Techtronic Industries: The Cordless Revolution

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

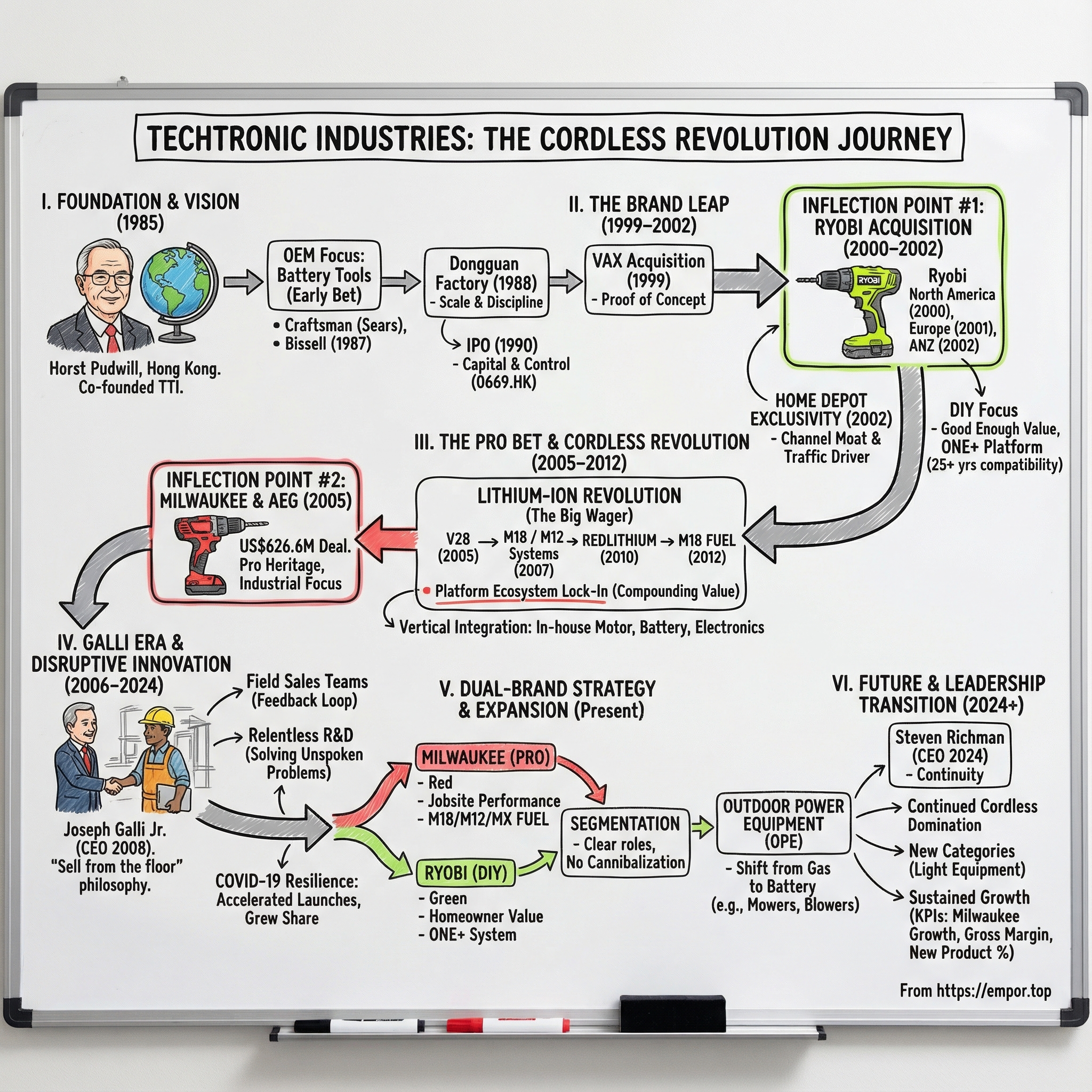

Picture this: it’s 2024, and somewhere on a construction site in Dallas, an electrician pulls a bright red Milwaukee drill from his belt, snaps in a lithium-ion battery, and drives screws overhead—no cord, no generator, no drama. Across town, a homeowner opens a lime-green Ryobi circular saw from Home Depot, clicks in the same battery she uses for her leaf blower, and starts cutting boards for a new deck.

Neither of them pauses to wonder who sits behind those brands. But there is one company behind both—and most Americans couldn’t name it. Techtronic Industries, or TTI, is a Hong Kong-based multinational that has quietly built one of the most striking industrial success stories of the twenty-first century.

In 2024, TTI delivered record sales of US$14.6 billion, growing 6.8% in local currency. It was founded in 1985 by Horst Julius Pudwill, a German entrepreneur who saw an opening in a new category at the time: battery-powered tools. Today, TTI designs, produces, and markets power tools, outdoor power equipment, hand tools, and floor care and cleaning products—serving everyone from professional tradespeople to DIYers.

The question that drives this story is simple, and a little mind-bending: how did a small Hong Kong OEM—originally making tools for other people’s brands—turn itself into a global powerhouse that bought century-old American icons like Milwaukee Tool and household names like Hoover… and then made them dramatically more successful than they’d ever been before?

The short answer is that TTI didn’t just build products. It built platforms. It helped pioneer cordless power tools powered by lithium-ion rechargeable batteries, and that bet didn’t just improve the tool—it rewired the economics of the industry.

So this story is about three things: the leap from OEM anonymity to owning brands people actually ask for by name; the lithium-ion wager that changed everything; and the kind of relentless execution that wins in a brutally competitive category. Since 2006, TTI has climbed from roughly sixth or seventh in global power tools to number two today.

Here’s how it happened.

II. Founding Story: The German Engineer in Hong Kong

Horst Julius Pudwill landed in Hong Kong in 1971—and essentially never left. “I liked Hong Kong instantly, it was a vibrant city, even at that time,” he later recalled from his office in Wan Chai.

He didn’t arrive as a starry-eyed entrepreneur. Pudwill was an engineer, German-trained, with a Master of Science in Engineering from the Technical College in Flensburg. He started his career at Volkswagen, and in the mid-1970s he was transferred to Hong Kong to take on a general manager role. It was a front-row seat to something most of his peers back in Europe didn’t fully appreciate yet: Hong Kong was becoming the connector between Western product know-how and Asian manufacturing power.

In the 1970s and 80s, that intersection was where the action was. Hong Kong wasn’t just a city; it was an operating system for manufacturing arbitrage—design, sourcing, production, export. Pudwill saw that the winners in consumer and industrial products wouldn’t just be the ones with the best engineering. They’d be the ones who could marry engineering discipline to world-class production at scale.

So in 1985, Pudwill and Roy Chi Ping Chung co-founded Techtronic Industries. At the start, TTI wasn’t a brand-builder. It was an OEM, making products for overseas labels. But Pudwill made an early, specific choice about what kind of OEM he wanted to be: he aimed TTI straight at battery-operated power tools—an odd focus at the time, because cordless tools were still new, expensive, and often disappointing.

Most power tools in 1985 were corded. Batteries were heavy, underpowered, and inconsistent. Still, Pudwill’s instinct was that cordless would eventually win—and that the companies who learned batteries, motors, and electronics early would have a compounding advantage later.

TTI’s first proof points came quickly. By 1987, it was producing Craftsman cordless power tools for Sears, and soon after it added cordless handheld vacuum cleaners for Bissell. Those contracts did two things at once: they taught TTI how to build to demanding specs, and they gave the young company a pipeline into the U.S.—the biggest, most profitable market for tools.

Sears mattered in particular. Craftsman was an American institution, and building under that name forced TTI to operate at a higher bar than a typical anonymous supplier. Then, in 1988, TTI opened its first manufacturing facilities in Dongguan, China. Dongguan would become central to the company’s ability to scale: capacity, process discipline, and the kind of manufacturing learning curve that makes each generation of product cheaper and better.

Pudwill remained at the center of the company for decades. He served as Chairman from the beginning and was also CEO until 2008. The Pudwill family has remained TTI’s largest shareholder, with the rest of the ownership largely held by institutional investors in North America and Europe.

That mix—family control plus public-market access—turned out to be a meaningful strategic advantage. It gave TTI room to think long-term, to invest ahead of the market, and to make acquisitions and technology bets that wouldn’t pay off in a single quarter. And in this story, those long bets are where everything starts to get interesting.

III. The IPO and OEM Grind (1990–1999)

In 1990, TTI went public on the Hong Kong Stock Exchange under stock code 0669. The IPO did two crucial things at once: it opened the door to public capital, and it preserved Pudwill’s ability to steer the company with a long time horizon. That combination—money plus control—would become a recurring edge.

Then came the 1990s: the unglamorous years that made everything else possible.

This was the decade of the OEM grind. TTI kept expanding its manufacturing footprint in Dongguan and got exceptionally good at the hard, repeatable work of building power tools at scale—hitting cost targets, meeting strict quality standards, and delivering reliably for demanding Western customers. The client roster grew to include some of the biggest names in home improvement retail.

But Pudwill also saw the trap. OEMs can be world-class operators and still end up with the worst economics in the value chain. If you make tools for someone else’s label, you get paid for manufacturing—and manufacturing margins are thin. The brand owner captures the premium. Even worse, you live with constant fragility: lose a major contract, and your factory utilization and profits can crater overnight.

So the strategy sharpened: TTI needed to stop being the invisible engine behind other people’s brands and start owning brands itself.

That leap is where many contract manufacturers fail. Buying established names takes real capital, yes—but it also takes integration skill, product vision, and the ability to run consumer-facing businesses where marketing, channel relationships, and innovation matter as much as production.

TTI’s first meaningful step in that direction came in 1999, when it acquired the Vax® brand and its floor care businesses in the UK and Australia. It wasn’t the biggest deal, but it mattered for what it proved internally: TTI could own a brand, keep the quality bar high, and operate it with professional management.

By the end of the decade, the pieces were finally on the table. TTI had scale in manufacturing, experience integrating an acquisition, and access to capital. The stage was set for a much bigger swing—one that would take the company from OEM anonymity to a portfolio of brands people actually recognized, and eventually, to the center of the cordless revolution.

IV. Inflection Point #1: The Ryobi Acquisition (2000–2002)

TTI’s first move into the big leagues came in 2000. It acquired Ryobi’s U.S. power tools business—and with it, the exclusive manufacturing and distribution rights to the Ryobi brand in North America. Overnight, TTI went from “the company behind the label” to the company holding a label people actually recognized.

And the way it did the deal tells you a lot about how Pudwill thought.

TTI didn’t try to buy all of Ryobi. Instead, it carved out exactly what it needed: the power tool operations in the markets that mattered most. It paid Ryobi’s Japanese parent $95 million for the U.S. subsidiary, gaining control of a major brand in the world’s most important tools market without taking on the whole global organization.

Then TTI kept going—methodically.

It bought Ryobi’s North American power tools business in August 2000. In August 2001, it acquired Ryobi’s European power tools business. And in March 2002, it added Ryobi Australia and Ryobi New Zealand. North America first, then Europe, then Australia and New Zealand—a geographic roll-up that turned Ryobi into a truly global platform inside TTI.

But the biggest prize from Ryobi wasn’t just the brand. It was the door it opened.

In 2002, TTI signed an exclusive distribution deal with Home Depot for Ryobi. That single agreement reshuffled TTI’s world: Home Depot became the company’s leading customer, ahead of Sears. And it reshaped Home Depot’s shelves, too. Under the partnership, Home Depot became the sole retailer authorized to sell Ryobi power tools and outdoor equipment across the United States, Canada, and Mexico.

This kind of exclusivity creates a very particular kind of bond. Home Depot got a differentiated, affordable brand competitors couldn’t match aisle-for-aisle. TTI got guaranteed shelf space and a direct line to the largest home improvement retailer in North America. It wasn’t just distribution—it was a long-term channel moat.

And Ryobi itself fit neatly into a strategy that was starting to come into focus. Ryobi was built for the DIY customer: homeowners, weekend warriors, people who wanted tools that were dependable and accessible, not necessarily jobsite-tough. It was “good enough” in the best sense—high value, easy to buy, easy to use.

That positioning mattered because it set up what came next. When TTI eventually bought a true professional brand, Ryobi wouldn’t get in the way. The customers, price points, and expectations were different. Instead of cannibalization, TTI would get something far more powerful: segmentation.

V. Inflection Point #2: The Milwaukee Bet (2005)

If Ryobi gave TTI a platform, Milwaukee gave it something even harder to buy: legitimacy with the pros.

In 2005, TTI paid $626.6 million to acquire Atlas Copco AB’s electric power tool and accessories business. That deal wasn’t just “buying Milwaukee.” It was a carve-out of the operations that made the brands work, including Milwaukee Electric Tool Corp. in the U.S. and Atlas Copco Electric Tools GmbH in Europe. Along with Milwaukee, TTI picked up AEG—one of Europe’s best-known power tool names.

Milwaukee’s story ran deep. The company traced its roots to 1924, when tool-and-die manufacturer A.H. Petersen built a portable, lightweight drill after Henry Ford asked for something that could replace the large, cumbersome units on Ford’s assembly lines. Milwaukee grew up in the world of industrial production, where tools weren’t lifestyle products—they were instruments of uptime.

But by the time TTI came calling, Milwaukee had already lived several corporate lives. It had been owned by Atlas Copco since 1995. And while Milwaukee was profitable, it wasn’t central to Atlas Copco’s identity. The Swedish conglomerate was focused on industrial compressors and mining equipment; power tools were a strategic side pocket. For TTI, Milwaukee wasn’t a side pocket. It was the future.

Horst J. Pudwill, then TTI’s chairman and CEO, framed the moment clearly: “We are pleased to add the Milwaukee and AEG brands of power tools and DreBo carbide drill bits to our growing family of global brands. With their 80-year histories, Milwaukee is one of the most widely respected brands in the professional contractor market segment.”

Still, the deal looked counter-intuitive from the outside. A Hong Kong company buying an American pro-tool icon? Plenty of observers assumed the playbook would be the usual one: move production, cut costs, squeeze margins, and slowly drain the brand of what tradespeople trusted.

That’s not what happened. Instead of stripping Milwaukee down, TTI doubled down—investing in R&D, sharpening the brand’s focus on specific trades, and pushing hard into cordless. What looked like a risky purchase would become the engine of TTI’s transformation.

VI. The Transformation: Lithium-Ion Revolution (2005–2012)

The lithium-ion bet was audacious. When TTI bought Milwaukee, the industry still ran on two defaults: cords, or nickel-cadmium batteries. Lithium-ion existed, but it wasn’t a jobsite technology yet. Nobody had cracked how to make it survive the realities of professional tools—high current draw, punishing heat and cold, and the kind of abuse that happens when something lives in the back of a truck.

Milwaukee decided to crack it anyway. In 2005—after years of development and a multi-million-dollar investment—the brand introduced what it described as the first lithium-ion cell design built for power tools, launching it with the V28™ battery system and a new line of cordless tools. It wasn’t a feature upgrade. It was a line in the sand: cordless could finally be more than a compromise.

Under the hood, the leap mattered because power tools don’t sip energy—they demand it in surges. Milwaukee’s patented lithium-ion technology centered on battery packs capable of producing an average discharge current of roughly 20 amps or more. That IP ended up protecting not only the early V28 and V18 lines, but also Milwaukee’s later M12 and M18 lithium-ion platforms—the families of tools that would come to define the brand.

But the most important innovation wasn’t purely chemical or electrical. It was strategic.

Milwaukee didn’t just roll out lithium-ion tools. It rolled out systems. The M18™ and M12™ Cordless Systems came with a commitment to users that still stands: Milwaukee would keep investing in new technology without forcing customers to abandon their existing platform. In other words, buy into M18 or M12 once—and Milwaukee wouldn’t leave you behind.

That promise changed buyer behavior. For a contractor, batteries and chargers are the real investment; tools are the add-ons. Once you owned an M18 battery ecosystem, every new Milwaukee purchase got easier, because it plugged into what you already had. Switching to another brand meant replacing the whole stack. Staying with Milwaukee meant compounding value.

Starting in 2007, the M18 system pushed that flywheel harder, combining proprietary battery, electronics, and motor technology into a cordless lineup designed to exceed professional demands. And critically, the ecosystem wasn’t a one-time snapshot; it was built to evolve. New battery technology could arrive while staying forward and backward compatible within the platform.

Then the pace picked up. Milwaukee kept pushing lithium-ion to the next level, introducing REDLITHIUM™ batteries in 2010 and M18 FUEL™ in 2012—each step aimed at making cordless feel less like an alternative and more like the default.

REDLITHIUM™, fully compatible with all M18™ cordless products, promised meaningful performance gains: more run-time, more power, and more recharges than competing lithium-ion options at the time. It also expanded where cordless could work, operating in extreme temperatures as low as 0°F/-18°C, running cooler, and delivering fade-free power.

Behind all of this was a choice that separated TTI from much of the industry: it didn’t want to be dependent on suppliers for the most important parts of the system. TTI made the strategic decision to design, develop, and manufacture its own battery packs and motors in-house, while building deep electrical engineering resources around electronic controllers. That vertical integration gave Milwaukee control of its critical components—and the ability to iterate faster, launch faster, and keep widening the gap.

VII. The Joseph Galli Era & "Disruptive Innovation" (2006–2024)

If Horst Pudwill supplied the vision and the capital, Joseph Galli Jr. brought the execution engine. And his arrival at TTI carried a little bit of poetic justice.

Galli came out of the heart of the American tool business. He joined Black & Decker in 1980 and spent more than 19 years there, rising to President of Worldwide Power Tools and Accessories. In 1992, he was responsible for launching DeWalt’s heavy-duty professional line—one of the most famous brand relaunches in the industry. DeWalt went from essentially nothing to a $1.4 billion business in just seven years. Galli had already demonstrated that he knew how to build a pro brand, win the channel, and turn products into a movement.

Then came the twist. Nearly nine years after he was fired as head of Black & Decker’s power tools division, Galli resurfaced—not at a smaller rival, but at the company that was becoming Black & Decker’s biggest problem. The industry press called it “poetic justice” as he was expected to be named CEO of Techtronic Industries, the Towson toolmaker’s largest competitor.

Between those chapters, he did something that didn’t fit the typical tool-exec résumé: he went to Amazon.com, where he served as President and Chief Operating Officer from 1999 to 2000. Then, in 2006, he joined TTI as CEO of Techtronic Appliances. Two years later, on February 1, 2008, he was appointed CEO and Executive Director of TTI.

What Galli brought to TTI wasn’t just a résumé. It was a worldview: sell from the floor, not from the boardroom. He ran with an intensely sales-focused philosophy and a work ethic that became part of company lore—spending more than three quarters of his time traveling, and sometimes showing up on weekends at a Home Depot to help salespeople demo products to customers.

That obsession with the point of sale shaped TTI’s go-to-market strategy. Instead of trying to “market” tools from headquarters, TTI invested heavily in field sales teams who lived inside the channel—working directly with distributors and end users. The payoff was a tight feedback loop: what customers asked for on the sales floor could feed product decisions, and new launches had a better shot at landing because they were built around real demand, not internal guesses.

And this is where “disruptive innovation” became more than a slogan. Under Galli, Milwaukee didn’t aim for small, incremental upgrades. The teams set out to solve problems that professional tradespeople felt every day but rarely articulated. The method was simple and relentless: get out to jobsites, stand next to electricians, plumbers, and mechanical contractors, and watch where time and effort were being wasted. Then build tools—and systems—that made the work faster, safer, and more productive.

VIII. The Dual-Brand Strategy: Milwaukee vs. Ryobi

TTI’s portfolio strategy is deceptively simple: Milwaukee for professionals, Ryobi for everyone else. Two lanes, two identities, two very different expectations—run by the same parent company, but deliberately kept distinct.

MILWAUKEE sits at the front of TTI’s professional tool portfolio. With global research and development headquartered in Brookfield, Wisconsin, the historic brand has built its reputation around innovation, safety, and jobsite productivity—tools designed for people who use them all day, every day. RYOBI, headquartered in Greenville, South Carolina, is aimed squarely at DIYers and remains a top choice for homeowners who want capability and value, without paying “pro” prices.

That geographic separation isn’t an accident. Milwaukee’s teams are steeped in American trades culture and the rhythms of the jobsite. Ryobi’s teams live closer to the home improvement customer—projects, weekend work, and the realities of buying tools at retail. Different customers lead to different product philosophies, which keeps the brands from drifting into each other’s territory.

In practice, the split is easy to see. MILWAUKEE is built for a professional clientele and is instantly recognizable in red. RYOBI—bright green—wins with individual users: DIYers, contractors on small jobs, and sub-contractors working in infrastructure. In the United States, TTI dominates the DIY segment with a 60% market share.

Those colors are more than design choices; they’re signals. Red on a construction site communicates “this is a pro tool.” Green in a garage communicates “this is a practical system for the home.” The brands become shorthand for identity, even though they come from the same corporate engine.

Ryobi’s clearest expression of that system mindset is the RYOBI 18V ONE+ platform. It has celebrated 25 years of battery compatibility and has grown to over 225 products that all share the same battery. The promise is straightforward: buy into ONE+ once, and you can keep expanding your set of tools without starting over.

That’s the ecosystem strategy, in its most consumer-friendly form. The 18V ONE+ battery fits every 18V tool Ryobi has made to this point. You can keep using older tools with today’s batteries, and you can keep working by swapping batteries between tools when one runs down.

The durability of that promise is what makes it so powerful. Backward compatibility for more than 25 years means a customer who bought a Ryobi drill in 2000 can pick up a Ryobi leaf blower in 2024 and stay on the same platform. And once you’ve accumulated a few batteries and a charger, switching brands isn’t just inconvenient—it’s expensive.

This good-better-best segmentation extends beyond Milwaukee and Ryobi. TTI also owns AEG, positioned between Ryobi and Milwaukee in Europe; Empire, which focuses on layout and measuring tools; and multiple floor care brands including Hoover, Oreck, Vax, and Dirt Devil. The point isn’t to mash everything together—it’s to cover the market with clear roles, so each brand can win its segment without confusing the customer.

IX. The Home Depot Partnership: A Symbiotic Relationship

If Ryobi was the key that unlocked the U.S. consumer market, Home Depot was the door it opened. The relationship between TTI and Home Depot became one of the most important distributor partnerships in American retail—and one of the most unusual.

It’s unusual because it’s both an engine and a dependency. At peak concentration, about half of TTI’s sales came from a single customer: The Home Depot. That kind of customer exposure makes investors nervous for good reason. One shift in strategy, one change in shelf space, and an entire growth story can wobble.

But in this case, the concentration persisted because the partnership kept paying both sides.

For Home Depot, TTI’s brands—especially Ryobi—aren’t just “products on shelves.” They’re traffic drivers. Ryobi gives Home Depot something competitors can’t copy aisle-for-aisle: a unique, affordable tool system customers can’t buy at Lowe’s or Menards. That exclusivity helps build loyalty, pulls people into stores, and keeps them coming back as they add more tools to the same battery platform.

For TTI, Home Depot provides something even more valuable than volume: a real-world laboratory.

TTI’s field sales teams are embedded in Home Depot stores, watching what customers pick up, what they put back, and what they ask for when they can’t find the right tool. That information flows directly back to product teams and R&D, shaping what gets built next. Instead of guessing demand from headquarters, TTI can hear it—every day, on the floor.

TTI also reinforces the relationship with channel discipline. It remains one of the few tool companies that does not sell directly through broad, generic platforms like Amazon. That protects Home Depot’s exclusivity and helps maintain price integrity. Just as important, it forces the Ryobi experience to happen where Home Depot is strongest: in-store, hands-on, with products customers can touch before they buy.

With Ryobi consistently among Home Depot’s top-selling brands, the two companies extended their exclusivity partnership through 2028. The result is a long runway on both sides: TTI gets years of shelf-space certainty for a cornerstone brand, and Home Depot keeps exclusive access to one of the strongest DIY tool ecosystems in North America—while TTI continues pushing for growth beyond it in other regions.

X. Recent Decade: Outdoor Power Equipment & Cordless Domination (2015–2024)

Over the past decade, TTI pushed its cordless revolution beyond drills and saws and into the last stronghold of small engines: outdoor power equipment. Lawnmowers, leaf blowers, string trimmers—categories that, for decades, basically meant gas.

The headline move on the Milwaukee side was the MX FUEL Equipment System. With MX FUEL, Milwaukee stepped out of handheld tools and into the multi-billion-dollar “light equipment” market—gear like rammers and concrete vibrators that had long been assumed to require gas engines or cords. Milwaukee positioned MX FUEL as the industrial frontier of cordless: performance, run-time, and durability aimed at the trades, without the emissions, noise, vibration, or the constant maintenance rituals that come with gas.

TTI kept expanding the system. By the end of 2022, MX FUEL had grown into a broad lineup of solutions. And by 2024, Milwaukee was still using it to challenge what the jobsite assumed was possible with batteries—pointing to new launches like the MX FUEL Backpack High Cycle Concrete Vibrator and the MX FUEL 70kg Rammer, and to a platform that had grown to more than 25 solutions and was still expanding.

At the same time, the bigger market tide was turning in TTI’s favor. Outdoor power equipment was steadily shifting from gas to battery, pushed by a mix of environmental regulations, noise restrictions, and consumer preference. TTI—already built around battery systems, electronics, and cordless ecosystems—was positioned to ride that wave rather than fight it.

Milwaukee leaned into pros here, too. In 2022, it expanded its Outdoor Power Equipment lineup with products like the M18 FUEL 21" Self-Propelled Dual Battery Mower, designed to compete directly against gas alternatives, and the M18 FUEL Dual Battery Blower, built to deliver high, consistent power across the full charge.

By this point, the market started treating TTI less like a category player and more like a category shaper. In 2019, its shares were added to the Hang Seng Index—Hong Kong’s benchmark list of leading public companies—another signal that the former OEM had become a major force, not just in tools, but in the public markets too.

XI. The COVID Test & Supply Chain Resilience

Then COVID hit—and it stress-tested every weak link in modern manufacturing at once.

TTI was exposed on paper. Its biggest customer was Home Depot, the epicenter of North American home improvement. And a huge portion of its production sat in China, where factories were shutting down and logistics were snarling. For most companies, that combination would have meant one thing: pull back, protect cash, and hope demand comes back later.

TTI did the opposite.

In 2020, as much of the industry went defensive, TTI accelerated new product launches. And while many competitors fought shortages and empty shelves, TTI didn’t report the same kind of supply problems—and even increased production to go after share. Joseph Galli summed up the mindset neatly: “a crisis reveals character.”

The results showed up quickly. In the first half of 2020, TTI grew sales by nearly 13% and expanded net margin by 30 basis points to 7.9%. Over the same period, its biggest rival, Stanley Black & Decker, posted a double-digit sales decline.

Demand helped, too. The pandemic didn’t just change where people worked—it changed what they did at home. Renovations, repairs, backyard projects: suddenly, tools weren’t discretionary. And in that moment, availability mattered as much as brand. Ryobi and Milwaukee were in stock when others weren’t, and that’s how share shifts—quietly, cart by cart.

What made that possible wasn’t luck. TTI had already started reducing its dependence on China in the years before COVID, responding to rising geopolitical and tariff risks. It invested in production capacity in Vietnam, Mexico, and the United States, creating optionality that became invaluable when China faced shutdowns. When one region froze, others could take on more load.

And while many companies were cutting headcount, TTI kept investing in people. It continued recruiting for its Leadership Development Program, betting that the downturn would be temporary and that the next generation of leaders needed to be built in real time, not in hindsight.

In a year when supply chains broke and competitors stumbled, TTI treated the disruption as a proving ground—and used it to widen the gap.

XII. The 2024 CEO Transition: Steven Richman Era Begins

In 2024, TTI hit its biggest leadership handoff in years. After 18 years as CEO, Joseph Galli Jr. retired—closing the chapter on the operator who helped turn TTI’s brands, and especially Milwaukee, into jobsite default choices.

The successor was a familiar name inside the building: Steve Richman. After 17 years as president of Milwaukee Tool, Richman moved up to CEO of Techtronic Industries, an outcome that signaled continuity more than a course correction. TTI formally appointed Mr Steven Philip Richman to the Chief Executive Officer role on May 21, 2024.

Richman had been running the Milwaukee business since 2007. During that stretch, Milwaukee reached new heights—posting double-digit compounded annual growth in revenue and expanding to a workforce of more than 21,000 people worldwide. The culture he helped build at Milwaukee, alongside a deep leadership team, was a major force behind that transformation.

And like Galli, Richman is very much a tool-industry lifer. Before Milwaukee, he held key management roles at Black & Decker and served as president of both Skil and Bosch Power Tools for more than five years each. He didn’t need a learning curve on the competitive dynamics—he’d been inside them for decades.

The transition itself was designed to be smooth. Responsibilities were redistributed across a deep executive bench, and the company’s long-running focus on leadership development showed its value: TTI had multiple qualified internal candidates ready to step up.

XIII. Playbook: Business & Investing Lessons

TTI’s story reads like a case study, but the lessons are unusually practical—and unusually hard to copy.

The OEM-to-Brand Transition: TTI shows that it’s possible to escape the OEM trap and become a brand owner, but not by “deciding to do branding” one day. It took the right acquisitions, patient capital, and the operational discipline to integrate what it bought. Most OEMs never make this leap because they’re optimized for manufacturing, not for building demand. TTI’s advantage was that it didn’t try to will brands into existence from scratch. It bought real ones—then poured money and talent into making them better.

Platform Ecosystem Lock-In: Milwaukee and Ryobi both prove the same point: batteries are the platform. When a customer commits to a battery system—and knows it’ll remain compatible—every next purchase gets easier. Ryobi has made that compatibility promise for more than two decades, reducing the friction and anxiety of buying into a system. And the switching costs are natural: once you own the batteries, chargers, and a few tools, leaving doesn’t just mean buying a drill. It means replacing the whole ecosystem.

Dual-Brand Portfolio Strategy: Serving pros and DIYers without turning your portfolio into a muddle requires discipline. TTI kept Milwaukee and Ryobi clearly segmented—different customers, different price points, different brand identities, even separate headquarters and cultures. They operate like two distinct companies that share corporate ownership and manufacturing leverage, which lets TTI cover the market without confusing anyone—or cannibalizing itself.

R&D Intensity: TTI has consistently out-invested the category in innovation—about 3% of revenue into R&D versus roughly 2.3% for the industry. And it has turned that into a steady stream of new products, with around a third of annual sales coming from recent launches. The rhythm looks less like an old-line industrial company and more like a consumer products machine: keep reinvesting, keep refreshing the lineup, and let new generations of products pull pricing and growth forward.

Leadership Development: TTI treated talent as a long-term system, not a yearly budget line. Its Leadership Development Program has built a pipeline of future executives, and the company kept feeding it even when others cut back. During COVID-19, while many companies slowed recruiting, TTI accelerated hiring high-potential graduates. That kind of steady investment compounds quietly—and it’s one of the hardest advantages for competitors to replicate.

XIV. Porter's 5 Forces & Hamilton's 7 Powers Analysis

Porter's Five Forces:

Threat of New Entrants: LOW

Breaking into power tools isn’t like launching a new app. The modern battleground is the battery platform, and that takes years of engineering, testing, and capital to build. In 2022 alone, TTI invested $206 million in its Wisconsin R&D facilities. A would-be entrant would need to develop competitive battery tech, stand up manufacturing at scale, secure distribution, and somehow earn brand trust—basically all at once. That’s a high wall, and it’s why serious new entrants are rare.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers: MODERATE

TTI doesn’t hand its fate to outside suppliers for the parts that matter most. By designing and manufacturing battery packs and motors in-house, it reduces supplier leverage over critical components and keeps control of performance and iteration speed. Battery cells are a different story: they’re more commodity-like, sourced from multiple manufacturers, so supplier power there is more balanced.

Bargaining Power of Buyers: MODERATE-HIGH

The risk is obvious: Home Depot represents a large share of sales, and big retailers always have leverage. But the relationship isn’t one-sided. TTI’s brands are effectively “must-have” for the category, and Home Depot can’t simply swap out Ryobi without giving up a distinctive, exclusive platform that drives traffic and repeat purchases. In practice, it’s mutual dependence—power on both sides, kept in check because each needs the other.

Threat of Substitutes: LOW

There’s no real substitute for a drill, a saw, or an impact driver when you need to build or fix something. The “substitution” that matters is actually a migration: corded to cordless, and gas to battery. Those shifts don’t threaten TTI—they reinforce what it has spent decades building.

Competitive Rivalry: HIGH

This is a knife-fight category. Stanley Black & Decker, Bosch, Makita, Hilti, and others are well-funded, technically capable, and deeply entrenched with pros and retailers. Competition continues to intensify as companies push product extensions, invest in new technology, and use acquisitions to fill gaps. TTI has been taking share, but it does so in an arena where competitors are always close enough to punish complacency.

Hamilton's 7 Powers:

Scale Economies: TTI’s manufacturing scale—built over decades, including major capacity in Dongguan—creates structural cost advantages. It can spread fixed costs like R&D over a much larger revenue base, which supports heavy investment while still keeping pricing competitive.

Network Effects: There aren’t classic network effects here, but there is an indirect version through platforms. The biggest battery ecosystems tend to attract third-party accessory support, which reinforces the value of being on the “winning” platform.

Counter-Positioning: TTI’s obsessive push into cordless—especially lithium-ion—was a form of counter-positioning against incumbents that were still tied to older corded and legacy battery approaches. By moving hard and early, TTI forced rivals into an uncomfortable choice: follow quickly and write down existing bets, or hesitate and risk conceding the most important growth segment.

Switching Costs: This is one of TTI’s clearest powers. Once a pro is invested in Milwaukee’s M18 ecosystem—or a homeowner is deep into Ryobi ONE+—switching isn’t just buying a different drill. It’s replacing batteries, chargers, and habits. The platform becomes the anchor.

Branding: Milwaukee brings a century of heritage and a reputation for durability in the professional world. Ryobi stands for value and convenience, reinforced by its Home Depot exclusivity. Both brands mean something specific to their customers—and that meaning is hard for competitors to copy.

Cornered Resource: Years of investment in proprietary battery and motor technology has created know-how and IP that can’t be replicated quickly. Key patents protect certain innovations, but just as important is the accumulated engineering learning that lives inside the organization.

Process Power: TTI’s advantage isn’t only what it invents—it’s how reliably it ships. Manufacturing discipline, supply chain execution, and tight product development loops add up to organizational capability that compounds over time and is difficult for competitors to match.

XV. Key KPIs for Investors to Monitor

If you want to track whether TTI’s machine is still working the way it’s supposed to, three signals matter more than almost anything else:

1. Milwaukee Growth Rate: Milwaukee is the flagship—and the engine that pulls the rest of the portfolio forward. In 2024, MILWAUKEE grew 11.6% in local currency, while RYOBI grew 6.4%. As long as Milwaukee is growing at a double-digit pace, it’s a strong indication TTI is still taking share and keeping pros locked into the platform. A meaningful slowdown would be the early warning sign to watch: either competitors are catching up, the market is maturing, or Milwaukee is running into saturation.

2. Gross Margin Expansion: In 2024, gross margin rose by 85 basis points to 40.3%. Management attributed that improvement to a richer mix of MILWAUKEE branded sales, more aftermarket battery sales, and a pipeline of highly innovative new products that are margin-accretive across core verticals. In plain English: TTI is selling more of the good stuff, and the ecosystem is paying off. If gross margin starts to compress, it usually means the opposite forces are winning—more discounting, tougher price competition, or unfavorable input costs.

3. New Product Revenue Percentage: TTI targets roughly one-third of annual sales coming from new products. This is the scoreboard for innovation velocity: are new launches actually landing in the market and becoming meaningful contributors, or is the portfolio living off yesterday’s hits? If this percentage slides, it’s often a sign that R&D output isn’t converting into demand—or that customers are no longer upgrading at the same rate.

XVI. Risks and Watchpoints

Customer Concentration: Even after some moderation, Home Depot is still TTI’s biggest customer. That partnership is a moat, but it’s also exposure. If the relationship ever weakened—because of competitive pressure, channel conflict, or a strategic shift inside Home Depot—the impact would show up quickly in TTI’s North American results.

Geopolitical Risk: TTI manufactures across China, Vietnam, the United States, Mexico, and Europe. The company has deliberately diversified away from China, but a meaningful share of production still sits there. Any escalation in U.S.-China trade tension—tariffs, restrictions, or logistics shocks—could hit costs, pricing, and product availability at the exact moment retailers care most: peak season, with shelves on the line.

Competition: This is a constant arms race. Stanley Black & Decker remains a heavyweight, and rivals like Makita, Bosch, and Hilti keep pouring investment into cordless. The clearest threat isn’t marketing—it’s technology. A real breakthrough in battery performance, cost, or durability from a competitor could narrow the gap that TTI has spent years widening.

Founder Transition: Horst Pudwill, now in his late seventies, has been TTI’s strategic architect for nearly four decades, and the Pudwill family remains the largest shareholder. Stephan Pudwill, Horst’s son, serves as Vice Chairman, and succession planning appears deliberate—but the eventual full shift away from founder-era influence is still a generational handoff, with all the execution and culture risk that comes with it.

Valuation: TTI has often traded at premium multiples because the market has rewarded its growth and consistency. The flip side is simple: if growth disappoints, valuation can compress at the same time earnings take a hit—turning a normal operating stumble into an amplified stock move.

XVII. The Investment Thesis

TTI’s story, at its core, is a story of positioning: a strong set of brands sitting in the center of a category that’s being reshaped by a long, favorable shift toward cordless and battery power.

Power tools are a “need-to-have” category. Construction, repair, maintenance, and home improvement don’t stop for long, and all of them consume tools. Demand does move with the cycle—housing slowdowns and contractor sentiment matter—but the baseline is durable. People keep building, fixing, and upgrading, and when they do, they need the gear.

What makes this era different is the platform shift. The industry is steadily moving from corded to cordless, and outdoor power equipment is moving from gas to battery. That transition rewards whoever owns the best battery ecosystem, because the battery isn’t just a component—it’s the lock-in. Every pro who commits to Milwaukee’s M18 platform is far more likely to keep buying Milwaukee. Every homeowner who stacks up Ryobi batteries and chargers is naturally less inclined to start over somewhere else.

That’s the strategic reason TTI has worked. The financial results in 2024 show the operating reason.

TTI grew sales 6.8% in local currency to US$14.6 billion and generated record free cash flow of US$1.6 billion. In local currency, the flagship MILWAUKEE business grew 11.6%, and RYOBI grew 6.4%. It ended 2024 with total net debt of US$44 million and gearing of 0.7%.

Put simply: strong growth where it matters most, plenty of cash, and almost no leverage. That profile gives TTI options. It can keep funding innovation and expansion organically, while still returning capital to shareholders.

Management’s messaging has stayed consistent, too. Looking ahead, the company framed 2025 as a continuation of the same play: pushing cordless deeper into more categories with disruptive technology and innovative design, while delivering strong financial results.

So the investor question isn’t whether TTI has won so far. It has. The real question is whether it can keep winning as competitors close the gap and the biggest markets mature. Can TTI keep moving the frontier fast enough that rivals are always reacting, not leading?

What began with Horst Pudwill arriving in Hong Kong in 1971 has become a US$14.6 billion enterprise that shapes how millions of people work with their hands. And the cordless revolution TTI helped pioneer isn’t finished. It’s still spreading—into outdoor equipment, light construction equipment, and whatever categories are next. For a company built around ecosystem lock-in, relentless innovation, and execution discipline, that ongoing shift isn’t a footnote. It’s the opportunity.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music