M3 Inc.: Japan's Healthcare Platform Empire

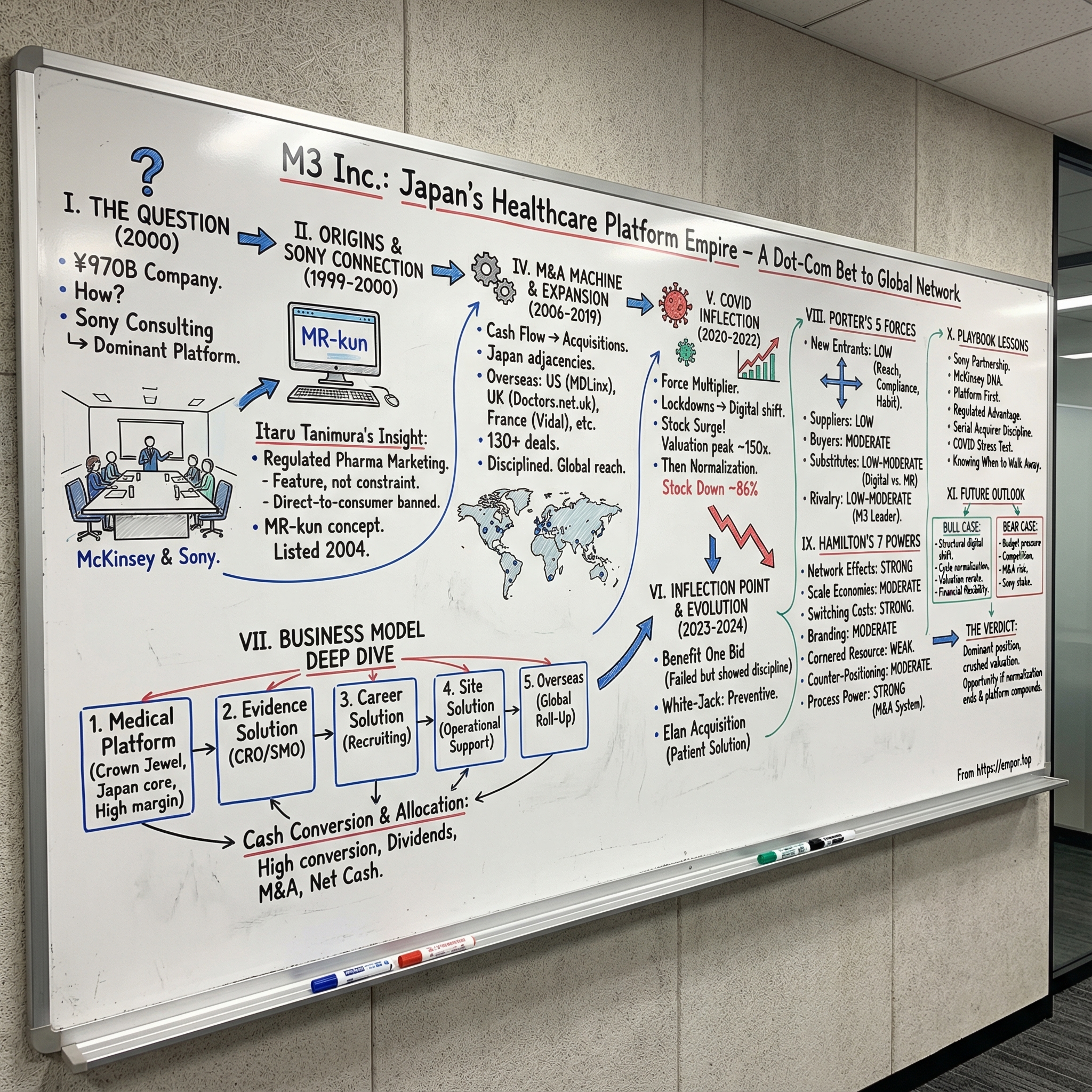

I. Introduction: The Question Behind a ¥970 Billion Company

Picture Tokyo in 2000. The dot-com bubble was frothing, and most internet ambition still pointed toward consumers—shopping, chat, portals, games. But Itaru Tanimura, a 43-year-old McKinsey partner, was drawing up something stranger: a digital bridge between Japan’s pharmaceutical companies and Japan’s doctors.

M3 was founded that year by Tanimura. It started as an online medical community for Japanese physicians, backed early by Sony Corporation—an investment that sounds odd until you remember what the opportunity was. In Japan, pharmaceutical marketing is tightly regulated. Drug companies can’t just advertise to the public. For decades, the default distribution channel for information was the MR: the medical representative who physically visited doctors, office by office, hospital by hospital.

So here’s the question that sits at the center of this story: how did a consulting relationship with Sony turn into Japan’s dominant healthcare information platform—so dominant that it became the first company incorporated after 2000 to make it into the Nikkei 225? And how did that platform grow from a domestic physician community into a global network with over 330,000 physician members in Japan and more than 6.5 million worldwide?

The answer is a mix of three forces.

First, platform network effects in a highly regulated industry—where trust, identity verification, and compliance aren’t features, they’re the moat.

Second, an acquisition engine run with consulting-firm discipline. Over time, M3 used its cash flows to expand into adjacent healthcare businesses and to assemble much of its overseas footprint through M&A.

Third, a stock chart that looks like a COVID-era parable. When lockdowns pushed medical marketing online, M3’s growth and margins surged, and the market bid the shares to extraordinary levels. Then came normalization, consolidation, and investor whiplash. From its peak, the stock is down roughly 86%.

Today’s M3 spans five reporting segments: Medical Platform, Evidence Solution, Career Solution, Site Solution, and Overseas. It reaches nearly every doctor in Japan and a growing share of doctors globally. And yet it trades at a valuation that implies deep skepticism about what comes next.

In this episode, we’ll walk through how Tanimura’s insight about regulation created an enduring advantage, how M3 turned a single product into a compounding platform, how COVID both blessed and cursed the business, and what the market might be missing—whether this drawdown reflects permanent damage, or the kind of mispricing that shows up only when a great company hits an ugly transition.

II. The McKinsey Origins: Itaru Tanimura and the Sony Connection (1999-2000)

M3 didn’t start in a garage. It started in McKinsey conference rooms.

Itaru Tanimura—future founder and CEO—spent twelve years at the firm and made partner by 1999. That same year, while working on a project for Sony, he floated an idea that would sound counterintuitive coming from an entertainment company: build an internet business in healthcare.

The timing and the market structure mattered. In Japan, pharmaceutical marketing is tightly regulated. Direct-to-consumer drug advertising is prohibited. And that regulation funneled almost all “marketing” through a single, deeply entrenched channel: MRs, the medical representatives who physically visited doctors to share information about new medicines.

On paper, it looked like brute-force coverage. Japan had roughly 300,000 physicians. Pharma companies employed tens of thousands of MRs—MR headcount even climbed from about 49,000 in 2000 to over 61,000 by 2010. In practice, those visits often amounted to a few hurried minutes. MRs spent their days commuting, waiting in hospital lobbies, and fighting for scraps of attention from physicians who were already over capacity. And for all that cost, the system still struggled to deliver what mattered most: adequate information on product safety and effectiveness.

Tanimura’s insight was simple, and it used regulation as a feature, not a constraint: if you could create a digital place where real, credentialed physicians gathered—and you could verify that they were, in fact, physicians—then pharma companies could share compliant drug information online at scale. The very rules that made consumer advertising impossible would make a verified doctor-only channel incredibly valuable.

This is where Sony enters the story in a way that makes more sense than it first appears. Sony’s internet subsidiary, So-net, was hunting for meaningful opportunities in the emerging online economy. Backing Tanimura’s concept offered Sony a credible foothold in a massive, under-digitized industry. The early company was even called So-netM3, Inc. before changing its name to M3, Inc. in January 2010.

Sony’s support wasn’t just money. In a conservative ecosystem like Japanese healthcare, credibility is oxygen—and having a household-name sponsor mattered.

Even the name reads like it came out of a strategy deck: M3 stood for medicine, media, and metamorphosis. The pitch was transformation—using information and connectivity to change how healthcare works.

Over time, the relationship evolved rather than dissolved. Sony owned 74.8% of M3 after the IPO, then gradually reduced its stake—to 60% by 2006, 50% by 2013, 39% by 2015, and down to 34% in January 2017—where it has remained stable since. Tanimura held a 2.9% stake while serving as president. The pattern is telling: Sony stepped back, but didn’t walk away, leaving M3 room to operate independently while keeping the strategic connection intact.

And the McKinsey imprint didn’t stay in the origin story—it became part of the operating system. Tanimura brought consulting-style rigor to planning, capital allocation, and deal evaluation. M3 would grow aggressively, but not in the classic “growth at all costs” mode. Profitability and returns mattered early, and that discipline would become a competitive advantage once the company began compounding through acquisitions.

III. Building the Core Platform: MR-kun and the Physician Network (2000-2005)

M3’s first real breakthrough wasn’t some flashy consumer app. It was a very specific solution to a very specific problem: how do you get regulated drug information to busy physicians, at scale, without breaking the rules—or the budget?

The answer became MR-kun, an internet-based communication tool designed to support the provision of information from MRs (medical representatives) to doctors. Even the name was a bit of positioning. “Kun” is a friendly Japanese honorific, and that tone mattered. MR-kun wasn’t framed as “we’re replacing the sales rep.” It was framed as “we’re making the sales rep more useful.”

Underneath the friendly wrapper was a clean, monetizable model. Doctors joined the platform to access medical information and services. Pharmaceutical companies paid to promote their drugs and deliver approved content to those verified physicians. Contracts were typically project-based, often running six to twelve months. Pricing blended a fixed project fee, recognized over time, with volume-based fees tied to how much content was delivered. Some projects were exclusive, others shared—depending on how much a pharma company wanted to pay for differentiation.

And almost immediately, the flywheel started to spin.

Every additional physician made the platform more valuable to pharma companies, because reach is everything in this category. Every additional pharma campaign made the platform more valuable to physicians, because it meant more information, more updates, more reasons to keep coming back. In a market where “close to universal” doctor coverage is a competitive weapon, M3 was building exactly the asset that would be hardest for anyone else to replicate.

The financial profile reflected that. For a dot-com era startup, MR-kun was profitable fast—posting a 33% operating margin in the year to March 2004, before the company even went public. Margins would go on to peak at 48% in March 2008, back when revenue was still much smaller—an early signal that this wasn’t a brittle internet business. It was a toll road.

The public markets noticed. M3 listed on Tokyo’s Mothers exchange for startups in 2004, then graduated to the Tokyo Stock Exchange’s First Section in 2007. Along the way, it became publicly traded under ticker 2413, raising roughly ¥3 billion at the IPO.

But the real product wasn’t just “digital brochures.” Compared to an in-person visit, the platform could measure engagement—what content physicians viewed, how long they spent, and what they did next. In pharmaceutical marketing, that kind of feedback loop is gold. It turns outreach from guesswork into something closer to an instrument panel.

Still, the most important ingredient was trust. M3 took pains to verify every physician’s identity and credentials. In a compliance-heavy industry, that verification wasn’t a nice-to-have—it was the moat. It meant pharma companies could be confident their messaging was reaching licensed medical professionals, in a way aligned with Japan’s strict marketing rules.

By the mid-2000s, M3 had built something rare in Japanese healthcare: a digital platform that was growing, highly profitable, and steadily moving toward near-universal physician reach. The engine was running. Now it just needed somewhere bigger to go.

IV. The M&A Machine: From Small Tuck-ins to Global Expansion (2006-2019)

Once MR-kun proved the model, Tanimura made a second bet—arguably the one that turned M3 from a great Japanese business into a global one: use the cash the core platform threw off to buy growth.

The logic was straightforward. In Japan, M3 pushed into adjacent healthcare businesses—recruiting for medical professionals, market research, and clinical trial-related services. Overseas, it went hunting for the same kind of asset it had built at home: trusted, verified physician communities and the services that monetize them.

M3’s first acquisition came early, in 2002. It bought MDLinx in the U.S. in 2006. But the real acceleration started in 2010. From there, M3 became a programmatic acquirer—roughly 130 deals since 2010, averaging close to ten acquisitions a year. On the surface, that cadence can read like a warning label. Plenty of companies use M&A to mask slowing growth, overpay for “synergies,” and leave shareholders with a pile of goodwill and regret.

M3’s record looks different. Deal disclosures from FY17 to FY24 covering about ¥97 billion of enterprise value suggest the company typically bought businesses at modest multiples—about 1.6x EV-to-sales and 12.4x EV-to-EBIT, on average. More importantly, the businesses didn’t just get consolidated and forgotten. Many continued to grow quickly under M3’s ownership, which is the whole point of the strategy: buy assets with strong positions, then help them compound inside a larger platform.

The overseas playbook followed a clear pattern: acquire leading physician platforms in key markets, plug them into M3’s global network, and then sell more services across that footprint—pharma marketing support, research, recruitment, and beyond.

The early steps came quickly. In 2006, M3 acquired MDLinx.com in the U.S. and Medigate.net in Korea. In 2010, it acquired EMS Research in the U.K., and positioned its international operations under the M3 Global Research name. Then, in 2011, it landed one of the most important pieces: Doctors.net.uk.

That deal was classic M3. Doctors.net.uk was the largest physician network in the United Kingdom, with more than 180,000 physician members. Buying it instantly gave M3 a verified base of medical professionals in a major pharma market—exactly the kind of audience that powers everything from compliant marketing to market research and recruiting.

From there, the European build-out continued. In France, M3 acquired Vidal in 2016. Vidal is an online pharmaceutical database that physicians subscribe to—and its credibility runs deep, because it was long known as a printed medical reference before it became digital. This was M3’s strategy at its best: not just buying software or traffic, but buying trust.

By this point, a key fact became unavoidable: M3’s overseas business was assembled almost entirely through acquisitions. So the right question isn’t “did they do a lot of deals?” It’s “did those deals create a real, profitable growth engine?”

The evidence suggests yes. The overseas business became a meaningful, durable platform with leading medical properties in multiple countries. Regionally, sales were split across North America, Europe, and other markets in Asia. And crucially, M3’s dealmaking showed unusual restraint. Instead of swinging for splashy, expensive targets, it repeatedly bought at reasonable prices and focused on integration and organic growth afterward. Cohort results point to that compounding effect: the earliest businesses continued to grow well over the following decade, and the large wave of acquisitions from 2011 to 2016 also delivered strong organic growth in the years that followed.

By the end of this era, M3—together with its subsidiaries and affiliates—operated across the U.S., Europe, South Korea, Spain, France, India, China, Germany, and Japan. That footprint made it something rare: a healthcare information and services company with verified physician panels across many of the world’s most important pharmaceutical markets.

And it set the stage for what came next—because when COVID hit and the world suddenly needed “digital-first” healthcare communication, M3 didn’t have to pivot. It was already there.

V. The COVID Inflection: Boom and Bust (2020-2022)

COVID hit M3 like a force multiplier.

The company had spent two decades building the exact thing the world suddenly required: a compliant, verified way for pharmaceutical companies to reach doctors without showing up in person. When lockdowns made MR visits impractical or impossible, a huge portion of pharma communication moved online—fast. And in Japan, there was one obvious place for that activity to land.

By this point, M3 wasn’t a single domestic website anymore. It had grown into a network of roughly 40 subsidiaries and affiliates, including MDLinx in the U.S. and Doctors.net.uk in Britain. Across those platforms, M3 connected pharma companies with physicians and helped deliver medical information digitally—precisely the kind of “no physical contact required” infrastructure that suddenly went from convenient to essential.

The stock market didn’t just notice. It rushed in. M3’s shares surged, becoming one of the strongest performers in the Nikkei 225 and turning Tanimura into a billionaire on paper. It was the perfect narrative for that moment in time: high-quality, asset-light, platform economics—plus a global crisis that pushed an entire industry toward digital overnight.

The financials backed up the excitement. In the six months ended September 30, 2020, M3 reported sales of 75,022 million yen, up 21.9% year over year, and operating profit of 23,931 million yen, up 44.6%. Profit rising roughly twice as fast as revenue was the platform model doing what it does best: incremental demand dropping through to the bottom line with serious operating leverage.

The overseas businesses felt the same pull. COVID tailwinds drove increased demand for online services from pharmaceutical companies, particularly in APAC. In that region, segment sales reached 18,314 million yen, up 31.0% year over year, while profit jumped 90.6% to 5,083 million yen.

And then valuation ran ahead of reality.

M3 got swept up in the 2021-era global bubble in “quality growth” stocks, and its multiple expanded to levels that only make sense if you assume the surge is permanent. At the peak, the company traded around 150x forward earnings—an echo of the post-IPO days, when it was tiny and the future could be any size you wanted.

But the pandemic was a shock, not a new law of physics. As conditions normalized and in-person activity resumed, pharmaceutical marketing budgets tightened and COVID-related projects rolled off. M3 began reporting declines in net sales and operating profit tied to the waning impact of those pandemic-driven revenues.

The pain showed up most sharply in profitability. Marketing support is M3’s highest-margin business, so when that activity cools, the impact isn’t linear—it’s amplified. The post-COVID decline became dilutive to the Medical Platform segment margin, and that fed a broader investor narrative: not just “growth is slowing,” but “the best part of the business is shrinking.”

Even as revenue held up better than the stock price suggested, sentiment kept breaking down. In the fiscal year ending March 31, 2025, M3 reported revenue of 284,900 million yen, up 19.3% from the prior year. But operating profit and profit before tax fell—down 2.2% and 5.9%, respectively—driven by lower contributions from COVID-related projects and reduced pharma marketing budgets.

Management’s message was that this is a normalization cycle, not a structural collapse. The company expected the negative impact of COVID to be finished in FY2024, and for the business to normalize after FY2025—meaning results would increasingly reflect the underlying, “true” growth rate rather than the artificial peak and hangover.

The market, meanwhile, delivered a verdict in advance. From the high, the stock fell roughly 86%—one of the most violent drawdowns among major Japanese names in recent memory.

So that’s the tension coming out of the COVID era: M3 still holds a dominant position and continues to generate substantial cash flow, but the market is treating the post-pandemic comedown as evidence that the compounding machine is broken. The next question is whether this was a temporary distortion that created a rare entry point—or the moment the platform’s best days moved permanently into the past.

VI. Inflection Point: The Benefit One Bid and Strategic Evolution (2023-2024)

By late 2023, M3 was dealing with a market that no longer rewarded the “COVID winner” narrative. So it did what disciplined compounders often do when their core story gets questioned: it tried to open up a new lane.

In November 2023, M3 launched a tender offer for Benefit One, a listed leader in corporate benefits. At roughly ¥140 billion, it would have been the largest acquisition M3 had ever attempted—an unmistakable signal that the company wanted to push harder into occupational health through its White-Jack focus.

On paper, the logic was coherent. Benefit One isn’t a physician platform; it’s closer to the infrastructure behind employee wellness. The company provides corporate welfare agency services and other membership services—helping employers run benefits programs that improve efficiency and employee satisfaction. Under that umbrella, Benefit One’s health care business offers one-stop services designed to prevent physical and mental illness: health checkups, specific health guidance, health points programs, and stress check services. Preventive medicine and corporate wellness sit adjacent to M3’s core business, but the end market could be larger—and far less dependent on pharma marketing cycles.

Then the deal turned into something Japan doesn’t always do well: a real bidding war.

In December, Dai-ichi Life stepped in despite Benefit One having already agreed to M3’s lower offer. Dai-ichi Life initially proposed ¥2,123 per share, and later raised it again to lock up the acquisition. In a filing, Dai-ichi Life announced it would take Benefit One private via a tender offer running from February 9, 2024 to March 11, 2024, priced at ¥2,173 per share.

M3 had originally agreed with Pasona on a tender offer at ¥1,600 per share. And when Dai-ichi Life went higher—much higher—M3 didn’t chase.

That mattered. With ¥131 billion in net cash on the balance sheet, M3 could have stretched. Walking away was a choice, and it read like a message: management was willing to be disappointed, but not willing to destroy returns. In an era when the market was already questioning the durability of M3’s growth, protecting return on invested capital may have been the more important signal than “winning” the headline.

The attempted acquisition also put a spotlight on M3’s White-Jack Project. Historically, M3’s services centered on “treatment after the onset of disease.” White-Jack is the company’s name for expanding upstream—toward preventive medicine, maintaining health before illness develops, and ultimately pushing for reductions in healthcare costs, an issue with real social urgency in Japan. The Benefit One deal was supposed to accelerate that shift.

Even after losing Benefit One, M3 still showed it was willing to do bigger, more strategic deals—just on its terms. In October 2024, it acquired a 55% controlling stake in Elan (6099.T) for ¥35 billion via a tender offer. Elan remained listed, and it was a strong business on its own.

Elan supplies “care support sets” to hospital in-patients: daily rental and laundry of gowns, towels, and other daily necessities—items that, in the Japanese model, aren’t provided by the hospital the way they often are elsewhere. M3 expected to find synergies in Elan’s hospital relationships, which connect directly to the broader healthcare delivery ecosystem M3 has been building toward.

After consolidating Elan in October 2024, M3 created a new “Patient Solution” segment in the fiscal year ended March 31, 2025. That segment delivered revenue of 21,919 million yen and segment profit of 824 million yen—early evidence of how M3 intended to broaden beyond “information for doctors” into services that sit closer to the day-to-day operations of healthcare itself.

VII. The Business Model Deep Dive: Five Segments Explained

To really understand M3, you have to get comfortable with the fact that it isn’t one business anymore. It’s a platform at the center, plus a set of adjacent services built around it, plus a global roll-up layered on top.

By revenue, about 39% comes from the Medical Platform segment, about 29% from Overseas, and the rest from three domestic lines: Evidence Solution, Career Solution, and Site Solution. But profit tells a different story. Roughly 55% of profits come from Medical Platform, while Overseas contributes closer to 24%. The takeaway is simple: M3’s global footprint is meaningful, but Japan’s core platform is still the economic engine.

Medical Platform: The Crown Jewel

This is the business M3 was born to run: Japan’s online pharmaceutical marketing and physician platform. It’s a category killer, with roughly 50% margins at maturity and the kind of cash generation that can fund everything else.

The segment includes the original MR-kun family of services and related offerings. Through m3.com, M3 provides a suite of services for more than 320,000 physician members in Japan. Some services are designed to help doctors proactively receive continuous, frequent medical information through the platform, while others monetize that reach for corporate clients.

Medical Platform also includes marketing research capabilities built on the physician panel, and QOL-kun, which provides marketing support for non-healthcare corporates that want to advertise everyday services to doctors.

The model has become more sophisticated over time. M3 isn’t just delivering information; it’s trying to digitize and instrument MR activity and push toward data-driven marketing support. Within marketing support, sales are split roughly 67% from the legacy core, 25% from newer digital support services, and 8% from data-driven marketing support—with the newer pieces growing much faster than MR-kun itself.

Evidence Solution: Clinical Trials and Research

Evidence Solution is M3’s clinical and research engine. It includes a contract research organization (CRO) business supporting clinical development and research, and a site management organization (SMO) business that manages clinical trial operations.

The strategic connection to the platform is obvious: M3 can leverage its physician panel to support trial execution, help recruit patients, and run market research for pharmaceutical companies.

Career Solution: Healthcare Recruitment

Career Solution is the talent marketplace: human resource services for healthcare professionals. Through M3 Career, Inc., the company provides job search and placement support for physicians and pharmacists.

This segment benefits from the same distribution advantage as the core platform. If you’re already using m3.com as part of your professional life, career services become a natural add-on.

Site Solution: Supporting Medical Institutions

Site Solution moves closer to the delivery side of healthcare. It provides operational support for medical institutions and home-visit nursing services. Over time, it has expanded through acquisitions and now includes businesses such as hospice operations, podiatry clinics, and clinic management software.

Overseas: The Global Roll-Up

Overseas is the international version of the M3 playbook: medical-related marketing support, research, and career services delivered through medical professional sites in markets including the United States, the United Kingdom, China, Korea, India, France, Germany, and Spain.

Profitability isn’t uniform. Asia runs at the highest margins, Europe follows, and the U.S. is the lowest. Korea is the closest analogue to Japan: M3’s Korean business, MediC&C, looks most like the core Japanese pharma marketing business and posted the highest margin among overseas businesses at 53% in the most recent year—though on a smaller revenue base.

Cash Conversion and Capital Allocation

One of the most underrated parts of the M3 story is how efficiently it turns accounting profits into real cash—before spending on new deals. Cumulatively, the company has converted about 87% of net income into free cash flow.

That cash has been allocated with a consistent pattern. M3 has targeted a dividend payout ratio in the 20% to 30% range. From FY08 to FY24, it paid ¥64 billion in dividends and spent ¥120 billion on M&A. The remaining cumulative free cash flow—about ¥110 billion—largely stayed on the balance sheet, building net cash to ¥131 billion by March 2024.

Given the company’s recent behavior—swinging at Benefit One and completing the Elan acquisition—that war chest looked increasingly like dry powder, not a permanent feature.

VIII. Porter's Five Forces Analysis

Threat of New Entrants: LOW

To compete with M3 in Japan, you don’t just need to build a website. You need to solve several hard problems at once—starting with reach. In this market, coverage is the product. M3’s 330,000-plus registered physicians amount to near-universal penetration, and that kind of scale is incredibly difficult to replicate from scratch.

Then there’s compliance. Because pharmaceutical marketing is tightly regulated, M3’s physician verification isn’t a “trust and safety” nice-to-have—it’s the foundation of the whole business. The company goes to great lengths to confirm identity and credentials so pharma companies can confidently use the platform. Any new entrant would need to earn that same level of trust from both doctors and compliance departments, and do it before the economics work.

And finally, there’s habit. Physicians have been using m3.com for decades. It’s baked into how they consume information. Even if an alternative shows up, getting doctors to change behavior is a slow, expensive fight.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers: LOW

M3’s main inputs are technology, content, and people. The tech stack isn’t a unique constraint—compute and infrastructure are broadly commoditized. Content largely comes from the pharma clients running campaigns and from physicians themselves, which reduces dependence on any single external provider.

That leaves talent as the most meaningful “supplier.” But this is also an area where M3’s scale and track record matter: it’s a known winner in Japanese healthcare tech, which helps it recruit and retain the people needed to keep the machine running.

Bargaining Power of Buyers: MODERATE

M3’s customers—pharmaceutical companies—are large, sophisticated, and price sensitive. When budgets tighten, M3 feels it quickly, which is exactly what showed up in the post-COVID slowdown.

But the buyer story cuts both ways. Across Japan, MR headcount peaked in fiscal 2013 and has been declining since. As the traditional salesforce shrinks, pharma companies still need a way to reach doctors at scale, and that structural shift supports digital channels like M3.

Alternatives exist, but they’re limited. In pharma marketing support, M3’s direct competitors include Carenet, Medpeer, and the unlisted Nikkei Medical Online. Between the four players, the market is highly concentrated—about 98% by M3’s estimate. That concentration gives pharma companies some leverage, but not an endless menu of substitutes they can credibly switch to.

Threat of Substitutes: LOW-MODERATE

The most obvious substitute is the old model: MRs showing up in person. But it’s a substitute in decline, not in ascent. More than half of physicians have moved away from sales reps as their primary information source. Digital has become central: about 40% now rely on digital sources as their primary channel, and roughly 85% use digital as either a primary or secondary source.

That creates a persistent gap—and an opportunity. Doctors spend the most time gathering information online, yet pharma companies in Japan still direct a large share of marketing spend toward offline, sales-rep-related costs. As that spend mix catches up with doctor behavior, the “substitute” pressure should weaken.

Industry Rivalry: LOW-MODERATE

In Japan, M3 is the clear leader. The market is concentrated, but it isn’t static. M3 has said its share has slipped modestly in recent years—roughly from 70% to 65%—as Carenet and Medpeer push price competition.

Even within a tight oligopoly, the competitors aren’t identical. One rival summed up the difference neatly: “M3 is about coverage and we are about depth.” That’s actually a good sign for M3. It suggests the battlefield isn’t a pure commodity fight—M3’s scale-first strategy creates real differentiation.

Overseas is tougher. In the U.S., U.K., and across Europe, M3 often competes without the overwhelming share it enjoys in Japan, and local incumbents can be formidable. The global footprint gives M3 reach, but the competitive dynamics are simply more intense outside its home market.

IX. Hamilton's Seven Powers Framework Analysis

Network Effects: STRONG

At the heart of M3 is a classic two-sided marketplace. The more verified physicians join, the more attractive the platform becomes to pharmaceutical companies. The more pharma activity and spend M3 attracts, the more it can invest in tools, content, and services that keep physicians coming back. Over time, that loop has compounded into a global panel of more than 6.5 million physician members.

What makes M3’s network effect unusually durable is that it isn’t just about volume. The credential verification system turns “a lot of users” into “the right users.” In a regulated industry, pharma companies don’t just want reach; they want compliant access to real doctors. That quality layer strengthens the network effect because it’s harder to copy than a simple user count.

Scale Economies: MODERATE

Software platforms generally get cheaper per user as they grow, and M3 benefits from that too. The underlying technology has high fixed costs and low marginal costs, so adding more physicians or running more campaigns doesn’t require proportional spending.

But M3’s expansion hasn’t been a pure, centralized software story. Each new geography requires local operations, local relationships, and often local acquisitions—real-world costs that cap the scale benefits you might otherwise expect. You can see that in the numbers: the overseas segment has consistently lower margins than the Japanese core.

Switching Costs: STRONG

For physicians, m3.com isn’t a one-off website visit. It’s an embedded workflow: saved preferences, participation history, and professional touchpoints that would need to be rebuilt elsewhere. Habit alone is powerful in healthcare. Layer on career services and other tools, and switching becomes even less appealing.

For pharmaceutical companies, switching costs are even more structural. M3 isn’t just a media buy; it’s integrated into how marketing and sales teams operate. Major companies like Astellas and Pfizer have on-boarded their entire sales rep forces onto M3’s myMR-kun platform. Once a tool becomes the system of record for how outreach is planned and executed, “try a competitor” stops being a simple decision.

Branding: MODERATE

M3 carries a kind of institutional credibility that’s hard to manufacture. It was the first company incorporated after 2000 to be included in the Nikkei 225, a signal of legitimacy in Japan’s corporate ecosystem. And among physicians, m3.com has effectively become a default destination for professional medical information.

In healthcare, brand is less about marketing polish and more about trust. Over roughly 25 years, M3 built credibility by operating in a compliance-sensitive category without major compliance incidents or data breaches—an unglamorous but essential form of brand equity.

Cornered Resource: WEAK

Sony’s continuing stake provides a degree of strategic backing and credibility, but it isn’t a resource competitors can’t work around. And while Tanimura’s leadership clearly shaped the company, M3 has developed systems and capabilities that don’t rely entirely on one person. In other words, this isn’t a business whose advantage disappears if a single relationship or individual changes.

Counter-Positioning: MODERATE

M3 benefited from a structural trap in the old world. Before it existed, pharma companies had one dominant channel: MRs showing up in person. Even once digital proved more efficient, incumbents couldn’t instantly abandon the MR model because it would mean cannibalizing an enormous cost base and reorganizing sales motions that had been built over decades.

That creates room for M3 to win gradually. As pharma companies reduce MR headcount and shift budgets toward digital outreach step by step, M3 keeps absorbing share without requiring the industry to flip a switch overnight.

Process Power: STRONG

M3’s long-running advantage may be less about any single product and more about how it operates. A McKinsey-trained founder built an organization that allocates capital with discipline and runs M&A as a repeatable process, not a once-in-a-decade gamble.

Executing and integrating roughly nine to ten acquisitions a year while staying profitable is not a normal corporate capability. It’s a learned system: sourcing, valuing, integrating, and then letting businesses compound inside a larger platform. That embedded process—more than any one deal—is what makes M3 so difficult to imitate.

X. Playbook: Business & Investing Lessons

The Sony Partnership Model

M3’s origin story doubles as a playbook for working with a corporate parent without getting smothered by it. Sony brought capital, credibility, and—most importantly—patience, while leaving M3 room to run. Over time, Sony steadily reduced its ownership to 34%, which gave M3 more flexibility and independence, but still left it with a strategically aligned anchor shareholder.

The McKinsey-to-Founder Pipeline

Tanimura’s McKinsey background didn’t just shape the pitch; it shaped the company. M3 was built with an unusual emphasis on analytical rigor, disciplined capital allocation, and structured execution—traits that often separate “fast-growing” from “durably compounding.” That DNA showed up in the bench, too. M3’s executive team includes Aki Tomaru, based in the U.S., who leads the U.S. and European businesses. He also came from McKinsey, and joined M3 to run U.S. operations back in 2003.

Platform Before Product

M3 didn’t start by squeezing pharma budgets. It started by building the physician network. The early obsession with credentialing and verification meant the platform was compliant and trusted before monetization really ramped. In a regulated industry, that sequencing matters. Once you have the verified audience, the business models are layers you can add.

Regulated Industry Advantage

Pharmaceutical marketing in Japan is heavily restricted. You can’t advertise drugs to the general public. Most entrepreneurs treat that like a wall. M3 treated it like a moat. The rules made “doctor-only, verified, compliant” distribution incredibly valuable—and they also raised the bar for competitors, who would have to make the same expensive compliance investments just to be taken seriously.

The Serial Acquirer’s Discipline

M3 shows what programmatic M&A looks like when it’s run like a system, not a spree. The company’s approach had a few consistent features:

- Small deal sizes (often under ¥1bn), so no single acquisition could sink the ship

- Disciplined pricing (about 12.4x EV/EBIT on average in disclosed deals)

- A bias toward strategic fit over financial engineering

- Integration that was steady rather than slash-and-burn

- A willingness to walk away—Benefit One being the clearest example

COVID as Stress Test

COVID was both validation and trap. It proved how much operating leverage M3 had when demand surged, and how perfectly positioned the business was when the world went remote. But the hangover showed the other side: temporary tailwinds can get mistaken for permanent shifts. At the peak, when the stock traded around 150x forward earnings, investors were effectively assuming the COVID growth rate could last indefinitely—an error that shows up again and again in momentum-driven markets.

Knowing When to Walk Away

M3’s decision not to outbid Dai-ichi Life for Benefit One is the kind of moment that tells you what a management team really values. With substantial cash on hand, it could have chased the deal to “win” the headline. Instead, it protected return standards. In a period when investors were already questioning M3’s durability, that restraint may have been more important than the acquisition itself.

XI. Bear vs. Bull Case & Future Outlook

The Bull Case

The biggest bull argument is structural: digital pharmaceutical marketing is still taking share from the traditional MR-driven model.

In Japan, doctors have already moved online. You can reach the vast majority of physicians digitally without sending a sales rep. And yet, pharmaceutical companies still direct most of their marketing budgets toward offline, sales-rep-related activity. That mismatch is the opportunity. If budget allocations gradually catch up to how doctors actually consume information, M3 is positioned to be one of the primary beneficiaries.

The real-world environment is also pushing things in M3’s favor. Access to physicians keeps getting tighter. Many hospitals restrict visits from medical representatives, which makes doctors more selective about who they meet and reduces the time they spend with MRs overall. Those constraints don’t just hurt the old model; they actively funnel activity toward compliant, verified digital channels.

Then there’s the cycle story. Management has framed the last few years as a COVID distortion that is fading out, with the negative impact expected to finish in FY2024 and results expected to normalize after FY2025. If that’s right, the next couple of years should gradually reveal the underlying growth rate of the platform, rather than the boom-and-bust optics of pandemic-era comparables.

And finally, valuation. The stock has rerated from euphoric to sober. It now trades around 20x earnings, with a trailing free cash flow yield of about 4.4%, and roughly 22x forward earnings. If the business returns to healthy growth after normalization, that setup gives investors far more margin of safety than they had at the peak.

M3 also still has financial flexibility. With about ¥131 billion in net cash, it has the option to lean into acquisitions, pursue buybacks, or deploy capital elsewhere—without having to stretch the balance sheet.

The Bear Case

The bear case starts with a harder question: what if the slowdown isn’t just normalization?

Pharmaceutical companies remain under budget pressure, and that pressure can persist even after COVID effects fade—especially in an environment of global drug pricing scrutiny. If marketing budgets stay tight, M3’s core revenue pool may grow more slowly than investors expect. Add to that the fact that M3’s share in Japan has slipped modestly, from roughly 70% to 65%, suggesting smaller competitors can win business on price and that the category isn’t entirely immune to commoditization.

Overseas is another risk. It’s a meaningful part of revenue, but it generally runs at lower margins and faces tougher competition than M3’s Japan franchise. Continued global expansion could dilute returns rather than enhance them, especially if M3 has to spend more to win share in competitive markets.

And then there’s the built-in risk of the playbook itself. Programmatic M&A can compound beautifully, but it’s hard to sustain forever. Keeping discipline across 130-plus acquisitions is an unusually high bar. The ¥95 billion of goodwill on the balance sheet is the paper record of that strategy working so far—and also a reminder that if acquired businesses underperform, impairments could follow.

Finally, there’s a technical overhang. Sony’s remaining stake has been a long-standing source of stability and credibility, but it also concentrates governance to a degree. If Sony ever chose to further reduce or exit its position, the selling pressure alone could weigh on the stock, regardless of fundamentals.

Key Performance Indicators to Watch

If you’re tracking whether M3 is on the “bull path” or the “bear path,” three indicators matter most:

-

Medical Platform segment operating margin: This is the economic heartbeat of the company. Some margin compression post-COVID is normal. Persistent pressure would suggest deeper issues in Japan’s pharma marketing engine.

-

Physician member growth (Japan and global): M3’s advantage is the verified network. If member growth and engagement stall, it becomes harder to add new services and monetize more deeply.

-

Organic revenue growth by acquisition cohort: M3’s cohort disclosures are one of the best windows investors get into whether the M&A machine is still creating value. If post-acquisition growth deteriorates meaningfully, that’s a warning that the system is losing effectiveness.

The Verdict

M3 sits in a rare spot: a dominant position in a regulated market with real network effects, a management team that has proven it can allocate capital well, and a valuation that has been crushed by the unwind of pandemic-era expectations. The roughly 86% decline from the peak reflects both the reversal of unsustainable optimism and legitimate uncertainty about what “normal” looks like after COVID.

The core opportunity hasn’t disappeared. Digital pharmaceutical marketing should keep taking share from traditional sales forces, and M3’s verified physician network remains one of the most compliant, scalable ways to reach doctors. The open question is whether today’s price fully compensates investors for competitive pressure, execution risk, and the complexity that comes with a company that’s become, in effect, a multi-dozen-business platform conglomerate.

For investors with patience—and tolerance for near-term volatility—M3’s setup is straightforward: if normalization ends and the underlying platform keeps compounding, the current valuation could prove overly pessimistic. The company that built Japan’s healthcare platform empire isn’t going away. The only question is when the market decides to treat it like a compounder again.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music