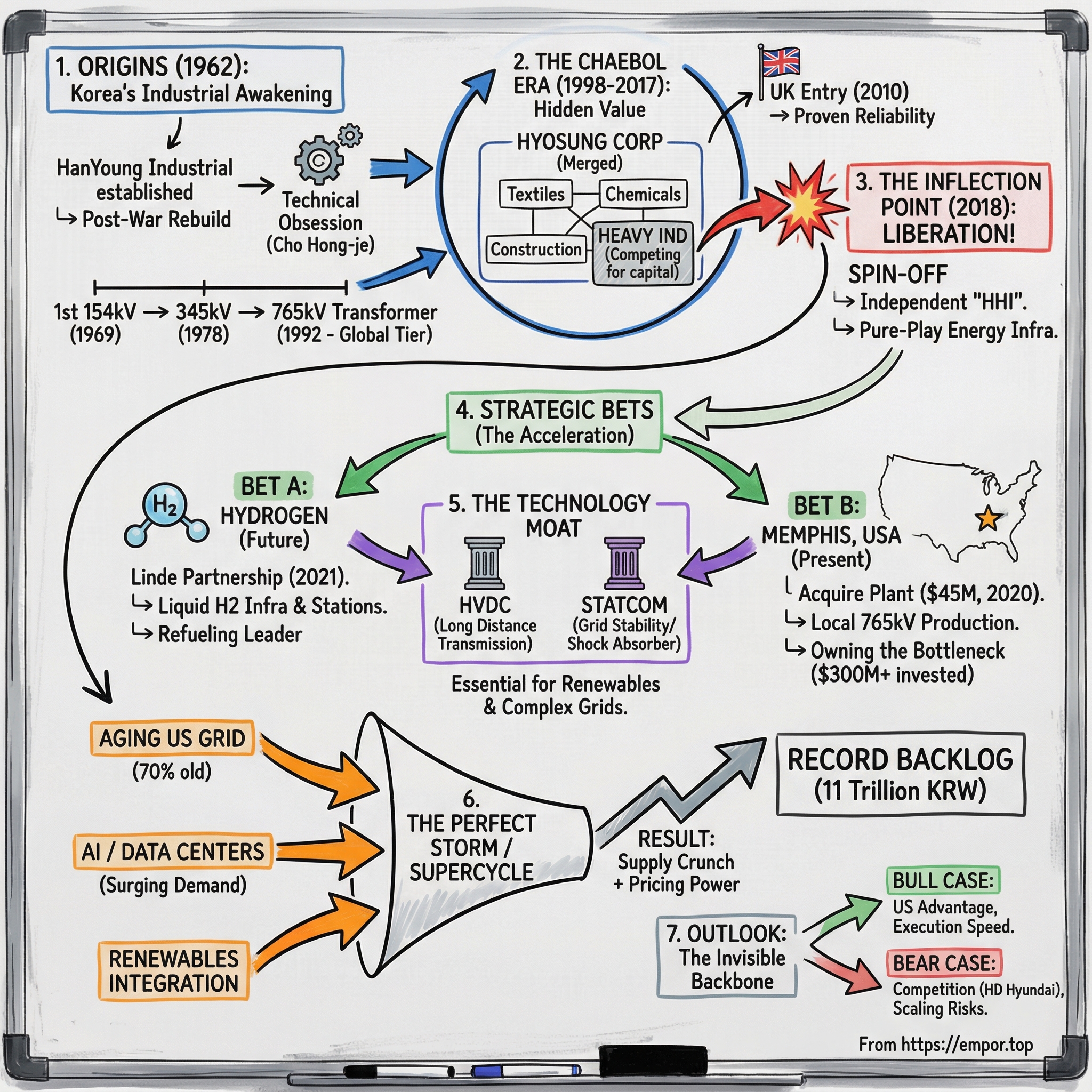

Hyosung Heavy Industries: Korea's Quiet Power Giant and the Energy Transformation Play

I. Introduction: The Invisible Backbone of the AI Revolution

Picture a sweltering summer night in Memphis, Tennessee. Near the Mississippi River, inside a sprawling industrial facility, the lights stay on and the work doesn’t stop. Crews are building enormous electrical transformers—machines so massive they’re measured in stories, not feet, and can weigh as much as 30 African elephants. When they roll out of this plant, they head straight into the arteries of the American grid, bound for utilities racing to keep up with a new kind of demand: the relentless power draw of AI-driven data centers.

The company running this operation isn’t a Silicon Valley celebrity. It isn’t even a household name in the industrial world. It’s Hyosung Heavy Industries—a South Korean power-equipment maker whose origins reach back to the hard rebuild after the Korean War.

Today, Hyosung Heavy Industries Corporation sits inside the Hyosung Group, and it makes its living in the unglamorous but essential parts of modern life: power transmission and distribution equipment, transformers, construction, and renewable energy-related solutions. The stuff that doesn’t trend on social media, but decides whether a city can grow, whether a factory can run, and whether the lights stay on.

And the numbers show that something has shifted. In 2024, Hyosung Heavy Industries reported revenue of 4.89 trillion KRW, up from 4.30 trillion KRW the year before. Earnings rose sharply as well, to 222.63 billion KRW.

But the real story isn’t that it grew. The story is that a company built around what might be the most boring-sounding product imaginable—a transformer—has become strategically important at exactly the right moment. Because every megatrend we talk about today eventually runs into the same bottleneck: the grid. AI infrastructure. Grid modernization. Renewable integration. Even the hydrogen economy. None of it works at scale without the equipment that moves and stabilizes power.

So here’s the question that drives this deep dive: how did a Korean transformer manufacturer, operating in relative obscurity for decades, place itself at the intersection of all of these forces at once?

The answer runs through three generations of a founding family, a $45 million acquisition that plenty of people inside the company didn’t want to touch, and a partnership with a German industrial gas giant that most observers didn’t realize would matter.

This is the story of Hyosung Heavy Industries: from post-war industrialization to conglomerate spin-off, from hydrogen bets to conquering America.

II. Origins: Korea's Industrial Awakening and the Birth of Heavy Industries

To understand Hyosung Heavy Industries, you have to start with South Korea in the early 1960s. The Korean War had ended less than a decade earlier, and the country was still operating in survival mode. Income levels were painfully low, infrastructure was thin, and the gap between ambition and capability was enormous.

What Korean leaders did understand—clearly and urgently—was the order of operations. Before you can industrialize, you need power. Before you can run factories, you need a grid. Electrification wasn’t a nice-to-have; it was the prerequisite.

That’s the context in which HanYoung Industrial Co., Ltd. was founded in May 1962—the company that would eventually become Hyosung Heavy Industries. The timing wasn’t an accident. Korea’s reconstruction push demanded domestic heavy-industry capacity, especially in power infrastructure. Importing transformers and other high-voltage equipment wasn’t just expensive; it was strategically uncomfortable. If Korea wanted to control its industrial destiny, it needed to build the machines that made the modern economy possible.

This story also sits inside the broader arc of Korea’s founding-era business giants. Late Samsung Group founder Lee Byung-chul and late Hyosung founder Cho Hong-je came from the same region in South Gyeongsang Province, attended the same elementary school, and later studied at Waseda University in Tokyo. They even established a corporate entity together in 1948 that’s now Samsung C&T. Cho went on to branch off and establish Hyosung Corporation in 1962.

Cho Hong-je—often referred to by his honorific name, “Manwoo”—was obsessed with technical competence. Not in the abstract, but as a strategy for survival. Hyosung would later institutionalize that belief by establishing Korea’s first private technological think tank in 1971, Hyosung R&DB Labs, built on the idea that securing original technology wasn’t optional. It was the whole game.

Then came the early proof point—the moment that turned a fledgling industrial bet into something real. In 1969, just seven years after founding, HanYoung Industrial developed Korea’s first 154kV extra-high-voltage transformer. It’s hard to overstate what that meant. This wasn’t simply a new product; it was a step toward self-sufficiency in the most critical layer of national infrastructure. Korea could now make, at home, one of the core components required to build a modern power grid.

Cho’s standard for what “good” looked like was famously uncompromising. One of his teachings captured it perfectly: you should be proficient in foreign languages enough to make people believe you are an American or Japanese until they hang up the phone. The message wasn’t really about language. It was about competing at the highest level—so convincingly that the world couldn’t dismiss you as a local player.

That early transformer breakthrough set the trajectory. But the real acceleration—Hyosung’s shift from promising manufacturer to national backbone—would arrive with the second generation.

III. Building Korea's Grid: The Hyosung Heavy Industries Era (1977–1998)

In 1975, the baton passed to the next generation. Cho Seok-rae would later go on to lead the broader Hyosung Group for decades, but even before he formally rose to the top, he was already pushing the heavy-industries business to move faster, aim higher, and build the kind of manufacturing footprint Korea would need if it wanted to industrialize on its own terms.

The turning point came in 1977. That year, the company completed its Changwon plant—an expansion of real industrial muscle—and pulled off a major technical win by developing a 362kV gas circuit breaker (GCB), cutting-edge equipment at the time. In November, the company made the shift official: it changed its name to Hyosung Heavy Industries Corporation.

Then it kept climbing. In 1978, Hyosung developed Korea’s first 345kV ultra-large transformer. It also succeeded in producing a 345kV three-phase 475,000kVA main transformer for power plants—an achievement that made it only the second company in Asia to reach that level of capability.

Through the 1980s and 1990s, Hyosung broadened its power equipment lineup, expanding deeper into power solutions and circuit breakers. The electric motor business scaled quickly too; by 1985, production had surpassed 1 million units. It wasn’t glamorous, but it was exactly how industrial empires are built: by learning to manufacture complex machines, reliably, at volume.

The real statement of arrival, though, came in the early 1990s. In 1992, Hyosung developed Korea’s first 765kV ultra-high-voltage transformer—technology operating at the highest transmission voltages used commercially anywhere in the world. This wasn’t a routine upgrade. It put Hyosung into a tiny global circle of manufacturers capable of building equipment for the top tier of national grids.

The company followed by pushing into gas-insulated switchgear (GIS), another critical category of grid infrastructure. In 1998, it developed the world’s third UHV-class GIS, proving it could compete at the frontier. And in 1999, Hyosung delivered what it called a world first: an 800kV 50kA 8000A GIS using a two-break design. Where prior systems relied on four breaks to handle those voltages, Hyosung’s engineers made two work—simpler, more compact, and a clear signal that the company wasn’t just catching up anymore.

Cho Seok-rae’s legacy inside Hyosung is often associated with technological upgrades across the group, including textiles. In 1987, he received the Gold Tower Order of Industrial Service Merit, the highest industrial honor awarded by the South Korean government.

By the end of the 1990s, Hyosung had become a pillar of Korea’s power transmission and distribution sector. But it was about to trade one kind of complexity—engineering—for another: life inside a merged conglomerate structure, where strategy, capital, and identity would all get messier before they got clearer.

IV. The Conglomerate Years: Life Inside Hyosung Corporation (1998–2017)

Then the late-’90s shock hit. The Asian Financial Crisis forced Korea’s chaebols into survival mode—sell assets, cut debt, simplify. In 1998, Hyosung T&C, Hyosung Trading, Hyosung Living Industry, and Hyosung Heavy Industries were merged into a single entity: Hyosung Corporation. It was, in many ways, a defensive consolidation—one company, tighter controls, a cleaner balance sheet.

For the heavy industries business, that new reality cut both ways. Inside a conglomerate, you get access to the group’s resources and patience—exactly what you want when your products are enormous, capital-intensive, and take years to design, certify, and deliver. Profits from faster-moving segments like textiles or chemicals could help fund heavy industry’s long-cycle investments. But you also inherit the conglomerate tradeoff: heavy industries had to compete internally for attention and capital against divisions with totally different economics and risk appetites.

Still, the engineering didn’t slow down. In the early 2000s, Hyosung Heavy Industries strengthened its reputation by commercializing GIS technology globally. The export machine was getting built—just not overnight.

A real milestone arrived in 2010, when Hyosung was selected as the primary supplier of high-voltage transformers for UK Power Networks. That wasn’t just another contract. The UK was a demanding, mature market, and breaking in—against established European players—signaled that Hyosung’s technology and reliability had reached a level the world’s toughest buyers would trust. From there, it steadily expanded its presence in Europe.

By this period, Hyosung Heavy Industries had also become more than “just” a grid-equipment business. It included heavy industries, construction, and other operations. As of 2023, its revenue mix reflected that split: 60% heavy industries, 39% construction, and 1% others. Construction ran through ChinHung International, established in 1959—useful diversification, but also a fundamentally different kind of business, with its own cycles and margin dynamics.

Meanwhile, behind the scenes, Hyosung had been working on what would become a key grid-stability technology. Since the late 1990s, it had researched STATCOM, and by 2015 it became the first in Korea—and the third globally—to commercialize an MMC (Modular Multi-Level Converter) STATCOM, using high-capacity, low-loss technology to stabilize power grids.

And yet, from the outside, much of this progress was hard to see. Investors in Hyosung Corporation weren’t buying a transformer and grid-technology company. They were buying a bundle: textiles, chemicals, construction, and heavy industries all rolled into one. There was no clean, pure-play way to value the power equipment business on its own.

That was about to change.

V. Inflection Point #1: The 2018 Spin-Off—Liberation Day

January 3, 2018 was Hyosung’s line in the sand. At a board meeting that day, the group decided to break up Hyosung Corporation and reorganize around a holding company structure—creating a new Hyosung Corporation on top, and four operating companies underneath it.

The split created four independent businesses: Hyosung TNC, Hyosung Advanced Materials, Hyosung Heavy Industries, and Hyosung Chemical. In other words, the power-equipment business that had spent two decades living inside a conglomerate bundle was finally getting its own name on the door again.

This wasn’t a small reshuffle. The spin-off came exactly twenty years after the crisis-era consolidation of 1998, when Hyosung T&C, Hyosung Trading, Hyosung Living Industry, and Hyosung Heavy Industries had been merged into one company in the wake of the Asian Financial Crisis. Under the new structure, the four operating subsidiaries represented about 60 percent of the group’s net worth, while the holding company represented about 40 percent.

So why split now?

A few forces were pushing in the same direction. Korea’s regulatory environment was steadily tightening around corporate governance, and holding-company structures were increasingly seen as a way to make ownership and performance easier to understand. The logic was straightforward: clearer lines, cleaner reporting, and a management system that put more explicit accountability on each business. The new Hyosung Corporation would focus on overseeing subsidiaries and making strategic investments, while each operating company would run its own day-to-day business.

The move also had a power dynamic. The transition was expected to strengthen the control of Chairman Cho Hyun-joon over the group.

Cho Hyun-joon—the third generation of the founding family—became chairman in 2017. Born on January 16, 1968, he studied in the United States and Japan, graduating from St. Paul High School, earning a bachelor’s degree in political science from Yale, and then a master’s degree in political science from Keio University Law School. Before rising inside Hyosung, he worked in the energy and crude oil import departments at Mitsubishi in Tokyo, and later in corporate sales at Morgan Stanley.

That background mattered. Hyosung had always been an engineering-driven group. Cho brought something different: a more explicitly global orientation, and firsthand exposure to energy markets and finance—experience that would shape the bets the company was about to make.

Mechanically, Hyosung Corporation—holding a 5.26 percent stake in each subsidiary—used a stock swap to build larger positions: 20.3 percent in Hyosung TNC, 32.5 percent in Hyosung Heavy Industries, 21.2 percent in Hyosung Advanced Materials, and 20.2 percent in Hyosung Chemical.

For Hyosung Heavy Industries, the real change was simpler than the legal structure: it could finally be seen clearly.

No more being valued as one segment inside a mixed bag of textiles, chemicals, and construction. As a standalone company, its exposure to the energy infrastructure buildout was suddenly obvious, and capital allocation could be driven by the needs of a power-equipment business—not conglomerate-wide tradeoffs. The narrative shifted from “a division inside a sprawling chaebol” to “a pure-play energy infrastructure company.”

And the timing couldn’t have been better. Within a year, Hyosung Heavy Industries would place two bets that would redefine its trajectory: a bet on hydrogen, and a bet on America.

VI. Inflection Point #2: The Hydrogen Bet—Partnering with Linde

Freshly spun out in 2018, Hyosung Heavy Industries suddenly had the freedom—and the pressure—to prove it could be more than a legacy grid-equipment maker. Starting in 2019, it began investing heavily in two areas that would define its next act: hydrogen energy and digital solutions aimed at sharpening its technical edge.

It didn’t begin with a moonshot. It began with a station.

In 2019, Hyosung Heavy Industries installed its first commercial hydrogen refueling station at the National Assembly in Yeouido, and it officially began operations that same year. In a country trying to jump-start a hydrogen economy, putting a station at one of the most visible addresses in Korea wasn’t just symbolic. It was a statement of intent.

Hyosung also moved quickly to make the technology its own. In 2019, it localized key components such as hydrogen dispensers and cooling systems—practical innovations that improved the experience on the ground with faster refueling, real-time visibility into refueling status, and more detailed error analysis.

Then came the move that turned “we’re participating” into “we’re building the backbone.”

In February 2021, Linde announced a partnership with Hyosung Corporation to build, own, and operate large-scale liquid hydrogen infrastructure in South Korea—explicitly aligned with the country’s decarbonization push and its net-zero-by-2050 ambition.

The structure mattered. Two joint ventures were formed: Hyosung Hydrogen and Linde Hydrogen. The responsibilities were split cleanly—one focused on sales, the other on production. And the capabilities were complementary. Linde brought proprietary hydrogen liquefaction technology, the same know-how behind a large share of the world’s liquid hydrogen production. Hyosung brought what global industrial players often lack in new markets: local execution, relationships, and an on-the-ground footprint in distribution and refueling infrastructure.

On behalf of the joint venture, Linde would build and operate what was described as Asia’s largest liquid hydrogen facility. Located in Ulsan, it was designed for capacity of over 30 tons per day—enough, according to the announcement, to fuel 100,000 cars and reduce up to 130,000 tons of tailpipe CO₂ emissions annually.

Hyosung Heavy Industries wasn’t treating this as a side project. It planned to invest 1 trillion won over five years to lift liquid hydrogen production capacity to 39,000 tons.

And while the partnership grabbed headlines, Hyosung’s real advantage in Korea was more straightforward: it knew how to build and run refueling infrastructure. The company had been in CNG refueling since 2000, entered hydrogen refueling in 2008, and drew on decades of experience in gas compression and refueling systems. In 2009, it built its first hydrogen refueling station in South Korea. Over time, that head start translated into scale—Hyosung Heavy Industries became the No. 1 player in Korea’s hydrogen refueling station market, backed by the country’s largest team of hydrogen refueling system specialists and a track record in gas refueling equipment.

The hydrogen bet also didn’t stop at the pump. In 2024, Hyosung Heavy Industries became the first in the world to commercialize a hydrogen engine generator powered entirely by hydrogen—electricity generation with 100% hydrogen and no carbon emissions during operation.

Hydrogen’s ultimate role in the energy system is still an open question. It may become a major energy carrier, or it may stay confined to specific industrial and mobility niches. But Hyosung’s approach was disciplined: partner with the global leader, secure leadership at home in refueling, and develop its own technology for hydrogen-based power. If hydrogen scales, Hyosung isn’t betting on a single point in the value chain—it has multiple ways to win.

VII. Inflection Point #3: The Memphis Acquisition—Conquering America

Of all the moves Hyosung Heavy Industries made in its post–spin-off era, one stands out for how unglamorous it looked at the time—and how big it might end up being: buying a transformer plant in Memphis for $45 million.

In 2020, Hyosung acquired the facility from Japan’s Mitsubishi Electric Power Products. The immediate motivation was defensive. The first Trump administration was threatening heavy tariffs on imported equipment, and Hyosung didn’t want its access to the U.S. market held hostage by trade policy.

Inside the company, the deal wasn’t universally loved. Acquisitions come with the usual fear list—operational risk, cultural risk, “are we buying someone else’s problems?” But Hyosung says Chairman Cho Hyun-joon pushed it through anyway. His logic was straightforward: the U.S. power market was going to grow, and the Memphis site had something that’s hard to manufacture on a spreadsheet—space. Big land for big equipment, and room to expand.

In hindsight, that call looks less like a gamble and more like a timing masterclass.

Because to understand why Memphis matters, you have to understand what’s happening to the American grid. Roughly 70% of U.S. large power transformers are more than 25 years old. That’s uncomfortably close to the back half of a typical transformer’s lifespan. The result is exactly what you’d expect: rising maintenance costs, reliability problems, and an urgent need to replace aging infrastructure. The U.S. Department of Energy has estimated that upgrading the grid will require around $130 billion in the near future.

And here’s the kicker: the industry can’t just “turn on” transformer supply. Over the last decade, transformer prices jumped dramatically, pressured by rising raw-material costs, surging demand, and supply-chain bottlenecks. Lead times stretched out too—since 2021, delivery timelines have ballooned to nearly three years. When utilities need equipment and manufacturers can’t deliver quickly, the leverage shifts.

This is the market Hyosung walked into with a local factory.

Hyosung’s U.S. subsidiary, Hyosung HICO, is the only producer in the country making 765kV transformers domestically—some of the highest-voltage, most critical units on the grid. Hyosung estimates it has supplied nearly half of all 765kV transformers installed in the U.S. since 2010.

Demand has only gotten hotter. The U.S. isn’t just replacing old equipment; it’s also trying to feed a new class of electricity customers—AI data centers—on top of broader electrification. Global Market Insights projects the U.S. transformer market will more than double from 2024 to 2034.

So Hyosung started expanding—fast.

In November 2025, Hyosung Heavy Industries announced it would invest $157 million into the Memphis power transformer plant, aiming to lift production capacity by more than 50% by 2028. Local officials also announced another expansion plan: Hyosung HICO would invest $50.8 million and create 123 new jobs in Shelby County.

It wasn’t the first time Hyosung had stepped on the gas. Earlier in 2025, the company announced a separate commitment—$51 million and another 123 jobs. Since acquiring the facility from Mitsubishi Electric Power Products in 2019, when it was close to shutting down, Hyosung has invested more than $300 million into the Memphis site.

The goal is scale. Once the upgrades are complete, Hyosung expects the plant’s capacity to rise by roughly half, cementing it as one of the largest domestic power transformer operations in the U.S.—and still the only U.S. facility dedicated to manufacturing 765kV transformers.

The company’s financials show what a supply-constrained, demand-surging market can do for the right supplier. Hyosung Heavy Industries posted record quarterly results in the third quarter of this year, and its global order backlog reached 11 trillion won, up sharply from the year before. In 2024, operating profit hit a record 362.5 billion won, and forecasts for this year point even higher.

Hyosung has been explicit about what Memphis is really for. “Today’s expansion of our Memphis transformer facility marks a major milestone in our U.S. growth strategy and underscores our vision to become the #1 supplier of large power transformers in the country by 2027 and the leading supplier of solutions by the end of this decade,” said Jason Neal, President of Hyosung HICO.

In other words: the hydrogen bet was about the future. Memphis was about the present—and about owning the bottleneck. While others hesitated, Hyosung moved early to plant manufacturing capacity inside the world’s most important power market, just as the grid hit its breaking point.

VIII. The Technology Moat: HVDC, STATCOM, and Grid Modernization

Memphis explains why Hyosung matters right now. But the deeper reason utilities keep coming back isn’t just transformer capacity. It’s that Hyosung has spent years building a second layer of advantage in the harder, more modern problems of the grid—moving power farther, stabilizing it faster, and making renewables behave like reliable baseload.

As wind and solar penetration rises, grids start to struggle in ways old-school hardware wasn’t designed to handle. Power shows up where people don’t live, it comes and goes with the weather, and it can push voltage and frequency out of safe ranges. This is where Hyosung’s technology moat starts to look less like “heavy industry” and more like power electronics.

One cornerstone is HVDC—high-voltage direct current transmission. Hyosung Heavy Industries was the first company in Korea to successfully develop an HVDC system using the MMC method, the most advanced approach for voltage converters.

The reason HVDC is such a big deal is simple: long distance. Traditional AC transmission loses more energy over long runs. DC is more efficient for moving large amounts of power over long distances, but it demands extremely sophisticated conversion equipment at both ends. That makes HVDC a key enabling technology for things like offshore wind, renewable generation located far from cities, and interconnections between regions or even countries.

Hyosung pushed that capability into the real world. In 2024, it became the first company in Korea to localize 200MW voltage-type HVDC technology using its own expertise. The system was installed at the Yangju substation in Gyeonggi Province, where it plays a stabilizing role for the regional power grid.

The other pillar is STATCOM, short for static synchronous compensator. Think of STATCOM as the grid’s shock absorber. It helps compensate reactive power, keeps voltage steady, and increases the usable capacity of transmission lines—all while protecting stability. In a grid with lots of renewables, those functions go from “nice to have” to “mandatory.”

Hyosung didn’t just build STATCOMs. It scaled them. The company installed what it describes as the world’s single largest STATCOM ever installed, using its own MMC technology to achieve both large capacity and low loss. The logic is the same as with HVDC: in a volatile grid, the winners aren’t just the companies that can move power—they’re the ones that can keep it well-behaved.

Chairman Cho Hyun-joon framed the strategic ambition clearly: “Hyosung is the only company in Korea to possess technology to commercialize STATCOMs. If we succeed in completing our HVDC system verification project currently going on jointly with KEPCO, we will be able to strengthen our leading position in the next-generation power technology.”

Under the hood, Hyosung’s STATCOM lineup shares the same MMC foundation as its HVDC equipment, which gives it durability, stability, and a cleaner path to scaling up. The company says a single STATCOM installation can reach up to ±500Mva in capacity.

And Hyosung is already aiming at what comes after the 200MW era. It has developed valve technology for 2GW-class voltage-source HVDC—an order-of-magnitude leap from 200MW systems—positioning the company for the massive, future-facing HVDC projects that will be needed to integrate offshore wind and build long-distance transmission corridors.

This is why Hyosung isn’t just riding the transformer replacement cycle. Transformers get you onto the grid. HVDC and STATCOM help you reshape it. As renewable energy spreads and grids get more complex, Hyosung’s bet is that the value shifts toward the companies that can stabilize, convert, and control electricity—not just carry it.

IX. The Business Model: Power, Construction, and Conglomerate DNA

By now, Hyosung Heavy Industries can sound like “the transformer company.” But the way it actually makes money is broader—and that mix is part of what makes the business interesting.

On the power side, it sells the hardware that utilities and grid operators can’t function without: extra-high-voltage transformers, distribution transformers, shunt reactors, extra-high-voltage circuit breakers, switchgear, and mobile substations. Then it layers on systems and software: STATCOM, DC transmission and distribution, ESS, microgrids, solar solutions, and digital tools like asset management and preventive diagnostics. It even has a welding solutions business, with products like arc welders and resistance welders.

And then there’s the other pillar: construction.

Through ChinHung International, Inc.—established in 1959—Hyosung Heavy Industries runs building construction, SOC projects, and housing development. Its residential projects carry the Hyosung Harrington Place brand. This part of the portfolio is legacy Hyosung DNA: a conglomerate-style mix of capabilities under one roof.

But it also deserves scrutiny, because construction behaves nothing like power equipment. Construction is cyclical, tied to domestic real estate conditions, and generally runs on lower margins. Power equipment, especially now, is riding more structural demand—aging grid infrastructure, renewable integration, and data-center growth—that’s less correlated with the Korean housing cycle.

You can see that split in the numbers. In 2023, revenue was roughly 60% heavy industries, 39% construction, and 1% other.

What’s changing is where the growth is coming from. Heavy industries exports rose from about KRW 565 billion in 2021 to KRW 665 billion in 2022, then jumped to around KRW 1.2 trillion in 2023. Over the same period, domestic heavy industries sales stayed relatively steady at around KRW 1 trillion. The direction is clear: more of the company is being pulled outward by global demand, rather than inward by local cycles.

Operationally, the core franchise remains power transmission and distribution. Hyosung Heavy Industries holds the highest cumulative market share in Korea’s power transmission and distribution sector, and it doesn’t just ship equipment; it delivers the full package—engineering, design, manufacturing, installation, testing, and maintenance.

And that full-stack capability is what turns “transformer manufacturing” into a moat. Hyosung serves customers in more than 70 countries, designing, building, and testing to meet each country’s standards. At the Changwon plant alone, it has produced more than 7,500 extra-high-voltage transformers.

That production history isn’t just a trophy stat—it’s accumulated learning. Large transformers are effectively custom machines, built for specific grids, operating conditions, and regulatory requirements. Decades of design iterations, manufacturing discipline, and quality control become a kind of institutional memory that competitors can’t buy quickly, no matter how much capital they throw at a new factory.

X. Porter's Five Forces Analysis

1. Threat of New Entrants: LOW

In theory, “making transformers” sounds like something any well-funded industrial player could decide to do. In practice, ultra-high-voltage equipment is a club with a long, unforgiving apprenticeship.

You need decades of accumulated design and manufacturing know-how, specialized testing facilities, and a stack of certifications that utilities won’t hand out quickly. Hyosung Heavy Industries has been building at the frontier for years—one example: it was the first in Korea and the second globally to develop a 1,100kV GIS using proprietary technology.

Then there’s the sheer capital requirement. Since acquiring the facility from Mitsubishi Electric Power Products in 2019, Hyosung has invested more than $300 million into the Memphis plant. That kind of commitment isn’t just expensive; it’s a warning label to would-be entrants.

And even if you have the money and the engineers, you still have to get chosen. Utility qualification processes often take years, and for equipment expected to sit on the grid for decades, buyers have little appetite to gamble on an unproven supplier.

2. Bargaining Power of Suppliers: MODERATE

Transformers are, at their core, engineered assemblies of a few critical inputs: copper windings, core steel, and insulating materials. Those aren’t commodities you can always source freely, especially at the quality and volumes required for large power transformers.

Supply-chain disruption has been a real constraint in North America, particularly for materials like copper and silicon steel and other insulating components—many of which are sourced internationally. When those inputs tighten, it doesn’t just raise costs; it slows the whole market down.

Hyosung isn’t powerless here. Scale helps in procurement, and its broader capabilities in engineering and construction can reduce dependency in certain areas. But the underlying reality remains: some parts of the bill of materials are controlled by a relatively limited supplier base.

3. Bargaining Power of Buyers: MODERATE-TO-LOW

On paper, the buyers look powerful. Utilities and governments are big, concentrated customers with professional procurement teams and long memories.

But the grid is aging, and time is not on the buyers’ side. Around 70% of U.S. power transformers are more than 25 years old, which translates into rising maintenance costs and reliability risk. Replacement isn’t optional; it’s inevitable.

Now layer in supply constraints. Since 2021, transformer lead times have stretched dramatically—out to roughly 150 weeks in some cases. When delivery slots are scarce, the negotiating leverage shifts. For critical infrastructure, reliability and certification often matter more than price, and that reality favors proven manufacturers.

4. Threat of Substitutes: VERY LOW

There’s no workaround here. You can’t transmit AC power at scale without stepping voltage up and down, and that means transformers.

New technologies don’t replace that need—they pile on top of it. HVDC and STATCOM complement traditional grid equipment, and modernization tends to create new categories of demand rather than eliminate the old ones.

5. Competitive Rivalry: MODERATE-TO-HIGH

This is a tough neighborhood. The global heavyweight set includes Siemens, ABB/Hitachi Energy, and GE Vernova—and Hyosung increasingly belongs in that conversation.

Competition is also intensifying closer to home. Hyosung’s rival HD Hyundai Electric announced plans to expand transformer output at its U.S. plant in Alabama, aiming to raise annual capacity from 100 units to 150, supported by a major investment program.

But here’s the catch: rivalry is happening inside a market that’s still undersupplied. Demand is outrunning capacity globally, which means the fight is less about stealing customers and more about who can actually deliver. And at the very top end—765 kV transformers—only a small number of companies worldwide can manufacture them. In that tier, capability is the constraint, and the manufacturers who have it hold the leverage.

XI. Hamilton's 7 Powers Analysis

1. Scale Economies: STRONG

At the Changwon plant alone, Hyosung has produced more than 7,500 ultra-high-voltage transformers. That kind of volume isn’t just a bragging right—it’s a learning curve you can’t fake. Each unit makes the next one cheaper, faster, and more reliable, while letting Hyosung spread massive fixed costs—R&D, testing facilities, specialized tooling, and highly skilled labor—across a far larger base.

2. Network Effects: WEAK TO MODERATE

Transformer manufacturing doesn’t create classic network effects. But there is a subtle version of it: the installed base. Once a utility has Hyosung equipment in service, standardization starts to pay dividends. Adding compatible units is simpler, maintenance teams build familiarity, spare parts and procedures get streamlined, and “staying with what works” becomes the default.

3. Counter-Positioning: STRONG

Hyosung’s push into 765kV transformers—and then into U.S. local production—was a bet many competitors didn’t want to make. While others hesitated and continued to rely on imports, Hyosung moved earlier and more decisively. That mattered when tariff threats turned imported equipment into a business risk. In a market where lead times and policy can swing procurement decisions, being local wasn’t just cheaper—it was safer.

4. Switching Costs: STRONG

Utilities don’t swap transformer suppliers the way consumers swap brands. Grid stability is the product, and nobody wants to introduce unnecessary uncertainty into a system that has to run for decades.

The biggest switching cost isn’t financial—it’s operational risk. Utilities can spend years qualifying a supplier, and once a manufacturer is proven, moving to a new one means taking on the possibility that something underperforms in the field. When the downside is a grid event, the bar to switch is extremely high.

5. Branding: MODERATE

In industrial infrastructure, branding isn’t about logos—it’s about credibility earned under load, over time. Hyosung’s “brand” is its track record: equipment operating reliably across dozens of countries.

That’s why the UK matters. Since entering the UK market in 2010, Hyosung has supplied and maintained ultra-high-voltage transformers there. Fifteen years of continuous supply in a demanding market doesn’t just generate revenue; it builds reputational capital that travels.

6. Cornered Resource: MODERATE TO STRONG

Hyosung HICO is the only producer in the U.S. that manufactures 765kV transformers domestically. That is a genuine cornered resource: a capability that is both scarce and hard to replicate quickly.

The Memphis site adds to that advantage. It’s a large facility—about 200 acres—with access to both rail and water transportation. The land, logistics, and accumulated manufacturing know-how for 765kV units form a bundle that competitors can’t simply copy by writing a check.

7. Process Power: STRONG

In a supply-constrained market, speed becomes strategy. South Korean manufacturers have a reputation for reliability and faster delivery, and Hyosung has benefited from that perception and the underlying execution behind it.

That operational discipline can translate into pricing power too. When demand runs ahead of supply, customers pay for certainty—on delivery schedules, on quality, and on performance. And that kind of process advantage isn’t a single innovation; it’s the compound result of decades of manufacturing optimization and institutional learning.

XII. Competition and Market Dynamics

For a long time, Korea’s heavy electrical equipment makers were viewed as strong regional players. Now, in transformers especially, they’re starting to look like the center of gravity. The main trio—Hyosung Heavy Industries, HD Hyundai Electric, and LS Electric—has been winning in global markets, and nowhere is that shift more visible than the United States.

The U.S. is the world’s second-largest electricity consumer, and it’s in the middle of an equipment crunch: grid replacement, renewable buildouts, and the infrastructure around EV charging all stack demand on top of demand. Korean manufacturers have leaned into that moment. Orders have been so strong that some product slots were effectively sold out through 2025. LS Electric, meanwhile, has landed major supply deals that helped it start breaking into the U.S. market in a meaningful way.

On the factory floor, the strain shows up as a kind of industrial overtime economy. Hyosung and HD Hyundai have been running their U.S. plants beyond nameplate capacity—nights, weekends, and whatever else it takes. And when local production still isn’t enough, exports from South Korea fill the gap.

Hyosung’s closest Korean rival is HD Hyundai Electric. It entered the transformer business in 1978 and has spent decades building a global footprint, supplying equipment to about 70 countries. Now it’s doubling down on the U.S., announcing a major investment to expand transformer capacity at its Alabama facility. And it’s not just adding volume—it’s moving up the voltage ladder. Since 1999, HD Hyundai has delivered more than 160 contracts for 765kV transformers worldwide, and its Alabama expansion is intended to add new production capability for 765kV equipment, with operations expected to begin in 2027.

The most telling part of this competition is how little it resembles a classic price war. Hyosung and HD Hyundai compete directly, but demand has been strong enough that both have been expanding capacity while raising prices. Even with higher prices, HD Hyundai still signed large U.S. deals in the second quarter.

Hyosung’s momentum isn’t just an American story, either. Europe has been another major proving ground. The company has built a track record there that keeps compounding—particularly in the UK, where it holds the No. 1 market share in the 400kV transformer market for transmission power companies across the UK, Scotland, and Norway. It has continued to add ultra-high-voltage power equipment contracts across major European markets including the UK, Sweden, and Spain.

All of this is happening in a world where the incumbents are still giants. The global power-equipment heavyweights—Siemens, ABB/Hitachi Energy, GE Vernova, and Schneider Electric—bring broader portfolios and deep, decades-long customer relationships, especially in their home markets. But the Korean manufacturers have demonstrated they can win where it counts: on technology, on quality, and—at a time when lead times can make or break a grid project—on delivery.

XIII. Bull Case: Riding the Power Supercycle

The bull case for Hyosung Heavy Industries is that it’s positioned right where multiple, long-running forces collide—and that those forces all point to the same thing: more hardware, more lead time pressure, and more willingness to pay for proven suppliers.

1. Aging Infrastructure Replacement

America’s grid is getting old in the most literal way. Much of it was built in the 1960s and 1970s, and by the Department of Energy’s own 2015 review, about 70% of U.S. transmission lines were already more than 25 years old.

And it’s not just the big transmission backbone. The U.S. has tens of millions of distribution transformers in service today. Looking ahead, projections call for a huge step-up in transformer demand through mid-century. Electricity demand is expected to be meaningfully higher by 2030 than it was in 2021, and higher still by 2035—forcing utilities into a long, expensive replacement-and-expansion cycle. The practical takeaway is simple: the next couple of decades likely require millions of new transformers.

2. AI and Data Center Expansion

Then there’s the new load that’s showing up fast: data centers.

Wood Mackenzie expects U.S. power companies to secure vast amounts of new electricity supply for data centers, with much more needed by 2040. The International Energy Agency expects data center electricity consumption to double by 2026, alongside global power demand rising at a steady clip. For grid equipment makers, that translates into more substations, more interconnections, more high-voltage gear—and, again, more transformers.

3. Renewable Energy Integration

Renewables don’t just need generation. They need grid architecture.

Every wind farm and solar installation requires transformers at multiple stages—from internal collection systems to the point where the project connects to the main grid. NREL estimates that a utility-scale wind farm typically uses dozens of transformers, depending on size and design. Multiply that by the buildout underway, and it’s obvious why transformer demand doesn’t just rise with renewables—it compounds.

4. Pricing Power

When demand surges and supply can’t ramp fast enough, pricing power shows up quickly.

Hyosung has benefited from this environment, raising prices on electrical equipment such as transformers and circuit breakers by about 20% versus two years earlier. With lead times stretching out to roughly 150 weeks and demand still outstripping supply, the argument is that this isn’t a one-quarter phenomenon—it could persist for years.

5. U.S. Manufacturing Advantage

Hyosung’s Memphis footprint isn’t just about capacity. It’s about reducing friction.

With a transformer plant in Tennessee, Hyosung can pursue U.S. orders without the overhang of tariff risk that comes with imports. Local manufacturing doesn’t guarantee wins, but it removes a major source of uncertainty—especially in utility procurement, where reliability of delivery can matter as much as the equipment itself.

6. Backlog Visibility

Finally, there’s the backlog.

Hyosung reported a global order backlog of 11 trillion won, up 52% from the same period a year earlier. A backlog that large—more than twice annual revenue—doesn’t just suggest strong demand. It creates unusually clear forward visibility, which is exactly what investors look for in a capital-intensive industrial business.

XIV. Bear Case: Risks and Challenges

The bull case is easy to love: a supply-constrained market, surging demand, and Hyosung sitting right in the choke point. The bear case is what happens if any of the assumptions behind that setup crack.

1. Execution Risk on Capacity Expansion

Hyosung is trying to scale fast, and in heavy electrical equipment, speed is never free. Rapid capacity expansion can mean quality issues, cost overruns, or schedules that slip. The new facilities at the Memphis plant are expected to be operational next year. If that timeline moves, or if ramp-up is bumpy, the damage wouldn’t just be financial—it could show up in customer trust, which is everything in utility procurement.

2. Competition Intensifying

Hyosung’s U.S. footprint looks like a first-mover advantage—until it isn’t. HD Hyundai Electric is building new production capacity for 765 kV equipment at its Alabama site, with operations expected to begin in 2027. If competitors bring meaningful new supply online, Hyosung’s leverage could shrink. And if supply finally catches up to demand, today’s pricing power can fade faster than anyone expects.

3. Construction Business Cyclicality

Hyosung Heavy Industries isn’t a pure-play grid story. Construction represented 39% of revenue, and that business is tied to domestic real estate cycles. A downturn in the Korean housing market could weigh on overall results even if transformers and switchgear keep humming.

4. Hydrogen Bet Uncertainty

Hydrogen is still a “show me” market. Hyosung Heavy Industries planned to invest 1 trillion won over five years to raise liquid hydrogen production capacity to 39,000 tons. If adoption moves slower than expected—or stays limited to niche use cases—those investments may struggle to earn attractive returns. This is the risk of building infrastructure ahead of certainty: you can end up early instead of right.

5. Raw Material and Supply Chain Risks

Transformers look like engineered products, but they’re also, in part, a materials business. Copper, silicon steel, and specialized insulating materials are core inputs. The U.S. imported over 70% of its silicon steel requirements in 2023, which leaves manufacturers exposed to disruption, geopolitics, and price swings. Any sustained increase in input costs—or a supply shock—can pressure margins and delivery schedules.

6. Geopolitical Considerations

Hyosung operates in a sensitive zone: critical infrastructure. As a Korean manufacturer supplying the U.S. and Europe, it faces risks ranging from tariff shifts and trade policy changes to heightened regulatory scrutiny and security concerns about foreign suppliers. Even if the product is best-in-class, the politics can still change the playing field.

7. Family Governance and Succession

Finally, there’s governance—always a real variable in chaebol stories. Hyosung Group embarked on a major restructuring, splitting into two holding companies and moving toward independent management by brothers Cho Hyun-joon and Cho Hyun-sang. The decision was solidified on June 14 at an extraordinary general meeting of shareholders, where the split plan was approved as proposed.

Transitions like that can be clean—or they can be distracting. Even when the strategy is sound, succession and control changes introduce execution risk, and markets tend to price that uncertainty in until the new structure proves it works.

XV. Key Performance Indicators to Monitor

If you want a simple dashboard for whether Hyosung Heavy Industries’ thesis is working—or starting to crack—there are three metrics that tell you most of what you need to know.

1. Order Backlog (Current: 11 trillion KRW)

The backlog is the company’s best window into the future. It’s a proxy for customer confidence, pricing power, and whether Hyosung is winning real projects, not just headlines.

If the backlog keeps growing, it usually means demand is still outrunning supply and Hyosung is holding its position. If it starts to shrink, you have to ask why: is capacity finally catching up across the industry, are competitors taking share, or are customers simply pushing projects out? It’s also worth watching backlog relative to revenue, which currently sits at roughly a little over two years of sales.

2. Heavy Industries Export Growth Rate (2023: 45.4% two-year CAGR)

Exports are the clearest signal that Hyosung is becoming a global grid supplier, not just a Korea-centric manufacturer with a construction business attached.

Heavy industries exports rose from KRW 565.4 billion in 2021 to KRW 1.1953 trillion in 2023, translating to a 45.4% two-year average growth rate. If that kind of export momentum holds, it reinforces the story that Hyosung is riding structural global demand and diversifying away from Korea’s construction cycle. If it slows sharply, it’s a cue to dig into competitive pressures, customer concentration, or shifting demand in key markets like the U.S. and Europe.

3. Operating Margin (2024: approximately 7.4%)

Operating margin is where the narrative meets reality. In a supply-constrained market, a strong backlog should convert into healthy profitability—unless something is going wrong inside the machine.

If margins hold steady or improve, it suggests Hyosung is capturing pricing power while keeping execution tight. If margins compress materially, the usual suspects come into focus fast: raw material inflation, production bottlenecks, warranty or quality issues, or expansion growing pains—especially as new capacity comes online.

Together, these three—backlog, exports, and operating margin—function like an early warning system. They tell you whether demand is still there, whether Hyosung is winning globally, and whether the company is converting opportunity into durable earnings.

XVI. Conclusion: The Transformer Supercycle and Hyosung's Position

Hyosung Heavy Industries now sits where multiple structural forces collide: aging grids that have to be replaced, electricity demand that’s spiking thanks to AI and data centers, and a renewable buildout that requires far more control hardware than most people realize. That positioning didn’t happen by accident. It’s the compound result of decades of engineering experience, disciplined investment, and a willingness to make bets that looked unremarkable—until they didn’t.

The Memphis acquisition is the cleanest example. When Chairman Cho Hyun-joon pushed for the plant despite internal skepticism, he wasn’t chasing a headline. He was buying insurance against tariff risk and, more importantly, buying a production foothold inside the market that was about to become the world’s loudest transformer bottleneck. That future has now arrived. Hyosung Heavy Industries was projected to deliver record results this year, with sales forecast to reach KRW 5 trillion.

Zoom out one level, and you start to hear the phrase “super-cycle” more often—industry experts describing a long boom in global power equipment over the next decade. Whether you love that term or hate it, the underlying reality is hard to argue with: we’re rebuilding and expanding the grid at the same time, and the queue for critical equipment is already long.

There’s a symmetry to Hyosung’s arc. It started in 1962, in a country rebuilding from war, making the first domestic transformers Korea needed to electrify and industrialize. It grew alongside the country’s own power grid. And now, decades later, it’s playing a similar role on a much larger stage—helping other countries modernize, stabilize, and expand the systems that power their economies.

Because when the world talks about the future, it usually talks about software, chips, and models. But when the future has to plug in—when a data center needs to interconnect, when a wind farm has to push power across hundreds of miles, when an old substation has to be replaced—there’s only a small set of companies that can actually deliver the hardware. Transformers. HVDC. STATCOM. The unsexy, high-consequence building blocks of the grid.

Hyosung Heavy Industries doesn’t look like the future in the way people are trained to recognize. It doesn’t get the cultural oxygen that semiconductors or AI companies do. But it keeps showing up at the constraint.

"A reliable and efficient power grid is the backbone of a nation's competitiveness, and in this era of rapid digital transformation, it also serves as the cornerstone of the AI industry and many other key industries."

That’s the opportunity—and the responsibility. In the next phase of the energy transition, essentiality is the moat. And Hyosung Heavy Industries has quietly built itself into one of the most strategically important suppliers on the planet.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music