Samsung Life Insurance: The Keystone of Korea's Mightiest Chaebol

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

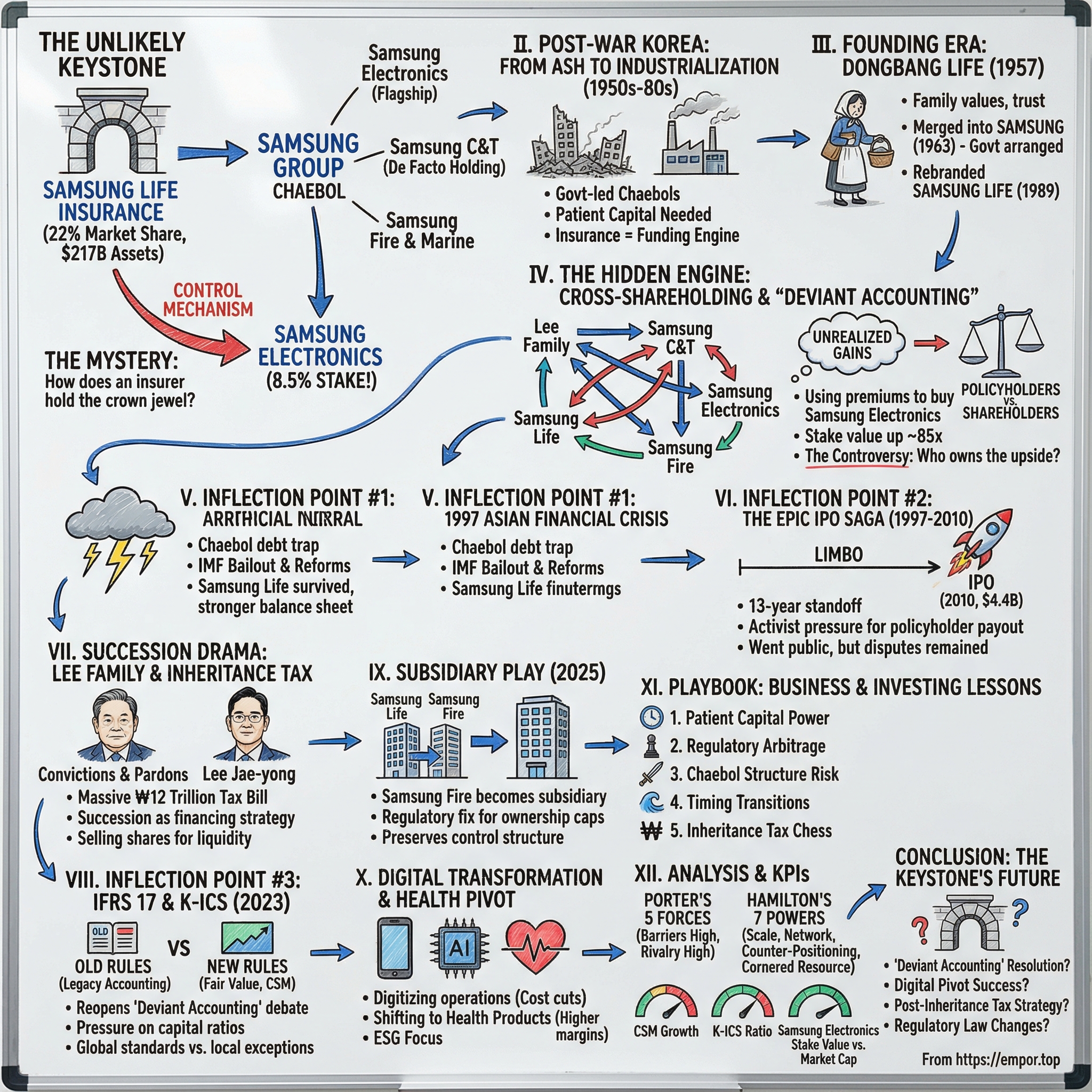

Picture this: you’re trying to figure out how one family can steer a roughly $400 billion electronics empire while owning less than 2% of the shares outright. You pull org charts. You follow voting rights. You read regulatory filings until your eyes blur. And then, in the middle of all that complexity, one entity keeps showing up like a recurring character in a thriller.

Not a chipmaker. Not a phone division. Not even a trading company.

An insurance company.

Samsung Life is South Korea’s largest life insurer, with about 22% of the market—nearly double each of its two biggest rivals. On the surface, that’s a dominance story about premiums, agents, and household financial products. But Samsung Life’s real importance isn’t what it sells. It’s what it owns—and who sits upstream of it.

Samsung C&T, the group’s de facto holding company, is Samsung Life’s largest shareholder. And Samsung Life is the largest shareholder in Samsung Electronics, the crown jewel of the entire Samsung Group. That isn’t corporate trivia. It’s the control mechanism. Decades of careful design, regulatory navigation, and what critics have branded “deviant accounting” turned a staid insurer into the structural beam that supports the whole building.

Here’s the part that makes you sit up: Samsung Life owns close to 15% of Samsung Fire & Marine, the country’s largest nonlife insurer. And it owns 8.5% of Samsung Electronics—an investment worth well more than Samsung Life’s own market capitalization. Read that again. One insurance company holds a stake in the flagship operating company so valuable it can eclipse the insurer itself. In chaebol land, Samsung Life isn’t just another affiliate. It’s the keystone.

That sets up the central mystery: how did an insurer become the linchpin of Samsung’s corporate architecture, and why does that 8.5% stake in Samsung Electronics matter more than almost anything else in Korean corporate governance?

To answer it, we’re going to trace the story through post-war devastation and Korea’s economic sprint, through the Asian financial crisis and the legacy products that followed, through a 13-year fight to take Samsung Life public, and into succession dramas that include pardons, prison sentences, and eye-watering inheritance taxes. Then we’ll land in the present, where new accounting rules like IFRS 17 are forcing insurers to re-measure their promises—and, in Samsung Life’s case, threatening to reopen old battles over how value is counted and who it belongs to.

Yes, the numbers are huge: a record KRW 2.1 trillion net profit in 2024, up 11.2% year-on-year, and total assets of about $216.7 billion as of March 2025. But those figures don’t explain the power. The power comes from the uniquely Korean mix of patient capital, interlocking ownership, and regulatory chess—played over generations.

This is the story of Samsung Life Insurance: the quiet financial institution that became the beating heart of one of the world’s most valuable corporate empires.

II. Context: The Rise of the Chaebol and Post-War Korea

To understand Samsung Life, you have to start with the Korea it was born into—a country that looked nothing like today’s sleek, export-powered tech hub. When the armistice froze the Korean War in 1953, South Korea was shattered. Infrastructure was wrecked, families were uprooted, and the economy wasn’t just behind—it was starting over. The national task wasn’t “recovery” so much as invention: building a modern industrial economy from scratch.

Samsung itself began far from semiconductors. Lee Byung-chul founded it in 1938 as a trading company, and over the next few decades it expanded into the unglamorous but essential stuff: food processing, textiles, insurance, securities, retail. Only in the late 1960s did Samsung step into electronics—the move that would eventually make the brand global. But in the 1950s and 60s, the real strategic question was simpler: where would Korea get the capital to grow?

The country didn’t have deep capital markets or a mature banking system like the West. Under President Park Chung-hee, the government pursued an approach that became a defining feature of modern Korea: it would channel resources through a handful of family-controlled conglomerates that could execute national priorities quickly. These conglomerates—the chaebols—weren’t just big businesses. They were vehicles of state-led industrialization.

For decades, the relationship between Seoul and the chaebol was symbiotic. Political leaders tied national success to the success of these groups, and the groups, in turn, depended on state direction and support. It wasn’t simply favoritism; it was a development model that prioritized speed and coordination over transparency and pure market competition.

A chaebol, in plain terms, is a large Korean conglomerate controlled by a family, made up of many affiliated companies spanning different industries—bound together by ownership links and influence.

Inside that system, insurance mattered more than most outsiders realize. Life insurers collected small monthly premiums from millions of households and turned them into something Korea badly needed: long-term, stable pools of capital. Unlike bank deposits, insurance premiums could be invested over decades. Unlike stock investors, policyholders weren’t demanding quarterly performance—they were buying a promise. For chaebols trying to finance capital-heavy industrial projects, an insurance subsidiary wasn’t a side business. It was a funding engine.

Dongbang—Samsung Life’s origin story—was one of several insurers that took off by selling savings-linked policies in a tightly controlled economy. Its early sales force included Korean War widows going door-to-door, persuading friends, neighbors, and relatives to set aside money through insurance. The pitch was simple and powerful: you didn’t just get a policy, you bought a measure of security—and you earned a modest premium over what a bank deposit could offer. The insurers then invested and lent those funds, often into government-directed projects or to other chaebol.

That’s the landscape Samsung Life grew out of: a nation rebuilding from ash, a government steering development through family conglomerates, and insurers quietly collecting the patient capital that made the whole machine run. And as that machine delivered decades of growth—lifting Korea from poverty into global manufacturing leadership—it also fused the fate of the state and the chaebol so tightly that criticizing one often sounded like criticizing the other.

III. Founding Era: Dongbang Life and Samsung's Acquisition (1957-1989)

Dongbang Life began with a simple, almost idealistic premise: build a company rooted in family values, help ordinary people climb toward security, and “spread happiness.” In 1950s Korea, that was an ambitious mission statement—because life insurance itself was still a foreign concept to most households. The founders were stepping into a market that barely existed, betting that as the country rebuilt, families would want protection and long-term savings that the thin social safety net couldn’t yet provide.

On April 4, 1957, Dongbang Life Insurance Co., Ltd. was incorporated in Seoul—only four years after the armistice ended active fighting. The nation was still desperately poor. The financial system was underdeveloped. And the idea of paying a regular premium for a promise that might not pay out for decades required something Korea had little of at the time: trust.

Yet Dongbang found it. Within about 18 months, it had already risen to a market-leading position—an early signal of how hungry the public was for stability, and how effective the company was at making an unfamiliar product feel necessary.

A big part of that early momentum came from the way insurance was sold: person to person, face to face. Dongbang built a door-to-door sales force that included many Korean War widows looking for income. They brought the pitch into living rooms and neighborhood shops. The policies were simple and savings-oriented. You paid modest premiums, and over time you got both life coverage and a way to accumulate money in an era when bank deposits weren’t especially attractive and equity markets were still far from mainstream.

Then came the turning point.

In July 1963, Dongbang merged into Samsung. The phrasing matters: this wasn’t just a tidy corporate transaction. When Dongbang’s founding family ran into financial trouble, the government arranged the sale of what was then South Korea’s second-biggest insurer to the fast-rising Samsung Group. That one line—“the government arranged”—captures the development-era reality of Korea. Industrial policy often didn’t look like a public program; it looked like private companies being paired, steered, and scaled to serve national goals.

For Samsung’s founder, Lee Byung-chul, the strategic logic was obvious. Insurance companies didn’t just sell policies. They collected float: premiums that could be invested for years, sometimes decades, before being paid out. In a capital-hungry economy, float was patient money—exactly the kind that could quietly fund bigger industrial ambitions elsewhere in the group.

Under Samsung, Dongbang’s growth accelerated. As Korea’s prosperity rose through the 1960s, 70s, and 80s, the insurer expanded alongside it—helped by Samsung’s resources, a growing customer base, and an interest-rate environment that made long-term investing attractive for insurers. The company modernized too. In January 1971, it introduced computerized business procedures, becoming the first Korean life insurer to use technology at that level for underwriting and claims processing.

By the mid-1980s, the company was confident enough to start planting flags abroad, opening representative offices in New York and Tokyo in 1986. And by the end of the decade, Dongbang had become Korea’s biggest insurer, with assets on the order of $17 billion—no longer a scrappy post-war upstart, but a pillar of the financial system.

In July 1989, Samsung made the next move: it put its own name on the door. Dongbang Life Insurance officially became Samsung Life Insurance Co., Ltd., headquartered in Seoul.

The timing wasn’t cosmetic—it was tactical. South Korea was deregulating life insurance, and competition was about to explode. Almost immediately, dozens of new insurers entered the market, including a meaningful wave of foreign players, all eager to capture a newly opened Korea. But the incumbents weren’t left defenseless. Local firms, including Samsung, benefited from substantial tax and other advantages, and Samsung also brought something even harder for newcomers to replicate: a brand that had spent decades intertwined with Korea’s industrial rise.

The rebranding was a declaration. In a market that was about to get noisier and more crowded, Samsung Life wasn’t going to compete as just another insurer. It was going to compete as Samsung.

IV. The Hidden Engine: Cross-Shareholding and Chaebol Control

If the founding era was about building an insurer, the decades that followed were about building a control system. This is where Samsung Life stops looking like a normal financial company and starts looking like infrastructure. And it’s also where the story turns controversial.

To understand why Samsung Life matters inside the Samsung Group, you have to understand how chaebols are controlled. In a typical Western conglomerate, shareholders elect a board, the board hires management, and control usually tracks ownership. Chaebols don’t work like that. The founding family’s influence is often routed through a web of cross-shareholdings: Company A owns part of Company B, which owns part of Company C, which owns part of Company A again. The circle creates leverage. The family can sit at the center with surprisingly little direct ownership, yet still steer the whole system.

Samsung Life is one of the most important nodes in that web. It owns close to 15% of Samsung Fire & Marine Insurance, Korea’s largest nonlife insurer. More importantly, it owns 8.5% of Samsung Electronics—an investment worth well in excess of Samsung Life’s own market capitalization. And Samsung Life itself is heavily held by related shareholders: 10.4% by Jay Lee, 6.9% and 1.7% by his sisters Boo-Jin and Seo-Hyun, 19.3% by Samsung C&T (often described as the group’s presumptive parent), 5.9% by E-mart (a retailer whose largest shareholders are Jay Lee’s aunt and cousin), and 4.7% by the Samsung Foundation of Culture.

That’s the leverage in plain terms: Samsung Life’s stake in Samsung Electronics carries enormous voting power at the flagship company, and the Lee family plus affiliates collectively hold a near-controlling position in Samsung Life. With the right links in place, modest direct ownership can translate into practical control over what became the world’s largest semiconductor and smartphone manufacturer.

The chain is especially telling when you look at the center of gravity. Samsung Electronics Chairman Lee Jae-yong held an 18.9% stake in Samsung C&T. Samsung C&T, in turn, owned 19.34% of Samsung Life. And Samsung Life sat downstream as a major shareholder of Samsung Electronics and Samsung Fire. It’s a governance relay race: influence passes from the family into a key affiliate, then into the insurer, then into the crown-jewel operating companies.

And that brings us to the issue critics have labeled “deviant accounting”—a dispute that has simmered for decades and spilled back into policy debate in 2025.

The roots go back to the 1980s, when Samsung Life used premiums from participating insurance policies to buy Samsung Electronics shares. Participating insurance is designed so that a portion of investment profits can be returned to policyholders as dividends. The premiums are relatively high, but the promise is that if the insurer invests well, policyholders share in the upside.

Samsung Life invested those collected premiums into Samsung Electronics, acquiring about 540.1 billion won worth of shares—an 8.44% stake. By the prior day’s closing price, that stake was valued at nearly 46 trillion won.

That’s the staggering part: roughly an 85-fold increase. Money paid by ordinary Korean families—often as a disciplined form of long-term savings—ended up financing a stake in Samsung Electronics that compounded into one of the most valuable positions in Korean corporate history. Which raises the question that has never gone away: who should benefit from those gains?

Policyholders in participating products sued multiple times, arguing that the valuation gains should be shared with them. The courts repeatedly sided with Samsung Life, holding that profits should be distributed only after the shares are sold and gains are realized. Samsung Life could, in effect, delay paying dividends by arguing it wasn’t the right time to sell.

That’s the tension at the center of the structure. As long as the shares remain unsold, the gains aren’t “realized,” and participating policyholders don’t receive dividends tied to that appreciation. Yet those same shares still confer voting power in Samsung Electronics—power that strengthens Samsung Life’s role in the group, and by extension the Lee family’s influence.

Those policyholder interests were booked as a “policyholder’s equity adjustment” and kept within liabilities, a domestic treatment that has been called “deviant accounting” in Korea’s policy debate. Civic groups and some market participants have argued that this kind of exception clashes with the intent of IFRS 17.

IFRS 17 arrived in 2023 and made these questions harder to ignore, which we’ll get to later. But the core conflict was set decades earlier: Samsung Life accumulated a pivotal stake in Samsung Electronics using policyholder premiums, and the industry, the courts, and the public have never fully agreed on how—if ever—that value should be shared.

V. Inflection Point #1: The 1997 Asian Financial Crisis

Korea’s economic miracle didn’t end with a slow fade. It hit a wall in late 1997.

The panic didn’t start in Seoul. It started as currency pressure in Thailand, then rippled across Southeast Asia. But once it reached Korea, it found a system that had been built for growth, not for shock absorption.

By October, the credit spigot effectively shut off. Foreign banks began calling in loans and refusing to roll them over. Korea’s banks and industrial champions suddenly faced an impossible problem: they couldn’t refinance, and they couldn’t raise fresh funding at any price.

The underlying issue was leverage—staggering leverage. In 1997, the average debt-to-equity ratio in Korean manufacturing was close to 400%, about double the OECD average. For the top 30 chaebols, the figure was even higher, topping 500%. The same debt that had helped build Korea’s industrial base at warp speed now turned into a trapdoor.

And the trapdoor opened fast. Before and after the exchange-rate crisis, fifteen of the top thirty conglomerates were allowed to go bankrupt. In December 1997, South Korea accepted an international bailout package worth more than $50 billion, a record at the time. The rescue—led by the IMF—came with strings attached: reforms meant to weaken the old chaebol playbook, including stronger transparency requirements and reduced government support.

For Samsung Life, this was both a threat and an opening.

Insurers across Korea had loaded up on local corporate bonds and equities. When markets sank, those portfolios took huge mark-to-market hits. Smaller insurers, without scale or deep capital buffers, simply couldn’t survive the squeeze.

Samsung, as a group, came through the storm better than most. It wasn’t untouched—Samsung Motor was sold to Renault at a painful loss—but the core of the empire held. And Samsung Life, in particular, emerged stronger than many of its peers. Its balance sheet was comparatively conservative, its losses more manageable, and its most unusual asset—the stake in Samsung Electronics—was positioned for the long climb that would eventually come to define Samsung Life’s power inside the group.

The crisis also planted a time bomb for the entire insurance industry. In the scramble for premium income afterward, insurers pushed policies with high fixed-rate guarantees. When rates were high, those promises sounded safe, even generous. But as interest rates fell through the 2000s and 2010s, they became an expensive burden—exactly the kind of long-dated liability that would later collide with new accounting regimes and ignite today’s solvency and valuation debates.

Zooming out, the post-crisis reforms did change Korean capitalism. Chaebols carried less debt and became less vulnerable to a repeat—something Korea’s relative resilience in the 2008 crisis seemed to confirm. But consolidation also meant that fewer, larger conglomerates came to occupy an even bigger share of the economy.

So the 1997 crisis did what crises often do: it killed the weak, disciplined the survivors, and strengthened the winners. The government forced chaebols to reduce leverage, improve transparency, and focus on core businesses. Many conglomerates disappeared. But the fundamental structure—family control reinforced by cross-shareholdings—largely survived.

And Samsung Life stayed exactly where it mattered most: near the center of Samsung’s control architecture, quietly becoming even more essential in the new, post-IMF Korea.

VI. Inflection Point #2: The Epic IPO Saga (1997-2010)

By the late 1990s, Samsung Life had done what incumbents are supposed to do: it defended its home turf against new local entrants and foreign brands, it kept growing, and it looked like a natural candidate to become a regional powerhouse.

There was just one problem. It couldn’t go public.

What followed was a 13-year standoff that began in 1997 and didn’t end until 2010—an unusually long stretch of corporate purgatory for a company of Samsung Life’s size. The insurer sat in a strange limbo: too big to ignore, too politically sensitive to list.

At the center of the fight was a question that had already shadowed Samsung Life for decades, and would keep shadowing it long after the IPO: who, exactly, owns the value created from policyholder premiums?

Political activists and economic reformers argued that before Samsung Life could sell shares to the public, it should first return value to the people who had funded its rise—its policyholders—through a special dividend or another pre-IPO payout. They pushed hard for the support of President Roh Moo-hyun’s administration. “Over the past 40 years, policyholders and the government have shared some of the risks of Korean life insurance firms and therefore have the right to demand some of the rewards,” said Kim Hun Soo, a finance professor at Soon Chun Hyang University who helped lead the effort.

Samsung Life’s position was blunt: it was a joint stock company, not a mutual insurer. Policyholders were owed the benefits spelled out in their contracts—not an extra payday triggered by an IPO. Privately, Samsung and its peers also warned that a large policyholder payout would mean tapping reserves or effectively transferring value away from existing shareholders.

Reformers fired back that Samsung Life’s own history undermined that clean distinction. Kim, who was also a member of the People’s Solidarity for Participatory Democracy, pointed to a precedent: in 1989, the insurer paid policyholders an additional $100 million beyond dividends. To him, that was proof Samsung Life carried “some characteristics of mutual companies,” even if it wasn’t formally structured as one.

As the two sides dug in, the argument stopped being just a technical dispute about corporate form and started sounding like a referendum on post-crisis Korea: who deserves the upside when a national champion gets richer—capital providers and insiders, or the households whose premiums helped build the balance sheet in the first place?

Samsung executives stayed publicly quiet, but they were expected to fight in court if regulators tried to condition an IPO on a large policyholder payout. The activists promised they wouldn’t back down. “This isn’t about money,” Kim said. “It’s about the message we send as a society that it is all right for some shareholders who did not share all the risks to walk away with all the profits of the IPO, depriving policyholders who at one point did share some of the risks.”

Then, in May 2010, the deadlock finally broke.

Samsung Life, private from its founding in 1957, went public at last. The offering became the largest IPO in South Korean history up to that point, raising about $4.4 billion, or roughly KRW 6 trillion, at a share price of KRW 110,000. Overnight, Samsung Life was no longer just the country’s biggest life insurer—it was also one of its most valuable public companies by market capitalization.

The IPO solved the immediate, practical problem: Samsung Life now had access to public capital markets.

But it did not settle the underlying disputes that made the IPO so hard in the first place. Policyholder rights, the role of cross-shareholding in chaebol control, and the accounting treatment of massive unrealized gains on affiliate investments all remained. They didn’t disappear after 2010—they just went quiet again, waiting for the next trigger.

That trigger would arrive with IFRS 17.

VII. The Lee Family Succession Drama

To understand why Samsung Life sits where it does in the Samsung universe, you have to understand the Lee family. And to understand the Lee family, you have to understand that in Korea, chaebol succession isn’t a one-time event. It’s a multi-decade campaign—shaped as much by tax law and political legitimacy as by business performance.

Lee Kun-hee, who led Samsung from 1987 until his death in 2020, was the architect of Samsung’s modern identity. Under his watch, the group evolved from a large Korean conglomerate into a global technology powerhouse. He was also, by the late 2000s, the richest person in South Korea, with an estimated net worth of about US$21 billion at the time of his death.

But Lee’s era came with a recurring subplot: the uneasy, often transactional relationship between Korea’s biggest conglomerates and the state. He was convicted twice—once in 1996 and again in 2008 on corruption and tax-evasion-related charges—and he was pardoned both times.

The 2008 case became emblematic. On 16 July 2008, The New York Times reported that Seoul Central District Court found Lee guilty of financial wrongdoing and tax evasion. Prosecutors sought a seven-year prison sentence and a fine of 350 billion won. The court instead imposed a fine of 110 billion won and a three-year suspended sentence. Then, on 29 December 2009, President Lee Myung-bak pardoned him, saying the intent was to allow Lee to remain on the International Olympic Committee. The pardon sparked backlash; to critics, it looked like the usual rule—different outcomes for chaebol leaders. Later, that pardon itself became tied up in broader corruption allegations, and Lee Kun-hee returned to Samsung shortly after receiving it.

Then the next generation stepped into the same storm.

In February 2017, Lee Jae-yong—effectively Samsung’s leader—was arrested on charges including bribery, embezzlement, hiding assets overseas, and perjury. Prosecutors alleged that, in exchange for government support for a merger of two Samsung affiliates, Lee paid ₩43 billion to a close friend of then-President Park Geun-hye. He was convicted and initially sentenced to five years in prison, but was released after about a year when the Seoul High Court reduced and suspended his sentence. In August 2022, Lee received a presidential pardon—one that local polls said was supported by about 70% of the Korean public.

If the legal drama is the headline, the mechanics of succession are the real plot.

The transfer from Lee Kun-hee to Lee Jae-yong triggered one of the largest inheritance-tax bills ever seen. The family inherited an estimated 26 trillion won in assets, and under South Korean tax law, they owe roughly 12 trillion won in inheritance taxes. They’re paying it over six years through a government-approved installment plan.

Korea’s inheritance tax is famously steep. On large estates, rates can reach 50%. And if the beneficiary becomes the largest shareholder of a major company, a surcharge can push the effective top rate to around 60%. That turns succession into forced finance: to keep control, you need cash; to get cash, you often need dividends, loans, or share sales.

The schedule makes that pressure real. Lee Jae-yong’s final installment—480 billion won—was due in April 2026. After that final payment, he can begin redirecting more of his dividend income into reinvestment across Samsung affiliates, rather than into the tax bill.

This is where Samsung Life becomes more than an insurer. It’s a succession tool.

Samsung Life’s ownership is deeply tied to the family and the affiliates that support family control: 49% is owned by related shareholders, including 10.4% by Jay Lee, 6.9% and 1.7% by his sisters Boo-Jin and Seo-Hyun, 19.3% by Samsung C&T, 5.9% by E-mart, and 4.7% by the Samsung Foundation of Culture. Those stakes aren’t just wealth—they’re voting power routed through the group’s most important junction points.

And because inheritance taxes require liquidity, the family has had to sell pieces of the empire to keep the rest. In October 2025, Lee Kun-hee’s heirs sold about 1.8 trillion won (about $1.3 billion) worth of Samsung Electronics shares through a block deal to help cover inheritance taxes and loan payments.

For investors, this matters because it changes behavior. Massive tax obligations can drive dividend increases and share sales that wouldn’t otherwise happen. It can also force hard choices about the very structure that made Samsung controllable in the first place. Korea’s governance debate has been asking a single, persistent question: can the cross-shareholding machine survive a generational handoff when the heirs must fund one of the world’s most punishing inheritance-tax regimes?

Samsung Life sits right in the middle of that answer.

VIII. Inflection Point #3: IFRS 17 and K-ICS Revolution (2023-Present)

On January 1, 2023, Korean insurance accounting flipped. In one stroke, the industry moved onto IFRS 17, and at the same time adopted a new solvency regime called the Korean Insurance Capital Standard, or K-ICS. Together, they changed not just how insurers tell their story on paper, but how they manage the business in real life.

Start with K-ICS. It’s a full risk-based capital framework that, in plain English, pushes insurers to value assets and liabilities closer to market reality. For some companies, that meant suddenly confronting risks they’d been able to smooth over for years. For others—especially the biggest, best-capitalized players—it created a more level playing field that rewarded scale, risk management, and deep balance sheets.

IFRS 17 was the other half of the punch. Under the old world, insurers could obscure a lot of volatility through legacy accounting. Under IFRS 17, profitability is meant to be recognized as the insurer actually provides service over time, not simply at the moment a policy is sold. The new centerpiece metric is the Contractual Service Margin, or CSM—basically, profit that’s been earned economically but can’t be booked yet because the insurer still owes years of coverage.

Samsung Life’s transition numbers showed how dramatic this shift could look. Under IFRS 17, it reported year-end equity of KRW 41.6 trillion—about 72% higher than the KRW 24.2 trillion it had previously reported under IFRS 4. On the liability side, a newly visible line item appeared: CSM of KRW 11 trillion at the end of 2022. Samsung Life also disclosed that CSM amortization—amounts released into profit as coverage is delivered—was around KRW 1.1 trillion in 2022.

For Samsung Life, that was the upside case: IFRS 17 should make earnings look steadier and more “managed,” because profit is released systematically rather than whipsawed by short-term noise.

But IFRS 17 also dragged an old fight back into the spotlight: the “deviant accounting” controversy.

Under IFRS 17, expected amounts to be paid to policyholders in the future are supposed to be measured at fair value and reflected as insurance liabilities. Ahead of the transition, Samsung Life asked the Financial Supervisory Service whether it could keep using its long-standing policyholder equity adjustment account—rather than treating those potential obligations to participating policyholders as insurance liabilities under the new standard. The Financial Supervisory Service granted the exception, allowing Samsung Life to continue its prior approach.

That exception mattered because it effectively preserved Samsung Life’s historical treatment: it did not have to recognize the full potential obligation to participating policyholders as an IFRS 17 insurance liability. Critics called that “deviant accounting.” Supporters viewed it as a pragmatic accommodation of a uniquely Korean legacy issue.

Then, in 2025, the politics and the facts on the ground shifted.

The debate heated up after August, when Lee Chan-jin became governor of the FSS and initiated a review of the earlier stance. In a parliamentary audit the following month, Lee signaled a harder line: “Internal coordination has been completed regarding the deviant accounting issue, and we are aligned with the position that it should adhere to international accounting standards.”

And at almost the same time, the structure of the exception ran into a practical test. Samsung Life had applied the “deviation” condition under K-IFRS standards on the assumption that Samsung Electronics and Samsung Fire & Marine Insurance would not sell their shares. But in February 2025, Samsung Life and Samsung Fire & Marine Insurance disposed of approximately KRW 280 billion of Samsung Electronics shares via a block deal, in line with the Financial Industry Restructuring Act. That sale undermined the very premise of the treatment: if the exception assumed affiliate shares wouldn’t be sold, what happens when they are?

So IFRS 17 didn’t just modernize reporting. It reopened a governance argument with real stakes: if the accounting exception was granted under one set of assumptions, and subsequent actions violate those assumptions, should the exception still stand?

Meanwhile, K-ICS was applying pressure from another direction. Regulators moved to ease some stress by lowering the recommended K-ICS capital adequacy ratio from 150% to a range of 130% to 140%. But they also proposed a new constraint: a mandatory requirement for insurers to maintain a core capital solvency ratio above 50%. That’s a split decision—less pressure in one place, more pressure in another. And it doesn’t hit everyone equally. Large insurers can often raise or retain capital more easily; mid-sized and smaller players may struggle to meet stricter core capital thresholds.

For Samsung Life, this new era has been both vindication and vulnerability. Its size and capital strength position it well for a world that rewards disciplined balance sheets. But the same reforms that make the industry more “international” also make it harder to rely on uniquely domestic workarounds—especially when those workarounds touch the most sensitive fault line in the entire story: what’s owed to policyholders, what belongs to shareholders, and what Samsung Life’s stake in Samsung Electronics really represents.

IX. Inflection Point #4: The Samsung Fire Subsidiary Play (2025)

Just as IFRS 17 was making the old ownership-and-accounting debates harder to paper over, Samsung Life made its most consequential structural move in years. In early 2025, it moved to bring Samsung Fire & Marine under its wing as a formal subsidiary.

Samsung Life secured regulatory approval to do it. The company said the Financial Services Commission granted approval on March 19, and it planned to complete the incorporation by the end of the month.

The catalyst wasn’t a sudden love of corporate simplicity. It was a regulatory trap that was starting to close.

Samsung Fire had announced on January 31 that it planned to shrink its treasury shares from 15.93% to below 5% by 2028. That sounds like an internal capital management decision, but mechanically it would have had a side effect: it would raise Samsung Life’s effective ownership stake in Samsung Fire. Analysts estimated that if Samsung Fire reduced its treasury shares to 5%, Samsung Life’s stake would climb to about 16.93%—above the 15% limit set by the Insurance Business Act.

Samsung Life had two basic options. It could sell shares and stay under the cap, or it could change the relationship so the cap problem goes away. Turning Samsung Fire into a subsidiary was the cleaner move—and, just as importantly, it avoided the other risk: selling down ownership in a key affiliate could weaken Samsung Life’s role in Samsung’s governance machinery.

At the same time, the two insurers were also trimming their Samsung Electronics exposure to stay onside with another rule. Samsung Life and Samsung Fire sold a small block of Samsung Electronics shares—together, about 0.08% of the company’s outstanding shares—aligned with the Act on the Structural Improvement of the Financial Industry, which limits financial institutions from holding more than 10% of a non-financial company’s shares. Before those sales, Samsung Life held 8.51% of Samsung Electronics, and Samsung Fire held 1.49%.

Markets like uncertainty until they don’t. Once Samsung Life formally applied for subsidiary affiliation on February 13, the “overhang” cleared—investors could see the path forward. Over the next two trading days, Samsung Life shares rose 15.1%, and Samsung Fire jumped 18.5%.

On paper, Samsung Life insisted this was a structural fix, not a business overhaul. CFO Lee Wan-sam said the incorporation would have limited impact: no change to profits, no change to the capital ratio, and no change in overall business management. But the strategic logic was obvious. With the leading life insurer and the leading nonlife insurer under one roof, Samsung could push cross-selling and reduce duplication as the line between life, health, and general insurance keeps blurring for consumers.

By April 2025, the absorption had taken effect, creating a more integrated financial ecosystem. Samsung Life said consolidation eliminated redundancies and expanded the combined customer base, with cross-selling lifting revenue per user by 8% in Q2.

And then there’s the governance angle—the one that always matters most in this story. The subsidiary structure preserved Samsung Life’s position inside the group’s control architecture. Lee Jae-yong held an 18.9% stake in Samsung C&T; Samsung C&T owned 19.34% of Samsung Life; and Samsung Life sat downstream as the largest shareholder of both Samsung Fire and Samsung Electronics. In that relay race of influence, reducing Samsung Life’s stake in Samsung Fire would have been more than a portfolio decision—it would have been a governance decision.

Even so, Samsung Fire signaled it would keep running as its own ship. CFO Koo Young-min said that even as a subsidiary, there would be no significant changes in business operations or governance. In classic Samsung fashion, the structure changed—without, at least officially, changing how the machine actually ran.

X. Digital Transformation and The Health Pivot

For most of this story, Samsung Life has looked like governance infrastructure: a block of shares, a voting lever, a regulatory chess piece. But while the headlines fixate on cross-holdings and accounting treatment, the company has also been rebuilding the business that produces the premiums in the first place.

By April 2025, Samsung Life had fully digitized its insurance services. The goal was straightforward: take cost out of the system. The company expected the shift to cut administrative expenses by about 15%. Just as importantly, it aimed to make the experience feel modern—using AI-driven underwriting and claims processing to speed up decisions and improve retention.

That matters because the classic life-insurance machine is expensive. It’s built on a large, agent-led distribution model that can be out of sync with what customers now expect: faster onboarding, simpler service, fewer paper processes. Digitizing underwriting, claims, and customer support isn’t just a tech upgrade. It’s a way to preserve service quality while changing the cost structure underneath it.

At the same time, Samsung Life has been changing what it sells.

In 2023, health products made up 37% of its new business CSM. In 2024, that figure rose to 58%—a clear pivot toward higher-margin, protection-oriented products and away from the more commoditized, savings-heavy policies that long defined Korean life insurance.

The logic is hard to miss. Korea is aging, and demand for medical and long-term care coverage is rising with it. Health products generally carry better margins than traditional savings-type life insurance. And compared to plain-vanilla savings policies, health insurance leaves more room for product design, differentiation, and ongoing engagement.

Samsung Life also leaned into ESG messaging as part of the repositioning. In 2024, it launched its ‘Green Future’ portfolio, using sustainability-focused products to stand out in a crowded market and appeal to younger customers and institutions looking for that alignment.

All of this is happening while the competitive landscape keeps shifting. Insurtech startups and tech platforms are pushing into insurance distribution, carving out segments that used to be the exclusive domain of incumbents and their agent networks. In that environment, scale alone isn’t enough. Scale plus real digital capability is what lets a legacy leader defend its position—and keep growing.

Samsung Life’s pitch, in other words, is becoming two stories at once. One is the story we’ve been telling: a corporate keystone inside Korea’s most important chaebol. The other is more operational—and more relevant to how the company performs quarter to quarter: a large insurer using digitization to lower costs, and using a health pivot to improve the quality of new business.

If the demographic and technological currents reshaping Korean insurance keep strengthening, Samsung Life enters that future with real advantages: resources to keep investing in digital, a brand and tech ecosystem that comes with the Samsung name, and a premium base large enough to fund constant iteration.

XI. Playbook: Business and Investing Lessons

Samsung Life’s story isn’t just a Korean corporate drama. It’s also a playbook—one built over seven decades—on how capital, regulation, and governance can compound into real power.

Lesson 1: The Power of Patient Capital

Life insurance is, at its core, a machine for collecting time. Premiums come in today. Claims often go out years, sometimes decades, later. That gap—insurance float—creates patient capital that can be invested with a horizon most industries can’t touch.

Samsung Life put that advantage to work in the 1980s when it used premiums from participating policies to buy shares in Samsung Electronics. Those shares went on to appreciate roughly 85-fold. It’s the cleanest possible illustration of float’s upside: disciplined, long-duration capital funding a long-duration bet. But it also shows the catch. When policyholder money creates enormous unrealized gains, the questions about who ultimately deserves that upside don’t go away—they just wait for the next regulatory or political trigger.

Lesson 2: Regulatory Arbitrage as Competitive Advantage

Samsung Life’s edge has never been purely operational. It’s been structural—and in Korea, structure is inseparable from regulation.

From the government-arranged acquisition of Dongbang in 1963, to the 13-year IPO standoff that dragged on into 2010, to the ongoing “deviant accounting” debate under IFRS 17, Samsung Life repeatedly operated at the boundary line of what rules allowed and what politics would tolerate. That navigation preserved shareholder value and protected the group’s governance architecture—but it also created recurring reputational and regulatory risk.

In regulated industries, regulators aren’t a backdrop. They’re a force on the field. Sometimes they create moats. Sometimes they rewrite the map.

Lesson 3: The Double-Edged Sword of Chaebol Structures

Cross-shareholding is leverage. It’s also exposure.

Samsung Life’s central position in Samsung’s ownership web gives it influence that a pure-play insurer could never replicate. But that same position makes it a lightning rod. Accounting disputes, policyholder activism, and governance reform efforts all find their way back to Samsung Life because it isn’t just an insurer—it’s a control node.

The lesson is simple: structures that amplify control also amplify scrutiny. And when sentiment shifts—politically, socially, or generationally—the very thing that made the machine work can become the thing that puts it at risk.

Lesson 4: Timing Market Transitions

The insurer that wins the next decade in Korea won’t be the one that sells the most traditional savings policies. It’ll be the one that adapts fastest to demographics, technology, and new accounting economics.

Samsung Life’s pivot toward health products and digital distribution is exactly that kind of transition bet: moving from savings-oriented life insurance toward higher-margin health products, while digitizing service and operations to reset the cost base. The results show up in performance: Samsung Life reported a record KRW 2.1 trillion net profit for 2024, up 11.2% year-on-year. As of March 2025, total assets were about $216.7 billion.

The broader takeaway is bigger than Samsung: when a market regime changes, incumbents don’t lose because they’re large. They lose because they stay frozen.

Lesson 5: The Inheritance Tax Chess Game

In Korea, succession isn’t an event. It’s a financing strategy that can shape a conglomerate’s behavior for years.

The Lee family’s inheritance tax bill—around 12 trillion won—has forced asset sales, encouraged dividend flows, and influenced corporate restructurings across the group. For investors, this is not gossip-column material. It’s a real driver of capital allocation and governance decisions, especially in companies like Samsung Life that sit at critical junction points in the ownership network.

In chaebol investing, you’re not just underwriting a business. You’re underwriting a family balance sheet—and the tax code that governs it.

XII. Porter's Five Forces and Hamilton's Seven Powers Analysis

You can tell Samsung Life’s story as politics and governance. You can also tell it the way competitors and regulators experience it: as a business with real structural advantages, operating in a market that’s hard to enter, hard to win, and getting harder to game.

Porter's Five Forces:

1. Threat of New Entrants: LOW

Korean insurance is not a market you casually “enter.” Licensing is strict, capital requirements are heavy, and the bar keeps rising as solvency standards tighten. Bigger incumbents can usually bolster core capital because they have scale, earnings power, and access to funding. Mid-sized and smaller players, meanwhile, can get squeezed by the same rules.

And then there’s distribution. Samsung Life’s roughly 50,000-agent network wasn’t built in a sprint; it took decades. A new entrant can build an app. It can’t build that kind of boots-on-the-ground trust and reach overnight.

2. Bargaining Power of Buyers: MODERATE

For most individual customers, bargaining power is limited. Policies are complicated, comparison-shopping is imperfect, and the biggest insurers set the tone. But not every buyer is a household. Corporate clients and pension funds can negotiate, and digital channels are steadily making pricing and product features easier to compare.

Samsung Life’s scale helps, but it doesn’t give it a free pass. With large rivals like Hanwha Life and Kyobo Life in the ring, the market won’t let anyone push margins too far without consequences.

3. Bargaining Power of Suppliers: LOW

In many industries, suppliers hold the leverage. In life insurance, the insurer often is the leverage—because it controls the capital pool.

Samsung Life’s main supplier relationship is reinsurance: partners that take slices of risk off its balance sheet. But reinsurers, both domestic and global, compete for the business of top-tier insurers. That competition tilts negotiating power toward Samsung Life.

4. Threat of Substitutes: MODERATE-HIGH

The substitute threat is real, and it’s growing. Insurtech platforms and embedded insurance are siphoning off simpler, more standardized products—especially where the purchase can be tucked into another digital journey and priced aggressively.

But “substitution” has limits. Complex life and health coverage still tends to require advice, long-term service, and a level of trust that established insurers have spent decades earning. The new players can nibble at the edges; replacing the core is harder.

5. Industry Rivalry: HIGH

Korea’s life insurance market is a knife fight. Samsung Life, Hanwha Life, and Kyobo Life compete hard for premium income, and the shift to IFRS 17 and K-ICS hasn’t calmed things down—it’s raised the stakes. As everyone pushes toward higher-margin lines, the battle intensifies in health products.

Regulatory capital requirements impose some discipline, because they limit how recklessly insurers can underprice. But within those boundaries, rivalry is still high, and differentiation is increasingly about product mix, underwriting capability, and distribution efficiency.

Hamilton's Seven Powers:

1. Scale Economies: As the country’s largest life insurer, Samsung Life gets scale advantages that show up everywhere: funding technology upgrades, spreading fixed costs across a massive policy base, negotiating reinsurance, and sustaining the marketing that keeps the brand top of mind.

2. Network Effects: There aren’t many pure network effects in life insurance, but Samsung Life benefits from an indirect version: the Samsung name and ecosystem make cross-selling and customer trust easier than they are for stand-alone rivals.

3. Counter-Positioning: The company’s push to digitize isn’t just modernization; it’s a strategic wedge. Competitors that rely more heavily on traditional, agent-centric models can’t pivot as quickly without disrupting how they sell and service policies.

4. Switching Costs: Life insurance is sticky by design. Long-term contracts, surrender charges, and the loss of accumulated value make switching painful. Even if a customer is mildly dissatisfied, inertia often wins.

5. Branding: In financial services, trust is a product. Samsung’s brand—one of the most valuable in Korea—carries over into insurance, lowering customer acquisition friction and reinforcing the sense that the company will still be there decades from now.

6. Cornered Resource: Samsung Life’s 8.5% stake in Samsung Electronics isn’t just valuable—it’s singular. No competitor can replicate that combination of dividend stream and strategic leverage inside Korea’s most important corporate network.

7. Process Power: Underwriting is a game of learning curves and data. Samsung Life’s decades of experience and claims history create actuarial insight that newer entrants can’t quickly match. Its digitization push should compound that advantage by improving how fast and how accurately it can price risk and handle claims over time.

Key Performance Indicators to Track

If you’re tracking Samsung Life as an investment, it helps to focus on a few metrics that cut through the noise. Three, in particular, tell you whether the company is improving the underlying insurance engine while still carrying its unique “Samsung governance” gravity.

1. Contractual Service Margin (CSM) Growth

Under IFRS 17, CSM is the profit Samsung Life expects to earn over time from policies already sold, but hasn’t been allowed to recognize yet. In other words, it’s a forward-looking scoreboard for the quality of new business. By Q3 2025, Samsung Life’s CSM balance had reached KRW 14 trillion, with health CSM up 23.9% year-over-year. The headline number matters, but the mix matters more: the more that growth comes from health rather than legacy savings-type products, the more it signals durable, higher-quality profitability.

2. K-ICS Solvency Ratio

K-ICS is the capital reality check. It measures whether Samsung Life has enough capital to withstand shocks under a risk-based framework. With a solvency ratio of 180%, the company has been operating from a position of strength. But requirements are evolving, and solvency is one of those metrics that can change quickly when rates, spreads, or assumptions move. The key is whether Samsung Life stays comfortably above regulatory minimums and remains strong relative to peers—not just whether it clears the bar.

3. Value of Samsung Electronics Stake vs. Market Capitalization

This is the KPI that only exists because Samsung Life is Samsung Life. The company’s 8.5% stake in Samsung Electronics creates a situation where one investment can be worth more than Samsung Life’s entire market capitalization. Watching how the value of that stake compares to Samsung Life’s market cap is a quick way to see how the market is pricing the business: as a real insurer with operating value, or as a discounted holding vehicle for Samsung Electronics exposure.

Regulatory and Accounting Considerations

For all the talk of product mix, digital claims, and solvency ratios, Samsung Life still carries a set of legal and regulatory overhangs that can matter as much as any quarterly result. These are the issues that can force a rewrite of the balance sheet—or the governance playbook.

The "Deviant Accounting" Resolution

The Financial Services Commission and the Korean Accounting Standards Board planned a joint meeting to decide whether life insurers, including Samsung Life, could keep applying the special accounting treatment tied to participating policies.

If that exception is withdrawn, the shares of participating policyholders would no longer sit in the familiar “policyholder’s equity adjustment” bucket. Instead, they would be treated as capital based on the company’s judgment, and the dividend interests tied to those policies would no longer show up as insurance liabilities.

This is not a cosmetic change. The outcome could move Samsung Life’s reported liabilities, shift capital ratios, and reshape what it ultimately owes participating policyholders. And while management stressed that incorporating Samsung Fire as a subsidiary wouldn’t change the way the group is governed, this older, unresolved question—how to account for and allocate the value created by legacy participating policies—still hangs over everything.

Potential "Samsung Life Law" Legislation

Then there’s the proposal often nicknamed the “Samsung Life Law,” introduced by Assemblyman Cha. The idea is simple, and explosive: require insurers to value affiliate shares at market value rather than acquisition cost, and cap those holdings at 3% of total assets.

Applied to Samsung Life, the implications are immediate. Its stake in Samsung Electronics would be worth more than 40 trillion won, against total assets of 275 trillion won at the end of last year—well beyond what the proposed cap would allow. The practical result would be forced selling: Samsung Life would likely need to unload a meaningful portion of its Samsung Electronics shares, and distribute part of the gains to participating policyholders.

If enacted, this wouldn’t just reshape Samsung Life’s balance sheet. It could tug at the thread that holds Samsung’s governance structure together.

Inheritance Tax Completion

Finally, the succession math is still in motion. Lee Jae-yong’s last inheritance-tax installment—480 billion won—was due in April 2026. Once that final payment is made, he can redirect more of his dividend income toward reinvestment across Samsung affiliates, including Samsung C&T, instead of toward the tax bill.

That shift may sound personal, but it has corporate consequences. The end of the inheritance-tax payment schedule could change the Lee family’s capital-allocation priorities—and, depending on how they fund control and liquidity from here, could also influence Samsung Life’s dividend posture going forward.

Conclusion: The Keystone's Future

Samsung Life Insurance is at another one of those moments where its future won’t be determined by a single product cycle or a single quarter. It’ll be determined by how well it navigates a set of forces that, for most insurers, simply don’t exist.

The arc is almost too neat: a company that began as Dongbang Life—built on door-to-door selling, often by Korean War widows offering families a simple way to save and protect themselves—now sits as Korea’s largest life insurer, with roughly $217 billion in assets. In that sense, Samsung Life’s story tracks Korea’s story: from post-war scarcity to global industrial and technological strength.

But Samsung Life isn’t only an insurer. It’s also one of the most strategically important nodes in Samsung’s ownership architecture. That dual identity—operating company on the surface, control mechanism underneath—creates advantages that pure-play insurers can’t replicate. It also creates complications that pure-play insurers never have to explain.

From here, Samsung Life’s next era will be shaped by a few questions that sit at the intersection of accounting, regulation, technology, and family governance:

Will the “deviant accounting” controversy end with a compromise that preserves Samsung Life’s balance sheet strength, or with a stricter interpretation that forces a restructuring of how legacy value is recorded—and potentially distributed?

Can Samsung Life turn its digital transformation and health-product pivot into durable operating advantage as Korea ages, customer behavior shifts, and new distribution models keep pushing in from the edges?

What changes once the Lee family finishes paying inheritance taxes—does capital allocation become more aggressive, more defensive, or simply freer to reinforce control?

And will proposals like the so-called “Samsung Life Law” redraw the regulatory boundaries in a way that compels forced selling of affiliate stakes, reshaping not just Samsung Life’s portfolio but the governance mechanics of the entire group?

None of these are clean, technical questions. They’re political questions, capital questions, and legitimacy questions. And that’s why Samsung Life remains such a singular asset for investors: it’s a market-leading insurer with real moats, embedded inside one of the world’s most valuable corporate ecosystems—and carrying governance complexity that can create both sharp risk and surprising opportunity.

The keystone is still holding. The question is what it will be asked to support next.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music