SK Inc.: The Quiet Giant Behind Korea's Second Chaebol

I. Introduction: The Holding Company Puzzle

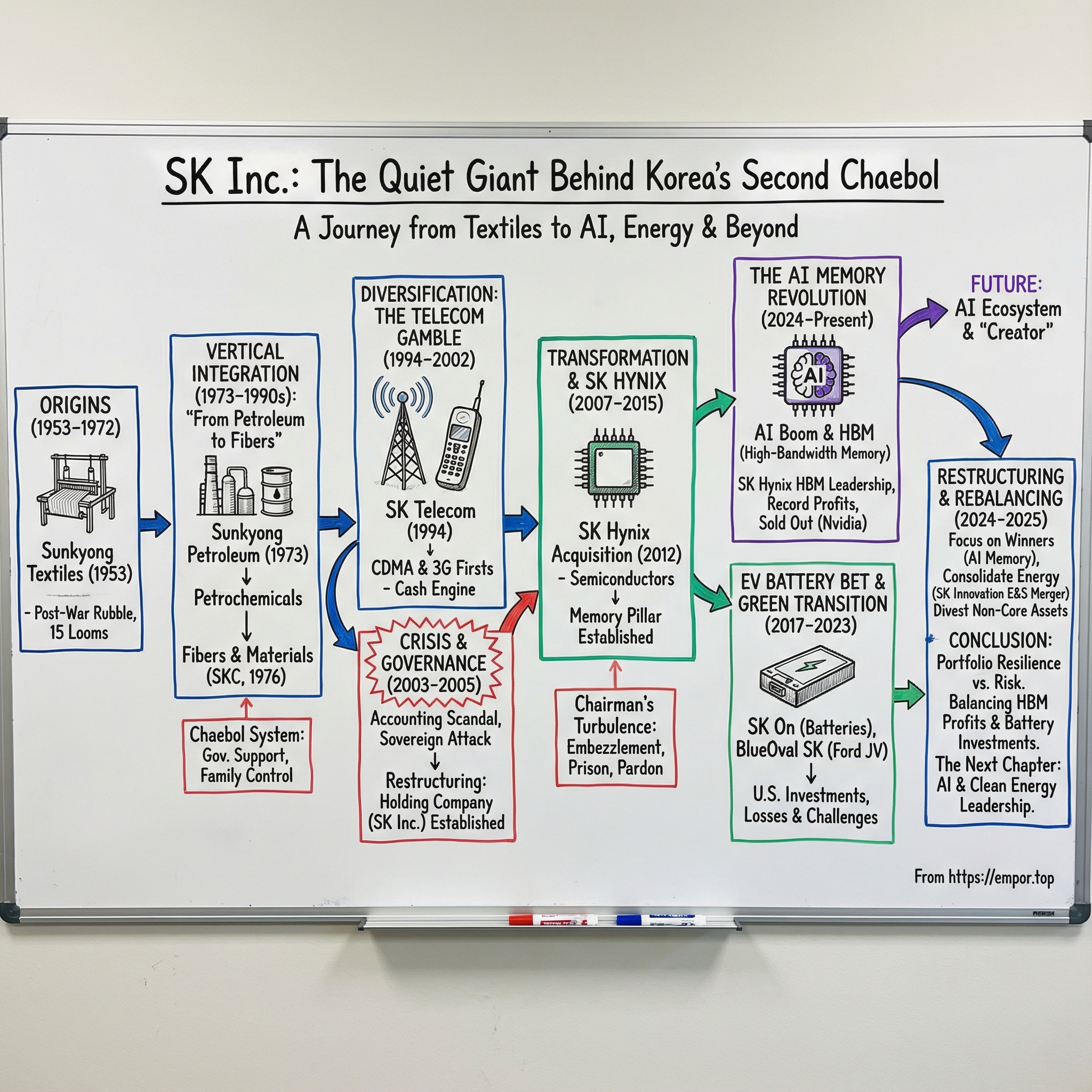

Picture a corporate empire that runs end-to-end across modern Korea: petrochemical refineries in Ulsan feeding the materials economy, semiconductor fabs in Icheon making the memory inside your devices, cell towers blanketing every city, and—half a world away—battery factories rising in Tennessee and Kentucky. Now here’s the twist: at the center of all that sits a relatively unassuming company name, SK Inc., a holding company most global investors barely register, yet one that quietly controls one of Asia’s most important portfolios.

SK Group is a South Korean multinational manufacturing and services conglomerate headquartered in Seoul. It’s a chaebol—a family-controlled conglomerate—and by revenue it ranks second in the country, behind only Samsung. Through its subsidiaries, SK spans chemicals and petrochemicals, semiconductors and flash memory, IT services, and telecommunications on a massive scale.

SK Inc. is the holding company at the top of that structure, headquartered in Seoul. It’s organized into an Investment Division and a Business Division. The Investment side functions as the group’s control tower, with stakes across petroleum, telecommunications, wholesale and retail, chemicals, semiconductors, biotechnology, and more. Under that umbrella sit many of the names that actually do the operating: SK Innovation, SK Telecom, SKC, SK Networks, SK Materials, and SK Biopharmaceutical.

To understand why this matters, you have to understand Korea. The country’s economy isn’t just shaped by big companies—it’s shaped by a small number of giant business families. In 2023, the top four chaebols—Samsung, SK, Hyundai, and LG—generated revenues equivalent to 40.8% of South Korea’s GDP. Expand that to the top thirty chaebols and you’re looking at 76.9% of GDP. This isn’t “a large corporation.” This is national infrastructure, economic gravity, and political influence rolled into one.

So how did a humble textile company—starting with just fifteen looms—become the second-largest conglomerate in Korea, with a hand in everything from your smartphone’s memory chips to the country’s largest telecom network?

The answer is a seven-decade arc defined by a few recurring moves: an almost obsessive commitment to vertical integration, the willingness to make big bets in new industries, and the uniquely Korean push-and-pull between government power, capital markets, and family control. And now, in the AI era, it raises the question that hangs over the entire modern conglomerate model: can a group built on petroleum, heavy industry, and telecom reinvent itself fast enough for what comes next?

II. The Chaebol System: Context for Understanding SK

To understand SK Inc., you first have to understand the peculiar machine that produced it: the chaebol system. These aren’t just “conglomerates.” In modern Korea, they’ve functioned like an economic operating system—part industrial engine, part national strategy, part family dynasty.

For much of the mid-20th century, South Korea was still a small, largely agricultural economy. That changed dramatically after Park Chung Hee seized power in 1961 and pushed an export-led industrialization agenda. The government’s First Five Year Economic Plan didn’t simply encourage growth; it directed it. Industrial policy pointed toward new investment, and the biggest, most promising companies were backed with credit. Chaebols were effectively guaranteed access to loans through the banking system, and in return they were expected to deliver results—new industries, new markets, and, above all, exports. That partnership helped turn South Korea into one of the Four Asian Tigers.

Park’s model was often described as “guided capitalism.” The state chose which companies would take on major projects, and it funneled financing—often sourced from foreign borrowing—toward them. Access to foreign technology mattered too, especially through the 1980s. And when these firms borrowed from abroad, the government frequently guaranteed repayment if they couldn’t meet their obligations. Domestic banks followed with additional funding. In other words: performance was demanded, but the downside risk was softened. That combination is rocket fuel.

The results were staggering. South Korea’s economy expanded at a pace that rewired the country in a single generation. GDP grew from a tiny base in the early 1960s to hundreds of billions by the late 1980s, eventually crossing the trillion-dollar mark in the early 2000s. Income per person rose from roughly a hundred dollars a year in the early 1960s to thousands by the end of the 1980s, and reached the $20,000 milestone in 2006. That leap—from impoverished agrarian nation to industrial powerhouse in about three decades—became known as the Miracle on the Han River.

But chaebols aren’t just Korea’s version of Japan’s keiretsu, even though they’re often compared. A chaebol is typically run and controlled by a founding family, and it usually consists of many affiliated companies spanning unrelated industries, all held together through ownership links and centralized influence. Keiretsu, by contrast, evolved from Japan’s pre-war zaibatsu into networks more commonly run by professional managers, historically with affiliated banks at the center. Korean chaebols have tended to rely more on government financing than on an internal banking hub—and they’ve maintained far tighter family control.

That structure creates a very specific trade-off. Family control can mean speed and long-term ambition—big bets that don’t have to be renegotiated every quarter. It can also mean governance problems: opaque control structures, succession drama, and recurring scandals that seem to touch every major chaebol at some point.

As of 2023, South Korea had 82 chaebols—conglomerates typically run by a single family, with total assets exceeding 5 trillion won. Their influence is enormous: not just in markets, but in policy, regulation, and national industrial priorities. Support can come in many forms—subsidies, loans, and tax incentives—but so can scrutiny, especially when public opinion turns against concentrated power.

This is the world SK Inc. lives in. The chaebol system created the conditions for SK’s rise and still shapes what SK can do next. It comes with a kind of implicit state support—and an equally real expectation that the group will behave like national infrastructure. For better and for worse, SK’s story is inseparable from that bargain.

III. Origins: From War Rubble to Textile Empire (1953–1972)

SK’s story starts where so many Korean success stories start: in the wreckage left behind by war.

In 1953, as the fighting on the peninsula finally stopped, an entrepreneur named Chey Jong-gun looked out at a country with shattered infrastructure, displaced families, and a desperate need to rebuild daily life. His insight was simple, almost unglamorous—and exactly right: before you can industrialize, you have to clothe people.

That year, Chey acquired a textile business called Sunkyong Textiles from the South Korean government. The company itself traced back to the Japanese colonial era, founded as a joint venture between two Japanese firms—Senman Chutan and Kyoto-based Kyoto Orimono Company—and then left behind as “abandoned Japanese property” after liberation and war. The plant in Suwon had been heavily damaged, the kind of place most people would write off as rubble. Chey treated it like a starting line.

He bought the facility, rebuilt what could be rebuilt, and restarted operations in October 1953 with just fifteen weaving machines. That’s all it was: a small factory, a handful of looms, and a huge amount of uncertainty in a battered economy.

But demand did what Chey expected it to do. As Korea stabilized through the 1950s, Sunkyong grew by supplying the domestic market—basic goods for a population trying to stand back up.

Then came the first big signal that this wasn’t going to stay a local textile story. In 1960, Sunkyong became the first Korean company to export fabrics overseas. In a world where “Made in Korea” meant almost nothing, this was a line in the sand: Sunkyong wasn’t just rebuilding. It was competing.

And even before SK became famous for giant, cross-industry bets, you can see the instinct forming here—the desire to move up the value chain instead of staying in one lane. In 1958, the company produced Korea’s first polyester fiber on its own grounds, stepping beyond simple weaving into synthetic materials. In July 1969, it pushed further by establishing Sunkyong Fibers Ltd. and moving into original yarn production.

By the end of the 1960s, Sunkyong had become something more than a postwar textile maker. It was a company learning, early, that the fastest way to grow wasn’t just to sell more—it was to own more of what you needed to make the product in the first place.

And then the next era arrived the way these stories often do: with tragedy, and a succession that changed everything.

IV. The Vertical Integration Masterplan: From Petroleum to Fibers (1973–1990s)

When founder Chey Jong-gun died in 1973, the chair passed to his brother, Chey Jong-hyon—and with it, the company’s entire ambition shifted. Jong-gun had built a fast-growing textile maker. Jong-hyon wanted something bigger: an industrial system that fed itself.

His core idea was deceptively simple, and it became SK’s signature. Don’t just make the product. Own the inputs. Own the bottlenecks. Control the chain.

Textiles had already pushed Sunkyong into synthetics. But synthetic fibers meant petrochemical feedstocks, and petrochemicals meant refining. So Chey followed the logic all the way upstream. In 1973, he founded Sunkyong Petroleum and acquired a refinery with a capacity of 65,000 barrels per day.

By 1975, this wasn’t just a set of deals—it was a doctrine, formally launched under the title “From Petroleum to Fibers.” It was a slogan, sure. But it was also a blueprint: crude oil at one end, finished textile products at the other, with Sunkyong owning the value creation in between.

The plan rolled out steadily through the late 1970s and 1980s. In 1976, the group founded SKC—then called Sunkyong Chemicals Ltd.—and went on to become Korea’s pioneer in polyester film production, building the capability through its own efforts rather than simply importing it. That insistence on developing in-house technology became part of the company’s identity.

Vertical integration did what it always promises to do when executed well: it made Sunkyong harder to squeeze. When input prices spiked, the group wasn’t just a buyer getting punished—it was also a producer capturing value. When markets softened, it had internal cushions that single-link competitors didn’t.

By the early 1990s, SK had effectively completed the petroleum-to-fibers buildout. It had climbed to become South Korea’s fifth-largest chaebol, behind only Hyundai, Samsung, Lucky-Goldstar (later LG), and Daewoo, generating more than $14 billion in total revenues, with roughly 58 percent coming from its petroleum and chemicals engine.

And yet, even as that engine started to hum, Chey Jong-hyon was already thinking about what it couldn’t do. Energy and chemicals could throw off stable cash—but they also came with commodity cycles and a ceiling on growth. The next leg of SK’s rise would come from somewhere completely different, and it would force the group into one of the most consequential pivots in its history.

V. The Telecom Gamble: Entering Mobile Communications (1994–2002)

In the early 1990s, mobile phones were still a status symbol—clunky, expensive, and mostly seen in the hands of executives. It wasn’t obvious they’d become a basic utility. But inside SK, the conclusion was already forming: petroleum and chemicals could power the company, but they couldn’t be the whole future. SK needed a new engine—one that wasn’t tied to commodity cycles.

So in June 1994, SK made a move that looked almost out of character. It entered telecommunications by becoming the largest shareholder of Korea Mobile Telecommunication Service. Less than two years later, in January 1996, SK Telecom launched Korea’s first commercial CDMA cellular phone service in Incheon and Bucheon.

This was a clean break from “From Petroleum to Fibers.” Refining and petrochemicals are about physical inputs, heavy assets, and manufacturing discipline. Telecom is about networks, software, service, and regulation—plus the messy reality of selling to millions of consumers. The playbook SK had mastered didn’t automatically translate. The company had to learn a new business from scratch: building national infrastructure, managing handset ecosystems, handling customer service at scale, and navigating a tightly controlled policy environment.

And that last piece mattered. SK’s path into mobile came with political complexity—the kind that always seems to appear when a chaebol tries to enter a strategically important industry. Licenses, administrations, and shifting policy winds shaped the route. But once SK secured its position, the asset didn’t just diversify the group. It changed what SK could become.

SK Telecom quickly established itself as Korea’s technology leader in mobile communications. In 2002, it launched the world’s first commercial CDMA 1X EV-DO technology, enabling 3G service. In 2004, it enabled satellite DMB by deploying the world’s first DMB satellite. Then came the push into “3.5G”: in May 2006, SK Telecom started the world’s first commercial HSDPA service, and in the following year completed construction of a national HSDPA network.

These weren’t just marketing claims. They were genuine “world firsts” that turned SK Telecom into a proving ground for the mobile future—one reason Korea became synonymous with cutting-edge networks long before most countries had reliable 3G.

The timing couldn’t have been better. Korea’s consumers embraced mobile technology with astonishing speed, and SK Telecom captured the leading position. Suddenly, SK had something it had never really had before: a consumer-facing, recurring-revenue, cash-generating machine—one that could bankroll the next set of big bets.

Then the Asian financial crisis hit in 1997. The shockwaves ripped through the region, taking down banks and crushing overleveraged conglomerates. In Korea, some of the biggest names didn’t survive—Daewoo and Hanbo among them. SK made it through, battered but intact. And in 1998, the group rebranded from Sunkyong to SK, signaling a slimmer, more future-oriented identity built around innovation and efficiency, not just industrial scale.

Telecom also coincided with a generational handoff. Chey Jong-hyon’s son, Chey Tae-won, had been rising inside the group—and in 1998, at age 37, he became chairman. He would lead SK through its most turbulent and transformative era yet: rapid expansion, governance crises, prison, and reinvention.

SK Telecom remained the centerpiece of the group’s ICT identity. As of the third quarter of 2024, it recorded sales of KRW 4.532 trillion, operating profit of KRW 533.3 billion, and net profit of KRW 280.2 billion, with a debt-to-equity ratio of 134 percent.

But the bigger point isn’t any single quarter. It’s what SK discovered in the 1990s: if you could take the discipline of a heavy-industry chaebol and pair it with a fast-moving technology platform, you could build something far more powerful than a refinery or a fiber mill.

And that power—cash flow, national importance, and strategic leverage—set the stage for the next chapter, when SK’s vulnerabilities would be exposed in public, and its control of the group would be challenged head-on.

VI. Crisis and Controversy: The Accounting Scandal and Sovereign Battle (2003–2005)

The early 2000s delivered the kind of moment every chaebol fears: the point where size stops protecting you and starts attracting scrutiny. Korea was climbing out of the Asian Financial Crisis, but the governance shortcuts the crisis had exposed were still everywhere. At SK, those weaknesses didn’t stay theoretical for long.

In 2003, investigators uncovered accounting irregularities at SK Global, the group’s trading arm. Prosecutors accused the company of inflating profits by more than $1.2 billion—one of the largest corporate accounting frauds in modern Korean history. The fallout was immediate and public: ten senior executives were arrested and convicted, including SK Group chairman Chey Tae-won.

It’s worth separating what happened next, because the timeline can blur. Years later—unrelated to the 2003 accounting scandal—Chey faced another major legal case. In January 2012, he was indicted for allegedly embezzling over $40 million from SK companies to cover trading losses. He denied wrongdoing. In January 2013, he was found guilty and sentenced to four years in prison by the Seoul District Court, remaining incarcerated near Seoul until he was pardoned in August 2015. But back in the mid-2000s, after the SK Global scandal, Chey ultimately returned and continued to lead the group.

The 2003 crisis also drew in an outsider who smelled blood in the water: Sovereign Asset Management, a Dubai-based activist fund. Sovereign accumulated shares and went after SK’s governance head-on, challenging not just management decisions but the legitimacy of the control structure itself. The confrontation became so high-profile that SK moved to protect itself by reshaping its corporate architecture. SK Holdings was established as SK Group reorganized its crown-jewel refiner, SK Corporation, into a holding company structure—an effort closely tied to the Sovereign battle and its aftermath.

Sovereign didn’t succeed in removing Chey Tae-won, but the attack exposed something uncomfortable in plain daylight: the gap between ownership and control. The Chey family’s direct equity was far smaller than most people assumed. Control came from the classic chaebol playbook—cross-shareholdings, circular stakes, and carefully placed control points that let a small slice of ownership steer a massive industrial fleet.

And even after the reorganization, the structure still looked shaky to critics. SK Holdings might have been labeled a holding company, but SK C&C—the group’s IT services provider—effectively controlled the group through its 31.8% stake in SK Holdings.

In the end, the Sovereign episode didn’t topple SK. It hardened it. The activist challenge forced the group to confront the reality that global capital markets were no longer passive—and that governance could become a strategic vulnerability. The solution SK pursued over the following decade was a slow-motion reworking of the ownership map: simplify where possible, look more transparent, and still keep family control intact.

For investors, it was the chaebol paradox in one clean case study. The risks were real—governance failures serious enough to produce criminal convictions. And yet the system held: the businesses kept running, the family kept control, and SK kept moving. In most countries, a scandal like this can permanently cripple a company. In Korea’s chaebol ecosystem, it was a crisis—then a restructuring—then the next chapter.

VII. Holding Company Transformation and the SK Hynix Acquisition (2007–2015)

After the Sovereign fight, SK did what chaebols often do when the spotlight gets too hot: it redrew the org chart.

In 2007, the group adopted a holding company structure. SK Corporation was split in two—an operating company, SK Energy, which kept the core refining and energy business, and a holding entity, SK Holdings, which would sit above the rest of the group with equity stakes across the affiliates.

This is the skeleton of today’s SK Inc. story. A relatively simple idea on paper: a control tower on top, operating companies underneath—names like SK Energy, SK Telecom, SK Networks, SKC, SK E&S, and SK Shipping. Compared to the tangled cross-shareholding webs that had defined earlier chaebol governance, it was meant to look cleaner, more legible, and more defensible to global capital.

Then came the move that reshaped SK’s future far more than any org chart ever could: Hynix.

In 2012, SK acquired Hynix Semiconductor in a deal of roughly $3 billion, turning semiconductors into a third pillar alongside energy and telecommunications. It’s hard to overstate how big that was for the group. The acquisition was so central to SK’s identity and trajectory that the company effectively began telling its modern story in two eras: before Hynix, and after.

The backdrop mattered. Hynix was born inside the Hyundai universe—founded in 1983 as Hyundai Electronics, later taking the name “Hynix” (from “Hyundai” and “Electronics”) as it tried to reinvent itself. But the memory business is brutal, and when chip prices collapsed in 2001, Hynix was crushed, posting an annual loss of roughly ₩5 trillion. It survived through restructuring and creditor support, but it remained a wounded asset—strategically important, capital-hungry, and perpetually on the edge of the next cycle.

When creditors finally moved to sell their stakes, the bidding field thinned. Other bidders dropped out, leaving SK Telecom as the buyer and the tip of the spear for SK Group. And with that, SK suddenly owned a world-class memory company: a major producer of DRAM and flash memory, and one of the largest global players in the sector—second in Korea only to Samsung.

At the time, not everyone saw the fit. Telecom is a regulated consumer network business. Semiconductor manufacturing is an unforgiving, global, capex-heavy technology arms race. The “synergy” wasn’t obvious.

But Chairman Chey Tae-won’s bet wasn’t about neat overlap. It was about inevitability. As more of the economy became digital, memory wouldn’t just be another component—it would be foundational infrastructure. If SK could own a leading memory producer, it wouldn’t just diversify away from oil cycles and telecom saturation. It would plant itself directly in the supply chain of the modern world.

By the mid-2010s, SK was still working through another, quieter challenge: control. Even with the holding company structure in place, critics kept pointing to an odd reality—SK C&C, the group’s IT services provider, still effectively controlled SK Holdings through its stake. The diagram might have looked cleaner, but the power lines still didn’t match the labels.

So in 2015, SK made the cleanup move that locked the structure in place: it merged SK Holdings and SK C&C. The combined company enabled Chey Tae-won and related parties to hold more than a 30% stake in the new SK Holdings, a dramatic consolidation compared to the pre-merger situation, when Chey’s stake in the former SK Holdings was only 0.02 percent.

The merger didn’t just simplify. It hardened control. It removed the awkwardness of a “subsidiary” controlling the holding company above it, and it shifted family influence toward more direct shareholding rather than circular ownership. Governance concerns didn’t disappear—this is still a chaebol—but SK emerged with a structure that was easier to explain, harder to attack, and better suited to the next phase of global expansion.

VIII. The Chairman's Turbulence: Embezzlement, Prison, and Pardon (2012–2015)

In 2012—the same year SK pulled off the Hynix acquisition—Chairman Chey Tae-won ran headfirst into a crisis that threatened to take the group’s transformation off the rails.

In January, prosecutors indicted him for allegedly embezzling more than $40 million from SK affiliates to cover trading losses tied to personal derivatives speculation. The accusation was straightforward and damaging: corporate money, used to patch a personal hole. Chey denied wrongdoing, but in January 2013 a Seoul court found him guilty and sentenced him to four years in prison.

In a Western public company, a chairman going to prison usually triggers a clean break: resignations, emergency succession plans, a forced “new era.” SK didn’t really do clean breaks. Chey was incarcerated near Seoul, operations continued under professional managers, and the group kept executing. The leadership structure held—less because the situation was comfortable, and more because chaebols are built to absorb turbulence at the top.

Chey returned in August 2015, after receiving a pardon from President Park Geun-hye. By then, presidential clemency for convicted chaebol leaders had become a familiar part of Korea’s political economy—often defended as pragmatic, because these groups sit so close to national employment, exports, and capital markets.

Under Chey’s tenure, SK rose into the #2 slot among Korea’s corporate groups. He pushed semiconductors—and later artificial intelligence—as the next growth engines, while also pursuing “rebalancing” efforts to streamline affiliates as the group expanded and debt levels rose.

Formally, Chey served as Chairman of SK Inc., overseeing more than 175 SK-branded companies spanning energy, chemicals, telecommunications, semiconductors, biopharmaceuticals, and trading services. Over nearly three decades, he held leadership roles across the group’s operating companies—an unusually long run at the center of a chaebol that was repeatedly reinventing itself.

His turbulence wasn’t only corporate. Chey was married to Roh Soh-yeong, an art director and the daughter of former South Korean president Roh Tae-woo. They separated in September 2011, and in December 2015 Chey announced his intention to divorce. The legal battle dragged on for years: in December 2022, the Seoul Family Court approved the divorce, and Chey kept most of his shares. The court also ordered him to pay $1 billion to his former wife. In October 2025, the Supreme Court of Korea overturned that settlement and ordered a review, citing a miscalculation that had increased the assessed value of the couple’s assets.

By May 2025, SK Group had 363 trillion won in assets, according to the Korea Fair Trade Commission. And that divorce litigation wasn’t tabloid noise—it created real investor anxiety that a massive settlement could force share sales and destabilize the group’s control structure. The Supreme Court’s October 2025 reversal offered at least temporary relief.

Chey’s public profile has long extended beyond SK. He received distinctions including “Global Leaders for Tomorrow” at the World Economic Forum (1999); served as Co-Chair of the East Asia Economic Summit in Malaysia (World Economic Forum, 2002); joined the Brookings International Advisory Council (2010); and served as Working Group Convener for the G20 Business Summit (2010). He earned a bachelor’s degree in physics from Korea University and a PhD in economics from the University of Chicago.

For anyone trying to underwrite SK Inc., this era crystallizes the central tension. On one side: serious governance risks—criminal convictions, legal overhang, and a control structure that can hinge on the personal stability of one person. On the other: remarkable continuity. Even with the chairman in prison, SK kept operating—and kept making long-cycle bets that would define its next decade.

IX. The EV Battery Bet and Green Transition (2017–2023)

When Chairman Chey returned to active leadership, the ground under SK’s legacy businesses was already moving. Climate change was rewriting energy policy. EVs were no longer a Silicon Valley science project—they were a direct attack on gasoline demand. Renewable power kept getting cheaper. And a group built on refining and petrochemicals could see the risk clearly: the old cash engines might keep running for years, but the long-term direction of travel was unmistakable.

SK’s answer was to go on offense. The group poured money into electric-vehicle batteries, green hydrogen, and adjacent technologies, positioning itself not just as an energy company, but as a contender in the energy transition.

Inside batteries, SK didn’t bet only on cell manufacturing. It spread capital across the supply chain—advanced materials like the copper foil that sits inside batteries, and even charging infrastructure. One emblematic move was SK Siltron CSS, created after an acquisition in 2020, which produces silicon-carbide wafers that can make EV power electronics more energy efficient.

The flagship bet, though, was BlueOval SK, the joint venture with Ford Motor Company. Formed in 2021 between Ford and SK On, the plan was to build three battery plants in the U.S.: two in Kentucky, plus one at Ford’s massive, roughly 6-square-mile manufacturing site in rural West Tennessee. Together, the project represented a combined $11.4 billion investment.

It was announced with the kind of fanfare reserved for industrial moonshots—one of the largest manufacturing commitments in Ford’s history, and a marquee example of a foreign company helping rebuild American manufacturing capacity. On paper, the logic was clean: SK brought battery know-how; Ford brought the vehicles, the brand, and the demand.

SK’s push wasn’t limited to batteries, either. The group also placed big bets on hydrogen and nuclear. In 2021, SK E&S and SK Inc. invested $1.6 billion in Plug Power, a hydrogen fuel cell company—an investment that made SK Plug’s largest shareholder. In 2022, SK Innovation and SK Inc. invested $250 million in TerraPower, the next-generation nuclear developer co-founded by Bill Gates.

All of this added up to a major U.S. footprint. SK said it would invest more than $52 billion in the United States by 2025, including a $22 billion commitment across semiconductors, green energy, and bioscience projects. The effort was expected to create more than 15,000 jobs, with plans to grow its U.S. workforce from 4,000 to 20,000 people by 2025.

But the battery story, in particular, turned out to be harder than the announcement-stage narratives. SK On—the battery business spun off from SK Innovation in October 2021—struggled with persistent losses and had not generated a profit since the split. The timing didn’t help: a prolonged slump in global EV demand hit just as the industry was absorbing huge up-front costs for factories, equipment, and ramp-up.

Even the Ford partnership evolved in ways few would have predicted at launch. SK On later said it reached an agreement with Ford to end the joint venture and divide the assets: Ford would take ownership and operation of the two Kentucky plants, while SK On would operate the Tennessee factory at the BlueOval SK campus. SK On said it would maintain a strategic partnership with Ford centered on the Tennessee plant.

The change amounted to a reset—part of a broader overhaul as battery makers recalibrated for slower EV adoption, changing subsidy dynamics, and the need to diversify beyond passenger EVs. SK On framed the move as a way to focus on growth areas like energy storage systems, and said the restructuring would expand its standalone U.S. production capacity from 22 gigawatt-hours to 67 gigawatt-hours annually.

In other words: the bet didn’t go away. It got rewritten. And like so many SK pivots before it, the real story wasn’t a single joint venture—it was the group’s willingness to keep reshaping itself around whatever it believed would become the next industrial baseline.

X. The AI Memory Revolution: SK Hynix's Moment (2024–Present)

While the battery business was grinding through losses and slower-than-hoped EV demand, SK’s other “future pillar” suddenly turned into the group’s biggest source of momentum. The AI boom didn’t just lift semiconductors in general. It created a very specific choke point in the supply chain: high-bandwidth memory. And SK Hynix had spent more than a decade getting ready for exactly this moment.

High-bandwidth memory, or HBM, is a specialized architecture that stacks multiple DRAM chips vertically to deliver extreme data throughput. That matters because modern AI accelerators are starved for memory bandwidth. You can have all the compute in the world, but if the model can’t be fed fast enough, performance collapses. For years, HBM was a promising niche. Then generative AI hit, and it stopped being niche overnight.

In 2024, SK Hynix posted the best annual results in its history: revenue of 66.1930 trillion won, operating profit of 23.4673 trillion won, and net profit of 19.7969 trillion won. Revenue set an all-time record, topping the previous high in 2022 by more than 21 trillion won, and operating profit surpassed the company’s prior peak from the 2018 semiconductor super-cycle. The jump was driven by HBM: sales surged, and total revenue was up 102% year-on-year.

The shift showed up not just in SK Hynix’s own numbers, but in the industry scoreboard. Reuters reported that SK Hynix’s fourth-quarter operating profit exceeded Samsung’s forecast of 6.5 trillion won for the same period—meaning that, for the first time, SK Hynix’s quarterly semiconductor profit topped Samsung’s.

Inside the company, the story was the mix. SK Hynix said its HBM sales jumped 4.5-fold in 2024 from the year prior, and by the fourth quarter, HBM made up over 40% of total DRAM revenue. Looking ahead, the company forecast HBM sales would grow another 100%.

A key enabler was its relationship with Nvidia, the defining customer of the AI era. SK Hynix’s ability to supply HBM at the scale and performance the market needed put it in the center of the AI hardware stack. As TSMC CEO C.C. Wei put it: “SK hynix has been at the forefront of delivering cutting-edge HBM technologies, and its dedication to innovation has significantly contributed to shaping the future of AI. High-bandwidth, low-power memory solutions have transformed the AI workload, pushing the boundaries of what AI systems can achieve.”

Demand stayed so strong that SK Hynix said its HBM chips were sold out for the year and were almost sold out for 2025 as well—an extraordinary position in a business that usually lives and dies by the cycle.

And the company didn’t slow down. In March 2025, SK Hynix became the first in the industry to supply 12-layer HBM4 samples to major customers, with mass production slated for the second half of the year. SK Hynix said it had completed development and finished preparation for HBM4 mass production, framing it as another proof point of leadership in AI memory.

At the SK AI Summit 2025 in Seoul, held November 3–4 under the theme “AI Now & Next,” SK Hynix laid out its next-generation AI memory strategy and roadmap. It described an evolution in ambition—from becoming a full-stack AI memory provider to taking on a broader role as a full-stack AI memory “creator.”

The buildout wasn’t only in Korea. In April, SK Hynix signed an investment agreement to build an advanced packaging production facility in Indiana, aimed at producing next-generation HBM and AI memory. That same month, it also entered a technology agreement with TSMC, designed to establish a collaborative framework between the customer, the foundry, and the memory provider—an attempt to push past technical limits and stay ahead in the AI race.

Put it all together and you get the sharpest illustration of why the chaebol model still works—until it doesn’t. SK’s battery unit could be losing money at the same time its memory business prints record profits, and the group as a whole keeps moving forward. That’s portfolio resilience in action. But it also comes with the other side of the bargain: running a conglomerate means fighting on multiple battlefields at once, each with its own cycles, competitors, and rulebook.

XI. Restructuring and Rebalancing: The 2024–2025 Transformation

By 2024, SK’s portfolio was doing two very different things at once. On one side: AI memory, exploding. On the other: batteries and other “green” bets, still deep in investment mode, with losses and cash needs piling up. That gap is what triggered SK’s most aggressive restructuring push in decades—an effort to lighten the financial load from unprofitable affiliates and make the whole machine easier to manage.

One analyst at Korea Investors Service put the pressure plainly: SK Group’s debt reached 87 trillion won in 2023, driven largely by large-scale battery investment. And with SK continuing to fund both semiconductors and batteries, the risk was that the number would keep rising. The same analyst argued that SK’s investments in eco-friendly energy hadn’t yet produced meaningful outcomes—exactly the kind of critique that forces a conglomerate to choose what it will defend, and what it will cut.

The restructuring centered on a few big moves.

First, SK moved to consolidate its energy base—building scale and, more importantly, cash-flow stability. SK launched a merger between SK Innovation and liquefied natural gas supplier SK E&S, a major step in its broader restructuring as electric-vehicle demand cooled and geopolitical uncertainty climbed. SK Innovation—parent of South Korea’s largest oil refiner, SK Energy, and battery maker SK On—absorbed the country’s top city gas supplier. The combined entity was positioned as the largest private comprehensive energy company in the Asia-Pacific region, excluding state-run utilities, with assets of 105 trillion won as of the end of June. SK E&S, known for steadier cash flow, was set to be rebranded as SK Innovation E&S as a “company within a company” under SK Innovation.

The merger was formally completed and the new entity launched on November 1, after preparations that followed the July announcement. The logic wasn’t subtle: SK E&S’s LNG cash flows could help carry SK On through its loss-making ramp while the battery market matured. The merged entity said it was targeting EBITDA of 20 trillion won by 2030, driven by a stronger portfolio, a better financial structure, and new growth momentum.

Second, SK accelerated the sell-down of anything that didn’t fit the core story. This was the continuation of the group’s “rebalancing” campaign: divest non-core assets, simplify the affiliate map, and focus resources on a smaller set of future engines. SK said that through portfolio readjustment since last year it had reduced 82 affiliates and cut short-term borrowings by 38%.

You could see the simplification in the numbers. The count of consolidated subsidiaries fell from 716 in 2023 to 634 as of the end of June this year. SK Inc.’s semi-annual report also showed consolidated subsidiaries declining from 649 at the end of 2024 to 634 in the first half of 2025, reflecting 44 companies that were divested, liquidated, merged, or removed from consolidation.

Third, the restructuring reached into leadership itself. SK ecoplant went through a major executive reshuffle—part of what looked like a wider shakeup across the group. On Oct. 17, SK announced plans to cut the number of executives by more than 20% across affiliates, with SK ecoplant leading the charge. It was described as unusually early and unusually sweeping—bigger than what SK had done even during past leadership vacuums or global crises—and framed internally as a broader shift in how the conglomerate would operate.

SK also elevated executives associated with its overhaul efforts into top roles at intermediary holding company SK Discovery and at SK On, aiming to speed up restructuring execution inside two areas with very different needs: corporate simplification on one hand, and survival-plus-scale on the other.

Alongside those structural moves were a few telling signals about where leadership attention was going. In November 2024, Chairman Chey Tae-won was appointed chairman of the board of Soldigm, SK Hynix’s U.S.-based NAND flash memory unit. And on Dec. 23, 2024, SK sold 85 percent of its subsidiary SK Specialty to Hahn & Company.

Taken together, the message of 2024–2025 was clear. SK was drawing a line around what mattered most: semiconductors—especially AI memory—plus batteries, even with the losses, plus a consolidated energy platform built to keep the rest funded. Everything else, no matter how prestigious or long-held, was suddenly on the table.

XII. Strategic Analysis: Bull Case, Bear Case, and What to Watch

The Bull Case for SK Inc.

The optimistic read on SK starts with one simple idea: the group happens to own one of the most important bottlenecks in the AI era. SK Hynix’s position in high-bandwidth memory gives it outsized leverage to the buildout of AI infrastructure. HBM has become critical to modern AI acceleration, and SK Hynix entered this moment with both scale and credibility—products effectively sold out through 2025, and a roadmap that extends into HBM4. If AI demand keeps compounding, SK Hynix could produce a run of profits big enough to cover a lot of pain elsewhere in the portfolio.

The second pillar is patience on the energy transition. Batteries are hurting now, but the bull case says that’s the cost of getting positioned early. If EV adoption re-accelerates, SK On’s manufacturing footprint becomes an asset, not a burden. And because SK sits across multiple parts of the energy value chain—oil, LNG, batteries, and hydrogen—it has more than one path to participate in whatever the transition ends up looking like.

Third is the structure itself. As a holding company, SK Inc. gives investors exposure to several major businesses in one wrapper. The pitch is that the wrapper is cheap: SK Inc. trades at a discount to the sum of its stakes, meaning the market value of its major holdings—like SK Hynix and SK Telecom—can exceed SK Inc.’s own market capitalization. If sentiment improves and that discount narrows, shareholders can win even without heroics from every subsidiary.

The Bear Case for SK Inc.

The skeptical case begins where it often begins for chaebols: governance. The chairman’s legal history, the long-running divorce-related overhang, and the reality of concentrated family control all create uncertainty that markets may never fully price away. Korea’s pattern of convictions followed by pardons may keep the machine running, but it also keeps questions about accountability and oversight permanently in the background.

Then there’s batteries. The business has required heavy capital and, so far, hasn’t delivered profitability. SK On has not generated positive operating income since the spinoff, and the unwind of the Ford joint venture undercuts what was originally presented as a marquee growth platform. At the same time, Chinese competitors have been taking share with cost structures that are hard for Korean players to match.

Finally, critics argue the conglomerate model can destroy value in plain sight. When a highly profitable business like SK Hynix throws off cash while a unit like SK On burns it, the holding company can start to look like a mechanism for cross-subsidization—transferring value from winners to laggards—rather than a vehicle for smart capital allocation.

Porter's Five Forces Analysis

Supplier Power: Moderate. In semiconductors, key equipment suppliers like ASML and Applied Materials have meaningful leverage. In batteries, raw materials such as lithium, cobalt, and nickel bring price volatility. Energy businesses live with commodity exposure by definition.

Buyer Power: Mixed. In HBM, customers like Nvidia and AMD have limited alternatives, which strengthens SK Hynix’s pricing power. In batteries, automakers can often dual-source or switch suppliers, pressuring margins. Telecom customers tend to face switching friction, but price competition still matters.

Threat of Substitutes: Low to moderate. There’s no obvious near-term substitute for HBM in AI acceleration. Batteries could eventually face disruption from alternatives like solid-state designs or fuel cells, but widespread commercial displacement appears years away. Telecom faces substitution pressure from Wi‑Fi and internet-based communications.

Threat of New Entrants: Low in semiconductors due to extreme capital needs and technical barriers. More moderate in batteries, where new Chinese entrants continue to scale. Low in telecom, given regulation and the cost of national infrastructure.

Competitive Rivalry: Intense. Samsung is a powerhouse in memory and devices. CATL and BYD are major threats in batteries. In telecom, SK competes with LG and KT. In almost every arena SK plays in, it faces world-class rivals.

Hamilton Helmer's 7 Powers Framework

Scale Economies: Clear in memory manufacturing, refining, and telecom—businesses with high fixed costs and strong benefits from volume.

Network Effects: Limited. SK Telecom can benefit from network effects in some platform-adjacent services, but core connectivity is not a classic network-effects moat.

Counter-Positioning: SK Hynix’s emphasis on premium HBM, while competitors pursued broader approaches, can be seen as a form of counter-positioning that paid off as AI demand surged.

Switching Costs: Moderate in telecom through contracts and bundled services. High in enterprise memory, where qualification, reliability, and integration make switching slow and risky.

Branding: Relatively limited outside Korea. SK does not have global consumer brand reach on the level of Samsung or Hyundai.

Cornered Resource: SK Hynix’s HBM engineering talent and process know-how function like a proprietary capability that’s difficult to replicate quickly.

Process Power: Strong in memory, where decades of accumulated learning translate into yield, cost, and time-to-market advantages.

Key Performance Indicators to Watch

For anyone tracking SK Inc. going forward, three indicators capture the story better than a dozen headline numbers:

-

SK Hynix HBM Revenue Share of Total DRAM Revenue: This is the cleanest signal of whether the AI memory mix shift is deepening. It’s already above 40%. If it holds there or moves higher, it suggests the AI-driven upgrade cycle is not just a spike, but a structural change.

-

SK On Operating Profit (Loss): This is the make-or-break metric for the battery bet. Investors will be watching for a steady march toward breakeven and then sustained profitability as factories ramp and demand stabilizes.

-

SK Inc. Holding Company Discount to NAV: The gap between SK Inc.’s market capitalization and the value of its disclosed stakes is effectively the market’s scorecard on governance, capital allocation, and complexity. A narrowing discount implies rising trust; a widening one signals the market still believes the structure is a drag.

XIII. Conclusion: The Next Chapter

SK Inc. is back at one of those rare moments where the next few moves can redefine the whole story.

A company Chey Jong-gun pulled from war rubble and restarted with fifteen looms is now an industrial portfolio that touches daily life in Korea and supply chains around the world. The old through-line still holds: start with something essential, then climb upstream and downstream until you control the system. “From petroleum to fibers” became telecom networks, then semiconductors, then batteries—and now, increasingly, the infrastructure of AI.

What makes this moment feel different is that the forces reshaping SK are arriving all at once. AI is pulling high-bandwidth memory into the center of the global compute stack, and SK Hynix is having the kind of cycle-defining run that can change a conglomerate’s balance of power. At the same time, SK’s battery ambitions are being rewritten in real time, with losses, factory ramps, and partnerships being restructured rather than celebrated. And underneath it all, the group is consolidating its energy operations to generate the cash flow needed to fund the future without overloading the balance sheet.

Chey Tae-won framed that arc himself at Tokyo Forum 2024: "In its 70-year history, SK Group has expanded its business from textiles to oil and telecommunications, and has innovated its portfolio with semiconductors and AI."

He’s also been explicit about what comes next. Chey has renewed his commitment to building a broader AI ecosystem—and to tackling the bottlenecks in that ecosystem with the partners that matter most, including Nvidia and TSMC.

For investors, SK Inc. remains exactly what it has always been—powerful, complicated, and not easily reduced to a clean narrative. You get exposure to a world-leading AI memory franchise through SK Hynix, alongside a battery business still in the hard, cash-burning phase of industrial scale-up, plus stable telecom cash flows—and the ever-present governance questions that come with family-controlled chaebols. The holding company structure diversifies risk, but it also bundles winners and laggards together, forcing you to underwrite the whole machine, not just the best asset.

And that’s the final lens to hold onto: SK isn’t just a company operating in Korea. It’s part of the system that built modern Korea. The country’s rise from poverty to high-income industrial power—the Miracle on the Han River—was powered in large part by chaebols like SK, and SK’s next transformation will matter well beyond its own shareholders.

The quiet giant behind Korea’s second chaebol is now competing in the markets that will define the next decade: artificial intelligence, clean energy, and advanced manufacturing. The open question is whether this is the start of a new era of leadership—or the sound of a sprawling empire straining under the weight of its own ambitions.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music