China Hongqiao: The Rebel Power Plant That Smelted Aluminum

I. Introduction: The "Congealed Electricity" Thesis

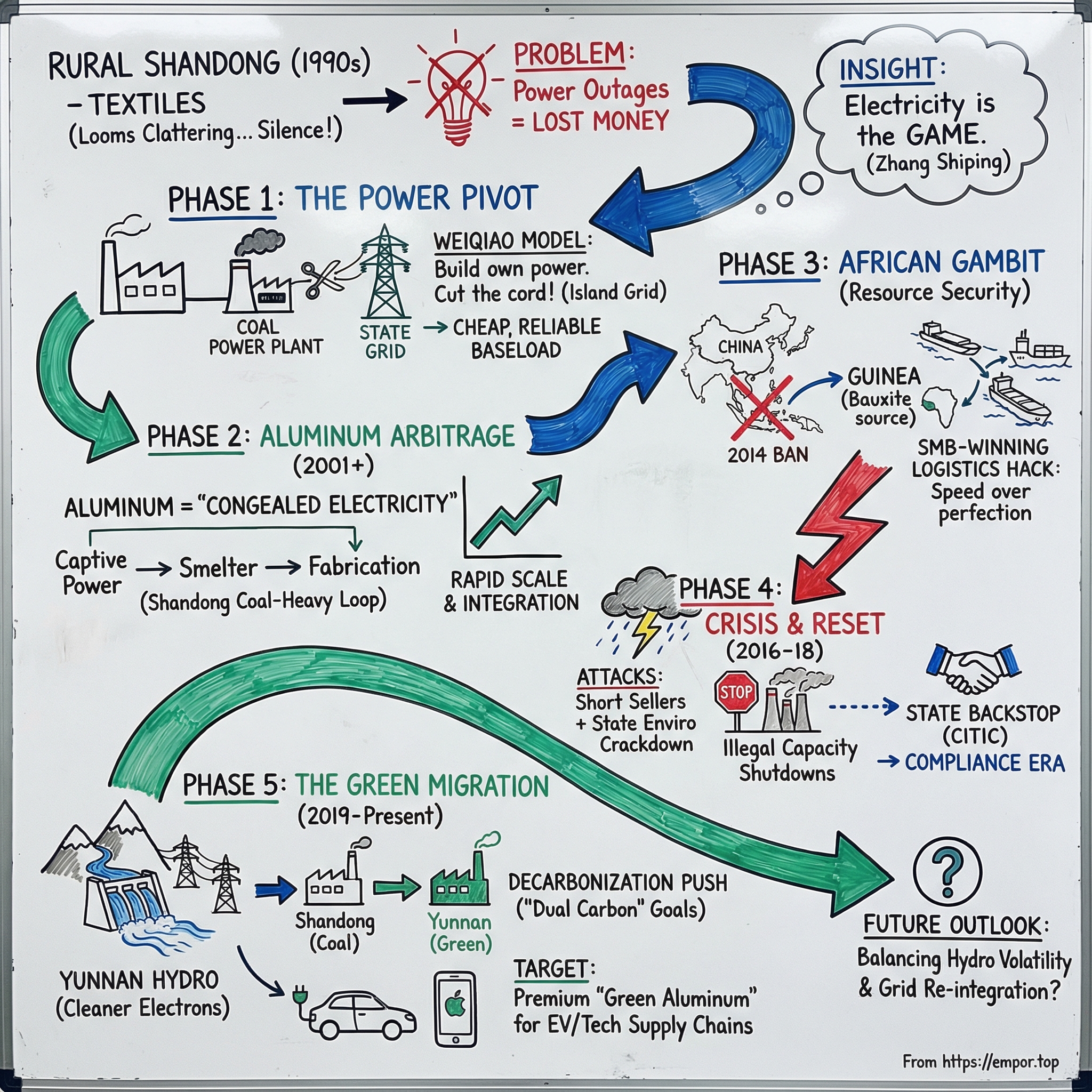

Picture a factory manager in rural Shandong in the early 1990s, standing on a gritty textile floor, listening to looms clatter… and then fall silent. Again. The State Grid has cut out for the third time this month. The spindles wind down, the line goes idle, and every minute the lights are off, money leaks out of the building.

Zhang Shiping watches it happen and lands on a conclusion that sounds obvious in hindsight, but wasn’t obvious to most manufacturers then: electricity isn’t just another cost on the ledger. It’s the whole game.

That insight is the starting gun for China Hongqiao Group. On paper, Hongqiao’s rise makes no sense in China’s industrial order. It began in textiles—towels, denim, low-margin factory work—and ended up beating the giants of the state sector at their own heavy-industry sport, becoming the world’s largest aluminum producer. One of the most audacious pivots in modern manufacturing didn’t come from a lab, or a patent, or a management consulting playbook. It came from a factory manager who got tired of the power going out.

Here’s the key idea that holds the entire story together: aluminum isn’t really a metal business. It’s an energy business. Smelting aluminum takes an enormous amount of electricity—so much that power is often the biggest single input cost, commonly around a third of the total. If you can consistently get cheaper, more reliable electricity than everyone else, you don’t just have a better factory. You have a structurally better business. Aluminum, in this framing, is “congealed electricity.”

Zhang founded Shandong Hongqiao in 1994 as a denim manufacturer. The aluminum push began in 2001, fueled by access to onshore credit and, crucially, by power he could control. What he discovered—and then exploited with founder-level intensity—was a regulatory opening that let industrial companies generate their own electricity under the banner of “co-generation” for steam and heat. Zhang didn’t merely add a power plant to his factory. He cut the cord. He built an island grid and severed the connection to the State Grid entirely. That one decision created a cost advantage so deep it could overwhelm scale, incumbency, and state backing.

China Hongqiao Group Limited, headquartered in Binzhou, Shandong Province and listed in Hong Kong, grew out of those textile roots and scaled into one of the world’s biggest producers of primary aluminum. In roughly a decade and a half, it built smelting capacity that exceeded five million tonnes—industrial heft that would have sounded implausible when it was still making denim.

And now, Hongqiao is in the middle of another reinvention. The coal-heavy model that made it unbeatable in Shandong has become a liability in an era of emissions targets and tightening regulation. So the company has been relocating up to two million tonnes of smelting capacity to hydropower-rich Yunnan Province, with production beginning there in 2020 and a goal of lifting renewables to more than thirty percent of its overall electricity mix. The same company once labeled a symbol of “dirty” aluminum is trying to become a green aluminum champion—positioning itself for electric vehicles, global supply chains, and a world that increasingly cares where electrons come from.

At its core, the Hongqiao story is about regulatory arbitrage, vertical integration, and founder-driven aggression. It’s about a family that built a private industrial empire by moving faster than the rules, then negotiating from a position of strength when the state eventually caught up. It’s a masterclass in commodity economics, logistics, and the peculiar, hard-edged capitalism of reform-era China.

II. The Origins: From Cotton to Kilowatts (1994-2000)

To understand Zhang Shiping, you have to start with Zouping County: flat farmland in Shandong province, far from the glass-and-steel China of Shanghai and Beijing. This is not a story about venture capital or flashy consumer brands. It’s a story about factory floors, coal dust, and operators who get rich by obsessing over the unglamorous details.

In 1981, at 35 years old, Zhang was promoted to general manager of Zouping’s No. 5 Cotton Ginning plant. For the next thirteen years, he lived inside the math of manufacturing: thin margins, finicky machines, and input costs that could swing profits from black to red. He learned a commodity truth that would shape everything that came after: when you’re selling something undifferentiated, pennies matter. And one input mattered more than the rest—electricity.

Textiles in 1990s China were a knife fight. Thousands of mills chased the same orders, and the winners weren’t the most visionary; they were the most efficient. In 1994, Zhang and other managers set up their own cotton-processing business, Weiqiao Textile Co. Over time, it would grow into the world’s largest cotton-yarn and denim maker, and it would list in Hong Kong in 2003.

But even as Weiqiao found success, it ran into a wall that every industrialist in China understood: the State Grid. Power was expensive. It was unreliable. Outages didn’t just dim the lights; they stopped production, idled workers, and blew delivery schedules. And even when electricity did arrive, it carried layer upon layer of costs—transmission fees, distribution charges, and the inefficiencies of a giant state monopoly. Everyone suffered under the same constraint. Zhang couldn’t accept that no one was doing anything about it.

In 1999, Shandong Weiqiao Pioneering Group entered power generation, producing more than 200 million kilowatt-hours of electricity annually. This was the first real inflection point. Zhang spotted a policy opening that allowed industrial companies to run small “co-generation” plants—on the theory that factories needed both steam and electricity. On its face, it was reasonable. Zhang’s interpretation was anything but.

He didn’t build a small add-on unit. He built a real thermal power station. Then came the move that turned an internal cost fix into a corporate superpower: he cut the wires to the State Grid. Weiqiao effectively built its own island grid—a private electrical network operating outside the national system.

This became the foundation of what people later called the “Weiqiao Model”: vertical integration built around generating and distributing your own power. It gained national attention in 2012, when it was reported that Weiqiao had been selling surplus electricity to local businesses for roughly one-third less than the State Grid’s price.

The advantage was enormous. With coal bought at market prices and burned in efficient, modern facilities running at high utilization, Weiqiao could generate electricity at roughly 30–50% below the grid’s rates. This wasn’t just a way to protect textile margins. It was the kind of cost gap that can decide an entire industry.

And the audacity wasn’t only technical—it was political. The State Grid held what was, in principle, a monopoly on generation and distribution. Private generation for on-site use could be tolerated. Running an independent grid, and selling power beyond your own factory gates, lived in a murky gray zone. Zhang navigated that gray zone with local relationships, economic leverage, and a simple willingness to act first. He didn’t so much break the rules as outrun them.

That instinct—move faster than regulations can be written, then negotiate once the business is too economically important to unwind—would become the Zhang family’s signature. By the time anyone could have meaningfully intervened, Weiqiao was already woven into the local economy: a major employer, a major taxpayer, and a machine that the region depended on.

The early governance matched the style. Zhang Shiping’s wife, Zheng Shuliang, served as vice chairperson, and his children, Zhang Bo and Zhang Yanghong, sat on the board. It wasn’t subtle, and it wasn’t accidental. Tight family control meant speed, secrecy, and alignment—no committees, no internal politics, no hesitation when the next big bet appeared.

For textiles, the new power business solved the immediate problem. But it created a new one: Zhang had built more generating capacity than looms and spindles could ever consume. He’d secured cheap, reliable baseload electricity—and now he needed a way to use it.

So the question shifted from survival to strategy: what industry could absorb huge amounts of power, twenty-four hours a day, and turn electricity into an almost unfair advantage?

The answer was sitting in plain sight: aluminum.

III. The Great Pivot: The Aluminum Arbitrage (2001-2010)

Aluminum has a dirty secret that most investors miss: it’s not really a metals business. It’s an electricity business wearing a hard hat.

The standard smelting method, the Hall-Héroult process, devours power—roughly 13,000 to 16,000 kilowatt-hours for every tonne of aluminum. That’s more electricity than many households use in an entire year, concentrated into one unit of output. Which is why, for most of modern industrial history, aluminum production followed cheap power the way shipping followed coastlines: Quebec, Norway, Iceland, the Pacific Northwest. Wherever hydro was abundant, aluminum showed up.

That’s also why China’s early, coal-heavy aluminum buildout was long viewed as economically fragile. Grid electricity was expensive and unreliable, and the incumbents were state-owned giants like Aluminum Corporation of China, Chalco—big, politically connected, and structurally burdened by the same state pricing system everyone else had to live with.

Zhang Shiping wasn’t living with it anymore.

He already had the one input that mattered most, on terms nobody else could touch: stable, cheap, captive electricity. And once you have that, aluminum stops looking like heavy industry and starts looking like arbitrage.

Hongqiao began its shift into aluminum in 2001 and then did what it always did: move fast, but in a way that compounds. By 2007, annual capacity had climbed to around 300,000 tonnes. The ramp wasn’t reckless; it was paired, step for step, with more power generation. Zhang learned early that you don’t “add” smelting like you add textile machines. Every new potline is basically a long-term power contract you sign with yourself. If generation and smelting didn’t grow together, the whole machine would wobble.

Out in Binzhou, the Weiqiao Model reached its full expression. This wasn’t a company with a smelter. It was a closed-loop industrial organism: coal comes in by rail and goes straight into on-site power plants. Electricity runs over private lines into smelters next door—no grid fees, no transmission tolls, no middlemen. Then the aluminum doesn’t even have to cool down. Molten metal can be sent directly to nearby fabrication facilities inside the same complex. The distances that usually get measured in provinces get measured in meters.

That design shaved cost at every layer. Grid-connected competitors carried transmission and distribution charges, plus all the embedded fees and cross-subsidies in state electricity pricing. Hongqiao avoided most of it. Its electricity cost was estimated at around RMB 0.30 per kilowatt-hour, versus roughly RMB 0.45 to 0.55 for producers buying from the State Grid.

In a commodity business, that gap isn’t incremental—it’s fatal. Analysts estimated Hongqiao’s comprehensive aluminum costs ran about RMB 1,500 to 1,600 per tonne below the China average. When aluminum prices rose, Hongqiao printed money. When prices fell, marginal producers bled out first. And because Hongqiao was private and founder-controlled—no state employment mandates, no bureaucratic drag—it could expand when everyone else was retreating.

That instinct mattered most in the 2008 Global Financial Crisis. While the rest of the world froze, Hongqiao leaned in. Zhang bet that Beijing would respond the way it always does in a downturn: build. And building—roads, rail, grid, housing—means metal, and metal means aluminum.

China’s massive stimulus package did exactly what Zhang expected. Aluminum demand surged through 2009 and 2010, prices rebounded, and Hongqiao’s new capacity hit the market at the perfect moment. Competitors who had paused investment during the panic watched a faster, cheaper player take share in real time.

The growth didn’t stop. After listing in 2011, Hongqiao expanded from about 1.1 million tonnes of capacity to 5.2 million tonnes.

But scale cuts both ways. The bigger Hongqiao got, the harder it became to ignore. Inside the industry, the Weiqiao Model was admired as ruthless vertical integration. Inside government, it triggered a different reaction: how was a private company operating power plants at this scale? Were permits in order? Were these expansions happening inside the lines—or in the gray space between them?

Those questions would eventually explode into a full confrontation over “illegal capacity.” But before the state forced a reckoning, Hongqiao ran into another threat—one that couldn’t be solved with a power plant or a faster construction schedule.

To keep smelting, they needed the rock. And the rock was about to get a lot harder to find.

IV. The African Gambit: Securing the Rock (2011-2015)

Cheap power made Hongqiao dangerous. But power alone doesn’t smelt aluminum. You still need the rock.

Every ton of aluminum starts as bauxite: a reddish ore that gets refined into alumina, and only then smelted into metal. Without a steady stream of bauxite, even the most efficient smelter becomes a very expensive collection of idle equipment.

For Hongqiao’s first decade in aluminum, that stream came from Indonesia. The ore was high quality, the logistics were workable, and it sat close enough to China to feel dependable. For a while, it looked like a stable foundation.

Then, in January 2014, Indonesia pulled the foundation out.

For years, Indonesia had supplied the bulk of China’s imported bauxite—roughly three quarters of it—until the government enforced a ban on exporting raw mineral ore. Jakarta’s logic was straightforward: stop shipping dirt, force the industry to process bauxite at home, and keep more value inside Indonesia.

For Chinese aluminum producers that had built their supply chains around Indonesian ore, it was a crisis. Indonesian bauxite production collapsed, and export revenue fell off a cliff from 2013 to 2014. Suddenly everyone was chasing alternatives, bidding up supply from places like Australia and India, and trying to patch together stopgap shipments in a chaotic spot market. Some companies swallowed the higher costs and watched margins compress. Others started making plans to build alumina refineries in Indonesia—slow, capital-heavy plans that still left them exposed to policy risk.

Zhang Shiping went looking for a different kind of answer. He went to Guinea.

Guinea is a small West African country wedged between Senegal and Sierra Leone, and it sits on an almost absurd endowment: around one-quarter of the world’s bauxite reserves, the largest known deposits on Earth. The ore is high quality. Much of it can be mined from the surface. And it isn’t far from the coast.

So why wasn’t Guinea already the center of the bauxite world? Because geology is only the first hurdle. Guinea came with the full set of reasons global investors stay away: political instability, weak infrastructure, corruption risk, and the sheer complexity of building mining and export logistics from scratch.

To most companies, those were deal-killers. To Zhang, they were an opening—if you could move faster than everyone else, and build something that didn’t require waiting a decade for “perfect” infrastructure.

The Guinea project kicked off in 2014, in an area that was non-cadastral and unexplored. SMB’s geologists identified bauxite reserves less than 30 kilometers from the northern shore of the Rio Nuñez—close enough to hint at a workable evacuation route. The timeline that followed was almost comical by mining standards: SMB obtained its research permit on January 19, 2015, ran its Environmental and Social Impact Studies for six months, presented a feasibility study in June, secured its export license on July 7, and on July 20, 2015, the first tonne of bauxite left the Katougouma river terminal.

From first permits to first export in roughly eighteen months. In a frontier jurisdiction. At scale. That speed didn’t happen by accident—it came from the structure Zhang helped put together.

The engine was the SMB-Winning Consortium: Winning International Group, Yantai Port Group, China Hongqiao Group (via a Shandong Weiqiao subsidiary), and UMS Group’s Guinean operation. Each partner filled a specific gap. Winning, a Singapore-based shipping player, brought the vessels that could haul ore across roughly 11,400 sea miles to China. UMS, a French-Guinean logistics firm, brought operational muscle on the ground. Yantai Port provided the receiving infrastructure in Shandong. And Hongqiao brought what mattered most in commodities: the capital, the guaranteed demand, and the end destination for the ore.

But the real innovation wasn’t the shareholder list. It was the logistics hack that made Guinea exportable immediately.

Guinea didn’t have deep-water ports capable of loading the giant bulk carriers that make intercontinental ore transport economical. Building a new port would take years and enormous investment. The consortium didn’t wait. Instead, it built river terminals on the Rio Nuñez—at Katougouma and Dapilon—moved ore by truck along dedicated mining roads to those terminals, loaded it onto 8,000-ton barges, and floated it downstream to meet ocean-going ships at sea.

It wasn’t the most elegant system. It was the fastest. A good-enough solution that got bauxite moving while everyone else was still drawing port blueprints.

The results rewired the market. SMB-Winning became Guinea’s largest bauxite developer, and Guinea surged into the top tier of global exporters in a shockingly short time. Between 2012 and 2016, Guinea’s bauxite production jumped from 17.8 million tonnes to 30.8 million tonnes. Even when Indonesia relaxed its ban in January 2017, the world had already adjusted. Indonesia’s role in the bauxite trade had permanently shifted.

By 2023, Guinea had scaled to a new extreme, producing nearly 123 million tonnes of bauxite and ranking as the world’s largest producer—an outcome significantly driven by SMB-Winning, now the country’s leading producer and exporter.

And the consortium kept building. A 125-kilometer railway was planned to connect the Santou II and Houda deposits to the river port at Dapilon, crossing the Boké and Boffa regions and including 21 bridges, two tunnels, and six deposits—the first railway built in Guinea since the 1970s.

The ambition didn’t stop with bauxite either. In 2019, a consortium involving Société Minière de Boké and Winning Shipping (SMB-Winning) offered $14 billion to win a tender to develop part of Guinea’s Simandou iron ore project, beating out Australia’s Fortescue Metals Group. The group committed to developing blocks one and two of the deposit, which holds more than two billion tonnes of high-grade iron ore.

For Hongqiao, this was the vertical integration story reaching across an ocean. Guinea bauxite fed alumina refineries in China and Indonesia. Captive power fed the smelters. Smelting fed fabrication. Each link reduced dependency. Each link lowered costs. And each link made it harder for competitors—especially slower, more bureaucratic incumbents—to keep up.

Bauxite from SMB-Winning flowed into Yantai Port in Shandong, where it could be processed and ultimately turned into aluminum by Hongqiao’s subsidiaries. That aluminum then moved into China’s industrial supply chains—ending up in everything from car parts to global brands, including Audi, BMW, and Ford.

V. The Short Report & The State Strikes Back (2016-2018)

By 2016 and 2017, Hongqiao had become too large, too visible, and too profitable to stay in the shadows. The same things that made the Weiqiao Model unbeatable—unusually cheap power, relentless expansion, and a comfort with regulatory gray zones—also made it an obvious target. And then the hits started coming from two directions at once: the markets, and Beijing.

The financial attack landed first.

Emerson Analytics, a short seller, went public with a blunt argument: Hongqiao’s margins were “impossible” for a commodity producer, so the numbers must be wrong. Hongqiao’s shares slid hard on the headlines. After the company issued a statement rejecting the accusations, the stock still slumped as much as 6.9%. When Emerson published a report in February 2017—reiterating earlier claims and adding allegations that losses were being kept off the balance sheet through undisclosed related parties—the pressure intensified.

In March, Hongqiao disclosed that its auditor, Ernst & Young, needed more time to complete the audit. That’s the kind of sentence that can turn skepticism into panic. Markets don’t like uncertainty, and they like “audit delay” even less.

Emerson’s report claimed Hongqiao had hidden 21.6 billion yuan in costs by underreporting over the years, and argued profitability was less than half of what the company reported. It also alleged Hongqiao had under-reported the cost of self-generated power and alumina, and pegged the “true” value of the stock at HK$3.1—about 60% below where it traded at the time. On March 1, when the report hit, the share price dropped nearly 10%.

But here’s the part industry insiders found almost darkly funny: the short thesis treated Hongqiao’s margins as proof of fraud, when the margins were the whole point of the story. The company really did have a power cost structure other producers couldn’t match. It really did avoid many of the tolls and fees embedded in State Grid pricing. The advantage looked unreal because it was unusual—not because it was made up.

Still, “unusual but real” isn’t a defense that stabilizes a stock in the middle of a credibility crisis. Trading in Hongqiao shares was suspended. The company’s reputation—built over decades on execution and scale—was suddenly being litigated in public.

Hongqiao ultimately fought back with paperwork and process. It published a detailed rebuttal in October, released its financials, and resumed trading. After a fourth Emerson report later that month, Hongqiao went a step further and secured an injunction against the short seller from a Hong Kong court. The allegations remained unproven.

When trading finally resumed, it was a reminder of how much fear had been priced in. After seven months halted, the stock jumped—up more than 40% at one point—and closed at HK$9.3, up 31.92% on the day.

But while Hong Kong investors were arguing about accounting, Beijing was preparing something far more concrete: shutdown orders.

China had launched a sweeping campaign against pollution and industrial overcapacity. The targets were the usual suspects—steel, coal, aluminum—especially operations that had expanded without proper permits or environmental approvals. And Hongqiao, by design, had expanded fast.

In August and September 2017, China’s central government Environmental Protection Inspection Group 3 spent a month in Shandong Province reviewing environmental protection work. In its final report, the group found that Shandong Weiqiao Group had illegally built 45 coal power units in Shandong.

Then came the blow that mattered most to operations: in 2017, officials ordered the closure of two million tonnes of unapproved smelting lines as part of the nationwide push against illegal capacity.

That wasn’t a slap on the wrist. Two million tonnes amounted to roughly 30–40% of Hongqiao’s operating capacity. This wasn’t “fix it and file a report.” This was: turn off potlines that had been running for years.

For most companies, that would have been catastrophic. For Hongqiao, it triggered a different kind of resolution—one that only works in a system where the state can punish you and save you in the same breath.

Hongqiao was too economically central to simply be allowed to fail: too many jobs, too much tax revenue, too many downstream manufacturers dependent on its metal. But it was also too blatant in its permit situation to be waved through untouched. So the outcome was a forced reset, with a state backstop.

Hongqiao struck a $1 billion equity financing agreement with CITIC Group Corp. This wasn’t just capital; it was a signal. CITIC is a massive state-owned conglomerate with deep government ties. Its involvement effectively told the market: Hongqiao may have crossed lines, but it isn’t going to be allowed to collapse. There would be consequences—shutdowns, compliance, scrutiny—but not a wipeout.

The ownership picture today captures that new balance. The Zhang family, through Hongqiao Holdings, remains the controlling shareholder, holding about 64.27% as of June 17, 2024. CITIC is the second-largest shareholder, at around 12.0%. Founder control stayed intact, but now with an unmistakable state presence in the cap table.

Compliance followed. In May 2018, the Shandong Provincial government responded to the inspection report with a cleanup plan. According to the province, 33 of Weiqiao’s 45 illegal coal power plants had completed the necessary procedures to receive environmental clearance and continue operating. The remaining 12 did not complete procedures and were supposed to stop construction and operations immediately.

That was the new deal: keep the machine running, but inside the lines.

The crisis forced a recalibration in Hongqiao’s relationship with the state. The company could no longer behave like speed was its only strategy. Yet the outcome also validated the underlying model. The plants that stayed online—now properly permitted—still produced the cheap power that made Hongqiao’s aluminum competitive. The vertical integration remained. Guinea bauxite still flowed through Yantai and into the system.

What changed was the trajectory. The era of building first and legalizing later was ending. From here on out, expansion had to match policy. And China’s industrial policy was converging on one word that would define the next chapter for Hongqiao: decarbonization.

VI. The Great Migration: Trekking to Yunnan (2019-Present)

May 23, 2019 marked the end of an era. Zhang Shiping died of an unspecified illness, according to an official announcement from his hometown of Zouping County in Shandong. The man who had turned towels and denim into an aluminum empire powered by coal would not be the one to steer it through the next transformation.

That job fell to his son, Zhang Bo. By the time his father passed, Zhang Bo had already been CEO since January 2011. After being elected chairman, he kept the operating reins in his hands. The handoff was orderly. The world around the business was not.

China was tightening the frame around every heavy industrial company with a new national mandate: the “Dual Carbon” goals—peak emissions by 2030, carbon neutrality by 2060. For Hongqiao, whose edge had been built on captive, coal-fired electricity, this wasn’t a new compliance checklist. It was the possibility that the very engine of the Weiqiao Model would become politically—and economically—untenable.

So Hongqiao responded in the most Hongqiao way possible: not with tweaks, but with a relocation.

If coal-fired power was turning from an advantage into a liability, then the smelters would move to where the electrons were clean.

In Wenshan Autonomous Prefecture in Yunnan Province, the local government and Shandong Weiqiao Pioneering Group began work on a green aluminum industrial park. The plan was massive: a 40 billion yuan investment that had already attracted nine enterprises across the aluminum value chain. When fully operational, annual sales and industrial output were expected to reach 100 billion yuan and 30 billion yuan. More importantly, this project signaled the start of Hongqiao’s two-phase relocation of about 30% of its smelting capacity—2.03 million tonnes per year—from Binzhou in Shandong to hydropower-rich Yunnan, along the border with Vietnam.

Yunnan is built for this. It’s mountainous, river-cut, and loaded with hydropower potential. Snowmelt-fed systems cascade through valleys, turning geography into electricity. For aluminum—“congealed electricity”—that kind of power supply changes the entire narrative. Hongqiao aimed to keep primary aluminum output at around six million tonnes per year while shifting capacity from coal to hydro. The broader plan was even larger: relocating a total of four million tonnes of aluminum capacity from Shandong to Yunnan, with one million tonnes already in operation.

On sheer scale, it was almost without precedent. Hongqiao’s move from Shandong to Yunnan was set to be the biggest relocation of aluminum capacity in the world. The company expected that moving away from fossil-fueled electricity would address roughly three-quarters of its carbon footprint.

And it wasn’t just about optics. The economics worked.

Management expected profitability at the Yunnan base to exceed Shandong’s thanks to hydropower tariffs. On full operation, unit production cost in Yunnan was estimated to be 10% to 14% lower. In other words: lower emissions, lower costs, and a shot at becoming one of China’s two largest “green aluminum” producers.

But swapping coal for water introduced a new kind of fragility. Hydropower is clean, but it’s seasonal—and it’s vulnerable to drought. In May 2021, water shortages squeezed electricity supply and forced around a quarter of Yunnan’s aluminum plants to shut for months. A similar crunch hit in September 2022, when the provincial government ordered smelters to cut electricity use by 15% to 30%. Power curbs returned again as rainfall came in lower than expected; in September, primary aluminum producers were told to reduce usage by at least 10%, and one major local producer said curbs expanded to 20% from October.

Hongqiao’s argument was that these were short-term disruptions inside a long-term shift. Yunnan was adding wind and solar alongside hydro, aiming for a more resilient renewable system. Hongqiao said it would keep pushing its “Green Transitioning” capacity relocation—moving electrolytic aluminum production to Yunnan while expanding investment into wind and photovoltaics. In its framing, this wasn’t a simple move from Point A to Point B. It was an overhaul of the company’s energy structure, gradually tilting from fossil fuels to renewables across both Shandong and Yunnan.

The payoff wasn’t only cost. It was market access.

As global automakers and consumer electronics brands faced rising pressure to decarbonize their supply chains, low-carbon aluminum began to trade less like a pure commodity and more like a credentialed input. Buyers wanted proof—documented emissions profiles, verified sourcing, audit trails. Apple, BMW, and Tesla all sought suppliers that could meet those standards. Hydropower-based aluminum gave Hongqiao a product it could sell into those high-value chains with a different story attached.

China Hongqiao supplies aluminum to 90% of the world’s Apple mobile phone back covers.

Policy abroad added another tailwind. The EU’s Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism, scheduled to take full effect by 2027, is designed to penalize carbon-intensive imports. For coal-based aluminum, that’s a direct hit to competitiveness in Europe. For lower-carbon production, it’s insulation—and potentially an advantage as European automakers electrify and scrutinize embedded emissions more aggressively.

Hongqiao expected its production cost edge to strengthen as the Yunnan shift raised the proportion of green electricity, supported by its integrated supply chain. The company targeted completing the relocation of roughly 2.2 million tonnes of capacity to Yunnan by FY25, representing about 34% of total capacity.

Financial performance suggested the machine was working. For the year ended December 31, 2024, revenue rose 16.9% to about RMB 156.17 billion. Net profit attributable to owners jumped 95.2% to about RMB 22.37 billion, helped by efficient operations and strong demand. For the six months ended June 30, 2025, revenue reached RMB 81,039,092 thousand, up 10.1% year over year. Gross profit increased 16.9% to RMB 20,805,191 thousand, and net profit attributable to shareholders rose about 35.0% to RMB 12,361,046 thousand.

As the operational story shifted, so did the governance story. Zhang Bo, having been CEO since 2011, became both chairman and CEO in 2019 after his father’s death. In parallel, Hongqiao moved from the “Wild West” era—where speed and regulatory gray zones were features, not bugs—into a “Modern Corporate” era defined by sustainability credentials, compliance, and ESG reporting.

In 2021, Hongqiao joined the Aluminum Stewardship Initiative. In 2022, it gained ASI Performance Standard certification for several downstream plants. The same company that once built an off-grid empire in the cracks of the system was now actively seeking international validation from sustainability bodies.

And then came the most symbolic shift of all: by 2025, Hongqiao’s private power grid was slated for full integration into the national State Grid system. That integration could bring stability—but it also threatened to erode the original cost advantage that built the empire, potentially squeezing margins in the core business.

For Hongqiao, this was the final normalization of its relationship with regulators. The arbitrage that had powered the first rise—cutting the cord to the State Grid—was being unwound. The open question is whether the company’s newer advantages—hydropower access in Yunnan, the Guinea bauxite chain, deep vertical integration, and a credible green aluminum position—can sustain the kind of margins that the island grid once made almost automatic.

VII. Strategic Analysis: Competitive Moats and Industry Dynamics

Step back and Hongqiao starts to look less like a traditional metals company and more like a system: power, ore, logistics, smelting, fabrication—all stitched together tightly enough that the seams disappear.

To explain why that system has been so hard to compete with, two frameworks help. Hamilton Helmer’s 7 Powers tells you where enduring advantages come from. Michael Porter’s 5 Forces tells you what the industry is trying to do to you. Put them together and you get a pretty clear picture of what Hongqiao built, what it’s building now, and where the pressure points are.

Process Power: The Foundation

Hongqiao’s most durable edge fits Helmer’s idea of Process Power: a cost advantage created by a production system that’s been tuned over time—less a single invention than a thousand accumulated decisions that compound.

That’s the Weiqiao Model at full volume. Captive power generation feeding smelters next door. An industrial layout in Binzhou designed so molten aluminum can move straight from potline to fabrication without the cost, time, and energy of cooling, transporting, and remelting. And upstream of all of it, a Guinea-to-Shandong logistics chain that turns an infrastructure-poor West African coastline into a reliable raw-material pipeline.

None of this is impossible to understand from the outside. It’s just brutally hard to replicate. The “secret” isn’t a patent—it’s the way the whole machine fits together. The know-how is spread across people, routines, supplier relationships, plant layout, and the physical assets themselves. That’s why Process Power tends to be sticky: you can copy the idea, but copying the lived experience takes years.

Cornered Resource: Bauxite Access

The Guinea operation is another Helmer category: a Cornered Resource. Not in the sense that Hongqiao owns all bauxite, but that it has preferential access to a particularly valuable supply stream—and built the infrastructure to move it.

Through the SMB-Winning Consortium, Hongqiao positioned itself around some of the world’s highest-quality reserves. Mines, dedicated roads and rail plans, river terminals, barges, ocean freight, and a receiving port setup in Shandong together create a barrier that isn’t just financial—it’s practical. The sunk cost is huge, and the operational complexity is non-trivial.

Hongqiao is also the world’s largest single bauxite importer, with annual inputs above 40 million tonnes. In Guinea, it set up a joint-venture mining company and a river port company focused primarily on bauxite mining. For competitors, matching that position usually means one of two painful paths: spend years negotiating new concessions and building infrastructure, or buy from more expensive sources like Australia and live with structurally higher costs.

Scale Economies: Size Matters

Then there’s the simplest advantage, and often the most underestimated: sheer scale.

With aluminum production capacity of about 6.46 million tonnes—roughly 18% of China’s total capacity—Hongqiao spreads fixed costs across an enormous base: Guinea infrastructure, corporate overhead, compliance systems, process improvements. Scale also shows up in leverage: with suppliers, with customers, and with local governments that care deeply about employment and tax base.

Scale brings resilience, too. In downturns, marginal producers get squeezed out first. A player with the lowest costs and the biggest footprint can survive the cycle—and often comes out the other side stronger.

Porter’s Five Forces Assessment

Supplier Power: Low. Hongqiao blunts supplier power through vertical integration. It generates much of its own electricity, secures bauxite through its Guinea position, and refines alumina. The main remaining external inputs—coal and labor—are broadly available and not controlled by a single chokepoint supplier.

Buyer Power: Mixed. Aluminum is a commodity, and in commodity markets buyers usually have the upper hand because switching is easy. But Hongqiao has been trying to carve out a partial escape hatch with lower-carbon, hydropower-based aluminum. For automakers and electronics manufacturers that need to decarbonize their supply chains, the list of credible, scalable sources is shorter—so buyer power weakens in that “green” segment.

Threat of Substitutes: Low. In most of its core uses, aluminum is hard to replace: lightweight, strong, corrosion-resistant, and highly recyclable. It’s deeply embedded in autos, aircraft, construction, and packaging. Electric vehicles strengthen the case further; you can’t simply swap away from aluminum without penalties elsewhere.

Threat of New Entry: Moderate. Aluminum is one of the least forgiving industries to enter. You need enormous capital, low-cost power, and secure raw materials. Those are high walls. Still, China’s state-owned players—especially Chalco—have the resources to expand or reallocate production. And while policy has capped new domestic capacity, incumbents can still reshuffle where and how they produce.

Competitive Rivalry: Intense. Hongqiao’s main domestic rival is Chalco, a state-backed heavyweight that often leads on volume. Rivalry is real, but it’s also shaped by policy—capacity controls and environmental enforcement change the contours of competition. Globally, the roster includes Rusal, Alcoa, and Norsk Hydro, all competing in international markets where cost, carbon intensity, and access to customers matter.

The Bull Case: Energy Transition Tailwinds

The strongest demand tailwind is the electrification of transport. As automakers move to new EV platforms, weight becomes even more valuable: batteries are heavy, and range is precious. Aluminum is one of the cleanest ways to claw back efficiency without sacrificing strength.

Industry forecasts point to meaningful increases in aluminum content per vehicle through 2030. BEVs, in particular, tend to use substantially more aluminum than non-BEVs, especially for structural parts. That mix shift matters because it’s not just “more cars.” It’s “more aluminum per car.”

There’s also a second-order effect: decarbonization is turning aluminum from a pure commodity into a partially differentiated input. If you can supply low-carbon metal at scale, you can win access to premium supply chains and, in some cases, better pricing.

That’s where Hongqiao’s Yunnan migration fits. Hydropower-based production positions the company to meet demand growth while aligning with customer emissions targets. And because Hongqiao is already enormous, it can offer what many buyers actually need: reliable volumes, not just a green story.

The Bear Case: Structural Risks

The risks are real, and they map directly to the same system-level dependencies that make Hongqiao powerful.

Real Estate Exposure: Construction has historically absorbed a large share of China’s aluminum demand. A prolonged property-sector downturn reduces that baseline. EV growth and exports can offset some of it, but if construction stays weak for years, total demand could still come under pressure.

Yunnan Hydropower Volatility: Hydropower is cleaner and often cheaper, but it’s not constant. Drought-driven power curbs—like the cuts seen in 2022—can force production reductions. A severe multi-year drought would be more than a nuisance; it could become a structural constraint on the very “green” capacity Hongqiao is betting on.

Geopolitical Risk in Guinea: Guinea’s 2021 military coup was a reminder that resource security isn’t just geology and logistics; it’s politics. Operations have continued under the new government, but future instability could still threaten supply or change the economics of export.

Grid Integration Impact: As Hongqiao’s private grid integrates into the State Grid, the company risks losing a historic cost advantage that once looked almost unfair. The burden shifts to proving that Yunnan hydropower, vertical integration, and operational efficiency can keep margins strong without the original island-grid edge.

VIII. Playbook: Lessons for Builders

Hongqiao isn’t a Silicon Valley story. It’s a heavy-industry one. But the playbook travels surprisingly well—especially if you build in markets where inputs are expensive, regulation is evolving, and execution speed matters more than elegance.

Regulatory Arbitrage as Strategy

Hongqiao didn’t win by out-inventing the incumbents. It won by outrunning the rulebook.

The company found a gray zone in China’s energy regulations: if you were generating electricity for “co-generation” needs, you could build power capacity for your own operations. Zhang Shiping pushed that opening to its limit, used it to cut power costs dramatically, and built an advantage that showed up directly in smelting economics.

And then came the real test of the strategy: what happens when regulators notice. Hongqiao’s answer was essentially, “by then, we’ll be too embedded to unwind.” The 2017 crackdown proved the risk is real—Beijing can, and will, force a reset. But it also proved the underlying logic: in fast-changing systems, the rules often catch up after the winners have already been decided.

Speed Over Perfection: The "Good Enough" Solution

The Guinea operation is the clearest example of Hongqiao’s bias toward action.

Traditional mining logic said Guinea couldn’t become a major exporter without deep-water ports. That kind of infrastructure takes years and massive capital. SMB-Winning didn’t wait. It built river terminals, moved ore by road, loaded barges, and transferred cargo offshore to ocean-going vessels.

It wasn’t pretty. It wasn’t “optimal.” It was working—and it was working years earlier than the “proper” solution would have. In commodities, that timing edge isn’t a nice-to-have. It’s the difference between securing the best concessions and arriving when the land grab is already over.

Vertical Integration in Hard Tech

Hongqiao’s system runs on a blunt rule: if you can’t control your inputs, you don’t control your business.

Bauxite, power, logistics, smelting, fabrication—Hongqiao worked to own or tightly lock down each link. That integration softened the two shocks that have killed plenty of peers: raw material disruptions and energy cost spikes. When Indonesia banned bauxite exports, Hongqiao had another path. When electricity prices and policy tightened, it had its own generation base and, eventually, a route to hydropower.

Vertical integration like this is expensive and complicated. But in cyclical, low-margin industries, it’s often the closest thing to a real moat.

Founder-Led vs. Manager-Led Organizations

Finally, there’s the human advantage that sits underneath the whole machine: founder control.

Zhang Shiping made calls that would be career-ending for a professional manager inside an SOE: building power capacity in regulatory gray zones, expanding aggressively when others froze, committing massive resources to Guinea before the infrastructure existed. Those bets weren’t just strategic—they were personal. They required patience, appetite for ambiguity, and a willingness to look wrong for a long time before being proven right.

That’s the founder-led edge in its purest form: risk tolerance plus time horizon. In Hongqiao’s case, it didn’t just create upside. It created the company.

IX. Forward Outlook: Bears, Bulls, and Key Metrics

Hongqiao’s story has never been about a single bet. It’s been about stacking advantages—power, ore, logistics, and policy timing—and then staying ahead of whatever the next constraint is. From here, the question is simpler: do the forces that made the company win for twenty years keep working in a world that’s tightening on carbon, tightening on permits, and increasingly dependent on hydropower?

Bear Case Scenarios

Property Sector Collapse: If China’s real estate downturn deepens and drags the broader economy with it, aluminum demand could slip below what’s needed to support today’s pricing. For a business with heavy fixed costs, that’s how margins get squeezed fast.

Climate/Hydro Risk: Yunnan is the centerpiece of the green transition, but it’s also exposed. A multi-year drought could force sustained curtailments, turning “cheap hydro” into “not enough power.” And there isn’t a clean, off-the-shelf hedge for that.

African Geopolitics: Guinea is a pillar of Hongqiao’s raw-material security. More political instability could disrupt bauxite flows—or force renegotiations that change the economics in Hongqiao’s disfavor.

Bull Case Scenarios

EV Revolution Acceleration: If EV adoption surprises to the upside, aluminum demand grows with it. That’s the scenario where Hongqiao’s low-carbon supply becomes more than a nice story—it becomes a ticket into the highest-value customers, at scale.

Capacity Discipline: If China sticks to its roughly 45 million tonne capacity cap while demand keeps rising, the market tightens. In commodities, disciplined supply is a gift, and it can keep pricing healthier for longer than skeptics expect.

Carbon Pricing Expansion: If carbon border adjustment mechanisms spread, the penalty shifts onto the highest-emissions producers. That would widen the gap between “coal aluminum” and “green aluminum,” and make Hongqiao’s Yunnan migration look less like ESG and more like strategy.

Key Performance Indicators to Track

If you want to track whether Hongqiao’s edge is strengthening or fading, two numbers tell you most of what you need to know:

1. All-in Electricity Cost per Tonne of Aluminum

This is the core of the whole business. As Hongqiao shifts from coal to hydro, and as its private grid integrates into the State Grid, power costs will decide whether the model still prints money—or just keeps up. The best clue tends to show up in the company’s periodic presentations to analysts.

2. Proportion of Revenue from Green/Low-Carbon Aluminum

This is the scoreboard for the transition. A rising share means Hongqiao is successfully moving from pure commodity competition to a more credentialed product that can win EV and export supply chains where carbon content is becoming a purchasing requirement, not a preference.

X. Final Reflection

There’s a deep irony baked into China Hongqiao’s rise. The company that built its edge in Shandong by burning vast amounts of coal now wants to be known as a champion of green aluminum. The family that made its name by cutting the cord to the State Grid and operating in regulatory gray space now seeks credibility through international sustainability certifications.

But this shift isn’t a gimmick, and it isn’t an accident. It’s the same instinct the Zhang family has always had: read the direction of policy and markets, then get out in front of it. In the 1990s and 2000s, that meant riding China’s sprint toward industrial capacity, in a period when environmental costs were easier to ignore. In the 2020s, it means surviving—and ideally winning—in a world where carbon intensity is becoming as important as cost.

By 2024, the Shandong-based group reported revenue of about 156.2 billion yuan. That number is big. The arc behind it is bigger: a cotton ginning plant in rural Zouping turning into a global aluminum system that stretches from Guinean mines to Chinese smelters, and into the supply chains of the modern world.

None of what comes next is guaranteed. This is still a commodity business, and commodities are cyclical by nature. Yunnan’s hydropower advantage can be undermined by drought and climate volatility. Guinea’s politics can shift faster than any logistics plan. And folding Hongqiao’s private grid into the State Grid threatens to dull the original edge that powered its first ascent.

Still, Zhang Shiping’s core insight remains the cleanest way to understand the whole story: in aluminum, you’re not really making metal. You’re making congealed electricity. Control the cost and reliability of power—and you control your destiny.

Now the definition of “cheap” power is changing. Coal won the last era. Renewables are defining the next. Whether Zhang Bo and the team can navigate that transition with the same speed and clarity that built Hongqiao in the first place will decide what this company becomes: a durable industrial champion, or a case study in what happens when an empire built on one energy regime fails to adapt to the next.

The story continues.

Chat with

this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with

this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music