel attached.

Scale matters here too, and MatsukiyoCocokara has it. As of June 30, 2025, it operated close to 3,493 stores in Japan—1,946 in the Matsumotokiyoshi Group and 1,547 in the Cocokara Fine Group—plus 82 stores overseas (24 in Taiwan, 30 in Thailand, 14 in Vietnam, 13 in Hong Kong, and 1 in Guam).

Then there’s the healthcare wedge: dispensing pharmacies. This is one of the company’s most important long-term bets because it ties drug retail directly into Japan’s aging demographic reality. In Q1 2025, the company opened 24 new dispensing pharmacy stores—19 in the Matsumotokiyoshi Group and five in the Cocokara Fine Group. As Japan’s healthcare system faces rising demand and persistent cost pressure, retail-integrated dispensing can be a compelling combination: accessible locations, repeat visits, and a place where health products and everyday goods sit one aisle away.

Financially, the post-merger machine has been humming. Over FY21–24, MatsukiyoCocokara delivered a 13.3% revenue CAGR to JPY 1.1 trillion, driven by the post-COVID recovery in same-store sales and basket sizes, rapid network expansion, and stronger cosmetics and private brand sales. Over the same period, EBITDA grew at a 23% CAGR to JPY 105 billion, with margin expanding from 7.7% to 9.9%. Net income rose at a 16.5% CAGR to JPY 54.7 billion.

That earnings growth flowed through to cash. Free cash flow improved sharply, moving from minus JPY 6 billion to JPY 61.6 billion. Debt fell from JPY 22.9 billion to JPY 2.2 billion, and gearing improved from 4.9% in FY21 to 0.4% in FY24.

That deleveraging matters because it changes what the company can do next. A cleaner balance sheet means more flexibility—whether that’s funding future acquisitions, pushing harder overseas, or returning more capital to shareholders.

For FY25, management has guided to steady growth: revenue up 3.6% year over year to JPY 1.10 trillion, EBIT up 4.2% to JPY 85.5 billion, and net profit up 3.3% to JPY 56.5 billion. The company also expects a dividend of JPY 46.0, with the payout ratio rising 40 basis points to 33.3%.

XI. The Asia Expansion Bet: Beyond Japan

At home, MatsukiyoCocokara is playing in a market that’s big—but structurally tough. Japan is aging. The population is shrinking. And the competitive intensity keeps climbing as the biggest players consolidate. So if you’re management, and you’re looking for true upside beyond “run the stores a little better,” you eventually end up in the same place: outside Japan.

That’s the bet. Under the group philosophy of “Creating the future ‘normal’ and innovating lifestyles,” MatsukiyoCocokara has set its sights on becoming Asia’s No. 1 beauty and health company—building on its large store base in Japan while expanding across markets like Thailand, Taiwan, Vietnam, and Hong Kong.

The international story starts in Bangkok. In October 2015, Matsumoto Kiyoshi opened its first Thailand store at CentralPlaza Ladprao. From there, it kept building. Today, there are more than 30 Matsumoto Kiyoshi stores across Thailand, including mini-shops inside Tops supermarkets—an important detail, because it shows a willingness to adapt formats to local retail infrastructure rather than forcing a Japan-style standalone footprint everywhere.

Vietnam came next. In 2020, Matsumoto Kiyoshi opened its first store in Ho Chi Minh City, on the B2 floor of Vincom Center Dong Khoi—one of the city’s busiest and most popular shopping malls. That location choice tells you exactly what the company thinks it’s exporting: not “pharmacy,” but a high-traffic, modern health-and-beauty shopping experience.

Then there’s Hong Kong—where the company made its boldest statement so far. The flagship in Causeway Bay wasn’t positioned as just another store opening. It was described as Matsumotokiyoshi’s first Global Flagship Store, meant to symbolize the brand concept, showcase a cutting-edge customer experience, and accelerate overseas business development. It also marked the company’s 55th overseas store.

On the grand opening day—October 21, 2022—people lined up out front. The store leaned into an “unprecedented” customer experience, including a customized digital flow based on AI facial analysis data and personalized cosmetic recommendations. The reception was strong: more than 5,500 visitors came through in the first three days, and sales exceeded expectations.

The strategic logic behind all of this is pretty clean. Across Southeast Asia, middle classes are growing, demand for “Made in Japan” beauty remains strong, and tourism plus social media have already done a lot of the brand education. In a way, Matsukiyo’s inbound-tourism boom in Japan becomes marketing for its outbound strategy abroad—the trust built with travelers at home can travel back with them.

But none of this is automatic. Local competitors in Thailand, Vietnam, and elsewhere have home-field advantages: local sourcing relationships, established customer habits, and lower cost structures. Korean beauty brands have captured massive mindshare across the region. And Japanese retailers, historically, haven’t always found it easy to translate domestic operating excellence into consistent international execution.

Still, the company’s ambition is explicit. Alongside its domestic mission—promoting regional comprehensive care systems as part of what drugstores contribute to society—MatsukiyoCocokara wants to establish a durable business foundation across Asia, where awareness of beauty and health continues to rise, and ultimately aim for the No. 1 share in those beauty and health markets in the future.

XII. Porter's Five Forces Analysis

If you want a clean way to understand what MatsukiyoCocokara is up against, Michael Porter’s Five Forces is a good lens. Not because it’s academic—but because it explains why this industry keeps consolidating, why margins get squeezed, and why a “great brand” still isn’t enough on its own.

Threat of New Entrants: MODERATE

Starting a drugstore chain in Japan isn’t like launching a DTC skincare brand from a laptop. The barriers are real. Prime urban real estate is expensive and scarce. Pharmacy licensing creates regulatory friction. Incumbents already have supplier relationships that translate into better pricing and better access. And at scale, distribution and marketing become a flywheel that’s hard to match store by store.

But the door isn’t closed. E-commerce lowers the need for physical presence, and international beauty retailers like Sephora and Watsons have entered Japan with their own playbooks. At the same time, digital-native brands can increasingly reach consumers directly, sidestepping traditional retail shelves entirely.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers: LOW-MODERATE

In a business this large, purchasing power is a weapon. MatsukiyoCocokara’s scale gives it leverage with cosmetics and consumer packaged goods suppliers, and its private label strategy reduces dependence even further by creating credible alternatives to national brands.

At the same time, not every supplier is equally negotiable. Pharmaceuticals sit in a more regulated world, where supplier pricing power is supported by the structure of the market.

Operationally, the company is also trying to tilt the table in its favor by pushing store formats that are more specialized in health and beauty—and pairing that with digital marketing designed to match increasingly fragmented consumer behavior.

Bargaining Power of Buyers: MODERATE-HIGH

Customers have options. Switching costs are basically zero: if the store across the street has a better promotion, a better points deal, or just a shorter line, shoppers can move instantly.

Loyalty programs help, but they don’t eliminate that underlying reality. And the customer base itself splits in an important way: tourist shoppers tend to be more brand- and product-driven, while local shoppers are typically more price-sensitive and promotion-responsive.

Threat of Substitutes: HIGH

MatsukiyoCocokara isn’t only competing with other drugstores. It’s competing with convenience stores, grocery stores, and e-commerce—and sometimes even partnering with them, which says a lot about how blurry the category lines have become.

Convenience stores carry overlapping daily goods. E-commerce enables direct brand-to-consumer distribution. Department store beauty counters compete for premium spend. And new retail channels, especially online, have already changed how and where people buy.

Competitive Rivalry: VERY HIGH

This is the force that dominates the entire picture. The sector has been consolidating for years, and as major companies take a bigger share, the “default” drugstore format has shifted toward larger suburban stores that can carry a broader assortment efficiently. Self-medication becoming more accepted—and Japan’s aging population—only expands what drugstores are expected to sell, from OTC medicine to health foods to nursing care goods.

The result is a market where rivalry isn’t subtle. It’s constant. Price competition, promotions, and store openings are the daily grind—and the Welcia-Tsuruha merger raises the stakes for everyone else, because when the largest players get larger, the pressure ripples outward across the whole industry.

XIII. Hamilton's 7 Powers Analysis

Hamilton Helmer’s framework is a useful gut-check here: what, if anything, is actually durable about MatsukiyoCocokara’s advantage?

1. Scale Economies: MODERATE (and under threat)

With more than 3,400 domestic stores, MatsukiyoCocokara gets real benefits: better purchasing terms, more efficient distribution, and the ability to spread back-office costs across a huge footprint. But the Welcia-Tsuruha tie-up changes the physics of the industry. When a rival shows up with roughly twice the revenue, “big” suddenly starts to feel merely “large.” MatsukiyoCocokara still has a scale edge over smaller chains, but versus the new leader, the gap is structural.

2. Network Effects: LIMITED

This is retail, not social media. The business doesn’t naturally compound through network effects. Loyalty programs help with repeat visits, but one customer earning points doesn’t meaningfully improve the experience for another customer.

3. Counter-Positioning: MODERATE

MatsukiyoCocokara’s identity—urban locations, beauty-forward merchandising, and a more “aspirational drugstore” vibe—creates some counter-positioning against competitors that built their empires in suburban, daily-necessities-heavy formats. For those players to truly match MatsukiyoCocokara in the urban beauty lane, they’d have to reshape their own playbooks and potentially dilute what already works for them. That said, the protection is not permanent. As competitors broaden their store formats, the moat gets shallower.

4. Switching Costs: LOW

Switching is easy. If the store across the street runs a better promotion, customers can walk. Apps and point cards can nudge behavior, but they don’t lock anyone in. The best “switching cost” MatsukiyoCocokara has is its private label: if you specifically want matsukiyo products, you have to shop here. But for national brands, the shelves look similar everywhere.

5. Branding: STRONG

This is the standout. Matsumotokiyoshi is the only drugstore brand to appear in Japan’s Best Domestic Brands rankings, and that signal matters. The brand carries recognition, trust, and a kind of everyday aspiration that is difficult to manufacture quickly—especially in a category that often competes on price. It’s also what makes international expansion plausible: the company isn’t showing up in Asia as “a Japanese drugstore,” but as Matsukiyo.

6. Cornered Resource: LIMITED

MatsukiyoCocokara doesn’t appear to control a truly cornered resource like exclusive supplier access or irreplaceable real estate. Its assets—store locations, supplier relationships, customer data—are valuable, but not uniquely owned in a way competitors can’t replicate.

7. Process Power: MODERATE

Decades of iteration show up in the unglamorous places: operations, merchandising, and inventory discipline. Private label development is also a form of process power—accumulated know-how in what to make, how to price it, and how to sell it at scale. These advantages are meaningful, but over time they can be copied by competitors with enough capital and patience.

XIV. Bull Case & Bear Case

The Bull Case:

The bull case for MatsukiyoCocokara rests on three engines that reinforce each other: inbound tourism, private brand expansion, and Asia growth.

Start with tourism. Japan welcomed a record 36.87 million visitors in 2024, and the company’s store network is built to catch that demand—because it’s concentrated exactly where tourists actually go. If global travel continues to normalize and China’s outbound travel keeps recovering, MatsukiyoCocokara gets a tailwind that many of its more suburban competitors simply can’t replicate.

Then there’s private label. Matsukiyo’s in-house brands still have room to grow compared with leading international retailers, and every point of mix shift toward private brand tends to matter disproportionately for profit. More matsukiyo products on the receipt means better margins without needing heroic top-line growth. Layer in the company’s digital push—app-based loyalty, sharper targeting, and AI-driven beauty recommendations—and you get a clearer path to repeat purchases and higher-value baskets, not just one-off tourist splurges.

Finally, Asia. The overseas business is still early, but the direction is obvious: Southeast Asia’s middle class is expanding, Japanese beauty retains a premium halo, and the company’s 82 overseas stores give it a foundation to build from rather than starting from zero.

The recent results give this optimism something concrete to stand on. In 2024, MatsukiyoCocokara & Co. generated revenue of 1.06 trillion, up 3.82% year over year. Earnings were 54.68 billion, up 4.45%.

Put it together, and the financial profile supports the bullish narrative: steady growth, improving profitability, low debt, and strong free cash flow—all of which give management flexibility to invest, expand, and respond quickly as the market shifts.

The Bear Case:

The bear case is simpler, and a little more brutal: competition is getting heavier, Japan is getting older, and executing abroad is hard.

The Welcia-Tsuruha merger creates a scale competitor MatsukiyoCocokara can’t catch through organic growth alone. Over time, that kind of size advantage tends to show up everywhere—in purchasing leverage, distribution efficiency, and marketing reach. Even if MatsukiyoCocokara keeps running well, the gravity of the bigger player can still compress margins and narrow strategic options.

Then there’s Japan itself. For any retailer anchored domestically, long-term demographics are a headwind: population decline, an aging consumer base, and changing consumption patterns. MatsukiyoCocokara’s urban concentration offers some protection—cities hold up better than rural areas—but it doesn’t rewrite the macro picture.

Operational risks stack on top: intensifying price competition, swings in consumer demand, potential regulatory changes in pharmaceutical retail, and persistent labor shortages that can raise costs and constrain store operations.

International expansion is another “good story, hard execution.” Japanese retailers have often struggled to translate domestic strengths overseas, and markets like Thailand, Vietnam, and Hong Kong require real cultural and operational adaptation. And while 82 overseas stores signal proof of concept, they’re still less than 3% of the total network—far from proof that the model scales profitably outside Japan.

Finally, the same inbound tourism exposure that powers the bull case also creates cyclical risk. Geopolitics, currency moves, or another public-health shock could hit travel quickly—and because MatsukiyoCocokara is positioned to benefit disproportionately when tourists show up, it’s also positioned to feel the impact when they don’t.

XV. Key Metrics for Investors

If you’re tracking MatsukiyoCocokara as a business—rather than as a headline about mergers and store counts—there are three numbers that tell you, quarter by quarter, whether the strategy is actually working.

1. Same-Store Sales Growth (Existing Store Sales)

Same-store sales strips out the “we opened more stores” effect and asks the more revealing question: are the stores you already have getting healthier?

When same-store sales are up, it usually means some combination of more customers walking in, or each customer spending more per visit. When they’re down, it’s often a signal that traffic is slipping, competitors are taking share, or the chain is leaning too hard on promotions.

The useful nuance is that same-store sales breaks into two levers: traffic and basket size. For MatsukiyoCocokara, that split matters more than most. Tourist traffic can swing results in the urban flagship locations, while suburban and neighborhood stores live or die on local repeat customers. Watching traffic and basket size separately helps you see whether growth is coming from sustainable habits—or from a tourism surge that can fade as quickly as it appears.

2. Private Label Sales Penetration

Private label is where MatsukiyoCocokara gets to stop being “a store that sells brands” and start acting more like a product company—with retail as the distribution engine.

The reason investors care is simple: higher private label penetration typically lifts gross margin, because the company captures more of the value that would otherwise go to national brands.

Management has been pushing this hard. In FY 2023, private label sales were about 18% of total sales, up from roughly 15% the year before. The direction matters as much as the level. If that number keeps climbing over time, it’s proof the chain is strengthening its differentiation and widening its profit pool. If it stalls, it suggests either customers aren’t buying, or the assortment isn’t expanding fast enough to matter.

3. Operating Margin

Operating margin is the scoreboard that pulls everything together: product mix, private label progress, purchasing terms, labor productivity, and how intense the price war is at any given moment.

Recently, margin improved by 50 basis points to 7.2%. That’s meaningful in a category where competitors fight for share with discounts, points, and relentless store openings.

In the post Welcia-Tsuruha world, this metric becomes even more telling. If MatsukiyoCocokara can keep expanding margins despite facing a larger, more scale-advantaged rival, it’s a sign the company’s differentiation—beauty, private brand, and urban strength—is real. If margins start compressing, it’s a warning that the market is forcing everyone toward the lowest common denominator.

XVI. Myth vs. Reality: Fact-Checking Consensus Narratives

Myth 1: MatsukiyoCocokara is primarily a pharmacy company.

Reality: “Drugstore” is in the description, but the center of gravity is retail—beauty, daily goods, and the kinds of consumables that keep people coming back weekly. In 2023, food was the largest category in Japan’s drugstore market, and “food” here isn’t groceries in the supermarket sense. It’s the high-frequency stuff: snacks, drinks, health foods, and supplements. Dispensing pharmacies are important and growing, especially as Japan ages, but they’re not the main engine. Cosmetics and everyday goods are what drive most of the revenue—and most of the margin story.

Myth 2: The inbound tourism boom is a temporary phenomenon.

Reality: COVID made tourism feel fragile, but the longer arc points the other way. Japan has been deliberately building inbound tourism for decades, starting with the “Visit Japan Campaign” in 2003. Then came the policy tailwinds: looser visa rules, expanded tax-free programs, smoother immigration procedures, and more flight capacity. That push helped bring Japan to a record 31.9 million visitors in 2019. And the key signal is what happened after the shock: 2024 didn’t just “recover.” It set a new record at 36.87 million visitors—suggesting the market has expanded beyond the old ceiling.

Myth 3: The Welcia-Tsuruha merger is an existential threat.

Reality: It’s a real challenge, but not an automatic death sentence. Mega-mergers look clean on slides and messy in operations—systems, culture, store standards, supply chains, all of it has to be stitched together while the business keeps running. That integration burden can create openings for competitors that move faster and stay focused. And MatsukiyoCocokara isn’t trying to win the exact same game anyway. Its strength is differentiated: urban locations, beauty credibility, and private brand pull. The new leader’s suburban scale changes the competitive math, but it doesn’t erase MatsukiyoCocokara’s lane.

XVII. Conclusion: The Road Ahead

MatsukiyoCocokara & Co. is at another hinge moment. This is the company that defined Japan’s drugstore category for generations—then had to remake itself through a merger, absorb the shock of the pandemic, and come out the other side into a market that’s now being reshaped by consolidation at a scale Japan hasn’t seen before.

So the next set of choices actually matters. Does management chase more acquisitions to close the distance with the Welcia–Tsuruha giant? Does it lean harder into what makes Matsukiyo different—brand, beauty specialization, and private label—rather than trying to win a pure store-count arms race? Or does it treat Japan’s demographics as a ceiling and push faster into Asia, where the addressable market is still expanding?

What’s clear is that MatsukiyoCocokara has earned the right to play offense. It has shown resilience and strong execution: operating two major banners under one umbrella, expanding its network, and staying disciplined on costs while continuing to refresh the customer experience. The integration with Cocokara Fine didn’t just add stores; it created a platform that’s big enough to compete in a consolidated era, while still allowing the group to keep its brand edge where it counts.

And that brand edge is the quiet advantage that doesn’t show up neatly in a spreadsheet. The company’s story—from Kiyoshi Matsumoto’s pharmacy in 1932 to 22 years as Japan’s sales leader—created cultural capital that competitors can’t simply buy. In a category where trust matters, where shoppers reach for familiar names, and where tourist purchases are often guided by reputation, that heritage is a real asset.

Since October 2021, Matsumoto Kiyoshi and Cocokara Fine have operated together as MatsukiyoCocokara, with an explicit ambition to become Asia’s leading health and beauty retail chain. That goal may prove bold, or it may prove difficult. But either way, the arc is undeniable: a single local pharmacy in Chiba became a national institution—and now it’s trying to turn that institution into an Asian beauty empire.

The final chapters aren’t written yet. But the setup is as compelling as it gets.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music