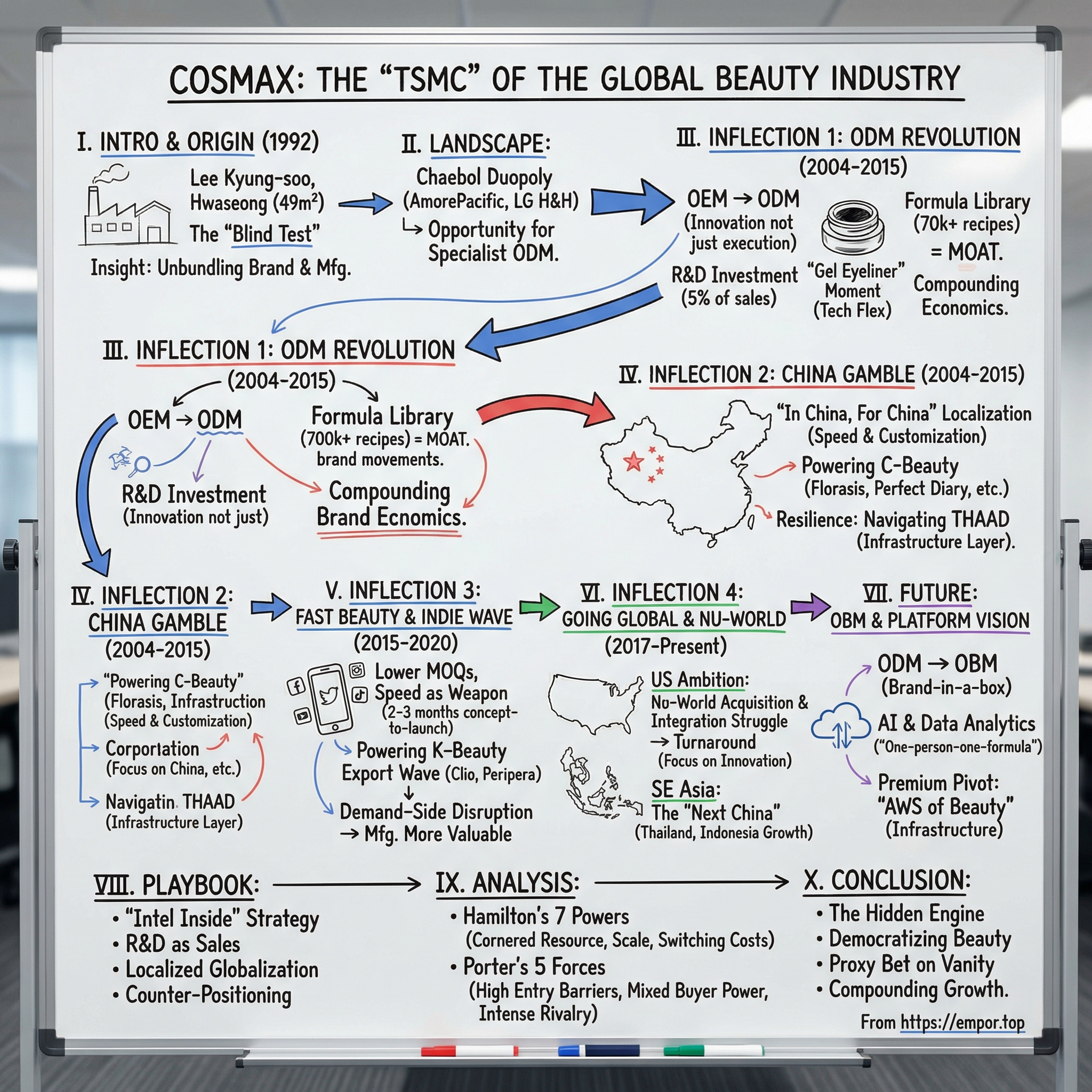

Cosmax: The "TSMC" of the Global Beauty Industry

I. Introduction & The "Blind Test"

Picture your vanity.

A sleek tube of YSL lipstick. A bottle of L'Oréal serum you grabbed at the drugstore. A little lineup of Korean skincare in the drawer—maybe Dr. Jart+ moisturizer, maybe a Peripera tint that went viral on TikTok. Different brands, different price points, different marketing worlds.

And yet there’s a very high probability those products share the same origin story: they were formulated by the same R&D teams and made on the same production lines in South Korea.

That company is Cosmax.

If you’ve never heard of it, that’s by design. Cosmax was founded in 1992 and grew into the world’s largest cosmetics ODM, supplying around 4,500 brands from factories across South Korea, China, the U.S., and Southeast Asia. It’s a picks-and-shovels business for beauty—except instead of selling equipment, Cosmax helps invent and manufacture the thing brands actually sell, then watches them put a logo on top and capture the margins.

The cleanest analogy is TSMC. Just as TSMC became the hidden engine behind Apple, NVIDIA, AMD, and pretty much every company that matters in modern computing—by doing a kind of manufacturing that even giants struggle to replicate—Cosmax became the hidden engine of the global beauty industry. It was also the first Korean cosmetics ODM to make serious inroads overseas, building an international footprint that made it a go-to partner for some of the world’s biggest cosmetics names.

But this isn’t just a manufacturing story. It’s a technology and platform story.

Over three decades, Cosmax changed the economics of beauty by dropping the barrier to entry from “you need your own factory” to something that looks a lot more like “you can start with a modest budget and a clear point of view.” With as little as $20,000, a new beauty entrepreneur could get a first run of product from a reputable manufacturer in just a few months. That shift helped ignite the indie beauty wave and supercharged the global spread of K-Beauty—an explosion that’s still reshaping what we buy, how fast trends move, and who gets to build the next breakout brand.

This is how one Korean scientist, starting in a tiny factory in the early 1990s, built an infrastructure layer for nearly everything you put on your face.

II. The Landscape & The Founder's Insight

Early 1990s Korea: The Chaebol Stranglehold

To understand why Cosmax mattered, you have to start with what the Korean cosmetics industry looked like before it existed.

In the early 1990s, Korean beauty was a duopoly. Two giants—AmorePacific and LG Household & Health Care—ran the whole stack. They owned the labs. They owned the factories. They owned the brands. They controlled the department store counters and distribution. If you wanted to sell cosmetics in Korea, you either were one of these conglomerates… or you tried to negotiate your way onto their shelves.

And the vertical integration wasn’t just about power. It was also about physics. Cosmetics required real chemistry, strict quality control, expensive equipment, and hard-won know-how around things like stability and shelf life. The prevailing belief was simple: only massive corporations could do this well. For everyone else, the barriers weren’t “high.” They were basically walls.

That was the orthodoxy. And like most orthodoxies, it looked permanent—right up until it wasn’t.

The Founder: Lee Kyung-soo

Enter Lee Kyung-soo.

In 1992, Lee was 46 years old and working as a marketing executive at Daewoong Pharmaceutical. He’d graduated from Seoul National University’s College of Pharmacy in 1970, and he’d spent two decades inside a company that understood what it meant to produce complex formulations at scale with pharmaceutical-grade discipline.

In other words: he wasn’t a makeup artist. He wasn’t a tastemaker. He was a systems person. A manufacturing person. A “how do we do this reliably, every time” person.

His insight was contrarian, but clean: as Korea’s economy matured, branding and manufacturing would unbundle. The model that helped chaebols win during Korea’s industrial buildout—one company owning everything end-to-end—would become inefficient in a world where more brands could exist. The people who were great at selling dreams to consumers didn’t necessarily need to be great at organic chemistry.

And Lee didn’t just theorize this from a desk in Seoul. He studied how more advanced cosmetics markets—like Europe—worked, and came away convinced there was room for an ODM-style specialist in Korea too.

What he saw, essentially, was a manufacturing platform hiding in plain sight. If a neutral company could develop formulas and manufacture for lots of brands at once, it could build economies of scale no single brand could match internally. Brands could focus on marketing and distribution. The specialist would focus on the chemistry.

Cosmax would be that specialist.

Founding Cosmax: The Early Struggle

Lee founded the company in 1992 with a tiny team—just four employees—and an operation that was as small as it sounds: a cramped facility in Hwaseong, Gyeonggi Province, roughly 49 square meters.

To learn the ropes, he partnered with a Japanese firm called Miroto and started in cosmetics OEM manufacturing. The business was initially known as Miroto Korea, then renamed Cosmax, Inc. in 1994.

The early years were brutal.

Korean brands didn’t want to hand manufacturing over to an unknown outsider. The big conglomerates weren’t about to help a potential threat gain traction. And Cosmax ran into the classic platform cold start: brands wouldn’t place orders without proven capability, but Cosmax couldn’t build capability without orders.

Then came 1997—the Asian Financial Crisis.

The shock was nationwide. Businesses collapsed, incomes fell across households, and unemployment surged. The era of “we’ve always done it this way” ended fast. Companies that once treated outsourcing like a dirty word suddenly needed to cut costs, reduce fixed assets, and stay alive.

Beauty followed the same script. As consumers traded down to more affordable products, brands leaned harder on outsourcing, and OEM and ODM players started to see real demand. Start-up cosmetics companies, especially—short on capital and distribution—couldn’t justify building labs and factories. They needed someone else to do it.

The catastrophe that nearly broke Korea’s economy also created the demand shock that validated Cosmax’s model. Lee had bet the old system couldn’t hold forever. He was right—just not on the timeline, or for the reasons, he expected.

And here’s the strategic kicker: even if the incumbents saw it coming, they couldn’t respond cleanly. AmorePacific and LG Household & Health Care couldn’t suddenly become contract manufacturers for other brands without undermining their own premiums and positioning. Cosmax could build the capability precisely because it didn’t have that conflict.

It had nothing to protect—so it could build everything to win.

III. Inflection Point 1: The ODM Revolution

From OEM to ODM: The Transformation

To understand Cosmax’s leap, you need to get one seemingly small distinction in manufacturing models—because it changes who holds the power.

OEM, or Original Equipment Manufacturing, is classic contract manufacturing. A brand comes in with a product concept and a spec, and the factory produces it to instructions. It’s execution. Think: a chef cooking your recipe.

ODM, or Original Design Manufacturing, flips the script. The manufacturer develops the product—formula, texture, performance, often even the packaging direction—then brands choose from that innovation and put their name on it. Think: a chef who creates the menu, perfects the dishes, and lets you open a restaurant around them.

Cosmax committed to this. Starting in 2004, it invested roughly 5% of sales into R&D to build real ODM muscle. A decade later, that bet showed up on the scoreboard: by 2015, Cosmax had become the world’s largest cosmetics ODM, surpassing Intercos in sales.

This was the most important strategic decision in the company’s history. Cosmax stopped being a factory waiting for purchase orders and started showing up with finished products—things the market didn’t even know to ask for yet.

The "Gel Eyeliner" Moment

Every platform company has a proof point—the thing that makes skeptics stop rolling their eyes and start returning calls. For Cosmax, it was gel eyeliner.

Cosmax became the first Korean ODM to win a major award in this category, and notably, the only winner among finished-product suppliers—recognized for developing a gel-type eyeliner that went on to become a global bestseller.

This wasn’t just a hit product. It was a technological flex. The gel eyeliner signaled that Cosmax’s labs could create textures and performance that even the biggest beauty houses struggled to reproduce internally. That changed negotiations overnight. Brands weren’t paying Cosmax to follow directions anymore. They were coming to license Cosmax’s inventions.

Cosmax went on to develop and manufacture eyeshadow and eyeliner products for Maybelline, a signature brand within the L'Oréal Group, supplying markets across Asia.

Building the Formula Library

The real moat wasn’t gel eyeliner. It was what gel eyeliner represented: a repeatable system for inventing, refining, and reusing formulations.

Cosmax developed flagship products that became pillars of modern K-Beauty—CC creams, gel eyeliners, cushion foundations—then built the capability to iterate them endlessly.

Here’s the compounding economics. When Cosmax develops a new cushion foundation, it pays the R&D cost once. After that, it can create variations—different finishes, different shades, different climates, different price points—and sell those versions to dozens of brands. The incremental R&D on each “new” SKU can be tiny. The library grows, and each new formula becomes another building block.

Over time, Cosmax expanded global research and production to the point where it secured annual capacity of about 2.8 billion units—enough, as the company frames it, for roughly one in three people worldwide to use a Cosmax-made product.

By the mid-2010s, Cosmax’s formula library reportedly exceeded 70,000 proprietary recipes. That’s not just a spreadsheet of ingredients. It’s decades of trial-and-error around stability, texture, manufacturing yield, and regulatory constraints across many countries. Competing with Cosmax isn’t just buying equipment. It’s recreating institutional memory—something that’s incredibly difficult to do on purpose, and almost impossible to do quickly.

R&D as Sales

Chairman Lee Kyung-soo has been explicit about what wins in beauty: new technology creates new experiences, and consumers recognize innovation when they feel it. In his view, that requires enthusiasm and creativity inside Cosmax—not just efficient manufacturing.

The strategic move is simple and powerful: in a crowded market, R&D becomes the sales pitch. When Cosmax walks into a brand meeting with a novel texture, a new delivery mechanism, or a formulation that solves a stability problem the client has been stuck on, they’re not competing on price. They’re creating demand.

Cosmax backs that up with real firepower: roughly 1,300 staff work across its R&D centers in Korea and abroad. This kind of R&D intensity would look irrational for a commodity manufacturer. For an ODM, it is the whole job.

And it’s why the model can scale in a way people miss if they only look at it like “manufacturing.” The first version of a breakthrough formula is expensive. The hundredth variant can be dramatically cheaper to create—while selling for roughly the same value to the client. That hidden operating leverage is one of the reasons Cosmax could grow so fast, for so long, without growing headcount at the same rate.

IV. Inflection Point 2: The China Gamble (2004–2015)

The Contrarian Bet

In the early 2000s, when Korean companies talked about “going global,” they usually meant heading west—into the United States, Japan, or Europe. Those were the rich, established markets where Korean brands dreamed of standing next to the big French and American houses.

China didn’t fit that mental model. In 2004, it was still widely seen as the world’s factory floor: a place you went to manufacture cheaply for export, not a place you went to build a serious consumer business. Per-capita income was far lower than Korea’s, the middle class was just beginning to form, and “modern” beauty consumption was concentrated in a handful of cities like Shanghai and Beijing.

Lee Kyung-soo looked at that and saw the beginning of something, not the end.

When Cosmax entered China in 2004, it didn’t show up as a basic OEM. It came in as a customized ODM. The bet wasn’t simply geographic expansion—it was timing. Lee was wagering that a massive new consumer class was about to appear, and when it did, beauty would be one of the first categories to explode.

And because China’s modern beauty market was still early, the winners wouldn’t only be imported giants. Entirely new local brands could emerge—fast—and scale even faster.

The “In China, For China” Strategy

Cosmax’s playbook in China was simple in slogan and hard in execution: in China, for China.

Instead of running China like an overseas branch of Korea, Cosmax localized deeply. It invested in local research and innovation to understand what Chinese consumers actually wanted, then built products around those realities rather than trying to force-fit Korean hits into a different market.

It also competed on speed without surrendering quality. While some Japanese and Italian suppliers were delivering in around three months, Cosmax pushed delivery down to roughly half that—about a month and a half to two months—while still meeting customer requirements.

Localization wasn’t just about language or staffing. It meant formulations for different skin tones and different climates: humidity in the south, pollution in industrial cities, and intense UV exposure in highland regions. It also meant different aesthetics. The “glass skin” ideal, for example, translated into specific expectations for texture, finish, and luminosity that weren’t identical to Korean standards.

One concrete proof point: lip products. Cosmax leaned into lip tints designed for Chinese preferences—especially a stronger focus on moisturizing wear—and the category scaled. The company has produced more than 200 million units of lip tints alone.

Powering the C-Beauty Explosion

By the late 2010s, China’s domestic beauty scene went from “emerging” to impossible to ignore. A wave of new makeup brands—Florasis, Perfect Diary, Judydoll, Colorkey, and others—appeared in rapid succession from 2016 to 2018, and then kept accelerating.

This was the C-Beauty breakout: local brands built for local consumers, distributed through social commerce, and amplified by platforms like Tmall and Douyin. Some of these companies grew at stunning speed, reaching massive scale in just a few years.

And underneath many of them was Cosmax.

The reason is almost too on-the-nose: when dozens of young brands all need great product, fast, without building factories or hiring chemists, the company that can reliably invent and manufacture at speed becomes the platform. Chinese cosmetics firms were impressed with Cosmax’s performance, and order volumes surged.

The numbers tell the same story. Cosmax’s China sales were under KRW10 billion in 2008. They surpassed KRW100 billion by 2014. And by 2021, they exceeded KRW660 billion.

In a little over a decade, China moved from “expansion market” to one of Cosmax’s most strategically important engines.

Navigating THAAD: Political Risk Management

Of course, the Korea–China relationship hasn’t exactly been stable.

In 2016, the THAAD incident triggered a sharp backlash against Korean cultural exports, which spilled into consumer products. K-pop events were canceled. Korean dramas were pulled from platforms. Korean cosmetics brands felt the impact as Chinese consumers turned away from anything that looked overtly Korean.

Cosmax’s insulation came from where it sat in the stack.

Because it was manufacturing for Chinese brands with Chinese marketing—not pushing Korean brands into China—it was less exposed to nationalist consumer sentiment. People boycotting Korean brands weren’t necessarily boycotting the invisible Korean company making products for their favorite domestic labels.

That’s one of the underrated advantages of being infrastructure. When politics get ugly, brands are targets. The pipes tend to keep running.

And Cosmax didn’t retreat. After the COVID-19 pandemic, as China’s economy became shakier and some cosmetics companies exited the country, Chairman Lee invested 150 billion won to open a new headquarters in Shanghai’s Xinzhuang Industrial Zone—designed to bring everything from R&D to marketing under one roof.

Even as many multinationals reduced exposure, Cosmax doubled down. It operated seven facilities in China, with total annual production capacity there of 1.49 billion units.

For investors and observers, that creates the classic risk-reward profile. Geopolitical and macro risk in China is real. But China remains one of the world’s biggest beauty markets—and Cosmax’s “local-first” positioning gives it a kind of resilience that pure Korean consumer brands rarely have.

V. Inflection Point 3: The "Fast Beauty" & Indie Wave (2015–2020)

The Death of the Department Store Brand

In the mid-2010s, beauty’s center of gravity moved.

For decades, the industry ran through department store counters—controlled lighting, trained consultants, and brands that won through patience and budget. You built awareness with national ad campaigns, paid for celebrity endorsements, and fought for shelf space one buyer meeting at a time. The whole machine rewarded incumbents.

Then social media flipped the table.

All of a sudden, a college student with five million Instagram followers could launch a lip gloss, sell directly to her audience, and rack up real volume before an old-school prestige brand could even get a new shade approved. The barrier to attention collapsed. The bottleneck moved downstream—into product development and manufacturing.

“Anyone can do it. The barrier to entry isn’t high at all,” said Lee Sun-young, founder of fruit-based cosmetics startup Kikiglow. “And the market is all about indie brands right now.”

She was right about demand. But someone still had to actually make the product.

Lowering the MOQ

Traditional cosmetics manufacturing was built for huge brands and predictable retail calendars. Minimum order quantities were often punishing—tens of thousands of units per SKU, sometimes more. That’s fine if you’re L’Oréal rolling out nationwide. It’s impossible if you’re an influencer testing your first launch, or a scrappy founder with a Shopify site and a point of view.

Cosmax saw what was happening: a whole new class of customer was arriving. Not conglomerates placing massive orders, but thousands of small and mid-sized online brands that cared about two things above all else—low minimums and short lead times.

So Cosmax changed the rules.

It pushed MOQs down to levels that made the long tail manufacturable. In many cases, the floor was already far lower than the old industry standard—often around the low tens of thousands rather than the old “50,000 or 100,000.” And when COVID made forecasting even harder, some overseas facilities, including in China, were said to be able to handle runs as small as a few hundred units.

This did something subtle but powerful: it turned Cosmax into a farm system.

A tiny brand could start with a limited run, learn what customers actually bought, and then scale—without switching suppliers, re-qualifying a new factory, or risking a change in texture that could trigger customer backlash. Cosmax could grow with its customers, and the winners—inevitably—became meaningful accounts.

Speed as a Competitive Weapon

If MOQ was the ticket into the game, speed was the advantage that decided who won.

In the old world, a cosmetics product might take a year or more to go from concept to shelf. That timeline matched seasonal fashion cycles and retailer planning. But social media doesn’t operate on seasonal calendars—it operates on weeks.

When a “latte makeup” trend spikes on TikTok, the opportunity window is short. Move slowly and the trend is gone before your product exists.

So Cosmax compressed the cycle. Brands could move from concept to launch in roughly two to three months—fast enough to catch the wave instead of studying it in hindsight. And importantly, this speed didn’t come at the expense of what had made Cosmax credible in the first place: quality control. It’s a big part of why global brands, including firms like L’Oréal, trusted Cosmax as a partner for fast-cycle delivery.

The flywheel effect is obvious once it starts. Brands that launch faster win more attention. Winning brands place more orders. More orders create more learning, more repetition, and more operational muscle. The manufacturer that can move quickly becomes the default choice—and then gets even faster.

Powering the K-Beauty Export Wave

At the same time, another wave was cresting: K-Beauty was going global.

Sheet masks, essences, cushion compacts, and snail mucin serums went from niche imports to mainstream staples. Sephora and Ulta carved out space. Consumers weren’t just buying Korean brands; they were buying into Korean product sensibilities—textures, finishes, and a constant drumbeat of newness.

Cosmax rode that wave—and helped generate it.

It first became widely known as the Korean manufacturer behind eyeshadows for Etude House. It made many of the makeup products popular with K-pop idols, and it became the first company in Korea’s cosmetics industry to reach $100 million in exports. Alongside Kolmar Korea, Cosmax emerged as one of the leaders of the supplier layer that powered the whole K-Beauty machine.

Behind many of the export winners—brands like Clio, Peripera, and others—Cosmax was the engine. It had spent years building the formulations, textures, and production reliability that made Korean brands unusually capable of launching quickly and scaling globally. When Western consumers decided they wanted Korean skincare, Cosmax didn’t have to pivot. It was already set up to deliver.

That’s why South Korean beauty startups were able to appear, iterate, and scale at a pace that competitors elsewhere struggled to match. And it’s why Cosmax came to account for around 26% of South Korea’s cosmetics exports last year.

The big lesson of the Fast Beauty era is that demand-side disruption didn’t make manufacturing less important—it made the right kind of manufacturing more valuable. When attention got cheaper and trends got faster, the scarce resource became the ability to turn an idea into a great product, quickly, at a scale that matched the moment.

That’s exactly what Cosmax had spent decades building.

VI. Inflection Point 4: Going Global & The Nu-World Struggle (2017–Present)

The Ambition: Conquering America

By the mid-2010s, Cosmax had won the game it set out to win in Korea, and it had built a second growth engine in China. But if it wanted to be the undisputed global leader in cosmetics ODM, there was one market it couldn’t treat as optional: the United States—the biggest beauty market in the world by consumer spending.

Asia dominance was not enough. Cosmax needed a real American footprint.

Its first major step came in 2013, when it entered the U.S. by acquiring a manufacturing facility in Solon, Ohio from L’Oréal and establishing Cosmax USA. The plant wasn’t theoretical capacity on a slide—it had been producing L’Oréal products for years, with existing equipment and trained workers. Cosmax paid roughly $7 million for the three-building complex, a 330,000-square-foot site that looked like a shortcut to credibility.

On paper, it was a clean move: buy a functioning asset from a global giant, inherit a baseline of capability, and then layer Cosmax’s R&D and operating system on top.

The Nu-World Acquisition

Four years later, Cosmax went for the second, bigger bite.

In 2017, Cosmax acquired U.S.-based NuWorld Beauty for $50 million to expand its presence in North America. NuWorld came with what Cosmax needed most: scale, U.S. customer relationships, and strength in color cosmetics. With a manufacturing plant in New Jersey, NuWorld was described as the third-largest cosmetics manufacturer in the U.S., employing around 1,000 people and producing color products, nails, and perfumes.

Strategically, this was the “complete the set” moment. If Ohio could anchor skincare production and New Jersey could anchor color, then Cosmax could pitch American brands a full-service menu—skincare, makeup, and more—without forcing customers to stitch together multiple suppliers.

Cosmax also had longer-term ambitions baked into the deal language: preempt the U.S. cosmetics ODM market early, expand into OBM-style services, and lower costs by securing local R&D and manufacturing infrastructure. It was the same playbook that worked elsewhere—just deployed on the industry’s home turf.

The Integration Crisis

Then reality arrived.

The U.S. expansion turned into a classic “works in Asia, breaks in America” integration problem. Cosmax USA struggled, and the Ohio operation in particular became a drag. Fixed costs were high, capacity outpaced sales, and the unit stayed in the red.

The underlying issues were structural. Labor and compliance costs were higher than what Cosmax was used to optimizing around in Korea. The customer base behaved differently, with different expectations and purchasing patterns. And the competitive landscape wasn’t empty—American contract manufacturers already had entrenched relationships and their own capabilities.

By 2022, Cosmax made the painful call: shut the Solon, Ohio facility and consolidate U.S. operations in New Jersey, with plans to transfer some equipment to NuWorld.

In other words, the “easy entry” via Ohio didn’t become the beachhead Cosmax hoped for. The company had to simplify, retreat to where it had the best chance of making the numbers work, and rebuild from there.

The Turnaround

After the consolidation, Cosmax USA started to reposition itself away from being viewed as a contract packaging base and toward what Cosmax actually sells at its best: innovative formulas and fast, reliable execution.

It also reframed who it was going after. The restructured U.S. business leaned into clients that valued novelty and innovation, including names like Victoria’s Secret and Macy’s.

B.J. Lee, who runs Cosmax’s U.S. business and is the founder’s son, put his finger on the shift in consumer behavior: “In the past, consumers would stick with a brand for 10 years or so and become extremely loyal. But with K-beauty, the ups and downs are extreme. New brands are coming out all the time, and people are constantly chasing the next exciting thing.”

That’s basically Cosmax’s home-field advantage—fast product cycles and trend responsiveness—translated into an American context.

The U.S. remained strategic despite the setbacks. The business rebounded, with sales growing sharply to around 20 billion won. The bet was no longer “win America by transplanting our footprint.” It was “win America by selling what we’re uniquely good at.”

Southeast Asia: The "Next China"

While America was being restructured, Cosmax was also placing another big bet—this time on Southeast Asia. The thesis echoed the China play from a decade earlier: markets like Thailand and Indonesia were growing quickly, local brands were proliferating, and influencer-driven demand was pulling product development faster than legacy supply chains could keep up.

Thailand is the clearest signal of intent. Cosmax began construction on a new production plant for its Thai subsidiary in Bang Phli, with an investment of 1.5 billion baht. The new facility is planned to be nearly four times the size of its current Thai plant, and is set to begin full-scale operations in September 2026. Once online, it’s expected to bring annual capacity up to about 230 million units—roughly tripling current output in the country.

The timing makes sense. Thailand is the largest cosmetics market among ASEAN member states, and demand has been rising alongside the growth of new, influencer-led brands. Cosmax Thailand’s revenue jumped to 43.5 billion won last year, up more than 70% year over year, and the subsidiary has posted rapid growth since 2022.

Indonesia tells a similar story. In 2023, Cosmax Indonesia surpassed 100 billion won in annual sales for the first time, after years of strong growth.

From the outside, the NuWorld saga reads like a warning label: cross-border M&A is easy to announce and hard to make work. But Southeast Asia suggests Cosmax did what good operators do after a bruising expansion—it took the lesson, tightened the playbook, and pushed it into markets where localization and speed are decisive.

The “in China, for China” idea was never just about China. It was about how Cosmax travels. And in Thailand and Indonesia, that approach appears to be working again.

VII. The Future: OBM and the Platform Vision

From ODM to OBM: The Next Transformation

The same force that pushed Cosmax from OEM into ODM is now pushing it toward a new model again: OBM—Original Brand Manufacturing.

In ODM, Cosmax invents and produces the product, and the brand puts its name on it. OBM goes a step further. It’s built for a world where influencers and celebrities don’t just want to “launch a product,” they want to launch a brand—and they want it to feel coherent on day one.

So Cosmax expands the menu. In addition to formulation and manufacturing, it offers brand concept development, design, positioning, and storytelling. The pitch is essentially a total solution: not just a finished product, but the logic around why it exists and how it should show up in the market.

Under this model, Cosmax isn’t merely making items—it’s helping assemble businesses. The client gets something close to a brand-in-a-box: product, packaging direction, concept, and marketing strategy. In theory, all the client needs to bring is capital and distribution.

Zoom out, and you can see the platform endgame. An influencer with an audience no longer needs technical expertise—or even much organizational capacity—to ship a cosmetics line. Cosmax becomes the operating system. The influencer becomes the interface.

Digital Transformation: AI and Data Analytics

To make that platform vision real at scale, Cosmax has been leaning hard into digitization—using tools like big data, IoT, AI, and enterprise systems to tighten the value chain and respond to increasingly demanding global customers.

The core idea is straightforward: product development gets better when it’s faster, more data-informed, and easier to repeat. Cosmax is working to use AI to connect consumer trend signals to formulation possibilities—matching raw ingredients to what the market is asking for, and what different skin types and preferences can support.

The long-term vision is “one-person-one-formula” manufacturing: personalized products tailored to individual needs, without losing the economics of mass production.

As Chairman Lee put it, “Rather than producing large volumes of a single product, we need to adopt a model that allows faster learning and validation through smaller, more diverse production runs.”

That line matters because it’s a philosophical shift. It’s moving from mass production to mass customization—and it fits the same pattern Cosmax has followed for decades: lower the barrier, speed up the cycle, and let more brands experiment.

In the best-case version of this future, Cosmax looks less like a traditional manufacturer and more like a utility. Just as AWS lets companies spin up computing power without owning servers, Cosmax wants brands to spin up products without owning labs, chemists, or factories.

The Premium Pivot

As Cosmax expands the platform, it’s also trying to change what its name means.

The group has laid out a strategy to reposition “Made by COSMAX” as a premium manufacturing label—one associated with research, innovation, and top-tier product execution. The plan centers on strengthening R&D, increasing collaboration across global subsidiaries, and accelerating entry into new markets.

Chairman Lee has framed premiumization as essential for the next phase of K-Beauty. He’s also argued that what counts as “premium” is shifting. In the past, premium brand value was anchored by luxury houses like LVMH. In the future, he predicts the market will increasingly reward brands with differentiated function and technological credibility—especially those built on dermatological technology.

All of it ladders up to a clear strategic goal: become the AWS of Beauty—an infrastructure layer so useful, so embedded, that Cosmax wins regardless of which brand is winning on TikTok.

For investors, though, OBM creates a new tension alongside the upside. The upside is obvious: if Cosmax captures more of the value chain, margins can expand. The risk is strategic ambiguity. At what point does “helping clients build brands” start to look like competing with them?

VIII. Playbook: Lessons for Builders

The "Intel Inside" Strategy

Cosmax built its reputation on a paradox: it became a “famous” B2B company while staying largely invisible to consumers. The playbook looks a lot like Intel in the 1990s—become the trusted ingredient brand inside everyone else’s product, and let that trust do your selling.

A few moments made that credibility legible to the market. Cosmax acquired a manufacturing plant from L'Oréal to establish Cosmax USA, then kept building a global footprint that included operations like Cosmax Indonesia. And it earned a rare stamp of approval: Cosmax was selected as one of the L'Oréal Group’s top 100 partners out of more than 23,000 worldwide—the only cosmetics company in Korea to be invited.

That kind of recognition matters less for bragging rights and more for what it signals. If you can satisfy the most demanding buyer in the category, you instantly become safer to choose. In B2B, prestige is not a vanity metric. It’s a moat.

R&D as Sales

Cosmax is known for a string of “Korea First” achievements in certifications, including ISO 9001, GMP, and Ecocert. Those acronyms can feel like paperwork, but in beauty manufacturing they’re shorthand for something every brand cares about: you can trust what comes off the line.

The bigger point, though, is how Cosmax sells.

“We don't take a snapshot of what is hot on the market today; we anticipate where the market is headed next.”

That’s the core move. In a world where manufacturing can become a race to the bottom, the best sales pitch is an innovation the client didn’t know to ask for. Cosmax invests heavily in R&D so it can walk into meetings with answers—new textures, new delivery mechanisms, new formulas—then win the business because it created the demand in the first place.

Localized Globalization

“This consumer-centric approach isn't just a driver in Asia, but also in the US and Europe thanks to our subsidiaries, which are purposely staffed by a mix of both Korean and local teams. Our goal is to fuse Cosmax's Korean DNA with local consumer demand.”

That’s Cosmax’s globalization model in one quote: bring the operating system, not a copy-paste product. When it enters a country, it builds local staff, local research, and local formulation capability so the output matches local consumers and local regulations.

It’s fundamentally different from the “colonial” approach many multinationals take—export the same product, keep decision-making at headquarters, and assume the market will conform. Cosmax adapts the platform to the market.

Counter-Positioning Against Incumbents

Once Cosmax made manufacturing accessible, it changed who could compete. If a big, high-quality supplier is willing to do the heavy lifting, suddenly people with little prior experience in cosmetics can join the K-beauty free-for-all—and some of them will build real businesses.

That’s also how Cosmax carved out protected strategic space. It positioned itself against the Korean conglomerates—AmorePacific and LG H&H—by serving the long tail of small rebels. The conglomerates couldn’t respond cleanly without undermining their own brand-first models. Cosmax could. And that counter-positioning didn’t just help it grow; it helped keep the incumbents from crushing it early, when it was still small enough to be vulnerable.

IX. Analysis: Power & Forces

Hamilton's 7 Powers Framework

Cornered Resource: The Formula Library

Cosmax’s most defensible asset is its formula library—more than 70,000 proprietary formulations built up over decades. Each one is the end result of endless iteration: stability, texture, regulatory compliance, manufacturability, yield. You can build a factory in a year. You can hire chemists in a quarter. You can’t fast-forward institutional memory. For a would-be entrant, replicating this library isn’t a project—it’s a generation.

Scale Economies

Cosmax and Kolmar Korea manufacture roughly 2.9 billion and 1.6 billion items per year, respectively, across domestic and overseas facilities.

At that scale, raw materials become a weapon. Ingredients that smaller labs buy at premium prices get negotiated down through volume purchasing, long-term supplier relationships, and better logistics. The advantage isn’t just cheaper inputs—it’s more reliable access, better consistency, and more room to experiment without blowing up unit economics.

Switching Costs

If a brand moves its hero product to another factory and the texture changes even 1%, customers revolt. The switching costs aren’t contractual—they’re emotional and sensory. Consumers build a kind of muscle memory around the way a product feels, spreads, absorbs, and wears. Change it, and the internet notices. That makes manufacturing partners sticky in a way that doesn’t show up neatly on a balance sheet.

Porter's Five Forces

Threat of New Entrants: Low

Between the capital required for high-quality facilities, the regulatory maze of certifications, and the slow-build nature of know-how and formula databases, the barriers to entry are steep. Beauty looks easy from the outside. At manufacturing grade, it’s not.

Bargaining Power of Buyers: Mixed

Large clients like L’Oréal have leverage and can push hard on price and terms. But the thousands of indie and mid-sized brands that now make up the long tail don’t have the same negotiating power. Many of them aren’t choosing between five equivalent suppliers—they’re choosing the one that can get them to market fast, at high quality, without surprises.

Rivalry: Intense but Concentrated

In Korea, the core competitive fight is essentially a two-player race: Cosmax versus Kolmar Korea. Both have been pushing toward record sales and crossing the 2 trillion won (about $1.37 billion) threshold.

It’s fierce rivalry, but it’s not a fragmented free-for-all. It’s closer to a duopoly—two scaled players competing for leadership while also benefiting from the same rising tide: global demand for K-Beauty and fast-cycle product innovation.

The Bear Case

Low Operating Margins

Cosmax’s trailing twelve months net profit margin is about 2%. That’s the reality of manufacturing—even when it’s sophisticated, R&D-heavy, and operationally complex. The upside is scale and stickiness; the downside is that the math rarely looks like branded consumer goods.

China Exposure

Cosmax operates seven facilities in China and has meaningful exposure to Chinese domestic brands. If geopolitical tensions escalate—between Korea and China, or China and the West—Cosmax can’t fully sidestep the blast radius. Being “infrastructure” helps, but it doesn’t make the risk disappear.

Vertical Integration Risk

Cosmax helped enable a generation of brands that didn’t need factories to exist. The irony is that the biggest winners may eventually decide to build their own manufacturing as they scale, chasing margin capture and control. The question is whether, for those brands, the flexibility and speed of an ODM partner remains worth more than owning production outright.

Key Performance Indicators

For ongoing monitoring, investors should focus on two primary KPIs:

-

Customer Concentration Ratio: How much revenue comes from the top 10 clients versus the long tail. A healthier mix signals diversification and reduces dependence on any single whale.

-

R&D Expense as Percentage of Revenue: A proxy for whether Cosmax is still playing the ODM game—innovation, new formulas, and technical advantage—or drifting toward lower-margin, more commoditized OEM work. Historically, 5% or more has been a meaningful marker of commitment to the formula-library moat.

X. Conclusion

The Proxy Bet on Human Vanity

Cosmax is the ultimate proxy bet on the human desire to look good. It doesn’t matter whether the moment is Clean Beauty, Vegan, Snail Mucin, or full-glam everything—Cosmax sells the picks and shovels to every gold rush.

That’s the quiet power of the model. Cosmax was founded in 1992 and grew into the world’s largest cosmetics ODM, supplying around 4,500 brands. And while some famous beauty brands have slowed or stalled as consumers tire of old playbooks, Cosmax kept compounding. Last year, it reported record revenue of about $1.7 billion, up 22% from 2023. In 2024, that translated to 2.17 trillion won in revenue, up from 1.78 trillion the year before.

And the market still expects more. One analyst projected Cosmax could reach 2.6 trillion won in consolidated sales this year—alongside Kolmar—while also delivering record operating profit.

The Legacy

Chairman Lee Kyung-soo has said the secret to growing so quickly—after starting the business at 46—was staying prepared, so he wouldn’t miss opportunities when they appeared.

Now in his late 70s, Lee built more than a company. He built infrastructure that democratized beauty entrepreneurship. The result is a world where, with a point of view, a distribution channel, and a little luck, almost anyone can launch. In South Korea, the number of registered cosmetics sellers has increased sevenfold since 2013, reaching more than 27,000 last year.

Lee has also argued that if K-Beauty strengthens its premium competitiveness, it could even surpass France, the world’s largest cosmetics exporter. As of last year, K-Beauty ranked third in exports, behind France and the United States.

The story of Cosmax is really a story about seeing around corners: that vertical integration would unbundle, that China would become a consumer market, that social media would democratize brand creation, and that manufacturing—done at the right level—could become a platform.

As Lee put it, “The difference between global brands like L’Oréal and K-brands is that K-brands use online channels to quickly deliver the products Millennials & Gen Z want. This is K-brands’ greatest competitive advantage.”

So yes, the lipstick on your vanity might carry a French name, an American name, or a Korean name. But there’s a very good chance a Korean scientist and his company touched it somewhere along the way—quietly, indispensably, and increasingly inescapably.

Chat with

this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with

this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music