Alteogen: Korea's David That Beat Pharma's Goliath

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

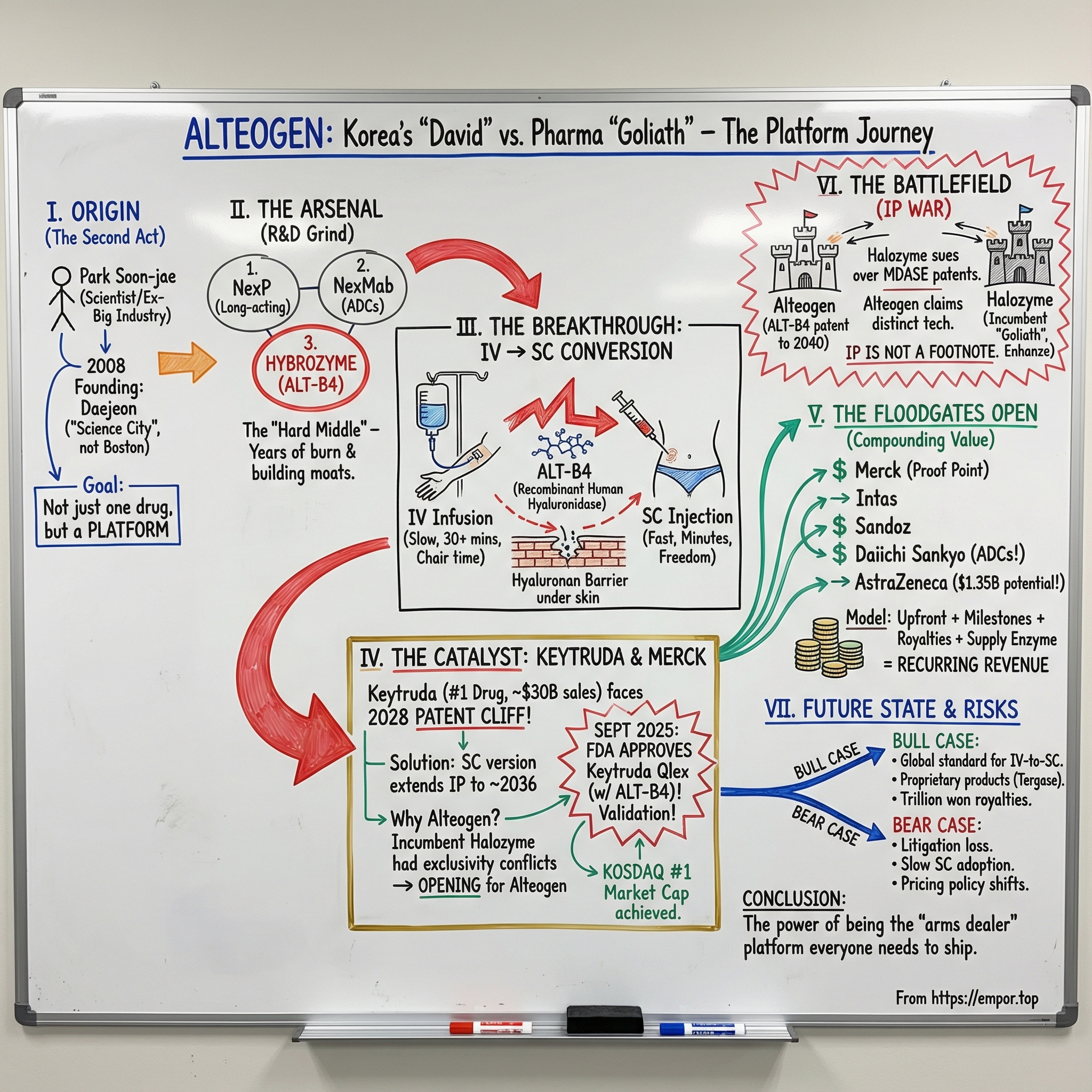

Picture this: it’s 2008. Lehman Brothers has just collapsed, credit markets are freezing, and starting any new company sounds borderline irresponsible. Now zoom in on a scientist in his mid-fifties—decades of research behind him, including time at MIT and senior roles inside Korea’s biggest industrial organizations—deciding that this is the moment to launch a biotech.

Not in Boston. Not in San Diego. In Daejeon—about 160 kilometers south of Seoul—Korea’s “science city,” and a place most Western biotech executives couldn’t point to on a map.

That scientist is Park Soon-jae. And seventeen years later, he’s not just still standing—he’s at the helm of the biggest company on Korea’s KOSDAQ exchange by market capitalization. By December 2024, Alteogen had reached the largest market cap on KOSDAQ. During the run-up in 2024, Park became a billionaire in U.S. dollar terms. In 2025, Forbes estimated his net worth at US$3 billion, making him the 23rd richest person in South Korea.

So here’s the deceptively simple question that powers today’s story: how did a tiny Korean biotech—roughly 150 employees—become the indispensable enabler of the next chapter of the world’s best-selling drug?

That drug is Keytruda. In 2023, it took the crown as the world’s bestselling medicine. In 2024, sales surged again—up 18% to $29.5 billion—pushing it past AbbVie’s Humira as the most commercially successful drug in any therapeutic area.

But Keytruda has a looming problem. Merck’s patent protection begins to run out in 2028, and investors know what that means: when the cliff arrives, the fall can be brutal.

This is where Alteogen enters—with a technology that sounds almost mundane until you realize what it unlocks. Alteogen developed ALT-B4, a recombinant human hyaluronidase enzyme that helps convert drugs typically given through half-hour IV infusions into quick subcutaneous injections. On September 19, 2025, the FDA approved pembrolizumab and berahyaluronidase alfa-pmph—Keytruda Qlex—for subcutaneous injection. And that “berahyaluronidase alfa” in the formulation? That’s Alteogen’s ALT-B4.

From here, we’re going to pull on a few threads at once. We’ll look at how platform technologies build moats that single-drug companies can’t. How a David can beat an entrenched American incumbent—Halozyme Therapeutics—when patent timelines and exclusivity deals create just the right openings. And how the most valuable position in pharma isn’t always inventing the headline drug—it’s becoming the company Big Pharma can’t ship without.

Because the deeper themes in Alteogen’s story are bigger than Alteogen: Korea’s rise in global biotech, the IV-to-subcutaneous conversion wave reshaping oncology care, intellectual property as a battlefield—not a footnote—and the compounding power of a platform business that can win again and again through partnerships.

II. Founding Story: A Scientist's Second Act

Before there was Alteogen, there was Park Soon-jae’s long apprenticeship inside the institutions that built modern Korean science—plus a detour through the American research machine.

Park was born on December 22, 1954, in Gunsan, in North Jeolla Province. He went through Seoul High School, earned a biochemistry degree at Yonsei University, then left for the U.S. for graduate training—picking up both a master’s and a Ph.D. in chemistry at Purdue University.

On paper, it’s the classic path of an elite Korean scientist: top schools at home, a doctorate in America. But Park didn’t stay in the lane of a purely academic career. After time as a researcher at MIT, he returned to Korea and moved through a sequence of roles that gave him something most founders never get: a panoramic view of how Korean industry actually works. He joined Lucky Biotech Research Institute (now LG Chem Research Institute) as a senior researcher. He later moved to Hanwha Petrochemical to lead its bio development division and the Dream Pharma project. Then he became CEO of Binex. And in 2008—at an age when many executives are thinking about wrapping up—he started over, founding Alteogen with his wife, Chung Hye-shin, a professor at Hannam University.

Park and Chung weren’t just spouses; they were intellectual partners. Both earned doctorates from Purdue and both worked as researchers at MIT. That shared foundation mattered when the early days inevitably demanded a founder who could sell a vision and a co-founder who could keep the science moving. Chung co-founded Alteogen and served as its chief scientific officer.

And then there’s the decision that signals what kind of company Park intended to build: where to place it.

Alteogen headquartered in Daejeon—Korea’s “science city,” in the heart of Daedeok Innopolis, the country’s dense cluster of government-funded institutes, public research organizations, and corporate R&D centers. Nature has singled out Daejeon as one of the global science cities to watch, and in Korea, that reputation isn’t marketing. It’s infrastructure—talent, labs, and the quiet flywheel of research institutions feeding companies that can commercialize.

From the beginning, Alteogen wasn’t designed as a one-drug moonshot. It was designed as a platform shop. The company developed three proprietary technology families: NexP for long-acting biobetters, NexMab for site-specific conjugated ADCs, and Hybrozyme for novel recombinant human hyaluronidase—technology that would later power ALT-B4.

That focus wasn’t accidental. Park’s management principle was simple: if you can’t be world-first, you have to be unmistakably differentiated. He would go on to achieve a milestone that no Korean biotech had pulled off before—applying a domestically developed platform to the world’s top-selling pharmaceutical product.

It’s also a bet about how value compounds in pharma. A single drug can be transformative, but it’s also fragile—patent cliffs, competition, changing standards of care. A platform, if it’s good enough, can get licensed again and again. Park was essentially choosing the arms-dealer position: become the company others need in order to ship.

Later, the family component became part of the investor narrative. Park held a 19.2% stake as of June 2024. Chung, a co-founder and former chief scientific officer, left the company in September 2023 and controversially sold much of her stake in early 2024. Park told stockholders he would not sell his own shares.

That mattered because it signaled how Park wanted the market to view him: not as someone extracting value on the way up, but as someone staying planted for the long game.

III. Building the Platform Arsenal (2008-2018): The Long Road

For the next decade, Alteogen lived in the hard middle of biotech—the place where the science might be world-class, but the business still feels like a long experiment. It was building technologies that could become enormously valuable, but not quickly. And it was doing it with the classic platform-company problem: years of R&D before the first real proof that anyone outside the building actually needs what you’ve built.

Park’s answer was to build three pillars in parallel—three shots on goal, each designed to be a reusable engine rather than a one-time product.

The first was NexP™ fusion technology. Protein drugs often work brilliantly, but they’re cleared from the body fast, forcing patients into frequent dosing schedules that are inconvenient at best and noncompliant at worst. NexP™ tackles that by fusing proteins and peptides in a way that extends how long they remain active in the body. Alteogen used it to develop long-acting versions of therapies like human growth hormone, exenatide for diabetes, and Factor VIIa for hemophilia.

The second pillar was NexMab™ ADC technology—Alteogen’s entry into antibody-drug conjugates, one of the most competitive frontiers in oncology. The pitch of ADCs is simple: deliver a potent payload directly to cancer cells and limit collateral damage. Alteogen’s NexMab™ platform was designed for targeted cancer therapy with the goal of lowering side effects while improving efficacy, and it supported programs in indications like breast and gastric cancer and ovarian cancer.

But the third pillar—Hybrozyme™—was the one that would eventually bend the company’s trajectory. Hybrozyme is Alteogen’s platform for a recombinant human hyaluronidase enzyme, designed to improve the absorption and dispersion of biologic drugs delivered by subcutaneous injection. The company’s novel hyaluronidase showed improved enzymatic activity and thermal stability—technical details that sound small until you realize they’re exactly the kinds of edges that determine whether a platform becomes a standard.

While all of that platform work was underway, Alteogen was also building a second capability set: biosimilars. Over time, it developed its own high-expression cell lines, improved upstream and downstream processes, and optimized analytical methods for monoclonal antibody biosimilars—including work connected to Herceptin as it prepared for phase 3.

Partnerships helped keep the flywheel turning and signaled that Alteogen’s work was legible to the outside world. The company formed a strategic alliance with Kissei Pharmaceutical to develop ALT-L9, a biosimilar of Eylea (aflibercept), and with Cristalia to develop ALT-L2, a biosimilar of Herceptin (trastuzumab).

Still, the existential question hung over everything: how do you survive long enough for platform science to matter? In 2014, Alteogen listed on KOSDAQ. The IPO gave it access to capital markets—oxygen for a company whose main output, for years, was knowledge and IP.

This is the part of the story that tends to get compressed into a sentence in hindsight. But in real time, it’s the whole game: years of uncertainty, steady cash burn, and no guarantee the world will care. Alteogen was betting that patient capital—and patient execution—would eventually turn Daejeon lab work into global commercial demand.

And if it worked, the payoff wouldn’t look like one drug. It would look like repetition: a platform that could be licensed again and again, compounding in a way a single-product biotech simply can’t.

IV. Inflection Point #1: ALT-B4 Development & The Hybrozyme Breakthrough (2018-2019)

The breakthrough that changed Alteogen’s trajectory starts with a piece of biology most people never think about.

Under your skin, the body’s connective tissue is reinforced by hyaluronan—a kind of molecular scaffolding. It’s one reason you can’t just push large volumes of a biologic drug into the subcutaneous space and expect it to spread and absorb. Hyaluronidase enzymes solve that problem by temporarily breaking down hyaluronan, creating a short-lived window where fluid can move through the extracellular matrix.

That’s the trick behind ALT-B4.

Developed using Alteogen’s Hybrozyme technology, ALT-B4 is a novel recombinant human hyaluronidase designed to enable large-volume subcutaneous administration for biologics that have traditionally required intravenous delivery. Mechanistically, it works by temporarily hydrolyzing hyaluronic acid in the extracellular matrix—simple to describe, but transformational in what it makes possible.

Because the real story here isn’t the enzyme. It’s the patient experience.

IV infusions mean infusion centers, IV line placement, and long waits—often around 30 minutes or more for common oncology regimens, before you even count check-in, chair time, and monitoring. Subcutaneous injections can be administered in minutes. For patients living their lives between appointments, that difference isn’t incremental. It’s freedom.

Of course, Alteogen wasn’t first to see the opportunity. Halozyme Therapeutics in San Diego had already built a major business around its Enhanze platform, pairing its recombinant human PH20 enzyme with deep know-how in converting IV drugs into high-volume subcutaneous formulations. Enhanze was proven, validated, and already embedded across Big Pharma.

So why would anyone take a bet on a smaller, newer Korean platform?

In the years that followed, a few differences became central in negotiations. Alteogen said ALT-B4 offered higher enzymatic activity, improved thermal stability, and lower immunogenicity versus existing options. But the more strategic wedge was commercial, not scientific: Halozyme had signed exclusive licenses around certain therapeutic targets, and those exclusivity deals left open lanes for a competitor that could deliver comparable performance.

That opening led to Alteogen’s first major licensing deal in December 2019—announced at the time only as an agreement with a “top 10 global pharmaceutical company,” and described as its first global contract for ALT-B4. The terms made the point: a $13 million upfront payment, with additional development, regulatory, and sales milestones that could total up to $1.37 billion. The partner’s identity stayed confidential then, but it was later revealed to be Merck.

The significance went way beyond the numbers. This was a top-tier pharmaceutical company effectively saying: we’ve looked at the incumbent, we’ve looked at the alternatives, and we’re willing to build on this new platform from a Korean biotech most of the world still didn’t know.

For a platform company, that first deal is the moment the story stops being theoretical. It becomes a proof point other partners can reference. It funds the unglamorous work—R&D, process development, manufacturing scale-up—that turns a technology into something repeatable. And it changes the posture of every future conversation from “convince us this could work” to “show us how fast we can move.”

Alteogen had cleared the first bar.

Now it needed to prove it wasn’t a one-off.

V. Inflection Point #2: The Merck-Keytruda Deal—Betting on the World's Biggest Drug

To understand why Merck chose Alteogen, you have to understand the strange, precarious position Keytruda put Merck in.

Keytruda wasn’t just a blockbuster. It became the blockbuster—a drug so successful it turned into a load-bearing pillar for the entire company. By 2023 it represented more than 41% of Merck’s total sales, and that concentration only grew more glaring as Keytruda kept expanding into new indications.

Then came the clock.

The IV version of Keytruda is slated to lose patent protection in 2028. And when your biggest product is on a timer, you don’t get to be casual about what comes next. Merck had two big levers: keep building new drugs to diversify, and find a way to give Keytruda a second life.

A subcutaneous formulation offered exactly that. Not because it changed what Keytruda does—but because it changed how Keytruda is delivered. A new formulation that incorporates novel technology can come with its own patent protection. If Merck could develop a subcutaneous Keytruda and secure the related patents, the protection window could extend well beyond the 2028 cliff—potentially out to 2036.

So Merck pushed, hard, for SC Keytruda. Which immediately raises the obvious question: why bet on Alteogen, instead of Halozyme, the established leader in IV-to-SC conversion?

Because Halozyme’s dominance had a catch. Over time, it had signed exclusive licensing deals around specific biological targets. And those exclusivity arrangements created dead zones—situations where a pharma company might want Halozyme’s platform, but couldn’t get it for a particular mechanism. At the same time, Halozyme faced another reality: patents around its Enhanze recombinant human hyaluronidase technology were beginning to expire. It responded with Mdase, a newer technology aimed at expanding its partner base. But exclusivity still mattered, and for Merck, the constraints were real.

That’s the opening Alteogen squeezed through.

The relationship started with the December 2019 agreement—Alteogen’s “top 10 pharma” deal that was later revealed to be Merck—structured as a worldwide license with a $13 million upfront payment and the potential for much larger milestones.

Then the deal deepened. Alteogen later announced an amendment to its agreement with MSD (Merck & Co. in the U.S. and Canada) that converted the relationship into something far more pointed: exclusive worldwide rights to use ALT-B4 specifically for subcutaneous versions within the Keytruda (pembrolizumab) product line.

The revised economics reflected that shift. Alteogen received a $20 million down payment, with milestones tied to approval, patent extension, and cumulative net sales that could total up to $432 million—bringing the amended deal’s total potential value to $452 million.

And Merck didn’t just paper this up and hope. The clinical program moved quickly.

In November 2024, detailed results in metastatic non-small cell lung cancer showed subcutaneous Keytruda matching the IV form on key pharmacokinetic endpoints—exactly what you need to prove when you’re changing the route of administration for a drug that’s already a standard of care.

Those results came from Study MK-3475A-D77 (NCT05722015), a randomized, multicenter, open-label, active-controlled trial in treatment-naïve metastatic NSCLC. Patients were randomized 2:1 to receive either Keytruda Qlex subcutaneously every six weeks plus platinum doublet chemotherapy, or IV pembrolizumab every six weeks plus the same chemotherapy. In total, 377 patients were enrolled.

The confirmed objective response rate was 45% in the subcutaneous Keytruda Qlex arm versus 42% in the IV arm, and there were no notable differences observed in progression-free survival or overall survival between the groups.

Then, in September 2025, the story reached its logical endpoint: FDA approval.

Merck announced that the U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved KEYTRUDA QLEX (pembrolizumab and berahyaluronidase alfa-pmph) injection for subcutaneous administration in adults across most solid tumor indications of KEYTRUDA. Berahyaluronidase alfa—the enabling enzyme inside the formulation—is a variant of human hyaluronidase developed and manufactured by Alteogen.

In total, Keytruda Qlex was approved for 38 cancers, and Merck expected the product to be available in the U.S. later that month.

The stakes on the commercial side were just as large. If Keytruda Qlex successfully penetrates the market, Alteogen is expected to generate annual royalty income exceeding 1 trillion won. Merck expected to transition roughly 30% to 40% of Keytruda usage to the subcutaneous version over about 18 months to two years.

For Alteogen, it was the cleanest possible validation: the world’s best-selling drug now depended on a delivery technology engineered in Daejeon.

VI. Inflection Point #3: The Floodgates Open—Deal After Deal (2020-2025)

Merck was the proof point. Once a top-tier pharma company had effectively put ALT-B4 on the critical path of its biggest franchise, the conversation with everyone else changed. Alteogen wasn’t pitching a clever enzyme anymore. It was offering a validated way to turn slow, resource-heavy IV infusions into fast subcutaneous injections—without handing over the whole factory.

What followed was a run of partnerships that steadily positioned ALT-B4 as the most credible alternative to Halozyme’s Enhanze.

Intas Pharmaceuticals (January 2021)

In January 2021, Alteogen signed an exclusive license agreement with Intas Pharmaceuticals to use ALT-B4 to develop and commercialize two products. Alteogen received an initial payment of $6 million, with additional development, regulatory, and sales milestones that could total up to $109 million.

The ongoing economics were the real point: tiered royalties ranging from mid-single digits to low double-digits on product sales. And importantly, Alteogen wasn’t just handing over instructions and walking away—it would be responsible for regulatory development and the commercial supply of ALT-B4 to Intas.

Sandoz (December 2022)

In December 2022, Alteogen announced it had signed its fourth technology export contract since developing ALT-B4 in 2018—this time with Swiss biosimilar leader Sandoz.

Sandoz planned to apply ALT-B4 to one product first, with the option to expand to two additional products later. Alteogen would manufacture and supply the hyaluronidase, while providing the underlying source technology. The total contract value, including upfront and milestone payments, was $145 million.

Daiichi Sankyo (November 2024)

By November 2024, the scope of what ALT-B4 could be used for had expanded again—this time into antibody-drug conjugates, one of the most important categories in modern oncology.

Alteogen and Daiichi Sankyo struck a deal to develop a subcutaneous formulation of Enhertu using ALT-B4. Daiichi agreed to pay $20 million upfront, with development and commercial milestones that could reach another $280 million, plus royalties tied to sales. The agreement was conditional and could vary depending on clinical outcomes and regulatory approval.

The strategic significance was clear: Enhertu is one of the most commercially successful ADCs ever developed, created through Daiichi Sankyo’s partnership with AstraZeneca. If a high-impact ADC could be moved under the skin, ALT-B4 wouldn’t just be an IV-to-SC solution for conventional antibodies—it would be a platform that could follow oncology’s next wave.

AstraZeneca (March 2025)

Then came the deal that made it impossible to ignore what was happening.

In March 2025, AstraZeneca and Alteogen entered into an exclusive license agreement for ALT-B4, giving AstraZeneca worldwide rights to use the enzyme to develop and commercialize subcutaneous formulations of several oncology assets. Alteogen would provide both clinical and commercial supply of ALT-B4.

Alteogen disclosed two separate agreements with AstraZeneca totaling $1.35 billion in potential value. One included a $25 million upfront payment and up to $725 million in milestones; the other included $20 million upfront and up to $580 million in milestones. Together, they delivered Alteogen a combined $45 million upfront payment—its largest to date. Alteogen later said it set a new record in the first quarter of 2025, fueled by that AstraZeneca upfront and a surge in ALT-B4 product sales.

Across these deals, the structure was consistent—and it’s the structure that makes a platform company so powerful. Alteogen kept control of the hard-to-replicate part: manufacturing and supplying ALT-B4. Partners took on the work of developing and commercializing their drug products. The result was a layered revenue model: upfront payments, milestones across development and approvals, sales milestones, and royalties.

And every new logo on the partner list didn’t just add revenue. It lowered the friction for the next deal. Once enough serious players buy into a platform, it starts to sell itself.

VII. The Halozyme Patent War: IP as Battlefield

Success didn’t just attract partners. It attracted a response from the incumbent.

As Alteogen’s technology gained real commercial momentum, Halozyme escalated from warnings to litigation—aiming straight at Merck and its subcutaneous version of Keytruda, which uses Alteogen’s enzyme.

Halozyme, the San Diego drug delivery specialist behind the rival Enhanze platform, argued that ALT-B4—if used in a commercial product—would infringe its newer MDASE (Modified Dermal Absorption Enhancing) portfolio of modified hyaluronidases. In April 2025, Halozyme filed suit in the U.S. District Court for the District of New Jersey, alleging Merck’s subcutaneous Keytruda formulation violated 15 patents in that MDASE patent family.

Merck pushed back on both the science and the legal theory. It argued that ALT-B4 was independently developed by Alteogen, and that the enzyme’s sequence isn’t disclosed in any Halozyme patent. Merck also asked the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office to review seven of the MDASE patents. But that administrative challenge is separate from the New Jersey case—and it doesn’t automatically make the lawsuit go away, since Halozyme’s complaint alleges infringement across a broader set of patents.

Underneath the legal filings is a very specific technical fight about what Halozyme actually owns.

Enhanze is based on the recombinant human hyaluronidase PH20 enzyme. As Halozyme studied PH20, its scientists created a library of more than 6,700 proteins with modified amino acid chains. That work fed into the MDASE patent portfolio starting in 2016. Halozyme’s argument is not that ALT-B4 is literally one of those proteins—it isn’t—but that the kinds of amino acid modifications used in Alteogen’s engineered enzyme fall within the scope of those 15 patents.

Alteogen responded fast, and sharply. Within hours of the lawsuit, it issued a statement insisting ALT-B4 is both scientifically and legally distinct, and said it had already run a comprehensive analysis of the MDASE patents. Alteogen added that its conclusions were largely consistent with Merck’s post-grant review filings—and that it believed there was a high likelihood Halozyme’s MDASE patents would be invalidated.

The timelines matter here, too. Patent protection for ALT-B4 is expected to run until 2040, while Halozyme’s MDASE patents run until 2034 in the U.S. And unlike Enhanze—which is typically licensed as a specific hyaluronidase protein—MDASE is framed as a broader group of patents.

Meanwhile, partners weren’t blind to the risk. Alteogen said its licensing partners had done their own diligence, including full IP audits, and that the risk was understood and priced in.

What makes this more than an ordinary biotech lawsuit is what’s sitting on the other side of the “subcutaneous” label. Keytruda—still primarily an IV infusion—generated $29.5 billion in 2024, representing 46% of Merck’s total revenue. In the first quarter of 2025, it brought in $7.2 billion, up 18% year over year.

Halozyme is seeking damages and, more importantly, an injunction that could block the commercialization of subcutaneous Keytruda. In the complaint, Chief Legal Officer Mark Snyder said Merck “has long been aware of Halozyme’s patents” and proceeded anyway.

For investors, this is the cloud hanging over the cleanest possible product story. A loss for Merck could mean settlement payments, new licensing costs, or—at the outer edge—an attempt to halt the subcutaneous formulation. Industry observers have generally viewed a negotiated settlement as the most likely endpoint: commercialization continues, and Halozyme is compensated for alleged infringement.

But in the meantime, the lawsuit makes the point every platform company eventually learns: in biopharma, IP isn’t a footnote. It’s the battlefield.

VIII. Beyond Licensing: Building a Commercial Company

ALT-B4 made Alteogen famous. But inside the company, the goal was always bigger than becoming a one-platform licensing machine. Licensing can generate enormous value, but it also leaves you structurally dependent on other companies’ timelines, priorities, and launch execution. So in parallel with the partner deal flow, Alteogen kept pushing toward something harder: becoming a commercial-stage company with products of its own.

Tergase Approval—The First Proprietary Product

On July 8, 2024, Alteogen announced that Korea’s Ministry of Food and Drug Safety (MFDS) had approved its New Drug Application for Tergase (recombinant hyaluronidase). Tergase (development code name ALT-BB4) is a stand-alone recombinant hyaluronidase derived from human hyaluronidase PH20, and it’s designed to act as a tissue permeability modifier—an adjuvant that increases the dispersion and absorption of other injected drugs and topical anesthetics when administered by subcutaneous or intradermal injection.

Like ALT-B4, Tergase comes out of Alteogen’s Hybrozyme Technology. But the commercial logic is different. Rather than being bundled into a partner’s blockbuster, Tergase is meant to stand on its own in routine clinical use.

The initial application is dermal filler removal, but the product’s use cases extend beyond aesthetics. Alteogen also positioned it for roles like supporting local anesthesia in eye surgeries and helping in orthopedic pain management. And it leaned into a practical point that matters in medicine more than investors sometimes appreciate: purity and immunogenicity. Alteogen emphasized that Tergase is highly purified—over 99% purity—and that this profile can be advantageous compared to animal-derived hyaluronidases, which often come with lower purity and higher immunogenicity.

This is where Alteogen’s platform strategy shows its full shape. Hyaluronidase isn’t just a licensing ingredient; it can also be a product category. The Korean hyaluronidase market has been estimated at roughly 1 trillion won, spanning use in areas like orthopedics, neurosurgery, anesthesiology, and rehabilitation medicine—often to manage pain and swelling or to speed drug absorption.

Biosimilar Progress

At the same time, Alteogen kept advancing its biosimilar engine—another route from “platform R&D” to “products that ship.”

The company announced that the European Commission granted marketing authorization for EYLUXVI (code name: ALT-L9), an Eylea biosimilar co-developed by its subsidiary, Alteogen Biologics. With that authorization, EYLUXVI was approved across Europe for multiple retinal diseases, including wet age-related macular degeneration, macular oedema secondary to retinal vein occlusion, diabetic macular oedema, and myopic choroidal neovascularization.

EYLUXVI became the second biosimilar approved for Alteogen, following the launch of the Herceptin biosimilar in China through its partner Qilu Pharmaceutical.

As CEO Soon Jae Park put it, “EYLUXVI is the first biosimilar product developed by Alteogen through independent in-house research, followed by global clinical development in collaboration with our subsidiary Alteogen Biologics, and has ultimately secured regulatory approval.” He also highlighted what that approval represents beyond the product itself: “Alteogen has expanded its capabilities not only through R&D, but also by gaining valuable experience with the European regulatory approval process.”

Corporate Restructuring

Becoming commercial doesn’t just mean getting approvals. It means building the machinery to sell, distribute, and support products in the real world.

To prepare, Alteogen reorganized. It completed a merger between two subsidiaries—Altos Biologics Inc. and Alteogen Healthcare Inc.—and rebranded the combined entity as Alteogen Biologics Inc. The idea was straightforward: combine Alteogen Healthcare’s pharmaceutical distribution, sales, and marketing strengths with Altos Biologics’ clinical and new drug development capabilities.

That shift is the classic second act challenge in biotech. R&D organizations win through experiments, iteration, and patience. Commercial organizations win through execution: sales force management, distribution logistics, regulatory compliance across markets, and long-term customer relationships.

Alteogen had already proven it could build world-class technology. The next question was whether it could build a world-class business around it.

IX. Strategic Analysis: Competitive Position and Investment Considerations

Porter’s Five Forces is a useful lens here, not because it predicts who wins a court case, but because it explains why Alteogen went from “interesting Korean biotech” to “phone rings when Big Pharma needs an IV-to-SC solution.”

Porter's Five Forces Analysis

Threat of New Entrants: LOW

On the surface, a hyaluronidase platform looks like a narrow niche. In reality, it’s a moat built out of time.

To compete head-on, a new entrant would need to engineer a novel enzyme, generate convincing clinical evidence on safety and performance, and then build commercial-scale manufacturing that regulators and partners will actually trust. None of that is fast. And it’s not cheap.

Even if ALT-B4’s patent protection is expected to run until 2040, the real barrier isn’t just the patent term. It’s the accumulated know-how: process development, quality systems, regulatory experience, and a partner network that has already bet real programs on the platform.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers: LOW

In Alteogen’s core business, Alteogen is the supplier.

It doesn’t just license the idea of ALT-B4; it retains responsibility for manufacturing and supplying the enzyme. That puts the company in control of a critical input inside partner products, which is a structurally strong position to be in.

Bargaining Power of Buyers: MODERATE

Buyers—pharmaceutical companies—do have options. The main one is Halozyme’s Enhanze.

But “have an option” isn’t the same as “can use it.” Halozyme’s historical exclusivity deals have blocked it from partnering in certain target areas, and Enhanze’s patent protection has been moving toward expiration—cited as expiring in 2024 in Europe and 2027 in the U.S. Those constraints are exactly the kinds of market imperfections a challenger can build a business around.

That’s where Alteogen has been strongest: stepping in when Halozyme’s exclusivity has already allocated the lane to someone else (including situations like Bristol Myers Squibb and PD-1 inhibitors), or when partners care about a longer patent runway and a fresh freedom-to-operate story.

Threat of Substitutes: MODERATE

There are other ways to try to improve drug delivery: alternative subcutaneous formulation strategies, depot approaches, and longer-term efforts to make biologics oral.

But for high-volume subcutaneous administration of biologics, hyaluronidase-enabled delivery remains the leading, most established solution. Substitutes exist, but not many that are as plug-and-play for the same use case.

Competitive Rivalry: HIGH

This is the most obvious one. Alteogen’s rise pulled it into direct conflict with Halozyme, and that rivalry has now turned into active litigation around the Keytruda subcutaneous program.

Both companies are fighting over the same prize: becoming the default platform partner across oncology and beyond. The legal outcomes won’t just determine damages or royalties—they’ll shape how comfortable future partners feel making long-term bets.

Hamilton Helmer's Seven Powers Assessment

Counter-Positioning: STRONG

Alteogen’s strategy makes sense as counter-positioning.

Halozyme built a very successful business on exclusive licensing. But exclusivity is a double-edged sword: it maximizes value in the deals you do sign, while creating hard “no’s” for other potential partners. Alteogen systematically exploited those gaps. And as Enhanze approached patent expiration, the urgency for alternatives increased—another tailwind for the challenger.

Scale Economies: MODERATE

There are benefits to manufacturing ALT-B4 at scale, but this isn’t a commodity business where scale alone decides everything.

In practice, partner trust, regulatory credibility, and execution in tech transfer and supply may matter more than who can produce the lowest-cost gram.

Switching Costs: HIGH

Once a partner has advanced an ALT-B4-enabled formulation through clinical trials and into regulatory review—or onto the market—switching becomes brutally expensive.

You’re not swapping a vendor. You’re potentially restarting development. That creates real lock-in, which is one reason these platform deals can be so valuable once established.

Network Effects: LIMITED

This isn’t a social network or a payments rail. Each licensing relationship largely stands on its own.

There is reputational spillover—each new partner makes the next deal easier—but partners don’t directly benefit because other companies use the same enzyme. So classic network effects are limited.

Cornered Resource: STRONG

Hybrozyme and ALT-B4 are the company’s cornered resource: proprietary technology, protected by patents, and hard to replicate in practice.

With patent protection extending to 2040, the legal moat is meaningful. The operational moat—manufacturing know-how and regulatory-grade execution—is what makes the resource truly hard to copy.

Key Performance Indicators to Monitor

If you’re tracking Alteogen as an ongoing business, three indicators matter more than headline deal values:

-

Partner milestone achievement rate: Milestones are how platform economics convert from “promising” to “paid.” A strong track record here signals that partners are moving programs forward—and that the platform is behaving as advertised.

-

Commercial royalty growth from launched products: Over time, royalties—not upfront checks—are what turn Alteogen into a compounding machine. Growth in royalty revenue is the cleanest signal that ALT-B4-enabled products are actually winning in the market.

-

New partnership announcements and deal values: New deals are not just incremental revenue opportunities; they’re confirmation that the platform is becoming a standard. The pace and quality of new partners will show whether Alteogen’s momentum is durable.

Material Risks

The most immediate risk is the Halozyme litigation. Alteogen and Merck have expressed confidence, but patent litigation is inherently uncertain. A bad outcome could mean damages, forced licensing, or injunctive relief that blocks product sales.

Then there’s concentration risk. The company’s narrative and economics are heavily tied to Keytruda Qlex. Alteogen has indicated that one successful pipeline can have an outsized financial impact, and it expects technology fee revenue to reach 1 trillion won by 2028 through accumulated partnerships and full-scale subcutaneous Keytruda sales. That upside cuts both ways: if Keytruda Qlex adoption disappoints, or timelines slip, the financial model feels it quickly.

Finally, there’s policy and pricing risk. In the U.S., CMS released revised draft guidance under the Inflation Reduction Act’s drug price negotiation framework, tightening criteria for fixed-dose combination therapies to be considered new drugs. If subcutaneous formulations aren’t treated as “new” drugs for pricing purposes, that could weaken the commercial incentive for partners to invest in IV-to-SC conversions—even when the patient experience improvement is real.

X. Bull Case and Bear Case

Bull Case

In the best version of this story, Alteogen doesn’t just ride the Keytruda moment. It uses it to become the default global platform for IV-to-subcutaneous conversion.

That bull case looks like this:

- Keytruda Qlex ramps quickly, with something like 40% to 50% of patients moving to the subcutaneous formulation within about three years

- More Big Pharma partners sign on—across not just oncology, but also other biologics-heavy areas like immunology and neurology

- The Halozyme dispute is resolved either in Alteogen and Merck’s favor, or via a settlement that doesn’t meaningfully disrupt commercialization

- Alteogen’s biosimilars gain real traction and meaningful market share in their respective categories

- Tergase expands beyond Korea into additional markets and use cases, turning Hybrozyme into a product business as well as a licensing platform

If those things happen, Alteogen could be pulling in annual royalties north of one trillion won by 2028—with additional growth as more ALT-B4-enabled products reach the market.

Bear Case

The bear case is simpler, and it centers on friction—legal, commercial, and regulatory.

It looks like this:

- Halozyme wins key points in the patent fight, leading to major damages and, in the worst case, restrictions that block or limit sales of subcutaneous Keytruda

- The shift from IV to subcutaneous happens slower than the market expects, whether due to physician habits, patient preferences, reimbursement mechanics, or hospital workflow

- CMS pricing rules end up treating subcutaneous formulations as essentially the same as the original IV product, reducing the financial payoff that drives partners to invest in conversion programs

- Halozyme successfully reasserts leadership with next-generation technology and a stronger licensing posture

- Broader sentiment turns against Korean biotech, compressing valuation multiples even if execution remains solid

In that world, Alteogen’s growth would slow materially—and today’s valuation would be hard to defend.

Base Case Assessment

Reality usually lands between the two.

ALT-B4 has already shown clinical usefulness and clear commercial demand, and Alteogen’s partner roster suggests the platform is real, not hypothetical. But the company will likely remain exposed to volatility from litigation, shifting regulatory interpretation, and the natural push-and-pull of competition in a category this valuable.

As of April 10, 2025, Alteogen’s market capitalization was about 18.52 trillion won, up roughly 80% over the prior year.

That price embeds big expectations. Whether it holds comes down to execution: how fast Keytruda Qlex converts, how many other programs reach the market behind it, and how cleanly Alteogen navigates the legal and policy noise along the way.

XI. Conclusion: The Platform Playbook

Alteogen’s story is a reminder that there’s more than one way to win in biotech. You can swing for the fences with a single drug and hope it becomes a franchise. Or you can do what Park Soon-jae set out to do from day one: build a platform—something good enough, defensible enough, and useful enough that many different drug companies will want to plug it into many different products, again and again.

That path is slower, and it’s not for the impatient. Alteogen spent roughly a decade building its technology pillars before the Merck relationship turned ALT-B4 from promising science into a global asset. It demanded real differentiation—science that wasn’t “close enough,” but clearly better on the dimensions that matter. And it demanded timing and positioning: understanding that market structure creates openings, like the one Merck faced when Halozyme’s exclusivity agreements made the incumbent platform unavailable in the lane Merck needed.

Park reached a milestone no Korean biotech had hit before: a domestically developed platform technology incorporated into the world’s top-selling drug. And he did it by sticking to a simple management rule—be world-first, or unmistakably different.

The strongest validation didn’t come from local hype. It came from the biggest pharmaceutical companies in the world deciding this was worth betting on—with contracts that, if fully realized, stretch into the billions.

The fight with Halozyme is still part of the story, and it won’t stay confined to press releases. It will play out in courtrooms, in patent offices, and in commercial adoption curves. The outcomes could materially shape both companies. But even with that uncertainty, Alteogen has already proven something that used to sound aspirational: a Korean biotech can compete—and win—at the highest tier of global pharma innovation.

A scientist’s second act in Daejeon became a critical ingredient in the next chapter of Keytruda. Not through luck, but through the slow compounding of technical capability, smart positioning against a powerful incumbent, and a clear understanding that platforms can create durable, repeatable value in a way single assets rarely can.

From here, the questions get practical. Can Alteogen navigate legal risk without losing momentum? Can it scale manufacturing and supply reliably as demand rises? Can it keep signing high-quality partners—and, more importantly, can those partners actually bring products to market? And can the company’s biosimilars and proprietary products add meaningful weight beyond ALT-B4?

Those are the questions that separate a hot biotech moment from an enduring platform company.

Alteogen has earned the right to answer them.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music