Samsung Biologics: How Samsung Built the World's Largest Biotech Factory

I. Introduction: The Factory That Changed Biomanufacturing

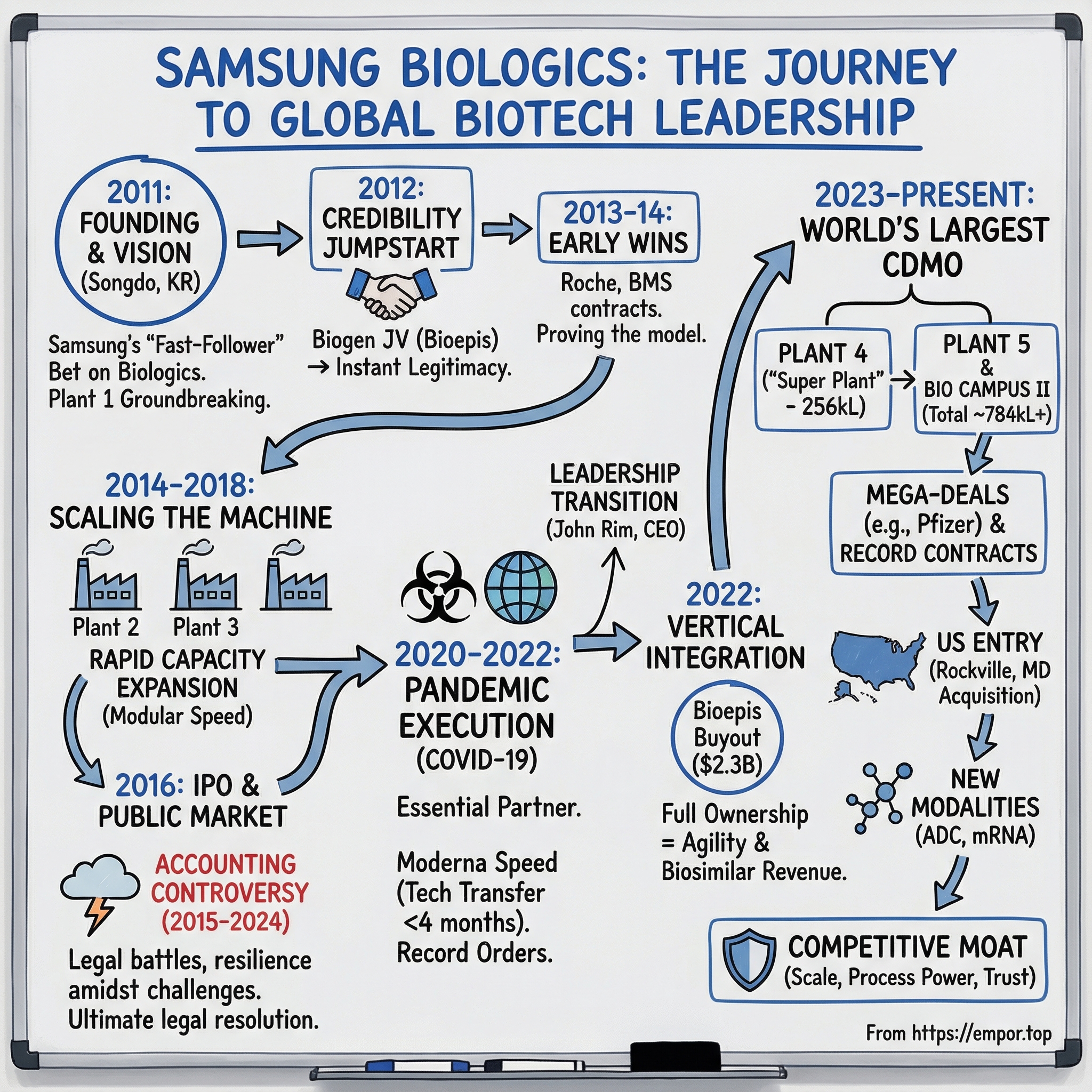

Picture Songdo, South Korea: an industrial district inside a purpose-built city, rising from reclaimed tidal flats along Incheon’s waterfront. In 2011, when Samsung broke ground on a biomanufacturing facility here, it looked like an odd twist in the company’s playbook. This was the conglomerate of smartphones and memory chips walking into one of the most demanding corners of medicine: large-molecule drug manufacturing, where quality systems matter as much as steel and concrete.

Fourteen years later, that “curious bet” is Samsung Biologics Co., Ltd.—a global contract development and manufacturing organization (CDMO) headquartered in Songdo, Incheon, and the biotech arm of Samsung Group. Its work spans the arc of a drug’s life: from late-stage development support to large-scale commercial manufacturing.

The scale of the result is hard to overstate. Samsung Biologics became the first company in Korea’s pharmaceutical and biotech industry to surpass 4 trillion won in annual revenue, posting a record 4.5 trillion won in sales in 2024. And it has built out a total manufacturing capacity of 784,000 liters—enough to make it the world’s largest biomanufacturer at a single site.

So here’s the question at the heart of this story: how did a subsidiary founded in 2011—late to a field dominated by long-established specialists—grow fast enough to outpace industry veterans like Lonza and Boehringer Ingelheim?

The company expects that momentum to continue. For 2025, Samsung Biologics projected revenue growth of 20 to 25 percent year-on-year, forecasting about 5.57 trillion won. That trajectory is what makes Samsung Biologics so fascinating: in 2020 it first crossed 1 trillion won in annual sales, and within five years it was pushing toward five times that.

A few themes explain how this happened. First, Samsung’s “fast-follower” DNA: enter an industry late, then overwhelm the constraints—time, cost, capacity—through relentless execution and capital. Second, a deliberate bet that biologics are the future of medicine, with manufacturing complexity that creates real barriers to entry. Third, the ability to survive—and keep building through—one of the most damaging accounting controversies in modern Korean corporate history. And finally, the pandemic: the moment Samsung Biologics shifted from ambitious newcomer to essential partner for the world’s biggest drugmakers.

II. The Samsung Group Context: Understanding the Chaebol Machine

To understand Samsung Biologics, you first have to understand the organism it came from: Samsung Group—the archetypal Korean chaebol, built to win through scale, speed, and sheer staying power.

Samsung began in 1938, when founder Lee Byung-chul started a small trading company in Daegu selling everyday staples like dried fish, groceries, and noodles. He named it “Samsung,” meaning “three stars,” a statement of ambition: big, strong, and built to last.

Then history hit. The end of World War II, and soon after, the Korean War in 1950, tore the peninsula apart. With the economy shattered and the conflict intensifying, Lee relocated Samsung’s headquarters to Busan to keep the business alive. That move didn’t just preserve the company—it pushed Samsung into its next act: diversification.

Out of the postwar rebuilding era emerged the playbook that would define Samsung and the broader chaebol model: expand relentlessly, cultivate close ties with the state, and invest with long time horizons. Over the next few decades Samsung spread into food processing, textiles, insurance, securities, and retail. Then, in the late 1960s, it stepped into electronics—followed by construction and shipbuilding in the mid-1970s. These weren’t side quests; they became the foundations of Samsung’s modern empire.

A major inflection point came in 1969 with the establishment of Samsung Electronics. But the deeper cultural shift arrived after Lee Byung-chul’s death in 1987, when his third son, Lee Kun-hee, became chairman on December 24, 1987. In 1993, frustrated that Samsung was shipping lots of products but not enough excellence, Lee delivered the line that still defines the company’s self-image: “Change everything except your wife and kids.” The “Frankfurt Declaration,” as it came to be known, was Samsung’s internal reset—from volume-driven fast follower to global quality competitor.

The results showed up over the next decade. Samsung kept sharpening manufacturing, quality systems, and supply chains until it could outbuild and out-execute incumbents. By 2006, it had become the world’s largest TV manufacturer, surpassing Sony.

By the 2000s, Samsung was dominant in memory chips, displays, and smartphones. But leadership also understood the trap of mature hardware businesses: commoditization and margin compression. If Samsung wanted a new “next Samsung Electronics,” it needed businesses with higher barriers to entry, longer product cycles, and more durable moats.

Biopharma fit that bill.

The decision to enter biologics manufacturing wasn’t a random leap—it was an attempt to apply Samsung’s core strengths to a new bottleneck industry: world-class process engineering, the willingness to spend billions before revenue arrives, and the muscle memory of building complex global supply chains at scale. Samsung had entered semiconductors late, invested aggressively, compressed timelines, and fought its way to leadership. The question was obvious: why not run the same playbook in biomanufacturing?

Even the ownership structure signaled that this was a strategic bet, not a small experiment. Samsung Biologics sits inside the group’s core orbit: Samsung C&T holds a 43.4 percent stake, and Samsung Electronics holds 31.5 percent. In other words, the biotech push had both the oversight of the group’s holding structure and the financial firepower of the company that prints cash.

And with that backing, Samsung was ready to start building.

III. The Founding Vision: Birth of Samsung Biologics (2011-2014)

In April 2011—still in the long shadow of the global financial crisis, and in a year marked by the Fukushima disaster—Samsung Biologics officially came into existence. It was a new company with a very un-Samsung-sounding mission: become a top-tier manufacturer for the world’s most complex medicines.

The bet rested on one big conviction: biologics were going to be the future of healthcare. These are large-molecule drugs like monoclonal antibodies, made not by chemistry but by living cells grown in giant bioreactors. That shift changes everything. Manufacturing becomes the hard part—specialized facilities, unforgiving quality systems, and deep regulatory know-how. For most would-be entrants, that complexity is a wall. For Samsung, it looked like an opening.

Instead of trying to become a drug discovery company—an expensive, failure-prone game—Samsung went after the infrastructure layer. The contract development and manufacturing organization (CDMO) model let Samsung do what it does best: build world-class factories and run them with industrial precision, while letting pharmaceutical companies keep their capital focused on pipelines rather than bricks and mortar.

Then came the location decision. Samsung didn’t stitch together a patchwork of acquisitions. It chose a single mega-site in Songdo, a purpose-built district designed for scale. South Korea offered lower labor costs than the US and Europe, a supportive regulatory environment, and a practical bridge between Western drug developers and fast-growing Asian markets.

And once the plan was set, Samsung did the Samsung thing: it built fast. Plant 1 broke ground in May 2011—just one month after the company was founded. Over the following years, Samsung Biologics would keep expanding, ultimately building four manufacturing plants from 2011 to 2023, with total capacity eventually exceeding 600,000 liters.

The Biogen Joint Venture: Instant Credibility

For all the construction speed, Samsung still faced the industry’s biggest hurdle: trust. In biologics, your reputation for quality and compliance isn’t marketing—it’s your product.

That’s why the most important early move happened in 2012, when Samsung established Samsung Bioepis, a biosimilar developer, as a joint venture with Biogen. The partnership was designed to develop, manufacture, and market biosimilars, with governance formalized through a board structure.

Biogen brought something Samsung couldn’t simply buy on day one: credibility. It was a pioneering American biotech company, known for deep expertise in neurology and multiple sclerosis. Having Biogen on the cap table sent a clear signal to global pharma: Samsung wasn’t dabbling. It was building a business that could meet Western standards.

The structure was also clean and strategic. Samsung Biologics would focus on being the CDMO—the manufacturer-for-hire. Samsung Bioepis would build a portfolio of biosimilars, the biologics equivalent of generics. To support that effort, Bioepis began building an R&D center on the Songdo site, with completion targeted by the end of the year.

The model worked quickly. In 2013, Samsung Biologics landed early deals with Roche and Bristol-Myers Squibb. Winning two of the world’s biggest pharmaceutical companies so soon after launch was a powerful proof point: Samsung’s pitch—speed, price competitiveness, and rapidly scaling capacity—was starting to cut through.

IV. The Scaling Machine: Plants, Capacity, and Speed (2014-2018)

Once Samsung Biologics proved it could win real clients, the next problem was obvious: you can’t manufacture trust at scale without manufacturing capacity at scale. And in this business, capacity isn’t just equipment—it’s years of construction, qualification, validation, and regulator sign-off.

Samsung’s edge in biologics turned out to be the same edge that made it formidable in semiconductors: it could build big, complex factories faster than the industry thought was reasonable. The playbook looked familiar—modular design, parallel workstreams, aggressive timelines, and a culture that treats schedules like product specs.

In biomanufacturing, a new facility can take five to seven years from groundbreaking to regulatory approval. Samsung aimed to compress that to roughly two to three years, applying the kind of engineering rigor and project discipline it had honed building chip fabs—only now the end product wasn’t silicon. It was medicine.

The results showed up quickly in sheer footprint. From its founding in 2011 through 2023, Samsung Biologics built four manufacturing plants with total capacity of more than 600,000 liters. By 2018—after completing its third plant and expanding its sCMO facilities—the company had reached 364,000 liters of capacity, the largest among global CMO companies at the time.

The go-to-market strategy was simple, expensive, and bold: build ahead of demand, then sell certainty. Drugmakers were staring at a bottleneck as biologics moved from clinical promise to commercial reality, and there wasn’t enough global capacity to go around. Samsung positioned itself as the place you could go when you couldn’t afford to wait.

The IPO and the Storm Clouds

In November 2016, Samsung Biologics went public on the Korea Exchange in South Korea’s second-largest share sale. The market wasn’t just buying a new factory operator—it was buying the idea that Samsung could industrialize biologics the way it had industrialized electronics.

But even as the company was scaling, the foundations of its credibility were about to be tested.

South Korea’s financial regulator later suspended trading of Samsung Biologics’ shares and fined the company 8 billion won after ruling that it had committed accounting fraud in 2015—allegedly inflating its value ahead of the 2016 IPO.

The Accounting Controversy

At the center of the fight was Samsung Bioepis, the Biogen joint venture that had given Samsung instant legitimacy in the first place.

Samsung Biologics faced accusations that it improperly inflated the value of its stake in Bioepis by changing how it accounted for the JV. After years of losses, the company suddenly reported a dramatic swing to profit in 2015—about 1.9 trillion won—driven by a shift from valuing the stake at book value to fair market value. Samsung argued the change was justified under International Financial Reporting Standards because circumstances had changed around Biogen’s call option.

Regulators didn’t buy it. When South Korea’s Financial Supervisory Service revealed evidence of accounting rule violations, the market reacted violently—wiping out about $6 billion in value, with shares falling nearly 20 percent.

Then the story took a darker turn: prosecutors alleged evidence was destroyed and concealed. A court sentenced three Samsung Electronics executives to jail for evidence tampering tied to the investigation. Prosecutors said computers and servers from Samsung Biologics were buried beneath factory floors to hide them.

“Destroying and hiding evidence in a group-wide move regarding the accounting fraud case that was an issue the public took interest in is not a light crime,” the court said. “The methods for concealment, which are difficult for an average person to imagine, also shocked society.”

Prosecutors described a coordinated cleanup: decisions to delete data ahead of raids, repeated instructions to remove related files, efforts to erase log records, and even formatting and replacing specific computers. Data was deleted from shared folders on main servers, along with traces that might show what had happened.

And there was an even bigger implication. The Bioepis stake—and how it was valued—sat at the heart of one of the most contentious corporate events in modern Samsung history: the 2015 merger between Samsung C&T and Cheil Industries, opposed by some Samsung C&T shareholders. Critics argued that the accounting treatment boosted the value of Cheil’s stake in Samsung Biologics and influenced the merger ratio in ways that benefited the Lee family’s control of the group.

Resolution After Years of Legal Battle

The saga stretched for years, with the business continuing to build while the legal process churned. In August 2024, Seoul Administrative Court ruled that South Korea’s financial regulator should cancel the disciplinary actions imposed in 2018 over the alleged accounting standard violations.

And in the broader merger-related case, Samsung Electronics Executive Chairman Jay Y. Lee was ultimately cleared by South Korea’s Supreme Court, which upheld a Seoul High Court ruling acquitting him and other Samsung officials of all 19 charges tied to the 2015 merger.

“Today’s final ruling by the Supreme Court has clearly confirmed that the merger of Samsung C&T and the accounting treatment of Samsung Biologics were lawful,” Samsung’s legal counsel said in a statement.

What this episode revealed—regardless of where you land on the accounting—was the unique risk profile of doing business inside a chaebol. Cross-holdings, family control, succession dynamics, and corporate governance can collide with operational excellence in ways that surprise outsiders. For Samsung Biologics, the key fact is this: even with the controversy raging, the factories kept going up—and the company kept winning work.

V. The COVID-19 Pandemic: Samsung's Moment on the Global Stage (2020-2022)

If the accounting scandal stress-tested Samsung Biologics’ credibility, COVID-19 became the proving ground for its execution. The pandemic didn’t just create demand for vaccines and therapeutics—it created a worldwide shortage of the one thing you can’t improvise in a crisis: qualified biomanufacturing capacity. And Samsung had spent the previous decade doing exactly what the moment required—building plants, refining quality systems, and getting comfortable operating at scale.

Samsung Biologics was one of the few manufacturers that saw a real production boost during the pandemic years. In 2020, its CDMO profile rose sharply as it stacked up traditional Big Pharma manufacturing contracts alongside COVID-focused production pacts. That year alone, the company secured $1.7 billion in orders, including a $362 million deal with Vir Biotechnology to scale up production for a monoclonal antibody COVID-19 candidate.

As the crisis unfolded, Samsung Biologics landed pandemic-period contracts with Eli Lilly, AstraZeneca, Moderna, GreenLight Biosciences, and GlaxoSmithKline—covering both vaccines and therapeutics. The signal to the market was simple: Samsung wasn’t just big. It was ready.

The Moderna Partnership That Changed Everything

The headline partnership was Moderna. The two companies announced a Manufacturing Services and Supply Agreement under which Samsung Biologics would provide large-scale, commercial fill-finish manufacturing for mRNA-1273—Moderna’s COVID-19 vaccine. The point wasn’t just the contract value; it was the speed. Technology transfer began immediately at Samsung’s Incheon facilities, using an aseptic fill-finish line designed to handle the full downstream workflow, including labeling and packaging, with the goal of supporting production of hundreds of millions of doses.

“This is truly a significant milestone as we were able to accelerate the approval process in close and prompt collaboration with the Korean government and Moderna, especially under the MFDS’s rigorous screening for the first fill-finish manufacturing of mRNA vaccines in Korea,” said John Rim, CEO of Samsung Biologics.

It was the first time a local company helped manufacture an mRNA vaccine and received approval from Korea’s Ministry of Food and Drug Safety. Just as importantly, it showcased a capability that separates serious CDMOs from everyone else: rapid technology transfer. Samsung said its average tech transfer timeline was three to four months, versus an industry norm closer to six. Even in the chaos of the pandemic, it completed the Moderna tech transfer in three months and secured government approval within five.

During COVID-19, Samsung Biologics handled fill-finish, packaging, and labeling for Moderna’s Spikevax, and it was also contracted to manufacture Eli Lilly’s COVID-19 antibody therapeutic and AstraZeneca’s long-acting antibody therapeutic. In a global emergency where time was the currency, Samsung’s ability to absorb a process fast—and then run it reliably—became its calling card.

Leadership Transition

That momentum was amplified by a leadership shift at exactly the right time. John Rim took the helm in late 2020 as President and CEO, and also served as Chairman of the Board. Born in South Korea in October 1961, he later emigrated to the United States and became a U.S. citizen.

Rim’s background was unusually well-matched to what Samsung Biologics was becoming. He studied chemical engineering at Columbia and Stanford, earned an MBA from Northwestern’s Kellogg School of Management, and started his career at Booz & Company. He went on to hold CFO roles at the U.S. subsidiary of Yamanouchi, at Genentech, and at Roche’s U.S. subsidiary, and then worked across Genentech/Roche in senior global roles spanning Technical Operations, product development, and R&D in both the U.S. and Europe.

That mix—deep biopharma operations experience plus a global network built inside Western pharma—helped Samsung Biologics break records in orders and sales. And it marked a subtle evolution in the company’s identity: from a Korean manufacturing disruptor to a global CDMO competing on relationships, regulatory confidence, and the ability to execute for the biggest drugmakers in the world.

The "Super Plant" Push

COVID also accelerated Samsung’s next big bet: expanding capacity even further, even faster. Samsung Biologics was already on an expansion sprint, and by 2021 it had the cash and the urgency to push harder—both to extend its footprint in Songdo and to begin preparing for a broader international presence.

The centerpiece was Plant 4, the so-called “Super Plant.” The $2 billion facility in Incheon was designed to nearly double the company’s overall capacity. At 256,000 liters, Plant 4 would take total capacity on Samsung’s Incheon campus to about 620,000 liters—making it the largest single-site biomanufacturing capacity in the world.

VI. Completing the Vertical Integration: The Bioepis Buyout (2022)

In January 2022, Samsung Biologics announced a move that would reshape what the company actually was: it would buy out Biogen’s stake in Samsung Bioepis, the joint venture that had given Samsung instant credibility a decade earlier.

The headline was simple: Samsung Biologics agreed to acquire Biogen’s equity stake for up to $2.3 billion. The structure, though, tells you how carefully this was engineered. Biogen would receive $1 billion in cash at closing, plus $1.25 billion deferred over two payments—$812.5 million after the first anniversary of closing, and $437.5 million after the second. On top of that, Biogen could receive up to $50 million more if certain commercial milestones were hit.

This was the endgame of a relationship that had been evolving since Bioepis’ birth in 2012. Biogen had originally invested for a 15% stake, and the original agreement gave it the right to increase its ownership to up to 50% less one share—a right it exercised in June 2018. By 2022, the JV had done its job: it had helped Samsung enter the market, build capabilities, and win trust. Now Samsung wanted the keys.

To finance the purchase, Samsung Biologics said it would raise 3 trillion won through a rights offering to existing shareholders.

Strategically, the rationale was about freedom of movement. Bioepis was no longer a science project—it had a real, growing biosimilar business. It had successfully launched five biosimilars globally, spanning autoimmune and oncology indications, with another product nearing launch and additional biosimilars in Phase 3 trials. Full ownership meant Samsung could streamline decision-making, reinvest cash flows more cleanly, and push development without the friction that comes with split control.

And there was an elephant in the room that industry watchers openly discussed: the partnership had its tensions. As Bioepis expanded, Samsung Biologics and Biogen could increasingly find themselves overlapping—potentially even competing—especially if Bioepis moved further into areas adjacent to new drug development. Joint ownership, in that view, wasn’t just a governance structure; it was a strategic constraint.

For Samsung Biologics, the buyout marked a clear evolution. It was still, primarily, a CDMO—the factory partner to the world. But now it also fully owned a product business. Instead of earning only manufacturing fees, Samsung could capture the biosimilar revenue stream outright, and with it, a potential pathway toward novel drug development over time.

Bioepis’ performance underscored why that mattered. The subsidiary recorded revenue of 1.537 trillion won and operating profit of 435.4 billion won, with revenue up 51% year-on-year and operating profit more than doubling—driven by deeper global market penetration of its biosimilar products.

VII. The Modern Era: Becoming the World's Largest CDMO (2023-Present)

In the years after COVID, Samsung Biologics didn’t just hold onto the momentum—it turned it into a new baseline. The company cemented its position as the world’s largest biomanufacturer, serving more than 110 clients and counting 17 of the world’s top pharma companies among them. By 2024, those relationships helped push annual contracted value to $4.3 billion, bringing cumulative contracted value since founding to $16.3 billion.

And the other half of the CDMO promise—quality, repeatability, regulator trust—kept pace with the scale. As of December 2024, Samsung Biologics had secured 340 regulatory approvals, the kind of track record that makes risk-averse drugmakers comfortable betting their flagship products on an external partner. By June 2024, CEO John Rim said the company had active partnerships with 16 of the top 20 biopharmaceutical companies worldwide.

The Pfizer Mega-Deals

Nothing captured Samsung’s new standing like Pfizer. In June 2023, Samsung Biologics disclosed a $411 million agreement with Pfizer for commercial manufacturing of Pfizer’s multi-product biosimilars portfolio—at the time, the largest deal of its kind Samsung had ever announced, surpassing a previous top deal with AstraZeneca. It also followed an earlier $184 million Pfizer agreement signed in March.

Then Pfizer doubled down. A month later, Samsung said Pfizer expanded two earlier biosimilar production agreements, bringing the combined value to $897 million. Under the expanded terms, Samsung would provide additional large-scale manufacturing capacity across a multi-product biosimilars portfolio spanning areas like oncology, inflammation, and immunology.

For Samsung Biologics, this wasn’t just revenue. It was validation: one of the world’s most operationally demanding drug companies was effectively saying, “We trust you with our pipeline at scale.”

Record-Breaking Contracts

By 2024, Samsung Biologics was doing something even more impressive: thriving in a tougher post-COVID market. The company stood out across the CDMO industry, most notably by winning three $1 billion-plus multi-year contracts in the second half of 2024—helping drive more than 35% growth in contract value that year, after three straight years of 20%+ growth.

The biggest single headline landed in October 2024: a $1.2 billion contract manufacturing agreement with an undisclosed Asia-based pharmaceutical company, running through December 2037. It became the largest single-client deal in Samsung Biologics’ history, with production set for the company’s Songdo, Incheon site.

Bio Campus II and Continued Expansion

While the commercial engine accelerated, the concrete kept pouring. In 2023, Samsung Biologics began construction of a fifth plant in Incheon.

Plant 4’s ramp to full operations was expected to keep pushing revenue higher, and Plant 5—part of Bio Campus II—was scheduled to begin operations in April 2025. With Plant 5, Samsung Biologics expected total production capacity to reach 784,000 liters. The company also said it was considering a sixth plant, which—pending board approval—would increase total capacity to 964,000 liters. With three additional plants planned, the full campus was on track for completion by 2032.

US Manufacturing Entry: A Strategic Breakthrough

For all of Samsung’s scale in Korea, there was one obvious vulnerability: geography. In late December 2025, Samsung Biologics announced a move designed to close that gap.

The company said its wholly owned U.S. subsidiary, Samsung Biologics America, had signed a definitive agreement to acquire 100% of Human Genome Sciences from GSK for $280 million—its first U.S.-based manufacturing site. The facility is located in Rockville, Maryland, in the heart of a major U.S. bio-cluster, and includes two cGMP manufacturing plants with a combined 60,000 liters of drug substance capacity, supporting both clinical and commercial production across small to large scale.

“We are now positioned to proactively address uncertainties related to US tariff policies, reduce supply chain risks stemming from future policy changes and enhance our responsiveness and flexibility for North American customers,” a company official said.

The transaction was expected to close toward the end of the first quarter of 2026. Samsung said it would retain more than 500 employees at the Rockville site to maintain continuity, and the bigger strategic point was clear: clients could now pursue multi-site manufacturing options across both the U.S. and Korea.

New Modalities and Portfolio Diversification

As the core monoclonal antibody business scaled, Samsung Biologics also widened its lens. The company focused on monoclonal antibodies, bispecific antibodies, antibody-drug conjugates, and mRNA vaccines.

In March 2025, Samsung Biologics began operations at a dedicated antibody-drug conjugate (ADC) manufacturing facility in Songdo, expanding into one of oncology’s most technically demanding modalities. ADCs have emerged as a promising cancer treatment category, but they come with high technological barriers—exactly the kind of complexity that tends to reward manufacturers with deep process discipline.

The market momentum is there too. The Korea Drug Development Fund forecast the global ADC therapy market would grow from $7.7 billion in 2023 to $38.7 billion by 2029, reflecting how quickly this corner of biologics is moving—and why Samsung wants to be a scaled, credible manufacturing partner before the rest of the world catches up.

VIII. The Competitive Landscape & Porter's Five Forces Analysis

By the mid-2020s, the CDMO business stopped being “overflow capacity” and started looking more like strategic infrastructure. Drugmakers weren’t just renting stainless steel. They were outsourcing speed, quality systems, and regulatory confidence.

That shift shows up in the market’s growth. Industry forecasts expect the global biologics CDMO market to expand sharply over the next decade, driven by the continued surge in biologic therapies. North America remains the biggest region, accounting for more than 40% of the market.

Market Structure

At the top of the leaderboard, the biologics CDMO market is dominated by a small group of scaled specialists—most notably Lonza, WuXi AppTec, and Samsung Biologics.

Lonza has built its position through a network of global biomanufacturing sites and mature biologics capabilities that span clinical development through commercial production. WuXi AppTec offers an integrated services model built around fast development timelines and flexible outsourcing. Samsung Biologics, meanwhile, has made its name through sheer capacity, rapid plant expansion, and a manufacturing-and-compliance culture designed to meet Western regulatory standards—while also building capabilities that support both biosimilars and newer biologics.

Porter's Five Forces Analysis

1. Threat of New Entrants: LOW

In biologics manufacturing, money is only the first barrier—and it’s already enormous. A single new plant can cost more than $2 billion, and that still doesn’t buy the hardest asset: a long record of regulatory trust.

Samsung Biologics had amassed 340 regulatory approvals as of December 2024, the kind of track record that takes years of inspections, audits, and consistent performance to earn. And once a drug is in production, switching is painful. Moving a biologic process to a new facility typically means months of validation work and the real risk of regulatory delay. For most drugmakers, that’s not a risk worth taking unless they have to.

2. Bargaining Power of Suppliers: MODERATE

A lot of the industry has standardized around single-use bioprocessing equipment, which reduces supplier power. Scale helps too: Samsung can buy consumables in volumes few competitors can match, giving it real procurement leverage.

Still, not everything is commoditized. Certain specialized inputs and equipment remain concentrated among a limited set of suppliers, which keeps supplier power from dropping too far.

3. Bargaining Power of Buyers: MODERATE-HIGH

The buyers here—Big Pharma—are sophisticated. They negotiate hard, and they often want redundancy. “Big Pharma favors dual sourcing,” said analyst Wi Hae Joo. “Samsung Biologics’ entry to the US is a key event for expanding its order base.”

At the same time, capacity constraints across the industry give top CDMOs meaningful pricing power. And the contracts themselves create stickiness. Many run for five to ten years, and the operational friction of switching midstream makes “buyer power” less absolute than it looks on paper.

4. Threat of Substitutes: LOW-MODERATE

In theory, drugmakers can build their own capacity. In practice, many would rather not. The industry trend has moved toward outsourcing, with global pharmaceutical companies increasingly choosing to place orders with CMOs instead of taking on the time, cost, and operational risk of building new plants.

That preference is even stronger among small and mid-sized biotechs. Venture investors typically want capital to go into the pipeline—clinical data and new indications—rather than into factories.

5. Competitive Rivalry: HIGH

This is a high-stakes, high-intensity market with a handful of giants fighting for long-term programs. Lonza remains one of the dominant forces, reporting sales of CHF 6.7 billion in 2023.

But the rivalry is increasingly shaped by who can offer the most capacity with the fewest execution risks. Samsung Biologics, with 784,000 liters of production capacity across five plants, has outscaled competitors like Lonza and WuXi Biologics, each with capacity in the mid-400,000-liter range. In the global antibody CDMO market, Samsung, Lonza, WuXi Biologics, and Catalent have effectively been sharing the top tier.

And now geopolitics is becoming a competitive force of its own. The BIOSECURE Act is designed to restrict work with “biotechnology companies of concern,” limiting the ability of businesses and institutions to partner with those firms on projects funded by the U.S. government. If enacted, it would prohibit U.S. agencies—and companies receiving U.S. government funding—from contracting with biotech firms designated as “of concern.”

The U.S. has previously named several China-based companies in this context, including WuXi Biologics, WuXi AppTec, BGI, MGI, and Complete Genomics. If the bill becomes law, Chinese CDMOs could face significant restrictions—potentially diverting business toward South Korea and other countries.

Against that backdrop, Samsung Biologics’ move into U.S. manufacturing, including the acquisition of the GSK site, positions it to benefit from customers seeking supply chain options outside China. “We expect some (contract research organizations) and CDMOs based in China will be included on the list of companies of concern,” said Akin, an international law firm.

IX. Hamilton's 7 Powers Framework Analysis

1. Scale Economies: STRONG ✓

Samsung Biologics holds the world’s largest biomanufacturing capacity at 784,000 liters—and in a business where the hard part is running compliant factories, that kind of scale turns into a real economic weapon. The big fixed costs of biomanufacturing—depreciation, validation, regulatory compliance, and the quality systems that wrap around everything—get spread across more production. That pulls down unit costs and gives Samsung leverage with suppliers of equipment and consumables. And the advantage compounds: more volume means more cash, which funds more expansion, which makes the next round of scale even harder for smaller rivals to match.

2. Network Effects: MODERATE

Biologics manufacturing doesn’t have classic, direct network effects the way a marketplace or social network does. But Samsung still benefits from an ecosystem flywheel. The broader the client base, the broader the set of molecules, processes, and regulatory paths the company learns from. Those learnings show up as better execution for the next client—fewer surprises, smoother tech transfers, and more confidence under inspection. Reputation then reinforces the loop: successful programs with major pharma companies make it easier to win the next major pharma company.

3. Counter-Positioning: MODERATE

Samsung’s asset-heavy, “build big and build early” approach counter-positions against how Big Pharma has traditionally operated. For an established drugmaker to replicate Samsung’s capacity, it would need to redirect capital away from R&D into factories, and commit to manufacturing decisions that play out over many years. That’s a tough strategic tradeoff for organizations whose identity—and investor expectations—are built around pipelines, not plants. The result is a structural advantage for Samsung as the outsourced specialist.

4. Switching Costs: STRONG ✓

Once a pharma company has transferred its process into Samsung’s facilities and validated it under regulatory scrutiny, leaving is expensive and slow. Switching CDMOs means repeating months of tech transfer work, potentially running additional studies with product made at the new site, and filing regulatory amendments. That’s real friction, and it’s why relationships in this industry tend to become long-lived. Multi-year contracts and pricing structures layered over time make the partnerships even stickier—and give Samsung strong revenue visibility.

5. Cornered Resource: MODERATE

Samsung’s most defensible “cornered resource” is its accumulated regulatory track record—340 regulatory approvals as of December 2024. That credibility with agencies like the FDA and EMA isn’t something a competitor can buy off the shelf; it’s earned over years of consistent execution. Another cornered resource is relationship capital: Samsung’s work with 17 of the world’s top pharma companies reflects trust built molecule by molecule, campaign by campaign.

6. Process Power: STRONG ✓

Samsung’s operational execution is a core differentiator. It has built facilities faster than any other major player in the industry, and it has shown a standout ability to absorb new programs quickly through technology transfer. Samsung Biologics cites an average tech transfer timeline of three to four months, compared with an industry standard closer to six.

This is Samsung DNA applied to biology: the process discipline, project management, and manufacturing rigor honed over decades in semiconductors and other complex industries. It’s not easily copied through licensing, and it’s hard to replicate quickly through acquisition.

7. Brand: MODERATE-STRONG

In a risk-averse industry, brand is less about hype and more about confidence—quality, reliability, and the belief that production won’t become the thing that jeopardizes a drug launch. Samsung Biologics has built that reputation, including receiving the 2024 CDMO Leadership Award in all six performance categories: quality, reliability, capabilities, expertise, compatibility, and services. That brand equity helps attract high-value clients and supports premium pricing, because for many drugmakers, manufacturing quality isn’t a place to optimize for the lowest bid.

X. Bull Case, Bear Case, and Key Investor Considerations

Bull Case

The bull case is a set of tailwinds that reinforce each other.

Start with the obvious: the drug pipeline is tilting toward biologics. More large-molecule medicines means more demand for the kind of specialized, regulated manufacturing that only a handful of players can do at scale.

Layer on the industry’s capital allocation trend. More pharma companies want to keep their cash aimed at discovery and clinical development, not tied up in steel, cleanrooms, and validation protocols. That pushes work to CDMOs. And when demand spikes, capacity becomes the scarce resource—exactly where Samsung has chosen to compete by building ahead of the market.

That’s the backdrop for why Samsung Biologics stood out with more than 20% revenue growth in 2024, and why it guided to more than 20% growth again in 2025.

Then there’s the geopolitical kicker. The Biosecure Act could be a real windfall. If U.S. restrictions meaningfully limit work with Chinese CDMOs like WuXi Biologics and WuXi AppTec, global programs don’t disappear—they reroute. Samsung is one of the few scaled alternatives, and the Rockville, Maryland acquisition strengthens that positioning by giving Samsung a way to serve U.S.-based and U.S. government-adjacent programs from American soil.

Samsung also pointed to immediate commercial momentum around the U.S. move. Alongside the GSK facility acquisition, the company announced $828 million across three orders from pharmaceutical makers in Europe. That helped push total orders to 6.8 trillion won so far this year, up 26.1% versus the total for 2024.

Bear Case

The bear case is basically the flip side of the same strategy that made Samsung formidable.

First, capital intensity. This is a business where you keep spending billions before you’re sure the demand will show up. If capacity growth gets ahead of market needs, utilization drops—and when utilization drops, margins tend to follow.

Second, customer concentration. A CDMO can be “diversified” on paper and still be economically dependent on a handful of mega-clients and a handful of flagship programs. Losing or downsizing even one can sting.

Third, execution risk. Samsung’s advantage is speed and scale, but every new plant and new modality adds complexity. Construction delays, tech transfer hiccups, or—worst case—a quality failure can do damage that no amount of capacity can offset.

Geopolitics cuts both ways, too. Biosecure might steer work away from Chinese competitors, but escalating U.S.-China tensions can also scramble global pharma supply chains in unpredictable ways. And while Samsung’s Korea-centric manufacturing base is currently a strength in tariff discussions, it still leaves the company exposed to shifts in trade policy.

Finally, governance. The accounting controversy may be legally resolved, but it highlighted the risks of operating inside a chaebol: complex ownership structures, cross-currents from group-level priorities, and the perception of governance opacity. In the ruling, the judge said that even though Samsung Biologics’ accounting practices involved “inappropriate acts” such as document manipulation, the outcomes reflected financial realities and were based on rational reasons and processes. Investors still have to decide how much ongoing governance risk to price in.

Key Investor Considerations

Myth vs. Reality: Consensus Narratives Fact-Checked

Myth: Samsung Biologics is simply riding COVID tailwinds that will fade. Reality: COVID accelerated growth, but the durability shows up in what came after. The three $1 billion-plus contracts signed in late 2024 were long-term commercial manufacturing deals that had nothing to do with pandemic response.

Myth: Chinese CDMOs will remain formidable competitors indefinitely. Reality: The Biosecure Act, and the broader trend of supply-chain diversification away from China, could create persistent structural headwinds for WuXi entities—regardless of which specific companies end up formally designated. That dynamic benefits Korean and European alternatives.

Myth: Samsung Biologics’ margins will inevitably compress as it adds capacity faster than demand grows. Reality: In 2024, operating margin stayed strong at roughly 29%, suggesting pricing power and operating discipline held even as the company expanded.

Key Performance Indicators to Track

If you want a simple dashboard for Samsung Biologics, two metrics do most of the work:

-

Contract value and backlog momentum: Cumulative contracted value is the clearest window into future revenue. The pace of new contract signings shows whether Samsung is gaining share and whether demand is keeping up with expansion. In 2024, contract value grew more than 35% year over year—strong evidence of continued demand.

-

Capacity utilization: As Plant 5 and subsequent expansion come online, utilization will tell you whether supply is outpacing demand. High utilization—often thought of as 80% or above—supports pricing power and margin stability. A sustained drop would be the clearest signal that the cycle has turned toward oversupply.

Regulatory and Legal Overhangs

Samsung’s lawyers said the Supreme Court upheld earlier rulings acquitting Lee, confirming that “the merger of Samsung C&T and the accounting treatment of Samsung Biologics were lawful.”

The July 2025 Supreme Court ruling cleared the major legal overhang from the accounting controversy. But investors still have a few moving pieces to monitor closely: - How the Biosecure Act is implemented, and what it means for Chinese competitors - U.S. tariff policy and broader trade posture toward pharma manufacturing - Korea’s regulatory environment as Samsung continues scaling new plants and new modalities

XI. Conclusion: What Samsung Biologics Reveals About the Future of Biomanufacturing

Samsung Biologics is a company story, but it’s also a manufacturing story—and that’s the point. In an industry that loves to celebrate discovery, Samsung’s rise is a reminder that the unglamorous parts of biotech often decide who wins. The ability to build compliant facilities quickly, transfer complex processes without drama, and then run them at scale—month after month, inspection after inspection—isn’t a support function. It’s a durable advantage.

In just fourteen years, Samsung Biologics turned what looked like a bold corporate experiment into proof that Samsung Group’s thesis could travel: the same instincts that helped it conquer semiconductors—patient capital, aggressive capacity bets, and relentless operational improvement—could translate to biologics. Samsung didn’t try to out-invent the industry. It tried to out-execute it, pairing Western-grade quality expectations with the speed and manufacturing discipline the group is known for.

That evolution is still underway. Samsung Biologics kept widening its scope to meet where the market is going, expanding beyond traditional monoclonal antibodies into modalities like ADCs and mRNA, while insisting it can do that without compromising on quality or supply stability.

Now the company is stepping into a new phase where the constraints aren’t just technical—they’re geographic and political. The planned Rockville, Maryland acquisition is an acknowledgment that global drugmakers want options across jurisdictions, not just the best plant in one country. Full ownership of Samsung Bioepis, meanwhile, gives Samsung a clearer path to capture more value from the biosimilar market it helped scale, rather than only collecting manufacturing fees.

So the forward-looking question is the same one that’s been hanging over Samsung Biologics since day one: can it keep executing as the ambition expands? Can it keep compressing construction timelines, maintaining top-tier quality across a larger footprint, and winning programs in a market that’s growing fast—but also getting more competitive?

The next decade of biomanufacturing will be shaped by geopolitics, new technologies, and the continued shift of the pharma pipeline toward biologics. Samsung Biologics—born inside a conglomerate that started with dried fish trading, sharpened by decades of industrial competition, and now operating the world’s largest biotech manufacturing site—looks less like a company reacting to that future and more like one trying to build it.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music