Kirin Holdings: From Yokohama's First Brewery to Japan's Health Science Pivot

I. Introduction: The Mythical Beast Transformed

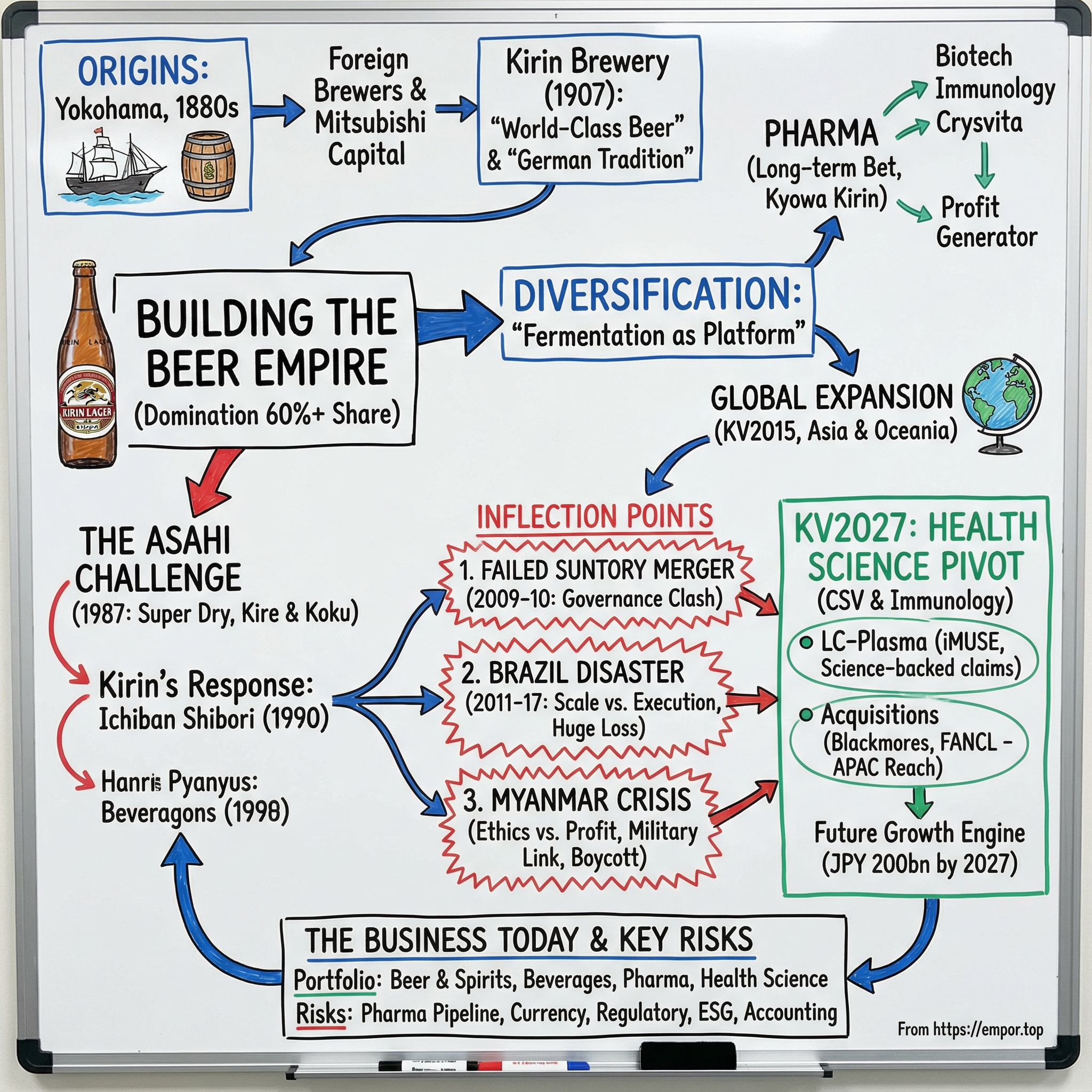

In Japanese tradition, the kirin is a mythical chimera said to appear only in times of peace and prosperity. It stands for wisdom, benevolence, and good fortune. For nearly 140 years, Kirin has carried that name—and that symbol. But the company behind it has shape-shifted again and again: from a single beer brand into a global portfolio that spans beer and beverages, pharmaceuticals, and a fast-growing health science business.

On paper, Kirin still looks like what most people think it is: a major Japanese brewer. It’s number two at home, with roughly a little under a third of the market, and it leads in Japan’s tax-driven “adjacent beer” categories like happoshu (low-malt) and the no-malt “new genre.” Zoom out further and you can place it among a familiar set of rivals—Asahi and Sapporo on one side, global beverage giants like AB InBev and Coca-Cola on the other—fighting in a crowded, mature, brand-heavy industry.

But that label—beer company—no longer explains what Kirin is trying to become.

Under its long-term management vision, Kirin Group Vision 2027, Kirin is betting that its real core isn’t beer at all. It’s fermentation, biotechnology, and immunology: capabilities that can be stretched from beverages into pharmaceuticals, and from there into health science products aimed at everyday consumer health. In Kirin’s telling, this is CSV—creating shared value—turning public health needs into growth markets, and turning a century-plus of know-how into a new engine for the next century.

And that’s where the story gets interesting, because the investor question is simple and brutal: can Kirin actually pull off this “bridge” from consumer products into pharma and wellness?

Plenty of famous companies have tried to cross that bridge and fallen into the water—consumer brands that wandered into pharmaceuticals or skin care and found out that “adjacent” on a slide deck doesn’t mean adjacent in the real world. Activist investors have pressed Kirin on exactly this point, asking for proof that the KV2027 strategy has working precedents, and for a clear explanation of why Kirin believes it can succeed where other household names couldn’t.

So this isn’t just the story of a brewery that got big. It’s a story of bold bets, painful failures, ethical controversy, and stubborn reinvention—and of whether fermentation, the ancient art of transforming one thing into another, can truly be a modern corporate platform… or whether Kirin has simply mistaken diversification for destiny.

II. Origins: Foreigners, Mitsubishi, and the Birth of Japanese Beer

Kirin’s origin story starts in a place that barely felt like Japan at the time: the treaty port of Yokohama. In the 1860s, it was a newly opened gateway where foreign merchants lived in designated settlements, bringing in Western goods, Western habits… and Western thirst.

Into that moment walked William Copeland, a Norwegian-American brewer who saw a straightforward opportunity in a complicated new country. In 1869, he founded the Spring Valley Brewery in Yokohama. Beer was still a novelty to most Japanese consumers—something you’d encounter through foreigners, not something you’d drink at home. But Spring Valley found its first customers in the expatriate community, and then, slowly, among Japanese drinkers curious about the tastes of the West.

The leap from a small foreign-run operation to the foundation of a Japanese institution came in 1885. That’s when the Japan Brewery Company, Limited—what would become the forerunner of Kirin Brewery—was established and took over Spring Valley’s assets. It wasn’t just a change of ownership. It was the moment beer in Japan started to scale.

And it didn’t scale on craft romance. It scaled on capital and connections.

In a deal brokered by Thomas Blake Glover, Japan Brewery was incorporated in Hong Kong in the name of W. H. Talbot and E. H. Abbott, backed financially by Japanese investors that included Iwasaki Yanosuke, then-president of Mitsubishi. This Mitsubishi tie would become one of the defining forces in Kirin’s corporate life. As a core member of the Mitsubishi Group, Kirin gained access to money, relationships, and the kind of institutional support that can turn a promising product into a national brand. It also inherited a certain way of operating: consensus, long horizons, and a preference for stability that, depending on the era, could look either like discipline or like drift.

By 1888, Japan Brewery began marketing Kirin Beer. The name itself carried double meaning: “kirin” can refer to a giraffe, but also to the qilin (麒麟), the mythical hooved creature said to appear only in times of peace and prosperity. It was an inspired symbol for a new consumer product in a country trying to define its modern identity.

In 1907, Kirin Brewery Company was established as a separate legal entity, purchasing the assets of Japan Brewery and expanding as consumer demand grew. And from the start, Kirin didn’t position itself as “local beer.” It positioned itself as world-class beer, made the world-class way: malted grains and hops imported from Germany, and German brewers overseeing production.

That insistence on German brewing tradition mattered. In an era when Japan was racing to match Western industrial standards, Kirin wasn’t just selling a drink. It was selling proof—bottled—that Japan could build products on par with the best in the world.

III. Building the Beer Empire: Dominance and the Asahi Challenge

For decades, Kirin ruled Japan’s beer market with something close to monarchical authority. From the 1960s through the mid-1980s, Kirin Lager wasn’t just a bestseller—it was the default. At its peak, Kirin held more than 60% of the market, while rivals fought over the remaining slice in the teens and low twenties.

Postwar economic growth turned beer from a treat into a routine. Salarymen streamed out of office buildings and into izakayas, and the first order was almost reflexive: “toriaezu biiru”—beer, for now. More often than not, that beer was Kirin Lager. It was safe, familiar, and everywhere.

Then, in 1987, Asahi cracked the spell.

Asahi Super Dry wasn’t merely a new label on the shelf. It was a shift in taste, and in vibe—lighter, sharper, more modern. Asahi had chased the answer through research and wrong turns, and landed on a beer built around two ideas that clicked with consumers: kire, that crisp snap of a clean finish, and koku, enough body to still feel satisfying. It hit like a cultural jolt, especially with younger drinkers who didn’t feel any particular loyalty to the “establishment” beer.

Kirin suddenly looked less like a national icon and more like your dad’s choice.

In the 1990s, Kirin tried to fight back with marketing—most memorably by putting Harrison Ford into a run of intentionally odd commercials, repeating “Kirin Lager kudasai” in various settings. The ads were loud. The underlying problem wasn’t.

Kirin’s real counterpunch arrived in 1990 with Ichiban Shibori—“First Press”—a beer positioned around purity and craft: only the first extraction from the brewing process. It was meant to go straight at Super Dry. Instead, it also pulled drinkers away from Kirin Lager, leaving Kirin fighting on two fronts: against Asahi, and against its own portfolio. The era of Kirin as an effortless 50%-plus share company was over.

Over time, the market settled into something like a two-giant rivalry, with Kirin and Asahi trading momentum. In 2020, Kirin edged past Asahi in Japan, taking a 37.1% share versus Asahi’s 35.2%—the first time since 2001 that Kirin had come out ahead.

But by then, the bigger issue wasn’t who was winning. It was what they were winning.

Japan’s beer market was shrinking, pressured by demographics, health consciousness, and a steady drift away from traditional full-malt beer. By 2024, volumes fell again—down about 2%—a small number that still points in one direction.

Japanese brewers responded the way you’d expect from a country where regulation shapes entire categories: they innovated around the tax code. Alcoholic beverages are labeled and taxed by malt content. To be “beer,” a drink needs at least 50% malt. Below that, it’s happoshu—low-malt beer—taxed more favorably. And below roughly a quarter malt, including products with no malt at all, you get the “third-category” or “new genre” drinks that became a mass-market staple.

This wasn’t just regulatory trivia—it was survival strategy. When consumers tightened belts, brewers could offer something beer-like at a lower price. And Kirin, in particular, became a standout in these tax-optimized segments, leading in the “new genre” category even as the definition of “beer” itself started to blur.

IV. Diversification: From Fermentation to Pharma

The seeds of Kirin’s current identity were planted decades ago, when management started asking a deceptively simple question: what if the thing we’re best at isn’t beer… it’s fermentation?

More than 40 years ago, Kirin pushed into pharmaceuticals, looking ahead to a future where Japan’s alcoholic beverage market might not grow forever. The bet was that the company’s strengths—fermentation, biotechnology, and genetic engineering—could be repurposed. Inside the company, it wasn’t an obvious move. For roughly the first ten years, it didn’t even make money. But Kirin stuck with it, and in 2008 that long, slow experiment took a definitive shape: Kirin Pharma merged with Kyowa Hakko Kogyo to form what became Kyowa Kirin.

The strategic logic was clean. Fermentation is biological manufacturing. Whether you’re brewing a lager or producing a therapeutic protein, you’re orchestrating living systems to make complex molecules at scale. Kirin’s researchers believed the muscle the company built running massive fermentation operations could translate into pharma.

And crucially, Kirin could afford to be patient. The beer business—still a cash engine—subsidized the pharmaceutical arm while it found its footing. That kind of timeline is hard to imagine in a company living quarter-to-quarter. Kirin’s structure and culture made it possible to run two plays at once: keep the core beverages machine humming, while incubating a second pillar that would take years to stand up.

Over time, that second pillar became real. Kyowa Kirin grew into a specialty pharmaceutical company with meaningful global products. In 2024, Crysvita and Poteligeo continued to expand—targeting rare diseases like X-linked hypophosphatemia and certain lymphomas, areas where deep biotech expertise matters more than mass-market branding.

Financially, the pharma business showed the shape you want to see in a maturing growth engine: revenue reached JPY495.6 billion, up 12% year over year, driven by growth in global products and technology revenues. Core operating profit was JPY95.4 billion, essentially flat.

For Kirin’s leadership, this was proof. The “fermentation as platform” idea wasn’t just a clever story—it had produced a real, scaled business. And that success is what set up Kirin’s next leap: trying to take the same underlying capability and build a third act in health science.

V. The Global Expansion Era: KV2015 and Betting Big Overseas

By the mid-2000s, Kirin could see the walls closing in at home. Japan’s demographics were turning from tailwind to headwind, and beer was no longer a growth category. So management reached for the most natural escape hatch a domestic champion can take: go abroad, and go where growth still looked alive—Asia’s emerging markets, plus the familiar, resource-rich, beer-loving economies of Oceania.

That ambition was formalized in Kirin Group Vision 2015. The goal was straightforward: become a leading company across Asia and Oceania, and do it with a comprehensive beverages strategy anchored in “food and health,” not just alcohol. In Kirin’s plan, Australia wasn’t a side quest. With Australasian revenues above A$5.6 billion, the region was positioned as a front-line growth engine for the whole group.

The flagship move was Australia and New Zealand—big, consolidated markets where a scaled operator could win. In September 2009, shareholders approved a full takeover by Kirin Holdings. A month later, in October 2009, Kirin combined two major assets into one platform: it bought the brewer Lion Nathan and merged it with National Foods, which Kirin had owned since 2007. The result was Lion Nathan National Foods, later known simply as Lion.

Lion became Kirin’s Oceania beachhead: beer and cider across Australia, alcohol distribution in New Zealand, and wine through Distinguished Vineyards & Wine Partners spanning New Zealand and the United States.

Kirin didn’t stop there. It also built a foothold in the Philippines through San Miguel, and pushed further into China. By 2010, overseas sales had climbed to 23.4% of the total—then the highest overseas revenue share among Japanese brewers.

From Tokyo, it looked like the playbook was working: mature home market, global expansion, diversified earnings.

In reality, this was where the story started to get harder. The further Kirin got from Japan, the more it ran into a gap that strategy decks tend to ignore: the distance between Japanese corporate culture and on-the-ground market reality. And that gap would test the limits of Kirin’s operating model in ways the company hadn’t fully priced in.

VI. Inflection Point #1: The Failed Suntory Merger (2009-2010)

In the summer of 2009, Japan’s beverage industry briefly entertained a what-if on the scale of a national champion: Kirin and Suntory, two of the country’s most storied names, were talking about becoming one.

On 14 July 2009, Kirin announced it was in merger negotiations with Suntory. For seven months, the talks held—right up until they didn’t. On 8 February 2010, the companies announced negotiations had been terminated.

If you’re wondering why this mattered, it’s because the combined company wouldn’t have just been big in Japan. It would have been big, period. Together, Kirin and Suntory had posted combined sales of beer, soft drinks, and foods of about $42.5 billion the prior year—larger than AB InBev or Coca-Cola at the time. For Japan, it would have been the first brewing and beverages group with a credible shot at standing toe-to-toe with the global giants.

Strategically, the fit looked clean. Kirin was stronger in beer; Suntory, though a distant third in Japanese beer with about a 12% share versus Kirin’s roughly 38%, was much stronger in soft drinks—nearly double Kirin’s roughly 10–11% domestic share. Put them together and you could imagine a broader portfolio, more scale, and lower costs in key battlegrounds like China.

But the deal didn’t die on spreadsheets. It died on governance.

Kirin negotiated on the premise that the combined entity would be run as a listed company—public-market rules, management independence, and transparency. Suntory didn’t see the world the same way. Kirin was a relatively Westernized, Tokyo Stock Exchange-listed operation. Suntory was still, at its core, a paternalistic family-owned business—and it wanted the new structure to reflect that reality.

The flashpoint was control. The two sides couldn’t agree on an acquisition ratio that would determine who ultimately ran the new company. Suntory’s founding family owned about 90% of the privately held business and was expected to become the largest shareholder, with roughly a one-third stake—large enough to block major decisions. Kirin, by contrast, wanted to limit that stake below the one-third threshold.

And underneath that was an even deeper clash: what a company is for.

A listed company pressed by dividend-hungry shareholders would struggle to embrace Suntory’s philosophy of splitting profits into thirds, directing portions not only to the business but also to customer service and cultural activities for the community. Public investors also tend not to romanticize long timelines the way Suntory did—like the 45 years it took for its beer business to become profitable, or the 20 years it spent researching blue roses.

So the merger that could have reshaped Japan’s beverage landscape fell apart—not because the market opportunity wasn’t real, but because the two companies couldn’t agree on who would hold the steering wheel, and what direction it should point.

And that failure would prove fateful. Instead of combining with a complementary partner at home, Kirin spent the next decade reaching for growth abroad through acquisitions that looked bold from Tokyo—and turned punishing in practice.

VII. Inflection Point #2: The Brazil Disaster (2011-2017)

If the Suntory deal was the path not taken, Brazil was the path Kirin chose—and paid for.

In 2011, Kirin set its sights on Schincariol, a family-run Brazilian brewer that ranked number two in the country. In October, a court decision cleared the way for Kirin to take control. Kirin first bought 50.45% for a deal valued at $2.6 billion, then moved quickly to buy out the remaining shareholders that November—its biggest acquisition yet, justified by a simple thesis: Brazil was growing, Japan wasn’t.

The company renamed the business Brasil Kirin and imagined it as a South American growth engine that would make Kirin less dependent on an aging, shrinking home market.

Instead, Brazil turned into a masterclass in how hard “emerging market growth” can be when you don’t have the operating muscle on the ground.

From early on, Brasil Kirin struggled in a brutally competitive market. The problems intensified in the second half of 2013, and Kirin later admitted it made things worse. In an interview, President and CEO Yoshinori Isozaki spelled it out: Kirin raised prices to protect profits, but pushed too far. A refresh of a core brand backfired and cost consumer support. The company stacked up marketing mistakes—and, crucially, didn’t have the governance system to react fast enough.

Then Brazil’s economy rolled over. Consumption stagnated, competition intensified, and the currency weakened. Kirin was forced to reassess the value of what it had bought. The result was a brutal impairment: an estimated loss of 3,881 million BRL, with a hit of about 114.0 billion yen expected to flow through as special losses.

At that point, the “strategic foothold” started to look more like an anchor. Kirin’s attention shifted elsewhere, and Brazil went from growth bet to exit plan. In 2017, Kirin agreed to sell the business to Heineken. The consideration to be paid to Kirin was EUR 664 million, implying an estimated enterprise value of EUR 1,025 million. Brasil Kirin’s own 2016 results told the story behind that price: BRL 3,706 million in revenue and an operating loss (before amortisation of goodwill and related items) of BRL 262 million.

Put simply, Kirin spent roughly $4 billion building its Brazil position and walked away with roughly $700 million. A huge amount of shareholder value evaporated.

And Brazil wasn’t just an unlucky macro story. It exposed a deeper problem: Kirin could buy scale overseas, but it struggled to run it. The company lacked local market intuition, integration was rocky, and Tokyo was too far away—geographically and psychologically—to manage a fast-moving, high-friction business in real time.

The Brazil disaster didn’t just hurt Kirin’s numbers. It damaged confidence in Kirin’s entire overseas M&A playbook—right as the company was about to face an even messier test of what it owed, and to whom, in Myanmar.

VIII. Inflection Point #3: The Myanmar Crisis—Ethics vs. Profit

If Brazil was a financial disaster, Myanmar became something worse: an ethical crisis that threatened to follow Kirin long after the numbers were forgotten.

Kirin’s expansion in Myanmar rested on a joint venture with Myanmar Economic Holdings Limited (MEHL), a military-owned conglomerate. The structure was straightforward and, commercially, extremely attractive: MEHL held 49% of Myanmar Brewery, maker of Myanmar Beer, while Kirin owned the remaining 51%. The partners also jointly owned Mandalay Brewery. Taken together, Kirin said these investments gave it control of roughly 80% of Myanmar’s beer market.

In late August 2017, the Myanmar government cleared Kirin to invest an additional USD$4.3 million for a 51% stake in Mandalay Brewery, again in a joint venture tied to the military-linked network. From a pure growth perspective, the logic resembled Brazil: find demand where it’s rising. But in Myanmar, the risk wasn’t currency or competition. It was what the profits might support.

Even before the 2021 coup, human rights organizations, including Human Rights Watch, criticized Kirin’s relationship with MEHL on the grounds that it risked channeling money to the military. That criticism intensified as reports of atrocities mounted—crimes against humanity and acts of genocide against the ethnic Rohingya in Rakhine State in 2017 increasingly coming to light.

Then came the donations controversy. Kirin said the payments were intended to help victims of the violence. Amnesty International, however, reported that the first donation was made by Myanmar Brewery staff to the Commander-in-Chief of Myanmar’s armed forces, Senior General Min Aung Hlaing, during a televised ceremony in Nay Pyi Taw on 1 September 2017. Kirin later confirmed that a $6,000 donation was made on that date.

In 2019, a UN fact-finding mission examining the military’s economic interests concluded that MEHL’s profits helped fund what it described as international war crimes and crimes against humanity, possibly including genocide. The mission identified MEHL as a key source of military revenue—and recommended that Min Aung Hlaing be tried for genocide for his leadership of what it called a campaign of mass murder, rape, and arson against the Rohingya in August 2017.

When Myanmar’s military seized control of the government in a coup in early 2021, the situation detonated. On 5 February, less than a week after the coup, Kirin announced it would terminate its partnership with MEHL, describing the military’s “recent actions” as violating the company’s “standards and Human Rights policy.” Pressure only intensified from there, culminating in a nationwide boycott of Myanmar Brewery products.

The unwind dragged on. On 30 June 2022, Kirin announced it would sell its 51% stake in Myanmar Brewery Limited to its military-linked local partner.

Myanmar became a case study in how ESG risk stops being abstract and starts showing up as real-world consequences. Whatever profits the venture generated, they were ultimately eclipsed by the reputational damage—and by the permanent question of what, exactly, those profits helped finance.

IX. The Health Science Pivot: KV2027 and Beyond

After Brazil and Myanmar, Kirin’s leadership didn’t just tweak the overseas playbook. It pushed harder into a different idea entirely: health science as a third pillar, alongside beverages and pharmaceuticals.

The spark for that pivot came from the lab, not the boardroom. In 2010, Kirin discovered a lactic acid bacterium called Lactococcus lactis strain Plasma, better known as LC-Plasma. What made it noteworthy wasn’t branding. It was biology: LC-Plasma directly activates plasma cytoid dendritic cells, or pDCs, which play a central role in orchestrating immune response.

That discovery turned into a consumer-facing platform under the iMUSE brand. iMUSE products were positioned around immune support and were accepted under Japan’s Foods with Functional Claims system—meaning the claims required scientific substantiation. For Kirin, iMUSE wasn’t just “another beverage company product.” It was proof that the company could take a proprietary biological material, build credible claims around it, and scale it in the real world.

And it started to scale. Kirin’s business related to LC-Plasma performed strongly, with annual sales in 2024 exceeding 23 billion yen, up about 10% from the prior year.

Then Kirin accelerated the strategy with acquisitions. In 2023, it bought Blackmores—an Australian supplements company that had been listed on the ASX since 1985—as a wholly owned subsidiary for $1.9 billion. The logic was straightforward: if Kirin wanted health science to become a meaningful growth engine, it needed distribution reach across Asia-Pacific, not just products in Japan.

The ambition was laid out in the numbers Kirin chose to lead with. Its long-term plan was to grow the Health Science Business Division from JPY103.6 billion in 2022 to JPY200 billion by 2027, using Blackmores as a key lever for APAC expansion.

FANCL became the other big piece. Kirin said FANCL would become a consolidated subsidiary on Sept. 19 after a tender offer lifted Kirin’s ownership to just over 75%. The friendly tender offer totaled 220 billion yen and became more complicated after Hong Kong-based MY.Alpha Management raised its stake in FANCL to around 10%, prompting Kirin to raise its offer and extend the purchase period.

Kirin’s messaging around these moves was explicit. “Together with Blackmores in Australia, we aim to become one of the largest health science companies in the Asia-Pacific region and achieve growth for the entire group,” said Takeshi Minakata, president and chief operating officer of Kirin Holdings.

The targets extended beyond 2027. Kirin said it aimed for health science revenue of 300 billion yen by 2030, with a normalized operating profit margin of at least 10% by that year—and, longer term, 15%.

Near term, management framed FY2025 as a year of profit improvement powered by consolidation and turnaround work. Kirin forecast health science normalized operating profit would rise by 14.6 billion yen, driven mainly by FANCL and Kyowa Hakko Bio, with a smaller contribution from Blackmores. The plan, Kirin said, was to lift results by consolidating FANCL for a full year, growing Blackmores, and reducing Kyowa Hakko Bio’s losses. At the group level, total normalized operating profit was forecast to tick up from 211 billion yen in FY2024 to 212 billion yen in FY2025.

X. The Business Today: Portfolio Overview

In March 2024, Kirin shifted to a new management structure. I was appointed Representative Director of the Board and CEO, and Takeshi Minakata was appointed Representative Director of the Board, President, and COO.

Minakata is a Kirin lifer. He joined Kirin Brewery in 1984 and started on the ground at Toride Brewery, then moved across multiple breweries and into overseas roles at Kirin Europe and Lion. Over time, he ran both the Japanese Alcoholic Beverages and Non-alcoholic Beverages businesses.

He also ended up at the center of two of Kirin’s most consequential chapters. From 2016, he served as president of Myanmar Brewery Limited, during a period when Myanmar’s democratization was advancing. Then, from 2018, he took over as president of Kyowa Hakko Bio and confronted quality issues and organizational revitalization head-on. By 2022, as president of the Health Science Business Division, he was pushing the expansion of the LC-Plasma business—the scientific foundation behind iMUSE.

That same year, he began making repeated trips to Blackmores in Australia, building trust directly through negotiations. Those efforts culminated in Kirin’s acquisition of Blackmores in 2023. Going forward, Kirin Holdings plans to pursue a growth strategy aimed at building the strongest presence in the Asia-Pacific region.

The current Kirin portfolio spans four main domains:

Beer and Spirits (Domestic Japan): The Domestic Beer and Spirits segment manufactures and sells beer, low-malt beer, new genre products, wine, and other liquor products in Japan. The Domestic Beverages segment manufactures and sells soft drinks in Japan. The Oceania Alcoholic Beverages segment manufactures and sells beer and Western-style liquors in Oceania and other regions. The Pharmaceuticals segment manufactures and sells pharmaceutical products.

Overseas business, including alcoholic and nonalcoholic beverages, represents about 40% of the group’s sales.

Today, overseas operations account for more than half of the Group’s normalized operating profit and EPS, and Kirin expects that globalization to accelerate.

In 2024, Kirin’s consolidated normalized operating profit exceeded its goal and reached a record high for the Group.

XI. Playbook: Business and Strategic Lessons

Lesson 1: Fermentation as Platform—When Does "Related Diversification" Actually Create Value?

Kirin’s favorite strategic story is that fermentation is the thread that ties everything together: beer, pharmaceuticals, and now health science. And to be fair, pharma gives that argument real credibility. The success of biotechnology-derived drugs like Crysvita shows that “we’re good at working with living systems at scale” can translate into a business far beyond beverages.

But once Kirin pushes into health science through supplements and cosmetics—especially via FANCL—the linkage gets harder to defend. FANCL’s edge is consumer brand building and D2C retail execution, not biotech. You can still make the case that Kirin is assembling a broader “health” portfolio, but it’s a different kind of adjacency than beer-to-biopharma. The question isn’t whether it sounds connected. It’s whether the capabilities actually transfer.

Lesson 2: The Limits of Emerging Market Expansion for Mature Market Companies

Brazil surfaced a painful truth: what makes you great in a mature, stable market doesn’t automatically make you great in a volatile one. Distance matters—geographically, culturally, and operationally. When the business needed fast decisions, Tokyo was too far away, and the organization wasn’t set up to course-correct quickly.

Isozaki’s own reflections on governance and slow response are telling. The failure wasn’t only macro or currency. It also looked like a systems problem: how a large Japanese multinational manages, integrates, and actively runs a complex business on the other side of the world.

Lesson 3: Corporate Governance and Family Control—The Suntory Merger Failure as Cautionary Tale

The Kirin-Suntory talks didn’t collapse because the math didn’t work. They collapsed because the two sides couldn’t agree on what kind of company they were building. Kirin wanted public-company independence and transparency. Suntory expected a structure that preserved the founding family’s blocking power and long-term philosophy.

It’s tempting to treat this as a missed chance at a global champion. But it’s also a reminder that “strategic fit” means nothing if governance doesn’t fit. Whether Kirin was being principled or simply inflexible depends on the counterfactual: how would the combined company actually have performed, and at what cost to decision-making?

Lesson 4: ESG Risks Are Real Financial Risks—Myanmar as Case Study

Myanmar showed how quickly an ethical issue can become a business crisis. Human rights warnings didn’t start after the coup; they were there for years. But the full weight of reputational risk didn’t hit until the political situation snapped, public pressure surged, and a nationwide boycott followed.

The lesson isn’t that companies should never enter difficult markets. It’s that when your partner is military-linked, “operational risk” and “moral risk” stop being separate categories. Kirin’s struggle to unwind quickly suggests it underestimated how fast ESG concerns can turn into an existential threat.

Lesson 5: The Activist Critique—When Does Diversification Become Conglomerate Discount?

Not everyone buys Kirin’s transformation story. London-headquartered Independent Franchise Partners has argued that Kirin should stick to beer and give up what it called the “unrealistic hope” of becoming a diversified conglomerate. That critique landed amid a tough moment: Kirin reported a significant year-over-year drop in earnings for full year 2019.

The activists’ core question is simple: why have brewers like Asahi, Heineken, Carlsberg, and Anheuser-Busch InBev—companies that largely stayed disciplined around their core beer strategies—consistently outperformed Kirin in total shareholder return?

Shareholders, for now, have sided with management. Kirin Holdings shareholders overwhelmingly rejected an activist proposal that the company exit non-beer businesses and use the proceeds for buybacks, including repurchasing treasury shares worth 600 billion yen. With that vote, Kirin won the right to keep pushing ahead—expanding further into biotechnology, pharmaceuticals, and cosmetics in search of growth as global beer consumption slows.

Lesson 6: Japanese Corporate Culture—Patience, Consensus, and the Challenge of Decisive Pivots

Kirin’s story only makes sense if you appreciate what Japanese corporate culture can do well. The pharmaceutical business took about a decade before it even began to pay off. In an American-style quarterly environment, it’s hard to imagine that kind of long incubation surviving. Yet that patience helped Kirin build a profit-generating pillar that now supports the wider group.

But the same patience can cut the other way. If you’re willing to endure years of investment and underperformance, you may also tolerate failing ventures for too long. In that light, Brazil looks less like a one-off mistake and more like the shadow side of the same cultural strength that made pharma possible: consensus, endurance, and a high bar for admitting something isn’t working.

XII. Porter's Five Forces & Hamilton's Seven Powers Analysis

Porter's Five Forces—Japanese Beer Market:

Threat of New Entrants: LOW

Japan’s beer market is effectively locked up by the “big four”: Kirin, Asahi, Sapporo, and Suntory. Together they control nearly all of the category. To break in, a newcomer would need massive brewing capacity, nationwide distribution, regulatory know-how, and—hardest of all—brand trust built over decades. That combination makes meaningful new entry close to impossible.

Supplier Power: MODERATE

Brewing depends on a small set of critical inputs: malted barley, hops, and packaging materials like aluminum. Because those inputs trade in global commodity markets and brewers can source from multiple suppliers, no single vendor has overwhelming leverage. But there’s a slow-moving squeeze here: climate change is increasingly threatening hop-growing regions, and that can tighten supply and raise costs.

Buyer Power: MODERATE TO HIGH

As Japanese retail has consolidated, large buyers have gained more negotiating power. At the same time, consumers have become more price-sensitive, especially in happoshu and “new genre” products where switching is easy and promotions matter. Brewers try to fight that pressure through premiumization in traditional beer, but the baseline dynamic is still a tug-of-war over shelf space and price.

Threat of Substitutes: HIGH

Beer isn’t just competing with other beer. It’s competing with a shrinking drinking population and a cultural shift among younger adults, for whom alcohol is less likely to be a default habit. And when they do drink, the menu is broader than ever: chuhai, wine, spirits, ready-to-drink cocktails, and non-alcoholic options all pull occasions away from beer.

Competitive Rivalry: HIGH

This is a four-player knife fight in a market that isn’t growing. Asahi has the largest share at roughly the high 30s, followed by Kirin in the mid 30s, with Suntory and Sapporo rounding out the field. With well-capitalized incumbents battling for a limited number of drinkers, rivalry shows up as constant product launches, heavy marketing, and aggressive competition for distribution.

Hamilton's Seven Powers:

Scale Economies: Brewing and distribution reward scale, but domestically Kirin and Asahi sit at similar size. That means scale helps both, but neither gets a decisive structural cost edge over the other in Japan.

Network Effects: Traditional beverages don’t have network effects. The closest analogue may emerge in health science through direct-to-consumer channels like FANCL, where data, repeat purchasing, and customer relationships can compound over time—but that’s still a different game than beer.

Counter-Positioning: Kirin’s health science pivot is, in part, a counter-positioning bet: that other brewers won’t—or can’t—follow it into pharmaceuticals and supplements. The catch is that counter-positioning only works if Kirin’s “fermentation as a platform” advantage creates real defensibility, not just a narrative.

Switching Costs: For consumers, switching between beer brands is essentially frictionless. Switching costs are more meaningful in pharmaceuticals and parts of healthcare distribution, where relationships, formularies, and operational complexity create stickiness.

Branding: iMUSE has a meaningful branding edge inside Japan’s health science market: it was the first food accepted under the Foods with Functional Claims system for an immune support function claim tied to maintaining immune function in healthy people. That substantiated claim helps differentiate in a category crowded with vague promises.

Cornered Resource: Kyowa Kirin’s antibody technology platform and Kirin’s proprietary LC-Plasma strain are the closest thing to “cornered resources” in the group—scientific assets that are difficult for competitors to replicate quickly, if at all.

Process Power: Kirin’s operational DNA is process excellence—first in brewing, then in biopharmaceutical manufacturing. That accumulated know-how can be a real advantage where quality, consistency, and scale matter. The open question is how much of that translates into the supplements and consumer wellness arena, where brand, distribution, and speed often matter as much as manufacturing.

XIII. Key Performance Indicators to Watch

If you want a clean read on whether Kirin’s “beer to health science” transformation is actually working, there are three metrics that tell the story better than any slide deck.

1. Health Science Business Normalized Operating Profit Margin

Kirin has been clear about where it wants this to go: a 10%+ margin by 2030. Today, it isn’t there yet. Watching this line over time is the simplest way to judge whether the big bets on Blackmores and FANCL are producing real operating leverage—or whether health science stays strategically important, but financially thin, despite absorbing a lot of capital and management attention.

2. Kyowa Kirin Pipeline Progress

Kyowa Kirin is arguably Kirin’s strongest “proof point” that fermentation and biotech capabilities can translate into a serious business. But pharma only stays valuable if the pipeline keeps moving. Watch how new drug candidates advance, what gets approved, and how dependent results remain on Crysvita and Poteligeo. The more diversified the pipeline becomes, the less the whole group is riding on a small number of blockbuster products.

3. Japan Beer Segment Revenue Per Hectoliter

In Japan, volumes are structurally pressured. That means the domestic beer business can’t win by selling more. It can only win by earning more per unit—through premiumization, mix improvement, and brand strength. Revenue per hectoliter is the gut-check: is Kirin successfully trading volume for value, or is it just shrinking more slowly than everyone else?

XIV. Bull Case and Bear Case

The Bull Case:

Kirin’s long game in biotechnology has already produced something rare: a Japanese conglomerate with a real scientific spine, not just a collection of brands. Kyowa Kirin gives the group a specialty pharma growth engine that doesn’t depend on whether Japan’s beer market shrinks another couple of points. And the health science push has a credible anchor in LC-Plasma—not a marketing concept, but a proprietary strain that Kirin can build products and claims around.

Layer on the distribution and consumer reach from Blackmores and FANCL, and you can see the intended end state: Kirin as a leading health and wellness player across Asia-Pacific, riding secular tailwinds like aging populations and rising health consciousness. In that world, Kirin’s edge isn’t that it sells supplements; it’s that it can back them with integrated fermentation and immunology research in a way many pure-play wellness companies can’t.

The final piece of the bull case is governance and learning. Brazil and Myanmar were expensive lessons, but they were lessons. If capital allocation discipline truly improves, the market may eventually stop valuing Kirin like “a beer company with side projects” and start giving full credit to the pharmaceutical and health science pillars that already make up a meaningful part of the story.

The Bear Case:

Activists like Independent Franchise Partners didn’t lose their argument just because they lost a vote. Their critique lands because Kirin’s diversification record is mixed, and the pressure to prove returns doesn’t go away.

The deeper bear case is that Kirin’s diversification thesis still isn’t fully validated. “Fermentation as a platform” can be a genuine advantage in biopharma, but it can also become a convenient umbrella for a conglomerate that’s drifting. Health science, in particular, may turn out to be a tougher business than the strategy implies: supplements and cosmetics are driven by branding, retail execution, and product cycles that look nothing like pharmaceuticals. Paying a premium for FANCL can be read less as building on biotech capabilities and more as buying consumer-facing distribution and D2C know-how—useful, but not the same kind of moat.

Meanwhile, the core beer business faces a structural decline that no amount of clever product innovation can fully reverse. If management attention and investment are spread across beverages, pharma, and health science, Kirin risks ending up not truly dominant in any one arena. From this perspective, the “conglomerate discount” isn’t a misunderstanding by the market—it’s the market pricing in limited synergies, slower decision-making, and a strategy that may be harder to execute than it looks on paper.

XV. Material Risks and Regulatory Considerations

Pharmaceutical Pipeline Risk: Kyowa Kirin’s pharma business leans heavily toward rare disease drugs, which can be a blessing and a trap. When a new therapy works, it can become a durable franchise. When a trial disappoints or a launch underperforms, the impact can be sudden and outsized.

Currency Risk: Kirin now earns a meaningful share of its money outside Japan, and that comes with an unglamorous reality: exchange rates. Earnings in currencies like AUD, USD, and PHP can swing when translated back into yen, creating volatility in JPY-reported results that has nothing to do with how well the underlying businesses are actually operating.

Regulatory Risk: In Japan, alcohol rules don’t just shape pricing; they shape entire product categories. The malt-based taxation regime is the reason happoshu and the “new genre” exist at scale at all. If tax rules are further harmonized, it could scramble the economics that have historically helped Kirin compete—and potentially erode advantages it built in those categories.

ESG/Reputational Risk: Myanmar may be unwound, but it doesn’t vanish from the record. Kirin’s decisions around partners, governance, and human rights due diligence are likely to remain an area of scrutiny for activists, stakeholders, and regulators—especially as the company continues to look for growth beyond Japan.

Accounting Considerations: The health science push has been acquisition-led, and acquisitions come with balance-sheet baggage. Goodwill and other intangibles from deals like Blackmores and FANCL need to earn their keep. If integration goes poorly or synergy goals don’t show up in results, Kirin could face impairment risk that hits reported earnings and reopens questions about capital allocation discipline.

XVI. Conclusion: The Mythical Beast at a Crossroads

Kirin now sits at one of the most consequential junctions in its 140-year run. The company that started as a foreign-backed brewery in Meiji-era Yokohama has already lived several lives: domestic beer powerhouse, overseas dealmaker, serious pharmaceutical builder, and now an aspiring health science platform.

On paper, the logic hangs together. Japan’s beer market is structurally challenged by demographics and changing habits. Kirin’s long investment in fermentation and biotechnology created real scientific capabilities, and Kyowa Kirin is the clearest proof that patience can turn “adjacent” into “real.” Meanwhile, across Asia-Pacific, “health” has become a consumer category with genuine demand—one Kirin is trying to meet with functional products and bigger distribution bets.

But the skepticism hasn’t come out of nowhere. Kirin’s recent history includes painful reminders that strategy is easy to announce and hard to execute. Brazil was a value-destroying misread of an “emerging market growth” story. Myanmar showed how quickly a profitable venture can become reputationally toxic—and how hard it is to unwind once you’re in. And the health science push, ambitious as it is, still has to prove it can consistently generate the kind of margins and returns that justify the capital it’s consuming.

That’s why the next few years matter so much. If health science can hit its profitability goals, if Kyowa Kirin keeps advancing beyond its current key products, and if the domestic beer business can manage decline without bleeding cash, Kirin’s reinvention will look less like diversification for its own sake and more like a rare, disciplined transformation.

If not—if the promised synergies don’t show up, if acquisitions don’t translate into durable profits, and if management keeps spreading attention across too many fronts—then the “conglomerate discount” won’t be a narrative problem. It will be the market’s way of saying the mythical beast has wandered too far from its strengths.

In legend, the kirin appears in times of peace and wise rule. Whether Kirin the company can earn that symbolism in its next chapter is still an open question.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music