EcoPro: The Cinderella Story of Korea's Battery Materials Revolution

I. Introduction: When an Obscure KOSDAQ Stock Surpassed Hyundai Motors

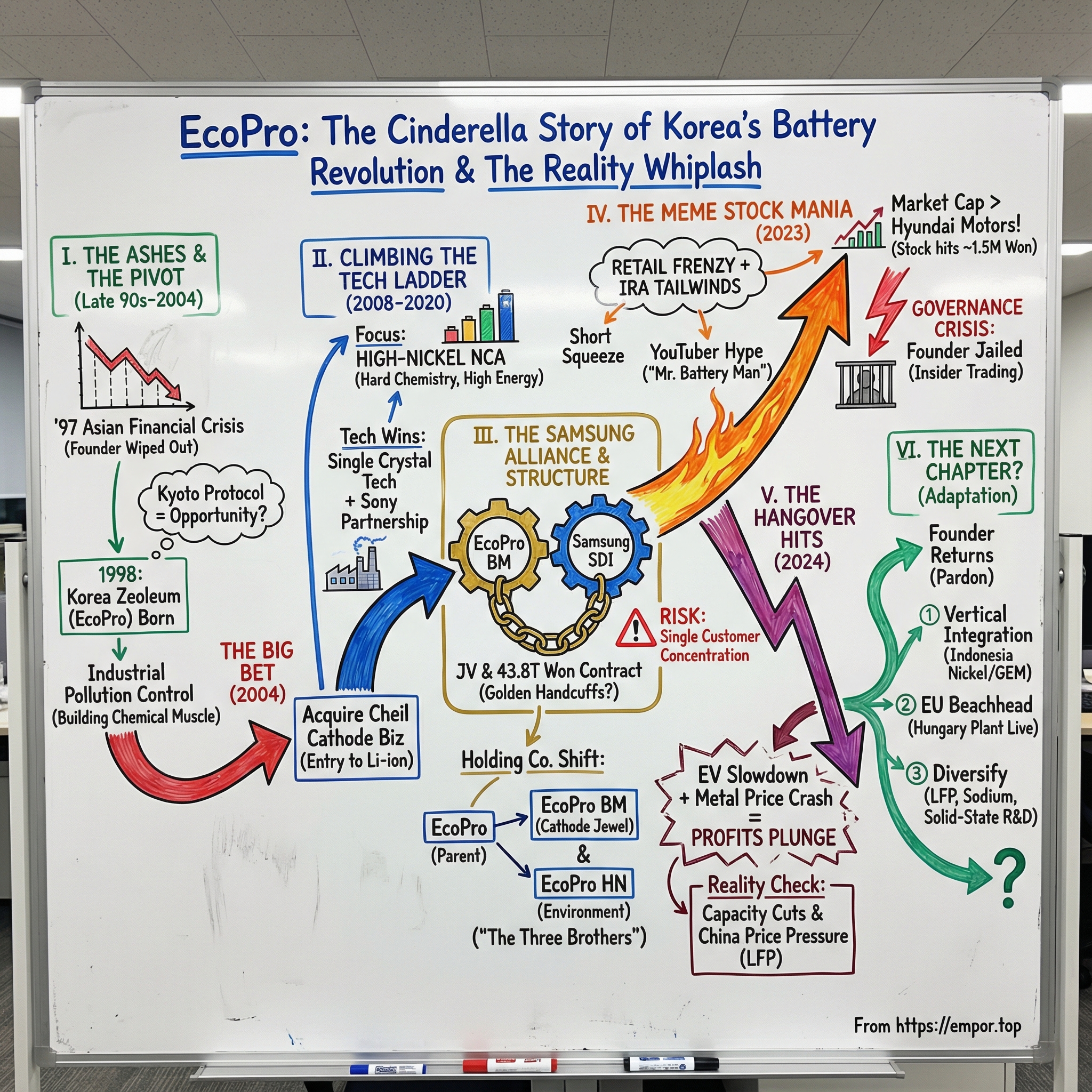

Picture Seoul’s markets in the summer of 2023. Out of nowhere, a battery materials company most global investors couldn’t have picked out of a lineup started printing headlines that sounded like a typo: "South Korean battery material producer Ecopro Co.'s blistering run has seen the shares up 919% this year, the biggest gain for any company with a market capitalization of at least $10 billion."

And it wasn’t just the chart that was shocking. It was the scale. The combined market cap of EcoPro and its cathode-materials arm, EcoPro BM, climbed to nearly 44.8 trillion won—enough to edge past Hyundai Motors at 40.9 trillion won. Sit with that for a second. A company that lives deep inside the EV supply chain—making cathode materials, the invisible guts of a battery—was suddenly being valued above one of the most iconic automakers on the planet.

So how did this happen?

EcoPro’s rise has all the plot twists of a Korean business drama. A founder who tried—and failed—at a fur business. A wipeout in the Asian Financial Crisis. A reboot inspired by the Kyoto Protocol and the idea that pollution control could become a real industry. Then a massive pivot: a bet on a specific battery chemistry path that many peers didn’t take, and a buildout that turned a niche industrial player into a national obsession.

And then the darker chapters arrived: insider trading allegations, the founder stepping down, a prison sentence, and a retail-investor frenzy so intense that basic valuation arguments stopped working. Finally, when EV demand cooled faster than the industry expected, the hangover hit.

That tension is what makes EcoPro more than just a stock story. It forces a bigger question—one that hangs over the entire EV supply chain: what happens when a company with real technology and real customers becomes a vessel for speculative mania? Is EcoPro a durable champion of the battery age, or a case study in how quickly excitement can detach from fundamentals?

Either way, it’s a story about chemistry and capital markets, about governance and hype, about institutions walking away while individuals pile in. And it’s also a story about something rarer in modern Korea: a non-chaebol company clawing its way into an industry that could define the 21st-century economy.

II. The Founder's Journey: From Fur Trader Failure to Climate Visionary

To understand EcoPro, you have to understand Lee Dong-chae—the kind of founder Korea doesn’t produce very often. Not a chaebol heir. Not a career politician. An accountant who got knocked flat by the Asian Financial Crisis, then rebuilt his life around a thesis that sounded, at the time, like a niche: pollution control was going to become real industry.

Lee was born on December 10, 1959, in Pohang, South Korea. He was the second of eight children—all sisters except for him. He took a practical path up the ladder: graduating from Daegu Commercial High School and Yeungnam University (business administration), working at Housing & Commercial Bank and Samsung Electronics, and earning his Certified Public Accountant credential.

That resume matters, because it explains how he thinks. Accounting trains you to see incentives, cash flows, and risk—what’s real versus what’s just narrative. And a stint inside Samsung gave him a front-row seat to Korea’s industrial machine. But unlike the executives who could ride out downturns, Lee’s margin for error was thin.

Then the Asian Financial Crisis hit in 1997–98, and it didn’t just shake the country—it wiped him out personally. Before EcoPro, Lee invested in a fur business with a relative. It went bankrupt in the crisis, and he lost everything. For someone whose whole professional identity was built on financial discipline, that kind of total loss wasn’t just a setback. It was a rewrite.

He later pointed to that failure as a turning point: it taught him the value of having a truly differentiated idea, of building the right team, and of respecting how brutally capital markets can reward—or punish—timing.

But while his personal finances were collapsing, something else was happening in the world. In 1997, the Kyoto Protocol created the first real, binding international push to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. Lee read that not as politics, but as an emerging demand curve. If governments were going to force industry to clean up, someone would have to sell the tools.

So in 1998, he founded what would become EcoPro, originally under the name Korea Zeoleum (코리아제오륨). In 2001, it became EcoPro. The early products were the kind of industrial work no one celebrates: air pollutant control technologies, greenhouse gas reduction devices, chemical filters for cleanroom environments. Important, technical, hard to do well—and quietly foundational.

Because here’s the twist: those “unsexy” environmental systems required capabilities that map eerily well to battery materials. Chemical processing discipline. Tight quality control. Manufacturing consistency. Relationships with demanding industrial customers. EcoPro wasn’t just selling equipment—it was building a chemical production muscle.

By 2004, the company began trading battery precursors, and that line of business quickly became far more than a side hustle. It was a signal that EcoPro was already feeling for the next wave.

One popular description later framed EcoPro as a company launched by a 63-year-old accountant after a failed fur venture. That gets the spirit right—reinvention after disaster—but not the timeline. Lee founded the company in his late thirties, starting over with a bet that sounded almost naïve in 1998: that climate rules would stick, and that the businesses enabling compliance would be worth building.

EcoPro’s IPO in 2007 marked a real milestone, but it wasn’t a coronation. At that point, EcoPro was still largely an environmental business, with battery materials just beginning to show their gravitational pull.

And the next chapter is when that pull becomes impossible to ignore.

III. The Environmental Foundation Years: Building Chemistry Expertise

Before EcoPro became synonymous with EV batteries, it spent its first decade doing the kind of industrial work that rarely makes headlines: building chemical know-how in the trenches of pollution control.

From 1998 onward, EcoPro focused on eco-friendly materials and components designed to clean up what factories produced—harmful gases, industrial byproducts, and greenhouse emissions. This wasn’t branding. It was engineering. The company worked on adsorbents and catalysts that trap toxic gases, chemical air filters used in semiconductor cleanrooms, and equipment meant to reduce greenhouse gas emissions inside manufacturing lines.

And EcoPro wasn’t just selling “green” products. It was quietly developing the capabilities that later mattered in batteries: precision chemistry, repeatable manufacturing, and ruthless quality control. In 2003, the company successfully localized key materials for secondary batteries that Korea had previously relied on imports for—early evidence that EcoPro’s ambitions were already stretching beyond environmental systems.

Those years also put EcoPro in the orbit of the most demanding customers in Korean industry. Long before EcoPro HN was spun off in 2021, EcoPro supplied cleanroom chemical filters and other hazardous-waste-reduction products to major names including Samsung Electronics and HD Hyundai Heavy Industries. And if you want to understand why this mattered, start with Samsung. Its cleanroom standards are unforgiving; parts that miss spec don’t get “worked with,” they get replaced. Winning that business—and keeping it—forced EcoPro to build internal quality systems that were far above what a small supplier typically runs on.

In 2006, that hard-earned credibility got a public stamp. The Ministry of Commerce, Industry and Energy selected EcoPro’s PFC Gas Scrubber as a new energy resource technology. That wasn’t just a nice plaque. Perfluorinated compounds are some of the most potent greenhouse gases, and semiconductor manufacturers were under pressure to cut their emissions footprint. EcoPro had built something the market actually needed.

But even with technical wins, the environmental business had a ceiling. Growth followed industrial capex cycles. Competition kept margins tight. It was steady, respectable work—but it wasn’t the kind of platform that turns a small Korean company into a world-scale contender.

Then, in 2004, Lee got a proposal that opened a completely different door: acquire Cheil Industries’ cathode materials and precursor business.

This was the pivot point. Cheil Industries, a Samsung affiliate, was divesting non-core operations. Its battery materials unit was small, but it came with something priceless: real technology and a foothold in a supply chain that, at the time, was dominated by Japanese incumbents. For Lee, it wasn’t just an acquisition. It was an entry ticket into lithium-ion.

The timing helped. The Prius had already shown the world what electrification could look like, and the mobile-device boom was driving relentless demand for better batteries. But cathode materials were a Japanese stronghold, and Korean players were widely seen as behind.

Lee’s bet—shaped in part by his time inside Samsung’s ecosystem—was that Korea had a familiar playbook: enter as a follower, invest aggressively in process and scale, then close the gap through manufacturing discipline. The question now wasn’t whether batteries were going to matter. It was whether EcoPro could pull off that playbook in one of the most chemistry-intensive parts of the value chain.

IV. The Battery Pivot: A Technical Gamble on High-Nickel Chemistry

EcoPro’s defining move wasn’t a new factory or a flashy acquisition. It was a decision made in the lab: to bet on NCA cathodes—nickel, cobalt, aluminum—and to push nickel content far higher than most of the industry was comfortable with.

That choice matters because cathodes are the economic and performance heart of an EV battery. They’re a big chunk of the cost, and the chemistry largely dictates how much energy the battery can hold—aka how far the car goes on a charge. More nickel generally means higher energy density. But it also means you’re signing up for harder manufacturing, tighter quality control, and more safety risk. High reward, high stress.

EcoPro got there early. In 2008, it commercialized high-nickel NCA cathode materials with nickel making up more than 80% of the composition, then kept iterating—pushing quality and consistency higher as the industry’s expectations rose.

By the mid-2010s, EcoPro landed a partnership with Sony to supply cathode materials on a long-term basis. In battery-world, that was a serious stamp of approval. Sony had invented the commercial lithium-ion battery back in 1991 and set the tone for quality standards for years. If EcoPro could meet Sony’s specs reliably, it wasn’t just “in the game.” It was playing at the highest level.

Around the same time, EcoPro BM achieved another technical milestone: mass-producing single crystal cathode technology—single particles rather than the more common polycrystalline structure—for the first time in the world.

Here’s why that’s a big deal. Traditional cathode particles are polycrystalline: lots of tiny crystals fused together. Those internal boundaries become weak points, and over repeated charge-and-discharge cycles, they can crack. Single crystal particles reduce those internal fault lines, which can improve cycle life and thermal stability. The tradeoff is that they’re harder and more expensive to manufacture. But for high-performance applications, the durability and stability can be worth it.

This is where Lee Dong-chae’s risk tolerance shows up in the product roadmap. While many Korean materials players leaned into NCM chemistries—nickel, cobalt, manganese—because they were more forgiving to make and easier to sell to a wider range of customers, EcoPro kept leaning into the harder path. NCA was narrower, pickier, and demanded real process excellence. But if you mastered it, you could become indispensable to the customers who needed it.

That strategy pulled EcoPro into an increasingly tight orbit with Samsung SDI, Korea’s leading battery cell maker. Together, they worked on next-generation NCA cathodes with nickel content pushing as high as 95%—a bleeding-edge target where every incremental gain in nickel makes production dramatically more difficult. High-nickel materials are more thermally unstable and more prone to surface reactions that degrade performance. Getting them to work at scale isn’t just chemistry; it’s industrial discipline.

The payoff, if you can pull it off, is real. NCA can deliver meaningfully higher energy density than standard NCM, which makes it attractive for premium EVs where range and performance justify complexity and cost. But that same complexity narrows the buyer pool. Not every battery maker wants the headache of NCA—and the ones that do tend to rely heavily on a small number of suppliers who can consistently meet spec.

EcoPro was building something powerful: a technical moat. But it came with a structural consequence that would shape everything that followed—customer concentration, higher stakes, and a business that could soar when demand hit… and feel brutally exposed when it didn’t.

V. The Samsung Alliance: Kingmaker Partnership and Single Customer Risk

EcoPro BM’s relationship with Samsung SDI didn’t stay a normal supplier contract for long. It evolved from “one of several vendors” into a strategic alliance—and, in important ways, into something closer to co-dependency. If you want to understand both EcoPro’s power and its exposure, you start here.

EcoPro BM first began supplying cathodes to Samsung SDI in 2011. At the time, it was simply another supplier in the mix. But year by year, EcoPro kept doing two things that mattered to a battery maker with big ambitions: it kept pushing the limits of high-nickel NCA chemistry, and it kept investing in capacity ahead of demand. That combination—technical credibility plus willingness to build—earned it a larger and larger share of Samsung SDI’s attention.

By 2020, the relationship got a formal “we’re in this together” structure. EcoPro BM and Samsung SDI set up a joint venture, EcoPro EM Co., to supply NCA cathodes to Samsung SDI’s offshore battery plants. A JV is more than collaboration. It’s Samsung SDI effectively saying, “We’re willing to co-invest in dedicated manufacturing for this chemistry.” And for EcoPro, it meant visibility and a level of customer lock-in most materials companies can only dream about.

Then came the contract that made the scale of this alliance impossible to ignore. EcoPro signed a supply agreement with Samsung SDI for cathode active materials worth 43.8 trillion won (about 30.9 billion euros), covering 2024 through 2028.

On its face, it’s just a number. In reality, it’s a signal: EcoPro wasn’t just a vendor anymore. It was becoming infrastructure inside Samsung SDI’s EV strategy. The deal delivered commercial security, yes—but more importantly, it validated EcoPro’s strategic importance to a major battery maker.

This wasn’t a brand-new relationship suddenly turning huge. Since 2011, EcoPro BM had supplied roughly 200,000 tons of cathodes to Samsung SDI over time. The companies had been building trust the hard way: through consistency, yield, and quality on a chemistry that doesn’t forgive sloppiness.

Samsung SDI, for its part, supplies EV batteries to automakers including BMW, General Motors, and Hyundai Motor Co. But it’s also the smallest of Korea’s top three battery players, behind LG Energy Solution and SK On. That detail matters because it means EcoPro’s trajectory is tied to a company that is itself fighting for position. If Samsung SDI wins share—especially in the premium segments where NCA’s energy density shines—EcoPro wins with it. If Samsung SDI stumbles, EcoPro feels the hit.

And EcoPro wasn’t shy about the tradeoff. When the company was pressed about diversifying beyond Samsung SDI, leadership made the strategic line clear: it would not supply materials to Samsung SDI’s competitors.

There’s logic in that stance. NCA cathodes are meaningfully different from the NCM formulations that LG Energy Solution and SK On mainly build around. Serving those customers would mean new lines, new processes, new qualification cycles—and real capital. Just as importantly, Samsung SDI’s willingness to sign long-term agreements is easier to justify when your key supplier isn’t also arming your rivals.

But the cost of that loyalty is fragility. Concentration risk isn’t an abstract finance term here—it’s the operating reality. Samsung SDI’s market performance, strategic choices, and relationships with automakers become variables EcoPro can’t control, but has to live and die by.

VI. Corporate Restructuring: The Holding Company Architecture

As EcoPro’s battery materials business started to outgrow its original identity, Lee Dong-chae made a move that looks mundane on paper, but changed everything about how the market would later understand—and trade—the company: he reorganized EcoPro into a holding company structure.

The cornerstone was EcoPro BM. In May 2016, EcoPro physically split off its cathode materials unit into a separate company so it could specialize in cathodes full-time. EcoPro BM went on to become a leader in high-volume cathode production in Korea and abroad, built on its early success developing and mass-producing high-nickel cathode materials.

The logic was simple and very “capital markets aware.” You separate the fast-growing battery materials engine from the slower, legacy environmental operations. Each business gets sharper focus. And investors get cleaner, “pure-play” exposure to the part of the story they actually care about.

That restructuring didn’t stop at cathodes. In 2021, EcoPro also split out its air environment business to launch EcoPro HN, completing the shift into a holding company setup. EcoPro, the parent, positioned itself as the group’s allocator—tasked with finding new growth engines, strengthening its ESG management system, and keeping the balance sheet steady enough to fund expansion.

Out of this came what Korean retail investors eventually dubbed “the three brothers”: EcoPro, EcoPro BM, and EcoPro HN—three publicly traded stocks that gave individuals multiple ways to “buy the EcoPro story.” And when expectations surged that Korean battery suppliers would benefit from the US Inflation Reduction Act—particularly the idea that cathode materials processed in Korea could qualify for tax credits—those three names started moving in sync, and then faster.

Meanwhile, EcoPro kept filling in the value chain. It launched EcoPro Materials in 2018 at the Yeongilman Industrial Complex in Pohang, and later added EcoPro Innovation and EcoPro AP in October 2022.

Pohang became the physical expression of this whole strategy: a dense industrial campus designed to house multiple specialized subsidiaries across battery materials and adjacent processes—precursors and other materials, lithium hydroxide, waste battery recycling, even gas production. Since 2020, the Pohang Campus has attracted a cumulative investment reported at 5.5 trillion won.

For a non-chaebol company, that kind of spending was almost surreal. The same founder who’d once been wiped out in a failed fur venture was now making long-range capital allocation decisions at a national-industrial scale.

But the holding company model also set the stage for what came next. It created a web of cross-linked valuations—EcoPro the parent holding stakes in EcoPro BM, the core operating crown jewel—so that momentum in one ticker could spill into the others. In a calm market, that’s just structure. In a frenzy, it becomes a feedback loop.

VII. The EV Boom and Capacity Expansion: Racing to Meet Demand

From 2020 through 2022, EcoPro hit a near-perfect window. EV adoption was accelerating, the industry’s growth narrative still felt unstoppable, and Samsung SDI’s push into premium batteries pulled EcoPro right along with it. This was the moment when “a strong customer relationship” turned into “build the world fast enough to keep up.”

The clearest symbol of that shift was Europe.

In April 2023, EcoPro broke ground on a new cathode materials plant in Debrecen, Hungary—its first major manufacturing facility outside Korea. The plan was straightforward and massive: 108,000 tons of cathode materials per year, a workforce of 631, and a production flow designed to feed Samsung SDI’s battery factory in Göd, near Budapest. EcoPro said that output would be enough cathode material to support batteries for roughly 1.35 million electric cars.

Strategically, Hungary checked every box. It put EcoPro close to Samsung SDI’s European operations, reduced logistical friction, and positioned the company inside an EU market that was tightening rules and expectations around local supply chains. For EcoPro, it was also a statement: this wasn’t a Korea-only success story anymore.

EcoPro BM began constructing the Debrecen base with the same 108,000-ton annual target and a total investment of about $1.28 billion. The plant was scheduled to begin mass production in the first half of 2025—timed to catch Europe’s next wave of EV expansion, and to turn EcoPro into a real European supplier rather than an exporter shipping from Asia.

North America required a different playbook. Instead of a single-customer gravity well like Samsung SDI, the US and Canada incentive landscape pushed companies toward joint ventures and localized ecosystems. EcoPro BM’s route was to partner with SK On and Ford in Canada. “The excavation work for the factory has already begun, and the construction will be in full swing once we finish establishing the joint venture with SK On and Ford,” said Joo Jae-hwan, CEO of EcoPro BM. EcoPro BM agreed with SK On and Ford Motor to invest a combined 1.2 billion Canadian dollars ($888 million) to build the new factory, and EcoPro BM planned to be the largest shareholder of the forthcoming JV.

That SK On partnership carried an extra layer of meaning: it was diversification. After years of leaning heavily on Samsung SDI, EcoPro was finally building a second major customer lane—even if it had to do it through a separate entity structure, in a different geography, with different partners at the table.

With these projects underway, EcoPro’s ambitions started to read like a different company entirely. The group targeted 710,000 tons of cathode output by 2027, with 180,000 tons produced in South Korea. Translated into the language investors loved most: that’s materials volume on a scale that implied batteries for millions of EVs—something that would’ve sounded almost absurd just a few years earlier.

But this is the cost of playing offense at industrial scale. New plants don’t come online because a slide deck says they will. They come online after permits, construction, equipment installation, commissioning, yield tuning, and training entire workforces to hit battery-grade quality standards. And all of it depended on a single macro assumption: that EV demand would keep compounding.

In 2024, that assumption would get put on trial.

VIII. The Insider Trading Scandal: Governance Crisis at the Top

Just as EcoPro was scaling into a global battery-materials contender, a different kind of risk surfaced—one that couldn’t be solved with better chemistry or more factory capacity.

On January 26, 2022, allegations emerged that would shake the company’s leadership and put its governance under a spotlight. Not long after, Dong-chae Lee resigned as CEO. EcoPro also moved to replace its executive directors—an aggressive, top-down reset that was widely read as an attempt to repair the company’s image after the combined damage of recent factory fires and the insider trading controversy, and to protect its standing as one of Korea’s leading battery materials groups.

The company framed the shake-up as part of a broader management restructuring Lee had referenced when announcing a future growth plan late the prior month: a shift away from CEO-centered control toward more board-centered governance. In theory, it was modernization. In practice, it was crisis response.

The allegations themselves were straightforward and brutal: that Lee had traded shares using material non-public information related to cathode supply agreements. According to the Supreme Court, he used accounts registered under different names, including accounts belonging to his children, to trade EcoPro BM stock. Local media reported he allegedly earned illegal profits of about 1.1 billion won by buying shares through a borrowed-name account.

Lee stepped down as CEO in March 2022 and became an advisor as investigations continued. On May 11, 2023, a court found him guilty of insider trading involving 1.1 billion won, imposed a fine of 2.2 billion won and a surcharge of 1.1 billion won, and sentenced him to 15 months in prison. He appealed, but the Supreme Court ultimately rejected the appeal. He is serving a two-year sentence for violating South Korea’s capital market act.

EcoPro’s governance response was sweeping, but it also underlined how dependent the group had been on its founder. One of the most visible moves was at the core subsidiary: EcoPro BM brought in outside leadership for the first time. Jaehwan Joo, the former CEO of Iljin Materials, was appointed CEO of EcoPro BM. Joo had led Iljin Materials—known for producing thin copper foil—from 2014 to 2020, and earlier in his career he had worked at Samsung SDI as a quality innovation team leader and a cell business manager. The message was clear: EcoPro BM wanted operational rigor and credibility, not just founder instinct.

Regulatory posture changed too. EcoPro and its subsidiaries joined the South Korean Fair Trade Commission, putting the group under tighter oversight and scrutiny. A company spokesperson told Bloomberg that EcoPro had also introduced mandatory reporting of stock transactions by senior employees and executives, along with a monitoring system designed to flag insider trading.

And then there was the timing—almost absurd in hindsight. The alleged 1.1 billion won in illegal profit would soon look microscopic next to the legitimate wealth created by EcoPro’s 2023 stock surge. Lee’s 18.84% direct stake, plus additional indirect family holdings, would become worth billions of dollars during the meme-stock run—dwarfing anything he could have gained through illicit trading.

Yet even as the company tried to distance itself from him, it couldn’t fully escape his gravitational pull. A spokesperson told Bloomberg the business was suffering without Lee’s leadership and was in “desperate need” of his “forward-looking insight and spirit to challenge.”

That contradiction is the real story of this chapter. Founder-led companies often win because decision-making is concentrated—fast, opinionated, and willing to take uncomfortable bets. But when power is that concentrated, governance failures don’t stay contained. They become existential.

IX. The Meme Stock Mania: Korea's GameStop Moment

What happened to EcoPro’s stock in 2023 didn’t just surprise the market. It broke the market’s normal tools for explaining itself—and turned a battery-materials supplier into a cultural event.

For most of its life, EcoPro was the definition of “specialist industrial name”: a Kosdaq-listed company understood by engineers and a handful of sector analysts. Then, seemingly overnight, it became one of the most talked-about stocks in Korea. EcoPro and its affiliates started rocketing upward on the back of a retail investor frenzy, with price action that looked less like incremental repricing and more like a collective fixation.

EcoPro effectively became Korea’s hottest meme stock—viral, tribal, and supercharged by social sentiment. The buying spree began in February, when pundits started naming EcoPro and EcoPro BM as prime beneficiaries of the EV battery boom. One of the loudest voices was a Kumyang Co. executive who became known online as “Mr. Battery Man.”

That “Mr. Battery Man” phenomenon matters because it shows how this rally formed. Unlike the U.S. meme-stock era, where Reddit communities acted as the organizing layer, EcoPro’s run was fueled by industry-adjacent influencers—insiders-turned-online personalities—making bullish calls on YouTube and social platforms. The meme stock mania even produced a prominent online tipster widely known as “Mr. Batt-Man” or “Mr. Battery,” whose growing following poured gasoline on an already-hot sector.

And it wasn’t pure fantasy. The story had real underlying catalysts. Korean retail investors had become intensely focused on anything tied to EV batteries, and the U.S. Inflation Reduction Act poured jet fuel on that theme. The IRA’s push to localize the EV supply chain—while effectively squeezing out Chinese players—made Korean cathode materials look strategically valuable, especially given provisions tied to free-trade partner countries.

In other words: there was a plausible macro narrative. But the stock’s behavior quickly outgrew the narrative.

EcoPro’s shares surged from about 110,000 won on Jan. 2 to 769,000 won by April 11. In May, as the stock kept printing new highs, some securities firms warned the shares were overheated, and the price pulled back to around 499,000 won on May 15. It didn’t matter. The stock soon rebounded—back into the 700,000-won range, then into the 900,000s. Before long, it crossed the symbolic one-million-won threshold—something that hadn’t happened for a Kosdaq-listed firm in 16 years, since Dongil Steel hit 1.1 million won in 2007.

As EcoPro’s climb turned into a spectacle, the plot simplified into a clean, market-friendly conflict: retail investors versus institutional short-sellers.

On one side were individuals, treating EcoPro as the flagship bet on Korea’s battery future. During the rally, individuals bought a net 1.72 trillion won of the stock. On the other side were foreigners and institutions, who sold—foreigners by 936.5 billion won and institutional investors by 762.8 billion won—while some major investment banks and hedge funds built short positions in EcoPro and EcoPro BM on valuation concerns.

But in a momentum market, shorts don’t just “express a view.” They become fuel. As prices kept rising, bearish positions were forced to cover. Lee Jae-wan, CEO of South Korean asset management company Tiger, captured the mood in a letter to clients: “The market has sent only a few names, which have been trading at high prices, not low levels, in the secondary battery sector to another world in the last two months. … We are perplexed with the situation.”

Short squeeze dynamics only magnified the swings. At one point, EcoPro’s short-selling balance surged, and the stock’s rapid rise looked increasingly like a feedback loop: price up, shorts cover, price up again.

Meanwhile, even speaking publicly about valuation became risky. Some analysts learned that putting a Sell rating on EcoPro wasn’t just unpopular—it could make you a target on YouTube and other online platforms. As one observer put it: “Many brokerage firms gave up on EcoPro’s stock analysis after watching analysts with Sell recommendations become a target of attacks.”

A rare Sell report cut against the mood, arguing that further upside would require a long period of digestion to prove midterm performance. The reaction wasn’t a typical disagreement. It was shock—because in the middle of a melt-up, the market’s social dynamics had begun to punish skepticism.

Then came the most surreal twist: the wealth effect.

As the stock soared, EcoPro’s founder Lee Dong-chae held shares worth nearly 2.5 trillion won—more, on paper, than the stakes held by chaebol heirs like SK Group Chairman Chey Tae-won (2.24 trillion won) and LG Group Chairman Koo Kwang-mo (2.08 trillion won). A self-made entrepreneur from Pohang—who had stepped down and been convicted over insider trading—was suddenly outranking Korea’s hereditary industrial dynasties in the only scoreboard that ever really matters in markets: market cap and ownership value.

But euphoric arcs don’t end with a fade. They end with a snap.

The turn came fast. On a Wednesday afternoon, EcoPro rose to 1.539 million won by 1:06 p.m.—and then, within roughly 40 minutes, plunged as much as 26% to 1.136 million won by 1:54 p.m. The volatility got so extreme that EcoPro and EcoPro BM together made up 20.4% of Kosdaq’s total market cap—meaning EcoPro’s whipsaw moves weren’t just moving portfolios. They were moving the entire exchange.

X. The Hangover: EV Slowdown and Reality Check

The collision between 2023’s euphoria and 2024’s reality was brutal for EcoPro’s shareholders.

After the run-up, the business ran straight into a double hit: battery-material prices fell faster than expected, and global EV demand cooled enough to delay the volume ramp everyone had been counting on.

EcoPro Co. said its consolidated operating profit for 2023 plunged 51.9% from 2022 to 295.2 billion won. Net profit dropped 61.2% to 85.5 billion won, even as the company posted record-high annual sales of 7.26 trillion won, up 28.7%. It was the kind of income statement that makes investors blink: revenue still climbing, but profitability collapsing.

That gap told the real story. The group—EcoPro, as the holding company over cathode producer EcoPro BM and chemicals firm EcoPro HN—attributed the profit slide to a steeper-than-expected decline in key battery-material prices like nickel and lithium, along with a slower recovery in EV demand.

And then the message got even sharper at the operating-company level.

EcoPro BM said it was considering reducing cathode output capacity despite having spent years investing aggressively in future growth. In the second quarter, EcoPro BM reported operating profit of 3.9 billion won, down sharply from a year earlier, with sales down 57.5%.

“We are considering slowing down and cutting mid- to long-term cathode capacity, given recent sluggish growth and volatilities in the EV market,” said EcoPro BM Vice President Kim Jang-Woo.

For a company that had been defined by expansion—more lines, more plants, more tons—talking about capacity cuts was a strategic about-face. The market slowdown, driven by factors like higher interest rates, gaps in charging infrastructure, and persistent range anxiety, had exposed the risk of building too far ahead of demand.

The revenue line showed the same whiplash. EcoPro BM’s 2024 annual sales were reported at 2.7668 trillion won, a dramatic drop from the peak levels of 2023, when the company recorded 6.9 trillion won in annual revenue as of Dec. 31, 2023.

And it wasn’t just EcoPro. The downturn was broad across Korea’s cathode sector: EcoPro BM and L&F both posted third-quarter losses of US$28.72 million and US$50.47 million, respectively.

The fact that everyone was suffering was cold comfort. When your stock has spent a year defying gravity, you don’t get judged on whether the whole industry is hurting. You get judged on how far you have to fall back to earth.

XI. The Hungary Plant: Europe's Beachhead Becomes Reality

Amid the financial turbulence, the Hungary project kept moving—one of those “we’re still building” signals that matters a lot when markets start doubting the whole EV supply chain.

EcoPro completed its cathode materials plant in Debrecen, Hungary and began commercial production, becoming the first Korean battery materials maker to establish a manufacturing base in Europe. The company said it marked the moment with a completion ceremony attended by founder Lee Dong-chae, EcoPro CEO Song Ho-jun, EcoPro BM CEO Choi Moon-ho, the head of the Hungarian Investment Promotion Agency Istvan Joo, GEM Vice Chairman Wang Min, SK On CEO Lee Seok-hee, and other executives from customer companies.

“The Hungary Debrecen plant is EcoPro’s first overseas cathode materials production base, built with an investment of 1.3 trillion won ($877.7 million),” Lee said at the company’s 2026 business briefing earlier this month. “We must turn it into a true treasure trove.”

At the ceremony, Lee laid out the ramp: trial production finishing before the end of 2025, and full commercial production beginning in the first half of 2026.

What EcoPro built in Debrecen wasn’t just a single factory. It was a mini campus designed to replicate the group’s Korea playbook overseas. On a 440,000-square-meter site, the complex includes EcoPro BM for cathode production, EcoPro Innovation for lithium processing, and EcoPro AP for industrial gas supply. The cathode plant is designed for 54,000 tons of annual capacity, which EcoPro said would support about 600,000 EVs. The lithium unit is set to produce 8,000 tons of lithium hydroxide per year, while EcoPro AP will supply 16,000 cubic meters of oxygen per hour.

“This is the first European production base built by a South Korean cathode producer, completed in just three years, thanks to Hungary’s swift one-stop support,” Lee said. “At a moment of rapid change in Europe’s EV industry, this marks a new beginning for EcoPro and the region.”

The location choice was deliberate. Hungary has become a battery hub, already home to Samsung SDI, SK On, CATL, and BMW. EcoPro also expects the plant to be cost-competitive by leaning on low-cost nickel tied to its Indonesian refinery investments and by deploying advanced automation.

That Indonesia connection is important, because it shows EcoPro trying to control more of the stack than “just” cathodes. The company completed the first phase of four nickel smelting projects in Indonesia, and said those investments generated 84.2 billion won in second-quarter revenue and 44.6 billion won in operating profit. EcoPro expects to generate an average annual profit of 180 billion won from Indonesia through at least 2030, and to secure 28,300 tonnes of nickel MHP annually.

Next comes the scale-up. EcoPro plans to double Debrecen’s annual cathode capacity to 108,000 tons starting next year, adding high-nickel ternary cathodes including NCA and NCM. After that investment, the company said its global cathode production capacity would rise to 300,000 tons per year.

XII. Founder's Return and Future Strategy: Life After Prison

In a development that captured Korea’s complicated relationship with founder-entrepreneurs, Lee Dong-chae returned to EcoPro after a presidential pardon.

After serving around half his sentence, Lee received a special pardon and was released from prison in August 2024. Soon after, he returned to the company as an adviser.

EcoPro confirmed that Lee—its former chairman—was brought back into the fold after roughly a year away from day-to-day leadership, just as both the company and the broader EV supply chain were grappling with slowing demand. Following the pardon, he was named an executive adviser on the board.

The symbolism mattered. But so did the urgency. EcoPro was in the middle of a global buildout, trying to lock in raw materials, defend margins, and broaden its product lineup beyond the high-nickel cathodes that had defined the group’s rise.

One of Lee’s first visible moves was to tighten EcoPro’s relationship with China’s GEM, one of the world’s largest precursor manufacturers. He invited GEM Chairman Xu Kaihua and Vice Chairman Wang Min to EcoPro’s headquarters in North Chungcheong Province—less a courtesy visit than a signal that EcoPro wanted to go deeper, faster, and more vertically integrated.

“Without disruptive innovation, there can be no breakthrough in the (EV) chasm,” Lee said in a statement. “Based on the 10 years of trust with GEM, we will set up a one-stop value chain ranging from smelting raw materials to manufacturing precursor and cathode in Indonesia.”

Indonesia sat at the center of that plan—and for good reason. Battery materials were becoming as much a geopolitical story as a chemistry story. US and European rules were increasingly sensitive to Chinese content in EV supply chains, but nickel processing in Indonesia didn’t fit neatly into those restrictions. By building in Indonesia, and doing it with a Chinese partner, EcoPro aimed to secure cost-competitive raw materials while staying compatible with Western import rules.

At the same time, EcoPro was trying to widen the aperture on what it could sell. For years, its identity had been tied to high-nickel ternary cathodes. Now it needed options—especially as the market started to prize affordability and stability as much as range.

“We have been developing sodium-ion-related technology for two years and have reached a level where it can be produced immediately,” Lee said. But he also acknowledged the constraint: without clear demand from Korean battery makers, EcoPro couldn’t justify full mass production yet. For now, it would watch the market and wait for the pull.

LFP was another frontier—and a harder one than it looks from the outside. It requires a different process and technology base than EcoPro’s existing ternary cathode playbook. EcoPro BM said it was pursuing LFP through multinational collaboration, benchmarking, and a deliberate push to break past its own process limits. In parallel, EcoPro said it was developing sodium cathode materials aimed at low-cost EVs and energy storage systems, emphasizing abundant resources and layered structures to pursue higher energy density, with a target of reaching mass-production readiness in 2025.

By InterBattery 2025—Korea’s largest battery exhibition—EcoPro put the whole roadmap on display. The company highlighted plans to establish an integrated cathode materials operation in Sulawesi, Indonesia, forming a single value chain from smelting to precursor production to cathode manufacturing. It also showcased development work on new materials for all-solid-state batteries—another bet that, if it works, could define the next generation of performance and safety.

EcoPro’s story had already been a roller coaster: environmental roots, a battery pivot, a Samsung-powered rise, governance scandal, meme-stock mania, and an industry hangover. Lee’s return marked the next act—one where the company tried to fight its way through the EV “chasm” by owning more of the supply chain, and by becoming more than a one-chemistry success story.

XIII. Strategic Analysis: Competitive Positioning and Industry Dynamics

To understand EcoPro’s strategic position, you have to zoom out from the stock chart and look at the battlefield it’s fighting on: a cathode materials market where everyone is sprinting toward higher nickel, China is pushing prices down, and customer relationships can matter as much as chemistry.

The Competitive Landscape

EcoPro BM has been in a very public arms race with its Korean peers to push nickel content higher, because higher nickel typically means higher energy density. One rival, L&F, has said it plans to begin mass production of NCM cathodes with 95% nickel content. EcoPro BM, for its part, has been reported as closing in on mass production around 94% nickel.

This fight matters because cathode materials—made from nickel, lithium, and other inputs—can account for roughly 40% of the cost of an EV battery. If you can deliver better performance at scale, you don’t just win a contract. You shape your customer’s roadmap.

But EcoPro isn’t competing in a vacuum. POSCO Future M has made its ambitions explicit too, aiming to become South Korea’s largest cathode material producer by 2030 and surpass domestic rivals like LG Chem, EcoPro, and L&F.

Where the companies differ is less about the headline “nickel percentage” and more about who they’re tied to, and which chemistry lane they’ve built around. EcoPro’s NCA strength has been closely aligned with Samsung SDI. L&F has historically supplied LG Energy Solution. POSCO Future M straddles customers, supplying both Samsung SDI and LG Energy Solution while also expanding with capacity aimed at General Motors’ Ultium venture.

That customer-and-chemistry alignment shapes everything: capital spending, qualification cycles, bargaining power, and what happens when end-market EV demand slows.

Porter’s Five Forces Analysis

Threat of New Entrants: MEDIUM-HIGH

High-nickel cathodes have real technical barriers, but they’re not permanent walls. Chinese producers have been climbing the learning curve quickly, and the economics are the bigger problem: Chinese materials have been cited as 20–30% cheaper than Korean alternatives. Across cathodes, anodes, separators, and electrolytes, multiple South Korean companies reported losses while Chinese firms remained overwhelmingly profitable. That price gap creates a kind of gravity that pure “we’re more advanced” messaging can’t fully defeat.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers: MEDIUM

EcoPro’s push into Indonesia and its partnership with GEM are, in part, an attempt to de-risk the most painful input problem: raw materials. But nickel and lithium pricing is still volatile and exposed to geopolitics. Vertical integration can smooth some shocks. It can’t eliminate commodity exposure.

Bargaining Power of Buyers: HIGH

EcoPro’s biggest structural vulnerability is also what made it powerful in the first place: Samsung SDI represents the overwhelming majority of its cathode sales. The long-term supply contract creates visibility, but customer concentration limits pricing power. And if Samsung SDI loses momentum with automaker customers, EcoPro takes the hit regardless of how well it executes operationally.

Threat of Substitutes: MEDIUM-RISING

The substitute isn’t “another supplier.” It’s another chemistry. LFP—dominated by Chinese producers—offers a different value proposition: lower energy density, but much lower cost and typically better safety characteristics. As EVs push into the mass market, and as buyers become less obsessed with maximum range, the economics of LFP get harder to ignore. EcoPro’s high-nickel focus positions it well for premium applications, but it’s exposed if the market keeps shifting toward value-oriented packs.

Competitive Rivalry: HIGH

In Korea, the fight is relentless: EcoPro, L&F, POSCO Future M, and LG Chem are all adding capacity and all chasing similar technical endpoints. When demand slows, that turns into a classic industrial problem—overcapacity risk—while the competitors still have to keep spending to stay technologically relevant. Everyone is running; no one can afford to stop.

Hamilton Helmer’s Seven Powers Analysis

Scale Economies: EcoPro has meaningful scale in NCA cathodes, but competitors are building similar capacity. Scale helps, but on its own it’s not a durable moat.

Network Effects: Cathode materials don’t benefit from network effects. They’re an industrial input, not a platform.

Counter-Positioning: EcoPro’s close alignment with Samsung SDI can look like a deliberate strategic stance, but functionally it behaves more like concentration risk than a position competitors can’t copy.

Switching Costs: Qualification creates moderate switching costs. Once a cathode is validated inside a battery design, changing suppliers is expensive and slow. But that protection applies to everyone, not just EcoPro.

Branding: Branding has limited leverage in B2B cathodes. Performance, price, and reliability win.

Cornered Resource: EcoPro’s Indonesia investments and GEM partnership are moves toward upstream control, but competitors are making similar plays, which limits exclusivity.

Process Power: This is EcoPro’s strongest “power.” Its single-crystal technology and accumulated high-nickel manufacturing know-how are real advantages. Producing 95%+ nickel cathodes at commercial scale is not something you replicate quickly from a blueprint. It takes time, iteration, and scar tissue. If EcoPro has a defensible moat, it lives here—in process discipline that customers can trust at scale.

XIV. Investment Considerations and Key Metrics to Track

If you’re looking at EcoPro as an investment, the story quickly stops being about “batteries are the future” and turns into something more specific: execution, concentration risk, and whether the company can widen its lane beyond one customer and one dominant chemistry.

Bull Case - A first-mover European footprint in cathode manufacturing could become a real advantage as EU local-content expectations tighten, and as customers increasingly want supply chains they can point to on a map. - Samsung SDI’s premium positioning in Europe—supplying luxury brands like BMW and Audi—creates a natural pull for EcoPro’s high-nickel cathodes, where performance and energy density still matter. - The Indonesia push is a classic margin defense: more vertical integration, better control of input costs, and less exposure to the worst swings in nickel-related economics. - Sodium-ion and solid-state cathode development gives EcoPro at least a credible option set for whatever comes after today’s high-nickel race. - Lee Dong-chae’s return adds strategic energy and relationship capital—valuable in a sector where long-term supply deals and cross-border partnerships can define the next decade.

Bear Case - Customer concentration is the biggest flashing red light. If Samsung SDI loses share, shifts strategy, or pushes for more aggressive pricing, the downside for EcoPro isn’t gradual—it’s structural. - Chinese competitors’ reported 20–30% cost advantage threatens pricing power across the industry, and it can creep upward even into “premium” niches once customers start optimizing total pack economics. - LFP keeps taking share in mass-market EVs, which shrinks the portion of the market where high-nickel cathodes are the default answer. - EV growth has cooled from pandemic-era expectations, raising the risk that the industry—EcoPro included—built capacity for a demand curve that showed up later than planned. - Governance remains an overhang. Even with reforms, the founder’s return after an insider trading conviction invites scrutiny, especially from institutions that already view the stock as socially volatile.

Key Performance Indicators

If you want a small dashboard that actually matters, watch three things:

-

Samsung SDI’s battery market share: EcoPro’s volume and pricing power are tied to its anchor customer. Quarterly share data from trackers like SNE Research can serve as an early signal of demand momentum—or demand leakage.

-

Nickel-to-cathode spread: In plain language, this is the margin story. When input costs swing and cathode pricing gets pressured, profitability can compress even if shipments look healthy.

-

Capacity utilization rates: With major capacity in Korea and Hungary, utilization tells you whether EcoPro is operating from strength or fighting oversupply. Sustained rates below roughly 70% tend to imply price pressure; above roughly 85% can indicate tighter markets and better operating leverage.

Regulatory and Legal Overhangs

In December 2024—months after Lee’s release—EcoPro began facing an investigation over allegations it maintained a slush fund for tax avoidance. Even without an outcome, investigations like this create a cloud: management distraction, reputational risk, and uncertainty around potential penalties depending on what authorities find.

On top of that, US trade policy became another variable the market couldn’t ignore. Reports that U.S. President-elect Donald Trump’s transition team was considering tariffs on battery materials globally—paired with the idea of negotiating exemptions with allies—triggered a sharp selloff in Korean cathode materials and copper foil names. For EcoPro, it was a reminder that the future demand curve doesn’t just depend on automakers and chemistry. It also depends on politics, rules, and who gets favored access to the world’s most important EV market.

XV. Conclusion: The Cinderella Story's Next Chapter

EcoPro’s journey—from a pollution-control specialist to a battery-materials powerhouse, then to a full-blown meme stock, and finally to a company forced to reckon with an EV slowdown—captures both what’s exhilarating and what’s dangerous about investing in the energy transition.

The underlying business isn’t a mirage. EcoPro built real technical edge in high-nickel cathodes, the sort of manufacturing know-how that only comes from years of iteration and painful quality battles. It has been turning that capability into a global footprint—anchored in Korea, expanding through Hungary, and reaching upstream toward Indonesia. And its deep alignment with Samsung SDI has brought something every industrial supplier craves: visibility. Long-term contracts don’t eliminate risk, but they do turn the future into something you can at least try to plan around.

But EcoPro’s story is also a cautionary tale. In 2023, the market stopped pricing the company like an operating business and started pricing it like a movement. Valuations ran far ahead of what fundamentals could comfortably justify, and the stock became a theater for social momentum, short squeezes, and identity-driven investing. When reality reasserted itself—through falling materials prices, slower EV demand, and the simple math of overbuilt capacity—the correction wasn’t polite. It was violent. Paper fortunes appeared, and then evaporated, with the pain concentrated among the investors who arrived last.

And looming over all of it is the founder. Lee Dong-chae’s arc—bankruptcy and reinvention, building a non-chaebol champion, then being convicted of insider trading and returning after a pardon—reads like a parable about modern Korea’s relationship with entrepreneurs. The same force that can create an outlier industrial success can also bend governance until it breaks. EcoPro has already lived both sides of that equation.

The EV revolution is still one of the defining industrial shifts of this era. Cathodes—or whatever replaces them in future chemistries—will remain essential. EcoPro has positioned itself to be part of that future. The open question is whether it can turn position into durable shareholder value in a world of intensifying competition, shifting chemistries, policy shocks, and demand cycles that no single company gets to control.

The Cinderella story continues. The clock just isn’t someone else’s problem anymore.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music