INPEX Corporation: Japan's Quest for Energy Independence

Introduction: The Existential Bet

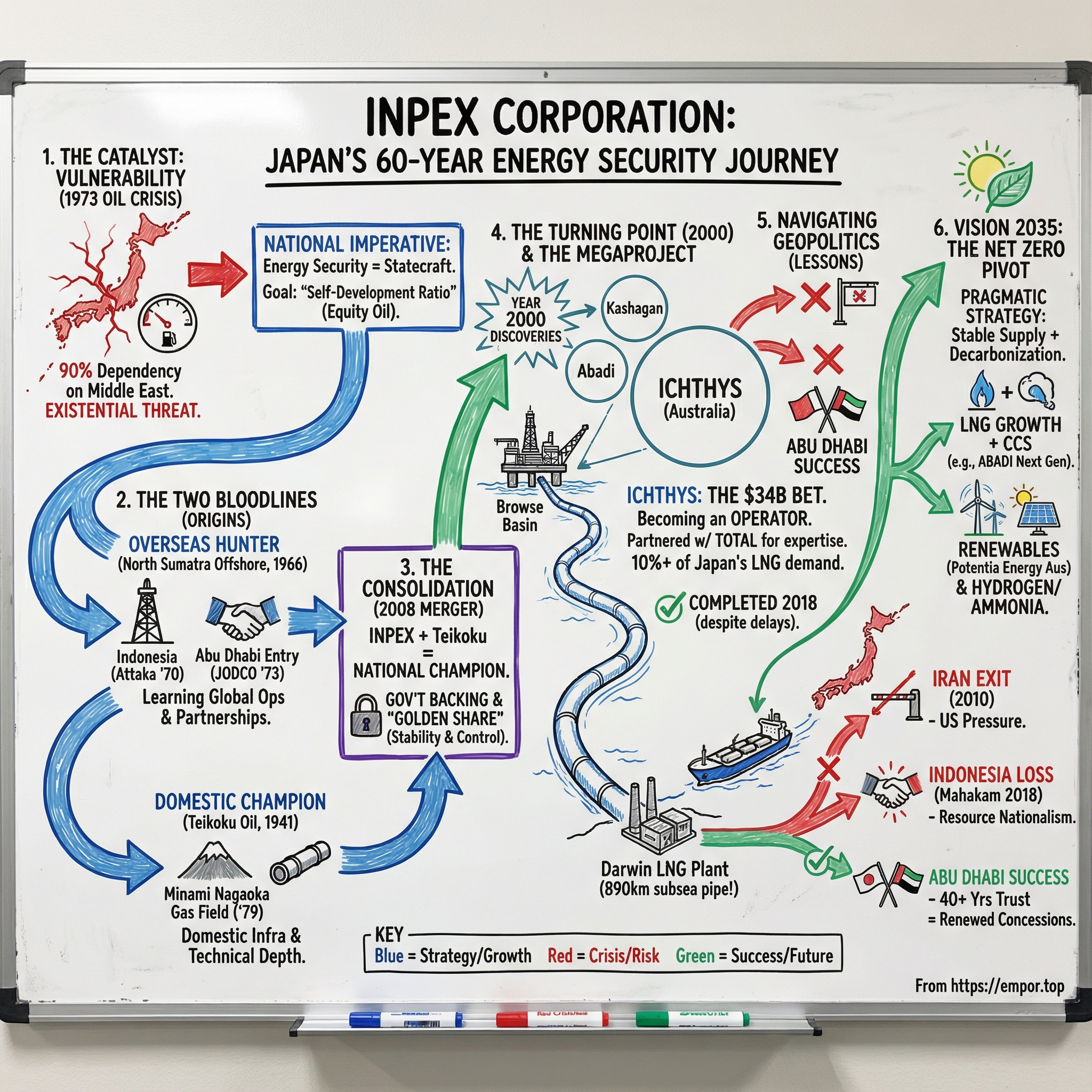

Picture Japan in the autumn of 1973. The Arab oil embargo hits, and suddenly the country’s high-speed economic miracle looks a lot more fragile. Consumers line up and hoard basics like toilet paper—not because toilet paper has anything to do with crude oil, but because fear is contagious, and the system feels like it’s cracking.

Japan was uniquely exposed. The country imported roughly 90% of its petroleum from the Middle East, and overnight it became clear that energy wasn’t just another commodity input. It was a national vulnerability. Facing its most serious crisis since 1945, the government ordered a 10% cut in industrial oil and electricity consumption. By December, it escalated to an immediate 20% cut for major industries, plus restrictions on leisure automobile use.

That shock never really went away. It hardened into doctrine.

Fast forward to today, and INPEX Corporation is what Japan built in response: not merely an oil and gas company, but an institution designed to make sure the country is never quite that defenseless again. INPEX was established in February 1966 as North Sumatra Offshore Petroleum Exploration Co., Ltd. Over time it became Japan’s largest oil and gas exploration and production company, with exploration, development, and production projects spanning 20 countries.

On paper, INPEX is a scale story. It produces around 230 million barrels of oil equivalent per year and holds 6.2 billion barrels of oil equivalent in proven and probable reserves. But those numbers aren’t the point. The point is what they represent: decades of Japan paying, patiently, to buy itself options—supply certainty, relationships, operating capability, and a little more leverage in a world where energy has always been geopolitical.

This is also a story about timeframe. INPEX discovered the Ichthys field in 2000 and didn’t ship its first LNG cargo until 2018—an eighteen-year commitment to a single project. That kind of horizon is almost unnatural in modern capital markets. But it makes perfect sense if your real customer is a nation that learned, in 1973, what happens when the lights can be turned off from afar.

This article traces INPEX’s journey from post-war vulnerability to the construction of a $34 billion megaproject on the other side of the world—and what that journey reveals about Japan’s energy strategy, the state’s role in building national champions, and the hard business lessons embedded in one of the most ambitious corporate transformations of the last half-century.

Japan's Energy Trauma & The National Imperative

To understand INPEX, you have to start with a blunt fact of geography. Japan sits on the Pacific Ring of Fire—earthquakes, volcanoes, and deep water everywhere—but it’s largely petroleum poor. There isn’t enough domestic oil, and not nearly enough natural gas, to run an economy of Japan’s size. That constraint has shaped national strategy for more than a century, and it turns energy from a business input into a matter of statecraft.

The 1973 oil crisis exposed that reality in the harshest possible way. At the time, Japan imported about 97% of its oil, most of it from the Middle East. And the country had built its postwar boom on the assumption that oil would stay cheap and plentiful. From 1961 to 1971, Japan’s gross national product grew at an average of about 10% a year—growth powered, in large part, by rising energy consumption.

Then the embargo hit, and the bill came due.

Oil prices didn’t just rise; they detonated—quadrupling from roughly $3 a barrel to nearly $12 by the end of 1974. For Japan, that shock immediately showed up as inflation and a sudden loss of consumer purchasing power. In 1974 alone, consumer prices rose by almost 25%.

Just as important as the macro numbers was the mood. The boom that had turned Japan into an industrial powerhouse abruptly stalled. Panic buying spread—petroleum products, detergent, toilet paper—anything that felt like “the basics” when the system looked unstable. And in 1974, Japan’s economy contracted for the first time since World War II. An era of low growth followed, along with a deep, lingering awareness that the country’s prosperity could be throttled from overseas.

Japan’s response was sweeping. It diversified suppliers outside the Middle East, expanded nuclear power, and pushed conservation measures. It also pursued resource diplomacy, providing funding tied to relationships with Arab governments and the Palestinians. Over the long run, the shock helped accelerate a structural shift away from oil-intensive industries, with investment moving toward electronics.

But the institutional changes mattered just as much as the industrial ones. In December 1975, the government compiled the “Basic Direction for the Comprehensive Energy Policy,” a marker that energy security was no longer treated as a market problem—it was now a national priority. Policy tightened around reducing reliance on imported oil and broadening alternative energy sources. JEXIM expanded loans tied to petroleum, liquefied natural gas (LNG), and coal. Those funds weren’t only about projects; they were tools of oil diplomacy, designed to secure supply through economic cooperation with petrostates.

Out of this environment came the machinery that would eventually power INPEX’s rise. The Japan National Oil Corporation (JNOC) became the government’s main vehicle for backing overseas exploration and development. The goal was to raise Japan’s “self-development ratio”—the share of the country’s oil and gas consumption sourced from projects where Japanese companies owned equity stakes.

The logic was simple, and it shaped everything that followed: if oil could be weaponized, Japan wanted more than the right to buy it. It wanted a claim on production. Buying crude on the spot market left the country exposed to embargoes and price swings. Owning stakes in producing fields offered a different kind of security—more reliable access, and more leverage with host countries.

That’s how Japan arrived at its distinctive model: not the American approach of mostly private oil majors battling for acreage, but a hybrid system. Government capital and diplomacy on one side, private-sector execution on the other—combined in service of a national strategic objective. INPEX would become the most visible product of that system.

The Two Bloodlines: Origins of INPEX's Predecessor Companies

INPEX didn’t start as one company. It was assembled—later—out of two very different lineages that grew up with the same national mission: secure energy for Japan. One bloodline learned to hunt overseas, starting in Indonesia. The other learned to produce at home, in some of the hardest geology Japan has to offer. Put them together and you get something unusual: a Japanese energy company with real global operating ambition and domestic infrastructure under its feet.

The Indonesia Pioneer: 1966–2000

The overseas story begins in 1966, with the founding of North Sumatra Offshore Petroleum Exploration Co., Ltd. The mandate was explicit: promote the independent development of overseas oil resources, under a contract signed with PERMINA (now PERTAMINA).

Even the name is revealing. Japan is a Tokyo-headquartered country with a deep-water coastline and little oil. Yet it launches an oil company whose identity is tied to North Sumatra—because the real “home field,” strategically, had to be somewhere else. Indonesia was the first frontier.

That early bet paid off quickly. In 1970, the precursor to INPEX discovered the Attaka field in Indonesia. For Japan, this was more than a commercial win. It was proof that Japanese-backed exploration could actually find and develop meaningful resources abroad.

Then came an even more consequential leap. In 1973, the company acquired the ADMA Block offshore Abu Dhabi—right as the Middle East was becoming the focal point of global energy politics. Through JODCO, its involvement in Abu Dhabi’s offshore industry began with participation in Umm Shaif and Lower Zakum. Over the following years, JODCO joined additional offshore developments: Upper Zakum in 1977, Umm Al Dalkh in 1978, and Satah in 1980.

The timing mattered. Just as the oil crisis was teaching Japan that hydrocarbons were geopolitical, not just economic, this company was laying down relationships in the Gulf that would last for decades. It wasn’t an accident. It reflected the broader Japanese model taking shape: diplomacy and state-aligned capital opening doors, with companies building credibility the only way that counts in oil and gas—by showing up, investing, and staying.

Teikoku Oil: The Domestic Champion

While that first lineage was learning how to operate overseas, the second was becoming Japan’s homegrown specialist.

Teikoku Oil Co., Ltd. was founded in 1941 as a semi-government company to unify the existing Japanese oil exploration companies. The origins were wartime, but the logic carried into peacetime: domestic production, however limited, was strategically valuable.

Teikoku’s defining breakthrough came in 1979, with the discovery of the Minami Nagaoka gas field in Niigata Prefecture—Japan’s largest natural gas reserves. Commercial production started in 1984 after the completion of the Koshijihara Plant, one of Japan’s largest gas processing facilities.

Minami-Nagaoka is located in the southwest of Nagaoka, Niigata. It was discovered in 1979 and later developed by INPEX. Even after more than 25 years of continuous output, it still accounted for roughly 40% of Japan’s total natural gas production.

That one field carrying such a large share of domestic output tells you two things at once: Japan doesn’t have much hydrocarbon endowment, and extracting what it does have requires serious technical capability. The gas is contained in volcanic rock—among the deepest in Japan—at roughly 4,000 to 5,000 meters below the surface. Development began in the late 1970s, the decision to develop the field was made in 1981, and by 1984 production was underway.

But Teikoku didn’t just produce molecules. It built the arteries that move them. INPEX operates the Naoetsu LNG receiving terminal in Niigata and a natural gas pipeline network of about 1,500 km connecting to customers across Japan. That network created direct relationships with utilities and industrial buyers—stable demand, steady cash flow, and a durable strategic position in the home market.

When these two companies ultimately came together—formalized in the 2008 merger that formed today’s INPEX—the fit was clean. One side brought decades of overseas exploration and long-built trust in places like Indonesia and Abu Dhabi. The other brought domestic production know-how and critical infrastructure. Together, they created Japan’s most complete upstream player: global in reach, but anchored at home.

The Year 2000: Three Discoveries That Changed Everything

In exploration, you can spend decades buying lottery tickets and never win. And then, in a single year, you hit three numbers that change your life.

For INPEX, that year was 2000. Over the span of twelve months, the company made three discoveries that fundamentally redirected its future: Kashagan in Kazakhstan, and Ichthys and Abadi in the Timor Sea.

Each one mattered on its own. Together, they gave INPEX something it had never truly had before: a pipeline of world-scale projects that could carry the company for decades—and, crucially, a path to becoming an LNG heavyweight.

Start with Ichthys. The gas and condensate sit in the Browse Basin, a few hundred kilometers off Australia’s northwest coast—far offshore, deep enough to be complex, but in a country with stable institutions and predictable rules. Discovered in 2000, Ichthys was developed by INPEX alongside a consortium that included Total, Tokyo Gas, Osaka Gas, Chubu Electric Power, Toho Gas, Kansai Electric Power, and CPC.

What made Ichthys different wasn’t just that it was big. It was big in a way that matched Japan’s needs. The Ichthys LNG Project’s production capacity is about 9.3 million tons per year—more than 10% of Japan’s annual LNG import volume—with roughly 70% of that LNG shipped to Japanese buyers.

Strategically, that combination is almost too perfect. A single project, supplying a meaningful slice of Japan’s LNG demand, sourced from Australia—an ally, a democracy, and a place with no reputation for sudden resource nationalism. If Japan’s post-1973 doctrine was “diversify and de-risk,” Ichthys looked like the doctrine made real.

Then there was Abadi. INPEX discovered the Abadi gas field in 2000 when the Abadi-1 exploratory well was drilled. It sits in Indonesia’s Arafura Sea, near Tanimbar in the Moluccas—and it carried a symbolic first: it was the first discovery of crude oil and natural gas in the Arafura Sea.

Abadi also came with sheer scale. Proven reserves were around 10 trillion cubic feet—enough to put it in the category of projects that can define a company. Alongside Ichthys, it offered a second shot at a world-class LNG development, and another major pillar for Japan’s supply diversification.

Underneath all of this was the same deeper reason these discoveries mattered: LNG was becoming Japan’s energy instrument of choice. Unlike crude oil, LNG doesn’t casually flow to whoever bids the highest that day. It depends on massive, specialized infrastructure—liquefaction plants, dedicated tankers, receiving terminals—that ties producers and buyers together for the long haul. For Japan, that “lock-in” wasn’t a risk. It was the point.

But these wins came with a brutal implication. Discovering giant fields is one thing. Building them is another. Until then, INPEX had largely played the role of minority partner—important, but not in charge. To fully capture the value of Ichthys and Abadi, INPEX would have to step up into the operator’s seat: making the big technical calls, managing contractors, and carrying the execution risk.

That realization set up the next act—the most consequential institutional move in the company’s history: a government-orchestrated consolidation designed to create a Japanese champion that could actually build projects on the scale it had just discovered.

The Government-Orchestrated Merger & IPO: 2004–2008

In the early 2000s, Japan’s policymakers looked at their upstream oil and gas sector and saw a problem hiding in plain sight: lots of effort, not enough heft. The Japan National Oil Corporation (JNOC) had helped finance dozens of overseas ventures, but they were scattered across project companies—each one too small to matter on its own. And JNOC itself had piled up heavy debts from exploration bets that didn’t always work.

So the plan became a two-step: bring INPEX into public markets, and then consolidate the industry around it—creating a national champion while also cleaning up JNOC’s balance sheet.

The first move came on November 17, 2004, when INPEX was listed on the first section of the Tokyo Stock Exchange. The catalyst was JNOC—by then reorganized into what is now the Japan Oil, Gas and Metals National Corporation—which held a 53.96% stake in INPEX and sold 343,725 shares, about 17.9% of the company’s 1.92 million outstanding shares. METI still owned 18.9%. This wasn’t Japan’s first upstream privatization step; it was the second, after Japan Petroleum Exploration Company’s listing in December 2003.

The IPO did what an IPO is supposed to do: it raised money and established a market valuation. But INPEX wasn’t being treated like just another newly public company. The government still considered it too strategically important to fully let go.

That’s where Japan reached for a tool you usually see in European privatizations: the golden share. Because INPEX played an important role in stable energy supply, the government kept an equity stake and retained a special class of share that could veto major corporate actions under certain conditions. In practice, it meant public shareholders could fund growth and demand discipline, but the state could still block decisions that might threaten energy security.

INPEX itself spelled out what this covered. Major corporate decisions requiring approval included the appointment or removal of directors, disposal of all or part of important assets, amendments to the Articles of Incorporation, mergers, share exchanges or share transfers, capital reductions, and dissolutions.

It was a neat resolution to an awkward contradiction. Japan needed INPEX to behave like a modern, globally competitive energy company—able to raise capital and partner internationally. But it also couldn’t accept the risk of losing control of a strategically vital operator to a hostile buyer. The golden share let Japan do both: commercialize the company without surrendering the steering wheel.

With the governance question handled, the second move followed: scale. On April 3, 2006, INPEX Corporation and Teikoku Oil agreed to form INPEX Holdings. The strategic logic was straightforward. INPEX brought decades of overseas upstream experience. Teikoku brought domestic production and infrastructure. Their asset bases and geographies didn’t just overlap; they complemented each other, expanding operating areas and diversifying country and currency risk.

On October 1, 2008, the merger was completed. The new INPEX Corporation was formed from INPEX Holdings, INPEX, and Teikoku Oil, and headquarters moved to Akasaka, Tokyo.

By 2008, Japan had what it had been trying to assemble for decades: a unified upstream champion with the breadth to operate internationally and the domestic backbone to matter at home. And the timing wasn’t theoretical. Ichthys was heading toward the decisions that separate “we found it” from “we built it.” Now, INPEX had the financial strength and organizational structure to attempt something it hadn’t done at this scale before: lead a world-class megaproject as operator.

The Iran Gamble & American Pressure: 2004–2010

Before INPEX could go all-in on Ichthys, it got a different kind of education: a crash course in the limits of energy independence when geopolitics is the real operator.

The setting was Iran’s Azadegan oil field, the country’s largest onshore field, with more than 30 billion barrels of oil in place. For Japan’s energy-security planners, Azadegan looked like the ultimate prize: a direct, equity-backed stake in huge Middle Eastern reserves. And INPEX wasn’t just participating. It initially held a 75% stake and was set to be the operator.

Then the ground shifted. In 2006, as the United States stepped up pressure on allies to curb business ties with Iran over its nuclear program, the project’s structure changed. INPEX ended up parting with most of its interest to its partner, the National Iranian Oil Company, after delays in getting development work started. The result was a dramatic downgrade—from majority owner and operator to a small minority position. From then on, INPEX held a 10% interest, while NIOC owned the remainder and operated the field.

That reduction would have been painful under any circumstances. But it wasn’t the end of the story. By 2010, new U.S. sanctions created a direct threat to INPEX’s broader business. INPEX feared sanctions would hamper its ability to raise money from U.S. institutions and complicate its global projects. On October 15, the company confirmed it would withdraw from the Azadegan project, saying it had reached an agreement with Iran’s state oil company for its subsidiary to exit.

Financially, the immediate hit was containable. INPEX had invested $153 million in the project, and it said the agreement would have only a limited impact on earnings. Strategically, it was a punch to the solar plexus. Azadegan had been a flagship example of Japan pursuing energy security through equity oil. And now it was a reminder that in a unipolar world, commercial logic could be overridden—quickly—by alliance politics. The U.S. response made the message explicit: INPEX’s withdrawal was welcomed, and it underscored “that there are risks in dealing with Iran.”

The takeaway for INPEX was blunt. Japan could pursue energy security, but not in ways that collided with American strategic priorities. And that lesson didn’t stay theoretical. It shaped where INPEX leaned in next: toward places where geopolitics and commerce aligned, rather than conflicted.

Australia fit that profile almost perfectly: stable institutions, rule of law, and a close security relationship with both Japan and the United States. Azadegan was a painful detour. But it also cleared the deck—concentrating INPEX’s attention on Ichthys, the project that would define what the newly consolidated company could actually do.

The Ichthys Megaproject: INPEX's Defining Bet

Imagine you’re running Japan’s largest upstream company in 2006, staring at a discovery that could define your career—and your country’s energy strategy. The resource is real: roughly 3 billion barrels of oil equivalent in Australia’s Browse Basin. But turning that into LNG cargoes for Japan would mean building a system that stretches from deep offshore wells to an onshore liquefaction plant, connected by a pipeline longer than most countries.

For INPEX, this wasn’t just “the next project.” It was the moment the company either became a true operator of world-scale LNG—or proved it couldn’t.

Partnering for Success

INPEX made a move that signaled both ambition and realism: in August 2006, it agreed to transfer a portion of its interest in the project to Total S.A.’s subsidiary Total E&P Australia. After farming out 24% of the permit ownership to Total, the concept and location were changed.

The logic was straightforward. INPEX hadn’t led an LNG megaproject before, and it didn’t yet have the institutional muscle memory for a development this complex. Total did. Bringing in a partner with hard-won LNG experience wasn’t just about sharing risk; it was about importing capability.

Total and INPEX have a long and successful history of working together all around the world. We are delighted to launch this world-scale project and to support it with our technical expertise and our best-in-class competencies in the management of very large projects.

By January 13, 2012, the partnership was ready to cross the point of no return. In Paris, Total and INPEX announced they had taken the final investment decision for Ichthys LNG—an investment of US$34 billion.

The Engineering Marvel

What they sanctioned was an integrated industrial chain, built at the edge of what’s practical. Ichthys LNG is ranked among the most significant energy projects in the world, with the joint venture formed between INPEX group companies (the Operator with a 67.82% interest), major partner TotalEnergies (26%), and the Australian subsidiaries of CPC Corporation Taiwan (2.625%), Osaka Gas (1.2%), Kansai Electric Power (1.2%), JERA (0.735%) and Toho Gas (0.42%).

At the center is a simple but brutal requirement: move gas from a remote offshore field to a liquefaction plant near Darwin. The solution was one of the longest subsea export lines ever attempted. Ichthys LNG’s 890-kilometre gas export pipeline (GEP) delivers gas and some condensate from the Ichthys Explorer central processing facility (CPF) in the Browse Basin to onshore processing facilities at Bladin Point near Darwin, in preparation for export. The GEP is the longest subsea pipeline in the southern hemisphere. It is 42-inch in diameter and composed of about 700,000 tonnes of steel and coated with 550,000 tonnes of concrete. Saipem served as the engineering, procurement, construction and installation (EPCI) contractor for the GEP.

Onshore, production of LNG is facilitated through an onshore liquefaction plant located at Bladin Point, near Darwin, connected to the offshore Ichthys field by an 889 km subsea pipeline. The LNG plant has a nominal plant capacity of 8.9 million tonnes per annum, achieved through two LNG processing trains.

By any measure, Ichthys was a giga-project, with an initial project cost of US$34 billion.

Cost Overruns and Timeline Delays

Of course, it didn’t go cleanly.

By January 2012, INPEX said the project near Darwin would cost about $34 billion—around 60% higher than INPEX’s original estimate of $20 billion. That kind of overrun kills many developments. Ichthys survived it.

Part of the reason was commercial discipline: INPEX had secured long-term LNG sales contracts before the project was sanctioned, making the economics less fragile than they would have been if the venture depended on future spot prices.

The schedule slipped too. The original plan targeted production by late 2016. First gas was achieved on 30 July 2018. The first condensate cargo followed on 1 October 2018, and the first LNG cargo shipped on 22 October 2018.

The delay added pain and cost, but it didn’t change the core outcome: INPEX had taken on one of the world’s most complex energy developments—and finished it.

Why Ichthys Mattered

Ichthys mattered because it turned Japan’s energy-security theory into physical infrastructure. Notably, the entire annual production of LNG from the Ichthys project (8.4 million tons per year) had already been sold for 15 years under oil-linked price contracts, mostly directed to third-party consortiums of Taiwanese and Japanese buyers including INPEX.

That pre-selling was the financial foundation. Long-term, oil-linked contracts created predictable cash flows, which made it possible to fund and defend a multi-decade investment through cycles, politics, and inevitable execution surprises.

A final investment decision was reached in 2012 and production commenced in July 2018. Ichthys LNG produces up to 9.3 million tonnes of LNG and 1.65 million tonnes of LPG per annum, along with more than 100,000 barrels of condensate per day at peak. It is one of the few energy projects worldwide to incorporate the whole chain of development and production: subsea, offshore, pipeline and onshore.

And for INPEX, the strategic transformation was the real product. By delivering Ichthys, it moved from a portfolio of minority stakes into a credible LNG operator. The project generates substantial cash flows and is expected to deliver benefits to Australia for the next 40 years.

Just as importantly, Ichthys built a new internal playbook—how to manage gigantic contractor ecosystems, work through Australia’s regulatory environment, and commission highly complex LNG facilities. That operational scar tissue would shape how INPEX approached what came next, including the Abadi development in Indonesia.

The Indonesia Setback & Abu Dhabi Success: 2016–2020

Even as Ichthys was grinding toward startup, INPEX was getting a reminder of another oil-and-gas truth: finding molecules is only half the job. The other half is keeping the right to produce them. And that part can change with an election, a policy shift, or a host country deciding it wants a bigger share.

Losing the Mahakam Block

In 2018, the Government of Indonesia nationalized the Mahakam Block—one of the original pillars of INPEX’s Indonesia story. Operations shifted to Pertamina.

Losing Mahakam wasn’t just losing cash flow. It was losing a piece of the company’s origin story. This was the lineage’s home turf, the place where its predecessor had struck oil in 1970 and proved Japan could succeed as an overseas explorer. Watching that block transition to the national oil company landed as both a commercial setback and an emotional one—a reminder that in upstream, “long term” only lasts as long as the concession does.

It also fit a broader regional pattern. As countries build their own technical capability and face domestic pressure to capture more value from natural resources, foreign-held concessions get renegotiated, restructured, or simply taken back. Mahakam was INPEX learning—again—that the rules of the game aren’t set by markets alone.

Doubling Down on the Gulf

If Indonesia was getting tougher, Abu Dhabi kept signaling the opposite: stay, invest, and we’ll keep building together.

For more than 40 years, INPEX and its Abu Dhabi-focused subsidiary, JODCO, had been a strategic partner to ADNOC. That relationship started in 1973 with participation in Umm Shaif and Lower Zakum. Over the years, JODCO expanded into additional offshore developments—Upper Zakum in 1977, Umm Al Dalkh in 1978, and Satah in 1980—creating the kind of trust that’s hard to replicate and impossible to buy quickly.

In the modern era, that trust translated into renewed access. In 2015, INPEX was awarded a 5% interest in the Abu Dhabi Onshore Concession. In 2018, it was awarded a 10% interest in the new Lower Zakum offshore concession. At the same time, it extended its 40% stake in Satah and increased its interest in Umm Al Dalkh from 12% to 40%.

There’s a national-security subtext running under all of this. The UAE supplies about 25% of Japan’s crude oil imports. When a quarter of your supply comes from one country, “partnership” stops being a corporate buzzword and starts functioning like infrastructure.

INPEX also pushed into new territory. Its subsidiary Jodco Exploration (JEL) secured a production concession for Onshore Block 4 in Abu Dhabi. That award traced back to ADNOC’s first competitive bid round in 2018, which granted exclusive exploration rights. After drilling in 2021, multiple oil, condensate, and gas reservoirs were discovered, and the production concession strengthened INPEX’s Middle East portfolio even further—an expansion built on decades of showing up and staying.

The Abadi Project Saga

While managing a loss in Indonesia and compounding wins in the Gulf, INPEX kept working on its next defining LNG development: Abadi.

Abadi sits in Indonesia’s Masela Block, and it’s big enough to matter—an asset that, if executed, could become Ichthys’s counterpart in the company’s portfolio. The plan centered on an onshore LNG facility fed by the Abadi Gas Field, targeting production of about 9.5 million tons of LNG per year, along with condensate and pipeline gas. Indonesia approved an initial plan of development in 2019.

Then the project evolved. INPEX decided to introduce CCS, positioning Abadi to be cleaner, more competitive over the long run, and more aligned with the direction global LNG buyers were moving. A revised development plan was submitted in April 2023 and approved in December 2023. That same year, the partnership expanded: Pertamina and Malaysia’s PETRONAS joined the project in October 2023.

By August 4, 2025, INPEX—through INPEX Masela Ltd.—announced the start of Front-End Engineering and Design (FEED), the work that turns “approved concept” into “buildable project.” CEO Takayuki Ueda said Indonesia was pressing to accelerate the roughly $20 billion development as domestic and regional gas demand rose, with a final investment decision still targeted for 2027 despite cost pressure.

If Ichthys was proof INPEX could build one world-scale LNG system from scratch, Abadi is the sequel that would turn capability into repeatability. Do it again—secure the partners, lock in offtake, manage execution—and INPEX doesn’t just have a great project. It has a durable LNG engine that can run deep into the middle of the century.

The Net Zero Pivot & Vision 2035

By the mid-2020s, INPEX was staring at the same hard puzzle facing every upstream producer: how do you keep doing what you’re good at—delivering reliable oil and gas—while the world is demanding fewer emissions and a different end-state?

INPEX’s answer came in the form of INPEX Vision 2035, and it’s noticeably pragmatic. It doesn’t read like the full-speed pivot some European majors attempted. It also doesn’t dismiss the transition the way some producers have. Instead, INPEX frames the next decade as a both-and strategy: keep supplying energy, and decarbonize the way that supply is produced and used.

"INPEX's mission is to continue sustaining a stable supply of energy primarily through oil and natural gas, while making tangible contributions toward the decarbonization of society."

The company’s view is that there isn’t one universal pathway to net zero. What works in one region may not in another, and the realistic route forward is to bolt low-carbon solutions onto the system that already exists—integrating carbon capture and storage (CCS) with oil and gas production, and scaling lower-carbon fuels like blue hydrogen and ammonia, rather than betting everything on renewables alone.

That philosophy shows up directly in where INPEX says it will put its effort: expand natural gas and LNG, strengthen LNG trading and marketing, deploy CCS and hydrogen at commercial scale, and build out integrated power and renewables businesses with the balancing technologies needed to make them dependable.

Internally, the organization was set to reflect that shift. The Hydrogen & CCUS Development Division would be restructured into the Low Carbon Solutions Division, while the Renewable Energy Division would be renamed as the Renewables, Power & Energy Solutions Division.

Concrete Projects

This isn’t presented as a branding exercise. INPEX has tied the strategy to specific projects and partnerships.

In Japan, the company planned a blue hydrogen and ammonia production and usage demonstration project in Kashiwazaki, Niigata Prefecture, with startup targeted for 2025. It also stated an ambition to integrate CCS into its operated LNG projects to cut greenhouse gas emissions, including plans described as Ichthys CCS (around 2.0 Mtpa) and Abadi CCS (around 1.5 Mtpa).

INPEX also moved beyond its own assets to help build shared CCS infrastructure. It completed a business feasibility study for adoption of the Tokyo Metropolitan Area CCS Project and the Tohoku Region West Coast CCS Initiative Project under JOGMEC’s 2023 Survey on Implementation of Advanced CCS Projects. Both were then adopted under the 2024 Engineering Design Work for Advanced CCS Projects.

And INPEX leaned into Australia again—this time not for LNG, but for carbon storage. The company held a 53% participating interest, as operator, in a greenhouse gas storage assessment permit (title G-7-AP) alongside TotalEnergies CCS Australia (26%) and Woodside Energy (21%) in the Bonaparte CCS Assessment joint venture. The permit, awarded following Australia’s 2021 Offshore Greenhouse Gas Storage Acreage Release, sits in the Bonaparte Basin off the northwest coast of the Northern Territory. The pitch is strategic: a potential large-scale, multi-user carbon storage hub located close to Asia.

Renewable Energy Expansion

The most visible outward expansion, though, has been renewables—particularly in Australia. In late 2023, INPEX acquired a 50% stake in Enel Green Power Australia. Then in late 2024, the business rebranded to Potentia Energy, marking the next phase of the Enel-INPEX joint venture.

The attraction was speed and capability. Through the partnership, INPEX gained immediate exposure to operating renewables—wind, solar, storage, and hybrid projects—plus expansion into innovative solutions within retail and trading operations.

At the time, the renewables platform included four operating solar plants totaling 310 MW across South Australia and Victoria, plus a 75 MW wind farm in Western Australia. A 93 MW solar farm in Victoria was under commissioning, and financial close had been announced for a 98 MW solar and 20 MW battery hybrid project in New South Wales. The company also had rights secured for a development pipeline of more than 7 GW across Australia.

It’s consistent with INPEX’s broader playbook: don’t relearn everything from zero if you can partner your way up the curve. With Enel’s track record and an existing Australian operating base, INPEX could participate in renewables with a running start—while keeping its core identity anchored in gas and LNG.

INPEX also stated it would collaborate with supply chain stakeholders to reduce Scope 3 emissions. Through low-carbon initiatives leveraging CCS and hydrogen, as well as renewable energy projects, it aimed to contribute to a reduction of 8.2 Mtpa in GHG emissions.

Playbook: Business & Strategic Lessons

INPEX’s sixty-year evolution leaves a pretty clear set of lessons—less the usual “best practices,” and more a field guide for what it takes to survive, and win, in the most capital-intensive corner of the global economy.

Patience as Strategy: Ichthys was discovered in 2000, and the first LNG cargo didn’t sail until 2018. Eighteen years is an absurd timeline in most parts of business. In upstream energy, it’s often the price of admission. The companies that capture outsize value aren’t always the ones that find resources first—they’re the ones that can keep funding, negotiating, engineering, and executing long after the excitement of discovery fades.

Government Alignment: INPEX’s ownership structure is a feature, not a bug. The golden share and METI’s meaningful stake give the company room to make decisions on multi-decade horizons that many purely private operators would struggle to justify. But that same structure also puts guardrails around strategy. Capital allocation isn’t just a question of returns; it has to rhyme with Japan’s national energy-security priorities.

Operator vs. Minority Partner: For years, INPEX built its portfolio largely by taking pieces of other people’s projects. Ichthys marked the shift from participant to operator—and that shift is never just a change in title. It requires deep bench strength in project management, contractor oversight, and regulatory navigation. Those capabilities don’t appear overnight; they’re accumulated, painfully, across cycles. Ichthys became a kind of internal operating system that INPEX can now apply to Abadi and whatever comes after.

Geographic Diversification: INPEX spread itself across Indonesia, Australia, the UAE, Kazakhstan, and Norway not out of wanderlust, but as insurance. Resource nationalism is real, and it’s not predictable. The Mahakam nationalization hurt—but it wasn’t fatal—because the company had built meaningful positions in places that were moving in the opposite direction, especially Abu Dhabi and Australia.

Technology Absorption: The Total partnership on Ichthys is a reminder that in megaprojects, capability can be more valuable than ownership percentage. INPEX gave up equity, but it bought execution expertise and large-project muscle memory—exactly what you need when you’re trying to build an LNG system at the edge of feasibility.

Long-term Contracting: INPEX de-risked Ichthys by locking in long-term, oil-linked sales contracts before final investment decision. That trade comes with an obvious downside: you give up some upside if spot prices rip higher. But it buys something that matters more when you’re committing tens of billions of dollars: predictable cash flows that can support financing, steady operations, and shareholder returns through the inevitable volatility.

Porter's Five Forces & Hamilton's 7 Powers Analysis

Porter's Five Forces

Threat of New Entrants: LOW

Breaking into INPEX’s world isn’t just hard—it’s structurally unlikely. Start with the check you have to write: Ichthys alone was a roughly $34 billion undertaking, and Abadi is discussed in the tens of billions too. But money is only the entry fee. A would-be challenger also needs deepwater and LNG know-how, regulatory credibility that takes years to earn, and host-government relationships that are built on long memory and consistent behavior. Add in multi-year approval processes for major LNG projects, and the industry effectively builds a moat around incumbents.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers: MODERATE

A project like Ichthys forces you into a small universe of specialist suppliers. Contractors like Samsung Heavy Industries, JGC, Chiyoda, and Saipem have the capabilities to build LNG facilities, offshore structures, and subsea pipelines at the required scale. That specialization gives them leverage.

But it’s not a monopoly. Korean, Japanese, and Chinese yards and contractors compete hard for marquee work, which keeps pricing power in check. And INPEX’s size matters: when you can offer repeat business across years and projects, you negotiate from a different position than a one-off developer. Ichthys also proved a subtle point: supplier power can create pain, but it doesn’t necessarily stop execution.

Bargaining Power of Buyers: MODERATE-LOW

Ichthys is largely sold before the LNG even leaves the plant. The entire annual production—about 8.4 million tons per year—was locked up under 15-year, oil-linked contracts, mostly with Taiwanese and Japanese buyer groups.

That’s the real story of buyer power here. Japanese utilities don’t negotiate like purely commercial buyers, because their incentive function includes security of supply. They accept long-duration commitments and oil-linked pricing in exchange for predictability. And because INPEX has limited exposure to the spot market through these arrangements, buyers have fewer levers to pull once contracts are signed.

Threat of Substitutes: RISING

The substitute threat is no longer hypothetical. Renewables keep getting cheaper and more widespread, but intermittency still limits how far they can replace firm supply without storage and grid upgrades. Japan’s potential nuclear restart also matters: each reactor that returns reduces incremental LNG demand, even if public acceptance remains contested.

Over the longer arc, hydrogen is the most meaningful substitute candidate—particularly if it scales in industrial and power applications. INPEX’s approach is to hedge: keep leaning into gas and LNG while investing in hydrogen and CCS to stay relevant as demand shifts.

Competitive Rivalry: MODERATE

Domestically, INPEX’s notable competitors include Japan Petroleum Exploration (JAPEX) and ENEOS Xplora. INPEX is also JAPEX’s primary domestic rival, and its larger financial scale supports more aggressive participation in large, capital-heavy international projects.

That said, the rivalry doesn’t look like consumer markets where companies fight for every inch of share. In upstream energy, competition is often fiercest at the moment of access—winning licenses, securing concessions, and forming consortiums. Once projects are in production, the competitive pressure tends to ease, and cooperation via joint ventures is common. In many host countries, decades of relationship-building function as a form of competitive insulation that new competitors can’t quickly reproduce.

Hamilton's 7 Powers

Scale Economies: Ichthys’s roughly 9.3 million tonnes per annum capacity gives it meaningful scale advantages. When you spread fixed costs over massive volumes, incremental cargoes tend to carry stronger economics. If INPEX can add another large pillar like Abadi, those benefits can compound.

Network Effects: INPEX doesn’t have classic network effects, but it does have something adjacent: infrastructure gravity. Its approximately 1,500-kilometer domestic pipeline network creates a kind of lock-in for connected customers, because alternative supply often isn’t just a phone call away—it requires physical re-routing.

Counter-Positioning: INPEX’s quasi-sovereign structure enables strategies that many purely private companies struggle to defend. With government backing and the golden share framework, the company can pursue investments with multi-decade paybacks and strategic value, even when the near-term market would prefer a faster return.

Switching Costs: Long-term LNG contracts create real switching costs. Buyers often make their own infrastructure and planning decisions around committed supply, and walking away mid-contract is economically painful and operationally disruptive.

Branding: INPEX doesn’t “brand” in the consumer sense. Its brand is reputation—earned with host governments, national oil companies, and partners. The multi-decade relationship with Abu Dhabi is a prime example: trust becomes an asset, and it’s one competitors can’t simply buy.

Cornered Resource: INPEX and its Abu Dhabi-focused subsidiary JODCO have been strategic partners in the UAE for more than 40 years. Those relationships function like a cornered resource: preferential access and repeat opportunities that flow from sustained presence and performance, not from winning a single auction.

Process Power: Ichthys built institutional capability—how to run a megaproject, manage contractors at enormous scale, navigate regulation, and commission complex LNG facilities. INPEX’s partnership with Total helped accelerate that learning. And once a company has that “how,” it transfers: the process gets reused, refined, and applied to the next development.

Bull vs. Bear Case & Key Risks

Bull Case

In its consolidated results for the year ended December 31, 2024, INPEX reported a clear step up in performance: revenue rose year over year, operating profit increased, and profit attributable to owners of the parent jumped sharply. The headline isn’t the exact percentages. It’s what they signal: Ichthys is throwing off cash, the portfolio is working, and the company has room to fund what comes next.

The bull case is that INPEX sits in a rare position for an upstream producer: long-life, strategic assets—plus a credible path to another world-scale growth project.

Ichthys delivers stable cash flows for forty years. After years of construction drama and delay, the asset is now running in steady-state. That matters because Ichthys isn’t just production; it’s the cash engine that can underwrite dividends, debt service, and new investment—without INPEX having to bet the company every time it wants to grow.

Abadi offers transformative growth. Abadi is the kind of project that can reset INPEX’s scale. The plan targets about 9.5 million tonnes per year of LNG. With FEED underway and a final investment decision targeted for 2027, the development is moving from “concept” to “execution.” And because it’s in Indonesia—where gas demand is rising and the government wants development—the political wind is, for now, at INPEX’s back.

Abu Dhabi keeps rewarding patience. INPEX’s concession wins and extensions in Abu Dhabi are the payoff from a relationship built over decades. This isn’t only commercial. The UAE supplies about a quarter of Japan’s crude imports, so INPEX’s position there carries strategic weight. In a capital-heavy industry, being seen as a long-term, reliable partner can translate into repeat access—arguably the scarcest advantage of all.

The transition strategy creates optionality, not a cliff. The Potentia Energy partnership gives INPEX real operating exposure in renewables and a large development pipeline, without forcing the company to abandon what it does best. Meanwhile, CCS and hydrogen efforts are a hedge against a world where “gas is good” becomes “gas must be clean.” If LNG buyers and regulators start paying a premium for lower-carbon supply, INPEX wants to be ready.

Government backing is a feature. INPEX’s structure—the government stake plus the golden share—reduces certain existential risks, like a hostile takeover or a strategy that drifts away from Japan’s energy-security priorities. It can also provide credibility in host countries where national interest and energy policy are never far from the negotiating table.

Bear Case

Oil and gas price volatility still runs the show. Even with long-term contracts, INPEX’s earnings ultimately move with hydrocarbon prices. A prolonged downcycle—weak demand, oversupply, or both—would pressure cash flow and could force harder choices on spending, dividends, and the pace of new developments.

Abadi execution risk is real. Greenfield LNG projects are where budgets go to die. Ichthys itself ended up massively above the original estimate and came online later than planned. Abadi could face the same: remote logistics, complex engineering, and the inevitable friction of large consortium projects. If costs rise faster than expected or timelines slip, returns can degrade quickly.

Resource nationalism doesn’t disappear; it just rotates. Mahakam was a reminder that host countries can and do change the rules. Bringing in partners like Pertamina and PETRONAS can help align incentives, but it doesn’t eliminate political risk. In upstream, the asset isn’t truly yours—you’re renting it from a government, and the lease terms can change.

The energy transition could move faster than INPEX is assuming. If renewables and storage keep improving and carbon constraints tighten, gas demand could peak earlier than expected in key markets. That raises the uncomfortable possibility of stranded or underutilized assets—not tomorrow, but within the life of projects designed to run for decades.

Regulatory and operational risk comes with the territory. LNG plants and offshore facilities operate under intense environmental scrutiny. A serious incident—especially at a flagship like Ichthys—could lead to regulatory delays, lawsuits, community opposition, and reputational damage that spills into future project approvals.

Key KPIs to Monitor

For anyone tracking INPEX, three numbers do a lot of explanatory work:

-

Net production volume (BOE/day): This is the simplest read on whether the asset base is doing its job. Management’s forecast for 2025 is around 638,000 BOE per day. Over time, the big question is whether production grows as new projects come online, and whether actual volumes hit guidance.

-

Ichthys segment profit (¥ billion): Ichthys is the company’s center of gravity, so its profitability largely dictates consolidated performance. INPEX’s FY2025 forecast for Ichthys segment profit is about ¥260 billion. If this number stays resilient, the whole story stays funded.

-

Net debt to equity ratio: Megaprojects can either build wealth or quietly trap a company in leverage. Watching net debt relative to equity is a quick way to gauge financial flexibility—especially as Abadi spending ramps. The key question is whether INPEX can fund growth without overextending the balance sheet.

Conclusion

INPEX is, in many ways, Japan’s sixty-year answer to a single, uncomfortable fact: the country can’t fuel itself.

It began as North Sumatra Offshore Petroleum Exploration, a small, purpose-built vehicle with a contract to hunt for oil and gas off Indonesia. Over the decades, it grew in lockstep with Japan’s energy anxieties and ambitions—moving from frontier exploration to long-lived concessions in the Gulf, then into the operator’s chair on Ichthys, one of the world’s largest LNG megaprojects.

The pattern is consistent. The 1973 oil crisis created the urgency. Government industrial policy built the scaffolding. And patient capital—willing to wait through long timelines, political turbulence, and cost blowouts—made the projects real. Today, INPEX produces around 230 million barrels of oil equivalent a year and holds a reserve base intended to support production for decades.

But the nature of the problem is changing. The world that shaped INPEX—one defined by security of supply above all else—is now being reshaped by a second constraint: decarbonization. INPEX’s response is a pragmatic hedge. Keep delivering oil and gas, especially LNG, while investing in CCS, hydrogen, and renewables. Implicitly, it’s a bet that the transition will be managed, not sudden—and that “cleaner molecules” will remain valuable for a long time.

For investors, that creates a clear proposition. You’re buying into long-duration energy infrastructure with a degree of Japanese government backing. Ichthys provides the cash-generating core, supported by long-term contracts. Abadi is the next growth pillar if it reaches final investment decision and execution holds. And the Potentia Energy platform offers a real foothold in renewables without requiring INPEX to abandon what it’s built its competence around.

The risks don’t go away: commodity cycles still matter, megaproject execution can still bite, and the energy transition could accelerate in ways that compress demand or margins. INPEX has shown, across multiple decades, that it can stay focused and keep compounding through those cycles. Whether it can do that again will hinge on doing the hard things well—delivering Abadi, managing geopolitical exposure, and turning its low-carbon investments into something more than optionality.

The underlying driver, though, hasn’t changed. Japan remains a resource-poor island nation in a world where energy is strategic. As long as that geographic reality holds, Japan will need companies like INPEX to secure supply from abroad. The investor’s question is whether INPEX can keep earning strong returns while continuing to serve that national mission.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music