HD Hyundai Electric: The Power Behind the Grid Revolution

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

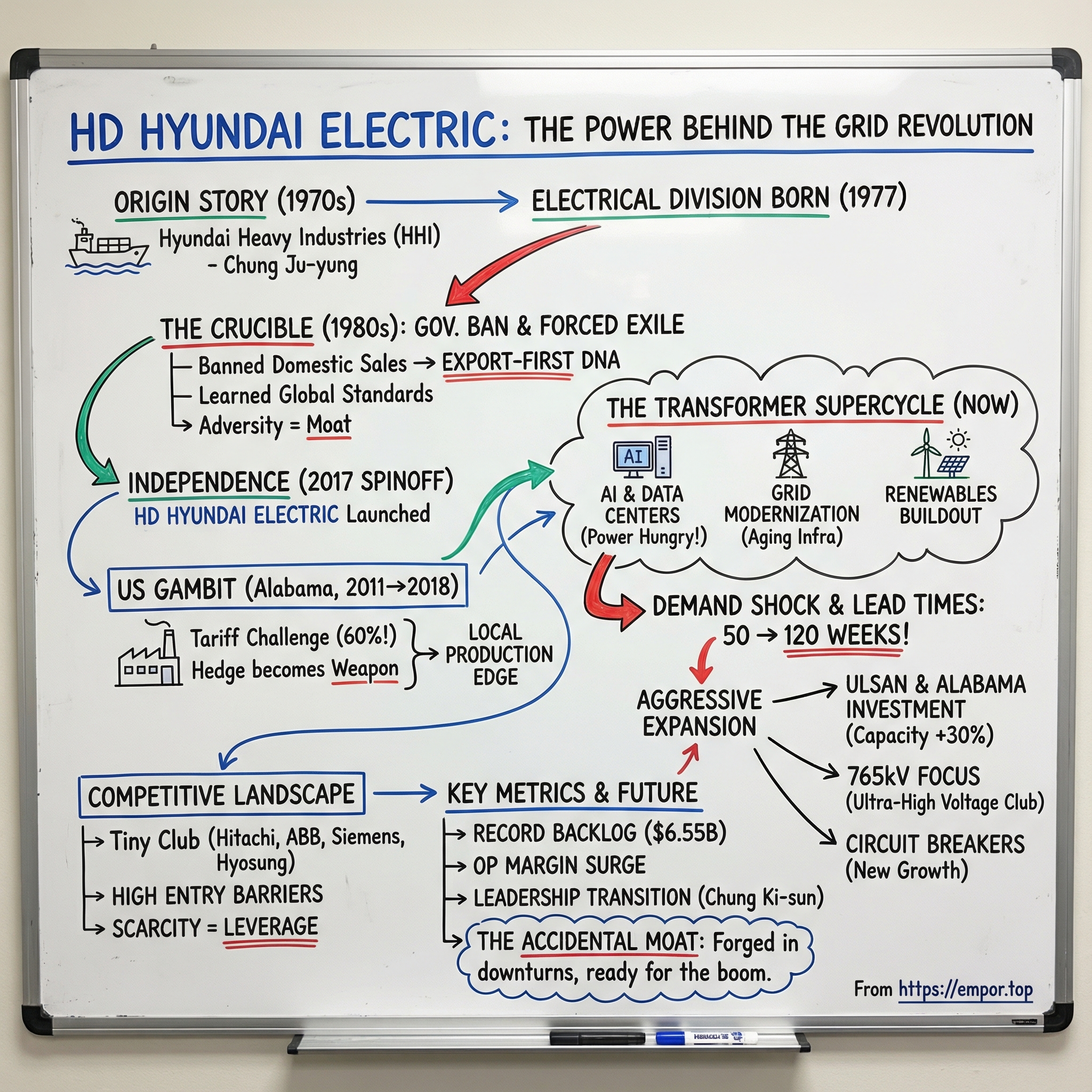

In the summer of 2023, something quietly historic rumbled out of Montgomery, Alabama.

A truck eased away from a plain-looking factory on the edge of town carrying a single, absurdly heavy piece of equipment: a 200-ton, ultra-high-voltage transformer. One of those oil-filled steel giants that almost nobody notices—until something breaks and an entire region goes dark. This unit was headed for Texas. And it wasn’t a one-off. It was one of twenty-four in a single order worth nearly $200 million.

But the real twist isn’t the transformer. It’s the name on the build sheet.

It came from HD Hyundai Electric, a South Korean manufacturer operating inside the U.S. at a moment when Washington has been slapping steep tariffs on imported transformers. Normally, that kind of policy would kneecap foreign suppliers. Here, it didn’t—because there’s a hard constraint tariffs can’t fix: only about ten companies worldwide can build 765 kV transformers at all. In a market like that, scarcity is negotiating leverage.

And Hyundai Electric has been steadily turning that leverage into something much bigger. The United States is now its largest market, contributing about 40% of revenue in the first half of 2025. It also holds the largest share of the U.S. market for ultra-high-capacity transformers—those 200-ton machines that can cost up to 13 billion won each.

That’s the paradox at the center of this story: the company now helping power America’s grid was once barred by its own government from selling power equipment at home. In the 1980s, South Korea’s industrial planners effectively exiled the business from the domestic market. While competitors stayed comfortable serving protected local customers, Hyundai Electric had no choice but to learn how to win abroad. What looked like a punishment turned into an export muscle memory—and eventually, an enduring edge.

By 2017, it had shipped a cumulative total of over 1.2 million kWA transformers to 70 countries. Since 1999, it has secured more than 160 contracts for 765 kV transformers worldwide. Those aren’t just bragging rights; they’re proof of membership in a tiny club of manufacturers that can build the highest-voltage equipment modern grids depend on.

And the timing is almost unnervingly perfect. The AI boom and the data-center buildout are turning electricity into the new bottleneck. U.S. data centers consumed 183 terawatt-hours in 2024—more than 4% of the country’s electricity. By 2030, that’s projected to more than double to 426 TWh. All of that power has to move from generators to servers, and the critical, scarce hardware in between is… transformers.

The result is a brutal queue. Where lead times were measured in months not long ago, utilities and developers now routinely face waits of years. In the U.S., lead times stretched from roughly 50 weeks in 2021 to about 120 weeks on average by 2024—meaning a transformer order can feel less like procurement and more like reserving a slot in a multi-year production schedule.

So this isn’t just a supply chain story, and it’s definitely not just a story about tariffs. It’s what happens when geopolitics, aging infrastructure, and a once-in-a-generation demand shock collide with one of the most specialized manufacturing skills on Earth. HD Hyundai Electric sits right at that intersection—of America’s grid rebuild, renewable expansion, and AI-driven load growth—and its journey from a forced export strategy to indispensable infrastructure is the thread that ties it all together.

II. The Chung Ju-yung Origin Story & Hyundai Heavy Industries Context

To understand HD Hyundai Electric, you have to start with the empire it came from — and with the man who built that empire: Chung Ju-yung, the founder of the Hyundai Group.

Chung’s story begins in poverty so extreme it’s hard to map onto modern life. He was born on November 25, 1915, in Tongchon County on the Korean Peninsula during the period of Japanese rule (in what is now Kangwon Province, North Korea). He spent his early years around his family’s farm, and when he had the chance to get into town, he took it — attending his grandfather’s Confucian school and selling wood on the side to help his family make ends meet.

But farm life wasn’t the plan.

As a teenager, he and a friend tried to run to Seoul by selling one of his family’s cows to buy a train ticket. His father tracked him down two months later and hauled him back home. That didn’t stick. At eighteen, Chung made his final escape, slipping out at night and heading to Seoul for good.

There, he did what ambitious young people with no safety net have always done: he took whatever work he could find. He landed at a rice store as a delivery man, and within six months he’d made himself indispensable — promoted to bookkeeper and accountant.

His first real swing at entrepreneurship came in 1938, when he opened his own rice store. It lasted a year before Japanese occupation policies forced it to shut down. After Korea’s liberation in World War II, Chung moved into repairing trucks for U.S. Armed Forces — then into engineering and construction — and eventually into the kind of mega-projects that turn builders into institutions.

And that takes us to the defining Hyundai legend — the one that captures the organization’s operating system.

In 1971, Chung traveled to England to secure a loan for a shipyard he hadn’t built yet. What he carried with him sounded almost comical: shipyard plan documents and a single photograph of a barren, sandy beach at Mipo Bay. In the meeting, he argued that Koreans had been master shipbuilders for centuries. As proof, he showed a 500 won bill featuring the Turtle Ship, the famous Korean ironclad. Against all logic, he walked out with a $100 million loan.

Even better: he also took orders for ships without having a shipyard. He secured a contract for two oil tankers totaling 260 thousand tons from Greek shipping magnate Livanos.

Then Hyundai did the thing that turned the story into scripture. With the idea that you could build the yard and the ships at the same time, Hyundai began digging the dock at Ulsan while constructing the vessels. In roughly two years, it completed the shipyard — and delivered the tankers.

This wasn’t just bravado. It was a blueprint for how Hyundai would operate: move first, absorb complexity fast, and learn by doing at industrial scale.

Hyundai Shipbuilding & Heavy Industries was established in 1972, and it didn’t happen in a vacuum. South Korea’s government wanted to push the country beyond light manufacturing exports into heavy industry, and it backed that ambition with support like guarantees for foreign loans and investment in industrial complexes. Chung, meanwhile, excelled at the other half of the equation: securing technology, convincing partners, and pulling customers forward into bets they weren’t sure they wanted to make.

Now here’s the key pivot for our story: electricity.

In late 1970, Chung visited Mitsubishi Heavy Industries in Japan to benchmark shipbuilding. But as he looked around, he noticed something else — power equipment. The sales were big. The demand was durable. So when he returned to Korea, he gathered Hyundai’s electrical engineers and, in 1978, founded an electric company: Hyundai Heavy Electric — the predecessor to what would become Hyundai Electric.

That origin story matters because it set the DNA that HD Hyundai Electric would rely on for decades: opportunism paired with industrial courage. If Hyundai could sell ships before it had a shipyard, it could certainly bet on building the unglamorous hardware that makes modern industry run. And by the time Chung retired in 1991, Hyundai had grown so large it accounted for about 16 percent of Korea’s GDP and 12 percent of its total exports.

III. Birth of the Electric Division & The 1980s Government Restructuring Crucible

Hyundai’s move into heavy electrical equipment started inside the shipbuilding giant. In 1977, Hyundai Heavy Industries created a Heavy Electrical Equipment Division. A year later, it was building transformers. And by November 1978, the business had been spun out as its own company: Hyundai Heavy Electric.

From the beginning, this wasn’t a “learn slowly at home, then export later” kind of operation. Hyundai went hunting for world-class know-how. It formed technical partnerships with Western players, including a joint venture with Westinghouse in the United States to develop rotating machines for generator and industrial use. It pursued international quality certifications. And it worked with Ukraine’s VIT to develop 765 kV transformers and 154 kV gas-insulated transformers.

That matters because ultra-high-voltage transformer manufacturing isn’t something you master by reading manuals. The tolerances are unforgiving. A tiny mistake in insulation or assembly can turn into catastrophic failure in the field. What separates the handful of companies that can do this work from the many that can’t is less about “having a factory” and more about decades of accumulated, hard-earned process knowledge.

Then the government stepped in—and everything changed.

In the early 1980s, South Korea launched a broad restructuring of the heavy and chemical industries. Hyundai Heavy Electric got caught in it. The government unified the domestic transformer market, and the breaker market was consolidated around a competitor (Venus War, now LSIS). Hyundai Heavy Electric was effectively exiled: it was banned from selling domestic power devices for ten years.

Put yourself in their position. This was still a young business, building capability, trying to mature its product lines. And overnight, the safest customer base—the home market—was off-limits. The predictable utility orders that would normally fund learning curves and expansion disappeared. The company didn’t get to grow up gradually. It got thrown into international competition early, whether it was ready or not.

It should have been fatal. Instead, it became the company’s defining advantage.

Locked out at home, Hyundai Heavy Electric did the only thing it could do: it went overseas and stayed there. Over that decade, it was forced to become export-first in its DNA—building global sales channels, meeting international standards that were tougher than what the domestic market demanded, earning certifications, and figuring out how to deliver and service equipment that can weigh as much as a commercial aircraft.

That’s counter-positioning in the purest sense, even if nobody used the term at the time. While domestic competitors stayed comfortable inside a protected market, Hyundai Heavy Electric built the muscles required to win abroad. Those muscles never went away. Even today, roughly 70% of the company’s sales come from overseas.

Out of that crucible, it grew into a real global contender—competing with names like GE, ABB, Siemens, and Schneider in power infrastructure. It also built significant manufacturing scale, with the ability to produce 120,000 MVA of transformers per year in Korea, and transformers make up about 30% of its sales. It ranks fifth in global transformer market share, behind ABB, Siemens, and GE.

And one region, in particular, became a proving ground: the Middle East.

During the oil boom years, Hyundai Heavy Electric built early relationships with utilities in Saudi Arabia and across the Gulf—relationships that turned into repeat business over decades. As part of the Hyundai Heavy Industries orbit, it rose to the top position in Saudi Arabia. Over time, the company worked to reduce over-reliance on any single region: the Middle East makes up about 17% of overseas revenue today, down from around 30% in the early 2010s.

The big takeaway is almost uncomfortable in how often it shows up in industrial history: adversity can be the thing that creates the moat. A government policy designed to reshape the domestic market ended up forging an export-oriented company with global-grade capabilities—exactly the kind of company that would be positioned to seize the next wave of grid investment when it finally arrived.

IV. The Asian Financial Crisis, Hyundai Group Breakup & Division Cycles (1993-2016)

In 1993, Hyundai folded the electrical equipment business back into Hyundai Heavy Industries, where it became the Heavy Electricity Business Division. In 2001, it was renamed the Electrical and Electronic Systems Business Division.

For the next two decades, that business lived inside the machinery of a much larger conglomerate. That meant stability, capital, and global reach when things were good. It also meant whiplash when the parent company’s priorities shifted. Through it all, the division kept doing the unglamorous work that matters in power equipment: building manufacturing discipline, expanding internationally, and steadily climbing the learning curve that separates competent suppliers from the tiny handful that utilities will trust with the most critical gear on the grid.

Then Hyundai’s own family drama redrew the map.

After the 1997 Asian financial crisis and founder Chung Ju-yung’s death, the Hyundai empire began breaking into separate groups. Over time, major businesses spun off into what became Hyundai Motor Group, Hyundai Department Store Group, and the Hyundai Heavy Industries Group.

In the early 2000s, the succession battle intensified among Chung’s sons. While the primary feud was between the second son, Chung Mong-koo, and the fifth son, Chung Mong-hun, the sixth son, Chung Mong-joon, separated himself from the group and took the heavy industries arm with him. In 2002, that separation formalized: the business spun off from Hyundai Group and became the Hyundai Heavy Industries Group.

Chung Mong-joon is a character you don’t see every day in global industrial history: an industrialist who became a politician and still remained the controlling shareholder. Born on November 15, 1951, he joined Hyundai Heavy Industries, became CEO in 1982, and chairman in 1987—helping oversee its rise as a shipbuilding powerhouse—before moving into politics in 1988. He later served in the National Assembly representing Ulsan, and he remains the largest shareholder of what is now HD Hyundai.

His background matched the unusual path. He studied economics at Seoul National University, earned an MBA at MIT, and completed a doctorate in international relations at Johns Hopkins University. He also dove into sports governance, becoming president of the Korean Archery Association.

That mix—political visibility plus industrial control—pushed the group toward a distinctive governance model. Although Chung Mong-joon inherited control from his father, the company has been run through a professional management chairman system rather than direct, day-to-day management by him, in part to avoid the distractions and misunderstandings that can come when the controlling shareholder is also a public political figure.

Meanwhile, the electrical equipment division kept expanding. The Middle East stayed central, and Saudi Arabia remained its strongest foothold. But the larger organization it lived inside was heading toward a storm that would change everything.

By the mid-2010s, global shipbuilding was in a full-blown crisis. Debt piled up as a trade slowdown collided with too many ships chasing too little demand, and low freight rates punished everyone. The “Big Three” Korean shipbuilders—Daewoo Shipbuilding & Marine Engineering, Hyundai Heavy Industries, and Samsung Heavy Industries—carried $42.1 billion in loans between them. They finished 2015 with combined losses of more than $6 billion. This was no niche problem: shipbuilding accounted for about 6.5% of Korea’s GDP.

The underlying issue was structural. Years of overbuilding during the commodity supercycle created massive overcapacity, just as Chinese shipyards began competing seriously. Order books collapsed. Losses stacked up. And suddenly, the conglomerate structure that once felt like a moat looked like an anchor—capable of pulling healthier businesses down with the failing ones.

What came next would set the stage for HD Hyundai Electric’s current success.

V. The 2017 Spinoff: Born from Crisis, Destined for Independence

By 2016, the shipbuilding downturn wasn’t just hurting Hyundai Heavy Industries. It was threatening to drag the entire group under with it. So HHI went to its creditors with a restructuring plan that would fundamentally redraw the company: split the conglomerate into four pieces.

Shipbuilding, offshore, and industrial plants would remain inside Hyundai Heavy Industries. The electric systems business, construction equipment, and robotics would be carved out into separate entities.

This wasn’t a tidy “strategy refresh.” It was triage. The goal was to keep a crisis in one division from infecting everything else—and to bring the shipyard’s leverage down. The spinoff was expected to reduce HHI’s debt ratio to about 95% from 106% at the end of the prior year.

And it set off a fight.

Unionized workers opposed the plan and staged a strike for a third consecutive day, disrupting the shareholder meeting so badly it had to be adjourned four times. The union called on its roughly 14,000 members to stage an eight-hour sit-down, following two earlier walkouts, arguing the split would come at the expense of jobs.

Inside the meeting, the tension turned physical. More than a thousand employee-shareholders showed up in protest, clashing with police as they tried to block the voting process. These were the first full work stoppages at Hyundai Heavy in 23 years—an unmistakable signal of how explosive the moment had become.

The union believed the breakup was designed to weaken organized labor and would ultimately lead to layoffs. At the same time, management had proposed a 20% pay cut—something the union refused. Reports said the two sides had held more than 70 meetings over the previous ten months to reach a collective bargaining agreement, without success.

But the numbers that mattered were in the vote. Despite the unrest, shareholders approved the restructuring by an overwhelming 98% margin.

When trading resumed, Hyundai Heavy Industries effectively began life as four publicly traded companies—each focused on one business: shipbuilding and offshore projects, electric machinery, construction equipment, and industrial robots. The combined market value of the four was about 16.8 trillion won, compared to 12.5 trillion won when trading in Hyundai Heavy had been halted in March.

In April 2017, Hyundai Electric was officially launched, born out of the spin-off alongside Hyundai Robotics and Hyundai Construction Equipment.

For the parent shipbuilder, the financial impact was immediate. The spinoff cut net debt roughly in half and brought the debt-to-equity ratio down to 95.6% at the end of March, from 106.1% at the end of 2016.

For Hyundai Electric, independence came with both opportunity and weight. On one hand, it inherited a real global position in power equipment. On the other, it now had to stand on its own—build its own corporate infrastructure, invest in R&D, and prove to investors it wasn’t just a “division” that happened to exist inside a shipbuilder.

The group signaled that this wasn’t going to be a gentle separation. It announced a major commitment: 680 billion won, about $612 million, in R&D investment for Hyundai Electric and Energy System.

This wasn’t a company backing away from the future. It was a company trying to buy it.

What happened next would put that bet to the test.

VI. The Alabama Factory Gambit & US Tariff Challenge (2011-2018)

Hyundai Electric’s U.S. story actually started before it was even an independent company.

In 2011, HD Hyundai Power Transformers opened a plant in Montgomery, Alabama—the first U.S. production facility in the electric power industry built by a South Korean player. At the time, it could have read like a simple, sensible hedge: get closer to the customer, reduce logistics risk, smooth out currency swings.

It ended up looking more like a seatbelt you don’t appreciate until the crash.

That crash came in 2018, when U.S. trade policy slammed Korean-made transformers with punishing anti-dumping duties. For Hyundai Electric, the rate was about 60%—a level that effectively priced Korea-made product out of the market overnight. And this was not a small side business that could be written off. The company was still fundamentally export-driven, with roughly 70% of revenue coming from overseas.

In a world where you can’t ship into a protected market, there’s only one real counter-move: build inside it.

So Hyundai Electric leaned harder into Alabama. It expanded local capacity to sidestep the tariff wall and keep serving U.S. utilities. The contrast inside Korea’s power equipment industry became stark: Hyundai Electric and Hyosung Heavy Industries—both with U.S. transformer plants (in Alabama and Tennessee, respectively)—had a path forward that import-only players didn’t.

The pain didn’t stop at tariffs. Coming out of the 2017 spinoff, Hyundai Electric also took a hit from its heavy exposure to the Middle East, and it had to absorb multiple one-off costs tied to the anti-dumping dispute. It had recorded 2.2 trillion won in sales in 2017, but 2018 quickly turned into a test of whether this newly independent company could take a punch and keep moving.

It kept moving—by making the Alabama site more than just a factory. Hyundai Electric completed a 12,690-square-meter storage facility at the plant, with space for up to 60 finished transformers. The operational payoff was straightforward: completed units could be moved directly into on-site storage, eliminating the need for external warehousing, cutting transport costs, and improving production flow.

And that’s the quiet twist: what began as a defensive foothold became the platform that mattered most later. Last year, about 60% of Hyundai Electric’s annual North American sales came from the Alabama plant.

By the time the transformer supercycle arrived, the company didn’t need to ask permission from tariffs or ocean freight schedules. It already had boots on the ground in the most important market in the world.

For investors, the lesson is optionality. Alabama was built in an era of uncertainty, justified as a hedge. But when the environment shifted—trade barriers up, lead times stretching out, demand spiking—it turned into an offensive weapon.

VII. The Transformer Supercycle: AI, Data Centers & Grid Modernization (2023-Present)

Now zoom out from one factory in Alabama to the system it feeds. The story isn’t just that transformers are hard to build. It’s that the United States needs an enormous number of them, all at once.

Start with the replacement wave. According to the U.S. Department of Energy, roughly 70% of America’s grid transformers are 25 years or older. And the typical service life is about 30 years. In other words, a huge chunk of the grid is nearing the end of its designed lifespan, right as the country is asking it to do more than it ever has before.

Transformers are the quiet enablers of the whole thing. They step voltage up as power leaves a plant so it can travel long distances efficiently, then step it down again so it’s usable for homes, factories, and servers. When you don’t have enough of them, generation doesn’t matter; you can’t move the electricity.

Then comes the demand shock.

The U.S. Department of Energy’s 2024 Report on U.S. Data Center Energy Use, produced by Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, puts a hard frame around what’s happening: data center load growth has tripled over the past decade and is projected to double or even triple again by 2028. And it isn’t only data centers. After decades of relatively flat load growth, U.S. electricity demand is rising again as AI, data centers, domestic manufacturing growth, and broader electrification converge. The International Energy Agency expects data centers to account for nearly half of U.S. electricity demand growth between now and 2030.

The forecasts make the point plainly. Utility power demand from hyperscale, leased, and crypto-mining data centers is expected to rise sharply year after year through the end of the decade.

This isn’t incremental growth. It’s the first major step-change in American electricity consumption in decades—arriving at the exact moment the hardware underneath the grid is aging out.

And that’s how you get the bottleneck everyone is now discovering the hard way: lead times.

Transformer lead times have blown out over the past few years—from around 50 weeks in 2021 to about 120 weeks on average by 2024. For large transformers, especially substation power and generator step-up units, lead times can stretch far longer, with specialized equipment taking the longest. Distribution transformers have also become harder to get, with pad-mounted units taking double or triple the time they did before the pandemic. In some parts of the market, “order a transformer” now effectively means “get in line for the next several years.”

This is the environment HD Hyundai Electric was built for—scarcity, long cycles, and customers who care more about delivery certainty and quality than anything else.

The company’s results show it. It reported sales of 3.32 trillion won, up 22.9% year-on-year, driven in part by strong performance in high-capacity transformer projects in the Middle East.

And in the first quarter of 2025, it crossed a psychological threshold: more than 1 trillion won in quarterly revenue for the first time. Provisional revenue came in at 1.147 trillion won, up 26.7% versus the year prior. Operating profit rose 69.4% to 218.2 billion won, and net profit climbed 64.2% to 153.4 billion won.

Management pointed to higher sales of power equipment and rotating machinery, with power equipment in particular surging versus the prior year. Just as important: North America. The company’s focus there improved profitability and pushed its operating profit margin to 21.5%.

Then there are the contracts—the kind that tell you who utilities trust when they’re spending big and can’t afford mistakes. HD Hyundai Electric signed a 213.6 billion won deal to supply power transformers to Xcel Energy, its largest single-product contract since the 2017 spinoff.

It also won a $199 million contract to supply ultra-high-voltage power equipment to a Texas grid operator—its largest single deal to date. Under the agreement, it will deliver 24 units of 765 kV transformers and reactors by 2029, manufactured at its Ulsan plant. The 765 kV system is the highest voltage used in the United States, designed for efficient long-distance transmission with far greater capacity than the standard 345 kV grid.

And despite tariff pressure, demand has remained strong. The company’s order backlog reached $6.55 billion, up nearly 25% from a year earlier.

That backlog is the tell. In industrial manufacturing, it’s the closest thing you get to forward visibility. At $6.55 billion, HD Hyundai Electric isn’t just having a good quarter—it can see years ahead. By the company’s own internal data, fulfilling the transformers already on order can take as long as five years. To keep up, it has been running its transformer plants in Korea and the United States at full capacity.

VIII. The Aggressive Expansion Strategy: Betting Big on the Supercycle

A backlog like that forces a decision. You either ration what you can build — or you build more.

HD Hyundai Electric chose the second option. The company planned to plow roughly half of its estimated 2024 operating profit, about 720 billion won, back into capacity. The headline number was a 400 billion won investment to lift production by around 30% at its transformer plants in Ulsan, Korea and Montgomery, Alabama, with the ramp targeted by early 2026. It was the biggest investment the company had made since its origins in 1977, and it wasn’t subtle: the spend was larger than its operating profit in 2023.

The aim was simple: more throughput, faster delivery, and less vulnerability to a market where “lead time” had become the defining feature. Once the expansion is completed in 2028, the company projected the Ulsan and Alabama plants would add meaningful incremental sales capacity — with Ulsan contributing the larger share and Alabama adding another layer of U.S.-based output.

Today, Ulsan produces roughly 300 transformers a year, while Alabama produces about 100. The U.S. buildout is especially important. HD Hyundai Electric planned to increase U.S. transformer production capacity by 30% by 2026, scaling annual U.S. output from around 110 ultra-high-voltage units to about 150 — directly aimed at demand from renewables buildouts and data centers.

And the expansion wasn’t just about making more of the same product. HD Hyundai Electric has secured more than 160 contracts for 765 kV transformers worldwide since 1999, and now it’s pushing that capability deeper into North America. The company is building new production capacity for 765 kV equipment at its Alabama site, with operations expected to begin in 2027.

Then there’s the next adjacent bet: circuit breakers. HD Hyundai Electric signaled it wants to expand beyond high-voltage transformers into low- and medium-voltage circuit breakers in North America. It secured UL certification — a crucial gate for the market — with four types of low- and medium-voltage circuit breakers obtaining UL and cUL certifications.

To support that push, the company broke ground on a new factory in the Central Valley General Industrial Complex in Cheongju, North Chungcheong Province. The smart factory, scheduled for completion by October next year, is designed to reach annual capacity of 6.5 million circuit breakers by 2030. With that facility, HD Hyundai Electric expects it can double total circuit breaker production capacity to 13 million units annually by 2030.

The demand drivers rhyme with the transformer story: AI-driven data center growth, and the replacement cycle for aging U.S. power equipment.

None of this happens in a vacuum. HD Hyundai Electric also planned to raise this year’s R&D investment by more than 30% from last year, aiming to keep advancing its ultra-high-capacity transformer technology as competitors race to catch up. North America’s Delta Star and Pennsylvania Transformer Technology, Japan’s Hitachi Energy and Mitsubishi Electric, and Germany’s Siemens Energy have all been moving to expand investment in the U.S. transformer market.

That’s the underlying statement in all these moves: the company believes the supercycle isn’t a spike — it’s a multi-year reset. And it’s betting accordingly.

IX. Porter's Five Forces & Hamilton's Seven Powers Analysis

Threat of New Entrants: LOW

The simplest way to understand this market is that the club is tiny. Only about ten companies worldwide can manufacture 765 kV transformers at all. And that capability isn’t something you can buy off the shelf. Ultra-high-voltage transformer manufacturing takes decades of accumulated know-how, immense capital, and a maze of quality testing and certifications that can’t be rushed.

Even the post-pandemic supply imbalance isn’t the full story. Lead times keep stretching because many components are custom and can only be made by specialist suppliers. And transformer plants don’t print money on day one. If it can take years or even decades to break even, most would-be entrants simply won’t take the leap.

Then there’s the part almost nobody appreciates until they have to do it: these machines aren’t mass-produced commodities. They’re designed, built, tested, and certified unit by unit. And after you build one, you still have to move it. Large power transformers can weigh well over 100 tons, sometimes far more, and shipping them often requires specialized transport equipment—down to a limited number of super-heavy-load railcars. The logistics alone can add months to a replacement project, even after the transformer is finished.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers: MODERATE

Transformers are basically engineered metal and chemistry. Key inputs include copper, steel, and specialty insulating oils, and the supply chain is concentrated in ways that matter. For example, transformer cores rely on grain-oriented electrical steel—steel with the magnetic properties required for efficient power transfer—which is made domestically in the U.S. only by Cleveland-Cliffs. Meanwhile, large transformers have historically been heavily imported, including from Mexico, China, and Thailand.

HD Hyundai Electric has shown it can maintain solid operating margins even when copper prices rise. In a tight, seller-driven market, much of that raw material inflation can be pushed through to customers.

Bargaining Power of Buyers: LOW (currently)

In normal times, utilities have leverage: they’re large, sophisticated, and they buy in volume. But these aren’t normal times.

HD Hyundai Electric’s internal data suggested it could take as long as five years to deliver the transformers already on order. To keep up, the company has been running its transformer plants in Korea and the U.S. at full capacity.

That’s what flips the negotiating table. In today’s seller’s market, manufacturers can raise average selling prices and still stay fully booked. Lead times for large power transformers have expanded dramatically—from what used to be measured in weeks to timelines that can run years—and prices have surged along with them.

Notably, major contracts are still getting signed even after the U.S. moved to apply a 50% tariff on imports in August. The reason is straightforward: when only a small number of suppliers can build the gear you need, and you need it urgently, technological scarcity overpowers policy friction.

Threat of Substitutes: VERY LOW

There is no practical substitute for a power transformer in grid-scale transmission and distribution. Electricity typically passes through multiple transformers on its way from generation to end-user; remove them, and the grid doesn’t just get less efficient—it stops working.

Yes, there are early-stage alternatives like solid-state transformers. They promise smaller size and better efficiency, and they may eventually help on certain parts of the supply chain. But they’re still years away from being commercially viable at true grid scale. For the foreseeable future, conventional transformers remain essential and irreplaceable.

Competitive Rivalry: MODERATE-HIGH

The prize is big enough that everyone is leaning in. North America’s Delta Star and Pennsylvania Transformer Technology are expanding. Global incumbents like Hitachi Energy and Mitsubishi Electric in Japan, and Siemens Energy in Germany, are pushing investment to capture more of the U.S. market.

And the U.S. market remains structurally dependent on imports. Alongside HD Hyundai Electric, other major global suppliers—Hitachi Energy, Siemens, Mitsubishi Electric, and GE—continue to serve U.S. demand. Together, these players account for a substantial share of the global power equipment landscape, and they’re all fighting for position in what’s become the most capacity-constrained market in the world.

Hamilton's Seven Powers Analysis:

Counter-Positioning: The 1980s government ban that forced Hyundai to go global wasn’t just a hardship—it was an origin advantage. While domestic competitors stayed comfortable serving the home market, HD Hyundai Electric built export-first capabilities: global sales, international certifications, and long-lived customer relationships across regions. That’s counter-positioning in its cleanest form: a model incumbents struggle to copy because it would undermine their existing, profitable ways of operating.

Scale Economies: HD Hyundai Electric can produce up to 120,000 MVA of transformers per year in Korea—the largest capacity in the country. In transformer manufacturing, scale isn’t about flooding the world with units; it’s about spreading massive fixed costs—test bays, specialized equipment, and highly skilled engineering labor—across more output. Higher throughput supports competitive pricing while protecting margins.

Process Power: This is a craft industry disguised as heavy manufacturing. Decades of refinement, strict quality systems, and certifications (including ISO9001, Canadian standards, and UL certification) create advantages that don’t transfer quickly to new entrants. Since entering the transformer market in 1978, the company has built deep process discipline and a reputation for high-quality manufacturing, supplying more than 1.2 million MVA to 70 countries worldwide.

Switching Costs: Utilities don’t treat transformer vendors like interchangeable suppliers. Qualification, certification, and trust take time—and failure is unacceptable. One bad transformer can mean an outage measured in cities, not neighborhoods. That risk creates powerful switching costs: proven reliability matters more than shaving a bit off the purchase price.

Cornered Resource: Ultra-high-voltage engineering talent is scarce, and 765 kV capability is rarer still. With only about ten manufacturers worldwide able to produce 765 kV transformers, HD Hyundai Electric’s decades of accumulated expertise—and its track record of more than 160 765 kV contracts since 1999—functions like a cornered resource. You can’t hire your way into that position quickly.

Network Effects: Limited here. Transformer manufacturing doesn’t compound through user-to-user adoption the way software does.

Branding: In this industry, “brand” means earned trust under extreme consequences. By 2017, HD Hyundai Electric had shipped more than 1.2 million kWA transformers to 70 countries. It ranks first and second in ultra-high-voltage transformer market share in the United States and Saudi Arabia, respectively. That reputation capital takes decades to build—and in a supply-constrained world, it becomes a competitive weapon.

X. The Competitive Landscape & Market Dynamics

Zoom out, and the competitive landscape starts to look less like a crowded marketplace and more like a short guest list.

Globally, there are only a small number of manufacturers that can reliably build and deliver large power transformers—especially at the very top end of voltage and capacity. Each major player has its own edge, often shaped by decades of field experience, proprietary process know-how, and where they already have factories and service networks.

Hitachi Energy is the obvious heavyweight. It offers a full range of power transformers and related components, and it has shipped more than 20,000 units worldwide. That includes ultra-high-voltage installations, from 800 kV UHVDC projects to hundreds of 735–765 kV AC units delivered across the major global markets.

ABB is another incumbent with deep roots. Over roughly 120 years, it has grown into one of the largest transformer manufacturers and service providers in the world, operating across more than 100 countries with a large manufacturing footprint and global service coverage.

In Korea, Hyosung Heavy Industries is the closest peer. It developed a 154 kV transformer in 1969 and has since built capability all the way up to 765 kV. It supplies ultra-high-voltage transformers at large ratings and offers both core form and shell form technology. With project experience across more than 70 countries and thousands of units shipped from its Changwon plant, Hyosung has earned its place as a global transformer brand.

India’s CG sits in the same rare tier. It ranks among the top 10 transformer manufacturers globally and is one of the few that designs and manufactures a broad range of power and distribution transformers and reactors, spanning small distribution units all the way up to 765 kV-class equipment.

In other words: the top end of this industry is defined by incumbency. Not because customers love incumbents, but because the cost of failure is unacceptable and the lead time to build credibility is measured in decades.

That incumbency is getting even stronger in today’s market. Virginia Transformer, the largest U.S.-owned transformer manufacturer, described the current shortage as a “perfect storm,” where post-pandemic pent-up demand turned into a “big tsunami” across basically every segment—energy, bitcoin mining, and artificial intelligence. “I’ve never seen a market dynamic like this,” the company said.

The downstream effects are now showing up in project schedules. Based on conversations with developers and suppliers, as much as 25% of global renewable projects could be at risk of delays due to transformer lead times. In a market like that, the bottleneck isn’t demand. It’s production capacity—and the burden shifts to the manufacturers who can actually deliver.

Inside that context, HD Hyundai Electric’s advantages become clearer:

- Geographic positioning: with manufacturing in both Korea and Alabama, it can serve U.S. customers while partially insulating itself from tariff volatility.

- Ultra-high-voltage expertise: proven 765 kV capability puts it in a very small global club.

- Order backlog visibility: multi-year contracts provide unusually strong forward revenue clarity.

- Vertical integration plans: moving into circuit breakers and broader distribution equipment creates cross-selling opportunities and deepens relationships with utilities.

As one HD Hyundai Electric official put it, “With the acquisition of UL certification, we plan to expand our presence beyond high-voltage transformers — where we have consistently held the top market share in North America — into the broader power distribution equipment sector, including low- and medium-voltage circuit breakers.”

XI. Leadership Transition & Future Outlook

As HD Hyundai was riding the transformer boom, it was also preparing for something just as consequential, but far less visible from the outside: a handoff of power.

After an earlier-than-expected year-end executive reshuffle, the group promoted Chung Ki-sun—one of the grandsons of Hyundai founder Chung Ju-yung, and the eldest son of Chung Mong-joon, the group’s largest shareholder and honorary chairman of the Asan Institute for Policy Studies.

Chung Ki-sun was born in 1982. He joined Hyundai Heavy Industries in 2009 as an assistant manager, then went to the United States for further study. After graduating from Stanford Graduate School of Business, he spent two years at a global consulting firm before returning to Hyundai Heavy Industries in 2013 as a senior manager.

Inside the group, he has built a track record around two themes: creating new profit pools and pushing through big, complicated moves. He led the establishment of HD Hyundai Marine Solution in 2016 and grew it into a core business, with a market capitalization of 11 trillion won. In 2021, he spearheaded the acquisition of Doosan Infracore, helping elevate construction machinery into a key pillar for the group. He has also been credited with strengthening the group’s foundation for growth while helping manage through the shipbuilding downturn that lasted more than a decade.

On paper, his résumé reads like a bridge between old Hyundai and new: an economics degree from Yonsei University, an MBA from Stanford, and a public profile that’s more modern than the generations before him—mixing shipyard pragmatism with the polish of a tech-era executive.

The timing matters. Chung’s promotion landed alongside a broader restructuring push across HD Hyundai. The group planned to merge HD Hyundai Heavy Industries and HD Hyundai Mipo in December 2025, and to combine HD Hyundai Infracore and HD Hyundai Construction Equipment early the following year under HD Construction Equipment. The goal is to tighten the two core pillars—shipbuilding and construction machinery—into stronger, more globally competitive platforms.

XII. Key Performance Indicators & Investment Considerations

If you’re trying to underwrite HD Hyundai Electric as an investment, there are endless metrics you can track. But two tell you the most, the fastest—because they capture the two things that matter most in a supply-constrained, long-lead-time industry: demand visibility and pricing power.

1. Order Backlog (measured in billions USD): This is the company’s clearest window into the future. Backlog isn’t a “hope” metric; it’s signed work waiting to be built. HD Hyundai Electric’s order backlog reached $6.55 billion, up nearly 25 percent from a year earlier. When backlog is growing, it usually means the company is winning the right projects, maintaining delivery credibility, and holding pricing power. When it starts shrinking, that can be an early warning that demand is cooling or competitors are taking share.

2. Operating Profit Margin (%): This is the scoreboard for execution. In the first quarter of 2025, operating profit margin climbed to 21.5%. In a seller’s market—where customers are fighting for production slots—margins should expand. If they compress, it typically means one of two things is happening: input costs are rising faster than pricing, or the competitive environment is tightening.

Material Considerations:

Regulatory and Trade Policy: This company has lived the consequences of trade policy firsthand. At its peak, HD Hyundai Electric faced a tariff of 60.81% in the United States. The Alabama manufacturing footprint helps reduce that exposure, but it doesn’t make the risk disappear—especially if rules shift again or expand to cover more of the supply chain.

Supply Chain Concentration: Transformers look like metal boxes, but they’re built on a handful of highly specialized inputs. Grain-oriented electrical steel is a good example—critical for transformer cores, and sourced from a limited set of global suppliers. In a market where demand is surging, even small disruptions here can cap output no matter how strong the order book looks.

Capital Intensity: Meeting demand requires spending real money, years before the revenue shows up. The company’s expansion plan calls for 400 billion won in investment—about 56% of its operating profit for 2024 and more than its 2023 operating profit of 315.2 billion won. It’s the largest investment HD Hyundai Electric has made since its origins in 1977. The upside is obvious: more capacity in the middle of a supercycle. The risk is equally straightforward: this is a business where big bets take time to pay back.

Cyclicality Risk: Today’s demand story reads as structural—aging grid replacement, renewables buildouts, and data center load growth. But industrial equipment has a long history of overshooting. If you look at other “energy transition” supply chains like lithium or solar modules, you can see how quickly a scarcity-driven boom can turn into a glut. The transformer market’s barriers are higher, but the lesson still applies: capacity expansions across the industry can eventually reset pricing power.

Technology Disruption: Solid-state transformers are an emerging technology that could eventually take share in certain applications. The company expects SSTs could replace a portion of the data center transformer market and could be worth up to $1 billion by 2030. That’s not a near-term threat to today’s backlog—but it is a long-term factor worth tracking, especially as data centers push for higher efficiency and more compact power architectures.

XIII. Conclusion: The Accidental Moat

HD Hyundai Electric’s journey—from government-mandated exile to global power equipment leader—offers lessons that reach far beyond transformers.

This company wasn’t originally designed to be an export champion. It was shoved into that identity by forces outside its control. And yet, the discipline required to compete globally early—meeting tougher international standards, building customer relationships across regions, and mastering the logistics of shipping 200-ton machines—hardened into an advantage that never really went away.

That 1980s “punishment” became the company’s operating model. A decade locked out of the domestic market forced Hyundai Heavy Electric to cut to the bone and rebuild around exports. The result is the same structural reality today: roughly 70% of HD Hyundai Electric’s sales come from overseas.

Now layer in the moment we’re living through. After decades of flat load growth in the U.S., electricity demand is rising again as AI and data centers, industrial onshoring, and transportation electrification converge. At the same time, much of the grid is aging—about 70% of U.S. power grid transformers are 25 years or older. And transformer lead times have stretched from roughly 50 weeks in 2021 to around 120 weeks on average in 2024.

So yes—the supply-demand imbalance is real. The moats are real. The backlog creates multi-year visibility.

But the deeper story isn’t timing. It’s what happens when adversity forces a company to build muscles it never would have built by choice. It’s the compounding of technical expertise over decades, and the uncomfortable truth that in an economy obsessed with software, the world still runs on physical infrastructure that can’t be willed into existence overnight.

The transformers HD Hyundai Electric builds will likely outlast the data centers they serve, the servers they feed, and maybe even the AI models those servers run. They’re quiet, boring, essential pieces of modern civilization.

And someone has to build them.

Increasingly, that someone is HD Hyundai Electric.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music