Taisei Corporation: Building Japan's Modern Miracle

I. Introduction: The Architect of a Nation

Picture the scene: Istanbul, October 2013. Japan’s Prime Minister Shinzo Abe stands beside Turkey’s President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan at the entrance to the newly completed Marmaray Tunnel. Sixty meters beneath the Bosphorus—through some of the fastest, most unpredictable currents on Earth—a rail line now runs where, for centuries, only boats could.

They cut the ribbon. Cameras flash. And just behind them is the person who actually had to make the miracle real: Tetsuro Matsukubo, Taisei Corporation’s project director. He had spent eleven years living in Istanbul, working through engineering problems that don’t show up in glossy renderings: tidal currents that flow in opposite directions, Roman-era shipwrecks that forced years of delays, and the requirement that the crossing survive a major earthquake—up to a magnitude 7.5.

For residents, the payoff was immediate. A crossing that used to mean a roughly half-hour ferry ride dropped to a subway trip of just a few minutes. The line didn’t just open with fanfare; it became part of daily life in a city that spans two continents.

That’s Taisei in microcosm: a company that keeps showing up at the edge of what’s possible—and then quietly delivering. And it’s been doing that since 1873, when Japan had only just reopened to the world after two centuries of isolation.

On paper, Taisei Corporation is straightforward: founded in 1873, based in Tokyo, operating across building construction, civil engineering, and real estate development. Its headquarters sit in the Shinjuku Center Building in Nishi-Shinjuku. But those corporate facts don’t capture what Taisei really is: one of the institutions that physically built modern Japan.

Taisei is one of the five Japanese “super general contractors” (スーパーゼネコン)—alongside Kajima, Shimizu, Takenaka, and Obayashi. For generations, these firms have dominated the country’s biggest and most technically demanding projects: subways, bridges, expressways, skyscrapers, tunnels. They’re the civil-engineering equivalent of the most entrenched financial institutions—so embedded in the nation’s infrastructure that their histories blur into Japan’s own.

And yet Taisei is different. After World War II, when Japan’s zaibatsu were dissolved, Taisei was restructured into an employee-owned corporation. While Kajima, Shimizu, Takenaka, and Obayashi remained family-controlled, Taisei became the lone outlier: the only employee-owned super general contractor. That single structural fact has shaped its culture, its incentives, and its ability to survive cycles that crushed others.

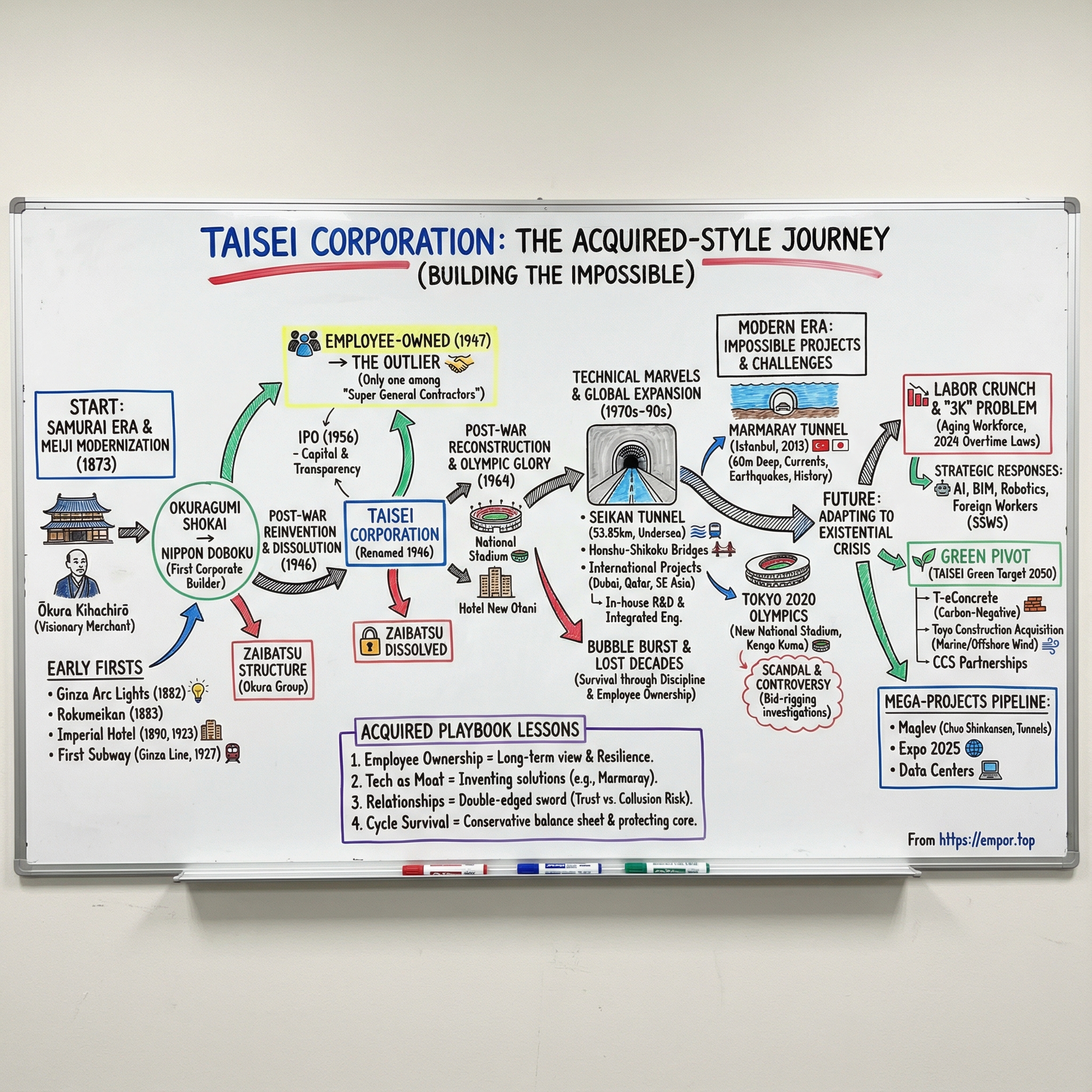

So here’s the framing question for this deep dive: how did a trading company founded by a samurai-era merchant evolve into the builder of Japan’s first subway, the Bosphorus undersea tunnel, and the National Stadium for the Tokyo 2020 Olympics?

And now the modern twist: Japan is running into an existential labor crunch. The workforce is aging, fewer young people are entering the trades, and the whole industry is being forced to do more with less. Can Taisei adapt fast enough to keep doing what it has always done—build the impossible—when the country no longer has the people it once relied on to build anything at all?

This story unfolds across three eras: the Meiji modernization that gave birth to Taisei’s roots, the postwar reconstruction that remade it, and the global expansion that turned it into an international engineering force. Along the way, there’s everything you’d expect from a company this central to a nation’s infrastructure: Olympic booms, zaibatsu politics, scandal, and some of the most ambitious construction projects ever attempted.

Let’s begin.

II. Founding: The Okura Zaibatsu and Meiji Japan (1873–1945)

The Visionary: Baron Ōkura Kihachirō

To understand Taisei, you have to start with the man at its root—and with the once-in-a-century reset button that Japan hit in the late 1800s.

Most zaibatsu dynasties begin with privilege. The Ōkura story doesn’t. Kihachirō Ōkura was born in 1837 in Echigo Province (today’s Niigata Prefecture), from peasant stock in a society designed to keep people exactly where they started. As a young man he left for Edo and worked his way through whatever jobs would take him: an apprenticeship at a dried-bonito wholesaler, time at a grocery store, then work for a gun dealer. By 1857, he was running his own small grocery business.

Then the world flipped.

The Meiji Restoration in 1868 toppled the Tokugawa shogunate, restored imperial rule, and launched Japan into a sprint to modernize fast enough to avoid becoming a colonial possession. In that new Japan, connections and competence could matter more than pedigree. Ōkura had both—and he moved with the moment.

During the Boshin War of 1868–1869, he supplied high-quality firearms to the government army and earned trust when trust was scarce. After that, he expanded through government-linked logistics and trade—transporting goods during the Taiwan Expedition in 1874, building fortune and influence through the Sino-Japanese War of 1894–1895, and conducting direct trade with European countries. The pattern was clear: Ōkura positioned himself as the kind of partner a modernizing state couldn’t do without.

In 1873, he formalized it by founding Okuragumi Shokai, a business that spanned importing, exporting, commerce—and crucially, civil engineering and building construction. This is the seed that would become Taisei.

Fourteen years later, in 1887, Ōkura spun the civil engineering and construction division into Nippon Doboku Co., Ltd., the direct predecessor of Taisei Corporation—and Japan’s first corporation in the construction industry. Not the first builder. The first modern, corporate construction company.

Ōkura didn’t do it alone. He founded Nippon Doboku with cooperation from Eiichi Shibusawa and Denzaburō Fujita, and drew in a wave of ambitious engineers. Shibusawa, often called the “father of Japanese capitalism,” brought credibility and institutional gravity; Ōkura brought timing and a clear understanding of what the country needed: a construction organization that could respond quickly as the economy and the state transformed at speed.

That instinct—move fast when history opens a door—showed up across Ōkura’s broader career too. He helped launch new industries for Japan’s private sector, including wool-based textiles and large-scale beer brewing, both of which had little precedent domestically. Construction, though, would become one of his most lasting bets.

Building Modern Japan

Once Nippon Doboku existed, the work that followed read less like a project list and more like a table of contents for modern Japan.

The company executed major construction one after another—projects tied to government, infrastructure, and national prestige—contributing to Meiji-era modernization. Among them: the Imperial Palace, the Kabukiza Theatre, the Imperial Hotel, the Tokaido Line, and the Lake Biwa Canal.

Then came a pair of projects that weren’t just functional—they were symbolic.

1882 - Ginza Arc Lights: The first electrical street lighting in Japan was installed on Ginza Dori shopping street in Tokyo. 1882 - Rokumeikan, a beautiful western-style building was constructed.

Lighting Ginza with electricity was a public declaration: Japan wasn’t merely adopting modern technology; it could install it, operate it, and make it part of everyday city life. The Rokumeikan, built to host diplomats in a Western-style setting, carried the same message in architectural form: Japan could build in the language the world expected.

As the decades rolled on, Taisei’s predecessor kept attaching itself to “firsts.” Notable works included the first-generation Imperial Hotel in Tokyo and the Lake Biwa Canal Sluice Gate in Shiga, both completed in 1890; the second-generation Imperial Hotel designed by Frank Lloyd Wright in 1923; and Japan's inaugural subway line (Ginza Line, Ueno-Asakusa segment, 2.163 km via open-cut method) in 1927, the first in Asia.

The Frank Lloyd Wright project is one of those moments where a global name intersects with a local builder. Wright designed the New Imperial Hotel, completed in 1923, and Ōkura’s construction organization built it. The building became famous for surviving the Great Kantō Earthquake that struck just after its opening—an early, high-profile reminder that in Japan, engineering isn’t an aesthetic choice. It’s survival.

1927 - Tokyo's Ginza Subway Line, Japan's first subway connecting Ueno to Asakusa was constructed.

That subway was another leap: the same lineage of company that helped electrify Tokyo was now hollowing out the city beneath people’s feet. And it wasn’t a one-off showpiece—the Ginza Line still runs today, carrying commuters along a route first carved out nearly a century ago.

Corporate Evolution and the Zaibatsu Structure

As Japan’s corporate system evolved, the company’s name and structure evolved with it—sometimes abruptly. Over this period it cycled through reorganizations and renamings:

1887 March - Nippon Doboku Co., Ltd. was established as a limited liability company. 1892 November - Dissolution of Nippon Doboku Co., Ltd and establishment of Okura Doboku Gumi. 1911 November - Renamed to Kabushiki Gaisha Okura Gumi. 1920 - Renamed to Nippon Doboku Kabushiki Gaisha. 1924 - Renamed to Okura Doboku Kabushiki Gaisha.

Through all of it, the business remained embedded in the Okura zaibatsu—one of Japan’s “second-tier” conglomerates that expanded after the Russo-Japanese War of 1905. Like other groups of that era, Okura accumulated wealth through government and military business and through foreign trade, then pursued aggressive diversification from late Meiji into the Taishō period.

By the time Ōkura died in 1928, his empire spanned far beyond construction. Companies he left a major mark on included Taisei Corporation, Sapporo Breweries, Imperial Hotel, Imperial Theatre, the Nisshin OilliO Group, Aioi Nissay Dowa Insurance, Tokushu Tokai Paper, Regal Corporation, Nippi, Nippon Chemical Industrial, Tokyo Rope Mfg., and Japan Radio, among others.

But there’s an important line in how he saw himself: he avoided stock speculation and took pride in remaining, above all, a businessperson until the end of his life.

That distinction matters. Ōkura’s legacy wasn’t financial engineering. It was real engineering—organizations, industries, and physical projects. And that builder’s mentality would be tested hard as Japan entered the most turbulent decades of the twentieth century.

III. Post-War Reinvention: From Zaibatsu to Employee-Owned (1946–1970)

The Great Dissolution

The end of World War II didn’t just level Japan’s cities. It also blew up the country’s corporate power structure—especially the zaibatsu. And the Okura empire was squarely in the blast radius.

Under the Allied occupation, SCAP set out to dismantle what it saw as concentrated, monopoly-like economic power. Many of the advisors behind the policy came out of the New Deal era and distrusted tightly knit conglomerates on both economic and democratic grounds. The result was sweeping: sixteen zaibatsu were targeted for complete dissolution, and another twenty-six were slated for reorganization. Okura was on the list, alongside names like Asano, Furukawa, Nakajima, Nissan, Nomura, and others.

For Okura Doboku, this wasn’t a paperwork exercise. It was a threat to the company’s survival.

In 1946, as the order to dissolve the zaibatsu took effect, the company made a decisive move: it changed its name to Taisei Corporation to make a clean break from anything that looked like Okura Zaibatsu. Kishichiro Ōkura and the other executives knew the old name was radioactive.

But Taisei didn’t stop at rebranding. In 1947, the company did something almost unheard of in Japanese corporate life: the president and directors were elected by an employee vote. At the same time, Taisei introduced an employee shareholding system that allowed employees to buy shares in the company.

The name “Taisei” carried a thread of continuity. It was linked to Kihachirō Ōkura’s legacy—derived from his posthumous Dharma name, inspired by Mencius and meant to evoke shared virtue in the act of building. In other words, it nodded to the founder while cutting the visible cord to the zaibatsu.

The real revolution, though, was structural. With the Okura family’s assets seized and holding companies banned, employee ownership wasn’t ideology—it was one of the few viable ways forward. And it created an outcome that still defines Taisei today: while Kajima, Shimizu, Takenaka, and Obayashi remained family-controlled, Taisei became the outlier—built around employee welfare and long-term thinking rather than the interests of a controlling family shareholder.

Building the Post-War Miracle

Then came the rebuild.

Postwar Japan was chaos, scarcity, and rubble—followed by an all-out national sprint to restore basic life and then modernize at astonishing speed. Taisei restarted as a new company in a country that urgently needed roads, bridges, public buildings, and transit. Work didn’t arrive in a trickle. It came as a wave.

As orders surged with economic recovery, the company ran into a different constraint: money and machinery. Large-scale projects required financing. Modern construction required mechanization. To keep up, Taisei made another industry-first move.

In 1956, it went public, becoming the first company in Japan’s construction industry to list shares on a stock exchange. The listing raised capital for expansion while preserving the employee-ownership character that made Taisei distinct.

Right before the listing, managing director Tokuji Mizushima sent employees a blunt message about what life would look like on the other side: once the shares were public, the company’s ups and downs would be visible in the stock price. If they acted rashly or performed poorly, they’d be disgracing themselves in public. The era of being “relaxed,” as he put it, was over.

Taisei did it anyway. And after it did, other construction companies followed.

The 1964 Tokyo Olympics: Preview of Glory

1958 - National Stadium, the first major athletic stadium in Japan was constructed for the third Asian Games. After modification in 1963, it was used as the main stadium of the Tokyo Olympics.

By the early 1960s, Japan wasn’t just rebuilding—it was preparing to reintroduce itself to the world. The 1964 Tokyo Olympics were designed as a national “we’re back” moment, and the National Stadium became the physical stage for that message. It hosted the opening and closing ceremonies of the Games that showcased a modern, technologically confident Japan.

This was Japan's first 1,000 room class international hotel, constructed in conjunction with the Tokyo Olympics held in 1964.

To house the incoming wave of global visitors, Taisei also built the main building of Hotel New Otani—Japan’s first 1,000-room-class international hotel, and a flagship project timed to the Olympics. Stadium and hotel together did what mega-projects often do at their best: they made ambition tangible. Japan wasn’t asking to be seen as modern anymore. It was building proof.

IV. Golden Era: Engineering Marvels & Global Expansion (1970s–1990s)

The Seikan Tunnel: Engineering at the Edge of Possibility

If the 1964 Olympics was Japan’s comeback announcement, the next few decades were the proof. This is when Japanese contractors stopped being seen as domestic builders with big ambitions and started being treated as world-class engineering organizations.

Nothing captured that better than the Seikan Tunnel.

When it opened, it was the world’s longest operational railway tunnel—and it still ranks among the most audacious civil engineering projects Japan has ever attempted. The work stretched across 24 years. The scale was staggering: about 14 million workers were involved over the life of the project.

The Seikan Tunnel links Honshu and Hokkaido. It runs 53.85 kilometers end to end, with 23.3 kilometers beneath the seabed. It held the title of longest rail tunnel in the world until Switzerland’s Gotthard Base Tunnel opened in 2016. Taisei was a key contractor on the effort. It was also dangerous work, claiming the lives of 34 workers and pushing tunneling technology into territory where “standard practice” simply didn’t exist.

And it wasn’t just tunnels. Taisei also proved what it could do at sea.

For the North and South Bisan Seto Bridges, the company built massive anchorages—concrete blocks rising 103 meters—out in the water to hold the main cables in place. The conditions were brutal: rapid tidal currents and deep water. The seabed had to be excavated down 10 meters to create foundations, and roughly 290,000 cubic meters of concrete were poured to form the bridge piers. Taisei already had marine civil engineering experience, but this was the kind of job where it could put its full toolkit on display.

Technology Leadership

One reason Japanese super general contractors became so formidable is that they didn’t just build. They engineered.

Instead of outsourcing research and design, companies like Taisei built deep in-house capability: laboratories, technical centers, and designers who worked alongside the builders. That integrated model mattered most when projects got weird—when geology didn’t match the surveys, when requirements shifted midstream, when regulators added constraints, or when a client asked for the impossible, now.

According to Imaishi, this is exactly why Japanese firms like Taisei were well-suited to projects like Marmaray: they could respond quickly to unexpected requests because the research and design muscle sat inside the organization, not across a contract boundary. And Japan’s hard-earned expertise in earthquake-resistant construction translated directly to an undersea tunnel designed to last a century.

In practice, that combination—construction execution plus engineering innovation—became a competitive advantage. On the most complex projects, the job isn’t just pouring concrete. It’s inventing the method while you build.

Taisei’s resume from this era reflects that breadth: Japan’s first subway in 1927, the new Imperial Palace in 1968, and the Yokohama Bay Bridge in 1989.

Going International

With those capabilities, going overseas wasn’t a leap of faith. It was a strategy.

Taisei took on projects that looked a lot like what it had mastered at home: airports, bridges, and undersea tunnels. International work included the expansion of the Palm Islands undersea tunnel in Dubai, the Bosphorus undersea tunnel in Turkey, the New Doha International Airport in Qatar, and Noi Bai International Airport Terminal 2 in Hanoi. It was also involved in major bridge projects across Southeast Asia, including the Mega Bridge in Thailand, the Cần Thơ Bridge in Vietnam, and Iloilo International Airport in the Philippines.

This expansion was methodical, not splashy. Over time, Taisei built a global footprint with 12 overseas offices, alongside a dense domestic network—15 branch offices, a technology center, and dozens of subsidiaries and affiliates.

In the United States, the company established Taisei Construction Corporation in 1982, starting in Southern California and later taking on client-specific projects across the country.

The Bubble and Its Aftermath

Then the cycle turned.

Japan’s late-1980s asset bubble sent construction demand into overdrive—until it didn’t. When the bubble burst in 1991, the country slid into the “lost decade,” which ultimately stretched into two. For the construction industry, it was brutal. Demand fell, financing tightened, and plenty of firms either collapsed or got absorbed by competitors.

Taisei survived, and its ownership structure helped. Without a controlling family pushing for dividends, and without the same pressure to optimize for short-term market reactions, management could prioritize endurance: keep the organization intact, protect capability, and make it to the other side.

The downturn left a mark. It forced discipline, and it hardened Taisei’s conservative approach to managing its balance sheet—an instinct that continued long after the bubble era became a cautionary tale.

V. The International Showpiece: The Marmaray Tunnel

Connecting Continents

If you want the cleanest case study in what Taisei does best—take on a job that looks borderline unreasonable, then deliver it anyway—you end up back in Istanbul.

Marmaray is a 13.5-kilometer undersea railway link running beneath the Bosporus Strait, tying the European side of the city to the Asian side. It connects Kazlıçeşme and Zeytinburnu in Europe with Ayrılıkçeşmesi in Asia, and includes three underground stations: Yenikapı, Sirkeci, and Üsküdar. Passenger service began on October 29, 2013.

And like most “overnight successes” in infrastructure, the idea was anything but overnight. The concept of a rail tunnel under the Bosporus dates back to 1860, when Sultan Abdulmejid I first proposed it. It resurfaced again in 1892 under Abdul Hamid II, when French engineers developed plans. For roughly 150 years, it stayed a dream—an alluring line on paper that nobody could quite turn into reality.

That finally changed in July 2004, when the contract went to a Japanese-Turkish consortium led by Taisei, alongside Gama Endustri Tesisleri Imalat ve Montaj and Nurol Construction.

Engineering at the Edge of Possibility

The reason it took so long isn’t hard to understand once you see what the Bosporus demands.

This is a narrow, heavily trafficked strait packed with large ships and ferries. Depths reach about 60 meters. Currents run fast—and worse, they run in opposite directions at the surface and near the seabed. And there are no predictable “tidal stops” where conditions conveniently calm down and let you work.

Taisei’s project director, Tetsuro Matsukubo, later said it took two years just to measure and analyze the currents well enough to understand what they would do to the construction plan.

The project used an immersed tube method—basically assembling huge tunnel elements and placing them into a trench on the seabed. That technique wasn’t new. Doing it at this depth was. The crossing itself is a 1.4-kilometer immersed tube assembled from 11 sections. Eight sections are 135 meters long, two are 98.5 meters, and one is 110 meters. Each one weighs as much as 18,000 tons, then gets positioned around 60 meters below sea level, beneath 55 meters of water and another 4.6 meters of earth.

Then there’s the part you can’t engineer away: earthquakes. Marmaray sits only about 20 kilometers from the North Anatolian fault line. The tunnel was designed to survive a magnitude 7.5 earthquake with zero security risks, minimal loss of function, and no water leakage at the immersed tunnel and connection points. It was also designed for a service life of at least 100 years, using early-age, uncracked concrete with a strength of 40 MPa, chosen for resistance to alkaline aggregate reaction, outdoor exposure, frost, and chemical abrasion.

In other words: build a tunnel under one of the world’s most demanding straits, put it deeper than anyone has done before, keep the city running above you, and make it earthquake-proof for a century.

The Unexpected: Ancient History Underfoot

And then Istanbul reminded everyone what it is: not just a modern megacity, but a living archaeological site.

Construction was repeatedly halted by discoveries near Sirkeci, where artifacts dating back roughly 8,000 years were uncovered. Each time ruins appeared, archaeological surveys stopped the job. Over time, those interruptions added up, pushing completion back by nearly five years.

But the delays came with a strange upside. Imaishi noted that the team “learned new things about Istanbul’s history,” including the discovery of an intact Roman-period cargo ship—finds that gave historians new clues about ancient trade routes. Some of the artifacts are now displayed in an open museum inside Yenikapı Station.

What could have been a pure project nightmare—schedule, cost, uncertainty—became something else: proof that mega-projects aren’t just about concrete and steel. Sometimes they’re about adapting in real time to a city’s past.

Matsukubo lived in Istanbul for 11 years, from the start of construction through completion. Looking back on a project defined by currents, depth, seismic risk, and archaeology, he pointed to something less technical as the real differentiator: solidarity between the Turkish and Japanese teams, working toward a shared goal for more than a decade.

VI. The 2020 Tokyo Olympics: Glory, Controversy & Scandal

Building the Games—Again

Fifty-six years after Taisei helped build the stage for Tokyo 1964, it landed the defining contract of Tokyo 2020: the new National Olympic Stadium.

The path to that win ran through a very public failure. Japan had originally selected a design by British architect Zaha Hadid, but the plan ignited backlash as projected costs ballooned. Under mounting pressure, the government scrapped the design and restarted the process.

By September 2015, two bids were on the table. One paired Taisei with architect Kengo Kuma. The other was a consortium that included Takenaka, Shimizu, and Obayashi, working with architect Toyo Ito. In December 2015, the Japan Sport Council chose Kuma’s team, with Taisei as the builder. Construction began a year later, in December 2016.

Even after the reset, costs were still a national obsession. The government ultimately reached an agreement in June 2015 with Taisei Corporation and Takenaka Corporation to complete the stadium at a total cost of around 250 billion yen. Later reporting described the stadium as a 157-billion-yen project, delivered through a joint effort led by Kengo Kuma, Taisei, and Azusa Sekkei.

What emerged in Tokyo’s Meiji Jingu Gaien district was intentionally the opposite of the discarded “starchitect” statement piece. The 68,000-seat stadium leaned into warmth and restraint: deep eaves and cedar panels, a design meant to feel Japanese, not just Olympic. Built in almost exactly three years under Taisei’s supervision, it went on to host the opening ceremony and the track and field events for both the Olympics and Paralympics.

For Taisei, it should’ve been a clean narrative rhyme: 1964 to 2020, bookending Japan’s postwar rise and its modern reinvention.

But Tokyo 2020 didn’t stay clean for long.

The Shadow: Bid-Rigging Scandals

The Games—postponed to 2021 due to COVID-19—ended up remembered not only for sport, but for the investigations that followed.

Six companies were indicted on bid-rigging charges connected to Tokyo 2020 contracts. The list included major ad giants Dentsu and Hakuhodo, alongside four other Japanese companies, and Japan’s Fair Trade Commission also filed a complaint. By February 2023, a total of 22 individuals had been indicted on bribery and bid-rigging charges related to the Games.

The fallout spread beyond Tokyo. In October 2023, the Japanese Olympic Committee formally withdrew Sapporo from consideration to host the 2030 Winter Olympics, citing a lack of public support in the wake of the corruption issues.

And for Taisei, the Olympic scandal collided with another, even more existential investigation—one tied to the next national showpiece: the Chuo Shinkansen maglev line.

Prosecutors raided the headquarters of four of Japan’s biggest construction companies—Taisei, Obayashi, Shimizu, and Kajima—over alleged collusion on bids for maglev construction contracts backed by Prime Minister Shinzo Abe’s government. Investigative reporting later said a senior Taisei official admitted during questioning that the company had been involved in bid-rigging for parts of the project. Authorities suspected that around 2014 to 2015, senior figures across the four firms coordinated who would win orders for work including the Shinagawa and Nagoya stations.

Much of the work was being executed through joint ventures led by the same four builders—structures that, in normal times, are how Japan actually gets mega-projects done. And that’s the uncomfortable truth the scandal exposed.

In Japanese construction, the relationships that make world-class collaboration possible can also make coordination too easy. The super general contractors have worked together for generations. On paper, that’s experience and trust. In practice, it can blur the line between legitimate cooperation and illegal collusion—and Tokyo 2020 made that blur impossible to ignore.

VII. The Existential Challenge: Japan's Labor Crisis

Demographics as Destiny

Japan’s construction industry is running into a wall that even world-class engineering can’t tunnel through: there simply aren’t enough people.

Yuri Okina put it starkly in the first of our three lead articles this week. Across all occupations, Japan’s “effective job openings to jobseekers” ratio sits at about 1.26. In construction, it’s above five.

Think about what that means in human terms. For every construction worker looking for a job, there are more than five jobs waiting. That isn’t a normal boom-and-bust staffing problem. It’s a structural shortage, locked in by Japan’s demographics.

The country’s aging has accelerated into a new reality. In 2024, the number of people aged 65 and older reached a record 36.25 million, about 29.3% of the total population. Sectors that depend on physical, on-site labor—construction and nursing especially—are feeling the squeeze, with job-to-applicant ratios around 4.6 and 3.7. In 2023, the strain was so acute that a record 260 corporate bankruptcies were attributed purely to companies being unable to secure enough workers.

This is what “demographics as destiny” looks like when it hits an industry that can’t be fully offshored.

The mechanics behind it are painfully clear. Japan’s birth rate (total fertility rate) fell sharply from around four to around two in the 1950s, resumed its decline in the early 1980s, and was 1.15 in 2024. Meanwhile, life expectancy rose dramatically: for men, from 63.6 years in 1955 to 81.1 in 2024; for women, from 67.8 to 87.1. The working-age population peaked in 1995. The total population peaked later, in 2008.

So even if every pro-natalist policy worked perfectly starting tomorrow, the construction labor pool would still keep shrinking for years—because the next generation simply isn’t large enough.

The "3K" Problem

The labor shortage isn’t just about headcount. It’s also about perception.

In Japan, construction has long carried the “3K” stigma: kitanai (dirty), kitsui (tough), and kiken (dangerous). Those three words have done real damage to recruitment. Young people are often turned off by the industry’s image—hard physical conditions, a macho culture, and a sense that the status and pay don’t match the effort.

And this reputational problem lands on top of the demographic one: fewer young people exist in the first place, and even fewer want to join.

The 2024 Overtime Regulations

Then, just as the staffing situation became critical, regulation tightened the vise.

From April 1, 2024, overtime cap regulations with penalties began applying to construction. In principle, overtime is limited to 45 hours per month and 360 hours per year.

Construction, along with doctors and professional drivers, had been provisionally exempted under the 2019 amendment to the Labor Standards Act—because their work patterns didn’t fit neatly into standard labor rules. The term “2024 problem” captured the fear of what would happen when those exemptions ended in April 2024.

For construction, the government provided a five-year grace period before the cap took effect. But once it arrived, it created a brutal double-bind: the industry needs more labor hours to keep projects moving, but the rules now restrict how many hours existing workers can legally provide.

There are knock-on effects too. With less labor capacity, projects can take longer, schedules can slip, and fewer projects may start. Japan’s new overtime limits—effective from April 2024—were expected to ripple into supply chains, including steel. Construction accounts for more than 40% of domestic steel demand, and anything that slows the pace of building can eventually show up as weaker demand upstream.

The law’s intent is clear: improve working conditions. The trade-off is also clear: less flexibility in an industry already running short on people.

Strategic Responses

Taisei and the other super general contractors are trying to fight this on multiple fronts—because they don’t have the option to simply “hire their way out.”

One path is productivity. Taisei is committed to adopting BIM, AI, and robotics to get more output per worker. As its Integrated Report 2024 notes, this push matters not just for efficiency, but for staying competitive in an oligopoly where everyone is chasing the same limited pool of skilled labor.

Another path is people—specifically, foreign workers. Japan has been opening the door wider, slowly but meaningfully. The number of foreign workers quadrupled from just under half a million in 2008 to 2.3 million in 2024, with growth accelerating after the pandemic. Most work in manufacturing and services, with the largest shares coming from Vietnam (25%) and China (18%).

A major policy shift came in 2019 with the introduction of the Specified Skilled Worker System (SSWS). The framework was designed to bring in work-ready, mid-skilled foreign nationals for industries with severe labor shortages—including construction. Unlike the Technical Intern Training Program (TITP), SSWS offers a path to longer-term employment and residency for workers who pass the required skills and language tests.

None of these responses are silver bullets. But together, they show the direction the industry is being forced to move: fewer hands, more technology, and a workforce model Japan resisted for decades—now becoming essential to keeping cranes in the air.

VIII. The Green Pivot & Future Strategy

TAISEI Green Target 2050

If Japan’s labor crunch is the near-term constraint, decarbonization is the long-term one. Taisei has put a flag in the ground with a simple headline commitment: reduce CO2 emissions from its business activities and related activities to zero by 2050.

Inside the company, that goal is packaged as its long-term environmental target, “TAISEI Green Target 2050,” built around the idea of realizing a sustainable, environmentally friendly society. The logic is straightforward: construction is Taisei’s core business, so the company will both affect—and be affected by—the world’s transition to a decarbonized economy. Taisei frames the response as both risk management and opportunity: identify what’s coming, then develop and spread the technologies and services needed to build differently.

The challenge is especially acute in concrete. It’s the foundational material of modern civilization—and it’s inherently carbon-intensive. Cement manufacturing alone accounts for roughly 7% of global CO2 emissions.

Taisei’s answer is to push beyond “a little less carbon” and try to make something that flips the equation entirely: carbon-recycling concrete that can absorb more CO2 than it emits.

T-eConcrete: Carbon-Negative Concrete

Taisei’s flagship effort here is its T-eConcrete® lineup—concrete designed to limit cement use while keeping the strength and workability of ordinary mixes, with the explicit aim of reducing CO2 emissions.

The idea behind its “carbon recycle” approach is to treat CO2 not only as something to reduce, but as something to recover and reuse as a resource. In Taisei’s Carbon_Recycled Concrete, calcium carbonate is manufactured by absorbing CO2 from exhaust gas, then mixed with ground granulated blast furnace slag (GGBFS) and special additives used as activators or stimulators.

Taisei describes the carbon math on a per-cubic-meter basis: the calcium carbonate component absorbs 171 kg/m3 of CO2, while producing the materials emits 55 kg/m3. The net balance is -116 kg/m3—“carbon negative,” meaning more CO2 is absorbed than released.

In plain terms, it’s concrete that isn’t just “less bad.” It’s designed to pull carbon out of the system. If it can be applied broadly, it has the potential to change the emissions profile of construction itself.

The Toyo Construction Acquisition

Decarbonization, though, isn’t only a materials story. It’s also a portfolio story—what kinds of projects you’re set up to win over the next twenty years.

Taisei’s biggest move on that front was its decision to acquire Toyo Construction, a marine civil engineering specialist, for about ¥160 billion (about $1.1 billion), aiming to buy all shares through a tender offer priced at ¥1,750 per share. Toyo expressed support for the offer, which was scheduled to run through Sept. 24.

If fully consummated, Toyo would become a wholly owned subsidiary. Nikkei Asia noted that the deal would be the largest acquisition in Japanese construction history and that the combined revenue would almost match Obayashi, Japan’s second-largest construction company.

Taisei later completed the acquisition of a 79.8% stake in Toyo Construction Co., Ltd. from Yamauchi-No.10 Family Office and others on September 24, 2025.

Toyo brings a very specific toolkit: port and harbor construction, dredging, land reclamation, and other marine construction, alongside an architecture division, a growing offshore wind business, and a meaningful presence outside Japan, including offices in the Philippines and projects across Southeast Asia and Kenya. Taisei’s bet is that Toyo’s long operating history, technical capabilities, and investment mindset strengthen the combined group’s position at a moment when labor shortages and elevated materials costs are pressuring margins and schedules across the industry.

Strategically, the most important implication is offshore wind. The acquisition positions Taisei to participate more directly in Japan’s offshore wind buildout, including floating offshore wind—an area where marine engineering expertise isn’t a nice-to-have, it’s the barrier to entry.

The two companies have said they will cooperate to support floating offshore wind deployment in Japan, aligning with the country’s carbon neutrality by 2050 target and its ambition to develop 30 GW to 45 GW of offshore wind power by 2040.

Carbon Capture & Renewable Energy

Taisei is also placing chips on carbon capture and storage, where construction know-how, project management, and industrial partnerships matter as much as the underlying chemistry.

In 2023, Taisei joined Nippon Steel, Taiheiyo Cement, Mitsubishi Heavy Industries (MHI), ITOCHU Oil Exploration, INPEX, and ITOCHU in a feasibility study for the Advanced CCS project, part of the Tohoku West Coast CCS initiative. The effort sits in the broader frame of Japan’s national decarbonization goals: carbon neutrality by 2050 and a 46% reduction in greenhouse gas emissions (from FY2013 levels) by FY2030.

Taken together—new materials like T-eConcrete®, bigger bets like Toyo, and partnerships in CCS—Taisei is trying to do what it has always done when the ground shifts under it: treat the constraint as an engineering problem, and then build a business around the solution.

IX. The Mega Projects Pipeline

The Chuo Shinkansen Maglev

Even with the bid-rigging investigations hanging over the industry, Taisei remained part of the team on the project Japan has treated as its next great national statement: the Chuo Shinkansen maglev, designed to link Tokyo to Osaka via Nagoya.

Construction began on December 17, 2014. The vision, though, started earlier. In December 2007, JR Central said it would fund the line largely on its own rather than relying on government financing. The price tag quickly became part of the story: what was estimated at about 5.1 trillion yen in 2007 had risen to more than 9 trillion yen by 2011.

The core reason is simple and brutal: the route is mostly underground. Around 86% of the initial Tokyo–Nagoya section is planned to run through tunnels. That’s expensive, slow, and technically demanding—and it’s exactly the kind of work that plays to Taisei’s strengths.

As of 2024, the planned opening was 2029. The technology is the headline. The maglev hit 603 km/h in testing, with commercial operations planned at a maximum of 500 km/h. If it delivers on schedule and performance, it would shrink the Tokyo–Osaka trip from today’s roughly 2.5 to 3 hours by Shinkansen to just over an hour—and effectively redraw the map of Japan’s two biggest economic regions.

Osaka World Expo 2025

If the maglev is the long, tunneling grind, Expo 2025 is the opposite: a fixed deadline, a public spotlight, and no room to slip.

By mid-April 2024, construction had started on only 14 country pavilions, even though 36 had already chosen construction firms. The Expo organizer planned to open on April 13 the following year with a grand opening ceremony—but the risk of cascading delays was becoming harder to ignore.

Expo 2025 also turned into a stress test for Japan’s new labor reality: fewer workers, and stricter limits on overtime. As pavilion construction lagged, the Japan Association for the 2025 World Exposition asked the government to refrain from applying overtime work limits to construction for Expo sites.

That triggered a sharp response. On August 4, the Council of Japan construction industry employees' unions (JCU)—an umbrella group representing unions from 35 general contractors—issued a protest statement accusing the organizer of “neglecting workers’ rights.” The JCU argued that exempting Expo construction from overtime limits was essentially an admission that the deadline would be met by overwork, and said the idea was completely unacceptable.

In other words, the Expo wasn’t just a building program. It became a public argument about what Japan is willing to demand from its construction workforce—and what it can realistically deliver under the new rules.

Data Centers and Digital Infrastructure

While Japan debates how to build the next generation of national showpieces, a quieter wave of mega-projects has been surging: digital infrastructure.

Taisei has been commissioned to construct new large-scale data centers for Microsoft in Tokyo and Osaka. The work is a different kind of complex—less visible than a stadium or a tunnel, but brutally demanding in its own way, packed with tight tolerances, specialized systems, and high expectations for reliability.

And the timing is not accidental. As artificial intelligence drives rapid growth in computing demand, data center construction has become an attractive, higher-margin pocket of the broader market. For Taisei, it’s a natural fit: technically intricate facilities that reward execution, coordination, and deep engineering capability—the same muscles the company built over 150 years, now pointed at the backbone of Japan’s digital economy.

X. Playbook: Business Lessons from 150 Years of Building

Employee Ownership as Competitive Advantage

Taisei’s shift from a zaibatsu construction arm to an employee-owned company wasn’t some enlightened governance experiment. It was a postwar necessity, pushed by the Allied occupation’s dismantling of the conglomerates. But what began as an imposed solution turned into a durable edge.

With no controlling family to satisfy and no obvious “owner” to optimize for, Taisei could afford to think in decades. That matters in construction, where the real asset isn’t a factory or a patent portfolio—it’s the ability to consistently deliver complex projects, with teams who’ve learned the hard lessons the slow way. During Japan’s lost decades, that long-term orientation gave Taisei room to keep investing in capability and to hold onto talent while others were forced into sharper cutbacks.

The Keiretsu Advantage—and Liability

Japanese construction runs on relationships. General contractors, subcontractors, and suppliers form dense, long-lived networks built over generations. At their best, these ties are what make the impossible doable: they create speed, trust, and coordination when a project is too complex to be managed purely through contracts.

But the same structure has a dark side. When everyone has worked together forever, it can become far too easy to “coordinate” outcomes that are supposed to be competitive. The bid-rigging scandals tied to the Olympics and the maglev project are that tension made public: the very ecosystem that helps produce world-leading execution can also create the conditions for illegal collusion.

Technology as Moat

Taisei’s competitive advantage isn’t just scale. It’s the habit of inventing its way through constraints.

From award-winning tunneling techniques like the spherical shield method to newer bets like carbon-recycling, carbon-negative concrete, Taisei has repeatedly treated technology as a differentiator, not a support function. That’s especially powerful in a business where many competitors can buy the same equipment and hire from the same labor pool.

A big part of the reason this works is structural. Unlike many Western construction firms that outsource key engineering and design work, Japan’s super general contractors tend to keep deep research and technical capability in-house. That integration becomes decisive when the ground conditions don’t match the surveys, when regulators add new requirements midstream, or when a project like Marmaray throws currents, earthquakes, and archaeology at you all at once. Taisei’s model is built for those moments.

Surviving Industry Cycles

Construction is cyclical by nature, and Taisei has lived through every version of that cycle: bubble-era excess, post-bubble stagnation, reconstruction surges after disasters, and Olympic booms with political strings attached. The playbook has been consistency over drama—conservative balance sheet management, discipline about not overextending at the top of the market, and protecting the core capabilities that take decades to build.

That discipline shows up even in the numbers. For FY2025, Taisei reported net sales of ¥2.15 trillion, operating income of ¥120.1 billion, and net income of ¥123.8 billion.

It also shows up in capital allocation. With a mandate to repurchase up to ¥150 billion in shares (up to 30 million shares, or 16.41% of issued capital), Taisei had already spent ¥104.4 billion to buy back 15.3 million shares by June 2025. The point isn’t financial engineering for its own sake. It’s a signal: management believes the best use of capital, at that moment, included reinvesting in the company itself—another expression of the same long-term mindset that has kept Taisei standing through Japan’s toughest downcycles.

XI. Porter's Five Forces & Hamilton's Seven Powers Analysis

Porter's Five Forces

Industry Rivalry: Moderate-High

Japanese construction is a two-level battlefield. At the top, five super general contractors operate like an oligopoly, trading blows over the country’s biggest and most prestigious work. Beneath them is a vast universe of smaller firms—hundreds of thousands—competing fiercely for regional projects and subcontracting roles.

On the mega-project tier—undersea tunnels, Olympic venues, maglev infrastructure—rivalry is real, but constrained. There are only a handful of firms with the balance sheets, engineering depth, and delivery track records to even bid credibly. That narrows the field and keeps the fight concentrated around a small set of repeat players.

Buyer Power: Moderate

The government is one of the biggest customers in the entire market, and that comes with leverage. Public agencies can dictate procurement rules, set contract terms, and ultimately decide who wins. Even when only a few contractors are capable, the state still holds meaningful power through approvals, specifications, and budget constraints.

Private developers have less sway when the job is genuinely specialized—when you need deep technical expertise, earthquake performance, or complex logistics. But for more standard construction, private buyers can still push on price, schedule, and terms by playing contractors against each other.

Supplier Power: Moderate-High

In this industry, “suppliers” doesn’t just mean steel and cement. The most important input is skilled labor—and Japan’s labor shortage has made that input scarce.

The shortage is especially acute in sectors like construction, where demand is concentrated in professional, technical, and skilled roles. That scarcity changes the bargaining balance. Skilled workers have more leverage than they used to, and contractors feel it in scheduling, productivity, and the ability to staff multiple sites at once.

By contrast, equipment and materials suppliers generally operate in more competitive markets. They matter, but they don’t have the same systemic chokehold as labor.

Threat of Substitutes: Low

There isn’t a substitute for building the physical world. Bridges, tunnels, railways, stadiums, airports—if you want them, someone has to construct them.

Prefab and modular techniques can reduce onsite labor and shorten timelines in certain cases, but they remain limited for many large, bespoke, or infrastructure-heavy projects. They’re a tool, not a replacement for the industry.

Threat of New Entrants: Very Low

Taisei has been accumulating capability since 1873, and that time shows up as a moat. Mega-project construction requires more than capital. It requires decades of execution knowledge, deep relationships with public and private clients, a proven safety and quality system, and the confidence that you can deliver when conditions stop matching the plan.

Those barriers are hard to cross. International competitors can win the occasional contract, but replicating the domestic integration of Japan’s super general contractors—and the trust that comes with it—is extraordinarily difficult.

Hamilton's Seven Powers Analysis

Scale Economies: Strong

The super general contractors can afford what smaller firms can’t: engineering labs, specialized technical centers, large equipment fleets, and the organizational muscle to manage multiple massive projects at once. Those fixed costs get spread across a wide pipeline, improving unit economics and making it hard for smaller entrants to match their capabilities profitably.

Network Effects: Moderate

Japan’s contractor ecosystem runs on long-lived relationships among general contractors, subcontractors, and suppliers. The more embedded a company is in these networks, the easier coordination becomes and the lower the friction in getting work done—especially on projects where speed and reliability matter as much as price.

Counter-Positioning: Moderate

Taisei’s employee ownership is a genuine point of differentiation versus its family-controlled peers. It can support longer investment horizons and reinforce policies that prioritize workforce stability—an advantage when attracting and retaining talent has become a strategic battleground.

Switching Costs: Strong

On multi-year, complex projects, replacing a general contractor midstream is close to a worst-case scenario: delays, disputes, redesigns, rework, and risk. Once a contractor is selected and mobilized, buyers are effectively locked in unless something breaks badly. That lock-in is especially powerful on technically demanding infrastructure.

Branding: Moderate

Reputation matters, particularly for government work and high-visibility private projects. But in construction, brand is ultimately earned through performance. The market remembers who delivers safely, on schedule, and to spec—and who doesn’t.

Cornered Resource: Moderate

Proprietary methods and technologies—whether in advanced tunneling or new low-carbon materials like T-eConcrete—can create meaningful advantages. But those advantages are often time-bound. In construction, the best ideas tend to diffuse, even if replication takes years.

Process Power: Strong

This is where Japanese super general contractors, Taisei included, have historically separated themselves: project management discipline, quality control, safety systems, and the ability to coordinate enormous complexity across thousands of moving parts. These are capabilities built over decades, embedded in culture and workflow, and extremely hard to copy quickly—especially for newcomers trying to break into the top tier.

XII. Key Performance Indicators for Investors

For investors trying to understand whether Taisei’s strategy is working in the real world, three KPIs are worth watching closely:

1. Order Backlog Growth

In construction, revenue is often the echo of decisions made years earlier. The order backlog—work that’s been contracted but not yet completed—is the clearest early signal of what’s coming next. But in a market defined by labor constraints, bigger isn’t automatically better. The key is whether backlog is growing in a way Taisei can actually execute, which is why it matters to watch both the absolute backlog and the backlog-to-revenue ratio. Together, they show whether Taisei is winning the right work, at the right pace.

2. Gross Profit Margin on Building Construction

From the medium- to long-term perspective, we aim to achieve a gross profit ratio of 10% or more in the Group domestic building construction...

Building construction has traditionally been the tougher margin business versus civil engineering, largely because bidding is more competitive and differentiation can be harder to sustain. That’s why Taisei’s explicit long-term target of 10% or more in gross profit margin for domestic building construction is so important. Movement toward that goal is a real-time read on pricing discipline, project selection, and day-to-day execution—where small mistakes can erase profits fast.

3. Labor Productivity Metrics

If labor is the limiting factor for the entire industry, then productivity is the lever that separates winners from everyone else. Metrics like revenue per employee—and measures of how efficiently projects get delivered relative to the workforce required—become increasingly telling. Taisei’s push into automation, AI, and process innovation only matters if it shows up here: doing more with fewer hands, without sacrificing quality or schedule.

XIII. Investment Considerations: Bulls and Bears

The Bull Case

Structural Tailwinds: Japan has to rebuild and retrofit—whether it wants to or not. The country faces an aging stock of infrastructure, rising disaster risk, and an energy transition that demands new grids, ports, and coastal works. Government spending on disaster prevention, mitigation, and national resilience alone totals around 15 trillion yen over five years. Add in deadline-driven national projects like Expo 2025, the Chuo Shinkansen maglev buildout, and the ramp toward offshore wind, and you get a pipeline with real visibility well past 2030.

Consolidation Leadership: The Toyo Construction acquisition is a signal that Taisei isn’t planning to sit still while the industry tightens. With labor shortages forcing rationalization, scale matters—and so does the balance sheet to act when opportunities appear. The combined revenues of Taisei and Toyo Construction are expected to reach approximately ¥2.32 trillion (about $15.7 billion) for the financial year ending in March 2026, putting it close to Obayashi, Japan’s second-largest construction company. In a consolidating market, Taisei looks positioned to be the buyer, not the bought.

Technology Differentiation: Taisei’s edge has never been “we build.” It’s “we invent how to build.” Carbon-negative concrete, advanced tunneling methods, and AI-driven construction planning don’t just make for good press releases—they’re the kinds of tools that can protect margins and win bids as sustainability requirements tighten. If the industry is being forced to do more with fewer hands and less carbon, Taisei is at least pointing its R&D in the direction the world is moving.

Capital Return Discipline: Management has also been willing to return capital aggressively, and the share buyback program reads as a statement of confidence. Meanwhile, the company’s FY2025 results—net sales of ¥2.15 trillion, operating income of ¥120.1 billion, and net income of ¥123.8 billion—underscore that Taisei can still execute at scale and convert that execution into meaningful profit.

The Bear Case

Labor Constraint Severity: The hardest problem here isn’t demand. It’s capacity. Construction remains stubbornly physical, and in the near term, there’s no software update that can replace experienced tradespeople on site. If labor shortages worsen faster than productivity gains from automation and planning tools, the result is the same no matter how strong the order book looks: delays, cost overruns, and margin compression.

Bid-Rigging Overhang: Tokyo 2020 and the maglev investigation highlighted how fragile trust can be in an industry built on long relationships. If authorities pursue further action, consequences could go beyond fines—potentially including restrictions on government work and long-lasting reputational damage. For a contractor whose biggest opportunities often come from public or quasi-public mega-projects, that’s not a small risk.

Demographic Destiny: Japan’s population is shrinking, and over time that tends to shrink the economy behind it. Even if near-term construction stays strong because so much needs upgrading, a smaller country ultimately demands less new building. Taisei’s international expansion exists, but it has remained modest compared with its domestic dominance—meaning the company is still heavily exposed to Japan’s long-run trajectory.

Regulatory Double-Bind: Overtime restrictions reduce surge capacity right as the industry needs it most. At the same time, social pressure for better work-life balance makes construction a harder sell to younger workers. These forces can become binding constraints even in a market where pricing power and demand would otherwise look favorable.

Currency and Macro Risk: A weakening yen can raise import costs for materials while also shrinking the effective value of overseas earnings. Layer on monetary policy normalization and recession risk, and you have an uncertain macro backdrop that can hit margins and project economics in ways contractors don’t fully control.

XIV. Conclusion: Building the Next Century

One hundred fifty-two years ago, in the middle of Japan’s most dramatic social transformation, a former grocery clerk founded a trading company. Over time, that seed grew into a builder that helped carry the country from feudalism to modernity—lighting Ginza with Japan’s first electric streetlamps, digging the first subway line, racing to finish landmark hotels for the world’s gaze, and taking on projects tied directly to national identity.

Taisei lived through the kind of shocks that end most companies. The zaibatsu were dismantled. Cities had to be rebuilt from rubble. Booms turned to busts. Mega-project cycles rose and fell with politics and public mood. And through all of it, Taisei kept doing the work.

Its defining difference—employee ownership—wasn’t born from some clean-sheet philosophy. It was an improvised solution to a postwar reality. But it became a durable advantage: a structure that could support long-term investment, keep capability intact through downcycles, and prioritize the people and processes that actually deliver complex projects.

Now the constraints are changing again. The next era isn’t only about engineering difficulty. It’s about building in a Japan with fewer workers, stricter limits on overtime, and a world that’s demanding lower-carbon materials and methods. At the same time, the industry carries reputational baggage from scandals that made the public question how the biggest contracts get awarded.

Taisei’s response reads like a company that recognizes the scale of the shift: carbon-negative concrete, AI and automation to squeeze more output from fewer hands, and strategic moves like expanding into marine engineering and offshore wind. Whether that’s enough, and whether it arrives fast enough, is the unanswered question.

But the need is not going away. Japan will keep demanding buildings that can ride out earthquakes. It will keep spending to defend against floods and typhoons. It will need new energy infrastructure, upgraded transport, and a modern digital backbone. For more than a century and a half, when Japan has decided something must be built—despite risk, complexity, and constraint—Taisei has been one of the companies it calls.

The test of the next century isn’t whether Taisei can build the impossible. It’s whether it can keep building at all—by creating a workforce model, a technology stack, and a culture that can match its ambitions in a country running out of people.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music