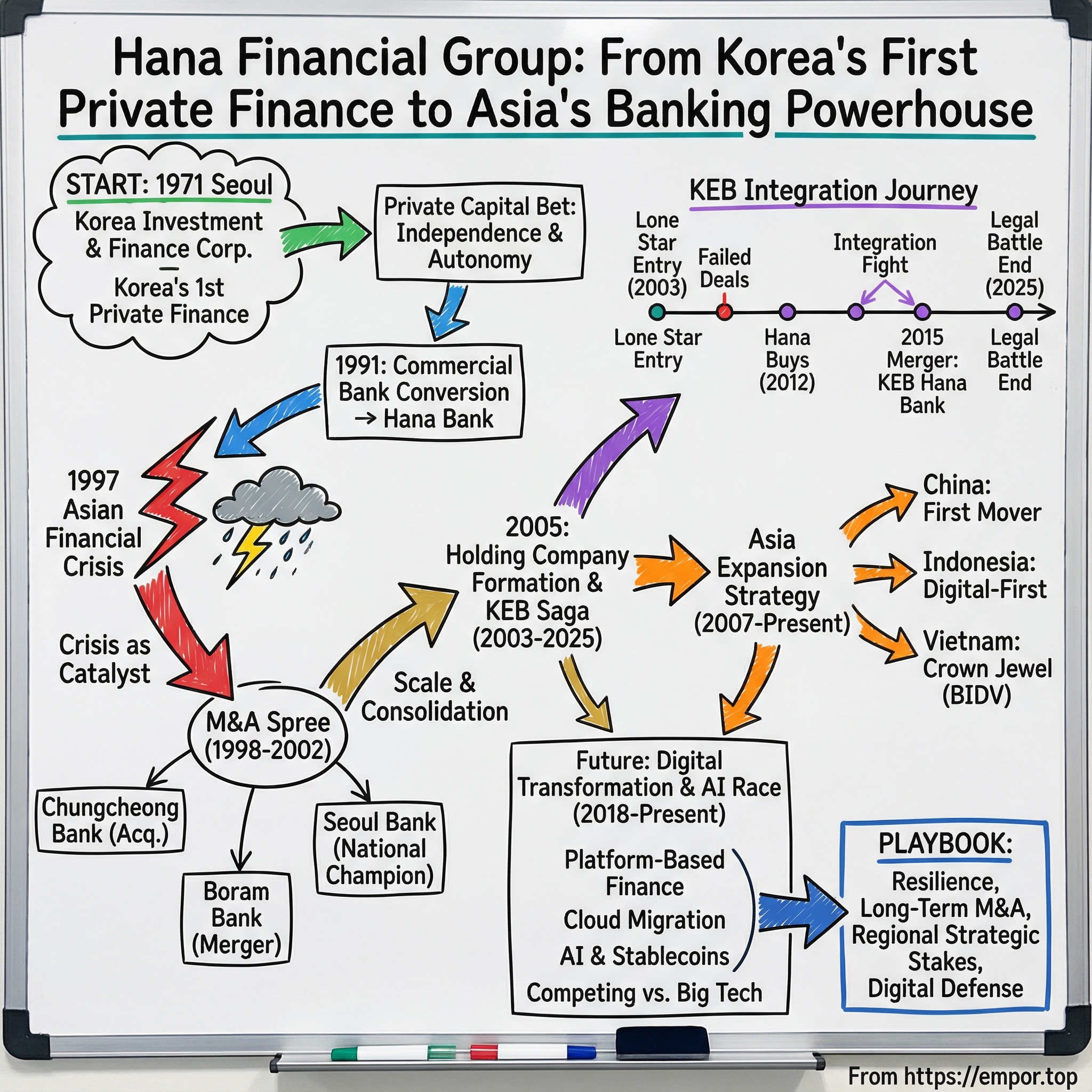

Hana Financial Group: From Korea's First Private Finance Company to Asia's Banking Powerhouse

I. Introduction: The Unlikely Champion

Picture Seoul in December 1971. The Korean War was still within living memory. President Park Chung-hee’s government was in the middle of what would later be called the “Miracle on the Han River” — a state-driven sprint from poverty to industrial power. The chaebols were gearing up to build ships, steel, and eventually semiconductors, fueled by government-guided credit.

And then, almost off to the side of that national project, something quietly radical happened.

A small group — 26 individuals — started a financial company using only private capital. No state backstop. No policy mandate. Just a bet that there was room in Korea’s tightly controlled financial system for an institution that answered to its customers and shareholders, not to the government’s industrial plan.

That company was Korea Investment & Finance Corporation. It opened in 1971 as a short-term finance company, focused on investment and financing services, with just two branches in Seoul. Korea’s first financial company funded solely with private capital wasn’t supposed to become a national champion. But from day one, it carried a different posture: independence, autonomy, and an entrepreneurial streak that stood out in an industry designed to be an extension of the state.

At the time, the contrast was stark. Most meaningful financial institutions operated under the government’s guiding hand — channels for policy-directed lending to preferred industries. Korea Investment & Finance didn’t fit neatly into that world. Its founding marked a real entry point for private-sector initiative in Korean finance.

Fast forward to today, and that two-branch experiment has scaled into something almost unrecognizable. As of the third quarter of 2025, Hana Financial Group reported total assets of 659 trillion won, putting it among South Korea’s largest financial institutions. Its subsidiaries operate in 24 countries across Asia, the Americas, Europe, and the Middle East. The arc of growth is breathtaking: from two branches in 1971 to 1,122 today; from 1.5 trillion won in assets when it became a commercial bank in 1991 to 815 trillion won by December 2024.

But the numbers aren’t the plot. They’re the scorecard.

The real story is how Hana kept finding leverage points when the world around it shifted: using crisis as a catalyst, executing acquisitions that sparked national outrage and years-long legal fallout, and then racing into digital transformation as Big Tech and digital-only banks started circling the industry’s profits. All of it powered by something rare in Korean banking: Hana Bank stayed profitable for decades and continued paying dividends — the longest such run in the country.

So here’s the question we’re really answering: how did a tiny private finance company with two branches in 1971 become one of Asia’s most successful financial groups — and what does Hana’s playbook teach us about surviving shocks, making M&A work when it takes years, and competing when the battlefield shifts from branches to apps?

II. Founding Context: Korea's First Private Finance Pioneer (1971–1991)

The Birth of an Outsider

To understand what made Korea Investment & Finance Corporation remarkable, start with what it wasn’t.

It wasn’t a government policy tool. It wasn’t a chaebol affiliate. It wasn’t built to funnel subsidized credit into shipyards, steel mills, or whichever industry the state was pushing that year.

It was launched in 1971 as Korea’s first financial company funded solely with private capital, and it carried itself like an outsider. The company’s posture was entrepreneurial and unusually independent for its time, with transparent management that reflected its shareholder base. In a system where finance often moved in lockstep with government direction, Korea Investment & Finance tried to prove a different idea: that a private institution could stand on its own, compete, and still earn trust.

That phrase “strong independence from the government” matters. In Park Chung-hee’s Korea, the financial system was a lever of industrial policy. Banks weren’t just intermediaries; they were mechanisms for executing a national plan. Against that backdrop, a purely private finance company succeeding wasn’t just unlikely—it was borderline provocative.

Part of the strategy was structural. Instead of fighting for a full banking license, the founders operated as a short-term finance company—essentially a money market brokerage. That choice offered more room to maneuver and kept the company a step removed from the most direct forms of credit allocation control that shaped commercial banking.

Then came the quiet compounding: credibility, relationships, and product innovation aimed at customers who cared less about hype and more about control. In 1984, the company introduced the first corporate customer exclusive system in Korea and the country’s first CMA (Cash Management Account). These were tools for corporate treasury management—ways for businesses to manage cash and liquidity more intelligently.

And the market responded. By 1988, deposit balances had climbed past 1 trillion won, a milestone that did more than pad a balance sheet. It validated the premise that private capital could build a serious financial institution inside a landscape designed to favor state-directed incumbents.

The Transformation to Commercial Bank

By 1991, the ground was shifting. Korea was opening up—politically, economically, and financially. The government began loosening its grip on the sector, and that created a window Korea Investment & Finance couldn’t ignore.

Originally founded in 1971 as Korea Investment & Finance, a money market brokerage, the company converted into a commercial bank in 1991 and was renamed as Hana Bank.

That move wasn’t cosmetic. It was a full business-model upgrade—from specialized short-term finance into full-service commercial banking. Hana was stepping onto a bigger field, with bigger competitors, bigger regulatory scrutiny, and much bigger upside.

The bank framed the moment the way it always had: change wasn’t a threat if you could turn it into leverage. After the conversion, Hana Bank sought to transform the risks of a rapidly evolving economy and financial system into fuel for growth—leaning on entrepreneurship, prioritizing customers, and building for what came next.

And what came next was the 1990s: a decade that would reward Korean banks with huge growth, and then punish them with one of the most violent financial shocks the region had ever seen.

Hana was about to find out whether its outsider DNA—discipline, independence, and a bias toward resilience—was a nice story, or a real competitive advantage.

III. Inflection Point #1: The Asian Financial Crisis & Consolidation Wave (1997–2005)

The Apocalypse on the Han

December 1997 is seared into Korea’s national memory. The won collapsed, sliding from roughly 800 to the dollar to nearly 2,000. The IMF arrived with a $58 billion rescue package—and with it, a kind of national humiliation: strict conditions, forced restructuring, and a financial system that suddenly had to become something it hadn’t been built to be.

The government opened the gates to foreign capital, lifting the ceiling on foreign investment in Korean companies from 26 percent to 100 percent. It also launched a sweeping reform program that, by June 2003, had shut down or merged hundreds of insolvent financial institutions.

The damage was brutal and immediate. In 1998 alone, five of the 26 commercial banks that existed at the outbreak of the crisis were liquidated, along with 16 merchant banks and other failing institutions. Another set of banks survived only by being absorbed into stronger ones, often with government support.

This didn’t stay contained inside balance sheets. Bankruptcies rippled across the economy, from small businesses to household names. Even giants like Samsung and Hyundai tightened belts. Unemployment surged: the number of jobless Koreans nearly tripled from late 1997 into 1998, and the unemployment rate jumped from 2.6 percent to 6.8 percent.

For most Korean banks, this was an extinction event.

For Hana, it was an opening.

Crisis as Catalyst

Hana went into the storm in better shape than many of its peers. It had avoided some of the worst excesses of the boom years, and that discipline—rooted in its origins as a privately funded outsider—suddenly mattered a lot.

So while competitors were drowning in bad loans and being pushed into government-led restructurings, Hana started shopping.

In 1998, Hana acquired Chungcheong Bank, a regional institution regulators had deemed insolvent, and rebranded it as Chungcheong Hana Bank. This was Hana’s first major acquisition, and it sent a clear signal: Hana wasn’t waiting to be rescued. It was using the crisis to expand.

A year later, the pace picked up. In 1999, Hana merged with Boram Bank in a voluntary deal between two privately held institutions. The result was a stronger combined player with about 41 trillion won in assets—still not the biggest, but no longer easy to ignore.

And then came the deal that changed Hana’s trajectory for good.

The Seoul Bank Merger: Becoming a National Champion

In August 2002, it was announced that Seoul Bank—once one of Korea’s largest banks, later declared insolvent and taken into government ownership in December 1997—would be merged with Hana. Hana had been selected through a competitive bidding process, beating out Lone Star Funds. The merger closed in December 2002.

This wasn’t a tidy bolt-on acquisition. Seoul Bank had real scale and a real history. Absorbing it meant Hana was no longer building branch by branch—it was vaulting into the top tier.

After the merger, the combined bank held roughly 83 trillion won in assets, making Hana the third-largest bank in South Korea at the time, behind Kookmin Bank and Woori Bank. In one stroke, Hana went from ambitious mid-tier contender to national champion.

The Holding Company Transformation

By 2005, Hana’s ambition had outgrown the idea of being “just a bank.” Korea’s financial sector was moving toward integrated groups that could offer customers banking, securities, insurance, asset management, and more—coordinated under a single strategic roof.

Hana’s answer was structural. In 2005, Hana Bank was delisted and reorganized as a subsidiary under a new holding company: Hana Financial Group. That same year, the group acquired Daehan Investment and Securities, then Korea’s second-largest asset management company.

Hana Financial Group launched in December 2005 with a straightforward premise: a broader product set, tighter coordination across subsidiaries, and more synergy than a standalone bank could produce. The crisis-era acquisitions had given Hana scale. The holding company gave it a platform.

And with that platform in place, Hana was ready for the next leap—one that would drag it into the most controversial deal in Korean banking history.

IV. Inflection Point #2: The Korea Exchange Bank Saga — The Most Controversial Deal in Korean Banking History (2003–2025)

Lone Star's Arrival: A Controversial Beginning

To understand the KEB saga, you first have to understand what Korea Exchange Bank was.

KEB was founded in 1967 as a government-owned bank built for one job: foreign exchange. Over time, it broadened out. In 1975 it entered securities. In 1978 it launched Korea’s first credit card service. It even played a public, national role—serving as the official sponsor bank for the 1986 Asian Games and the 1988 Seoul Olympics.

But by the time the 1997 crisis hit, the shine didn’t matter. KEB had been partially privatized, yet it was still in trouble. It was Korea’s fifth-largest bank, strong in foreign exchange, and weak where it counted most: its balance sheet.

That’s when Lone Star Funds showed up—a Dallas-based private equity firm known for buying distressed assets at steep discounts. In 2003, it acquired a 51% stake in the distressed KEB for about 1.3834 trillion won.

And the controversy started immediately.

Under Korea’s Banking Act, a non-financial business operator wasn’t supposed to acquire a bank unless the bank’s BIS capital ratio was below 8%. KEB’s president, Kang-won Lee, submitted a report assessing KEB’s BIS ratio at 6.16% as of July 25, 2003. On the strength of that report, the Financial Supervisory Service approved the acquisition.

Then came the part that turned suspicion into outrage. KEB’s stock price rose after the deal, and Lone Star recorded roughly $1 billion in appraisal profit within three months. To many Koreans, the message was obvious: KEB must have been sold too cheaply—maybe deliberately—so a foreign “corporate raider” could walk away with a windfall.

Scrutiny intensified around whether Lone Star was even eligible to own the bank. Industrial capital was barred from acquiring domestic banks, and Lone Star held industrial-capital affiliates in Japan, including golf courses and wedding halls. Authorities still approved the deal, citing the special grounds of resolving an insolvent financial institution. By 2004, the “fire sale” controversy had become a full-blown national story.

The Failed Sales & HSBC Drama

Lone Star’s entry may have been swift. Its exit was anything but.

In November 2006, Lone Star pulled out of a $7.4 billion contract to sell a controlling stake in KEB to Kookmin Bank. The backdrop wasn’t market conditions—it was the growing cloud of investigations into whether the 2003 approval had been improper.

In September 2007, Lone Star tried again. HSBC announced an agreement to buy a 51% stake in KEB for $6.31 billion. But the deal couldn’t get out of its own way. The South Korean government said it couldn’t approve the sale until court rulings were issued on the alleged “fire sale” of KEB. Then the global financial crisis hit. Asset values were falling, risk appetite disappeared, and in September 2008 HSBC terminated the deal.

That collapse—part politics, part law, part terrible timing—became the core grievance in a legal fight that would drag on for more than a decade.

Hana's Bold Move

By 2010, the situation had become untenable. Lone Star had owned KEB for seven years—an eternity in private equity—and the regulatory morass wasn’t clearing.

In November 2010, Hana Financial Group signed a contract with Lone Star to buy its KEB stake for 3.9 trillion won. Even then, nothing happened quickly. The transaction took more than a year to close, and on February 9, 2012, Lone Star sold KEB to Hana Financial Group in the wake of a guilty verdict in the Korea Exchange Bank Credit Service stock manipulation case.

In 2012, Hana ultimately acquired a 51.02% stake in KEB from Lone Star Funds for 2.02 trillion won. But buying the stake was only the beginning. Opposition from the KEB labor union delayed a full merger until 2015, leaving Hana Bank and KEB to operate as separate banks under the same holding company.

Integration: A Three-Year Ordeal

Hana now owned KEB, but it didn’t control the outcome it wanted: a single, unified bank.

The KEB labor union fiercely opposed a merger, worried about layoffs and the loss of KEB’s identity. Meanwhile, Hana’s management argued the “two-bank system” created inefficiencies and threatened long-term competitiveness. The fight escalated.

In January 2015, Hana Financial Group moved to merge Hana Bank and KEB early, explicitly citing “serious management inefficiencies.” The union responded with an injunction to stop the merger, and the court initially accepted it. Hana objected. On June 26, the court accepted Hana’s objection and overturned the injunction. A few weeks later, on July 13, the union and Hana reached an agreement on early integration through negotiations.

On September 1, 2015, Hana Bank and Korea Exchange Bank officially merged into KEB Hana Bank, ending KEB’s 48-year history since its establishment in 1967. At the time, the combined bank became Korea’s largest by total assets, reaching $243 billion in 2015.

The 13-Year International Legal Battle

Even that wasn’t the end.

In 2012, Lone Star filed a $4.67 billion ISDS claim against the Korean government. The allegation: regulators had delayed approval of the planned 2007 sale of KEB to HSBC, causing the deal to collapse, forcing Lone Star into a later sale at a lower price and creating losses.

What followed became one of the longest ICSID arbitration sagas on record: 3,508 days of proceedings, thousands of pages of submissions, nearly 100 witness and expert statements, and hearings in Washington and The Hague.

In August 2022, an ICSID tribunal partially upheld Lone Star’s claim and ordered Korea to pay $216.5 million—only a small fraction of what Lone Star sought.

Then both sides kept fighting. Lone Star pushed back, arguing the award was too small. The Korean government argued the tribunal had exceeded its authority.

In the end, South Korea prevailed. An international arbitration panel under the World Bank Group annulled the 2022 ruling that had ordered Korea to pay $216.5 million in damages, bringing the 13-year dispute to a close.

That kind of outcome is rare. ICSID data shows that among hundreds of rulings over decades, only a small number of annulment applications are accepted, and complete annulments are rarer still.

Justice Minister Jeong Seongho said, “With the recovery of these litigation costs, the legal dispute with Lone Star that has continued for about 13 years since 2012 has come to a close with a complete victory for the Republic of Korea government.”

Cultural Narrative: A National Trauma

The KEB saga didn’t stay inside courtrooms and balance sheets. In Korea, it became a symbol of economic sovereignty—who controls the country’s financial system, and what happens when foreign capital collides with national politics.

In November 2019, the film “Black Money,” a fictionalized depiction of Lone Star’s acquisition of KEB, was released, reflecting just how deeply the story had lodged in public consciousness.

The controversy was fueled by the sheer scale of the perceived payoff: Lone Star bought KEB in 2003 and sold it in 2012 to Hana Financial Group for 3.9 trillion won, earning 4.6 trillion won in profit. In the public narrative, it wasn’t just a trade—it was a wound.

For Hana Financial, the deal was both a transformation and a burden. KEB vaulted the group into the top spot by assets, but it also handed Hana years of integration conflict and reputational crossfire—problems that couldn’t be solved with a signature, only with time.

V. Inflection Point #3: The Asia Expansion Strategy (2007–Present)

China: First Mover in the Dragon Economy

While Hana was still wrestling with the KEB drama at home, it was also laying track abroad. The logic was simple: Korea’s financial market was competitive and mature. If Hana wanted a bigger future, it needed to earn it outside Korea.

China was one of the earliest bets. In 2007, Hana Financial Group established a local subsidiary, Hana Bank China. Two years later, in 2009, it received a license to handle renminbi transactions and debit card business—an important step for doing real banking in-country, not just representative-office networking. In 2010, Hana bought an 18.44% stake in Bank of Jilin. Then in January 2011, it entered a strategic alliance with China Merchants Bank.

What’s notable isn’t just the sequence—it’s the approach. Hana didn’t try to brute-force its way into Chinese retail banking with a giant branch rollout. Instead, it paired a smaller wholly owned presence with minority stakes and partnerships in local incumbents, a pragmatic way to navigate a market where foreign banks face heavy regulatory and competitive barriers.

Indonesia: Building Digital-First Presence

Indonesia was a different kind of play—less about regulatory chess, more about timing and adoption.

Hana acquired Bank Bintang Manunggal in 2007 and renamed it PT. Bank Hana in 2008. In 2014, its Indonesian subsidiary acquired Bank KEB Indonesia as part of the group’s broader global acquisition strategy. And in 2021, Hana took a step that signaled where it believed Indonesian banking was headed: it established LINE BANK by Hana Bank, a joint venture with LINE Financial Asia.

Indonesia’s appeal was straightforward: a huge, young population and a banking market where digital could scale faster than brick-and-mortar. The LINE partnership was Hana effectively saying, in an emerging market, the winning distribution channel might not be branches at all—it might be the platform people already live on.

Vietnam: The Crown Jewel

If China was the long game and Indonesia was the digital wedge, Vietnam became the headline.

On November 11, 2019 in Hanoi, BIDV announced Hana Bank as a strategic shareholder, with a 15% stake in the Vietnamese lender’s charter capital. It was widely described as Vietnam banking’s biggest strategic-investor M&A deal.

Hana acquired the stake by purchasing 603 million new shares for 1.01 trillion won, with approval from Vietnam’s central bank, which had held 95.28% of BIDV. BIDV, founded in 1957, had 66.3 trillion won in assets at the end of 2018—and, crucially, massive reach: roughly 1,000 branches and 58,000 ATMs.

This is why the deal mattered. Hana didn’t just buy equity; it bought instant distribution. A nationwide footprint that would take years—maybe decades—to build from scratch, delivered in one transaction.

It also created a clean division of labor. BIDV was strong in corporate finance, lending, and trade. Hana brought consumer-banking know-how. Since Hana’s 2019 investment, BIDV shifted its portfolio more toward consumer banking, leaning on Hana’s expertise. BIDV’s share price nearly doubled by mid-January 2022 compared with Hana’s purchase price. And over the first few years, BIDV’s personal-loan asset ratio rose from 32% to 38%, while net profit jumped by more than 40% in 2021.

The partnership didn’t stop at balance sheets. The two banks have continued expanding cooperation, including an agreement effective August 2025 aimed at broadening cross-border QR payment services—another indicator that Hana’s Vietnam bet wasn’t just about owning part of a bank. It was about plugging Hana into the financial rails of a fast-growing region.

VI. Inflection Point #4: The Digital Transformation Race (2018–Present)

The Existential Threat

If the Asian Financial Crisis was the moment Korean banking learned what a balance-sheet shock feels like, the late 2010s brought a different kind of threat: distribution.

South Korea is intensely competitive, deeply connected, and surprisingly unforgiving to incumbents that move slowly. The country has only a handful of digital-only banks, but they’ve punched far above their weight by going after exactly what traditional lenders struggled with: convenience, speed, and products that don’t require elite credit profiles or a relationship with a branch manager.

Kakao Bank, launched in July 2017, scaled fast—reaching more than 13 million users within a few years. By 2020, that meant over one in five Koreans had used it. And the money followed. By the third quarter of 2023, Kakao Bank held deposits north of 45 trillion won, with Toss Bank not far behind at nearly 23 trillion.

For Hana, this wasn’t an abstract “digital disruption” slide in a board deck. It showed up in the most painful places: daily usage and share. Hana’s flagship mobile app, Hana 1Q, sat at around 6.4 million monthly active users—roughly half the level of KB Kookmin Bank. And among the six major banks, Hana’s deposit share ranked fourth at 17.5% as of the end of March, according to the Financial Supervisory Service.

In a market where customers can switch banks with a few taps, being “fourth” doesn’t feel stable. It feels exposed.

Platform-Based Finance Vision

Hana’s response was to stop thinking of digital as “mobile banking,” and start treating it as the company’s operating system.

Instead of layering an app on top of a traditional bank, the group pushed toward a platform mindset: data-driven services, tighter integration across affiliates, and digital experiences that could compete with tech-native expectations.

Since 2021, Hana has expanded its digital footprint with products designed to blur the line between branch service and app convenience. One example is Hana Bank’s My Branch, a virtual banking service built to deliver customer-specific attention without requiring customers to actually walk into a branch. Hana positioned it as an offline-to-online transformation platform—and it scaled aggressively, with more than 9,000 My Branches in operation.

Cloud Migration: An Industry First

Underneath the customer-facing products, Hana also made a foundational bet: moving core systems to the public cloud.

Working with Oracle, Hana Financial Group completed a large-scale migration of mission-critical applications—an industry first in Korea by its own description. The goal wasn’t just modern infrastructure for modern infrastructure’s sake. It was speed, scalability, and the ability to build new digital services without dragging legacy systems behind them.

Hana Members, the group’s integrated membership service and digital financial lifestyle platform with more than 15 million users, was positioned to be a lead vehicle for that strategy.

“Such a large-scale cloud transformation project is unprecedented in the finance industry, not to mention within HFG,” the company said.

The groundwork had been laid earlier. Hana already used Oracle infrastructure services including Oracle Database Cloud Service and Oracle Identity Cloud Service, after migrating from on-premises systems in September 2020.

The AI & Digital Asset Future

In November 2025, Hana made its boldest digital bet yet—and it wasn’t just about apps.

Hana Financial Group announced it would pursue financial transformation by embracing digital assets and AI. To do it, the group launched a task force at the holding company level, designed to coordinate digital asset initiatives across subsidiaries—banks, card businesses, and securities firms—while staying aligned with Korea’s evolving legal framework for digital assets.

The initial priority: stablecoins. Hana said the team would build an end-to-end cooperation framework, spanning issuance, reserve management, and real-world distribution networks.

This move also signaled urgency. Hana openly framed itself as a latecomer among Korea’s four major financial groups in the digital asset race—and positioned this push as a way to change the competitive landscape rather than defend the old one. The task force’s remit extended beyond stablecoins into other digital-asset categories, including cryptocurrency spot ETFs and security token offerings.

To accelerate learning and partnerships, Hana signed a comprehensive memorandum of understanding with Circle, the issuer of USDC, in May, and said it had also been discussing collaboration with Tether, the issuer of the world’s largest stablecoin.

Chairman Ham Young-joo summarized the ambition clearly: “Digital assets will be at the heart of innovation in capital markets and payment systems. At the same time, we will leverage AI to personalize customer services, enhance risk management and improve operational efficiency across the group. These two growth drivers — digital assets and AI — will lead Hana's financial transformation.”

Competing Against Big Tech

Hana’s digital posture is, ultimately, a decision about who it wants to compete with.

Because the new rivals aren’t just other banks. Kakao Bank sits inside a KakaoTalk ecosystem measured in tens of millions of users. Toss has built a super-app that bundles dozens of financial services into a single habit-forming interface. Against that kind of gravity, traditional banks can’t win by “improving the app.” They need new levers.

Hana is betting that AI capabilities and a serious position in digital assets—especially stablecoins—can become those levers, differentiating it from both legacy peers and tech-native challengers.

And it’s staffing for that future. Hana plans to nurture 3,000 data specialists by 2027 to strengthen risk assessment, data-backed personalization, operational efficiency, and fraud prevention. The goal builds on its earlier internal program, “2500 by 2025,” launched in 2022, where Hana pledged to train 2,500 data experts by 2025.

VII. Leadership & Culture: The Hana Way

Three Chairmen, Three Eras

Hana Financial Group has had only three chairmen since it became a holding company in 2005. In an industry where leadership churn can be the norm, that kind of continuity matters—because Hana’s biggest moves weren’t quick wins. They were multi-year campaigns.

In March 2012, Kim Jung-tai became the group’s second chairman. His tenure marked a clear shift in posture: Hana wasn’t just trying to be a great Korean bank anymore. It was trying to become a full-scale global financial group, expanding its overseas footprint and sharpening a more differentiated, professional set of services across the portfolio.

But Kim’s era will always be tied to the deal that defined the decade: acquiring Korea Exchange Bank and then wrestling it into a single operating reality. Buying KEB was bold. Integrating it—through labor opposition, politics, and years of uncertainty—was the kind of management test that doesn’t show up in spreadsheets until it’s over.

Then came the third era. With Ham Young-joo’s appointment as chairman, Hana opened what it framed as a new chapter—one built for a different set of turning points: an aging society, blurred boundaries across financial services, and a world where customers increasingly pick platforms, not banks. Ham’s stated agenda centered on increasing shareholder and corporate value, strengthening governance, and executing three core strategies: reorganizing non-banking businesses, elevating Hana’s global position, and driving digital finance innovation.

Ham was appointed Chairman and CEO in 2022 and secured another term in March 2025. He has also served as Chairman of the Hana Financial Group Foundation and as the owner of Daejeon Hana Citizen Football Club.

Inside Hana, Ham is known as someone who understands the full machine—its affiliates, its incentives, and its culture. He also had firsthand experience with the group’s defining integration moment: when Hana Bank and KEB officially merged in September 2015, Ham became the first leader of the combined bank and held the role for 43 months. His reputation was built in sales, and Hana credits him with strengthening synergy after the merger through an approach it describes as service-oriented and considerate leadership.

The through-line is clear: push harder overseas, build up the non-banking engines, and keep the core competitive in a market where “banking” increasingly means technology.

The "Hana Attitude" Culture

From Korea Investment Finance in 1971, to Hana Bank in 1991, to a full financial group in 2005, Hana frames its identity around value-oriented leaps: customer-centric, innovative, and built for what’s next, not what worked last decade.

That culture is packaged internally as the “Hana attitude,” and externally as a mission and a promise. The group’s mission is “Growing Together, Sharing Happiness,” and it positions that as a commitment to sustainable growth and corporate social responsibility. Its vision—“All Connected in Hana Finance”—signals what Hana wants to be in the modern era: a connected set of financial services that feels seamless to customers, even when the organization behind it is anything but simple.

VIII. Financial Performance & Recent Results

Record Performance in 2024

By 2024, Hana’s strategy wasn’t just visible in its footprint and product lineup. It showed up where it always has to, in the end: the income statement.

Hana Financial Group reported record net profit of 3.74 trillion won in 2024, up 9.3% from the year before.

Management also leaned into shareholder returns. The board approved a year-end cash dividend of 1,800 won per share, bringing the total dividend for 2024 to 3,600 won per common share, up 5.9% year over year. The total shareholder return ratio rose to 37.8%. And to underline what it called its “Value-Up” plan announced in October, the board approved a 400 billion won share buyback and cancellation—the largest in the group’s history—framing it as a reflection of “solid fundamentals” and a stronger commitment to returning capital.

The plan itself set an explicit target: raise shareholder returns to 50% by 2027 by improving earnings per share and dividends, while keeping return on equity above 10%.

At the subsidiary level, Hana Bank—still the engine—posted annual net profit of 3.34 trillion won.

The momentum carried into 2025. In the first quarter, Hana reported consolidated net income of 1.1277 trillion won, up 9.1% year on year, while Hana Bank delivered 992.9 billion won, up 17.8%.

And as of June 30, 2025, the group’s Common Equity Tier 1 ratio stood at 13.39%—a measure of capital strength that, in banking, is the difference between having options and having problems.

IX. Playbook: Strategic Lessons

Lesson 1: Crisis as Catalyst

The Asian Financial Crisis revealed a pattern Hana would return to again and again: if you stay disciplined in the good times, you earn the right to be aggressive in the bad times.

While weaker banks were being liquidated, rescued, or shoved into shotgun marriages, Hana went deal shopping. It acquired Chungcheong Bank, merged with Boram Bank, and then landed the one that truly changed its trajectory: Seoul Bank. Those moves weren’t opportunistic in the casual sense. They were only possible because Hana entered the crisis with enough balance-sheet strength to act when everyone else was trying to survive.

So the lesson isn’t “buy during crises.” It’s that restraint during the boom creates optionality during the bust—and optionality is what turns chaos into a growth strategy.

Lesson 2: The Long Game on M&A

If the crisis era was Hana’s sprint, the KEB deal was its marathon—and a masterclass in patience.

Hana Financial Group acquired Korea Exchange Bank in February 2012 from Lone Star, but the two banks didn’t become one until September 2015. For years, Hana ran a two-bank system under one holding company while it dealt with regulatory complexity, labor opposition, and the hard reality that “closing the deal” and “becoming one company” are totally different jobs.

The timeline says it all: roughly a year from deal agreement to closing, then three more years of parallel operations and negotiations before the merger was complete. Many acquirers would have tried to force integration earlier. Hana didn’t—at least not successfully at first—and in the end, that willingness to absorb time and friction was what made a unified bank possible.

Lesson 3: Regional Expansion Through Strategic Stakes

Outside Korea, Hana’s playbook was rarely to plant a flag and build from scratch. Instead, it repeatedly chose a more pragmatic route: take minority stakes in established local champions and use partnerships to get distribution fast.

You can see it in the stake in Bank of Jilin in China, in the build-out in Indonesia alongside local acquisitions and partnerships, and most clearly in Vietnam with BIDV. The benefits are obvious: instant access to existing branch networks and customer relationships, lower execution risk than an organic rollout, and a way to export Hana’s know-how—especially in consumer banking—without taking on full operational responsibility from day one.

BIDV is the cleanest example. With one investment, Hana gained a meaningful position in a major Vietnamese bank and access to a nationwide footprint—something that would have been slow, expensive, and uncertain to recreate independently.

Lesson 4: Digital Transformation as Defense

Hana’s digital push is, at its core, a defensive move—because the new threat isn’t another branch-based bank. It’s mobile-first competitors like Kakao Bank and Toss Bank training customers, especially younger ones, to expect banking that feels like software.

That’s why Hana’s response goes beyond polishing an app. The cloud migration, the platform strategy, and the more recent push into AI and digital assets—stablecoins in particular—are attempts to change the terms of competition, not just keep up with it.

Whether Hana’s bets pay off is still an open question. But the strategic insight is clear: in modern banking, incremental digital change rarely protects you from platform-native rivals. If you want to stay relevant, you have to rebuild the machine, not just repaint it.

X. Bull Case & Bear Case

Bull Case

A dominant FX franchise: Thanks largely to what it inherited from KEB, Hana sits on one of the most valuable, least flashy assets in Korean banking: foreign exchange. Hana Bank has been South Korea’s longest-running exchange bank and holds roughly 40% of the country’s FX market. That matters because FX generates steady fee income, and compared with traditional lending, it tends to carry less direct credit risk.

Vietnam upside: The BIDV stake is a long-duration bet on one of Asia’s fastest-developing economies. Vietnam’s banking market is still far less penetrated than Korea’s, which creates room for years of growth in consumer finance, payments, and everyday banking. In other words: Hana didn’t just buy a stake; it bought exposure to a country that’s still early in its financial deepening.

A real shift toward shareholder value: Hana’s “Value-Up” posture is also a meaningful change in a market where banks historically returned relatively little capital to shareholders. The group has said it aims to lift total shareholder return to 50% by 2027, up from about 38% in 2024. If it follows through, that’s not just a one-time boost—it’s a re-rating catalyst.

Digital first-mover potential in stablecoins: Hana’s digital asset task force, plus partnerships and discussions with major stablecoin players like Circle and Tether, gives it a seat at the table if Korea moves toward won-based stablecoin infrastructure. If regulators allow it and adoption follows, Hana could be early enough to shape how stablecoins plug into mainstream banking rails.

Bear Case

Neobank competition: The biggest threat isn’t another legacy bank; it’s the new default for younger customers. Kakao Bank’s user base and Toss’s rapid growth have changed the acquisition game in Korea’s saturated market. When customers can open an account in minutes and do everything from a single super-app, incumbents have to fight to stay top-of-mind, not just top-of-wallet.

Interest rate sensitivity and the credit cycle: Hana is still a commercial bank at its core, which means earnings can be squeezed when rates compress and risks rise when the credit cycle turns. That showed up in asset quality: the group’s non-performing loan ratio increased to 0.70% in Q1 2025, up from 0.53% in Q1 2024.

Regulatory uncertainty: Korea’s financial system remains deeply shaped by regulation and politics. The Lone Star saga is the reminder here: regulatory delays and investigations don’t just slow transactions—they can become years-long liabilities with real reputational fallout.

Concentrated exposure to Korea: Hana has expanded across Asia, but Korea still dominates earnings. That means any sharp downturn in the domestic economy hits Hana harder than the “global footprint” story might suggest.

Porter’s Five Forces Analysis

Threat of new entrants: High. Kakao Bank, Toss, and K Bank proved that with the right product and distribution, you can scale fast without a branch network.

Bargaining power of buyers: Increasing. Switching is easier than ever, and digital channels make rates and fees more transparent.

Bargaining power of suppliers: Low. Banks can generally access diversified funding sources.

Threat of substitutes: High. Fintechs, Big Tech payments, and—if they become mainstream—stablecoins can displace traditional banking products in everyday use cases.

Competitive rivalry: Intense. Korea’s major financial holding companies are battling in a mature market with limited room for differentiated growth.

Hamilton Helmer’s 7 Powers

Hana’s most credible power is Scale Economies, especially in FX and corporate banking, where transaction volume, relationship density, and operational efficiency reinforce one another.

The BIDV partnership could create Network Effects if cross-border payments and remittances scale alongside Korean-Vietnamese trade and investment flows.

Switching Costs still exist—but they’re weakening as digital onboarding makes changing banks feel close to frictionless.

Finally, Hana’s Counter-Positioning effort—leaning into AI and digital assets—is a deliberate attempt to build new advantages in a market where the old ones (branches, legacy relationships, inertia) are losing power. But the outcome is not guaranteed.

XI. Key Metrics to Watch

If you want a simple dashboard for whether Hana is winning the next phase of the game, it comes down to three numbers that tell you how healthy the core is, how efficiently it runs, and whether customers are actually choosing it in a mobile-first world:

1. Net Interest Margin (NIM): In Q1 2025, Hana’s NIM was 1.69%. This is the spread between what the bank earns on loans and what it pays on deposits—the heartbeat of a traditional bank. If that spread starts shrinking because of rate moves or aggressive competition for deposits, profitability pressure usually follows.

2. Cost-Income Ratio: Hana posted a cost-income ratio of 38.5% in H1 2025. Think of this as the efficiency check: how much it costs to generate a won of revenue. As Hana keeps spending on cloud, data, and digital capabilities, holding this line will show whether management is converting investment into scale, not just expense.

3. Digital Channel Sales Penetration: The share of products sold through digital channels is the most honest read on whether Hana’s “platform” story is real. It’s not just about app downloads—it’s whether customers are opening accounts, buying funds, taking loans, and doing the profitable stuff without ever needing a branch. In Korea’s market, that’s the frontline against neobanks.

XII. Conclusion: The Outsider's Legacy

Fifty-four years ago, 26 individuals opened Korea’s first privately funded financial company with just two branches in Seoul and a contrarian belief: that independence from government direction—not subservience to it—could compound into lasting value.

They were right. But it didn’t happen in a straight line.

The Asian Financial Crisis wasn’t just a macro shock; it was Hana’s proving ground, when discipline turned into the ability to act while others were forced to retreat. The Korea Exchange Bank saga wasn’t just an acquisition; it was a decade-spanning collision of politics, public outrage, labor conflict, and global arbitration—one that ultimately remade Hana’s scale and identity. And the digital transformation era isn’t just a modernization project; it’s a fight over whether the customer relationship belongs to banks or to the apps where people already live.

Through all of it, Hana kept doing something rare in Korean banking: it stayed profitable for decades and kept paying dividends, building a reputation for durability in an industry that tends to be defined by cycles and shocks. That track record is the foundation beneath today’s ambition to stand as a world-class financial group, not only a Korean champion.

But the next test is different. Hana’s historical playbook—use crisis as leverage, execute patient M&A, integrate over time—was built for a world where threats often came from weaker institutions and turbulent balance sheets. Kakao and Toss aren’t distressed banks waiting to be consolidated. They’re well-capitalized, technologically sophisticated, and native to the digital habits of younger Koreans.

Hana’s answer is to change the arena: rebuild its infrastructure, lean into platforms, and place big bets on AI and digital assets, with stablecoins at the front of the line. Whether those bets work will determine whether Hana’s next half-century looks like compounding—or catching up.

For now, the 1971 outsider has become one of Asia’s most consequential financial groups. And its story is a reminder that in banking, as in life, the long game doesn’t always win—but it’s usually the only game worth playing.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music