Shimizu Corporation: 220 Years of Building Japan

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

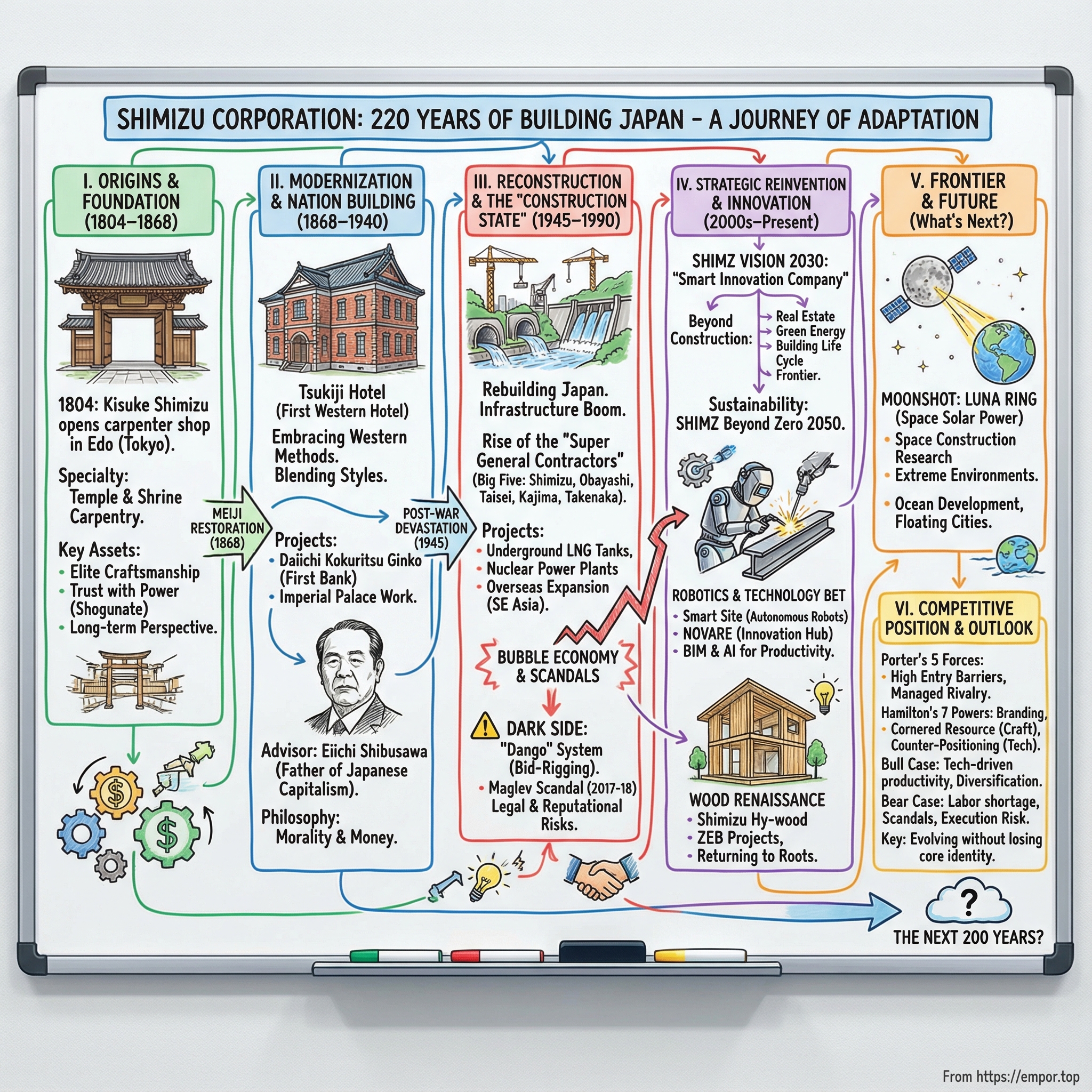

Picture this: it’s 1804. A skilled carpenter named Kisuke Shimizu walks the packed streets of Edo—today’s Tokyo—with his tools on his back and a craft tradition refined over generations. He opens a small shop in Kanda Kajicho, a neighborhood that thrums with merchants, money, and proximity to power. His specialty is temples and shrines: buildings that weren’t just architecture, but anchors of community and symbols of permanence.

Now jump forward more than two centuries.

The company that carries his name employs thousands of people, brings in roughly $15 billion a year, and sits among the top construction firms in the world. Shimizu has built everything from landmark towers in places like Singapore to massive underground LNG tanks—industrial-scale infrastructure that quietly keeps modern life running. And at the same time, its engineers have put serious thought into something that sounds like science fiction: construction on the moon.

So how does a carpenter’s shop founded in the final years of the Tokugawa shogunate survive long enough to help build the 21st century—and even sketch plans for the lunar surface?

Because Shimizu’s story isn’t only the story of one company. It’s a lens on how Japan was built, rebuilt, and reimagined across revolutions, wars, booms, busts, and demographic decline. This is a family business that lived through the fall of the shogunate, the Meiji Restoration, two world wars, the post-war economic miracle, and the bursting of the bubble—then kept going, adapting to new realities like labor shortages and global competition. Today, Shimizu Corp. (TYO: 1803) is one of only two construction companies in the Nikkei 225, alongside Taisei.

As of November 2025, Shimizu’s trailing twelve-month revenue was $13.67 billion USD. It operates as one of Japan’s “Super General Contractors”—the Big Five firms that dominate the upper tier of the country’s construction industry. But what sets Shimizu apart inside this club is the continuity: an unbroken lineage back to 1804, making it one of the oldest continuously operating construction companies in the world.

In this deep dive, we’ll follow the arc that longevity demands: family capitalism and how it evolves; the hidden incentives—and occasional scandals—inside a cozy, relationship-driven industry; and the constant pressure to reinvent a hands-on, physical business for a world that increasingly runs on software, automation, and energy transition. We’ll also see how Shimizu has expanded beyond pure construction into five adjacent businesses: Real Estate Development, Engineering, Green Energy Development, Building Life Cycle, and Frontier ventures.

A company that began by building sacred wooden structures now talks about harvesting solar power on the moon. Let’s trace how that happened—and what it says about Japan, about construction, and about the strange endurance of institutions that learn how to change without losing their core.

II. Origins: From Temple Carpenter to Nation Builder (1804–1868)

In 1804, a master carpenter named Kisuke Shimizu made a move that would ripple through Japanese history for the next two centuries. He left his home in what is now Toyama Prefecture, headed to Edo—the shogun’s capital, already a metropolis—and opened a small shop in Kanda Kajicho. His niche wasn’t houses or storefronts. It was sacred architecture: temples and shrines, the buildings that held Japan’s spiritual life together.

To get why that matters, you have to understand what temple and shrine carpentry meant in the Edo period. These weren’t “construction jobs” in the modern sense. They were sacred commissions. They demanded techniques refined over generations, joints and beams fitted with astonishing precision, and an ethic of permanence: you were building something meant to outlast you. The craftsmen trusted with that work sat at the top of the hierarchy—because if you could be trusted with the gods, you could be trusted with anything.

The timing helped, too. Edo had grown into one of the largest cities in the world, with a population of more than a million. Temples and shrines weren’t just religious centers; they were stable, prestigious patrons—anchor clients before the concept existed. Their projects pulled in donations and sponsorship from wealthy merchants and feudal lords, which meant that building sacred structures also meant gaining access to the networks that actually ran the city.

Shimizu’s early projects cemented his reputation. The firm took on repair work at Nikkō Tōshō-gū, the ornate shrine-mausoleum of Tokugawa Ieyasu, founder of the shogunate. Today it’s part of the Shrines and Temples of Nikkō UNESCO World Heritage Site, with dozens of structures included and five designated as National Treasures. But in the early 1800s, the meaning was simpler and more powerful: this was one of the most politically significant sacred sites in Japan, and Shimizu had been trusted to maintain it.

And that trust went even closer to the center of power. Kisuke Shimizu also contributed to construction on the West Wing of Edo Castle itself—the seat of the shogun. In an era when proximity to authority could determine who thrived and who disappeared, that kind of work didn’t just pay. It positioned the company.

Underneath all of this was the system that made firms like Shimizu durable: the construction guilds’ master-apprentice pipeline. Skills weren’t written down in manuals. They were learned by doing—year after year—until technique became instinct. That traditional technology would be handed down in an unbroken line from Shimizu’s founding onward, forming a deep reservoir of know-how in wooden structures that the company would carry into every new era.

That foundation mattered because change was coming. When Japan’s world cracked open in 1868, Shimizu had something that was hard to copy and impossible to buy: elite craftsmanship, a reputation built on sacred and shogunal work, and the organizational discipline to deliver complex projects. The carpenter’s shop that started with temples was about to meet a country determined to reinvent itself.

III. The Meiji Transformation: Building Modern Japan (1868–1940)

On the morning of January 3, 1868, Japan’s old order effectively ended. After 260 years of Tokugawa rule, the Meiji Restoration began—and the country faced a blunt reality: modernize fast, or risk becoming a Western colony.

For Shimizu, that was both a threat and an opening. The shogunate—the ultimate patron behind so much elite work—was gone. In its place came a new government determined to build railways, factories, ministries, banks, and all the physical infrastructure of a modern state. The winners would be the builders who could absorb Western methods without losing the rigor and reliability that Japanese clients expected.

Shimizu’s first big proof point arrived almost immediately. In September 1868, the Tsukiji Hotel opened in the Tsukiji Teppozu area of Edo, in what is now Chuo-ku, Tokyo. It was Japan’s first fully Western-style hotel, planned by the Edo Shogunate as lodging exclusively for foreigners. The American architect Richard P. Bridgens produced the basic design, and Kisuke Shimizu II was put in charge of the working design and construction.

For the company, the job was more than a hotel. It was a crash course in the future. Kisuke Shimizu II read the moment correctly: Western architecture wasn’t a novelty, it was the new standard. He went to Yokohama—an open port where foreign technology and know-how were entering Japan—and set out to learn. What emerged wasn’t imitation, but synthesis: a quasi-Western style that blended Western forms with Japanese techniques.

The Tsukiji Hotel itself made that blend visible. The exterior used Japanese elements like namako-style walls common to storehouses and samurai residences, while adding Western touches like a chimney, a weather vane, and a veranda that wrapped around the building. Built along the shore with a large landscaped garden, it was designed to lure travelers moving between Tokyo and Yokohama. And then, just four years after completion, it burned and was completely demolished in a fire.

But the lesson stuck, and Shimizu carried it straight into finance—literally. In 1872, Kisuke Shimizu II built Daiichi Kokuritsu Ginko, Japan’s first bank, in Kabutocho, Tokyo. It was originally planned for the Mitsuigumi, but after the National Bank Ordinance was enacted, it was transferred to the newly established Daiichi Kokuritsu Ginko. The building became a milestone of the enlightenment period: a demonstration that Shimizu could translate Western-style architecture into something functional, credible, and Japanese-made. The originality, ingenuity, and technical skill behind the work helped give shape to quasi-Western architecture—and to modern Japanese architecture itself.

Around this time, Shimizu also formed what may have been its most important relationship of the era: Eiichi Shibusawa, the industrialist widely known as the father of Japanese capitalism. Shimizu appointed Shibusawa as a senior advisor and anchored its management philosophy in his book, Rongo to Soroban (The Analects and the Abacus). Shibusawa’s argument was deceptively simple: morality and money can look opposed, but you need both. A nation can’t develop unless the private sector creates wealth—yet wealth won without regard for the public interest won’t last.

That idea—business as social contribution, not just profit extraction—took root inside Shimizu. And it wasn’t only a philosophy on paper. The former residence of Eiichi Shibusawa, with its parlor designed by Kisuke Shimizu II, still stands as the only surviving example of Shimizu II’s work—a physical artifact of a partnership that shaped the company’s identity.

As Japan surged forward, Shimizu graduated from symbolic projects to national ones. It rebuilt the Second Meiji Palace in 1888, after the first burned down in 1873. In 1921, it constructed the first Dai-ichi Life building, designed by the celebrated architect Tatsuno Kingo. These weren’t just contracts. They were statements: Japan was modern, and Shimizu was one of the firms trusted to build that modernity in stone and steel.

Inside the company, leadership passed through the family line: Shimizu Teikichi led from 1915 to 1940, followed by his son Shimizu Yasuo, who would guide the company from 1940 to 1966. And even as it embraced new methods, Shimizu kept its oldest advantage sharp. Since Tokyo Mokkoujou Arts & Crafts Furnishings opened in 1884, workers had honed and passed down woodworking skills that traced back to the firm’s temple-building roots. Today, Shimizu operates the only factory among Japan’s major construction companies that offers advanced woodworking technology and skills.

By the eve of the 1940s, Shimizu had learned to live in the tension that defines great builders: tradition and transformation, sacred craftsmanship and industrial modernization. It was a skill the company would need—because Japan was about to enter catastrophe, and then a reconstruction boom that would remake the country yet again.

IV. Post-War Reconstruction & The Construction State (1945–1990)

In August 1945, Japan lay in ruins. Tokyo had been firebombed into ash. Hiroshima and Nagasaki had marked the terrible birth of the atomic age. For a construction company, the devastation was first and foremost a national tragedy—but it also created the defining industrial mission of the era: rebuild the country, fast, and at enormous scale.

Out of that urgency came something peculiarly Japanese: the “Construction State” (doken kokka). Public works didn’t just patch potholes; they became an engine of economic revival and a tool of political power. And at the center of this system stood a small handful of firms that could actually deliver projects big enough, complex enough, and risky enough to match the country’s ambitions.

Japan calls them the Super General Contractors—the Big Five: Shimizu, Obayashi, Taisei, Kajima, and Takenaka. These companies were in a different weight class from the rest of the industry. Even just by headcount and sales, they towered over typical contractors, with workforces in the thousands and revenues that put them in a league of their own.

What makes the dominance even more striking is the backdrop: Japan had hundreds of thousands of authorized construction companies. Yet the biggest players captured a huge share of the market, and the Big Five alone accounted for a meaningful slice—an extraordinary concentration for an industry that, on paper, looked fragmented.

But their real edge wasn’t simply size. The Big Five operated like vertically integrated design-build machines—what you might call management contractors. They didn’t necessarily keep large armies of site labor on payroll; much of that work came through subcontractors. Their internal talent was concentrated where control and leverage lived: design, research, engineering, and construction management. Collectively, these firms employed an enormous number of registered architects—more than Japan’s largest standalone architectural practice, Nikken Sekkei, could match.

Shimizu’s post-war trajectory is almost a case study in how this model played out. It designed, built, and renovated the backbone of modern Japan: tunnels, bridges, dams, urban infrastructure, and energy facilities. In 1970, it completed Japan’s first underground LNG tank—and then went on to build roughly half of the large underground LNG tanks that exist in Japan today. These are not glamorous structures, but they are the kind of quietly critical infrastructure that makes an advanced economy possible.

The company also became deeply involved in nuclear construction. In the nuclear field, Shimizu built Japan’s first nuclear power plant and went on to handle building and civil design and construction for multiple types of nuclear facilities. Japan’s first commercial nuclear power plant, the Tōkai Nuclear Power Plant, connected to the grid on July 25, 1966, using major components imported from the General Electric Company in the UK.

And Shimizu didn’t just build at home. In the 1970s it began expanding overseas, eventually accumulating a track record across more than 60 countries. After opening an office in Singapore in 1974, it took on manufacturing facilities, high-rise buildings, hospitals, bridges, and subways—projects that made Southeast Asia a key proving ground for Japanese super-contractors.

By the late 1980s, Japan’s bubble economy pushed this whole system to its peak. Tokyo’s real estate mania drove construction to surreal heights. The Big Five prospered. But the very structure that made them powerful—the tight, relationship-driven triangle between contractors, government officials, and politicians—also laid the groundwork for something darker. The post-war bargain that fueled reconstruction was drifting into a system the public would soon view far less charitably.

V. The Dark Side: Bid-Rigging, Scandals & The "Dango" System

To understand Shimizu fully, you also have to understand the system it grew up in—and the system has a name: dango.

The word literally means “consultation” or “discussion.” In construction, it came to mean something far more specific: competitors quietly meeting before a public bid to decide who would win, roughly at what price, and how everyone else would stay in line. In other words, bid-rigging—not as a rare scandal, but as a normalized operating system. For decades, it wasn’t treated like cheating the market. It was treated like managing the market.

That’s why the maglev scandal of 2017–2018 hit as hard as it did. Tokyo prosecutors indicted four leading contractors—Taisei, Kajima, Obayashi, and Shimizu—over alleged bid-rigging tied to Japan’s magnetic-levitation train project. The Japan Fair Trade Commission filed a criminal accusation against what it called the “Super 4,” the four biggest construction companies in Japan by turnover. The JFTC said the companies had agreed on designated winners and coordinated bids so those winners could secure contracts for new terminal stations on the maglev line.

The investigation painted a picture of coordination, not coincidence. In December 2017, prosecutors raided the headquarters of Taisei and Obayashi over alleged antitrust violations linked to the maglev project. Authorities alleged that between April 2014 and August 2015, the firms conspired to divide up contracts for two new stations ordered by Central Japan Railway Company—down to discussions of the estimate prices each would submit.

Shimizu’s posture shifted as the case tightened. Reports indicated it sought lighter penalties by acknowledging bid-fixing by the deadline after initially denying wrongdoing. It followed Obayashi, which told the JFTC it had colluded by sharing information and carving up work packages connected to the Tokyo–Nagoya line.

In October 2018, the legal process produced a clear, public outcome. The Tokyo District Court ordered Obayashi to pay $1.8 million in costs and fines and Shimizu $1.6 million for violating Japan’s Anti-Monopoly Act. Judge Takumi Suzuki said the collusion had “prevented fair and free competition.” Both companies admitted their involvement in bid-rigging.

The allegations focused on construction work at Shinagawa and Nagoya stations between April 2014 and August 2015. The investigation’s initial trigger was narrower: a contract Obayashi won in 2016 to build an emergency exit at Nagoya station. Ultimately, across 22 works packages, Obayashi and Shimizu each won four, while Kajima won three.

What made the scandal feel bigger than the fines was what it implied. Japan’s construction industry is large, politically influential, and repeatedly entangled in bid-rigging cases. So the real question isn’t whether dango exists. It’s whether the structure that enables it can actually change—and what that would do to an industry built on stable shares, predictable pipelines, and relationships that last longer than any single project.

It also raised an uncomfortable point: why would companies of this size risk criminal prosecution over contracts that, relative to their total revenues, weren’t existential? The answer is in the incentives. Market share matters. Client relationships matter—especially with major buyers like JR Central. And in a world where everyone assumes everyone else is coordinating, defecting from the “understanding” can be as risky as participating in it.

And this wasn’t just history. In 2025, reports surfaced that Shimizu BLC, a Shimizu subsidiary, was under investigation by the Japan Fair Trade Commission over orders for large condominium repair and renovation projects. The JFTC conducted onsite inspections at around 20 companies amid suspicions of bid-rigging tied to condominium-repair work.

For investors—and for anyone trying to understand Shimizu’s durability—this is the double-edged sword. Managed competition can support steadier margins and reduce volatility. But it also creates recurring legal exposure, reputational damage, and the constant risk that a tougher enforcement cycle rewrites the economics overnight.

VI. Key Inflection Point: SHIMZ VISION 2030 & Strategic Reinvention

After the maglev scandal, Shimizu faced a familiar problem with an unfamiliar twist: it still knew how to build, but the world around building was changing. Labor was getting tighter. Projects were getting bigger and riskier. Materials and energy prices were no longer stable assumptions. And reputational risk wasn’t theoretical anymore.

So in May 2019, Shimizu unveiled something more ambitious than a standard corporate plan. SHIMZ VISION 2030 was a statement of intent: a 220-year-old contractor wanted to become something closer to a technology-and-infrastructure company—one that still pours concrete and raises steel, but doesn’t rely on that alone. Shimizu’s own phrase for the destination was a “Smart Innovation Company,” built around creating new value beyond traditional construction, often through co-creation with partners outside its usual orbit.

The targets made the ambition tangible. By fiscal 2030, Shimizu aimed for consolidated ordinary income of ¥200 billion or higher. It also laid out a deliberate shift in where profit should come from: 65% from construction and 35% from non-construction businesses. Geographically, it targeted a portfolio that was still mostly Japan—75% domestic—but with a larger overseas engine at 25%.

To translate the 2030 vision into near-term execution, Shimizu later developed its Mid-Term Business Plan〈2024-2026〉, announced in May 2024.

What does “beyond construction” actually mean in Shimizu’s world? The company kept its core Construction Business—building construction, civil engineering, and overseas construction—but expanded focus into five additional areas: Real Estate Development, Engineering, Green Energy Development, Building Life Cycle, and Frontier businesses.

The most intuitive move is real estate. Shimizu takes the same technical and project expertise it uses to deliver buildings for clients and applies it to developing properties itself—office buildings, logistics facilities, and more. It has been building under its own brands, including the i-Mark Building series for offices and the S.LOGi series for logistics. And it didn’t keep this playbook confined to Japan: Shimizu entered overseas real estate development in 2011, pursuing projects like condominiums, data centers, and office buildings in Southeast Asia and North America.

Then there’s energy—where the “smart innovation” framing starts to look less like branding and more like positioning for the next industrial cycle. Shimizu develops and operates renewable generation such as solar and biomass. It also runs a zero-carbon green power retail business through its wholly owned subsidiary, Smart Eco Energy Co., Ltd., combining its own generation, externally sourced non-fossil power, and green power certificates to support the move toward a zero-carbon society.

And Shimizu wasn’t only trying to win projects in offshore wind—it invested in the hardware of the industry itself. The company has been building a Jack-Up Vessel, a specialized offshore construction ship designed for wind installations, positioning Shimizu to participate in the expected expansion of offshore wind across Japan and the broader Asia region.

Of course, vision statements collide with reality. Over the past five years, Shimizu and its peers were hit by shocks that no mid-term plan from the pre-pandemic world could fully anticipate: COVID-19, then the ripple effects of the situation in Ukraine, including sharp increases in construction material and energy prices. Shimizu said it hit its sales targets over that period, but fell short on profit targets—an important distinction in an industry where risk lives in execution, not in backlog.

Threaded through all of this is another layer: sustainability, not as an add-on, but as a declared corporate direction. Shimizu set an environmental vision called SHIMZ Beyond Zero 2050, and SHIMZ VISION 2030 explicitly included the goal of helping realize “a sustainable society where future generations can inherit a well-cared for environment.”

Internally, Shimizu framed this shift as requiring a new mindset—what it called “Choukensetsu”—and positioned the Mid-Term Business Plan〈2024-2026〉, beginning in fiscal 2024, as the start of building a stronger foundation for continued growth.

For investors, the bet is straightforward to state and hard to execute: can Shimizu transform without losing its footing? Can it fund new growth areas while staying disciplined in its core construction business—especially when cost volatility and project complexity can erase profits quickly? Shimizu is asking the market to believe that a centuries-old builder can diversify into a broader infrastructure, energy, and technology portfolio—and do it without becoming unfocused.

VII. The Robotics & Technology Bet

Walk onto a Shimizu job site today and you might see something that would have stopped Kisuke Shimizu I in his tracks: robots moving through the work like crew members, not curiosities. They roll up to steel, scan it, and weld. They lift ceiling boards, hold them steady, and fasten them in place. This isn’t a trade-show demo. It’s Shimizu Smart Site—Shimizu’s most aggressive attempt to turn construction into a higher-productivity, lower-labor business.

The motivation is as practical as it is urgent. Japan’s workforce is aging, skilled labor is harder to secure, and “workstyle reform” is pushing companies to do more with fewer hands. Shimizu’s answer is to redesign the job site itself so it needs less human muscle—especially for the punishing, repetitive tasks that wear workers down and make the industry less attractive to the next generation.

At the center of Smart Site is coordination: autonomous robots tied into AI and BIM, the 3D building models that let a site operate with the same kind of shared “source of truth” that software teams use. Instead of robots working in isolation, the system is designed so machines and people can share the same environment, the same plan, and the same sequence of work.

The key difference from Shimizu’s earlier robotics efforts is autonomy. Previous generations often needed constant human help just to move around, plus endless tweaking on-site—enough that many workers concluded it was faster to do the job themselves. Smart Site’s robots are built to operate autonomously and make decisions in the messy reality of construction, not in a controlled lab.

Two robots show what that looks like in practice.

The Robo-Welder handles one of the hardest tasks to automate: high-precision welding in a harsh environment. Its robotic arm uses laser shape measurement to read the contours of the groove on a steel column. From there, it determines how to execute the weld—down to the steps needed to place the welding material cleanly—then carries it out using an arm with six axes of freedom.

The Robo-Buddy goes after finishing work, where the challenge is less brute force and more dexterity. It controls two six-axis robotic arms. Sensors recognize the ceiling grid frame material and the position for inserting ceiling suspension bolts; then one arm lifts the ceiling board into place while the other screws it in.

Shimizu didn’t just keep this in a pilot environment. It deployed the system on the Toranomon-Azabudai project, one of Tokyo’s marquee developments, and used it for heavy-duty work underground. Robo-Welder welded steel column planks 100 mm thick—reported as a record for the thickest planks welded by a construction robot in Japan. Shimizu also confirmed labor savings: work that typically takes master welders eight man-days per column was reduced to five man-days.

The broader plan was scale. Shimizu targeted using robots to weld roughly 15% of the total weld length—out of about 1,800 km—on the project. The company expected that to translate into labor savings equivalent to roughly 500 welding workers up to topping out, while also easing the burden on welders during Tokyo’s hot, humid summer months.

If robots are the field deployment, then NOVARE is the factory that produces the next generation of ideas. On September 1, 2023, Shimizu launched operations of its innovation and human resources development facility, Smart Innovation Ecosystem NOVARE, in Koto-ku, Tokyo. The “ecosystem” concept is intentional: NOVARE is meant to function like a forest, where circulation and interaction—between people, technology, and training—creates compounding progress.

NOVARE includes the Novare Lab, a research facility focused on technological innovation including construction robots, structures, and materials. And in a subtle but telling touch, the building’s facade carries a three-dimensional pattern made from aluminum casting: a 3D replica of the hand-cut alcove post from the former Shibusawa Residence. That parlor was designed by Kisuke Shimizu II, and it’s the only surviving example of his work. The replica was created using Shimizu’s proprietary AI technology—modern tools used to preserve a symbol of the company’s origins.

For investors, this robotics push is both a promise and a gamble. If Shimizu can consistently cut labor requirements and raise productivity, it can build a real edge in an industry where margins are thin and execution risk is everywhere. But construction tech has a graveyard of expensive experiments. The question is whether Shimizu can turn R&D into repeatable job-site economics—not just impressive one-off records.

VIII. The Moonshot: Space Construction & Frontier Thinking

Every truly long-lived company develops a few enduring instincts—ways of thinking that get baked into the culture. For Shimizu, one of those instincts seems to be asking, relentlessly, “what’s next?” even when the answer sounds impossible. Its lunar construction research is the most extreme, most on-brand expression of that habit.

The headline idea is called LUNA RING, and it reads like audacious engineering fiction—except Shimizu has treated it as a real research direction. The concept: install a continuous ring of solar cells around the moon’s equator, convert that electricity into microwave or laser transmission, and beam the energy back to Earth from the lunar side that always faces us.

The logic, while wildly speculative, is internally consistent. It starts with a premise Shimizu articulates plainly: the world may be moving from a mindset of conserving scarce resources on Earth to one of producing effectively limitless clean energy. LUNA RING is their embodiment of that shift—a moonshot, literally, that marries an original idea with sustained R&D in space technology.

Then comes the question Shimizu can’t help but tackle: if you were going to build it, how would you actually build it?

Their answer leans on a familiar construction principle—use what’s on site, because hauling everything in is ruinously expensive. Shimizu’s concept assumes maximal use of lunar resources to build a power plant. Lunar “sand” is described as an oxide compound, which in this framework means oxygen and water could be produced if hydrogen were transported from Earth. With water, sand, and gravel, they further propose producing cement and making concrete on the moon.

And the workforce wouldn’t look like any construction crew in Tokyo. Robots would lead lunar surface construction, with remote control from Earth enabling round-the-clock operation. Humans would still be required on the moon, but in small numbers—working jointly with robots rather than replacing them.

The bigger picture is infrastructure. In Shimizu’s view, a lunar base is likely to become an important building block for future space development plans. And much of the construction technology developed on Earth—structures, materials, project planning, automation—could be adapted to that environment. Shimizu’s bet is that the capabilities it has accumulated over generations can be pushed, credibly, to the frontier of the moon.

Why does any of this matter if you’re evaluating a construction company on Earth?

First, frontier R&D signals ambition. It’s a talent magnet for engineers who want to work on the hardest problems, not just the next standard project. Second, extreme-environment technologies have a way of boomeranging back into terrestrial use. And third, differentiation matters: in an industry where the Big Five often chase the same categories of work, being the contractor willing to think seriously about space construction makes Shimizu more memorable—to customers, partners, and recruits.

And Shimizu’s “frontier” push isn’t limited to the moon. The company has been moving toward commercialization across four frontier business areas: ocean development, space development, harmony with nature, and venture investment in next-generation technologies. In 2020, it launched a corporate venture capital fund with a budget of 10 billion yen over 10 years to invest in startups and venture capital.

Shimizu is also the only Japanese company participating in “Floating Future,” a research project in the Netherlands exploring floating-city solutions. Taken together, these bets position Shimizu for growth opportunities that don’t fully exist yet—but could emerge as climate change, population growth, and resource constraints reshape where and how people live.

IX. Wood Renaissance: Returning to Roots

There’s a certain poetry in a company that began as a temple carpenter in 1804 now helping drive Japan’s push toward timber high-rises. For Shimizu, wood isn’t a nostalgic side project. It’s both a return to the craft that built its reputation and a practical response to where construction is heading: lower carbon, better buildings, and materials that can scale.

For most of the modern era, wood construction in Japan stayed largely in the low-rise world. The limiting factors were predictable and unforgiving—earthquakes and fire. If Shimizu wanted wood to work in medium and large-sized buildings, it had to solve those constraints head-on.

Its answer is Shimizu Hy-wood, a hybrid approach that uses wood where it makes the most sense, and pairs it with other materials where the physics demands it. The goal isn’t to force wood into every role. It’s to create an “optimal” wood building: one that meets the earthquake and fire-resistance requirements of larger structures, while still delivering the warmth, design flexibility, and construction efficiency that make timber attractive in the first place.

The core engineering move is how different materials are joined. Shimizu Hy-wood uses reinforced concrete joint material to connect and unify columns—or columns and beams—across mixed structures of wood with reinforced concrete or steel. In practice, that allows Shimizu to keep wood prominent in the living spaces people actually experience, while relying on reinforced concrete joints for workability and seismic performance. Those joints also limit thermal conductivity and help delay the burning of wooden columns during a fire—addressing the two classic objections to scaling timber.

Shimizu’s Hokuriku Branch office, completed in April 2021, shows what this looks like when it becomes a real building, not a lab concept. The project achieved ZEB (net Zero Energy Building) status, with proactive installation of hydrogen energy utilization systems and other advanced energy-saving technology. Inside, the space is intentionally expansive, and the atrium’s coffered ceiling—built with fire-resistant wood paired with steel beams—makes the point visually: this is wood construction designed for the modern code era, not the pre-industrial one.

That ability to execute comes from a capability Shimizu has protected for more than a century. Since Tokyo Mokkoujou Arts & Crafts Furnishings opened in 1884, workers have honed and passed down woodworking skills inside the company. Today, Shimizu has the only factory among Japan’s major construction companies that offers advanced woodworking technology and skills—an old advantage that suddenly matters again.

And the environmental case is hard to ignore. Shimizu says that using a wood hybrid structure can reduce CO2 emissions generated during construction by 20% or more compared with a same-size steel-structure office building. In a world of tightening carbon mandates—and the subsidies that often follow—this isn’t just good corporate citizenship. It’s positioning.

Shimizu has been building credibility in this direction for years. It designed and built what it describes as the first zero energy building (ZEB) in Japan: the Seicho-no-Ie’s Office in the Forest, completed in 2013. The message wasn’t abstract. It was proof that aggressive environmental targets could be met without sacrificing functionality.

In a way, the strategic circle really does close here. After 220 years, Shimizu is still doing what it has always done: taking a material, a set of constraints, and a moment in history—and figuring out how to build the next era anyway.

X. Porter's Five Forces & Hamilton's Seven Powers Analysis

By this point in the story, we’ve seen Shimizu in three different worlds: temples and palaces, LNG tanks and nuclear facilities, and now robots and moon bases. The question for investors is simpler than all that history: what does Shimizu’s competitive position actually look like today—and how durable is it?

Two frameworks help bring the picture into focus: Porter’s Five Forces for industry structure, and Hamilton’s Seven Powers for the sources of lasting advantage.

Porter's Five Forces Analysis:

1. Threat of New Entrants: LOW

Japan has an enormous number of authorized construction companies—more than 465,000—but the top of the market is dominated by a small club: the Super Zenecon, the Big Five general contractors—Obayashi, Taisei, Kajima, Shimizu, and Takenaka. Major companies account for about 30% of the overall construction market, and the Big Five alone account for around 15%.

Breaking into that tier is brutally hard. It’s not just capital and equipment. It’s regulation, reputation, and relationships—especially the trust needed to win huge, high-stakes projects where delays and failures are unacceptable. The keiretsu-style ecosystem of subcontractors, suppliers, and financiers adds another layer of inertia. Newcomers can compete on smaller projects, but to compete head-to-head with the Big Five, you need decades of track record and institutional capability. That’s not something you can buy off the shelf.

2. Bargaining Power of Suppliers: MODERATE

In construction, the most important “supplier” is labor—and Japan’s labor situation is the constraint that keeps tightening. The skilled workforce is aging, fewer young workers are entering the trades, and the people with the deepest expertise are increasingly difficult to replace.

Materials matter, too, especially when prices swing. Shimizu has faced the same pressure as the rest of the industry: construction material and energy costs rose sharply amid the situation in Ukraine, and that volatility has directly hit profitability. When your projects are large, long-duration, and fixed-price, supplier-side shocks don’t just sting—they can wipe out the margin.

3. Bargaining Power of Buyers: MODERATE to HIGH

On major public works, government clients have leverage. On big private-sector builds, large corporations can negotiate hard. In both cases, buyers know the Big Five want marquee projects and long pipelines.

But buyer power isn’t absolute. On complex projects that require specialized expertise, deep engineering resources, and the ability to manage risk at scale, the field narrows fast—and the Big Five regain leverage. The client can negotiate, but they also can’t afford to choose the wrong contractor.

4. Threat of Substitutes: LOW

There’s no substitute for “having a bridge” or “having a hospital.” The substitute threat is more about methods than outcomes: modular construction, prefabrication, 3D printing, and other approaches that can change how buildings get delivered and who captures value.

Shimizu’s robotics and BIM-driven job sites fit here as a defensive play. If the work is going to be reshaped by industrialization and automation, Shimizu wants to be shaping it—not reacting to it.

5. Industry Rivalry: HIGH but MANAGED

Competition among the Big Five is intense, but it has also been unusually stable. The same set of super general contractors has remained at the top for decades, with similar company scale and comparable sales ranges.

And then there’s the part you can’t ignore: historically, rivalry has often been “managed,” not purely market-driven, as the bid-rigging scandals demonstrated. That management can support stability, but it comes with a cost—regulatory scrutiny, legal exposure, and reputational risk that can flare up at the worst time. The pressure to compete is real, and the pressure to prove compliance is only getting stronger.

Hamilton's Seven Powers Analysis:

1. Scale Economies: MODERATE. Construction doesn’t behave like software; it’s still project-by-project. But scale shows up where it counts: R&D, equipment investment, specialized engineering talent, and the overhead needed to run massive, complex programs. The Big Five can fund capabilities that smaller firms can’t.

2. Network Effects: LIMITED. There’s no classic user-driven flywheel. But there is a relationship network: subcontractors, suppliers, partner firms, repeat clients, and internal talent pipelines. Those relationships can become self-reinforcing over time, even if they don’t look like Silicon Valley “network effects.”

3. Counter-Positioning: PRESENT. Shimizu’s push into Smart Site robotics, NOVARE, and frontier research creates a capability stack that competitors can’t copy overnight. Even if rivals choose to match the strategy, they still have to build the systems, culture, and execution muscle from scratch.

4. Switching Costs: MODERATE. On paper, a client can hire another contractor. In practice, repeat projects create real friction: new teams, new processes, new risk. For high-consequence work, many clients prefer continuity with a proven performer.

5. Branding: SIGNIFICANT. In construction, “brand” means reliability under pressure. Shimizu’s multi-century track record—temples, palaces, national infrastructure, and major landmarks—creates trust that matters when a client is awarding a project that can’t fail.

6. Cornered Resource: PRESENT. Shimizu’s advanced woodworking factory—the only one of its kind among Japan’s major construction companies—and the accumulated craft knowledge in temple and shrine construction are resources that can’t be quickly replicated. Some capabilities take time, lineage, and repetition; Shimizu has that.

7. Process Power: DEVELOPING. Smart Site robotics, BIM integration, and AI-enabled workflows could become a real advantage if they translate into consistently better productivity and quality—not just demonstrations. The opportunity is there; the proof has to show up across many job sites, not one flagship project.

Competitive Position vs. Peers:

Within the Big Five, Shimizu’s profile is distinct: it’s the oldest, with the deepest roots in traditional craftsmanship, and it’s also making one of the most aggressive bets on technology-driven transformation. Kajima is known for civil engineering scale; Takenaka for design excellence; Obayashi and Taisei compete broadly across categories. Shimizu’s differentiator is the combination—heritage plus an explicit push to redefine how construction gets done.

Key KPIs for Investors to Monitor:

-

Gross Profit Margin on Construction: This is the clearest single read on pricing discipline, cost control, and execution quality. Shimizu’s stated 2030 mix target—65% of consolidated gross profit from construction and 35% from non-construction—makes margin trends especially important.

-

Non-Construction Revenue as % of Total: Shimizu aims for 35% from non-construction by 2030. The trajectory here will reveal whether diversification is becoming a real earnings engine or remaining a set of smaller side businesses.

-

Robot Utilization Metrics: The story on robotics only matters if it changes job-site economics. Track adoption, productivity improvements, and measurable labor savings attributed to automation. Shimizu has articulated a benchmark goal of a 70% or greater reduction in labor for tasks performed by its robots; investors can use that as a yardstick.

Bull Case:

Shimizu delivers on the “Smart Innovation Company” shift. Robotics meaningfully improves productivity as the labor shortage deepens. Real estate and green energy provide diversification and smoother earnings. Wood hybrid construction expands as demand for sustainable buildings rises. Shimizu’s brand, technical depth, and long-built relationships remain durable moats.

Bear Case:

Construction margins stay under pressure from labor and materials. Technology investments don’t produce repeatable productivity gains at scale. Bid-rigging scrutiny continues to generate legal and reputational drag. Diversification dilutes focus without delivering returns. Japan’s demographic decline shrinks domestic demand, making the core market harder every year.

Regulatory and Legal Overhangs:

The 2025 investigation into Shimizu BLC over condominium repair bid-rigging is a reminder that compliance risk isn’t “behind” the company—it’s something investors have to keep monitoring. Even when fines are modest relative to Shimizu’s scale, repeated scrutiny signals a deeper structural challenge in parts of the industry.

For long-term fundamental investors, Shimizu is ultimately a bet on execution: can a 220-year-old builder navigate demographic decline, operate profitably in a sector with recurring scandal risk, and successfully evolve into a technology-enabled infrastructure company? The heritage is undeniable. The ambition is clear. The hard part—as always in construction—is turning plans into outcomes.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music