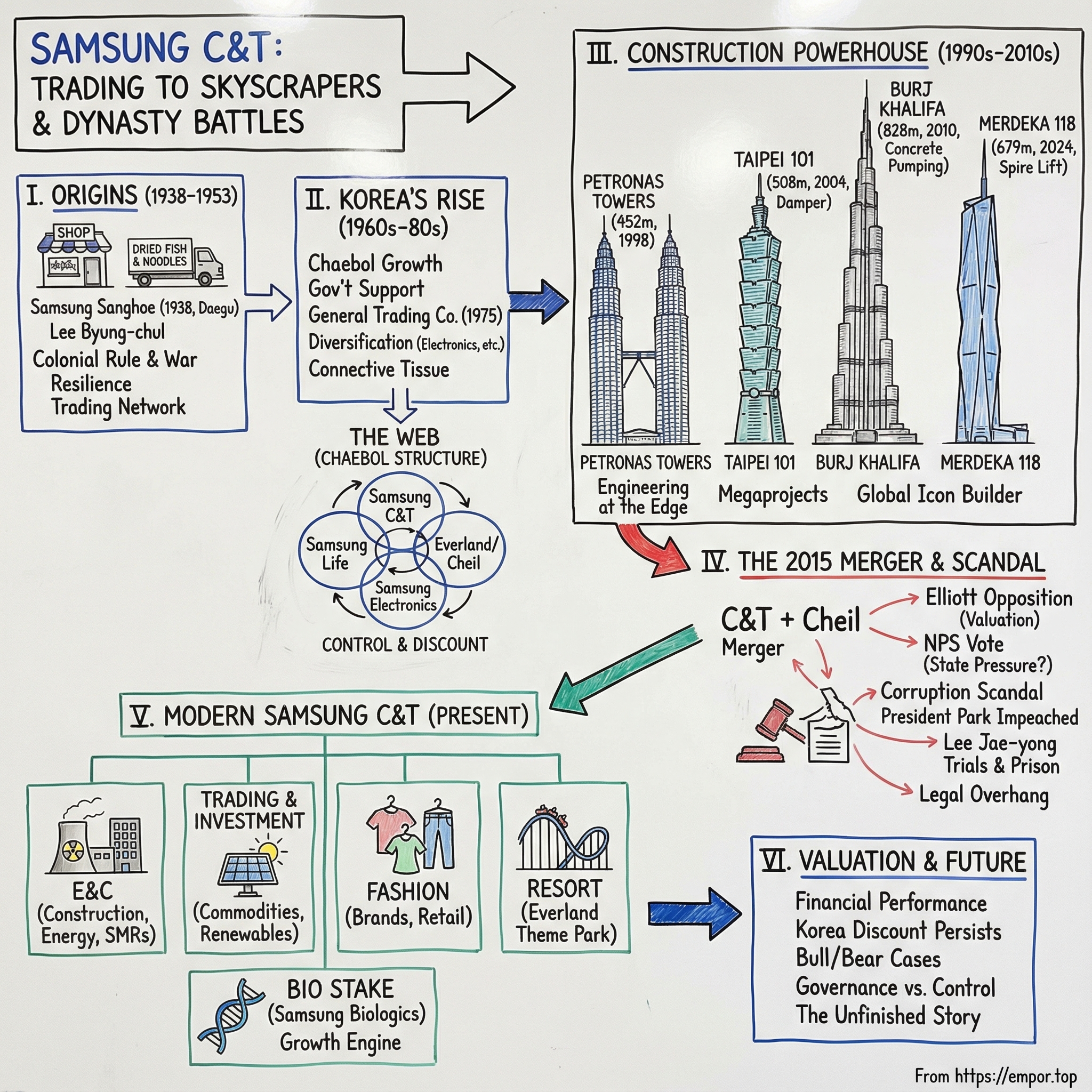

Samsung C&T Corporation: The Original Samsung and the Battle for a Dynasty

I. Introduction: Where It All Began

Picture this: you’re on the observation deck of the Burj Khalifa in Dubai, more than 800 meters above the desert, looking out at a city that somehow feels both futuristic and impossible. Or you’re in Kuala Lumpur, craning your neck at the Petronas Towers as their skybridge hangs between the two spires. Or you’re watching Merdeka 118 rise into the skyline, a brand-new statement of national ambition.

What connects these landmarks isn’t a Middle Eastern developer or a famous Western architect.

It’s Samsung C&T.

Samsung C&T’s Engineering and Construction Group has been behind some of the most iconic skyscrapers on Earth: the Burj Khalifa in Dubai, the Petronas Towers and Merdeka 118 in Kuala Lumpur, and Taipei 101 in Taiwan. Somehow, one company ended up with a résumé that reads like a greatest-hits album of modern megaprojects—a builder of record-setters.

But the twist that makes this story worth telling is that Samsung C&T didn’t start as a construction champion at all. It started as the very first Samsung company.

Back in 1938, under Japanese colonial rule, Samsung began as a modest trading business in Korea, exporting everyday goods like dried fish and noodles and importing essentials the domestic economy couldn’t easily produce. No semiconductors. No smartphones. Not even concrete. Just a founder trying to build something durable in a country that had almost no room to dream.

Over the decades, that trading firm evolved, expanded, and eventually merged into the modern Samsung C&T—one of the most consequential, and least understood, companies in the entire Samsung universe. Because outside Korea, “Samsung” usually means sleek electronics: phones, TVs, memory chips. Samsung C&T rarely comes up in that conversation, even though it employs more than 17,000 people and sits at the center of Samsung’s internal architecture. It’s often described as the group’s de facto holding company, in large part because it holds significant stakes across key Samsung affiliates.

And that’s where the story stops being just an epic about building towers—and turns into a saga about building power.

Samsung C&T’s rise mirrors South Korea’s rise: from occupation, to war, to reconstruction, to a modern industrial miracle. Along the way, it mastered engineering at the edge of what’s physically possible. But it also became entangled in the complicated machinery of the chaebol system—the cross-shareholdings, the family control, the political ties, and the persistent “Korea Discount” that makes even world-class companies trade below what their underlying assets suggest they’re worth. Investor groups argue that higher dividend payouts and more shareholder-friendly capital allocation could narrow that gap. The discount, in other words, isn’t just about numbers—it’s about trust, governance, and whether outside shareholders ever truly get a fair seat at the table.

So here’s the question that drives everything that follows:

How does a trading shop founded in colonial Korea become the keystone in a $400 billion-plus conglomerate’s control structure, the builder of the world’s tallest towers, and the flashpoint for a scandal that helped topple a president—and sent Samsung’s heir to prison?

II. Origins: Samsung Before Samsung (1938–1953)

In the early spring of 1938, a 28-year-old from a wealthy landowning family made a bet that, in hindsight, looks almost absurdly ambitious. Lee Byung-chul—born on 12 February 1910 in Uiryeong County, South Gyeongsang Province—would go on to found what became Samsung Group, the country’s largest chaebol. But at the moment he started, there was no “Samsung” as the world knows it. There was just Korea under occupation, and one man trying to build something Korean-owned in a system designed to prevent exactly that.

Because Korea in 1938 wasn’t an independent country. Japan had annexed the peninsula in 1910, the year of Lee’s birth, and ruled until 1945. As World War II expanded, the colonial government tightened its grip on commerce. Local businesses faced strict controls, and many were pushed into contributing to the Japanese war effort. Starting a Korean business in that environment wasn’t just difficult. It was inherently fragile—exposed to politics, scarcity, and sudden rule changes.

Lee’s background gave him a rare advantage. He was the son of a wealthy yangban landowning family, part of the Gyeongju Lee clan, which meant he could pursue an education that most Koreans at the time simply couldn’t access. He attended Joongdong High School in Seoul, graduating in 1929, and then went to Japan, enrolling in political economy at Waseda University in Tokyo in 1930. He didn’t finish—dropping out in 1934—but the experience mattered. Japan was industrializing fast, and Lee saw modern business up close: systems, scale, and the power of connected trade.

His return home was driven less by strategy than circumstance. His father died, and Lee came back to manage the family’s estates. With inheritance capital behind him, he tried entrepreneurship first through a rice mill. It didn’t work. The business failed, and it was a blunt early lesson: money helps, but it doesn’t guarantee product-market fit, operations, or distribution.

So Lee reset. On 1 March 1938, in Daegu, he launched an export business and named it Samsung Trading Co.—Samsung Sanghoe. “Samsung” translates to “three stars,” a name meant to signal permanence and power: large, strong, and enduring. From the beginning, the ambition wasn’t small-business ambition. It was nation-building ambition.

The first version of Samsung was a trading shop, but it was also a network. Lee’s modest storehouse became a conduit for moving goods—exporting and distributing products across Korea and into China. It didn’t take long for it to turn a profit. Friends later recalled how hands-on Lee was, personally overseeing truck shipments. This wasn’t a distant owner. It was a founder obsessing over execution, learning the rhythms of logistics, supply constraints, and demand.

Then history intervened—again. By the mid-1940s, Samsung was transporting goods throughout Korea and to other countries. After liberation in 1945, the economy reshuffled, and by 1947 the company was based in Seoul. When the Korean War began in 1950, Samsung was already among the ten largest trading companies in the country. But scale didn’t protect it from the most basic risk in wartime: geography. Seoul fell to the North Korean army, and Lee was forced to flee south, relocating operations to Busan.

The Korean War was an existential crisis for the peninsula—and, paradoxically, an accelerant for the companies that survived it. Korea’s infrastructure was shattered, supply chains collapsed, and basic goods became strategic. In Busan, Samsung adapted to whatever the country needed next. With the Japanese departure leaving a vacuum in industry, Lee moved quickly, including shifting focus toward sugar refining as part of Samsung’s earliest steps into diversification.

This is the origin story that matters for everything that follows. Samsung C&T didn’t come out of a stable, rules-based economy where you could plan in five-year increments. It was forged in occupation, war, and constant uncertainty. Its earliest competitive advantage wasn’t technology or brand. It was resilience—the ability to endure disruption, reroute around chaos, and keep trading anyway. That survival instinct would become a core feature of the company for decades to come.

III. The Miracle on the Han River: Samsung and Korea's Rise (1960s–1980s)

When the Korean War ended, the country was rubble—physically, financially, psychologically. South Korea’s income levels sat alongside the poorest regions in the world. And then, in barely a couple of decades, it pulled off what became known as the “Miracle on the Han River”: a national transformation so fast it still feels improbable.

A big reason it happened was that South Korea didn’t leave growth to the invisible hand. It was planned, pushed, and, at times, coerced. In 1961, General Park Chung-hee seized power in a military coup. Park ruled as an authoritarian, but he was also a relentless modernizer. He wanted exports. He wanted factories. He wanted industrial capacity—fast. And to get it, he needed partners who could execute at scale.

Enter the chaebol.

Chaebol are Korea’s sprawling, family-controlled conglomerates—companies that don’t just operate in one industry, but in many, tied together through ownership links and family leadership. Unlike Japan’s pre-war zaibatsu, which were later dismantled, Korea’s chaebol were actively nurtured. They received policy support: access to capital, licenses, and incentives geared toward exporting. In return, they were expected to deliver the state’s priorities—jobs, foreign currency, and rapid industrial growth.

Lee Byung-chul wasn’t a passive beneficiary of this system; he helped shape it. In August 1961, he played a role in forming the Federation of Korean Industries, a powerful business group that brought together many of the country’s major companies. Later, Lee chaired the Federation, and for a time he was widely regarded as Korea’s richest man.

For Samsung’s original trading business—what would become Samsung C&T—this era was rocket fuel. In 1975, the Korean government designated Samsung C&T as the nation’s first “general trading company,” effectively anointing it as a lead operator for Korea’s export push. It wasn’t just a title. It was a signal: Samsung C&T was now a national instrument for going global.

At the same time, Samsung was diversifying with astonishing speed. In 1965, Lee established the Samsung Culture Foundation, aimed at supporting programs that would enrich Korean cultural life. In 1969, Samsung Electronics Manufacturing—later renamed Samsung Electronics—was established and later merged with Samsung-Sanyo Electric. In 1970, Samsung Electronics Manufacturing was still tiny, with just 45 employees and roughly $250,000 in sales, producing household electronics.

But momentum compounds. Consumer electronics led to more products, and then to more ambition. Calculators came next. Then semiconductors. By the late 1970s, Samsung was producing televisions at massive scale and building the industrial base that would later make it a global technology powerhouse.

And throughout all of this, Samsung C&T’s trading operation was becoming something more than a seller of goods. It was turning into a coordinating hub—connecting suppliers, financing, shipping, and overseas customers. That role would matter enormously later, because it positioned Samsung C&T as a kind of connective tissue across the group.

Lee Byung-chul died in Seoul on November 19, 1987. By then, he had built a conglomerate spanning more than 20 subsidiaries, with businesses across electronics, finance, shipbuilding, and more. After his death, the Ho-Am Art Museum opened to the public, showcasing what became known as one of the largest private Korean art collections in the country, including works designated as National Treasures by the Korean government.

Leadership of Samsung passed to his third son, Lee Kun-hee—who turned out to be just as consequential as his father, but in a different way. Kun-hee looked at Samsung’s position in the world and saw a problem: the company was big, but it wasn’t respected. Internationally, Samsung was still associated with low quality. The brand didn’t stand for excellence.

In 1993, he gathered executives in Germany and delivered the line that became legend: “Change everything except your wife and kids.” It kicked off Samsung’s quality revolution—the internal push that ultimately helped make Samsung Electronics one of the most valuable technology companies on Earth.

This whole period is the backdrop for understanding Samsung C&T’s later role—and later controversy. The “Miracle” wasn’t just an economic story. It was a governance story: a symbiotic relationship between the state and the chaebol that powered growth, but also created a system where corporate control, national interest, and politics could blur together. That blur would come roaring back into view in 2015.

IV. Building the Skyline of the World: The Construction Powerhouse (1990s–2010s)

By the mid-1990s, Samsung C&T wasn’t just a trading house with international reach anymore. It had become something else entirely: a contractor trusted to take on the kinds of projects where a mistake isn’t a cost overrun—it’s a headline.

And over the next two decades, it assembled a portfolio that reads less like a corporate brochure and more like a tour of the modern world’s most audacious bets.

The pattern is important. These weren’t routine jobs. They were “first time anyone’s tried this” jobs. The kind that force you to invent methods, machinery, and project management muscle as you go.

The first big proof point was in Malaysia.

The Petronas Towers: Where It All Started

In 1991, Samsung C&T was selected to build one of the two Petronas Towers in Kuala Lumpur—Tower Two. When the towers opened in 1998, they rose 452 meters and became the tallest buildings in the world, holding that title until 2004.

Even getting the project started required a reset. The ground was so soft that, after testing, the entire foundation plan had to be shifted 60 meters from the original location because the rock bed was too deep on one side. Samsung C&T worked alongside Japan’s Hazama Corporation, with each contractor building one tower in a parallel, side-by-side race.

Then came the feature everyone remembers: the Skybridge connecting the two towers at the 41st and 42nd floors. It wasn’t just visually iconic. It was a logistics and precision challenge—a 58.4-meter, double-decked structure that had to be assembled on the ground and then lifted into the air with hydraulic jacks. The hoist took almost two days, and Malaysia watched it happen live on television.

Petronas didn’t just put Samsung C&T on the map. It proved the company could execute when the whole world was watching.

Taipei 101: Earthquake-Proof Engineering

Next came Taipei 101, completed in 2004. At 508 meters, it briefly took the title of the world’s tallest building. But in Taiwan, height is only half the problem. The building had to survive major earthquakes and typhoons.

The solution was one of the most famous pieces of structural engineering in any skyscraper: a tuned mass damper—a 660-metric-ton pendulum suspended near the top of the tower that moves to counteract sway from wind and seismic activity. It remains the largest and heaviest tuned mass damper ever built.

This was a different kind of engineering flex than Petronas. Less about assembling a spectacle and more about designing safety and stability into a structure that would be tested, sooner or later, by nature.

Burj Khalifa: Reaching for the Impossible

And then came Dubai—and the project that would define the era: Burj Khalifa.

Samsung C&T built the tower in a joint venture with BESIX from Belgium and Arabtec from the UAE, with Turner serving as the project manager on the main construction contract. Within the joint venture, Samsung’s Technology and Construction division was the main stakeholder, holding a 55% share, while BESIX held 30% and Arabtec 15%.

Construction began on 12 January 2004. The exterior was completed on 1 October 2009. The building officially opened on 4 January 2010.

The scale was almost hard to comprehend: about 330,000 cubic meters of concrete, 55,000 tonnes of steel rebar, and 22 million man-hours.

But the story isn’t the volume—it’s the constraints. Dubai’s desert environment meant extreme heat and strong winds. And the height itself created a problem that normal construction equipment simply couldn’t solve: how do you pump concrete to floors hundreds of meters in the air, reliably, day after day?

To do it, Samsung C&T and Putzmeister developed new high-pressure pumping technology, including a super high-pressure trailer concrete pump built specifically for the project. This wasn’t “use the best equipment available.” This was “build equipment that doesn’t exist yet.”

Even finishing the building required thinking like a physicist. Engineers expected the structure to drop by 65 centimeters under its own weight as the full load came on. So floors were deliberately constructed 2–4 millimeters higher to reduce settlement damage once everything was complete. That’s the level of precision involved when you’re stacking 828 meters of building into the sky.

Merdeka 118: Completing the Trilogy

In January 2024, Samsung C&T added another landmark to its résumé: Merdeka 118 in Kuala Lumpur. The company announced on Jan. 11 that it had completed the building, which stands 679 meters tall and officially opened on Jan. 10.

Merdeka 118 is a massive complex: 118 floors above ground, five below, and a total area of 673,862 square meters. Building it required advanced high-pressure concrete pumping and a 160-meter spire. Instead of relying on tower cranes at extreme altitude, Samsung C&T used a lift-up method—pushing the spire upward with hydraulic jacks from around 500 meters.

Taken together—Petronas, Taipei 101, Burj Khalifa, Merdeka 118—this is why Samsung C&T’s construction arm matters to the broader story. For investors, it’s a reminder that Samsung C&T isn’t only an ownership node inside a chaebol web. It has a core operating business with real, hard-to-replicate capability: the accumulated, field-tested expertise to deliver megaprojects at the outer edge of engineering.

And that capability—along with the company’s strategic shareholdings—helped make Samsung C&T something rare: a business that could shape skylines and, later, shape the balance of power inside Samsung itself.

V. The Everland-Cheil-C&T Web: How Chaebols Really Work

To really understand Samsung C&T, you have to understand what a chaebol is in practice, not in theory. On paper, it’s a group of affiliated companies. In reality, it’s an ownership machine: a carefully layered set of cross-shareholdings that lets a founding family steer a massive industrial empire while owning far less of it directly than you might expect.

That structure comes with a price. Investors often apply a discount to companies trapped inside these webs, because the system can prioritize control and succession over clean governance and straightforward capital allocation. Samsung C&T itself was shaped through a series of M&A moves that critics argue were designed less for efficiency and more to preserve the Lee family’s grip. Over time, those dynamics have weighed on valuations across the group.

If Samsung’s industrial achievements are famous, its org chart is infamous.

The Samsung Group’s structure is a maze—so much so that, over the past two decades, many South Korean chaebols have simplified into two-layer holding company setups. Samsung is one of the few major holdouts still operating with the older-style, cross-linked chaebol structure.

And sitting in the middle of that maze is Samsung C&T. It’s not a holding company in the legal, regulatory sense. But functionally, it’s often treated like one, because it sits on key stakes across the group and helps anchor control.

Here are the puzzle pieces that matter most.

Samsung Everland (later renamed Cheil Industries): Samsung Everland was established in 1963 with the mission of assisting Korea's national land development. Since then, it evolved into a leader in Korea's service industry by expanding into resorts, food and beverage, and landscaping. In December 2013, Samsung Everland acquired the Fashion Group of Cheil Industries, a prominent industry player founded in 1954. After the merger, it changed its name to Cheil Industries and shifted focus toward lifestyle design.

Everland mattered for a deeper reason: it was a key vehicle through which the Lee family held stakes in other Samsung affiliates. When Lee Jae-yong, the heir apparent, needed to consolidate control after his father’s 2014 heart attack, the path ran through these entities.

The shareholding web: This is where it starts to feel like a loop. Samsung C&T owns a significant stake in Samsung Life Insurance. Samsung Life Insurance, in turn, is a major shareholder in Samsung Electronics. Samsung Electronics holds stakes in other Samsung affiliates. And from there, the ownership threads continue—company into company, stake into stake.

Samsung C&T also has a 43.06 percent stake in Samsung Biologics. For Samsung C&T, Bioepis is now a second-tier subsidiary, but will be positioned as a direct subsidiary, meaning Bioepis’ earnings will be reflected directly in Samsung C&T’s consolidated earnings to improve financial prudence.

Why build a structure like this? For the Lee family, it does three big things:

-

Control leverage: With the right positions in the right entities—especially Samsung C&T—the family can influence much larger businesses with relatively limited direct ownership.

-

Protection from hostile takeovers: Circular ownership makes it extremely difficult for an outside investor to buy their way to control of any single key affiliate.

-

Succession planning: The structure provides a way to shift influence across generations—though, as 2015 would prove, succession planning in a public market can get messy fast.

But the tradeoff lands on minority shareholders. Investor groups argue that Samsung C&T’s capital allocation has not been shareholder-friendly enough, and that this is part of why the company trades with a steep “Korea Discount.” They’ve pushed for higher dividends and a large share repurchase program, proposing KRW 500 billion in buybacks—roughly half of annual free cash flow from operations.

Some observers argue the discount is structural. Even within today’s chaebol setup, Palliser estimates a $25 million valuation gap. And in their view, moving to a cleaner holding company structure would lift the value of Samsung C&T’s subsidiaries further, widening that gap relative to where the stock trades.

This is the Korea Discount in its purest form: world-class assets inside a system that investors don’t fully trust—because the incentives can be opaque, the ownership is complex, and control can matter more than return on capital.

And it’s exactly this web—Everland, Cheil, and Samsung C&T—that set the stage for the merger fight that would explode in 2015.

VI. The 2015 Merger: The Battle for Samsung's Future

No event in Samsung C&T’s modern history is more consequential—or more controversial—than the 2015 merger with Cheil Industries. It’s the moment where the chaebol web stops being an abstract governance concept and becomes a live battlefield: succession, valuation, shareholder rights, and, soon enough, national politics.

The Setup

By 2014, Samsung was already preparing for a generational handoff. Lee Kun-hee, the group’s long-time chairman, suffered a heart attack that left him incapacitated, and day-to-day leadership effectively shifted to his son, Lee Jae-yong.

But in a chaebol, leadership isn’t just about titles. It’s about control—who owns which pieces of the web.

Lee Jae-yong held more of Cheil Industries than he did of Samsung C&T. And Samsung C&T, as we’ve seen, sat in a uniquely powerful position in the group’s ownership structure. Put those two facts together and you get the logic of the deal: if Cheil and Samsung C&T could be combined on favorable terms, it would strengthen the heir’s grip on the center of the maze.

The catch was obvious: “favorable terms” for one side often means “unfair terms” for the other. Which leads us straight to the fight.

The Timeline

On May 26, 2015, Samsung C&T and Cheil—both Samsung affiliates—announced they would merge. The very next day, May 27, Elliott Associates went public with its opposition. The reason was simple and explosive: the proposed exchange ratio—1 share of Samsung C&T for 0.35 shares of Cheil—was, in Elliott’s view, a clear undervaluation of Samsung C&T.

To Elliott, the math wasn’t just bad. It was the point.

Elliott Management, founded by Paul Singer, argued that the deal effectively shifted value away from Samsung C&T shareholders and toward Cheil shareholders—which mattered a lot because Lee Jae-yong and his family held more Cheil than Samsung C&T. Elliott owned about 7% of Samsung C&T and made the merger a test case for corporate governance in South Korea. Singer said publicly, including in comments to CNBC, that shareholders should reject the merger to set a new standard for accountability in the market.

The Proxy Battle

Elliott ran a full-scale activist campaign.

It sought an injunction in Seoul to delay the shareholder vote. It published valuation arguments attacking the exchange ratio. It courted proxy advisory firms. And it pushed a public message that was easy to understand: this wasn’t a merger designed to create value—it was a merger designed to concentrate control.

ISS and Glass Lewis recommended voting against the deal. Elliott’s injunction request went to a Seoul district court. The court rejected it, clearing the way for a vote.

And at that point, the battle narrowed to one question: who could deliver the swing votes?

That answer was the National Pension Service.

The NPS—South Korea’s public pension fund—was Samsung C&T’s largest single shareholder, holding 11.21% in 2015. In a vote that required a supermajority, that stake wasn’t just influential. It was potentially decisive.

Samsung affiliates lined up behind the merger. Many foreign investors leaned toward Elliott’s position. Domestic retail shareholders were split and hard to mobilize as a bloc. In that landscape, the NPS’s ~11% was the one large, unified chunk that could tip the result.

The NPS Decision

In early July, the interactions that would later be scrutinized began to crystallize.

On July 7, 2015, Hong Wan-sun, then the NPS chief investment officer, met with Samsung Electronics Vice Chairman Jay Y. Lee. Three other senior NPS officials—including the head of the domestic equity division—also attended.

On July 10, the NPS investment committee voted internally to approve the merger: eight of the twelve members supported it.

On July 17, the NPS cast its vote in favor at the shareholder meetings for both Samsung C&T and Cheil, helping push the merger over the line.

After losing the fight, Elliott announced on Aug. 6, 2015 that it would sell a bulk of its Samsung C&T shares back to the company. And on Sept. 1, 2015, Samsung C&T formally took over Cheil Industries, creating the combined entity.

The merger was done. The fallout was just getting started.

What This Meant for Shareholders

For Samsung C&T’s minority shareholders, the merger became a clean, painful example of the Korea Discount in action: world-class assets sitting inside a system where control can outrank shareholder value, and where the “independent” swing vote can belong to a state-linked institution.

The precedent worried investors for a broader reason. If the country’s biggest pension fund could vote with a controlling family even amid serious questions about valuation, then what protections did minority shareholders really have?

Elliott had the analysis, the proxy advisors, and a governance narrative that made sense to global markets. None of it mattered once the pivotal votes were locked up.

And that’s why 2015 isn’t just a Samsung C&T story. It’s the moment the internal mechanics of Samsung’s succession became a national controversy—one that would soon pull in prosecutors, politicians, and the presidency itself.

VII. The Scandal and Aftermath: A Decade in Court

The NPS vote could have faded into history as one more episode of chaebol-government back-scratching. Instead, South Korea’s political system detonated. And suddenly, that merger wasn’t just a corporate governance fight—it was a piece of evidence in a corruption scandal that would help bring down a president.

The Corruption Scandal

Elliott and Mason both argued that the NPS vote wasn’t an independent investment decision at all. They alleged it was the product of state pressure, with involvement reaching up to then-President Park Geun-hye, designed to support the Lee family’s succession plan—even if that meant sacrificing returns for public shareholders.

President Park was later convicted of receiving bribes tied to helping execute a Samsung succession plan.

Investigators estimated the decision cost the pension fund at least 138.8 billion won, about $130 million, in losses. A special prosecutors’ investigation later concluded that Choi Soon-sil—Park’s close confidante at the center of the wider scandal—had pressured then–Health Minister Moon Hyung-pyo to push the NPS toward approving the deal, with Samsung allegedly providing business favors in return.

In February 2017, Lee Jae-yong was indicted and arrested after the Seoul Central District Court issued a warrant. Prosecutors accused him of offering about $38 million in bribes to four entities controlled by associates of President Park, including a Germany-based company tied to equestrian training for the daughter of Choi Soon-sil. The alleged quid pro quo was straightforward: government help securing a merger that strengthened Lee’s control over Samsung during the leadership transition after his father fell ill.

The Prison Years

In August 2017, a three-judge panel at the Seoul Central District Court found Lee guilty and sentenced him to five years in prison. Prosecutors had sought a far longer sentence.

Less than a year later, in February 2018, the Seoul High Court cut the sentence to 2.5 years and suspended it—sending Lee home after roughly a year in detention.

That wasn’t the end. The Supreme Court later sent the case back to the Seoul High Court for a retrial. In January 2021, Lee was sentenced again—two years and six months—after the court found him guilty of bribery, embezzlement, and concealment of criminal proceeds.

Even while imprisoned, Samsung kept him as vice chairman in title. The Korea Herald reported in August 2021 that Lee retained the role but was not drawing a salary and was not registered as an executive, in compliance with a work ban. In August 2022, President Yoon Suk Yeol pardoned Lee, citing Samsung’s importance to the economy. The pardon cleared the way for him to resume leadership.

The Final Verdict on the Merger

Running in parallel was a separate track focused on the merger itself—allegations of stock manipulation and accounting fraud tied to the 2015 deal.

Here, Lee ultimately prevailed. South Korea’s Supreme Court upheld a Seoul High Court ruling that acquitted him on those fraud-related charges stemming from the merger between Cheil Industries and Samsung C&T. The same decision also upheld acquittals for thirteen former Samsung executives who had been indicted on similar charges.

The legal cloud that had hovered over the merger for years finally lifted.

The International Arbitration

Even as Lee was cleared in Korean courts on the merger-related fraud allegations, the story didn’t end for Elliott and Mason. Both pursued international arbitration against the South Korean government, arguing that the NPS vote—if driven by political pressure—violated Korea’s obligations under the KORUS free trade agreement with the United States.

In each case, the tribunals found that Korea breached its obligation to provide fair and equitable treatment in handling the Samsung restructuring, and held the government liable to the investors for losses on their Samsung C&T shares.

Meanwhile, in 2022, South Korea’s Supreme Court confirmed a jail sentence for former health and welfare minister Moon Hyung-pyo for pressuring the NPS to approve the merger. An arbitration tribunal ordered the South Korean government to pay Elliott about $53.6 million in damages, plus delayed interest, and $28.9 million in legal fees.

Where Does This Leave Us?

Lee Jae-yong marked his third anniversary as Samsung Electronics chairman on October 27, a milestone widely interpreted as signaling the company’s move beyond its biggest judicial overhang.

For investors, the lesson of the last decade is messy but clear. The merger battle exposed how fragile minority shareholder protections can be when a succession plan runs through the state’s most powerful institutions. Lee’s indictment, conviction, imprisonment, pardon, and eventual acquittal on merger-related fraud charges created years of uncertainty.

But the merger still accomplished what it was designed to do: it consolidated control. Whether Samsung C&T’s minority shareholders received fair value remains fiercely disputed. The governance question, however, is no longer theoretical—it played out in courtrooms, in the streets, and at the very top of Korean politics.

VIII. The Modern Samsung C&T: A Four-Headed Conglomerate

After all the courtroom drama, it’s easy to forget a simple truth: Samsung C&T is still, at its core, an operating company. In fact, today’s Samsung C&T is really four businesses under one roof—run as four major groups, each with its own culture, economics, and role inside the wider Samsung ecosystem.

At the top sits an 11-member Board of Directors, which includes the President and CEOs of the four operating groups—Engineering & Construction, Trading & Investment, Fashion, and Resort—along with the corporation’s CFO and six independent directors. It’s a structure that reflects what Samsung C&T has become: less a single business line, more a portfolio.

Engineering & Construction Group

Samsung C&T’s Engineering & Construction Group is the part of the company most people recognize—if they recognize Samsung C&T at all. This is the team behind skyscraper icons like the 828-meter Burj Khalifa in Dubai, the Petronas Towers and Merdeka 118 in Kuala Lumpur, Taipei 101 in Taiwan, and the Tadawul Tower in Riyadh. It’s also built major healthcare and aviation projects like the Cleveland Clinic in Abu Dhabi and Taoyuan International Airport Terminal 3, along with major Korean projects including Incheon International Airport, the Giheung Semiconductor Complex, and Raemian apartment complexes.

Beyond buildings, Samsung C&T’s Plant Business Unit has worked on large-scale energy infrastructure—both conventional and nuclear—including the UAE Nuclear Power Complex, the Emal Power Plant, and an LNG terminal in Singapore.

But even great builders run into cycles. In the near term, the construction division has faced headwinds as its pipeline of large projects has thinned. According to Samsung C&T’s semiannual report for the first half of 2025, the remaining order backlog stood at $19.52 billion (₩27.7 trillion) and was expected to fall to about $14.08 billion (₩20 trillion) by year-end—roughly implying about a year’s worth of orders on hand. With fewer megaprojects queued up, Samsung C&T has looked again to urban redevelopment as a key source of new work.

At the same time, it’s trying to place bets on what comes next—especially in energy. Samsung C&T’s E&C Group signed an MoU with Synthos Green Energy to support Small Modular Reactor development in Poland and across Central and Eastern Europe. Synthos Green Energy is leading Poland’s national SMR initiative and plans to deploy up to 24 BWRX-300 units by the early 2030s, starting with the country’s first SMR plant, with ambitions to expand into Czechia, Hungary, Lithuania, Bulgaria, and Romania.

The group has also pushed into infrastructure investment models, not just pure contracting. Samsung C&T formed a consortium of Korean investors to manage the investment, construction, and operation of a major highway project in Türkiye’s capital. The project was scheduled for completion in 2027 under a public-private partnership structure: privately operated for a period before being handed over to the government. The total project cost was approximately $1.6 billion, with toll revenues of more than $4.4 billion expected over a 15-year operating period.

Trading & Investment Group

If Engineering & Construction is Samsung C&T’s public face, Trading & Investment is its original DNA. This group trades industrial commodities—chemicals, steel, and natural resources—and also helps organize large projects, including Samsung Renewable Energy, a wind and solar cluster, and the Balkhash Thermal Power Plant.

Recently, the group delivered year-on-year growth in both revenue and profit, helped by increased trading volumes and gains from selling solar assets. The advantage here is Samsung C&T’s global footprint and decades of relationships. The risk is the same one every trading business lives with: commodity price volatility.

Fashion Group

Then there’s fashion—an unusual line item if your mental model of Samsung begins and ends with semiconductors.

Samsung C&T sells men’s and women’s clothing under brands including GALAXY, BEANPOLE, KUHO, LEBEIGE, and 8 Seconds. It expanded Beanpole into children’s lines, outdoor wear, and accessories, while also launching newer brands in womenswear (KUHO and LeBeige) and fast fashion (8 Seconds).

But unlike skyscrapers, fashion is brutally tied to consumer mood—and lately, that mood has been soft. The Fashion Group posted small declines in revenue and profit, citing weaker consumer sentiment and climate-related challenges.

Resort Group

The last of the four is Resort, anchored by Everland—South Korea’s largest theme park—located in Yongin, Gyeonggi Province. Everland is operated by Samsung C&T (formerly Samsung Everland, later Cheil Industries), and in 2018 it recorded 5.85 million visitors, ranking 19th globally for amusement park attendance. By 2024, Everland had welcomed around 270 million visitors over its history.

In contrast to the fashion business, Resort delivered growth in revenue and profit, supported by expansion in food and beverage and new food supply contracts.

The Bio Division: A Hidden Value Driver

One of the most overlooked parts of Samsung C&T isn’t a “group” at all. It’s an ownership stake—specifically, its 43.06 percent stake in Samsung Biologics, one of the world’s leading contract drug manufacturers.

Samsung C&T began moving into life sciences by investing in biologics CDMO in 2011. And over time, that bet has become increasingly central to the Samsung C&T investment story. Samsung Biologics, which has Samsung Bioepis as a 100% owned subsidiary, has been positioned as a long-term growth engine for the broader group.

Samsung Biologics has continued to expand aggressively. It announced it would acquire its first U.S. drug production facility from GSK plc for $280 million, framing the move as a way to reduce tariff-related risk, with plans for further investment. The acquisition is expected to increase total capacity by 60,000 liters to 845,000 liters.

That momentum has shown up in orders, too: Samsung Biologics reported record orders of 6.8 trillion won (about $4.6 billion) so far this year, 26.1% higher than the total for 2024.

Put it all together and you get the modern Samsung C&T: a company that builds some of the world’s most complex infrastructure, trades the raw materials that keep industry moving, runs major consumer brands and destinations, and holds a powerful stake in a fast-growing biotech champion.

Which brings us back to the central tension of this story. Samsung C&T isn’t just a set of businesses—it’s a strategic node. And that’s why questions about governance, valuation, and control keep following it, no matter how many skyscrapers it builds.

IX. Financial Performance and Valuation

For all the governance drama and ownership complexity, Samsung C&T still has to do the basic thing every public company has to do: put up numbers. And in 2024, it did.

Samsung C&T posted revenue of KRW 42.103 trillion and operating profit of KRW 2.984 trillion. Both were modestly higher than 2023, with revenue up slightly from KRW 41.896 trillion and operating profit rising from KRW 2.870 trillion.

On the bottom line, consolidated net income came in at 2.77 trillion won (about $1.9 billion), up 1.9% year over year. Samsung C&T attributed the improvement to the same feature that makes the company so hard to categorize in the first place: diversification. When one business line slows, another can carry.

That mix showed up clearly across the groups. Engineering & Construction stayed steady by focusing on profitability rather than chasing volume. Trading & Investment held up on the strength of solar energy projects, even against a slowing global economy. But not everything moved in the right direction. The trading and investment division saw operating profit fall 16.7%, and the fashion division’s operating profit declined 12.4%.

The other pressure point was construction. Sales slowed, and while the division still reported a sizable order backlog—27.7 trillion won, supported by projects in places like Qatar, Saudi Arabia, and Guam—the backlog itself has become a near-term investor worry because it signals how much work is already locked in for the next stretch.

The Valuation Gap

And this is where Samsung C&T starts to look less like a normal operating company and more like a market mystery.

Investor groups—together owning more than 1% of the company’s common shares—have organized and submitted shareholder proposals aimed at what they describe as inadequate capital allocation and a steep discount to net asset value. Their argument is straightforward: Samsung C&T holds an unusually valuable set of assets, including strategic stakes in key Samsung affiliates like Samsung Electronics and Samsung Biologics, alongside real operating businesses in construction and trading. Yet despite years of intrinsic value growth, the share price has, in their view, languished since the 2015 Cheil Industries merger.

Palliser frames the disconnect in hard valuation terms. Using a 5.5x EBITDA multiple, it values the business at $8.4 billion; with net cash of $1.1 billion, that implies a total company valuation of $40.4 billion.

So why, they ask, is Samsung C&T trading at a 63% discount?

X. Bull Case and Bear Case

The Bull Case

-

Hidden asset value: A big part of the bull thesis is that Samsung C&T’s value isn’t primarily in what it sells day to day—it’s in what it owns. The stakes in Samsung Biologics and Samsung Electronics alone may be worth more than Samsung C&T’s current market capitalization. And the Biologics stake, in particular, has been climbing as the company wins major contract manufacturing deals.

-

Construction expertise you can’t fake: Plenty of firms can build buildings. Very few can build the world’s tallest towers, nuclear power plants, and mega-scale infrastructure—and actually deliver. Samsung C&T has proven it can operate at that edge. If infrastructure spending continues to accelerate, especially in the Middle East and in energy, Samsung C&T is one of the short-list contractors that can realistically take those jobs on.

-

The SMR option: Samsung C&T has been positioning itself for next-generation nuclear. In October 2025, it formed a strategic partnership with GE Vernova Hitachi Nuclear Energy to pursue SMR opportunities across Europe, Southeast Asia, and the Middle East. Alongside its cooperation with Synthos Green Energy, the strategy is clear: become a repeat partner for SMR deployment in major global markets.

-

Governance pressure is rising: Activist campaigns have been pushing for better capital allocation—higher dividends, share buybacks, and a more shareholder-friendly posture. If Samsung C&T makes even modest moves in that direction, the argument goes, the valuation discount could narrow quickly.

-

Legal overhang, largely gone: For years, the merger fight and the prosecutions created a fog of uncertainty around Samsung’s leadership and governance. With Samsung Electronics Chairman Lee Jae-yong acquitted on charges of accounting fraud and stock manipulation tied to the 2015 merger, one of the biggest sources of investor unease has been reduced.

The Bear Case

-

The Korea Discount may be permanent: The skeptics’ view is blunt: even with activism, Samsung C&T hasn’t fundamentally changed its role in the chaebol control structure or its approach to capital allocation. If governance doesn’t meaningfully evolve, the discount to underlying asset value may persist for a very long time.

-

Construction backlog could become a real headwind: Investors worry about the near-term pipeline. Samsung C&T’s remaining order backlog was expected to fall to around $14.08 billion by year-end—roughly similar to the prior year’s revenue, implying only about a year of work on hand unless new large projects land.

-

Trapped value without a restructuring: Without moving to a clearer holding-company-style structure, some investors believe the market will never fully credit Samsung C&T for the value of its stakes. Samsung remains one of only two large companies in South Korea still operating with the traditional chaebol structure, and that complexity itself can cap the valuation.

-

Consumer-facing segments are under pressure: Fashion, in particular, has been strained by weak consumer sentiment and climate-related disruption. These businesses don’t just add diversification—they can also add volatility.

-

Geopolitics comes with the territory: Some of Samsung C&T’s most attractive construction markets are also among the most geopolitically sensitive. Middle East exposure can mean outsized opportunities, but it also means outsized risk when regional tensions rise or project timelines shift.

Porter’s Five Forces Analysis:

- Threat of new entrants: Low in supertall and complex construction, where capability and credibility take decades to build; more moderate in trading and fashion.

- Supplier power: Moderate, especially when projects require specialized equipment and constrained materials.

- Buyer power: Moderate to high, since many customers are large governments or major corporates with negotiating leverage.

- Threat of substitutes: Low for proven megaproject execution; higher for fashion retail, where consumers can switch easily.

- Competitive rivalry: High in global construction, with tough competition from major Chinese, Japanese, and European contractors.

Hamilton Helmer's 7 Powers:

The clearest “Power” here is Process Power: Samsung C&T’s accumulated, hard-won ability to execute extreme projects reliably. This is the kind of advantage that doesn’t show up in a product demo, but it shows up in who gets trusted with the job. Burj Khalifa is a good example—innovations in concrete pumping, spire installation, and high-altitude construction weren’t just engineering feats; they were organizational capabilities that compound over time and are difficult for competitors to replicate.

XI. Key Metrics for Investors

If you’re following Samsung C&T as an investor, there are two dials that matter more than almost anything else.

-

Construction order backlog: This is the company’s forward-looking “work in hand”—the clearest signal of how much revenue the Engineering & Construction group can realistically see coming. The recent decline is what has investors uneasy. The upside is also straightforward: if Samsung C&T lands new, large-scale wins—especially in nuclear, infrastructure, or big Middle East projects—you’ll likely see sentiment improve quickly, because backlog is confidence made visible.

-

Discount to sum-of-the-parts NAV: Samsung C&T isn’t just valued on what it earns; it’s valued on what it owns. With major stakes in affiliates like Samsung Biologics, the gap between the company’s market value and the estimated value of its underlying pieces is a real-time scoreboard for the Korea Discount. If that discount narrows, it’s usually a sign the market is gaining confidence—either in governance, capital allocation, or the plausibility of ever unlocking that embedded value.

Together, these two metrics tell you the story from both angles: how the operating engine is doing, and whether the market is finally willing to pay for the asset base sitting underneath it.

XII. Conclusion: The Original Samsung Looks Forward

Samsung C&T is one of the strangest, most fascinating public companies on the planet. It’s simultaneously the original Samsung—the seed from which a global electronics empire grew—a world-class builder with a résumé that includes some of the most iconic structures on Earth, a diversified operator that somehow includes fashion and theme parks, and a quiet but meaningful way to participate in the boom in contract drug manufacturing through its stake in Samsung Biologics.

And it’s also a company boxed in by the very system that helped build modern Korea. The chaebol structure that concentrates control can also concentrate skepticism, leaving Samsung C&T trading at a stubborn discount because outside investors worry that value will always come second to dynasty.

That dynasty, for the moment, looks firmly in place. Samsung Electronics Chairman Lee Jae-yong remained the top stockholder among Korea’s stock-rich individuals as the local market rallied. The combined holdings of the 100 largest shareholders of listed companies climbed to about 177.2 trillion won (around $119.6 billion), up sharply from roughly 107.6 trillion won at the end of the prior year. Over the same period, Lee’s equity holdings nearly doubled to about 23.4 trillion won from 12.3 trillion won, driven by gains in Samsung affiliate shares.

Meanwhile, the decade-long legal storm that followed the 2015 merger has largely cleared. With Lee’s legal overhang gone, industry watchers expected Samsung’s 2025 personnel reshuffle to arrive with unusual significance: the first major set of moves since he was fully cleared, and a signal of what a “new Samsung” might actually look like under his unencumbered leadership.

For long-term investors, that raises the real question. Does the end of the courtroom era create room for governance reforms that narrow the Korea Discount and unlock Samsung C&T’s trapped value? Or is the discount simply the admission price—lower expected returns in exchange for exposure to an extraordinary set of businesses, forever filtered through a control-first structure?

Samsung C&T’s story began in 1938 with dried fish and noodles in colonial Korea. Eighty-seven years later, it builds the world’s tallest towers, runs Korea’s best-known theme park, and owns a major stake in one of the world’s leading drug manufacturers. It’s a journey through occupation, war, industrialization, scandal, and reinvention—and it speaks to a kind of organizational resilience that’s hard to manufacture and even harder to copy.

So the final question isn’t whether Samsung C&T has valuable assets. It clearly does. The question is whether the market will ever be willing to value those assets on their merits—or whether the Korea Discount will remain the permanent shadow cast by one of Asia’s most remarkable corporate stories.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music