WH Group: From Mao-Era Meat Locker to the World's Pork Empire

I. Introduction: The Improbable Rise of Pork's Global Titan

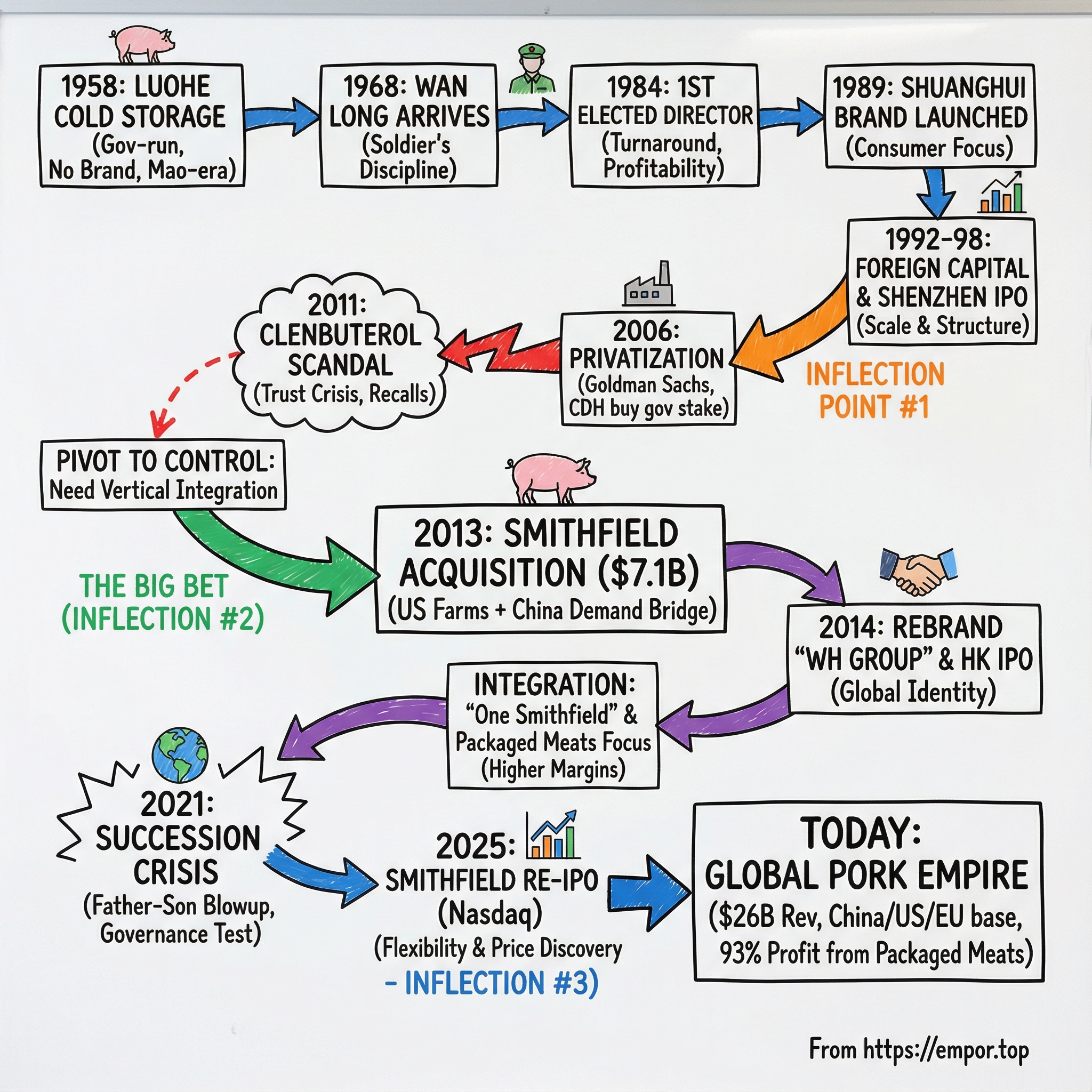

Picture this: it’s 1968. A young Wan Long walks through the gates of a struggling, state-owned meat facility in Luohe, a third-tier city in China’s Henan province. The place is basically cold storage with a slaughter line attached—a leftover of Mao-era central planning. A small number of pigs are processed each day for government distribution. There are no brands. There are no profits. And in a command economy, there isn’t really such a thing as “the customer.”

Now jump to December 2025. Wan Long is the chairman of WH Group, the world’s largest pork company, with major operations across China, the United States, and Europe—including Smithfield Foods in America. His net worth stands at $2.50 billion. The business generates $25.94 billion in annual revenue and sits at the center of a global supply chain that runs from Midwest farms to Chinese dinner tables.

The arc from “meat locker” to global titan is one of the wildest in modern business. Along the way: a democratically elected factory director inside Communist China, early foreign private equity pushing into a newly opening market, a food safety scandal that put the company’s very name at risk, and then the headline act—the largest-ever Chinese acquisition of an American company. Add a bitter father-son blowup that read like Succession, plus a recent return of Smithfield to U.S. public markets, and you’ve got a corporate saga with real stakes.

In 2024, WH Group achieved sales of $25.94 billion, with packaged meats contributing around 53% of revenue and an astonishing 93% of operating profit. That mix is the point. This wasn’t built by winning a commodity knife fight on fresh pork. It was built by climbing the value chain—away from raw slaughter and toward branded, higher-margin products people reach for by name.

Underneath it all is a deceptively simple bet: China eats more pork than anyone on Earth. America produces it more efficiently than anyone on Earth. Bridge those two worlds, and you create a machine. Wan Long wagered his career—and eventually billions—on being the one who could do it. Whether the next chapter belongs to him, to his sons, or to a newly re-listed Smithfield is the question hanging over the empire now.

This is the story of WH Group.

II. Origins: A State-Owned Meat Locker in Communist China (1958–1983)

To understand WH Group, you first have to understand China in 1958. Mao Zedong had just launched the Great Leap Forward—a sweeping attempt to force the country into industrial modernity through collectivization and central planning. Private enterprise was gone. Farming was organized into communes. And meat, for most families, wasn’t an everyday staple. It was a festival food.

That same year, the Luohe municipal government set up what would eventually become WH Group: a single, government-run facility whose earliest incarnation was known as Luohe Cold Storage. This wasn’t a brand. It wasn’t a business in any modern sense. It was infrastructure—part of the state’s system for handling scarce protein.

In 1977, the operation was renamed the Henan Luohe Meat Products Processing United Factory. The new name signaled a shift from simply keeping meat cold to doing more actual processing. But the mission stayed basically the same: pigs came in from local communes, they were slaughtered, the meat went into lockers, and it was distributed according to quotas. No competition. No marketing. No product strategy. Just compliance with the plan.

For the next few decades, the factory muddled along like countless other state-owned enterprises in China’s interior—kept alive because it had a role in the system, not because it was particularly good at what it did. Henan was (and still is) one of China’s most populous provinces, but it wasn’t where the money or the new ideas flowed. Luohe wasn’t Shanghai or Shenzhen. It was a small, inland city—known more for its rail connections than for commerce.

And this is where Wan Long’s story begins.

In 1968, after being demobilized, Wan Long reported to the Luohe Meat Joint Factory, the predecessor of what would become Shuanghui. Like everyone else, he didn’t choose it; he was assigned. He started low in the hierarchy and moved steadily upward—office clerk, then deputy director, then director, then factory deputy director—absorbing the plant’s operations from the inside out.

He also carried something the plant desperately lacked: discipline. Fresh out of the People’s Liberation Army, Wan Long brought a soldier’s instinct for order, accountability, and chain of command—traits that would later harden into his signature management style.

By the early 1980s, though, discipline wasn’t enough. China itself was changing. Mao had died in 1976. Deng Xiaoping’s Reform and Opening Up was beginning to rewrite the rules of the economy. State-owned factories were being granted more autonomy. Markets—carefully, unevenly—were being allowed to exist.

For Luohe’s meat plant, that was both an opportunity and a threat. In a planned economy, you could survive forever by being “needed.” In a market economy, you had to be wanted. The factory had no brands, no track record of competing, and no muscle memory for serving consumers.

So the question became brutally simple: when China changed, could this place change with it?

The answer would come down to leadership. And in 1984, the workers would make a choice that was almost unthinkable in Communist China.

III. Wan Long Takes the Helm: China's First Democratically Elected Factory Director (1984–1991)

By 1984, China was in motion. Deng Xiaoping’s reforms were picking up speed, and the Party had begun using a new phrase—“socialist commodity economy”—to describe what was happening. It sounded ideological. In practice, it meant state-owned factories were being told, for the first time, to act a little more like businesses.

Inside the Luohe Meat Joint Factory, that shift produced a moment that still feels almost impossible in context: the workers voted for their leader. And in 1984, Wan Long became the factory’s first democratically elected director.

Let that land. In Communist China—where the Party appointed leaders and controlled outcomes—rank-and-file employees chose the person who would run their plant. It wasn’t a referendum on democracy; it was an experiment in performance. The factory needed someone who could make it work.

They picked Wan Long: 44 years old, a military veteran, and a company lifer who’d spent sixteen years learning every corner of the operation. What the workers saw in him wasn’t charm or politics. It was resolve. A manager who would set standards, enforce them, and do whatever it took to get the factory out of survival mode.

The turnaround came fast. In his first year, Wan Long took the business from a net loss to a net profit of 5 million yuan ($1.7 million)—a result that was essentially unheard of for a lumbering, state-run processor.

A big part of the change was discipline. Wan Long ran the plant like a unit: strict work routines, zero tolerance for lateness, and rules that actually meant something. He didn’t drink or smoke, didn’t waste time cultivating hobbies, and he didn’t soften hard feedback to spare feelings. He spoke plainly, even when it made people uncomfortable.

But the deeper advantage wasn’t toughness. It was timing—and vision.

Wan Long could see what was happening in the global meat industry: livestock production was consolidating, and the real money was shifting from basic slaughter into processing, distribution, and branded products. China, by contrast, was still largely stuck at the commodity end of the chain. Compared with developed countries, processed meat made up a far smaller share of overall meat production. To Wan Long, that gap wasn’t a weakness. It was the opening.

He pushed to enhance technology, focus on products, and modernize what had been a traditional, low-value business. Through the late 1980s, the factory kept getting sharper: higher efficiency, less waste, and a workforce newly motivated by the idea that performance could change outcomes.

Still, Wan Long knew operational improvement alone wouldn’t build an empire. To truly transform the plant, he needed something China’s state-owned meat industry essentially didn’t have at the time: a brand.

IV. The Shuanghui Brand & International Partnerships (1989–1998)

By 1989, Wan Long did something that still sounds obvious today, but was close to radical back then: he launched a brand. Shuanghui.

The name means “Double Confluence,” a nod to the two rivers that meet in Luohe. And over time, it would become one of the most recognizable labels in Chinese processed meat. But in 1989, the idea that a state-owned meat factory should build a consumer brand was a break from the old model. For decades, most people didn’t “choose” meat products. They took what was available through the system.

Wan Long saw the ground shifting. In the early 1990s, China’s retail world started to open up—private markets spread, supermarkets began appearing in big cities, and consumers got something new: options. In that environment, familiarity and trust suddenly mattered. A brand wasn’t decoration. It was a moat.

Then came 1992, and Shuanghui pushed harder into packaged products. That year, the company introduced its first branded meat product to the market in February. Sausage sales took off, and the momentum helped unlock something even more important than volume: outside capital. Later in 1992, Shuanghui formed a joint venture with 16 institutional investors from six countries, creating Shuanghui International.

For a provincial Chinese meat processor, foreign investors weren’t just a source of money. They were a signal. Validation that this wasn’t another lumbering state enterprise living off quotas and protection, but a company trying to operate like a modern consumer business—with standards, growth plans, and a real strategy.

In 1994, that venture was consolidated as Shuanghui Group. And in 1998, the company took a step that cemented its transformation from local plant to national player: a Shuanghui subsidiary, Henan Shuanghui Investment & Development Company Limited, was established and listed on the Shenzhen Stock Exchange.

Public markets gave Wan Long something he’d never had in the Mao-era factory days: access to scale capital. It also came with a lasting complication. The corporate structure that emerged was layered and, in practice, pretty intricate: Shuanghui Group as the operating business, Shuanghui International as an offshore holding vehicle, and Henan Shuanghui Investment & Development as the onshore, publicly listed arm. That complexity would matter later—because it made deals easier to finance, easier to restructure, and easier to globalize.

By the end of the 1990s, Shuanghui had become the default name in Chinese processed meat—especially sausages, which were showing up everywhere from supermarkets to convenience stores. The company was no longer just surviving reform-era China; it was starting to define what “modern meat” looked like inside it.

And Wan Long wasn’t done. Because a dominant domestic brand was one thing. Building a supply chain and an empire that could match China’s appetite for pork—that would require bigger partners, deeper pockets, and a willingness to play on a global stage.

V. Inflection Point #1: Goldman Sachs & CDH Investments (2006)

By 2006, China’s reform era had matured into something new: not just factories getting autonomy, but real ownership changing hands. Foreign private equity was flooding in, hunting for companies that could become national champions. Local governments, meanwhile, were looking for ways to offload old state assets, “modernize” them, and tap global capital.

Shuanghui was exactly the kind of prize everyone wanted.

That year, the Luohe government sold its stake in Shuanghui to a joint venture led by Goldman Sachs and the private equity firm CDH Investments. A group of investors paid $250 million to take the government-owned meat processor private—ending an ownership chapter that had begun back in 1958, when the plant was basically municipal infrastructure.

Goldman Sachs later sold most of its position, reportedly for a large profit, but still held 5.2% as of May 2013.

This wasn’t just a new cap table. It was a new operating reality. The Luohe municipal government—the original owner, the implicit backstop, the old source of protection—was stepping away. In its place came investors who thought in terms of governance, control, and exit timelines, and who were comfortable using complex structures to get what they wanted.

The ownership model that emerged was intentionally intricate. Shuanghui’s management held 36% of the equity, and those shares carried greater voting rights than the rest. CDH became another major holder at 34%. Goldman sat at 5%, alongside New Horizon (5%), and Temasek, Singapore’s sovereign wealth fund (3%).

Each name brought something different. CDH wasn’t a random local fund; it had been spun out of China International Capital Corporation (CICC), the country’s premier investment bank, founded as a joint venture with Morgan Stanley. Goldman brought Wall Street’s deal machine—and had done other China bets with CDH, including Yurun Group and Focus Media. New Horizon added a powerful political linkage: it was founded by Wen Yunsong, the son of then-Premier Wen Jiabao. Temasek brought a regional, global-operator perspective.

If the structure felt “Byzantine,” that was the point. In China, “private” doesn’t always mean disconnected from the state. These arrangements often blended commercial capital, management control, and political alignment into one package—designed to be investable, defensible, and expandable.

In October 2007, Wan Long was appointed chairman.

And with new capital came new ambition. The plan wasn’t to simply ride China’s rising pork consumption. The plan was to build something bigger—something global. But before that dream could be executed, Shuanghui would run headfirst into a crisis that threatened the one asset it couldn’t afford to lose: consumer trust.

The 2006 deal, though, was the enabling move. Without the money, the connections, and the financial engineering capability that came with Goldman Sachs and CDH, the company’s later leap—seven years later, across the Pacific, into Smithfield—would have been close to impossible.

VI. Crisis & Redemption: The 2011 Clenbuterol Scandal

By 2011, Shuanghui looked unstoppable. It dominated China’s processed meat market, its products were everywhere, and its new private equity owners were lining it up for an even bigger act: global expansion.

Then March hit—and the bottom fell out.

On March 15, China Central Television (CCTV) reported that pork sold under the Shuanghui name contained clenbuterol, an illegal additive sometimes used to make pigs grow leaner and heavier. In the trade, it was known as “lean meat powder.” For farmers paid by weight, it was a cheat code. For consumers, it was something else entirely.

Clenbuterol is banned for a reason. People who consume it can suffer nausea and dizziness, along with symptoms like increased heart rate, muscular tremors, headaches, fever, chills, and more. The public reaction wasn’t subtle—it was fear, anger, and a sense of betrayal aimed squarely at the country’s biggest meat brand.

And the scale was brutal. Reports indicated more than 1,700 people fell ill and one person died.

The response cascaded fast. Supermarkets across China rushed to pull anything with the Shuanghui label. The company said it would destroy 3,768 tons of potentially tainted products. By March 21, around 2,000 tons of pork and pork products had been recalled, and more than two dozen people connected to the case were fired or suspended.

Wan Long, now the chairman, admitted the damage was real—Shuanghui’s image had been “seriously damaged”—but argued it was an isolated incident. The market didn’t buy the reassurance, because the scandal wasn’t just about one bad batch. It pointed to something structural.

Shuanghui was enormous. Across 13 facilities, it produced more than 2.7 million tons of meat per year. It slaughtered more than 15 million pigs annually—but raised only about 400,000 itself. The rest came from outside suppliers.

That’s the hidden weakness of China’s hog industry: it’s fragmented, dispersed, and full of small independent farms where oversight is uneven and incentives can run the wrong direction. If you buy from thousands of suppliers, quality control becomes less a system and more a hope.

Authorities moved hard. By April 8, 95 people in central Henan—Shuanghui’s home province—had been taken into police custody for allegedly producing, selling, or using clenbuterol. Courts handed down severe sentences, including a suspended death penalty for Liu Xiang, identified as a clenbuterol producer in Hubei province. Other principal offenders received sentences ranging from 14 years to life.

For Shuanghui, the commercial impact was catastrophic. Meat product sales were suspended, and the company said losses could reach as high as 20 billion yuan.

But this is where the story turns—because the scandal didn’t kill Shuanghui’s global ambitions. It sharpened them.

Wan Long and his investors came to a grim conclusion: the brand could be repaired, the factories could be cleaned up, but the real vulnerability was upstream. If Shuanghui couldn’t trust the farms, it couldn’t fully trust its own product. One obvious fix was to raise more pigs itself. After 2011, Shuanghui did want to expand company-owned hog production—but hog farming is capital-intensive, risky, and slow to scale. And local politics made it harder: many local governments welcomed Shuanghui’s logistics and processing footprint, but resisted the plan to build new hog farms.

So Wan Long started looking for a different answer—one that already existed at industrial scale. Thousands of miles away, in the American heartland, a company called Smithfield Foods had spent decades building the kind of vertically integrated operation Shuanghui suddenly craved: tight supply-chain control, mature regulation, and a food-safety culture that could help restore trust.

And once you see that, the Smithfield deal stops looking like a splashy overseas trophy. It starts to look like the most practical response imaginable to the worst crisis Shuanghui had ever faced.

VII. Inflection Point #2: The Smithfield Acquisition—David Buys Goliath (2013)

The deal that would reshape the global pork industry didn’t start with a press release. It started with years of quiet conversations. Shuanghui and Smithfield negotiated for four years before they finally put a number on the table.

In May 2013, Shuanghui announced it would buy Smithfield Foods for $34 per share—about $4.72 billion in equity value. Add in Smithfield’s debt, and the total deal value came to roughly $7.1 billion. Shuanghui was offering a hefty premium to get it done.

The strategic logic was almost too clean. Since 2008, China had been a net importer of pork. As incomes rose, pork consumption climbed with them, but China’s production capacity and safety record couldn’t keep up—especially after scandals like clenbuterol made consumers question the entire domestic supply chain.

Smithfield sat on the other side of that imbalance. Founded in 1936 as the Smithfield Packing Company by Joseph W. Luter and his son, it grew into the world’s largest pig and pork producer. It owned more than 500 farms in the U.S., and it also relied on a network of roughly 2,000 independent contract farms to raise its pigs. This was industrial-scale pork, built for consistency.

The company’s own history had the same kind of gritty, operator-driven arc that made Shuanghui’s story feel familiar. The Luters started with $10,000 raised from local investors, opening across the street from competitor Gwaltney. Decades later, Smithfield hit trouble. In April 1975, at the recommendation of its banks, it brought back Joseph W. Luter III as CEO. By his account, the company had a net worth under $1 million, around $17 million in debt, and was losing $2 million a year—so badly run it even lost money during December holiday ham season, which he said was “like Budweiser losing money in July.” Luter’s restructuring is credited with turning performance around. He stayed CEO until 2006 and chairman until the 2013 sale.

By 2013, Smithfield represented what Shuanghui urgently needed: end-to-end control, under the tight oversight of the USDA, inside a system that global consumers associated with rigorous regulation. And the asset footprint was massive. Through the acquisition, WH Group would gain control of Smithfield’s 146,000 acres of land—making the Henan-based company one of the largest overseas owners of American farmland.

It was also politically radioactive. The transaction became the largest-ever takeover of a U.S. company by a Chinese company, and Smithfield would stop trading publicly once the deal closed. In Washington, suspicion came quickly.

On July 10, 2013, the U.S. Senate Committee on Agriculture, Nutrition and Forestry held an unprecedented hearing on the proposed acquisition. Eleven senators raised alarms. Critics pointed to a long list of potential risks: the prospect of Chinese government involvement or control over Shuanghui; China’s broader effort to acquire strategic assets in the United States; fears that production could shift to China; concerns about more Chinese exports entering the U.S.; prior Chinese food safety violations; and the possibility of losing Smithfield technology and intellectual property.

Despite the noise, in September 2013, CFIUS approved the purchase.

Why did it clear when the opposition was so loud? A few things mattered.

First, Smithfield’s investors wanted the deal. Shareholders voted overwhelmingly in favor—more than 96% of votes cast supported it.

Second, Shuanghui framed the combination in a way designed to lower the temperature. Smithfield CEO Larry Pope said the transaction would “preserve the same old Smithfield, only with more opportunities and new markets and new frontiers.” He also drew a bright line: there would be no importing Chinese pork into the United States. Shuanghui’s interest was in exporting American pork outward.

Third—and this was decisive—the deal didn’t fit the classic national security profile. This wasn’t defense, semiconductors, or telecom infrastructure. It was food processing.

The premium Shuanghui paid captured both the strategic upside and the sheer difficulty of getting a deal like this across the finish line. Some argued Shuanghui overpaid. Others saw it as the only price that bought something truly transformative: a world-class supply chain, a trusted platform, and a bridge straight into the U.S. protein system.

For Wan Long, it was the culmination of a lifetime’s climb. The clerk from a provincial meat locker wasn’t just running a successful Chinese company anymore. He was now chairman of a global pork empire—built, in one audacious move, on American farms and Chinese demand.

VIII. The WH Group Rebrand & Hong Kong IPO (2014)

With Smithfield in the fold, Shuanghui’s next move was about identity—and money. If you were going to run a pork business that spanned continents, you couldn’t keep presenting yourself like a provincial Chinese processor. And if you were going to finance that empire, you needed access to global capital markets.

So in January 2014, Shuanghui International changed its name to WH Group. The operating company in China didn’t abandon what it had built—Henan Shuanghui Investment & Development Company kept the Shuanghui brand—but the parent company adopted something intentionally broader. The new name came from “Wanzhou Holdings,” with the Chinese characters “wan” and “zhou” connoting eternity and continents. Even the logo leaned into the same message, meant to evoke the world’s seas and continents.

The point was simple: this was no longer just Shuanghui. It was supposed to read as global—clean, neutral, and flexible. “WH Group” didn’t tie the company to Luohe, Henan, or even China. It was a blank slate for an international future.

Then came the reality check: turning the Smithfield splash into a public-market victory wasn’t going to be automatic.

WH Group’s first attempt to go public in Hong Kong, in April 2014, quickly ran into trouble. The company had initially aimed for an offering of up to $5.3 billion—positioning it as Hong Kong’s biggest listing in four years—but market volatility and a valuation investors considered too rich cooled demand. The process stumbled out of the gate without any cornerstone investors, the kind that usually anchor large Asian IPOs and signal confidence to everyone else. An unusually wide indicative price range followed, which bookbuilding sources attributed to volatile markets—but it also revealed something more basic: investors weren’t sure how to value this newly assembled, cross-border meat empire.

In the end, the April IPO was scrapped. The reasons were straightforward: choppy markets, aggressive pricing expectations, and skepticism about the integration story the company was selling.

WH Group didn’t wait long to take another swing. Three months later, it returned—scaled down, priced to clear, and focused on the practical goal: raising cash to help pay down the debt taken on to buy Smithfield. On August 5, 2014, WH Group successfully listed on the Hong Kong Stock Exchange (stock code 288), with estimated net proceeds of as much as HK$15.3 billion (US$1.9 billion) from the global offering. The second attempt worked—but at a much lower valuation than originally hoped. The IPO raised about $2 billion, less than half the initial target, but it got the job done.

And over time, the market did grant WH Group a measure of legitimacy. On September 4, 2017, it was formally included in the Hang Seng Index—a milestone that signaled it had become part of Hong Kong’s core roster of major listed companies. For investors, that listing brought something the old, private and complex structure never could: liquidity, a clearer window into the business, and a public-market stamp that this sprawling pork empire was now built to last.

IX. Post-Acquisition Integration: Making Smithfield Work

The real test of a deal like Smithfield isn’t the day the signatures dry. It’s whether the combined company actually works a few years later—on the factory floor, in the org chart, and on the income statement. On that front, WH Group’s execution has been stronger than almost anyone expected.

Start with the fear that dominated the U.S. political debate in 2013: American jobs would vanish. Instead, not a single job left the United States because of the acquisition. In fact, thousands of jobs were added after the deal closed.

That outcome matters because it’s the exact opposite of the popular narrative at the time—that Chinese ownership would hollow out Smithfield, move production overseas, and shrink the workforce. None of that happened.

Inside Smithfield, the bigger shift was structural. For decades, Smithfield had accumulated businesses and let them run as largely independent operating companies. That can work while you’re in acquisition mode, but it’s messy when you want to act like one brand, one system, one company. So in 2015, Smithfield launched the “One Smithfield” initiative, an internal push to unify operations, brands, and employees under a single corporate umbrella. In 2017, CEO Ken Sullivan described the direction plainly: he saw Smithfield’s future as a “consumer-packaged goods business.”

That wasn’t just messaging. It was a deliberate move away from the low-margin commodity grind of fresh pork and toward the steadier economics of branded packaged meats. Since 2014, the Packaged Meats segment became central to Smithfield’s growth strategy—and a major driver of the business’s transformation over time.

And the results showed up in the numbers that matter. Since the last time Smithfield was public in 2013, it grew sales to $14.6 billion while significantly improving profitability and its leverage position.

What about the strategic promise that helped justify the whole acquisition in the first place: exporting American pork into China? That opportunity did materialize, though not quite with the straight-line trajectory people imagined in 2013. The big accelerant turned out to be crisis. After African Swine Fever devastated China’s hog population in 2018 and 2019, U.S. pork exports to China surged.

Even so, China is still a relatively small share of Smithfield’s top line. Exports to China account for roughly 3% of Smithfield’s annual sales, which totaled $14.1 billion at the end of 2024. That might sound minor, but it’s meaningful—and especially valuable because export cuts tend to command premium pricing.

Just as important: the integration avoided the cultural collision many expected. American management stayed in place. Headquarters remained in Smithfield, Virginia. The USDA continued regulating U.S. operations the same way it always had. Day to day, on the ground, Chinese ownership was mostly invisible—which, in this business, is exactly how you want it.

X. The Succession Crisis: A Chinese Family Drama (2021)

Every empire eventually runs into the same problem: the founder can’t run it forever. At WH Group, that question didn’t get answered in a boardroom with a smooth handoff. It exploded into public view in 2021—and it played out like tabloid drama wrapped around a global public company.

WH Group—the world’s largest pork processor and the owner of Smithfield Foods—was suddenly consumed by a family feud at the very top. The fight was between Wan Long, the 81-year-old founder known in China as “No. 1 butcher,” and his eldest son, Wan Hongjian, 52, who had long been seen as the obvious successor. In a matter of weeks, a private disagreement became a public crisis that spooked investors around the world.

It started in June. WH Group announced that it had fired Wan Hongjian, who was then an executive director and vice chairman. In a June 17 filing to the Hong Kong Stock Exchange, the company said he had engaged in “aggressive behaviors against the company’s properties,” and it stripped him of all roles.

Behind that antiseptic language was a scene that felt almost impossible for a Hong Kong-listed multinational: reports of a bitter argument over a senior management appointment, escalating until Wan Hongjian had to be restrained by bodyguards. Photos of his bloodied face then spread across Chinese social media.

Wan Hongjian later told Chinese media that he was enraged by a “particular managerial choice” made by his father at a meeting in Hong Kong. He said he lost control, became violent, and was subdued in the office.

But the firing wasn’t the end of the story. It was the opening act.

On Aug. 17, Wan Hongjian published an article through a pork industry media outlet that leveled sweeping allegations against WH Group and Wan Long. He claimed the 2013 acquisition of Smithfield was aimed largely at helping Wan Long and other executives move money out of China. He also alleged years of tax evasion and business mismanagement, and argued that the incoming chief executive was unqualified to take over.

Public markets reacted immediately. WH Group’s shares in Hong Kong plunged about 17% over two days to their lowest level in almost three years, and Henan Shuanghui Investment & Development Co., the mainland-listed unit, also fell. On August 19 alone, WH Group’s stock dropped 11.3%—its biggest one-day decline since late March—wiping roughly HK$11.2 billion (about US$1.43 billion) off its Hong Kong market value.

WH Group flatly denied the accusations, calling them “untrue and misleading,” and said it reserved the right to pursue legal action against the younger Wan and anyone else responsible.

Then came the reshuffle. Wan Long resigned as chief executive officer. His youngest son, Wan Hongwei, was appointed deputy chairman. Wan Long stayed on as chairman and executive director, while Guo Lijun, the former chief financial officer, became CEO.

The outcome left Wan Long in a smaller—but still decisive—role. At 81, he remained the strategic authority, while day-to-day control moved to professional management. Wan Hongwei was elevated as a potential future leader, but without the clear “heir apparent” status his older brother had carried.

For investors, the episode was a governance stress test, and it exposed the soft underbelly of founder-led conglomerates: concentrated power, opaque succession planning, and family dynamics that can spill directly into public-company reality. In a business built on operational discipline and food-safety trust, WH Group was suddenly forced to manage a different kind of risk—one that no supply chain can hedge.

XI. Inflection Point #3: The Smithfield Re-IPO (2025)

Twelve years after taking Smithfield private, WH Group decided to send its crown jewel back to public markets.

After several quarters of income declines and mounting market pressure, WH Group said it would spin off Smithfield’s U.S. and Mexico operations. The structure mattered: even with a separate listing, WH Group planned to retain control once everything settled.

On January 28, 2025, Smithfield shares began trading on the Nasdaq Global Select Market under the ticker symbol “SFD.” The company priced an underwritten IPO of 26,086,958 shares at $20.00 per share.

That price was the market’s way of signaling caution. Smithfield raised about $522 million—well below what it had been aiming for. Earlier filings had sketched a larger offering: 34.8 million shares, priced between $23 and $27, which would have raised up to about $939.6 million. Instead, Smithfield got the deal done, but at a discount.

Still, the listing was meaningful. Alex Frederick, an emerging technology analyst at Pitchbook, called it a “significant milestone in the food industry,” arguing it would give Smithfield more financial flexibility and direct access to capital as it invests and expands. In his view, the IPO positioned Smithfield to push innovation in pork and sharpen its competitive edge in both U.S. and international markets.

Ownership, however, made clear this wasn’t a full separation. The IPO, combined with 19.5 million shares released September 3–4, represented roughly an 11.5% stake in Smithfield. WH Group remained the “beneficial owner” of about 88% of Smithfield’s more than 393 million total shares.

The obvious question was why now. Why re-list Smithfield after spending a decade integrating it? A few forces appeared to be driving the decision.

First: geopolitics. Since the 2013 acquisition, WH Group had become one of the largest overseas owners of U.S. farmland through Smithfield’s footprint. As U.S.–China tensions intensified, lawmakers increasingly focused on restricting farmland ownership by entities associated with China. In filings, WH Group said spinning off the U.S. and Mexico businesses would improve Smithfield’s “market reputation and credibility” by increasing transparency for U.S. investors. Smithfield also carved out its European operations ahead of the proposed listing.

Second: capital-market flexibility. A separately listed Smithfield could raise money in the U.S. on its own timetable, rather than relying on the balance sheet and priorities of its Hong Kong–listed parent.

Third: price discovery. Since 2013, there hadn’t been a clean, public-market valuation for Smithfield. The re-IPO created one—useful for investors, and useful for WH Group itself as it decided where to invest, how to allocate capital, and what each part of the empire was truly worth.

XII. The Business Today: Understanding the Empire

If the Smithfield re-IPO was about creating separation and clarity, the business itself is still one integrated idea: a global pork platform built on local scale. WH Group now runs a three-continent operation where each region plays a different role—different consumers, different regulations, different economics—but the pieces reinforce each other.

At the ground level, WH Group is in the unglamorous, end-to-end work of feeding people. It produces and sells low-temperature and high-temperature meat products; raises hogs; slaughters and sells fresh and frozen pork; operates poultry slaughtering and production; and runs the less visible but crucial support layer, including logistics and supply-chain management.

After the 2025 Smithfield IPO and the 2024 European carve-out, the empire is easiest to understand as three geographic units:

China Operations (Henan Shuanghui Investment & Development): This is the original engine, listed on the Shenzhen Stock Exchange, and still a heavyweight in Chinese processed meats. Shuanghui operates 13 facilities producing more than 2.7 million tons of meat per year. It slaughters more than 15 million pigs annually, but raises only about 400,000 itself—meaning most of its supply still comes from outside producers.

U.S./Mexico Operations (Smithfield Foods): Now publicly traded again on Nasdaq under ticker SFD, this unit includes Smithfield’s U.S. business and its Mexico operations. The supply chain is built around a mix of company-owned farms, contract farms, and long-term relationships with more than 4,000 independent U.S. family farms that meet Smithfield’s animal care and quality standards.

European Operations: In August 2024, Smithfield’s European operations were carved out and transferred to WH Group. These assets include operations in Poland, Romania, and other European markets.

Zoom in on Smithfield for a second, because it shows the model in numbers. In fiscal year 2024, Smithfield’s segments generated about $14.1 billion in total net sales, and Packaged Meats was the largest piece—$8.3 billion, or 59% of sales.

That mix is the key to understanding WH Group’s economics. Packaged meats are where the durability lives: higher margins, steadier demand, and brands that actually mean something to consumers. Fresh pork, by comparison, is the grinder—more cyclical, more commodity-like, and far more exposed to swings in hog prices.

Those brands are the company’s real shelf-space weapon. As of July 2017, the lineup included Armour, Berlinki, Carando, Cook's, Curly's, Eckrich, Farmland, Gwaltney, Healthy Ones, John Morrell, Krakus, Kretschmar, Margherita, Morliny, Nathan's Famous, and Smithfield.

Put it together, and you get a portfolio where each label has its own positioning and customer loyalty—giving WH Group more leverage with retailers, and more ability to hold price, than a pure commodity meat producer could ever dream of.

XIII. Porter's 5 Forces & Hamilton's 7 Powers Analysis

To understand WH Group’s competitive position, it helps to step back from the headlines and look at the structure of the industry—and what, if anything, can actually create durable advantage in a business as physical, regulated, and commodity-exposed as pork.

Porter's Five Forces Analysis:

Threat of New Entrants: LOW

Getting into “big pork” isn’t like launching a new snack brand. The barriers are punishing: you need massive capital to build or buy farms, feed systems, slaughter capacity, processing plants, cold-chain logistics, and distribution. Then you need the operating know-how—and the regulatory approvals—that take years to earn and even longer to master. Smithfield’s model shows what that scale looks like in practice: highly industrialized production, including large concentrated animal feeding operations, and tight control from early-stage animal development through packing. By 2006, Smithfield was raising around 15 million pigs a year and processing about 27 million—numbers that make clear how far behind a new entrant would start.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers: MODERATE

This is one of WH Group’s persistent pressure points, especially in China. Shuanghui slaughters more than 15 million pigs a year but raises only about 400,000 itself, meaning it still relies heavily on outside farms for supply. That creates risk: quality control, pricing, and supply stability can all wobble. The counterweight is fragmentation. With thousands of independent producers, no single supplier typically has meaningful leverage—but collectively, the supplier base can still squeeze margins when hog cycles turn.

Bargaining Power of Buyers: MODERATE-HIGH

On the other end of the chain, retail consolidation has shifted power toward giants like Walmart and Costco. Big customers can demand lower prices, better terms, and consistent service—and they have the shelf space to enforce it. WH Group’s defense is what it has spent decades building: brands and breadth. When your portfolio is a basket of products shoppers expect to see, you’re harder to swap out than a no-name commodity supplier.

Threat of Substitutes: MODERATE-HIGH

Pork doesn’t compete in a vacuum. It fights for the protein slot against chicken, beef, and increasingly plant-based alternatives. In many markets, chicken is the cheaper default; beef is often the “premium” choice. And over the long haul, changing consumer preferences—especially among younger, more health- and climate-conscious buyers—create a slow, steady headwind for the entire meat category.

Competitive Rivalry: HIGH

This is a knife fight. WH Group goes up against deep-pocketed, operationally sophisticated rivals—Tyson Foods, Hormel, and JBS in the U.S., plus major regional competitors across China and Europe. In commodity cuts, price competition is relentless. The only real escape hatch is branded packaged meat, where differentiation and shelf presence can soften the blows.

Hamilton's 7 Powers Analysis:

Scale Economies: STRONG

As the world’s largest pork producer, WH Group benefits from scale in procurement, production efficiency, logistics, and distribution. When you can spread fixed costs across more volume, you can operate at unit economics that smaller players struggle to match.

Network Effects: LIMITED

There’s no meaningful demand-side flywheel here. Pork doesn’t get more valuable because more people are buying pork from the same producer. This is not a platform business.

Counter-Positioning: STRONG (historically)

The Smithfield acquisition is the clearest example. The China-to-America “reverse integration” thesis wasn’t just hard—it was institutionally awkward for Western incumbents. Replicating it would have meant taking on political scrutiny, cross-border risk, and a strategy that didn’t fit how U.S. and European meat companies traditionally grew. WH Group could do it precisely because it came from the other side of the demand equation.

Switching Costs: LOW

For most consumers, switching from one pork brand to another is as easy as grabbing what’s on sale. The same is true for many B2B customers in food service. That low friction is a structural weakness—and it’s why the company fights so hard to build brand habit inside packaged meats.

Branding: MODERATE

WH Group has real brands: Shuanghui in China, plus Smithfield and its U.S. portfolio. Those names help with retailer relationships and can support some pricing power. But pork is still commoditized at the category level, which caps how much premium branding can reliably command.

Cornered Resource: MODERATE

Smithfield’s footprint matters. The 146,000 acres of land WH Group acquired through the deal made it one of the largest overseas owners of American farmland. Pair that with established supplier relationships and decades of accumulated institutional know-how, and you have assets that are difficult—sometimes impossible—for competitors to replicate quickly.

Process Power: STRONG

This is where execution becomes an advantage. The “One Smithfield” initiative is process power in action: unifying operations, brands, and teams; extracting synergies; and improving profitability through disciplined cost management and stronger balance-sheet control. In a business where rivals often have similar inputs, better processes can be the difference between thriving and merely surviving a down cycle.

Key Performance Indicators to Track:

For anyone watching WH Group, three KPIs tell you whether the strategy is working:

-

Packaged Meats Operating Margin: This is the profit engine. Margin trends here show whether WH Group is truly building a durable, higher-quality earnings base beyond commodity pork.

-

China Fresh Pork Pricing vs. Cost: The China business is still exposed to hog cycles. The spread between what the company sells pork for and what it pays to produce or procure it largely determines profitability in this segment.

-

U.S. Export Volumes to China: The Smithfield deal was built on the idea of connecting American supply to Chinese demand. Export volumes are a direct read on how much of that original thesis is actually showing up in the real world.

XIV. Investment Considerations: Bull and Bear Cases

The Bull Case:

The bull case for WH Group starts with something simple: position. This company sits on top of the two most important pork markets on the planet—China and the United States—with leading franchises that were built over decades and would be brutally hard to replicate from scratch.

The second pillar is mix. WH Group has been steadily pushing the business toward packaged meats, where brands matter and margins are structurally better than the commodity grind of fresh pork. When that shift works, it doesn’t just add growth—it changes the quality of earnings.

And then there’s the demand backdrop. Even with plenty of short-term volatility, the long-term story in China has still been rising incomes and rising protein consumption. Pork is the center of that plate.

You can see all three themes in the company’s 2024 results. Revenue dipped slightly to $25.94 billion, but operating profit jumped to $2.4 billion, and profit attributable to owners rose sharply before biological fair value adjustments. In other words: the top line didn’t do much, but the machine got meaningfully more profitable—exactly what you’d expect if the company is climbing the value chain.

Finally, the Smithfield re-IPO adds a potential unlock. A separately traded U.S. listing gives Smithfield more direct access to American capital markets—and gives WH Group a clearer, more transparent valuation benchmark for its most important overseas asset. In a world where geopolitics can distort perception, transparency can be an asset in its own right.

The Bear Case:

The bear case begins where many China-linked multinationals stumble: governance. The Wan family blowup didn’t just create headlines—it exposed how much of WH Group’s authority still runs through one person. Wan Long, now 84, remains Chairman and Executive Director. Investors are left with the same unresolved question: what does leadership look like when the founder is no longer there to impose discipline?

Next is geopolitics, which is intensifying, not fading. Trump trade adviser Peter Navarro highlighted Smithfield after its purchase by WH Group, arguing that it “now basically controls an eighth of the world’s pork supply.” Whether or not you agree with that framing, the takeaway is the same: Chinese ownership of a major U.S. food asset remains a political flashpoint, and Congressional scrutiny could rise regardless of how Smithfield is listed.

Third, the industry itself has real secular pressure. Meat faces growing competition from alternative proteins, and industrial hog farming faces mounting environmental and social scrutiny. These aren’t WH Group-specific problems—but they can compress valuations, raise costs, and narrow strategic options across the whole sector.

And then there’s competition, especially in China’s packaged meats market. The space is getting tougher as domestic players upgrade, push brands harder, and fight for shelf space. That showed up in the company’s reported 9.2% sales volume decline in China packaged meats in Q1 2025—an early signal that defending the crown can be just as hard as winning it.

Material Legal/Regulatory Overhangs:

Two overhangs deserve special attention.

First is U.S. political and regulatory scrutiny of foreign-owned farmland. Senator James Lankford of Oklahoma introduced the bipartisan Security and Oversight of International Landholdings (SOIL) Act of 2025, which would require mandatory CFIUS review of foreign agricultural land purchases. Given Smithfield’s footprint, anything that tightens rules here increases uncertainty.

Second is environmental litigation risk. Smithfield Foods, through its subsidiary Murphy-Brown LLC, faced nuisance lawsuits in North Carolina beginning in 2017, brought by more than 500 residents living near hog farms. Across multiple trials from 2018 to 2020, juries found the company liable, awarding compensatory and punitive damages totaling nearly $100 million. Even when litigation doesn’t threaten the core business, it can reshape costs, constrain operations, and keep reputational pressure simmering in the background.

XV. Conclusion: The Empire Faces a New Chapter

From a struggling cold-storage facility in Henan to the world’s largest pork company, WH Group’s rise is one of the most unlikely—and most consequential—transformations in modern food industry history.

Wan Long has always framed that arc in moral terms as much as managerial ones: "We have never done anything bad, that's why we are not easy to get knocked down, that's why we can stand the test of time and the test of market, so we can recover very quickly."

Now the question isn’t whether the empire was built. It’s whether it can keep compounding.

The next chapter won’t be written with the same tailwinds that powered the last one. Consumer preferences are shifting. Geopolitics is louder and riskier. Competition in China is tightening. And none of those problems can be solved by size alone.

But size does buy choices. The platform Wan Long assembled—China demand, U.S. production strength, and a growing European footprint—gives WH Group room to maneuver. It can keep pushing toward packaged meats, where the profit lives. It can look outward to new export markets. It can squeeze more efficiency out of an already industrial operation. Those levers may not be glamorous, but in a cyclical commodity business, they’re the difference between merely surviving and building durability.

For investors, that’s the trade: exposure to one of the world’s biggest food categories, run by an organization that has proven it can execute at scale—paired with governance and political risk that will always sit in the background.

The clerk who walked through the gates of a provincial meat factory in 1968 built something genuinely extraordinary. What happens next will depend on forces both inside the company and far beyond it—and on whether the institutions he built can outlast the founder who defined them.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music