Kikkoman Corporation: 400 Years of Soy Sauce and the Art of Global Domination

I. Introduction: The Improbable Journey from Shogun's Table to Every American Kitchen

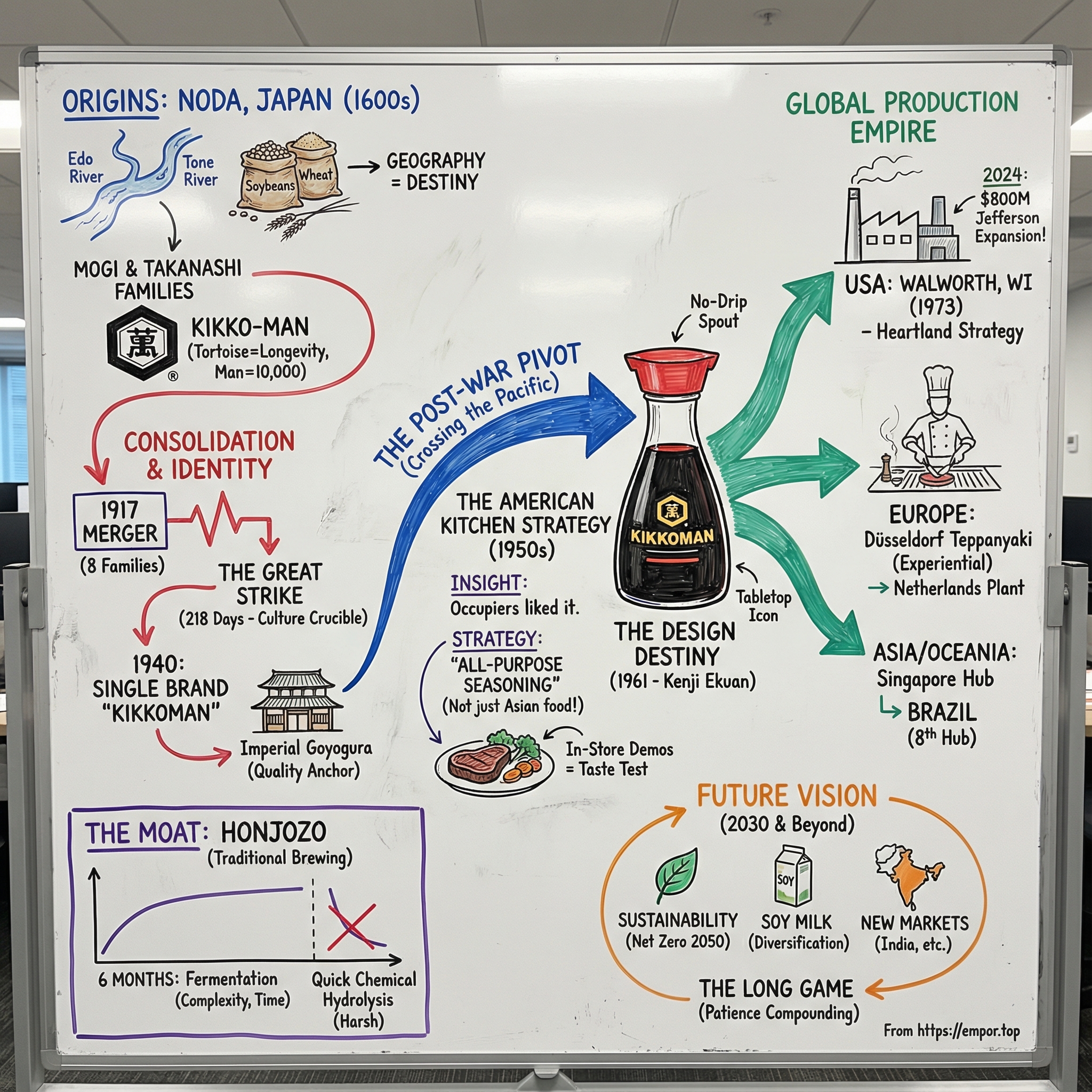

Picture a dark, aromatic liquid so central to Japanese cooking that it was served to the Tokugawa Shogunate itself, the seat of feudal power. Now jump forward a few centuries and picture that same product in the U.S., parked in the pantry between ketchup and mustard, a default seasoning in millions of homes.

That’s the Kikkoman story.

It begins in the mid-1600s in Noda, a farming town along the Edo River not far from present-day Tokyo, where a resourceful family built a soy sauce brewery. Nearly twenty generations later, their descendants still run what has become the world’s leading soy sauce brand. Along the way, a local staple became a global standard—proof that even the most “commodity” of products can be engineered into something like a cultural institution.

Today Kikkoman spans far more than soy sauce: seasonings and flavorings, mirin, shōchū and sake, beverages like juice, pharmaceuticals, and even restaurant management. But soy sauce remains the beating heart. As of 2002, Kikkoman was the world’s largest producer of soy sauce, and it’s the most popular soy sauce brand in both Japan and the United States.

Which raises the central question that drives everything that follows: how did family soy sauce brewers from one Japanese town, four hundred years ago, become the global benchmark for a condiment used in more than 100 countries?

The answer is hiding in plain sight—starting with the name. “Kikko” refers to a tortoise shell; “man” means ten thousand. In Japanese folklore, the tortoise symbolizes longevity and steady progress, said to live ten thousand years. The logo—a hexagon like a tortoise shell with the character for “ten thousand” at its center—captures the company’s self-image in a single mark: built to endure, built to travel.

And that’s exactly what happened. Over four centuries, the founding families didn’t just keep a business alive. They built a playbook: how to turn a regional craft into a premium global brand, how to localize without losing quality, and how to blend family continuity with professional management.

Yuzaburo Mogi, Kikkoman’s Honorary CEO and Chairman, puts the modern outcome plainly: “Kikkoman is now sold in over 100 countries, and overseas business accounts for over 70% of our sales and over 80% of our profits.” Read that again. This isn’t a Japanese exporter dabbling abroad. It’s a Japanese company whose center of gravity moved outward—and, in many ways, whose biggest success story was written in the American kitchen.

As of fiscal year 2025, Kikkoman reported revenue of 709.0 billion yen and business profit of 77.3 billion yen, with 56 group companies worldwide. But the numbers are the scoreboard, not the game. The real story is a long arc of family perseverance, marketing creativity, design innovation, and perhaps the most patient brand-building campaign in corporate history.

So let’s go back to the beginning: to Noda, the river town where geography, fermentation, and ambition first met.

II. Origins: The Geography of Fermentation (1600s–1917)

Noda: Where Rivers, Soybeans, and History Converge

To understand why Kikkoman exists at all, you have to start with a map.

In the 17th century, the forefathers of the Mogi family began brewing that dark, savory seasoning—made from soybeans, wheat, water, and salt—in Noda, a town set along the Edo River. On its own, that’s just another origin story. What made it destiny was location.

Noda sat on the Kanto Plain, one of Japan’s best regions for growing both soybeans and wheat—the essential building blocks of soy sauce. And it wasn’t just fertile land. Noda was also wedged between two major waterways, the Tone River and the Edo River. In a world without highways, rivers were infrastructure. They moved grain and salt in, and they moved finished soy sauce out—straight to Edo, the fast-growing city that would become Tokyo.

So yes, geography mattered. But it wasn’t passive luck. The brewers in Noda were, in effect, early supply-chain strategists. They placed themselves right where ingredients were plentiful and where demand was compounding—and they kept showing up there, generation after generation.

The Mogi and Takanashi Dynasties

Kikkoman would eventually become the world’s largest shoyu manufacturer, and “the one most responsible for introducing shoyu to the West.” But for centuries, it wasn’t a single company. It was families.

The modern corporation was formed in 1917 in Noda, when eight family-owned producers—rooted as far back as 1603—merged. The names that matter most are the Mogi and Takanashi families, whose brewing businesses had grown up side by side in the same river town.

One figure in particular signals what separated these families from countless other regional brewers: Mogi Saheiji. Head of the oldest branch household of the Mogi line in Noda, he began making shoyu in 1782, building on existing family businesses in miso and grain.

But Saheiji wasn’t only thinking about production. He was thinking about identity—about what we’d now call brand.

In 1838, in a move that was unusual for the time, he petitioned for and received central government registration of the brand name Kikkoman. That same year, Kikkoman brand shoyu was designated as the soy sauce supplied to the Tokugawa Shogunate—the shogun. It remained so until the shogunate fell in 1868.

That kind of endorsement did more than sell bottles. It turned soy sauce into reputation. It told merchants and households that this wasn’t just shoyu—it was the shoyu.

And the Mogis kept pushing. Their promotion paid off with a first-place medal at the All-Japan Industry Promotion Fair in 1881. Then, in 1883, Kikkoman won a gold medal at the World’s Fair in Amsterdam—international recognition, decades before “global Japanese brands” were a category anyone talked about.

Even more striking: Kikkoman was registered in California as a legally recognized brand name in 1879—a move that, remarkably, came six years before the same legal protection in Japan.

That’s not a footnote. It’s a tell. These weren’t just brewers. They were long-horizon operators, thinking about markets and legal moats across the Pacific while Japan was still modernizing at home.

The 1917 Merger: Consolidation in Crisis

Then came World War I—and with it, a market that turned chaotic. Wartime economics drove excessive competition among Japan’s many shoyu producers, leaving the industry fragmented and the market confused. Against that backdrop, eight leading Mogi and Takanashi family companies in Noda merged to form Noda Shoyu Co., Ltd. in 1917.

It was a defensive move—stability, pricing power, survival. But it was also an offensive one. Consolidation meant scale. And scale meant the ability to invest, standardize, and eventually build something bigger than a collection of local breweries.

The corporate identity would evolve over time: the company name later changed to Kikkoman Shoyu Co. Ltd. in 1964, and then to Kikkoman Corporation in 1980. But the 1917 merger was the moment the centuries-old family trade began turning into a modern enterprise.

And here’s the part that reframes everything: even before that merger, the operation was already enormous. By 1910, the “Kikkoman” firm reportedly owned six soy breweries, employed thousands of workers, and produced about 11,800,000 gallons per year—exporting roughly 2,880,000 gallons abroad, to places like Honolulu and San Francisco, Portland and Seattle, Los Angeles and Chicago, and even London, Paris, Berlin, Vienna, and ports in China.

Sit with that. Before 1917, before the company formally existed, a soy sauce producer from a river town outside Tokyo was already shipping product to major cities across America and Europe.

The global ambition wasn’t a postwar invention. It was there early—baked into the way this business saw the world.

III. The Great Noda Strike and Corporate Identity (1920s–1940s)

The 218-Day Crucible

Every great company has a moment when it stops being just a business and starts becoming a culture. For Kikkoman, that moment wasn’t a product launch or a breakthrough market. It was a labor war.

The Great Noda Shoyu Strike began in September 1926 and dragged on into 1928, pitting management against labor in a public, grinding standoff. It became one of the most written-about labor disputes of its era for a simple reason: it lasted 218 days, the longest strike in Japan prior to World War II. And when it ended, it ended decisively—effectively destroying the union.

That kind of fight leaves a mark. The dispute didn’t just disrupt production; it forced the company to confront what it wanted to be as an employer and as a pillar of its community. The lessons of that period would echo through the decades, shaping how Kikkoman thought about labor relations and local trust—especially later, when it began planting flags abroad and needed communities to see it not as a foreign operator, but as a reliable neighbor.

Brand Consolidation and Identity

While the strike tested Kikkoman’s internal cohesion, the years around it also pushed the company toward a clearer outward identity.

Until 1940, the company operated under the name “Noda Shoyu Corporation.” Then it adopted a single brand name: Kikkoman. It wasn’t just a new label on the bottle. It was the culmination of what the 1917 merger had started—pulling a collection of family-rooted operations into one unified face, one reputation, one promise of quality.

In an increasingly turbulent era for Japan, that unity mattered. A consolidated identity and streamlined operations gave the company a steadier footing as the country moved deeper into the instability of the 1930s and beyond.

The Imperial Connection

And even as Japan changed rapidly, Kikkoman kept one relationship that anchored its brand at the very top of the quality pyramid.

In 1939, the company built the Goyogura, a special facility dedicated exclusively to brewing soy sauce for the Japanese imperial household. Built on the banks of the Edo River, it still produces soy sauce for the imperial family today, using processes handed down through generations.

This wasn’t a marketing gimmick. It was a standard the organization had to live up to—an internal north star. And later, when Kikkoman would ask American and European consumers to trust an unfamiliar seasoning, that relentless quality discipline would become one of its quietest, strongest advantages.

IV. The Post-War Pivot: Seeing America Before America Saw Soy Sauce (1950s–1960s)

The Strategic Insight That Changed Everything

After World War II, Japan was rebuilding from the ground up. Most companies were focused on simply staying alive. Kikkoman, though, noticed something that didn’t show up on any balance sheet.

Occupation forces, journalists, and other foreigners living in Japan were learning to cook and eat Japanese food. And in the process, they were getting used to soy sauce—using it, liking it, and building the habit. Where others saw temporary visitors, Kikkoman saw something much more valuable: future evangelists who would go home and bring that taste with them.

This “outside-in” instinct would later be embodied by Yuzaburo Mogi, a descendant of the founding family. Born in 1935, Mogi earned his B.A. from Keio University in 1958, then went to Columbia Business School for an MBA—becoming, in 1961, the first Japanese national to earn an MBA from Columbia. When he returned to Japan in the 1960s, he argued that if Kikkoman stayed confined to the domestic market, it would eventually hit a ceiling. The company needed to go overseas. In time, he would help persuade management to build a factory in Wisconsin. But the spark—the realization that America could be more than an export destination—started right after the war.

In 1957, Kikkoman made its U.S. move official, setting up a sales and marketing base in San Francisco. The year before, it had already begun planting the idea with newspaper ads in the San Francisco Chronicle, introducing soy sauce to American readers as an “All-Purpose Seasoning.”

That phrase did a lot of work. Instead of asking 1950s America to embrace Japanese cuisine, Kikkoman offered soy sauce as a simple upgrade to the foods Americans already cooked every day.

The "Not Just Asian Food" Strategy

Kikkoman’s bet was straightforward: soy sauce wasn’t delicious because it was Japanese. It was delicious, period.

So if the goal was everyday use—not an occasional splash at a Chinese restaurant—soy sauce couldn’t be framed as a condiment reserved for Japanese dishes. It had to be repositioned as versatile. That’s why Kikkoman labeled its export bottles with “ALL-PURPOSE SEASONING” starting in 1957, an expression that remains on labels to this day. It wasn’t just a slogan; it was a set of instructions for how to think about the product.

Just as important was who Kikkoman didn’t target. The obvious first market was Japanese people living abroad—customers who already knew the brand and already needed soy sauce in their kitchens. But that market was finite. It could never deliver true scale.

Instead, in the 1950s, Mogi helped introduce soy sauce to the American public by hiring chefs to develop recipes that used it, then pushing those recipes to local newspapers—aiming for the most powerful distribution channel of the era: the American home cook clipping ideas from the paper and turning them into grocery lists.

The In-Store Demo Revolution

Then Kikkoman took the pitch out of print and into the aisle.

The company ran in-store cooking demonstrations in supermarkets, offering samples of familiar American foods—seasoned, quietly, with soy sauce. A bite of steak with a deeper, richer savor. Vegetables that tasted suddenly more complete. The point wasn’t to be exotic. It was to be obvious.

If shoppers liked what they tasted, Kikkoman made the next step frictionless. Small recipe booklets attached to bottles showed exactly how to recreate the dishes at home. It was far easier to tweak American recipes than to try to change the American diet.

This grassroots playbook worked because it met consumers where they already were. Kikkoman wasn’t asking Americans to cook Japanese food. It was showing them that soy sauce made their food taste better.

And over time, it stuck. Soy sauce became one of North America’s favorite seasonings, and Kikkoman became the category’s defining brand. Even as the company expanded into many convenient sauces and seasonings, the foundation stayed the same: its core product—traditionally brewed soy sauce—remained unchanged.

V. The Iconic Bottle: When Design Becomes Destiny (1961)

The Kenji Ekuan Story

In 1961, Kikkoman made a decision that looks obvious only in hindsight: it treated the bottle like a product, not an afterthought. And the person they tapped for the job didn’t come out of a packaging department. He came out of Hiroshima’s shadow.

Kenji Ekuan (September 11, 1929 – February 8, 2015) was a Japanese industrial designer, best known for creating the Kikkoman soy sauce bottle. Born in Tokyo, Ekuan spent part of his youth in Hawaii. But it was what he saw as a teenager, in the aftermath of the atomic bombing of Hiroshima—where he lost his sister and his father, a Buddhist priest—that set his life’s direction.

Years later, he told the New York Times that after the war he “needed something to touch, to look at,” and decided he would become “a maker of things.” He briefly trained for the priesthood, following his father’s path, before committing to design instead. Still, the philosophy stayed with him.

“The path of Buddha is the path to salvation for all living things, but I realized that, for me, the path to salvation lay in objects,” Ekuan wrote in a memoir. “Objects have their own world. Making an object means imbuing it with its own spirit.”

That worldview turned out to be perfectly matched to Kikkoman’s problem: how do you turn a humble, messy condiment into something people want to keep on the table?

100 Prototypes to Perfection

At the time, soy sauce often arrived in large containers. In many households, someone—often mom—would pour from a heavy bottle into a tabletop dispenser. It worked, sort of. The catch was the same everywhere: after you poured, the spout kept dripping. Soy sauce would creep down the neck, stain the label, gum up the cap, and leave that familiar sticky ring on the table.

Ekuan remembered that exact ritual from his childhood. And when Kikkoman commissioned him to create a small bottle that could live permanently on the table, he didn’t approach it as “make a nicer container.” The mission was bigger: create something “that would be regarded as essential tableware, in the same category as a plate or teacup, as opposed to producing a mere container.”

He spent more than three years on it. He built over 100 prototypes. And eventually, he landed on the design the world now recognizes instantly: a curved glass bottle with a heavy base for stability, understated lettering, and a delicate neck topped with a red cap engineered to dispense cleanly, without drips.

In 1961, Ekuan delivered the now-famous 150mL Kikkoman soy sauce bottle—built around the idea that “design is a source of life enhancement.” It didn’t just make soy sauce easier to use. It made soy sauce feel at home on any table.

Museum-Worthy Design

Over time, the bottle stopped being “the dispenser” and became the brand.

It won the Lucky Strike Designer Award in 2003. It has been displayed for years at the Museum of Modern Art in New York and at the Design Zentrum Nordrhein-Westfalen in Germany. Its silhouette—rounded shoulders, narrow neck, red cap—became visual shorthand for Kikkoman itself.

Kikkoman kept producing it at massive scale, and it spread through restaurants and kitchens around the world. The tabletop dispenser is used in over one hundred countries, and over the decades it has sold more than 500 million bottles.

Even the smallest details were intentional. The cap has two holes—an elegantly simple feature that lets you control how quickly the soy sauce pours.

This is the rare kind of design that doesn’t just hold a product. It changes the product’s destiny. In an era when most condiments sat anonymously on restaurant tables, Kikkoman’s bottle created instant recognition—brand identity you could pick up with one hand.

VI. Building the Global Production Empire (1970s–2000s)

Wisconsin: The American Heartland Strategy

After fifteen years of building demand through imports, advertising, and supermarket demos, Kikkoman made the move that would lock in its future: it stopped being an exporter and became a local producer.

In 1972, Kikkoman chose the small community of Walworth, Wisconsin as the site of its first U.S. production plant. The criteria were simple and brutally practical: a central location for distribution, a reliable supply of good water, and a hard-working, loyal workforce. Wisconsin checked every box. It also happened to sit near abundant supplies of soybeans and wheat—two of soy sauce’s key ingredients.

The plant began shipping its first “Made in the U.S.A.” Kikkoman Soy Sauce in 1973. And it made history in the process, becoming one of the first production facilities built in the United States by a Japanese company.

If Noda was the perfect river-town launchpad in the 1600s, Walworth was the 20th-century equivalent: access to inputs, clean water, and strong transportation links. The logic was old-school Kikkoman. Pick the right geography, then compound.

Compound it did. Built on what had been a Walworth County farm field, the facility now produces roughly thirty times more product annually than it did when it opened—growth that turned it into the highest-producing soy sauce facility in the world.

Kikkoman also made sure the relationship with Walworth wasn’t transactional. Over the years, it built partnerships and friendships in the community, finding common ground in values like hard work, respect, cooperation, and a commitment to excellence. The company has contributed more than $17 million to charitable causes locally and beyond—reinforcing that it wasn’t just manufacturing in Wisconsin, it was putting down roots.

The European Conquest via Restaurant

Europe got a very different Kikkoman beachhead—and it was classic Kikkoman.

In 1973, the company’s push into the European market began not with a factory or a distribution deal, but with a teppanyaki restaurant: DAITOKAI, in Düsseldorf, Germany.

This was experiential marketing before that term existed. Instead of shipping bottles and hoping consumers would guess how to use them, Kikkoman created a stage. Diners could watch skilled chefs cook on a hot iron plate, smell the aroma as soy sauce hit heat, and taste how it elevated familiar ingredients like beef and vegetables. The product wasn’t explained. It was demonstrated.

As demand grew, Kikkoman followed the same playbook it had used in America: localize production. In 1997, it completed its first European production plant in Sappemeer, in the Netherlands, establishing a base for production and distribution across the continent. Today, that facility produces more than 400 million litres of soy sauce per year.

Asia-Pacific: Expanding the Umbrella

While the U.S. and Europe were coming online, Kikkoman kept building out its footprint across Asia and Oceania.

In 1983, the company established Kikkoman (S) Pte Ltd in Singapore as an export hub for Southeast Asia and Oceania. The following year, the Singapore plant began operating, and Kikkoman started shipping Kikkoman Soy Sauce produced there.

Momentum followed. Year after year, Kikkoman expanded market share across the region, especially in soy sauce and teriyaki sauce. By 1988, its market share in Australia reached 50%—and it continued to grow from there.

Strategic Diversification: Del Monte and Beyond

By the 1990s, Kikkoman was already proving something important: soy sauce could be a global staple. But it also wanted a broader portfolio—products that could ride the same distribution rails while reducing dependence on a single category.

In 1990, Kikkoman acquired the permanent trademark and marketing rights to Del Monte processed foods in Japan and the Asia-Oceania region (excluding the Philippines). It then established sales offices and production bases to develop, produce, and distribute processed vegetable and fruit products tailored to local needs.

The rationale was straightforward: diversify beyond soy sauce, leverage the network Kikkoman had already built, and create a hedge if soy sauce growth ever slowed.

The relationship had deeper roots, too. Kikkoman first met Del Monte in 1963. Del Monte was already a global brand sold in over 80 countries, known for processed fruits and vegetables. Over time, a shared commitment to quality became the foundation for what turned into a long-running alliance.

VII. Recent Inflection Points: The 2010s–2020s Transformation

Global Vision 2030: The Roadmap Forward

By the late 2010s, Kikkoman had done the hard part. It had proven—across decades, continents, and cuisines—that soy sauce could travel.

Now the question shifted from “Can this work outside Japan?” to “How big can this get?”

In April 2018, the company put its answer on paper: Global Vision 2030, a long-term plan built around Kikkoman’s management principles and a simple theme—“Striving with passion to create new values.” The core ambition was even simpler: make Kikkoman Soy Sauce a truly global seasoning.

The template is North America. That’s the market where soy sauce went from “something you get in a takeout bag” to a pantry staple—and where Kikkoman has become the No.1 brand in the home-use soy sauce category. Global Vision 2030 is about repeating that outcome elsewhere: Europe, Asia, and the next wave of growth markets. And it’s not just about the classic bottle. Kikkoman has also been leaning into soy sauce-based cooking sauces—especially teriyaki—using brand strength to expand into adjacent, everyday use cases.

Sustainability Commitments

Alongside growth, Kikkoman also started putting harder stakes in the ground on sustainability.

By 2030, the company aims to cut global CO2 emissions by more than half (compared with fiscal 2019 levels) and reduce water consumption per unit of production by more than 30%. It’s also aiming for a recycling rate of 100%. Longer-term, the Group is targeting net zero CO2 emissions by 2050.

This isn’t entirely new territory for the company. Back in 2001, Kikkoman became the first Japanese company to sign the United Nations Global Compact. But in the 2010s and 2020s, these commitments moved from “values statements” into concrete operational targets—especially relevant for a business whose signature product depends on water, agriculture, and time.

South America Entry: Brazil as the 8th Overseas Production Hub

If you want a snapshot of modern Kikkoman’s playbook, look at Brazil.

In 2018, the company began contract production and sales of soy sauce-based seasonings designed specifically for South American tastes. In 2020, it established a local corporation dedicated to producing and marketing its products—an unmistakable signal that this wasn’t an experiment anymore. Then, in the following year, Kikkoman began distributing soy sauce produced in Brazil, making it the company’s 8th overseas production hub.

In November 2021, Kikkoman celebrated the start of production and shipment of Kikkoman Soy Sauce at its Campinas plant in São Paulo.

Brazil is the economic giant of South America, but it’s also a country with a deep-rooted connection to Japanese immigration—and, with it, to soy sauce. Kikkoman wasn’t introducing a totally foreign flavor. It was stepping into an existing relationship and scaling it with local production and local products.

The $800 Million Wisconsin Expansion (2024)

Then came the announcement that surprised no one who’s been paying attention: Kikkoman doubled down on America—again.

In 2024, the company announced it would invest at least $800 million to build a new production facility in Jefferson, Wisconsin, plus expansion initiatives at its long-running Walworth plant. Together, the projects are expected to create 83 new jobs over 12 years. After considering dozens of Midwestern sites, Kikkoman ultimately chose Jefferson—about 60 kilometers, or 37 miles, north of Walworth.

The logic sounds familiar because it’s the same logic that brought Kikkoman to Walworth in 1972: strong access to markets, a highly regarded workforce, proximity to soybeans and wheat, and plenty of pure, high-quality water.

The new facility is planned as a 240,000-square-foot plant, with construction beginning in April 2024 and shipments targeted to start in Fall 2026. Once complete, it will be Kikkoman’s third U.S. plant—after Walworth (shipments beginning in 1973) and its California plant (shipments beginning in 1998)—and the Group’s ninth overseas soy sauce production site.

On June 12, 2024, Kikkoman marked the start with a groundbreaking ceremony in Jefferson, complete with the thunder of taiko drums and a traditional Shinto ceremony. The plant will sit on a 100-acre lot within what’s planned as a 200-acre Food and Beverage Innovation Campus. Kikkoman described it as a fully integrated, highly automated, state-of-the-art operation designed for flexibility and scalability—able to run smaller or larger batches as needed. The company also tied the facility to its sustainability agenda, citing plans to reduce CO2 emissions through energy-efficient equipment and waste reduction.

Chairman Yuzaburo Mogi greeted guests with the kind of remark that only lands when you’ve actually been there for half a century of the story: “I’m always delighted to come back to Wisconsin. I considered it my second home.” He recalled the excitement and goodwill of the Walworth groundbreaking more than 50 years earlier—this time with a new generation building the next chapter.

Soy Milk and Domestic Diversification

While the global soy sauce machine kept expanding, Kikkoman also continued broadening its base at home—especially in beverages.

Kikkoman Soymilk is the leading soymilk brand in Japan, and the company entered the category in 2004 through a business alliance with Kibun Foods Inc. The strategic fit was clear: soymilk and Del Monte’s tomato beverage both sit in the world of health-conscious drinks, and Kikkoman saw synergy in building a stronger beverage division.

In 2008, Kibun Food Chemifa Co., Ltd., a subsidiary of Kibun Foods Inc., became a wholly owned subsidiary of Kikkoman. The transition into the Kikkoman brand happened carefully. The “Kikkoman” logo was added to packaging in 2011, followed by a gradual packaging renewal in 2015, with products increasingly sold under the Kikkoman name—intentionally paced to avoid confusing consumers.

Today, the soymilk lineup includes roughly 40 products. Kikkoman has said it will keep expanding its plant-based milk range, using the breadth of the brand and its fermentation know-how to develop new offerings.

VIII. The Product & Process: Why "Honjozo" Matters

Traditional Brewing vs. Chemical Hydrolysis

For all the marketing, globalization, and beautiful bottle design, the real moat at Kikkoman is almost stubbornly simple: time.

Kikkoman’s soy sauce is made by traditional natural brewing, a method that takes about six months for fermentation to do its work. It starts with soybeans soaked in water, then steamed at high temperatures. Those soybeans are combined with crushed, roasted wheat. Salt is added—not just for taste, but as an anti-bacterial agent and preservative.

In Japanese, this traditional brewing method is called honjozo. And it matters because fermentation creates complexity you can’t fake. Many non-brewed, “chemically produced” soy sauces take a faster route: acid hydrolysis. That process finishes in days, not months.

The difference shows up in the end product. Traditional brewing develops hundreds of distinct flavor and aroma compounds. Chemically hydrolyzed soy sauce doesn’t. It tends to taste harsh, aggressively salty, and one-dimensional—more likely to overpower a dish than to deepen it.

This is why Kikkoman hasn’t compromised on how it makes soy sauce, even as it scaled across continents. Whether the plant is in Wisconsin, the Netherlands, or Singapore, the company uses the same honjozo approach that has defined Kikkoman for centuries.

Our core product—traditionally brewed soy sauce—has remained unchanged. It’s still made from water, soybeans, wheat, and salt, then aged slowly for full flavor, like a fine wine. The world around Kikkoman transformed. The process in the tank didn’t.

IX. Competitive Analysis and Investment Framework

Porter's Five Forces Analysis

Threat of New Entrants: LOW

On paper, soy sauce looks like a category anyone can enter. In reality, entering the premium end of the market is brutal.

Kikkoman isn’t just selling a salty brown liquid. It’s selling consistency, trust, and a flavor profile that comes from a process that refuses to be rushed. Traditional brewing takes about six months, which means new entrants don’t just need a factory—they need the balance sheet and patience to carry huge fermentation capacity before the first meaningful dollar comes back.

And even if you solve the manufacturing problem, you hit the harder wall: reputation. Kikkoman has centuries of heritage, a global footprint, and an instantly recognizable tabletop bottle that doubles as advertising. Those aren’t assets you can buy quickly.

The barriers stack up fast:

- Traditional brewing ties up capital for months at a time, forcing massive capacity up front

- Centuries of brand credibility that can’t be replicated on a startup timeline

- A global distribution network, supported by production across multiple regions

- Packaging and design that act as automatic brand recognition, everywhere the bottle sits

Bargaining Power of Suppliers: LOW TO MODERATE

Soybeans and wheat are commodities, with many sources around the world. That keeps supplier power contained. Kikkoman’s additional advantage is geography: with production spread across the Americas, Europe, and Asia, it’s less exposed to a single region’s crop issues, logistics shocks, or price spikes.

Bargaining Power of Buyers: MODERATE

Restaurants and food service buyers can switch brands, and many do shop on price. But Kikkoman has an unusual advantage for a commodity category: consumers often ask for it by name. That creates real leverage in retail, and it helps in food service too—because the brand on the table matters.

Kikkoman also sells through both retail and food service, which reduces dependence on any single buyer group and keeps negotiating dynamics more balanced.

Threat of Substitutes: LOW TO MODERATE

If what you want is umami, there are alternatives: MSG, fish sauce, and other flavor boosters. But soy sauce has a distinctive taste and versatility that’s hard to swap out cleanly. And as more consumers gravitate toward naturally fermented products over “additive” shortcuts, Kikkoman’s traditional positioning becomes an advantage rather than a cost burden.

Competitive Rivalry: MODERATE

The soy sauce market is crowded, and the biggest players include Foshan Haitian Flavoring & Food Co. Ltd., Kikkoman, Lee Kum Kee, YAMASA Corporation, and SEMPIO FOODS COMPANY. Even so, it’s still fragmented—the top five together account for under a fifth of global share.

The broader category is also growing. Estimates put the global soy sauce market at about USD 56 billion in 2024, projected to reach roughly USD 76 billion by 2030.

Hamilton Helmer's 7 Powers Analysis

Brand: This is the anchor. Kikkoman’s hexagonal tortoise-shell logo is one of the world’s oldest trademarks still in continuous use. In the U.S. home-use market, “Kikkoman” often is soy sauce, and that mental default shows up as pricing power and premium shelf placement.

Scale Economies: Walworth is the highest-producing soy sauce facility in the world, and the Jefferson buildout extends that advantage. In a business where time is literally an ingredient, scale isn’t just about cost—it’s about having enough fermentation capacity to meet demand without compromising the process.

Switching Costs: For consumers, switching is easy. For food service operators, it’s less so. Once recipes and kitchen routines are calibrated to Kikkoman’s flavor, changing brands can mean changing the dish.

Network Effects: Traditional network effects are limited here. But Kikkoman’s recipe development, cooking education, and content libraries create a lightweight ecosystem: people learn to cook with it, then keep buying the same bottle to reproduce what they learned.

Counter-Positioning: Kikkoman’s six-month brewing process is a strategic commitment. Many mass-market competitors can’t match it without breaking their own cost structures.

Cornered Resource: Fermentation know-how is real know-how. Kikkoman’s accumulated expertise—built over centuries—functions like a specialized resource that isn’t easily purchased or copied.

Process Power: Kikkoman’s ability to produce consistent quality across global facilities is its own advantage. Scaling a fermentation process without losing the signature flavor is hard, and Kikkoman has decades of reps doing exactly that.

Competitive Positioning

Pricing tells you a lot about how consumers perceive value.

In China, Haitian’s soy sauce often sells for roughly 10 to 12 yuan per liter, versus about 30 yuan per liter for Japan’s Kikkoman. That’s a meaningful premium in a category that’s supposed to be price-competitive—and it’s the clearest proof that Kikkoman’s brand and quality positioning translate into willingness to pay.

And the strategy behind that premium is the same one Kikkoman leaned into in America decades ago: don’t sell only to Japanese consumers abroad. Build the non-Japanese household.

Yuzaburo Mogi has said that around 50% of profit comes from U.S. sales, and about 70% of profit comes from overseas sales overall. The globalization bet didn’t just work. It became the profit engine.

Financial Performance Overview

Kikkoman was established in 1917, and as of FY2025 it reported revenue of 709.0 billion yen and business profit of 77.3 billion yen, with 56 group companies and 7,716 employees (3,145 in Japan and 3,958 overseas).

In the quarter ending December 31, 2024, Kikkoman reported revenue of 179.95 billion yen, up 4.53%. Over the last twelve months, revenue reached 701.48 billion yen, up 8.35% year-over-year.

Management attributed organic profit growth to improving margins in overseas markets during the fourth quarter, which more than offset margin pressure in Japan.

For FY2024, revenue was 660,835 million yen and business profit was 73,402 million yen. Regionally, North America was the largest contributor, with Europe and Asia/Oceania also meaningful, while Japan remained a major, but comparatively smaller, piece of the overall mix.

X. Bull and Bear Cases

The Bull Case

1. Secular Tailwinds for Asian Cuisine

Asian cuisine keeps moving from “special occasion” to “weeknight default” around the world. As younger consumers grow up treating soy sauce like a basic pantry item—something you reach for automatically, not something you buy for one specific dish—Kikkoman’s market expands without the company having to convince people what soy sauce is.

2. Premium Positioning in a Commoditizing World

Soy sauce is easy to imitate at the low end. It’s much harder to earn trust at the high end.

As food production industrializes, naturally brewed products with clear provenance can command a premium. Kikkoman’s willingness to keep the slow, six-month fermentation process isn’t just tradition—it’s positioning. In a category full of shortcuts, “we don’t rush this” becomes the brand.

3. Underexploited Markets

Even after decades of globalization, there are still huge white spaces on the map. South America, India, and parts of Africa represent meaningful runway. Brazil is still early. India, in particular, remains largely untapped.

In February 2024, Kikkoman announced a new dark soy sauce developed specifically for the Indian market. The company framed it as a milestone in its roughly 350-year history: a naturally crafted sauce designed to deliver rich color without chemicals, preservatives, or artificial seasonings. After four years of research and development, Kikkoman said it had created a proprietary method aimed at Indian consumers who want visually appealing Chinese and Pan-Asian dishes—without compromising on the “naturally brewed” story.

4. Plant-Based and Health Trends

Kikkoman has been diversifying and pushing further overseas as Japan’s population shrinks and per-capita soy sauce consumption declines. That shift lines up well with broader consumer trends: more interest in health, more plant-based options, and more “better ingredient” scrutiny.

Soy milk, health-oriented product lines, and gluten-free offerings all sit in the slipstream of that movement—and give Kikkoman more ways to grow than simply selling more of the classic bottle.

5. Operational Excellence and Capacity Expansion

The company’s at-least-$800 million U.S. expansion is a loud signal: management expects demand to keep rising. New, highly automated facilities can improve efficiency and support sustainability goals, while also adding capacity in the market that has become Kikkoman’s profit engine.

The Bear Case

1. Japan Demographic Headwinds

Japan’s domestic market faces long-term pressure from an aging, shrinking population. Overseas growth has more than offset that so far, but Japan still contributes meaningful revenue—and slow domestic drift can weigh on the overall picture.

2. Currency Volatility

With more than 70% of profits coming from overseas operations, exchange rates matter. A weaker yen can flatter results; a stronger yen can do the opposite. Either way, it adds noise—and sometimes pain—to reported earnings.

3. Commodity Price Exposure

Soybeans and wheat are global commodities, and their prices swing. Kikkoman has navigated these cycles historically, but sustained input cost inflation can squeeze margins, especially when consumers and food service buyers resist price increases.

4. Competitive Intensity in China

China is a brutal market: huge volume, strong domestic brands, and intense price competition. Players include Foshan Haitian Flavouring & Food Co. Ltd and Jiajia Food Group Co., Ltd., alongside Kikkoman. Asia Pacific accounted for 61.86% of the global soy sauce market in 2024, and China is a major driver of that dominance.

Haitian, in particular, leads China’s domestic market at significantly lower price points. Kikkoman can hold a premium niche, but Chinese competitors have cost advantages—and if they expand globally, that could raise the competitive temperature in Kikkoman’s growth markets.

5. Premium Valuation

Kikkoman has often traded at premium multiples, reflecting confidence in the brand, the process, and long-term execution. The risk is straightforward: when expectations are high, even small stumbles can lead to multiple compression.

XI. Key Performance Indicators to Track

If you want a simple dashboard for whether the Kikkoman story is still compounding, three metrics do most of the work:

1. Overseas Soy Sauce Sales Volume Growth (Excluding Currency Effects)

This is the cleanest read on real demand. Kikkoman reports growth in local terms so you can see what’s happening underneath the currency swings. If overseas volume keeps growing at a healthy clip, the core thesis—that soy sauce can keep becoming a default seasoning outside Japan—remains intact.

2. Business Profit Margin

Growth is good. Profitable growth is the whole game.

In FY2025, Kikkoman reported revenue of 708,979 million yen and business profit of 77,275 million yen, a business profit ratio of 10.9%. For FY2026, the company forecast revenue of 744,500 million yen and business profit of 77,600 million yen, implying a ratio of 10.4%.

This margin line (revenue minus cost of sales minus SG&A) is where you see whether scale is actually turning into operating leverage. As new capacity comes online and the production network keeps modernizing, this is the place to watch for efficiency gains—or for input costs and competitive pressure showing up.

3. North American Market Share

North America is Kikkoman’s profit engine, so this is the “don’t break the flywheel” metric.

Kikkoman already dominates the home-use soy sauce category in the U.S. The question now is extension: can it keep defending that core position while pulling more of the American pantry into the brand through adjacent products like teriyaki sauce and other cooking sauces? Household penetration and share trends here are the clearest signal of whether Kikkoman’s moat in its most important market is widening—or slowly narrowing.

XII. Conclusion: The Next 400 Years

Kikkoman’s story is, at its core, a story about patience—one of the most underrated competitive advantages in business. Not patience as a slogan, but patience as an operating system: slow fermentation, slow brand-building, and slow, deliberate expansion that compounds over generations.

Yuzaburo Mogi once put the company’s modern footprint in human terms: “In the past few years, we marked the 50th anniversary of that first plant in the U.S., the 40th anniversary of our Singapore facility, and the 25th anniversaries of both our European and California plants.” Add it up and the picture is clear. Kikkoman built eight overseas production plants—and started a ninth. And the twist is that the newest facility isn’t halfway around the world. It’s only a few dozen miles from where Kikkoman first put down American roots in Wisconsin.

That choice tells you a lot about how this company thinks. “We always look to hedge risk,” Mogi says. “Building in diverse places can reduce risk, but it also increases costs. We would need new suppliers and supply routes, new business partners, and a new workforce in an area where we have no established presence.”

So instead of chasing novelty for novelty’s sake, Kikkoman did something more consistent with its DNA: it deepened. It expanded close to where it already knew the water, the workforce, the suppliers, and the community. Growth not by constantly hopping to the next frontier, but by building durability where trust already exists.

At the 2024 groundbreaking, Chairman Mogi framed it as a continuation of a relationship, not a construction project. “Today, we are committing to an investment in the community of Jefferson and the state of Wisconsin,” he said. “Kikkoman believes in Wisconsin, and we are grateful to this great state for believing in us. Our collaboration began half a century ago as a leap of faith, and today, it continues as a promise of continued growth and cultural connection.”

That arc—from leap of faith to long-term partnership—captures what Kikkoman has done better than almost anyone. In a world trained to optimize for the next quarter, Kikkoman plans in decades and executes in centuries.

More than fifty years after its first U.S. plant began shipping, soy sauce has become a staple in almost half of American households, and Kikkoman ships to more than 100 nations worldwide. As the company itself has said, it has always valued Walworth for “great market access, outstanding workforce, central location for raw materials, pure water, and the open-hearted spirit of partnership of the local community.”

The tortoise in the logo, it turns out, was never just symbolism. It was the strategy: steady progress, relentlessly compounding, toward a destination that takes a very long time to reach—and once reached, becomes part of everyday life.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music