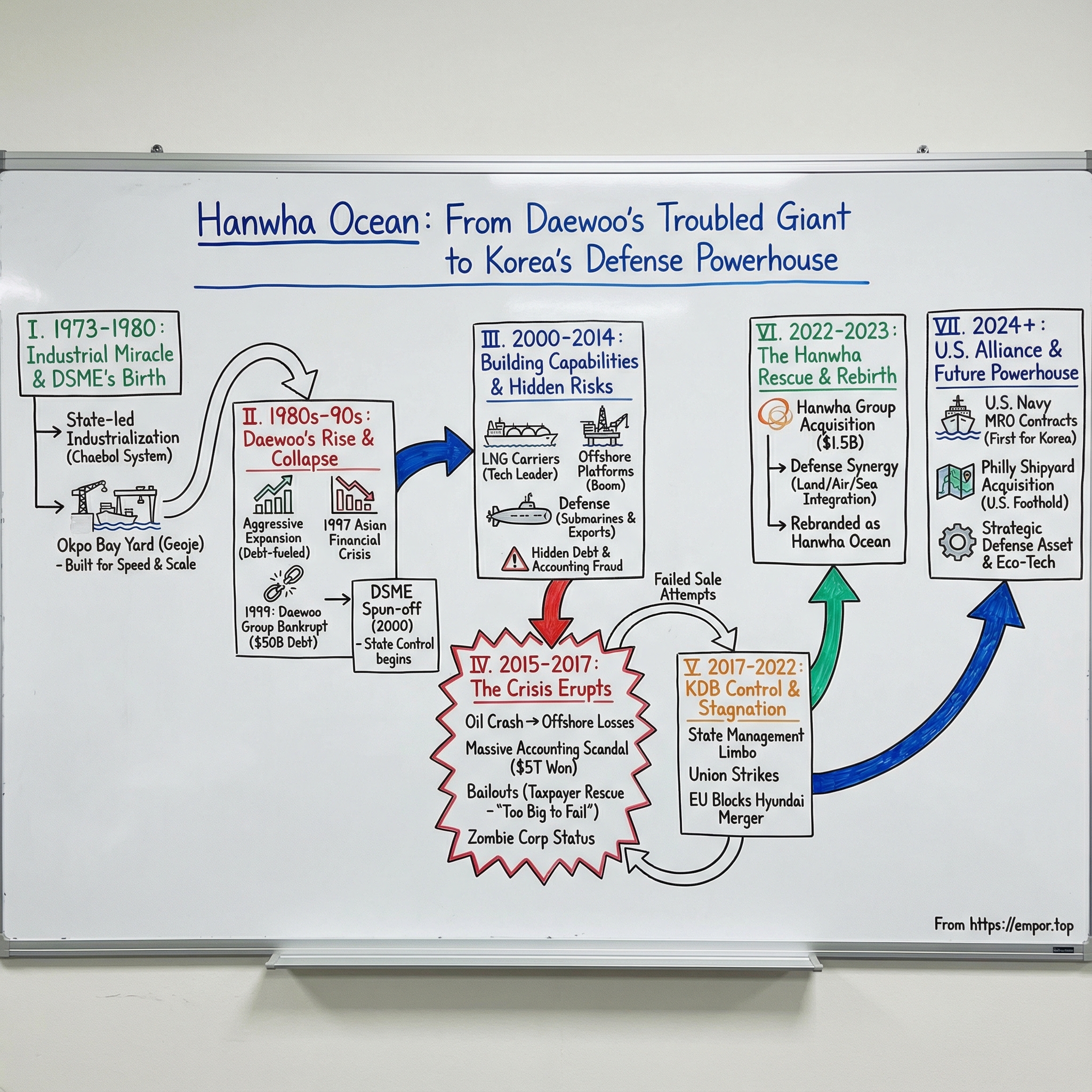

Hanwha Ocean: From Daewoo's Troubled Giant to Korea's Defense Powerhouse

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

On a December morning in 2024, a 40,000-ton U.S. Navy dry cargo and ammunition ship eased into berth at Hanwha Ocean’s Geoje shipyard, on the southeastern edge of the Korean Peninsula. The vessel was USNS Wally Schirra. And its arrival signaled something that would’ve sounded unthinkable not long ago: a South Korean yard performing a U.S. Navy maintenance, repair, and overhaul job.

That’s not just a contract. It’s a tell. For most of the 20th century, American naval power rested on an industrial base that could build and sustain fleets at scale. Now, in a world where shipbuilding capacity has consolidated and atrophied in the West, the U.S. Navy is increasingly looking to allies with deep shipyard capability. Korea is at the top of that list.

The yard doing the work is Hanwha Ocean, formerly Daewoo Shipbuilding & Marine Engineering, one of South Korea’s “Big Three” shipbuilders alongside Hyundai and Samsung. But the road from “Daewoo” to “Hanwha” is anything but a clean success story. This is a company that was born from government industrial policy, nearly collapsed under mismanagement and fraud, survived on repeated taxpayer rescues, and spent years under state control—only to reemerge as a strategic defense asset with a role in U.S.–Korea security cooperation.

So that’s the central question: how did a shipbuilder that racked up enormous losses, endured a massive accounting scandal, and leaned on government support for years turn into the kind of partner the U.S. Navy is willing to trust with its ships?

To answer it, we have to go back to October 1973, when the shipyard at Okpo Bay was founded. Over the decades, Geoje grew into one of the most formidable shipbuilding complexes on Earth—spanning roughly 4.9 million square meters, anchored by the world’s largest 1-million-ton dock and a 900-ton Goliath crane. It’s the kind of physical, hard-won industrial capability that can’t be spun up quickly, and that’s exactly why it matters now.

Along the way, we’ll follow a set of themes that sit right at the intersection of capitalism and national strategy: the chaebol system and its strange blend of speed and fragility; government policy that creates both world-class industry and moral hazard; the rise and collapse of the Daewoo empire; the near-death experiences that forced the state to choose between bailout and disaster; and the defense-industrial renaissance that’s made Korean shipbuilding newly indispensable to the United States.

For investors, this is ultimately a story about what happens when national security trumps market discipline—and how, in certain industries, a company’s strategic importance can matter more than its balance sheet.

II. Korea's Industrial Miracle & The Birth of DSME (1973–1980)

If Hanwha Ocean feels, today, like a piece of national infrastructure as much as a company, that’s because South Korea built its modern economy that way—on purpose.

In the early 1950s, the country was shattered by war. Infrastructure was wrecked, industrial capacity was thin, and incomes were among the lowest in the world. The starting point was so bleak that it’s hard to reconcile with what Korea would become just a few decades later.

Then came the “Miracle on the Han River,” one of the fastest economic transformations in modern history. By the 1970s, South Korea’s leadership wasn’t aiming for incremental growth. It wanted a full industrial leap. Under President Park Chung-hee, the state pushed hard into heavy and chemical industries—steel, machinery, petrochemicals, electronics, and, crucially, shipbuilding.

But the distinctive feature wasn’t just the sectors. It was the mechanism.

Korea didn’t rely on a purely free-market model, and it wasn’t Soviet-style central planning either. Instead, the government partnered with a handful of family-controlled conglomerates—the chaebol—then poured in credit, protection, and policy support in exchange for aggressive production and export goals. Samsung, Hyundai, LG, SK… these weren’t simply private firms competing in an open arena. They were national champions, built and steered to win on the global stage.

Shipbuilding was a textbook case. In the early 1970s, Korea barely had a shipbuilding industry to speak of. And yet, in less than a decade, Korean yards were turning into global contenders.

Into that moment came the yard at Okpo Bay.

DSME’s origins trace to October 1973, when the shipyard was founded at Okpo Bay on Geoje Island, off the southeastern tip of the peninsula. The location wasn’t accidental: a deep natural harbor that could handle enormous hulls, and far enough from Seoul to be less exposed in the event of conflict with North Korea.

And here’s the twist that sets up so much of what comes later: Daewoo didn’t really want this.

As the decade closed, the government pushed Daewoo into shipbuilding—an industry better suited, at least on paper, to groups like Hyundai and Samsung with deeper heavy-engineering roots. Kim Woo-choong, Daewoo’s founder, had built his empire through textiles and trading. Shipbuilding was the opposite of what made him successful: capital-intensive, cyclical, and famously unforgiving when demand turns. He was reluctant. The state insisted.

Okpo itself became a monument to that national ambition. Workers took a stretch of coastline and, in a matter of years, carved out what would become one of the world’s great shipbuilding complexes. The shipyard was completed in 1981—remarkably fast for a project of that scale.

This is the bargain at the heart of the Korean development story, and it runs straight through Hanwha Ocean’s DNA.

On one side: speed. Scale. Capabilities that would’ve taken other countries generations to assemble—massive docks, cranes, skilled labor, a supplier ecosystem—built in a single national sprint.

On the other: entanglement. When the government is effectively assigning industries to companies, backing them with financing, and tying them to national goals, it changes the risk calculus. If things go wrong, it’s not just shareholders on the line. It’s jobs, exports, and strategic capacity. The question of who ultimately bears the downside gets baked in from the beginning.

By the end of the 1970s, the scaffolding was in place: a giant yard, a national industrial strategy, and a chaebol system built to execute it. Korea was on its way to becoming a shipbuilding powerhouse.

And Daewoo was now committed to an industry it never asked to enter—one that would eventually make it world-class, and nearly break it.

III. The Daewoo Era: Rise, Overreach & Collapse (1980–2000)

Kim Woo-choong was the purest expression of Korean entrepreneurial ambition—and the warning label that came with it.

He came of age during the Korean War. At 14, he was already responsible for helping support his family. He sold newspapers, fought his way through Kyunggi High School in Seoul, and graduated from Yonsei University in 1960 with a B.A. in economics.

In 1961, he started work at Hansung Industrial, a company owned by a relative. Six years later, he borrowed $10,000 and founded Daewoo Industrial, a textile trading business. It was a small bet that turned into something enormous: the Daewoo Group—Daewoo meaning “Great Universe”—which, by the 1990s, had become a globe-spanning “chips-to-ships” conglomerate and Korea’s third-largest chaebol.

Kim’s own mythology kept pace with the business. His autobiography, Every Street Is Paved with Gold, reportedly sold a million copies in five months. He was famous for being the most risk-tolerant of the chaebol founders. And for a long time, that risk appetite looked like genius.

Then it started to look like a trap.

Across the 1980s and 1990s, Daewoo expanded aggressively into automobiles, consumer electronics, and financial services. At its peak, it employed more than 320,000 people, had hundreds of overseas subsidiaries, and operated in more than 110 countries. Kim pushed into places other executives avoided—Libya, Poland, Pakistan, Sudan—because he believed scale itself would solve the problem. Grow first. Profits later.

That mindset filtered down into shipbuilding too. DSME chased orders aggressively and pushed into offshore oil and gas platforms when the market was hot. But the bigger Daewoo got, the more fragile it became. The group piled on debt to finance its global expansion, and when its automotive ambitions fell short—especially as the 1997–98 crisis hit developing markets—those strains spread through the entire empire, shipbuilding included.

Then the Asian Financial Crisis arrived in 1997, and it did what crises do: it exposed leverage.

The shock began in Thailand and tore across the region. The won fell sharply. Korean companies that had borrowed heavily in dollars suddenly faced debt burdens that effectively exploded overnight.

Daewoo was among the worst-positioned. By mid-1999, its management said it could no longer meet repayments. The company was facing roughly $500 million a month in short-term debt service, tied to total debt reported at $57 billion—an almost unfathomable number in Korea at the time.

What followed became one of the most infamous corporate collapses in modern history. On November 1, 1999, the Daewoo Group was declared bankrupt, with debts of around $50 billion.

Kim Woo-choong didn’t go down with the ship. He fled to Vietnam. Former Daewoo factory workers put up “Wanted” posters with his photo. The author who promised streets paved with gold had become an international fugitive.

Authorities later charged him with massive accounting fraud, illegal borrowing, and laundering billions of dollars while in exile. Interpol was involved. And in the aftermath, Korea’s surviving conglomerates got the message. As one observer put it, it reinforced the necessity to deleverage and get groups into reasonable financial order. Many refocused on their core businesses.

DSME, meanwhile, was pulled out of the wreckage. In 2000, Daewoo Shipbuilding & Marine Engineering was spun off as an independent company, and it re-listed on the Korean stock market in 2001. But “independent” didn’t mean free. Its biggest asset—a shipyard and set of capabilities the country couldn’t afford to lose—had effectively become a national concern. The Korea Development Bank emerged as the largest shareholder, and DSME entered a strange, state-supported limbo: too strategic to let fail, but no longer built to thrive under normal market discipline.

Kim eventually returned to Korea in 2005. He was arrested, convicted, and in May 2006 was sentenced to 10 years in prison on charges including embezzlement and accounting fraud. He later received a presidential pardon and died in 2019—an emblem of Korea’s industrial rise, and of what happens when ambition runs without brakes.

For DSME, though, Daewoo’s collapse wasn’t the end of the story. It was the start of a long, grinding second act—one where the company would keep building world-class ships, even as the financial and governance problems that were planted in the Daewoo era kept coming due.

IV. Building World-Class Capabilities: LNG, Offshore & Defense (2000–2014)

DSME came out of Daewoo’s collapse battered, but not broken. The balance sheet was a mess and the governance was shaky—but the core of the company was still there: the Okpo yard, a deep bench of skilled trades, and the kind of production know-how you only get by building hard ships the hard way.

So the 2000s became a sprint to turn that industrial base into something the world would pay a premium for. DSME pushed into the most technically demanding corners of shipbuilding—projects where “close enough” doesn’t float.

Over the years that followed, it racked up a string of marquee achievements: delivering an LNG regasification vessel that supplied natural gas to disaster areas after Hurricane Katrina in the U.S. in 2005; building the world’s first floating LNG facility in 2016; delivering the world’s first LNG carrier with a full regasification system in 2018; and delivering 15 icebreaking LNG carriers designed for Arctic operations in 2019.

The throughline here is LNG. This became DSME’s signature product because it’s one of the best moats in shipbuilding. LNG has to be kept at minus 162 degrees Celsius. That means exotic materials, precision fabrication, and systems integration that leaves almost no room for error—at massive scale, on a moving platform, in the open ocean. Plenty of yards can weld steel. Only a handful can reliably deliver LNG carriers that perform, on schedule, and at volume.

And DSME wasn’t just building sophisticated ships—it was winning the biggest customers.

In February 2011, A.P. Moller–Maersk ordered 10 giant container ships from DSME, each capable of carrying 18,000 containers, setting a new industry benchmark. The deal was worth $1.9 billion, with the first delivery slated for 2014. A few months later, in June, Maersk doubled down with an order for 10 more—another $1.9 billion. These ships would become known as the Triple E class, a name that signaled exactly what Maersk was buying: a new generation of scale and efficiency.

But as impressive as the commercial work was, the capability that mattered most to Korea—and eventually to Hanwha—was defense.

DSME’s submarine story is tightly intertwined with South Korea’s own naval ambitions. After building Korea Submarine-I (KSS-I) class submarines in the late 1980s, the company went on to participate in the Korea Submarine-II (KSS-II) program. That experience didn’t just produce boats; it built institutional muscle—design capability, supply chains, quality systems, and a workforce trained for the unforgiving standards of undersea warfare.

It also opened doors overseas. In 2004, DSME completed an Indonesian submarine overhaul project. And in December 2011, it landed what was then the largest single defense contract ever won by a Korean firm: $1.07 billion to build three submarines for Indonesia. The significance wasn’t the headline number. It was what it implied—South Korea, long a buyer of high-end naval technology, was now exporting it, competing in a market historically dominated by European and American primes.

Submarines were the flagship, but the portfolio was broader. DSME built destroyers, frigates, and other surface combatants for the Korean Navy, steadily climbing the learning curve on propulsion, integration, and naval systems. That blend—commercial scale plus defense-grade capability—would become the company’s strategic shield in the years ahead.

Because even as DSME piled up engineering wins, the economics underneath the business were turning. Offshore oil and gas, a major profit engine in the 2000s, was heading toward a brutal downturn. And inside DSME itself, a quieter problem was forming—one that wouldn’t show up in steel and launch ceremonies, but would erupt in the financial statements.

The company was about to enter the part of the story where the ships keep getting better—and the corporate crisis gets much, much worse.

V. Crisis, Scandal & Near-Death (2015–2017)

In 2015, DSME’s outward story of steady, world-class execution finally snapped. Oil prices collapsed, the offshore oil and gas boom went into reverse, and the projects that had looked like a profit engine started turning into sinkholes—cancellations, renegotiations, and customers dragging out payments.

But the real disaster wasn’t the cycle. It was what the cycle revealed.

As auditors and investigators dug into the numbers, they didn’t just find losses. They found a pattern: losses that had been systematically buried to make DSME look healthier than it was. What should have been a painful downturn became a full-blown governance crisis.

South Korea’s Board of Audit and Inspection didn’t just blame DSME. It also faulted the company’s biggest shareholder, the state-run Korea Development Bank. In the BAI’s telling, KDB neglected its responsibility to monitor DSME’s accounting and financial stability—exactly the kind of oversight you’d expect when taxpayers are effectively standing behind the balance sheet.

The scale was stunning. Investigators estimated the value of the accounting fraud at more than 5 trillion won between 2012 and 2014. DSME wasn’t simply smoothing earnings. It was accused of cooking the books to make huge losses look smaller, and in some cases even presenting the company as profitable.

The BAI said this manipulation allowed DSME to report net profits of 323.7 billion won across 2013 and 2014. In reality, it had accumulated a net loss of 839.3 billion won over the same period.

And that deception didn’t just mislead investors and creditors. It flowed into paychecks. The BAI said delayed action meant incentives were paid out unfairly—6.5 billion won for executives and 198.4 billion won for employees—money tied to results that, on paper, never existed.

Investigators focused on leadership at the top. Two former CEOs—Ko Jae-ho, who led DSME from 2012 to 2014, and his predecessor Nam Sang-tae—were identified as central figures connected to the alleged accounting fraud, which was estimated at 5.4 trillion won.

Prosecutors also called in Kim Yul-jung, DSME’s CFO since March 2015, over allegations that $110 million in operating losses were deliberately hidden. Investigators suspected the motivation was straightforward: keep credit lines open and avoid administrative actions tied to DSME’s listing on the Korea Stock Exchange.

The scandal widened to the gatekeepers, too. Deloitte Anjin, the auditing firm, came under heavy scrutiny. The Seoul Central District Court issued an arrest warrant for a former Deloitte Anjin executive surnamed Bae—the first employee of the firm arrested in connection with the DSME case.

One grim counterfactual hung over all of it. If roughly 2 trillion won in losses had been recognized when they were incurred, DSME would have shown deficits of more than 700 billion won in each of those years. Observers argued restructuring would have started earlier—and could have reduced the eventual burden of the roughly 7 trillion won in taxpayer money that would be funneled into keeping the company afloat.

Once the masking tape was ripped off, the underlying financial condition was impossible to ignore. DSME posted a loss of 5.13 trillion won for the full year of 2015.

That forced the government into a choice that wasn’t really a choice. In October 2015, the state stepped in with a 4.2 trillion won bailout. But it didn’t stabilize the patient. DSME continued to rack up operating deficits, and the liquidity pressure didn’t ease.

Just over a year later, it was back at the brink. State banks prepared another rescue—about $2.6 billion—to keep DSME from missing debt repayments after offshore losses piled up.

And the nightmare scenario was enormous. In a bankruptcy, around 50,000 jobs were expected to be wiped out, with roughly 1,300 subcontractors at risk of going under. Creditor banks would be on the hook for massive refund guarantees on prepaid construction fees, and might need to set aside bad-loan provisions of up to 14 trillion won. Estimates warned the wider Korean economy could take a 48.4 trillion won hit if DSME collapsed.

The Bank of Korea called the bailout “inevitable” given the consequences of letting the shipbuilder fail.

Outside Korea, though, the rescues looked like something else: state support distorting a global industry. Japan and the European Union filed a complaint with the OECD, arguing that Korea’s state-run banks were propping up DSME in ways that violated World Trade Organization rules.

Then, as if the financial scandal weren’t enough, the company’s strategic vulnerability showed up in a different form. In 2017, it was revealed that North Korea may have hacked DSME in April 2016 and stolen submarine blueprints. For a shipbuilder so central to Korea’s naval ambitions, the implications were chilling: the crown jewels of its defense work potentially compromised by its most dangerous adversary.

By this point, DSME had taken on a new identity: the shipbuilding version of a zombie corporation. It was alive because the state kept it alive, unable to stand on its own, yet too economically and strategically important to let die.

The only question was how long Korea could keep feeding it—and what kind of owner would ever be willing to take it on.

VI. Zombie Decade: KDB Control & Failed Sale Attempts (2017–2022)

For years, DSME slogged through financial trouble as global demand for new ships cooled—especially after the offshore oil and gas market turned in 2015. Under the Korea Development Bank’s control, the company slipped into a prolonged strategic limbo: too important to fail, too damaged to thrive.

This was the uncomfortable reality. DSME remained one of Korea’s biggest shipbuilders, but it kept cycling through losses and management crises. High labor costs, cost overruns, and delivery delays squeezed margins and strained cash. Labor relations didn’t help. The union was powerful and confrontational, and strikes disrupted production schedules—exactly the kind of volatility that spooks shipowners placing billion-dollar orders years in advance.

The government’s answer was supposed to be privatization. In practice, it became a loop of failed attempts.

Hanwha had already tried once, proposing a deal back in 2008. Later, KDB pivoted to what looked like the cleanest industrial solution: merge DSME into Hyundai. But that plan collapsed too—this time not because Korea wouldn’t allow it, but because Europe wouldn’t.

The Hyundai merger attempt is worth pausing on, because it reveals how concentrated and geopolitical the shipbuilding market really is. The European Commission rejected the merger between DSME and Hyundai Heavy Industries Holdings, arguing it would create a dominant player and reduce competition in the global market for LNG carriers. The decision followed an in-depth investigation, and the Commission’s logic was straightforward: DSME and Hyundai were already two of the three biggest builders in the LNG segment. Combine them, and you don’t just get a stronger Korean champion—you get pricing power.

European customers mattered here. Over the prior five years, European shipowners accounted for close to half of all LNG carrier orders. The Commission concluded that the merged company would hold at least a 60% share of the global LNG carrier market, which would likely mean less competition and higher prices.

KDB chairman Lee Dong-gull pushed back, saying Europe’s rejection reflected European self-interest—Europe was home to some of the world’s largest shipowners, and it didn’t want to be dependent on a single Korean super-yard. But whatever the motive, the effect was clear: the Korean government’s restructuring plan was back to square one, and its goal—full privatization to recoup taxpayer money—looked even harder.

And the business kept deteriorating. Losses continued even after cost-cutting. In 2017, state-backed lenders assembled another major support package, including a 2.9 trillion won rescue tied to management changes and asset sales. DSME survived—but survival was the problem. Each bailout made it harder to find a buyer, because the company’s story became inseparable from the state.

Under KDB, DSME was trapped in a no-win competitive dynamic. It had to win new orders to prove it deserved the taxpayer support keeping it alive. But if it priced too aggressively, rivals could claim it was dumping ships with the help of government subsidies. Every contract became a political argument, not just a commercial negotiation—and foreign competitors were happy to point to Korean support whenever they lost a bid.

By 2022, DSME had spent more than two decades under effective state control, consuming enormous public support in the process. Korea’s shipbuilding industry still needed restructuring. The obvious buyer inside the “Big Three” had been blocked. And if DSME was ever going to escape its zombie existence, it would have to be with a new kind of owner—one powerful enough to absorb the mess, and motivated enough to turn a strategic liability into a strategic weapon.

VII. The Hanwha Rescue: A Defense Conglomerate's Bold Bet (2022–2023)

In September 2022, a suitor finally showed up—one that wasn’t trying to turn DSME into “just another shipbuilder,” but into something more strategic.

Hanwha Group signed a conditional deal with DSME and its largest shareholder, the Korea Development Bank, to buy a controlling 49.3% stake for 2 trillion won (about $1.4 billion). On paper, it looked like a corporate rescue. In reality, it was a reshuffling of Korea’s defense-industrial chessboard. The acquisition would put one of the country’s most capable naval shipyards under a conglomerate that already made weapons, sensors, and military systems—and it would also align DSME’s shipbuilding heft with Hanwha’s push into solar and other energy businesses as the industry moved toward greener ships.

Hanwha wasn’t the obvious white knight. It wasn’t a shipbuilding group. It was a chaebol that started life as an explosives company.

Hanwha traces back to 1952, when Kim Chong-hee founded Korea Explosives Co. Before that, Kim worked as a gunpowder engineer at the Chosun Explosives Factory, a Japanese company. He later won the bid for the business and its Incheon factory and launched the firm there. From those roots—literal gunpowder—Hanwha grew into a sprawling conglomerate with businesses spanning energy and materials, aerospace and mechatronics, plus finance, retail, and lifestyle services.

So why take on DSME, a shipbuilding giant that had spent years as a state-managed problem?

Because the fit wasn’t about commercial ship cycles. It was about completing a defense portfolio.

Hanwha already produced self-propelled howitzers for the army and supplied radar systems and aircraft engines for the air force. What it lacked was a true naval platform builder. DSME filled that gap instantly, with proven capability in warships and submarines. As Hanwha put it at the time, by combining networks across the Middle East, Europe, and Asia, it expected to lift exports not only for Hanwha Aerospace and Hanwha Systems, but also for DSME’s flagship 3,000-ton-class submarines and warships.

And the synergy story wasn’t just “sell more defense hardware.” Hanwha Systems emphasized that integrating its maritime systems technologies with DSME’s shipbuilding capacity could enable development of self-navigating commercial ships. The group also highlighted upside in eco-friendly LNG, where DSME already had deep technical credibility.

The ambition behind all of this was straightforward: Hanwha wanted to become the Korean version of Lockheed Martin—an integrated defense champion across land, sea, air, and space. DSME would be the piece that made “sea” real.

The ownership structure reflected that commitment. A total of six Hanwha subsidiaries took stakes, including Hanwha Aerospace investing 1 trillion won, Hanwha Systems 500 billion won, and Hanwha Impact 400 billion won. KDB, which had carried DSME for years, argued the deal would materially improve the shipbuilder’s financial footing.

Getting it done, though, meant running a global regulatory gauntlet. The acquisition required approvals across multiple jurisdictions, including the European Union, Japan, China, Türkiye, Vietnam, Singapore, and the United Kingdom.

The irony was hard to miss: the European Commission that had blocked the DSME–Hyundai tie-up on competition grounds approved the Hanwha deal. The Commission concluded the acquisition raised no competition concerns because Hanwha didn’t already have shipbuilding operations—so the merger didn’t create the same kind of market-concentration risk in segments like LNG carriers.

The last and hardest gate was at home. Korea’s Fair Trade Commission gave only conditional approval, arguing that the transaction was a vertical merger between companies with significant positions in both vessels and key parts, and that it could impede competition. The FTC’s conditions included a ban on Hanwha selling naval ship systems and components to DSME at discriminatory low prices, along with other rules intended to prevent unfair exclusion of rival shipbuilders. In other words: Korea would allow a new “Big Three” rivalry—Hyundai, Samsung, and now Hanwha—but it wanted guardrails.

In 2023, Hanwha finalized the acquisition and re-launched DSME under a new name: Hanwha Ocean. At an extraordinary shareholders’ meeting, the company was formally established as Hanwha Ocean Co., Ltd. The meeting also appointed Hyek Woong Kwon as CEO and added nine new board directors. Five Hanwha affiliates became major shareholders, collectively holding the 49.3% stake valued around $1.5 billion.

Inside the group, the messaging shifted from “turnaround” to “integration.” Hanwha described plans for defense-industry synergy across its portfolio, pointing to efforts such as the ISM (Integrated Sensor Mast) on Chungnam-class frigates as an example of the kind of systems-and-platform integration it wanted to scale.

Stepping back, the deal marked a fundamental change in how Korea treated its troubled shipbuilder. DSME wasn’t being privatized simply because taxpayers were tired of funding a zombie. It was being repositioned as something closer to a strategic arsenal—because in a world of rising geopolitical tension, submarine and warship capability doesn’t get valued like a normal business line. It gets valued like national power.

VIII. Transformation & U.S. Expansion (2024–Present)

Hanwha’s timing turned out to be immaculate. Just as the group finished taking control and rebranding DSME as Hanwha Ocean, the United States was waking up to a hard truth: shipbuilding isn’t just an industrial sector. It’s a constraint on national power.

Strategists started pointing to the topline comparison first. CSIS noted that China’s PLA Navy fielded 234 warships versus the U.S. Navy’s 219. The U.S. still held important advantages—more guided-missile cruisers and destroyers, and far more carrier tonnage thanks to its 11 aircraft carriers versus China’s three. But the more alarming story wasn’t the fleet today. It was the ability to build, repair, and sustain the fleet tomorrow.

On that front, the gap looked existential. By some estimates, China’s shipyards had capacity measured in the tens of millions of tons, versus well under 100,000 tons in the United States—orders of magnitude apart. The broader base had withered too: the number of U.S. shipyards had fallen to 21 from 414. And in a recent year, American yards won contracts for only two vessels out of 1,910 ship orders worldwide.

A 2023 congressional report put the long arc in stark terms. In the 1970s, U.S. shipyards built around 5 percent of the world’s tonnage—up to 25 new ships a year. By the 1980s, that dropped to roughly the current rate of about five ships per year.

The implication was obvious, and uncomfortable: if America wanted to rebuild capacity quickly, it would need allies with real industrial depth. South Korea—home to the world’s second-largest shipbuilding industry after China—was the natural partner. And now Hanwha Ocean had both the capability and the incentive to step into that role.

The first proof point arrived with maintenance, not new construction. Hanwha Ocean announced it had won a contract to overhaul a 40,000-ton U.S. Navy dry cargo and ammunition ship, becoming the first South Korean shipyard to secure a U.S. Navy maintenance, repair, and overhaul contract. The job required a Master Ship Repair Agreement, a certification gate that effectively decides who the Navy trusts with its vessels.

Hanwha Ocean applied for the MSRA in January 2024 and cleared the process in seven months—far faster than the usual timeline of a year or more. About a month after receiving the MSRA, the company secured the overhaul work.

The ship was USNS Wally Schirra, and the project ran at Hanwha Ocean’s Geoje Shipyard for roughly six months. It was comprehensive: hull work, engine repairs, and the kind of deep maintenance that tests not just equipment, but processes—planning, quality control, supply chain execution, and on-time delivery. In July, Hanwha Ocean had the MSRA. By the end of the year, it had a completed U.S. Navy job on the board.

And it didn’t stop there. In November, Hanwha Ocean won an additional contract for scheduled maintenance of USNS Yukon, a replenishment oiler.

But MRO was only one front. Hanwha also went after something even more strategic: a U.S. industrial foothold.

In June 2024, Hanwha Group and Hanwha Ocean agreed to purchase Philly Shipyard for $100 million, pending regulatory approvals. By December 2024, the acquisition was completed. For Hanwha, Philly wasn’t just an American logo—it was a real asset. Founded in 1997, the yard had delivered around half of all large ocean-going U.S. Jones Act commercial ships since 2000.

After the deal closed, Philly Shipyard began operating as Hanwha Philly Shipyard, with ambitions to scale output dramatically—from about one vessel per year to 10 to 20 annually within the next decade.

The politics of the moment accelerated the narrative. President Donald Trump said warships would be built at Hanwha’s shipyard in Philadelphia, framing it as part of a broader push to revive American shipbuilding. In that context, Hanwha pledged to invest $5 billion in the shipyard, positioned inside a larger South Korean shipbuilding investment commitment totaling $150 billion that was approved by the United States. Trump also said the U.S. Navy would work with Hanwha Group on a new class of frigates—language that signaled something bigger than a one-off contract, and tied Hanwha Philly Shipyard to his envisioned “Golden Fleet.”

While the geopolitics grabbed headlines, Hanwha Ocean’s turnaround started showing up in the numbers too. The company recorded operating income of 237.9 billion won for the year, swinging from a loss of 196.5 billion won the prior year. Annual sales rose 45.5 percent to 10.77 trillion won. In another reporting period, it posted sales of 4.8197 trillion won (about $3.57 billion), operating profit of 43.3 billion won, and net profit of 23.6 billion won—an improvement year on year, with sales up roughly 47.8 percent.

And on the shipbuilding side, Hanwha Ocean said it had the highest order level in South Korea that year, booking orders for 39 ships valued at nearly $7.9 billion.

For a company that had spent two decades as a corporate zombie—kept alive by taxpayers, trapped under state control, and defined by scandal and rescues—this was the pivot. Hanwha Ocean had finally found a role that justified its existence at a national-strategy level: connecting American demand for naval capacity with Korean supply of industrial reality.

IX. Strategic Analysis: Porter's 5 Forces & Hamilton's 7 Powers

If you zoom out, Hanwha Ocean sits at the intersection of two very different markets: brutally competitive commercial shipbuilding, and strategically protected defense shipbuilding. To understand how durable this turnaround can be, you have to separate what’s structural—forces that shape everyone in the industry—from what’s specific—advantages Hanwha Ocean has earned, bought, or inherited.

Porter's Five Forces Analysis:

Threat of New Entrants: LOW

Getting into high-end shipbuilding is less like starting a factory and more like building a city. Geoje alone covers roughly 4.9 million square meters and includes the world’s largest 1-million-ton dock and a 900-ton Goliath crane. That kind of infrastructure takes decades to plan, finance, and build.

And even that’s just the visible part. The real barrier is the invisible one: accumulated know-how. Building LNG carriers and submarines isn’t a matter of following a blueprint. It’s thousands of process decisions—welding techniques, tolerances, sequencing, quality control, vendor management—that live in the muscle memory of the workforce and the operating system of the yard. A new entrant can buy steel and cranes. It can’t buy 30 years of hard-won learning curve.

Defense makes the wall higher still. National security clearances, technology transfer agreements, and trust-based relationships with defense ministries aren’t things you can shortcut.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers: MODERATE

Shipbuilders rely on a relatively concentrated set of suppliers for engines, navigation systems, and specialized steel. That gives suppliers real leverage.

Hanwha’s edge here is group structure. Vertical integration through Hanwha Aerospace and Hanwha Systems—and the acquisition of HSD Engine—reduces some dependency on external vendors and gives Hanwha Ocean more control over schedule, cost, and systems integration. Korea’s shipbuilding cluster helps too: a dense, co-located supplier ecosystem built around the major yards.

Bargaining Power of Buyers: MODERATE-HIGH

The buyers are sophisticated and they know exactly what they’re doing. On the commercial side, shipowners can shop bids across Korea, China, and Japan, and price sensitivity is ruthless—especially for more “commodity” ship types.

Defense is different. Navies don’t switch suppliers lightly. Once you’ve adopted a platform, you’re committing to decades of maintenance, upgrades, and follow-on procurement. That shifts leverage back toward the builder, particularly in submarines and complex surface combatants.

Threat of Substitutes: LOW

There’s no real substitute for moving massive volumes of goods across oceans. Air freight doesn’t compete on cost for bulk cargo, and global trade still runs on ships. LNG, oil, and containers will keep moving by sea.

In defense, the substitute for naval vessels is… not having naval vessels. In today’s environment, that isn’t an option many countries are willing to entertain.

Industry Rivalry: HIGH

This is where shipbuilding earns its reputation as a tough business. In Korea, the competition among Hanwha Ocean, Hyundai, and Samsung is intense. Globally, Chinese yards continue to gain share with lower costs, keeping pressure on pricing. And because shipbuilding is cyclical, downturns can turn even strong operators into distressed ones. The industry has a habit of punishing optimism.

Hamilton's 7 Powers Analysis:

Scale Economies: STRONG

Shipbuilding is a fixed-cost monster. The yard, the docks, the cranes, the specialized workforce—none of it is cheap, and all of it needs volume to pay for itself. Geoje’s scale enables efficiencies that smaller yards simply can’t match. And the learning curve is real: as teams repeat complex builds, cost and time come down.

Network Effects: WEAK

There aren’t classic network effects here. Shipbuilding doesn’t become more valuable because more people use it.

But there is a softer, indirect benefit: clustering. When suppliers, subcontractors, and talent concentrate around a yard, coordination gets easier and execution gets faster. Geoje and the broader Korean shipbuilding region benefit from that.

Counter-Positioning: EMERGING

Hanwha’s big strategic bet is that integrated defense-plus-shipbuilding beats “shipbuilding alone.” By pairing Hanwha Systems’ sensors and combat systems with Hanwha Ocean’s platform-building capability, the group can offer more complete naval solutions than a pure-play yard.

This advantage is still forming—it needs time, successful programs, and export wins to become a true moat. But if it clicks, it’s the kind of positioning that’s hard for rivals to copy quickly, because it requires capabilities across multiple domains.

Switching Costs: MODERATE-HIGH (Defense) / LOW (Commercial)

Defense switching costs are high for the reasons that matter most: technology transfer, security approvals, training pipelines, interoperability, and long-term sustainment. A submarine program, in particular, isn’t a purchase; it’s a relationship.

Commercial switching costs are lower. Shipowners can move orders if price or delivery timing is better elsewhere, though reputation and track record still carry weight—especially for technically demanding ships.

Branding: MODERATE

DSME built a reputation for quality and delivery performance, and that reputation still matters. Major customers don’t place repeat orders because of a logo; they do it because the last ship worked, arrived on time, and didn’t become a warranty nightmare.

That said, in large parts of commercial shipbuilding, price still speaks loudest. Brand helps most when the ship is complex enough that failure is catastrophic.

Cornered Resource: STRONG (in submarines)

Hanwha Ocean’s most defensible position is in submarines. It dominates South Korea’s submarine market and has amassed a rare combination of design capability, production experience, and institutional knowledge. In 2021, it became the first company in South Korea to fully design, build, and deliver a submarine—an achievement that’s less about a single milestone and more about owning the underlying capability set.

That expertise lives in people, processes, and supplier relationships. It’s not easily transferable—and that’s exactly what makes it valuable.

Process Power: STRONG

This is the quiet superpower of elite shipbuilders: repeatable execution. Hanwha Ocean’s long track record in complex vessel construction—especially LNG carriers—creates a process advantage competitors can’t replicate quickly. It isn’t just “technology,” it’s the operating system: planning, fabrication, quality assurance, and systems integration at scale.

Reaching the milestone of delivering 200 LNG carriers in early 2025 is a signal of that kind of industrial consistency.

Key Performance Indicators to Monitor:

For investors watching whether this is a real transformation or just a cyclical upswing, two indicators matter most:

-

Order Backlog Value and Mix: Not just how large the backlog is, but what it’s made of—high-value LNG carriers and defense work versus lower-margin, price-war vessels. Mix tells you more than volume.

-

Operating Margin Trajectory: After years in the red, sustained positive margins are the proof that the turnaround is real. Continued improvement toward best-in-class shipbuilder profitability would be a powerful confirmation that Hanwha’s operating discipline is sticking.

Risk Factors:

The risks are as real as the upside. Defense work depends on government budgets and politics. Labor relations remain a potential flashpoint; DSME’s union has historically been willing to strike, and shipbuilding schedules don’t forgive disruptions. Commercial shipbuilding will always be cyclical, and down-cycles can be brutal.

And there’s a governance scar that shouldn’t be forgotten. Shipbuilding’s percentage-of-completion accounting can hide problems until they’re too big to hide—DSME proved that the hard way. Hanwha’s ownership and governance reset helps, but investors should still watch for warning signs in reporting discipline.

The Hanwha Ocean story, in the end, is about how strategic capability can outweigh financial performance—sometimes for decades.

A purely market-driven system would likely have liquidated DSME long ago. Instead, Korea kept it alive through scandal, losses, and repeated rescues, because the country understood something markets struggle to price: submarine yards and high-end shipbuilding capacity aren’t just businesses. They’re national assets.

Hanwha’s acquisition formalized that reality. The value wasn’t the balance sheet. It was the yard, the workforce, the learning curve, and the defense credibility. By pairing those with Hanwha’s electronics, sensors, and broader defense footprint, Korea effectively created a vertically integrated naval industrial player—with growing reach not just in Asia, but now in the United States too.

For investors, the question isn’t whether Hanwha Ocean has a tailwind. It does. The question is whether it can execute through the hard parts: improving efficiency, managing labor, and delivering complex builds on time and on budget—over and over again.

History argues for caution. But the setup is unlike anything the company has ever had. With demand rising for allied shipbuilding capacity and American yards stretched thin, Hanwha Ocean finds itself in a rare position: not just recovering, but newly indispensable.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music