Celltrion Inc.: The Biosimilar Pioneer That Rewrote the Rules of Big Pharma

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

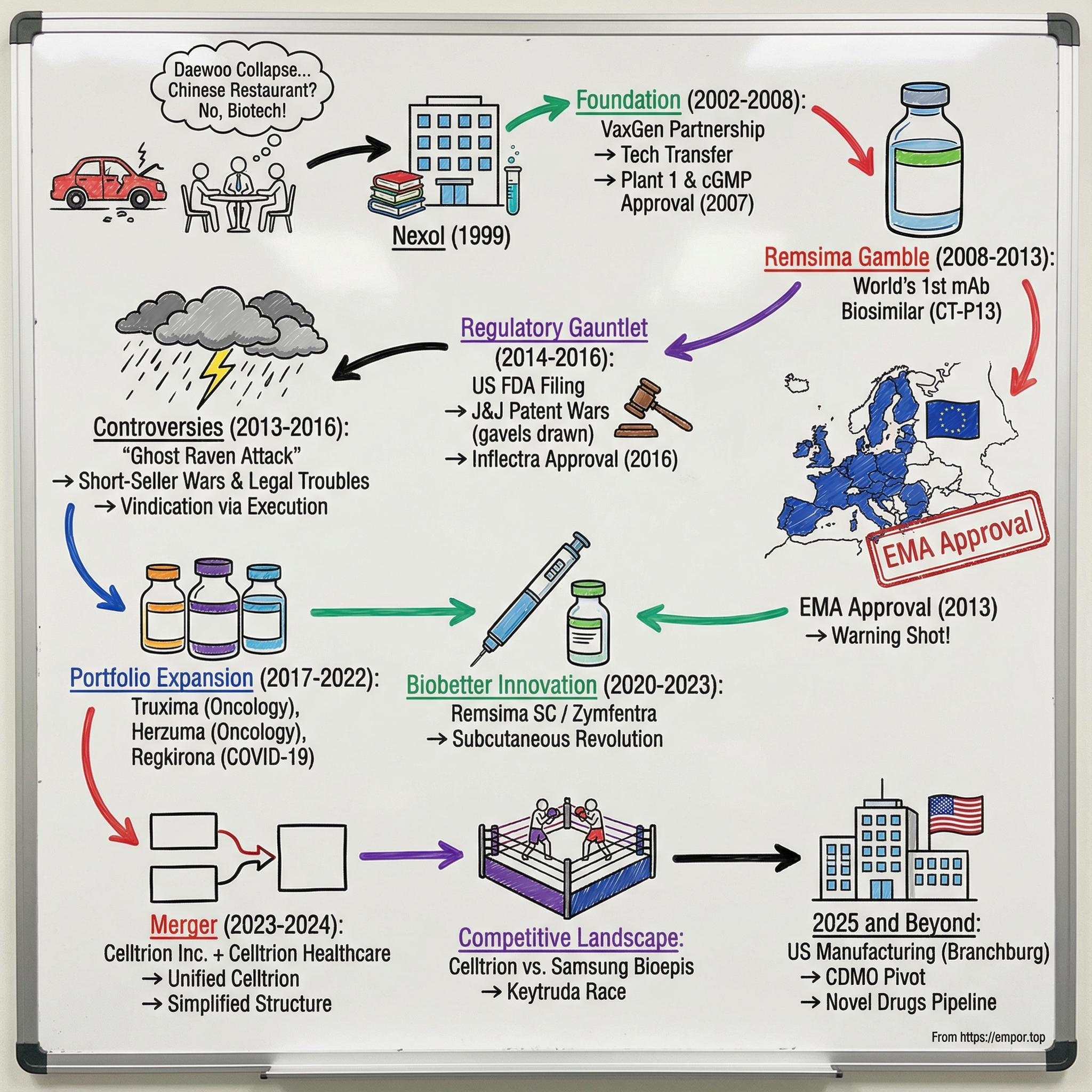

Picture a handful of former car salesmen huddled around a table in a small office in Incheon, South Korea. It’s 1999. The Asian financial crisis has just blown a hole through one of the country’s industrial titans—Daewoo Motors—and suddenly the safe paths are gone. Around them, ex-colleagues are making practical plans. Open a Chinese restaurant. Start over. Survive.

Seo Jung-jin and six junior staff members chose a different kind of survival plan: pick a fight with global pharmaceutical giants.

“A Chinese restaurant,” their younger coworkers said, “was the way to make a living after Daewoo went bankrupt.” Seo couldn’t accept that as the ceiling. So with just 50 million won ($44,400) in start-up capital, he and his team founded Nexol—the scrappy predecessor to what would become Celltrion.

Jump to today and that decision reads less like optimism and more like a controlled detonation. Celltrion posted record annual revenue of 3.56 trillion won ($2.48 billion) in 2024, up 63.5% from the year before. The company that began with auto-industry refugees and a pile of newspaper clippings about biotech now runs biopharmaceutical production at a scale few companies anywhere can match, with total capacity of 250,000 liters and end-to-end manufacturing capabilities.

Seo, the man who started with essentially no formal pharma background, became the richest person in South Korea. In 2021, he was named EY World Entrepreneur Of The Year—a mainstream stamp of approval on a career that, for years, looked to many insiders like recklessness disguised as ambition.

But the real story isn’t just personal. It’s structural.

The central question here is how an outsider from South Korea managed to break into one of the most fortified markets on earth—and what that breakthrough exposed about Big Pharma’s business model. Because when Celltrion’s Remsima received EU-wide marketing authorization on 10 September 2013—the world’s first approved monoclonal antibody biosimilar—it wasn’t just a product launch. It was a warning shot: even biologics, the high-moat, high-price, decades-long monopoly machines, were no longer untouchable.

This episode follows Celltrion from the ashes of Daewoo Motors, through regulatory gauntlets in Europe and the U.S., past short-seller attacks that threatened to crater the company, and into the merger that reshaped its corporate structure. Then we’ll look at what comes next—Celltrion battling Samsung Bioepis for global biosimilar leadership, while preparing for the looming prize fight around the $31 billion Keytruda market.

II. The Origin Story: From Coal Briquettes to Daewoo to Biotech

The Making of an Unlikely Pharmaceutical Mogul

Seo Jung-jin didn’t start with a family safety net or a childhood that pointed toward pharmaceuticals. He was born in Cheongju, South Korea, on October 23, 1957, into a household that ran a coal briquette business. It was the kind of work that kept the lights on, not the kind that built generational wealth.

So Seo did what ambitious, broke students have always done: he worked. While studying industrial engineering at Konkuk University in Seoul, he drove a taxi to pay his way through school. He would later earn an MBA from the same university, stacking credentials that made him employable in Korea’s rising corporate machine.

That machine is where he went next. Before Celltrion, Seo built a career across Samsung Electro-Mechanics, the Korea Productivity Center, and Daewoo Motors. At the Korea Productivity Center, he consulted for Daewoo Group, and eventually Kim Woo-joong—Daewoo’s chairman—handpicked him to advise Daewoo Motor.

It was a front-row seat to how large organizations actually operate: how they scale, how they negotiate, how they build supply chains—and, crucially, how they can still die.

The Daewoo Collapse—and the Fork in the Road

Then came the Asian financial crisis. Daewoo became one of the most dramatic corporate collapses of the era, and Seo—an industrial engineer working inside an automaker—lost his job along with thousands of others.

For many people, that kind of shock narrows your world. You look for stability. You take the closest respectable path. Seo saw the same instinct in his coworkers: start a small restaurant, find another safe job, keep your head down.

He couldn’t do it.

Instead, Seo latched onto an idea that barely anyone around him could spell, let alone execute: biotechnology. He wasn’t trained in science or medicine. He’d mostly encountered the field through newspaper articles. But he believed he could see the direction the world was moving. As he later put it at a forum hosted by the Federation of Korean Industries, “But I felt something is going to happen with it.”

That “something” would become his bet: biologic drugs were going to reshape medicine—and whoever could manufacture them at scale would have leverage, even against the biggest pharmaceutical companies on earth.

The Bootstrap Years

The earliest version of Celltrion wasn’t a lab with gleaming stainless steel tanks. It was Seo teaching himself an entirely new domain while trying to keep a company alive.

He read relentlessly—reportedly hundreds of medical textbooks—and even attended an anatomy class to understand how the human body worked. And he financed the effort however he could: by manufacturing ingredients needed for biosimilars, and then supplementing that with informal funding when traditional capital wasn’t available.

The corporate vehicle for all of this started as something far more innocuous. In 1999, Seo and his former Daewoo colleagues founded Nexol, Inc. (now Celltrion Healthcare Co., Ltd.) as a global business management consulting firm. On paper, it looked safe and ordinary. In reality, it was infrastructure: a way to build relationships, learn the market, and assemble a team while aiming at a much larger prize.

The ambition came with real risk. Early on, Seo nearly wiped out the company after investing heavily in contract manufacturing organization facilities tied to an HIV vaccine that ultimately failed in clinical trials. That kind of miss can end a young biotech outright.

But Celltrion survived because Seo’s larger takeaway wasn’t about the vaccine—it was about the factory. Manufacturing capacity, he realized, has value even when the molecule doesn’t. If the product fails, the plant can still run.

That lesson became the bridge from desperation to strategy, and it set up the next chapter: Celltrion’s move from scrappy outsider to world-class manufacturer.

III. Building the Foundation: CMO to Biosimilar Visionary (2002–2008)

The VaxGen Partnership: Technology Transfer as Strategy

In 2002, Seo found the kind of partner a would-be biopharma company in South Korea almost never got: an American biotech that actually needed what he could help provide.

VaxGen was working on an HIV vaccine called AIDSVAX and wanted manufacturing capacity. Seo and a group of South Korean investors had capital and, more importantly, urgency. Together, they formed a joint venture called Celltrion—reported at the time as a $120 million deal—built around the promise of producing more than 200 million doses a year.

Celltrion was founded in February 2002 in Incheon, South Korea. The structure mattered: Korean investors, including Seo’s Nexol, supplied the financing, while VaxGen supplied technical support and know-how. Specifically, VaxGen brought expertise in CHO (Chinese Hamster Ovary) cell-based monoclonal antibody production—the industrial workhorse process behind many modern biologic drugs.

This is the part that’s easy to miss if you only look at the vaccine outcome. The genius of the VaxGen deal wasn’t AIDSVAX. It was the technology transfer.

For Celltrion, getting that CHO cell culture capability was like skipping multiple levels in a video game. Instead of learning biologics manufacturing one painful iteration at a time, they were buying into a proven method, connected to the same lineage of techniques that had powered the biggest names in biotech. Seo wasn’t just starting a company. He was importing an operating system.

Building World-Class Manufacturing

By 2005, the bet was turning into steel and concrete. Plant 1—built for large-scale biologics production—was completed in July of that year, with 50,000 liters of capacity.

Then came the step that separates “we built a factory” from “the world will trust this factory.” In December 2007, Plant 1 received cGMP facility approval from the U.S. FDA.

That approval did more than check a regulatory box. It was a signal to the global industry that this wasn’t a local experiment. A facility in Incheon—built and run by a team that had started out in an entirely different industry—could meet the same manufacturing standards expected of the world’s top biologics producers.

Meanwhile, the ownership story was shifting too. In mid-2006, VaxGen sold its stake in Celltrion to the other shareholders for $53.6 million. The stake was acquired by three related Korea-based entities—Nexol, Nexol Biotech, and Nexol Venture Capital—through an exclusive option VaxGen had granted in June 2006. In practice, that meant Seo and his Korean partners took control of a company that now had something incredibly hard to build from scratch: world-class biologics manufacturing capability.

Celltrion would later say it secured FDA and European Medicines Agency cGMP certifications across its biopharma production facilities, and it has claimed it was the first in Asia to operate FDA cGMP-certified animal cell culture facilities.

The Strategic Pivot to Biosimilars

The original product plan—VaxGen’s HIV vaccine—ultimately failed in clinical trials. But Celltrion didn’t die with it, because the real asset was never the vaccine. It was the plant, the process, and the people who now knew how to run them.

With manufacturing in place, Seo could finally point the company at the opportunity he’d been circling for years: biosimilars.

Biosimilars aren’t like traditional generics. You’re not copying a simple chemical formula. You’re recreating a biologic—a complex medicine made in living cells—so closely that regulators, doctors, and patients can trust it as effectively the same therapy. The science is harder, the standards are higher, and the manufacturing is the moat.

By 2008, the timing was lining up. Major biologics were approaching patent expiry in Europe and Japan—drugs like Remicade (infliximab), Rituxan (rituximab), and Herceptin (trastuzumab). These weren’t niche products. They were blockbusters throwing off billions in revenue. And crucially, while small-molecule drugs might see a swarm of generic competitors the moment exclusivity ends, biosimilars would be limited by capability. Only a handful of companies in the world could reliably make them.

Seo’s conviction was simple: if Celltrion could be early—and credible—it could win a spot at the table with the giants.

That same year, Seo led the company to an initial public offering. Celltrion’s IPO on the South Korean stock exchange brought in the capital to expand R&D and accelerate the push into biosimilars. The factory had proved it could meet the world’s standards. Now the question shifted from “Can we manufacture?” to the much bigger challenge:

Could a Korean newcomer persuade regulators—and then physicians and patients—that its biologic lookalikes belonged in the same clinics as the originals?

IV. The Remsima Gamble: Creating the World's First mAb Biosimilar (2008–2013)

Why Infliximab (Remicade)

Once Celltrion committed to biosimilars, it had to pick its first target. This was the moment where you learn whether a company is playing for singles… or trying to change the game.

Celltrion chose Remicade, Johnson & Johnson’s blockbuster autoimmune drug. At the time, it was doing more than $6 billion a year globally—an enormous prize. And it sat in a sweet spot strategically: it was among the earlier wave of major biologics facing patent expirations in Europe, meaning a credible biosimilar could actually get on the field.

But Remicade wasn’t an easy first swing. It’s a chimeric monoclonal antibody—part mouse, part human—manufactured in living cells. That complexity is exactly why biologics are such durable franchises. If your product drifts from the reference in the wrong way, you don’t just risk a bad batch. You risk triggering immune reactions in patients. That’s not a business problem; that’s an existential one.

Celltrion’s bet was that the thing it had spent years building—manufacturing excellence, hard-earned know-how, and the discipline of operating at global standards—could carry it through. Internally, the program was CT-P13. Commercially, it would become Remsima.

Global Clinical Trials—A First for Korea

To pull this off, Celltrion needed more than ambition. It needed money, credibility, and the ability to run global trials at a scale Korean pharma had never attempted.

At home, plenty of investors weren’t buying it. A biosimilar monoclonal antibody program sounded like science fiction coming from a company that, not long before, had been an auto-industry exile. But overseas capital saw something different. Temasek invested a combined 357.4 billion won across 2010 and 2013. One Equity Partners—the private merchant banking arm of JPMorgan Chase—put in 250 billion won in 2011.

Those checks weren’t just funding. They were validation that serious institutions believed Celltrion could execute. One Equity Partners, in particular, didn’t drift into deals like this casually; it did deep diligence before committing. It also made an initial investment into Celltrion Healthcare in January 2012.

The cash powered what mattered most: the clinical package that European and U.S. regulators would require. And operationally, Celltrion was scaling in parallel. In October 2011, it completed Plant 2, adding 90,000 liters of capacity.

Then came a first official stamp. In July 2012, Remsima received approval from Korea’s MFDS.

That was a meaningful milestone—but it wasn’t the one that would change the world. The real gatekeeper was Europe.

The EMA had built a tough framework for biosimilar monoclonal antibodies. It wasn’t enough to show you’d made something that looked similar in a lab. You had to prove—clinically—that it behaved the same way in the body, with comparable efficacy and safety. No one had yet proven they could clear that bar for a monoclonal antibody biosimilar.

The Historic 2013 EMA Approval

In September 2013, Celltrion did it.

CT-P13—developed and manufactured by Celltrion—became the world’s first monoclonal antibody biosimilar approved by the European Commission. It was approved under the trade name Remsima®.

It’s hard to overstate what that meant. This wasn’t just “a Korean company got a drug approved.” It was the opening of a market category many incumbents had treated as theoretical. The decision told every executive team in Big Pharma: the highest-margin, highest-moat biologics weren’t protected forever. A determined, technically capable entrant could replicate them closely enough to satisfy the world’s most demanding regulators.

Remsima later launched in major EU countries in early 2015. But the moment of approval was the inflection point—the instant biosimilar monoclonal antibodies stopped being a PowerPoint story and became an operating reality.

And Celltrion had gotten there first. The company that began with former Daewoo employees had beaten much larger, richer rivals to one of the most coveted achievements in modern drug development. Remsima was approved for autoimmune diseases including Crohn’s disease and arthritis, and it set up what came next: Celltrion’s push beyond one product, into a pipeline meant to prove this wasn’t a one-time stunt—it was a new kind of pharmaceutical company.

V. The Regulatory Gauntlet: Cracking the US Market (2014–2016)

The FDA Filing—and Why It Mattered

Europe had validated Remsima. But the U.S. was the real fortress.

America’s drug market was the biggest in the world, and biologics pricing there was in a different league from Europe. If Celltrion could win even a slice of Remicade’s U.S. business, it wouldn’t just be a nice expansion—it would change the company’s trajectory.

So in August 2014, Celltrion filed its U.S. biosimilar application for CT-P13 (infliximab). The company said it was the first monoclonal antibody biosimilar application filed in the United States.

That detail matters because the U.S. didn’t just have a different regulator—it had a different rulebook. The FDA’s biosimilar pathway, known as 351(k), came from the Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act of 2009 (BPCIA), a piece of legislation that created a formal route for biosimilars in America. But no one had yet proven that route could reliably handle a complex monoclonal antibody like infliximab. Celltrion wasn’t just applying for approval. It was stress-testing the system.

The Patent Wars with J&J

Regulatory approval was only half the battle. The other half was Johnson & Johnson.

Even as key patents approached expiration, J&J had built a dense portfolio of secondary patents around Remicade—covering things like manufacturing processes, formulations, and various uses. The practical goal was simple: delay biosimilar competition for as long as possible, even if the science and regulators said a competitor was ready.

What followed was years of litigation and uncertainty. J&J argued Celltrion couldn’t launch because patent protections still applied. Celltrion fought back, challenging the patents and pressing the case that they were invalid or didn’t block a biosimilar launch. It was expensive, distracting, and unavoidable. This is what entering the U.S. biologics market looks like when you’re taking revenue away from one of the most successful franchises in pharma.

The 2016 Breakthrough

In April 2016, the FDA approved CT-P13 under the trade name Inflectra®.

In the U.S. and certain other territories, Pfizer held exclusive commercial rights to Inflectra. Like Remicade, it’s administered intravenously.

The timing told its own story. The FDA’s approval arrived almost three years after Europe’s authorization, underscoring how differently the two systems treated biosimilars. Europe had been more willing to lean into biosimilars as a cost-saving mechanism. The U.S. moved slower and demanded more process, more evidence, and more caution.

For Celltrion, the commercialization decision mattered almost as much as the approval. Going it alone in the U.S. would have meant building an American sales and reimbursement machine from scratch—an enormous lift. Partnering with Pfizer solved that overnight. Pfizer brought deep relationships, scale, and one of the most experienced sales forces in the industry. Celltrion brought the product.

From there, the U.S. launch came quickly. Inflectra was approved in April 2016 and began sales in the U.S. in November 2016. Along the way, Celltrion hit a symbolic milestone: by October 2016, the company had reached 1 trillion won in cumulative Remsima exports.

That number captured what made Celltrion different. It wasn’t trying to look like a traditional pharma giant, building a massive global sales empire country by country. It was building world-class development and manufacturing, then using partnerships to reach patients worldwide—staying capital-efficient while competing in markets that usually require enormous commercial muscle.

VI. The Short-Seller Wars & Controversies (2013–2016)

The Ghost Raven Attack

In March 2016—just weeks before the FDA would approve Celltrion’s infliximab—an anonymous report hit the market like a grenade.

A group calling itself “Ghost Raven Research” published a short-seller dossier arguing that one of South Korea’s most valuable biotech companies was, essentially, a mirage. It accused Celltrion of “massive accounting fraud,” and claimed that roughly “90 percent” of the company’s revenue had been fabricated.

The core of Ghost Raven’s argument wasn’t about the science. It was about the plumbing.

They pointed to Celltrion’s corporate structure—separate entities for manufacturing (Celltrion), distribution (Celltrion Healthcare), and domestic sales (Celltrion Pharm)—and alleged that it existed less to operate efficiently and more to manufacture the appearance of sales. Most of the revenue, they argued, came from selling products to its own affiliate, Celltrion Healthcare, rather than to “end consumers.” They also claimed the company was sitting on large inventories of unsold drugs.

To make it sting, the report drew a line back to Daewoo Motors, where some Celltrion executives had worked—invoking the memory of Korea’s most famous corporate collapse at the exact moment Celltrion was trying to cement credibility in the U.S.

The Company's Defense

Celltrion didn’t treat the report as an honest critique. It treated it as a trade.

Ghost Raven’s own disclaimer said the report was prepared for profit through short-selling, and that Ghost Raven Research and its clients or investors “has a short position” and “therefore stands to realize significant gains” if the stock declined.

Celltrion’s response leaned hard into that point. “We believe that the short sellers of Celltrion stocks must have taken huge losses, and they are circulating these false reports to recover their damages,” the company said.

But the more compelling part of Celltrion’s defense was practical: if the business was fake, how did it get this far?

By then, Remsima—the world’s first monoclonal antibody biosimilar—had been approved in dozens of countries and was being sold internationally through established partners, including Pfizer and Mundipharma. Celltrion framed the attack as incompatible with reality: regulators had audited the company’s data and manufacturing, and global partners had done their own diligence before tying their names to the product.

Legal Troubles and Vindication

The short-seller war wasn’t the only pressure point. In 2014, Seo was summoned by prosecutors over allegations of stock price manipulation—an episode that some observers interpreted as retaliation for his public criticism of financial authorities. He was later fined 300 million won for violating laws on capital markets and financial investments.

And the stress wasn’t just legal. In 2013, Seo even made a surprise announcement that he would sell the company to foreign competitors, saying he was exhausted by the relentless short-selling attacks from groups such as hedge funds.

All of it exposed a real vulnerability: Celltrion’s structure created room for suspicion. With interrelated entities buying and selling among themselves, critics could paint ordinary transfer pricing and distribution mechanics as something darker. Even if the business was sound, the optics were messy—and in public markets, optics can become their own kind of risk.

Still, the clearest rebuttal wasn’t a press release. It was continued execution: more approvals, expanding partnerships, and real sales in real markets.

One analyst at HMC Investment and Securities, citing industry sources, argued that the Ghost Raven episode also reflected fear—specifically, anxiety about a foreign-developed biosimilar pushing into the U.S. “In fact, there were considerable market fears and resistance inside the U.S. for the U.S. government endorsing the market entry of the biosimilar product developed by a foreign company,” he said, adding that rumors circulated about attempts to curb Celltrion’s market value ahead of the FDA decision in April.

Whether it was a coordinated effort or simply opportunistic short-selling, the timing told you what was at stake: Celltrion was knocking on the door of the biggest biologics market in the world—and plenty of people had reason to prefer that the door stayed shut.

VII. Portfolio Expansion: Beyond Remsima (2017–2022)

Truxima and Herzuma—The Oncology Push

Once Remsima proved Celltrion could build a world-class biosimilar and actually sell it, the obvious question became: what’s next?

The answer was to go after a tougher neighborhood—oncology. Over the next few years, Celltrion rolled out a subcutaneous (SC) formulation of infliximab (Remsima SC) and moved into biosimilars of rituximab and trastuzumab.

The milestones came fast. In November 2016, Truxima was approved by Korea’s MFDS. In February 2017, it won approval from the EMA. Then, in February 2018, Celltrion listed on KOSPI—and that same month, Herzuma was approved by the EMA.

Truxima (a rituximab biosimilar) and Herzuma (a trastuzumab biosimilar) took aim at Roche’s oncology franchise. Rituxan and Herceptin were two of the most successful cancer drugs ever created, together generating more than $12 billion a year at their peak. For Celltrion, even a small slice of that kind of market would be meaningfully bigger than “nice growth.” It would be a new scale of company.

But the oncology push wasn’t just about revenue. Cancer medicines come with a different level of scrutiny. Oncologists are understandably cautious about switching therapies for life-threatening diseases, and skepticism toward biosimilars tended to run higher. Celltrion’s ability to get Truxima and Herzuma across the line—and into real-world use—signaled that its manufacturing and quality systems could meet the bar in one of medicine’s most demanding specialties.

The Expanding Portfolio

By the early 2020s, Celltrion no longer looked like a company built around a single breakthrough. It looked like a portfolio machine.

At that point, Celltrion USA had six biosimilars on the U.S. market—covering infliximab, rituximab, trastuzumab, adalimumab, and bevacizumab—alongside Zymfentra, a novel product enabling subcutaneous administration of its infliximab biosimilar (Inflectra, Remsima).

Commercially, the company started showing it could win not only with regulators, but also with pricing and distribution. In Europe, Yuflyma’s penetration rose steadily. In the U.S., Celltrion used a dual wholesale acquisition cost (WAC) pricing strategy to sell into both public and private insurance channels, helping drive a 2.4-fold sales increase to 349.1 billion won in 2024.

Vegzelma was the clearest proof point of marketplace execution. In Europe, it became the market leader with a 29 percent share—outpacing both the originator and rival biosimilars—and revenue jumped 4.5-fold year over year to 221.2 billion won. That’s what it looks like when approvals turn into adoption.

The COVID-19 Pivot

Then the pandemic hit, and Celltrion had a chance to show it was more than a biosimilar company.

In South Korea, Celltrion received conditional marketing authorization from the MFDS for Regkirona (regdanvimab, also known as CT-P59), an anti-COVID-19 monoclonal antibody. According to an MFDS spokesman speaking to BioWorld, it was the first COVID-19 antibody treatment developed in South Korea to receive approval.

Europe followed. The European Commission granted marketing authorisation after a positive opinion from the EMA’s Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use. The authorization covered adults with COVID-19 who did not require supplemental oxygen and who were at increased risk of progressing to severe disease.

With that final authorization, Regkirona became the first monoclonal antibody drug—along with Ronapreve—approved in the EU for the pandemic, and it marked the first new medicine independently developed by a South Korean company to make inroads into the European market.

Strategically, that mattered as much as the product itself. Celltrion had built its reputation by proving it could replicate the world’s hardest-to-make drugs. Regkirona was different: it was an original therapeutic. It was a signal that the company’s manufacturing and clinical engine could support novel drug development—not just biosimilar replication.

VIII. The Biobetter Innovation: Remsima SC / Zymfentra (2020–2023)

What Is a "Biobetter"?

Pharma doesn’t invent new categories lightly. But Celltrion’s next move didn’t fit neatly into the old ones.

A biosimilar is designed to be highly similar to an existing biologic, with no clinically meaningful differences from the original. A biobetter is different: it starts with a known biologic and intentionally changes it to make it better—improving outcomes, tolerability, or simply making treatment easier for patients.

Zymfentra—also marketed as Remsima SC in some international markets, including the European Union, Brazil, and South Korea—lands in a particularly unusual corner of that definition. It’s not a biobetter of the originator drug. It’s a biobetter built on top of Celltrion’s own biosimilar, Remsima.

And the “better” part wasn’t some minor tweak. It was a rethink of how patients receive infliximab. Remicade and the original Remsima were IV infusions, which meant scheduling time at an infusion center and sitting for hours. With Remsima SC, the same core therapy could be delivered by a subcutaneous injection—something patients could do themselves at home in minutes.

The Subcutaneous Revolution

In the U.S., the FDA approved Celltrion USA’s Zymfentra (infliximab-dyyb) as a novel drug—and notably, as the world’s first and only subcutaneous infliximab product.

That regulatory label mattered. In Europe, the EMA allowed Celltrion to pursue the subcutaneous formulation as a line extension. In the U.S., the FDA required a standalone Biologics License Application, treating it not as a biosimilar add-on but as its own new product.

Commercially, the difference is enormous. Zymfentra’s intellectual property position stretches far beyond what a biosimilar alone could support: patent protection runs through 2037 for its dosage form, and through 2040 for its route of administration. In other words, Celltrion wasn’t just defending a biosimilar franchise—it was creating a new one.

The clinical results supported the bet. In one study, 438 patients who had responded after induction were randomized at Week 10. By Week 54, the clinical remission rate was significantly higher with Zymfentra (43.2%) than with placebo (20.8%).

Why This Matters Strategically

This was Celltrion stepping over a line. Biosimilars proved the company could match the world’s best. A biobetter signaled it could improve on what already existed—and create durable product differentiation at a moment when biosimilar markets were getting more crowded.

Celltrion positioned Zymfentra as a flagship for that evolution, and it backed the strategy with a very American kind of execution: access.

The company secured formulary listings with the three major pharmacy benefit managers in the U.S., plus additional medium and smaller insurers. The result was scale—over 95% insurance coverage in the U.S.—and a clear sign that Celltrion wasn’t just getting products approved in America anymore. It was learning how to win inside the system that actually determines what gets used.

IX. The 2023–2024 Merger: Creating the Unified Celltrion

The Complex Corporate Structure Explained

From the outside, Celltrion’s biggest self-inflicted wound wasn’t scientific risk or regulatory uncertainty. It was the org chart.

For years, the group operated through a tangle of related entities that repeatedly confused investors and invited suspicion—especially after the short-seller attacks. At the center sat Chairman Seo. He held 98.1% of Celltrion Holdings Co., which owned major stakes in both Celltrion Inc. and Celltrion Healthcare—about 20.1% and 24.3%, respectively. Celltrion Inc., in turn, held a 54.8% stake in Celltrion Pharm. After the merger of Celltrion Inc. and Celltrion Healthcare, Celltrion Holdings became the largest shareholder of the combined company, holding 21.5%.

Historically, there were reasons this structure formed: manufacturing in one entity, global sales in another, domestic distribution in a third. But over time it created structural friction. Inter-company transactions made the financials harder to read. Revenue flowed between affiliates, giving critics an easy narrative. Even supportive shareholders had to work too hard to understand what the business was actually earning as one system.

The irony was that Celltrion had spent two decades proving it could meet the world’s highest standards in manufacturing and regulation—while its corporate structure made it look, at times, like it was still a complicated local conglomerate.

The Rationale for Merger

In Celltrion’s own telling, integration was the next stage of survival.

In a statement, the company said that after merging with Celltrion Healthcare and chemical pharmaceutical affiliate Celltrion Pharma, it expected combined sales to reach 12 trillion won ($8.87 billion) by 2030. The logic was straightforward: unify the full cycle from development to sales, improve cost competitiveness, and secure the kind of large-scale investment resources needed for new drugs and new modalities.

Seo framed it even more bluntly. Celltrion, he said, started as a CMO, then moved into biosimilars, then into new drugs. But the market had become too competitive for a split-brain organization. Only companies that can develop, produce, and sell their own drugs end-to-end, he argued, would survive.

And he wasn’t wrong about the incentive structure. The more Celltrion moved from “biosimilar manufacturer” to “global pharma contender,” the more damaging it became to have manufacturing, marketing, and sales separated by corporate walls—walls that also happened to amplify accounting and governance skepticism.

Execution and Aftermath

The first and most important step was combining the two entities that the market most associated with the “optics problem”: Celltrion Inc. and Celltrion Healthcare.

On Oct. 23, 2023, at extraordinary general meetings in Incheon, shareholders overwhelmingly approved the merger agreement between the two companies. Celltrion said 97.04% of attending shareholders at Celltrion Inc. voted in favor, and 95.17% of attending shareholders at Celltrion Healthcare did the same.

By late December 2023, Celltrion announced it had completed the merger process. In a regulatory filing, the company said its board approved the merger, with Celltrion Healthcare dissolved into the combined entity. Internally, it reorganized around three pillars: manufacturing and development, global sales, and general management—essentially turning what had been a multi-company relay race into one organization with a single finish line.

The Celltrion Pharm Merger—That Wasn't

But the broader plan—to roll all three major affiliates into one—hit a wall.

A survey of shareholders of Celltrion and Celltrion Pharm showed that 70.4% of Celltrion’s shareholders voted against the merger. The company ultimately scrapped the plan, citing opposition from minority shareholders. The objections were specific and financial: critics argued that Celltrion Pharm’s enterprise value, reflected in its market capitalization, was significantly inflated, and that the proposed combination would undermine Celltrion shareholders’ value.

Among those who opposed the deal, 58% said they were dissatisfied with the merger ratio, while 21% said the merger offered limited benefits. Many emphasized that any future attempt would require a reassessment of the merger ratio.

The rejection revealed something important about Celltrion’s evolution. Even with Seo’s dominance at the center of the structure, minority shareholders could—and would—block a transaction they believed was tilted against them. It was a real check on founder power, and a sign that the company’s long-running push toward clearer governance was real, even if it was still unfinished.

X. The Competitive Landscape: Celltrion vs. Samsung Bioepis

The Korean Biosimilar Duopoly

If Celltrion’s early years were defined by proving “a Korean company can do this,” the next era was defined by a different reality: South Korea didn’t just produce one biosimilar champion. It produced two.

Today, the biosimilar map has a Korean center of gravity—Celltrion on one side, Samsung Bioepis on the other. Samsung Bioepis has racked up the larger count of approved products. Celltrion, meanwhile, has distinguished itself as the deal-maker. A GlobalData report put it plainly: because Celltrion is involved in so many partnerships, both globally and locally, it “leads the overall biosimilar deals landscape” in South Korea—and may have an edge in deal strategy versus other domestic players.

From a distance, the two companies can look like variations of the same playbook: world-class manufacturing, strong government support for biotech, and commercialization partnerships that opened doors in Europe and the U.S. But the rivalry is real, and it’s shaped the pace of the global market. They don’t just compete product-by-product; they compete on execution.

That competition shows up in the scoreboard that matters most in the U.S.: FDA approvals. With its latest approvals, Celltrion reached 10 FDA-approved antibody biosimilars—tying Samsung Bioepis and putting both companies at the top of the U.S. antibody biosimilar market by sheer count. In the process, Celltrion moved past Amgen, which had previously shared that top spot alongside Samsung Bioepis.

Speed as Competitive Advantage

In biosimilars, speed isn’t a vanity metric. It’s a weapon.

Clinical development takes time, but the Korean companies have gotten unusually good at compressing timelines—often beating long-established Western competitors. For Stelara-referencing biosimilars, Celltrion and Samsung completed Phase 3 testing in about a year and a half, faster than Amgen’s timeline. Samsung also moved quickly on Soliris-referencing development, finishing Phase 3 in a little over two years—well ahead of Amgen. And for a Herceptin-referencing product, Samsung again finished Phase 3 trials sooner than both Amgen and Celltrion.

The takeaway isn’t that every program is faster in every case. It’s that Celltrion and Samsung Bioepis have built clinical development machines that can run at, and sometimes above, the pace of the companies that invented the biologics era. That translates into earlier launches, more time in-market before the next wave of competitors arrives, and—when the market is big enough—real strategic leverage.

The Keytruda Race

Now that machine is being pointed at the biggest target in sight: Keytruda.

Celltrion and Samsung Bioepis are accelerating their Keytruda biosimilar efforts as the industry positions for Merck’s blockbuster to approach patent expiration. Keytruda (pembrolizumab) is a third-generation immune checkpoint inhibitor used across a wide range of cancers, including non-small cell lung cancer, melanoma, and head and neck cancers. Mechanistically, it targets the PD-1 pathway—blocking PD-1 on T cells so tumors can’t shut down the immune response through PD-L1 interaction. It’s a therapy with more than 30 approved indications worldwide, which is part of why it has become so commercially dominant.

Celltrion’s latest update was that it received approval from South Korea’s Ministry of Food and Drug Safety to begin a Phase 3 clinical trial for its Keytruda biosimilar candidate, CT-P51.

Samsung Bioepis is sprinting too. Its candidate is SB-27, and the company has used a global “overlapping” strategy—running Phase 1 and Phase 3 trials concurrently. In biosimilars, that kind of overlap is permitted specifically to reduce time-to-market, and Samsung is using every tool available to move faster.

With Keytruda generating more than $31 billion a year, the prize is obvious. A meaningful share of pembrolizumab doesn’t just add revenue—it can define leadership in biosimilars for the next decade. And this is what makes the Celltrion–Samsung rivalry so consequential: it’s not a local competition anymore. It’s a race to set the terms of the post-Keytruda world.

XI. 2025 and Beyond: The CDMO Pivot and U.S. Manufacturing

The Eli Lilly Acquisition

After spending two decades proving it could manufacture at global standards, Celltrion made a move that signaled a new phase of ambition: it bought a factory in America.

Celltrion confirmed it agreed to acquire Eli Lilly and Company’s plant in Branchburg, New Jersey, for about 460 billion won ($330 million). The property spans roughly 150,000 square meters (about 37 acres) and includes four buildings—manufacturing space, an R&D center, storage—and, importantly, room to grow, with about 36,000 square meters of vacant land.

This wasn’t just a real estate deal. It was a strategic shortcut. Once Celltrion completes additional investment, it expects the Branchburg site’s production capacity to reach about one and a half times that of Celltrion’s second plant in Incheon, which has 90,000 liters of capacity.

The acquisition also solves a problem that suddenly loomed large: policy risk. Washington had warned of pharmaceutical import duties that could rise as high as 250% on foreign-made medicines. That threat was serious enough that Celltrion had already shipped two years’ worth of inventory to the U.S. and expanded contracts with local contract manufacturers. Owning a U.S. production base reduces that exposure—and does it at a fraction of the time and cost of building from scratch.

Celltrion described the deal as its most significant strategic move since its founding. “Compared with building a new plant, we save roughly six years,” Seo said.

And the company didn’t wait long to show it meant business. Two months after buying the site, Celltrion said it would invest up to 700 billion won ($478 million) more to upgrade the Branchburg facility—explicitly framing the decision as a response to U.S. tariff policy.

The CDMO Opportunity

The Branchburg plant isn’t just about making Celltrion’s own drugs closer to U.S. patients. It’s also a platform for a second business line: contract development and manufacturing.

With the acquisition, Celltrion said it gains three clear advantages: eliminating tariff-related risk, reducing geopolitical uncertainty by diversifying manufacturing locations, and expanding contract manufacturing (CMO) opportunities inside the U.S. In practical terms, Branchburg gives Celltrion a credible onshore footprint it can use to win work from other pharmaceutical companies—especially as demand for U.S.-based production grows.

That CDMO strategy adds a new dimension to Celltrion’s model. Instead of relying only on the success of its own biosimilars and new drugs, it can generate revenue by manufacturing for others. Done well, that helps keep facilities fully utilized, smooths revenue swings, and gives Celltrion visibility into emerging therapeutic areas it may later pursue with its own biosimilars—or even original medicines.

Growth Targets and Pipeline

Celltrion is pairing this manufacturing expansion with an aggressive product plan.

With its biosimilar lineup established at 11 products, the company said it is targeting 5 trillion won in revenue this year. Looking out to 2030, Celltrion plans to expand to a 22-product biosimilar portfolio, with pipeline candidates that include biosimilars for Ocrevus, Cosentyx, Keytruda, and Darzalex. In parallel, it outlined a clinical roadmap to submit investigational new drug (IND) applications for 13 novel drug candidates by 2028.

In 2024, Celltrion said it achieved its goal of building a portfolio of 11 biosimilar products a year ahead of its 2025 target—positioning the company to broaden global access to essential treatments by offering lower-cost alternatives with comparable efficacy to originator drugs.

XII. Investment Considerations and Competitive Analysis

Porter's Five Forces Analysis

Threat of New Entrants (Moderate): Biosimilars look attractive from 30,000 feet, but they’re brutally hard up close. You need sophisticated manufacturing, regulatory know-how, and enough capital to run serious clinical trials. Those requirements keep most would-be competitors out. Still, the walls are slowly lowering as regulators clarify the pathways and more companies build experience—especially newer biosimilar developers in India and China.

Supplier Power (Low to Moderate): Celltrion’s vertically integrated setup limits how much leverage suppliers can exert. The company still depends on raw materials for cell culture and specialized manufacturing equipment, and some niche suppliers can hold firm on pricing. But at Celltrion’s scale, it has meaningful negotiating power.

Buyer Power (High): In biosimilars, the buyers are sophisticated and concentrated. Pharmacy benefit managers, hospital systems, and government programs can force competition by putting Celltrion, Samsung Bioepis, and other players into direct bidding wars. That’s great for access and volume, but it caps margin expansion even when unit sales rise.

Threat of Substitutes (Moderate): The biggest substitute isn’t another biosimilar—it’s the next generation of medicine that makes the original biologic less relevant. In autoimmune disease, for example, oral JAK inhibitors can reduce reliance on injectable biologics. Celltrion’s expanding pipeline, and its push into novel drug development, helps mitigate the risk, but it can’t eliminate it.

Competitive Rivalry (High): The rivalry with Samsung Bioepis is structural, not episodic. They chase many of the same reference products, fight in the same markets, and compete for the same payer and physician mindshare. That rivalry drives price pressure. The main relief valve is differentiation—like Celltrion’s subcutaneous formulations—but those advantages tend to be product-specific rather than portfolio-wide.

Hamilton Helmer's 7 Powers Framework

Scale Economies: Celltrion’s manufacturing scale—now reinforced by its New Jersey expansion—should translate into lower unit costs. But scale isn’t exclusive in Korea; Samsung Biologics and Samsung Bioepis also operate at enormous volumes, which limits how defensible this advantage is over time.

Network Effects: Minimal. Biosimilars don’t compound value the way platforms do; one doctor using a product doesn’t inherently make the product more valuable for other doctors.

Counter-Positioning: The clearest example is the biobetter strategy with Zymfentra. If an incumbent tries to match a subcutaneous option, it risks cannibalizing its own IV franchise. That creates real strategic friction for the originator. The limitation is scope: it’s powerful where it applies, but it doesn’t automatically extend across Celltrion’s whole lineup.

Switching Costs: Moderate and mostly behavioral. Physicians and hospitals tend to stick with what they know, and as real-world evidence accumulates for a biosimilar, that comfort becomes harder to dislodge. Celltrion’s long history with Remsima helps, particularly against newer entrants trying to win trust.

Branding: Stronger than you might expect for a company built on “similarity.” In Europe especially, Celltrion has earned credibility with prescribers and built equity around reliability and quality—reinforced by its “world’s first” monoclonal antibody biosimilar milestone. That reputation can influence preference and, at the margin, pricing.

Cornered Resource: Celltrion has valuable assets—early backing from Temasek, manufacturing know-how seeded by the VaxGen era, and deep regulatory experience—but none are truly exclusive. Competitors can develop similar capabilities given enough time and investment.

Process Power: This is arguably the most durable edge. Celltrion has repeatedly shown it can run development and trials quickly and efficiently, often faster and cheaper than Western peers. That kind of operational muscle accumulates over years, and it’s hard to replicate on demand.

Bull Case

Celltrion sits in a rare position: one of two Korean champions in a market where manufacturing quality and execution determine who survives. It has a track record of winning approvals, scaling a portfolio, and gradually expanding beyond pure biosimilars into differentiated products like Zymfentra and original therapeutics like Regkirona.

The Branchburg acquisition from Eli Lilly is strategically clean. It reduces exposure to potential U.S. tariff shocks and creates an onshore platform that could generate additional revenue through CDMO work. And if Celltrion executes in the next wave—especially with a successful Keytruda biosimilar—its growth profile could move meaningfully above what the market currently assumes.

Finally, the merger simplification matters. By eliminating the structure that fueled years of confusion and suspicion, Celltrion strengthened transparency, improved internal efficiency, and made the story easier for global investors to underwrite.

Bear Case

The global biosimilar market is getting more crowded, not less. As additional competitors—especially from India and China—gain approvals, pricing pressure is likely to intensify and margins could compress. Even within Celltrion’s legacy wins like Remsima and Truxima, first-mover advantages fade as more options hit formularies.

Keytruda is also not a guaranteed victory. Multiple heavyweight players, including Samsung Bioepis, are pursuing the same prize. Being second, or even first in a brutal price war, could still result in economics that disappoint versus expectations.

Geopolitics remain a persistent risk. The U.S. manufacturing footprint helps with tariff exposure, but it doesn’t erase broader trade uncertainty, especially for a Korean exporter operating in a world where U.S.–China tensions can reshape supply chains quickly.

And while CDMO is an attractive adjacency, it’s not an empty field. Samsung Biologics, Lonza, and other entrenched manufacturers already compete aggressively for contracts. Celltrion may have to concede on price to win share, which could limit profitability.

Key Performance Indicators to Watch

Zymfentra U.S. Market Share: Zymfentra is Celltrion’s most important proof point that it can win in the U.S. beyond classic biosimilars. Its uptake—relative to Remicade and other infliximab options—will reflect physician confidence, payer access, and the durability of the subcutaneous value proposition.

Gross Margin Trajectory: Post-merger efficiency is one of the biggest promises to shareholders. Celltrion reported that cost of goods sold fell meaningfully year over year in the fourth quarter, and it has guided toward further improvement by the end of 2025. The specific percentages matter less than the trend: whether margins continue to expand as the merged organization normalizes operations.

Keytruda Biosimilar Development Timeline: CT-P51’s Phase 3 progress is a strategic clock. Enrollment speed, trial completion, and filing timing will influence whether Celltrion is early enough to win meaningful share in what may become the largest biosimilar market opportunity ever. Delays—especially relative to Samsung Bioepis—could meaningfully change the long-term payoff.

XIII. Conclusion

Celltrion’s story breaks most of the rules people assume govern pharma. A group of auto-industry refugees—led by a former taxi driver turned executive who taught himself biology from stacks of textbooks—built the company that delivered the world’s first approved monoclonal antibody biosimilar. Along the way, they pushed through regulatory skepticism, absorbed short-seller attacks, and forced the incumbents to confront a new reality: even the most protected biologic franchises can be contested.

Seo Jung-jin has framed the company’s edge as cultural as much as technical: the ability to push through fear of failure and turn crisis into opportunity. In his view, that mindset also comes with a responsibility—especially in moments of national or global stress—for the industry to act in the public interest.

What Celltrion ultimately proved wasn’t just that biosimilars were possible. It proved the barriers that used to function like permanent walls—manufacturing complexity, regulatory mastery, and the ability to run credible global clinical trials—could be scaled by outsiders with enough focus and persistence. And once that happened, the ripple effects became unavoidable: sustained pricing pressure on originators, wider patient access, and biosimilars cemented as a permanent competitive force rather than a temporary anomaly.

Now comes the harder question: can Celltrion outgrow the identity it invented?

The next chapter—racing toward a Keytruda biosimilar, building a U.S. manufacturing footprint, and pushing further into novel drug development—will test whether it can become something closer to a full-spectrum global pharma company. The 2023 merger simplified the structure that had long clouded the story, but it didn’t simplify the battlefield. Samsung Bioepis is pushing from one side. Global price competition is compressing from the other.

For investors, that’s the trade. The opportunity is enormous, with a massive wave of biologics approaching patent expiry over the next decade. But capturing it demands relentless execution, real differentiation, and the discipline to keep winning as the field gets more crowded.

What began with Seo sleeping in a $70-a-night motel, hoping for a meeting with American biotech leaders, became one of Asia’s most valuable pharmaceutical enterprises. The journey from coal briquettes to biosimilars is done. The journey from biosimilars to enduring global leadership is still underway.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music