Hyundai Mobis: The Hidden Engine of Korea's Automotive Empire

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

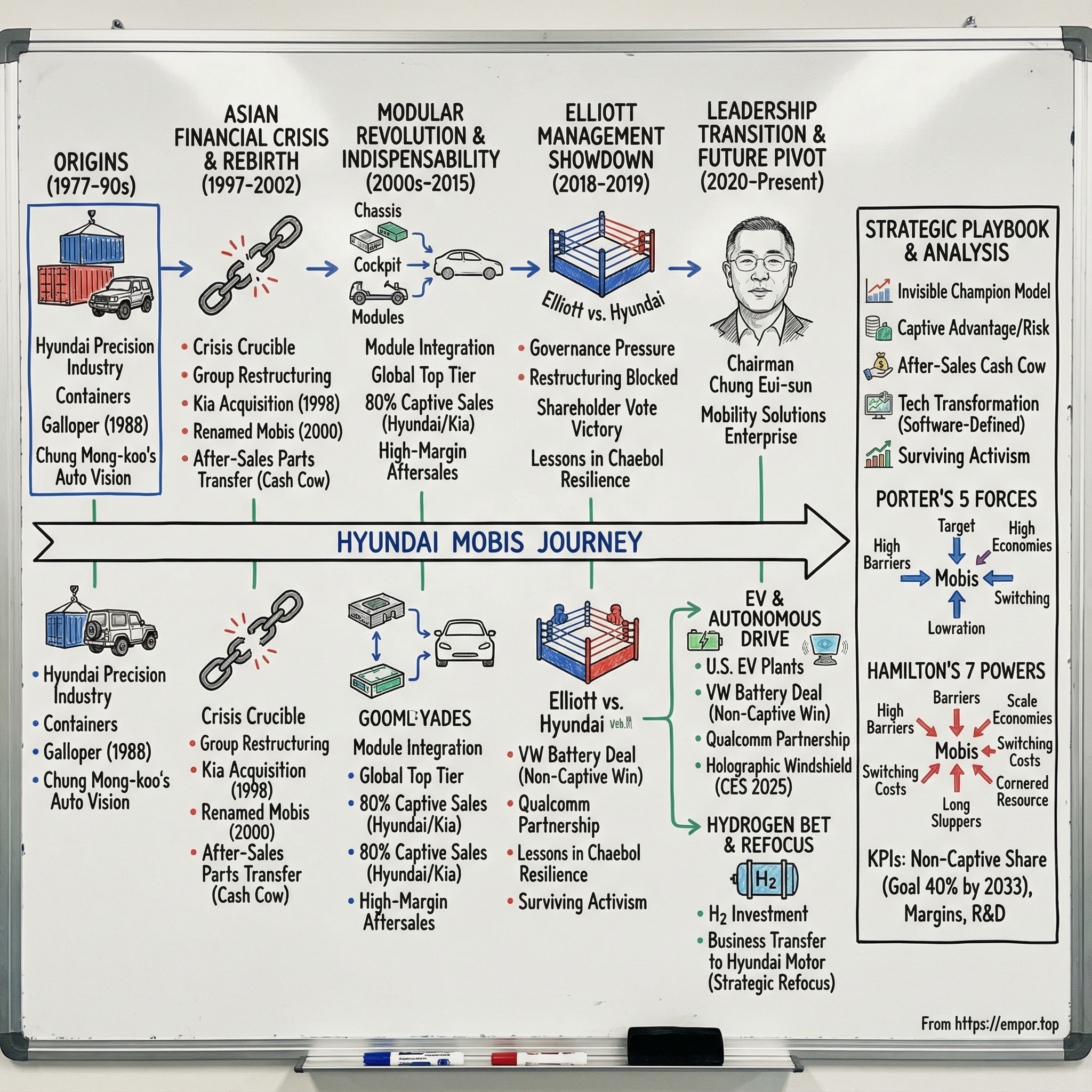

In Seoul’s glass-and-steel skyline, there’s a company pulling in more than forty billion dollars a year that most drivers will never name. Hyundai and Kia are the badges people recognize—from Atlanta to Auckland. But behind those badges sits the supplier that makes the cars possible, quietly shipping out everything from chassis modules to the kind of futuristic cockpit tech that turns a windshield into a display.

That company is Hyundai Mobis.

As of mid-2025, Hyundai Mobis carried a market capitalization of about $19.4 billion, with trailing twelve-month revenue of roughly $42.4 billion. By scale, it belonged in the top tier of global auto suppliers. By mindshare, it was nearly invisible. It even ranked among the world’s largest suppliers—often cited around sixth—competing in the same arena as Bosch and Continental in Europe, Denso and Aisin in Japan, and Magna in North America.

Mobis is headquartered in Seoul, but culturally it’s the less famous third child in the Hyundai-Kia family. And like Denso and Aisin are to Toyota, Mobis isn’t an automaker. It’s the parts and systems company that sits just offstage—designing, building, and delivering major chunks of the vehicle for Hyundai and Kia, deeply embedded in the group’s internal ecosystem.

So here’s the question that makes this story worth telling: how did a company that started out making shipping containers become the technological backbone of Asia’s biggest automotive powerhouse—and then survive one of the most dramatic activist-investor battles in modern Korean corporate history?

Along the way, we’re going to hit three big ideas. First, the chaebol system—the uniquely Korean mix of family control, cross-shareholdings, and political-economic history that shapes what companies can do, and what they can’t. Second, Mobis’s transformation from heavy manufacturing into a mobility technology business. And third, what happens when Wall Street’s playbook—led by one of its most feared activists—collides with Korean corporate governance.

And if you’re looking at this through an investor lens, Mobis poses a final intrigue: it has captive demand from one of the world’s most important automaking groups, yet it has traded at a meaningful discount to many global peers. Is that discount a rational price for governance risk and group complexity—or the kind of opportunity that only shows up when a great business hides in plain sight?

II. The Chaebol Context: Understanding Hyundai Group

To understand Hyundai Mobis, you have to understand the system that raised it: the Korean chaebol. The word itself is basically the whole story—“jae” meaning wealth, and “bol” meaning clan. These aren’t just big corporations. They’re dynasties, built around family control, stitched together across dozens of affiliates, and powerful enough to shape entire industries.

A chaebol is typically owned and run by the founding family and its relatives in a highly centralized way. Korean law sets a baseline expectation here: at least 30 per cent of a chaebol’s ownership must sit with the family or their relatives. When that’s the setup, management tends to follow the same logic—top-down, tightly controlled, and oriented around the family’s long-term vision.

That’s fundamentally different from Japan’s keiretsu model. In a keiretsu, the companies are more decentralized, often run by professional management rather than the founding family, and tied together through relationships that include meaningful equity stakes held by financial institutions. Put simply: a Toyota supplier like Denso may have to balance the preferences of multiple major stakeholders, including banks. In Hyundai’s world, when the Chung family wants a direction, that direction tends to win.

Korea’s biggest chaebol names—Samsung, Hyundai, and LG—sit at the center of the country’s modern economic story, and all have historically had strong connections to the government. And that matters, because the chaebol model isn’t just a business structure. It’s a national development strategy that became permanent.

The mechanism that makes this system work—especially when direct family ownership isn’t enough to control everything outright—is cross-shareholding. Affiliates own pieces of each other, forming interlocking rings of ownership that consolidate control, create internal stability, and make the group hard to attack from the outside. It also means ownership is always in motion, shifting with market conditions, investor pressure, and whatever restructuring best protects control.

With Hyundai Motor Group, that web is particularly dense. As of December 2024, Hyundai Mobis was the largest shareholder in Hyundai Motor Company, holding about 22.36% of the shares. At the same time, Hyundai Motor Company owned roughly 21.43% of Hyundai Mobis, and Kia held around 17.28%. Layer in the Chung family’s personal stakes—Chung Mong-koo and Chung Eui-sun most notably—and you get the real picture: not a straight line of ownership, but a loop.

In fact, Hyundai Motor Group has been described as having two main rings of cross-shareholding. One links Hyundai Motor, Kia, and Hyundai Mobis. The other connects Hyundai Motor, Kia, Hyundai Steel, and Hyundai Mobis. Mobis sits in the middle of both—so even though it’s “just” the parts company, it functions like a keystone.

Governance advocates have criticized this structure for years because it can allow the Chung family to exert control far beyond their direct economic ownership. That’s the point of the web: by having companies own each other, it becomes incredibly difficult for outsiders to unwind the structure, challenge leadership, or force change.

For investors, it’s a double-edged sword. On one hand, it can create unusual stability and long-term coordination—exactly what you’d want in an industry where platforms take years to develop and supply chains can’t be flipped overnight. On the other hand, it raises permanent questions: Who really benefits from capital allocation decisions? Are minority shareholders getting fair treatment? And when the group reshuffles assets, is it optimizing value—or optimizing control?

Those tensions weren’t theoretical. In 2018 and 2019, they turned into an all-out confrontation with Elliott Management. And when Wall Street’s most aggressive activist runs into a Korean chaebol’s ownership maze, you don’t just get a proxy fight. You get a crash course in how power actually works.

III. Origins: From Shipping Containers to Precision Industry (1977–1990s)

Hyundai Mobis didn’t start with cars. It started with boxes.

On June 25, 1977, the company was founded as Korea Precision Industry, and just days later—on July 1—it was renamed Hyundai Precision Industry. It sat inside Chung Ju-yung’s Hyundai Group and, from the beginning, lived in the chaebol logic: affiliates backing affiliates, ownership and financing staying inside the family network.

That context mattered. Hyundai in this era wasn’t just a successful conglomerate; it was one of the main engines of South Korea’s industrial rise. Chung Ju-yung built a machine that could move from construction to shipbuilding to automobiles, scaling each business with the kind of coordination only a tightly controlled group could pull off. By the time he stepped back in 1991, Hyundai had become so large it represented a meaningful slice of Korea’s economy and exports.

And yet, Hyundai Precision’s first real business was shipping containers.

Production of metal shipping containers began in 1979. It was unglamorous, heavy-industry work—steel, fabrication, logistics. But the company got very, very good at it. By 1992, it had become the world’s largest producer of refrigerated shipping containers. That’s an elite position in a niche most people never think about, and it’s also the first hint of what Mobis would become: a behind-the-scenes operator that wins by mastering complex manufacturing at scale.

The automotive turn started quietly. In 1988, the company began manufacturing four-wheel-drive vehicles for its sister company, Hyundai Motor. The first was the Galloper—a rebadged Mitsubishi Pajero, reflecting the reality of Korea’s early auto era: fast learning, imported foundations, and relentless domestic iteration.

Then came the person who would bend this company toward its eventual destiny: Chung Mong-koo, the founder’s second son. He had come up through Hyundai’s ranks, and his interest in cars wasn’t theoretical. In 1991, he opened an auto plant at Hyundai Precision to produce recreational vehicles. It was a deliberate move—less about what the company was at the time, and more about what it could become inside a group that was increasingly betting its future on automobiles.

The 1990s also revealed something else: Hyundai Precision didn’t just want to fabricate. It wanted to engineer. One of the decade’s most striking side quests was the HML-03, a prototype maglev train using electromagnetic suspension. It didn’t turn into a commercial breakthrough, but it showed a pattern that would later define Mobis: a willingness to build hard, futuristic things—even before the market was ready.

And that mattered, because the reinvention was coming. When the next crisis hit Asia, Hyundai Precision would already have one foot in the auto world, and the engineering confidence to take a much bigger leap.

IV. The Great Transformation: Asian Financial Crisis & Rebirth as Mobis (1997–2002)

The Asian Financial Crisis of 1997 to 1999 didn’t just rattle South Korean industry. It snapped it in half. Conglomerates that had looked untouchable suddenly found themselves negotiating with creditors, governments, and reality. For Hyundai, the crisis became the crucible that forged the modern automotive group—and it’s the moment a company best known for containers began turning into an auto-parts empire.

In the scramble to survive, stakes moved, affiliates were reshuffled, and control tightened. The group wasn’t simply cutting costs; it was redrawing the map so the automotive businesses could stand on their own, with a parts backbone strong enough to support them.

The broader Hyundai conglomerate began spinning off and separating into focused business groups in the wake of the crisis and, later, founder Chung Ju-yung’s death. The cleanup was painful, but clarifying: the old Hyundai was too sprawling to manage in a post-crisis world.

In April 1999, Hyundai announced a sweeping restructuring—slashing business units by roughly two-thirds and laying out a plan to break the group into five independent business groups by 2003. When Chung Ju-yung died in 2001, the dismantling of the old Hyundai accelerated.

For Chung Mong-koo, this chaos was also an opening. In 1998, he led Hyundai’s acquisition of the then-bankrupt Kia Motors. By 1999, Kia was back to profitability. That turnaround didn’t just rescue a brand; it stabilized the group’s automotive ambitions at the exact moment the market was questioning whether Korea’s car industry could survive.

In 2000, Chung formalized what was already becoming true in practice: Hyundai Motor Group, built around the automotive stack—vehicle manufacturing, parts, materials, and logistics.

And right in the center of that stack sat Hyundai Precision’s reinvention.

In 1999, the company began specialized production of chassis modules. In 2000, it took on a new name: Hyundai Mobis—combining “Mobile” and “System,” a not-so-subtle signal that this wouldn’t be a simple parts shop. It was being positioned as the integrator, the company that could deliver whole sub-systems to the assembly line, not just individual components.

Then came the move that looks like mere reorganization until you realize what it created. In October 2000, Mobis took charge of the production and sales of auto parts. By the end of that year, the after-sales auto parts departments at Hyundai and Kia were transferred into Hyundai Mobis.

That was the masterstroke: the boring, dependable, extremely lucrative business of replacement parts—everything that gets sold through service centers long after a car rolls off the lot—became Mobis’s domain. A cash-generating engine that could bankroll the future while the rest of the group fought for growth.

This crisis-era split, especially in 1999 and 2000, also set the ownership and role logic that still defines Mobis: it became the parts-and-modules hub for Hyundai Motor Company and Kia.

And it revealed something fundamental about how chaebol resilience actually works. In many Western systems, creditors would have broken up a struggling conglomerate and sold the pieces to the highest bidder. In Korea, cross-shareholdings and political realities made a different outcome possible: controlled transformation. Hyundai, at points, was kept from falling into the same fate as rival Daewoo through loans from state banks—support that reflected the government’s view of autos as a strategic industry, worth saving.

Hyundai didn’t escape the crisis unchanged. It escaped redesigned. And Hyundai Mobis emerged from that redesign not as a leftover affiliate, but as the connective tissue that would let the new Hyundai Motor Group operate like a machine.

V. The Modular Revolution: Becoming Indispensable (2000s–2015)

In the 2000s, Hyundai Mobis stopped being “that former container company that also makes some auto stuff” and became something far more powerful: the industrial system that let Hyundai and Kia scale globally without falling apart.

The business settled into two big engines. One was modules and parts manufacturing—building big, high-value chunks of a vehicle like chassis, cockpit, and front-end modules, alongside key components such as electronic stability control, air suspension, lighting, and braking and steering parts. The other was after-sales parts—everything that keeps a Hyundai or Kia on the road after it’s sold, from repairs to maintenance.

Mobis was inside the Hyundai family, but it wasn’t locked into only serving the family. Roughly 80 per cent of its sales went to Hyundai and Kia, with the rest going to other automakers including General Motors and Ford.

That split became the company’s defining trade. The upside was obvious: steady volume, predictable planning, and deeply synchronized development. Mobis engineers could work alongside Hyundai designers from the earliest concept stages, then deliver the finished systems in lockstep with vehicle launches. But the downside was just as real: concentration. If Hyundai and Kia sneezed, Mobis caught a cold—and that dependence would later become an easy target for outsiders looking at the group’s governance and asking who, exactly, the structure was built to benefit.

By 2014, the results spoke for themselves. Hyundai Mobis was often described as the world’s No. 6 automotive supplier—an astonishing rise into the global top tier, shoulder-to-shoulder with companies that had been doing this for generations longer.

A big part of that leap was the modular play. Instead of shipping thousands of individual parts and leaving the automaker to do the integration, Mobis shipped complete modules—cockpits, chassis systems, front-end assemblies—ready to be dropped into the vehicle on the production line. That made assembly faster and more consistent. It also made Mobis harder to replace. Once your supplier is delivering an integrated system that’s designed into the vehicle from day one, switching isn’t a purchasing decision anymore. It’s a platform decision.

This is where Mobis’s real edge took shape: designing, engineering, manufacturing, and integrating complex modules and safety and electrification systems at scale, then delivering them in sync with automaker production schedules, while running a parts distribution machine that could serve the installed base for years.

And then there was the cash cow.

The after-sales business became Mobis’s crown jewel. In late 2024, the aftersales division posted an operating profit margin of 26%—a level of profitability that looks almost surreal next to the thin margins of auto manufacturing. It worked because the economics are different: the customer is often captive to the original parts ecosystem, repairs aren’t optional, and proprietary components limit how much true aftermarket competition can creep in.

By this point, Mobis wasn’t just a supplier. It was structurally important—so important that, sitting in the middle of multiple cross-shareholding ties, it effectively functioned like a de facto holding company inside Hyundai Motor Group. And that status would matter later, because when Elliott Management came looking for leverage, it quickly realized the pressure point wasn’t just the automaker. It was the quiet company underneath it all.

VI. The Elliott Management Showdown: David vs. Goliath (2018–2019)

In April 2018, Hyundai Motor Group learned what it felt like to have a spotlight snapped on from halfway across the world.

Elliott Management—one of Wall Street’s most feared activist investors—disclosed that it had built a stake of more than $1 billion across Hyundai Motor Group companies. And it didn’t show up quietly. Elliott called on the boards to explain, in plain terms, how they planned to improve corporate governance, strengthen their balance sheets, and deliver better shareholder returns. Then it went further, pushing its own restructuring ideas for Hyundai and related entities.

This was classic Elliott. Paul Singer’s firm had built its reputation through relentless, high-pressure campaigns at companies ranging from Cablevision to Samsung. But Hyundai was different. This wasn’t just another public-company turnaround story. It was a chaebol—Korea’s second-largest business empire—built on interlocking ownership, deep cultural expectations, and a family succession already in motion.

That timing mattered. Chung Mong-koo, the octogenarian patriarch of Hyundai’s modern auto era, was preparing to hand more control to his son, Chung Eui-sun. A governance fight during a generational transition isn’t just about financial engineering. It’s about who gets to write the next chapter.

Elliott’s opening attack focused on a restructuring Hyundai itself had been considering—one Elliott argued would enrich the controlling family at the expense of minority shareholders. Hyundai Mobis had said it would spin off its module and after-service parts businesses and merge them with affiliate Hyundai Glovis. Critics saw the logic immediately: Glovis was closely associated with Chung Eui-sun, and this plan looked like it would shift valuable pieces out of Mobis and into a different pocket of the group.

Elliott—and proxy advisors who agreed with it—argued that Mobis shareholders weren’t getting a fair deal. In their view, there was no sound business rationale for combining module manufacturing and after-sales parts with a logistics company. The strategy, they said, didn’t read like industrial common sense. It read like control consolidation.

The market reaction was swift and negative. In the two days after the plan was announced, Hyundai Motor, Mobis, and Kia shares fell sharply—enough to signal that investors were taking the criticism seriously.

Hyundai retreated. “We have realized that there was a lack of communication with our shareholders and the markets (over the plan),” Vice Chairman Chung Eui-sun said in a statement. The restructuring was pulled back—an outcome that, by itself, would have been a meaningful win for most activists.

But Elliott wasn’t done.

In November 2018, it came back, this time pushing for higher shareholder returns and the sale of noncore assets. Hyundai rejected Elliott’s renewed demands and instead offered its own shareholder-friendly response, including a plan to pay 1.1 trillion won in dividends for 2018.

Elliott wanted far more. It proposed dividends of 4.5 trillion won for Hyundai Motor and 2.5 trillion won for Hyundai Mobis—numbers that implied a fundamentally different philosophy about what the group’s cash was for. Elliott saw trapped value and under-distributed capital. Hyundai saw an industry on the edge of an electric and autonomous transition—and a need to keep investing.

Hyundai said in a regulatory filing that Elliott’s dividend proposal would cause a “massive cash outflow,” potentially weakening future investments and shareholder value. Mobis echoed the point, warning the payout would “undermine its future competitiveness,” as it expected to need more than 4 trillion won of investment over the next three years for new-vehicle development.

All of it led to a shareholder showdown in March 2019.

When the votes came in, Hyundai Motor and Hyundai Mobis shareholders backed management’s dividend plans and director candidates, and rejected Elliott’s proposals. Roughly nine out of ten Hyundai Motor shareholders supported the company’s dividend plan, and about seven out of ten Mobis shareholders supported Mobis’s dividend program. It was a clear defeat for the activist.

Even the proxy-advisor landscape split. Glass Lewis supported Hyundai’s approach, while Institutional Shareholder Services backed Elliott. In the end, the shareholder base sided with the group.

It was also the second act in a longer drama: a year earlier, Elliott had successfully blocked an $8.8 billion merger planned by Hyundai. But in this round—dividends, board reforms, and the broader question of who should dictate Hyundai’s governance future—Hyundai Motor Group prevailed.

The aftermath said just as much as the vote. By the end of December 2019, Elliott no longer appeared on shareholder lists. It reportedly exited its stakes—around 2.9% in Hyundai Motor, 2.1% in Kia Motors, and 2.6% in Hyundai Mobis. At one point, the fund was estimated to have lost about 500 billion won in valuation, roughly 30% of its investment across the three companies.

For outside investors, the Elliott episode clarified a few things. First, Korean corporate governance—especially inside a chaebol—is not easily reshaped by the standard Western activist playbook. Second, local institutions, including Korea’s National Pension Service as a major shareholder, proved more supportive of domestic management than foreign pressure. And third, even in defeat, Elliott likely moved the ball: it forced Hyundai to communicate more directly with shareholders, and it accelerated attention to returns and governance in a way the group couldn’t fully ignore.

VII. Leadership Transition: The Chung Dynasty Continues (2020–2024)

With the Elliott fight in the rearview mirror, Hyundai Motor Group moved to the next, bigger question: succession.

On October 14, 2020, the group announced that Euisun Chung—then Executive Vice Chairman—had been inaugurated as Chairman. Hyundai Motor Company, Kia Motors, and Hyundai Mobis each convened extraordinary board meetings to discuss the change, and the boards unanimously endorsed his appointment.

Chung Eui-sun, born October 18, 1970, is the only son of Hyundai Motor Group honorary chairman Chung Mong-koo—and the heir to the modern Hyundai automotive empire.

This handover wasn’t sudden. It was staged over years, and his résumé reads like a tour through the parts of the machine you’d want an eventual chairman to understand. He began his career at Hyundai Precision Industry (today’s Hyundai Mobis). After studying in the U.S., he worked at the New York office of Itochu Corporation, a Japanese trading company, then joined Hyundai Motor Company as Head of Purchasing. From there he moved through domestic sales and corporate planning roles across Hyundai and Kia. In 2005, he became President and CEO of Kia Motors. Later, as Vice Chairman at Hyundai Motor, he took on broader group leadership before becoming Chairman in 2020.

Along the way, he built credibility inside the group by leading Kia’s turnaround, guiding Hyundai through the global financial crisis, and helping launch Genesis as the group’s luxury brand.

But the bigger shift wasn’t just who was in charge. It was what the new chairman said Hyundai was going to be.

Under the banner “Together for a Better Future,” Chung framed the group’s priorities around customers, humanity, the future, and social contribution—and positioned Hyundai Motor Group not as a traditional automaker, but as a “mobility solutions enterprise.” That meant accelerating electrification, autonomous driving, and connectivity, while also pushing into urban air mobility, robotics, purpose-built vehicles, smart cities, and other bets designed for a world where “car company” is an increasingly narrow label.

For Hyundai Mobis shareholders, this transition reinforced a familiar dynamic: continuity of control paired with a new strategic agenda. Mobis shareholders supported the board’s plan to name Chung Eui-sun as a representative director. Hyundai Motor and Mobis held separate board meetings to appoint him in that role, giving him more latitude over key managerial decisions and shareholder policy.

Since taking the helm, Chung has pointed to Hyundai Motor Group’s rise into the global top tier of automakers, building on the legacy of his father and grandfather. Under his leadership, Hyundai Motor and Kia also accumulated major external validation, winning a total of 12 World Car Awards—including four consecutive World Car of the Year titles since 2022 with the Hyundai IONIQ 5, Hyundai IONIQ 6, Kia EV9, and, in 2025, the Kia EV3.

For Mobis, the implication was straightforward and huge. If Hyundai’s future was electrified, autonomous, and software-driven, then the “parts company” could no longer just be a manufacturing arm. It had to become a technology platform—one that could translate the chairman’s mobility ambitions into hardware, software, and systems that actually ship.

VIII. The EV & Autonomous Driving Pivot (2020–Present)

The auto industry didn’t just start changing in the 2020s. It started re-platforming. The center of gravity moved away from horsepower and sheet metal and toward software, sensors, batteries, connectivity, and autonomy. For Hyundai Mobis, that shift was both an existential threat and a once-in-a-generation opening: the “parts company” could either get trapped making legacy hardware—or become the systems integrator for the next era of vehicles.

One of the clearest signals of that ambition showed up in the United States. Hyundai Mobis laid plans to build an EV Power Electric system plant in Bryan County, Georgia, designed to support Hyundai Motor Group’s electrification push. The company aimed to begin construction on a massive facility as early as January 2023 so production could start in 2024.

This Georgia plant was built around the unglamorous but essential guts of the EV: EV Power Electric systems and integrated charging control units. These would feed Hyundai Motor Group’s U.S. EV manufacturing footprint, tying Mobis even more tightly into the group’s North American buildout—and bringing a nearly billion-dollar investment and thousands of jobs along with it.

That supply chain sits alongside Hyundai’s own huge U.S. manufacturing bet: a multi-billion-dollar investment in its American EV assembly operation. Full production at Hyundai Motor Group Metaplant America began in October 2024, and the first vehicle off the line was the 2025 Ioniq 5.

But Mobis also had a strategic problem to solve: concentration. For years, the bulk of its business came from inside the family. If it wanted to be seen as a true global technology supplier—and valued like one—it needed major customers outside Hyundai and Kia.

That’s why the breakthrough with Volkswagen mattered.

Hyundai Mobis said it broke ground on an electric-vehicle battery pack plant in Spain to supply Volkswagen, after winning a battery system assembly order from the German automaker the year prior—an order that was reported to be worth billions of dollars. The facility would be Mobis’s first EV battery system-dedicated plant in Western Europe, with mass production scheduled to begin in 2026.

“The new plant in Spain means our entrance into the Western European market and will serve as a dedicated facility for Volkswagen,” Hyundai Mobis said in a statement.

The message was hard to miss: Mobis wanted to reduce its dependence on Hyundai Motor Group, and it described Volkswagen as a key global customer.

On the autonomy and ADAS front, Mobis leaned into partnerships with major technology players. It collaborated with Qualcomm Technologies on an end-to-end system combining Qualcomm’s Snapdragon Ride Flex System-on-Chip and Snapdragon Ride Automated Driving Stack with Hyundai Mobis’s software platform, sensors, and integration know-how. The pitch was straightforward: modern cars need serious compute and high-end graphics, and the Flex SoC approach supported cockpit, ADAS, and automated-driving functions on a single chipset.

Then, at CES 2025, Mobis showed the industry what it wanted to be associated with: not commodity parts, but sci-fi-level interface tech.

Hyundai Mobis introduced what it described as the world’s first full-windshield holographic display—an in-vehicle display concept that doesn’t rely on a conventional physical screen. Instead, it uses a specialized film embedded with a Holographic Optical Element, projecting images and video through light diffraction so the information reaches the viewer’s eyes. Mobis developed the technology in collaboration with ZEISS, the German optical company.

It wasn’t mass-produced yet. Mobis and ZEISS planned to complete pre-development by mid-2026, with the goal of bringing the product to market by 2027.

If it works as intended, it changes the driver’s experience in a simple, profound way: the windshield becomes an ultra-large display surface, and drivers no longer need to glance down at an instrument cluster or other controls.

IX. The Hydrogen Bet & Strategic Refocus (2021–2024)

Hyundai Motor Group’s commitment to hydrogen was one of the boldest wagers in an industry scrambling for a post-gasoline future. For Hyundai Mobis, that wager translated into something very tangible: build the fuel-cell factory capability, prove it could run at scale, and help turn hydrogen from a concept into a supply chain.

In October 2021, Mobis held a groundbreaking ceremony in Korea for two new fuel cell plants, announcing about $1.1 billion of investment. This wasn’t a standing start. Back in 2018, Mobis had already become the world’s first to set up a complete production system in Chungju, spanning the fuel cell stack through the supporting electronic components.

Then came the twist.

Hyundai Motor Company agreed to acquire Mobis’s domestic hydrogen fuel cell business for 217 billion won (about $163 million), in a deal that transferred the assets, personnel, and operations to Hyundai Motor. The strategic intent was clear: consolidate the group’s hydrogen energy efforts under the automaker, putting the full hydrogen R&D-and-production stack “under one roof.”

The rationale was just as blunt. Despite heavy investment, Mobis’s hydrogen push hadn’t produced clear results because the hydrogen vehicle market grew more slowly than hoped. And hydrogen isn’t just “another powertrain” you swap in. Fuel cell vehicles involve more complex technology than battery EVs, which makes components more expensive. On top of that, the refueling ecosystem lagged badly—far fewer hydrogen stations than EV chargers—making adoption harder, which in turn makes scale harder, which in turn keeps costs high.

So Mobis stepped back.

By transferring its hydrogen operations and pivoting toward electrification components, Mobis could concentrate on the part of the transition where volumes were arriving faster and the path to profitability looked more straightforward. Hyundai Motor, meanwhile, positioned itself to push fuel cells beyond hydrogen passenger cars into a broader set of applications—power generation, trams, ports, ships, and even advanced air mobility—in hopes that diversification and unified management would bring infrastructure and operating costs down over time.

Zoom out, and this move is also a clean example of how chaebol mechanics work in practice. Affiliates can reallocate businesses to match the group’s shifting priorities, quickly and decisively. That flexibility can be strategically powerful. It can also raise the perennial minority-shareholder question: when assets move around inside the family, is each public company getting a fair deal?

For Hyundai Mobis, the bet on hydrogen became something else: a lesson, and a refocus—away from the hardest-to-scale path, and toward the electrification systems that were already becoming the industry’s center of gravity.

X. Playbook: Business & Strategic Lessons

Step back from the corporate history and the governance drama, and Hyundai Mobis starts to look like a playbook—a set of repeatable strategic moves that explain how a company can become enormous, essential, and still mostly unknown outside the industry.

The Hyundai Mobis story offers several strategic lessons for students of business and long-term investors.

The "Invisible Champion" Model. Mobis built a forty-billion-plus revenue business that most consumers have never heard of, by becoming the infrastructure behind the brands people do recognize. That position comes with real advantages: you don’t need to spend like a consumer brand, you’re less exposed to reputational whiplash, and demand can be steadier when you’re deeply embedded in vehicle programs. The trade-off is that you’re rarely the one setting the narrative—or the pricing—and your results depend heavily on a small set of customer relationships staying healthy.

Captive Customer Advantage. Around 80 per cent of Mobis’s business came from Hyundai and Kia. That concentration is a feature, not a bug: it enables synchronized development, predictable volume planning, and deep integration from the earliest stages of a platform. But it also creates strategic vulnerability. When your largest customers share your last name, your fortunes rise and fall with the group’s competitiveness, product cadence, and execution.

After-Sales as Cash Cow. The aftersales division stayed highly profitable in late 2024, posting an operating profit margin of 26%. In a world where manufacturing margins are often thin, that kind of profitability is the stabilizer. It’s also why the group structure matters: the surviving company retained the after-sales service division, along with the research and development unit and the automotive chipmaking business. In practice, that high-margin stream helps bankroll the expensive, long-horizon bets—electrification, ADAS, and the software-heavy systems that define modern vehicles.

Technology Transformation. Mobis’s long arc is constant reinvention: from modules to the building blocks of software-defined vehicles. In its own framing, the company has been reshaping its business structure around profitability while leaning on what it calls its global technological competitiveness. It laid out mid-to-long-term targets that included average annual revenue growth of 8% and an operating margin of 5–6% by 2027.

The bigger ambition is about customer mix. By 2033, Hyundai Mobis aimed to raise the share of global automakers in its auto component manufacturing business from about 10% to 40%—a direct attempt to reduce dependence on Hyundai Motor Group and earn a valuation more like a true global supplier.

Surviving Activist Pressure. The Elliott episode made one thing clear: Western activist playbooks don’t automatically work inside Korean chaebol governance. But it also proved that pressure leaves a mark. Even without winning the votes, Elliott helped force more direct communication with shareholders, and Hyundai modestly improved shareholder returns and governance transparency in the years that followed.

XI. Porter's 5 Forces & Hamilton's 7 Powers Analysis

Porter's Five Forces

Threat of New Entrants: LOW. Auto supply is a brutal club to break into. The barriers aren’t just money—though the capital requirements are massive. It’s the years of qualification cycles, safety and regulatory certifications, and the deeply embedded relationships with OEM engineering teams. A new entrant would need billions of dollars and a long runway before it could be trusted with safety-critical systems.

Supplier Power: MODERATE. Mobis lives downstream of some of the most constrained inputs in modern manufacturing: semiconductors and specialized raw materials. It can’t simply will supply into existence, and the 2021–2022 chip shortage made that painfully obvious across the industry. Mobis has worked to reduce the risk through vertical integration and alternative sourcing, but supplier leverage remains a real factor when the world runs short on the things your products can’t ship without.

Buyer Power: MODERATE-HIGH. This is the trade at the heart of Mobis. Roughly 80 per cent of its sales come from Hyundai and Kia. That concentration provides stability, planning visibility, and deep platform integration—but it also gives the buyers meaningful influence. Mobis is trying to rebalance that equation by winning business outside the group. The Spain battery pack plant for Volkswagen is the clearest signal of intent: “The new plant in Spain means our entrance into the Western European market and will serve as a dedicated facility for Volkswagen.” The direction is clear; the mix shift is still in progress.

Threat of Substitutes: MODERATE-HIGH. Mobis competes in a world packed with capable alternatives—Bosch, Continental, ZF, Denso, Magna, Valeo, and more. And the definition of “substitute” is evolving. As vehicles shift toward software-defined architectures, value can move away from traditional components and toward compute platforms, operating systems, and integrated stacks. That creates new ways to compete—and new ways to get displaced.

Competitive Rivalry: HIGH. This is one of the most competitive supplier industries on earth, and Mobis is in the top tier—often cited around sixth globally. Whether it’s ADAS sensors, electrification components, or classic modules, it’s fighting world-class rivals for design wins that can last an entire vehicle generation. The competition is constant, global, and unforgiving.

Hamilton's 7 Powers

Counter-Positioning. Mobis is pushing to be a hardware-and-software integrator, not just a parts maker—positioning itself for the software-defined era while some incumbents remain more mechanically oriented. The Qualcomm collaboration is a good example: Mobis is aligning with advanced compute and a full-stack approach rather than treating electronics as bolt-on features.

Scale Economies. Mobis operates at enormous scale, with 2024 consolidated revenue in the mid-to-high tens of trillions of won and operating profit above 3 trillion won. That scale matters because it funds R&D, drives purchasing leverage, and enables cost-down learning curves. The prize is margin improvement in electrification as volumes ramp and manufacturing gets optimized.

Switching Costs. For Hyundai and Kia, Mobis isn’t a vendor you swap out at the next bidding cycle. Its systems are engineered into platforms, and its production timing is synchronized to vehicle launch schedules. Once those timelines and interfaces are locked, switching becomes a redesign—slow, risky, and expensive.

Network Effects. There aren’t strong classic network effects here, but there is an ecosystem effect inside Hyundai Motor Group. Investments, shared roadmaps, and coordinated platform decisions can compound across affiliates, creating an internal flywheel that’s hard for outsiders to replicate.

Cornered Resource. Mobis has a privileged seat inside Hyundai Motor Group: early access to product plans, direct alignment to platform roadmaps, and a large captive demand base. That relationship is a strategic resource in itself, and Mobis’s work on eco-friendly technologies directly supports the group’s broader ambition to lead in sustainable mobility.

Process Power. Mobis’s advantage is operational as much as technological: systems integration, module delivery synchronized to automaker production, and a scalable global aftersales parts distribution machine. Those capabilities are built over decades, and they’re difficult to copy quickly—even with money.

Brand. Mobis doesn’t have much consumer brand power because it’s largely B2B. But within OEM procurement and engineering circles, brand shows up differently: a reputation for reliability, integration competence, and on-time delivery. In automotive, that kind of trust is a currency.

XII. Key Performance Indicators for Investors

If you’re looking at Hyundai Mobis as a long-term holding, the story on the surface is straightforward: a giant supplier with a built-in customer base. The real question is whether it can turn that home-field advantage into a more diversified, higher-quality earnings profile as the industry shifts to EVs and software-defined vehicles. Three KPIs tell you most of what you need to know.

1. Non-Captive Revenue Share. Today, only about 10% of Mobis’s automotive component sales come from customers outside Hyundai Motor Group. Management has been explicit about wanting to change that. By 2033, Hyundai Mobis aims to raise the share of global automakers in its auto component manufacturing business from roughly 10% to 40%. Each step toward that goal matters because it signals two things at once: lower concentration risk, and proof that Mobis can win on merit in the open market—not just inside the family.

2. Operating Margin Trajectory. Mobis has laid out mid-to-long-term targets of about 8% average annual revenue growth and an operating margin of 5–6% by 2027. That margin line is the tell. The company has the cushion of a high-margin aftersales business, but it’s also pouring money into electrification and advanced electronics. Watching margins over time shows whether those investments are compounding into a stronger business—or simply raising the cost base.

3. R&D Spending Intensity. Mobis has said it plans to invest more than 2 trillion won in research and development this year. In this era, R&D isn’t optional—it’s the entry fee for EV platforms, ADAS, and next-generation cockpits. But for investors, the key is translation: sustained spending has to show up later as design wins, higher-value content per vehicle, and, ultimately, better margins.

XIII. Bull and Bear Cases

The Bull Case

Start with the market’s basic premise: Hyundai Mobis has often traded at a noticeable discount to global auto-supplier peers. The optimistic view is that the gap is out of sync with what the company actually is today—a scaled, increasingly tech-heavy supplier with a built-in customer base and real momentum in electrification and advanced electronics.

The financial performance gives that argument some weight. For the year ended Dec. 31, 2024, Hyundai Mobis reported net profit of 4 trillion won, up 46.5% year over year.

That improvement didn’t come out of nowhere. In one recent quarter, the company posted a 36.8% year-on-year rise in operating profit, helped by a deliberate shift toward higher-margin components and a ramp in electrification. Operating profit came in at 870 billion won for the three months ended June, while sales rose 8.7%.

Another quarter told a similar story. Hyundai Mobis said its first-quarter operating profit jumped 43.1% year on year to 776.7 billion won—its highest-ever first-quarter result—while sales rose 6.4% to a new first-quarter high as well.

Then there’s the strategic proof point investors have been waiting for: winning outside the family. The Volkswagen battery-system deal and the Spain plant are more than a single contract—they’re a signal that Mobis can compete for major non-captive business in Western Europe. Excluding Hyundai Motor and Kia, Hyundai Mobis secured $2.12 billion in orders from global automakers in the first half of the year, which it described as about 30% of its full-year target of $7.45 billion.

Layer on the technology narrative—partnerships like Qualcomm, plus showpiece concepts like the holographic windshield display—and the bull case becomes straightforward: Mobis isn’t just riding Hyundai Motor Group’s EV success; it’s building the kinds of electronics, compute, and integrated systems that will define how value is distributed in the next generation of vehicles. If Hyundai and Kia keep winning with models like the IONIQ 5 and EV6, Mobis is structurally positioned to capture more content per vehicle, not less.

The Bear Case

The bear case starts with the same fact the bull case celebrates: Mobis is deeply tied to Hyundai Motor Group. Customer concentration remains high, which means any stumble at Hyundai or Kia shows up quickly in Mobis’s results. And the chaebol structure that provides coordination and stability also creates permanent governance questions—questions that, for some investors, justify a persistent valuation discount.

There’s also reputational and regulatory sensitivity around how that ecosystem operates. Hyundai Motor has been criticized for using cross-shareholding ties with affiliates—such as Hyundai Mobis and Hyundai Glovis—to restrict the supply and distribution of spare parts and after-sales services, harming the interests of independent dealers and consumers.

Then there’s the long-term threat to Mobis’s highest-quality profit stream: aftersales. EVs generally require less routine maintenance than internal-combustion vehicles, and over time that could reduce demand for certain replacement parts. If the installed base shifts decisively toward EVs, the fear is that the dependable aftermarket engine starts to sputter.

Finally, the competitive terrain is shifting under every supplier’s feet. Software-led disruption could commoditize what used to be defensible hardware advantages, and global market dynamics can quickly compress margins—especially in an environment shaped by China’s price wars and potential export-control risks. If Mobis can’t secure design wins early, scale them efficiently, and defend its position in the stack, the story could become one of heavy investment without commensurate returns.

XIV. Conclusion: The Hidden Engine Revealed

Hyundai Mobis is a case study in the forces that shape modern industrial giants: the advantages of vertical integration, the unique power dynamics of family-controlled conglomerates, and the difficulty of reinventing yourself fast enough when technology shifts under your feet.

Management has been explicit about where it wants the company to go next. President Lee Gyusuk put it this way: “With revenue growth becoming substantial around high-value core components, we anticipate qualitative growth based on profitability, leveraging our leading technological competitiveness, we will expand the global automaker sales share in the auto component manufacturing sector to 40% by 2033, propelling us to become a top three automotive supplier.”

Mobis has also leaned harder into shareholder returns. This year, it repurchased and canceled treasury shares worth 620 billion won—nearly four times last year’s amount—alongside its stated commitment to a more transparent and predictable policy across dividends and buybacks. The message is that the company wants trust with shareholders to be a strategy, not a slogan.

And when you zoom out, the arc is still kind of unbelievable. A company that began with shipping containers now talks about software platforms, ADAS stacks, battery systems, and holographic displays that turn the windshield into an interface. It has survived a financial crisis that remade Korea’s corporate landscape, an activist assault that tried to unwind the group’s logic, and an industry transition that’s redefining what “auto supplier” even means.

The next chapter comes down to execution: can Mobis keep widening its customer base beyond Hyundai and Kia, protect its profitability as EVs reshape the economics of parts and service, and win on merit against global suppliers and technology players who are all racing toward the same future?

For investors, that’s the bet. Hyundai Mobis offers exposure to one of the world’s most successful automotive groups, but at a valuation that reflects real concerns—governance, concentration risk, and the uncertainty of the transition ahead. Whether that discount is an opportunity or a warning depends on how you think Korean corporate governance evolves, and how the spoils of the automotive technology shift ultimately get divided.

Either way, the hidden engine of Korea’s automotive empire is no longer invisible. The only question is whether the rest of the market will start treating it like the strategic asset it has become.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music