Asahi Group Holdings: From Near-Bankruptcy to Global Beer Empire

I. Introduction: The Phoenix of Japanese Beer

Picture Tokyo in 1987: neon bleeding into rain-slick streets, salarymen funneling into smoky izakayas after long workdays. Beer is the background music of the night. And in that familiar setting, something unfamiliar is about to happen. A brewer that most people had already counted out is preparing to drop a product so different it won’t just save the company. It will reset what Japanese beer is supposed to taste like.

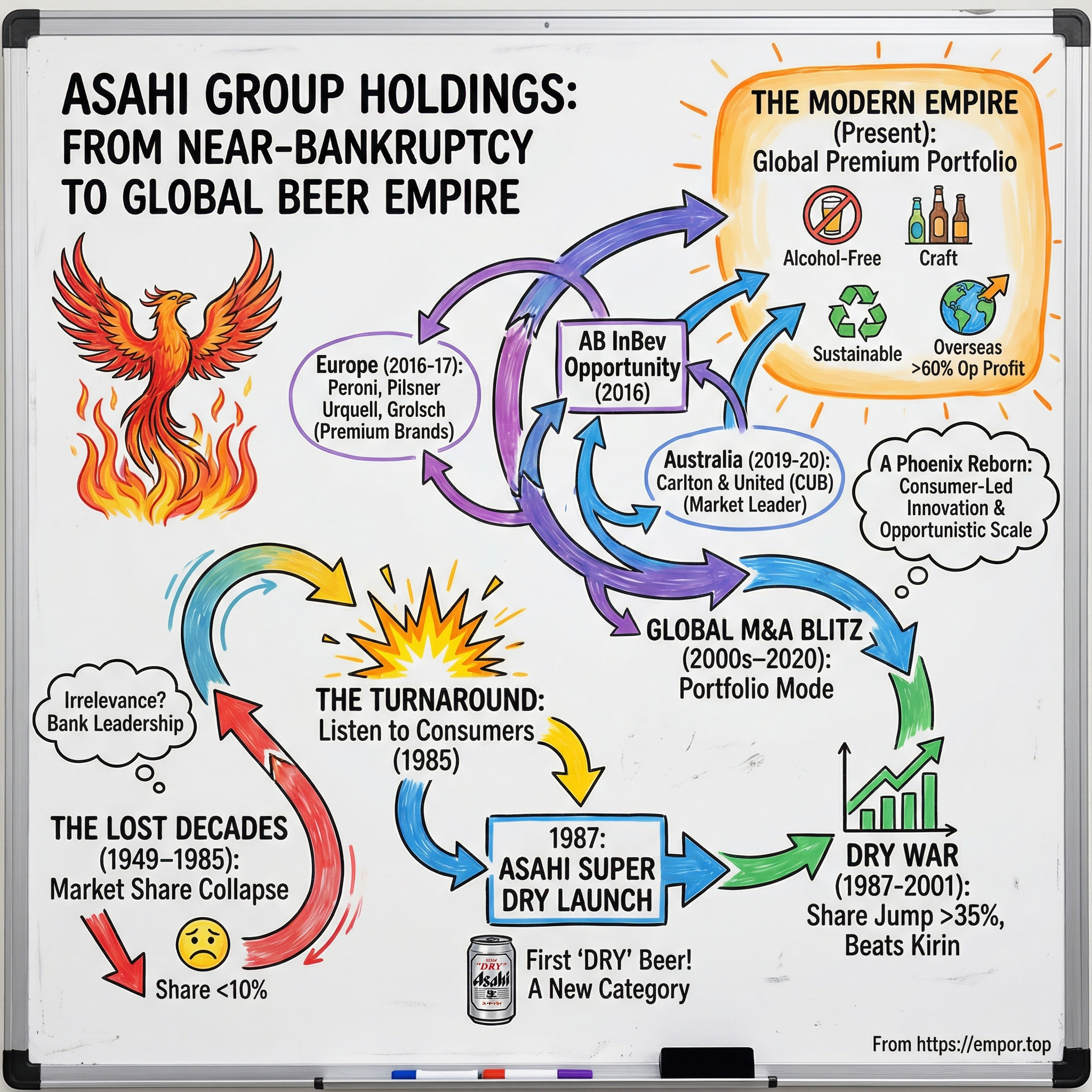

Fast forward to today, and Asahi sits on top of Japanese beer. It holds about 37% of the market, ahead of Kirin at 34% and Suntory at 16%. It’s also no longer just a domestic champion: overseas markets now contribute more than half of revenue and close to 60% of operating profit.

That’s what makes the Asahi story so compelling. The Asahi we know now—a global operator with premium brands across continents—barely resembles the Asahi of the early 1980s. Over the decades after World War II, its Japanese market share slid from a high of 36% in 1949 to just 10% by 1981. The company was in such rough shape it couldn’t reliably produce its own leadership; CEOs were being dispatched from Sumitomo Bank to stabilize the situation and, frankly, to keep the patient alive.

So the question is simple, and it’s the whole episode: how does a company on the brink of extinction turn itself into one of the most successful beer businesses in the world?

The answer comes in three acts. First, a near-death experience that forces Asahi to confront what consumers actually want. Second, a product revolution that creates a new category and triggers an industry-wide arms race. Third, a global acquisition blitz—perfectly timed—when regulatory pressure forces the world’s biggest brewer to sell great assets, and Asahi is ready to buy.

By 2024, Asahi is a JPY 2.9 trillion group spanning alcoholic beverages, overseas operations, soft drinks, food, and other businesses. But the modern empire starts with a much simpler move—one that’s surprisingly rare in big companies: when things got dire, Asahi stopped guessing, and started listening.

II. Origins: The Birth of Japanese Beer (1889–1949)

Asahi’s story starts in Meiji-era Japan, when the country was racing to modernize and eagerly importing Western technology, tastes, and rituals. Beer had arrived earlier—first through Dutch traders during the Edo period—but for decades it stayed more novelty than staple. It wasn’t until Japan reopened to foreign trade in the mid-1800s that beer began to look like a real domestic business.

In 1889, the company that would eventually become Asahi was established. That same year, Komakichi Torii set out to build a beer business in Osaka with an unusually ambitious premise for the time: Japan shouldn’t just drink imported beer, it should brew beer that could stand proudly on the world stage.

The early execution matched the ambition. The company opened the Suitamura Brewery in 1891—described as Japan’s first modern brewery—signaling that this wasn’t a cottage operation. And it kept pushing the product format forward, too: by 1900, the business had introduced Asahi Draft Beer, Japan’s first bottled draught beer.

Then came the kind of credibility money can’t buy. Within a few years, Asahi beer won awards at the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago, and later at the 1900 World Fair in Paris. For a young Japanese brewer, competing in a category dominated by European tradition, it was an extraordinary stamp of legitimacy.

But the bigger forces shaping Asahi weren’t happening in the brewhouse—they were happening across the whole industry. Japan’s brewing landscape in the early 1900s was fragmented, and the government’s beer taxes made life increasingly difficult for smaller players. Consolidation was inevitable.

In 1893, the company was reorganized as Ōsaka Breweries. Then, in 1906, Ōsaka Breweries merged with Nippon Breweries and Sapporo Breweries to form Dai-Nippon Breweries—literally “Great Japan Beer Company.” The new giant quickly became the dominant player. By the time the deal dust settled, Dai-Nippon controlled roughly 70% of the Japanese beer market.

Even in those early days, Asahi’s future “group” shape was already emerging. Under the Dai-Nippon umbrella, the business wasn’t only about beer. It began building a long-running relationship with non-alcoholic beverages, including brands like Mitsuya Cider and Wilkinson Tansan. Mitsuya Cider entered the market in 1907—an early diversification move that, more than a century later, still looks like a strategically lucky instinct.

As Japan moved toward World War II, regional preferences hardened. The Asahi brand grew especially popular in Kansai. And the industry itself kept consolidating. By 1943, the merger wave had effectively finished: only Dai-Nippon and Kirin remained as major brewing companies in Japan.

Then the war ended—and with it, the old industrial order. During the Allied occupation, American administrators sought to dismantle concentrated economic power they believed had fueled militarism. Dai-Nippon’s near-monopoly made it an obvious target.

After World War II, Dai-Nippon was divided under the Elimination of Excessive Concentration of Economic Power Law, implemented by the Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers. In 1949, the company that had once held nearly 70% of Japan’s beer market was split into two: Nippon Breweries, Ltd. (which is now Sapporo Breweries) and Asahi Breweries, Ltd.

That split did more than create Asahi as an independent entity—it set the rules of the game for decades. Post-war Japan settled into a remarkably durable beer oligopoly dominated by four companies: Asahi, Kirin, Sapporo, and Suntory. Even by 2024, those four players still controlled about 95% of the domestic market, largely built around pale lagers at roughly 5% ABV.

And for Asahi, this is where the real drama begins. Independence didn’t guarantee leadership. It guaranteed competition—against rivals that would soon turn the Japanese beer market into a winner-take-most battle, with one competitor in particular looking, for a long time, untouchable.

III. The Lost Decades: Market Share Collapse (1949–1985)

Asahi’s split from Dai-Nippon in 1949 should have been a fresh start. Instead, it became the start of a long slide. Not a single bad year, not one obvious scandal—just a steady erosion of relevance that, by the mid-1980s, left the company staring at the edge.

Zoom out, and the structure of the industry made the pain even worse. Japan’s beer market was an oligopoly dominated by four players: Kirin, Asahi, Sapporo, and Suntory. But “oligopoly” doesn’t mean “balanced.” After World War II, Kirin became the default beer of Japan, commanding a majority share through the mid-1970s into 1985. Sapporo trailed behind, and Asahi sank into the low double digits, with Suntory smaller still.

Translated into real life: by 1985, most of the beer being poured in Japan had a Kirin label on it. Asahi—once a true contender—was scraping by at under a tenth of the market.

For decades, Asahi’s main weapon was Asahi Gold, its flagship beer from 1957 through the late 1980s. But it couldn’t dent Kirin’s dominance. And the real problem wasn’t just share—it was momentum. Kirin felt inevitable; Asahi felt like yesterday’s brand.

That inevitability was reinforced by the rules of the game. Beer is brutal to break into: massive ad budgets, locked-up distribution, and heavy regulation. In the postwar era, only two firms even attempted to enter the category. So if you were one of the four incumbents, you didn’t compete on price—you fought on quality, marketing, and distribution muscle. And Kirin had more of all three. Over time, its name didn’t just win in the market; it became synonymous with “beer” itself.

The smaller players tried to innovate their way out. But a pattern emerged: any meaningful innovation from a challenger was quickly copied. And if a trend looked like it might actually threaten Kirin, Kirin could lean on its scale—marketing, incentives, distribution relationships—to blunt the surge and restore the old equilibrium.

Asahi, meanwhile, fell into a genuine downward spiral. Sales declined, inventories piled up and went stale, and the company ultimately laid off 550 employees out of a workforce of 3,200. This wasn’t a soft decline. It was the kind you feel in the factory, in the sales organization, and in the morale of the whole company.

Eventually the crisis got so severe Asahi couldn’t even reliably produce its own leadership. Starting in the early 1970s, Sumitomo Bank sent executives into the president’s office in an attempt to stabilize the business. The decline continued anyway. Then, in January 1982, Sumitomo sent another banker: Tsutomu Murai.

Murai wasn’t just a caretaker. He had a reputation as a turnaround specialist and had previously helped rescue Mazda Motor Corporation. And he didn’t arrive alone—Sumitomo’s influence ran deep. The Sumitomo Group was also one of Asahi’s key shareholders at the time, with roughly a 12% stake.

By the time Murai took over, Asahi’s position had become painfully clear. Once Japan’s No. 2 brewer, it had dwindled to just over 10% share. Murai’s first big directive to R&D was simple, and at the time, surprisingly radical: stop guessing. Listen.

Inside the company, he tried to rebuild the basics—mission, strategy, and pride—setting up teams like the Corporate Identity Introduction Team and the Total Quality Control Introduction Team, aimed at improving customer satisfaction and the company’s image with both employees and consumers.

He also pursued outside help. In late 1982, Asahi signed an agreement with Löwenbräu of West Germany to brew Löwenbräu under license in Japan, with production starting the following April. It signed technology contracts with U.S., British, and German brewers to build technical know-how. And in 1984, Asahi’s soft drink division struck a deal with Schweppes, leading to Asahi manufacturing several Schweppes brands in Japan.

But Murai could see what those moves really were: necessary, but not sufficient. Licensing and incremental upgrades wouldn’t reverse a brand that consumers had stopped choosing. If Asahi was going to survive, it needed to rebuild its relationship with the market from the ground up.

So in 1985, Murai ordered what would become the most consequential market research project in Japanese brewing history.

IV. The Turnaround Begins: Consumer Research Revolution (1985–1987)

Put yourself in Asahi’s shoes in 1985. The company is shrinking, morale is shot, and Kirin feels as inevitable as gravity. Distribution is stacked against you, advertising is a money pit you can’t win, and consumers have basically decided your beer is second-rate by default.

So what do you do when every traditional lever is maxed out?

Murai’s move was radical mostly because it was so simple: ask people. Not focus groups to confirm internal opinions—real, broad consumer research designed to tell the company something it didn’t want to hear.

And it did. In one of the key surveys Murai ordered, 98% of beer drinkers told Asahi the same thing: change the taste.

Ninety-eight percent isn’t “we should tweak the formula.” It’s a flashing red sign that says the product is broken.

Consumers described what they wanted in a way that sounded almost contradictory: a beer that felt rich, but left no aftertaste. Asahi’s technicians insisted that combination wasn’t chemically possible. Murai wasn’t interested in “not possible.” He insisted that nothing was impossible.

What the research surfaced wasn’t just a flavor preference—it was a societal shift. In the late 1970s and early 1980s, the typical Japanese beer tasted noticeably sweeter than what would become the modern norm. But Japan was changing fast. As incomes rose and Western food culture spread, younger drinkers were eating more meat and heavier, greasier dishes than the previous generation. A sweet, malty beer didn’t cut through that kind of meal. It piled on.

Consumers were telling Asahi they wanted something lighter, crisper—something that would reset your palate instead of weighing it down.

Asahi’s response was “Project FX”: a secretive development sprint aimed at building the perfect dry beer. The mandate was brutal: deliver the dryness the market wanted without sacrificing quality. That meant real technical work, not marketing spin—especially in fermentation, where Asahi pushed toward high attenuation so more sugars would be fermented out, leaving less residual sweetness and a cleaner finish.

The problem, in plain language, was this: how do you make a beer that tastes satisfying on the first sip, but doesn’t hang around and get cloying?

The answer was fermentation science. Under Project FX, Asahi built a highly attenuated, highly carbonated pilsner. On March 17, 1987, it launched under a new name: Asahi Super Dry. And in doing so, Asahi didn’t just introduce a new product—it created an entirely new category: dry beer.

One of the keys to Super Dry’s distinctiveness was yeast. Asahi used a proprietary strain, Asahi #318, that helped drive high attenuation—turning more sugar into alcohol and carbon dioxide and leaving fewer residual sugars behind. The result was the signature profile: crisp, clean, and easy to keep drinking without “flavor fatigue.”

The brewers also took inspiration from somewhere very Japanese: the dry taste of sake. In Tokyo, on March 17, 1987, they landed on the taste that would reset the beer market—and named it Asahi Super Dry.

Super Dry arrived with a new concept for mainstream Japanese beer: karakuchi, or “dry.” The term doesn’t map cleanly into English. In Japanese food and drink, it can imply something sharp or “snappy,” and in sake it often signals dryness. For beer, it became a promise: clean finish, no lingering sweetness, and a crispness that matched the direction Japanese tastes were heading.

Asahi even went deeper into yeast biology, finding that certain types of genes were present in large numbers—genes related to sugar assimilation, proliferation, and the production of alcohol and carbon dioxide. By designing fermentation conditions to activate those characteristics, Asahi kept refining what it was really selling: crispness.

And Murai knew taste alone wasn’t enough. After years of decline, Asahi needed to signal transformation in a way you could see from across the room. When a product changes fundamentally, design’s job isn’t to whisper—it’s to declare. Not a nostalgic nod to the past, but a visual promise that this time, the company really means it.

The stage was set. After years of decline and months of quiet, obsessive development, Asahi was about to place the biggest bet in Japanese brewing history.

V. Super Dry Launch: The Bet That Saved the Company (1987–2001)

March 17, 1987. It deserves to sit on the short list of modern product launches that didn’t just win a market—they rewrote it. Because on this day, Asahi didn’t release “a new beer.” It introduced an idea. And that idea pulled the company back from the edge.

Asahi Super Dry was a highly attenuated lager—built to finish clean, without the heavier maltiness that defined many competitors. The taste was crisp and dry, closer in spirit to some northern German lagers than to the sweeter profile Japanese drinkers had come to expect.

It was also engineered to feel lighter: slightly higher in alcohol than the typical domestic beer at the time, but with less sugar and less bitterness. That combination landed perfectly with younger drinkers, and the response was immediate. Within a year, Asahi’s market share jumped into the high teens.

The speed of the uptake surprised even Asahi. Murai had been planning a broader diversification push—at one point, aiming for roughly half of revenue to come from non-beer businesses. Super Dry blew a hole through that plan. Beer suddenly mattered again. By 1988, it made up about 80% of sales.

And this wasn’t just a “hit product.” It was a full business reversal. Demand for “dry” beer surged, and Asahi’s performance surged with it—enough that the company began surpassing Kirin in both sales and profitability. In the first wave, Super Dry helped drive a dramatic jump in sales in 1987, and by 1989 Asahi’s share had climbed into the mid-20s, pushing it past Sapporo into second place.

That’s when the rest of the industry did what incumbents always do when a challenger finds a new playbook: they copied it, fast.

Kirin—still the heavyweight, sitting around half the market—launched Kirin Dry in early 1988 with a major advertising blitz, then followed with an all-malt Kirin Malt Dry. It didn’t stop the momentum. In 1990, Kirin introduced Ichiban Shibori to compete head-on, but the move came with a painful tradeoff: it ate into profits from Kirin’s own flagship Lager brand. Kirin never reclaimed its old dominance.

Sapporo chased the trend too. Sapporo Dry launched in early 1988 and fizzled. Then Sapporo tried to reposition its flagship—rebranding Sapporo Black Label as Sapporo Draft in 1989—only to meet an unfavorable reception. Both of those products were pulled within two years.

This era got a name: the “Dry War.” It was an all-out scramble—Kirin, Sapporo, and Suntory trying to dethrone the new king of a category that didn’t even exist before Asahi named it.

But Asahi’s edge wasn’t only in the liquid. It changed how beer was sold. In Japan, beer had traditionally moved through small liquor stores, often by the bottle. Asahi pushed hard into cans and six-packs, then pushed those packs into supermarkets and convenience stores—reaching customers in places the old playbook hadn’t prioritized.

At the same time, it got tougher, and smarter, with retailers. Asahi leaned on one message over and over: freshness. And it backed the claim operationally—by the mid-1990s, it could deliver beer to stores about ten days after brewing.

The result was one of the most dramatic share shifts in modern Japanese consumer business. By 1997, Super Dry had knocked Kirin’s Lager off the top spot among individual beer brands. Asahi’s overall share had climbed into the mid-30s—up from about 10% in 1985—while Kirin fell sharply from its prior heights.

Within a decade, Asahi Super Dry became the best-selling beer in Japan.

And it didn’t stay a local phenomenon. Super Dry went on to sell more than 100 million cases annually, and by 2000 it ranked among the biggest beer brands in the world by volume.

Asahi formally marked the turnaround in January 1989, renaming the company Asahi Breweries, Ltd.—but the real rebrand had already happened in the minds of consumers. Super Dry is a masterclass in category creation: Asahi didn’t try to win on Kirin’s terms. It created a new battlefield, grabbed first-mover advantage, and forced every competitor to fight in its shadow.

VI. Diversification and Early International Moves (1990s–2010s)

Super Dry saved Asahi. But it didn’t solve the long-term problem staring every Japanese consumer company in the face: Japan wasn’t going to grow forever. Even with a blockbuster product, the domestic beer market was destined to mature—and then slowly shrink—under the weight of demographics.

So Asahi did what great turnarounds often have to do next. It shifted from survival mode to portfolio mode: expand into adjacent categories, build capabilities outside Japan, and place smart bets overseas.

Some of that diversification had been underway for years. As far back as the 1970s, Asahi had moved aggressively into soft drinks, including beverage vending machines and the acquisition of Mitsuya Cider. In one sense, this wasn’t a new direction—Asahi had been involved in soft drinks since 1907. But in the postwar era, the company started treating it as a real growth engine. By the mid-1970s, soft drinks were about 35% of total sales.

And Asahi wasn’t just pushing product; it was building technical depth. Its Central Research Laboratory, created primarily for quality control, also produced new hit products—like “Ebios,” a brewer’s yeast widely known in Japan for its medicinal properties.

On the alcohol side, Asahi made a foundational move in whisky. In 1989, it turned Nikka Whisky Distillery Co., Ltd into a wholly owned subsidiary, building on a capital participation relationship that had started in 1954. It gave Asahi a premium foothold in Japanese whisky—years before the category’s global boom would make it even more valuable.

International expansion began to take real shape in the 1990s. In 1990, Asahi bought a 19.9% stake in Australian brewer Elders IXL, which later became the Foster’s Group and was eventually sold to SABMiller. It was early and minority—more a learning position than a takeover—but it gave Asahi a view into how major brewing businesses worked outside Japan.

Asahi also started probing China. In 1994, it entered with controlling interests in several breweries. And in 1995, it kicked off a broad alliance with U.S.-based Miller Brewing Company—another way to import know-how and relationships rather than trying to reinvent everything alone.

Then came a high-profile China move. In early 2009, Asahi acquired 19.9% of Tsingtao Brewery from Anheuser-Busch InBev for $667 million, becoming the second-largest shareholder in China’s best-known beer brand.

But the most consequential operating platform outside Japan started forming in Australia and New Zealand. In 2009, Asahi acquired Schweppes Australia’s beverages unit, now known as Asahi Beverages. In July 2011, it acquired New Zealand juice maker Charlie’s, along with the water and juice divisions of Australia’s P&N Beverages. And in August 2011, it bought New Zealand’s Independent Liquor—maker of Vodka Cruiser and other alcoholic beverages—for ¥97.6 billion.

Back home, Asahi kept strengthening its non-beer portfolio. A major milestone came in 2012 with Calpis, one of Japan’s most beloved beverage brands. Asahi acquired Calpis as part of its soft drinks division. CALPIS® traces back to 1919, when Kaiun Mishima—after becoming fascinated by the taste and health benefits of fermented milk in Inner Mongolia—created Japan’s first lactobacillus beverage. More than a century later, Calpis remained the top-selling lactic acid drink in Japan, with a brand story and consumer trust that are incredibly hard to manufacture from scratch.

Asahi also reorganized itself to match what it was becoming. In 2011, it changed its name to Asahi Group Holdings, moved to a holding company structure, and established Asahi Breweries Ltd as a subsidiary—an explicit admission that the future wasn’t “a beer company with side businesses,” but a diversified beverage-and-food group.

The roll-up continued. In May 2013, Asahi expanded its New Zealand footprint with the purchase of the retail chain Mill Liquorsave. It also picked up Australian craft brands and assets, acquiring Cricketers Arms and later Mountain Goat Brewery in 2013 and 2015.

These weren’t yet the kinds of moves that redefine a company overnight. But they mattered in a different way. Australia and New Zealand became Asahi’s training ground: how to run businesses outside Japan’s unique market structure, how to manage foreign brands, and how to integrate acquisitions without breaking what made them valuable.

And that learning would matter soon. Because the truly transformational M&A—the kind that changes your place in the global industry—was still ahead. All it needed was the right window to open.

VII. The AB InBev Opportunity: Europe Acquisition Blitz (2016–2017)

In corporate strategy, you rarely get a clean opening—an obvious moment when great assets are forced onto the market, on a deadline, by a seller who has to get a deal done. Asahi got that moment in 2016. The world’s largest brewer, AB InBev, was chasing an even bigger prize: SABMiller. Regulators would only approve the merger if AB InBev sold off major European businesses. Asahi was ready to be the buyer.

The backdrop was AB InBev’s roughly $100 billion bid for SABMiller, a combination that would create a beer superpower with around 30% of global beer volume. In Europe, that kind of consolidation set off every antitrust alarm. To get the deal through, AB InBev agreed to divest a meaningful chunk of SABMiller’s European footprint—exactly the kind of high-quality, hard-to-replicate portfolio that almost never becomes available.

As one banker put it at the time, this was “a unique opportunity to acquire a portfolio of leading European premium and craft beer brands,” transforming Asahi from an Asia-Pacific focused brewer into a global premium player.

The first strike came fast. In April 2016, AB InBev agreed to sell its Dutch business Grolsch, Italy’s Peroni, the UK’s Meantime, and SABMiller Brands UK to Asahi. The price: €2.3 billion. The deal closed on 12 October 2016. For Asahi, it wasn’t just an expansion—it was a statement. These were European brands with real equity, real distribution, and real pricing power.

And then the real meal appeared.

As the SABMiller integration progressed, even more assets had to be carved out. Asahi agreed to acquire the former SABMiller businesses and related assets across Poland, the Czech Republic, Slovakia, Hungary, and Romania—an acquisition valued at about $7.8 billion, at the time expected to close in the first half of 2017 pending approvals. When the dust settled, the deal closed on 21 December 2016, and it became the largest overseas beer acquisition ever made by a Japanese brewer.

What did Asahi get? A set of brands that aren’t just “strong,” they’re historic. Pilsner Urquell—the original pilsner, first brewed in 1842. Velkopopovický Kozel. Topvar. Tyskie. Lech. Dreher. Ursus. In one set of transactions, Asahi went from having a presence in Europe to owning pillars of multiple national beer markets.

Asahi’s own framing was clear: paired with Super Dry, and now with Peroni and Grolsch, the company aimed to establish “a unique position as a global player,” centered on a premium brand portfolio designed for sustainable growth.

It didn’t win those assets by being the only bidder. Asahi beat competition from Bain Capital, Jacobs Holding AG, and PPF Group. And it paid up. The company had previously indicated it had budgeted roughly $3 billion to $4 billion for overseas acquisitions, but competition forced it to revise its ceiling. On valuation, the Eastern Europe transaction implied about 14.8 times EBITDA—on the high end for brewing assets in mature markets. Peroni and Grolsch were similarly expensive, at around 15 times EBITDA.

So why pay that kind of premium?

Because Japan’s demographics were turning into an existential problem for any brewer overly dependent on the home market. The domestic category was mature, and the population was shrinking. Asahi—and every other major Japanese brewer—needed growth engines elsewhere. Europe offered scale, premium positioning, and durable local champions.

Asahi also argued the math would change its company profile. In October 2016, overseas assets were about 16% of sales. With the European acquisitions, Asahi claimed overseas markets could rise to around a quarter of sales.

Most importantly, the deals gave Asahi what its strategy had been building toward for years: a premium-led international portfolio with leadership positions in key markets. Over time, that translated into major share positions in places like the Czech Republic, Poland, Romania, and Italy.

For investors, the 2016–2017 run is the cleanest example of Asahi’s playbook: spend years building the capability and balance sheet to operate globally, then move aggressively when the market hands you a rare, regulator-created fire sale. AB InBev had deadlines. Asahi had conviction. And for a brief moment, European beer history was available at a price—high, but possible.

VIII. Completing the Puzzle: Carlton & United Breweries (2019–2020)

AB InBev’s SABMiller hangover didn’t end in Europe. The debt load from that mega-merger kept forcing assets onto the market, and it created another opening with huge strategic value for Asahi: Australia.

The prize was Carlton & United Breweries—CUB—one of the two dominant brewers in the country and, effectively, a cornerstone of Australian beer. In July 2019, AB InBev agreed to sell its Australian subsidiary to Asahi Group Holdings for A$16 billion (about US$10.8 billion), with AB InBev planning to use the proceeds to pay down debt tied to the SABMiller deal.

For Asahi, this wasn’t a random geographic add-on. Australia and New Zealand had already become its operating “home base” outside Japan through Asahi Beverages. CUB would turn that base into a fortress.

The transaction still had to clear two major gates: the Australian Competition & Consumer Commission and the Foreign Investment Review Board. The ACCC, in particular, wasn’t going to rubber-stamp a deal that could concentrate too much power in a market where a handful of brands drive most of the volume. In December 2019, the regulator raised concerns that the combined business could raise cider prices and reduce competition in beer. Its solution was straightforward: divest brands. The ACCC ultimately approved the acquisition after Asahi agreed to sell off two beer brands and three cider brands, concluding that the divestments would be enough to address competition concerns and give another player a meaningful foothold in a concentrated industry.

Once cleared, what Asahi was buying was more than capacity—it was culture. CUB’s lineup reads like a map of Australian beer identity: Victoria Bitter, Carlton Draught, Foster’s Lager, Great Northern, Resch’s, Pure Blonde, and Melbourne Bitter, among others. Operationally, it was a big, real company: headquartered in Melbourne, employing nearly 1,600 people across five breweries and offices around the country. CUB had come under AB InBev only recently, in 2016, as part of the SABMiller takeover.

The strategic picture snapped into focus when you looked at the combined portfolio. Under one roof, Asahi could now span everything from global premium imports to local Australian powerhouses—Asahi Super Dry alongside Great Northern and Carlton Draught, with brands like Peroni, Corona, VB, Carlton Dry, Pure Blonde, Mountain Goat, Vodka Cruiser, Somersby Cider, and Woodstock Bourbon also in the mix.

In May 2020, the Foreign Investment Review Board gave its approval. The deal meant Asahi would end up with roughly 48.5% of the Australian beer market—an enormous position—competing primarily against the other major player, Kirin-owned Lion.

Asahi framed the move as part of a broader ambition: to be “a value creator globally and locally,” leaning into high value-added brands, premiumization, and cross-selling across its growing stable of premium labels.

And then came the part nobody could have planned for. The acquisition closed during the early months of COVID-19. Asahi completed the purchase on June 1, 2020—closing one of the largest deals in its history in the middle of a global shutdown. AB InBev CEO Carlos Brito publicly credited the teams on both sides for staying focused and getting the transaction over the line despite the chaos.

After closing, Asahi Beverages combined its two alcohol businesses—Carlton & United Breweries and Asahi Premium Beverages—with the merged operation running under the CUB name. The message was clear: Asahi wasn’t just passing through Australia. It was committing to it for the long term.

With CUB in hand, Asahi’s transformation was no longer a thesis—it was a fact. A company that not long ago generated under 16% of sales from overseas now held major positions across Europe, a leading share in Australia, and a premium-led portfolio that stretched across continents.

IX. The Modern Empire: A Global Premium Portfolio (2020–Present)

By the 2020s, the transformation was complete. Asahi Group Holdings, Ltd. wasn’t just the company that saved itself with Super Dry, then went shopping in Europe and Australia. It was now a global beverage group with a portfolio anchored in beer, but deliberately expanded into alcohol and non-alcohol beverages, plus food. Founded in Japan in 1889, Asahi had always talked about innovation and quality. What changed was the scale: the company had stitched together iconic brands and brewing expertise from around the world, including breweries with histories measured in centuries.

In Europe, Asahi had become more than an owner on paper. Building on that deep brewing heritage, it operated 19 production facilities across 8 countries and served as custodian of some of the best-known beer brands in the world: Asahi Super Dry, Pilsner Urquell, Peroni Nastro Azzurro, Grolsch, and Kozel.

The numbers told the same story the portfolio did. In 2024, revenue grew 2.1% year-on-year, largely driven by price increases tied to premiumization and strategic price revisions. On an actual currency basis, revenue grew 6.2% year-on-year. Across its five global brands, total sales volume rose 5% year-on-year. Super Dry—still the flagship priority—grew 10%, driven mainly by sales expansion in Asia and Europe.

Financially, Asahi looked like a company that had gotten its footing. With stronger cash-flow generation, its Net Debt/EBITDA ratio declined to 2.5x at the end of 2024, in line with its financial soundness policy guidelines. And in 2024, Asahi hit record highs across earnings categories, including revenue and core operating profit, with regional businesses complementing each other even in a tough environment.

Then came the next milestone: North America.

In January 2024, Asahi announced a deal to acquire Octopi Brewing, a contract brewer and co-packing facility based in Waunakee, Wisconsin. The move had been foreshadowed: in late 2022, Reuters reported that Asahi and other Japanese brewers were hunting for brewing capacity in North America. Octopi—one of the country’s largest craft-focused contract brewing companies by volume—fit exactly what Asahi was looking for.

Asahi Europe & International, the group’s international arm, positioned the acquisition as a way to accelerate growth and extend Asahi’s global ambitions—especially for Super Dry, which would now be brewed in the U.S. for the first time. Beyond speed and scale, Asahi highlighted sustainability benefits too: a North American production footprint could reduce emissions and support its ambition to become carbon neutral across its wider supply chain by 2050.

At the same time, Asahi was preparing for where beverage consumption was heading, not where it had been. Asahi Europe & International set an ambition for alcohol-free products to reach 20% by 2030, as the market for alcohol-free beverages continued to expand.

One example is Asahi Dry Zero, a non-alcohol beer-like beverage built around a “triple zero” promise: zero alcohol, zero sugar, and zero calories. Asahi describes it as delivering a dry taste and creamy head designed to feel closer to a true beer, and it has continued developing technology to make non-alcohol beer-like beverages as satisfying as their alcoholic counterparts.

But modern scale brings modern vulnerabilities. In late 2025, Asahi faced a major operational disruption following a ransomware attack in Japan. After disclosing on September 29 that a “system failure caused by a cyberattack” had knocked out ordering, shipping, and call center systems across its Japanese operations, the company later said the attackers may have accessed personal data tied to almost 2 million people.

The immediate business impact was severe. Production at multiple factories was interrupted, and core logistics and sales systems were forced offline. Beer production resumed within about a week, but distribution problems lingered, leading to widespread shortages across Japan. Asahi Breweries resumed production at all six domestic factories from October 2, and partial shipments of Asahi Super Dry restarted. Asahi said its overseas operations—including global brands such as Fuller’s, Peroni, Pilsner Urquell, and Grolsch—were not impacted.

Reuters reported that Asahi’s domestic beverage and food divisions saw a 10–40% decline in sales in October versus the prior year.

It was an uncomfortable reminder that even a company with century-old physical operations can be brought to a halt by a failure in the invisible layer underneath: software, systems, and security.

X. Strategic Playbook: Lessons from Asahi's Transformation

Big turnarounds can look mysterious from the outside. Asahi’s isn’t. Under the drama, it’s a repeatable playbook—one that shows up in product strategy, in dealmaking, and in how the company chose to position itself.

The Asahi story yields several transferable insights for investors and strategists:

Lesson 1: Consumer-Led Innovation as Survival Mechanism

When you’re dying, you’re finally willing to hear the truth.

Asahi didn’t turn itself around by “optimizing” what it already had. It started with a blunt question to the market, and got a brutal answer back: 98% of surveyed beer drinkers told Asahi to change the taste.

Inside the company, the ask sounded self-contradictory. Consumers wanted a beer that felt rich, but left no aftertaste. Asahi’s technicians initially argued it wasn’t chemically possible. But Murai’s point was simple: “impossible” was just another word for “we’re not trying hard enough.”

The broader lesson is the one Super Dry made famous: category creation beats category competition. Asahi didn’t out-Kirin Kirin. It invented dry beer, reframed what “good” tasted like, and forced the rest of the industry into the Dry War on Asahi’s terms.

Lesson 2: Opportunistic M&A Requires Preparation

Asahi’s overseas expansion looks, in hindsight, like perfectly timed opportunism: Europe in 2016–2017, then CUB in 2020. But these weren’t lucky accidents. They were the payoff from years of groundwork—building financial capacity, learning how to integrate through smaller acquisitions, and staying clear-eyed about what kind of company Asahi wanted to become.

So when AB InBev’s regulatory commitments forced it to sell real European crown jewels, Asahi wasn’t scrambling. It was ready. And it didn’t “wait and see.” It moved decisively, including by submitting a fully financed, binding offer while other potential buyers were still floating non-binding bids.

The lesson: the window only opens for a moment, but the ability to jump through it is built over years.

Lesson 3: Premiumization Enables Margin Expansion

A beer is a beer—until it isn’t.

Asahi consistently chose the premium end of the market: Super Dry was positioned above the existing domestic mainstream. The European acquisitions layered in brands like Peroni Nastro Azzurro, with decades of cachet and pricing power.

In commodity industries, premiumization isn’t just marketing. It’s how you defend margins when volumes wobble and competitors fight for share. If you can’t win on scale, you win on willingness to pay.

Lesson 4: Multi-Brand Portfolio Management

Once you start buying great brands, the job changes. You stop being “a brewer” and become a curator.

Asahi now runs a portfolio that spans centuries of heritage—Grolsch dates back to 1615—alongside modern category-defining products like Super Dry, launched in 1987. Managing that mix means walking a tightrope: protect local identity and brand meaning, while still capturing the benefits of global scale and operational discipline.

Lesson 5: Demographic Decline as Forcing Function

Japan’s shrinking, aging population isn’t a temporary downturn. It’s the map.

Asahi could have tried to grind it out at home, fighting for points of share in a market that wasn’t going to expand. Instead, it treated demographics as the forcing function to internationalize—turning a structural headwind into a strategic mandate. Overseas markets now deliver over half of revenue and close to 60% of operating profit.

The lesson is uncomfortable, but powerful: sometimes the best growth strategy is admitting your core market won’t save you—and building the next one before you’re forced to.

XI. Porter's Five Forces & Hamilton's 7 Powers Analysis

Porter's Five Forces

1. Threat of New Entrants: LOW

If you’re wondering why Japan’s beer market looks so stable, it’s because it’s built like a fortress. Four major brewers control roughly 95% of domestic volume, a structure that’s held since the post-war era. These companies don’t just have brands; they have muscle memory—decades of distribution relationships, shelf presence, and institutional trust that are brutally hard to replicate.

And the barriers aren’t subtle. Brewing at scale requires huge capital investment. Getting route-to-market access—especially in Japan’s fragmented retail environment—takes years of relationship-building. On top of that, alcohol regulation and licensing add friction everywhere Asahi operates. The same playbook shows up in Australia and across much of Europe: mature markets with incumbents, entrenched distribution, and high costs of entry.

2. Bargaining Power of Suppliers: MODERATE

Brewers buy agricultural commodities, and commodities come with commodity problems. Barley and hops are broadly interchangeable, but prices can swing with weather, climate variability, and crop cycles. Packaging and inputs bring their own supply-and-cost pressures, too.

Asahi’s global footprint helps here. Scale creates purchasing leverage, and Asahi has formalized that advantage through its global procurement structure, including the launch of Asahi Global Procurement Pte. Ltd. Still, leverage doesn’t eliminate exposure—currency moves and global input volatility remain real risks.

3. Bargaining Power of Buyers: MODERATE-HIGH

On the customer side, the power sits with the gatekeepers. Large retailers—supermarkets and convenience store chains—can push hard on pricing and promotion because they control access to volume and visibility. On-premise buyers like bars and restaurants are more fragmented, but that channel has been shrinking as a share of consumption.

Brand strength gives Asahi some insulation, especially at the premium end. But in value tiers, private-label beer and price-sensitive alternatives keep pressure on margins.

4. Threat of Substitutes: MODERATE-HIGH

Beer doesn’t just compete with beer. It competes with everything people can drink: wine, spirits, and ready-to-drink products all fight for the same occasions. And the substitution trend that matters most right now isn’t another alcohol category—it’s no alcohol.

Non-alcoholic beverages are increasingly positioned as lifestyle choices, and younger consumers are drinking less alcohol overall. In Japan, that dynamic is amplified by demographics: an aging population and declining alcohol consumption.

Asahi’s response has been to ride the shift instead of denying it. Asahi Europe & International has set a target for alcohol-free products to reach 20% by 2030, aligning its portfolio with where consumption is moving.

5. Competitive Rivalry: HIGH

High barriers to entry don’t mean low competition. They often mean the opposite: the same players fight each other, relentlessly, for share.

In Japan, the big four—Kirin, Asahi, Sapporo, and Suntory—control about 96% of the market, and rivalry spans premium beer, value beer, low-malt alternatives, and non-alcohol options. Europe and Australia bring similar intensity: entrenched incumbents, strong local loyalties, and constant promotion and innovation battles.

Hamilton's 7 Powers Analysis

Scale Economies: Asahi benefits from scale in procurement, production, and distribution. Its major platforms in Japan, Europe, and Australia allow it to spread costs, run global brand playbooks, and transfer operational know-how across regions.

Network Effects: Beer doesn’t have classic network effects, but distribution can behave like one. Deep retail and on-premise relationships create practical switching friction for partners, even if consumers themselves can change brands easily.

Counter-Positioning: Super Dry is the textbook example. Asahi created a new category—dry beer—that reframed consumer expectations. Incumbent rivals could respond, but not without tradeoffs. Kirin’s later launch of Ichiban Shibori competed directly, yet it also cannibalised profits from Kirin’s own Lager Beer brand.

Switching Costs: Moderate. For consumers, switching brands is easy. But in B2B—tap handles, menu placements, promotional commitments—relationships and contracts create stickiness over time.

Branding: This is Asahi’s strongest power. It owns a portfolio where the brands carry real meaning: Super Dry’s innovation-led identity alongside European heritage labels like Pilsner Urquell. That combination supports premium positioning and makes differentiation harder to copy.

Cornered Resource: Asahi’s proprietary yeast strain, Asahi #318, is a genuine technical asset tied directly to Super Dry’s signature profile. And while process and ingredients can be imitated, centuries of heritage in brands Asahi owns cannot be recreated.

Process Power: Asahi has an embedded capability for consumer-led product development. The Super Dry story isn’t just a lucky hit; it reflects a repeatable internal process—listen closely, translate insight into product design, and then operationalize it at scale.

Competitive Position Summary

Asahi competes in markets that tend to be structurally resilient—oligopolies with high barriers to entry—and it often holds leadership or strong #2 positions across its key regions. The long-term challenge is less about defending against new entrants and more about winning inside maturity: managing flat or declining category volumes while continuing to premiumize and expand into alcohol-free and adjacent segments.

XII. Key Metrics and Investment Considerations

If you’re looking at Asahi as a long-term investment, you can boil a very complicated global beverage business down to three signals that matter most. They’re not perfect, but together they tell you whether the strategy is working: can Asahi grow its premium brands outside Japan, can it keep lifting price through mix, and can it do all that without overstraining the balance sheet?

1. Premium Brand Volume Growth (Outside Home Market)

The cleanest proof that Asahi’s global pivot is real is whether its flagship brands keep gaining traction outside Japan. In 2024, total sales volume across its five global brands rose 5% year-on-year. Asahi Super Dry grew 10%, driven mainly by expansion in Asia and Europe. That’s the thesis in motion: the European and Australian deals weren’t about buying volume—they were about building a premium, exportable brand engine.

2. Unit Sales Price (Premium Mix)

In mature beer markets, volume is rarely the friend you want it to be. Pricing and mix are. Asahi’s 2024 revenue rose 2.1% year-on-year, mainly because unit sales prices increased through premiumization and strategic price revisions. This is the heart of the model: if category volumes are flat or pressured, you want the business to get healthier anyway—by selling a better mix at better prices, not by chasing growth that doesn’t exist.

3. Net Debt/EBITDA

The other side of the “buy great assets” story is leverage. Asahi’s European and Australian acquisitions were transformative, but they also loaded the balance sheet. By the end of 2024, Net Debt/EBITDA had declined to 2.5x, in line with the company’s financial soundness guidelines. Deleveraging matters because it buys Asahi options: flexibility to invest, resilience in a downturn, and the ability to act if another rare window opens.

Material Risk Considerations

Demographic Headwinds: Japan’s declining and aging population is a structural drag on domestic alcohol volumes. The company has to keep premiumizing at home while making the international business big enough to matter.

Currency Exposure: With major operations outside Japan, Asahi’s results can swing with moves between the yen and the euro, Australian dollar, and other currencies.

Cybersecurity: The September 2025 ransomware attack wasn’t theoretical risk—it disrupted production and distribution in the real world. Asahi is investing in stronger security, but the episode showed how vulnerable physical operations can be to digital failure.

Regulatory Changes: Alcohol taxes and regulations vary by country and can reshape demand and category preferences quickly, especially in price-sensitive segments.

The arc of Asahi—from a brewer on life support to a global portfolio owner—shows what happens when consumer insight, product innovation, and disciplined capital allocation line up at the right moment. The company that once needed bankers sent in to run it now stewards some of the most storied beer brands in the world. For investors, the question is whether the next phase—premium growth, alcohol-free expansion, and operational resilience—can deliver the same kind of value creation.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music