Sands China Ltd.: How an American Gambling Empire Conquered the World's Biggest Gaming Market

I. Introduction: The Unlikely Empire at the Edge of China

Picture Macau in late 2004. A former Portuguese enclave on China’s doorstep, better known for faded charm than global ambition. Then a new kind of building lights up the waterfront: a Las Vegas-style casino, loud and modern, pulling in crowds at a scale the city has never seen. Inside, the action is relentless—tables packed, cash moving, chips stacked high enough to change lives.

Watching it all is the man who willed the place into existence: Sheldon Adelson, a relentless entrepreneur who grew up in working-class Boston and never finished college. In a business where payback periods are measured in years, this one is measured in months. The property doesn’t just work—it prints money. And it becomes the opening act for something even bigger: the transformation of Macau into the most lucrative gaming market on Earth, far surpassing Las Vegas.

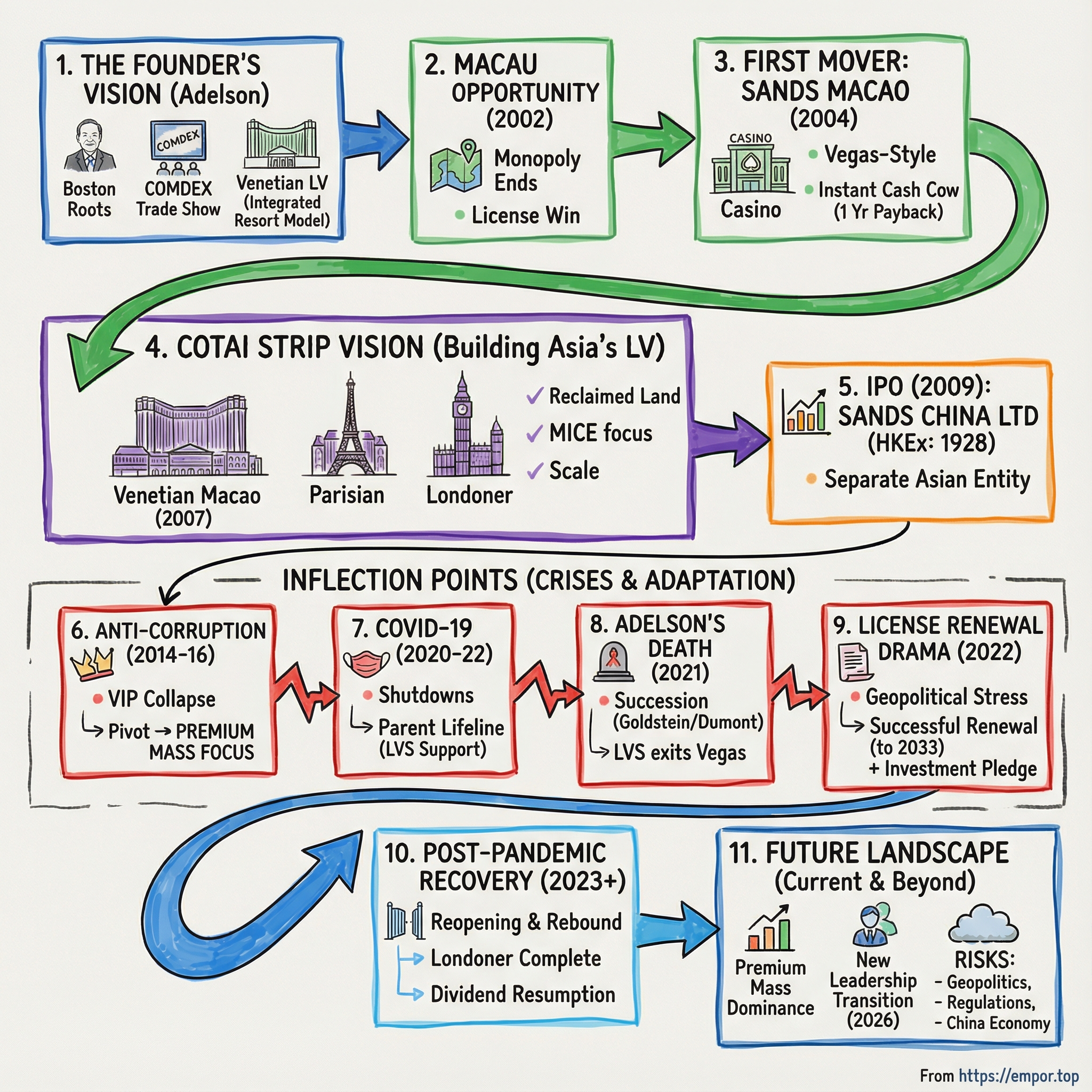

This is the story of Sands China Ltd. (HKEx: 1928), the company that exported the Las Vegas integrated-resort playbook to the only place on Chinese soil where casino gambling is legal—and then scaled it into an empire. Sands China became the leading developer, owner, and operator of multi-use integrated resorts in Macao, in the world’s biggest gaming market by casino revenue.

The question that drives everything is deceptively simple: how did an American company become the dominant force in the one legal casino market in China?

Sands China is a majority-owned subsidiary of Las Vegas Sands Corp. (NYSE: LVS), the same parent that built Marina Bay Sands in Singapore. The corporate structure matters, because it’s how Las Vegas Sands kept control while tapping public markets to fund growth. Over time, LVS has maintained a controlling stake—today, roughly three-quarters of Sands China’s share capital.

And this story doesn’t move in a straight line. It hinges on four inflection points that tested whether the whole model could survive: Xi Jinping’s anti-corruption campaign, which ripped the heart out of Macau’s VIP machine; COVID-19, which shut the doors and starved the city of visitors; the death of Adelson, the founder whose personality was fused to the strategy; and finally, a license renewal showdown that put the entire franchise at risk amid worsening U.S.-China relations.

What follows isn’t just a business success story. It’s a tale of audacity and timing, of policy and geopolitics, of building monuments that only work if the world keeps moving through them—and what happens when it doesn’t.

II. The Founder's Journey: Sheldon Adelson and the Making of a Casino Empire

Dorchester, Boston, in 1933 wasn’t exactly a billionaire factory. But that’s where Sheldon Gary Adelson was born—into a working-class immigrant family, in a cramped tenement apartment, sleeping on the floor alongside his siblings. His father, who had come from Lithuania, drove a cab. His mother, from a Welsh family, ran a small knitting service. Money was tight, and the lesson was constant: if you wanted more, you went out and got it.

Adelson started early. At 12, he was selling newspapers on Boston street corners. By 16, he’d put money into vending machines. It wasn’t a cute childhood hustle. It was the beginning of a lifelong pattern: spot a cash-flowing angle, jump in fast, and move on without nostalgia.

After serving in the Army, he bounced through one venture after another—selling condominiums, working as a mortgage broker, dabbling in venture capital. By his own account, he tried dozens of businesses. Some worked. Plenty didn’t. What mattered was the forward motion. Adelson wasn’t looking for a single perfect plan; he was looking for the one bet big enough to change the scoreboard.

The bet that finally did wasn’t a casino. It was a trade show.

The COMDEX Fortune: A Technology Hater Makes Tech Millions

Adelson reportedly disliked email and didn’t care much for computers. Which makes it even more fitting that his first great fortune came from the tech industry—not by building technology, but by building the place where technology came to perform.

In 1979, he started COMDEX, the Computer Dealers’ Exposition. It quickly became one of the most important gatherings in the industry: the spot where companies unveiled products, cut deals, and competed for attention. Microsoft launched there. Apple showed up there. Everyone paid to be seen there.

Adelson’s insight wasn’t about chips and software. It was about people. Ambitious industries don’t grow in isolation—they grow in rooms full of customers, competitors, and hype. He didn’t need to love computers to understand that the real product was the gathering.

In 1995, he sold his stake in COMDEX for more than $800 million. And in the process, he learned something more valuable than the cash: if a convention could throw off that much profit, imagine what would happen if you owned the building it was held in—and the hotel rooms, restaurants, retail, and entertainment wrapped around it.

That idea became his blueprint.

The Venetian Vision: Born on a Honeymoon

In 1988, Adelson bought the Sands Hotel and Casino in Las Vegas for $110 million. A year later, he and his partners built the Sands Expo and Convention Center—then the only privately owned and operated convention center in the United States. It was a clear tell: he wasn’t chasing gamblers first. He was chasing midweek business travelers with expense accounts and schedules.

But the old Sands itself was aging out of the Strip’s new era. Vegas was turning into a competition of spectacle—bigger, newer, more immersive. Adelson’s answer wasn’t to renovate. It was to wipe the slate clean.

In 1996, he imploded the Sands and started building The Venetian: a Venice-themed mega-resort meant to feel like a destination, not just a casino with a hotel attached. It opened on May 3, 1999, and it didn’t just succeed—it helped rewrite what Las Vegas could be. The strategy was simple: conventions would fill rooms Sunday through Thursday, tourists would fill them on weekends, and the casino would benefit from both. Shopping, dining, and entertainment turned the property into a self-contained ecosystem that didn’t live and die by the tables.

That convention-centric integrated resort model became Adelson’s signature. It wasn’t only about gambling; it was about building a machine that monetized every hour a guest spent on site. And once it worked in Las Vegas, the next question was inevitable: where could this model scale even bigger?

The answer was sitting across the Pacific, on a small peninsula at the edge of China.

III. The Macau Opportunity: Liberalization and the End of Monopoly

To understand why Macau mattered so much to Adelson, you have to start with how strange Macau is.

It’s tiny: a peninsula and a couple of islands stitched together by bridges, roughly 33 square kilometers in total. For centuries it was a Portuguese trading outpost. In 1999, it returned to Chinese sovereignty under the “one country, two systems” framework, similar to Hong Kong.

But Macau had one thing Hong Kong didn’t: legal casino gambling. And for decades, that privilege had been controlled by one man.

For roughly 40 years, Stanley Ho—the “King of Gambling”—held the monopoly through his company, Sociedade de Turismo e Diversões de Macau (STDM). His casinos weren’t the gleaming, self-contained worlds of the Las Vegas Strip. They were older, more utilitarian, and built for a different era, catering mainly to visitors from Hong Kong and parts of Southeast Asia.

Then Macau’s government pulled the lever.

The Great Opening

In 2001, Macau decided to end the monopoly and open the market. The aim wasn’t subtle: transform Macau from a fading post-handover economy into a modern tourism and gaming powerhouse, fueled by international capital and know-how.

The timing could not have been better. China’s economy was accelerating, minting new wealth at scale. Macau sat right on the edge of that demand—reachable from Hong Kong by ferry, and increasingly accessible from mainland China. And it offered something you couldn’t get anywhere else on Chinese soil: a legal place to gamble.

So the government invited international bids for three new gaming concessions. Western operators were expected to bring more than table games—they would bring the integrated-resort model: hotels, shopping, dining, entertainment, and convention business that could pull in broader tourism and keep properties busy beyond the casino floor.

Winning the License: High-Stakes Poker

Las Vegas Sands entered the process with a familiar playbook. Adelson had already proven in Las Vegas that conventions plus a destination resort could create a machine that made money every day of the week. He also had the resources to move fast.

In early 2002, Las Vegas Sands was awarded a provisional gaming license, which led to a sub-concession agreement with Galaxy Casino. Around the same time, other American operators secured rights as well, and Macau’s competitive landscape began to shift from a one-man kingdom to a global-stage contest.

There’s also a political narrative that has followed these licenses ever since—reports and speculation about geopolitics, back-channel influence, and why certain foreign companies were welcomed when they were. The details are contested and often unverified. What isn’t in dispute is the outcome: Macau opened, and major U.S. casino companies gained a foothold.

And that foothold mattered because the prize was enormous. Macau would become the world’s biggest gaming market by casino revenue—and it was the only legal casino market in China. Winning a concession wasn’t just winning the right to build a casino. It was winning access to a once-in-a-generation demand wave.

For Las Vegas Sands, the questions narrowed quickly: could they execute, and could they build fast enough to capture the moment?

IV. First Mover Advantage: Sands Macao and the Vegas-Style Revolution

On May 18, 2004, something Macau had never seen opened on the harbor: Sands Macao. It wasn’t just a new casino. It was the first Las Vegas-style gaming facility in Asia—built fast, built big, and built with a very American belief that if you create the right experience, the volume will follow.

It cost $240 million to construct, which sounds almost modest compared to what Sands would build later. But the real shock wasn’t the price tag. It was the product.

Macau’s existing casinos had grown up under Stanley Ho’s monopoly: functional, familiar, and geared primarily around the gambling itself. Sands Macao arrived with a different playbook. It looked and felt modern. It ran on service, perks, and polish—comps, hospitality, food, and entertainment designed to keep people in the building longer and bring them back sooner. And it wasn’t aimed at a single type of gambler. From day one it blended mass market action with VIP and premium play, plus dining and entertainment wrapped around the floor.

The Speed of Returns

Then the economics turned surreal.

Casinos are supposed to be long-payback businesses. Build for years, open, and slowly earn your money back over a half-decade or more. Sands Macao flipped that logic on its head: it recouped its investment in about a year.

Demand was immediate and relentless. Gamblers poured in—many of them experiencing this style of casino for the first time—and the property’s waterfront location turned it into a magnet. For Adelson, the timing and ownership structure made the outcome even more dramatic. He owned 69% of the stock personally, and as Sands Macao took off, his net worth didn’t just rise—it multiplied, more than fourteen times over.

By May 2005, the mortgage bonds used to finance construction were paid off. In casino terms, that’s not a good opening. That’s an extinction-level event for anyone who assumed Macau would change slowly.

A Template for Transformation

Sands Macao did more than throw off cash. It proved that a foreign operator could thrive in the post-liberalization era—and that Macau’s ceiling was far higher than anyone had modeled under the old monopoly. Just as importantly, it showed what the next phase should look like: not standalone casinos, but integrated destinations that could sell rooms, meals, shopping, entertainment, and meeting space alongside the gaming.

Sands would later describe itself as the leading developer, owner and operator of integrated resorts and casinos in Macao as measured by adjusted EBITDAR—an operator whose properties weren’t just casino floors, but full ecosystems of conventions and exhibitions, retail and dining, and entertainment venues.

The formula had revealed itself: take the Las Vegas integrated-resort model, tune it for Asian customers, plug it into the world’s biggest and fastest-growing consumer base—and then scale.

Which meant there was only one real question left: would Adelson stop at a single hit on the waterfront, or would he try to remake the map?

He didn’t stop.

V. The Cotai Strip Vision: Building Asia's Las Vegas

If Sands Macao proved the model could work, Cotai was where Adelson tried to make it inevitable.

Cotai—named for the land connecting Coloane and Taipa—was reclaimed from the sea and earmarked by the Macau government for large-scale hotel and casino development. New land, new rules, and no legacy footprint. To Adelson, it wasn’t just a development site. It was a clean sheet of paper big enough to redraw the entire market.

The Venetian Macao: A $2.4 Billion Bet

The anchor was The Venetian Macao. It opened on August 28, 2007, and it was designed to overwhelm you on purpose.

At the time, it was described as the second-largest building in the world. The resort spanned an almost hard-to-grasp 10.5 million square feet and included more than 3,000 all-suite rooms. It was, in spirit, a near-replica of the Las Vegas Venetian—canals, gondolas, and Venetian landmarks—except built at an Asian scale that made even Las Vegas look restrained.

The $2.4 billion price tag wasn’t about building a nicer casino. It was a declaration that Macau wasn’t going to be a collection of gambling halls anymore. It was going to be a destination.

And Adelson immediately pushed the story bigger. He coined the name “Cotai Strip,” deliberately echoing the Las Vegas Strip, and talked about turning this reclaimed stretch of land into a dense, walkable cluster of mega-resorts. He promised a pipeline on the order of 20,000 hotel rooms and $12 billion of investment.

But the most important piece wasn’t the canal. It was the calendar.

Adelson’s real strategic edge—just like in Las Vegas—was conventions. Sands built MICE into the heart of the integrated resort, aiming for a business engine that could fill rooms and drive spending even when the casino cycle cooled. The company pointed to assets like Cotai Expo, described as one of the largest convention and exhibition halls in Asia, and major entertainment venues including the Cotai Arena and the Venetian Theatre, alongside theaters and arenas at later properties like The Parisian and The Londoner. The point was simple: in this model, gaming mattered—but it wasn’t the only reason to come.

Building the Portfolio

Once the Venetian was up, Sands kept stacking the neighborhood.

In 2008, Las Vegas Sands opened a Four Seasons hotel next door. Later came The Londoner Macao—originally launched as Sands Cotai Central—and The Parisian Macao.

Each addition did two things at once: it expanded Sands’ own capacity, and it made Cotai more compelling as a destination. The Parisian, which opened in 2016, leaned hard into spectacle with its half-scale Eiffel Tower. Sands Cotai Central, later rebranded as The Londoner Macao, added thousands more rooms and helped create the critical mass that makes an integrated resort district feel like a place, not a project.

Today, Sands China’s core Macau portfolio includes Sands Macao, The Venetian Macao, The Plaza Macao, The Parisian Macao, and The Londoner Macao—an unusually concentrated set of integrated resort assets in one market.

For investors, the appeal was obvious and intoxicating: a market being built in real time, on newly created land, with growth that seemed tied to China’s expanding wealth. Macau’s structure—only a handful of licensed operators—kept competition bounded, while public investment in infrastructure steadily improved access.

In other words: Sands wasn’t just building properties. It was helping build the entire stage they would perform on for decades.

VI. The 2009 IPO: Separating the Asian Crown Jewel

Then the world cracked.

The 2008 financial crisis hit Las Vegas hard, and it hit Las Vegas Sands even harder. The company’s share price collapsed as the U.S. economy seized up, and Adelson ended up putting $1 billion of his own money in to keep the business afloat. Projects slowed or stopped. Next to the Venetian in Las Vegas, the St. Regis Residences tower sat unfinished—an exposed, concrete marker of just how close the whole empire came to stalling out.

But halfway around the world, the story looked very different.

Macau kept humming. While Western consumers pulled back, Chinese gamblers kept coming. That contrast wasn’t just good luck. It revealed something structural: Las Vegas and Macau weren’t the same business. They ran on different customers, different demand cycles, and different kinds of risk. And in that moment, separating them started to look less like a financial move and more like a survival strategy.

Creating Sands China Ltd.

At the center of the Macau story was Venetian Macau Limited, the subsidiary that held one of the limited concessions or sub-concessions granted by the Macao government to operate casinos and gaming areas. That entity—and the cluster of assets it represented—became the foundation for something new: a standalone public company built around Macau.

Sands China Ltd. was incorporated in the Cayman Islands on July 15, 2009. On November 30, 2009, it listed on the Main Board of the Hong Kong Stock Exchange. The IPO raised about HK$19.4 billion, roughly US$2.5 billion, and left Las Vegas Sands with a majority stake of around 70%.

The timing was audacious. Barely a year removed from the worst financial shock since the Great Depression, Las Vegas Sands was asking public markets to put a premium value on its Asian operations. Investors didn’t flinch. The deal was oversubscribed, and the stock popped on its first day of trading.

Strategic Rationale

The carve-out did several jobs at once.

It plugged Sands into Hong Kong’s capital markets, giving the company another funding source and natural currency alignment with a business earning in Hong Kong dollars and Macau patacas. It sent a clear message that, while the West was still licking its wounds, the Asia growth thesis was intact. And it let investors price Macau on its own terms, instead of blending it into the volatility of a recovering U.S. Strip business.

Most importantly, it created flexibility without surrendering control. Las Vegas Sands kept the steering wheel, but Sands China became a financing platform—publicly traded equity that could help fund the next wave of building in Macau, while the parent company stabilized back home.

It was, in other words, a corporate structure designed for a single purpose: keep the Cotai vision moving forward.

VII. Inflection Point #1: Xi Jinping's Anti-Corruption Campaign (2014-2016)

By 2013, Macau had become a money machine on a scale the casino world had never seen—about $45 billion a year in gaming revenue, roughly seven times Las Vegas. But the engine powering that machine was narrow and fragile. The center of gravity wasn’t the tourist wandering in off the ferry. It was the VIP room.

Most of that VIP business flowed through junkets: middlemen who recruited wealthy players from mainland China, extended them credit, handled travel, and made sure debts got paid—often in ways that lived in the gray zones of Chinese law. At the peak, about two-thirds of Macau’s gaming revenue came from VIP play, and the customer base was overwhelmingly mainland Chinese corporate and public officials.

Then the rules of the game changed.

When Xi Jinping rose to the top of the Chinese Communist Party, he launched the most aggressive anti-corruption campaign in modern Chinese history. Suddenly, the very profile of customer Macau had built itself around was the profile least able to be seen in Macau.

The Revenue Collapse

The effect was swift. High rollers didn’t taper off—they vanished. The corporate executive who once treated Macau like an expense-account playground now saw that kind of trip as a career risk. Public officials faced intense scrutiny over any conspicuous spending, and casino gambling was about as conspicuous as it gets.

VIP revenue started sliding quarter by quarter through 2014, with the declines accelerating as the year went on. And it wasn’t a quick shock followed by a rebound. Macau endured 26 straight months of falling gaming revenue, a brutal streak that didn’t break until August 2016. Across the market, share prices sank and the narrative flipped from “unstoppable growth” to “structurally broken model.”

The Junket System Under Pressure

With VIP demand collapsing, the junkets that had fueled the boom suddenly looked less like partners and more like liabilities. Some downsized. Some shut down. The whole system was under a harsher spotlight.

Years later, the final act would come in November 2021, when Alvin Chau—the founder of Suncity Group and the most famous figure in the junket world—was arrested and later sentenced to 18 years in prison for running an illegal gambling empire. Chau had helped industrialize the model that brought high rollers from mainland China, where marketing or soliciting gambling is illegal, into Macau’s VIP rooms. When he fell, what remained of large-scale junketing fell with him, taking a major pillar of Macau’s old playbook down for good.

The Forced Pivot to Mass Market

For Sands China, the downturn was painful—but it also validated a strategic choice that looked almost conservative during the boom. Sands had leaned harder than some rivals into mass-market gaming and the broader integrated resort: hotel rooms, dining, shopping, and entertainment that could attract ordinary visitors, not just VIPs routed through junkets.

That distinction mattered. The anti-corruption campaign targeted the optics and mechanisms of VIP play; it didn’t shut down the desire of everyday tourists to visit Macau. And while VIP produced huge volumes, mass-market play tended to be a better business—higher margin, less dependent on credit, and less exposed to the political sensitivities of junkets.

So the industry pivoted toward “premium mass”: affluent, high-spending recreational gamblers who didn’t need a junket to show up, but still wagered enough to matter. It wasn’t the same kind of growth Macau had enjoyed before, but it was sturdier—and it became the foundation for what came next.

For investors, the lesson landed with force: Macau’s gaming industry doesn’t just compete on service and square footage. It operates at the pleasure of Beijing. In this market, political risk isn’t theoretical. It’s operational—and it can rewrite the business overnight.

VIII. Inflection Point #2: COVID-19 and the Near-Death Experience (2020-2022)

On February 5, 2020, Macau did something it had essentially never done in the modern era: it turned off the lights. Every casino closed under a government order as COVID-19 arrived. For 15 days, the tables went silent, the slot floors went dark, and the economic engine of the city stopped.

And then came the real shock: the shutdown was the easy part.

The Endless Restrictions

Macau’s business model is simple and brutally concentrated: people have to physically show up. And Macau depends overwhelmingly on visitors from mainland China.

As much of the world reopened in fits and starts through 2021 and into 2022, China held to “zero-COVID.” That meant quarantine rules, testing requirements, and sudden travel restrictions that could change overnight. Even when casinos were technically open, the pipeline of customers was squeezed so tightly that demand couldn’t recover in any normal way.

The numbers told the story in one line. In August 2020, Macau’s gross gaming revenue was down 94.5% year over year, to just $166.6 million. That wasn’t a cyclical dip. That was the market nearly disappearing.

Financial Strain and the Parent Lifeline

With revenues collapsing, Sands China still had to carry the weight of a massive resort footprint: staffing, debt service, upkeep, and all the fixed costs that don’t care whether the baccarat tables are full or empty.

In that environment, the corporate structure that once looked like a clever financing tool became a lifeline. Sands China entered into a term loan agreement with its parent, Las Vegas Sands, for $1 billion. One key purpose was to help meet a new MOP$5 billion registered capital requirement tied to the licensing process that was coming for every operator.

By the first half of 2022, the damage was showing up plainly in the financials: Sands China reported a $760 million loss for the first six months of the year.

And there was another constraint that made the squeeze even tighter. Macau’s government expected operators to maintain employment levels as the industry headed into concession renewal. In other words: even in a historic demand collapse, the workforce couldn’t just be treated as a variable cost.

The Human Decision

This is where the story gets personal, because for Las Vegas Sands, the pandemic landed while Sheldon Adelson was still alive.

Adelson insisted that team members keep receiving full pay and health care benefits, even while the buildings they worked in were closed. It was an expensive choice—hundreds of millions of dollars during a period when the revenue line was collapsing. But it also reflected the long game Sands was playing in Macau: these were multi-decade franchises, dependent on government partnership and public trust, and the license renewal clock was ticking.

The Divergence

By mid-2022, the contrast across Sands’ world was almost surreal. Las Vegas had come roaring back. Marina Bay Sands in Singapore was posting record results. Yet Macau—Sands China’s core—remained boxed in by mainland policy.

The pandemic didn’t just hurt the business. It exposed the deepest structural risk in the model: when you’re dependent on mainland Chinese visitors, you’re dependent on mainland Chinese decisions. And those decisions could keep the doors functionally closed for years.

IX. Inflection Point #3: The Death of a Founder (January 2021)

On January 11, 2021, Sheldon Adelson died at his home in Malibu, California. He was 87. The cause was complications from treatment for non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma.

For the first time since 1988, Las Vegas Sands existed without the force of personality that had built it. Adelson wasn’t just the chairman and CEO; he was the strategy. He was the one who had pushed the company into Macau early, insisted on scale, and bet on integrated resorts as a fundamentally different business than a casino with hotel rooms attached.

And the timing couldn’t have been harsher. COVID was still throttling Macau. Travel restrictions were squeezing the entire model. The next round of license renewals—an existential test for every operator—was getting closer. In the middle of all that, the company lost the founder who had always seemed most comfortable when the stakes were highest.

Three days later, on January 14, Adelson’s body arrived in Israel. His coffin, draped in U.S. and Israeli flags, was displayed at Ben Gurion Airport as Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu paid his respects. He was buried the next day in a small private ceremony on the Mount of Olives in East Jerusalem.

The question for Las Vegas Sands wasn’t whether he’d be honored. It was whether the company could keep moving without him.

The Succession

The board moved quickly. Robert Goldstein became chairman and CEO in January 2021, formalizing a transition that signaled stability more than reinvention.

Goldstein had been with the company since 1995, joining during the planning for The Venetian in Las Vegas. He’d helped shape the property’s identity by bringing in high-end retail, major restaurants, and leisure attractions—the kind of non-gaming gravity that made Adelson’s model work. He wasn’t an outsider brought in to “fix” anything. He was one of the people who built the playbook.

The family also remained close to the center of power. Patrick Dumont—Adelson’s son-in-law—was promoted to president and chief operating officer. Dumont joined Las Vegas Sands in 2010, became CFO in 2016, and stepped into the new role in January 2021.

Continuity vs. Change

Then came a decision that, in any other era, would have felt like heresy: Las Vegas Sands exited Las Vegas.

In 2022, the company completed the roughly $6.25 billion sale of The Venetian Resort Las Vegas—The Venetian, Palazzo, and the Venetian Expo—to affiliates of Apollo Global Management and VICI Properties.

The message from leadership was straightforward: sell the icon to double down where the company’s future already was. As the company put it, the sale allowed Las Vegas Sands to “more deeply entrench in Asia,” where its majority of business holdings sat, and to pursue new development opportunities elsewhere.

It was a clean break. A company named after a Nevada casino no longer owned a single Las Vegas property. The corporate headquarters stayed in the city, but operations became an Asia-only portfolio—Macao and Singapore, with everything riding on how those markets evolved next.

As Goldstein later framed the moment: “This company transformed the industry from a gaming-centric model to the integrated resort model and, through a different strategic approach in each market, meaningfully changed the tourism landscape in Las Vegas, Macao and Singapore. I’ve been fortunate to work with a great team of people over the years, and I specifically want to express my gratitude to Sheldon for his support and friendship.”

X. Inflection Point #4: The 2022 License Renewal Drama

By 2022, every operator in Macau was staring down the same cliff edge: their right to operate was about to expire.

The concessions for Sands China, Wynn Macau, Galaxy Entertainment Group, Melco Resorts & Entertainment, SJM, and MGM China were all set to run out on June 26, 2022. In the end, Macau granted a short extension while it finalized the rules of the next era—an extension that cost SJM and MGM China 200 million patacas (about US$24.7 million) each.

For Sands China, this wasn’t a routine regulatory renewal. It was the franchise. If the license wasn’t renewed, the company wasn’t “hurt.” It was effectively over—billions in property investment stranded, the Macau business wiped out, and shareholder value crushed. And all of it hinged on a government decision being made as U.S.-China relations deteriorated.

Geopolitical Leverage

That’s what made the renewal so unnerving. Macau is part of China, and Beijing’s priorities shape what happens there. With tensions rising between Washington and Beijing, some analysts openly wondered whether the American-linked operators could become bargaining chips. The uncertainty lingered as the government temporarily extended all six licenses and worked through the details of new gaming legislation.

The New Gaming Law

Macau ultimately kept the number of concessions capped at six. Under the new regime, concessions would run for up to ten years, with the possibility of a three-year extension only under exceptional circumstances.

But the bigger shift wasn’t the headline term length. It was the direction of travel. The new law brought heavier oversight and clearer expectations: more local employment, more required investment in non-gaming attractions, and tighter control over the mechanisms that had powered Macau’s old VIP ecosystem. Most notably, it effectively shut the door on the junket-driven model that had once dominated the market.

The Successful Renewal

In the end, the incumbent lineup survived intact. Macau awarded new concessions to the same “big six”: Sands China, Wynn Macau, Galaxy Entertainment, MGM China, Melco Resorts, and SJM Holdings. The new licenses took effect on January 1 and run through the end of 2033.

The relief came with a price tag. Under the contractual obligations tied to the new concessions, the six operators collectively committed to invest 118.8 billion patacas (about US$14.8 billion) into Macau. Sands China’s share was the largest: a commitment of 30.24 billion patacas (about US$3.7 billion).

That commitment quickly became part of the company’s public narrative. In mid-2023, Sands staged a grand celebration for The Londoner Macao that also served as a marker of the new ten-year concession era. The message was clear: Sands China wasn’t just staying. It was doubling down—pledging to invest about $3.7 billion in Macau over the next decade.

XI. The Post-Pandemic Recovery and Recent Performance

When China reopened its borders in January 2023, Macau finally got the moment it had been waiting for. The tourists could return. The ferries could fill up again. And the casino floors could start to feel like casino floors.

By 2024, the recovery was visible in the market’s top-line numbers: Macau’s gross gaming revenue rose 23.9% year over year to MOP$226.8 billion (US$28.3 billion).

That total was still only about three-quarters of 2019’s level. But the mix of the business had changed in a way that mattered just as much as the headline. The junket era was effectively over, and the operating environment was now largely free of the commission-heavy VIP machine. So even with revenue still below the old peak, operators were keeping more of what they earned.

Sands China's Recovery

Sands China’s results tracked that rebound. The company reported total net revenues of US$7.08 billion, up 8.4% year over year. Adjusted property EBITDA increased 4.7% to US$2.33 billion. And net profit jumped 51.0% to US$1.05 billion, up from US$692 million the year before.

It also held onto the position it cares about most: being number one in Macau. In Q3 2024, Sands China led the market with a 24.5% share, followed by Galaxy Entertainment Group at 19.1%, Melco Resorts at 14.7%, and MGM Macau at 14.8%.

The Londoner Renovation Completion

At the center of Sands China’s recent push was its biggest modern upgrade: the multi-year transformation of Sands Cotai Central into The Londoner Macao. Sands China’s US$1.2 billion Phase II redevelopment was essentially finished, with the company confirming that all 2,405 rooms and suites at the Londoner Grand—formerly the Sheraton Grand Macao—were open and available.

With the Londoner Grand’s official opening in June, the company put a capstone on a broader US$2.35 billion redevelopment program. The goal wasn’t subtle: make The Londoner Macao the new cornerstone of Sands’ Cotai portfolio.

The financial lift showed up quickly. The Londoner generated net revenues of $642 million, up from $444 million in the same quarter the prior year. Following the completion of the Phase II renovation, casino revenue at the property surged 55.7% year over year to $495 million.

Dividend Resumption

For shareholders, the other symbolic milestone was simpler: cash coming back out.

After a five-year pause during the pandemic, Sands China resumed dividends. The board recommended a final dividend of HK$0.25 for the year ended December 31, 2024.

That restart mattered because, before COVID, dividends had been a defining feature of the stock. From 2014 through 2019, Sands China paid annual dividends of HK$1.99 per share—until the pandemic forced a suspension in 2020.

Looking ahead, JP Morgan analysts projected that if financial conditions allow, dividends could rise meaningfully from 2026 onward, potentially reaching HKD 1.50 per share annually.

XII. The Current Macau Landscape and Market Dynamics

By the first half of 2025, Macau—the world’s biggest casino market—looked like a place that had survived the storm and was trying to settle back into a rhythm.

The rebound that took hold in 2024 carried into the first six months of 2025, but with a more measured feel. The easy part of the recovery was over. Now the question was whether growth could continue without the old VIP machinery that used to supercharge the market.

One data point captured the mood. Macau’s Gaming Inspection and Coordination Bureau reported August 2025 gaming revenue of MOP 22.16 billion (about $2.77 billion), up 12.2% year over year. It was the strongest month of the year so far—good news, but also a reminder that the market was now climbing in steadier steps, not taking the elevator.

The Shift to Premium Mass

The post-junket era has forced a rewrite of the playbook. Instead of relying on middlemen to funnel VIPs into private rooms, operators have leaned into the mass market—and, especially, the premium mass customer: visitors who don’t need credit from a junket, but still spend heavily across gaming, hotels, dining, shopping, and shows.

Those adaptations have been central to why Macau has been able to keep recovering at all.

For Sands China, that shift has shown up in share gains in the segments that matter most in the new regime. In recent periods, Sands captured about 25% of the premium mass segment. The lift was likely helped by more visitors coming in around concerts at The Venetian Arena, along with the debut of a progressive jackpot tied to baccarat side bets—small product changes that can matter when the goal is to drive repeat play from high-frequency customers.

Visitor Recovery

On the demand side, the city kept getting healthier. Tourist arrivals continued to rise in early 2025, with March up 11% year over year. Citywide hotel occupancy averaged 90.1%, up from 84.9% in 2024.

Cotai, in particular, benefited from exactly the kind of travel Macau now wants more of: regional visitors, family tourism, and short-haul leisure trips that fill rooms, restaurants, and retail—not just the gaming floor.

The Government’s Economic Dependence

For all the talk of diversification, Macau is still a company town—except the company is gaming.

The government has been pushing operators to invest in more non-gaming attractions, but the public finances remain overwhelmingly tied to casino performance. In the first ten months of 2024, 81.2% of Macau’s government revenue came from gaming taxes.

That dependence cuts both ways. Operators need concessions to exist. But Macau’s government also needs the operators to thrive, because their success funds public services. It’s a partnership built on mutual leverage—and it shapes every major decision in the market.

XIII. Leadership Transition: The Post-Goldstein Era

In Las Vegas Sands’ next act, the leadership baton was set to pass again.

The company announced that Robert G. Goldstein—chairman, chief executive officer, and a long-time senior executive—would transition to the role of senior advisor on March 1, 2026. Goldstein agreed to remain in that advisory role through March 2028.

Succeeding him as chairman and CEO would be Patrick Dumont, the company’s president and chief operating officer. Dumont joined Las Vegas Sands in 2010 and moved through senior strategy, operating, and finance roles before being named chief financial officer in 2016.

In many ways, Dumont’s elevation marked the completion of the succession plan that began when Sheldon Adelson died. As Adelson’s son-in-law, Dumont preserved the family’s involvement at the top of the organization, but he also arrived with the internal credibility of a decade-plus operator shaped inside the Sands system.

Miriam Adelson, co-founder and majority shareholder of Sands, framed it as both gratitude and continuity: “As one of the first employees of the company, our family has great appreciation for Rob’s leadership and the many contributions he’s made over the years. He has left an indelible mark on the history of the company.”

XIV. Investment Analysis: Bulls, Bears, and the Reality

The Bull Case

If you’re bullish on Sands China, you’re essentially betting on a rare combination: a protected seat at the table in the biggest gaming market in the world, and a business model that’s getting cleaner, simpler, and more scalable again.

Start with the moat. Macau is capped at six concessions, and Sands China already has one. That’s not just a competitive advantage; it’s a structural barrier that keeps new entrants out. Within that closed ecosystem, Sands has built an unusually dense presence in Cotai—the part of Macau that matters most for modern tourism. Cotai has become the city’s cluster of world-class integrated resorts, and Sands’ footprint there is built for the post-junket era: mass-market gaming, retail, and non-gaming attractions that keep visitors on property and spending across multiple lines, not just on the casino floor.

Second, the company is coming out of a heavy reinvestment period. The big renovation cycle at The Londoner is now largely behind it. As the company has put it: “The major redevelopment and upgrading of The Londoner is largely complete. From here on in you should expect regular renovation where we will only take modest keys out at any one time.” Translation: fewer disruptions, more rooms available, and less capital expenditure drag versus the years when major sections of the property were under construction.

Third, the strategy shift that Macau forced on everyone is one Sands is relatively well-suited to win. Premium mass—higher-spending visitors who don’t rely on junkets but still gamble meaningfully—is where the economics are best now. Sands China has leaned into that segment with scale and a deep Cotai offering, and the view from analysts has been that it’s positioned to take share in the high-margin mass business.

Finally, there’s the macro tailwind argument: if Beijing’s stimulus efforts and improving sentiment translate into more discretionary spending, Macau tends to feel it. JP Morgan analysts have described the market as being in an “upcycle,” driven by positive wealth effects, rising consumer confidence, and regional stock rallies.

The Bear Case

The bear case starts with one uncomfortable fact: Sands China is all-in on one place.

It generates all of its revenue from Macau, and Macau is a jurisdiction where operating rights exist at the pleasure of the government—under a broader geopolitical umbrella that has gotten more tense, not less. When you own a Macau casino operator, you’re not just underwriting tourism demand. You’re underwriting policy stability.

Then there’s China itself. Structural challenges like property market stress, demographic decline, and fragile consumer confidence can show up quickly in discretionary spending. And in Macau, discretionary spending is the product. If mainland consumers tighten up, casinos don’t have a diversified set of end markets to fall back on.

There’s also the question of what the market looks like without its old accelerant. The junket crackdown removed what used to be a major revenue engine. Premium mass has helped fill the gap, but the market still hasn’t consistently returned to its pre-2019 peak. The recovery depends not only on demand, but on continued policy accommodation from Beijing and the ongoing health of cross-border travel.

And looming over all of it is regulatory risk. Macau has shown it can rewrite the rules quickly. The anti-corruption campaign demonstrated how fast high-value player behavior can change when political incentives shift, and the post-2022 regime has made oversight and compliance a more central part of the operating reality.

Porter's Five Forces Analysis

Threat of New Entrants: LOW. Macau’s six-concession structure is the barrier. There’s effectively no new competitive entry for the current concession period.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers: MODERATE. Labor is a major cost, and local employment expectations reduce flexibility. But Sands’ scale still gives it leverage with many vendors.

Bargaining Power of Buyers: LOW. For Chinese-language, legal casino gaming, the alternatives are limited. Premium mass customers can be choosy, but the category itself is constrained.

Threat of Substitutes: MODERATE. Illegal and gray-market online gambling exists despite being banned in China. Nearby jurisdictions compete for regional tourism, but they can’t legally market to mainland Chinese citizens in the way Macau can serve them.

Competitive Rivalry: MODERATE. Competition inside the “big six” is intense, especially for premium mass. But the cap on operators and the size of the market reduce the odds of truly destructive price wars.

Hamilton Helmer's Seven Powers

Scale Economies: Significant. A large portfolio lets Sands spread fixed costs across a massive asset base.

Network Effects: Modest. Convention and events can create reinforcing loops—big events drive stays, stays drive spend, and the venue becomes more attractive for the next event.

Counter-Positioning: Limited. The integrated resort playbook has largely been copied across the market.

Switching Costs: Modest. Loyalty systems and player relationships matter, but customers can still move between properties easily.

Branding: Moderate. Venetian and Londoner have real recognition, but gaming spend is often driven by convenience, comps, and perceived value.

Cornered Resource: Significant. The concession itself is the scarce asset—non-replicable, government-granted, and essential.

Process Power: Moderate. Two decades in Macau builds institutional muscle, but the top operators have had enough time in-market to develop similar capabilities.

XV. Key Performance Indicators and What Matters

If you want a simple dashboard for how Sands China is doing from here, you don’t need ten metrics. You need two. One tells you whether the company is winning the customer. The other tells you whether it’s making money the way an integrated resort should.

1. Mass Gaming Revenue Market Share

In today’s Macau, mass—and especially premium mass—is where the battle is fought. So Sands China’s mass gaming revenue market share is the clearest read on whether its portfolio is still pulling its weight.

When Sands holds roughly a quarter of mass gaming, it usually means the fundamentals are working: - its marketing is converting the right customers - its properties still feel like a better “default choice” than the one next door - the on-property experience is keeping people in the ecosystem - its premium mass strategy is landing, not just on opening weekend, but quarter after quarter

This one is also unforgiving. If the share is consistently holding above the mid‑20s, Sands is competing from strength. If it starts slipping toward the low‑20s and stays there, something is off—either the product, the promotions, or the competitive set has moved ahead.

2. Adjusted Property EBITDA Margin

Market share tells you if the building is full. Adjusted property EBITDA margin tells you whether the building is a good business.

This metric cuts through the noise—interest, taxes, depreciation, and other accounting items—to show the underlying operating profitability of Sands China’s resorts. Historically, Sands’ Macau properties have operated around the low-to-mid 30% range.

What to listen for in the margin: - compression usually means higher promotional intensity, rising costs, or mix shifting the wrong way - expansion usually means better operating efficiency, improved pricing, or a healthier mix of higher-margin mass play

And this is where the timing matters. With the major renovation cycle now largely complete, the expectation is that margins should gradually improve into 2026 as disruption fades and more of the portfolio operates at full capacity.

XVI. Material Risks and Regulatory Considerations

Geopolitical Risk

Sands China’s entire business sits inside Chinese jurisdiction, even though it’s controlled by an American parent. That creates a category of risk you can’t hedge with better marketing or nicer hotel rooms: geopolitics. If U.S.-China relations worsen, the fallout could show up in subtle ways—regulatory friction, tougher scrutiny—or, in a true worst case, pressure on concessions or asset security. There’s no indication that any of that is imminent, but it’s also not a risk you ever get to cross off the list.

Regulatory Risk

Macau’s rulebook can move, and it can move fast. The 2022 gaming law changes didn’t just tweak the system; they reset the operating environment. Future tightening—around junkets, table allocations, or even the basic terms of operating—could hit revenue and profitability without warning.

That caution has shown up in the government’s own expectations. The Macau SAR revised its 2025 gross gaming revenue forecast downward, pointing to external pressures like a slowing Chinese economy, currency headwinds, and geopolitical tension, along with uncertainty about how quickly gaming and tourism would fully normalize.

Parent Company Relationship

Sands China is a controlled subsidiary. That means the big decisions—capital allocation, dividend policy, and strategic direction—ultimately roll up to Las Vegas Sands, not minority shareholders.

That dynamic also shows up in ownership. Las Vegas Sands purchased $250 million of Sands China stock during the quarter and in January 2025, bringing its ownership interest to 72.3%.

Currency and Capital Controls

Even when demand is strong, money movement matters in Macau. Sands China earns revenue in Hong Kong dollars and Macau patacas, while many costs are local. More importantly, China’s capital controls shape how easily customers can bring funds into Macau and take them back out. If those controls tighten, visitor spending—and gaming volumes—can tighten right alongside them.

XVII. Conclusion: The Story Continues

Sheldon Adelson died having built something that, on paper, shouldn’t have existed: an American casino empire that came to dominate the world’s biggest gaming market, inside the only place on Chinese soil where casino gambling is legal. The arc from Boston tenements to the Cotai Strip is the full business-story spectrum—vision, timing, leverage, crisis, adaptation, and reinvention.

Sands China today is also not the Sands China of 2004. The early Macau boom ran on VIP play and junkets; the current era runs on premium mass, direct relationships, and an integrated-resort engine that’s meant to hold up even when the political winds shift. The middlemen who once steered a huge share of the action have been pushed out of the system. And the founder’s instinct-driven, personality-forward leadership has given way to a more institutional kind of management.

But the core thesis hasn’t changed. Macau remains the only legal gaming destination for China’s massive population, and Sands China still holds the largest integrated resort portfolio in the market. The concession—the government-granted right to operate—is the true moat, because without it none of the hotels, malls, theaters, or casino floors matter.

"We remain enthusiastic about our opportunities to deliver industry-leading growth in both Macao and Singapore in the years ahead as we execute our capital investment programs in both markets. In Macao, the ongoing recovery continued during the quarter, although spend per visitor in the market remains below the levels reached prior to the pandemic. Our decades-long commitment to making investments that enhance the business and leisure tourism appeal of Macao positions us well as the recovery in travel and tourism spending progresses."

So the forward-looking question isn’t whether Macau will keep existing. It’s what kind of Macau the next decade produces. Will it feel more like the 2004–2014 surge, the 2014–2022 era of policy shocks and shutdowns, or something that looks structurally different from either? The uncomfortable reality is that the biggest inputs—China’s economic path, Beijing’s stance on gambling, and the state of U.S.-China relations—sit mostly outside management’s control.

What Sands can control is execution. And on that score, Sands China has been the most consistent operator in Macau’s modern history. It lived through the anti-corruption campaign that hollowed out VIP. It absorbed a pandemic that functionally turned off the market. It navigated the death of its founder in the middle of the storm. And it came out the other side with its concession renewed, its market position intact, and its business rebuilding.

For investors, the trade is clear. You’re accepting concentration risk—one market, one set of regulators, one geopolitical backdrop—in exchange for exposure to a protected oligopoly and a scaled portfolio built to win the premium-mass era. Whether that’s a fair trade isn’t a universal answer. It’s the whole decision.

But the journey itself is hard to argue with. From a kid selling newspapers in Dorchester to an empire on reclaimed land in Cotai, the story of Sands China is ultimately the story of audacity—and of the thousands of people who turned that audacity into buildings, operations, and a franchise that survived far more than anyone planned for.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music