Obayashi Corporation: Building Japan's Future from Tokyo Station to the Stars

I. Introduction: The Quiet Giant of Japanese Construction

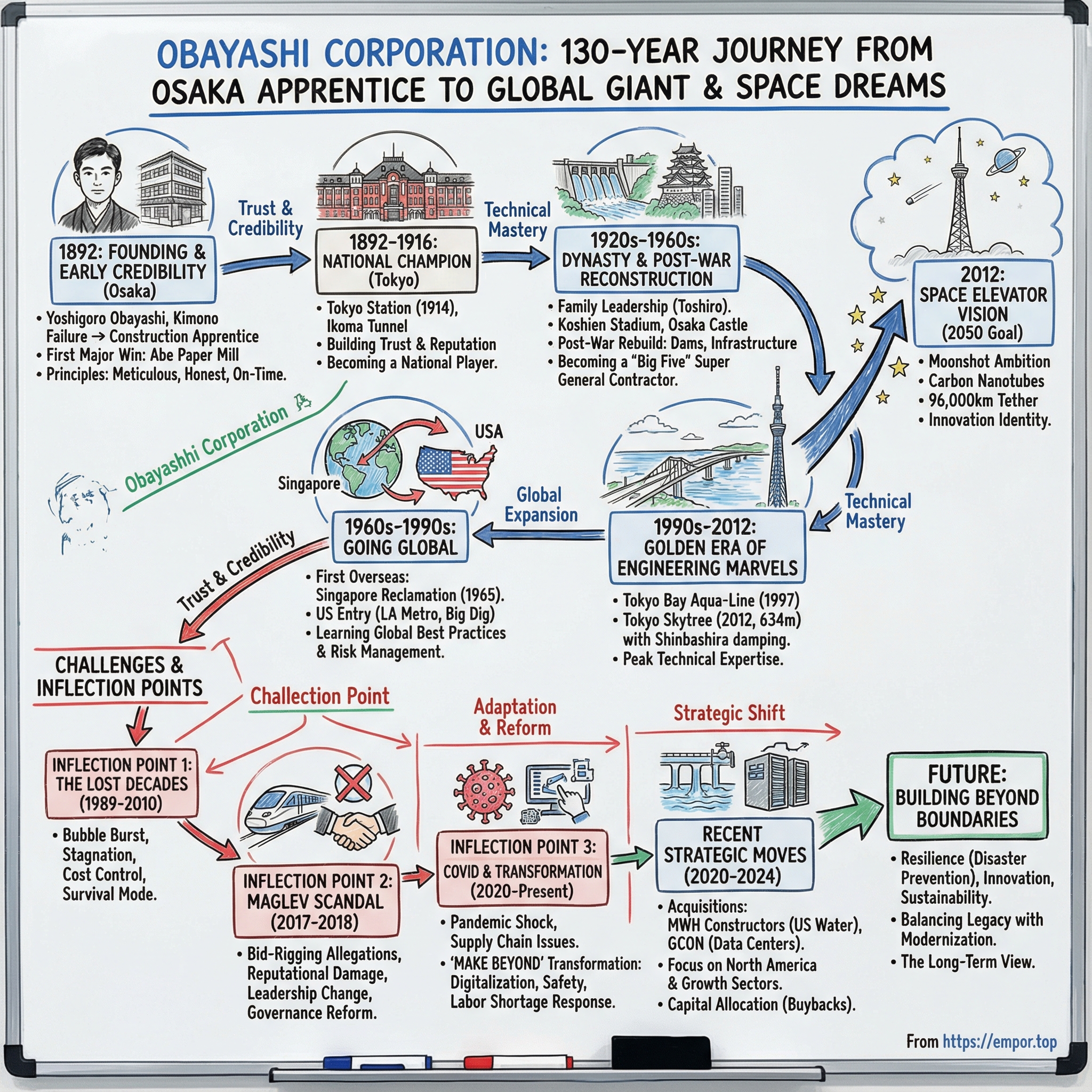

In Tokyo’s Marunouchi district, a red-brick building anchors the city like a promise kept. Tokyo Station—grand, European in its façade, obsessive in its symmetry—has funneled emperors, prime ministers, and millions of commuters through its corridors since 1914. Most of them never stop to wonder who built it. But that station is more than a landmark. It’s the signature early proof point of a company that would spend the next century quietly becoming one of the most formidable builders on Earth.

That company is Obayashi Corporation—one of Japan’s “Big Five” general contractors, alongside Shimizu, Takenaka, Kajima, and Taisei. In 2018, Engineering News-Record ranked Obayashi 15th on its Top 250 Global Contractors list, the highest placement among Japanese contractors.

Obayashi’s story is quintessentially Japanese: patient, methodical, generational. It’s enormous by any measure—around $17.5 billion in annual revenue in 2025 and a market capitalization hovering near $12 billion. But this isn’t a Silicon Valley tale of blitzscaling and disruption. It’s the slower, more durable kind of dominance: a 130-year-old firm that survived war, earthquakes, economic collapse, and scandal—and still found room to publicly sketch out a plan to build a space elevator.

That’s the puzzle at the center of this episode. How does a construction company founded in the final years of Japan’s feudal era stay not just relevant, but elite? What do you do when your industry’s operating system includes relationship-driven practices the modern world calls corruption? And what does it say about a company—best known for concrete, steel, and deadlines—when it starts talking about carbon nanotubes stretched 96,000 kilometers into space?

Along the way, Obayashi helped shape modern Japan’s skyline and infrastructure. Its resume includes the Kyoto Station Building, the Tokyo Broadcasting System (TBS) Center, and the Tokyo Skytree. It also operates far beyond Japan, with dozens of subsidiaries and affiliated companies spread across Asia, Europe, the Middle East, Australia, and North America.

Underneath all of that scale are the themes that run through Japan’s modern history itself: family legacy colliding with corporate professionalization; engineering excellence as a form of national identity; the tension between old networks and global competition; and a strangely consistent mix of conservatism and moonshot ambition.

To understand how Obayashi became Obayashi, we start where so many enduring stories start—not with a triumph, but with a young man who failed at selling kimonos.

II. Founding Story: From Kimono Shop Failure to Construction Empire (1864–1892)

Picture Osaka in 1875: a city mid-reinvention. The Tokugawa shogunate had fallen just a few years earlier, and Japan was sprinting from feudal isolation toward modern industry. In that turbulence, an eleven-year-old boy named Yoshigoro Obayashi stepped into the working world the way many Osaka merchant sons did—by apprenticing.

Yoshigoro, born in Osaka in 1864 near the end of the Edo period, started as an apprentice at a kimono store. By 18, he did what the model employee was supposed to do: he opened his own shop.

And it didn’t work.

Post-Restoration Japan was economically rough, and the kimono trade was beginning to feel pressure as Western clothing gradually crept into daily life. Yoshigoro’s shop lasted less than six months before he had to shut it down.

At 19, he made the decision that set everything else in motion. He left retail behind and moved into civil engineering and building construction—because if Japan was going to remake itself, someone would have to pour the foundations.

His entry point wasn’t a classroom. It was an apprenticeship with Shojiro Sunasaki, a contractor tied to the Imperial Household Ministry. The timing was perfect. The capital had moved from Kyoto to Tokyo, and the state was pouring resources into projects that carried both symbolism and scale—like work connected to the Imperial Palace. For a young man hungry to learn, it was a front-row seat to the new Japan: materials, methods, and the emerging blend of Western techniques with Japanese execution discipline. He also learned something just as important—how to manage high-stakes work for demanding clients.

After completing a five-year apprenticeship, Yoshigoro returned to Osaka to find a country that suddenly needed builders everywhere. Companies were forming, industries were mechanizing, and factories and offices had to rise fast. Railroads and ports expanded. The Meiji government’s push to strengthen the nation and promote industry wasn’t abstract policy—it was scaffolding, brick, steel, and schedules.

Then came the contract that made it real.

On January 18, 1892, Yoshigoro won a major job: building a new factory for the Abe Paper Mill, owned by the Abe family, wealthy merchants from Omi Province. Seven days later—January 25, 1892—he opened the Obayashi Store. He was 27. This wasn’t just a new job. It was the start of a company.

That Abe Paper Mill win wasn’t a fluke. It revealed a formula Yoshigoro would lean on again and again: earn trust with established merchant families, deliver exactly what you promised, and turn each finished project into the credential for the next one. Within a year, Obayashi was winning work with spinning companies that would go on to become major names in Japanese industry.

So what separated Yoshigoro from the swarm of contractors chasing Meiji-era growth? He articulated principles that were simple, brutal, and effective: be meticulous; fulfill responsibilities; deal honestly; hit deadlines; keep prices competitive. In a market where quality varied wildly and reputations were fragile, those weren’t slogans. They were a strategy for survival—and, eventually, dominance.

Obayashi began, in other words, not with a breakthrough invention or a pile of capital, but with something more durable: credibility. And once you understand that, the next century of the story starts to make a lot more sense.

III. The Making of a National Champion: Tokyo Station and Early Reputation (1892–1916)

By the early 1900s, Obayashi had outgrown its Osaka roots. Spinning mills and industrial facilities had given the company a reputation for getting hard work done on time and to spec. But if Yoshigoro’s firm wanted to become a national name, it had to win in the place where reputations were minted: Tokyo, the new imperial capital.

The opening came through a project so symbolic it was practically a declaration of modernity. Construction of Tokyo Central Station had been suspended during the Russo-Japanese War. When the project restarted, Obayashi-gumi was invited in 1908 to bid for the job. The building that opened in 1914 would later be known simply as Tokyo Station.

The architect was Kingo Tatsuno, one of the Meiji era’s leading designers, and the station was meant to look like a country stepping onto the world stage. European-inspired on the outside, rigorously executed on the inside, it became a showcase not just of design, but of construction capability. The finished station rose three stories and used an extraordinary amount of red brick—8.9 million of them.

For an Osaka-based contractor, winning Tokyo Central Station was a career-making leap. It turned Obayashi from “strong regional builder” into “national player,” and it opened the door to a long run of projects across the Tokyo region.

And Obayashi didn’t stop at landmark buildings. In 1911—the same year it was commissioned for Tokyo Central Station—it also signed a contract with Osaka Electric Railway to do something very different: drive a tunnel through the Ikoma mountain range separating Osaka and Nara. The Ikoma Tunnel was 3,388 meters long, the longest double-track tunnel in Japan at the time, and it fought back the whole way. Engineers faced soft ground, spurting groundwater, and in 1913, a devastating cave-in. Still, after three years of work, the tunnel was completed in 1914.

Taken together, Tokyo Central Station and the Ikoma Tunnel showed the full range of what Obayashi was becoming: not just a builder of prominent structures, but a contractor willing to absorb risk, solve technical problems, and finish jobs that could break less disciplined firms. The cave-in didn’t just test the company—it sharpened capabilities that would matter for decades.

Then, in January 1916, as the company’s profile was rising, Yoshigoro Obayashi died at 52. The presidency passed to Yoshio Obayashi, Yoshigoro’s successor, who at the time was a 22-year-old student at Waseda University’s Faculty of Commerce.

On paper, that sounds like a fragile moment: a founder gone, and a young successor still in school. In practice, it revealed what Yoshigoro had really built. Employees rallied to carry the company through the transition, and Obayashi-gumi kept its momentum. By the time the firm moved to modernize its structure, it had more than 200 employees behind it.

That modernization became official in December 1918, when Obayashi-gumi was incorporated as Obayashi Corporation. The new company was organized into six departments—general affairs, accounting, construction, lumber, design, and sales. An in-house design department was a notably ambitious move for the era. So was the employee stock ownership system the company put in place—unusual, even startlingly forward-thinking, for the time.

Obayashi was still a family-founded company. But it was no longer run like a small family shop. It was building the institutional muscle to take on larger, more complex work—and to keep doing it long after the founder was gone.

IV. Family Dynasty and Post-War Reconstruction (1920s–1960s)

Through the interwar years, Obayashi turned its early breakthroughs into something rarer: staying power. After Tokyo Central Station put the company on the national map, it followed with projects that signaled range, not just scale—work like Hanshin Koshien Stadium and the reconstruction of the Main Tower of Osaka Castle. These weren’t merely big jobs. They were public stages. Each one said, in a different way, Obayashi could be trusted with what Japan cared about.

Koshien Stadium, completed in 1924, quickly became one of the country’s most cherished venues—especially as the home of the annual high school baseball tournament that still grips Japan each summer. And Osaka Castle’s reconstruction tied Obayashi to the nation’s deeper story. It wasn’t just building for the future; it could also rebuild the past, handling projects with cultural weight as confidently as industrial ones.

Then the 1930s arrived, and Japan’s trajectory toward militarism pulled heavy industry—and builders—into the machinery of war. Obayashi played a prominent role supporting Japan’s military effort during the war with China and then World War II. When the war ended, the company entered a different kind of transition: less about engineering and more about legitimacy, continuity, and survival in a new Japan.

In 1946, Yoshiro Obayashi handed leadership to his son-in-law, who took the Obayashi name: Toshiro Obayashi. It was a pragmatic succession move—and a symbolic one, too, signaling stability at a moment when the country, and its institutions, were being remade under American occupation. Toshiro would remain at the head of the company until his death in the early 2000s, giving Obayashi an extraordinary run of consistent leadership through Japan’s most turbulent and transformative decades.

The post-war years were a national rebuild, measured in concrete and urgency. Obayashi focused on restoring the fundamentals of public life—government offices, schools, hospitals—while also taking on dam projects that helped pioneer electrical power development. Japan wasn’t only repairing what had been destroyed; it was laying the groundwork for an economic miracle, and reliable electricity was non-negotiable.

That shift became clearer in 1956, when Obayashi built its first hydroelectric dam—an inflection point in its evolution into a major civil engineering player. Dam construction was unforgiving work: remote sites, massive volumes of concrete, water that never stops trying to win. Contractors that could deliver here earned a different kind of credibility.

By the 1960s, Obayashi had not only re-established itself among Japan’s leading builders, it was also pushing to become a technology developer, not just a contractor. In 1961, for instance, it developed its own Wet Screen technology for building concrete walls, based on a method originally developed in France. It was a sign of how the big contractors were differentiating: not only by winning bids, but by building proprietary know-how.

Around this same time, Japan’s construction industry settled into a structure that would define it for decades. Despite the country having hundreds of thousands of licensed construction companies, a small group of giants dominated the top end of the market: Obayashi, Taisei, Kajima, Shimizu, and Takenaka. These “Super General Contractors” operated across a wide range of project types and, by sheer scale and capability, accounted for a meaningful share of Japan’s total construction market.

That dominance came with real advantages. The Big Five could fund research and development, build deep benches of specialized engineering talent, and take on mega-projects that smaller firms simply couldn’t attempt. But the structure also carried a built-in vulnerability. For decades, the system was partly supported by “dango”—informal coordination that helped allocate work among major players. It was long treated as normal business practice in Japan. Later, it would be condemned as illegal bid-rigging, and it would become one of the defining fault lines in the industry’s modern era.

V. Going Global: The First Japanese Contractor Abroad (1960s–1990s)

By the time Japan’s high-growth era was in full swing, Obayashi had a problem that only national champions get to have: the company had mastered the home market. The next question was where to point that capability. The answer, unexpectedly, started with sand and shoreline—land reclamation in Singapore.

Obayashi’s first steps overseas began in the 1950s, and in 1956 the Singapore government tapped the company for a major land reclamation project. It wasn’t a quick win. The effort stretched for decades, and the project was finally completed in 1984. But it gave Obayashi something far more valuable than a single contract: a durable foothold outside Japan, in a place that would soon become one of Asia’s most intense building laboratories.

The timing turned out to be perfect. Obayashi established its Singapore presence in 1965—the year Singapore became independent. As the city-state set out to transform itself, it needed exactly what Obayashi had become elite at delivering: reclaimed land, civil infrastructure, and the kind of complex, schedule-driven construction that turns national ambition into physical reality.

Obayashi didn’t stop there. In 1964 it entered Thailand, opening its first overseas subsidiary. And over the following decades, the company built a portfolio that reads like a world tour of difficult civil engineering: Bangladesh’s Maghna Gumti Bridge, completed in 1995; segments of Los Angeles’ Metro Rail; Boston’s Central Artery Tunnel—the “Big Dig”—completed in 1996; Singapore’s Esplanade Bridge, completed in 1997; additional land reclamation at Changi East; and Australia’s M2 Motorway in New South Wales, also completed in 1997. It also completed landmark buildings abroad, including London’s Bracken House in 1991.

The United States, though, was the real stress test. The Los Angeles Metro work and the Big Dig weren’t just big projects—they were a proving ground in one of the most competitive, contract-heavy, and litigation-prone construction environments in the world. This was a different planet from Japan’s relationship-driven system. To survive, Obayashi had to learn new muscles: how to operate inside American procurement rules, manage risk under different contract structures, and build credibility in a market that doesn’t care who you are back home.

True to form, Obayashi didn’t charge in recklessly. It expanded the way it builds: step by step. In 1978, James E. Roberts-Obayashi Corporation was established as part of its U.S. footprint. Later, in 2007, Webcor joined the Obayashi Group in the U.S. The company added a Canadian platform as well: Obayashi Canada Ltd. was established in 2011, and Kenaidan Group Ltd. joined the group in Canada.

By the 1990s, Obayashi was no longer simply “a Japanese contractor with overseas jobs.” It was starting to look like a global contractor, period. A milestone came at the end of the decade when it won the contract to build Stadium Australia for the 2000 Sydney Olympics, completed in 1999—exactly the kind of high-visibility, high-expectation project that signals you belong on the world stage.

And importantly, the overseas push wasn’t separate from what was happening at home. Obayashi was still participating in major projects in Japan—Kansai International Airport, the Tokyo Bay Aqua-Line, the Akashi-Kaikyo Bridge, and major urban landmarks like Shinagawa Intercity and Kyocera Dome Osaka—while also widening its operational range abroad in response to growing international demand.

The point wasn’t just diversification. Going global forced Obayashi to professionalize in ways Japan’s traditional system didn’t always demand: more legal sophistication, more cross-cultural management, and different approaches to safety and quality. Those capabilities would compound over time—and they would matter even more when the easy growth years ended.

VI. The Golden Era: Mega-Projects and Engineering Marvels (1990s–2012)

Japan’s late-1980s bubble unleashed an infrastructure binge that didn’t end when the asset prices crashed. The money vanished, but the projects kept moving—partly as stimulus, partly as national ambition, and partly because once you’ve started boring tunnels and sinking foundations, stopping is its own kind of catastrophe.

A perfect emblem of that era was the Tokyo Bay Aqua-Line. After more than two decades of planning and nearly a decade of construction, it opened on December 18, 1997, in a ceremony attended by then–Crown Prince Naruhito and then–Crown Princess Masako. The final price tag was staggering—¥1.44 trillion, about US$11.2 billion at the time—but what Japan got was something no one could dismiss as ordinary.

The Aqua-Line is an expressway that crosses Tokyo Bay using a bridge-and-tunnel hybrid. It links Kawasaki in Kanagawa Prefecture to Kisarazu in Chiba Prefecture. End to end, it runs 23.7 kilometers—anchored by a 4.4-kilometer bridge and a 9.6-kilometer tunnel beneath the bay, one of the longest underwater road tunnels in the world.

More than the numbers, it was the execution that mattered. From design through construction, the Aqua-Line became a showcase for the most advanced methods and know-how Japan’s builders could deploy at the time. New techniques were developed and used on the job, and the whole undertaking earned a nickname that captured the scale of the challenge: the “Apollo project of civil engineering.”

The Aqua-Line was born in bubble-era confidence, when no crossing seemed too bold and no schedule too audacious. Plenty of critics asked whether Japan really needed another route across the bay. But the engineering achievement was undeniable. Obayashi’s involvement was a clear signal: this was a contractor that could do marine construction and tunneling at the highest level, on projects where failure simply wasn’t an option.

Then came the project that would define Obayashi for the new century: Tokyo Skytree.

TOKYO SKYTREE® rose in Tokyo’s Sumida Ward—near Narihirabashi and Oshiage—and opened in 2012. At 634 meters, it became one of the tallest towers in the world. It wasn’t just big; it was technically punishing. Obayashi brought proprietary technologies to the job, because a structure that tall in Tokyo doesn’t just have to stand up—it has to stay calm when the ground tries to throw it off balance.

The effort behind it was immense. The project required years of design work, nearly four years of construction, and a workforce counted in the hundreds of thousands. For perspective, Tokyo’s previous height icon, the 333-meter Tokyo Tower, had been completed back in 1958. Skytree wasn’t an iteration. It was a new class of problem.

What made it especially Obayashi wasn’t only the height—it was the idea at the center of the tower. Skytree’s structural concept drew on a technique from traditional Japanese pagodas: the shinbashira, a central pillar used to help buildings survive earthquakes. In Skytree, that ancient principle became a modern, steel-and-concrete system. At the core stands a 375-meter steel-reinforced cylinder, about 8 meters across and weighing roughly 11,000 metric tons. The bottom third is fixed to the surrounding structure. The upper two-thirds is deliberately not welded to the tower, allowing it to move.

That “floating” portion can swing, with oil dampers placed between it and the surrounding beams. In an earthquake, the shinbashira sways at a different frequency than the main structure, counteracting the motion and helping the tower return to stability—reducing lateral movement by as much as 50%.

It was a philosophy captured in steel: respect the old wisdom, then engineer it forward until it can carry something no one in the past could have imagined.

And the system didn’t have to wait for opening day to prove itself. On March 11, 2011, the Great East Japan Earthquake struck while Skytree was still under construction. The shake-reduction technology performed as intended. The structure wasn’t damaged, and all staff on site were safe. Just a week later, on March 18, workers installed the lightning rod at the top, bringing the tower to its full height of 634 meters.

For Obayashi, it echoed an earlier moment in its history. Tokyo Station surviving the Great Kanto Earthquake in 1923 had cemented trust in the company’s workmanship. Nearly ninety years later, Skytree’s performance during the 2011 earthquake delivered the same message in a new form: in Japan, the highest compliment a builder can earn is that the ground can’t break what you made.

VII. The Space Elevator: Moonshot Thinking or Marketing Genius? (2012)

In February 2012—just months before Tokyo Skytree opened to visitors—Obayashi made an announcement that sounded less like a contractor’s update and more like a sci-fi cold open. The company said it intended to build a space elevator. Not a metaphor. A literal elevator from Earth to space—a concept engineers had been kicking around since the 1890s, and that everyone agreed lived comfortably in the “theoretically possible, practically impossible” bucket.

Obayashi’s vision was specific. It aimed for completion by 2050, with “climbers” capable of carrying 100 tons at a time. The system, as described, would hang on a 96,000-kilometer cable made from carbon nanotubes, anchored to a floating “Earth Port” about 400 meters in diameter, and stabilized by a massive counterweight—about 12,500 tons—out beyond geostationary orbit.

Even if you try to keep your feet on the ground, the specs pull your eyes upward. A tether stretching 96,000 kilometers. A floating platform the size of a small district. Cargo loads that sound more like shipping containers than satellites.

And the key point was this: until relatively recently, there wasn’t even a candidate material. Before 1991, nothing known could plausibly meet the strength-to-weight requirements for such a cable. Then physicist Dr. Sumio Iijima discovered the mechanism of the carbon nanotube—light, incredibly strong in theory, and suddenly the space elevator stopped being purely a novelist’s prop. In 2012, Obayashi packaged that possibility into what it called its Space Elevator Construction Plan: connect Earth and space by 2050.

The Skytree connection wasn’t subtle; it was the whole rhetorical move. Obayashi had just finished the world’s tallest tower, in the world’s most earthquake-demanding major city, and it wanted you to see the through-line. “Humans have long adored high towers,” project leader Satomi Katsuyama said. The implication was clear: if anyone could credibly talk about building upward at absurd scale, it was the company that had just done 634 meters the hard way.

Obayashi also painted a picture of how it might work operationally. It envisioned climbers traveling at around 150 kilometers per hour, reaching roughly 400 kilometers altitude—around the level of the International Space Station—in about two and a half hours. It even offered a comparison you could feel in your body: about the same as a Tokyo-to-Osaka Shinkansen ride.

Then came the money pitch. Rockets were—and are—expensive. Obayashi pointed to contemporary launch economics and suggested an elevator could slash the cost of getting cargo to space. The estimate circulating at the time contrasted SpaceX’s Falcon 9 cargo costs—around $1,227 per pound—with a hypothetical $57 per pound via elevator. If true, that wouldn’t be a margin improvement. That would be a rewrite of what’s economically feasible in orbit.

Of course, the skeptics showed up immediately, because they had to. As one space elevator researcher, Christian Johnson, put it: if you tried to do it with steel, you’d need more steel than exists on Earth. Carbon nanotubes were the obvious alternative—lighter and tougher than steel—but the engineering reality was brutal. The longest nanotube ever made at the time was only about two feet long. In other words: the “material” existed, but the “manufacturing” didn’t.

Yoji Ishikawa, from Obayashi’s future technology creation department, later told Business Insider that construction was unlikely to start in 2025, a date that had been floated early on. But he emphasized the company was still at work: research and development, rough design, partnership-building, and promotion. Johnson, for his part, captured the vibe perfectly. It was “sort of a kooky idea,” he said—while also acknowledging that real scientists were genuinely invested in making it happen.

Obayashi’s own stance was measured, almost deliberately so: current technology wasn’t sufficient yet, but the plan was realistic, and meant as a stepping stone toward eventual construction.

And that’s the real story here. The space elevator announcement wasn’t just about an elevator. It was about identity.

It told future engineers and project managers: this is a place where your career doesn’t have to top out at “another office tower.” It told the market: we’re not only a firm that executes; we’re a firm that imagines. And it bought Obayashi something that traditional contractors struggle to earn—global attention for ambition, not just competence.

Whether the elevator ever gets built matters. But what matters more is what Obayashi revealed about itself in the act of proposing it: a company grounded in deadlines and concrete that still wants, publicly, to be the kind of builder that takes humanity’s next physical step.

VIII. Inflection Point #1: The Lost Decades and Industry Recession (1989–2010)

The space elevator announcement in 2012 landed in a strange place in Obayashi’s timeline. It sounded like pure forward motion. But the company had just spent twenty years doing something far less glamorous: surviving.

Japan’s asset bubble burst in 1989, and construction—an industry that had lived off easy money and constant development—took the hit immediately. Public works budgets tightened as government debt mounted. Private projects dried up as corporations slammed the brakes on capital spending. And when there are fewer jobs to go around, bids turn into knife fights. Contractors started cutting prices to the bone just to keep crews busy and equipment moving.

That stagnation wasn’t a short downturn. It dragged on through the 1990s and deep into the 2000s, only beginning to ease years later, helped in part by the reconstruction surge after the Great East Japan Earthquake in 2011. But from 1989 to 2010, Obayashi and its peers were operating in a market that felt structurally smaller every year. The response had to be practical: tighter operations, sharper cost control, and a relentless focus on efficiency in an environment where “winning the job” often mattered more than enjoying the margin.

And the headwinds weren’t just economic. Japan’s demographic decline began to show up in the demand curve. An aging population meant fewer new homes, fewer schools, fewer facilities built for growth. Yes, infrastructure from the high-growth decades was aging—but the country couldn’t simply replace everything at the pace it was originally built. The market was shifting from expansion to maintenance, and that’s a very different kind of construction economy.

The labor side tightened too. More than a third of craft workers were over 55, and retirements outpaced new entrants. Even when work existed, capacity became the constraint. Overtime curbs introduced in April 2024 would later squeeze available man-hours further, pushing major contractors toward autonomous earth-moving fleets, remote-controlled cranes, and AI-driven scheduling—tools designed to keep sites productive with fewer people and less time.

Meanwhile, the industry’s unwritten rules were coming under pressure. For decades, Japan’s biggest builders operated in a world shaped partly by dango—informal coordination that allocated work and kept competition from turning destructive. Over time, that system attracted harsher scrutiny. Laws tightened. Expectations changed. And between 2006 and 2007, misconduct incidents tied to public works contracts hit Obayashi’s reputation, forcing a stronger emphasis on compliance and corporate culture.

Then the 2008 global financial crisis arrived. Lehman collapsed, markets froze, and what had looked like smart international diversification suddenly meant exposure to economies in freefall. Obayashi had to revise strategies and plans yet again, not because it wanted to, but because the ground had shifted under every builder in the world.

So how did the Big Five make it through two lost decades?

They did three things. First, they kept investing in technology—earthquake-resistant systems, tunneling expertise, and automation—creating a moat smaller contractors couldn’t afford to dig. Second, they diversified geographically, leaning into regions that were still building, especially in parts of Southeast Asia. Third, they consolidated strength at home: as weaker players failed or merged, the survivors didn’t necessarily become bigger in an absolute sense, but they became harder to dislodge.

By the time Obayashi talked about a 96,000-kilometer tether to space, it wasn’t just chasing attention. It was signaling that it had endured the most punishing kind of business environment: the slow one.

IX. Inflection Point #2: The Maglev Bid-Rigging Scandal (2017–2018)

The space elevator was Obayashi looking skyward. But a few years later, the company was pulled hard back to Earth—by the oldest gravity in Japanese construction: collusion.

In late 2017, Tokyo prosecutors raided the headquarters of Obayashi and Taisei on suspicion of antitrust violations connected to work on the Linear Chuo Shinkansen, the maglev line being built by Central Japan Railway. Investigative sources said Obayashi later admitted conspiring with three other major general contractors to coordinate orders.

This wasn’t a small contract dispute. The Linear Chuo Shinkansen was—and remains—one of the most ambitious infrastructure projects in the world: a magnetic levitation rail line intended to connect Tokyo, Nagoya, and eventually Osaka. The first phase, linking Tokyo and Nagoya, was expected to cut travel time to about 40 minutes from roughly 100 minutes, with an opening targeted for 2027 at the time. The larger project budget being discussed publicly was around $80 billion.

The alleged scheme was exactly the kind of behavior Japan had been trying, for years, to stamp out. Work on the line was being executed largely through joint ventures led by the major contractors. Prosecutors alleged the four builders coordinated bidding so each would end up with a similar share of the work. One focal point of the case was the construction of an emergency exit for the maglev at Nagoya station.

Arrests followed. In early 2018, Tokyo prosecutors arrested current and former senior officials at Kajima and Taisei, alleging they colluded with Obayashi and Shimizu on bids in 2014 and 2015. The story wasn’t just about a single project; it was about a system. Bid-rigging had long been described as entrenched in construction and other sectors, surviving despite crackdowns, tightened legislation, and repeated public pledges to eliminate it.

For Obayashi, there was an extra layer of irony. The company had already tried to harden itself against this. In 2006, it required managers to sign pledges to comply with antitrust laws. In 2007, top management resigned following a separate public works scandal. The reforms were real—but the maglev case showed how persistent the old incentives and habits could be.

Obayashi’s response was notably tactical. Japan’s Fair Trade Commission operates a leniency program: the first company to report and admit wrongdoing in a bid-rigging case can generally receive full immunity from fines. In the maglev investigation, Obayashi was reported to have sought leniency—effectively choosing cooperation over denial.

Executives from Obayashi and Shimizu told prosecutors that the four companies had fixed the bidding process to divide up contracts along the line, and they also admitted Anti-Monopoly Act violations to the Fair Trade Commission.

The fallout landed where it usually does in corporate Japan: at the top. On January 23, Obayashi announced that its president, Toru Shiraishi, would resign effective March 1, to be replaced by director Kenji Hasuwa.

The legal outcome came later. On October 22, the Tokyo District Court ordered Obayashi to pay $1.8 million in costs and fines, and Shimizu $1.6 million, for violating Japan’s Anti-Monopoly Act. The judge said the collusion had “prevented fair and free competition.” Both companies admitted their involvement.

The money itself was not the point. Next to Obayashi’s scale, the fines were small. The real damage was reputational—and structural. The scandal forced another public reckoning with behaviors the industry had treated as normal for decades, and it triggered leadership change that signaled the company understood just how exposed it had become.

And Obayashi’s leniency move mattered. By cooperating first, it reduced its own downside while leaving competitors—particularly those that initially denied wrongdoing—facing more intense scrutiny. It was sophisticated crisis management. It was also an implicit admission that the old way of doing business was now an existential liability.

X. Inflection Point #3: COVID, Corporate Transformation, and Medium-Term Business Plan (2020–Present)

The maglev scandal forced Obayashi to look inward. COVID forced it to rewire how it operated.

In October 2020, Obayashi launched a corporate transformation program—an explicit admission that incremental improvement wouldn’t be enough. The timing wasn’t subtle. Under its five-year Medium-Term Business Plan 2017, the company had been building momentum and logged record-high profits in FY2019.3. Then FY2021.3 hit, operating income fell sharply, and the pandemic scrambled the assumptions underneath the business: how people worked, how projects were staffed, how supply chains held together, and how long the economic drag might last.

The transformation program put four priorities on the table.

First: safety and quality—doubling down after years in which the industry’s reputational risks had become painfully clear.

Second: earnings power and cash flow—because in construction, liquidity is survival.

Third: preparing for the revised Labor Standards Act, which tightened constraints on work hours and forced contractors to rethink how they deliver schedules with finite labor.

Fourth: rebuilding relationships across the supply chain through “co-creation”—less arm’s-length subcontracting, more partnership, more coordination.

But the deeper point was what came next. Obayashi said it would also overhaul the management foundations meant to carry the company through its next phase: human resources and organization, business processes, digitalization, and technology. In other words, not just “do the work better,” but “become a different kind of company while still doing the work.”

That reinvention was driven by an uncomfortable truth: Obayashi had been expanding its domains and global footprint for years, trying to grow beyond the traditional boundaries of a general contractor. Yet to outsiders, the image barely changed. It was still seen as the same old civil engineering and construction firm—great at concrete, not necessarily where you’d go to build a career in software, data, or sustainability. And that image became a real constraint as open innovation became table stakes and competition for talent intensified.

So Obayashi put a new flag in the ground: “MAKE BEYOND: Transcending the Art and Science of Making of Things.” It reads like branding—and it is—but it also points to a practical problem the company had to solve. If the future of construction is digital workflows, automation, and decarbonization, then a builder has to recruit the people who build those systems. And those people have options.

Then, just as the world began to reopen, a new set of pressures arrived. In FY2022 and FY2023, profitability took hits from soaring raw material prices and higher personnel costs. Construction input prices surged—an increase sharp enough to squeeze margins even for top-tier contractors—made worse by currency depreciation.

By FY2025, the tone shifted again. Obayashi revised its consolidated operating income forecast upward by ¥43.0B to ¥165.0B, citing factors like change orders on large-scale projects, improved profitability through cost reductions at settlement in domestic building, and steady project execution. Reuters also reported parent-only financial highlights showing sales growth and a major jump in operating and net results.

The takeaway wasn’t that Obayashi “beat” the pandemic. It was that the company came out of the shock with a clearer operating philosophy: tighter project management, more disciplined negotiations, and a transformation agenda that treated labor constraints, cost volatility, and digital capability as core strategy—not side quests.

XI. Recent Strategic Moves: Acquisitions and New Frontiers (2020–2024)

The transformation program wasn’t just an internal tune-up. It came with a more outward-facing move: Obayashi started buying its way into where it believed the next decades of infrastructure spending would concentrate, especially in North America.

The headline deal was water.

In January 2024, Obayashi announced it had decided to acquire a 90% stake in MWH Constructors, a U.S. contractor focused on building water and wastewater treatment facilities. The stake was purchased from Oaktree Capital for €126 million.

MWH had spent more than 30 years building a reputation in water infrastructure. It operates through MWH Constructors and two wholly owned subsidiaries, Slayden Constructors and Methuen Construction, and it grew out of a water-focused engineering and construction organization with roots going back to 1820.

Strategically, the appeal is straightforward. Water is a long-cycle, high-necessity market—driven by aging systems, population growth, and the practical demands of climate adaptation. It’s also an area where spending tends to persist even when other construction categories slow. Obayashi’s view was that North American infrastructure and civil engineering demand should remain stable into 2025 and beyond, with particular strength in water treatment construction—exactly MWH’s lane.

The timing also matched the macro. In the U.S., the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA) and the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) injected fresh tailwinds into infrastructure construction, and Obayashi was positioning itself to capture that demand through acquisitions rather than trying to build a presence from scratch.

Obayashi also broadened its U.S. footprint through its subsidiary Webcor. The company announced that Webcor agreed to acquire 100% of the shares of GCON Inc. and two affiliated companies. GCON is a full-service construction management firm operating across ten states, including Arizona, with work spanning technology projects (data centers and semiconductor manufacturing), healthcare, aviation, commercial, higher education, and public works.

The logic here is less about traditional public infrastructure and more about the physical build-out required by the AI era. Demand for critical environments—especially data centers and semiconductor facilities—has been growing rapidly and is expected to keep growing. Arizona and other Southwestern states have become major investment hubs, and GCON brought a strong reputation in its home market, including retrofit work on semiconductor manufacturing facilities and a track record in colocation data center construction.

GCON, founded in 2003 and headquartered in Phoenix, describes its purpose as elevating the construction experience through dedicated partnerships and highly specialized teams. For Obayashi, it was a way to deepen exposure to one of the fastest-growing, most complex categories in U.S. construction—projects where schedule, precision, and execution discipline are the product.

Running alongside this expansion playbook was a second signal: Obayashi was also getting more assertive about capital allocation and shareholder returns.

In 2025, the company launched a share buyback program, repurchasing 14.56 million shares—about 2.04% of outstanding stock—for ¥29.99 billion. It also announced another repurchase authorization of up to 25,000,000 shares, representing 3.56% of issued share capital, for ¥40,000 million.

The funding story mattered as much as the buybacks themselves. Obayashi has been reducing cross-shareholdings—an old-line Japanese corporate practice often criticized as inefficient—and, in doing so, it expects to free up ¥243.8 billion in capital by 2027. The company has positioned those funds to be redirected toward digital transformation, human capital development, and higher-margin growth areas such as renewable energy infrastructure.

Put together, the acquisitions and the buybacks tell a coherent story: Obayashi was trying to modernize not only how it builds, but how it deploys capital—shifting away from legacy balance-sheet habits and toward a strategy built around targeted growth markets, discipline, and governance credibility.

XII. Myth vs. Reality: Understanding Obayashi's Competitive Position

Myth: Japanese construction is technologically stagnant.

Reality: Obayashi’s track record is almost the opposite of stagnant. It has kept putting money and talent into R&D, from earthquake engineering designed to reduce vertical seismic impact by as much as 75%, to the shinbashira-inspired damping system at the heart of Tokyo Skytree. Even the space elevator work—speculative as it is—signals a company that wants to be associated with frontier engineering, not just poured concrete and project schedules. And on the ground, the push into automation is less about flash and more about survival: robotics and AI-driven scheduling are direct responses to a shrinking workforce and tighter labor constraints.

Myth: The Big Five dominance means guaranteed profitability.

Reality: Being a “Super General Contractor” doesn’t grant immunity from the basic math of construction. In recent years, soaring material prices and a serious labor shortage have pushed costs up across the sector. Japan’s aging, shrinking population has made that labor shortage chronic, keeping productivity under pressure and driving labor costs higher.

The result is margin squeeze. The Big Five’s scale and reputation can help with winning work and, at times, negotiating price. But they still compete hard for major projects, and when costs move faster than contracts can absorb, even the giants feel it.

Myth: International expansion is the growth engine.

Reality: Overseas business matters, but it still sits behind Japan in both scale and, often, profitability. Deals like MWH and GCON clearly deepen Obayashi’s U.S. footprint and place it closer to durable demand in water infrastructure and complex commercial builds. But the home market remains the core profit center.

International growth also comes with a different playbook: different contracting norms, different risk allocation, and often thinner margins because competition is broader and disputes can be more expensive. Global scale is a strategic hedge, not a simple escape hatch.

Myth: The bid-rigging scandal represented aberrant behavior.

Reality: The maglev case wasn’t just a one-off embarrassment. It exposed practices that, for decades, were widely embedded in Japan’s construction ecosystem. They were illegal, but they were also, in many circles, treated as normal—habits built up over generations of relationship-driven dealmaking.

The uncomfortable question isn’t whether Obayashi got caught once. It’s whether the reforms that follow these moments truly change incentives and behavior—or whether they simply push the same conduct into harder-to-detect forms.

XIII. Bull Case and Bear Case for Investors

Bull Case:

For investors, the optimistic view starts with a simple idea: Japan still has plenty of reasons to build.

One is resilience. The Japanese government’s five-year acceleration plan for disaster prevention, mitigation, and national resilience includes roughly 15 trillion yen of investment. Tokyo has its own version of the same story through the Tokyo Resilience Project, with plans to spend around 15 trillion yen on infrastructure to strengthen the city’s disaster preparedness by the 2040s. In a country where earthquakes, typhoons, and flooding are recurring facts of life, “maintenance” often looks like major new work.

Then there’s the steady drumbeat of mega-events and mega-projects. The Tokyo Olympic Games in 2021 pulled forward demand. Looking ahead, large construction programs tied to World Expo 2025 in Osaka, continued work on the Chuo Shinkansen maglev line, and the Osaka Integrated Resort (IR) are expected to play a similar role in keeping top-tier contractors busy.

On competitive positioning, Obayashi’s advantage is less about a single breakthrough and more about compounding capabilities that are hard to copy. In Hamilton Helmer’s framework, you can see several of the “7 Powers” at work:

Scale Economies: As one of the Big Five, Obayashi can spread fixed costs—R&D, specialized equipment, deep technical benches—across a high volume of large projects. Smaller contractors can’t finance that kind of institutional capacity.

Process Power: Obayashi’s edge has been built over decades of repetition in the hardest categories: earthquake-resistant design, tunneling, and mega-project execution. Tokyo Skytree’s shinbashira-based damping system is a clean example of process innovation turned into real-world performance.

Switching Costs: On large, high-stakes projects, clients don’t rotate contractors casually. For government agencies and major corporations, changing builders is expensive, disruptive, and risky. Long-term relationships can create stickiness—especially when a contractor has proven it can deliver safely and predictably.

Layer on top the company’s push into the U.S. through water infrastructure (MWH) and complex commercial construction like data centers (GCON). Those categories are supported both by policy tailwinds like the IIJA and IRA and by secular demand from the buildout of AI and semiconductor infrastructure.

Finally, there’s a more shareholder-friendly tone in capital allocation. Obayashi has been reducing cross-shareholdings and executing share buybacks—signals that management is increasingly willing to optimize the balance sheet rather than simply preserve legacy structures. The company has also reiterated its stance of maintaining stable dividends over the long term and moving forward with its planned 100.0 billion yen share buyback.

Bear Case:

The cautious view starts where Japan’s macro reality always starts: demographics.

A shrinking, aging population is a long-term headwind for new-build demand. Fewer people ultimately means less need for incremental housing, commercial space, and expansion-driven public works. Government spending can cushion that for a while, but it’s hard to outrun the direction of the population curve forever.

Labor is the next constraint. With more than one-third of craft workers over 55 and retirements outpacing new entrants, capacity becomes a bottleneck even when demand exists. Automation can help at the margins, but construction remains stubbornly labor-intensive, especially on complex sites.

Zooming in with Porter’s Five Forces reveals where the pressure points can show up:

Supplier Power: When inflation hits, materials suppliers gain leverage, and contractors feel it immediately. The recent spike in construction input prices highlights how quickly margins can get squeezed when costs move faster than contract pricing.

Buyer Power: Government and quasi-government clients have pushed harder on competitive bidding and transparency. That reduces the ability to rely on pricing power or relationship-driven stability that characterized earlier eras.

Threat of Substitutes: Prefabrication and modular construction could chip away at parts of the traditional general contractor model over time. Adoption in Japan has been slower than in some markets, but the direction of travel is clear.

Competitive Rivalry: The Big Five may dominate, but that doesn’t mean they live in peace. They compete intensely for the best projects, and when margins are under pressure, the temptation to bend rules rises. The maglev bid-rigging scandal is a reminder of what can happen when contractors feel squeezed between demanding clients and tighter economics.

International expansion adds another layer of risk. Different legal systems, labor practices, procurement norms, and dispute dynamics mean that being elite in Japan doesn’t automatically translate into clean execution abroad. Growth overseas can diversify the business—but it can also import new forms of volatility.

XIV. Key Performance Indicators for Monitoring

If you want to track whether Obayashi’s transformation is really working, three metrics tell you most of what you need to know.

1. Operating Margin Recovery: The story of the last few years has been margin pressure—materials up, labor up, and the painful reality that fixed-price construction contracts don’t automatically adjust just because the world got more expensive. So the question now is whether Obayashi can claw profitability back.

The company has pointed to higher gross profit on completed construction contracts, driven by things like change orders on large-scale projects and better profitability at settlement in its domestic building business. It’s also cited steady progress on projects in hand, which supports both net sales and profit.

In plain terms: if Obayashi can consistently negotiate change orders when scope shifts and close out projects without giving back margin at the finish line, that’s a strong signal of both pricing power and execution discipline.

2. Order Backlog Growth: Construction companies don’t run on quarterly demand spikes. They run on backlog. It’s the forward-looking meter that tells you whether today’s workforce and equipment will still be earning revenue a year or two from now.

Obayashi’s new orders forecast is ¥1,200.0B, set to match current construction capacity. That figure is also down meaningfully from FY2024, when the company booked a larger slate of major projects.

But quantity isn’t the whole game. The quality of the backlog matters just as much. A smaller backlog with healthier margins and better risk protection can be far more valuable than a bigger backlog won through aggressive pricing.

3. Overseas Revenue Contribution: Obayashi’s push into North America—especially through MWH and GCON—only becomes real if overseas revenue grows and, just as importantly, if it grows profitably.

The company expects North America to remain stable for infrastructure and civil engineering demand in 2025 and beyond, with continued strength in water treatment construction through MWH. In Asia, it expects conditions to stay firm as well, particularly where investment is flowing into energy and transportation.

The long-term bet is straightforward: Obayashi can’t rely on Japan alone forever. A meaningful increase in overseas contribution—without importing outsized risk—would be one of the clearest signs it’s evolving from a domestic heavyweight into a truly global construction enterprise.

XV. Conclusion: Building Beyond Boundaries

Obayashi’s 133-year journey—from a teenager whose kimono shop failed in months to a company willing to put “space elevator by 2050” in an official plan—captures something fundamental about Japanese capitalism: patience, continuity, and a belief that building is how a country becomes itself.

What’s striking is how much of the original playbook still holds. Yoshigoro Obayashi’s principles—meticulous execution, responsibility, honest dealing, hitting deadlines, and staying price-competitive—are the same traits that win trust on today’s mega-projects. But the world those principles operate in has changed completely. The first Obayashi jobs served a nation racing to industrialize. Later generations built stations, stadiums, dams, tunnels, and towers for a Japan that rose into the top tier of global economies. Today’s leadership is trying to protect that technical franchise while navigating a harsher reality: demographic decline, labor constraints, governance pressure, and global competition that doesn’t care about legacy.

And that’s why the scandals matter. The 2007 public works violations and the 2017–2018 maglev bid-rigging case aren’t footnotes. They point to an industry culture that, for decades, valued relationships and stability—and sometimes treated coordination as normal. The question now isn’t whether Obayashi has policies. It’s whether the company can change incentives and behavior in a way that holds under pressure, not just under scrutiny.

The space elevator, whatever its eventual feasibility, is the cleanest window into how Obayashi wants to be seen. This is the same company that built Tokyo Station at the dawn of modern Japan, helped rebuild after catastrophe, and engineered the Tokyo Skytree with an earthquake-taming idea borrowed from ancient pagodas. In that context, a plan to connect Earth to orbit isn’t a random marketing stunt. It’s an extension of identity: ambitious, technically minded, and willing to think in timelines longer than most companies can even justify on a slide.

For investors, the pitch is equally clear. Obayashi sits at the intersection of Japan’s infrastructure renewal, government-backed resilience spending, and a more deliberate push overseas—especially in North American water and complex commercial construction. The risks are just as real: a shrinking domestic demand base over the long run, margin pressure from materials and labor, and the execution challenge that comes with new markets and new contracting norms.

Still, there’s a reason Obayashi has lasted 133 years. It has survived regime change, war, recession, earthquakes, and self-inflicted reputational damage—and it kept finding a way to rebuild both structures and credibility.

Whether anyone ever rides an Obayashi-built elevator into space is an open question. But as long as Japan needs bridges, tunnels, towers, and the quiet competence to keep them standing, Obayashi is likely to remain one of the builders that gets the call. In an era obsessed with disruption, that kind of continuity can be its own form of edge.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music