BOC Hong Kong Holdings: The Story of China's Gateway to Global Finance

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

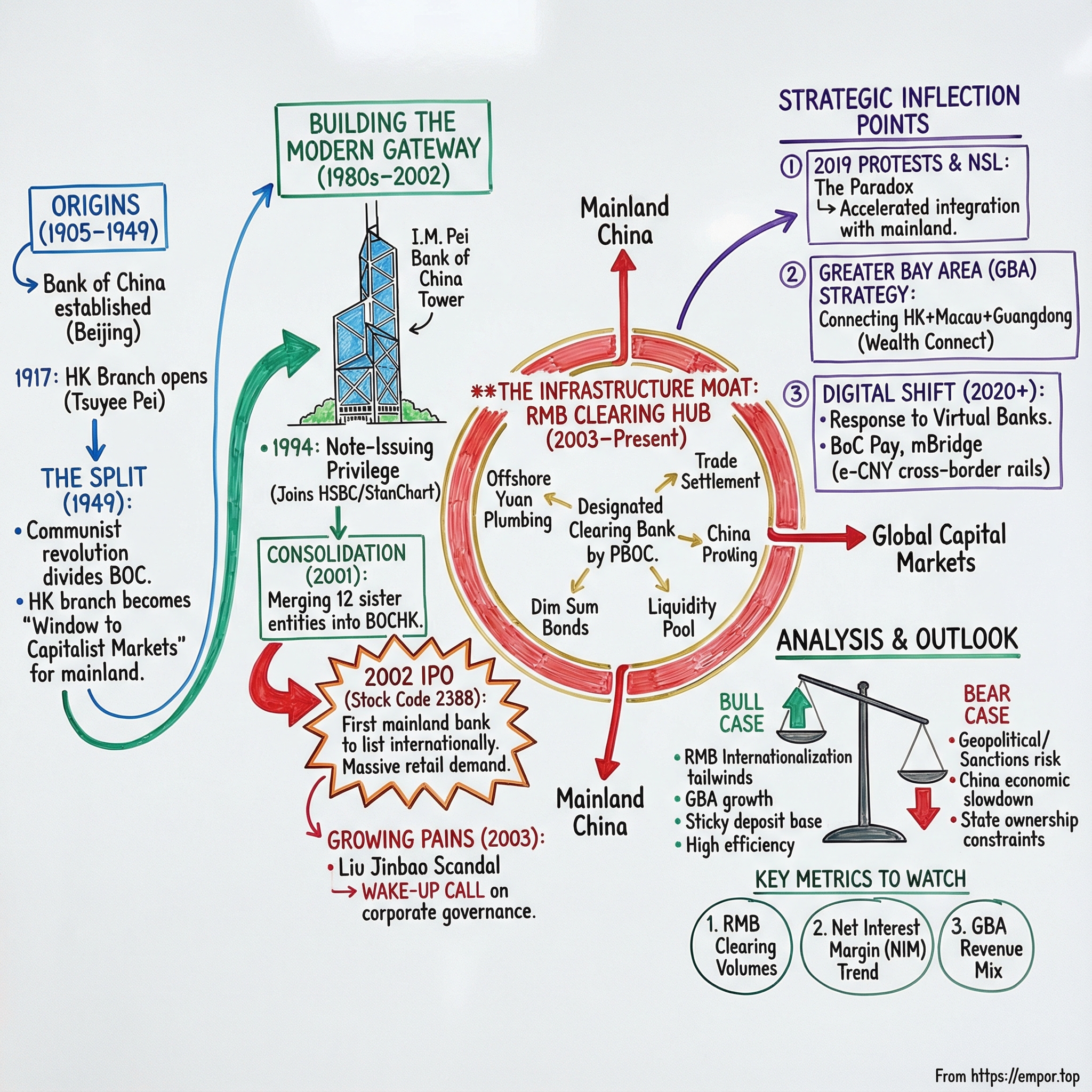

Picture the Hong Kong skyline at dusk. The geometric glass of the Bank of China Tower catches the last light, its sharp triangles stacking upward like bamboo shoots. Designed by I.M. Pei and completed in 1990, the 72-story tower wasn’t just another landmark—it was a statement. For a moment in the early ’90s, it was the tallest building in Hong Kong and all of Asia, and one of the first major supertalls outside North America to push past the 1,000-foot mark. A piece of architecture that looked forward, and a signal that China’s financial reach was beginning to extend well beyond the mainland.

Inside that tower sits one of the most strategically positioned financial institutions in the world: Bank of China (Hong Kong) Limited, or BOCHK. In its home market, it’s the second-largest commercial banking group by assets and customer deposits, with more than 190 branches across the city.

Here’s the deceptively simple question that makes BOCHK worth a deep dive: how did a branch of China’s oldest bank become the nerve center of Renminbi internationalization—and a critical bridge between China and global capital markets?

The answer comes down to a handful of privileges that are rare in any financial system, and almost unheard of all in one place.

First: BOCHK is one of only three commercial banks licensed by the Hong Kong Monetary Authority to issue Hong Kong dollar banknotes. That puts it in a club with HSBC and Standard Chartered—names synonymous with Hong Kong’s colonial-era financial establishment. In other words, BOCHK isn’t just a big bank in Hong Kong. It’s one of the institutions trusted to literally put the city’s money into circulation.

But the second privilege matters even more: BOCHK is Hong Kong’s designated Renminbi clearing bank. Since 2003, it has been the clearing hub for RMB transactions in Hong Kong’s offshore yuan market. If Hong Kong is the world’s most important offshore gateway for the Renminbi, then BOCHK is a big part of the plumbing that makes the whole system work.

And that brings us to the bigger themes in this story: nation-building through financial infrastructure; the unusual tensions—and opportunities—created by “one country, two systems”; and the way geopolitical pressure can sometimes do the opposite of what you’d expect, accelerating integration rather than slowing it down.

II. Origins: From Imperial China to Hong Kong Colony (1905–1949)

BOCHK’s story starts far from the neon and high-rises of Hong Kong, back in the final years of China’s last imperial dynasty. In 1905, the Qing government set up the Da-Qing Bank in Beijing—an attempt to build something like a modern national bank at a time when the state itself was wobbling.

Then the regime changed. When the Republic of China was established in 1912, Chen Jintao—tasked with financial reform under Sun Yat-sen’s government—reorganized the Da-Qing Bank into the Bank of China. He’s widely viewed as the founder, and for good reason: he wasn’t just renaming an institution, he was trying to give a new country the basic financial machinery it needed to function. The Bank of China would help manage foreign exchange, handle overseas payments, and project a kind of financial sovereignty that China had spent the previous century watching slip away.

Hong Kong entered the picture five years later, and this is the moment the BOCHK lineage really begins. In 1917, Tsuyee Pei opened the Bank of China’s branch in Hong Kong. That date matters because it marks the bank’s first durable foothold in what was then the most important window between China and global commerce.

It also carries a poetic through-line: Tsuyee Pei was the father of I.M. Pei, the architect who would later design the Bank of China Tower. Pei’s father had been a manager at the Bank of China, and that family connection was one of the reasons I.M. Pei ultimately took on the project—linking the bank’s earliest Hong Kong presence to its most iconic modern symbol.

The 1917 opening did something else too: it signaled the arrival of state-owned Chinese banking into the colony’s financial ecosystem. Other Chinese banks followed quickly—Yien Yieh Commercial Bank opened a Hong Kong branch in 1918—and a distinct Chinese banking presence began to take shape inside a British-run port city.

And the setting could not have been more loaded. Hong Kong was a gateway for Chinese trade, but it was also unmistakably British in its institutions and power structure. HSBC dominated the landscape, and had been issuing banknotes since the 1860s. Chinese compradors—merchant intermediaries who connected Western capital to Chinese supply—held enormous sway. The Bank of China’s Hong Kong branch arrived in the middle of that world carrying a clear message from Republican China: we’re not outsourcing our financial future.

That ambition wasn’t limited to Hong Kong. In 1929, the Bank of China opened a branch in London—its first outside China. This wasn’t just geographic expansion. It was the bank planting a flag in the financial heart of the British Empire, a statement that China intended to operate in the global system as an institution-builder, not just a borrower or a market.

By the time the Second World War ended, the Bank of China had built a notable regional footprint. In 1946, it reopened branches and agencies across Hong Kong and Southeast Asia—Singapore, Haiphong, Rangoon, Kuala Lumpur, Penang, and Jakarta—restarting cross-border financial links that war had severed.

But the restart came with a countdown. China’s civil war was racing toward its conclusion, and the outcome would split Chinese banking—and redefine what “Bank of China” meant outside the mainland.

III. The Communist Revolution & The Split (1949–1970s)

1949 was a hinge point—not just for China, but for the Bank of China’s identity abroad. Mao Zedong’s Communist forces won the civil war, Chiang Kai-shek’s Nationalists retreated to Taiwan, and suddenly the question for a global bank was stark: which China did it belong to?

In 1950, the answer fractured the institution. Some of Bank of China’s overseas branches—including Hong Kong, Singapore, London, Penang, Kuala Lumpur, Jakarta, Calcutta, Bombay, Chittagong, and Karachi—remained aligned with the mainland bank headquartered in Beijing. Others—such as New York, Tokyo, Havana, and Bangkok—stayed with the Bank of China headquartered in Taipei, which later renamed itself the International Commercial Bank of China in 1971.

For years, that meant something almost surreal: two different institutions, each tracing legitimacy to “Bank of China,” operating separate branch networks around the world. And the map of that split told you a lot about the era. Branches closer to Communist influence in Asia tended to stay with Beijing; branches in more American-aligned territories tended to stick with Taipei.

In that context, Hong Kong became—almost by accident, almost by inevitability—the offshore financial center for Communist China. It was still a British colony, governed by common law, running a freely convertible currency. Yet it hosted the most important overseas operations of mainland Chinese banks.

By the time the People’s Republic of China was established in 1949, Hong Kong already had a deep bench of Chinese financial institutions: 15 branches of state-owned Chinese banks, plus branches of nine mainland-incorporated banks set up as public-private joint ventures.

Beijing moved quickly to bring order to that patchwork. In 1952, the nine public-private banks were grouped into the Joint Office of Joint Public-Private Banks. Then came tightening: in 1954, the Hong Kong branches of three of those banks were closed after their parent banks were shut down by the central government. In 1958, management of the remaining six was transferred to the Hong Kong and Macau Regional Office of the Bank of China.

All of this set up BOCHK’s most unusual role of the Cold War decades: a Communist state’s working window into capitalist markets. While the mainland remained largely cut off from Western financial systems, Hong Kong gave Beijing a channel for foreign exchange, trade finance, and international banking that was hard to replace—and increasingly hard for the world to ignore.

In the 1980s, those legacy institutions began to look less like a loose federation and more like a single machine. After a common IT platform was established, the banks were rebranded under the Bank of China Group—an early, technical consolidation that foreshadowed the much bigger restructuring still ahead.

IV. The Road to Consolidation: Building the Modern BOCHK (1980s–2001)

Deng Xiaoping’s economic reforms, launched in 1978, began turning China from an isolated Communist economy into the workshop of the world. Hong Kong—already thriving as a trading hub and manufacturing center—got pulled into that orbit fast. For the Bank of China’s operations in the city, the message was unmistakable: the old patchwork structure that worked during the Cold War wasn’t going to cut it in a world of booming cross-border trade, modern risk management, and global capital markets.

Then came the political clock. The 1984 Sino-British Joint Declaration set the terms for Hong Kong’s return to China in 1997. It wasn’t just a diplomatic milestone; it was a stress test for the entire financial system. “One country, two systems” sounded elegant in principle. In practice, it raised huge questions for banking: could Hong Kong stay a trusted global financial center under Chinese sovereignty? And could a Chinese-owned bank credibly operate under Hong Kong law and regulation while serving both Beijing’s priorities and international investors’ expectations?

BOC’s answer was to start acting like the kind of institution those investors would recognize.

In 1994, it became the first bank in China to issue bonds into the U.S. market. That same year, BOC’s Hong Kong subsidiary received authority to issue banknotes in the colony—a privilege that was extended to Macau the following year.

That note-issuing franchise wasn’t just another business line. It was a legitimacy stamp. Hong Kong had been running a distinctive banknote system since the 1860s, and the right to print money had long been the domain of the city’s old-guard institutions. Now, for the first time, a Chinese-owned bank would stand beside HSBC and Standard Chartered as an official issuer of Hong Kong dollars. Symbolically, it signaled that the incoming sovereign power wasn’t merely present in Hong Kong—it was being trusted with one of the city’s most core financial functions.

BOC kept expanding the scope of what its Hong Kong platform could do. In 1998, it founded BOC International Holdings in Hong Kong as a dedicated investment banking arm. Supported by BOC’s rapidly expanding overseas network—more than 500 foreign branch offices by the end of the decade—BOC International quickly became China’s leading investment banker, helping Chinese companies interface with global markets on global terms.

The 1997 handover itself ended up being steadier than many feared. Hong Kong’s financial system held together, the currency peg survived the Asian Financial Crisis, and while confidence was shaken, it didn’t collapse. But inside BOC’s Hong Kong presence, there was still a problem: the structure was a legacy museum. Multiple entities, overlapping mandates, and a sprawl that had made sense historically—but made it harder to compete in a market that was getting sharper and more international every year.

So BOC did the thing that turns history into a modern institution: it consolidated.

In January 2001, the People’s Bank of China approved the restructuring plan. Then, on October 1, 2001, Bank of China (Hong Kong) Limited—BOCHK—was formally established, consolidating 12 subsidiaries and associates of the Bank of China in Hong Kong.

Mechanically, the plan merged all mainland-incorporated group members into Po Sang Bank, which was then renamed BOCHK. Nanyang Commercial Bank and Chiyu Banking Corporation—both Hong Kong-incorporated—became subsidiaries of BOCHK. The goal was straightforward: streamline operations, tighten management, and build a single Hong Kong platform strong enough to win in one of the most competitive banking markets in the world.

Because by now, Hong Kong banking wasn’t a sleepy club—it was a knife fight. HSBC still towered over the market with a century of dominance. Global banks from Europe, the U.S., and Japan were entrenched. If BOC wanted its Hong Kong arm to do more than just survive—if it wanted it to become the gateway institution for China’s next phase—it needed one unified, professional, internationally credible bank to carry that mission forward.

V. The Historic IPO: First Chinese Bank to Go International (2002)

Less than a year after the consolidation that created BOCHK, the bank did something even more consequential: it stepped onto the public stage.

In July 2002, BOCHK Holdings listed in Hong Kong—an event that landed like a thunderclap in Chinese finance. It was the first time a mainland China bank pulled off an international stock listing. Up to that point, Chinese bank listings had stayed safely at home in the domestic “A-share” market. Hong Kong was different. Hong Kong meant international disclosure standards, global investors, and a market that priced your credibility every day, in public.

And that was the real leap. Chinese state-owned banks had a reputation—often deserved—for opaque accounting, politically driven lending, and balance sheets weighed down by the legacy of policy credit. By listing in Hong Kong, BOCHK was voluntarily walking into a harsher light: the Hong Kong Stock Exchange’s rules, the expectations of foreign institutions, and the constant scrutiny that comes with trading in one of the world’s most sophisticated financial centers.

On 25 July 2002, BOC Hong Kong (Holdings) began trading on the main board of the Stock Exchange of Hong Kong with stock code “2388”. The offering pulled in an enormous wave of demand. Retail orders alone totaled HK$286 billion (US$36.7 billion), a level of enthusiasm that signaled something bigger than a single deal: Hong Kong investors wanted a stake in China’s financial ascent, and BOCHK was the most legible way to buy into it.

The retail side, in particular, became a phenomenon. Everyday Hongkongers—many of whom already banked with BOCHK—queued up to subscribe. The IPO was oversubscribed, and it wasn’t a modest oversubscription either: the offer ended up around 76 times oversubscribed, one of the most extreme retail responses the Hong Kong market had ever seen.

So why did this work? Part of the answer was structural. BOCHK wasn’t a typical mainland bank trying to reinvent itself overnight—it operated inside Hong Kong’s regulatory framework, with financial reporting audited to international standards and governance that, while far from flawless, was meaningfully more familiar to global investors than what they’d seen from mainland peers. And part of it was timing: by 2002 the “Greater China” investment thesis was already powerful, and BOCHK offered a clean, Hong Kong-listed vehicle tied directly to that story.

Most importantly, the deal didn’t just raise capital. It created a playbook.

Four years later, when the parent Bank of China went public, the path had been cleared. On 1 June 2006, BOC’s listing on the Hong Kong Stock Exchange became the largest IPO since 2000 and the fourth largest IPO ever, raising about US$9.7 billion in the H-share global offering. Days later, on 7 June, the over-allotment option was exercised, bringing the total to about US$11.2 billion.

BOCHK’s 2002 listing proved the concept; BOC’s 2006 listing proved it could scale. And together they helped open the door for the next wave—ICBC, China Construction Bank, Agricultural Bank of China—each following the same basic route into global capital. The transformation of Chinese banks from state instruments into publicly traded institutions didn’t happen overnight, but BOCHK’s IPO showed the world, and Beijing, that it could be done.

VI. The Liu Jinbao Scandal & Corporate Governance Wake-Up (2003–2004)

The IPO glow didn’t last long. Barely a year after BOCHK became a public company, it was pulled into a scandal that rattled confidence and exposed a simple truth: a Hong Kong listing can change your disclosure. It doesn’t automatically change your habits.

At the center was Liu Jinbao, BOCHK’s former CEO and—until May 2003—vice-chairman of Bank of China. His résumé looked like the standard fast track for an elite banker inside a state system. He graduated in 1976 from the University of International Business and Economics in Beijing, joined Bank of China immediately, and was sent to London the next year. From there he rose through the Shanghai offices from 1981 to 1997, becoming Shanghai’s general manager in 1994, and then moved to the crown-jewel assignment: running the Hong Kong operations in 1997.

It was a textbook trajectory: party credentials, overseas experience, senior provincial leadership, then Hong Kong. But the story underneath it was messier.

By 2000, Liu was under investigation by Chinese and U.S. authorities for improper lending tied to his time in Shanghai, alongside Shanghai politician Chau Ching-ngai. In May 2003, Liu was abruptly transferred back to Beijing to take the vice-chairman role at Bank of China.

On paper, it read like a promotion. In practice, it looked like something else: move him out of the spotlight, bring him closer to the center, and let the investigation run.

The allegations didn’t stop at lending. Liu, along with three other senior managers, was also alleged to have made “unauthorised distribution for personal purposes” of funds belonging to Bank of China before BOCHK was established. The Standard speculated the amount involved was HK$30 million.

Then the review widened to the Hong Kong side of the house, and the episode that became the scandal’s focal point: a bridge loan to Chau Ching-ngai. A special committee appointed by BOC (Hong Kong) Holdings, working in consultation with the Hong Kong Monetary Authority, found that the granting of a HK$1.77 billion bridge loan involved risks that were identified upfront—but weren’t adequately addressed. Even more damning, the loan went ahead despite serious reservations raised by the Risk Management Department.

This is the kind of detail that makes investors sit up straight. Not because big loans go bad—banks can survive that—but because the process failed in a way that suggested the wrong people had the real veto power.

The situation deteriorated fast. Chau’s business empire collapsed, and he was arrested on the mainland. Meanwhile, the scrutiny spread. BOCHK said that Mr Zhu and Mr Ding were being questioned in relation to the alleged “unauthorised distribution for personal purposes” of certain funds belonging to the controlling shareholder of BOCHK’s former constituent banks, before the July 2002 IPO.

For international shareholders, this was the nightmare scenario: you bought into a newly listed bank that marketed itself as modern and Hong Kong-regulated—and then discovered management behavior that felt uncomfortably like the old model, where political relationships and internal hierarchies could override risk discipline.

BOCHK’s response mattered. The bank reorganised, tightened internal controls, and reshuffled leadership—making several executive appointments through a global replacement effort. Risk management and governance were overhauled, and the HKMA’s involvement became more intensive.

The bigger takeaway is that this wasn’t just a tabloid scandal. It was a forced lesson in what it takes to be a real public company—especially a state-backed one. Listing rules can set standards, but credibility only comes when an institution proves, under pressure, that it can follow them. BOCHK came out of the episode bruised, but more disciplined—and, over time, more credible.

VII. Inflection Point #1: Becoming the RMB Clearing Bank (2003–Present)

While the Liu Jinbao scandal was dominating headlines, something far more consequential was taking shape in the background. In late 2003, China made one of its first, carefully controlled moves toward internationalizing the renminbi—and BOCHK was picked to make it real.

On 18 November 2003, Hong Kong’s chief executive announced that the People’s Bank of China had agreed to provide clearing arrangements. It was a first: the renminbi—convertible on the current account but not on the capital account—would be allowed to clear outside mainland China. The initial scope was practical and consumer-friendly: deposit-taking, currency exchange, remittances, and RMB card services.

Hong Kong banks were invited to apply to become the designated clearing bank for this new RMB business. The People’s Bank of China ultimately selected BOCHK, initially for a three-year term.

The significance is hard to overstate. Before 2003, the renminbi wasn’t a currency you could meaningfully “use” offshore. Cross-border RMB activity was tightly restricted, and the currency’s lack of capital account convertibility kept it largely boxed inside the mainland financial system.

The clearing arrangement in Hong Kong cracked that box open—just a little at first, but enough to change the trajectory. For the first time, RMB could begin to build an offshore life: Hong Kong residents could hold RMB deposits; over time, trade could be settled in RMB; and eventually an entire product ecosystem emerged, including offshore yuan bonds that would later be nicknamed “dim sum bonds.”

As the sole clearing bank for RMB business in Hong Kong, BOCHK worked closely with the People’s Bank of China and the Hong Kong Monetary Authority to implement and continuously improve how RMB clearing actually operated. The pitch was simple: make Hong Kong the most reliable offshore home for the currency, and make BOCHK the bank that sits at the center of it.

One of the early building blocks was infrastructure. Hong Kong launched the offshore RMB Settlement System—the first of its kind anywhere—and the clearing bank introduced personal RMB cheque clearing. These sound like operational details, but that’s the point: turning a currency into something international isn’t primarily a speech or a policy memo. It’s payment rails, settlement rules, and daily reliability.

And the clearing bank role came with real economics. BOCHK received a 0.125% cut of RMB deposits in Hong Kong that were repatriated back to mainland China. It’s a small percentage, but it’s applied to a massive pool of activity—making it a meaningful and unusually predictable stream tied directly to the growth of offshore RMB.

The mandate then expanded in capability and reach. BOCHK extended the operating hours of Hong Kong’s RMB Real Time Gross Settlement system to overlap with Europe and part of the United States—running from 8:30 am to 11:30 pm, Monday through Friday, Hong Kong time. That mattered because it let participating banks in the West settle RMB transactions in real time through Hong Kong, reducing settlement risk and making RMB business easier to run at global-market speed.

By 2024, Hong Kong’s role in offshore RMB was dominant. More than 70% of global offshore RMB payments were being settled there, supported by the world’s largest offshore RMB funding pool, foreign exchange market, and over-the-counter interest rate derivatives market.

And BOCHK was processing the flow. In 2024, Bank of China handled 1,313.83 trillion yuan in cross-border RMB clearing business, up 40% year-on-year. Its RMB settlement volume in Hong Kong also rose sharply, increasing by 5.3 times versus the prior year.

This is what a true infrastructure moat looks like. Every bank that wants to offer RMB services in Hong Kong needs access to BOCHK’s clearing systems. Every corporate that wants to settle meaningful trade in yuan needs a path into the same rails. And every offshore RMB product—deposits, loans, bond issuance, derivatives—benefits from the liquidity and confidence that come from having one trusted clearing center.

For long-term investors, this is the structural advantage that matters most. It’s hard to replicate, it’s embedded in policy and market plumbing, and it becomes more valuable the more the renminbi is used outside the mainland.

VIII. Inflection Point #2: The 2019 Protests & National Security Law (2019–2020)

In the summer of 2019, Hong Kong hit its most serious bout of civil unrest since the 1967 leftist riots. What started as protests against a proposed extradition bill quickly escalated into something much bigger: a mass movement challenging Beijing’s authority and Hong Kong’s governance model.

The trigger was the Hong Kong government’s bill to amend the Fugitive Offenders Ordinance. In plain terms, it would have allowed criminal suspects to be extradited, case by case, to jurisdictions where Hong Kong didn’t already have extradition treaties—including mainland China. The reaction was immediate and enormous: it became the largest sustained series of demonstrations in Hong Kong’s history, stretching from 2019 into 2020.

Uncertainty wasn’t just a feeling; it showed up in the data and in daily life. Hong Kong’s monthly economic and political uncertainty values jumped from 67 in April 2019 to an average of 262 from May through November, the period marked by the most intense protests. And then the disruption became physical. Key infrastructure was periodically knocked offline—airport operations were canceled, railway stations in the heart of the financial district shut down, and many banks and investment firms scaled back operations for security reasons.

That kind of instability bleeds into everything. Retail sales fell. Consumer spending pulled back. Restaurants saw customers cancel bookings. Shops and bank branches closed their doors in affected areas. Supply chains got tangled. The damage spread from the street level to the macro level, and by the second half of 2019 Hong Kong slipped into recession; annualized GDP contracted 2.9%, the largest drop in a decade.

Beijing’s response arrived in June 2020 with the National Security Law: sweeping legislation criminalizing secession, subversion, terrorism, and collusion with foreign forces. In the period that followed, authorities moved to eliminate nearly all political opposition, muzzle civil society, and shutter independent media.

The West responded quickly and harshly. The United States revoked Hong Kong’s special trade status. Congress passed the Hong Kong Autonomy Act. Sanctions were imposed on Hong Kong officials, including the Chief Executive.

For BOCHK, this created a strategic paradox. On one hand, the city’s political transformation—and the sanctions environment around it—added real risk that global investors and counterparties couldn’t ignore. On the other hand, it accelerated exactly the kind of mainland integration BOCHK was built to enable.

In 2021, the bank launched a five-year strategic plan centered on cross-border connectivity, wealth management, and digital services—explicitly designed to capitalize on Greater Bay Area synergies. And despite the environment, operating income kept growing.

The geopolitical lesson is more counterintuitive than the headlines suggested. The conventional expectation was that worsening US–China relations and Hong Kong’s political upheaval would weaken the city’s role as a financial hub. Instead, BOCHK leaned harder into being the bridge between China and international capital—because when the direct routes narrow, the remaining bridges become more valuable.

IX. Inflection Point #3: The Greater Bay Area Strategy (2019–Present)

While political turbulence dominated the headlines, a more constructive story was unfolding just across the border: the slow, deliberate knitting together of Hong Kong with the manufacturing and tech powerhouse of the Pearl River Delta. The Greater Bay Area initiative, given official shape in an Outline Development Plan in February 2019, was Beijing’s blueprint for turning South China into a single, integrated mega-region.

The Greater Bay Area, or GBA, is an 11-city cluster: Hong Kong and Macau, plus nine cities in Guangdong province—Guangzhou, Shenzhen, Zhuhai, Foshan, Huizhou, Dongguan, Zhongshan, Jiangmen, and Zhaoqing. On a map it looks straightforward. In practice, it’s a complex project: different legal systems, different currencies, different regulators—and yet, a shared economic gravity that keeps pulling the region closer together.

By 2023, the GBA’s GDP had exceeded 1.4 billion yuan. It produced about 11% of China’s GDP using less than 0.6% of the country’s land and about 6% of its population—an outsized engine of growth. And the ambition is explicit: the GBA is meant to become an international, first-class bay area and a world-class city cluster.

To make that work, four core cities were assigned distinct roles: Hong Kong, Macau, Guangzhou, and Shenzhen. Hong Kong’s job, in particular, was to deepen its role as an international financial center while building strength in technology and innovation—essentially, to become the region’s capital markets and wealth hub.

For BOCHK, this was less a pivot than an expansion of what it already did best: cross-border finance. The bank’s growth strategy centered on deepening its presence in the GBA while also expanding its footprint in Southeast Asia. And critically, it aimed to do that by leaning into the access points that actually matter in modern Chinese finance—mutual market access programs like Stock Connect, Bond Connect, Cross-boundary Wealth Management Connect, and Swap Connect.

BOCHK’s positioning here is unusually strong. It has deep roots in Hong Kong, a close connection with its parent Bank of China, and a long track record of serving both retail and wholesale clients on cross-border needs. In Hong Kong, it holds the second-largest market share of deposits after HSBC. That funding advantage—sticky deposits that don’t flee at the first sign of volatility—pairs with tight cost control, producing an industry-leading cost/income ratio of around 30%.

Then there’s the flagship consumer-facing bridge: Cross-boundary Wealth Management Connect, launched in 2021. For residents in Hong Kong, Macau, and the nine mainland GBA cities, it opened the door to buying wealth management products across the border within the program rules. BOCHK’s argument is simple: if wealth is going to move more fluidly inside the GBA, the banks with real distribution on both sides—and the infrastructure to move money cleanly and compliantly—are going to capture that flow.

You can see that dynamic in the payment layer too. By the end of 2024, transaction amounts from customers using BoC Pay for spending in mainland China had increased by 111.8% year-on-year—evidence that cross-border usage wasn’t just a policy aspiration, it was turning into everyday behavior.

And the GBA strategy doesn’t stop at the Pearl River Delta. BOCHK’s Southeast Asian entities also grew: deposits and advances to customers rose by 16.5% and 9.9% respectively from the end of 2023, excluding foreign exchange impacts—another sign the bank is trying to be a regional connector, not only a Hong Kong incumbent.

The broader takeaway is what the GBA thesis does to BOCHK’s identity. It takes a bank that could be seen as a Hong Kong-focused retail franchise and reframes it as a gateway institution for a mega-region. The advantage isn’t just having branches. It’s the combination of regulatory access, RMB clearing infrastructure, parent-company connectivity, and institutional relationships—layers of advantage that are hard to copy quickly, and even harder to copy all at once.

X. Digital Transformation & Fintech Response (2020–Present)

By the time BOCHK was leaning into the Greater Bay Area, a different kind of pressure was building at home. Hong Kong’s banking market—already one of the most competitive in the world—was about to get a new class of rivals. In 2019, the Hong Kong Monetary Authority licensed eight virtual banks: digital-only challengers designed to operate without branches, without legacy systems, and without the old assumption that a bank needed a physical footprint to feel “real.”

For incumbents like BOCHK, this wasn’t a side quest. It was a forcing function. If customers were going to manage their finances the way they order food and book flights—through a phone—then BOCHK needed to be great at mobile banking, not merely present in it.

COVID poured fuel on that shift. As day-to-day life moved online, BOCHK’s digital channels stopped being a convenience and started becoming the default. By September of that period, personal accounts opened via mobile banking made up nearly 30% of all newly opened personal accounts. From January to October, the number of FPS transactions conducted via mobile banking almost tripled, while investment transactions nearly tripled and life insurance enrolments almost doubled. The direction of travel was unmistakable: customers weren’t just checking balances on their phones—they were opening accounts, investing, and buying insurance there too.

BOCHK responded by building experiences meant to feel native to a smartphone world, not retrofitted onto it. “BoC Live” was one of the more distinctive examples: a mobile banking function with live broadcast capability, where investment experts shared perspectives on stock and foreign exchange markets and discussed investment strategies. It’s a small detail, but it signals something important. BOCHK wasn’t just digitizing transactions; it was trying to digitize trust and advice—two things traditional banks have historically delivered in person.

At the infrastructure level, Hong Kong itself kept pushing the market toward data-driven finance. In January 2024, the HKMA launched the Interbank Account Data Sharing (IADS) program, setting rules and standards for customer-consented data sharing between banks. BOCHK’s stated direction was to keep driving digital transformation and deepen the use of fintech across products and services, aligning with where regulators—and customer expectations—were heading.

That showed up in the steady drumbeat of product work. By the end of 2023, BOCHK had introduced 200 functional enhancements to its mobile app as part of a mobile-first strategy. BoC Pay, its payments app, grew 20.8% year-on-year, while overall transaction volumes increased by 10.2%. The theme here isn’t any single feature. It’s cadence: in a digital market, you don’t “finish” transformation—you ship continuously.

Open-banking became another pillar. BOCHK rolled out more than 100 APIs, with daily requests peaking at 310,000. And it pushed beyond banking into life moments where financing decisions actually happen. Its home purchase ecosystem app passed 170,000 downloads and helped drive a 28% year-on-year rise in loan applications. That’s a classic distribution play: embed the bank where customers make big decisions, then make the financing feel frictionless.

But BOCHK’s digital story isn’t only about competing with virtual banks. It’s also about staying central to the future plumbing of cross-border money—because that’s the franchise. The bank promoted cross-border applications of e-CNY, becoming the first bank to provide e-CNY services via local payment tools. It launched e-CNY acquiring services with well-known local retailers, targeting real retail usage rather than pilot-program theater.

It also moved into the next wave of cross-border settlement experimentation. BOCHK became the first commercial bank in Hong Kong to connect with the mBridge platform, supporting end-to-end remittance transactions through automated processing across the entire procedure. mBridge—a cross-border payment project involving the Chinese mainland, Hong Kong, Thailand, and the United Arab Emirates—has been testing e-CNY in international trade. Bank of China has participated since 2022, with its head office in Beijing, all domestic branches, BOCHK, its Thailand subsidiary, and its Abu Dhabi branch all involved. Since the project began, BOC led on measures like transaction volume and value, and provided liquidity support for other participating banks in the mBridge system.

Alongside digital finance, BOCHK also elevated sustainability as a core strategic priority. It ramped up green finance, with green and sustainability-related loans increasing by nearly 30% by the end of 2024 compared with the previous year-end. It completed carbon neutrality certification for Bank of China Tower and the Bank of China Building, becoming the first bank in Hong Kong to receive such certificates for self-owned properties. For three consecutive years, it received the “Asia-Pacific Climate Leaders” award from the Financial Times, while its MSCI ESG rating remained at “AA”.

Taken together, this isn’t just BOCHK defending itself against disruptors. It’s the bank repositioning for where its edge can compound next: a world where cash keeps giving way to digital payments, trade finance becomes increasingly automated, and customers expect a smartphone-first experience by default. BOCHK’s bet is that the bank that owns the rails of cross-border finance also needs to own the interface—and the data—that runs on top of them.

XI. The Business Today: Structure, Operations & Market Position

To understand BOCHK today, you have to look at it in two ways at once: as a modern Hong Kong retail and commercial bank you can walk into on any street corner—and as a strategically important extension of China’s state-backed financial system.

Operationally, BOCHK runs through four core segments: Personal Banking, Corporate Banking, Treasury, and Insurance. Personal Banking is the everyday franchise—deposits, loans, mortgages, credit cards, and wealth management for individuals. Corporate Banking serves companies with lending, trade finance, cash management, and advisory services. Treasury is where the bank manages capital, liquidity, and market risk. And Insurance rounds out the ecosystem with life and general insurance products offered through affiliated entities.

The physical footprint is still a big part of the story. BOCHK has the most extensive branch network and service platforms among local banks in Hong Kong, with more than 190 branches, around 280 automated banking centres, and over 1,100 self-service machines—supported by internet and mobile banking that now do a growing share of the daily work. The result is a bank that can serve traditional, high-touch customers while also operating at the speed of digital finance.

Then there are the subsidiaries—legacy institutions with their own identities that expand BOCHK’s reach.

Nanyang Commercial Bank, founded in Hong Kong in 1950, is a wholly owned subsidiary with 42 branches. It has long focused on corporate clients, particularly small and medium-sized trading and manufacturing businesses—the kind of customers that quietly anchor Hong Kong’s real economy.

Chiyu Banking Corporation is even more community-specific. Founded in 1947 by Tan Kah Kee, an overseas Chinese businessman, it has 23 branches in Hong Kong and is known for serving Hong Kong residents of Fujian descent. Chiyu was created as a sustainable business with profits devoted to education in Xiamen and the rest of Fujian province in China—an origin story that still shapes how the brand is perceived.

Pull back one more level, and you get to the ownership chain—which ultimately runs to Beijing. As of the end of 2019, 65.65% of BOCHK Holdings was held by Bank of China Group, which in turn was 69.265% owned by Central Huijin Investment, an investment holding company wholly owned by the Government of the People’s Republic of China.

Financially, the recent picture has been strong. In 2024, BOC Hong Kong’s revenue rose 12% to HK$66.2 billion, while net income increased 17% to HK$38.2 billion, lifting profit margin to 58%. Earnings per share also rose, to HK$3.62 from HK$3.10 in 2023.

Momentum carried into 2025. For the interim period ending June 2025, BOCHK reported net operating income before impairment allowances of HK$40.022 billion, up 13.3% year-on-year. Net profit reached HK$22.152 billion, up 10.5%, with earnings per share of HK$2.0952.

Management framed that performance as the payoff from tighter fundamentals—stronger risk control, sturdier banking infrastructure, and broader earnings sources—supporting what it described as “high-quality development.” And for the fifth consecutive year, the bank was recognised as “The Strongest Bank in Hong Kong” by The Asian Banker.

Zoom out, and BOCHK’s market position rests on a set of advantages that are hard to imitate: one of the largest deposit bases in Hong Kong, the city’s most extensive branch footprint, note-issuing privileges, and—most importantly—the RMB clearing role that keeps it embedded in the offshore renminbi system. Layer on top the deep connectivity to mainland China through its parent, and you get a bank whose edge is structural, not cyclical: it’s built into the plumbing, the licenses, and the political economy of how money moves between China and the world.

XII. Playbook: Strategic & Business Lessons

The Infrastructure Moat

BOCHK’s most durable advantage isn’t a product. It’s position. The bank sits inside Hong Kong’s financial plumbing: the RMB clearing role, the right to issue Hong Kong dollar banknotes, and even its role as a co-founder of the JETCO ATM network. These aren’t features you out-innovate with a nicer app or undercut with cheaper pricing. They’re franchise rights embedded in how the system itself works.

For investors, this is the cleanest kind of moat—because it compounds as the system grows. The only real question is whether the infrastructure gets bypassed or made obsolete. In BOCHK’s case, RMB clearing in Hong Kong looks structurally sticky. China has continued to prefer routing offshore yuan activity through regulated Hong Kong channels. Yes, Beijing could appoint a different clearing bank. But in practice, switching would create friction, introduce operational risk, and raise systemic questions—moves you don’t make lightly unless something has gone badly wrong.

The "Two Systems" Arbitrage

BOCHK is built to exploit a one-of-one configuration: it operates under Hong Kong law, with Hong Kong regulation and market credibility, while still benefiting from mainland connectivity through its parent. That’s an arbitrage neither side can easily copy.

A foreign bank in Hong Kong can be world-class—but it doesn’t have BOCHK’s internal access to China’s banking networks and priorities, which makes truly seamless cross-border service harder. A mainland bank can have the relationships and the mandate—but it doesn’t automatically come with Hong Kong’s common-law framework, freely convertible currency environment, and the international comfort that those things still create.

That positioning becomes more valuable when geopolitics tighten the pipes. When American and other Western institutions face rising pressure around Chinese capital flows, and when mainland banks have to think harder about sanctions risk and dollar access, a major bank operating from Hong Kong’s jurisdiction can offer a measure of flexibility—without fully leaving the orbit of the mainland system it’s designed to connect to.

Crisis as Catalyst

The 2019–2020 shock showed how disruption can accelerate strategy instead of killing it. The standard forecast was simple: protests, instability, and then sanctions pressure would weaken Hong Kong’s financial role and drag banks with it. BOCHK’s reality was more complicated. It used the period to lean into mainland integration, push forward digital initiatives, and set itself up to capture Greater Bay Area connectivity.

The lesson isn’t that political risk is irrelevant—it’s the opposite. Political risk can reshape markets fast. The point is that institutions with the right structural position can sometimes convert that reshaping into advantage, if they’re willing to lean into the direction the system is moving rather than waiting for the old world to return.

Patient Capital Allocation

State ownership comes with real governance hazards—the Liu Jinbao episode made that painfully clear. But it also enables something private markets rarely sustain: patience.

RMB clearing infrastructure wasn’t a one-year project. Neither is building distribution and service capability across the GBA, or participating in long-horizon experiments like mBridge. Those bets make more sense when you can invest for strategic relevance over decades, not only optimize for the next quarter’s earnings call.

The Branch Network Paradox

In a digital-first era, a giant branch network can look like dead weight. For BOCHK, it has often functioned as an asset—especially where money gets complicated.

High-net-worth clients navigating cross-border wealth planning, mainland entrepreneurs who still want relationship banking, and older depositors who prefer face-to-face service all pull the bank back toward physical presence. Branches are expensive, but trust is valuable—and trust is still often built in person.

The forward-looking question isn’t whether branches disappear. It’s whether BOCHK can keep the best part of the network—advice, relationships, complex problem-solving—while migrating routine transactions to digital channels. That hybrid model, more than a pure “digital bank” story, appears to be the path BOCHK is choosing.

Bull Case vs. Bear Case Analysis

Bull Case

RMB Internationalization Tailwinds: If the renminbi continues its slow march outward, BOCHK’s clearing-bank role becomes more than an advantage—it becomes a tollbooth on a growing highway. Offshore RMB markets are still small relative to the dollar system, which leaves room for a long runway if usage keeps expanding.

GBA Integration: The Greater Bay Area isn’t just a policy slogan; it’s a blueprint for turning cross-border movement of people, capital, and commerce into daily routine. That’s exactly the environment where BOCHK’s mix of physical presence, regulatory familiarity, and clearing infrastructure can translate into durable share.

Operational Efficiency: BOCHK’s cost discipline shows up in an industry-leading cost/income ratio around 30%. If revenue keeps compounding, the bank doesn’t need heroic execution to generate operating leverage—its structure is already set up for it.

Dividend Yield: The bank has sustained steady dividend payouts, which matters in banking because it signals confidence in earnings quality and balance sheet resilience. For investors willing to stomach cycles, the dividend turns “waiting” into part of the return.

Digital Competitiveness: The virtual-bank era didn’t hollow out BOCHK the way some feared. Instead, it’s built out digital channels while keeping the parts of banking that still benefit from human relationships—wealth, mortgages, complex cross-border needs—inside the franchise.

Bear Case

Hong Kong Political Risk: Hong Kong’s governance model has changed materially since 2020. If more multinational firms and capital flows choose to diversify away from the city, the entire financial sector—including BOCHK—could face a smaller addressable market.

US-China Decoupling: The biggest non-financial risk is geopolitical. Escalating tensions could translate into restrictions that affect BOCHK’s ability to transact in dollars, work with certain counterparties, or serve international clients. Even without direct sanctions, the secondary-sanctions risk is a real overhang.

Chinese Economic Slowdown: China’s property stress, demographic challenges, and geopolitical frictions could reduce growth and confidence. If that happens, cross-border activity and credit demand would likely cool—two areas that matter to BOCHK’s “gateway” narrative.

State Ownership Governance: The bank has improved its controls since earlier governance scandals, but state ownership never disappears as a factor. Policy objectives can conflict with minority shareholder value, and capital allocation may sometimes optimize for national priorities rather than pure return on equity.

Interest Rate Sensitivity: Like most deposit-funded banks, BOCHK lives and dies by net interest margin. A prolonged low-rate environment can compress spreads and make even a well-run franchise feel sluggish.

Porter's Five Forces Analysis

Competitive Rivalry (Medium): HSBC still defines the top of the Hong Kong market, but BOCHK’s number-two position is deeply entrenched. Competition tends to be disciplined rather than ruinous, with banks differentiating by customer segment and cross-border capability more than by price wars.

Threat of New Entrants (Low): Banking is permissioned, not frictionless. Licenses are scarce, branch networks take decades, and the RMB clearing function can’t simply be copied. Virtual banks can nibble at specific products, but they don’t replicate the core franchise.

Supplier Power (Low): The main inputs are talent and technology. Both matter, but neither is concentrated enough to dictate terms to a bank of BOCHK’s scale.

Buyer Power (Medium): Large corporates can negotiate hard, especially on pricing and service bundles. Retail customers have less leverage, and for clients tied into RMB clearing and cross-border rails, switching is rarely painless.

Threat of Substitutes (Low to Medium): Alipay and WeChat Pay compete for payment flows and customer attention, but they don’t replace core banking functions like balance-sheet credit, corporate treasury services, or regulated cross-border settlement. Crypto remains peripheral for mainstream banking needs.

Hamilton Helmer's 7 Powers Analysis

Counter-Positioning: BOCHK can lean into China-linked business that some Western banks may avoid as compliance, reputational, or geopolitical risk rises. That creates a structural opening—serving demand others can’t, or won’t, fully meet.

Scale Economies: A large branch footprint and broad customer base lower unit costs in distribution and servicing, especially in a market where trust and convenience still matter.

Network Effects: RMB clearing behaves like a network. The more participants rely on the system, the more valuable and “default” it becomes, reinforcing BOCHK’s centrality.

Switching Costs: Corporate treasury setups, RMB clearing dependencies, and cross-border integrations create sticky relationships. Banks can be replaced, but the operational cost of replacing them is often high.

Branding: The Bank of China name carries weight—particularly among mainland customers and overseas Chinese communities—translating into trust that is difficult to buy quickly through marketing alone.

Cornered Resource: The RMB clearing bank designation is the clearest example of a cornered resource: a government-granted position that competitors cannot bid away through better execution.

Process Power: BOCHK’s accumulated know-how in RMB operations and cross-border connectivity is its quieter advantage. These are learned systems—risk controls, settlement routines, institutional relationships—that take years to build and are hard to replicate under pressure.

Key Metrics to Watch

If you want to keep score on BOCHK without getting lost in the weeds, there are three indicators that usually tell you first whether the story is getting stronger—or starting to crack.

1. RMB Clearing Volumes and Revenue Share

RMB clearing is BOCHK’s signature franchise, and it’s the closest thing the bank has to a structural tollbooth. The simplest check is whether clearing volumes keep climbing over time—and, just as importantly, whether the clearing business continues to show up as a meaningful contributor to revenue. If volumes stay stable or grow through periods of market turbulence, that’s usually a sign the franchise is durable, not just cyclical.

2. Net Interest Margin (NIM) Trend

BOCHK is still, at its core, a deposit-funded bank. That means net interest margin is the profit engine. Watching NIM over time—especially against the backdrop of Hong Kong rate moves and competitive pressure—tells you whether BOCHK is holding pricing power or getting squeezed. A sustained drop doesn’t automatically mean something is “wrong,” but it does demand an explanation: funding costs rising too fast, loan yields compressing, or competition biting harder than expected.

3. Greater Bay Area Revenue Mix

The biggest forward-looking bet in BOCHK’s strategy is that Greater Bay Area integration turns into routine, repeatable business—not just policy headlines. So the question becomes: how much of BOCHK’s revenue is actually being pulled by cross-border GBA activity? Signals here include the bank’s participation in programs like Southbound Bond Connect, momentum in Wealth Management Connect (including AUM trends), and growth tied to serving customers moving between Hong Kong and the mainland. If the GBA contribution keeps rising, the strategy is working. If it stays flat, then the “gateway” narrative starts to look more like branding than reality.

Regulatory and Legal Considerations

For all of BOCHK’s structural advantages, investors still have to live under the shadow of a few real, non-theoretical overhangs.

US sanctions risk is the biggest one. BOCHK has not been directly sanctioned, but the direction of travel in US–China financial restrictions matters. Any shift in US policy—especially an expansion into secondary sanctions that touches Hong Kong banks—would be a material risk, not a headline risk. It could affect counterparties, access, and the cost of doing business in dollars.

Then there’s the evolution of Hong Kong’s own regulatory environment. The Hong Kong Monetary Authority has a reputation for robust supervision. But post-2020, the question investors quietly ask is whether Hong Kong regulation remains meaningfully insulated over time, or whether it drifts toward mainland-style priorities. Any signs of directed lending, or political considerations shaping supervisory decisions, would change how markets price the franchise.

Anti-money laundering compliance is another constant pressure point. Hong Kong sits at the crossroads of global capital flows, and that makes its banks targets for intense AML scrutiny. The risk here isn’t abstract: failures can trigger large penalties and, more damagingly, reputational hits that make international relationships harder to maintain.

Finally, there’s the reality of state ownership. BOCHK’s Hong Kong listing brings extensive disclosure and a degree of transparency, but visibility into decision-making at the Bank of China Group level—and into policy directives that may shape capital allocation—is inherently limited. For minority shareholders, that means related-party transactions and upstream influence deserve ongoing scrutiny.

The Bank of China Tower still stands at 1 Garden Road, its triangular facets catching and scattering the light as the harbor and skyline keep remaking themselves. I.M. Pei designed it to resemble bamboo shoots—a symbol of resilience and renewal in Chinese culture. It’s hard not to see the metaphor.

BOCHK has navigated colonial rule, the handover, corporate governance shocks, financial crises, street-level upheaval, and an era of geopolitical confrontation. And through it all, it has kept its place in the system: not just as a big Hong Kong bank, but as a piece of infrastructure in China’s outward financial linkages.

What happens next depends on forces larger than any management team. Does Hong Kong continue to thrive as a global financial hub, or does it slowly narrow into a more regional role? Does RMB internationalization keep inching forward, or stall—or reverse? And in a world where financial channels are increasingly shaped by politics, does being the bridge become an advantage, or a vulnerability?

For long-term investors, BOCHK offers something that’s getting harder to find: exposure to structural trends—China’s financial integration, offshore RMB growth, Greater Bay Area connectivity—through an institution that still operates inside Hong Kong’s regulatory framework. The complexity of state ownership is real. The political risks aren’t cosmetic. The geopolitical uncertainty is substantial. But if you’re willing to underwrite those realities, BOCHK is one of the clearest windows into one of the most consequential financial transformations of our era.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music