Chalco: The Metal Behind the Dragon

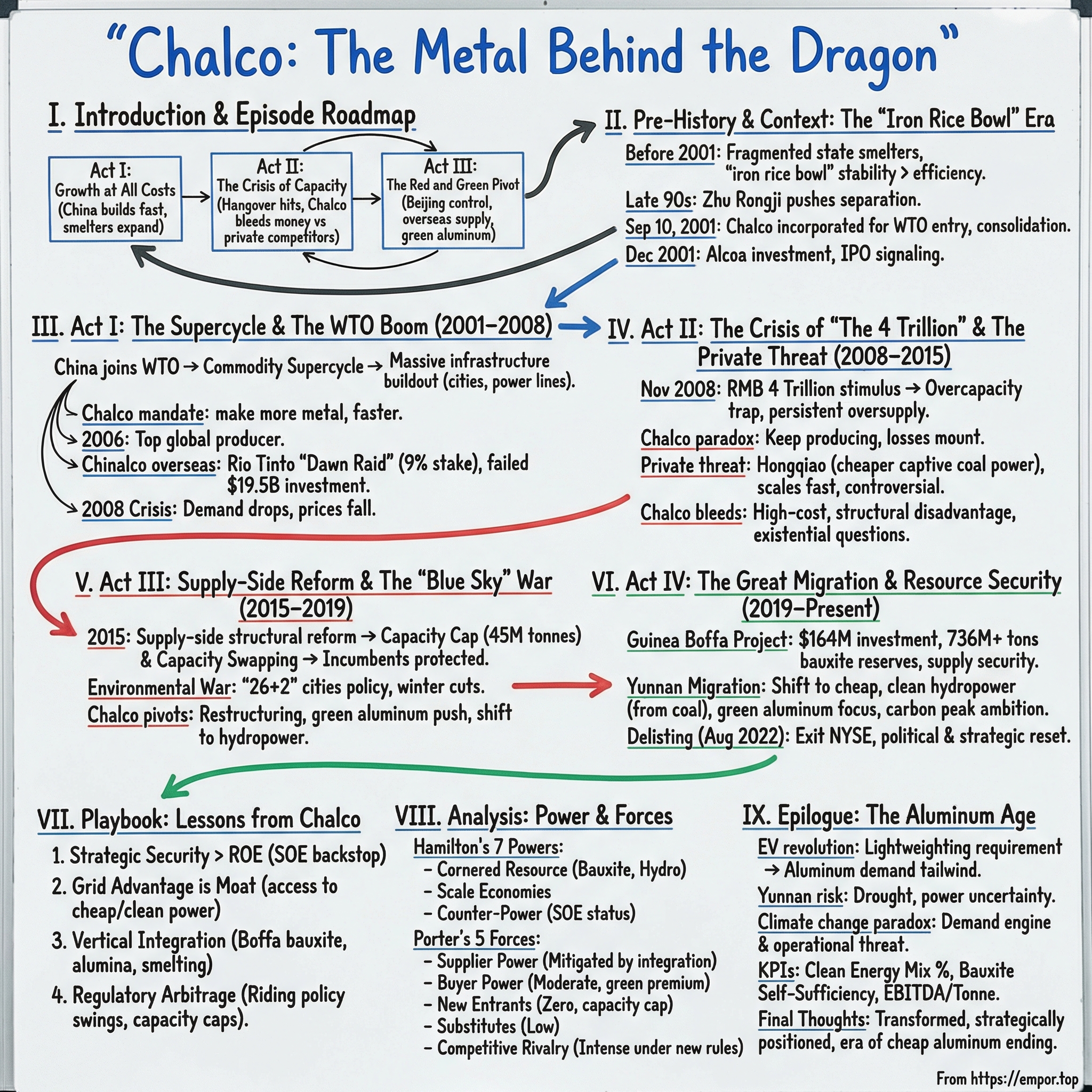

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

The lights flicker in Shenzhen. Somewhere on a factory floor, robotic arms stitch together the aluminum frame of an electric vehicle—the lightweight skeleton that helps push a car hundreds of kilometers on a charge. In a high-rise apartment in Shanghai, someone cracks open a can of Tsingtao, the aluminum tab snapping back with a familiar hiss. On a construction site in Chengdu, workers fasten aluminum window frames into a tower that will soon hold thousands of lives.

These scenes have an invisible common link: a metal so ordinary, so everywhere, that we rarely stop to ask where it comes from.

Aluminum has a famous nickname: “congealed electricity.” It’s not poetry. It’s chemistry and power bills. Turning bauxite into aluminum takes an astonishing amount of energy—on the order of about 13,500 kilowatt-hours for a single tonne. Enough to keep an average American home running for roughly 15 months. In aluminum, electricity isn’t just an input; it’s the whole game. Where power is cheap, smelters thrive. Where power is expensive, they go dark and rust.

That one truth has shaped the industry for over a century. And nowhere has it played out more dramatically than in China.

By 2021, Aluminum Corporation of China Limited—Chalco—had become the world’s largest aluminum producer, edging past rivals like China Hongqiao Group, Rusal, and Shandong Xinfa. But this isn’t just the story of a company that got big. Chalco is the publicly listed champion tied to a far larger machine: its state-owned parent, the Aluminum Corporation of China, better known as Chinalco. The names are confusingly similar, and the relationship is intimate—but the roles are distinct. Chalco is the commercial face in the market; Chinalco is the state-backed mothership.

So when you study Chalco, you’re not just studying a miner or a smelter. You’re watching China’s industrial rise in miniature—from the red dirt of bauxite mines in Guinea to the hydroelectric dams of Yunnan, from Hong Kong boardrooms to the policy decisions that ripple out of Beijing.

This story is a three-act play:

Act One: Growth at All Costs. China builds, and builds fast. Every refinery runs hot. Every smelter expands. The mission is simple: feed a nation turning concrete and steel into cities.

Act Two: The Crisis of Capacity. Then the hangover hits. Chalco—carrying the weight of being a state champion—bleeds money as private competitors move faster, cheat smarter, and produce cheaper.

Act Three: The Red and Green Pivot. The present era: Beijing tightens control, China goes overseas for secure supply, and the industry migrates toward hydropower to produce “green aluminum” for a decarbonizing world.

This is the story of how a company born out of the old planned economy became one of the defining industrial players of the 21st century—and what that transformation reveals about commodities, climate policy, and the direction of China’s ambitions.

II. Pre-History & Context: The "Iron Rice Bowl" Era

Before 2001, there was no Chalco. There was only the Chinese state’s industrial machine—especially the Ministry of Metallurgical Industry, which had effectively run the country’s aluminum production since the Mao era.

Picture a patchwork of state-owned smelters spread across provinces like Henan, Shanxi, Guizhou, and Shandong. Each plant was its own little kingdom, tied tightly to local officials, employing thousands of people who lived under the “iron rice bowl”: jobs and stability guaranteed for life.

Most of these facilities lagged far behind Western peers like Alcoa and Alcan. Modern efficiency wasn’t the point. Workers got paid whether the metal made money or not. “Shareholder return” wasn’t just irrelevant—it was almost ideologically suspect. The mandate was straightforward: keep producing aluminum for the country.

By the late 1990s, though, the limits of that model were getting harder to ignore. The Asian Financial Crisis in 1997 rattled confidence in state-heavy economic systems. And in Beijing, Premier Zhu Rongji—famous for being pragmatic, blunt, and willing to take political heat—pushed a fix that sounded simple on paper: separate the government’s job from the companies’ job. Let ministries regulate. Let enterprises compete.

That’s the environment Chalco was born into.

Aluminum Corporation of China Limited—Chalco—was incorporated in Beijing on September 10, 2001. The goal was consolidation: gather major state-owned aluminum assets under one roof and build a vertically integrated national champion in primary aluminum, strong enough to modernize a fragmented industry and feed demand that was already starting to surge.

The timing wasn’t subtle. China’s WTO entry had been in the works for more than fifteen years, and the finish line was weeks away: December 11, 2001. Creating Chalco was part defensive move, part declaration. If China was about to open itself to global competition, its aluminum industry needed a single, scalable player built for that world. Chalco began with core assets drawn from producers in places like Shandong, Shanxi, Henan, Lanzhou, and Guizhou.

The corporate structure was the tell. Chinalco—the parent—remained wholly state-owned, overseen by SASAC. Chalco—the operating company—would be the outward-facing vehicle, able to raise capital and, just as importantly, import credibility. It was China’s way of saying: we can play on international terms, while still keeping strategic control at home.

In 2002, Chalco went public in Hong Kong, raising about $1.3 billion. The dual listing—Hong Kong first, then New York later—wasn’t just about money. It was about signaling. Western capital. Western scrutiny. Western standards. In exchange, investors got a stake in what was quickly becoming the center of gravity for global industrial demand.

But here’s the distinction that matters, and it’s easy to miss if you’re used to reading Western mining-company stories: Chalco wasn’t designed to maximize shareholder value above all else. Profit mattered, yes. Competitiveness mattered, absolutely. But the primary mandate was security of supply. China was about to consume more metal than any nation in history, and Chalco was built to make sure the country never had to worry about running short.

Even the early shareholder roster reflected that bridging intent. In December 2001, Alcoa agreed to buy shares in Chalco’s initial global offering at the IPO price—enough to represent 8.0% of the company immediately after the offering. The message was clear: this wasn’t a closed domestic rearrangement. This was China inviting the world in, borrowing legitimacy and know-how from the industry’s most established name.

It felt like the dawn of a new era—one where China would open the door to global markets and global partners.

What no one could have predicted was just how far that door was about to swing.

III. Act I: The Supercycle & The WTO Boom (2001–2008)

December 11, 2001. China joined the World Trade Organization, and the country’s industrial engine suddenly had a direct on-ramp to global trade.

What followed was the kind of run that, in hindsight, gets its own name: the commodity supercycle. For most of the 2000s, the world didn’t just experience “strong demand.” It watched China attempt the biggest infrastructure buildout in modern history—highways, bridges, airports, power plants, ports, and entire skylines rising at once.

And aluminum was everywhere in it. Window frames in new towers. Power lines stretching from massive dams. Consumer electronics casings rolling off assembly lines. As China’s appetite grew, Chalco’s job was simple to describe and brutal to execute: make more metal, faster.

By 2006, Chalco ranked among the top global aluminum producers, reporting about 3.1 million tonnes of primary aluminum production that year. In this period, Chalco benefited from what was effectively a near-monopoly position in China’s aluminum industry. The hard part wasn’t selling—customers were waiting. The hard part was building enough mines, refineries, and smelters to keep up.

The boom showed up clearly in the company’s scale. By 2010, Chalco reported revenue of $21.5 billion and production capacity above 4 million tonnes of aluminum. But even before that point, the direction was already set: China’s aluminum consumption was rising at double-digit annual rates, and Chalco was the state-backed vehicle expected to supply it.

While Chalco was busy sprinting inside China, its parent company was thinking about the supply chain outside China.

In February 2008, Chinalco teamed up with Alcoa to buy roughly a $14 billion stake in Rio Tinto—China’s biggest overseas investment at the time. The move quickly became known as the “Dawn Raid”: a fast, surprise purchase that vaulted Chinalco to about 9% ownership in one of the world’s most important mining companies, right in the middle of a takeover fight. BHP Billiton was trying to buy Rio, and Beijing hated what that would mean: an even more powerful Western mining bloc with outsized control over key resources, especially iron ore flowing into China.

For Chinalco, this wasn’t just financial engineering. It was a statement of intent. If China was going to be the world’s largest industrial consumer, it couldn’t afford to be a price taker forever. It wanted influence upstream—on the resources themselves.

That ambition escalated. In a deal announced February 12, 2009, Chinalco proposed investing $19.5 billion in Rio Tinto, a move that would have made China’s state aluminum champion a major owner inside a crown-jewel Western miner.

It didn’t happen. The proposal was rejected, amid regulatory concerns in Australia and a sharp recovery in Rio Tinto’s share price that shifted the economics. In China, it landed as a public, geopolitical kind of no. But it also clarified something that would matter more and more as the decade went on: China’s resource companies were no longer content to simply produce domestically. They wanted to secure and shape global supply.

Then, just as the 2000s boom felt unstoppable, the floor fell out.

By the end of 2008, the global financial crisis had hit. Lehman collapsed. Credit froze. Aluminum prices dropped hard. The supercycle suddenly looked a lot less like a new normal and a lot more like a party that had just ended.

What came next would define Chalco’s fate for the following decade.

IV. Act II: The Crisis of "The 4 Trillion" & The Private Threat (2008–2015)

November 9, 2008. Beijing reached for the biggest lever it had.

The State Council announced a stimulus plan that, in headline terms, totaled RMB 4 trillion—roughly US$586 billion at the time—designed to blunt the impact of the Great Recession. While much of the West was cutting capacity and shedding jobs, China did the opposite: it poured money into infrastructure to keep growth humming, employment steady, and social stability intact.

On the surface, it worked. Growth, which had sagged toward 6% by late 2008, rebounded back into double digits by mid-2009.

But for Chalco, the stimulus created a brutal paradox: China needed more building, which meant more metal, but the aluminum industry was already drowning in capacity.

By 2008, China had built out enormous primary aluminum capacity, and a meaningful chunk of it sat idle. Utilization was weak, prices were falling, and the economics were upside down. In 2009, Chinalco—the country’s largest aluminum producer—reported a loss of 4.6 billion yuan as oversupply pushed prices down.

This is the trap door built into the DNA of a state-owned enterprise. A private competitor can respond to low prices the way Economics 101 says it should: cut output, shelve expansion, protect cash. Chalco didn’t have that luxury. It faced pressure to keep plants running, keep workers employed, and keep provincial GDP targets on track. Easy credit and policy urgency effectively delayed the hard decision to shut outdated capacity. The industry kept producing into a glut—and the glut became a feature, not a bug.

In hindsight, the stimulus era also planted longer-term problems: persistent overcapacity, heavier local-government debt burdens, and a financial system taking on more risk to keep the machine moving.

And right in the middle of that, a new competitor emerged—one that played by different rules.

Shandong entrepreneur Zhang Shiping didn’t start in metals. He founded Shandong Hongqiao in 1994 as a denim business. But by the early 2000s he saw a bigger opportunity: aluminum, the material China couldn’t get enough of. Hongqiao began its aluminum operations in 2001, fueled by abundant domestic credit and a decision that would become its signature advantage: building its own coal-fired power plants.

In aluminum, power is destiny. Electricity can represent roughly 40% of production cost. Chalco largely bought electricity from the state grid at prevailing rates. Hongqiao put generation right next to the smelters—captive power, captive economics. The result was simple and devastating: Hongqiao could often make metal more cheaply than the state champion could.

It scaled fast. By 2007, its annual capacity had reached about 300,000 tonnes. In 2011, Hongqiao raised US$2.2 billion in a Hong Kong IPO, and its licensed capacity pushed past one million tonnes.

This is where Act II stops being a macro story about stimulus and becomes a knife fight. The nimble private wolf versus the heavy state giant.

Hongqiao’s speed came with controversy. Rapid expansion repeatedly put it at odds with regulators, and it operated in the gray zones that aggressive private players are willing to explore—whether that meant environmental loopholes, questionable approvals, or sourcing bauxite under terms that a marquee SOE could not easily match. Years later, in 2017, officials ordered the closure of two million tonnes of unapproved smelting lines as part of a national campaign against illegal capacity—an echo of how far and fast Hongqiao had run.

Meanwhile, Chalco bled.

As global aluminum prices weakened, Chalco fell into losses—reporting a US$530 million loss at one point in the period—and tried to respond by cutting production amid oversupply. But the deeper problem wasn’t just cyclical pricing. It was structural disadvantage. Competitors with cheaper power and more flexible operations could stay profitable when Chalco couldn’t.

At the worst of it, analysts were openly questioning whether the business could sustain itself. Citi estimated that across bauxite, alumina, and aluminum, Chalco’s operations were losing money—and that those losses could erase a meaningful slice of equity value.

That’s the existential question that hung over the entire industry: can a giant SOE actually compete?

Chalco did what it could. It began restructuring high-cost smelting, cutting loss-making operations, consolidating coal and power assets, and leaning harder into upstream supply—positioning itself for overseas bauxite as the next phase of the battle.

But the real turning point wasn’t going to come from one company’s operational tweaks. The market was too broken, and the incentives were too political.

The answer would come from Beijing—by changing the rules of the game.

V. Act III: Supply-Side Reform & The "Blue Sky" War (2015–2019)

By 2015, China’s leaders had finally said out loud what the market had been yelling for years: the industrial economy was drowning in overcapacity. Steel mills were churning out product with no profitable home. Cement plants sat half-idle. And aluminum smelters—many coal-fired, many operating with shaky approvals—helped turn northern winters into a gray-brown haze.

Beijing’s answer came out of the 2015 Central Economic Work Conference, wrapped in a technocratic phrase that would soon change everything: “supply-side structural reform.” The idea was deceptively simple. Stop trying to juice demand. Start fixing supply. Cut the excess. Let “zombie enterprises” die. And, crucially, stop rewarding anyone who could build faster than the regulators could chase.

Aluminum got a hard line in the sand. China first established production limits in 2017 as part of the broader reform push to rein in overcapacity and pollution. The cap—45 million tonnes—was then maintained through successive five-year plans and industrial policies, with enforcement getting tighter over time.

This was the moment that saved Chalco.

The clever part wasn’t just capping the total. It was how the cap was enforced. China introduced capacity-swapping: a system where capacity effectively became a permit you could trade. If you wanted to build a new smelter, you couldn’t just pour concrete and plug into the grid. You had to buy quota from a smelter that was shutting down. Overnight, the industry stopped being an open race and became a closed club. New entrants were boxed out, and incumbents suddenly held something valuable: licenses to produce.

By the end of 2019, more than seven million tonnes of capacity quotas had changed hands. In practice, the swaps tended to move paper capacity out of higher-cost regions like Henan and Guizhou and into places like Inner Mongolia and Yunnan, where electricity was cheaper. Because much of the swapped capacity came from high-cost idle plants, near-term production didn’t spike—but the market finally got what it had been missing: a floor.

For Chalco, this was a lifeline. In a world where permits were scarce, its existing capacity quotas became an asset it could redeploy, transfer, or use to upgrade into more efficient facilities. Supply-side reform didn’t just stabilize pricing. It structurally favored the big, legacy players—and made it far harder for a new Hongqiao-style blitz to happen again.

At the same time, Beijing opened a second front: the environmental war.

The “26+2” cities policy targeted the coal-heavy industrial belt in the north and mandated winter production cuts when air pollution was at its worst. Aluminum smelting is electricity in physical form, and coal power meant scrutiny. Hongqiao—built on captive coal-fired generation—felt that pressure directly. In response, it closed smaller power units, increased purchases of hydro and solar power, and later announced a target of net-zero greenhouse-gas emissions before 2055, with carbon peaking planned before 2025.

Inside Chalco, the tone changed too. Under new leadership, the company pushed through restructuring that had been politically difficult in the stimulus years: higher-cost smelting was overhauled, losses were cut, coal and power assets were consolidated, and the company leaned harder into the upstream—preparing for a future where bauxite security mattered as much as smelting scale.

And that future was starting to come into focus.

Chalco wasn’t going to win a pure coal-smelting cost war against the fastest private operators. Its path was different: lock down overseas bauxite and shift production to provinces with abundant, cheap, clean hydropower. Ratings agencies and industry watchers began describing the same pattern across the sector: both Chalco and Hongqiao were rebasing or expanding in hydropower-rich regions, gradually loosening their dependence on coal.

The turnaround was real. But the most dramatic move—the great migration—was still ahead.

VI. Act IV: The Great Migration & Resource Security (2019–Present)

In a conference room in Conakry, Guinea, Chinese and Guinean officials signed paperwork that would quietly reshape the aluminum supply chain for decades. The documents described a bauxite mine called Boffa—a soft-sounding name for a hard strategic move.

Chalco, the listed arm tied to state-owned giant Chinalco, announced plans to invest $164 million in cash into the Boffa bauxite project. The deposit was enormous: at least 736 million tons of bauxite reserves, with the investment covering not just the mine itself, but the logistics that make a mine real—transportation links and port infrastructure.

Guinea was the obvious place to do this. The country holds the world’s largest bauxite endowment: proved reserves of about 7.4 billion tons, roughly a quarter of the global total, according to the U.S. Geological Survey. For years, much of it stayed in the ground, held back by the same bottlenecks that define resource frontiers everywhere: capital, technology, and the ability to move ore from inland red dirt to an ocean-going ship.

And the timing wasn’t an accident. Indonesia, once a major bauxite source for Chinese refineries, banned ore exports in 2014—then relaxed and later reimposed restrictions. The message to China’s aluminum industry was unmistakable: imported feedstock could be cut off by policy overnight. If aluminum is “congealed electricity,” bauxite is the dirt you have to secure before you can turn the lights on.

The Boffa project, under Chinalco’s Guinea buildout, was designed as a full system, not a single site. It carried headline reserves measured in the billions of tons, with exploitable resources estimated at about 1.75 billion tons and a planned mine life of around 60 years. Phase one alone called for roughly $585 million in total investment and a design scale of 12 million tons of high-quality bauxite per year. The blueprint included four linked components: a mining system, an independent power generation and supply system, a belt transport system, and a berthing terminal loading system.

Operations began on October 6, 2019. Then came the kind of milestone that tells you this wasn’t a speculative stake—it was steel in the ground. On April 6, 2020, the project’s belt conveying system completed heavy-load commissioning, setting a record for the longest single belt conveyor in Africa and establishing a benchmark for ultra-low energy consumption per ton of ore transported.

It’s worth picturing what that means in physical terms: a conveyor system stretching roughly 23 kilometers through Guinea, hauling bauxite from the mine to a dedicated terminal. From there, ships move it across oceans to feed refineries and smelters back in China. This wasn’t just resource extraction. It was supply security engineered end-to-end.

But bauxite was only half the pivot. The other half was even more consequential: changing where China smelts aluminum—and what kind of electricity that aluminum is “congealed” from.

As Beijing cracked down on coal-fired power to cut pollution, Chinese producers pushed hard to expand in Yunnan, where hydropower is abundant. A key move gave Chinalco access to Yunnan Aluminum’s 1.6 million tons of smelting capacity, with another 1.45 million tons in the pipeline or under construction.

Yunnan, in China’s southwest, is defined by water. River systems like the Pearl River and the Mekong and their tributaries drop out of high elevations, creating vast hydroelectric potential. That electricity is not only cheaper—often described as roughly half the cost of coal-fired power—but dramatically cleaner. Aluminum smelted with hydro carries a fraction of the carbon footprint of aluminum smelted on coal.

The impact on Chalco’s mix was material. Yunnan Aluminum was expected to add about 2.7 million tons of primary aluminum to Chalco on a full-year basis, roughly 70% of Chalco’s 2022 output. Following the acquisition, Chalco’s clean-energy mix was projected to rise significantly, to about 50% from around 20%. The company set an ambition to reach peak carbon by 2025.

The shift didn’t stop at reshuffling existing assets. In early 2024, Chalco commissioned a 400,000-tonne-per-year green aluminum smelter in Yunnan, powered entirely by hydropower. It was positioned as part of China’s broader decarbonization push, replacing older coal-fired capacity.

This is the product global buyers increasingly want. Apple, BMW, and Tesla all have sustainability commitments that force them to measure, document, and reduce emissions across their supply chains. Aluminum made with Yunnan hydropower—with credible certification and traceability—can command a premium versus coal-powered metal from northern provinces like Shandong. Chalco’s bet was straightforward: if the world is going to price carbon, then the cheapest aluminum won’t be the one with the lowest labor cost. It’ll be the one with the lowest emissions.

The industry-wide energy shift shows the direction of travel. Around 2015, thermal power accounted for roughly 89% of the energy used by aluminum smelters in China, with hydropower around 10%. More recently, thermal power fell to around 74%, while hydro rose to around 19%, alongside growing adoption of solar and wind.

The emissions gap is even more stark. Scope 2 emissions from aluminum smelters in Yunnan were estimated around 0.7 tonne per tonne of aluminum produced, compared with more than 11 tonnes of CO2 per tonne in coal-heavy northern provinces like Shanxi. Same metal. Different electricity. A radically different carbon bill.

Then came the delisting—the move that, more than any press release, marked how much the era had changed.

On August 12, 2022, Chalco announced it had notified the New York Stock Exchange of its proposed application for voluntary delisting of its American depositary shares.

It wasn’t just Chalco. Around the same time, five major Chinese state-owned enterprises—including PetroChina, Sinopec, Chalco, and China Life Insurance—announced plans to delist from the NYSE. Chalco’s stated rationale focused on practicalities: limited ADS trading volume compared to global H-share volume, and the administrative burden and cost of maintaining a U.S. listing and Exchange Act reporting requirements. The board approved the move.

The explanation was plausible, but the choreography mattered. Multiple SOEs making the announcement on the same day strongly suggested this was not merely a set of independent corporate decisions. The backdrop was the Holding Foreign Companies Accountable Act, which put Chinese issuers under growing pressure to meet U.S. audit inspection demands or face forced delisting.

Beijing was never likely to accept U.S. audit access into the inner workings of its most important state enterprises, especially in sectors with national-security sensitivity. And with these SOEs seeing relatively light U.S. trading anyway, the exit was less a financial blow than a political and strategic reset.

For Chalco, the delisting landed as something more symbolic than operational: a quiet declaration that it no longer needed Western capital—or Western markets’ approval—to fund its future. The center of gravity had moved home, to Hong Kong and Shanghai, where the investors—and the regulators—already understood the real mandate.

VII. Playbook: Lessons from Chalco

So what should investors take away from Chalco’s first quarter-century? A few rules keep showing up—sometimes the hard way.

1. Strategic Security Trumps Return on Equity

This is the core concept behind most big Chinese SOEs, and it’s where Western instincts can misfire. Chalco was set up as the main commercial arm of Chinalco, folding in the operational assets and revenue engines while remaining, by design, under the state’s influence through Chinalco and SASAC.

That structure explains almost everything that looks “irrational” on a spreadsheet. Chalco’s job is to make sure China doesn’t run short of aluminum. Profit matters more today than it used to—management watches margins, dividends exist, and investors do get paid—but supply security comes first. That’s why, in the worst years of overcapacity, Chalco kept producing when economics said it should shut pots. The state didn’t want the country’s flagship producer to go dark, and it definitely didn’t want mass layoffs.

For investors, this cuts both ways. It creates the SOE discount—a lower valuation multiple than nimble private peers. But it also comes with a different kind of backstop: if Chalco stumbles, it is far more likely to be stabilized than abandoned. The state won’t let it die.

2. The Grid Advantage is the Real Moat

If you want a single lever that determines winners in aluminum, it’s power. Electricity is roughly 40% of production cost, and that makes the industry less about mining bravado and more about who can secure the cheapest, most reliable electrons.

Chalco is positioned for the transition because it can plug into the system in a way most private players can’t. Its relationship with the state grid, access to hydropower quotas in Yunnan, and integration with State Grid Corporation combine into a structural edge—especially in a country where you can’t just build new smelting capacity wherever you want. Chalco is set to ramp up Yunnan Aluminum, which is positioned as China’s largest green aluminum producer, and that move isn’t just “ESG.” It’s cost, stability, and policy alignment rolled together.

This is Hamilton Helmer’s cornered resource in practice: preferential access to cheap, clean power in the one place the industry is being allowed to grow.

3. Vertical Integration is Survival

The Guinea Boffa project is the clearest illustration of the second big truth: you can’t just be a smelter and hope the world delivers your inputs on time.

Boffa is sponsored by Chinalco to lock in a steady, long-term bauxite supply, built in stages with initial capacity expected at 12 million tons per year. That’s not a side project—it’s insurance against the exact kind of policy shock China faced when export rules changed elsewhere.

Zoom out, and you see the same logic up and down the chain. Chalco controls bauxite resources in Guinea, runs alumina refineries across China, operates primary aluminum smelters in Yunnan and beyond, and has pushed further into higher-margin downstream alloy products used in electric vehicles and packaging. The point isn’t complexity for its own sake. It’s resilience: fewer single points of failure when prices, politics, or logistics suddenly shift.

4. Regulatory Arbitrage as Strategy

Chalco didn’t just survive China’s policy swings—it learned how to ride them.

In the growth-at-all-costs era, the mandate was expansion, and Chalco expanded. In the environmental era, the mandate flipped, and Chalco pivoted into green aluminum, while capacity caps and quota swaps turned incumbency into an advantage. Where earlier policy rewarded anyone who could build fast, later policy punished exactly that behavior—and protected players who already held permits.

The latest signals point to China maintaining its 45 million ton cap through at least 2027. That cap is not abstract. It’s a moat. No meaningful new competitor can enter the primary aluminum market without buying existing capacity quotas—and as a major incumbent, Chalco holds a meaningful share of what everyone else now needs.

VIII. Analysis: Power & Forces

Hamilton's 7 Powers Analysis

Cornered Resource: Chalco sits on two advantages that are hard to copy, no matter how aggressive a competitor might be. The first is bauxite. Through its Guinea position—anchored by projects designed to run for decades—Chalco can lock in feedstock security that smaller players simply can’t finance or replicate at scale. The second is electricity. Hydropower quotas in Yunnan aren’t just “cheaper power”; they’re access rights to a scarce, policy-favored energy source that defines who gets to grow in China’s next era of aluminum.

Scale Economies: Chalco is one of the biggest primary aluminum producers on Earth, with an estimated low-teens share of global output. That kind of scale matters in a business where margins can swing on tiny changes in power price, freight rates, and equipment uptime. As a top producer in China, Chalco can spread overhead across enormous volume, bargain harder with suppliers and logistics providers, and invest through downturns that would force smaller operators to retreat.

Counter-Power (The "8th Power"): This is where the SOE story breaks the standard Western playbook. Chalco has something private competitors don’t: the state’s implicit backstop, and a seat—via Chinalco and SASAC—close to the policymaking process that sets the rules for the entire industry. When Beijing puts a hard cap on capacity or enforces quota swaps, those policies tend to protect incumbents and stabilize the system. That isn’t about bribery or backroom dealing. It’s the logic of a system built around “national champions,” where industrial policy and corporate strategy are intertwined.

Porter's Five Forces Analysis

Supplier Power: Traditionally high, because aluminum is so energy-dependent. But Chalco has worked to blunt that risk by integrating upstream—securing bauxite supply and shifting a meaningful share of smelting toward hydropower in Yunnan. The more of the chain it controls, the less it’s exposed to sudden swings in key inputs.

Buyer Power: Moderate. Most aluminum is still a commodity, and big buyers can shop around. But the market is splitting. Low-carbon, traceable “green aluminum” is becoming its own tier, and that differentiation gives producers like Chalco more leverage—especially with customers such as Apple, BMW, and EV manufacturers that have to prove emissions reductions, not just promise them.

Threat of New Entrants: Effectively zero inside China. Since the production limits first landed in 2017, the 45 million tonne cap has held through successive policy cycles. No one can build meaningful new domestic smelting capacity without buying existing quotas. That’s a government-enforced barrier to entry—and it turns permits into a moat for incumbents.

Threat of Substitutes: Low for most major use cases. Aluminum’s mix of light weight, corrosion resistance, conductivity, and recyclability makes it tough to replace in aerospace, autos, power transmission, and packaging. Steel can take share in some construction applications, but it can’t match aluminum’s weight advantage where efficiency and performance matter.

Competitive Rivalry: Still intense, and it still centers on China Hongqiao, which has been a top-two global producer since 2015. The difference now is that rivalry happens under a tighter rulebook. With capacity caps and environmental enforcement bringing more discipline, the fight is less about who can build the most pots the fastest, and more about who can secure the best bauxite, the best hydropower access, and the most valuable premium customers willing to pay for verified low-carbon metal.

IX. Epilogue: The Aluminum Age

On a Tesla assembly line in Shanghai, robots fasten aluminum battery enclosures onto vehicle chassis. That’s the quiet shift inside the EV revolution: electric cars are, structurally, much more aluminum-heavy than the cars they’re replacing. Battery electric vehicles typically use multiple times the aluminum of non-BEVs for structural parts, because once you bolt a massive battery pack to the floor, every kilogram you can save everywhere else translates into range.

Automakers like aluminum for the same reason aerospace has for decades: it’s strong enough, light enough, and workable at scale. It’s one of the few levers you can pull to counter the weight of batteries without redesigning physics. And as the industry rolls out more electrified platforms, aluminum content per vehicle is expected to rise further through 2030.

This is the EV thesis for aluminum in one line: electrification turns lightweighting from an optimization into a requirement. As the world electrifies transportation—and builds the charging networks, grids, and renewable infrastructure to support it—aluminum demand has a built-in tailwind.

The auto industry already accounted for a meaningful share of global aluminum consumption in 2019, and demand is expected to grow sharply over the coming decades. Chalco sits directly in the blast radius of that trend. Its push into hydropower-based, lower-carbon “green aluminum” positions it for the premium tier of customers—automakers who don’t just want metal, but want metal that helps them hit emissions targets across the supply chain.

But there’s a risk that hangs over Yunnan’s smelters, and it’s as old as hydropower itself: drought.

Hydro is cheap and clean, but it’s seasonal. When rainfall disappoints, electricity tightens—and aluminum smelting doesn’t tolerate power uncertainty. In May 2021, water shortages hit electricity supply and forced about one-quarter of Yunnan’s aluminum plants to shut for months. A similar squeeze arrived in September 2022, when the Yunnan government ordered smelters to cut electricity use by 15% to 30%.

Yunnan’s dry season typically runs from November through April, and hydropower generation during that period can fall to well below wet-season levels. As more aluminum capacity migrates into the province, the same weather swing has a bigger impact. Rainfall isn’t just a talking point for commodity traders; it becomes a real operational constraint on the global supply of aluminum.

Climate change, in other words, is both the demand engine and the operational threat. EVs, grids, and renewables pull aluminum forward. Drought can take it offline. That’s the paradox Chalco has to navigate.

Key Performance Indicators to Monitor

For investors tracking Chalco, three KPIs are especially telling:

-

Clean Energy Mix Percentage: How much aluminum is produced using hydropower and other renewables versus coal-fired power. After the Yunnan Aluminum acquisition, Chalco’s clean-energy mix was projected to rise to around 50% from roughly 20%. A higher clean-energy mix generally means a lower carbon footprint, better positioning for premium customers, and less regulatory exposure.

-

Bauxite Self-Sufficiency Ratio: The share of bauxite sourced from captive mines—Guinea and domestic—versus external purchases. Higher self-sufficiency improves supply security and makes costs less vulnerable to policy shocks or market disruptions.

-

EBITDA per Tonne of Aluminum: A compact read on both sides of the equation: pricing power (including any premium for low-carbon metal) and cost control (especially power and logistics). In 2024, Chalco reported revenue of RMB 237,066 million, up 5.21% year over year, and net profit of RMB 12,400 million, up 85.38% from 2023—evidence of how fast profitability can rebound when the cycle, the cost base, and policy align.

Final Thoughts

Chalco’s transformation is real. It went from a lumbering state giant bleeding cash in the overcapacity years to something much more strategically positioned: a pillar of China’s green industrial push, anchored by three advantages that matter in aluminum. Long-life bauxite supply, hydropower access that can slash the carbon footprint versus coal-based competitors, and the policy connectivity that comes with being tied to the state’s national-champion system.

And the broader market backdrop is tightening. China has kept a hard cap on primary aluminum capacity at 45 million tonnes, and as output pushes closer to that ceiling, the pricing dynamic changes. In the old world, excess capacity was the governor—it kept prices from running. In the new world, constraints set the floor. Power availability, environmental enforcement, and hydropower seasonality start to matter as much as demand.

The era of cheap, abundant aluminum may be ending. For Chalco, that’s an opportunity—if it can keep securing bauxite, keep moving toward cleaner power, and keep its Yunnan footprint resilient to the weather. For everyone else, it’s a reminder of what the energy transition really is: not just a story about electricity, but a story about metal. And the companies that control the metal will help shape the industrial order of the twenty-first century.

Chat with

this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with

this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music