Shenzhou International: The Silent Giant Behind Your Nike and Uniqlo

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

There’s a good chance you’re wearing something made by a company you’ve never heard of.

Imagine it’s early morning in Ningbo, in China’s Yangtze River Delta. A factory complex is already fully awake. Inside, automated knitting machines run with metronomic consistency, turning yarn into technical fabric at industrial scale. A few months from now, that fabric will show up as a Nike swoosh, Uniqlo’s familiar “U,” or Adidas’ three stripes—on shirts, leggings, hoodies, and all the other “everyday performance” staples that have become modern uniforms.

The name on the building isn’t Nike or Uniqlo.

It’s Shenzhou International.

Shenzhou is a behind-the-scenes giant: more than 97,000 employees, over 250,000 metric tons of fabric a year, and roughly 550 million garments flowing through its system annually. The company works closely with Nike, Uniqlo, Adidas, Puma, lululemon, and other global brands. So when you pull on a workout top, or throw on one of Uniqlo’s AIRism pieces, there’s a very real chance Shenzhou’s factories—and Shenzhou’s processes—are the reason it fits, performs, and holds up the way you expect.

What makes this story even more interesting is that Shenzhou didn’t become a juggernaut by building a consumer brand. It became one by becoming indispensable.

It went public in Hong Kong at HK$2.60 a share. Since then, the stock’s rise has delivered roughly a 28-fold return for IPO investors—an outcome that’s hard to achieve in any industry, let alone one as brutally competitive as apparel manufacturing.

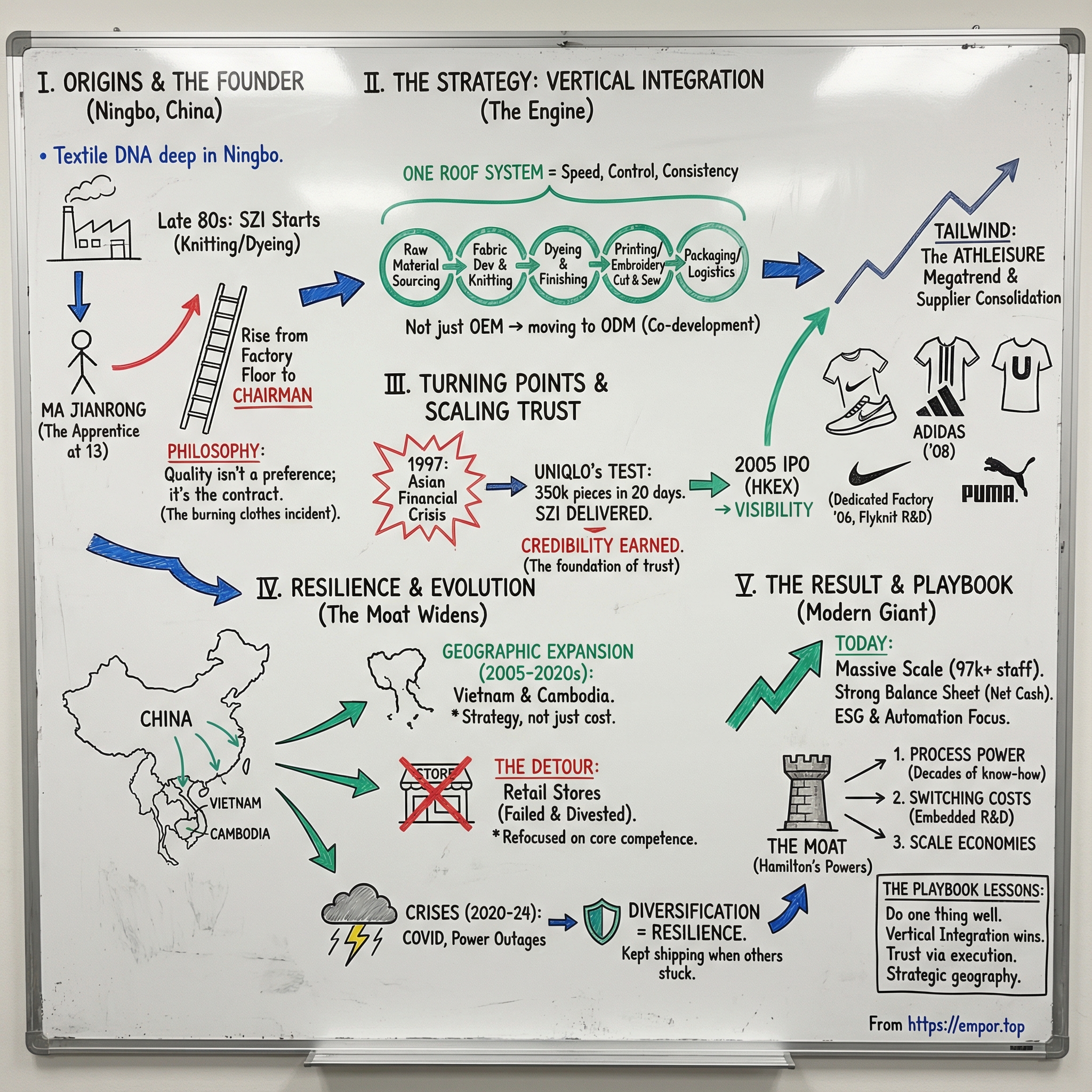

And at the center of it all is Ma Jianrong, Shenzhou’s chairman: a man who started as a factory worker and rose, step by step, into one of the most consequential figures in global manufacturing. This isn’t a Silicon Valley story about software eating the world. It’s a story about making the world—at scale, with precision, and with a level of operational excellence so high that the biggest brands on Earth bet their best products on it.

The question we’re chasing is simple to ask and surprisingly hard to pull off: how did a factory worker from Ningbo build the world’s largest vertically integrated knitwear manufacturer—and what does vertical integration even mean in an industry famous for outsourcing everything?

Here’s the roadmap. We’ll follow a multi-decade founder journey; a company-wide obsession with focus in an era when everyone else chased diversification; the pivotal trust Shenzhou earned by serving demanding customers; why brands hand Shenzhou their most proprietary fabric and production playbooks; and how the company managed the “decade of out-migration” as manufacturing shifted into Southeast Asia.

This is, at its core, the ultimate manufacturing story—what happens when discipline and execution collide with one of the defining consumer shifts of the last generation: the rise of athleisure.

II. Origins: Ningbo, Textile Culture & China's Opening

You can’t tell Shenzhou International’s story without starting where it started: Ningbo, a coastal city in Zhejiang Province that has been making clothes and textiles for so long it’s practically part of the city’s DNA.

Ningbo isn’t just “another manufacturing hub.” In the history of modern Chinese garment-making, it’s famous for the so-called “hongbang dressmakers,” and it’s often described as a cradle of China’s modern apparel industry. Many early milestones of that industry—tailoring traditions, suit shops, even early garment education—trace back to Ningbo people. Long before Shenzhou existed, the region was already wired for this work.

Ma Jianrong was born in 1965 in Shaoxing, also in Zhejiang. China at that moment was a very different place. The Cultural Revolution was about to begin, and “private enterprise” wasn’t a dream—it was a risk. But Zhejiang also had a reputation, even then, for being unusually entrepreneurial. When China finally loosened up, the people in places like Zhejiang were ready.

Ningbo’s industrial base ran deep. Cotton-spinning mills, flour mills, textile plants, and tobacco factories existed there before World War II. After 1949, industrialization continued, and textiles expanded into new knitting factories, dyeing plants, and yarn-spinning mills. By the time China began reopening to the world, Ningbo already had generations of textile knowledge baked into its workforce.

Then came 1978. Deng Xiaoping’s reform and opening policies changed the trajectory of the entire country—and coastal cities like Ningbo felt it first. Ningbo sits about 220 kilometers south of Shanghai, and it had been trading with the outside world in some form since as far back as the 7th century. As China pivoted toward exports, Ningbo’s port and its manufacturing base turned the city into an engine for global production, shipping everything from electrical goods to food to, of course, textiles.

It was in that moment—when China was shifting from a command economy toward what would become the world’s factory—that Shenzhou took root. In the late 1980s, the Ningbo city government set up a new textile factory as part of its industrial development push. That factory would become Shenzhou. The business started with straightforward work: knitting and dyeing, producing basic fabrics and taking the orders it could get. The operation was modest, margins were thin, and nothing about the early days screamed “future global giant.”

But the location mattered. Ningbo didn’t just have skills. It had logistics. The port of Ningbo–Zhoushan would go on to become the world’s busiest port by cargo tonnage and, since 2010, the world’s third-busiest container port. For a company that would eventually serve customers in Japan, Europe, and North America, that proximity to the water was a quiet but compounding advantage.

And inside the factory, there was another advantage forming—human capital. Ma Jianrong grew up close to the plant through his father, who became deputy manager there. Like his father before him, Ma started as an apprentice at 13. In 1990, he joined Shenzhou’s knitting and weaving department. The wider textile industry in Zhejiang was under pressure then, and the easy path would have been to treat Shenzhou like just another local factory trying to stay alive.

Instead, it became the training ground for a young man who was learning, firsthand and from the floor up, how this industry really worked. The next phase of Shenzhou’s story—the one that turns a local operation into a system the biggest brands in the world would come to depend on—starts with him.

III. Ma Jianrong: The Factory Worker Who Became a Billionaire

Ma Jianrong’s life tracks neatly with China’s modern economic arc: from the disruption of the Cultural Revolution era to the precision of today’s global supply chains. But what makes his story unusual isn’t that he came from the factory floor. It’s that he never stopped treating the factory floor as the main event.

He started early. At 13, Ma became an apprentice in the textile industry. He did stints at Shaoxing Cotton Mill and the Hangzhou Linping Knitting and Garment Plant, learning the work the hard way—by doing it. In 1970s China, that path wasn’t rare. Formal schooling was often interrupted, and practical skills were the safest currency. What would become rare was what Ma chose to do with that experience.

In 1989, he joined the Shenzhou operation in Ningbo and became manager of the knitting and weaving department. He was following his father, Ma Baoxing, who had moved to Ningbo and been appointed deputy manager of the newly established plant. Textiles weren’t just Ma Jianrong’s first job. They were the family trade.

From there, Ma moved through the organization the way you’d want the future leader of a manufacturing empire to move: not in leaps, but link by link. He served as deputy general manager, then general manager, building an operator’s understanding of how each decision upstream shows up later as defects, delays, or wasted cost. In April 2005, he became the acting chairman of Ningbo Shenzhou Knitting Co., Ltd.—a title that reflected what was already true in practice: he knew the business end to end.

Shenzhou also carried the signature traits of a Chinese family enterprise. Relatives held senior roles, including Ma’s brother-in-law, Huang Guanlin, and his cousin, Ma Renhe. That kind of structure can raise governance questions, but it also explains something important about Shenzhou’s culture: deep continuity, long institutional memory, and a tight circle of trusted leadership around a business where execution is everything.

One moment in particular seems to have hardened Ma’s worldview. In March 1992, he traveled to Japan to visit customers. During the trip, he was invited into a smoking room. Before he could even finish a cigarette, a representative from the Japanese company asked—quality-control calm, but deadly serious—why the color in a batch of clothing they’d received faded after washing.

Ma later described how the question instantly wiped out his appetite: he didn’t want to smoke, didn’t want to eat, just wanted to fix the problem. The resolution was brutal and simple. The clothes were burned. The issue was eliminated. The loss hurt—but the relationship survived.

It’s an incident that captures Ma’s core belief: in manufacturing, quality isn’t a preference. It’s the whole contract.

That philosophy shows up clearly in how he described Shenzhou’s ambitions to Zhejiang Business magazine: “People say first-class firms make the standards, second-class firms make brands and only third-class firms make products. But we insist on doing just one thing, and we insist on doing it well.” It’s a direct rejection of the idea that manufacturers are doomed to be interchangeable—that the only way to “move up” is to chase branding or abandon the factory for something flashier.

Ma bet on a different kind of advantage: become so good at making the product that the product becomes inseparable from you. A moat made of process.

True to that mindset, he stayed out of the spotlight. While many Chinese billionaires cultivated public personas, Ma kept a low profile and focused on operations. His net worth has been estimated at $15 billion, largely tied to his stake in publicly traded Shenzhou International. According to the company’s 2024 semi-annual report, he controlled 36% of the business through the holding company Keep Glory, including shares held by his father and credited to Ma to reflect his control and role as chairman.

From a 13-year-old apprentice to the controlling shareholder of a company trusted by the world’s most demanding apparel brands—Ma Jianrong’s rise is a classic China-opening story. But it wasn’t luck or timing alone. The real differentiator was the strategy he built next: a system that made Shenzhou harder and harder to replace.

IV. The Vertical Integration Playbook: Why Shenzhou Is Different

In apparel manufacturing, specialization is the default setting. One company spins yarn, another knits fabric, a third dyes it, a fourth cuts and sews, and then everyone prays the handoffs work. Most of the time, the brand ends up acting like a general contractor, managing a chain of suppliers where any weak link can turn into delays, defects, or finger-pointing.

Shenzhou made a very different choice. It built itself into one of the world’s largest vertically integrated knitwear manufacturers—meaning it pulls the entire production process under one roof, from sourcing raw materials to delivering finished garments.

In practice, that “vertical integration” isn’t an abstract strategy term. It’s a very specific menu of capabilities: customized fabric development, dyeing, finishing, printing, embroidery, cutting and sewing, plus packaging and logistics. In other words, Shenzhou isn’t a single factory in the chain. It is the chain.

And that changes the experience for a brand. Imagine Nike wants to launch a new technical running top with a new feel, a new stretch profile, a new moisture behavior—something that has to perform the same way in every store, in every country, at scale. In the specialized model, Nike would be coordinating multiple suppliers across multiple steps, each with its own standards, timelines, and incentives. Every transition point is a risk: the fabric looks right but dyes wrong, the dye holds but the finishing changes hand-feel, the garment factory can’t hit tolerance, the schedule slips.

With Shenzhou, it’s one partner. One system. If something goes wrong, it doesn’t get “owned” by the next factory down the line. It stays inside Shenzhou until it’s solved.

Ma Jianrong pushed this integration deliberately—extending the industrial chain into fabric manufacturing, dyeing and finishing, printing and embroidery, then tailoring and sewing. The payoff wasn’t just lower costs. It was fewer bottlenecks and faster cycles, because the slowest handoff in the chain was now an internal problem to engineer away.

It also reshaped Shenzhou’s competitive position. Apparel manufacturing is crowded and unforgiving, with factories across China, Vietnam, Bangladesh, and beyond competing on price. If you’re “just” a garment maker, you’re stuck in a constant race to the bottom. Vertical integration was Shenzhou’s exit ramp from that trap. By controlling more stages, it could capture value in more places, tune the entire process as one system, and offer a level of consistency that pure-play factories simply couldn’t.

That system showed up in performance. Shenzhou’s vertically integrated operations and management discipline improved productivity—raising per-person output from about 4,500 garments in 2017 to about 5,000 in 2019—and shortened the production cycle to around 45 days, versus roughly three months for traditional manufacturers. For urgent orders, it could move even faster—sometimes as quickly as 15 days.

In an industry where fashion cycles keep tightening and inventory risk is everything, that speed is a weapon.

It also creates stickiness. Shenzhou’s one-stop model gives brands better control of quality and costs, and it drives up switching costs. Once a customer has qualified Shenzhou’s facilities and processes, and built products around what Shenzhou can reliably do, walking away isn’t as simple as finding another sewing line. You’d need another end-to-end system.

That’s the strategic core of Shenzhou. Competitors may be big in one slice of the chain. Shenzhou owns the whole thing—and with it, the compounding advantage of process knowledge, coordinated capital investment across multiple technologies, and trust earned by delivering, repeatedly, across the full cycle.

V. The First Big Break: Winning Uniqlo's Trust (1997)

Every great company has an inflection point—a moment when one decision quietly determines the next twenty years. For Shenzhou, that moment arrived in 1997, right as the Asian financial crisis was ripping through the region.

Up to then, Shenzhou had been building the machinery of a serious manufacturer: better knitting, better dyeing, tighter processes. But Ma Jianrong and his team also made a strategic choice about who they wanted to serve. Instead of chasing every possible order, they leaned into Japanese mid-market apparel brands—customers who were demanding, consistent, and willing to reward reliability. That gave Shenzhou dependable revenue, and just as importantly, the space to keep investing in what it did best.

Then Uniqlo called.

The timing could not have been worse, or better. With the crisis squeezing margins, Japanese companies were cutting costs and tightening supply chains. Uniqlo—still early in its global rise—needed manufacturing partners it could trust: cost-effective, yes, but also fast and dependable.

That’s when Shenzhou took on the order that became legend inside the company: roughly 350,000 pieces, needed in 20 days.

It’s hard to overstate what that meant in 1997. This wasn’t a routine production run with a comfortable buffer. It was a high-wire act. If Shenzhou failed to deliver on schedule, the consequences wouldn’t just be a disappointed customer—it could put the business itself at risk.

Shenzhou took the job anyway.

Ma decided they would deliver, and the organization bent around that promise. Workers put in long overtime. The factory ran at full tilt. And Shenzhou shipped the order on time.

That one act—execution under extreme pressure—did two things at once. It won Shenzhou a major customer, and it established the most valuable asset a contract manufacturer can ever earn: credibility.

From that point on, Shenzhou remained a Uniqlo supplier. And the experience of serving an exacting Japanese client became a forcing function for the entire company. Quality systems tightened. Processes improved. Reliability became cultural, not just procedural. Shenzhou didn’t just grow; it leveled up.

By the early 2000s, Shenzhou was accelerating. In 2001, it ranked first domestically in the knitting industry for sales revenue, total profits and taxes, and total profits.

But Uniqlo didn’t just shape Shenzhou’s manufacturing. It pulled Shenzhou into something more enduring: development.

Shenzhou began offering its core customers value-added R&D—helping research and develop advanced, professional fabrics. Over time, that work would include signature products like AIRism for Uniqlo, and later Dri-FIT, TechFleece, and Flyknit for Nike.

This is the subtle shift that explains Shenzhou’s staying power. When you’re helping develop what a brand sells—not just sewing what it already designed—you stop being interchangeable. The relationship moves from vendor to partner. Switching becomes painful, slow, and risky.

And that’s the trust equation Shenzhou proved with Uniqlo: deliver when the stakes are highest, deliver consistently after that, and contribute to innovation along the way. If Shenzhou could meet Uniqlo’s standards, the logic went, it could meet anyone’s.

VI. Inflection Point #1: The 2005 IPO & Nike Factory

By the mid-2000s, Shenzhou had already proven it could win—and keep—the trust of Uniqlo and other demanding Japanese brands. But it was still, in the eyes of the world, “a very good manufacturer in China.”

That changed in 2005.

Shenzhou went public in Hong Kong, listing on the HKEX on November 24, 2005. The IPO priced at HK$2.60 per share, and major shareholders included Wing Tai (Hong Kong) Investment Co., Ltd. Going public did more than raise money. It pushed Shenzhou into the open with a level of transparency and institutional credibility that global brands and investors understand instantly: this wasn’t a small, family-run factory anymore. It was a platform.

And Shenzhou used that platform quickly. In September 2006, it established a dedicated Nike factory—purpose-built around Nike’s requirements, from quality standards to production processes to development timelines. This wasn’t just “Nike is a customer.” It was “Nike has a home inside Shenzhou.”

That dedicated-factory model was a new kind of relationship. Instead of multiple brands sharing generic capacity, Shenzhou created specialized capacity for its most important customers—designed to ship their products better, faster, and more consistently than a general-purpose facility ever could.

Two years later, Shenzhou replicated the playbook with an Adidas-dedicated factory. In 2005–2006, it became an apparel supplier to both Nike and Adidas, deliberately moving into sportswear—one of the fastest-growing, most technically demanding segments in apparel. By 2019, sportswear manufacturing accounted for 72% of Shenzhou’s revenue.

The bet was straightforward: basics are crowded; performance is sticky. If you can help brands win in performance, you’re not competing with the lowest bidder—you’re competing with “good enough,” and Shenzhou was aiming to be the opposite of that.

Then came the project that made the shift undeniable: Flyknit.

Nike’s Flyknit technology—those knit, engineered shoe uppers—required manufacturing techniques and equipment that weren’t standard issue in garment factories. Shenzhou invested in specialized machines to produce lightweight Flyknit uppers, and as Nike leaned harder into the platform, Shenzhou’s Flyknit work grew with it. Flyknit upper orders rose from about 2% of Shenzhou’s revenue in 2012 to about 6% in 2016. Today, around 70% of Nike Flyknit fabrics are manufactured by Shenzhou.

This is where Shenzhou stops being “a supplier” and becomes a capability. When a brand’s signature technology depends on your process, switching isn’t a procurement decision anymore—it’s a product decision.

The scale of the relationship shows it. Shenzhou alone receives about 20% of Nike’s total apparel orders. For a company as large and globally sourced as Nike, that level of concentration is extraordinary. It’s a sign of trust, but it’s also a sign of lock-in: specialized factories, co-developed fabrics, hard-won production know-how, and a quality record built over years.

Underneath it all was a quiet evolution in what Shenzhou actually sold. It began as an OEM, producing to someone else’s specifications. But as it invested in equipment, processes, and development support for customers like Nike, it moved toward ODM work—contributing more of the “how” behind the product, not just the labor to assemble it.

And in manufacturing, that difference is everything. Price-competitive suppliers are plentiful. Capability-essential partners are not.

VII. The Athleisure Megatrend & Rising Market Share

To understand Shenzhou’s rise from elite supplier to quiet superpower, you have to zoom out to the force that reshaped the entire apparel industry: athleisure.

For decades, the money in textiles was made in the unglamorous staples—work shirts, polos, basic pants—high volume, low differentiation, and constant price pressure. Then consumers started living in performance fabrics. Gym clothes became everyday clothes. And sportswear brands didn’t just ride the wave; they consolidated power as they did it, taking a bigger share of the market and demanding more from their supply chains.

That shift played perfectly to Shenzhou’s strengths. Performance apparel is less forgiving than basics. Fabrics have to stretch the right way, breathe the right way, wash the right way, and feel the same in every country, in every store, across massive runs. If you’re a brand, you don’t want “another factory.” You want a partner who can repeatedly deliver precision—and help you innovate.

The same story shows up in footwear. Athletic shoes increasingly use knitting for the upper instead of leather or synthetic leather. That’s not a minor material substitution; it’s a manufacturing regime change. Knitted uppers require specialized know-how and tight process control, exactly the terrain Shenzhou has spent decades mastering. Shenzhou became Nike’s biggest supplier of knit uppers because when Nike decided lightweight, form-fitting knitted uppers were the future, Shenzhou was one of the few players who could produce them at scale.

Then the second tailwind kicked in: supplier consolidation.

In recent years, Nike and Adidas have both reduced the number of suppliers they use. The logic is simple: fewer partners, larger partners, better execution, better cost efficiency, less coordination overhead, and less risk. But consolidation doesn’t help everyone. It creates winners and losers—because when a brand cuts suppliers, it needs the remaining ones to do more.

Shenzhou is built for that “do more.” It has scale, vertically integrated control, and R&D capability—exactly what big brands want as they simplify their supply chains and double down on proprietary fabrics and techniques.

You can see the business mix leaning into that demand. In 2024, sportswear remained the engine of Shenzhou’s revenue, with leisurewear and underwear growing faster off a smaller base—together reflecting how much consumer demand has shifted toward comfort, stretch, and performance-led basics.

And then there’s the statistic that really tells you where Shenzhou sits in the ecosystem: it doesn’t just supply these brands; it supplies a meaningful slice of them. Shenzhou is responsible for roughly 16–17% of Nike’s apparel procurement, about 13–14% of Adidas’s, about 13–14% of Uniqlo’s, and around 40% of Puma’s. The top four customers consistently contribute over 80% of Shenzhou’s revenue.

On paper, that kind of concentration looks like a risk. In reality, for Shenzhou it’s a signal: these aren’t casual vendor relationships. They’re deep partnerships where switching costs are real—dedicated capacity, qualification history, shared development work, and hard-earned trust.

You can see how that trust evolved over time. By December 2008, Uniqlo accounted for about 30% of Shenzhou’s revenue and outsourced a meaningful portion of its garments to the company, making Shenzhou a strategic supplier. But the center of gravity eventually moved. Uniqlo was once the biggest customer; Nike became the largest in 2014—reflecting both Nike’s growth and how central Shenzhou had become to technical sportswear manufacturing.

The most important point is what happened inside those relationships: Shenzhou’s order growth often outpaced its customers’ retail growth. That’s the clearest sign of competitive advantage in a supplier business. It means that even when the brand is growing at a steady pace, Shenzhou is taking a larger share of the wallet—becoming more important over time, not less.

Put it all together and Shenzhou’s growth engine becomes surprisingly clean: a global shift toward athleisure, plus brands concentrating orders into fewer best-in-class partners, plus Shenzhou steadily gaining share within the partners it already has. As long as consumers keep choosing performance-led clothing—and the biggest brands keep simplifying their supply chains—Shenzhou is positioned to capture an outsized slice of the upside.

VIII. Inflection Point #2: The Southeast Asia Expansion (2005-2020s)

If vertical integration made Shenzhou hard to replace, geography made it hard to disrupt.

After listing on Hong Kong’s Main Board in 2005, Shenzhou started building a second engine of advantage: a manufacturing footprint outside China, with factories in Cambodia and Vietnam. On the surface, this looked like the familiar playbook of moving south for cheaper labor. But Shenzhou’s version was more strategic. It was about durability—creating a supply chain that could keep running even as costs rose, regulations tightened, and geopolitics turned volatile.

The timing mattered. In 2005, China was still the obvious place to make apparel at scale: low wages, strong infrastructure, and an unmatched ecosystem of suppliers. But the direction of travel was clear. Wages would rise. Environmental rules would get stricter. And the risk of trade friction would only grow. Shenzhou expanded before those pressures became emergencies.

Over time, it built production bases across Phnom Penh, Cambodia; Ningbo and Anqing, China; and Ho Chi Minh City and Tây Ninh, Vietnam. And as the broader industry entered what many called the “decade of out-migration” after 2010—when Chinese foundries increasingly relocated to Southeast Asia—Shenzhou was already ahead of the curve, drawn by the region’s labor pool and tax incentives.

In 2018, Shenzhou doubled down in a very tangible way. On 17 September, it announced it had secured additional leased land in Cambodia—more than 400,000 square meters—for 50 years, and planned to invest US$100 million to build a downstream garment production facility there to expand overall capacity.

By the 2020s, Shenzhou had become a textbook example of this “migration southward.” About half of its production capacity sat in Vietnam. Overseas capacity kept scaling too: a new fabric factory in Vietnam was nearing completion, and a new garment factory in Cambodia began production in March 2025.

What makes this expansion different from simple cost arbitrage is that Shenzhou kept its integrated model intact across borders. The upstream fabrics used by the Cambodia and Vietnam garment factories were fully supplied by Shenzhou’s fabric plant in Vietnam—without needing imports from China. That detail turns out to be decisive.

It’s also why the US–China trade war landed softly here. With production spread across China, Vietnam, and Cambodia—and with fabric sourcing in Vietnam feeding those Southeast Asian lines—Shenzhou had real flexibility. Its exposure to the US was relatively small, and its operational layout meant it wasn’t forced into a frantic relocation when tariffs and policy noise escalated in 2018 and 2019. Where many manufacturers scrambled, Shenzhou mostly adjusted.

Looking forward, expansion in Vietnam, Cambodia, and Ningbo remained central to its growth plan. Each additional facility served two purposes at once: improve cost structure and reduce concentration risk. And increasingly, it also met a practical customer requirement—brands that wanted meaningful production capacity outside China for their own geopolitical reasons.

The investor takeaway is simple: Shenzhou’s geographic diversification wasn’t reactive panic. It was proactive design. Management saw where the industry was headed and built the alternative capacity before it was urgently needed. In a business where disruptions can wipe out seasons, that kind of foresight is a competitive advantage all its own.

IX. The Retail Detour & Strategic Refocus

Even the most focused companies can feel the pull of “just one more thing.” Shenzhou wasn’t immune. The difference is that it treated that temptation like a test—and when the results came back, it was willing to walk away.

During the 2010s, Shenzhou ventured into retail, operating 47 clothing stores across the Yangtze River Delta. On paper, the logic was easy to understand. Shenzhou was already making products for the world’s biggest apparel brands. It knew fabrics, construction, fit, and quality better than almost anyone. So why not capture some of the margin at the end of the value chain?

But retail is a different sport. Manufacturing rewards process, repetition, and control. Stores demand brand building, consumer marketing, real estate judgment, point-of-sale inventory management, and frontline hiring and training. None of that is impossible—but it’s not what Shenzhou had spent decades perfecting. And there was an uncomfortable strategic wrinkle too: running your own stores can put you uncomfortably close to competing with the very brands that trust you to make their products.

More than anything, retail pulled attention away from Shenzhou’s real advantage. Every cycle spent thinking about store layouts and promotions was a cycle not spent on what made the company indispensable: manufacturing excellence, customer development, and expanding capacity.

So Shenzhou did the disciplined thing. It progressively divested the retail outlets and refocused on knitwear production—the business it could be best in the world at.

The move showed up in the numbers. Shenzhou recorded resilient revenue growth in the first half of 2020, due mainly to discontinuing its retail business. In other words: the company got stronger by going back to what it was built to do.

For long-term investors, this detour is comforting, not concerning. It’s evidence of a management team willing to admit when something isn’t working and to correct course early—rather than doubling down on a diversification story that sounds great in a boardroom and drains value in reality.

The lesson is simple and timeless: the best companies are defined as much by what they refuse to do as by what they choose to do.

X. Navigating Crises: COVID, Power Outages & Recovery (2020-2024)

From 2020 through 2024, Shenzhou ran into the kind of stress test you don’t model in spreadsheets. A global pandemic. Supply chain snarls. China’s power crunch. Then the post-COVID demand whiplash. Each one could have been a standalone crisis; instead, they arrived back-to-back.

China’s power supply cuts began rising sharply in the second half of 2020 and escalated into a full-blown crisis in September 2021. The suspected drivers were a mix of Beijing’s carbon-reduction targets and an acute coal shortage.

What made it especially jarring is that China hadn’t seen outages like this in more than a decade. But in the winter of 2020, provinces including Hunan, Jiangxi, Inner Mongolia, and Zhejiang faced serious power constraints. Then it happened again in September and October 2021, when 18 of China’s 30 provinces were affected.

The impact reached all the way to the coast. Wen Biao, general manager at Qianhe Technology Logistics in Shenzhen, said conditions were similar in Shanghai and the port city of Ningbo. For Shenzhou, that mattered immediately: Ningbo is its main production base, and rolling blackouts hit operations directly.

For a manufacturer living on customer commitments and tight delivery windows, power instability is brutal. Lines go dark. Output disappears. Ship dates slip. And the moment that happens, brands start asking the question every supplier fears: can you still be trusted with the next season?

This is where Shenzhou’s earlier decision to diversify geographically stopped looking like a cost move and started looking like an insurance policy. With meaningful production capacity in Vietnam and Cambodia—outside the blast radius of China’s power crisis—Shenzhou had options. It could keep product moving while others were stuck waiting for electricity.

COVID piled on its own complexity. Shutdowns, logistics disruptions, and uneven demand created a whipsaw that few companies handled cleanly. Even Shenzhou felt it. In the first half of 2023, revenue fell 15% year over year, from RMB 13.5 billion to RMB 11.6 billion, and net earnings declined 10%.

The drivers were straightforward, and painful: softer apparel demand in key markets like the US and Europe, plus weakness in sportswear—something echoed in the results of major industry players like Nike.

Then, the rebound. In 2024, net income rose 36.94% year over year to 6.241 billion yuan, and revenue grew 14.79% to 28.663 billion yuan. Gross margin improved by 3.83 percentage points to 28.1%, helped by higher customer order demand that lifted capacity utilization, and by better efficiency in overseas factories alongside a larger overseas workforce.

Momentum continued into 2025. In the first half of the year, Shenzhou reported revenue of 14.966 billion yuan, up 15.3% year over year, and net income of 3.177 billion yuan, up 8.39%.

Zoom out, and the storyline is clear: Shenzhou didn’t just endure the pandemic era—it strengthened its position. Stability and continuity became the product. In a period when smaller, less diversified suppliers stumbled, brands got a fresh reminder of what Shenzhou really sells: scale, geographic resilience, and operational reliability when the world stops cooperating.

XI. Modern Shenzhou: Scale, Sustainability & Automation

By now, Shenzhou International operates at a scale that would have been almost impossible to imagine when Ma Jianrong was a teenager learning the trade on the factory floor.

The company has 102,690 employees—effectively a small city dedicated to one job: turning yarn into fabric, and fabric into finished garments that show up in closets and gyms across the world.

It’s also not “just” scale. Shenzhou has applied for an estimated 584 patents, including 173 invention patents and 411 utility models. And in a sign of how seriously it takes repeatability and control, it has formulated a series of eighty corporate standards that exceed China’s national standards.

Those patent filings matter because they point to what Shenzhou actually built over decades: not a collection of sewing lines, but a manufacturing system with proprietary know-how—process innovation, fabric development, and production optimization that customers can feel in the final product, even if they never see Shenzhou’s name.

As brand customers have pushed harder on sustainability, Shenzhou has moved with them. The company has adopted practices such as recycling wastewater, reducing energy consumption, and using more sustainable raw materials—less because it makes for good PR, and more because it has become a prerequisite for winning and keeping business with global apparel giants.

On that front, Shenzhou also scores relatively well in external assessments. Its ESG exposure is considered low, and Sustainalytics rates it as “low risk.” More notably, the company has not had any ESG-related controversy so far—an unusually clean record in an industry that lives under constant scrutiny for labor practices and environmental impact.

Then there’s the next frontier: automation. Shenzhou has been investing in advanced robotics and artificial intelligence to improve efficiency and reduce labor costs. In a labor-intensive industry, and with China’s working-age population declining, automation isn’t only about saving money. It’s about ensuring the model keeps working as labor becomes scarcer and more expensive.

What makes all of this easier to execute is that Shenzhou can fund it. The company has net cash, meaning it doesn’t carry a heavy debt load. It also converted a fulsome 90% of EBIT into free cash flow over the last three years, and reported net cash of CN¥12.8 billion, with more liquid assets than liabilities.

That kind of balance sheet strength buys Shenzhou time and options: it can keep investing in automation, sustainability, and capacity without being forced into short-term decisions by creditors or capital markets. In manufacturing, where the winners are often the ones who can keep investing through the cycle, that financial discipline becomes another quiet advantage.

XII. Porter's Five Forces Analysis

To see why Shenzhou has stayed so hard to dislodge, it helps to step back and look at the structure of the industry around it—the forces that shape who wins, who gets squeezed, and who gets replaced.

1. Threat of New Entrants: LOW

To compete with Shenzhou, you don’t just need a factory. You need a system.

A credible challenger would have to invest across the entire chain—fabric production, dyeing and finishing, garment manufacturing, and the logistics to move product reliably at global scale. Shenzhou’s estimated 584 patents and its eighty corporate standards aren’t just paperwork; they represent decades of accumulated process knowledge.

Most importantly, the real barrier isn’t only capital. It’s trust. Relationships with customers like Nike, Adidas, and Uniqlo were built over more than 20 years of delivering on time and at quality, season after season. That kind of confidence can’t be rushed, no matter how much money a new entrant spends.

2. Bargaining Power of Suppliers: MODERATE

On inputs like cotton and polyester, Shenzhou is buying commodities. Prices move, but there’s no single supplier with unique leverage over the company.

What shifts the balance toward Shenzhou is scale. As one of the world’s largest purchasers, it has meaningful negotiating power in procurement. And because it is vertically integrated, it relies less on outside vendors for intermediate steps like processed fabrics—reducing dependency and smoothing the supply chain.

3. Bargaining Power of Buyers: MODERATE-HIGH

Shenzhou mainly produces sportswear for international brands such as Nike, Adidas, Puma, and Uniqlo. That concentration is real, and it creates risk: when a few customers represent most of your revenue, they have negotiating muscle.

But the leverage isn’t one-way. Shenzhou has embedded itself in customers’ product pipelines through specialized capacity and co-developed capabilities, including proprietary technologies like Flyknit. Qualifying a new supplier at this level is expensive, slow, and risky for a brand. So while buyers are large and powerful, the relationship is more interdependent than purely price-driven.

4. Threat of Substitutes: LOW

For performance apparel, knitwear isn’t optional—it’s the foundation. There’s no real substitute for technical fabrics in products like moisture-wicking tops or compression wear.

And while “reshoring” manufacturing to developed markets gets talked about often, at current wage differentials it remains economically difficult at scale. As long as athleisure stays central to how people dress—and there’s little evidence it’s reversing—demand for what Shenzhou makes remains structurally durable.

5. Industry Rivalry: MODERATE

This is still a competitive industry, with capable players like Esquel, Youngor, and Crystal International, as well as manufacturers such as Lu Thai Textile. Many rivals can do premium textiles and large-scale production.

Shenzhou’s edge is that it combines scale with vertical integration, creating cost and execution advantages that are tough to copy. And as brands keep consolidating their supplier bases—choosing fewer partners they can trust with more of the workload—that consolidation tends to reward the largest, most capable manufacturers. In that environment, Shenzhou’s operating model becomes a magnet rather than a target.

XIII. Hamilton's 7 Powers Framework Analysis

Porter helps you map the battlefield. Hamilton Helmer’s 7 Powers helps you identify the weapons. Here’s how Shenzhou stacks up.

1. Scale Economies: STRONG

Shenzhou is massive: over 97,000 employees, more than 250,000 metric tons of fabric produced each year, and roughly 550 million garments moving through its system annually. That kind of throughput matters because it spreads fixed costs across an enormous base, creating unit economics smaller competitors simply can’t touch.

Scale also buys speed. When a core customer needs product fast, Shenzhou can sometimes turn urgent orders in as little as 15 days. That isn’t a “nice to have” in apparel; it’s a competitive advantage that wins seasons.

2. Network Economies: MODERATE

Shenzhou isn’t a network business in the classic sense. But its customer roster behaves like one.

Winning a demanding customer like Nike signals to the rest of the industry that Shenzhou can handle the hardest work at the highest standards. That credibility makes it easier to deepen relationships with Adidas, and that in turn reinforces reputation with Puma. Each big-name customer validates the next, creating a compounding trust effect.

3. Counter-Positioning: STRONG

Many large textile groups chose diversification—into real estate, finance, and other industries. Weiqiao is a common example. Shenzhou went the other way: it stayed focused on manufacturing fast-fashion for foreign brands, and kept reinvesting into the unglamorous craft of making knitwear better, faster, and more reliably.

That focus is a form of counter-positioning. Competitors can’t easily match Shenzhou’s depth without undoing the very diversification strategies they committed to.

4. Switching Costs: STRONG

Shenzhou doesn’t just manufacture. It co-develops.

It provides core customers with value-added fabric R&D, with representative products including AIRism for Uniqlo and Dri-FIT, TechFleece, and Flyknit for Nike. Those co-developed technologies create real lock-in, because a brand isn’t just qualifying a factory—it’s qualifying a system that has learned the product over years.

Layer on quality certifications, compliance history, and Shenzhou’s integrated end-to-end process, and switching suppliers becomes expensive, slow, and risky.

5. Branding: LOW

Consumers don’t buy “Shenzhou.” They buy Nike, Uniqlo, Adidas, Puma.

So Shenzhou doesn’t have consumer brand equity to defend. But in B2B terms, its reputation is powerful. Among global apparel brands, Shenzhou is widely viewed as the gold standard for vertically integrated knitwear manufacturing.

6. Cornered Resource: MODERATE-STRONG

Shenzhou’s cornered resource is a mix of leadership and accumulated know-how.

Ma Jianrong’s operating philosophy, and the institutional learning built over roughly 35 years, are not assets you can purchase off the shelf. He also controls 36% of the business through the holding company Keep Glory.

And the company’s home base matters. Ningbo’s deep textile talent pool—built over decades—gives Shenzhou a concentration of human capital that’s hard to replicate elsewhere.

7. Process Power: VERY STRONG

This is Shenzhou’s true moat.

The company’s focus on product excellence won it the trust of foreign brands, which led to more contracts, more revenue, and more fuel to expand. Over time, Shenzhou didn’t just grow horizontally by adding capacity—it expanded vertically by unifying more of the production chain inside one system, making that system more efficient with every cycle.

That advantage compounds. The process knowledge embedded in hundreds of patents and corporate standards took decades to build, and it can’t be recreated quickly. In an industry full of factories, Shenzhou built something rarer: a manufacturing machine that learns.

XIV. Playbook: Business & Investing Lessons

Shenzhou International’s story isn’t just a case study in apparel manufacturing. It’s a playbook for how to build a durable advantage in an industry that’s supposed to be commoditized.

1. "Do one thing, do it well"

Ma Jianrong built Shenzhou in the opposite direction of the typical “successful China conglomerate” arc. While plenty of peers chased diversification into real estate, finance, and anything with a higher multiple, Shenzhou stayed obsessed with manufacturing. That choice didn’t make headlines. It made the company better. And in manufacturing, depth—earned over years of repetition—beats breadth.

2. Vertical integration as moat

Shenzhou’s defining strategic move was refusing to be “just one link” in the chain. By controlling the value chain end to end—from raw materials all the way to finished garments—it reduced coordination risk, tightened quality control, and compressed timelines. When you own the handoffs, you don’t spend your life negotiating with them. You engineer them away.

3. Win trust through competence, not salesmanship

The Uniqlo relationship didn’t start with a pitch deck. It started with a hard order, delivered under pressure. That kind of execution is the only marketing that matters in a supplier business. And once you’re the partner who delivers when it’s hardest, you become the partner brands hesitate to replace.

4. Geographic arbitrage with strategic intent

Shenzhou’s move into Vietnam and Cambodia wasn’t just a labor-cost play. It was a resilience strategy. The extra footprint created flexibility—tariff insulation during the trade war, and operational continuity when COVID and China’s power disruptions hit. In supply chains, redundancy looks inefficient right up until it becomes the reason you keep shipping.

5. R&D as partnership, not just cost center

Shenzhou didn’t stop at making what brands designed. It helped develop what brands sold. By contributing to products like Flyknit and AIRism, it shifted the relationship from “vendor” to “partner.” That’s where real switching costs come from. If you’re inside the product, you’re no longer competing on price alone.

Key Metrics for Ongoing Monitoring:

For investors tracking Shenzhou over time, three indicators matter most:

- Customer concentration — especially how much revenue comes from Nike, and whether the top four customer relationships remain stable

- Gross margin direction — a simple read on pricing power and operating efficiency across the integrated system

- Capacity utilization and the China vs. Southeast Asia mix — signals how efficiently the network is running and how diversified the risk really is

Investment Considerations:

The bull case is clean: continued demand for athleisure, brands consolidating orders into fewer high-performing suppliers, and Shenzhou’s unusually entrenched position in technical fabrics and execution. The moat isn’t brand equity—it’s capability, trust, and a balance sheet that lets the company keep investing through cycles.

The bear case is equally straightforward: customer concentration (what if Nike materially pulls back?), geopolitical volatility around China-linked manufacturing, and the longer-term possibility that automation makes parts of production more standardized and easier to replicate.

Investors should also keep an eye on tightening ESG scrutiny—disclosure requirements, labor standards, and environmental compliance. Shenzhou’s lack of ESG controversy so far is a meaningful asset in this industry, but it’s not something you can take for granted.

What Shenzhou ultimately proves is that world-class manufacturing—done with focus, discipline, and long-term intent—can be as valuable as any consumer brand or software platform. In an economy that loves to celebrate what’s digital, Shenzhou is a reminder of what’s still physical: someone has to make the products the world wears. And if you build the system that does it best, the rewards can be enormous.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music