Toyo Suisan Kaisha: The Quiet Empire Behind Maruchan's Ramen Revolution

I. Introduction: The Fish Trader That Conquered America's Pantries

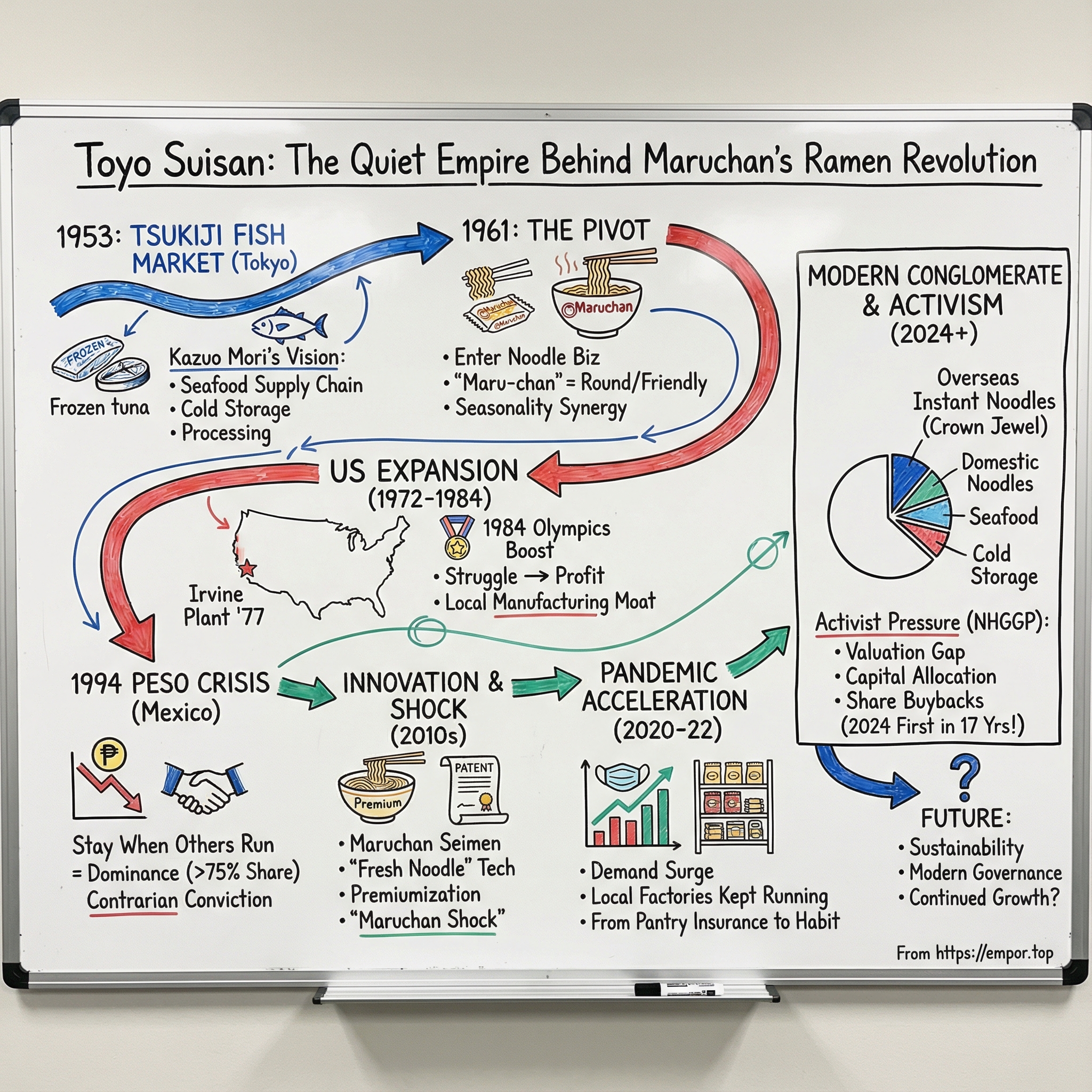

Picture a college dorm at 2 AM. A bleary-eyed student shuffles to a tiny kitchenette, tears open a packet of Maruchan ramen, and three minutes later is holding a steaming bowl of salty, savory comfort. That small ritual—repeated endlessly across North America—sits on top of one of the more unlikely corporate transformations in modern Japanese business.

Because the company behind that packet didn’t start as a noodle company at all. It started as a frozen tuna exporter at Tokyo’s Tsukiji Fish Market.

And here’s the twist: this quiet Japanese conglomerate, largely invisible to everyday consumers and even many investors, went on to dominate the U.S. instant ramen market—roughly 70% by volume and about 45% by sales value—and built an even more overwhelming position in Mexico, where it holds well over three-quarters of the market.

That company is Toyo Suisan Kaisha, Ltd.—usually just called Toyo Suisan. It sells ramen under the Maruchan brand, but it also operates in seafood, frozen foods, refrigerated foods, and cold storage. In fact, it ranks as the fourth-largest transnational seafood corporation in the world. Yet if you ask most Americans who’ve eaten Maruchan who makes it, they won’t say “Toyo Suisan.” They’ll just say “ramen.”

That gap—global leadership on one hand, near-total anonymity on the other—is the Toyo Suisan paradox. It feeds hundreds of millions of people, but it doesn’t live in the cultural spotlight the way many consumer empires do.

The engine of the whole machine is its Overseas instant noodle business. That segment, led by North America, has become the crown jewel inside a company that still carries a lot of legacy businesses—seafood processing, warehouses, refrigeration—the infrastructure of its original life.

This is the story of how a fish trader named Kazuo Mori built Toyo Suisan; how the company bet on instant noodles and made Maruchan a household staple; how it nearly collapsed in America before clawing its way back; how it stayed in Mexico when others ran during a crisis; and how it ended up with an almost unfair position in North American ramen.

And in the background, there’s a second story running in parallel: why, despite what activists describe as exceptional operating performance and “crown jewel” assets, Toyo Suisan has traded at what they argue is a steep discount to its intrinsic value—and what investors are now trying to change.

At its core, Toyo Suisan is a story about timing and contrarian conviction. About building moats with factories instead of marketing. And about how being the second mover—when you move into the right places—can beat the pioneer.

II. Post-War Japan and The Founding Vision (1953-1960)

In the spring of 1953, Japan was still climbing out of the rubble of World War II. The occupation had ended only a year earlier. Food was still a national obsession. And in Tokyo, Tsukiji Fish Market—scarred, noisy, half-rebuilt—was once again becoming the nerve center of how the country fed itself.

That’s where Kazuo Mori started Toyo Suisan.

On March 25, 1953, Mori founded Toyo Suisan Kaisha, Ltd. as a marine-products business: buying, selling, exporting, and distributing seafood, with operations centered at Tsukiji. It was modest in its beginnings, but perfectly placed. Japan’s recovery was accelerating, and with it came a simple, urgent need: cheap, reliable protein.

Mori understood the opening. The fishing industry had been battered by the war, but demand was surging. If you could rebuild the supply chain—source, process, move product efficiently—you could build a real company. Toyo Suisan focused early on frozen tuna exports and the domestic distribution of marine products, helping restore seafood supply lines at a moment when the country needed every calorie it could get.

Even the name was a mission statement. “Toyo Suisan” translates to “Oriental Marine Products.” This was, at its core, a sea business.

But Mori wasn’t trying to stay a middleman forever. Trading is fine. Owning the infrastructure is better. Owning processing is better still. In 1955, Toyo Suisan entered the cold-storage business. In 1956, it began producing and selling processed products, including fish sausage. That shift mattered: cold storage and processing weren’t just new revenue streams—they were capabilities. They meant control over quality, inventory, and distribution. They meant Toyo Suisan could scale.

Fish sausage, in particular, was a smart fit for the times. Western-style processed meats were seen as modern, but pork and beef could be expensive and hard to come by. Fish sausage offered an affordable alternative that played to Japan’s strengths in marine resources. It also brought a new kind of operational challenge: demand wasn’t steady. It spiked in the summer, when people gathered, traveled, and ate outdoors.

And that seasonality left Mori staring at a familiar manufacturing problem: what do you do with a factory when the calendar turns and demand drops?

By 1960, Toyo Suisan had something most young food companies didn’t: cold-chain infrastructure, processing know-how, and distribution reach. Built for seafood, yes—but surprisingly adaptable. The company had laid the tracks. It just hadn’t yet found the locomotive that would run on them.

That would come next—from a product invented only a few years earlier, by a rival, that would soon remake Toyo Suisan’s future.

III. The Pivot That Changed Everything: Entering Instant Noodles (1961-1970)

To understand why Toyo Suisan jumped into instant noodles, you have to start with the man who lit the fuse.

On August 25, 1958, Momofuku Ando launched Chicken Ramen, the world’s first instant noodles. He’d spent months tinkering with a breakthrough process—flash-frying cooked noodles so they could be revived with hot water. The result was almost unbelievable for the time: ramen at home in minutes. People called it “magic ramen.”

Ando wasn’t just chasing a clever product. In the years after World War II, Japan’s food shortages were brutal. Ando had watched hunger up close: people lining up in the cold for a single bowl at street stalls, others collapsing from malnutrition. He became convinced that the country needed something affordable, filling, and easy to prepare—food that didn’t require a restaurant, or even much fuel, to cook.

Chicken Ramen hit like a shockwave. And by the early 1960s, instant noodles weren’t a novelty anymore—they were a new category. Competitors poured in.

Toyo Suisan saw more than a trend. It saw an answer to a very practical problem. Its fish sausage business had a seasonality gap—production surged in summer, then slowed. Instant noodles, on the other hand, sold best when the weather turned cold and people wanted something hot and comforting. The two cycles fit together perfectly.

So in 1961, as Toyo Suisan broadened beyond seafood into a more diversified food company, it entered the instant noodle business with a clear goal: make higher-quality noodles than what was already on the market in Asia, and keep its factories working year-round.

The first attempt didn’t land. Toyo Suisan launched “Maruto instant noodles,” and it went nowhere—another forgettable product in a field that was getting crowded fast. But instead of walking away, Mori and his team treated the failure as data. They went back to improve flavors and rethink the brand itself.

That’s where the company made a deceptively powerful move: it renamed the product Maruchan.

“Maru” suggests roundness and completeness. “-chan” is an affectionate honorific—something you’d use for a child, a close friend, or something you feel warmly toward. Put together, Maruchan wasn’t just a label. It was a feeling: approachable, friendly, almost personal. Not a corporate food product, but something you’d gladly keep in the pantry.

In 1962, Maruchan Ramen took off.

By 1970, Toyo Suisan had become one of Japan’s most prominent food companies—an extraordinary shift in less than a decade from fish trading and processing into one of the country’s fastest-growing consumer categories.

But there was still one hard reality at home: Nissin remained the undisputed leader, and it wasn’t going to give that up. Toyo Suisan was learning, early and clearly, what would become a defining strategic principle.

If you wanted to beat Nissin head-on in Japan, you were signing up for a lifetime of fighting for second place.

So if Toyo Suisan was going to build true dominance, it would have to find a different battlefield.

IV. Fresh Noodles and Domestic Acceptance: The Japanese Playbook

Back in Japan, Toyo Suisan didn’t try to win the instant-noodle war by sheer force. Instead, it built a second engine—one that played perfectly to its original strengths.

While instant noodles grabbed the spotlight, Toyo Suisan quietly became a powerhouse in fresh noodles. This is a colder, harder business than shelf-stable ramen: shorter shelf lives, tighter production windows, and distribution that depends on refrigeration and logistics discipline. In other words, it rewarded exactly what Toyo Suisan had been building since its Tsukiji days.

In 1975, it introduced Sanshoku (“three pack”) Yakisoba, and it went on to become the top-selling fresh noodle product in Japan. With fresh noodles leading and instant noodles firmly in second, Toyo Suisan carved out something rare: a durable, defensible position at home, without having to dethrone Nissin head-on.

That same year, Toyo Suisan launched another set of products that would become cultural fixtures: Akai Kitsune Udon and Midori no Tanuki Ten Soba. Akai Kitsune—“Red Fox”—paired udon with sweet, deep-fried tofu. Midori no Tanuki—“Green Raccoon Dog”—delivered soba topped with tempura. Together, they became a long-running duo in Japanese households and advertising, the kind of brands you don’t just buy—you grow up with.

And Toyo Suisan didn’t treat Japan as one monolithic market. Akai Kitsune and Midori no Tanuki shipped in different flavor profiles depending on region. From the start, there were East and West Japan versions: the East leaned into a sharper soy sauce note, while the West pulled back and let the broth base lead. In the 2000s, Toyo Suisan pushed the localization even further—adding Japanese sardine broth to the West to create a Kansai version, and adding Rishiri kombu seaweed broth in the East to create a Hokkaido version.

It’s a subtle lesson, but a crucial one: noodles are intensely local. Toyo Suisan learned to treat taste like geography—something you adapt to, not something you standardize away.

Still, for all of Toyo Suisan’s domestic strength, Japan’s instant noodle market had a ceiling. Five companies accounted for virtually the entire category, with Nissin in the lead and Toyo Suisan holding a strong second. It was a mature, tightly held oligopoly—great business, but not a place where you casually take huge share.

So Toyo Suisan made the pragmatic call. Rather than fight endless battles for incremental gains at home, it would look for markets where the landscape was less settled—places where being second in Japan could translate into being first somewhere else.

And that decision is what takes us to the next chapter.

V. The American Dream: Building Maruchan Inc. (1972-1984)

In 1972, Toyo Suisan took the next logical step: it went overseas.

At first, the U.S. plan was cautious. Maruchan in America began as a marketing and distribution operation—importing ramen from Japan and trying to carve out shelf space. But importing only gets you so far. Costs rise, supply is fragile, and you’re always one bottleneck away from empty shelves.

So after five years as a distributor, Toyo Suisan committed to something much harder to unwind: local manufacturing. In 1977, it formed Maruchan, Incorporated and opened its first U.S. ramen plant in Irvine, California—an approximately 35,000-square-foot facility that became the foothold for everything that came next.

Southern California was a practical choice. There was a built-in base of early adopters, and the ports made it easier to bring in ingredients. But the bigger challenge wasn’t where the plant sat. It was who had already gotten there first.

Maruchan walked into a market where Nissin had the head start. Nissin Foods had been exporting instant ramen to the U.S. since 1970, and Top Ramen was already establishing the category. Maruchan struggled to secure distribution, bled money year after year, and at one point teetered on the edge. The company’s management was loose enough that Maruchan drifted toward a near-bankruptcy moment. It even tried to sell itself to Campbell Soup—only to be turned down.

That rejection forced a decision: fix it, or fold it.

Maruchan tried to restore the business on its own. It cut unnecessary costs, tightened up operations, and went hunting for sales channels. Most importantly, it stopped fighting the obvious battle. Instead of focusing only on the established coastal markets, it pushed hard into the West and the South—regions other companies weren’t prioritizing, where instant noodles were still more novelty than staple.

That move mattered. It opened doors to major retailers like Walmart and Costco, and by 1982 the business had swung back into the black.

Then came the moment that made Maruchan feel mainstream: the Olympics.

In 1984, the Los Angeles Olympics named Maruchan the official noodle food of the Games. The company signed a $3 million licensing pact, and suddenly millions of Americans were seeing, hearing, and talking about this strange new convenience food—what some called that “styrofoam thing,” the cup noodle format that still felt foreign to many shoppers.

The exposure worked. Maruchan’s brand awareness jumped, sales followed, and the business gathered enough momentum that by 1986 it had wiped out its accumulated deficit. The American experiment wasn’t just viable anymore. It was turning into Toyo Suisan’s most important growth story.

And the playbook that emerged here would repeat again and again: endure the ugly early years, be ruthless about cost, win where competitors aren’t looking, and then press hard when a once-in-a-decade marketing opening appears.

VI. The Mexican Peso Crisis: Fortune Favors the Bold (1994)

In 1994, Maruchan expanded into Mexico. On paper, the timing looked perfect. NAFTA had just been signed. Foreign investment was pouring in. Lots of consumer companies were planting flags and assuming the growth would be smooth.

Then the floor dropped out.

In December 1994, the Mexican government suddenly devalued the peso against the U.S. dollar. What followed became one of the first modern financial crises driven by capital flight: money rushed out, the currency spiraled, and the shockwaves rippled beyond Mexico into other emerging markets.

Inside Mexico, it got ugly fast. Inflation surged to around 52%. Imported inputs and dollar-denominated costs—ingredients bought abroad, equipment, debt payments—became brutally expensive overnight. Meanwhile, peso revenues were worth far less when converted back into dollars. For foreign companies, the math stopped working. Many pulled out.

Maruchan didn’t.

Part of what made that possible was positioning. Historically, Maruchan competed as the cheaper option, using less premium ingredients. In a crisis, that isn’t a weakness—it’s the business model. When consumers have to stretch every peso, they trade down from expensive proteins to affordable carbs. Instant noodles become a staple, not a treat. Maruchan was exactly what people could still buy.

So while competitors like Nissin exited Mexico, Maruchan stayed in the market—absorbing the pain in the short term to lock in the long term. It kept supplying stores, kept working its distribution, and kept showing up while others went dark. That decision turned out to be one of the most consequential in the company’s history.

Over time, as other foreign brands retreated and never fully returned, Maruchan captured a dominant position in Mexico’s instant noodle category—often described as over 80% share. By sales volume, Toyo Suisan’s share has been cited at roughly 76%.

This is the monopoly playbook in its simplest form: stay when others run.

Maruchan earned the kind of advantages you can’t buy later—habit, shelf space, distributor loyalty, and a reputation for being there when customers needed it most. In Mexico today, “Maruchan” is so closely associated with instant noodles that it’s effectively the category name in everyday life.

The payoff wasn’t just market share. Mexico also gave Toyo Suisan a natural geographic counterweight inside its overseas business—diversification created by commitment on the ground, not by financial engineering.

VII. The "Maruchan Shock" and Product Innovation (2010s)

By the time Maruchan was becoming a pantry staple across North America, Toyo Suisan still had a problem back home: Japan’s instant noodle market was mature, crowded, and hard to grow. Nissin was still the giant. Everyone else was fighting for share in a category that, for consumers, could feel interchangeable.

So Toyo Suisan did what it tends to do at its best. It changed the product.

In 2011, the company launched Maruchan Seimen (マルちゃん正麺), a packaged instant ramen designed to taste like “real” ramen shop noodles. It wasn’t just a flavor tweak or a new mascot. The core idea was structural: make noodles that felt fresh and restaurant-quality—sleek, smooth, and satisfying—without relying on the standard fried-noodle approach.

That required new process technology. Toyo Suisan developed and patented a method that let it dry raw noodles while keeping the taste and texture closer to freshly boiled ramen. The company described the goal plainly: to make you feel like you were sitting down in a ramen restaurant. It took four years to develop the technology and then scale it in factories.

The market rewarded the effort immediately. Maruchan Seimen became a top seller, and by 2015, cumulative sales had exceeded a billion servings.

In an industry that wasn’t supposed to have surprises left, this one hit hard enough that observers called it the “Maruchan Shock.” More importantly, it revived the fukuromen, or bag-noodle segment—proof that even in a commoditized category, consumers will pay up when the quality jump is obvious.

And the demand tailwinds weren’t limited to Japan. In the U.S., instant noodles were quietly moving from “something students eat” to “something lots of people keep around.” Per-capita consumption rose from 13.4 servings in 2018 to 14 in 2019, then climbed to 15.2 servings a year by 2023—suggesting that many Americans who rediscovered noodles didn’t drop the habit.

Attitudes shifted too. The share of American adults who said they’d consider putting Maruchan in their cart rose from 16.9% in 2019 to 21.9% in 2024, roughly a 30% jump.

Taken together, it pointed to a structural change. Ramen was becoming a mainstream comfort food, helped along by the broader “ramen boom” of restaurant culture, the premiumization of instant options, and a basic economic reality: when inflation bites, inexpensive, filling meals get a lot more attractive.

VIII. COVID-19 Pandemic: The Great Acceleration (2020-2022)

The pandemic didn’t create instant-noodle demand out of thin air. It hit the fast-forward button on trends that were already building.

When lockdowns swept in during March 2020, shoppers did what they always do in a crisis: they stocked up on food that was cheap, shelf-stable, and reliably satisfying. Instant noodles checked every box. They vanished from shelves because they were one of the few meals you could buy in bulk, store for months, and still feel like you were eating something warm and comforting.

And it didn’t fade when the initial panic passed. A lot of people who bought ramen “just in case” ended up buying it again because they remembered the core truth of the category: it’s fast, it’s filling, and it’s hard to beat on value. Mintel later found that roughly one in four U.S. consumers, and three in ten Canadians, eats instant noodles. Euromonitor pegged the U.S. instant-noodles market at $2.7 billion in 2023, after growing 36% over the prior five years.

For Maruchan, the pandemic also highlighted something less visible, but far more decisive than advertising: manufacturing geography.

While some competitors leaned heavily on overseas production and got slammed by frustrated ports, container shortages, and unpredictable shipping schedules, Maruchan had a different profile. Its U.S. factories—in Irvine, California; Richmond, Virginia; and Texas—kept running through the chaos. With plants operating around the clock and hundreds of employees keeping lines moving, Maruchan could supply retailers when others couldn’t.

That scale is hard to overstate. Maruchan produces more than 3.6 billion packages of ramen noodle soup a year—nearly 10 million a day. You don’t spin that up in a hurry, even if you’re a global food company. You need the factories, the relationships, the distribution, and the muscle memory.

The brand strength piled on top of that operational advantage. Maruchan Ramen Noodle Soup leads U.S. consumer awareness at 68.9% among adults. And when asked what they’d consider buying next, far more people picked Maruchan than its nearest rival: 21.9% versus 11.3% for Nissin Cup Noodles.

The result was a larger, stickier market. The pandemic pulled new buyers into the category, and many of them stayed. What began as pantry insurance turned into a habit—and for Toyo Suisan, it was another step in turning instant noodles from a niche staple into a mainstream one.

IX. The Modern Business: A Conglomerate Analysis

Today, Toyo Suisan Kaisha, Ltd., together with its subsidiaries, produces and sells food products in Japan and around the world. It now operates across a spread of segments: Seafood, Overseas Instant Noodles, Domestic Instant Noodles, Frozen and Refrigerated Foods, Processed Foods, and Cold-Storage.

On paper, that’s the natural end state of a company that grew up at Tsukiji: start with fish, build infrastructure, add processing, then layer on consumer brands. But when you look at where the business actually gets its revenue, the plot is much less “diversified” than it sounds.

By FY24, the center of gravity was clear. Overseas Instant Noodles was the biggest piece of the pie, accounting for 45.3% of total revenue. Domestic Instant Noodles contributed 20.5%. Frozen and Refrigerated Foods added 11.6%. Meanwhile, the legacy roots—Seafood at 6.0%, Cold Storage at 4.9%, and Processed Foods at 4.1%—were still meaningful, but no longer the main character.

In the U.S., Toyo Suisan’s Maruchan footprint is built around three wholly owned operating companies: Maruchan, Inc. in Irvine, California; Maruchan Virginia, Inc. in Richmond, Virginia; and Maruchan Texas, Inc. in Von Ormy, Texas. It also operates a joint venture with Ajinomoto Foods North America in Portland, Oregon, called Ajinomoto Toyo Frozen Noodles.

Those U.S. plants aren’t just “capacity.” They’re a strategic map. California anchors the West. Virginia covers the East. Texas splits the difference and strengthens the South. Together, they lower logistics costs, reduce dependence on any single facility, and make it easier to keep shelves stocked as demand grows.

And Toyo Suisan hasn’t limited its overseas ambition to North America. In 2014, it partnered with Ajinomoto to form Maruchan Ajinomoto India Private Limited, aiming at India with products tailored to local tastes. It’s a very different battlefield—India’s instant noodle market has long been dominated by Nestlé’s Maggi—but it’s also one of the few places left with truly massive headroom.

Step back, and the geographic mix tells you what Toyo Suisan has become. Nearly half of its revenue now comes from the Americas, while Japan contributes far less than you might expect for a company founded in Tokyo’s fish market.

It’s a quiet inversion, and it matters: more of Toyo Suisan’s trajectory is now shaped by what happens in places like Texas than what happens in Tokyo.

X. Activist Pressure and The Corporate Governance Awakening (2024)

In April 2024, Toyo Suisan found itself in unfamiliar territory: not fighting for shelf space, but facing pressure from activist investors.

A group led by Nihon Global Growth Partners Management Inc. announced it had submitted four shareholder proposals for Toyo Suisan’s 2024 General Shareholders’ Meeting. NHGGP and the investor group collectively owned about 3.8% of the company’s common shares—small in absolute terms, but large enough to be taken seriously in Japan’s corporate ecosystem.

NHGGP’s Managing Director, Brian Doyle, framed the argument in a way that would resonate with anyone who had just listened to Toyo Suisan’s overseas story:

“Toyo Suisan excels in its core operating businesses and possesses crown jewel assets, most notably its North American instant noodle and Japanese refrigerated warehouse segments. As long-term investors with decades of experience in the Japanese market, we believe in the Company's significant potential. However, in our view, it must catch up to its peers in terms of capital allocation, shareholder returns and strategic focus.”

The heart of the campaign was a valuation gap. NHGGP argued that if Toyo Suisan took the “appropriate steps,” its market value could move closer to an intrinsic value they estimated at at least JPY17,300 per share—versus a trading price of JPY9,281 per share as of April 24, 2024.

Their critique was blunt: despite world-class positioning in instant noodles across the U.S., Mexico, and Japan, the company still looked “deeply discounted.” Nihon Global attributed that to three core issues: a lack of strategic focus on the best assets, capital allocation that poured too much capex into low-ROA legacy businesses and left the company overcapitalized, and too little emphasis on total shareholder return.

The proposals themselves were straightforward and very “global markets” in flavor. Raise the dividend payout ratio to 40%, bringing it more in line with peers. And authorize a JPY20 billion share buyback—especially striking because Toyo Suisan had not executed any meaningful buybacks in the prior 17 years.

Seventeen years is a long time. In the U.S., buybacks are practically a reflex. In Japan, historically, they were closer to a taboo—many companies prioritized stability, employment, and stakeholder balance over aggressive shareholder returns. NHGGP was betting that this cultural default was finally changing.

The shareholder meeting suggested they weren’t wrong. NHGGP’s proposal requiring Toyo Suisan to disclose its cost of capital received 49% support. NHGGP said it believed this was the highest approval percentage ever in Japan for a shareholder proposal focused on cost-of-capital disclosure. And because more than 10% of Toyo Suisan’s shares were held by cross-shareholders and related parties, NHGGP argued the measure likely won support from a majority of “unaffiliated” shareholders.

Then came the bigger signal: Toyo Suisan moved.

On June 4, 2024, the company announced a JPY25 billion share buyback—its first in 17 years, and larger than the JPY20 billion buyback NHGGP had proposed. NHGGP said it believed the buyback was a direct response to the proposal, and to the strength and breadth of shareholder support.

For Toyo Suisan, it was a watershed moment: the company didn’t just absorb the criticism. It acted, and it acted decisively.

The pressure didn’t stop there. In February 2025, Doyle returned to the theme:

“As long-term investors in Japan and in Toyo Suisan, we are convinced that the Company has enviable opportunities that it can capitalize on to drive increased value. Unfortunately, the market has continued to undervalue Toyo Suisan and we believe this is due to historic capital allocation and shareholder return policies that are inconsistent with market norms.”

“We applaud the Company for taking initial steps in response to the intent expressed by shareholders – including by executing its first share buyback in 17 years – and we urge leadership to continue to do so.”

And that’s the new chapter of the Toyo Suisan story: not just how it built an empire, but whether it will modernize how it runs one.

XI. Recent Performance and Financial Trajectory

If the activist critique was “the market isn’t giving Toyo Suisan credit,” the operating results have been making the opposite case: this is a business that’s been putting up real momentum.

For the nine months ended December 31, 2024, Toyo Suisan reported net sales up 10.3% year over year, while operating profit jumped 29.8%. In other words: not just growth, but growth with leverage.

That showed up clearly in the quarterly numbers too. In 1Q 2024, operating income came in at 20.27 billion yen, up 54% year over year and ahead of estimates. Net income was 17.63 billion yen, up 60% and also above expectations.

Zooming out to the full fiscal year ended March 31, 2025, Toyo Suisan reported sales of 507.60 billion yen, up 3.8% from the prior year. Operating income rose faster—up 13.2% to 75.49 billion yen—and net income increased 13.0% to 62.87 billion yen. The company also forecast continued growth, guiding to 545 billion yen in sales for the fiscal year ending March 2026, a 7.4% increase.

The clearest story inside those totals is the one we’ve been following all along: Overseas Instant Noodles. Segment sales grew 18.4% year over year, and profit rose even faster—up 41.8%—helped by lower raw material costs and strong demand in the U.S. and Mexico. Domestic Instant Noodles grew more modestly, but still moved in the right direction: 3.5% sales growth and an 8.2% increase in profit. Frozen and Refrigerated Foods also contributed, with sales up 5.6% and profit up 10.7%.

Stack it up against peers and the outperformance becomes even more obvious. Toyo Suisan delivered a revenue CAGR of 16.3%, versus 13.4% for Nissin and 6.3% for Nichirei. More striking: Toyo Suisan’s EBIT growth compounded at 49.6% over the past two years, compared with 18.2% for Nissin and 8.4% for Nichirei. That profit surge drove a 540-basis-point expansion in operating margin, from 8.2% to 13.6%.

It’s a reminder of what dominance looks like when the category is still expanding: if you own the shelf, you get the volume—and once scale and costs break your way, you don’t just grow. You widen the gap.

XII. Sustainability and Future Initiatives

With Maruchan now firmly embedded in everyday life across North America, Toyo Suisan has had to face a very modern question: what does it mean to sell convenience at massive scale, without leaving a massive footprint behind?

One place that gets visible fast is packaging. Toyo Suisan has been working to reduce plastic use, especially for the vertical cup-type instant noodles sold in Mexico and Latin America. The company has been converting those containers from expanded polystyrene to paper-based materials. By December 2024, it had reached a 50% paper-cup conversion rate, with a stated goal to complete the transition by the end of 2026.

That packaging shift sits inside a broader set of sourcing and materials initiatives. Toyo Suisan has emphasized using sustainable materials with environmental, social, and human-rights considerations in mind—things like sourcing sustainable palm oil, working with seafood certified under sustainable fisheries and aquaculture standards (MSC/ASC), procuring paper materials that support forest conservation, and using more environmentally friendly inks.

The company hasn’t slowed down on product, either. In August 2024, Maruchan expanded its Yakisoba line with two new flavors: orange chicken and chili cheese. The Orange Chicken Flavor Yakisoba uses traditional ramen-style noodles and comes with separate packets of vegetables and sauce powder—another reminder that even a value staple still needs novelty to keep consumers curious.

And Toyo Suisan is preparing for demand that looks less like a temporary spike and more like a new baseline. To meet growing North American consumption, the company has planned a 20% capacity increase at its California plant—an investment that signals it expects the market to keep expanding, and that it intends to stay out in front.

XIII. Playbook: Business and Strategic Lessons

The Second-Mover Advantage

Toyo Suisan didn’t invent instant noodles. Nissin did. But Toyo Suisan figured out where the pioneer hadn’t yet locked things down—and built dominance there. In Japan, it made peace with being the strong number two. In the U.S. and Mexico, it played for keeps and became number one. The lesson is simple: sometimes you let someone else pay to educate the market, then you win by executing better.

Stay When Others Leave

Mexico in 1994 is the cleanest example of contrarian conviction. The peso crisis made the economics ugly, fast—and plenty of competitors chose to leave. Maruchan stayed. It took the short-term pain, kept supplying, and kept building distribution while others went dark. Over time, that decision turned into a moat that’s been extraordinarily hard to crack, and it helped Maruchan build a share of well over three-quarters of the market.

Local Manufacturing as Moat

Maruchan’s factories in California, Virginia, and Texas are more than “capacity.” They’re an advantage you feel most when things go wrong. Local production lowers landed costs, shortens replenishment cycles, and makes the business less dependent on imports. During the pandemic, when supply chains snapped and shelves emptied, that footprint mattered. Manufacturing moats are expensive to build—but once they’re there, they’re difficult to copy.

Brand Simplicity

“Maruchan” is disarmingly friendly for a product that often competes on price. That warmth is a quiet differentiator in a category where the functional promise—cheap, fast, filling—looks similar across brands. The name also travels well. In English-speaking markets, it doesn’t over-explain or over-position; it’s memorable precisely because it feels simple and confident.

The Conglomerate Penalty

Toyo Suisan still carries its roots: seafood, cold storage, and other legacy businesses alongside the noodle empire. Those pieces may create real operational synergies, but they also muddy the story for investors—and, critics argue, soak up capital that could earn higher returns elsewhere. In the activist framing, this complexity helps explain why the stock has traded at what they call a discount to intrinsic value.

Japanese Corporate Governance Gap

For years, Toyo Suisan behaved like a classic Japan-era incumbent: cautious about returning capital, including going 17 years without meaningful buybacks before 2024. For investors, that conservatism cuts both ways. The risk is that value stays trapped, even as the underlying businesses perform. The opportunity is that even incremental governance changes—clearer focus, better capital allocation, more consistent shareholder returns—could meaningfully narrow the gap between what the company earns and what the market is willing to pay for it.

XIV. Competitive Landscape and Five Forces Analysis

Threat of New Entrants: LOW-MEDIUM

Instant noodles look simple. In reality, entering the category at real scale is a grind: you need major capital for factories, the logistics and relationships to get on shelves nationwide, and the marketing muscle to make consumers reach for your box instead of the incumbent.

Still, the door isn’t locked—especially for companies that already live inside America’s biggest retailers. General Mills announced it was launching its first ramen products under two existing brands, Old El Paso and Totino’s. The Old El Paso line is set to come in two flavors, Fajita and Beef Birria, with a debut at Walmart in April.

The timing makes sense. Demand for this kind of low-cost comfort food keeps rising, driven by convenience and constant new flavors. The global ramen noodles market was valued at $58 billion in 2023 and is forecast to reach $94 billion by 2033.

General Mills’ move is the reminder: a deep-pocketed CPG giant can “enter” noodles without building a brand from scratch. But matching Maruchan’s manufacturing footprint and distribution depth—the parts that actually keep shelves full—remains a much steeper climb.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers: LOW

The core inputs are commodities: wheat flour, palm oil, and seasoning ingredients that trade globally. No single supplier holds enough power to dictate terms. And Toyo Suisan’s sheer purchasing scale gives it leverage that smaller players simply don’t have.

Bargaining Power of Buyers: MODERATE

In packaged food, retailers are king. Companies like Walmart can pressure pricing, dictate promotions, and decide who gets the best shelf space.

But brands with real pull get a seat at the table. Maruchan’s awareness—nearly 69% among U.S. adults—creates consumer demand that retailers don’t want to disappoint. Private label is always present, but it hasn’t meaningfully broken the branded leaders in a category where shoppers tend to stick with what they know.

Threat of Substitutes: LOW

If you zoom out to “cheap, fast meals,” yes—there are substitutes: frozen dinners, canned soup, even value fast food. But instant noodles win on a specific combination that’s hard to beat: calories per dollar, shelf stability, and speed. Very few alternatives match all three at once.

Competitive Rivalry: MODERATE

Noodles are a bigger battlefield than they appear. In the U.S., Toyo Suisan and Nissin have long fought for category leadership, with South Korea’s Nongshim sitting between them—first and third place split by a premium, spicy challenger.

Korean competitors like Nongshim and Samyang have made gains, particularly at the higher end of the market where heat, texture, and “restaurant-style” cues matter. But Maruchan’s control of the value segment—the largest part of the market—has largely held.

Hamilton Helmer's 7 Powers Framework

Toyo Suisan shows several of Helmer’s durable advantages:

Scale Economies: With about 3.6 billion packages produced annually, the unit-cost advantage is structural—and extremely hard to copy without massive investment and time.

Counter-Positioning: Maruchan’s value-first strategy makes it awkward for a rival like Nissin to chase it aggressively without undermining its own positioning.

Switching Costs: Low for consumers, but higher for retailers in practice—pulling back Maruchan shelf space risks empty-handed shoppers and disrupted category performance.

Network Effects: Limited here.

Process Power: The patented Maruchan Seimen process shows real proprietary know-how, even if it’s most relevant to the Japanese domestic portfolio.

Branding: High awareness and a deep emotional imprint—especially among consumers who grew up with it as the default “ramen at home.”

Cornered Resource: Decades of accumulated manufacturing capacity and distribution relationships—a quietly powerful advantage that can’t be recreated on a quarterly timeline.

XV. Key Performance Indicators for Investors

KPI #1: Overseas Instant Noodles Segment Operating Margin

If you want the fastest read on how healthy Toyo Suisan’s engine really is, start here. The Overseas Instant Noodles segment—driven mainly by North America—is where the profit growth lives. Its operating margin tells you, in one number, whether Maruchan is holding pricing, managing input costs, and fending off competition. Historically it’s been in the mid-teens, with a recent push higher that signals strengthening economics, not just higher volumes.

KPI #2: Volume Growth in the U.S. and Mexico

When you already own the category, growth gets more interesting. In the U.S. and Mexico, Maruchan is so dominant that rising volumes can only come from two places: the overall market getting bigger, or Maruchan taking even more of it. Tracking volume trends here is a reality check on whether instant noodles are still expanding as a habit—and whether Maruchan is capturing growth in line with the category, or pulling ahead.

KPI #3: Shareholder Returns (Dividends + Buybacks) as Percentage of Free Cash Flow

This is the governance tell. For decades, Toyo Suisan returned relatively little capital, and activists have made that the centerpiece of their critique. So the cleanest way to measure whether the company is truly changing is to watch what portion of free cash flow comes back to shareholders through dividends and buybacks. If that ratio rises—and stays up—it’s evidence that the “crown jewel assets” aren’t just compounding operationally, but that the company is also evolving toward shareholder-friendly capital allocation.

XVI. Bull Case vs. Bear Case

Bull Case

Toyo Suisan sits behind the dominant brand in a consumer category that tends to hold up when times get tough. When budgets tighten, people don’t stop eating—they trade down. And few products win that trade-down moment like instant noodles. Maruchan has spent decades building the kind of manufacturing scale, distribution reach, and retailer relationships that are hard to replicate quickly, even for large competitors.

There’s also a clear catalyst in motion: governance. Activist pressure has already forced action. The company’s first share buyback in 17 years didn’t just happen—it came in above the size activists asked for. If Toyo Suisan continues modernizing capital allocation and shareholder returns, the market may start valuing those “crown jewel” assets more like a focused, high-quality global food business, and less like a sprawling conglomerate.

Meanwhile, the category itself has been expanding in ways that look more structural than temporary. U.S. per-capita consumption climbed from 13.4 servings in 2018 to 15.2 in 2023. And the share of American adults who say they would consider buying Maruchan rose about 30% over five years. Those trends suggest instant noodles are moving from niche staple to default pantry item—exactly the kind of shift that can compound for a long time when you already own the shelf.

Bear Case

Maruchan’s strength is also its constraint: its dominance is concentrated in the value end of the market. That segment is sensitive to cost inflation. If key inputs rise and price-sensitive consumers resist increases, margins can get squeezed—and unlike premium brands, value leaders often have less room to “price through” without risking volume.

At the same time, competitive pressure is creeping in from both ends. Korean brands have been gaining share in premium instant noodles, where consumers pay for spice, texture, and restaurant-style cues. If premium growth becomes the main driver of the category, Maruchan could find itself defending a mature, lower-margin core while rivals capture the profitable upside.

And now the big U.S. CPG companies are paying attention. General Mills’ entry is a signal that instant noodles have become attractive enough for incumbents with deep pockets and existing retail leverage. Maruchan’s scale advantage is real, but well-capitalized entrants can still make life harder—especially in the higher-margin flavored and premium lanes.

Finally, the corporate structure remains a lingering weight. Seafood, cold storage, and other legacy operations still absorb capital that could potentially earn higher returns elsewhere. If Toyo Suisan doesn’t meaningfully sharpen focus—or if it continues investing heavily in lower-return businesses—the valuation discount activists complain about may not go away.

Even with Japan’s governance environment improving, it still isn’t the same as Western markets. Cross-shareholdings and relationship-based ownership can mute the urgency around shareholder returns, and that may leave Toyo Suisan trading below what many investors would consider intrinsic value for a very long time.

XVII. Conclusion: The Quiet Empire Continues

Toyo Suisan Kaisha is one of the more improbable corporate transformations of the past century. It began as a frozen tuna trader working the stalls of Tsukiji Market. It ended up as the dominant force in North American instant noodles. And it got there the unglamorous way: by being patient, thinking contrarian when it mattered, and executing relentlessly on the operational details that most people never see.

The arc of the story also runs against a lot of standard business-school instincts. Toyo Suisan didn’t “win” by conquering its home market. It made peace with being number two in Japan, then went hunting for places where the battlefield was still open. It didn’t retreat when the economics got ugly. In Mexico, it stayed through the peso crisis while competitors pulled out—and it turned survival into a moat. And it didn’t try to outsource its way to scale. It built factories, distribution, and the kind of supply resilience that only looks obvious after it saves you.

Now the company sits at a different kind of turning point. Activist pressure has pushed Toyo Suisan to start modernizing its approach to capital allocation. The operating business is delivering some of the strongest performance in its history. And the world, for all its volatility, continues to reward what Maruchan sells: fast, filling, affordable comfort.

And yet, despite “crown jewel” assets and real momentum, Toyo Suisan has traded at what activists and many investors argue is a meaningful discount to intrinsic value—dragged down by legacy businesses, conservative policies, and the familiar conglomerate complexity.

For long-term investors, that’s the tension—and the opportunity. You have a category leader in a product people keep buying when times get tough, throwing off cash and widening its advantages with scale. If governance keeps evolving, there’s a plausible path to the market valuing Toyo Suisan less like a cautious Japanese conglomerate and more like the global consumer powerhouse its noodle business already is. The risks are real—competition, input costs, and the possibility that the discount persists—but the core franchise is unusually durable.

What hasn’t changed in seven decades is the simple insight that built the company in the first place: when you can feed people cheaply, reliably, and at scale, you can build something that lasts.

So the next time you see a college student tearing open a packet of Maruchan at 2 AM, it’s worth remembering what’s really sitting behind that humble meal: a quiet empire, built factory by factory and shelf by shelf, that still doesn’t get much attention—yet keeps winning anyway.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music