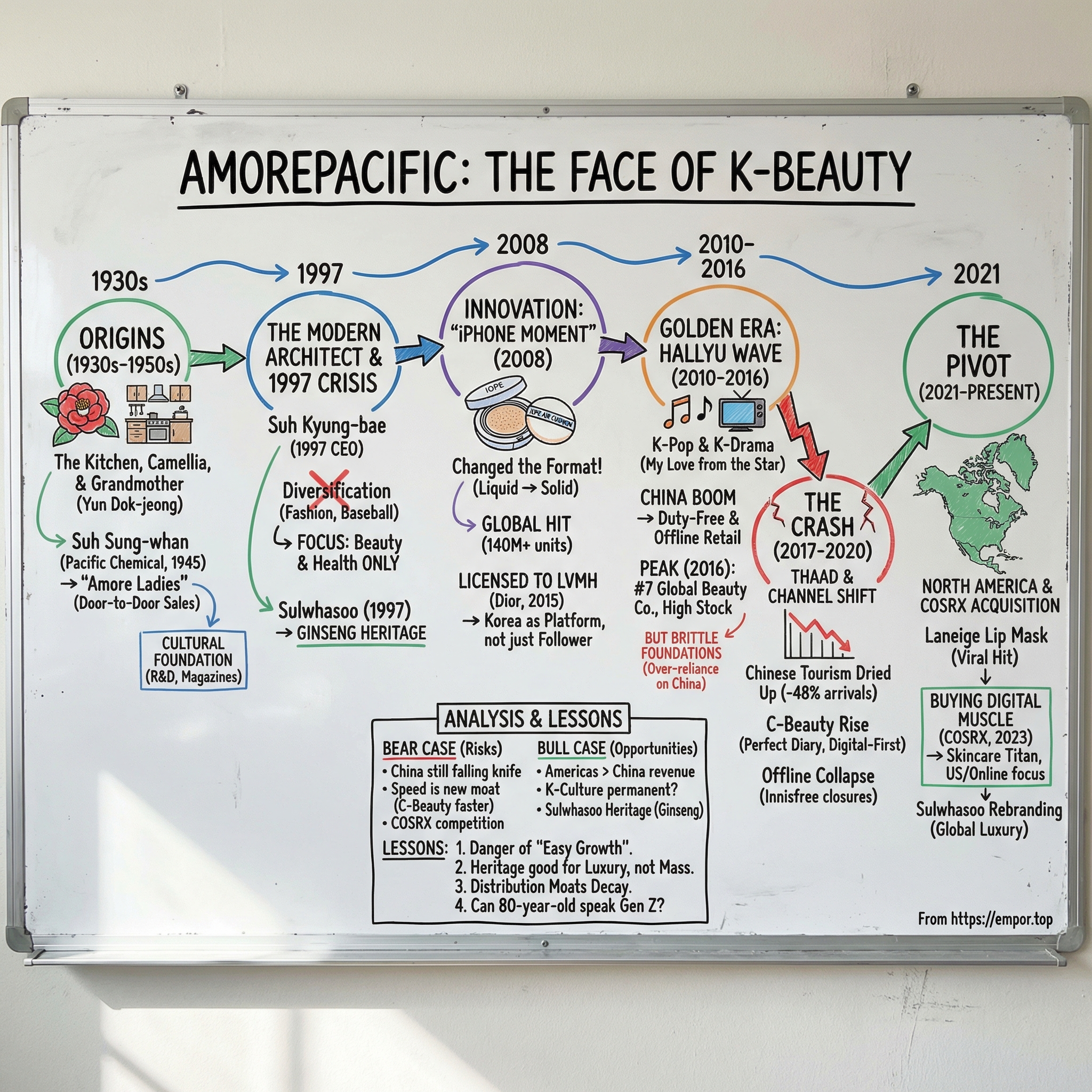

Amorepacific: The Face of K-Beauty

I. Introduction: The "Asian L'Oréal"

Picture this: a cosmetics executive from Paris lands in Seoul in 2015 expecting to pick up a few “interesting local trends.” Instead, she walks into a scene that feels closer to a product launch than a shopping district—crowds of Chinese tourists queued for hours outside a department store. Not for handbags. Not for phones. For skincare: jars of ginseng cream and futuristic-looking cushion compacts, all stamped with the name of a company she barely knows.

That company is Amorepacific.

On paper, Amorepacific is a South Korean beauty heavyweight with more than 30 brands across beauty, personal care, and health—Sulwhasoo, Laneige, Etude, Aestura, Cosrx, AP Beauty, Innisfree, and plenty more. But a list of brand names doesn’t capture what made it so powerful. Amorepacific didn’t just participate in K-Beauty. It helped define it—and in doing so, rewired how hundreds of millions of people around the world think about skincare.

By the mid-2010s, it wasn’t merely Korea’s biggest cosmetics company; it had become one of the ten largest cosmetics companies globally. At the peak in 2016, the market rewarded it like a once-in-a-generation consumer story: the stock became one of the hottest plays in Asia, and its chairman briefly rose to become the second-richest person in South Korea.

And then the music stopped.

A geopolitical clash with China—South Korea’s largest trading partner—hit where Amorepacific was most exposed. The company’s most lucrative channels, built around Chinese tourism and duty-free shopping, seized up almost overnight. At the same time, the market itself was changing under their feet: consumers were shifting from offline retail to e-commerce, and fast-moving domestic Chinese brands were rising with products that were cheaper, quicker, and built for the new platforms. In Q2 2017, Amorepacific reported operating profit down 58% year-on-year, sales down 16.5%, and net profit down 59.8%.

What followed has been nearly a decade-long attempt at one of the hardest pivots in consumer goods: going from an Asia-centric powerhouse—dangerously dependent on Chinese tourism—to a more balanced global beauty company, with the Americas and Europe increasingly driving growth. In a milestone of that rebalancing, the Americas surpassed Greater China in annual sales for the first time in the group’s history.

Whether this reinvention works matters far beyond one company’s shareholders. It’s a stress test for a bigger question: can a heritage-driven brand machine adapt when trends move at TikTok speed? This is a story about the beauty of heritage versus the tyranny of trends.

II. Origins: The Kitchen, The Camellia, and The Grandmother

Amorepacific’s origin story reads less like a corporate founding myth and more like a family legend. It starts in the 1930s, not in a gleaming office tower, but in a modest kitchen in Kaesong—today just across the border in North Korea.

That’s where Yun Dok-jeong, later remembered as “Madame Yun,” began making camellia oil by hand and selling it locally. Camellia oil—light, clean, and long used in Korean homes for hair and skin—wasn’t a new invention. What was new was the way she treated it: as something worth doing perfectly. Her oil became popular enough that, in 1937, she formalized the work by opening Changseong Store, the small seed that would eventually become Amorepacific.

People didn’t just come for the product. Yun was known for her generosity—feeding visitors, helping neighbors, treating customers like guests. But she paired that warmth with a hard line on quality. She insisted on the best raw ingredients and refused to cut corners on the one thing she sold. That combination—care for the customer and obsession with the input—became the company’s earliest operating system.

Her second son, Suh Sung-whan, grew up inside that system. Born in 1924 during Japanese colonial rule, he learned the trade early by helping his mother in Kaesong. When the Korean War split the peninsula, the family fled south with little more than their know-how and Yun’s philosophy.

In 1945, Suh took over and began reshaping the business into something far bigger, eventually naming it Taepyeongyang—“Pacific Ocean”—a statement of intent as much as a company name. Pacific Chemical, as it was known, wasn’t thinking like a local shop anymore. Suh kept a globe on his desk and reportedly spun it so often while studying overseas markets that parts of it wore away.

But the most important move he made wasn’t about branding or global ambition. It was about distribution—and people.

In the years after the war, Korea was devastated, families were rebuilding from scratch, and formal jobs for women were scarce. Suh built a door-to-door sales program—Amore Ladies—that both expanded Amorepacific’s reach and offered women a real way to earn income. Under the social and political currents of the era, Korean women were increasingly pulled into new economic roles, and Amorepacific didn’t just benefit from that shift; it helped create a pathway for it.

The Amore Ladies—often described as ahjummas, the neighborhood middle-aged women everyone knew—became something more than a sales force. They were trusted guides. They didn’t simply sell cream; they sold confidence, modernity, and practical beauty advice to women who were trying to put normal life back together. For Amorepacific, it was a cornered resource: a distribution advantage rooted in human relationships that competitors couldn’t easily copy.

At the same time, the company built the scaffolding of a modern beauty business in Korea. It opened the country’s first cosmetics research lab in 1954. It published a monthly beauty magazine, Hwajanggye, in 1958. It institutionalized door-to-door selling in the 1960s, and by the early 1970s it was running national makeup campaigns—teaching, shaping, and standardizing what “beauty” looked like in a rapidly changing country.

So from the beginning, Amorepacific wasn’t only selling products. It was building an industry, educating a market, and embedding itself into everyday life. That cultural foundation—laid in a Kaesong kitchen and scaled through neighborhoods across Korea—would later become the platform K-Beauty launched from.

III. The Modern Architect & The 1997 Crisis

In 1997, as the Asian Financial Crisis tore through the region, Suh Kyung-bae was handed what in hindsight looks like both an inheritance and a trap: the keys to his father’s empire at the exact moment it might collapse.

Suh Sung-whan passed control to his second son that year. And like many Korean chaebols in the boom years, Pacific had sprawled far beyond its roots—into fashion, electronics ventures, even a baseball team. It was the kind of diversification that looks smart in a rising tide and lethal when the tide goes out. By 1997, the group was bloated with non-core assets, bleeding cash, and staring down an existential reckoning.

Kyung-bae’s response wasn’t incremental. After being appointed CEO of Pacific Corporation in 1997, he set out to rebuild around what he believed the company actually knew how to do: beauty and health. What followed was a true “burn the boats” move. He sold everything except cosmetics. Not most things. Not the underperformers. Everything. It was radical surgery—especially for a mature conglomerate—done in the middle of a crisis when there’s nowhere to hide if you’re wrong.

His father later captured the mindset behind that choice in a simple reflection:

"In the early 1990s, when the company was facing a crisis, together with my son, I thought about 'what we could do if we were to start again from scratch and what we could do well'. At the time, I answered myself by saying, 'I am going to make cosmetics even if I am born again. Cosmetics is my dream and my life, in itself, and I will not be able to discover any meaning in life without cosmetics'."

The bet worked—spectacularly. From the mid-1990s to 2016, the company’s sales grew about tenfold, and operating profit climbed more than twentyfold. The crisis, which could have been the moment Pacific faded into history, instead became the moment Amorepacific was remade into a focused beauty machine.

But Kyung-bae Suh’s most consequential decision during the crisis wasn’t just what he cut. It was what he chose to build.

At a time when Asian beauty was still mostly taking cues from the West—especially French luxury—he pushed in the opposite direction. Amorepacific would lean into Korean heritage, not away from it. The company had been working with traditional Korean herbal medicine, or hanbang, for decades. A product called Sulwha had used natural Korean herbal ingredients to support and protect skin, and as the research deepened—into efficacy, processing, and formulation—that line evolved into Sulwhasoo in 1997.

This was counter-positioning with real risk. Korean consumers were increasingly drawn to imported prestige brands, and “local” didn’t automatically mean “premium.” Kyung-bae was betting that the opposite could become true—that Korean ingredients and Korean philosophy could one day command luxury pricing on the global stage.

The flagship proof point was ginseng. Amorepacific had been studying it since the 1960s. An early milestone came with the introduction of ABC Ginseng Cream in 1966, which the company describes as the world’s first ginseng-based cosmetic product and the beginning of the Sulwhasoo legacy. The research continued: in 1972, after years of work, Suh Sung-whan succeeded in extracting ginseng’s prized saponin from the plant’s leaves and flower, and the following year the company introduced Ginseng SAMMI with ginseng saponin as the key ingredient. Sulwhasoo would go on to build more than 50 years of ginseng research into its identity.

So in the middle of a financial meltdown, Kyung-bae Suh wasn’t just cleaning up a balance sheet. He was planting a flag: Korea wouldn’t simply manufacture beauty—it could define it.

Years later, the business world took note. In 2017, Harvard Business Review ranked Suh Kyung-bae #20 on its list of the ‘Best-Performing CEOs in the World 2017,’ placing him #2 among Asian CEOs and highest among leaders of global cosmetics giants.

IV. Innovation: The "iPhone Moment" of Cosmetics (2008)

Most beauty “innovation” is a remix: a new active ingredient, a new shade, a new face in a campaign. In 2008, Amorepacific did something rarer. It changed the format itself—the way liquid makeup and sun protection were carried, dispensed, and applied.

The pain was universal. Sunscreen and foundation felt heavy and looked cakey. Reapplying during the day was messy and impractical. Tubes and bottles leaked in handbags. Touch-ups demanded a mirror, time, and somewhere private.

In 2007, Amorepacific began R&D with a clear goal: build a multi-functional sun protection product that was easier to carry and apply than anything coming out of a conventional tube or pump bottle.

The breakthrough didn’t come from a lab bench. It came from an everyday object: a parking stamp. Press, stamp, done. An Amorepacific researcher noticed the mechanism and wondered—what if liquid cosmetics could work the same way? Instead of flowing and smearing, what if the product could be held in place, ready to be “stamped” onto skin in a controlled layer?

That simple observation kicked off an unglamorous, brutal process of iteration. The company says it ran more than 3,600 tests across 200 sponge types—everything from latex used in bedding to bath-sponge materials. This wasn’t a packaging tweak. It was engineering.

In March 2008, Amorepacific launched the result: IOPE Air Cushion, the original cushion compact.

It looked almost too simple to be disruptive: a compact with a specially designed sponge saturated with liquid foundation, sunscreen, and skincare ingredients. You pressed a puff onto the sponge and tapped the product onto your face—fast, portable, clean. Under the hood, the key was controlling liquid so it behaved like a solid: fluid trapped inside a micro-structured sponge, designed for consistent pickup and even application.

The market response made it clear this wasn’t just a clever gadget. IOPE Air Cushion became a global hit, with more than 140 million units sold from 2008 to 2017. In 2014, the company said one cushion product was sold every 1.2 seconds, and sales passed 200 billion KRW that year—turning a single item into one of the Korean cosmetics market’s defining blockbusters.

But the clearest signal that something had shifted wasn’t the sales. It was who came calling.

In 2015, Amorepacific signed an MoU to transfer its advanced cushion technology to Parfums Christian Dior, part of LVMH—the center of gravity of French luxury. Amorepacific also filed extensively around the innovation, applying for 114 patents and registering 13 across major markets including China, Japan, Europe, the U.S., and Korea.

This was the moment Korea stopped being seen as a fast follower in beauty and started acting like a platform the rest of the world built on. When LVMH is licensing cosmetic delivery tech from Seoul, the direction of influence has flipped.

V. The Golden Era: Riding the Hallyu Wave (2010–2016)

If the cushion compact was Amorepacific’s breakthrough product, the Hallyu Wave—the global surge of Korean pop culture—was its rocket fuel.

In the early 2010s, something clicked that hadn’t before: K-Pop, K-dramas, and Korean beauty stopped being “regional hits” and became exportable obsession. Groups like Girls’ Generation and BTS were turning fandom into a global language. Korean dramas spread across Asia and then outward through streaming. And wherever the Korean Wave landed, it carried the same quiet question: how do these stars look so flawless?

One show, in particular, turned that question into a buying frenzy. My Love from the Star, which aired in 2013–2014, didn’t just pull massive audiences—it shaped behavior. It sparked a craze for “chimaek” (fried chicken and beer), and it sent fashion and makeup items worn by lead actress Jun Ji-hyun into what observers described as an unprecedented surge in orders.

Amorepacific was right in the middle of it. The company spent heavily to promote its brands, including Hanyul, which Jun advertised, and it served as an official sponsor of the series. This wasn’t subtle brand building; it was culture moving product at internet speed, before TikTok was even the main stage.

Then came the China effect—an amplifier unlike anything global beauty had seen in years.

Before THAAD, Chinese tourists accounted for roughly 47% of total arrivals to South Korea, and they drove an estimated 70–80% of the country’s duty-free sales in 2016. These weren’t casual shoppers. Many came to Korea specifically to load up on Korean cosmetics—especially Amorepacific—and the daigou phenomenon poured gasoline on the fire. Resellers would buy in bulk in Seoul and flip the products back home at a premium. The result was surreal: queues curling around department store blocks, not for luxury leather goods, but for skincare sets and compacts.

Amorepacific built brands perfectly suited to that moment. Innisfree—marketed as accessible “natural beauty from Jeju Island”—scaled rapidly in mainland China. At its peak, it operated around 600 stores there, turning what looked like a lifestyle concept into a retail land grab.

The growth curve was dizzying. By 2016, Amorepacific’s overseas sales reached KRW 1.6968 trillion—about 181 times what it had exported in 1996. The accolades followed: Suh Kyung-bae was named Forbes Asia’s 2015 Businessman of the Year, and the company rose to become the world’s 7th largest beauty company by sales, according to Women’s Wear Daily.

Inside Korea, the market treated Amorepacific like a national champion with unlimited runway. The stock surged. Suh Kyung-bae’s net worth briefly made him the second-richest person in the country. From the outside, it looked unstoppable: a category-defining innovation, perfect timing with pop culture, and a seemingly endless pipeline of Chinese demand.

But the foundations were more brittle than they looked. The overseas boom leaned heavily on Chinese tourism, on a duty-free channel concentrated in a handful of locations, and on offline retail—right as consumer behavior was migrating online.

The question nobody wanted to ask in the middle of the party was the only one that mattered: what happens when any one of those pillars gives way?

VI. The Crash: Geopolitics & The Channel Shift (2017–2020)

In July 2016, South Korea and the United States made a security decision that would end up detonating one of Amorepacific’s biggest growth engines: they announced the deployment of the U.S. Terminal High Altitude Area Defense system, or THAAD, to help defend against North Korean missiles.

Beijing saw THAAD differently. China viewed it as a regional security threat aimed less at North Korea and more at China itself—and responded the way it often does when it wants leverage without declaring a formal sanction: through pressure that’s unofficial, but unmistakable.

For Amorepacific, the retaliation had a very specific shape. It hit tourism.

China imposed what was widely described as an “informal” ban on Korean package tours. Reportedly, representatives from China’s tourism authorities issued verbal instructions to cancel group tours after March 15, 2017, warning travel agencies that noncompliance could mean fines or even license revocation. The effect was immediate. Chinese group travel dried up, and tourist arrivals fell sharply in 2017—down 48.3%, or more than 4.5 million visitors.

If you were a Korean airline or hotel chain, that was brutal. If you were Amorepacific—whose international profit machine was heavily tied to Chinese tourists stocking up on products in Korean duty-free shops—it was closer to an extinction-level event.

The numbers told the story fast. In the second quarter of 2017, the company reported sales down 17.8% to about $1.26 billion, with profit falling 57.9% to roughly $116 million. The company had built a system that converted foot traffic into cash. Suddenly, the feet stopped coming.

But THAAD was only the first удар. While geopolitics was strangling the duty-free funnel, China’s beauty market was changing underneath Amorepacific’s entire strategy.

Amorepacific’s model in China had been built for an earlier era: department store counters, branded road-shop storefronts, and offline retail presence. It was the exact wrong setup as Chinese consumers migrated to mobile-first commerce and discovery. During the pandemic, that offline-heavy posture took an even harder hit, and the company’s reliance on duty-free only deepened the pain. At the same time, Chinese shoppers increasingly shifted toward lower-priced homegrown products—often close cousins of the very Korean formulas they once imported.

This was the moment C-Beauty stopped being a talking point and became an existential threat.

Perfect Diary became the symbol of the new playbook. Founded in 2017 under Yatsen Holding, it targeted women in their 20s and 30s and went digital-first from day one: flagship stores on Taobao and Tmall, then a rapid build-out across RedNote (Xiaohongshu), WeChat, and pop-ups in Shanghai. By the 2018 Double 11 festival, the brand generated more than RMB 100 million in sales in just 90 minutes. In 2020, it was winning awards at the Tmall Golden Makeup Awards.

Brands like Perfect Diary had effectively cloned “affordable Korean beauty”—the lane Innisfree helped define—but they ran it on China’s native platforms, at China speed, and with the algorithms as their distribution.

Meanwhile, the old offline map started to collapse. The Face Shop exited China and shuttered more than 300 stores. Skin Food withdrew from a number of department store locations. And Innisfree, after its annual operating profit fell 90% in 2020, closed 80% of its physical branches in China in early 2021.

Amorepacific found itself stuck in a classic innovator’s dilemma, except this time it wasn’t about a new product format. It was about channels. The company had invested heavily in physical retail—flagships, counters, leases—right as the center of gravity moved to social commerce. It couldn’t pivot overnight. Long-term commitments kept it anchored while newer competitors stayed weightless, living inside Douyin feeds and Xiaohongshu posts.

The conclusion was as painful as it was obvious: Amorepacific had become over-exposed to one market, and that market had turned hostile on three fronts at once—politics, competition, and consumer behavior.

VII. The Pivot: North America & The COSRX Acquisition (2021–Present)

Amorepacific’s response to the China shock became the defining project of the Suh Kyung-bae era: “global rebalancing.” Strip away the corporate phrasing and the meaning is simple: stop living and dying by China, and build a business that can win in the West.

The first real proof point didn’t come from a prestige counter or a heritage story. It came from a small jar that American teenagers kept holding up to their cameras.

Laneige turned into one of those rare beauty brands that’s synonymous with a single hero product: the Lip Sleeping Mask. The mask—and the broader lip balm franchise—showed up everywhere: Sephora gift sets, “night routine” videos, and endless TikTok recommendations. The rest of the line benefited from the halo, but the lip product did the heavy lifting.

More importantly, it signaled something Amorepacific desperately needed to see: K-Beauty could break through in the U.S. on its own terms, not just as a side effect of K-Pop fandom. Laneige, positioned by Amorepacific as a hydration-focused brand built on “Advanced Water Science,” became one of the group’s clearest Western growth engines. In the U.S., it ranked among the top three skincare brands at Sephora in 2024—an indication that this wasn’t just viral noise; it was strong retail execution and repeat demand.

But the most consequential move of the pivot wasn’t an organic hit. It was an acquisition—and, in a way, an admission.

Amorepacific’s purchase of COSRX effectively acknowledged that its legacy machine—big R&D, department store distribution, traditional brand-building—couldn’t reliably produce a certain kind of modern winner. So instead of trying to rebuild those muscles from scratch, it went shopping for them.

In 2023, Amorepacific secured a majority stake in COSRX, investing more than 900 billion won in what it described as the largest brand purchase in company history. It later announced plans to acquire the remaining 288,000 shares from COSRX’s largest shareholder and related parties for 755.1 billion won (about $567.3 million at the time).

COSRX was almost a mirror image of the traditional Amorepacific playbook: digital-first, minimalist branding, and deeply fluent in the way Western consumers actually discover skincare today. Long before it was a household name in Korea, it was already beloved abroad—built through Reddit threads, skincare forums, TikTok reviews, and the unglamorous mechanics of Amazon search.

After entering Amazon in 2018, products like the Advanced Snail 96 Mucin Power Essence rose to the top of Beauty and Personal Care, especially in North America. COSRX posted an average annual sales growth rate of more than 60% over the prior three years and reported ₩204.4 billion (about $150.7 million) in 2022. Amorepacific described it as having “experienced rapid growth, establishing itself as a rising global skin care titan.” It expanded to around 140 countries, with overseas sales making up over 90% of its total.

The logic was clear: Amorepacific’s flagship brands—Sulwhasoo, Laneige, Innisfree—were built in an era of department store counters, door-to-door relationships, and K-drama product placements. COSRX was built in an era of algorithmic discovery. Those are different muscles, and Amorepacific decided to buy rather than build.

At the same time, the company worked to reset Sulwhasoo’s image for global luxury. Sulwhasoo announced the appointment of Tilda Swinton as a global ambassador. BLACKPINK’s Rosé, who began her role as a global ambassador in September 2022, also became part of that push, helping the brand present itself as both heritage-rich and culturally current. Sulwhasoo also entered a year-long partnership with The Met to support museum programs and activities aimed at expanding how audiences engage with and celebrate global heritage.

Financially, the early results suggested the rebalancing was gaining traction. Amorepacific Group recorded sales of KRW 4.2599 trillion and operating profit of KRW 249.3 billion in 2024. Sales rose 5.9% year-on-year, and operating profit increased 64.0%, driven by stronger performance in global markets—particularly Western regions.

In the Americas, sales increased 83%, powered by brands like Laneige, which maintained its leadership in the lip treatment category, along with the effects of COSRX integration. In EMEA, overall sales tripled, with Laneige posting triple-digit growth as it expanded into channels like the UK’s Boots and ASOS—again supported by COSRX’s contribution.

But the pivot isn’t risk-free, and the COSRX bet comes with its own volatility. COSRX’s performance softened as competition intensified. In the second quarter of this year, it posted sales of 96.7 billion won and operating profit of 24.2 billion won, down 0.3% and 17% year-over-year. The decline had persisted since the latter half of 2024, reflecting an increasingly crowded U.S. market where new indie skincare brands keep chipping away at yesterday’s breakout hits.

In other words, the same forces that made COSRX possible—low barriers to entry, fast-turn ODM manufacturing, and the ruthless efficiency of social-driven discovery—also make it easier for the next brand to copy the playbook and steal the spotlight.

VIII. Analysis: The 7 Powers & Strategy

So what do you see when you step back from the product launches and the geopolitics and run Amorepacific through a few classic strategy lenses? A company with real, durable strengths—paired with weaknesses that the modern beauty market punishes fast.

Hamilton's 7 Powers Analysis

Brand: Sulwhasoo is the clearest example of true counter-positioning in the portfolio. While Western luxury skincare leans on lab-coat science and French heritage, Sulwhasoo leans into hanbang (traditional Korean herbal medicine) and decades of ginseng research. Its anti-aging cream is positioned as the culmination of more than 60 years of ginseng work, with roots tracing back to ABC Ginseng Cream in 1966. That kind of origin story isn’t a tagline—it’s an identity, and it’s hard for L’Oréal or Estée Lauder to replicate credibly. The flip side is that the mid-market brands—especially Innisfree and Etude—have seen their equity fade, particularly as C-Beauty competitors offer similar “clean/natural/value” promises at lower prices and with faster trend cycles.

Process Power: The cushion compact was process power in its purest form: a proprietary breakthrough that created a new category and changed consumer behavior. By October 2016, Amorepacific’s cushion compacts had reached 100 million units sold, supported by a large patent portfolio—177 patent applications and 26 registered patents as of that same date. But the advantage didn’t last. Cushions are now everywhere, and with licensing and widespread imitation, the format no longer functions as a moat. What was once a wedge is now table stakes.

Scale Economies: Amorepacific still enjoys meaningful scale in Korea—in R&D, manufacturing, and the operational muscle to develop and produce at volume. It allocates more than 2% of sales to R&D, reinforcing the company’s longstanding bias toward innovation. The harder question is whether that kind of scale converts into an advantage in the U.S. and Europe, where distribution and marketing—Sephora relationships, influencer ecosystems, paid social efficiency—matter more than how large your domestic production footprint is. In the West, Amorepacific is still the challenger.

Porter's 5 Forces Analysis

Threat of New Entrants (High): Beauty has become one of the easiest consumer categories to enter. Korean ODMs like Cosmax and Kolmar have lowered the barrier to “good enough” product quality to the point where speed and storytelling can matter more than incumbency. A TikTok-native founder with a sharp point of view can spin up something that competes with Innisfree in months, not years.

Competitive Rivalry (Intense): At home, Olive Young—the “Sephora of Korea”—has become the gatekeeper, and Amorepacific has to fight for visibility against nimble indie brands that are built for the shelf and the feed. Abroad, the battlefield is even more crowded: global giants like L’Oréal, Estée Lauder, and Shiseido, plus increasingly sophisticated C-Beauty players, all competing for the same customers with enormous budgets and strong channel leverage.

Buyer Power (High): Modern beauty consumers switch fast and feel no guilt about it. Social platforms compress the distance between discovery and purchase, and they also compress loyalty. One viral review can crown a product; the next one can quietly replace it.

Supplier Power (Moderate): The company’s vertical integration helps—proprietary green tea farms on Jeju Island and ginseng cultivation provide some insulation on key ingredients. But Amorepacific still relies on ODM partners for certain production needs, which limits how fully insulated it can be.

Threat of Substitutes (Moderate): The rise of “skinimalism,” and a broader skepticism about long, multi-step routines, isn’t a direct substitute for skincare—but it challenges one of K-Beauty’s most exportable habits: layering and accumulation. Fewer steps can mean fewer products.

The Innovator's Dilemma

The strategic tension tying all of this together is a classic innovator’s dilemma: how do you fully embrace digital and DTC without collapsing the legacy channels—door-to-door, department stores, duty-free—that still generate meaningful revenue and support a huge ecosystem of people?

The door-to-door channel is the most symbolic. What began as Amorepacific’s cornered resource has become a legacy weight. The Amore Ladies who built the company are aging, and younger Korean women largely don’t want to sell cosmetics that way—or buy them that way.

Meanwhile, the home market is no longer the engine. In 2024, Amorepacific’s Korean business posted sales of KRW 2.1570 trillion, down 2.4% year-on-year. Domestic demand is mature and slightly shrinking. The growth is elsewhere—and it’s digital.

IX. Bear vs. Bull: The Verdict

The Bear Case

China is still the falling knife. For all the talk of “global rebalancing,” Greater China remained the single biggest country exposure—and it was still moving the wrong way. Revenue in Greater China fell 27% to KRW 510bn (about USD 351.6m). When you combine lingering geopolitical tension from the THAAD era with sharper C-Beauty competition and too much retail capacity chasing too few shoppers, a clean rebound is hard to underwrite.

Korea isn’t going to bail them out. South Korea’s birth rate has fallen to the lowest in the world, and the broader fear—“Japanification,” the slow grind of demographic decline—puts a ceiling on domestic beauty growth. Even if Amorepacific executes well at home, “home” may simply be a smaller prize over time.

Speed is the new moat, and it’s not Amorepacific’s native terrain. C-Beauty brands have benefited from a shift toward domestic pride, cultural fluency, and brutally fast manufacturing cycles. Some can launch new product lines in as little as three months. That’s a very different game from an 80-year-old heritage company built on formalized R&D processes and slower, more deliberate brand-building. The uncomfortable question is whether Amorepacific can move at internet pace without breaking what makes it Amorepacific.

And even the West-facing answer—COSRX—has shown early stress. While the acquisition made strategic sense, competition in online skincare is relentless, and COSRX has cut prices across online channels to reduce inventory. That can protect volume, but it also squeezes margins—exactly where you want operating leverage to show up.

The Bull Case

The rebalancing isn’t a slide deck anymore; it’s showing up in the mix. The Americas surpassed Greater China to become the group’s largest global market by revenue for the first time in its history. In the Americas, sales rose 83%. That’s not just “diversification.” That’s the company proving it can win on the world’s hardest beauty turf.

K-Culture looks less like a trend and more like a new baseline. Korean music, film, and television have become permanent fixtures in global pop culture, and that cultural credibility gives K-Beauty something rare: authenticity that translates. It’s a tailwind that’s difficult for Japanese incumbents and Chinese upstarts to replicate in the same way.

Sulwhasoo also has real Estée Lauder-style potential as a global heritage luxury brand—because its story isn’t manufactured. The hanbang philosophy, the depth of ginseng research, the cultural roots: those are assets that can’t be bought. Its #1 anti-aging cream has been a bestseller for more than 20 years since launching in 2000, and the lineage runs back to ABC Ginseng Cream in 1966—positioning it as the culmination of more than 60 years of ginseng research and modern formulation technology.

Finally, Amorepacific is explicitly trying to retool for what comes next. It laid out five strategic priorities: focusing on key global markets (Everyone Global), strengthening integrated beauty solutions (Holistic), developing biotech-based anti-aging solutions (Ageless), driving agile organizational innovation (AMORE Spark), and shifting toward AI-driven operations (AI First). The point isn’t the labels—it’s the acknowledgment that the future advantage won’t come from being big in Korea. It will come from being fast, digital, and globally relevant.

And the market is no longer pricing in a happy ending. The stock has de-rated substantially from the 2016 peak, pushing valuation to historic lows—meaning a lot of bad news is already embedded.

Key KPIs to Watch

If you want to track whether this pivot is actually working, two metrics matter more than everything else:

-

Western Region Revenue Growth Rate (Americas + EMEA): This is the clearest read on whether “global rebalancing” is real. Sustained double-digit growth would show that Amorepacific can grow in the West on its own—without relying on Chinese tourism or duty-free demand.

-

China Segment Operating Profit/Loss: China has acted like a cash incinerator for years. Whether it returns to normalized profitability—or whether management chooses a deliberate pullback—will determine if the segment remains an anchor or becomes merely a smaller, manageable business.

X. Epilogue & Lessons

Amorepacific’s eighty-year run reads like a masterclass in how consumer empires are built—and how they get humbled.

The first lesson is the danger of “easy growth.” The China boom didn’t just lift results; it covered up structural risk. Duty-free was wildly profitable, but it was also brittle. When your best channel depends on tourism flows and geopolitical goodwill—things you don’t control—the vulnerability won’t show up in a quarterly report. It shows up all at once, the day the foot traffic disappears.

The second lesson: heritage is an asset in luxury, and a liability in mass market. For Sulwhasoo, the decades-long ginseng and hanbang story is real differentiation. It can support premium pricing because it’s hard to fake credibility at that level. But for Innisfree and Etude, “Korean-ness” doesn’t protect you. In the mid and lower tiers, competitors can copy your look, borrow your language, and beat you on speed and price. Authenticity becomes a commodity faster than you’d like.

Third: distribution moats decay faster than brand moats. The Amore Ladies network was once the company’s secret weapon—a relationship-driven channel competitors couldn’t replicate. Over time, it became something else: a legacy structure built for a world that moved on. Channels change. Habits change. And what once powered growth can turn into drag.

Which brings us to the question hanging over the whole story: can an 80-year-old company learn to speak Gen Z?

Suh Kyung-bae put it in his anniversary address like a promise and a challenge: “Over the past 80 years, Amorepacific has navigated turbulent times, driving the growth of Korea's beauty industry and the globalization of K-beauty. We will continue to listen to our customers and present our vision of 'New Beauty,' introducing new forms and expressions of beauty befitting the times.”

The company that began with Yun Dok-jeong pressing camellia oil by hand in a Kaesong kitchen has already reinvented itself more than once—shop to network, network to brands, brands to a global phenomenon. Now it’s trying to do it again, in a world where discovery happens in feeds, loyalty lasts a week, and trends outrun product cycles.

If it works, Amorepacific may yet become the Asian L’Oréal its scale and ambition suggest. If it doesn’t, it won’t be for lack of history—it’ll be because history, by itself, doesn’t win on the internet.

The face of K-Beauty is still being written.

Chat with

this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with

this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music