Hyundai Rotem: From Crisis Consolidation to Korea's Defense Juggernaut

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

Picture this: December 2022, the port of Gdańsk on Poland’s Baltic coast. Under heavy security, a ship from South Korea eases up to the docks and begins unloading its cargo: ten K2 Black Panther main battle tanks, freshly painted in Polish Army green.

Just months earlier, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine had detonated Europe’s post–Cold War assumptions. Poland, bordering Ukraine, had donated hundreds of Soviet-era T-72s to Kyiv—and suddenly found itself short on armor at the exact moment armor mattered again. Those tanks rolling onto Polish soil weren’t just new hardware. They were a line in the sand: South Korea’s first export of main battle tanks, shipped by a company most people outside defense and rail had never heard of—Hyundai Rotem.

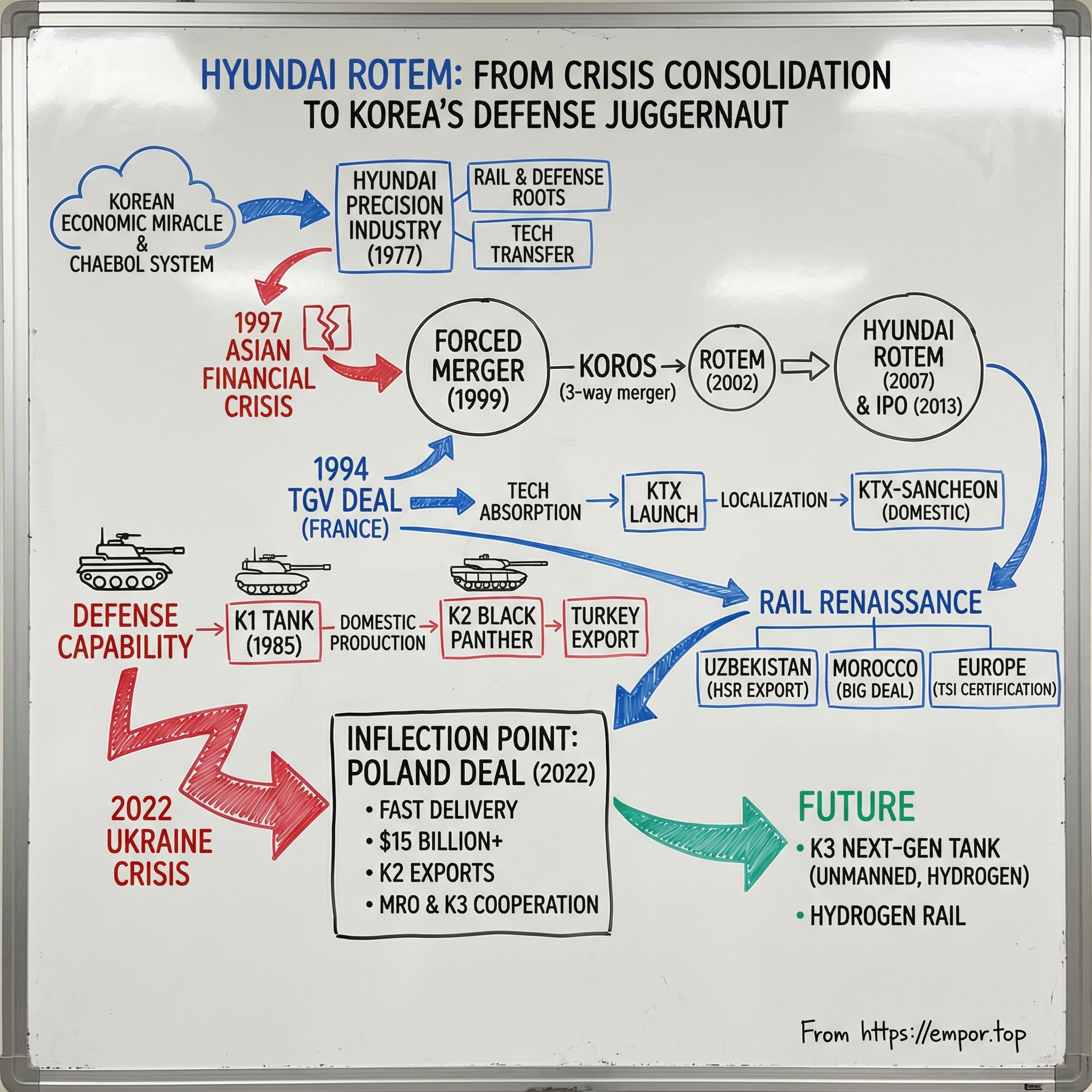

That’s the question at the heart of this story: how did a company created through crisis-era chaebol restructuring—a forced 1999 merger of three rail divisions—turn into one of the world’s most energetic defense exporters, while also remaining a serious player in global rail?

Because in the last few years, Hyundai Rotem didn’t just grow. It snapped into a new identity. In 2024, the company reported 4.38 trillion won in revenue, up from 3.59 trillion the year before. Profit surged even faster, rising to 406.89 billion won. Hyundai Rotem has learned how to ride two powerful waves at once: democratic rearmament in an era of renewed great-power competition, and the global push to build more rail as a practical path to decarbonization.

The business today reflects that transformation. Hyundai Rotem is a South Korean manufacturer of rolling stock, railway signaling, defense systems, and plant equipment. It’s an affiliate of Hyundai Motor Group, operates in more than 50 countries, and had over 4,100 employees as of 2024. But the mix is what really matters: defense now drives roughly 54% of sales, rail about 34%, and plant and machinery the rest. For a company born in rail, that is a near inversion of its original center of gravity.

The thesis we’ll test is simple: Hyundai Rotem may be the cleanest case study of how Korean industrial policy, patient technology transfer, and fast adaptation to geopolitical shock can turn a government-directed consolidation—something many Western observers would dismiss as inefficient—into a globally competitive export machine. This story is about building capability instead of just buying products. It’s about how crisis can create openings that decades of careful planning can’t. And it’s about a company that went from protected domestic supplier to a genuine threat to legacy incumbents—right when the world’s demand curve changed.

So here’s our roadmap. We’ll start with the Korean economic miracle and the chaebol system that built Hyundai’s industrial DNA. Then we’ll move into the Asian financial crisis—the crucible that forced the merger that created Hyundai Rotem in the first place. From there: the long, disciplined years of technology absorption in high-speed rail and armored vehicles. And finally, the inflection point—Ukraine—when timelines collapsed, demand spiked, and Hyundai Rotem found itself ready for a moment no one could have predicted.

II. The Korean Economic Miracle & Chaebol System Context

To understand Hyundai Rotem, you first have to understand the system that produced it—a political economy that can look, to outsiders, like equal parts confusing, infuriating, and brilliant.

In 1961, South Korea was still desperately poor. Within a few decades it had vaulted into the OECD. That leap—what Koreans call the “Miracle on the Han River”—didn’t happen by accident. It was built through a distinctly Korean version of state-directed capitalism, where the government picked priorities, pushed capital in that direction, and expected results. Out of that model came the chaebols: massive, family-controlled conglomerates that became the country’s industrial engines.

The playbook was straightforward. Through five-year economic development plans in the 1960s and 1970s, the government targeted exports and the buildup of heavy and chemical industries. In return for performance, it offered performance-enhancing fuel: long-term loans at low rates, subsidies, and political support. For decades, groups like Samsung, Hyundai, and LG used that environment to grow fast and diversify aggressively.

Hyundai was the archetype. The original Hyundai Group—before it splintered into today’s Hyundai Motor, Hyundai Heavy Industries, and others—grew under founder Chung Ju-yung into a sprawling industrial empire by the 1990s: construction, shipbuilding, autos, electronics, and more. Chung’s reputation was built on audacity, and his most famous move captures the era perfectly: he once used a 500-won note—printed with an image of a ship—to persuade Barclays to finance Korea’s first major shipyard. The pitch, essentially, was: here’s the ship; now let us go build it.

Inside that Hyundai machine, the roots of Hyundai Rotem begin in 1977, when Hyundai Precision Industry was established as a subsidiary of Hyundai Motor Company. The timing wasn’t a coincidence. The government was actively steering the country toward heavy industry, and Hyundai saw a strategic opening at the intersection of transportation equipment and defense.

The early milestones came in quick succession. In 1979, the company began its plant business and manufactured Korea’s first diesel locomotive—an early declaration that Korea intended to stop depending on foreign suppliers for critical transportation hardware. Then, in 1985, came something even more consequential: the K1 main battle tank. The K1’s roll-out ceremony on October 24, 1985 marked a new kind of industrial sovereignty—South Korea could now produce its own armor, reducing reliance on the United States for a capability central to deterring North Korea.

That’s the key point: from the beginning, this was a two-track company—rolling stock and defense—because Korea was a two-track country. Rail was the backbone of an export economy, moving people and goods through dense corridors to ports. Tanks were a survival requirement, with a hostile neighbor and a frontline that sat uncomfortably close to Seoul. And on the factory floor, the overlap was real. Heavy fabrication, precision welding, powertrain engineering—skills that translate surprisingly well from train bodies to tank hulls.

The strategic logic behind all of it was simple, and hard-earned: dependence creates vulnerability. In a crisis, foreign supply chains can be delayed, blocked, or priced like a monopoly. South Korea couldn’t afford that—neither in war, where equipment has to be repaired and replaced quickly, nor in peace, where infrastructure has to expand and operate reliably to keep the export machine humming.

This context explains what can otherwise look strange later in the story—why the government was willing to reshape industries by force, why it backed long-cycle technology development, and why export success became almost a matter of national strategy. Hyundai Rotem wasn’t built as a “normal company” for a “normal market.” It was built, from the start, as a capability the country intended to have—and keep.

III. The 1994 TGV Deal: Learning from the French Masters

By the early 1990s, South Korea had a good problem: the country was booming. The bad news was that the infrastructure underpinning that boom—especially rail—was starting to creak.

Nowhere was the strain more obvious than the Gyeongbu corridor between Seoul and Busan. This was the spine of the Korean economy, concentrating the bulk of the population and industrial activity. The expressway was jammed. The conventional rail line was basically tapped out. If Korea wanted to keep growing, it needed a step change in mobility.

The answer was already on the world stage. Japan had unveiled the Shinkansen back in 1964. France followed with the TGV in 1981. High-speed rail wasn’t science fiction anymore. It was a proven national productivity machine. Korea wanted in.

But wanting a high-speed network and being able to build one are two very different things. Korea didn’t yet have the engineering base, the manufacturing processes, or the systems integration know-how to produce high-speed trains on its own. So the real question wasn’t whether to import technology—it was how.

Korea could have taken the easy route: buy trains off the shelf, plug them into a new line, and call it a day. Plenty of countries did exactly that. Korea chose a harder path, one shaped by a broader national instinct you can see across its industries: don’t just buy the product. Buy the capability.

So when the government went shopping for high-speed rail, it set the rules up front. Technology transfer wasn’t a nice-to-have; it was the point. Localization wasn’t symbolic; it was enforced.

In 1994, that process ended with the Korea High Speed Rail Construction Authority awarding the rolling stock contract to the Alstom-led Korea TGV Consortium. At the center was GEC-Alsthom—today’s Alstom—the builder of France’s TGV. On the Korean side was Hyundai Precision Industry, the predecessor to Hyundai Rotem, alongside other local partners. The order: 46 trainsets based on the TGV Réseau design.

The deal was enormous—about $2.1 billion—but the headline wasn’t the price tag. It was the structure. The agreement embedded joint ventures, training, and phased domestic production, backed by a hard requirement: localize at least half of manufacturing cost, or pay a 20% penalty. That clause told you exactly what Korea was buying.

The manufacturing plan turned the contract into a classroom. The first twelve trainsets were built in France at Alstom’s Belfort facility between 1997 and 2000. Then the center of gravity shifted. The remaining 34 were produced in Korea between 2002 and 2003 at Hyundai Rotem’s Changwon plant—moving from import to assembly to real domestic production.

And that’s when the flywheel started turning. Korean engineers worked shoulder-to-shoulder with French counterparts, learning not just how to fabricate a carbody, but how to integrate a high-speed system—materials, tolerances, testing regimes, quality control, documentation, supplier qualification. Korean component makers learned to hit French specifications. The industrial base tightened, upgraded, and leveled up.

What’s striking is how familiar this playbook already was. While Korea was absorbing high-speed rail technology from France, it was also learning tank production through the K1 program with the United States. Different products, same strategy: start with licensed production, push domestic content higher, build indigenous design competence, then eventually stand on your own—and export.

That’s the strategic insight Korean planners had internalized early: complex systems come and go, but the ability to design and manufacture them is the real asset. Trains age out. Standards evolve. New competitors emerge. But an ecosystem that can build high-speed rail—people, processes, suppliers, testing infrastructure—is durable competitive advantage.

In other words, Korea wasn’t really buying 46 trainsets. It was buying the future.

IV. The Asian Financial Crisis: Crucible of Consolidation

— KEY INFLECTION POINT #1 —

On July 2, 1997, Thailand abandoned its currency peg. The baht plunged. And what started as a Bangkok problem turned into a regional reckoning. In a matter of months, the crisis ricocheted across Asia—currencies buckled, banks failed, and companies that had looked unstoppable suddenly couldn’t roll over their debt.

South Korea got hit hard. The won fell sharply. The stock market was cut in half. Unemployment spiked. The entire growth model—built on confidence, leverage, and momentum—ran straight into a wall.

And when the smoke started to clear, the chaebols were in the crosshairs.

The government, much of the public, and the IMF converged on the same diagnosis: the conglomerates had become too indebted, too sprawling, and too opaque. The very traits that had powered Korea’s rise—easy credit, rapid diversification, and a tolerance for high leverage—now looked like systemic risk. Many groups had borrowed heavily, including in foreign currencies, and expanded into businesses that didn’t reinforce each other. When the funding window slammed shut, the weaknesses were suddenly visible.

The IMF bailout came with strings. In January 1998, President Kim Dae-jung imposed the Five-Point Accord on the five largest chaebols—Hyundai, Samsung, Daewoo, LG, and SK—forcing them to narrow their focus to three to five core businesses. The deal wasn’t subtle: non-core and uncompetitive affiliates would be sold, shut down, or merged into stronger counterparts, even if that meant combining former rivals.

The changes were swift and sweeping. By 2000, the top 30 chaebol groups had cut their affiliate count dramatically, shrinking from 819 companies to 544. That might sound like accounting trivia, but in Korea it marked something close to a cultural break. Before the crisis, chaebols almost never divested. Now they were being compelled to do it at scale.

Then came the most visible casualty: Daewoo. In mid-1999, the group collapsed under an estimated $80 billion in unpaid debt—at the time, the largest corporate bankruptcy in history. Daewoo had expanded aggressively across industries, and its founder, Kim Woo-choong, went from celebrated builder to fugitive, later sentenced to prison for accounting fraud. If anyone needed a symbol that the old era was over, Daewoo provided it.

Out of this wreckage came the conditions for Hyundai Rotem’s birth.

In rail, the government took a blunt but strategically coherent step: consolidation. On July 1, 1999, Korea Rolling Stock Corporation—KOROS—was formed through the merger of the rolling stock divisions of Hanjin Heavy Industries, Daewoo Heavy Industries, and Hyundai Precision Industry. Three competitors, one company.

And then, in 2000, Hyundai Precision Industry transferred its defense and plant businesses into KOROS—effectively positioning KOROS as an affiliate of Hyundai Motor Company.

This is where the crisis turns from economic disaster into industrial design. Because the “genius” of the forced merger—yes, genius is fair—was that it turned duplication into scale. Before the crisis, Korea had multiple train builders chasing the same domestic orders, each too small to be truly world-class, each repeating the same investments in tooling, engineering, and production. The crisis created the political cover to do what had long made industrial sense but had been politically difficult: merge, rationalize, and build a national champion.

Korea’s macro recovery in 1998 and 1999 was faster than many outsiders expected. But the restructuring left permanent fingerprints. The chaebols emerged leaner and more focused, entire industries were reshaped, and KOROS entered the world with a near-monopoly in Korean rolling stock—plus an integrated base of heavy manufacturing capabilities that would matter far beyond trains.

The counterintuitive takeaway is that the darkest moments can create the most durable platforms. KOROS—later Hyundai Rotem—wasn’t born from a grand entrepreneurial vision. It was born from enforced consolidation. But it inherited the combined capabilities of three rivals, unified production, and suddenly had the scale to absorb technology, standardize quality, and eventually compete globally.

V. Identity Formation: From KOROS to Rotem to Hyundai Rotem

KOROS was a child of crisis—stitched together from three former rivals with different corporate cultures, different factory systems, and different unions. On paper, consolidation created a national champion. In reality, it created years of integration work. And even the ownership still had to settle.

That started to resolve in August 2001. After the Daewoo Group dissolved, Daewoo Heavy Industries sold its stake in KOROS to Hyundai Mobis, which became the majority shareholder. Soon after, the company made its next identity move. On January 1, 2002, KOROS renamed itself Rotem Company—short for “Railroading Technology System.”

The rebrand wasn’t cosmetic. “Rotem” was designed to be neutral—separate from the legacy names of Hyundai, Daewoo, and Hanjin—while signaling what the company wanted to be: not just a manufacturer, but a technology-driven rail systems player. Still, the questions hung in the air. Rotem was profitable, but small by global rolling-stock standards. It relied heavily on the home market. And it had yet to prove it could win abroad consistently.

Then came outside validation. In 2006, Morgan Stanley became a minority shareholder by purchasing shares from Hyundai Motor Company, and it remained a shareholder until 2018. Hanjin Heavy Industries also sold its stake to Morgan Stanley, leaving Hyundai Motor Group as the only remaining pre-merger corporate shareholder. For Rotem, having a major Western institution on the cap table brought more than capital—it brought a kind of credibility that helped in international conversations where “Korean rolling stock” still sounded like an experiment.

In December 2007, the company made the opposite branding choice: it leaned into the chaebol. Rotem added “Hyundai” to its name to reflect its affiliation with Hyundai Motor Group. It was a practical move. Hyundai was becoming a globally recognized name, and that recognition mattered when you were trying to sell trains and defense systems into markets that defaulted to familiar incumbents.

In October 2013, Hyundai Rotem listed its shares on the Korea Exchange. Public markets brought liquidity and visibility—plus the pressure cooker of analyst scrutiny and quarterly expectations.

But the most important milestone of this era wasn’t a cap-table event. It was a train.

On April 1, 2004, the KTX began revenue service, launching on the Seoul–Busan and Seoul–Mokpo/Gwangju routes. Based on France’s TGV and adapted to Korean operating conditions, KTX didn’t just improve travel—it compressed the country. The Seoul-to-Busan trip dropped to a little over two hours, turning what used to feel like a long-distance journey into something closer to a commute. For Korea, it was a national statement: within roughly half a century of the Korean War, the country was now running one of the world’s most advanced rail systems.

For Hyundai Rotem, though, the bigger story was what happened after the launch. The first generation of KTX came from imported technology. The next step was making that technology Korean.

That path ran through a national R&D push known as the G7 program. Starting in 1996, government research agencies, universities, and private companies joined forces to develop domestic high-speed rail technology, aiming at a next-generation train capable of 350 km/h. The work built on the TGV technology Korea had absorbed, but it pushed beyond it—new motors, power electronics, and braking systems; aluminum passenger cars to reduce weight; and a redesigned nose to cut aerodynamic drag.

The proof came on the test track. The experimental HSR-350x began trials in the early 2000s and, on December 16, 2004, set South Korea’s rail speed record at 352.4 km/h.

Then came the moment that made the whole technology-transfer strategy feel inevitable in hindsight. In October 2005, Korail opened competitive bidding for new trains. In December, Rotem—offering a commercial version of the HSR-350x—was chosen over Alstom for the order. Eleven years after Korea signed the TGV technology transfer deal, the domestic builder beat the original teacher in an open competition.

That win wasn’t just pride. It meant Korea’s “localization” had moved from a contract requirement to a competitive edge, with domestic added value rising sharply from the first KTX generation to the next.

In November 2008, Hyundai Rotem rolled out the KTX-Sancheon, the country’s first domestically developed high-speed train in commercial service. Built by Hyundai Rotem and operated by Korail and SR Corporation, it runs at a maximum operational speed of 305 km/h. More importantly, it marked a crossing of the line: Korea had gone from assembling imported designs to fielding its own.

For anyone looking at Hyundai Rotem today, this stretch of the story is the template. Korea sets a national capability goal. The government, academia, and industry collaborate for years. The company absorbs foreign know-how, then iterates until it can outbid the foreign supplier. And once the domestic product is real, it becomes exportable.

Next, Hyundai Rotem would run that same playbook again—this time not on rails, but on tracks.

VI. The Defense Business: From K1 to K2 Black Panther

While Hyundai Rotem was grinding through the long apprenticeship of high-speed rail—transfer, localize, improve—the company’s other line of business was quietly building a different kind of credibility. The defense side was learning how to make the hardest things a country can make, at scale, under pressure. And over time, that work would move from “important” to “defining.”

The modern story begins in 1985, when the company developed the K1 main battle tank and held its roll-out ceremony on October 24. For South Korea, the K1 was a watershed: a domestically produced tank, built by Korean factories and maintained by Korean technicians. But “indigenous” came with an asterisk. Just like the early KTX sets, the K1 leaned heavily on foreign technology—especially American assistance—and a meaningful share of critical subsystems still came from abroad.

That’s not a knock. It’s the point. The K1 created the capability base that matters most in defense: the ability to manufacture, sustain, upgrade, and iterate. Once you can build it at home, you can improve it at home. And once you can improve it at home, you can start to compete.

The next leap was the K2 Black Panther. On paper, the K2 reads like South Korea’s statement that it wasn’t just catching up anymore. It’s a 55-ton main battle tank built around a 120 mm L/55 smoothbore gun with an autoloader, paired with a 7.62 mm coaxial machine gun and a 12.7 mm heavy machine gun up top. Power comes from a 1,500-horsepower diesel engine and automatic transmission, pushing it to about 70 km/h. And underneath, it uses a hydropneumatic suspension system—Hyundai Rotem calls it the In-arm Suspension Unit—that can adjust hull height and posture to improve off-road mobility and stability.

The program began in the 1990s, shaped by a specific view of modern warfare: fast, networked, and three-dimensional, where sensors, fire control, and maneuver matter as much as armor thickness. This wasn’t a warmed-over K1. It was a clean-sheet effort meant to sit in the same conversation as the world’s best.

But the reality of building “the best” is that the hardest parts don’t care about ambition. And for the K2, the hardest part was the powerpack—engine plus transmission. In 2012, the domestic powerpack didn’t meet required operational capability. Rather than stall the entire program, South Korea chose a pragmatic workaround. In April 2012, DAPA announced the first 100 K2s would use the German-made Euro Powerpack. The first 15 entered service in June 2014, and by 2015 the first 100 vehicles were using a German MTU powerpack.

That decision is a perfect snapshot of Korea’s industrial strategy in practice: be stubborn about the end state—self-sufficiency—but flexible about the path. Heavy tank drivetrains are among the most demanding mechanical systems on earth. Korea fell short on the initial timeline, then kept the program moving with proven foreign components while continuing domestic development rather than letting perfection freeze progress.

Over the 2010s, the Republic of Korea Army kept buying. It has ordered four K2 production batches from Hyundai Rotem, totaling more than 300 vehicles. The most recent batch was ordered in 2024, with deliveries scheduled through 2028. In total, the RoKA has a requirement for about 600 K2s.

Those domestic orders mattered for more than national defense. They created the production volume to tighten manufacturing, improve quality, and turn the K2 from an impressive prototype into a repeatable product. Still, the real validation—the kind that reshapes a company’s trajectory—would come from exports. And for that, Hyundai Rotem had to wait for the world to change.

Before Poland, there was Turkey.

In June 2007, South Korea and Turkey negotiated an arms deal worth ₩500 billion tied to Turkey’s Altay tank development. On July 29, 2008, Hyundai Rotem and Turkey’s Otokar signed a contract for design assistance and technology transfer. The Altay would go on to become Turkey’s indigenous main battle tank, incorporating K2 design elements along with Korean engineering support.

The Turkey deal was an early signal that Korea’s defense industry had crossed an invisible threshold. Turkey is a NATO member with access to American and European options. Partnering with Hyundai Rotem wasn’t charity, and it wasn’t symbolism. It was a commercial choice—based on capability, economics, and the growing sense that Korean hardware could be trusted.

VII. The Global Rail Push: Successes and Stumbles

By the 2000s and 2010s, Hyundai Rotem was no longer just “KTX’s builder.” It was out in the world, winning real rolling-stock contracts across Asia, Australia, and North America. Its export portfolio ranged from New South Wales D sets for intercity services around Sydney, to K-Stock and R-Stock EMUs for Hong Kong’s MTR, commuter EMUs for Taiwan, trains for the Delhi Metro, and automated trains for Vancouver’s Canada Line. In the United States, it delivered 120 Silverliner V commuter railcars for SEPTA in the Philadelphia area and, as of early 2025, had also delivered 66 Silverliner Vs for RTD’s A Line.

On paper, it looked like the playbook was working again: take hard-won domestic capability, package it into a product, and go compete globally. Hyundai Rotem could credibly offer a wide range—high-speed sets, metro cars, and regional trains. But this era also exposed a truth every industrial exporter eventually learns: building trains is hard; building trains to someone else’s rules, with someone else’s supply chain, is harder.

Nowhere did that hit more painfully than the United States.

SEPTA’s Silverliner V order was huge for Hyundai Rotem’s credibility: 120 cars for $274 million. It was also, in hindsight, an object lesson in what can go wrong when a new entrant wins a major contract in a heavily regulated market. When Hyundai Rotem first bid in 2004—then operating under the name United Transit Systems (UTS)—SEPTA’s engineering staff gave it the lowest technical rating among the four bids. But the price was the lowest, and SEPTA’s board awarded the contract to the newcomer.

The project quickly turned into a grind. Hyundai Rotem had limited experience building railcars in America, limited familiarity with U.S. federal railroad regulations, and little footing in U.S. supply chains. The timeline slipped amid contract disputes, design delays, and the added complexity of needing to build a factory in South Philadelphia. The cars ultimately arrived in the U.S. on February 28, 2010—years later than planned—and Hyundai Rotem paid about $13 million in late fees.

Then came the moment that turned “late delivery” into “reputation crisis.” On July 2, 2016, SEPTA pulled all 120 Silverliner V cars—about a third of its fleet—from service after inspectors found fatigue cracks in the trucks. The cars were still under warranty, and cracks were discovered on 115 of the 120 vehicles. Hyundai Rotem told The Inquirer the problems were tied to improper welding, and noted that the welding work had been subcontracted to HiCorp., a company based in Zelienople, Pennsylvania.

Hyundai Rotem representatives later acknowledged a combination of design errors and production flaws. In the U.S. rail market—where agencies remember vendor performance for decades—this wasn’t a simple defect. It raised doubts about quality control and systems integration, and it made future sales harder.

And it wasn’t the only export program under strain. The Istanbul Marmaray contract ran into its own problems. Chronic delays, workmanship issues, material shortages, and the death of Hyundai Rotem CEO M.H. Lee in November 2012 all contributed to a grim datapoint: by the end of 2012, only four cars had been delivered.

These were the growing pains of globalization. Building for Korean operators, with Korean suppliers, under Korean standards, is fundamentally different from delivering into markets where regulations, labor practices, subcontracting norms, and customer expectations are all different—and where the buyer has far less patience for “learning on the job.”

Still, Hyundai Rotem remained a meaningful player in global rolling stock. It kept competing and kept winning sizable work, including the Australian NIF double-decker train project worth 1.4 trillion won, the Australian Queensland train supply contract valued at 1.3 trillion won, and the Los Angeles Metro train contract worth 900 billion won tied to the 2028 Los Angeles Summer Olympics.

But context matters. Globally, Hyundai Rotem sat at roughly a 2% market share—about the world’s eighth-largest rolling-stock maker. The top of the table was dominated by giants: China’s CRRC at 24.8%, France’s Alstom at 15.4%, and Germany’s Siemens at 7.9%.

Rail was—and is—an important business for Hyundai Rotem. But by itself, it wasn’t going to turn the company into a global juggernaut. That transformation would require something else. And it arrived in February 2022.

VIII. The Ukraine Inflection: Defense Export Explosion

— KEY INFLECTION POINT #2 —

February 24, 2022. Russian tanks rolled across the Ukrainian border, and Europe’s post–Cold War security order shattered overnight. Within weeks, governments that had spent decades cashing in a “peace dividend” found themselves staring at an urgent question: how quickly can we rebuild combat power?

The answer, across much of Europe, was: not quickly.

Three decades of consolidation and downsizing had left defense industries optimized for small, steady procurement—not sudden, large-scale demand. Factories were lean. Supplier bases were thin. Order books were already full. If you wanted tanks or artillery now, you weren’t just waiting. You were joining a queue measured in years.

Enter South Korea—and Hyundai Rotem.

No country felt the pressure more intensely than Poland. It sits on NATO’s eastern flank, borders Ukraine, and had donated hundreds of Soviet-era tanks to Kyiv. Poland needed replacements fast, and traditional European suppliers couldn’t match the timeline.

In July 2022, Poland and South Korea struck a sweeping package deal valued at around $15 billion. Poland agreed to buy 980 K2 tanks, 648 K9 self-propelled howitzers, and 48 FA-50 light combat aircraft. For Hyundai Rotem, the headline was the K2: under the preliminary contract signed in 2022, it would supply 180 K2 Black Panthers—South Korea’s first-ever export of main battle tanks.

And then Hyundai Rotem did the thing that changed how the market saw Korea: it delivered.

The first 10 K2s arrived in Poland on December 5, 2022—roughly six months after the agreement was signed—and were delivered to the 20th Mechanised Brigade on December 9.

Six months from signature to tanks on the ground is almost unnatural in this industry. The difference wasn’t a magical product. It was readiness: Korean production lines that hadn’t gone cold, supply chains that could still move, and a manufacturing culture built around hitting schedules.

Deliveries continued. By April 2024, Hyundai Rotem had delivered 46 tanks, with the remainder scheduled in stages, aiming to complete the initial 180-tank order by the end of 2025.

But that first contract turned out to be the opening act.

In July 2025, Hyundai Rotem concluded a second Poland deal: another 180 K2 tanks, valued at $6.5 billion—Korea’s largest single defense export contract since the $3.5 billion surface-to-air missile deal signed with the UAE in 2022.

The obvious question was why the second order cost so much more. The answer was that it wasn’t just about shipping tanks. The new contract, worth about 9 trillion won, roughly doubled the value of the first (about 4.5 trillion won) because it included MRO-related technology transfer—maintenance, repair, and overhaul capabilities that anchor a long-term industrial relationship.

The agreement covered deliveries from 2026 to 2030. Of the 180 tanks, 116 in the current K2GF configuration were to be delivered between 2026 and 2027, with the remaining 64 delivered as the upgraded K2PL variant between 2028 and 2030. The K2PL configuration added protection and survivability upgrades, including an Active Protection System, an anti-drone system, and additional armor, along with other modifications informed by the K2GF.

Just as importantly, Poland wasn’t only buying hardware; it was buying industrial participation. Final assembly of 61 K2PL tanks was slated for ZM Bumar-Łabędy, giving Poland a domestic production boost and moving Hyundai Rotem closer to its bigger ambition: making Poland a European hub for production and service.

That ambition was explicit. The contract included joint cooperation to build manufacturing facilities in Poland for production and maintenance of K2s, and even cooperation tied to production of the next-generation K3 tank. The idea was straightforward: a Poland-based footprint that could support sales and sustainment across Europe.

The Poland momentum opened other doors, too—especially on survivability tech. Hyundai Rotem signed an agreement to integrate Rafael Advanced Defense Systems’ Trophy active protection system onto the K2, the first time the South Korean-made tank would carry such a system. The agreement with Rafael was signed in September 2025 at a defense exhibition in Poland, and it covered both the baseline K2 and the K2PL variant. Under the deal, Trophy—described as the world’s only operational active protection system—would be installed on K2s and later on additional South Korean platforms.

By this point, Poland had ordered 360 K2 tanks, including at least 60 K2PL variants, with the first 180 due by the end of 2025. And the ceiling was higher still: a framework agreement between Poland and South Korea covered the provision of up to 1,000 K2 tanks, with increasing production in Poland over time.

Beyond Europe, the export story kept spreading. In a $60 million deal commissioned by the Peruvian Army Arsenal in May 2024 and facilitated by South Korea’s STX Corporation, Hyundai Rotem delivered K808 White Tiger wheeled armored personnel carriers to Peru—30 vehicles supplied through STX.

Peru also signaled something even bigger than a one-time purchase. As part of its modernization strategy, Hyundai Rotem planned to establish an assembly plant in Peru for K2 Black Panther tanks and K808 White Tiger armored vehicles, with an announced initial investment of USD 270 million to build the industrial complex. Under an agreement with Peru, Hyundai Rotem would supply 54 K2 Black Panthers and 141 K808 White Tigers through future performance contracts.

The Ukraine shock revealed a brutal truth about defense markets: when the world changes, demand doesn’t ramp gradually—it snaps. In that kind of environment, the winners aren’t always the companies with the fanciest brochures. They’re the companies that have kept capacity alive, kept supply chains working, and built products good enough to be trusted.

Hyundai Rotem had spent decades building exactly that. When the moment arrived, it was ready.

IX. Rail Renaissance: From Uzbekistan to Morocco

— KEY INFLECTION POINT #3 —

While defense dominated the headlines, Hyundai Rotem’s rail business was finally landing the kind of wins the company had been building toward since the 1994 TGV technology-transfer deal. After decades of learning, localizing, and iterating, Korea wasn’t just operating world-class high-speed rail. It was ready to export it.

That proof arrived in June 2024, during President Yoon Suk Yeol’s state visit to Uzbekistan. At a ceremony in Tashkent attended by Yoon and Uzbek President Shavkat Mirziyoyev, Uzbekistan Railways and Hyundai Rotem signed a contract worth about 270 billion won (around $195 million) for six high-speed trainsets—42 cars total—designed to operate at up to 250 km/h.

For South Korea, it was a milestone: the first export of high-speed trains built with homegrown technology. And it carried a satisfying symmetry. Roughly two decades after KTX entered service with French assistance in 2004, the country was now selling its own high-speed platform abroad.

Hyundai Rotem then did something that matters almost as much as the signature: it built and shipped on time. After completing production ahead of schedule, the company held a departure ceremony in December 2025 at Masan Port in Changwon for the first shipment to Uzbekistan. The initial trainset—seven cars—was finished just 17 months after the deal was signed.

Symbolically, Uzbekistan was huge. But commercially, it was the warm-up.

The transformational moment came next, in Morocco.

In February 2025, Hyundai Rotem secured a 2.2 trillion won (about $1.53 billion) contract with Morocco’s national railway operator, ONCF, to supply double-decker electric trains. It was Hyundai Rotem’s first entry into the Moroccan market—and the largest single railway supply agreement in the company’s history.

The order covered 110 double-decker trains designed for 160 km/h operations, aimed at rapid shuttle service linking Kenitra, Rabat, and Casablanca, plus regional routes. The timing was also on Morocco’s side: as the country prepared to co-host the 2030 FIFA World Cup with Spain and Portugal, infrastructure investment had new urgency.

A key feature of the deal was technology transfer. Hyundai Rotem emphasized collaboration with ONCF, including production work in Morocco to support local industry and workforce development. Back in Korea, the ripple effects mattered too: the company expected much of the parts supply to come from Korea’s small and mid-sized firms—pulling the broader domestic rail ecosystem along with it.

More importantly, Morocco showed what Hyundai Rotem had been chasing for years: it could win major international tenders against European incumbents, in a market where European firms traditionally set the standard.

It also highlighted how Korea likes to win overseas infrastructure: as a coordinated national effort. The signing was credited to public-private teamwork, with support that included Korea’s Economic Development Cooperation Fund, the country’s low-interest infrastructure loan program for developing nations. In other words, it wasn’t just a train bid. It was a national package.

The scale was meaningful for Hyundai Rotem’s business, too. The contract was sizable relative to the company’s recent annual revenue, and it helped push backlog to a new level—rising to 14.1 trillion won by the end of 2024, up from 7.1 trillion won in 2020. Rail wasn’t simply “the other division” anymore. It was building real momentum.

Then came the final piece needed to play in the industry’s most demanding arena: Europe.

On September 24, 2024, Hyundai Rotem obtained European Technical Specification for Interoperability design certification for its EMU-320 high-speed train through TÜV Rheinland, a German certification authority. TSI certification is a gatekeeper credential—an essential qualification for competing for many European railway projects—and winning it signaled that Hyundai Rotem could meet Europe’s stringent technical and interoperability requirements.

Put those threads together—Uzbekistan as the first export of Korean high-speed technology, Morocco as a scale breakthrough, and TSI certification as the passport into Europe—and the picture starts to look very different. Hyundai Rotem was no longer just exporting trains. It was exporting a mature industrial capability.

And the strategy around rail was evolving in parallel. Cooperation with KIND (Korea Infrastructure Development) reflected a shift away from one-off rolling stock sales and toward integrated public-private partnership projects—where financing, construction, operations, and maintenance are part of the same long arc. It’s a way to capture more of the value chain and turn trains into longer-duration revenue.

Finally, the company kept one eye on what could come after electrification: hydrogen. Building on Hyundai Motor Company’s fuel cell system, Hyundai Rotem unveiled a hybrid hydrogen fuel cell tram prototype in 2021. A revised design shown at InnoTrans 2022 later received an iF Design Award in 2023. It was a reminder of the advantage Hyundai Rotem gets from its corporate family: when the parent is placing big bets on hydrogen in autos, the rail affiliate can translate that bet into rolling stock.

In short, rail was having its own inflection point. Defense may have been the shock-driven boom, but rail was starting to look like the patient payoff.

X. The K3 and the Future Battlefield

Even as the K2 drives today’s surge, Hyundai Rotem is already looking past it. The company is developing a successor commonly referred to as the K3—described in official materials as the Next-Generation Main Battle Tank (NG-MBT). The premise is blunt: South Korea’s military assesses that the K2, as capable as it is, won’t fully meet the demands of the next era of mechanized warfare.

You can see that future taking shape in public. At Eurosatory 2024, Hyundai Rotem unveiled its NG-MBT concept—quickly dubbed “K3” by observers—and framed it as a response to the kinds of combat being relearned in Ukraine: drones everywhere, top-attack threats, constant surveillance, and a premium on survivability, signature reduction, and mobility under fire. The company has said the design is intended to surpass existing main battle tanks such as the M1 Abrams and T-14 Armata in key areas, especially stealth and protection, while staying fast and maneuverable in more hostile operating environments.

Then came a more formal signal that this wasn’t just an airshow mockup. On April 17, 2025, Hyundai Rotem registered a new main battle tank design with the Korean Intellectual Property Office (KIPO). The application was filed on August 26, 2024 under number 30-2024-0034192, examined, and approved on March 21, 2025.

The configuration Hyundai Rotem has pointed toward is a major departure from the K2. The standout feature is a fully unmanned turret, paired with an armored crew capsule in the front of the hull designed to house two or three crew members: the driver, commander, and gunner. It’s a layout optimized for a battlefield where being seen is deadly—and where protecting people may mean physically separating them from the most exposed parts of the vehicle.

Firepower is evolving too. Hyundai Rotem has confirmed it successfully tested a new 130 mm main gun for the next-generation tank. Compared with the 120 mm smoothbore guns that dominate today’s fleets, the larger caliber is expected to improve armor-piercing performance, extend range, and increase muzzle energy—an explicit bet that protection levels will keep rising and the tank’s main gun needs headroom to stay relevant.

But the most radical idea is propulsion. Hyundai Rotem is pursuing a hydrogen-powered future for main battle tanks, working with the Agency for Defense Development and the Korea Research Institute for Defense Technology Planning and Advancement. The concept is phased: the K3 would initially field a hybrid system combining diesel and hydrogen elements, and then transition toward hydrogen-only propulsion. The long-term goal—set for 2040—is a fully electric tank powered by hydrogen fuel cells, batteries, and dual electric motors.

The appeal is straightforward: hydrogen-based electric drive promises lower acoustic and infrared signatures and potentially longer endurance—traits that matter in a drone-saturated, sensor-heavy battlefield where detection often precedes destruction. If the K2 was built for speed and fire control in a networked fight, the K3 is being shaped for a world where “don’t be found” can be as important as “win the duel.”

Hyundai Rotem has said a K3 prototype is expected in 2030, followed by testing and evaluation, with entry into service anticipated around 2035.

And just like the K2, this won’t be a solo corporate project. Hyundai Rotem and its government partners are taking a methodical approach, and they’ve left the door open to international participation—especially from Poland. That matters because the Poland partnership already goes beyond buying finished tanks. The K2 agreements include cooperation to build manufacturing facilities in Poland for K2 production and maintenance, and for production tied to K3 next-generation tanks. If Poland becomes a development partner and early export customer, it could provide something defense programs always hunger for: scale, and the lower unit costs that come with it.

XI. Investment Analysis: Bull Case, Bear Case, and the Road Ahead

Hyundai Rotem’s stock chart reads like the market trying to catch up to a company that changed faster than anyone expected. Over the last 52 weeks, the shares have traded between 43,650 and 233,500 won—more than a fivefold spread from low to high. That kind of move isn’t just volatility for its own sake. It’s investors wrestling with a real shift in fundamentals, while also trying to price an uncertain, potentially transformative future.

The financial results show why expectations reset. For the year ended December 31, 2024, Hyundai Rotem reported sales of KRW 4,376,600 million, up from KRW 3,587,400 million the year before. Net income climbed to KRW 406,900 million from KRW 161,000 million.

And the acceleration didn’t stop there. By Q3 2025, revenue growth had reached 48.11% year-over-year—well above the 22% growth rate for full-year 2024. Even more telling, profitability expanded sharply: operating margin rose to 17.15% in the latest quarter, up from 10.43% for the prior full year. In plain terms, Hyundai Rotem wasn’t just selling more. It was converting more of those sales into profit—either through stronger pricing, better mix, better execution, or all three.

The balance sheet also strengthened. Total debt fell to 82.5B KRW in the latest quarter from 351.1B KRW at the end of fiscal 2024. Meanwhile, cash and short-term investments grew to over 1T KRW, leaving the company in a very strong net cash position. That matters, because both rail and defense are capital-intensive businesses where working capital can swing hard depending on contract structure and delivery schedules.

The Bull Case:

The bull case for Hyundai Rotem is essentially a story of multiple flywheels spinning at once.

First, the defense cycle looks less like a spike and more like a reset. European rearmament increasingly resembles a generational change in posture, not a temporary response to Ukraine. Poland’s framework agreement covers up to 1,000 K2 tanks. Romania and Slovakia have expressed interest. Across the continent, governments are revisiting force structure, readiness, and replacement timelines—and Hyundai Rotem has already proven it can deliver on schedules that incumbents often can’t.

Second, rail may finally be entering the payoff phase. Backlog nearly doubled, reaching 14.1 trillion won by the end of 2024 from 7.1 trillion won in 2020. The Morocco contract, by itself, is enormous relative to Hyundai Rotem’s recent annual revenue base. Uzbekistan validated that Korean high-speed rail technology can win abroad and then actually ship. And the EMU-320’s TSI design certification opens the door to Europe—arguably the world’s most demanding market for interoperability and standards compliance.

Third, the K3 program gives Hyundai Rotem a plausible “next product” rather than a reliance on one platform forever. If development stays on track, Hyundai Rotem could field a next-generation tank shaped by the realities being exposed in Ukraine, while many competitors are still modernizing designs rooted in older assumptions.

Fourth, Hyundai Motor Group affiliation provides real strategic leverage. The most obvious example is hydrogen: if Hyundai is pushing fuel cell technology at scale in automotive, Hyundai Rotem can draw on that ecosystem in both rail and, longer-term, armored vehicles. That’s not a guarantee of success, but it is a source of technical depth that many standalone defense primes don’t have.

The Bear Case:

The bear case is about execution, concentration, and the risk that today’s tailwinds don’t last.

Execution risk is real, and Hyundai Rotem has the scars to prove it. The U.S. rail experience—SEPTA and Boston—showed how badly things can go when a manufacturer enters an unfamiliar regulatory environment with a new supply chain and new subcontractors. Scaling production to meet Poland and any follow-on export demand is not just about factory capacity; it’s about quality systems, supplier discipline, and delivering consistently under scrutiny.

Then there’s geopolitical dependency. The defense boom exists because threat perception is high. If Russia’s war ends and European governments decide they’ve over-ordered, contracts can slow, shrink, or get renegotiated. Korean domestic politics also matters. The reported delay in some defense contract negotiations tied to the impeachment of President Yoon in late 2024 is a reminder that even when the product is ready, timing can be political.

Competition is also waking up. European and American defense contractors are ramping capacity. In rail, CRRC remains the global heavyweight. Over time, as more suppliers add output and buyers regain leverage, margins can compress—especially if “fast delivery” stops being scarce.

Porter’s Five Forces Analysis:

Supplier Power: Moderate. Korea has built domestic supply chains for many components, which reduces dependence on imports. But certain critical technologies—like engines and some electronics—still create exposure.

Buyer Power: Mixed. Government buyers have leverage, but speed of delivery and the growing Poland ecosystem can raise switching costs. Rail buyers are more fragmented, which can cut both ways.

Threat of New Entrants: Low in defense due to high barriers in technology, relationships, and scale. More moderate in rail, particularly with Chinese competition.

Threat of Substitutes: Low for tanks—there’s no true substitute for armored capability. More moderate for rail, where alternatives include buses, cars, and air travel depending on the route.

Competitive Rivalry: Intense in both defense and rail, though Hyundai Rotem has carved out a niche around speed, cost, and increasingly credible systems performance.

Hamilton Helmer’s 7 Powers:

Scale Economies: Emerging. Higher volumes—especially from Poland—should reduce unit costs over time.

Network Effects: Limited. These products don’t naturally benefit from network effects.

Counter-Positioning: Present. Hyundai Rotem’s ability to deliver quickly is hard for slower incumbents to match without changing how they run their businesses.

Switching Costs: Meaningful in defense (training, maintenance, spare parts, and sustainment ecosystems). Lower in rail, where procurement cycles can still be competitive and price-sensitive.

Branding: Still forming. The K2 export story builds credibility fast, while earlier rail missteps—especially in the U.S.—remain part of the record.

Cornered Resource: Plausible. Korea’s industrial capacity and integrated manufacturing base are difficult for competitors to replicate quickly, especially in regions that allowed capacity to atrophy.

Process Power: Present. Korea’s manufacturing culture—hardened in automotive and heavy industry—supports repeatability and speed when it’s executed well.

Key Performance Indicators:

For investors watching Hyundai Rotem, two indicators tend to matter most:

-

Defense Order Backlog Growth: Backlog is the forward-looking heartbeat of the defense business. Watch for new country announcements, expansions of existing frameworks, and concrete progress on K3 development.

-

Operating Margin Trajectory: Scaling should create operating leverage. If volumes rise but margins stagnate or fall, it’s often a signal of pricing pressure, cost creep, or execution issues.

Regulatory and Accounting Considerations:

Defense exports come with unique friction. Export licenses can be delayed or denied. Political transitions—either in Korea or in customer countries—can change procurement timelines. And long-term contract revenue recognition depends on percentage-of-completion judgments, which can introduce accounting sensitivity.

Hyundai Rotem’s affiliation with Hyundai Motor Group also creates related-party relationships that investors should track. There is no indication of improper transactions, but transparency and governance matter more as the company grows into a bigger strategic role.

XII. Conclusion: The Korean Model and What It Means

Hyundai Rotem’s journey—from a crisis-era merger to a defense export headline—offers lessons that go way beyond one company.

First: technology transfer works, but only if you treat it like a multi-decade project, not a press release. Korea signed the TGV deal in 1994. The first export of Korean-technology high-speed trains didn’t arrive until 2024. That gap isn’t failure; it’s the cost of doing it for real. Complex industrial capability is built the slow way: absorbing know-how, building suppliers, learning through mistakes, then eventually outbidding your teacher.

Second: crisis doesn’t create winners. It reveals who was prepared. The 1997 Asian financial crisis could have hollowed out Korean heavy industry. Instead, it forced consolidation and focus that made national champions stronger. Ukraine did something similar for defense exports. When Europe suddenly needed tanks and artillery fast, Korea still had warm production lines, working supply chains, and equipment that was credible enough to be trusted.

Third: the public-private model—so often dismissed as clumsy “industrial policy”—can be brutally effective when it’s disciplined. Hyundai Rotem exists because the Korean government pushed a merger the market probably wouldn’t have engineered on its own. And it scaled because the state didn’t stop at restructuring: it backed long-cycle R&D, helped open doors through diplomacy, and supported exports with financing. The coordination wasn’t always elegant, but it created conditions where learning could compound.

Fourth: speed is a competitive advantage, and in heavy industry it compounds. Getting K2s to Poland in roughly six months wasn’t a one-off trick. It was the downstream result of decades of execution culture, automotive-influenced supply chain discipline, and a choice to keep capacity alive while others optimized for a quieter world.

And the story still has real risk in it. The K3 program will determine whether Hyundai Rotem can stay ahead as warfare changes. The rail business has to execute cleanly on Morocco and whatever comes next, because global rolling stock is a memory sport—buyers don’t forget delays and defects. And competition will only get sharper as European and American incumbents retool and ramp.

But Hyundai Rotem has already proven something many would have written off a decade ago: a company born from forced consolidation, in a country with a relatively small home market, can grow into a global competitor in two of the most demanding categories on earth—high-end rail systems and modern armored vehicles.

Whatever happens next, that alone is a remarkable chapter in the broader story of how Korea builds capability—then exports it.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music