Kioxia Holdings: The Invention That Toshiba Almost Forgot

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

NAND flash is one of those inventions that’s so embedded in modern life you never think to ask where it came from. It’s in every phone. Every laptop. Every data center that’s currently gulping down electricity to train and run AI models. And it all traces back to one Japanese engineer at Toshiba—working nights and weekends on a “semisecret” project—pushing on an idea his employer initially wanted him to drop.

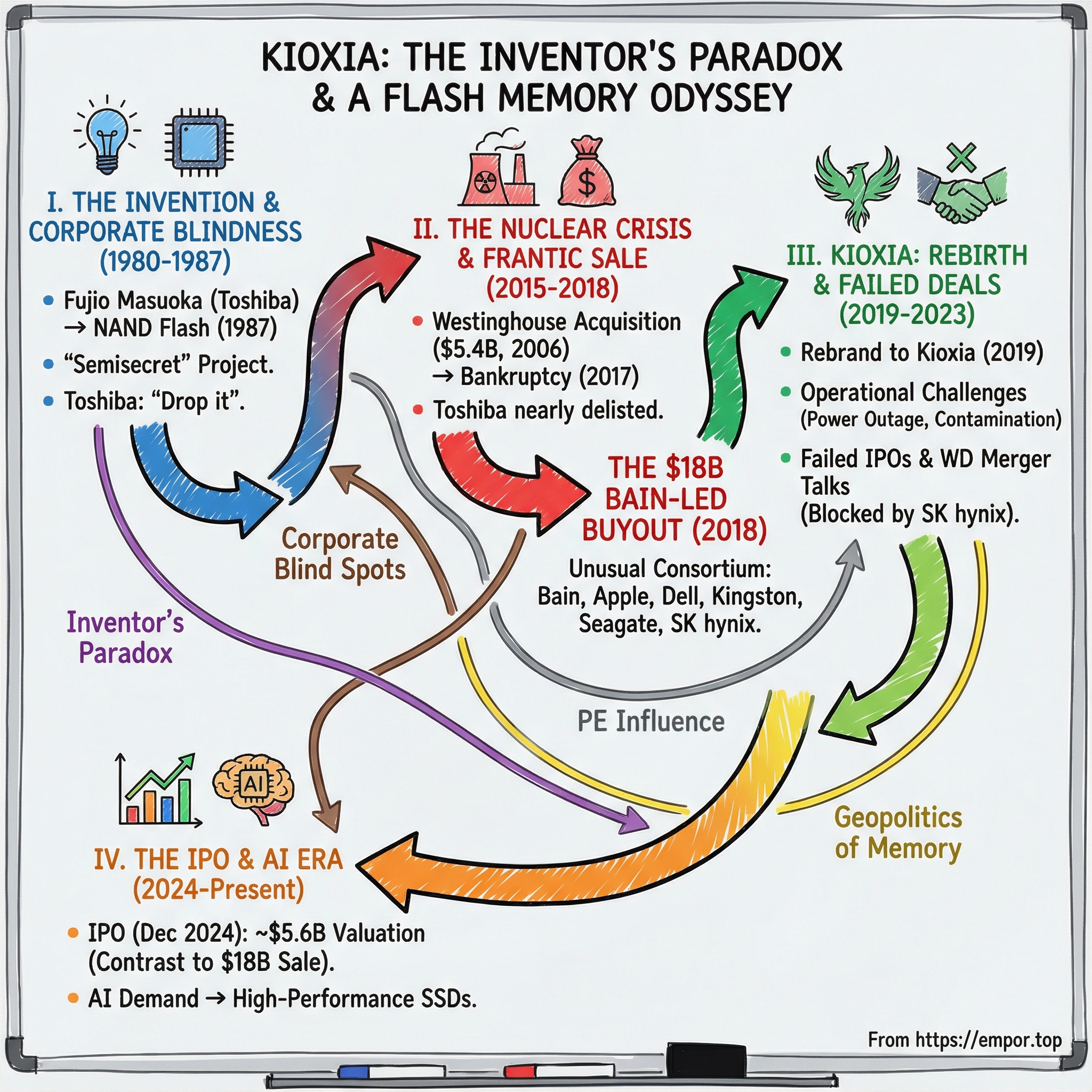

Here’s the twist: the company that would eventually become Kioxia didn’t just participate in the flash revolution. It started it. And yet, in December 2024, when Kioxia finally listed on the Tokyo Stock Exchange, it did so at 1,455 yen a share—putting the whole company at roughly $5.5 billion. That’s a stunning comedown from 2018, when Toshiba sold a majority stake in its memory business at a valuation around 2 trillion yen, or about $18 billion.

That gap is the central tension of this story—the inventor’s paradox in corporate form. How does the birthplace of a foundational technology end up worth a fraction of what it once was? Especially after an $18 billion, Bain-led buyout that included an unusual mix of stakeholders and strategic interests—Bain, major industry players, and even rival memory-maker SK hynix.

Along the way, we’re going to pull on four threads that explain how this happened.

First, the inventor’s paradox itself: how world-changing breakthroughs don’t always reward the people—or the companies—that create them.

Second, corporate blind spots: the pattern, especially in Japanese conglomerates, where revolutionary ideas can be treated like distractions while incremental improvements get all the oxygen.

Third, private equity’s growing influence in Japanese tech: what it looks like when foreign capital and global deal logic collide with a legacy industrial champion under stress.

And fourth, the geopolitics of memory: because NAND isn’t just a product category anymore. In an AI world, it’s infrastructure—and infrastructure becomes strategy.

This matters now because AI is changing what “memory” means. The demand surge isn’t just about more storage; it’s about faster, higher-performance, high-capacity SSDs to feed inference systems and keep data centers running hot. The industry is also still searching for stability. Consolidation keeps getting floated as the solution—most famously in the on-again, off-again merger talks between Kioxia and Western Digital—yet nothing has fully resolved the underlying volatility.

And Kioxia, after years of delays, finally stepped back into the public markets. On its debut, the stock dipped at the open, then rallied hard, finishing the day up about 17% at 1,689 yen—valuing the company at roughly 863 billion yen, or about $5.6 billion. A good day. Still, compared to the $18 billion price tag paid in 2018, it’s a reminder of just how much ground has been lost.

So what happened in between?

How did the company tied to one of the most important inventions of the digital age end up looking less like a victory lap and more like a case study? And as AI turns memory from a commodity into a strategic asset, what does the next chapter look like—especially for a company that, in many ways, started the whole thing?

II. The Invention: Fujio Masuoka and the Birth of Flash Memory (1980-1987)

The Unsung Hero

Fujio Masuoka, born May 8, 1943, is a Japanese engineer whose career spanned Toshiba and later Tohoku University. He’s best known for inventing flash memory—and for developing both of its foundational branches in the 1980s: NOR flash and NAND flash.

To understand how unlikely that is, picture Toshiba’s semiconductor division in 1980. It was a classic hierarchical Japanese organization: engineers executed the plan, respected the chain of command, and optimized what already existed. Breakthroughs weren’t supposed to come from someone deciding, on their own, that the plan was wrong.

Masuoka did exactly that. In 1980, he recruited four engineers into a semisecret effort to design a memory chip that could store a lot of data and still be affordable. And the real work—the work that mattered—didn’t happen in the daylight. Masuoka had been fixated on one of the semiconductor industry’s hardest problems coming out of the 1970s: nonvolatile memory that kept data even when the power was off. He started pursuing his solution at night and on weekends, without asking Toshiba for permission.

That detail isn’t just color. It’s the entire story. In that era, inside a company like Toshiba, doing serious technical work “off the books” wasn’t scrappy. It was insubordination.

Masuoka’s background set him up for this kind of contrarian leap. He studied engineering at Tohoku University in Sendai, earning his undergraduate degree in 1966 and his doctorate in 1971, then joined Toshiba that same year. There, he invented stacked-gate avalanche-injection metal–oxide–semiconductor (SAMOS) memory, a precursor to EEPROM and ultimately flash memory.

His obsession was simple: make nonvolatile memory practical. EEPROM existed, but erasing it was painfully slow. Masuoka developed “floating gate” technology that could be erased far faster—bringing nonvolatile storage out of the lab and closer to something you could actually build products around.

The Technical Breakthrough

The genius of Masuoka’s breakthrough only makes sense when you see what storage looked like then. You had fast memory that forgot everything when the power died, and persistent storage that relied on moving parts and compromises. EEPROM was a promising middle ground—electronic, rewritable, and nonvolatile—but it was expensive, complex, and not suited for cheap, dense storage.

Masuoka’s team attacked the core cost problem. They created a variation of EEPROM with a memory cell built around a single transistor. Conventional EEPROM designs required two transistors per cell. That sounds like a small tweak. It wasn’t.

That one-transistor cell was the unlock. Cut the components per bit, and suddenly density and cost start moving in the right direction. It didn’t just make a better EEPROM. It created a runway for storage to scale—generation after generation—into something that could plausibly live inside consumer devices.

The name came from a moment of metaphor. Masuoka’s colleague Shoji Ariizumi suggested “flash,” because the erase process reminded him of a camera flash. The word stuck, and the category stuck with it.

Early results—at a capacity of only 8,192 bytes—were published in 1984. That same year, Masuoka and his colleagues presented NOR flash. Then, in 1987, they presented NAND flash at the IEEE International Electron Devices Meeting (IEDM) in San Francisco. Toshiba commercially launched NAND flash memory in 1987.

Corporate Blindness: Japan's Classic Mistake

If you’re imagining Toshiba immediately recognizing what it had and racing it into the world, that’s not how this went. Masuoka’s bosses told him to drop it—to erase the idea. He didn’t.

And here’s the thing about presenting at a major conference like IEDM: once you put the work into the global technical record, it can’t be quietly buried inside a corporate org chart. In 1984, Masuoka took the invention to San Francisco and put it in front of the people most likely to understand what it meant.

They understood. Major American semiconductor companies saw the implications right away and requested samples. Intel, in particular, moved with urgency—assigning more than 300 engineers to push flash memory forward. Toshiba, meanwhile, gave Masuoka minimal resources.

That gap—between the company that invented flash and the company that decided it mattered—defined the next chapter. Intel turned flash into a major business. Toshiba, the birthplace of the technology, had to be dragged toward its own invention. Intel’s 1988 introduction of a 256-kilobit chip, used across vehicles, computers, and other mass-market products, helped force Toshiba to finally greenlight the work internally.

Masuoka, the inventor, didn’t get inventor treatment. Toshiba gave him only a few hundred dollars as a bonus and later tried to demote him. Intel went on to generate billions in related sales. And in one of the strangest footnotes in tech history, Toshiba’s press department told Forbes that it was Intel that invented flash memory.

For Masuoka, that wasn’t just insulting—it was clarifying. He left Toshiba and became a professor at Tohoku University. And in a culture where lifetime loyalty to one’s company was almost a civic duty, he sued Toshiba for compensation. The case settled in 2006 for a one-time payment of ¥87 million (about $758,000).

For the rest of this story, Masuoka’s arc is the warning label. Invention is not the same thing as capture. Toshiba had flash memory first. What it didn’t have—at the moment it mattered—was the organizational will to bet on it, back it, and claim it as its own.

III. The Rise of Flash: From Digital Cameras to Data Centers (1990s-2000s)

Finding Product-Market Fit

The 1990s were a reality check for every company that thought memory was a comfortable business. DRAM, the workhorse of computing, was a knife fight: vicious price cycles, constant oversupply, and a steady stream of casualties. Toshiba was in the arena like everyone else.

Then the dot-com bubble burst. Demand collapsed. And by 2001, Toshiba made a defining call: it withdrew from manufacturing and selling commodity DRAM. Not because it suddenly had an epiphany about the future, but because the economics made continuing indefensible—especially up against better-capitalized Korean rivals like Samsung.

In hindsight, this is the moment the company finally turned toward its own invention. With DRAM no longer a viable hill to die on, Toshiba leaned into NAND flash—the technology Masuoka had dragged into existence years earlier. Sometimes “strategy” is just what’s left after the alternatives stop working.

And the timing couldn’t have been better. In the early 2000s, the world found its first mass-market reason to buy flash: digital cameras. Before the iPhone. Before cloud. Before SSDs were mainstream. People wanted to take photos without film, and they needed non-volatile storage to keep them. The memory card market took off, and NAND went from intriguing to essential.

To keep up, Toshiba pushed hard on scaling: smaller memory cells, better circuits, better processes, higher capacity. What had once been a neglected lab success was turning into a manufacturing race.

The SanDisk Partnership: A Fateful Alliance

Even with demand exploding, NAND had a problem: building capacity costs a fortune. So Toshiba did what this industry often does when the stakes get too big for one balance sheet—it partnered.

In May 2000, Toshiba and SanDisk signed an agreement to create a new semiconductor company, FlashVision LLC, to produce advanced flash memory using fabrication space at Dominion Semiconductor in Manassas, Virginia.

The pitch was straightforward: a joint venture to produce 1-gigabit flash memory chips, with the companies expecting the business to ramp quickly—potentially to $1 billion in sales by 2002.

But this wasn’t just a manufacturing arrangement. It became a structural feature of the entire business. The model was simple and powerful: share fabs, share economics, compete on products. When fab construction runs into the billions, that’s a compelling compromise. It also creates entanglements that are easy to sign and hard to unwind.

The FlashVision site itself reflected how turbulent the memory market already was. The plant had previously been jointly owned by Toshiba and IBM, but IBM exited as it pulled back from DRAM. Into that opening stepped SanDisk, led by flash pioneer Eli Harari, bringing complementary strengths in areas like multi-level cell technology and controller design.

Over time, the partnership deepened. And in 2016, when Western Digital acquired SanDisk for $19 billion, it didn’t just buy a flash business—it inherited this joint venture relationship. That inheritance would matter later, when Toshiba’s broader crisis forced it to sell the memory unit and Western Digital tried to block any deal that didn’t run through them.

What looked like a smart, pragmatic alliance in 2000 would eventually become both a competitive advantage and a strategic constraint.

The 3D Revolution

By the mid-2000s, the NAND playbook that had powered the digital camera boom started to break. For years, the industry’s trick had been simple: shrink the cells, pack more onto the chip, cut the cost per bit. But flash isn’t magic. At some point the cells get so small that the electrons representing data become unreliable. The physics starts pushing back.

Kioxia’s answer was to change the geometry.

In 2007, it announced the world’s first 3D flash memory technology: BiCS FLASH. The idea was as intuitive as it was transformative. If you can’t keep spreading out on a single plane, start building upward. Instead of laying memory cells across the surface like a suburb, stack them vertically like a high-rise.

BiCS took that concept further with a manufacturing approach designed to keep costs down: rather than forming memory cells one layer at a time, it stacked plate-shaped electrodes first, then drilled through them and connected the structure so memory cells could be formed across all layers at once. That “batch processing” concept was presented at an academic conference in 2007, and it became the blueprint for commercialization.

The product roadmap shows how quickly this became the new scaling engine: BiCS products arrived with 48 layers in 2015, then moved to 96 layers in 2018, 112 layers in 2020, and 162 layers in 2022. The race shifted from “who can shrink fastest” to “who can stack the most—reliably, cheaply, and at scale.”

This also reframed what NAND competition looked like. Pricing still behaved like a commodity, but the technology didn’t stand still. Architectures mattered. Execution mattered. And layer counts became a public scoreboard, with rivals pushing the frontier too—like SK hynix commercializing 321-layer TLC and Samsung driving toward 400-plus-layer V-NAND, both signaling that the industry expects to scale well beyond 500 layers before the decade ends.

Kioxia’s BiCS—now in its eighth generation, with 218-layer BiCS FLASH delivering a 2Tb device using advanced scaling and wafer bonding—remained a centerpiece of its competitiveness. And as AI servers and data centers pulled harder on storage, the story of flash stopped being about consumer gadgets and started looking a lot more like infrastructure.

IV. The Nuclear Disaster: Westinghouse and Toshiba's Crisis (2015-2018)

The Seeds of Catastrophe

By early 2017, Toshiba was teetering on the edge of oblivion. Not because its core technology businesses were failing, but because a massive bet on nuclear power had gone catastrophically wrong.

The roots go back a decade. In February 2006, Toshiba acquired Westinghouse Electric Company from British Nuclear Fuels Limited (BNFL) for $5.4 billion. The price looked steep even then, but Toshiba’s leadership thought they were buying into a once-in-a-generation upswing—a nuclear renaissance. Climate concerns would push countries toward carbon-free baseload power. Fast-growing economies would need new capacity. And Westinghouse’s AP1000 reactor design, marketed as safer and quicker to construct, would be the product that rode the wave.

Two assumptions sat underneath the deal. First: there would be a large, expanding global market for new nuclear plants. Toshiba’s own announcement at the time projected that by 2020 the market for nuclear power generation would grow by 50% compared with then-current levels. Toshiba’s president and CEO also estimated the world would build about ten large, one-gigawatt reactors every year through 2020. That forecast missed reality by a wide margin.

Second: even if demand came in lumpy, Westinghouse could execute in the United States, one of the world’s toughest regulatory environments, on first-of-a-kind projects. That bet started failing before Fukushima ever happened.

Then Fukushima hit in 2011, poisoning public sentiment and slowing approvals worldwide. But Toshiba’s immediate problem wasn’t abstract reputational damage. It was concrete, steel-and-rebar chaos in the U.S., where Westinghouse’s projects were spiraling: the AP1000 expansions at Vogtle in Georgia and at the Virgil C. Summer Nuclear Generating Station in South Carolina. Cost overruns mounted. Schedules slipped. Losses ballooned.

On March 29, 2017, Westinghouse filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy. Toshiba warned the yearly loss tied to the collapse could exceed $9 billion—nearly triple prior estimates. Toshiba also projected its annual loss could more than double to a record 1.01 trillion yen (about $9.1 billion). The numbers weren’t just bad. They were existential.

The Desperate Sale

The nuclear catastrophe put Toshiba’s listing at risk. Under Tokyo Stock Exchange rules, companies with negative shareholders’ equity can face delisting. Toshiba needed cash—fast—and it really only had one asset big enough to generate it: the memory chip business.

So in early 2017, Toshiba officially announced plans to sell its semiconductor business, driven by the urgency of shoring up its balance sheet before negative equity forced a crisis.

The irony was brutal. The technology Toshiba had once treated as a distraction—the flash memory lineage that began with Masuoka—had become the crown jewel. The business that had spent years fighting for internal attention was now the lifeboat.

A bidding frenzy followed, and rumors flew about who would buy it. Western Digital was one of the most plausible contenders—and also the most contentious. WD had acquired SanDisk the year before, which meant it inherited Toshiba’s NAND joint venture partner position. Western Digital sued Toshiba, arguing that the joint venture agreements effectively gave it veto rights over any sale. Toshiba fired back, suing Western Digital for more than $1 billion for interference.

The courtroom fight injected uncertainty into everything. A deal this large can survive price negotiations. It can survive regulators. What it can’t survive is a buyer—or an aggrieved partner—who can credibly threaten to block the transaction entirely. Toshiba’s growing distrust of Western Digital, fueled by the legal war, ended up shaping who Toshiba was willing to sell to.

The Buyers: An Unusual Consortium

In the end, Toshiba agreed to a ¥2 trillion (about $18 billion) sale of the memory business to a Bain Capital-led consortium. This wasn’t a typical private equity buyout where the sponsor shows up with leverage and a clean cap table. It was a coalition built to satisfy strategy, supply security, and politics all at once.

The group included Apple, Dell Technologies Capital, Kingston Technology, and Seagate. Those investors took non-voting shares and weren’t intended to participate in governance or day-to-day operations. Their role was less about running the company and more about ensuring supply and stability.

Apple’s presence was especially revealing. Flash memory is a critical input for consumer devices, and Apple had strong incentives to broaden its supplier base and reduce dependence on rivals—particularly Samsung—for high-end compact memory. Supporting the Bain consortium also made it more attractive to Toshiba: Apple was effectively signaling, “This business will have customers.”

The deal was also structured in a way that made it easier to sell politically. According to many analysts, a Bain-led consortium that included government-linked investors was more likely to get approval in Japan, where keeping advanced manufacturing capabilities and production heritage under domestic influence mattered.

On June 1, 2018, the acquisition closed. Seagate disclosed that it funded an investment of about $1.27 billion using cash from its balance sheet.

Most importantly, the control economics landed with Bain: over 56% of the stake was sold to the consortium led by Bain Capital, alongside partners including SK hynix, Dell, Apple, Seagate, and Kingston. SK hynix—one of Kioxia’s direct competitors in NAND—ended up with significant economic exposure through convertible bonds that translate to about a 15% stake.

That detail would become a plot device later. What was meant to be financing rather than strategic control created real governance complexity. SK hynix had a meaningful interest in Kioxia’s future, and that position would later give it substantial influence over Kioxia’s strategic options—most notably, the proposed merger with Western Digital.

V. Kioxia: The Rebirth (2019-2023)

A New Identity

On July 18, 2019, Toshiba Memory Holdings Corporation announced it would change its name to Kioxia on October 1, 2019, across the group. When that date arrived, Toshiba Memory Holdings Corporation became Kioxia Holdings Corporation, and Toshiba Memory Corporation became Kioxia Corporation.

The name was meant to do a lot of work. Kioxia blended the Japanese word kioku, meaning “memory,” with the Greek word axia, meaning “value.”

But the rebrand wasn’t just cosmetic. For decades, this business had lived inside Toshiba—sometimes underfunded, often overshadowed, and constantly competing for attention. Now it was supposed to stand on its own. Independence, however, didn’t arrive as a clean slate. It came with a complex ownership structure and substantial debt, the inevitable residue of the Bain-led rescue deal.

Publicly, the company leaned hard into a story it had earned decades earlier: inventor of NAND flash. It was a reclamation of history—especially after the bizarre era when Toshiba’s own press operation had credited Intel with inventing flash. Kioxia’s message was clear: this time, the origin story would be told correctly.

Then reality showed up, immediately, with the kind of problems only semiconductor manufacturing can deliver.

Operational Challenges

In June 2019, Toshiba Memory Holdings Corporation suffered a power cut at one of its factories in Yokkaichi, Japan. The result was brutal: at least 6 exabytes of flash memory output lost, with some estimates putting the hit even higher.

That’s the uncomfortable truth about running the world’s storage infrastructure: the system is engineered to near-perfection, but it’s not forgiving. A single disruption can wipe out massive volumes of product and send shockwaves through customers and pricing.

And the shocks didn’t stop there. In February 2022, Kioxia and Western Digital disclosed that contamination issues had affected production at their joint facilities in Japan—Yokkaichi and Kitakami—impacting about 6.5 exabytes of flash memory output. The affected fabs were taken offline in early February and returned to normal operations nearly a month later.

These weren’t isolated factories. Together, the WD–Kioxia joint production base accounted for close to a third of global NAND supply at the time. TrendForce estimated their share at 32.5% in the third quarter of 2021. So when those lines stopped, the effects didn’t stay inside Japan. They rippled across the world’s supply chains.

The timing was especially painful. The 2019 outage landed right as the company was trying to celebrate its fresh start. The 2022 contamination hit while Kioxia was trying to convince markets it was ready for an IPO—exactly the moment when “manufacturing reliability” stops being an engineering metric and becomes an investor question.

The Failed IPO Saga

Kioxia’s path back to the public markets turned into a long stall.

The company first filed for an IPO in 2020. The logic was straightforward: raise capital, refinance, and give Bain and the other stakeholders a credible path to liquidity. But almost everything that could complicate a semiconductor IPO arrived at once.

COVID scrambled demand patterns and pricing. The U.S.-China trade conflict raised new uncertainty around selling into China, a major part of the NAND market. And the idea of a merger with Western Digital kept resurfacing, repeatedly reshaping the narrative Kioxia would need to sell to public investors.

At one point, Kioxia had filed to list on the Tokyo Stock Exchange in August, with plans to go public in October. That plan didn’t hold. A downturn in the chip market and an inability to secure the valuation it wanted forced a postponement. Reuters reported that investors were urging Bain to cut its IPO valuation target from about 1.5 trillion yen to nearly half that, and the pressure helped push Bain to drop the October timetable.

Underneath all the scheduling drama was a basic mismatch. Bain needed an outcome that justified the $18 billion price paid in 2018. Public market investors looked at Kioxia and saw a cyclical memory manufacturer walking into fierce competition, operational fragility, and a NAND market that punishes anyone who shows up at the wrong point in the cycle. That valuation gap didn’t close quickly.

So Kioxia stayed stuck: too important to ignore, too complicated to price—waiting in private-market limbo while Samsung and SK hynix kept investing and pushing the frontier forward.

VI. The Western Digital Merger Drama (2021-2023)

The Logic of Consolidation

By the early 2020s, NAND looked like an industry begging for a grown-up moment. There were only a handful of serious players left, but the basic dynamics hadn’t changed: building fabs costs billions, pricing moves in brutal cycles, and in many segments the product still behaves like a commodity. If you’re not big, you’re fragile.

That’s what made the idea of a Western Digital–Kioxia tie-up so alluring. Kioxia was the No. 2 NAND flash player globally, Western Digital No. 4. Put them together and you don’t just get bigger—you get something that looks, on paper, like a true counterweight to Samsung.

And unlike most “synergy” stories, this one had real plumbing behind it. Western Digital and Kioxia were already joined at the hip operationally, running joint manufacturing ventures and sharing fabrication capacity in Japan. Their technology roadmaps were aligned. Their product portfolios didn’t collide as much as they filled gaps. A merger promised the classic benefits: remove duplicated overhead, coordinate investment, and build enough scale to weather the next downcycle without panicking.

At peak optimism, the combined business was projected to sit at roughly the same market share as Samsung—around the low 30s—creating a two-giant structure that would have left everyone else, including SK hynix, staring up at much larger competitors.

SK Hynix: The Spoiler

But Kioxia’s ownership structure had a tripwire built into it. SK hynix—one of Kioxia’s direct rivals—had joined the Bain-led consortium back in 2018. What looked like financial participation at the time became strategic leverage later.

By 2023, SK hynix was the world’s third-largest NAND supplier, and it didn’t like the idea of its competitor fusing with Western Digital into a near-Samsung-sized heavyweight. SK hynix had invested more than $2.6 billion into the consortium, and it argued that the merger could hurt the value of that investment and reshape the competitive landscape against it.

After more than two years of on-and-off talks, the WD–Kioxia deal collapsed late in the process because the parties couldn’t get a key stakeholder comfortable. On an earnings call, SK hynix CFO Woohyun Kim put it plainly: SK hynix wasn’t agreeing to the deal because of its impact on the value of its investment in Kioxia.

The awkward part was that Western Digital and Kioxia never formally confirmed the merger talks publicly—even as the market treated them like the industry’s worst-kept secret. But by the time the discussions fell apart, the message was clear: the consolidation that made the most industrial sense couldn’t survive the cap table.

And the consensus from industry sources was even more sobering: SK hynix was expected to keep opposing any attempt to merge Kioxia and Western Digital.

The Strategic Stalemate

That left Kioxia in a strange bind. The very structure that enabled Toshiba’s memory business to survive—Bain plus strategic investors plus SK hynix—also boxed it in. SK hynix’s position, held through convertible instruments with governance hooks, effectively gave a competitor a seat at the table for the biggest strategic decision Kioxia could make.

Meanwhile, SK hynix wasn’t standing still. It was upgrading its own position, closing the first phase of its acquisition of Intel’s SSD business and the Dalian NAND flash manufacturing facility in China—an operation that would be branded Solidigm—after receiving merger clearance from China’s State Administration for Market Regulation on Dec. 22. The first phase of the transaction involved a $7 billion payment.

Strategically, the contrast was sharp. Western Digital and Kioxia were trying to merge to get stronger in enterprise SSDs and data-center storage. SK hynix, at the same time, was buying its way deeper into that exact market. Intel’s legacy brought valuable enterprise SSD footholds and floating gate NAND technology—assets that help in the high-performance segments where margins are better and customer relationships are stickier.

So from the outside, it looked like a master class in competitive positioning: prevent your rival from getting bigger, while you get bigger yourself.

For Kioxia’s investors, the failed merger was more than a missed opportunity—it was an ongoing overhang. The company remained smaller than Samsung and constrained by a shareholder structure that made big moves hard. Whether the stalemate would eventually break through renewed merger talks, a change in SK hynix’s posture, or some other restructuring was unclear. What was clear is that Kioxia’s future wasn’t just being shaped by technology and markets—it was being shaped by who owned it, and what they were willing to let it become.

VII. The IPO and Current Era (2024-Present)

Finally Going Public

After years of delays, Kioxia finally made it to the public markets in December 2024.

On December 18, 2024, it listed on the Tokyo Stock Exchange Prime Market. DealWatch called it a landmark deal—“an unprecedented large-scale IPO adopting Japan’s first pre-approval notification (S-1) procedure”—and noted that the company had been in active discussions with institutional investors to land on a price the market would actually take.

That price was 1,455 yen per share, implying a valuation of 784 billion yen (about $6.6 billion). Reuters reported the IPO raised 120 billion yen (about $800 million), including the overallotment.

The offering also started to unwind the ownership tangle left over from the 2018 rescue. Post-IPO, the Bain-led consortium’s stake fell to 52% from 56%, and Toshiba’s dropped to 32% from 41%.

But the most telling part wasn’t the mechanics of the deal. It was what the price said about the last seven years. In 2017, Foxconn had offered $30 billion for the business. In 2022, Western Digital had floated a $20 billion offer. Kioxia’s public-market debut came in at roughly a quarter of those earlier marks—a public reminder of how brutally cyclical, capital-intensive, and confidence-driven the memory business can be.

And unless you live and breathe Japan’s markets, you probably didn’t even notice it happened. The IPO took place a couple days earlier than initially planned, Kioxia listed as number 285A, and outside Japan it barely made a ripple in the press.

Current Market Position

By late 2024, Kioxia was still very much a top-tier NAND player. TrendForce estimated that in the third quarter of 2024, Kioxia ranked third in NAND flash revenue with a 15.1% share, behind Samsung at 35.2% and SK Group at 20.6%. Beyond NAND, Kioxia was also positioning itself around next-generation memory technologies, aiming not to get boxed into a single product cycle.

The AI boom has been a real tailwind. Demand from AI servers and the broader refresh cycle for traditional servers lifted SSD and storage revenue, with data center and enterprise SSD sales contributing roughly half of that segment’s revenue.

The financial recovery showed up clearly in the full-year results: FY2024 revenue of ¥1.706 trillion (about $11.28 billion), up 58.5% year over year, and an IFRS profit of ¥272.3 billion (about $1.77 billion), a sharp reversal from the prior year’s ¥243.7 billion loss.

Still, the market’s relationship with memory stocks remains volatile. Kioxia’s share price has swung sharply on sentiment and guidance. At one point, shares fell 23% after the company’s outlook for the current quarter missed high expectations, right as global investors were backing away from richly valued tech names.

There’s also a structural issue hanging over the stock. A Nikkei report noted that companies on the Tokyo Stock Exchange Prime Market are required to have at least 35% of shares publicly traded within five years. Kioxia’s ratio stood at 28%, so the company planned to push its two biggest shareholders—Bain Capital and Toshiba—to sell more stock over the next three years, with the goal of meeting the threshold by 2030.

Strategic Outlook

Kioxia’s pitch for the next era is straightforward: keep technology leadership, and translate it into higher-value products. The company says it wants to meet increasingly diverse demand for high-performance, high-capacity storage with low power consumption, and to grow its SSD business with products tuned for the needs of AI systems.

It has also laid out financial guardrails. Kioxia plans to keep capital expenditures below 20% of revenue, hold R&D spending at about 8–9% of revenue, and strengthen R&D and production capacity by hiring around 700 people per year. Longer term, it has targeted average operating income in the mid-20% range, driven by a richer mix of SSD sales and lower unit costs per gigabyte.

On the technology front, the roadmap remains competitive. Kioxia has begun investing in BiCS 10, a 332-layer 3D NAND technology it frames as the next growth engine, with a 9% bit-density improvement compared to BiCS 8 (218 layers).

And the product cadence has continued. In February 2025, Kioxia and SanDisk demonstrated a 4.8 Gb/s Toggle DDR 6.0 interface and a 332-layer die, aimed at speeding time-to-market for high-bandwidth flash used in AI-focused systems. In June 2025, Kioxia rolled out its CD9P Series PCIe 5.0 NVMe SSDs built on 8th-gen BiCS FLASH—another signal that, even after the IPO drama and merger stalemates, the company’s real battleground is still the same as it’s always been: shipping better memory, at scale, into the world’s most demanding infrastructure.

VIII. The Competitive Landscape: Porter's 5 Forces Analysis

1. Threat of New Entrants: MODERATE-HIGH

On paper, NAND is a fortress. A leading-edge fab can cost tens of billions of dollars, takes years to ramp, and requires process expertise that you can’t just hire or buy off the shelf. Historically, those realities have protected the incumbents.

But geopolitics has started punching holes in that logic.

The standout example is China’s YMTC. Despite export-control constraints, YMTC still captured an estimated 6% market share in 2024, carving out footholds where it can—especially in QLC-focused cloud tenders. State backing matters here: Chinese government subsidies effectively lower the capital barrier for domestic champions, and restrictions on foreign tools have had a paradoxical effect. They slow access to cutting-edge equipment, but they also concentrate political will and money into building indigenous capability.

The result is a market that’s starting to split in two. Non-Chinese suppliers can be relatively insulated in Western markets by export controls and alliance politics, while Chinese suppliers increasingly dominate demand at home.

For Kioxia, that’s both a cushion and a warning. Japan’s alignment with the U.S. creates near-term protection in key customer bases. But the long-term risk is straightforward: if the catch-up story succeeds, today’s moat becomes tomorrow’s new competitor.

2. Bargaining Power of Suppliers: MODERATE

If NAND is a fortress, the gatekeepers are the equipment vendors.

Modern semiconductor manufacturing runs on a small set of highly specialized suppliers. ASML dominates advanced lithography. Applied Materials, Lam Research, and Tokyo Electron control major process steps. The chemicals and gases that make the whole thing work come from a narrow, tightly qualified supplier base.

That concentration gives suppliers meaningful pricing power—especially during build booms. When the industry collectively decides it needs more capacity, lead times stretch, tool availability tightens, and pricing moves in the suppliers’ favor.

Kioxia gets some help from scale, particularly through its joint venture with Western Digital, which can improve purchasing leverage through combined volumes. But the structural reality doesn’t change: no single memory maker is big enough to dictate terms to the companies that sell the shovels.

3. Bargaining Power of Buyers: HIGH

On the other side of the table, Kioxia faces some of the most powerful buyers on earth.

Apple alone buys enormous volumes of NAND for iPhones and other devices—and it’s sophisticated, price-sensitive, and willing to multi-source. Hyperscalers like AWS, Google, and Microsoft buy SSDs in staggering quantities. Meanwhile, PC and smartphone OEMs operate on thin margins and push hard on pricing.

A big reason buyers have leverage is that much of NAND still behaves like a commodity. In many consumer categories, customers can switch between Samsung, SK hynix, Kioxia, and Micron with limited friction. That interchangeability keeps supplier margins under pressure.

The mix shift matters here. In 2024, triple-level cell (TLC) accounted for 64.2% of NAND flash revenue share, while quad-level cell (QLC) is projected to grow at a 6.66% CAGR through 2030. As QLC adoption expands—especially in cloud—buyers get another lever: more bits per dollar, more pricing pressure, and more incentive to treat NAND as interchangeable.

That’s why Kioxia keeps pushing toward higher-value positioning. Enterprise and data center SSDs are harder to win and slower to qualify, but they can offer better pricing dynamics because performance, endurance, and validation matter. The strategy isn’t complicated: escape pure commodity physics by selling more of the “product,” not just the “bits.”

4. Threat of Substitutes: LOW-MODERATE

NAND’s best defense is that there isn’t a credible replacement at scale.

Hard disk drives keep losing ground to SSDs, so the substitution trend is flowing toward NAND, not away from it. Emerging memories like MRAM and ReRAM are real technologies, but they mostly live in niches and can’t match NAND’s cost-per-bit for mainstream storage.

And it’s worth remembering just how entrenched NAND has become. Since Toshiba—now Kioxia—commercially launched NAND flash in 1987, it’s expanded from a clever memory chip into a foundational component of everything from smartphones to data centers.

The longer-term uncertainty is more about adjacency than replacement. “Storage-class memory” concepts aim to narrow the performance gap between DRAM and NAND, potentially taking slices of certain high-performance workloads. But these technologies remain far from meaningful scale, and they’re more likely to complement NAND than erase it.

So the substitution risk isn’t the scary part. The real risk is internal: commoditization within NAND itself.

5. Industry Rivalry: VERY HIGH

This is where the NAND business feels most like a knife fight.

The industry has spent years wrestling with overcapacity, amplified by the COVID-era demand surge and the whiplash that followed. Margins get squeezed, everyone cuts, then everyone invests again—because nobody can afford to fall behind on technology. Sustainable improvement is hard without consolidation, and consolidation has proven politically and structurally difficult.

The competitive set is tight and brutal: Samsung, SK hynix (including Solidigm), Kioxia, Western Digital, and Micron. They compete through a mix of layer counts, controller performance, cost per bit, and manufacturing execution—while pricing, in many segments, still snaps back to commodity dynamics.

Samsung’s scale makes it the gravitational center. With roughly the mid-30% range of market share, it can behave like the de facto pace-setter. Everyone else has to react.

The Kioxia–Western Digital merger failure was the clearest signal that “industry logic” isn’t enough. The deal could have created a true counterweight to Samsung, but cap-table incentives—especially SK hynix’s position—got in the way. Meanwhile, SK hynix’s acquisition of Intel’s NAND business shows that consolidation can happen, just not always where the rest of the market expects.

By 2024’s second quarter, Samsung remained the leader by revenue share (36.9%), with SK Group second (22.1%). Kioxia followed (13.8%), then Micron (11.8%) and Western Digital (10.5%). In other words: five players, constant pressure, and not much room to breathe.

IX. Hamilton's 7 Powers Framework Analysis

1. Scale Economies: PRESENT (but not dominant)

Kioxia’s Yokkaichi Plant is one of the world’s largest and most efficient flash memory production facilities.

Between Yokkaichi and Kitakami, Kioxia has real manufacturing heft. And because so much of its production is intertwined with Western Digital through joint ventures, it also gets shared fab economics that would be brutally expensive to recreate alone.

But this is NAND, and “large” is a relative term. Samsung and SK hynix run at comparable or greater scale, which blunts the advantage. Kioxia is big enough to stay in the top tier, yet not big enough to turn scale into a knockout punch.

At the end of the day, scale in NAND is about spreading fixed costs—fab capex and process R&D—across as many gigabytes as possible. Kioxia can compete on that basis. It just can’t dominate.

2. Network Effects: ABSENT

There are no network effects in memory chips. A gigabyte of NAND doesn’t become more valuable because everyone else is using NAND. There’s no ecosystem flywheel, no platform lock-in, no marketplace dynamic.

That’s typical for semiconductor components, and it’s a constraint. Without network effects, Kioxia doesn’t get to win by default. It has to win the hard way: cost, performance, reliability, and relationships.

3. Counter-Positioning: LIMITED

Counter-positioning is when a newcomer adopts a model incumbents can’t copy without hurting themselves. In theory, you could argue Kioxia has a cleaner identity as a memory-focused company compared with a diversified giant like Samsung.

In practice, it doesn’t buy much. Samsung’s memory unit largely operates on its own, and SK hynix is already a memory specialist. The structure of the industry leaves little room for a clever “we’re different” play that others can’t follow.

4. Switching Costs: MODERATE in Enterprise, LOW in Consumer

Switching costs are where the NAND market splits in two.

In enterprise and data center SSDs, they’re real. Qualification takes time, testing is rigorous, firmware and support relationships deepen, and buyers don’t love surprises in mission-critical systems. That creates stickiness, helps defend share, and can support better pricing.

In consumer and mobile, switching is much easier. Smartphone makers can qualify multiple suppliers and shift volumes based on price and availability. This difference is a big part of why Kioxia keeps pushing toward higher-value enterprise and data center products: it’s where loyalty can actually exist.

5. Branding: MINIMAL

For most people, NAND is invisible. Nobody buys a phone because it has Kioxia inside instead of Samsung or SK hynix.

Brand does matter somewhat in enterprise procurement, where reputation for reliability, responsiveness, and long-term support can influence decisions. But even there, it’s modest. In memory, specs and supply tend to overpower logos.

6. Cornered Resource: PARTIAL (Patents and Technology)

Kioxia has deep intellectual property built over decades of NAND development, including its BiCS FLASH technology and a wide portfolio of process patents. That provides some protection and can support licensing.

But NAND is also a world of cross-licenses and détente. The big players tend to sign peace-treaty-style agreements because everyone’s technology stacks are interdependent and litigation is mutually assured destruction. So yes—Kioxia’s IP matters. No, it’s not a true cornered resource in the Hamilton Helmer sense.

7. Process Power: DEVELOPING

Process power is the advantage that comes from hard-to-copy organizational know-how—how a company actually operates, not what it claims to have.

Kioxia has meaningful manufacturing expertise from decades of producing NAND at scale. That shows up in its ability to roll BiCS generations forward and hit workable yields on some of the most finicky processes in the semiconductor world.

The catch is that its rivals have been doing the same thing for just as long. Kioxia’s process capability is real, but the differential is limited—more table stakes than secret weapon.

X. Bull Case and Bear Case

Bull Case

The bull case for Kioxia starts with a simple shift in the ground beneath the industry. AI is changing what NAND is for. If flash used to be pulled mainly by phones, PCs, and consumer gadgets—classic boom-bust markets—AI infrastructure pulls differently. Storage becomes part of the machine, not an accessory to it. And forecasts now suggest that by 2029, nearly half of NAND demand could be AI-related. If that’s even directionally right, Kioxia doesn’t need to “win” the whole market to win. As the world’s third-largest NAND supplier, it just needs to stay in the top tier and ride the wave.

Second, the technology is still credible. BiCS FLASH has kept Kioxia in the conversation with Samsung’s V-NAND and SK hynix’s stack. That matters because, in NAND, cost and density are destiny. Kioxia’s plan to keep R&D at roughly 8–9% of revenue is essentially an admission of the rules of the game: you don’t get to coast, but you can keep up—and keeping up is enough to keep your seat at the table.

Third, the industry still feels like it wants to consolidate. The logic that powered the Western Digital merger talks hasn’t gone away: fewer players, more discipline, better economics. Whether that comes back in the form of renewed WD discussions, some kind of reconfiguration with SK hynix (which holds convertible bonds that could convert into equity), or an entirely different deal structure, the gravitational pull is still toward bigger, more stable platforms. If consolidation happens, Kioxia is one of the few pieces that can actually move the board.

Fourth, Kioxia may have the wind at its back at home. Japan’s push to rebuild a domestic semiconductor footprint—and to reduce dependence on China-centered supply chains—creates a policy environment that’s more supportive than it was in the era when Toshiba treated memory as just another division. For a company that manufactures in Japan and sits in a geopolitically friendly bucket, that matters.

And fifth: the market may have started Kioxia’s public life with an unusually low bar. If investors continue to re-rate the stock, the upside can be meaningful—especially for those who got in early after the IPO.

Bear Case

The bear case is that NAND is still NAND, and structural physics are hard to wish away.

First, Kioxia is still smaller than the companies that set the pace. Samsung and SK hynix have scale advantages that show up everywhere—capex endurance, process learning curves, negotiating leverage, and the ability to survive brutal pricing periods without flinching. And there are signs that Kioxia has been one of the share losers, alongside Micron and Western Digital, with Kioxia’s slippage standing out. In a commodity-leaning business, losing share is often losing cost position, and losing cost position is how you end up trapped.

Second, the company carries meaningful debt—part of the legacy of the buyout structure that created Kioxia in the first place. The IPO helped, but leverage still matters in a cyclical, capital-hungry industry. It limits flexibility at exactly the moments when flexibility is most valuable: downcycles, technology transitions, or when an acquisition opportunity appears.

Third, the cap table remains a strategic complication. SK hynix is both a competitor and a stakeholder, which creates governance friction that doesn’t exist for most peers. Any move that requires broad alignment—especially a transformative deal—can run into a veto-shaped problem from a party with conflicting incentives.

Fourth, Chinese competition is a slow-burn risk that doesn’t show up until it does. Export controls can delay capability, but they rarely stop it forever. YMTC’s progress suggests that a domestic Chinese NAND champion could eventually become credible beyond China, especially if it keeps improving layer counts and cost structure over time.

And fifth, memory pricing still behaves like a cycle with better marketing. Even in 2025, reports indicated that major players—Samsung, SK hynix, Kioxia, and Micron—were scaling back NAND production in the second half of the year, pushing prices higher. When an industry needs coordinated production cuts to restore profitability, it’s a sign the boom-bust engine is still running. AI demand can raise the floor, but it may not eliminate the ceiling—or the crash that follows it.

XI. Key Performance Indicators to Monitor

If you want to tell whether Kioxia’s post-IPO story is getting better or just getting noisier, watch three signals:

1. Enterprise SSD Revenue Mix: How much of Kioxia’s revenue is coming from enterprise and data center SSDs—about 60% of the SSD & Storage segment today—tells you whether the company is successfully climbing out of pure commodity NAND. If that mix keeps rising, it’s a sign Kioxia is winning more of the AI and cloud infrastructure workload where margins tend to be better.

2. Bit Shipment Growth Relative to Industry: In NAND, market share is written in bits shipped. Compare Kioxia’s bit shipment growth each quarter against the broader industry, as tracked by firms like TrendForce. If Kioxia consistently grows faster than the market, it’s gaining share. If it lags, the problem usually isn’t just a bad quarter—it’s that someone else is executing better on cost, technology transitions, or customer pull.

3. Operating Margin Trajectory: Management has set an ambition of mid-20% operating margins at scale. The question is whether Kioxia can steadily move toward that level now that it has only recently returned to profitability after years of losses. Improving margins would suggest the company is actually delivering on the two levers that matter most in this business: lower cost per bit and a richer product mix.

XII. What's Next for Kioxia

Kioxia is back on the public markets, profitable again, and shipping competitive technology into the hottest demand cycle storage has seen in years. That’s the good news. The harder truth is that the company is also still at a strategic crossroads—and the most “obvious” next move is the one it has circled for years: reopening merger talks with Western Digital’s NAND business, now operating under the SanDisk name.

With both companies publicly listed, that conversation would start on cleaner footing than before. Prices are public. Governance is clearer. And the industrial logic hasn’t changed: combine two already-entangled manufacturing partners and you’d create a bigger, more durable platform—one that, in terms of bit shipments, wafer output, and revenue, could sit as the clear No. 2 in NAND.

But nothing about Kioxia’s future is just a spreadsheet problem, because the cap table is still destiny. SK hynix’s influence remains the central complication. Through its convertible bonds, SK hynix has a path to roughly 15% ownership of Kioxia upon conversion, and its broader participation in the Bain-led consortium only adds to its leverage. In practical terms, that means any transformative deal—especially one that reshapes the competitive landscape—likely needs SK hynix to sign off.

And there’s a further wrinkle: SK hynix isn’t just a stakeholder. It’s a rival. With that position, it could theoretically use its ownership rights not just to block a Western Digital tie-up, but to angle for something even bigger—positioning itself as a contender to take over Kioxia outright. For SK hynix, the strategic temptation is obvious: gain technology, capacity, and share in one move.

So, looking out over Kioxia’s medium-term future, three paths emerge:

Scenario 1: Renewed Western Digital Merger. With both companies now publicly traded, merger discussions could restart on a more transparent basis. But the deal doesn’t happen unless SK hynix’s objections are addressed—likely through a structure that preserves its economic interests in whatever combined entity emerges.

Scenario 2: SK Hynix Acquisition. SK hynix could convert its bonds and pursue a full acquisition of Kioxia, creating a NAND heavyweight built to challenge Samsung. Strategically, it would remove a competitor while locking up Kioxia’s manufacturing footprint and IP. The biggest obstacle would be regulatory and political: Japan has strong incentives to keep control of strategic semiconductor assets close to home. Still, in a world where U.S., Korea, and Japan increasingly coordinate on technology policy, approval isn’t impossible—it’s just hard.

Scenario 3: Continued Independence. Kioxia stays standalone and tries to win the hard way: relentless technology investment, a continued pivot toward higher-value enterprise SSDs, and a steady reduction in debt to regain flexibility. This is the cleanest governance story—but also the most execution-dependent.

For investors, Kioxia is a bet on flash memory’s central role in the AI era, filtered through the most ironic corporate arc imaginable: the company that invented NAND, nearly squandered it through neglect, and is now fighting to capture value in the market it helped create. The inventor’s paradox hasn’t gone away. Having the breakthrough is necessary, but not sufficient. In semiconductors, winners are ultimately determined by execution, capital allocation, and who has the freedom to make the next move.

Fujio Masuoka, now in his eighties, has lived that paradox personally—watching his invention reshape the world while recognition arrived late and unevenly. Kioxia’s trajectory mirrors his story in corporate form: brilliant innovation, institutional inertia, a near-death crisis, and a long, unfinished push to claim credit in an industry that wouldn’t exist without its foundational contribution.

Whether Kioxia finally captures the value its technology unleashed—or remains a cautionary tale about the gap between invention and commercial success—is still being written. The story continues.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music