LG Electronics: From Post-War Radios to OLED Dominance – The Korean Conglomerate That Learned When to Let Go

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

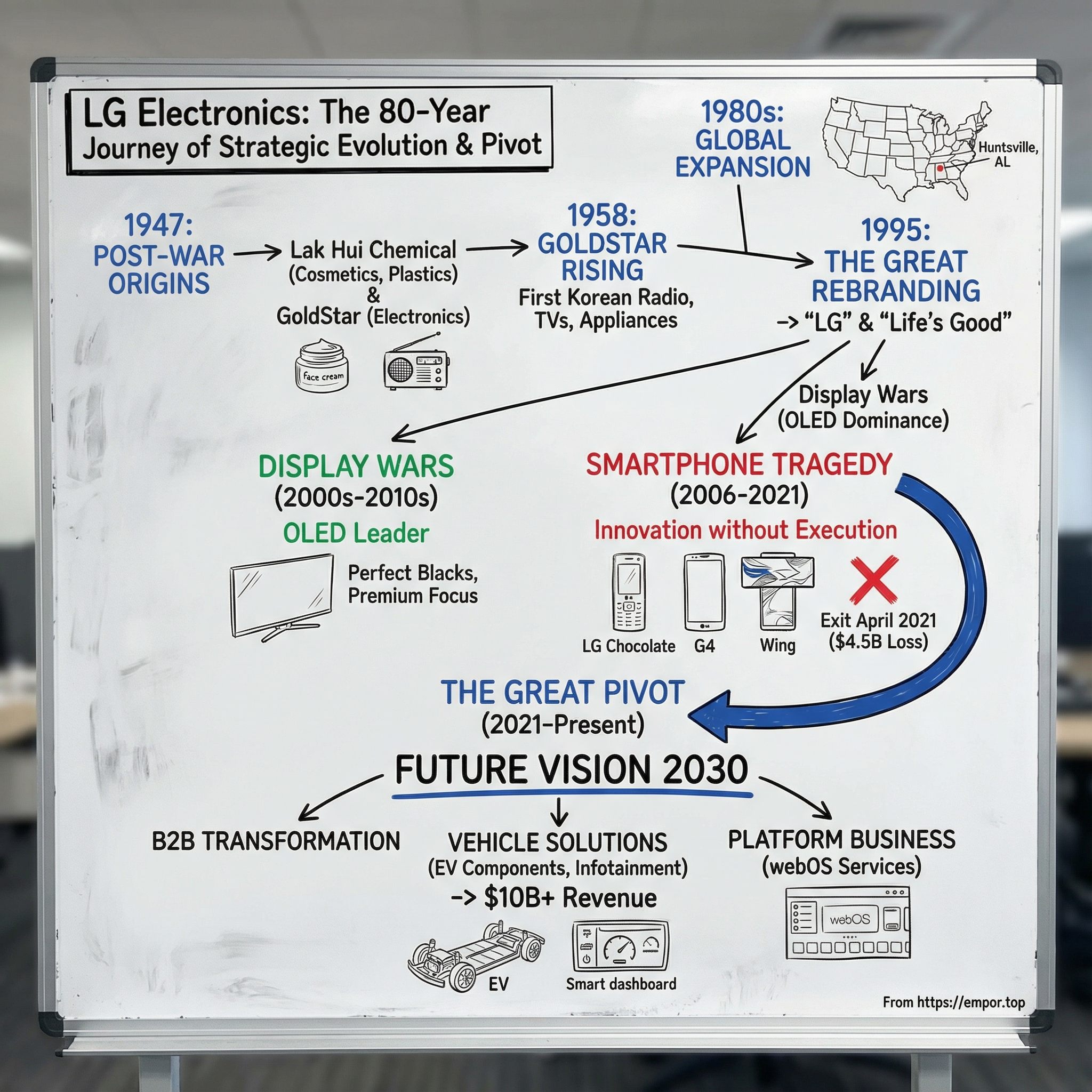

Picture this: April 5, 2021. Inside LG’s headquarters in Yeouido, Seoul, the leadership team convened for a board meeting that had been creeping toward inevitability for months. When it ended, LG Electronics had done something almost unheard of for a global brand with real history: it decided to leave smartphones entirely.

After more than a quarter century in mobile phones, LG became the first major smartphone maker to fully withdraw from the global market, walking away after racking up $4.5 billion in cumulative losses. The industry read it as surrender. But what made it remarkable wasn’t the exit itself. It was what that exit made possible.

Fast forward to 2024. LG announced its full-year results: consolidated revenue of KRW 87.73 trillion and operating profit of KRW 3.42 trillion—its highest annual revenue ever. Call it roughly $64 billion. In other words: the company wasn’t just surviving without smartphones. It was setting records.

And the engine of that comeback wasn’t some lucky break. It was a portfolio built around categories where LG could actually win. For 12 consecutive years, LG led the global OLED TV market, pushing the medium forward with audiovisual performance and AI-powered personalization—anchored in what OLED does best: perfect blacks and higher brightness. In 2024, OLED TV shipments hit 3.18 million units, good for more than half the market. In the U.S., LG washing machines held the top sales position for nine straight years. And the vehicle solutions business—barely a footnote a decade ago—was racing toward $10 billion in annual revenue.

So this isn’t just a story about gadgets. It’s a story about one of the hardest calls in business: when to keep fighting, and when to retreat. How does a company built around “Life’s Good” learn that sometimes life really is better when you admit defeat in one arena—so you can redeploy and win in another?

That’s the journey we’re telling: nation-building entrepreneurship, chaebol dynamics, innovation that sometimes landed and sometimes didn’t, and ultimately the art of the strategic retreat—followed by one of the most ambitious pivots from consumer electronics to B2B in modern tech. It spans nearly eight decades, three generations of family leadership, and a path from making face cream in post-war Korea to defining premium displays and the future of mobility.

II. The Lucky Origins: Post-War Korea & the Koo Family Vision (1947–1958)

In the wreckage of mid-century Korea, Koo In-hwoi looked at a country with empty shelves and saw a blueprint. He was born in 1906 in Jinyang, South Gyeongsang Province, and grew up in a strict household where four generations lived under one roof. That upbringing fed a philosophy he carried into business: harmony—between customers, employees, and partners—wasn’t sentimental. It was structural.

After finishing secondary school at Seoul’s Central Normal Higher School in 1924, Koo moved quickly into commerce. By 1931, he’d begun his business journey, focusing on cosmetics. But the real inflection point came after World War II, when Korea was liberated from Japanese colonial rule and suddenly had to rebuild a domestic economy almost from scratch.

In January 1947, Koo founded Lak Hui Chemical Industrial Corporation in Seoul—one of the earliest seeds of what would become the LG empire. The name mattered. After the runaway success of Lucky Cream, Korea’s first locally made face cream, Koo chose “Lucky,” a sound-alike for “Lak Hui,” a word associated with bringing joy to all.

The timing was audacious. Consumer goods were scarce, supply chains were broken, and Japanese manufacturers—who had dominated production—were gone. Koo’s bet was straightforward: make the everyday essentials Koreans needed, and make them at home, with whatever materials the country could actually secure.

Lucky Cream proved there was real demand. It sold out quickly, even at a relatively high price, helped by high-quality ingredients. Then came the kind of problem that either ends a young company or hardens it: the metal lids on the jars caused returns. Koo didn’t treat it as a packaging headache. He treated it as a manufacturing opportunity.

His fix was plastic—rare in Korea at the time. In September 1952, he opened a plastics plant in Busan. Almost immediately, Lucky began turning out plastic household goods, starting with hairbrushes that became a hit in their own right. Demand surged so fast that within two months the company was adding more machines and expanding into products like toothbrushes and washbowls. What started as a workaround became a habit: if a dependency threatened the business, build the capability in-house.

That same year, Lak Hui (락희), pronounced “Lucky” and now known as LG Chem, became the first South Korean company to enter the plastics industry. Cosmetics had been the door. Plastics became the engine. And the pattern was now unmistakable: Koo wasn’t just selling products—he was building an industrial base.

He was also building a partnership that would shape the group for decades. A relative of his wife, Huh Man-jung, visited with his eldest son, Huh Joon-gu, newly returned from studying in Japan. Huh Man-jung offered to invest, with one condition: Koo would mentor his son in the ways of business. It became the beginning of a long-running partnership between the Koo and Huh families.

This mix of manufacturing ambition, relationship-driven capital, and multi-generational intent was the early chaebol template in miniature—resilient, tightly bound, and designed to last. And as LG’s story unfolds, that endurance would matter just as much as any single product breakthrough.

III. GoldStar Rising: Korea's Electronics Pioneer (1958–1980s)

By 1958, Koo In-hwoi was ready for his next audacious move: electronics. That year he founded GoldStar Co. Ltd. with a simple, nation-sized ambition—give a rebuilding Korea its own domestically made consumer electronics and home appliances. The timing couldn’t have been better. National broadcasting was taking off, and with it came a surge in demand for radios, and soon, televisions.

GoldStar moved fast. It set out to build a radio immediately, and in 1959, South Korea’s first locally made radio began rolling off the line. That moment landed as more than a product launch. For the first time, Korean households could buy sophisticated electronics made by Korean hands, backed by Korean manufacturing.

And then GoldStar kept stacking “firsts.” The early lineup expanded quickly—telephones, fans, refrigerators, televisions, air conditioners, washing machines—each one another step up the industrial ladder.

A big part of that speed came from partnerships with Japanese companies, especially Hitachi. It was a pragmatic choice wrapped in political tension. Japan’s colonial occupation had ended only 13 years earlier, and cooperation was still fraught. But the technical value was undeniable: manufacturing know-how, components, and quality control systems that would have taken years—maybe decades—to build from scratch.

The strategy worked, and the milestones started to compound. In 1960, GoldStar produced South Korea’s first refrigerator. In 1969 came the first black-and-white television. In 1977, the first color television. Each “first” wasn’t just a headline—it was a new capability added to the company’s toolkit.

Then, as the company was hitting stride, the story turned. Koo In-hwoi died on December 31, 1969, handing the group into its second generation at the exact moment Korea was entering a new decade of industrial acceleration. Leadership passed to his son, Koo Cha-kyung, and under him both Lak Hui and GoldStar grew rapidly.

GoldStar ramped up production of 19-inch color TVs in 1977. Lak Hui—later known as Lucky—crossed 100 billion won in revenue by 1978. And by 1976, GoldStar was producing one million televisions a year—an output level that practically demanded the next leap: going global.

That leap arrived in 1982, when GoldStar opened its first overseas factory in Huntsville, Alabama. This wasn’t just about selling into the U.S. It was about proving that Korean manufacturing could stand on the same ground as the world’s best, in the world’s most competitive consumer market. Japanese brands had already pioneered the “transplant factory” model to navigate trade friction; GoldStar was learning the same playbook, adapting products for foreign buyers and getting fluent in the realities of global commerce.

Looking back, it’s hard to separate GoldStar’s rise from Korea’s. Koo In-hwoi’s push into electronics helped lay the foundation for the country’s modern consumer tech industry—and decades later, that impact was formally recognized when he was posthumously inducted into the Consumer Electronics Hall of Fame in 2012.

IV. The Great Rebranding: From Lucky-Goldstar to "Life's Good" (1983–1999)

By the early 1980s, Koo In-hwoi’s original ventures had outgrown the “two-company” story. Lucky and GoldStar were now big enough—and intertwined enough—that they needed to act like one organism. So in 1983, they were brought under a single umbrella: Lucky Goldstar Group. The logic was simple and very chaebol: pair Lucky’s chemical and plastics backbone with GoldStar’s electronics ambition, and let each side reinforce the other with shared capital, shared capability, and shared patience.

From there, the group expanded hard. It pushed into high-tech bets like petrochemicals, energy, and semiconductors, and it also sprawled into the infrastructure of modern commerce: construction, securities, distribution, and insurance. By the late 1980s, Lucky Goldstar was no longer a company you could summarize in a sentence. It was dozens of affiliates—an interconnected web of cross-shareholdings designed to scale fast, weather shocks, and keep control tightly held.

But as the 1990s arrived, LG faced a very modern problem: the name. “Lucky Goldstar” was a mouthful overseas, and worse, it didn’t land as a single clear identity. Management concluded they needed a sharper global brand—something vivid, integrated, and easy to remember in a world where consumer electronics shelves were getting crowded.

The solution rolled out like a campaign. On January 1, 1995, newspapers printed a simple red symbol—something like a winking smile—with the cryptic line “Happy New Year.” Three days later came the reveal: Lucky Goldstar would become LG, paired with a new tagline, “Life’s Good.” Under Koo Bon-moo, the group renamed itself to LG that year and trademarked the letters “LG” alongside the slogan that would travel around the world.

The rebrand also matched a handoff of power. After 25 years leading the group, Koo Cha-kyoung stepped down and passed leadership to his eldest son, Koo Bon-moo, in 1995. The third-generation chairman would go on to guide LG through its most intense era of globalization—and through a set of technology bets that would shape what LG became.

One of the biggest moves came that same year: the acquisition of Zenith Electronics, the storied American TV maker. Zenith had been battered by Japanese competition, but it still held valuable HDTV technology patents and a foothold in the U.S. market. For LG, the deal wasn’t about nostalgia. It was about positioning for the transition to digital broadcasting—and getting there with real intellectual property, not just manufacturing muscle.

1995 also delivered a very different kind of milestone. LG Electronics developed the world’s first CDMA digital mobile handsets and supplied Ameritech and GTE in the United States. It was an early signal that LG could do more than appliances and TVs. Mobile would become one of its most visible arenas—first as a source of pride, later as a source of pain.

Then the ground moved. In 1997, the Asian Financial Crisis tore through Korean industry and forced restructuring across the chaebol system. The era of easy debt ended abruptly, and companies that had expanded on leverage suddenly faced markets demanding repayment now. In that environment, LG Chem moved faster than many peers, pursuing innovation and managing to keep operating in the black even as the broader system seized up.

The crisis made expansion harder—but it also clarified what mattered next. LG accelerated its push into display technology, betting that screens would become the primary interface of the digital age. In 1998, it developed the world’s first 60-inch plasma TV, a statement not just of engineering bravado, but of large-format manufacturing capability.

And in 1999 came the move that would echo for decades: LG formed a joint venture with Philips called LG.Philips LCD, later renamed LG Display. Philips brought LCD technology. LG brought scale and manufacturing discipline. Together they built the platform that would grow into a global powerhouse—and, in many ways, planted the earliest seeds of LG’s eventual OLED dominance.

V. The Display Wars: OLED Dominance & The Samsung Rivalry (2000s–2010s)

LG’s display dominance is the story of a long, stubborn bet—one that took years of losses, process breakthroughs, and patience to look “obvious” in hindsight. As Samsung spread its chips across the table—memory semiconductors, mobile, and eventually an empire of components—LG kept coming back to a simpler idea: own the premium screen.

A major step came in 2009, when LG acquired Kodak’s OLED business for around $100 million. Tucked inside that deal were more than 2,000 OLED-related patents—decades of research Kodak had been compiling since the 1970s. LG housed the trove in a subsidiary called Global OLED Technology (GOT), and from there it went to work methodically: build a defensive moat of intellectual property, then turn it into an execution advantage on factory floors.

OLED, on paper, sounds like a straightforward upgrade. Instead of an LCD panel that needs a backlight, OLED uses organic compounds that emit their own light when electricity flows through them. The result is the stuff people notice instantly: true blacks, vivid color, wide viewing angles, and panels thin enough to feel like set design.

In practice, it was brutal. Those organic layers are delicate, and scaling them to big TV sizes with good yields and acceptable lifespan demanded enormous investment in R&D, manufacturing equipment, and quality control. LG made the rare choice to spend into the problem anyway—betting that if it could crack large-screen OLED, it wouldn’t just have a better TV. It would have a category.

By January 2015, LG Display had reinforced the supply chain side of that strategy too, signing a long-term agreement with UDC for OLED materials and rights to use patented OLED emitters. Piece by piece, LG wasn’t only building a product. It was building an ecosystem that could keep producing that product at scale.

The technology path mattered, too. While Samsung leaned into OLED for mobile screens and later pursued QD-OLED, LG committed to white OLED, or WOLED, for large-format televisions. That decision created a lane where LG could run with less direct head-to-head pressure in the exact segment it cared about most.

Over time, the bet turned into a lead. In 2024, LG Electronics once again topped global OLED TV shipments, taking 52.4 percent market share. In ultra-large OLED—75 inches and above—it held an even stronger position, with a 57.5 percent share. Omdia reported LG shipped 3.18 million OLED TVs that year, with fourth-quarter shipments alone surpassing 1.1 million units.

And LG didn’t just win on volume. It used the platform to keep signaling what “premium” could mean. In 2012, it produced the world’s first 84-inch 4K TV, priced at about $20,000—far out of reach for most people, but a clear message to the market: this is where the company intended to lead. Later came the rollable OLED TV, a screen that retracts into its base when you’re done watching—part engineering flex, part functional art.

While OLED became the halo, LG was also building something less flashy and arguably more important: an appliance fortress. Its washing machines held the number-one position in U.S. sales for nine consecutive years. Globally, LG reached a 20% value share in the major appliance market. And by Q2 2025, LG remained in the top tier of major appliance brands alongside Whirlpool, GE, and Samsung—each holding double-digit share in both units and dollars.

That sets up the rivalry that’s shadowed LG for decades. LG and Samsung fought brutally in TVs and appliances, but their strategic DNA diverged. Samsung doubled down on memory semiconductors and became the world’s largest chip manufacturer. LG largely opted out of that capital-intensive arena, choosing to concentrate on displays, appliances, and, eventually, the automotive opportunity it could see coming.

Those choices came with tradeoffs. Samsung’s semiconductor cash flows funded an almost unlimited appetite for expansion. LG’s narrower focus enabled deeper specialization—but demanded sharper, more disciplined capital allocation.

And then there was the arena that would test all of it: smartphones—the most unforgiving consumer electronics market ever created.

VI. The Smartphone Tragedy: Innovation Without Execution (2006–2021)

LG’s smartphone story didn’t start as a cautionary tale. It started as a flex.

LG had been making phones since the mid-1990s, and by the mid-to-late 2000s it had real momentum. The LG Chocolate in 2006 wasn’t just popular—it helped pull touch-forward, design-first phones into the mainstream. Then came the LG Prada in 2007, one of the first phones to use a capacitive touchscreen, arriving before the iPhone and signaling that LG could see where the category was headed.

In 2008, LG pushed touch even further downmarket with the LG Cookie series, one of the early affordable touchscreen phones—part of what made the idea of “a touchscreen phone” feel inevitable, not elite. And in the early 2010s, LG earned a different kind of credibility by building Google’s Nexus 4 and Nexus 5: enthusiast favorites that delivered high-end specs at prices people could actually justify.

For a moment, the trajectory looked real. In early 2014, LG reported it had sold more than 5 million LTE-enabled smartphones—up sharply versus the prior year—and LG Mobile’s last profitable year would be 2014. At the time, LG was widely seen as a top-tier smartphone manufacturer with a knack for breakthrough design.

Then the bottom fell out.

The cracks became impossible to ignore in 2015 with the LG G4. The phone became associated with “bootloop” failures—a hardware issue that could trap devices in endless reboot cycles. Customers went to service centers, got replacements, and in too many cases watched the replacements fail the same way. That kind of experience doesn’t just hurt a model. It poisons trust in the brand. In 2018, LG settled a class-action lawsuit over bootloop issues that affected not only the G4, but also the G5, V10, and V20.

As confidence drained, so did performance. The mobile business ran up losses for 23 consecutive quarters. Cumulative operating losses reached around 5 trillion won, roughly $4.4 billion. And LG’s share of global smartphone shipments collapsed—from about 10% in 2009 to under 1% by 2021.

So what went wrong? It wasn’t one thing. It was four problems arriving at once—and reinforcing each other.

First, LG got trapped in the worst strategic place in consumer tech: the middle. It couldn’t command premium pricing like Apple and Samsung, but it also couldn’t win the value segment against aggressive Chinese competitors. Too expensive to be the “smart budget buy,” not strong enough to be the “must-have flagship.”

Second, innovation without adoption. LG kept shipping bold ideas—modular add-ons on the G5, curved screens with the G Flex, rotating dual-screen hardware with the Wing. These phones generated headlines and admiration, but they didn’t create a stable, growing mainstream audience. Even when an idea was promising, LG often didn’t—or couldn’t—push it far enough for it to become a true platform.

Third, software. While Apple, Samsung, and Google relentlessly refined the everyday experience, LG’s software reputation lagged badly. In smartphones, hardware sells the first month. Software decides whether people ever come back.

Fourth, marketing that rarely broke through. Compared to the cultural moments created by Apple launches or Samsung’s global campaigns, LG’s phone releases often felt quiet—noticed mainly when reviewers pointed out something clever or unusual, rather than because the market was waiting for them.

And then came the final wave: China’s rise from the low end to everywhere. By 2020, Chinese brands like Xiaomi, Vivo, Oppo, and Realme held a combined 57% global share. A decade earlier, Chinese phone makers barely registered in global sales. The middle of the market—the place LG was stuck—became a bloodbath.

LG looked for alternatives. It explored options including a sale, with reported interest from Vietnam’s Vingroup, Volkswagen, and Google. Nothing materialized.

So on April 5, 2021, LG announced the decision: it would exit the mobile phone business. Phone production would continue into the end of May, and the withdrawal would be completed on July 31, 2021.

LG became the first major smartphone brand to fully walk away from the market. And in a strange way, the industry did lose something: LG was one of the few big manufacturers still willing to take real hardware risks, even when those risks didn’t always translate into commercial wins.

But the more important lesson was internal. The smartphone era punished anything less than excellence across the full stack—hardware, software, ecosystem, and go-to-market. It also punished indecision in positioning. And sometimes the most strategic move isn’t doubling down on pride. It’s taking the hit, closing the chapter, and freeing the company to fight where it can actually win.

That’s exactly what LG did next.

VII. The Great Pivot: Future Vision 2030 & The B2B Transformation

What happened after the smartphone exit is the real twist. LG didn’t just patch the hole and move on. It used the moment to re-architect the company—quietly pulling resources out of the most chaotic consumer category on earth and pushing them into businesses where scale, reliability, and long product cycles actually matter.

That strategy got a name: LG’s Future Vision 2030. CEO William Cho framed it as a plan to turn LG into a “Smart Life Solution Company,” connecting customer experiences across the home, commercial spaces, mobility, and even virtual environments. In other words, less “sell a device and hope,” more “own the systems people and businesses run every day.”

You can see the shift in the mix. LG expects B2B to account for around 45 percent of total revenue by 2030. B2B was about 27 percent in 2021, and had risen to 35 percent by the end of last year—an eight-point jump in three years. That’s not a slide deck. That’s the business changing underneath you.

Of course, pivots like this don’t run on slogans. They run on capex and focus. LG said it would more than double its investment, putting $8 billion into R&D and other key areas to strengthen competitiveness—especially in B2B and newer bets like EV charging and robotics. And by 2030, LG has announced plans to invest more than $40 billion to reshape its portfolio for what it calls “qualitative business growth.”

The most visible growth engine is mobility. LG’s Vehicle component Solutions Company crossed a psychological threshold and stayed there: in 2024 it reported KRW 10.62 trillion in revenue, its second straight year above KRW 10 trillion. Even with a temporary slowdown in EV demand, the unit delivered its ninth consecutive year of stable revenue growth, supported by a large order backlog.

The business sits on three pillars: in-vehicle infotainment, e-powertrains through the LG Magna e-Powertrain joint venture, and vehicular lighting—boosted by LG’s acquisition of Austrian lighting specialist ZKW in 2018. LG also reported a 22.4% share of the vehicle telematics market in the first quarter of 2023. And it’s aiming squarely at where the industry is headed: autonomous driving, software, digital content, and EV charging. By year-end, the order backlog for the vehicle solutions unit was expected to reach $78.5 billion as demand for in-vehicle electronics keeps rising.

At the same time, LG has been building something that looks less like traditional hardware and more like a modern platform business. Cho highlighted subscription services and webOS-based revenue, which rose more than 75% year-over-year in 2024, approaching KRW 2 trillion.

Within that, advertising and services delivered through webOS are projected to exceed KRW 1 trillion in 2024—about four times the 2021 level. And unlike a TV sale, this is the kind of recurring, high-margin revenue that doesn’t require a new factory. It rides on the installed base: roughly 220 million smart TVs LG sold over the past decade.

LG started licensing webOS to other TV makers in 2021, and since then the platform has been adopted by more than 400 brands. Now it’s pushing webOS beyond TVs—into automotive infotainment, digital signage, smart monitors, and gaming projectors. The goal is straightforward: expand platform-based services by more than five times by 2030, and have them contribute 20% of total operating profit.

In late 2024, LG made the shift official through an organizational restructuring designed to accelerate Future Vision 2030. The intent was to increase synergy across divisions, strengthen platform-based services, speed up B2B initiatives, and secure new growth engines. Symbolism mattered, too: all four operating Companies would now incorporate “Solution” in their names—telegraphing that LG wants to be seen less as a device maker and more as an end-to-end provider.

One area got special emphasis: HVAC. LG created a standalone LG Eco Solution Company to push heating, ventilation, and air conditioning as a core pillar of its B2B acceleration strategy.

The logic behind all of this is surprisingly clean. B2B is stickier. An automaker doesn’t swap infotainment suppliers mid-model cycle. A hospital doesn’t refresh its equipment because a new colorway dropped. Data centers still need efficient HVAC systems even when consumers pull back. By shifting the revenue mix toward these longer-cycle, higher-commitment categories, LG is building something it never really had in the smartphone era: resilience.

VIII. The Modern LG Empire: Understanding the Conglomerate Structure

To understand LG Electronics, you have to understand what it sits inside: the broader LG conglomerate, South Korea’s fourth-largest chaebol. LG Corp. is the holding company at the center, with the group’s businesses concentrated in three big arenas—electronics, chemicals, and telecommunications and services. From its 1947 origins, LG grew into a global industrial system, not just a single brand.

LG Corporation operates as a holding company over more than 30 companies spanning electronics, chemicals, and telecom. The key affiliates include LG Electronics (the one we’ve been following), LG Chem (chemicals and battery materials), LG Energy Solution (EV batteries, spun off from LG Chem in 2021), LG Display (display panels), LG Innotek (electronic components), and LG U+ (telecommunications).

That web of companies is both a strength and a source of friction. The upside is flexibility. Cross-subsidization can keep weaker divisions alive long enough for turnarounds or for long-cycle bets to pay off. There are also real operational synergies: LG Display supplies OLED panels that underpin LG Electronics’ premium TV lineup. LG Chem’s know-how in batteries and materials helps enable adjacent ambitions like EV charging. LG Innotek’s components business serves both LG’s internal needs and external customers.

But this structure also comes with the classic chaebol governance tradeoff. From the beginning, control was concentrated in the founding family and reinforced through cross-shareholdings and interconnected boards across affiliates. That can make the group durable and decisive. It can also raise questions about transparency, related-party dynamics, and whether every decision is optimized for each individual company’s minority shareholders—or for the group as a whole.

The current leadership era is fourth-generation, and the succession path was unusual even by chaebol standards. Koo Kwang-mo was adopted by Koo Bon-moo in 2004 after Bon-moo had lost his own eldest son in an accident in 1994. When Koo Bon-moo died of a brain tumor on May 20, 2018, Koo Kwang-mo succeeded him as chairman of LG. He’s also one of the richest people in South Korea.

Since taking office in 2018, Chairman Koo has made a point of on-site management, visiting North America every year except during the COVID-19 pandemic years of 2020 and 2021. Born in 1978, he’s still relatively young for a conglomerate chairman—47 years old today—and his message has been consistent: focus on execution, customer centricity, and transformation.

His style is notably different from the more flamboyant, public-facing model associated with some chaebol heirs. Koo is known for being modest and practical, putting less emphasis on big speeches and more on operational discipline—trying to embed “customer value” into how the organization actually runs.

You can see that progression in his New Year’s messages. In 2019, he made “customers first” the headline. In 2020, it became about identifying and solving customer pain points, with more empathy. In 2021, the emphasis shifted toward understanding customers through hyper-segmentation. In 2022, LG translated that into a broader push for delivering valuable customer experiences.

For investors, it also matters that “LG” isn’t one stock. LG Electronics trades on the Korea Exchange under ticker 066570.KS. LG Corporation, the holding company, controls about 35% of LG Electronics’ shares, with financial institutions, foreign investors, and others owning the rest.

This structure is essential context for analyzing LG Electronics. The company benefits from group-scale advantages and shared capabilities—but it also operates inside a system where related-party relationships and capital allocation have to balance minority shareholder interests with the conglomerate’s long-term strategy.

IX. Playbook: Business & Strategic Lessons

LG Electronics’ journey isn’t just a timeline of products. It’s a case study in how big companies survive, adapt, and sometimes win by walking away. Here are the strategic lessons hiding in plain sight.

The Art of Strategic Retreat

LG’s smartphone exit is one of the clearest examples of a strategic retreat done on purpose, not out of collapse. After 23 straight quarters of losses—eventually totaling $4.5 billion—management faced an uncomfortable reality: this wasn’t a fixable execution issue. The structure of the market had turned against them.

At the top, Apple and Samsung owned the premium segment, with brand gravity and ecosystems that were brutally hard to dislodge. At the bottom, fast-scaling Chinese competitors made the value segment a knife fight, with pricing power and speed that punished anyone stuck in the middle. In that world, even genuinely creative hardware couldn’t change the math.

It’s a move that belongs in the same category as a few other famous retreats. IBM sold its PC business to Lenovo in 2005, escaping a margin-compressed category so it could focus on higher-value services and software. Intel exited smartphone modems in 2019 after failing to match Qualcomm’s scale. The pattern is the point: knowing when a market has become structurally unwinnable is a competitive advantage in itself.

Vertical Integration as Competitive Advantage

LG’s close relationship with LG Display is a classic vertical integration tradeoff: it’s both a weapon and a constraint.

On the upside, it gives LG Electronics reliable access to cutting-edge panels—especially OLED—often with favorable economics and tight coordination between R&D and manufacturing. That matters when your flagship category is defined by the screen.

But integration also reduces flexibility. If a better approach emerges elsewhere, switching suppliers is harder when your advantage is built on internal alignment and shared bets.

Samsung’s path underscores the tension. Its QD-OLED approach—pairing quantum dots with OLED—shows what happens when a competitor designs an alternative specifically to avoid dependence on someone else’s supply chain. For LG, that kind of pivot is more complicated, because the whole stack has been built to make OLED leadership sustainable.

Innovation Without Market Fit

Few phone makers were as willing as LG to try new ideas: modular designs, rollable concepts, rotating dual displays. The company earned real admiration for it.

But the smartphone era delivered a harsh rule: innovation that doesn’t translate into clear, everyday value at an acceptable price doesn’t become a hit. It becomes a curiosity.

The broader takeaway is simple and brutal. Technical achievement is not the same thing as customer value. Customers don’t pay for clever. They pay for solved problems.

B2B Pivot in a B2C Brand

Pivoting from consumer electronics to business solutions isn’t something you accomplish with a new org chart and a slogan. It requires a different muscle: longer product cycles, deeper customer integration, different sales motions, and a culture built around reliability more than launch-day hype.

LG’s vehicle solutions business is the proof point that it can be done. Automotive customers demand close collaboration with engineering teams, multi-year development schedules, and obsessive quality systems. The fact that LG grew this business from essentially nothing into more than $8 billion in annual revenue isn’t just repositioning. It’s capability-building.

Chaebol Resilience

Finally, there’s the chaebol factor. LG’s conglomerate structure creates the ability to cross-subsidize, to tolerate long ramps, and to stay committed to bets that might look irrational on a strict quarter-to-quarter view.

OLED is a perfect example: years of investment and uncertainty before dominance emerged. Vehicle solutions, too: a business that needed time before scale and profitability could show up.

Chaebols are often criticized—sometimes fairly—for governance issues, related-party complexity, and capital allocation questions. But LG’s story highlights the other side of the ledger: endurance has value. In LG’s case, it’s showing up today in OLED leadership and a credible position in EV components.

X. Analysis: Porter's Five Forces & Hamilton's Seven Powers

Porter's Five Forces Analysis

Threat of New Entrants (MODERATE-HIGH)

In LG’s world, “new entrants” depends entirely on where you draw the circle.

At the premium end—OLED TVs—the barriers are real. You need enormous capital to build panel capacity, deep process know-how to get yields up, and the retail and brand positioning to sell a product people will pay up for. LG Display’s scale and experience make that a brutally hard hill for a new player to climb.

But in the middle of consumer electronics, the moat is much shallower. Chinese brands have shown that if you can access the supply chain, manufacture at scale, and price aggressively, you can take share fast. LG’s smartphone era was the clearest proof: the category can turn on incumbents quickly, and newcomers can become giants in a handful of product cycles.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers (LOW-MODERATE)

Vertical integration is one of LG’s quiet superpowers. With LG Display in the group, LG Electronics can secure critical panels internally rather than living at the mercy of an external supplier.

But integration only goes so far. Semiconductors still sit outside LG’s control, from TV processors to automotive controllers. The chip shortages of 2021 and 2022 were a reminder that even a well-integrated manufacturing organization can get bottlenecked by upstream components it can’t make itself.

Bargaining Power of Buyers (HIGH)

For most buyers, switching costs are minimal. A TV is a TV until it isn’t. A washing machine is a washing machine until it breaks. Consumers have endless options, and in the mid-tier, price sensitivity is unforgiving—LG is fighting Samsung, Chinese challengers, and established Western names like Whirlpool.

The escape hatch is premium. If you’re shopping for “best-in-class” OLED, the realistic set of alternatives narrows, and LG earns more pricing power. The same dynamic shows up in high-end appliances like LG Signature, where the customer is buying design, reliability, and status—not just a spec sheet.

Threat of Substitutes (HIGH)

Few companies have lived through substitution as dramatically as LG. The smartphone didn’t just compete with other phones; it swallowed whole categories—cameras, music players, GPS devices, camcorders, and more.

And now the next substitution wave is happening through smart home platforms. Voice assistants and automated routines can make traditional interfaces less relevant, while also creating new surface area for connected appliances and services. LG’s smartphone exit was, in many ways, an acknowledgment of where the center of gravity moved—and how hard it is to compete when you’re not the device people build their digital lives around.

Industry Rivalry (VERY HIGH)

Rivalry is the constant in every LG product line. Samsung is the perennial heavyweight across TVs and appliances. Chinese manufacturers like Haier, Hisense, TCL, and Xiaomi push hard on price and speed. Western incumbents like Whirlpool, GE, and Electrolux remain entrenched in their home markets.

That intensity is a big part of why the B2B pivot matters. In consumer markets, competition often collapses into features and price. In B2B, relationships, integration, reliability, and long product cycles can matter more than who’s cheapest this quarter.

Hamilton's Seven Powers Analysis

Scale Economies

LG is strong where factories and learning curves compound: display manufacturing and home appliances, where a global footprint translates into cost and execution advantages. It was weak in smartphones—exactly why it struggled to match Samsung’s volume machine or the pace and pricing of Chinese competitors.

Network Effects

Hardware alone doesn’t create much network effect. But LG is trying to manufacture some through platforms like webOS and the ThinQ ecosystem. Over the last decade, LG sold about 220 million smart TVs, and it has worked to grow webOS through licensing deals with other manufacturers.

The flywheel is real in theory: more devices attract more content partners, which improves the platform, which attracts more users. In practice, LG’s platform power is still modest compared to the gravitational pull of iOS and Android—but it’s one of the few parts of LG’s business that can scale without scaling factories.

Counter-Positioning

LG’s shift toward B2B is classic counter-positioning. Samsung and many Chinese rivals are built around massive consumer volume and fast refresh cycles. Chasing LG into vehicle infotainment, HVAC, and commercial solutions requires different sales motions, longer timelines, and deeper integration with customers—changes that can be hard to justify internally and can even cannibalize consumer focus.

Switching Costs

In consumer electronics, switching is easy. Most customers don’t feel “locked in” to a TV or an appliance brand.

In B2B, switching becomes painful. Automakers don’t casually replace infotainment suppliers mid-cycle. Hospitals and enterprises don’t rip out equipment systems on a whim. LG’s pivot is partly a move toward markets where relationships and integration create stickier revenue.

Branding

“Life’s Good” is a globally recognized consumer brand, and reliability validation like Consumer Reports can support premium positioning. But LG’s phone business is the reminder that branding isn’t a moat by itself. If the product experience and ecosystem aren’t competitive, brand strength won’t stop churn.

Cornered Resource

LG’s closest thing to a true cornered resource is OLED—both the patents and the accumulated manufacturing expertise. Through Global OLED Technology (GOT), LG holds more than two thousand OLED-related patents and licenses them out. Paired with LG Display’s ability to manufacture at scale, this is an advantage competitors can’t quickly buy or copy.

Process Power

This is where LG quietly shines. Decades of iteration in displays and appliances created deep manufacturing process knowledge—yield management, quality systems, supply chain discipline. The ZKW acquisition added hard-won expertise in automotive lighting. These aren’t things you spin up in a year. They compound, and they show up as execution advantages that competitors struggle to replicate.

Key Performance Indicators to Monitor

For investors tracking LG Electronics, three KPIs deserve the most attention:

-

B2B Revenue as Percentage of Total Revenue: Around 35% recently, with a target of 45% by 2030. This is the cleanest signal of whether the portfolio is truly shifting from cyclical consumer demand to stickier, relationship-driven revenue.

-

Vehicle Solutions Order Backlog Growth: Backlog is forward visibility—and a proxy for competitive momentum. A rising backlog suggests LG is winning major programs; a shrinking backlog is often the earliest warning that share is slipping.

-

webOS Platform Revenue Growth: This is LG’s clearest path to margin expansion. Advertising and content revenue riding on a massive installed base can change the earnings profile in a way hardware alone rarely can. The question isn’t whether webOS exists—it’s whether it scales into a meaningful services business alongside LG’s manufacturing core.

XI. Conclusion: Life's Good When You Know What You're Not

From face cream in a war-scarred Korea to OLED dominance and a real seat at the table in automotive electronics, LG’s nearly eight-decade journey points to a simple truth about corporate longevity: it’s not just about what you’re willing to build. It’s about what you’re willing to stop being.

LG was never destined to win in smartphones. The structure of the market hardened into something brutal: Apple and Samsung took most of the profit at the top, while Chinese manufacturers turned the middle and low end into a relentless scale-and-price grind. In that world, there was no stable lane for a company that couldn’t, or wouldn’t, pay the full cost of competing at the very top. The $4.5 billion in cumulative losses didn’t just mark a failure. It clarified reality.

What LG is—what it has been since Koo In-hwoi started mixing Lucky Cream in 1947—is a company built for manufacturing excellence in categories where the difference between good and great is obvious. OLED televisions. Premium appliances. Complex, safety-critical automotive components. These markets reward patient engineering, process discipline, and long-term investment. They look a lot more like LG’s DNA than the smartphone treadmill ever did.

And you can see the payoff. In 2024, LG hit its highest annual revenue ever. Its home appliance and vehicle solutions businesses extended their growth streaks, helping drive record results. The smartphone exit wasn’t an act of retreat so much as an act of reallocation—moving capital and talent from a business with no path to leadership into categories where leadership is possible.

The transformation still has miles to go. Hitting the 2030 vision—around 45% B2B revenue, a much larger vehicle solutions business, and platform services contributing a meaningful share of operating profit—will require sustained execution. The automotive push has to navigate EV adoption headwinds. Chinese competitors will keep moving upmarket in appliances and displays. And webOS-driven services have to scale without turning the user experience into a tax.

But the direction is unmistakable. The org changes are in motion. The portfolio is shifting. And the results suggest the pivot is already working.

LG’s story isn’t about never making mistakes. It’s about learning which battles are worth fighting—and having the discipline to walk away from the ones that aren’t. Life’s good, indeed, when you let go of what’s not working and double down on where you can actually win.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music