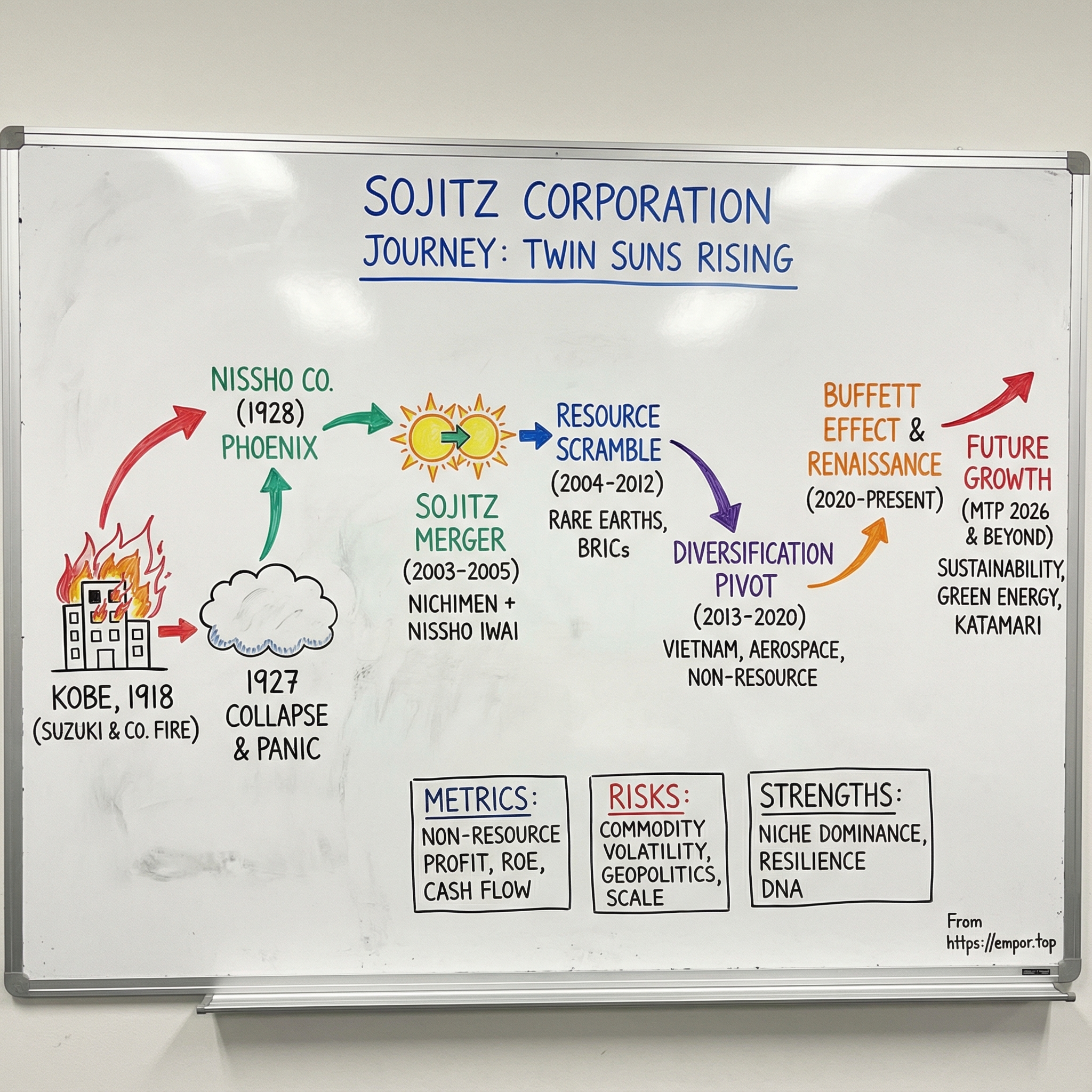

Sojitz Corporation: Twin Suns Rising from the Ashes

I. Introduction: The Ghost of Kobe

In the sweltering August heat of 1918, a burned-out shell of a building sits blackened in Kobe.

Days earlier, it was the headquarters of Suzuki & Co., the largest trading company in Japan—so large its sales amounted to roughly a tenth of the country’s entire economy. Now it’s still smoldering, torched by an angry crowd convinced Suzuki was hoarding rice while ordinary people went hungry.

Somewhere behind the scenes stands the company’s owner: Yone Suzuki, a 66-year-old widow once described as the richest woman in the world, watching the first visible crack in what had seemed like an untouchable empire.

Nine years later, that empire didn’t just stumble. It collapsed—and the shockwave hit all of Japan. A financial panic erupted. In the ensuing bank run, 37 banks across the country went under, including the Bank of Taiwan. Suzuki Shoten, a second-tier zaibatsu by that point, went down with them. Prime Minister Wakatsuki Reijirō tried to push through an emergency decree so the Bank of Japan could extend rescue loans, but the Privy Council refused. He resigned.

Most companies don’t come back from that. This story does.

Out of the wreckage, survivors regrouped. They rebuilt. And, decades later, those rebuilt businesses would combine with the descendants of two other Meiji-era trading houses. In April 2003, Nichimen Corporation and Nissho Iwai Corporation set up a joint holding company. The following year, they integrated their operations and became the Sojitz Group.

That company is Sojitz Corporation, ticker 2768 on the Tokyo Stock Exchange—born from the union of Nichimen and Nissho Iwai, and carrying more than 160 years of history through its predecessor companies. It’s a modern Japanese general trading company with a footprint that reaches far beyond Japan.

Even the name is a clue to the origin story. “Sojitz” comes from the two companies it merged—each written with the character 日, “sun.” Put them together and you get “twin suns,” a deliberate signal that this was meant to be a merger of equals.

This is a story about resurrection—about what happens when a business survives catastrophic failure not once, but repeatedly. It’s also a story about a business model that’s uniquely Japanese: the sogo shosha, the general trading company. And it’s about how a scrappier, seventh-place player—living in the shadow of giants like Mitsubishi and Mitsui—worked to carve out an identity of its own.

The question that pulls the whole thing forward is simple: how did a company born from spectacular collapse become a global enterprise operating across fifty countries, with revenue of more than 2.5 trillion yen and net profit of 110 billion yen in fiscal year 2024?

II. The Sogo Shosha Model: Japan's Hidden Champions

Before we go any further into Sojitz’s origin story, we need to understand the world it lives in. Because sogo shosha aren’t Western-style conglomerates. They aren’t pure commodity traders in the Glencore-or-Trafigura mold, either. They’re something distinctly Japanese—and once you see the model clearly, Sojitz’s role in the ecosystem makes a lot more sense.

A sogo shosha, literally a “general trading company,” is a wholesale and investment platform that touches a huge range of products and materials. Yes, it buys and sells. But it also arranges shipping and logistics, provides financing, helps build industrial plants, and takes stakes in projects and companies. Where trading houses elsewhere tend to specialize, sogo shosha are defined by diversification. They operate across resources, food, energy, machinery, chemicals, infrastructure, and increasingly, digital businesses too.

There’s a phrase in Japan that captures the scope: “from ramen to rockets.” It’s not poetic license—it’s an accurate shorthand for how broad these companies’ reach can be.

So why did this model emerge in Japan, and not really anywhere else? Japan had a unique set of constraints that made the “do-everything trading company” unusually valuable. The country’s geographic distance from major markets, plus language and cultural barriers, raised the cost of information and negotiation. And after more than two centuries of isolation, Japan had to build modern trade networks fast—far faster than Europe, where commercial relationships had evolved over a much longer period.

In that environment, scale and breadth become an advantage. By operating in many markets at once, sogo shosha can spread risk, hold balances across multiple currencies, and create internal supply and demand across their own businesses. Their size supports large in-house information networks that spot opportunities earlier, and their balance sheets let them provide credit and financing—sometimes as important as the goods themselves.

Zoom out, and you see why Japan kept them. These trading companies help supply the Japanese economy with the resources it needs and help move Japanese products out to the world. Japan is resource-scarce but industrially sophisticated, so the ability to reliably source, finance, and deliver materials at scale is strategic. Individually, you might not describe each company as having a single “secret sauce.” Collectively, they’ve become the infrastructure layer under Japan’s trade.

Today, the landscape is dominated by the so-called “Big Five”—Mitsubishi, Mitsui & Co., Itochu, Sumitomo, and Marubeni. Add Toyota Tsusho and Sojitz and you get the “Big Seven” sogo shosha.

And this isn’t some niche corner of Japanese business. Together, the group represents well over $200 billion in market capitalization and around $30 billion in combined net profit. Within that, the top three—Mitsubishi, Mitsui, and Itochu—sit in a different weight class.

Sojitz, by market cap, is the smallest of the seven. But smaller doesn’t automatically mean weaker. It can mean nimbler. It can mean willing to go where the giants won’t bother. And in Sojitz’s case, it also means something else: the company carries the instincts of an organization that has had to fight to exist—because, as you’ve already seen, it comes from a lineage that has nearly died more than once.

III. The Three Founding Houses: Origins in Meiji Japan (1862-1918)

Sojitz doesn’t start as a single company. It starts as three separate trading houses, born in the decades after the Meiji Restoration—when Japan was racing to industrialize, plug into global commerce, and prove it could stand shoulder to shoulder with the West.

Each predecessor had its own personality. Together, they formed the DNA that Sojitz would eventually inherit: supply-chain muscle, an instinct for manufacturing, and a talent for building empires fast.

Japan Cotton Trading Co. (1892): Building the Manchester of the Orient

In the late 1870s, Japan’s government pushed cotton spinning as a cornerstone of early industrial development. It was a practical bet: textiles were one of the few sectors where Japan could scale quickly and compete internationally.

There was a problem, though. Japan didn’t grow enough raw cotton to feed its mills. Worse, the country relied heavily on foreign merchants for imports, and at the time there was only one Japanese importer of raw cotton. That kind of bottleneck was a strategic vulnerability.

So in 1892, a group of spinning companies in Osaka created Japan Cotton Trading Co., Ltd. under the leadership of Tsuneki Sano, a 38-year-old former government official. The mission was straightforward: secure raw cotton from abroad so Japan’s mills could run, grow, and eventually dominate.

Japan Cotton Trading sourced from places like India, China, Egypt, and the United States—and helped turn Osaka into the industrial boomtown that earned the nickname “the Manchester of the Orient.”

Iwai & Co. (1896): The Industrialist’s Vision

In 1896, Iwai Katsujiro established Iwai & Company in Osaka, starting as a trader of foreign goods.

But Iwai wasn’t content to simply import and resell. He spent time in Kobe’s foreign settlement—one of the few places where international trade was permitted—and came away with a conviction that would shape his company: Japan needed to learn to make at home what it was buying from abroad.

He put that belief into action by drawing up plans for domestic production and helping establish a group of manufacturing companies called Saishokai—firms that later evolved into names like TOABO, Nippon Steel, Daicel, Tokuyama, Kansai Paint, and Japan Bridge.

This is a pattern you’ll see again and again in the sogo shosha world. The trading house isn’t just a broker. It’s an organizer of capital and capability—a builder of industry.

Suzuki & Co. (1874): The Most Dramatic Story

Of the three, Suzuki & Co. is the one that reads like a screenplay.

Suzuki & Co., Ltd. was founded in 1874 by Iwajiro Suzuki as a trading house for Western sugar. It grew into one of Kobe’s eight major trading companies, specializing in sugar and oil.

Then, in 1894, Iwajiro died suddenly—and the story pivoted. Control of the firm passed to his widow, Yone Suzuki, who entrusted day-to-day management to senior clerks Fujimatsu Yanagida and, most importantly, Naokichi Kaneko.

What followed was one of the most remarkable runs in Japanese business history. Yone, a widow raising two sons, became the owner of an expanding commercial machine. Kaneko became its strategist and engine. In 1900, Yone made a fortune in a deal involving sugar, real estate, and camphor, and the company began to compound—fast.

Suzuki moved beyond trading into building. It started a peppermint factory. It bought the Kobe Steel Works. It expanded into camphor manufacturing, sugar refineries, and flour mills. It built factories producing fish oil and bean oil, assembled a fleet of ships, and opened offices across Europe, North America, Australia, and Asia.

By 1918, Yone Suzuki was described as “the wealthiest woman in Japan.” By 1927, she would be called the “richest woman in the world.”

Under Kaneko’s aggressive management, Suzuki didn’t just trade—it incubated and launched businesses at a furious pace, establishing as many as eighty enterprises. Yone, the corporate owner, was known as “O-Ie-san.” Kaneko earned the nickname “the Napoleon of the business world.” And Seiichi Takahata was said to be “like a kaiser-turned-merchant.”

The roster of companies connected to Suzuki during this era reads like a roll call of modern Japanese industry: Kobe Steel, Teijin, IHI Corporation, Sapporo Breweries, Nippon Flour Mills, Daicel, Showa Shell Sekiyu, and portions of what became Mitsui Chemicals and Mitsui O.S.K. Lines.

By 1917, Suzuki hit a peak that’s hard to wrap your head around: at one point, its sales were roughly 10 percent of Japan’s GNP.

Ten percent—through a single trading company.

But this is the kind of scale that attracts enemies, magnifies mistakes, and turns small cracks into fatal ones. And by the time Suzuki looked unstoppable, the seeds of its destruction were already in the ground.

IV. The Spectacular Rise and Catastrophic Fall of Suzuki & Co. (1914-1927)

World War I created a once-in-a-generation opening for Japan. With European industry consumed by war production, global buyers looked elsewhere for manufactured goods. Japanese exports surged, and trading houses like Suzuki didn’t just benefit—they became the connective tissue of the boom.

But Suzuki’s ascent carried a shadow. Yone Suzuki was celebrated for her wealth and feared for the power behind it, and she was also described as “one of the best-hated persons in the country” for taking advantage of wartime conditions and for driving up the price of rice.

In the summer of 1918, that resentment finally found a spark.

The Terauchi cabinet tried to stabilize rice supply by involving major trading companies like Suzuki Shōten in import programs. Instead of building trust, it intensified public suspicion—rumors of cozy relationships between government, speculators, and big merchants. Then a nationwide survey of rice reserves in July backfired. The government didn’t release the results, which only amplified fears of shortages. Speculators piled in. Prices rose further. And the public’s anger boiled over.

The Rice Riots of 1918 weren’t a single protest—they were a wave. From July through September, disturbances spread from a small fishing town in Toyama Prefecture to nearly 500 locations across the country. An estimated one to two million people took part. It became the largest, most widespread, and most violent popular uprising in modern Japanese history.

Kobe was one of the flashpoints. Communications Minister Den Kenjirō wrote in his diary that on August 12 a “Rice Riot” broke out in the city, and that the headquarters of Suzuki and the Kobe Shinbun were set ablaze.

Even the country’s biggest summer sporting event couldn’t escape the chaos. A torching incident at Suzuki & Co., near Naruo Stadium, coincided with a sharp deterioration in public security, and the national junior-high school baseball tournament scheduled for August 14 was postponed.

The image was unforgettable: the most powerful trading company in Japan, its offices reduced to ash by citizens who believed it had profited from their hunger.

Suzuki survived the fire. But it never fully escaped what the fire represented.

The postwar years brought a different kind of threat—less visible than a mob, but far more lethal. Suzuki was badly affected by a foreign exchange crisis in 1923–1924, and it ultimately failed in the financial panic of 1927. The Great Kantō earthquake of 1923, dysfunctional internal dynamics, unpopular business practices, and rivalry with other conglomerates all fed into the unraveling.

The earthquake mattered not just for the destruction it caused, but for what it did to the financial system. Emergency measures to support banks created an accumulating pile of “earthquake bills” and obligations that couldn’t be neatly resolved. And no company was more entangled than Suzuki.

By the end of 1926, the Bank of Taiwan and Suzuki Shoten accounted for 48.4 percent of the “earthquake bill problem.” Yet from the inside, there was little sense of imminent disaster. Management at both Suzuki and the Bank of Taiwan treated their position as systemically important—so important that failure felt impossible.

“The idea that the government would give up on the Bank of Taiwan and Suzuki Shoten was unthinkable. It was a dreadful misapprehension.”

In January 1927, the situation snapped into a new phase. Government actions around redeeming earthquake bonds triggered rumors that banks holding those bonds would collapse. Depositors ran for the exits. In the ensuing bank run, 37 banks across Japan went under—including the Bank of Taiwan—and the second-tier zaibatsu Suzuki Shoten went down with them.

Then came the decision that sealed the outcome. On March 26, 1927, after pressure from officials, the Bank of Taiwan refused Suzuki further lending.

Less than a month later, the crisis turned from panic into paralysis. On April 18, 1927, the Bank of Taiwan was forced to close its doors. The Ōmi Bank shut down the same day. Other banks tried to reassure customers by visibly stacking currency at teller windows. It didn’t work.

It wasn’t even the first panic of the year. It was the third. But it was by far the worst—and this time, it toppled politics along with finance. The Wakatsuki Cabinet resigned on April 20, 1927.

One company’s collapse had helped bring down a government.

For Japanese business, the warning was brutal and clear: grow too fast, bind yourself too tightly to one bank, and torch your reputation at your peril.

Yone Suzuki, once living in a mansion in Suma-ku, Kobe, moved into more frugal conditions after the collapse. She lived another eleven years, dying in 1938.

Her empire was gone. And yet—this is where the story makes its first redemptive turn.

V. Phoenix from the Ashes: Nissho Company is Born (1928-1968)

In the aftermath of Suzuki & Co.’s bankruptcy, the story doesn’t end with ruins and regret. It continues with the people who made it out.

A small circle of survivors regrouped. Two former Suzuki men—Seiichi Takahata and Kotaro Nagai—founded a new company: Nissho Company.

They carried forward the lessons Suzuki had learned the hard way: don’t tie your fate to a single bank, guard your reputation like an asset, and never let expansion outrun risk control. Those instincts became the foundation of Nissho’s culture for decades to come.

At the same time, the other branches of Sojitz’s family tree kept growing on their own. Iwai & Company continued operating independently. Nichimen—the successor to Japan Cotton Trading—did too. And then the world turned upside down again.

After World War II, foreign trade was briefly suspended and the American occupation dismantled the zaibatsu, forcing restructuring across Japanese industry. The great trading arms of Mitsui and Mitsubishi were broken into over a hundred smaller businesses. When trade resumed in 1950, a new generation of diversified trading companies emerged—many of them Kansai-based textile and steel traders that began widening their scope, line by line, into something closer to the modern sogo shosha model.

Then, in 1968, two survivors became one.

Nissho Iwai was formed through the merger of Nissho Company and Iwai Sangyo Company. The combined firm quickly developed a reputation as aggressive and entrepreneurial—exactly the kind of house that would make a seemingly small decision, and then watch it echo for decades.

One of those decisions came in 1971.

The Nike Connection: A Footnote That Became History

In 1971, Nissho Iwai began trading shoes with Blue Ribbon Sports (BRS), the company that later became Nike—and it would later establish NIKE Japan. This fit Nissho Iwai’s broader profile: its food and commodities business held a leading share in imports of staples like wheat and sugar, along with products like fishery goods, timber, and tobacco.

But the Nike connection matters for a different reason. It shows how a sogo shosha can act as more than a middleman—how it can become the financing and connective tissue that turns an idea into an industry.

At the time, BRS was trying to break away and manufacture its own products, overseas, through independent contractors, and import them to the United States. Using financing from Nissho Iwai, BRS could finally do it. This was the moment the company introduced its Swoosh trademark and the Nike brand name.

There’s also a telling detail about how these relationships form. Nissho had approached Onitsuka to try to get the arrangement approved. Onitsuka refused. For Nissho, the rejection was embarrassing—and it helped push them to back BRS more directly.

Nissho Iwai connected BRS with Japanese factories capable of producing the new sneakers, and provided the credit needed to scale. Even years later, Nike didn’t completely bury that origin story. Tucked into its Oregon headquarters is a small Japanese garden, a quiet nod to the relationship: the Nissho Iwai Garden.

That story encapsulates what Nissho Iwai—and later Sojitz—would try to be at its best: spotting opportunities others missed, stepping in with financing when traditional channels wouldn’t, linking entrepreneurs to manufacturing capacity, and building relationships designed to last.

And Nissho Iwai was doing this kind of long-game relationship-building elsewhere, too. It helped pioneer Japan’s commercial footprint in Vietnam. In 1986, it opened a liaison office there—the first for a Japanese company. It participated in the country’s first crude oil export and pursued projects ranging from afforestation to fertilizer. Over time, Vietnam became one of Nissho Iwai’s strongest overseas bases.

VI. The Second Merger: From Survival to Sojitz (2003-2005)

By the late 1990s, Japan’s sogo shosha were under pressure in a way they hadn’t been in decades. The bubble had burst. The Asian financial crisis had rippled through the region. And “global standards” in capital markets and corporate governance were starting to bite.

The old game had been about scale: be everywhere, trade everything, grow bigger. Now the market demanded efficiency. Trading houses sold assets, tightened portfolios, and started looking for partners. For the mid-tier firms, it wasn’t a strategy trend. It was a survival plan.

Nissho Iwai and Nichimen felt that squeeze acutely. The giants—Mitsubishi, Mitsui, Itochu, Sumitomo, Marubeni—had the balance sheets and breadth to absorb a lost decade. Smaller players didn’t. The choice was blunt: merge, or slowly lose relevance.

As the 1990s turned into the 2000s, consolidation swept the sector. A wave of mergers and reorganizations shrank the field until there were, effectively, seven major sogo shosha left standing.

Nichimen, like much of the industry, had been hit hard after the asset bubble collapsed. It responded by shifting its center of gravity away from “soft” trading businesses like lumber, food, and chemicals, and toward “hard” domains—machinery, steel, and construction—where scale, project capabilities, and financing mattered more.

Meanwhile, Nissho Iwai and Nichimen were already learning how to work together. They began integrating a wide range of overlapping operations—information and communications, building materials, synthetic resins, chemicals, petroleum, coal, and minerals—essentially rehearsing the merger before it happened.

In April 2003, they formalized the relationship by creating a joint holding company: Nissho Iwai–Nichimen Holdings. In 2004, that holding company took the name Sojitz. And in August 2004, Sojitz Corporation officially came into being as a unified operating company—Nichimen Corporation and Nissho Iwai Corporation folded into one.

The newly formed Sojitz came out of the gate at meaningful scale, reporting revenue of roughly 3.3 trillion yen in its first year after formation. It wasn’t a scrappy startup. It was a fully-fledged trading house, reassembled for a new era.

But combining two large organizations is never just a legal process. It’s culture, systems, duplicated roles, and rival internal identities—all being forced into a single company while the outside world watches for weakness.

What Sojitz did have, though, was inherited advantage: a rare blend of corporate DNA built across three very different houses. Through Nichimen and Nissho Iwai, it traced its lineage back to Japan Cotton Trading Co., Iwai & Co., and Suzuki & Co.—companies that had existed, in one form or another, through Japan’s opening to the world, the industrial sprint of the Meiji and Taisho eras, the postwar rebuilding, and the boom years that followed.

So when Sojitz said “twin suns,” it wasn’t just describing a merger of equals.

It was stitching together a long, dramatic lineage—and betting that this time, the rebuild would stick.

VII. The BRICs Era and Resource Scramble (2004-2012)

Sojitz was born at exactly the moment the global economy flipped into a new gear.

In 2004, emerging markets—especially the BRICs—moved from buzzword to gravity. Growth shifted east and south, commodity demand surged, and prices followed. For a newly merged trading house trying to prove it belonged at the table, this was both an opportunity and a test. Sojitz leaned into what trading companies do best: secure supply, finance projects, and plant flags early. It strengthened its resource-related businesses and pushed harder into ventures across emerging economies.

In oil and gas, Sojitz acquired crude oil and gas interests in the United Kingdom, the United States, Brazil, Qatar, and Egypt, and it participated in the Tangguh LNG project in Indonesia. In minerals, it doubled down on a long-standing strength—rare metals—working to secure materials like vanadium, molybdenum, nickel, and tungsten.

Coal was part of the same playbook. Sojitz secured interests in Australia and Indonesia, and in 2010 it increased its stake in Queensland’s Minerva Coal Mine to 96%, becoming the site operator.

But the move that mattered most in this era wasn’t oil or coal. It was rare earths—and it would end up looking less like a trade and more like a national contingency plan.

The Rare Earth Pivot

In 2010, a territorial dispute over the Senkaku Islands led China to effectively embargo rare earth exports to Japan. The episode rattled governments and boardrooms alike. After meeting with her Japanese counterpart on October 27, 2010, US Secretary of State Hillary Clinton publicly raised concerns over allegations of a Chinese ban on rare earth exports to Japan. “This served as a wakeup call.”

Japan’s response was to find alternatives, fast—and Sojitz became one of the key commercial vehicles to do it.

Just days after China ended its rare earth embargo, JOGMEC oversaw the signing of a $250 million deal between Sojitz and Australia’s Lynas. Lynas then raised $450 million in a share sale, and in November 2010 signed an agreement with Sojitz to export €450 million worth of rare earth minerals from its Mount Weld mine.

The structure was straightforward but powerful: Sojitz signed a distribution and agency agreement with Lynas to be appointed the sole distributor and sole agent of Lynas in Japan, enabling Sojitz to provide a stable supply of high-quality rare earth products to Japanese customers.

Backed by $250 million from Sojitz and JOGMEC, the 2010 deal guaranteed Japan more than 9,000 tonnes per year of rare earth oxides from Lynas starting in 2013.

And it worked. Within a decade, Japan reduced its reliance on Chinese rare earths from about 90% down to 58% through a broader strategy—investing in overseas mines, developing technologies and materials to reduce rare earth usage, and diversifying supply chains.

The partnership kept deepening. Sojitz and JOGMEC later entered into an agreement with Lynas to supply up to 65% of the heavy rare earths (dysprosium and terbium) produced by Lynas from Mt. Weld feedstock to the Japanese market. In 2011, Sojitz became the sole distributor of Lynas’ rare earth products in Japan and has provided rare earths to Japanese customers for uses including magnets.

And the story didn’t end in the 2010s. In October 2025, Sojitz signed onto a rare earths deal struck between the United States and Australia, including expansion of an Alcoa facility in Wagerup, Western Australia, to add a gallium processing facility known as the Gallium Recovery Project—funding half of the project.

This rare earth chapter captures Sojitz’s real value proposition. It may have been smaller than the Big Five, but in specific arenas where speed, relationships, and supply-chain architecture matter most, it built positions that were genuinely differentiated.

VIII. Non-Resource Diversification and The Pivot (2013-2020)

By the early 2010s, the commodity supercycle had started to feel less like a tailwind and more like a trap. Prices swung. Earnings swung with them. And Sojitz—like every trading house that had leaned hard into resources—relearned an old lesson: if too much of your profit rides on commodities, you’re volunteering for boom-and-bust.

So the company pushed in a different direction. It began building up non-resource businesses that could compound more steadily: services, infrastructure, logistics, and platforms that didn’t depend on where oil or coal happened to trade that year.

Vietnam: The Strategic Anchor

One of Sojitz’s most important long-term bets sat in plain sight: Vietnam.

Sojitz was the first company associated with the Western bloc to establish a liaison office in Vietnam, and it stayed. Decades later, it had grown from an early presence into a broad operating footprint. Sojitz established a representative office in Việt Nam 38 years ago, and it became involved across a wide range of sectors—from trade and import-export to logistics centers, industrial park investment, retail systems, and agriculture. Along the way, it built a local network of 25 subsidiaries.

Industrial parks became a particularly tangible expression of the strategy. Sojitz had been involved in the development and operation of Long Duc Industrial Park since 2011. By 2019, all available lots were sold out, and about 70 companies—59 of them Japanese—were operating there.

That Vietnam play fit into a wider pattern, too. Sojitz built up more than two decades of experience operating industrial parks across Vietnam, Indonesia, India, the Philippines, and Thailand. And it wasn’t just real estate and infrastructure: Sojitz also had 17 joint ventures in Vietnam, including one with Vinamilk, the country’s largest dairy producer.

The Aerospace Crown Jewel

If Vietnam was the strategic anchor, aerospace was one of Sojitz’s quiet crown jewels.

Through its subsidiary Sojitz Aerospace Company, Sojitz became the largest seller of commercial aircraft in Japan by serving as a sales agent for both Boeing and Bombardier Aerospace.

The Boeing relationship, in particular, went deep. Sojitz served as a sales agent for Boeing commercial aircraft for more than 65 years, starting with its first agreement in 1956. Over the decades, it worked with Boeing to supply passenger aircraft to airlines in Japan—and that long runway of trust helped Sojitz hold the top share of the domestic market.

It’s the kind of asset a general trading company loves: durable, relationship-driven, and hard to dislodge—built over generations rather than quarters.

And Sojitz kept expanding its role. It placed orders for a Bombardier Global 6500 and a Global 8000 aircraft, which were set to serve as the foundation for Sojitz’s first large business jet shared ownership program, designed for trans-Pacific operations.

IX. The Buffett Effect and Japanese Trading Company Renaissance (2020-Present)

On August 31, 2020—Warren Buffett’s 90th birthday—Berkshire Hathaway revealed a move that snapped global investors’ attention back to Japan: it had quietly built roughly 5% stakes in each of the country’s five largest trading houses.

Buffett explained that he’d been buying steadily on the Tokyo Stock Exchange, drawn in by what looked, to him, like an obvious mismatch between quality and price. He said he was “confounded” by the opportunity—and liked the trading houses’ ability to grow dividends.

The five Berkshire bought were the Big Five: Itochu, Marubeni, Mitsubishi, Mitsui, and Sumitomo.

And that detail matters, because Buffett didn’t buy the Big Seven. Sojitz and Toyota Tsusho were left out.

Why not Sojitz? The most plausible answer is the least dramatic: size. Buffett described flipping through a handbook of thousands of Japanese companies, finding five trading houses “selling at ridiculously low prices,” and then spending about a year building the positions. Berkshire needs investments that can absorb meaningful capital, and by market cap the Big Five are several times larger than Sojitz.

The bet paid off. By the end of 2024, Berkshire’s Japanese trading-house stakes were worth $23.5 billion, versus an aggregate cost of $13.8 billion—up about 70%.

But here’s the interesting part for Sojitz: even without a direct Buffett check, it still benefited from what came next.

Berkshire didn’t just buy and sit. It kept leaning in—raising its holdings by more than a percentage point each, to stakes ranging from 8.5% to 9.8%. In his 2024 annual letter, Buffett said Berkshire was committed to these Japanese investments for the long term, describing the sogo shosha as companies that invest across a wide range of sectors at home and abroad “in a manner somewhat similar to Berkshire itself.”

That endorsement did two things at once. It rerated the whole sector in the eyes of international investors, and it reframed the trading houses as something more understandable: diversified, cash-generative portfolios with disciplined shareholder returns.

The Big Five also had the kind of attributes Buffett reliably gravitates toward—global resource footprints, supply-chain integration, resilience across cycles, and generous dividends. When Berkshire first invested, they were trading at low price-to-book ratios, roughly 0.5 to 0.7, with dividend yields typically above 5%. Even after years of stock-price gains, their valuations remained below the broader Japanese market, and shareholder payouts stayed meaningful—on average, up to 46% of profits allocated to dividends.

Sojitz wasn’t in the Berkshire basket. But the basket lifted the whole aisle.

X. Medium-Term Management Plans: The Sojitz Growth Story (2020-2030)

With the sector back in vogue, Sojitz faced a familiar challenge: attention is nice, but it doesn’t substitute for a plan. So the company laid out its next chapter through a series of medium-term management plans meant to make Sojitz feel less like “the seventh shosha” and more like a business with a distinct edge.

In May 2024, Sojitz launched Medium-term Management Plan 2026 -Set for Next Stage-, its new three-year plan. The idea was to define a clear “Next Stage” destination, then use 2026 to establish and reinforce the business foundation to get there. The plan’s signature concept is what Sojitz calls “Katamari”: revenue-generating clusters of businesses that are meant to compound together and express Sojitz’s unique identity, rather than feeling like a loose collection of trades.

Financial Performance

The numbers show why Sojitz felt it had earned the right to be ambitious. Consolidated revenue grew from 1,602,485 million yen in FY2021 to 2,509,714 million yen in FY2025. Profit before tax rose from 37,420 million yen in FY2021 to 135,300 million yen in FY2025. Profit for the year attributable to owners of the Company increased from 27,001 million yen in FY2021 to 110,636 million yen in FY2025.

In FY2024, profit for the year reached 110.6 billion yen, beating the initial forecast and the previous fiscal year, with ROE of 11.7% as planned.

MTP2023 was positioned explicitly as a corporate value improvement plan, with PBR>1.0x set as a key KPI. Sojitz achieved PBR>1.0x by improving ROE, reducing its cost of capital, and executing dividends and share repurchases. It achieved all quantitative targets of MTP2023 through stronger earnings power and improved capital efficiency.

Strategic Priorities for MTP 2026

MTP2026 narrows the company’s near-term initiatives to four areas: 1. Offset Solutions, 2. Biofuel, 3. E-fuel and 4. H2, Ammonia and CCS. The strategy is to select competitive projects within those themes and bring them online steadily, starting with the ones that can be commercialized first. In FY2024, Sojitz focused on building out biofuel and offset solutions projects expected to begin contributing to earnings quickly.

Alongside that push, Sojitz has been deploying capital at scale. To date, it has executed a cumulative total of about 200 billion yen in new investments, concentrating on areas where it believes it can leverage its strengths. A growing share of these investments are sizable—each in the double-digit billions of yen. Major examples include Capella, an infrastructure developer in Australia; FreeState Electric, a U.S. energy-saving services company with strength in electrical equipment work; and Nippon A&L, which produces materials used in lithium-ion batteries. Sojitz positions these as businesses with the potential to become foundations for future growth.

A key thread running through the plan is portfolio rebalancing away from commodity volatility. Sojitz increased the proportion of earnings from non-resource businesses as stable sources of profit through new investments, and it expects the share of core operating cash flow generated by non-resource businesses to exceed 85%, reflecting a growing contribution from these sectors and a more resilient cash flow structure.

Sustainability Initiatives

Underpinning all of this is sustainability, framed not as a side effort but as a set of investment targets. Sojitz set a goal of achieving a carbon-neutral footprint by 2050, and it plans to invest over 100 billion yen in renewable energy projects through 2030.

One example under Medium-term Management Plan 2026 is its push in solar through its independent power producer business: Sojitz plans to develop 3,000 small-scale distributed solar projects across Japan through its subsidiary, Sojitz Mirai Power Corporation. In total, these 200 solar power plants are planned to represent 10 MW of combined capacity and supply renewable energy for 20 years.

And Sojitz has been expanding into new geographies for next-generation energy as well. As of May 2025, it was expanding into biomethane production and sales in India, with plans to invest over $400 million to establish 30 biomethane plants by FY2026-2027.

XI. Competitive Positioning and Strategic Assessment

So where does that leave Sojitz today?

It’s operating in one of Japan’s most competitive arenas, in a business model that looks simple from the outside and is maddeningly hard to replicate from the inside. A useful way to see the playing field is through two classic strategy lenses: Porter’s Five Forces and Hamilton Helmer’s Seven Powers. We’ll keep it practical and tied to what actually matters for Sojitz.

Porter's Five Forces Analysis

Threat of New Entrants: Low

A true sogo shosha isn’t something you spin up with a slick website and a few regional offices. The moat is time: decades of supplier relationships, credibility with customers, experience financing and executing complex projects, and the kind of institutional trust—often including government relationships—that’s built slowly and tested in crises. Capital requirements are huge, but the real barrier is know-how across dozens of industries.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers: Moderate

Sojitz buys from thousands of suppliers worldwide, so any single vendor usually doesn’t have much leverage. But in concentrated resource markets, the balance can flip quickly. Rare earths are a perfect example: when supply is constrained or politically weaponized, suppliers gain power and trading houses scramble to secure alternatives.

Bargaining Power of Buyers: Moderate

Sojitz sells to everyone from industrial giants to consumer-facing channels. Big corporate customers can negotiate hard, especially when products look commoditized. But Sojitz isn’t just moving boxes. In the relationships that matter most, it’s providing financing, logistics, and long-term coordination. That role creates real switching friction—customers aren’t only choosing a price, they’re choosing an operating partner.

Threat of Substitutes: Moderate and Increasing

This is the pressure point for every trading company. Manufacturers can source directly. Customers can vertically integrate. Digital platforms can compress information advantages. The response from the shosha—including Sojitz—has been to move up the value stack: less “middleman,” more project developer, investor, operator, and supply-chain architect.

Competitive Rivalry: High

Competition among the seven major sogo shosha is relentless. The Big Five dominate on scale, and they can outbid, outstaff, and outwait smaller rivals. That reality forces Sojitz into a different game: win by being specific. Build defensible positions in pockets like rare earths, aerospace, and emerging-market industrial parks—places where relationships, speed, and execution matter as much as balance sheet size.

Hamilton Helmer's Seven Powers Framework

Scale Economies: Limited

Relative to the giants, Sojitz can’t spread fixed costs over the same revenue base. That makes scale-driven advantages harder to claim—and puts a premium on choosing businesses where being smaller isn’t fatal.

Network Economies: Moderate

Sojitz benefits as its web of suppliers, customers, and partners grows—but it’s not a platform business where every new participant increases value for everyone. The network effects are real, but they’re usually contained within specific verticals or geographies.

Counter-Positioning: A potential strength

This is where “seventh place” can become an advantage. Sojitz can pursue opportunities that are too small, too specialized, or too fiddly for bigger peers. The Lynas rare earth partnership is the archetype: a targeted, strategically important deal that rewards focus more than brute force.

Switching Costs: Moderate to high in the right relationships

In some businesses, customers can switch quickly. In others, the relationship becomes embedded over decades. A 65-year partnership serving as a sales agent for Boeing is the kind of accumulated trust and operational muscle that’s difficult to replicate and hard to displace.

Branding: Limited consumer visibility, strong niche credibility

Sojitz isn’t a consumer brand. But in B2B niches—where counterparties care about reliability, financing capacity, and execution—reputation is currency. In those pockets, Sojitz’s brand carries weight.

Cornered Resource: Present in select areas

Sojitz’s sole-distribution arrangement tied to Lynas’ rare earth products for Japan is a form of cornered resource: access that isn’t perfectly interchangeable. The Boeing sales agency relationship functions similarly—less a legal monopoly than a deeply entrenched commercial position.

Process Power: Earned the hard way

Few corporate lineages have been stress-tested like Sojitz’s. The institutional memory of collapse, restructuring, and reinvention can translate into unusually strong muscles for risk management and adaptation—especially when cycles turn and markets break.

Key Risks

Commodity Price Volatility: Still a factor

Even with diversification, metals and energy remain meaningful contributors. When coal prices fall or production efficiency slips, profits take the hit. Sojitz’s strategy has been to reduce dependence on these swings—but it hasn’t eliminated them.

Geopolitical Risk: The unavoidable tax of operating globally

With operations across 50 countries, Sojitz lives with sanctions risk, trade wars, regulatory shocks, and political instability. The company’s outlook for FY2025 anticipated profit for the year of JPY120.0bn, while factoring in an estimated negative JPY5.0bn impact from U.S. tariff measures.

Currency Risk: Small moves add up

Exchange rates matter in a trading house. Sojitz estimates that a JPY1 move against the US dollar changes gross profit by about JPY0.8 billion annually and profit for the year by about JPY0.3 billion annually.

Scale Disadvantage: The strategic constraint that never goes away

Sojitz is still seventh out of seven. And unlike the Big Five, it didn’t get the direct Buffett spotlight. That doesn’t mean it can’t win—but it does mean it has to keep earning attention through performance, discipline, and finding angles the giants either overlook or can’t execute as cleanly.

XII. Metrics That Matter

If you’re tracking Sojitz like an investor—and not just reading the story—three metrics tell you whether the “seventh shosha” is actually pulling off its transformation.

1. Non-Resource Profit Ratio

This is the clearest scoreboard for Sojitz’s push away from commodity-driven boom-and-bust. Management expects more than 85% of core operating cash flow to come from non-resource businesses, which would mean the portfolio is getting meaningfully steadier. The question is simple: does that share keep rising over time, or does the company get pulled back into the gravity of resources when prices are attractive?

2. Return on Equity (ROE)

Sojitz isn’t just trying to grow—it’s trying to grow well. Under Medium-term Management Plan 2026, it set CROIC-based value creation targets by division, with the larger goal of reaching 15% ROE at its “Next Stage.” It delivered 11.7% ROE in FY2024, and the climb from there is a real test of execution: better capital discipline, better business mix, and fewer low-return uses of the balance sheet. If it gets there, it starts to look a lot more like the leaders, not just the challenger.

3. Core Operating Cash Flow

In a trading company, cash is the truth serum. Sojitz is aiming for roughly 450 billion yen of basic operating cash flow over the three years of Medium-term Management Plan 2026. That number matters because high-quality, repeatable cash generation is what funds everything else: dividends, buybacks, and the next round of investments. Earnings can be noisy in this model; cash flow is what tells you whether the engine is really compounding.

XIII. Bull Case and Bear Case

The Bull Case

Niche Dominance: Sojitz has carved out positions that are hard to dislodge in a few specific arenas—rare earths, aerospace, and Vietnam—areas where the biggest competitors don’t always lead with the same intensity. If the world keeps moving toward supply-chain diversification, those “small enough to matter, big enough to scale” niches can punch above their weight.

Japan Inc. Renaissance: Berkshire’s move didn’t just lift five stocks; it changed the narrative around the entire sogo shosha model. More global capital started paying attention, and in a sector rerating, even the seventh-place player can ride the tide.

Valuation Gap: Sojitz has often traded at a meaningful discount to larger peers despite operating the same core model. If that gap narrows—through better returns, better investor communication, or simply a warmer market for trading houses—the upside doesn’t require perfection. It just requires “less discounted than before.”

Sustainability Transition: The company is trying to participate in the energy transition in a way that looks like evolution, not self-sabotage—building renewables, biomethane, and energy-efficiency businesses while still managing legacy profit engines.

Management Execution: Medium-term Management Plan 2023 wasn’t just a set of promises; Sojitz hit its quantitative targets. If it can repeat that kind of execution under Medium-term Management Plan 2026, the market has a straightforward reason to reward it: higher confidence in the plan, and higher willingness to pay for the cash flows.

The Bear Case

Structural Disadvantage: Scale is a law of gravity in this industry. The Big Five can outbid, outstaff, and outwait on marquee deals, and Sojitz may find itself confined to “where the giants aren’t,” whether that’s a strategic choice or not.

Commodity Volatility: Even with diversification, resources still matter. If commodity prices fall and stay low, results get squeezed—especially because trading companies can’t fully control the cycles they’re exposed to.

Buffett Effect Exclusion: Buffett didn’t buy Sojitz, and markets notice those omissions as much as the inclusions. Fair or not, that can harden into a perception that Sojitz is a tier below the names Berkshire chose—making it harder to win a premium multiple.

Execution Risk: Pivoting from resource-heavy earnings to more stable non-resource profit isn’t just portfolio math. It demands new operating capabilities, different risk management, and disciplined capital allocation. Many transformations look clean in slide decks and messy in the real world.

Geopolitical Exposure: Vietnam has been a strength—until geopolitics turns it into a vulnerability. A sharper deterioration in U.S.-China relations, or a reshuffling of regional supply chains, could complicate the very strategy that Sojitz has leaned into.

XIV. Conclusion: The DNA of Survival

So what does Sojitz’s 160-year heritage actually mean today? It isn’t just a nice anniversary line. It’s a record of stress tests.

Organizations that have lived through catastrophe—the burning of Suzuki’s headquarters in 1918, the financial panic of 1927, and the post-bubble squeeze of the 1990s—tend to develop something that pure success stories never have to build: instincts. A kind of institutional immune system. When you’ve seen the downside up close, you get serious about liquidity, counterparties, concentration risk, and reputation—not as abstract concepts, but as matters of survival.

Sojitz itself has tried to articulate that continuity in plain language. In one internal message, the company put it this way:

I would like you to understand that the company you have joined continues to carry on the business pioneering DNA of its predecessors. For over a century, we have continued to fulfill our mission as a general trading company to provide the necessary goods, services, and ideas to places where there is a need.

That’s the throughline. Not “we are the biggest.” Not “we win every deal.” It’s: we show up where there’s demand, we connect the dots, and we keep doing it through cycles that break other firms.

Sojitz isn’t Mitsubishi or Mitsui. It never has been, and it probably never will be. But it doesn’t need to be. As the smallest of the seven sogo shosha, it has made a habit of winning in places where brute scale matters less than persistence and positioning: rare earth supply chains, aerospace relationships built over decades, and industrial parks in Vietnam that turn long-term presence into long-term advantage.

And despite the “seventh-place” label, the platform is anything but small. Sojitz was formed from the union of Nichimen Corporation and Nissho Iwai Corporation—two companies with extraordinarily long histories. Over more than 160 years, this lineage has helped support development across countries and regions. Today, the Sojitz Group spans roughly 400 subsidiaries and affiliates across Japan and the world.

That’s what makes the name feel earned. The twin suns that rose from Yone Suzuki’s ashes traveled a long arc—from the smoldering ruins of Kobe in 1918 to a modern trading house operating across 50 countries, generating more than 2.5 trillion yen in annual revenue. It’s a story of reinvention, and of a uniquely Japanese business model that even Warren Buffett—an investor who has seen everything—called “confounding” in how undervalued it could be.

Whether Sojitz closes the gap with larger peers or continues compounding through carefully chosen niches while the Big Five dominate the headlines is still an open question. But for investors looking for exposure to Japan’s trade infrastructure, emerging-market industrial development, and strategically sensitive materials like rare earths, Sojitz offers something its larger rivals can’t quite replicate.

Not size.

Survival.

The company trades as ticker 2768 on the Tokyo Stock Exchange. As of recent trading, shares were around 3,977 JPY with a market capitalization of approximately 840 billion yen. The company has approximately 25,000 employees across its global operations.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music