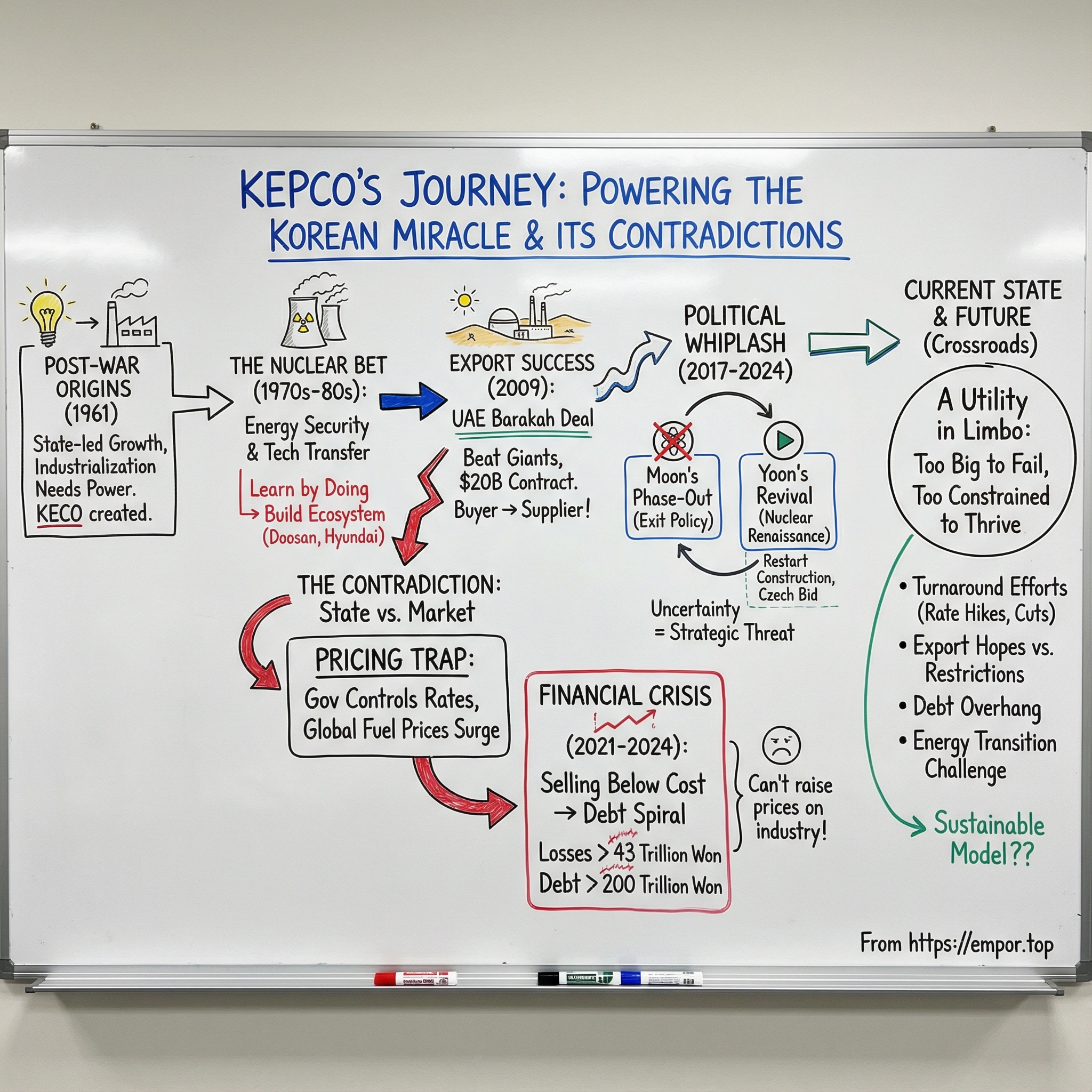

Korea Electric Power Corporation (KEPCO): The Power Behind the Korean Miracle

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

Picture a sweltering August night in Seoul in 2022. Air conditioners roar in apartment towers. Subways keep running. Factories stay lit. And out on the edges of the city, Samsung’s semiconductor fabs draw so much power they can feel like cities unto themselves. For all the complexity of a modern economy, the whole thing rests on a simple reality: electricity has to show up, instantly, every time you flip a switch.

In South Korea, that responsibility lands on one company—Korea Electric Power Corporation, KEPCO.

KEPCO is the country’s dominant electric utility, running the grid end to end: generation, transmission, distribution, and the development of new power projects across nuclear, coal, and renewables. Through its subsidiaries, KEPCO accounts for roughly 96% of Korea’s electricity generation as of 2023. It’s also a global-scale enterprise; in 2023 it ranked 258 on the Fortune Global 500.

But the reason KEPCO is such a compelling story isn’t just its size. It’s the contradiction at its core.

On one hand, KEPCO helped build one of the most capable nuclear power industries in the world—so capable that Korea went from buying turnkey reactors to exporting them, beating heavyweights like France’s Areva and America’s Westinghouse for marquee projects in places like the UAE and, later, the Czech Republic.

On the other hand, KEPCO has been bleeding money in a way that looks almost impossible for a monopoly utility. As global energy prices surged between 2021 and 2023—accelerated by the Russia-Ukraine war—KEPCO continued selling electricity for less than it cost to produce. In most countries, a utility would eventually raise rates to match reality. KEPCO couldn’t do that on its own.

That tension sets up the central question for this episode: how did a government utility become a nuclear technology exporter while also flirting with what analysts have called a potential debt “death spiral”?

To answer it, you have to understand what KEPCO actually is. The South Korean government, directly and indirectly, owns 51.10% of the company. That puts KEPCO in a permanent in-between state: part state instrument, part publicly traded enterprise, and part national champion expected to serve the broader economy—even when that conflicts with running a financially healthy utility.

Over the course of this story, we’ll follow KEPCO through the big themes that shaped modern Korea: state capitalism and energy security as national strategy; the audacious nuclear bet and the industrial ecosystem it created; the policy whiplash between administrations; and the uniquely unforgiving challenge of being responsible for powering a country while not fully controlling the price of the product you sell.

II. Origins: From Imperial Palaces to Post-War Reconstruction

The First Electric Lights (1887-1945)

To understand KEPCO, you have to start with a bigger idea: in Korea, electricity wasn’t just a convenience. From the very beginning, it was tied up with modernization, power, and national sovereignty.

The story opens in March 1887—not with a utility board meeting, but inside the royal compound. The first electric lights in Korea flickered on at Geongchung Palace within Gyeongbok Palace, brought there under the direction of King Gojong of the Korean Empire. He had seen what Western technology could do, and he wanted Korea to have it too.

But wanting electricity and building an electric system are two very different things. Seoul Electric Company emerged in this era, yet the hard reality was that Korea still needed outside expertise to make it work. American businessmen Henry Collbran and Harry Rice Bostwick were contracted to run Seoul’s streetcars, lighting, and telephone systems. It was an early glimpse of a pattern that would stick for decades: the most critical infrastructure often depended on foreign know-how.

By April 1900, Hansung Electric Company lit three streetlamps in Jongno—the first public lighting in Korea. Three lamps doesn’t sound like much. But it was a signal flare for what was coming. Electricity meant not only brighter streets, but the foundations of an industrial economy: transit, manufacturing, communications, and the machinery of a modern state.

Then Korea lost control of its own destiny. Under Japanese rule from 1910 to 1945, the peninsula’s power system expanded, but with a clear purpose: serving imperial needs. Major generation capacity was concentrated in the mountainous North, where hydroelectric resources were abundant. The South—more agricultural, less industrial—was left comparatively underpowered.

That imbalance would come roaring back after liberation.

Post-War Crisis & Nation-Building

When the Korean War began in 1950, it didn’t just split a country. It shattered an electrical system. South Korea was cut off from the North’s network and, with it, much of the peninsula’s generation capacity. The result was immediate and brutal: shortages, stalled industry, and cities trying to function without dependable power.

For the young Republic of Korea, building an integrated domestic electricity company wasn’t a policy preference. It was survival.

That’s where the modern KEPCO lineage really begins. In July 1961, the Korea Electric Power Company (KECO) was established under the Electricity Enterprises Act, bringing together three electric companies into one national entity. The timing mattered. General Park Chung-hee had taken power in a coup just two months earlier, and KECO fit neatly into the project that would define his rule: rapid, state-led industrialization.

Park’s premise was simple: without reliable, inexpensive electricity, there would be no “Miracle on the Han River.” Steel mills, shipyards, and electronics factories don’t run on speeches—they run on megawatts. And Korea, with virtually no domestic fossil fuel resources, had to build generation capacity at speed, from a weak base, while still importing the energy inputs it needed.

Foreign capital was essential, and structure mattered. International lenders like the World Bank were far more willing to finance large power projects if they could deal with one consolidated counterpart instead of a patchwork of local utilities. Creating KECO made Korea legible—and bankable—to the institutions that could fund a national build-out.

The results came fast. By April 1964, Korea had cleared limited electric power transmission for the first time since liberation. And by May 1968, the country’s generation capacity surpassed one million kilowatts.

But even as the grid stabilized and expanded, Korean planners were already looking ahead to the bigger, harder question: how does a resource-poor nation secure energy independence for the long run?

The answer they would pursue would shape KEPCO’s destiny—delivering some of its greatest triumphs, and setting up some of its most difficult contradictions.

III. The Government Takes Full Control & The Nuclear Bet (1978-1989)

Nationalization & The Nuclear Decision

By the late 1970s, South Korea’s electricity demand was surging with its export-manufacturing boom. Then the oil shocks of 1973 and 1979 hit, and the lesson landed with real force: a country that imported almost all its fuel could have its economy throttled by events an ocean away. So Korean planners started looking for an energy source that didn’t arrive on tankers.

In April 1978, that strategy took concrete form at Kori. KEPCO completed the first unit of the Kori Nuclear Power Plant, bringing nearly 600 megawatts online. It was Korea’s entry into the nuclear age—and an audacious bet for a country still in the middle of building its modern industrial base.

Kori-1 was built by America’s Westinghouse. At this point, Korea was a buyer, not a builder—dependent on foreign design, foreign construction experience, and foreign expertise. But the goal was never to stay a customer. From the beginning, nuclear power was treated not just as generation capacity, but as an opportunity to learn a complex technology stack that very few countries could master.

That ambition lined up with a bigger shift in how the state wanted to run the grid. In January 1982, the Korea Electric Power Corporation was formally launched. The renaming wasn’t just a rebrand. President Chun Doo-hwan pushed through the Korea Electric Power Corporation Act, dissolved the existing structure, and remade the company into a fully public corporation—because, in his view, electricity was fundamental to daily life and national stability.

With the government firmly in the driver’s seat, nuclear construction accelerated. Contracts were awarded for a wave of new plants, with plans for eight additional units to come online by the end of the 1980s. Through the decade, KEPCO kept adding nuclear capacity, and by its close Korea had nine nuclear plants on the grid.

The Technology Transfer Strategy

The part that made Korea’s nuclear program different wasn’t that it built reactors. Lots of countries did that. It was how it bought them.

KEPCO steered contracts toward bidders willing to include technology transfer. The point wasn’t simply to import megawatts. It was to import capability—to avoid the trap where a country can operate nuclear plants, but remains permanently dependent on the original vendor for upgrades, maintenance know-how, and key components.

After the first three units, Korean firms increasingly took over the construction work on subsequent plants. It was a deliberate learning-by-doing playbook: work alongside experienced foreign contractors, absorb everything, and steadily bring more of the work—and therefore the expertise—inside the Korean industrial system.

The pivotal moment came in 1987. KEPCO set out to create a standard Korean reactor design and selected the System 80 design from Combustion Engineering. Combustion Engineering won by agreeing to full technology transfer. In hindsight, it’s hard to overstate how important that concession was: it turned Korea from a customer into a future competitor.

And this was never only about keeping the lights on. Technology transfer meant Korean companies could ultimately build the parts that matter—pressure vessels, steam generators, turbines, control systems—and develop a deep bench of nuclear engineers and operators. In other words, it created an ecosystem.

It also fit neatly into the broader industrial strategy of the era: pick strategic industries, back national champions, and extract know-how from foreign partners. In cars, that approach produced Hyundai. In electronics, Samsung. In steel and heavy industry, POSCO and Doosan. In nuclear, it laid the groundwork for what would eventually become the APR-1400—Korea’s homegrown reactor design and, later, its export ticket to the world.

Going Public: The Partial Privatization

Then KEPCO made a move that looks contradictory at first glance. Even as the government tightened its grip on the strategic direction of the power system, it pushed KEPCO toward the market.

KEPCO listed on the Korea Composite Stock Price Index on August 10, 1989, selling about 21 percent of the company to public shareholders. In 1994, it also listed on the New York Stock Exchange.

Why do that if you view electricity as too important to leave to market forces? Because the listing did several things at once. It raised capital. It forced a higher level of transparency and financial discipline. And it sent a message to global investors that Korea was becoming a more market-oriented economy—an important signal as the country sought deeper integration into global institutions.

But the state never gave up the most sensitive lever: pricing. The government continued to control key decisions, especially the policy of keeping electricity rates low for industrial customers and other groups, including farmers, to support growth and ease burdens. That helped power the “Miracle on the Han River.” It also constrained KEPCO’s ability to fund the capacity expansions it was being tasked to deliver—and planted the seed of a future crisis.

The result was a company built out of compromises: public shareholders alongside government control; the optics of market discipline alongside political rate-setting; expectations of profitability alongside mandates to serve national development. The contradictions didn’t break KEPCO in the 1980s. In fact, in that era, they looked like a feature, not a bug.

For the moment, the flywheel was spinning. Korea’s growth was explosive, engineers were building at full tilt, and KEPCO was supplying the electricity that kept the factories humming.

IV. The Asian Financial Crisis & The Aborted Restructuring (1997-2004)

The IMF Demands Privatization

The 1997 Asian Financial Crisis hit Korea like a financial asteroid. The won plunged, big conglomerates toppled, and the country was forced to accept a $55 billion bailout from the International Monetary Fund—then the largest IMF program on record.

That bailout came with strings. One of the loudest: privatize.

From that moment on, “KEPCO privatization” became a recurring political slogan in South Korea. Starting in 1998, Korea began trying to transform its electricity industry from a state-run monopoly into something closer to a competitive market—mirroring reforms that were sweeping across both developed and developing countries at the time.

Up to that point, the structure had been simple: KEPCO dominated everything. Since 1961 it had been vertically integrated across the entire value chain—generation, transmission, and distribution. To the IMF, steeped in the Washington Consensus playbook of the era, this looked like a textbook case for unbundling and liberalization.

The pitch was straightforward. Split up KEPCO’s functions. Create multiple power generators that would compete with one another. Build a market where electricity could be bought and sold transparently. Let private capital come in, modernize the system, and—in theory—make the whole sector more efficient.

The Restructuring Plan

Korea’s push to restructure the power industry had started in the mid-1990s, but it became formal policy with the Act on the Promotion of Restructuring the Electric Power Industry, proclaimed on December 23, 2000.

KEPCO’s generation business was carved up. Its non-nuclear generation operations were split into five regional companies: Korea South-East Power, Korea Southern Power, Korea Midland Power, Korea Western Power, and Korea East-West Power.

Then came the crown jewel. In 2001, KEPCO created Korea Hydro & Nuclear Power—KHNP—and transferred all nuclear and hydroelectric generation into it, representing close to 40 percent of the group’s total generation capacity.

The endgame was clear: these six generation companies would eventually be privatized and sold to investors who would bring capital, expertise, and the discipline of a true market. Korea also created the Korea Power Exchange, where generators would compete to supply electricity. At least on the surface, the first phase of liberalization was underway.

The Great Reversal: Why Privatization Failed

And then the whole project stalled.

Resistance built quickly, especially from unions. In 2002, union members across KEPCO’s generation subsidiaries launched a six-week strike to protest the proposed privatization, bringing huge parts of the power sector into crisis mode and turning reform into a national fight.

But labor opposition was only the visible obstacle. The deeper problem was structural: a privatized market would collide head-on with Korea’s pricing reality.

For privatization to work, prices would have to move toward cost. That meant raising rates—especially the artificially low industrial rates that had been treated for decades as a kind of national industrial policy. Korea’s export machine had grown up alongside cheap power. Companies like Samsung, Hyundai, LG, POSCO, and countless suppliers had built global cost advantages partly because electricity was kept intentionally affordable. Meaningful industrial rate hikes weren’t just politically painful—they threatened the broader growth model.

So in 2004, the Korean government suspended electricity market reform, effectively halting the plan to divest and privatize KEPCO’s generation segment.

The system that remained was an uneasy compromise. KEPCO stayed a transmission and distribution monopoly. The six generation subsidiaries were separated in 2001, but no further privatization followed. Competition existed in the wholesale market, but KEPCO remained the single buyer and the sole retail seller, with regulated tariffs still setting the boundary conditions for the entire sector.

The result was a structure stuck in the middle—neither fully public nor genuinely private. And it would prove stubbornly durable.

For KEPCO, that durability came at a cost. The company carried expectations of commercial performance, but it still lived under political constraints—especially around pricing. It was a limbo that looked manageable in stable times, and dangerously fragile when conditions turned.

It would take another shock to expose just how fragile.

V. The UAE Deal: Korea Becomes a Nuclear Exporter (2009)

The Landmark Contract

December 2009 was a watershed moment for Korean industry—one of those wins that changes how a country sees itself.

That month, Emirates Nuclear Energy Corporation (ENEC) awarded a consortium led by KEPCO a $20 billion contract to build the UAE’s first nuclear power plant. The project would be four APR-1400 reactors, designed to deliver a combined 5,600 megawatts—enough to supply up to a quarter of the country’s electricity needs.

Seoul called it the largest foreign order South Korea had ever won. And it wasn’t just the size. It was who KEPCO beat to get it: France’s Areva, and a rival team backed by General Electric and Hitachi—brands with decades more nuclear export history and far deeper roots in the global industry.

How Korea Beat the Giants

So how did Korea, a country that had been buying turnkey reactors in the 1970s, outbid the incumbents?

The UAE deal was proof that South Korea had completed the transition from customer to supplier—able to compete with the most experienced nuclear builders in the world.

A few ingredients mattered.

First: three decades of relentless repetition at home. By 2009, Korean companies had built and operated enough reactors domestically to develop a reputation for predictable execution. At a time when nuclear projects in many Western countries were becoming synonymous with delays and overruns, Korea’s track record looked unusually steady.

Second: cost. Korean firms could deliver at a price point that was hard for Western competitors to match. Lower labor costs helped, but the bigger advantage was an industrial machine built over years: an integrated supply chain, standardized designs, and teams that had done the work over and over again.

Third—and most importantly—was what that 1980s technology-transfer strategy had been quietly building toward. The APR-1400 wasn’t just a licensed design with a new label. It was the culmination of Korea’s push to internalize nuclear know-how and turn it into something it could own, operate, and sell.

KEPCO would later argue that the UAE chose Korea for a simple bundle of reasons: strong performance, lower costs, and faster construction timelines.

The Barakah Success Story

The project became the Barakah nuclear power plant in Abu Dhabi—jointly developed by ENEC and KEPCO. It was the UAE’s first nuclear power project, and a milestone for the region: the first commercial nuclear plant in the Arab world.

ENEC’s December 2009 award covered the design and construction of four APR-1400 units. The KEPCO-led consortium included KHNP, Hyundai, Samsung, Doosan, Korea Power Engineering Company, and Korea Plant Service and Engineering (KPS).

And KEPCO wasn’t trying to be a one-and-done contractor. It also signed a $49.4 billion agreement to operate the facility for 60 years, with expectations of significant additional earnings from long-term joint operations. Structurally, KEPCO ended up with an 18% stake in ENEC’s operating subsidiary, Nawah Energy Company, with ENEC holding the remaining 82%.

Then came the real test: delivery.

Barakah’s units entered commercial service one by one—Unit 1 in April 2021, Unit 2 in March 2022, Unit 3 in February 2023, and Unit 4 in September 2024.

At full production, Barakah generates about 40 terawatt-hours of electricity a year—up to a quarter of the UAE’s demand. ENEC has said the plant avoids 22.4 million tonnes of carbon dioxide emissions annually, contributing roughly 24% toward the UAE’s 2030 decarbonisation target.

For “Korea Inc.”, Barakah wasn’t just a big overseas project. It was validation. In a single deal, Korea went from being a nation that once imported nuclear capability to one exporting it—sending engineers, builders, and operators abroad to run a system at global scale.

And once you’ve proven you can do that, the world starts taking your calls. The doors opened elsewhere—though not without drama.

VI. The Nuclear Whiplash: Moon's Phase-Out to Yoon's Revival (2017-2024)

Moon Jae-in's Nuclear Exit Policy

Just as Korean nuclear technology was proving itself on the world stage, politics back home started pulling the floor out from under the industry that had taken decades to build.

Moon Jae-in became president in May 2017. A month later, at the shutdown ceremony for Kori-1—South Korea’s first commercial reactor—Moon said he would “review the policy on nuclear power plants entirely,” and that the country would “abandon the development policy centred on nuclear power plants and exit the era of nuclear energy.”

It was a sharp reversal. In the shadow of the Fukushima Daiichi disaster in Japan, concerns about earthquake risk in South Korea, and a series of nuclear-related scandals, Moon’s administration embraced a gradual phase-out of nuclear power.

The shift became tangible almost immediately. In May 2017, Korea Hydro & Nuclear Power (KHNP) announced it had instructed KEPCO Engineering & Construction to suspend design work for two planned APR-1400 units at Shin Hanul 3 and 4. Moon also said plans for new reactors would be cancelled, and that existing units would not have their operating periods extended beyond their design lifetime.

The practical consequences were sweeping. Wolsong Unit 1 was shut down ahead of schedule. Construction of six nuclear power plants was canceled. And the operating periods of 14 plants would not be extended past their final dates. The goal was to cut the number of nuclear power plants in South Korea from 24 to 14 by 2038.

The backlash was immediate and intense. Around 410 professors—including faculty from Seoul National University and KAIST—called on the government to “immediately halt the push to extinguish the nuclear energy industry that provides cheap electricity to the general public.”

The criticism wasn’t only domestic. In July 2017, an open letter signed by 27 international scientists and conservationists, including climate scientist James Hansen, urged Moon to reconsider. Their warning was blunt: if South Korea walked away from nuclear, the world would risk losing a proven supplier of large-scale, low-carbon power at exactly the moment the climate challenge demanded more of it.

Inside the industry, the mood turned from pride to paralysis. The nuclear supply chain runs on long lead times and steady throughput. When the policy flipped, thousands of jobs suddenly looked precarious, and manufacturers like Doosan—after investing billions into nuclear component capability—were left staring at an existential question: what happens to a world-class industrial base when the home market decides it no longer wants the product?

The Complete Policy Reversal Under Yoon

Then, almost as quickly as the phase-out took hold, the pendulum swung back.

President Yoon Suk-yeol took office in May 2022 and pledged to reverse Moon’s nuclear phase-out. He had campaigned as explicitly pro-nuclear, promising to resume plant construction, develop small modular reactors, and keep nuclear at around 30 percent of electricity generation.

In July 2022, Yoon pushed for a rapid restoration of Korea’s “nuclear power plant ecosystem.” The Minister of Trade, Industry and Energy laid out plans to revitalize the industry, including restarting work related to Shin Hanul 3 and 4.

“We are now in the midst of a nuclear renaissance,” Yoon declared.

By 2023, the reversal was formal: South Korea resumed nuclear plant construction and set a target to expand nuclear’s share of electricity generation to 34.6% by 2036.

And the whiplash didn’t stop at Korea’s borders. The government was again talking about nuclear exports at scale, with plans to export 10 nuclear plants by 2030. Countries including Poland, the Czech Republic, Turkey, and Romania were floated as potential customers for Korea’s next major export wins.

In July 2024, KHNP was selected as the preferred bidder for a 24 trillion won ($17.3 billion) project to build nuclear power plants in the Czech Republic—a potential landmark, as it would be Korea’s first major reactor export contract since the 2009 Barakah deal in the UAE.

But closing the Czech project turned into a reminder that in global nuclear, nothing is ever just engineering. The Czech anti-trust authority temporarily blocked the contract after challenges from Westinghouse Electric Corp. and France’s EDF.

In January 2025, Westinghouse announced a global settlement agreement with KEPCO and KHNP to resolve an outstanding intellectual property dispute. The settlement was framed as a way for both sides to move forward with certainty on new reactor deployments—and even opened the door to future cooperation on nuclear projects worldwide.

On June 4, 2025, the contract for new nuclear capacity at the Dukovany site in the Czech Republic was signed, hours after the Supreme Administrative Court annulled a regional court’s injunction that would have stopped it. The total cost was set at 407 billion koruna ($18.7 billion), with the first new reactor expected to enter operation by 2036.

Even that victory came with controversy. The settlement with Westinghouse reportedly included provisions that would give Westinghouse a right to assess whether Korean companies were technically independent before competing for international nuclear projects. KHNP would be banned from pursuing nuclear projects in North America, Britain, Japan, Ukraine, and the European Union—with the exception of the Czech Republic. KHNP also reportedly agreed to buy $650 million worth of Westinghouse goods and services for every reactor it exports, and to pay $175 million per reactor in licensing fees, over the next half-century.

So yes, Korea was back in the export game. But it was doing it while navigating the fine print of legacy technology, geopolitics, and who really owns the right to build what.

And that’s the core tension of this era: rapid pendulum swings in nuclear strategy fueled political conflict, public debate, and deep uncertainty across the industry. Each new administration carried the risk of another abrupt reversal. For a business that requires decades-long planning horizons, that kind of instability isn’t a nuisance. It’s a structural threat.

VII. The Financial Crisis: Selling Power Below Cost (2021-2024)

The Perfect Storm

While nuclear policy fights dominated headlines, a quieter problem was building inside KEPCO’s income statement—one that would bring the company to the edge.

Between 2021 and 2023, global energy prices surged, turbocharged by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. KEPCO kept doing what it had always been expected to do: provide stable electricity at politically acceptable prices. The problem was that those prices were no longer anywhere close to the cost of producing power.

The underlying exposure was baked into Korea’s energy reality. In 2022, KEPCO generated about 55% of its electricity from fossil fuels, with roughly three-quarters of that coming from thermal coal-fired generation. South Korea imports more than 90% of its energy, and most of it is fossil fuel.

So when LNG and coal spiked, KEPCO’s costs didn’t just rise—they jumped. In a normal utility, that pain eventually gets passed through to customers. KEPCO couldn’t do that. Retail electricity tariffs required government approval, and policymakers were wary of authorizing big increases that could ripple into inflation and household bills.

The outcome wasn’t a mystery. It was arithmetic: buy fuel at global prices, sell electricity at regulated prices, and absorb the gap as losses.

Record-Breaking Losses

You can see the moment the economics snapped. In 2020, KEPCO posted a consolidated operating profit of 4.1 trillion won. Starting in 2021, it flipped into the red: an operating loss of 5.8 trillion won in 2021, then a staggering 32.7 trillion won in 2022, followed by another 4.5 trillion won loss in 2023.

Over those three years, KEPCO accumulated more than 43 trillion won in losses.

To stay afloat, it borrowed—heavily. In 2023, amid the peak of the global energy crisis, KEPCO came close to bankruptcy, with total debt reaching 203 trillion won ($151 billion). By the end of the following year, total debt hit a record 205.18 trillion won, up 2.73 trillion won year over year.

The debt didn’t just sit there; it started compounding. Consolidated interest costs, which were 2 trillion won in 2020, climbed to 4.5 trillion won by 2023. KEPCO was borrowing to cover operating losses, then borrowing more to pay interest—a utility version of a debt spiral.

As the company approached a heavy bond maturity wall of US$39 billion across 2024 and 2025, bondholders had reason to worry. If refinancing tightened, a government backstop started to look less like a hypothetical and more like the likely endgame.

The Political Trap: Why KEPCO Can't Raise Prices

At the center of the mess was something that sounds like a national point of pride: Korea’s cheap electricity.

Because KEPCO is state-owned, it can’t simply set prices based on cost. It has to consult with the government. And fearing backlash from households and broader inflation pressure, the government was reluctant to approve significant increases—even as KEPCO’s losses ballooned.

The international comparison made the gap hard to ignore. Korea’s electricity price was 149.8 won per kilowatt-hour. Japan’s was 318.3 won per kWh. Australia’s was 311.8 won, Italy’s 335.4 won, and Britain’s 504.3 won.

In other words, Korea was paying less than half what many comparable advanced economies paid. That difference didn’t disappear—it showed up as debt on KEPCO’s balance sheet.

Analysts pointed to South Korea’s regulated power pricing mechanism as a core driver of KEPCO’s mounting debt. The dynamic even had a label: “Pseudo Competitiveness”—low, politically set retail tariffs sitting on top of a wholesale market structure that wasn’t truly competitive.

And the politics got even messier once you look at who benefited most. Industrial demand made up only 1.7% of total users, but accounted for 53.2% of electricity consumption. Large-scale industrial users were just 0.1% of users, yet consumed 48.1% of the electricity used.

That meant the biggest winners from cheap power were also the biggest names in the Korean economy—Samsung, SK Hynix, Posco, LG. They were the country’s export champions, central to the trade surplus and the national growth story. Raising their power costs risked weakening Korea’s competitiveness abroad.

So KEPCO was stuck. The company was expected to operate like a business, but it sold its product on terms set by politics. It couldn’t stop buying fuel at global prices—and it couldn’t reliably charge customers enough to cover them.

The Turnaround Efforts

Eventually, the math forced movement.

KEPCO announced a package of rate hikes and restructuring, aiming to work through a debt crisis of around 201 trillion won ($153 billion). The plan leaned on asset sales and workforce reductions: more than 2,000 employees would be reduced, assets would be sold, a voluntary early retirement program was implemented, high-ranking officials returned part of their wage increases, and the corporate headquarters organization was cut by 20 percent.

On the pricing side, the government finally allowed targeted increases where the politics were easier. In October 2024, South Korea raised industrial electricity rates by 9.7% starting October 24, 2024—leaving household rates untouched. The average increase was 9.7 percent overall, with a 10.2 percent hike for large-scale industrial users and 5.2 percent for small and medium-sized enterprises.

Those moves helped produce a real swing in results. KEPCO was forecast to post an operating profit of 8.86 trillion won ($6.07 billion) for 2024, reversing an operating loss of 4.57 trillion won in 2023. In Q3 2025, it reported strong performance again, with consolidated operating profit reaching KRW 11.54 trillion. Sales revenue rose 5.5% year over year to KRW 73.75 trillion, driven mainly by a 5.9% increase in electricity sales revenue.

But even with improved earnings, the company’s starting point was daunting. As of end-June 2025, accumulated debt stood at 206.2 trillion won ($139.2 billion). Digging out would take years of sustained profits—and, crucially, a political willingness to keep prices closer to reality.

The turnaround was real. It just wasn’t secure.

VIII. The Current State: A Utility at a Crossroads

Corporate Structure Today

Today, KEPCO is less a single company than the center of a sprawling system. It sits above six power generation companies, four subsidiaries in related business areas, and stakes in four affiliated companies. And inside that structure is the crown jewel: Korea Hydro & Nuclear Power (KHNP), which operates 25 nuclear power plants and 37 hydropower plants in South Korea, totaling 30,054 MW of capacity.

Put differently: KHNP runs the country’s biggest low-carbon workhorses, and together those nuclear and hydro assets supply roughly 31.56% of South Korea’s electric power.

Zoom out one level, and you see the full scale of the KEPCO group. As of December 31, 2023, it had 83,235 MW of installed generating capacity across 794 generation units—spanning nuclear, oil, coal, liquefied natural gas, hydro, wind, and solar.

What’s striking is that, despite the losses and the debt spiral fears, the credit markets still treat KEPCO like a high-grade borrower. As of September 2024, S&P rated KEPCO AA, and Moody’s rated it Aa2 with a stable outlook. Those are investment-grade ratings that are higher than KEPCO’s standalone financials would normally justify—and they exist largely because investors assume the government won’t let the country’s power utility fail.

Moody’s made that explicit in May 2023, when it cut KEPCO’s baseline credit assessment from Baa2 to Baa3—right to the edge of junk status. Yet it still kept KEPCO’s long-term debt at Aa2, seven notches above that baseline, effectively tying KEPCO’s true rating to the sovereign’s willingness to step in rather than to the underlying strength of the business.

International Presence

KEPCO’s story isn’t confined to the Korean peninsula. Beyond Barakah in the UAE and the Czech nuclear push, it has built a meaningful overseas footprint. In 2010, a KEPCO-led consortium won a contract to build and operate the Norte II combined-cycle gas power plant in Mexico. In 2011, KEPCO took a 40% stake in Jamaica Public Service.

More broadly, KEPCO owns or co-owns power generation operations in places including Mexico, the Philippines, Saudi Arabia, and Jordan.

And in May 2024, ENEC and KEPCO signed an agreement to explore co-investing in nuclear plants globally and to identify cooperation opportunities for third-country clean energy projects—explicitly aiming to replicate the Barakah model elsewhere.

Political Turmoil and Uncertainty

If KEPCO’s financial situation is shaped by politics, then the country’s political shocks matter—immediately.

On December 14, 2024, South Korea’s National Assembly impeached President Yoon Suk Yeol after passing an impeachment bill with 204 of 300 members voting in favor. The impeachment followed Yoon’s declaration of martial law on December 3, 2024.

On April 4, 2025, the court unanimously upheld the impeachment in an 8–0 decision, removing Yoon from office.

For the nuclear sector—and for KEPCO’s long-term planning—this wasn’t just drama in Seoul. While the country waited for the final ruling, the industry hung in the balance. Yoon had been the driving force behind a major pro-nuclear revival. But leaders in the opposition Democratic Party, including Yoon’s predecessor and the party’s candidate to succeed him, were decidedly anti-nuclear.

Then came the election. Lee Jae-myung of the Democratic Party of Korea (DPK) won a landslide victory on June 3, 2025, taking office with a strong popular mandate and comfortable control of the National Assembly.

And yet, in a twist that shows how complicated the energy debate has become, Lee—despite his earlier posture—has so far acknowledged the importance of nuclear power and signaled that it should remain part of Korea’s energy mix alongside renewables, framing it as necessary for sustainable supply and high-tech development needs like artificial intelligence.

International partners were watching closely. Czechia, for its part, stated that construction of its nuclear plants would not be affected by South Korea’s political crisis.

IX. Investment Framework: Bulls, Bears, and Key Metrics

The Bull Case

There is a real argument that KEPCO is better positioned for the next decade than it looked at the bottom of the 2022–2023 crisis. The reasons are less about a sudden reinvention, and more about tailwinds that finally line up with what Korea has spent decades building.

Nuclear Renaissance as Tailwind: After Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, energy security moved from an abstract concept to a national priority across Europe. That shift has rehabilitated nuclear power in policy circles that had written it off. In March 2024, the Nuclear Energy Summit produced a declaration calling to “fully unlock” nuclear energy’s potential. At COP28, the United States led a coalition pledging to “triple nuclear energy by 2050,” joined by 25 countries—including South Korea and the Czech Republic. For a country that can actually build and run reactors, this kind of momentum matters.

Proven Execution Capability: Nuclear is a credibility business. Everyone promises a clean, safe, on-time megaproject; very few deliver. Barakah is KEPCO’s calling card: a complex first-of-its-kind project for the UAE, completed on budget and relatively on schedule by nuclear standards. That track record is a genuine competitive advantage, and it’s hard for rivals to replicate quickly.

Pricing Power Gradually Improving: For years, KEPCO’s biggest problem was simple: the price didn’t follow the cost. Since 2022, to improve financial soundness, KEPCO raised the average electricity rate repeatedly, resulting in a combined increase of about 50%. It still hasn’t fully closed the gap, but the direction finally changed—and in a regulated business, direction is half the battle.

Government Backing: KEPCO’s capital structure only really makes sense if you assume the state won’t let it fail. As a majority state-owned enterprise, KEPCO effectively benefits from government credit support. In practice, that has meant bond investors treating it as a government-adjacent issuer, with the government guaranteeing recurring interest payments and repayment of principal at maturity.

The Bear Case

KEPCO’s upside comes with very real risks—and they’re not the kinds that management can simply “execute” its way out of.

Political Risk: KEPCO’s operating environment is shaped by elections. The industry has already lived through dramatic nuclear policy reversals between administrations, and that matters because nuclear projects run on decade-plus timelines—often 10 to 15 years. If the political cycle reliably flips priorities every five years, long-term planning becomes a gamble, not a strategy.

Structural Pricing Problem: The core model remains fragile as long as KEPCO can’t set prices at levels that consistently reflect costs. When a company can operate indefinitely under political protection—without risking true default—it also risks the downsides of that protection: chronic underperformance, weak incentives, and a lack of thoughtful long-term investment discipline.

Debt Overhang: Even if operating performance improves, the accumulated debt burden constrains KEPCO’s choices for years. Interest payments absorb cash that could otherwise go into grid upgrades, renewable integration, or efficiency improvements. In a capital-intensive industry, that opportunity cost is a real strategic problem.

Export Market Constraints: The Westinghouse settlement adds a hard-to-ignore constraint layer. Disclosed terms restricted KHNP to pursuing nuclear projects in 12 designated countries—including the Philippines, Vietnam, Kazakhstan, Morocco, Egypt, Brazil, Argentina, Jordan, Turkey, the United Arab Emirates, Saudi Arabia, and South Africa—while barring it from new deals in North America, Britain, Japan, Ukraine, and the EU, except for the Czech Republic.

Porter's Five Forces Analysis

Threat of New Entrants: Essentially zero at home, given the regulated monopoly structure and massive capital requirements. Low in nuclear exports as well, thanks to technological barriers and regulatory complexity.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers: Moderate. Global markets for LNG, coal, and uranium are broadly competitive, but Korea’s geography limits flexibility in import infrastructure. And in gas, KOGAS dominates about 80% of South Korea’s market, creating procurement rigidity.

Bargaining Power of Buyers: Politically strong, even if technically dependent. Industrial customers have outsized influence and have resisted cost-reflective pricing for decades.

Threat of Substitutes: Rising over the long run—especially distributed solar and battery storage, which can chip away at grid demand. That said, near-term AI-driven electricity demand could partially offset this.

Competitive Rivalry: Essentially absent domestically. In export markets, rivalry is intensifying—particularly from China (which dominates global nuclear construction starts), Russia (complicated geopolitically after Ukraine), France (a traditional nuclear heavyweight), and the United States (seeking to revive nuclear ambitions).

Hamilton Helmer's 7 Powers Analysis

Scale Economies: Strong. Nuclear generation has huge fixed costs and low marginal costs; transmission behaves like a natural monopoly.

Network Effects: Weak. Electricity is a commodity product, not a network-driven one.

Counter-Positioning: Moderate. KEPCO’s nuclear-heavy capabilities may differentiate it from Western utilities that exited nuclear and lost institutional depth.

Switching Costs: Very strong in transmission and distribution (by design), weak in generation (which could theoretically be opened to competition).

Branding: Moderate. Korea’s nuclear brand gained credibility through Barakah.

Cornered Resource: Weak. KEPCO doesn’t control unique proprietary inputs.

Process Power: Potentially strong. KEPCO’s record—high capacity factors, comparatively low construction costs, and shorter construction timelines—suggests accumulated institutional capability that is difficult to copy.

Key Performance Indicators to Monitor

1. Price-to-Cost Ratio: The most important single metric. It captures the gap between what KEPCO charges and what it costs to produce electricity. Until this ratio approaches 1.0 sustainably, the business remains structurally vulnerable. The gap narrowed in 2024–2025 due to rate increases and falling fuel prices, but it can widen again quickly.

2. Debt-to-EBITDA Ratio: With debt above 200 trillion won, the pace of deleveraging determines financial flexibility and sensitivity to interest rates. A meaningful signal of normalization would be a decline below 10x.

3. Nuclear Export Pipeline: The pace and quality of international contracts show whether KEPCO’s nuclear capabilities can be monetized abroad. Every win or loss is a referendum on Korea’s competitiveness in a market where credibility compounds.

Material Risks and Regulatory Overhangs

EU State Aid Investigation: The European Commission raised concerns about the state-aid structure for the Czech nuclear project—citing the scale of support (including 23–30 billion euro loans and a 40-year contract) and arguing it may shift too much risk to the state and distort competition. That could delay or complicate the Czech project.

Westinghouse Settlement Terms: The settlement’s full terms remain confidential. But the disclosed export restrictions and mandatory purchases from Westinghouse create ongoing obligations and strategic constraints that may not be fully reflected in market expectations.

Political Uncertainty: Even with more pragmatic signals from the new administration, the risk of another nuclear policy reversal can’t be dismissed. Any meaningful retreat would hit KEPCO twice—undermining domestic throughput for the nuclear supply chain and weakening export credibility abroad.

Conclusion: The Power Behind Tomorrow's Korea

KEPCO is the living embodiment of modern state capitalism’s contradictions. It’s a tool of national development and a publicly traded company whose shareholders have absorbed years of pain. It’s a world-class nuclear exporter—and, at home, a utility that has repeatedly been forced to sell power below cost. It’s a monopoly that, in the one place it matters most, has almost no pricing power.

And that’s why KEPCO’s story ends up being bigger than KEPCO. It raises the uncomfortable questions that every country is going to face in the energy transition: can a state-owned utility modernize fast enough without breaking its balance sheet? How do you balance affordability with solvency? Can you run industrial policy through the electric bill and still expect market discipline to show up when it counts?

For investors, KEPCO is a rare mix of protection and frustration. There is a floor under the downside because the Korean state can’t let the grid operator fail. But the same politics that provide that backstop are also the politics that make cost-reflective pricing so hard. The return to operating profitability is real progress, but it doesn’t magically erase the structural constraint: KEPCO still doesn’t fully control its own economics.

The nuclear export business is the wildcard. If Korea can turn Barakah-style execution into a repeatable global pipeline, the upside could be meaningful. But it’s a business where contracts are political, timelines are long, competitors are getting sharper, and the rules can change midstream.

So the hardest question is also the most fundamental one: will Korean society ultimately accept the true cost of electricity? For decades, low prices were a feature, not a bug—an invisible subsidy that helped fuel industrialization. Now that strategy has collided with global fuel markets, interest costs, and accumulated debt. One way or another, something has to give.

The lights still burn across Seoul tonight. The factories still hum. The miracle still runs. But the company powering it all is staring at a choice: keep absorbing the contradictions—or resolve them in a way that can sustain the next forty years, not just explain the last.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music