CK Asset Holdings: The Story of Asia's Most Strategic Real Estate Empire

I. Introduction: From Plastic Flowers to 2,700 British Pubs

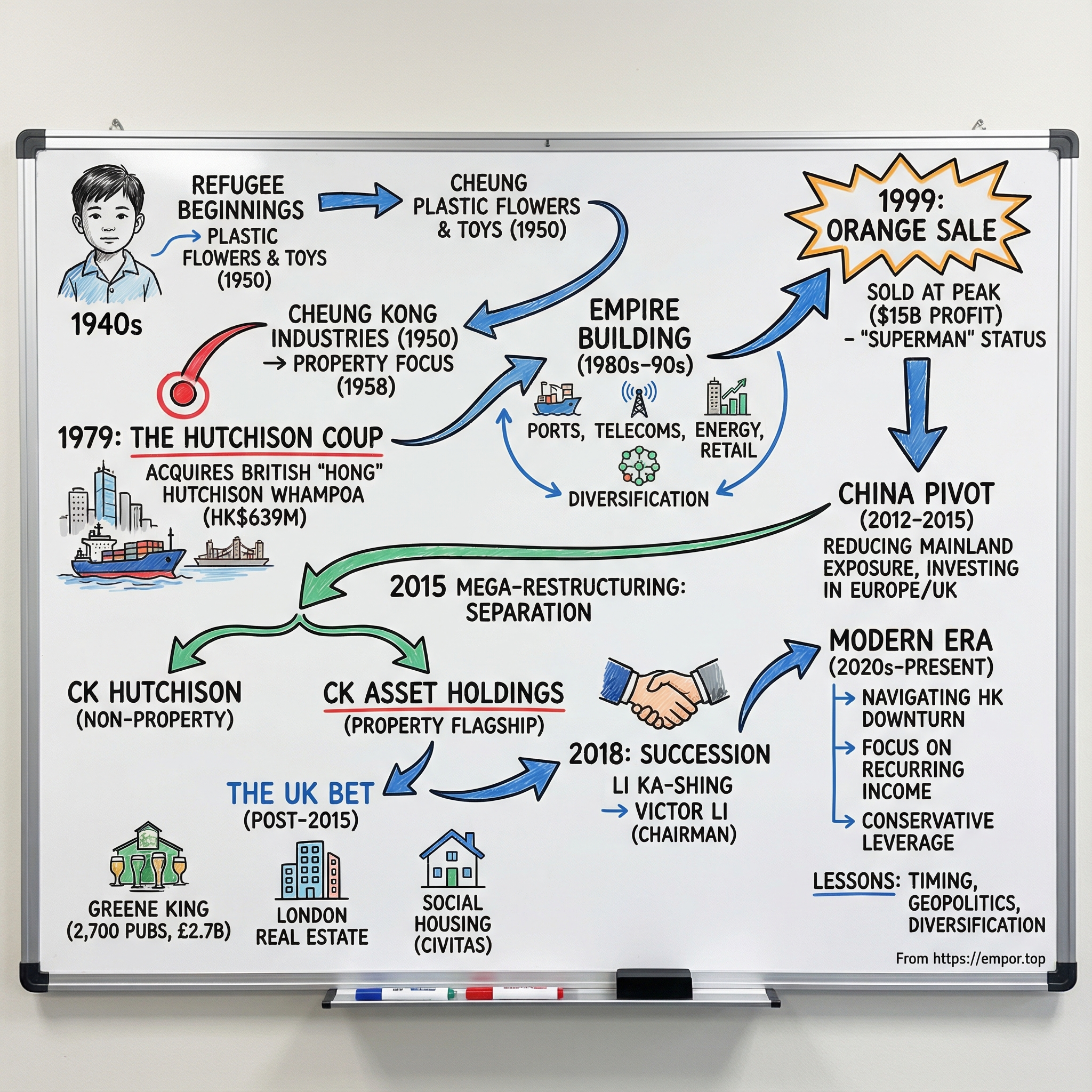

Picture this: a 12-year-old boy fleeing a China at war in 1940. School is over, childhood is over, and in a cramped Hong Kong tenement he watches his father waste away from tuberculosis. Within a few years, he’s working punishing hours—selling plastic watchbands door-to-door, grinding through 16-hour days—because his family needs food more than he needs sleep.

Now jump to December 2025. That same boy has become the architect of an empire that reaches across more than fifty countries. It owns and develops landmark towers that define Hong Kong’s skyline. It has poured money into property across Hong Kong, the Mainland, Singapore, the United Kingdom, continental Europe, Australia, and Canada—office, industrial, retail, residential, the whole mix. And, in one of the great “wait, what?” twists in modern capitalism, it also owns a British pub giant: roughly 2,700 pubs, restaurants, and hotels serving pints up and down the UK.

This is CK Asset Holdings—the property crown jewel of the broader Li Ka-shing universe. Officially, CK Asset Holdings Limited (formerly Cheung Kong Property Holdings Limited) is a property developer registered in the Cayman Islands, headquartered in Hong Kong, with its principal place of business there too. But “property developer” doesn’t really capture it. CK Asset is the long-duration ballast in a family-built conglomerate machine: part landlord, part builder, part investor—and, yes, operator of pubs, hotels, and serviced suites.

The question that drives the whole story is simple and huge: how did Li Ka-shing—a refugee who began in plastics, making cheap flowers and toys—build a business that helped shape Hong Kong itself and ended up owning thousands of British pubs? And the sequel matters just as much: after Li earned the nickname “Superman,” can his son, Victor Li, sustain the dealmaking and the discipline that made the empire?

Because this wasn’t built on one great bet. Li’s world sprawls across transportation, real estate, financial services, retail, energy, and utilities. At its height, Cheung Kong Holdings wasn’t just influential—it was a pillar of the Hong Kong market, representing about 4% of the aggregate market capitalisation of the Hong Kong Stock Exchange.

Three themes run through everything that follows: timing—buying when others can’t, selling when others won’t; geopolitics—playing the long game between China and the West; and succession—whether a once-in-a-generation operator can hand off more than just shares. The big turning points—the 1979 Hutchison coup, the China pivot, the 2015 mega-restructuring, and the UK diversification—aren’t just corporate milestones. They’re moments where reading the world correctly created, protected, or repositioned enormous value.

II. The Refugee's Rise: Li Ka-shing's Origin Story

The story starts far from Hong Kong’s gleaming towers—in Chiu Chow (Chaozhou), a coastal city in southeastern China, where Li Ka-shing was born on 29 July 1928.

His family lived modestly. His father was a teacher and a school headmaster, and in the Li household, education wasn’t just encouraged—it was sacred. Then history intervened. The Japanese invasion upended everything. In 1940, when Li was 12, the family fled to Hong Kong. School ended overnight. Survival became the curriculum.

Not long after arriving, tragedy compounded displacement. Li’s father fell ill with tuberculosis and died in Hong Kong. Before Li was 15, he was the one expected to keep the household afloat. He found work at a plastics trading company and endured 16-hour days—factory labor, then sales—doing whatever he could to bring money home.

And he was good. Not just “hard-working” good—exceptional. He rose quickly, becoming the factory’s top salesman, and by 18 he’d been promoted to factory manager. It’s a small detail that matters, because it hints at the pattern that defines his whole career: he didn’t just participate in systems, he learned them faster than everyone else—and then started shaping them.

By his early twenties, he’d saved enough to take the leap. In 1950, at age 22, he founded his own plastics manufacturing business, Cheung Kong Industries, opening his first factory with about US$6,500 cobbled together from savings and family loans.

Cheung Kong’s early growth came from a product that sounds almost comically humble: plastic flowers. Post-war Hong Kong was becoming a global export engine, and Li spotted demand in the U.S. for inexpensive artificial flowers. The factory produced a wide range of goods, and among its clients was Hasbro, which commissioned the company to make G.I. Joe dolls for export to the United States.

But the real tell in this chapter isn’t that Li could build a successful factory. It’s that he never mistook manufacturing for destiny. He believed Hong Kong’s enduring wealth would be built on land.

In 1958, when his landlord raised the rent, Li didn’t just negotiate—he bought the building. It was a turning point: the first time he used operating success to secure the underlying asset. From there, the direction of travel was clear. By the 1960s, Cheung Kong was increasingly becoming a property development and management business.

Even the name carried a worldview. Li believed deeply in synergy—the idea that combined efforts compound. He named the company “Cheung Kong,” after the Yangtze River, which gathers countless tributaries into one powerful flow. It was a metaphor for how he intended to build: through partnerships, joint ventures, and deals that aggregated into something far bigger than any single project.

What truly separated Li from other property developers wasn’t taste or bravado. It was risk discipline. His playbook was simple and unusually conservative: avoid over-relying on debt by raising capital before building. He did it by forming joint ventures with landowners and by preselling apartments to friends and colleagues. Cheung Kong could grow quickly while taking fewer existential risks—earning profits, keeping flexibility, and, crucially, staying in control.

That temperament—building a war chest, moving only when the odds were right, and never letting leverage dictate the timetable—became the signature of the Li empire for decades.

In 1971, the company was renamed Cheung Kong Holdings. A year later, in 1972, Li listed it on the Hong Kong Stock Exchange, marking his arrival as a serious force in the city’s business life. And by 1979, he wasn’t just a successful developer. He was Hong Kong’s largest private landlord.

Which is exactly when he made the move that would change not only his own trajectory, but the balance of power in Hong Kong’s economy.

III. Breaking the Colonial Ceiling: The 1979 Hutchison Whampoa Acquisition

To understand what Li Ka-shing pulled off in 1979, you first have to understand the world he was walking into.

For more than a century, Hong Kong’s economy had been run by British trading houses known as “hongs.” They weren’t just companies; they were institutions—Jardine Matheson, Swire, Hutchison—names that carried colonial gravity. British capital. British management. British networks. For a local Chinese businessman, no matter how wealthy, buying one of these firms wasn’t just difficult. It was almost unthinkable.

Hutchison was one of the most storied of them all. The pieces of what became Hutchison Whampoa went back to the 1800s: Hongkong and Whampoa Dock was founded in 1861, and Hutchison International began in 1880 as an importer and wholesaler of consumer products. Over time it expanded far beyond trading. By the 1960s and 1970s it was a sprawling conglomerate touching everything from property to infrastructure.

But sprawl can turn into bloat. By the mid-1970s, Hutchison was struggling badly enough that Hongkong & Shanghai Banking Corporation, HSBC, stepped in as a rescuer and ended up with a stake of more than 20%. The company tried to steady itself: it sold off dozens of subsidiaries, strengthened its finances, and in 1977 merged with Hongkong and Whampoa Dock to form Hutchison Whampoa Limited. In 1978 it listed on the Hong Kong stock exchange.

Then came the shock.

In 1979, Li quietly negotiated with HSBC to buy its roughly 22% stake—enough to take control. The price was HK$639 million, a figure that stunned the Hutchison board when they learned of it. It was widely seen as far below what it should have been—less than half of book value, according to the board. And Li didn’t just get a low price; he got friendly terms. HSBC accepted a 20% deposit, with the balance payable over two years. As Bill Wyllie, the managing director of Hutchison at the time, put it: for Li, it was a brilliant deal.

On 25 September 1979, at the close of trade in London, HSBC announced it was selling its stake in Hutchison Whampoa to Cheung Kong Holdings for HK$639 million. In that moment, Li became the first Chinese businessman to take control of one of the British-founded hongs that had dominated Hong Kong’s economy since 1841.

So why would HSBC do this—sell so cheaply, and finance so generously?

Part of the answer was practical. HSBC had rescued Hutchison and needed a long-term buyer, and it played a crucial role in the transaction by financing most of the purchase at low interest. Li also had a track record with the bank—his earlier cooperation with HSBC during the Wharf Holdings deal had helped build trust.

But there was also timing, and geopolitics. China, under Deng Xiaoping, had begun showing early signs of opening up. In that environment, Li’s relationships and perceived access mattered. As one account put it, his “special contacts in China” played prominently in the bank’s decision. Li would later serve as a senior adviser to Beijing on the 1997 Hong Kong handover, reinforcing the idea that he was a uniquely positioned bridge between systems.

And once Li had Hutchison, it didn’t stay a wounded colonial relic for long. Under Cheung Kong’s control, Hutchison Whampoa grew into a platform spanning ports, property, retailing, telecommunications, infrastructure, and energy—an operating machine that reached far beyond Hong Kong.

This was Hong Kong’s crossing-the-Rubicon moment. Not because a deal got done, but because of what the deal signaled: the city’s center of gravity was shifting. The era when British heritage determined who could own the commanding heights of the economy was ending. The era when local Chinese entrepreneurs could take them—and build them bigger—had arrived.

IV. Empire Building: The 1980s-1990s Expansion

With Hutchison Whampoa as his platform, Li Ka-shing spent the next two decades turning what had been a Hong Kong property story into something far larger: a diversified conglomerate built to compound cash flows across cycles.

The shape of the expansion is easiest to see through the big building blocks. He had taken control of Hutchison Whampoa in 1979, and in 1985 the group acquired Hongkong Electric Holdings Limited (later renamed Power Assets Holdings Limited). Those weren’t just “more assets.” They were a shift in the business model—from making money primarily by developing and selling buildings, to owning the kinds of essential systems that throw off steady, recurring income.

Around the same time, the group pushed into telecoms. In 1985, Hutchison Telecommunications launched as a mobile phone service, and it grew into a major player in the 1990s. The logic was classic Li: bet on infrastructure. Not glamorous, but indispensable. Ports, power, and mobile networks are the plumbing of modern life—and if you own the plumbing, you get paid in every season.

Meanwhile, back on home turf, the property machine kept getting stronger. Cheung Kong and its chief rival, Sun Hung Kai Properties, steadily took more of Hong Kong’s new private housing supply. By 2010, the two would account for roughly 70% of the market, up from about half in 2003. A big driver was policy: the Hong Kong government auctioned land in expensive, large blocks—great for balance sheets with deep pockets, brutal for smaller and mid-sized developers. The result was an oligopoly, and Cheung Kong was one of the winners.

As the businesses sprawled, Li tightened his grip. By 2004, his equity in Hutchison Whampoa had risen to 49.9%. Over time, the dealmaker who had once seemed like an outsider to the old colonial establishment had become the central operator of one of Asia’s most consequential corporate networks.

By then, the myth had a nickname. In Hong Kong, Li was “Superman.” His empire spanned real estate, ports, telecommunications, finance and investments, energy, infrastructure, media, and even biotechnology. AsiaWeek went so far as to call him “the most powerful man in Asia” in 2000.

The structure mattered as much as the scope. Cheung Kong and Hutchison Whampoa were intertwined through cross-holdings: Cheung Kong Holdings owned 49.9% of Hutchison Whampoa, and Hutchison Whampoa owned 85% of Cheung Kong Infrastructure. With hundreds of thousands of employees worldwide, operations across dozens of countries, and listed vehicles that collectively represented a meaningful share of the Hong Kong stock market by the early 2000s, this was no longer a single company. It was an ecosystem.

And yet the man at the center of it cultivated almost the opposite image: famously frugal, almost stubbornly plain. He was known for simple black dress shoes and an inexpensive wristwatch—Citizen at times, later a Seiko, and later still he was spotted wearing an Apple Watch. He lived for decades in the same home in Deep Water Bay on Hong Kong Island, an area that became one of the city’s most expensive neighborhoods.

That contrast—massive operational reach paired with personal austerity—only deepened the legend. But the legend was about to get a new chapter. Because in 1999, Li executed a single transaction that would crystallize what made him different: not just building, not just buying, but knowing exactly when to sell.

V. The Orange Sale: The $15 Billion Masterstroke

If you want to understand why Li Ka-shing earned the nickname “Superman,” don’t start with skyscrapers. Start with a mobile phone company in the UK—and the decision to sell it at exactly the right moment.

In the early 1990s, Hutchison spotted an opening in Britain’s still-young mobile market. In July 1991, Hutchison Telecom—its UK subsidiary—bought a controlling stake in Microtel Communications Ltd, which held a licence to build a mobile network. Hutchison rebranded Microtel as Orange Personal Communications Services, and on 28 April 1994, Orange launched to the public.

It worked. Fast.

Orange was built from scratch into a real success story, and in April 1996 it went public, listing on both the London Stock Exchange and NASDAQ. Hutchison remained the majority owner with 48.22%, with BAe holding 21.1%. Within months, Orange became the youngest company ever to enter the FTSE 100, valued at £2.4 billion.

But the real lesson wasn’t that Hutchison could build a telecom operator. It was how it treated the business once it became valuable.

This was quintessential Li: get in early, build patiently, and don’t confuse a great asset with a forever asset. Hutchison had first tested UK telecom through an earlier, money-losing venture called Rabbit. Orange was the refined version of the thesis—bigger market, better execution, better timing. And when the market was willing to pay a peak price, Li didn’t hesitate.

In October 1999, Hutchison sold its 45% stake in Orange plc to Germany’s Mannesmann AG for $14.6 billion, paid partly in cash and partly via a 10% interest in Mannesmann. A few months later, in February 2000, Vodafone AirTouch acquired Mannesmann, which left Hutchison with a 5% stake in Vodafone. Hutchison then sold 30% of that Vodafone stake, raising about $5 billion and pushing its cash pile to more than $13 billion.

The company itself later framed the logic plainly: CK Hutchison builds businesses and sells when shareholder value can be crystallized. On Orange, it recorded a profit of US$15.12 billion.

And the timing really was surgical. Li sold into the top of the telecom bubble—before gravity returned.

Mannesmann’s purchase of Orange helped set off Vodafone’s hostile pursuit of Mannesmann. After Vodafone won, it couldn’t keep Orange anyway; EU regulations wouldn’t allow it to hold two mobile licences. So Vodafone divested, and in August 2000, France Télécom bought Orange plc from Vodafone for an estimated €39.7 billion.

At the turn of the century, The Times and Ernst & Young in the UK named Li Ka-shing Entrepreneur of the Millennium.

The Orange sale captured Li’s philosophy in one clean arc: build from nothing, ride the wave, exit when the world is most optimistic. The telecom bubble would pop soon after, vaporizing enormous value for anyone still dancing when the music stopped.

And it also revealed something deeper about the Li playbook: he wasn’t wedded to any single industry. He was wedded to cycles—and to the discipline of selling when the price was right.

Which mattered, because the next chapters of this empire would be built with the dry powder Orange helped create.

VI. The China Pivot: Geopolitics Reshapes Strategy (2012-2015)

Around 2012, something shifted in the Li empire’s orientation. Not a flashy acquisition, not a new business line—something quieter, and more consequential: a re-reading of where power was headed. What followed would become one of the most debated—and, in hindsight, most strategic—calls of Li Ka-shing’s career.

There are unverified rumours that, when Xi Jinping rose to the top in 2012, Li did what Hong Kong’s tycoons traditionally did: he went north to pay his respects and establish the relationship. The story goes that he waited in Beijing for days, and was ultimately spurned. Whether or not that meeting happened exactly that way, the observable outcome is hard to miss. In the years that followed, the group steadily tilted away from mainland China.

From 2013 onward, Cheung Kong Holdings began restructuring its mainland footprint—selling real estate, retail chains, and other assets, and recycling that capital into overseas holdings, especially in Europe. Over time, mainland China’s share of revenue shrank dramatically—from 16.4% in 2011 to 7.4% by 2023. And crucially, these moves were not subtle. Practically all the headline M&A associated with the mainland were disposals, funding acquisitions elsewhere. Beijing noticed.

In the boom years of China’s economic miracle, being a “good businessman” and being a “patriot” were often treated as the same thing. Li had long been viewed as Beijing-friendly, and his willingness to invest in China carried symbolism: it was a vote of confidence from the region’s most celebrated dealmaker. So when he started moving capital out, the reaction wasn’t just commercial—it was political.

In September 2015, the backlash became public and personal. A think tank affiliated with Xinhua published an op-ed that ricocheted through mainland media under a now-famous headline: “Don’t let Li Ka-shing run away.” It accused him of forgetting the “favours” of the motherland, of bolting the moment growth slowed, and of spreading pessimism at a “sensitive time.” It framed his asset sales not as portfolio management, but as moral failure—an “ingratitude” narrative aimed at someone who had once been held up as proof that Chinese capitalism could thrive.

The criticism didn’t stop there. Commentary echoed the idea that Li’s success wasn’t merely market-driven—that it had been enabled by connections and preferential access, including discounts on prime land. This was unusual territory: a public scolding of a figure who had, for decades, been treated as a kind of unofficial ambassador between Hong Kong capital and mainland power.

Then, almost as suddenly as it began, it stopped. A government media directive dated 18 September—later leaked—told outlets to stop “hyping” reports and commentary about Li divesting from the mainland. Within days, the tone shifted from denunciation to damage control. Securities Times ran a piece that captured the new posture: “Let Li Ka-shing go, the sky won’t collapse.”

Li’s response was just as carefully measured. Cheung Kong issued a statement dismissing the allegations that it was “withdrawing” from China and pushing back on the personal nature of the attacks. In a rare moment of sharper language from an operator known for restraint, the statement criticized the tone as reflecting a kind of “cultural revolution mentality.” At the same time, it positioned Li as loyal but aggrieved—suggesting he hadn’t responded sooner to avoid creating a distraction during President Xi’s visit to the United States. The message was clear: he wouldn’t accept the smear, but he also wouldn’t escalate the fight.

The tension didn’t disappear. In 2019, Li again drew criticism from state media—this time for urging “humanity” in the treatment of pro-democracy protesters in Hong Kong, and for refusing to offer the kind of full-throated condemnation Beijing wanted. During the protests, he placed advertisements in papers like the South China Morning Post using classical poetry—subtle calls for calm, paired with a visible empathy for younger people’s grievances. It was a very Li Ka-shing move: communicate without declaring war.

Stepping back, the pattern is the point. The group was early to a new reality: the current Chinese administration was not going to treat private capital the way previous leaders had. The era of “grow fast, get rich, everyone wins” was fading. And Li adjusted before the rest of the market fully internalized it.

That pivot wasn’t just defensive. It was opportunistic. As capital flowed out of China, it flowed into long-lived, cash-generating assets abroad—particularly European infrastructure. The bet was that the West’s stable legal systems and recurring-income businesses would be the right place to park money for the next decade. In time, CK Hutchison’s revenue mix tilted heavily toward Europe, while mainland China and Hong Kong became a much smaller slice.

It was geopolitics as portfolio construction. And it set the stage for the next turning point—because once you’ve decided the world has changed, the logical next move is to rebuild the corporate machine to match it.

VII. The 2015 Mega-Restructuring: Separating Property from Everything Else

By 2015, the Li empire had become almost too successful at what it did best: compounding complexity. Cross-holdings, listed vehicles owning chunks of other listed vehicles, operating businesses intertwined with property—an architecture that made sense to insiders, but was famously hard for outside investors to model.

So Li Ka-shing did something that looks, on paper, like corporate housekeeping. In reality, it was the biggest reorganization of the group since the 1979 Hutchison coup—and it was designed for three things: simplify the structure, draw a bright line between business types, and make the eventual handoff to the next generation cleaner.

The headline move was dramatic: Cheung Kong Holdings offered $24 billion in stock to buy out the Hutchison Whampoa shares it didn’t already own, while spinning off the property assets into a separate listed company.

In January 2015, Li confirmed the plan. Cheung Kong Holdings would acquire the remaining shares of Hutchison Whampoa and consolidate the two under a new single holding company: CK Hutchison Holdings. That new holding company was established on 18 March 2015—incorporated in the Cayman Islands, but listed in Hong Kong.

Then the flip happened fast. On 3 June 2015, Hutchison Whampoa was delisted. On that very same day, the group’s property business—pulled together from the existing property assets of both Cheung Kong and Hutchison—began trading as a new listed company, Cheung Kong Property Holdings.

In other words: one public stock for the non-property empire (telecoms, infrastructure, energy, retail, aircraft leasing, ports), and one public stock for property.

CK Asset Holdings began trading on 3 June 2015. After the restructuring, Cheung Kong Holdings and Hutchison Whampoa went private, replaced as the group’s main listed flagships by CK Hutchison Holdings and CK Asset Holdings. Immediately after it debuted, CK Asset entered the Hang Seng Index—the blue-chip index of the Hong Kong stock exchange.

The strategy underneath all of this was straightforward, and unusually shareholder-readable for a conglomerate. First, it untangled a layered pyramid where Cheung Kong owned roughly half of Hutchison, and Hutchison owned stakes across a range of other companies. That structure could be powerful—but it was opaque, and opacity invites a discount. Second, it created clear delineation between property (CK Asset) and everything else (CK Hutchison), so investors could choose what they wanted to own without buying the whole maze. Third, it set the stage for succession: clearer lines, clearer accountability, fewer hidden levers.

And there was a quieter benefit too. By shifting the holding company’s registration to the Cayman Islands, the group gained additional corporate flexibility—an advantage that didn’t feel urgent in earlier decades, but mattered a lot more in an era of rising geopolitical uncertainty.

VIII. The UK Bet: From Prime London Real Estate to 2,700 Pubs

If the China pivot was about reading politics, the UK bet was about trusting institutions. The Li family increasingly wanted assets where the rules were stable, contracts were enforced, and cash flows could compound quietly—less emerging-market thrill ride, more developed-market annuity.

Long before the pubs, CK Asset had been steadily “hoovering up” prime London real estate—projects and landmarks like 5 Broadgate, the Chelsea Waterfront development, Belgravia Place, and Royal Gate Kensington. And the baton pass was visible early. In June 2018, just one month after officially taking over from his father, Victor Li oversaw the company’s purchase of the UBS headquarters in London from GIC and British Land for £1 billion.

Then came the deal that made everyone do a double-take.

In 2019, CK Asset moved from owning UK property to owning a very British institution: the pub. The company agreed to buy Greene King plc in a transaction valued at £4.6 billion, adding roughly 2,700 pubs, restaurants, and hotels to the portfolio. The structure was simple in concept but big in implication: CK Bidco, a newly incorporated CK Asset subsidiary, paid £2.7 billion in cash and assumed about £1.9 billion of net debt. Greene King shareholders approved the takeover, and the company—previously listed on the London Stock Exchange—was acquired in October 2019.

On paper, Greene King looked like an unusual target for a Hong Kong developer. It was a brewer and pub operator, best known for beers like Greene King IPA and Abbot Ale—among the top-selling cask ales in Britain. And it wasn’t exactly riding a growth wave: for the year ending 28 April 2019, net profit after tax fell to £120 million from £183 million the year before, which the company attributed to a mix of headwinds including Brexit fallout and waning pub popularity among younger Britons.

But that tension is exactly what made the deal feel like a Li-family trade. Greene King was heavily exposed to domestic UK spending, and since the 2016 Brexit referendum its share price had sunk to a low. When CK Asset announced the acquisition, Greene King’s stock jumped more than 50% in a day. For CK Asset, it looked like a Brexit bargain—helped along by a weaker pound, which made UK assets cheaper for overseas buyers.

And the investment thesis wasn’t really about beer. It was about property. Greene King owned, or held long-term leases on, 81% of its sites. The BBC reported that a recent revaluation put the property portfolio’s market value at about £4.5 billion, versus a book value reported at about $3.5 billion. In other words: a pub company with a real estate backbone—exactly the kind of “cash flow plus underlying land” profile CK Asset likes.

The UK buildout didn’t stop there. In 2023, CK Asset pushed further into defensive, income-oriented real estate by targeting social infrastructure. It made a US$612.9 million offer for London-listed Civitas Social Housing, a REIT focused on social care housing and healthcare facilities in the UK. The offer was all-cash at 80 pence per share, valuing the deal at £485 million, according to a Hong Kong stock exchange filing. On 23 June 2023, CK Asset announced the offer had become unconditional, representing a 44.4% premium to Civitas’ closing share price on the last business day before the offer period began. CK Asset described Civitas as one of the leading UK social housing providers, with a social impact and earnings profile that fit its investment criteria.

Step back, and the pattern becomes clear: this isn’t “Hong Kong money buying foreign trophies.” It’s a deliberate diversification into recurring-income assets with real estate underneath them—first prime London property, then pubs, then social housing.

The result is a far more geographically balanced business. Revenue now comes broadly one-third from Hong Kong, one-third from the UK, around 10% from mainland China, and the remaining quarter from the rest of the world.

IX. The Generational Handoff: From Superman to Victor Li (2018)

On 10 May 2018, an era in Hong Kong business formally ended. Li Ka-shing—89 years old, and for decades the face of the city’s most formidable conglomerate—stepped down as chairman and handed the reins to his elder son, Victor.

Li didn’t vanish. From that day, he became Senior Advisor of both CK Asset Holdings and CK Hutchison Holdings. It was the title that signaled continuity: after 46 years leading the CK Group through diversification and globalisation—through mergers and acquisitions, organic growth, and periodic restructurings designed to unlock shareholder value—he would still be in the room, just no longer at the head of the table.

Victor Li Tzar-kuoi (born 1 August 1964) took over as Chairman and Managing Director of CK Asset Holdings, and as Chairman and Group Co-Managing Director of CK Hutchison Holdings. He also became Chairman of CK Infrastructure Holdings. On paper, it was a clean succession. In reality, it was the culmination of a handoff that had been in motion for decades.

Victor’s climb was steady and deliberate. He joined Cheung Kong (Holdings) in 1985, became Deputy Managing Director from 1993 to 1998, and was Deputy Chairman from 1994. In 1999 he became Managing Director, and by 2013 he was Chairman of the Executive Committee—roles he held until the 2015 restructuring. On the Hutchison side, he served as an Executive Director from 1995 to 2015, and as Deputy Chairman from 1999 to 2015. If the 2015 reorg was meant to simplify the empire, Victor’s résumé explains another reason it worked: he had already been living inside the machinery that was being rebuilt.

He also had operating credibility early. Victor began by running Husky Energy in Canada, then returned to Hong Kong in 1990 to work at Cheung Kong headquarters and rose quickly through the group’s leadership ranks.

His story, though, isn’t only boardrooms and titles. In 1996, Victor was kidnapped on his way home after work by the notorious gangster Cheung Tze-keung, known as “Big Spender.” Li Ka-shing paid a ransom of HK$1.038 billion, delivered directly to Cheung at Li’s home. Victor was reportedly released after one night. No report was filed with Hong Kong police; the case was instead pursued by mainland authorities, and Cheung was executed in 1998—an outcome that wouldn’t have been possible under Hong Kong law.

For investors, the drama that matters most came later: what happens to capital allocation when “Superman” steps back and the next generation steps forward? Officially, Victor became chairman in 2018 and Li Ka-shing became Senior Advisor. Unofficially, it was never going to be a clean break. Victor had been given more responsibility and more capital to deploy over a long stretch of time; and even after stepping down, Li kept an office at headquarters—and, by most accounts, likely retained influence on major decisions.

The portfolio itself reflected the transition. Property sales—the entire business when Li first built Cheung Kong in Hong Kong—made up 45% of CK Asset’s income in the year after Victor took over as chairman. The rest came from recurring streams like rental income, pub operations, and infrastructure investments, a mix that matched the group’s pivot toward stability and long-duration cash flows.

The succession question, though, didn’t go away with the press release. It became the new debate at the center of the story: can the second generation sustain the dealmaking instincts and discipline that built the empire? The early evidence has been mixed.

X. Modern Era: Navigating Hong Kong's Property Downturn (2020-Present)

Victor Li inherited the chair at a brutal time to be a Hong Kong property developer. The city ran a gauntlet: the 2019 protests, COVID-19, China’s property crisis, and then a long, interest-rate tightening cycle that squeezed affordability and sentiment all at once.

The numbers reflect that pressure. CK Asset’s attributable profit fell in 2024, down to HK$13.7 billion from HK$17.3 billion the year before, according to a filing with the Hong Kong exchange.

By the first half of 2025, the story got more nuanced. CK Asset reported revenue of HK$39.13 billion, up 12.7% year-on-year, and said recurring profit contributed 83% of the total. But net profit still fell 26.2%, dragged down by revaluation losses—paper losses that hit the income statement when asset values are marked down, even if nothing is actually sold. Operationally, the steadier parts of the portfolio—things like infrastructure, utilities, and hotels—held up better.

The weakness was exactly where you’d expect: Hong Kong retail and commercial property. Management said those sectors remained soft in the first half of 2025, and that contributions from the Civitas social infrastructure portfolio in the UK helped offset the local drag.

In interim results released that Thursday, CK Asset posted HK$6.3 billion in attributable profit for the first six months of 2025, down 26.2% from a year earlier, as declining property values weighed on the balance sheet. The company took a HK$503 million hit to the fair value of its investment properties, reversing a HK$1.9 billion uplift in the first half of 2024. But strip out those fair-value swings and the underlying engine looked steadier: profit rose 1.6% year-on-year to HK$6.8 billion, supported by growing contributions from its UK pub operations and its infrastructure and utility joint ventures in the UK and Europe—helping cushion declines in property sales and leasing.

And the broader market backdrop has been unforgiving. Hong Kong’s residential property price index fell 7.76% year-on-year in Q1 2025, following year-on-year declines in every quarter of 2024—making it the thirteenth consecutive quarter of falling prices, according to the Ratings and Valuation Department.

Some estimates put the drawdown at nearly 30% from the 2021 peak, a decline tied closely to a slowing mainland economy and a weaker yuan.

Meanwhile, the primary market has its own problem: too much supply. As of March, developers were sitting on roughly 93,000 unsold units. At the current pace of sales, clearing that backlog would take nearly 57 months—well above the six-year average of 51.3 months. The implication is painful but straightforward: absent a sharp improvement in demand, developers are likely to keep cutting prices, and the correction could drag on until 2026.

Through all of this, Victor Li has leaned into the family’s signature posture: stoic, conservative, and prepared. He said CK Asset would weather the “doldrums” in Hong Kong’s commercial leasing market amid global uncertainty. “No industry in this world is always well-performing, and demand for Hong Kong's retail and office properties is indeed slow at the moment,” he told shareholders at the annual general meeting. Then he pointed to the buffer that the whole conglomerate era was designed to build: with about 88% of profit contribution coming from recurring-income projects, CK Asset can absorb a weak leasing market far better than a pure developer.

He also emphasized balance-sheet strength—what he called a war chest for unforeseen events as Hong Kong endures a “stress test.”

That financial discipline shows up in leverage. The company cited net debt to shareholders’ funds of 5.4%, and a net debt to net total capital ratio around 5%. As of 30 June 2024, net debt to net total capital was approximately 5.5%. CK Asset also maintained “A/Stable” and “A2 Stable” credit ratings from Standard & Poor’s and Moody’s, respectively, reinforcing the message that this is still a conservatively financed business even in a down cycle. Moody’s rates it A with a stable outlook, and S&P rates it A with a stable outlook.

Zoom out further and you get the investor’s dilemma. If you bought Cheung Kong Holdings at its IPO and held through all the restructurings and corporate actions, you’d have roughly an 8% compounded annual return overall. The first era was outstanding: about 12.5% CAGR from 1972 to 2015. The second era has been punishing: about -8.5% from 2015 to today. That gap—between the empire’s golden run and the last decade’s underperformance—is the crux of the modern CK Asset debate.

It’s tempting to pin that underperformance on the moment Victor gained more control. But it’s hard to argue it’s all on him. The market didn’t love the group’s tilt toward European investments versus Hong Kong and mainland China, which it viewed as lower-return. And then, one after another, came the macro body blows: protests, COVID, and the bursting of China’s real estate bubble. Even “Superman” would have had trouble making that tape look pretty.

XI. Playbook: Business & Investing Lessons

Take the CK Asset story as a whole—from a plastics workshop in 1950s Hong Kong to a global portfolio of property, infrastructure, and pubs—and a few principles show up again and again. Not slogans. Actual operating habits that shaped outcomes for decades.

Timing is everything. Li Ka-shing’s most iconic moves weren’t just “good deals.” They were good deals at moments when other people couldn’t, or wouldn’t, act. The 1979 Hutchison Whampoa acquisition happened when Hutchison was struggling and HSBC was motivated to exit. The push into the UK accelerated as Brexit uncertainty dragged down sterling and sentiment. And the Orange sale in 1999 wasn’t simply a win—it was a win captured at the top of the telecom cycle. That pattern isn’t luck. It’s contrarian discipline, plus the patience to wait for the pitch you actually want.

Geopolitical awareness matters. Starting around 2012–2013, the Li family began reducing exposure to mainland China while many peers were still leaning in. Capital shifted toward European infrastructure and UK real estate—assets with stable legal regimes and recurring-income profiles. Whatever you think of the politics, the business takeaway is clear: for conglomerates, geopolitics isn’t “background noise.” It changes the rules of the game, and the best operators move before the change becomes consensus.

Conservative leverage preserves optionality. CK Asset has consistently run with unusually low debt for a property group—citing net debt to shareholders’ funds of 5.4%, and net debt to net total capital around 5%. That restraint isn’t about being timid. It’s about staying liquid and flexible when the cycle turns. In downturns, leverage doesn’t just reduce returns—it removes choices. CK Asset’s ability to do deals like Greene King or Civitas during periods of stress flowed directly from having dry powder when others didn’t.

Diversification by geography and asset class. This started as a Hong Kong property developer. It became something closer to a global, real-asset portfolio manager: Hong Kong residential and commercial property, UK pubs, UK social housing, and investments tied to infrastructure and utilities. The strategic benefit is simple: fewer single-market hostage situations. When Hong Kong is weak, the UK or Europe can carry more of the load, and recurring-income assets can smooth what would otherwise be a brutally cyclical earnings profile.

The family dynasty model. This wasn’t a last-minute succession. Li Ka-shing spent decades preparing Victor—giving him real operating experience (including in Canadian oil), then progressively larger roles across the group’s core companies, and finally a simplified corporate structure after the 2015 reorganization. Whether the second generation matches the first is an open question. But the method—apprenticeship, responsibility over time, and a planned transition—is as intentional as succession gets in a family-controlled empire.

Related party transactions require scrutiny. The Li universe is a web: multiple listed entities, cross-holdings, and transactions between related companies. That can be efficient, but it also creates constant governance homework for minority shareholders. None of it is automatically bad—but the complexity raises the bar. Investors have to understand where value is being created, where it’s being moved, and who benefits.

The “buy and build” versus “buy and flip” dichotomy. Orange was the classic “build it and exit” trade: create a valuable operator and sell when the market is euphoric. Greene King was the opposite: buy a mature business because the cash flows are steady and the real estate is foundational, with no obvious intention to sell. CK Asset’s history shows it’s not ideological about holding periods. It’s opportunistic—and it matches the strategy to the asset, the cycle, and the moment.

XII. Porter's 5 Forces & Hamilton's 7 Powers Analysis

Porter's 5 Forces for Hong Kong Property Development:

1. Threat of New Entrants: LOW

Hong Kong property is one of the hardest games in the world to break into. The government effectively controls the pipeline by releasing land through periodic auctions—often in expensive, large parcels that naturally favor the biggest balance sheets. That dynamic has concentrated the market for years: CK Asset and Sun Hung Kai Properties together accounted for roughly 70% of new private home development by 2010, a concentration often tied directly to the land auction system. And even if a new entrant had the money, they’d still need time—decades—to build a land bank, plus the relationships with lenders and the government that let projects move smoothly.

2. Bargaining Power of Suppliers: MODERATE

Land is the critical input, and the government is the dominant supplier—so at first glance, supplier power looks overwhelming. But the biggest developers have partly insulated themselves by accumulating land over long periods, which reduces how urgently they need each new auction. On the construction side, there are plenty of contractors competing for work, which limits how much pricing power any one supplier can exert.

3. Bargaining Power of Buyers: MODERATE TO HIGH

In a soft cycle, the buyer suddenly matters a lot more. With about 93,000 unsold units sitting in the primary market pipeline as of early 2025, developers have been pushed into offering discounts and sweeteners just to keep sales moving. Over the long run, Hong Kong’s structural housing constraints put a floor under demand. But in the here and now, when inventory is heavy and sentiment is weak, buyers get to be choosy.

4. Threat of Substitutes: LOW

There’s no true substitute for physical space. Yes, people can rent instead of buying, and companies can shrink or redesign offices—but at the end of the day, living and working still requires real estate. The “substitution” is mainly about timing and tenure, not about replacing the product entirely.

5. Competitive Rivalry: HIGH

The competitive set is crowded at the top: CK Asset, Sun Hung Kai, Henderson Land, New World Development—all large, all experienced, all fighting in the same market with similar cost structures. When demand weakens, rivalry doesn’t fade; it sharpens. The downturn has turned pricing into a knife fight as developers try to clear inventory and protect cash flow.

Hamilton Helmer's 7 Powers:

Scale Economies: MODERATE. CK Asset’s size helps in procurement, project management, and capital access. But property development doesn’t scale as cleanly as a factory; every project is still local, bespoke, and exposed to the cycle.

Network Effects: LIMITED. A flat isn’t Facebook. One buyer doesn’t make the next buyer’s unit more valuable simply by participating.

Counter-Positioning: POTENTIAL. CK Asset’s geographic diversification can act as a form of counter-positioning versus developers that are effectively “all-in” on Hong Kong and mainland China. If peers are constrained by the mainland property crisis and weak funding conditions, they can’t quickly replicate a global, recurring-income portfolio without years of patient execution.

Switching Costs: LIMITED. For most buyers, property transactions are one-off decisions. There isn’t much of a “lock-in” effect that forces people back to the same developer.

Branding: MODERATE. The Cheung Kong name still carries weight in Hong Kong—reputation matters when you’re buying the most expensive purchase of your life. But branding has limits in a market where location, price, financing, and timing usually dominate the decision.

Cornered Resource: LIMITED. Land banks are a real advantage: CK Asset’s accumulated positions in Hong Kong can’t be recreated overnight. That said, land ultimately comes from government auctions, so it’s not permanently cornered—just difficult to assemble at scale.

Process Power: POTENTIALLY SIGNIFICANT. This is the one that feels most “Li Ka-shing.” The group’s institutional ability to source deals, structure them conservatively, and time entries and exits—ports, power, telecoms, the Orange sale, and later the UK pivot—arguably functioned as a repeatable capability competitors struggled to match. The open question now is whether that process power was primarily Li himself, or something durable enough to keep compounding under the next generation.

Key KPIs to Monitor:

For investors tracking CK Asset’s performance, three metrics are especially revealing:

-

Net Debt to Total Capital Ratio: Around 5%, this is the “staying power” metric. If it rises sharply, it suggests stress—and reduces the flexibility that has historically defined the group.

-

Recurring Income as Percentage of Total Profit: Roughly 83–88%, this shows how much of the business has shifted from cyclical development profits to steadier, annuity-like cash flows.

-

Hong Kong Property Sales Margins: In a discount-heavy market, margins tell you who has land-cost discipline and who’s being forced to buy volume with price cuts.

XIII. Bull Case and Bear Case

The Bull Case:

The optimistic view is that CK Asset is a high-quality collection of global, real-asset businesses being priced like a problem. The market is looking at Hong Kong’s downturn and marking everything down, even though the company is built to survive exactly this kind of cycle.

Start with the balance sheet. CK Asset has run unusually low leverage for a property group—around 5% net debt to capital, versus peers often far higher. Pair that with investment-grade credit ratings and you get something that matters more than any one-quarter earnings print: staying power. In property, staying power is optionality. It lets you hold assets through the trough, avoid forced selling, and, if you’re brave, buy when others can’t.

Then there’s diversification. The UK bet—Greene King’s 2,700-plus pubs and Civitas’s social housing portfolio—wasn’t about collecting quirky trophies. It was about buying recurring income streams with real estate underneath them. And in the current Hong Kong slump, those overseas cash flows have done what they were supposed to do: soften the blow when the home market is weak.

You can see it in the recent operating performance. In the first half of 2025, once you strip out the accounting swings from property revaluations, underlying profit rose 1.6% year-on-year to HK$6.8 billion. The lift came from growing contributions from the UK pub business and from infrastructure and utility joint ventures in the UK and Europe. Profit from that segment rose 12.3% to HK$4.6 billion, helped by joint ventures including the group’s stake in Northumbrian Water in England and Wales, and its holding in European energy management provider Ista Group.

Finally, there’s the cycle itself. Hong Kong property prices have fallen sharply from the 2021 peak, which suggests a lot of the pain is already in the numbers. If and when the market stabilizes, CK Asset has the land bank, the execution capability, and the liquidity to lean in—exactly the setup that historically rewarded the Li family’s style of investing.

The Bear Case:

The pessimistic view is that “cheap” can stay cheap for a long time—especially when the core market is still searching for a floor.

Hong Kong’s property downturn may not be done. With a heavy inventory overhang, clearing unsold new units at the current pace could take close to 57 months, well above the longer-term average. Without a meaningful improvement in demand, developers may keep cutting prices simply to move volume. In that scenario, the correction could drag on into 2026.

Then there’s succession—always the hard part of dynasties. Li Ka-shing’s reputation wasn’t built on one lucky deal; it came from decades of relationships, intuition, and timing that proved almost unfair. Investors can’t help noticing that long-run returns look dramatically different before and after 2015: if you bought Cheung Kong Holdings at IPO and held through the corporate actions, you’d have roughly an 8% CAGR overall, driven by a strong run from 1972–2015 and a painful stretch since. Victor Li’s era has coincided with weaker returns, and whether that’s leadership, macro, or both is the debate.

Geopolitics is another overhang. The relationship between China and Hong Kong has changed materially, and the Li family’s balancing act—independent capital allocation while operating in a politically charged environment—has drawn criticism at different times. That pressure isn’t going away.

Even the UK diversification, while stabilizing, isn’t risk-free. Greene King came with meaningful assumed debt, and it operates in mature, competitive markets where long-term consumer habits can shift against pubs. Social housing, meanwhile, is ultimately downstream of government policy and funding.

And finally: governance. Family-controlled conglomerates with complex cross-holdings often trade at a discount for a reason. Minority shareholders have to trust that related-party dealings are fair, and that the family’s interests remain aligned with public investors across cycles and restructurings.

The Verdict:

CK Asset looks like a quality franchise trading under a cloud. Whether it’s an opportunity or a value trap depends on three questions: first, how much further Hong Kong property values fall before stabilizing; second, whether Victor Li and his team can keep executing the diversification strategy with the same discipline that defined the founding era; and third, how to price the option embedded in CK Asset’s financial flexibility.

For long-term investors who can tolerate Hong Kong exposure and live with the realities of a family-controlled empire, the setup can look compelling—depressed sentiment, strong assets, and a balance sheet built to endure. For investors who need near-term catalysts, or who simply don’t want governance complexity, it may still feel too early.

Historically, the stock has rewarded buying at moments of maximum pessimism. The only question is whether this is one of those moments—or just another stop on the way down.

XIV. Conclusion: The Legacy Question

As 2025 draws to a close, CK Asset stands at the kind of crossroads that only a few companies ever reach. What began with a teenager grinding through brutal shifts and a small plastics workshop has become a global real-asset machine: Hong Kong towers, UK pubs, and long-lived infrastructure and utility exposure across Europe.

In a way, the Li family’s arc is Hong Kong’s arc. The city went from export manufacturing outpost to global financial center; from British colony to Special Administrative Region; from a straightforward “China growth” story to a far more complicated act of geopolitical balance. And the CK empire was built the same way Hong Kong was built: through timing, restraint, and a willingness to move before the rest of the market agreed the world had changed.

Li Ka-shing, now 97, is still there as Senior Advisor—still the symbol of frugality and discipline that shaped the culture. But the center of gravity has shifted. Victor Li has already had to lead through a modern stress test: protests, COVID, a property downturn, and a world where capital and politics are increasingly intertwined. The next challenge is the hardest one for any dynasty: not simply protecting what was built, but proving the engine still works without the founder’s hand on the wheel.

As Li once put it: “It doesn't matter how strong or capable you are. If you don't have a big heart, you will not succeed.”

For investors, CK Asset remains an evergreen debate: a portfolio of high-quality assets that can look mispriced in moments of pessimism, paired with the permanent frictions of Hong Kong exposure and family control. The Li family has earned credibility the hard way, over decades. But markets don’t grade on legacy—they grade on what comes next.

The company was named for the Yangtze River, gathering countless tributaries into a single current. The question now is whether the flow keeps compounding under the next generation—or whether the empire built by “Superman” turns out, like every other, to be subject to gravity.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music