Samsung Heavy Industries: Korea's Ship of State

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

Picture a floating factory so big it barely feels like a ship at all. Nearly 500 meters long—longer than four soccer fields end to end—it gets towed thousands of kilometers across the Pacific, inching away from the shipyard like a moving city block. In July 2017, Shell’s Prelude FLNG departed Samsung Heavy Industries’ Geoje yard for its new home off the coast of Western Australia, a moment that still reads like science fiction made real. Prelude measures 488 meters long, 74 meters wide, and about 105 meters tall, built from more than 260,000 tonnes of steel. When it’s fully loaded, it tips the scales at more than five Nimitz-class aircraft carriers combined.

Now the twist: the same company that pulled off that feat almost sank itself trying to chase the offshore oil boom.

When oil prices collapsed and offshore projects imploded, South Korea’s “Big Three” shipbuilders bled. By 2016, they were reporting massive losses tied to the prior year—8.5 trillion won combined for 2015—with Daewoo Shipbuilding alone losing 5.5 trillion won. Samsung Heavy Industries wasn’t spared. It took severe hits, posting huge losses for three straight years from 2015 through 2017.

So how does a company eat billions in losses, survive, and then come back to become the world’s last, best option for building some of the most complex energy infrastructure on Earth?

That question got even more interesting in January 2025, when the Trump administration sanctioned China’s Zhoushan Wison shipyard—Samsung Heavy’s only serious rival in FLNG construction. And unlike most commercial ship types, where shipbuilders fight for single-digit margins, FLNG units can earn double-digit margins precisely because they’re so hard to build. Samsung Heavy, which holds roughly 55% of the FLNG construction market, sits right at the center of that reality.

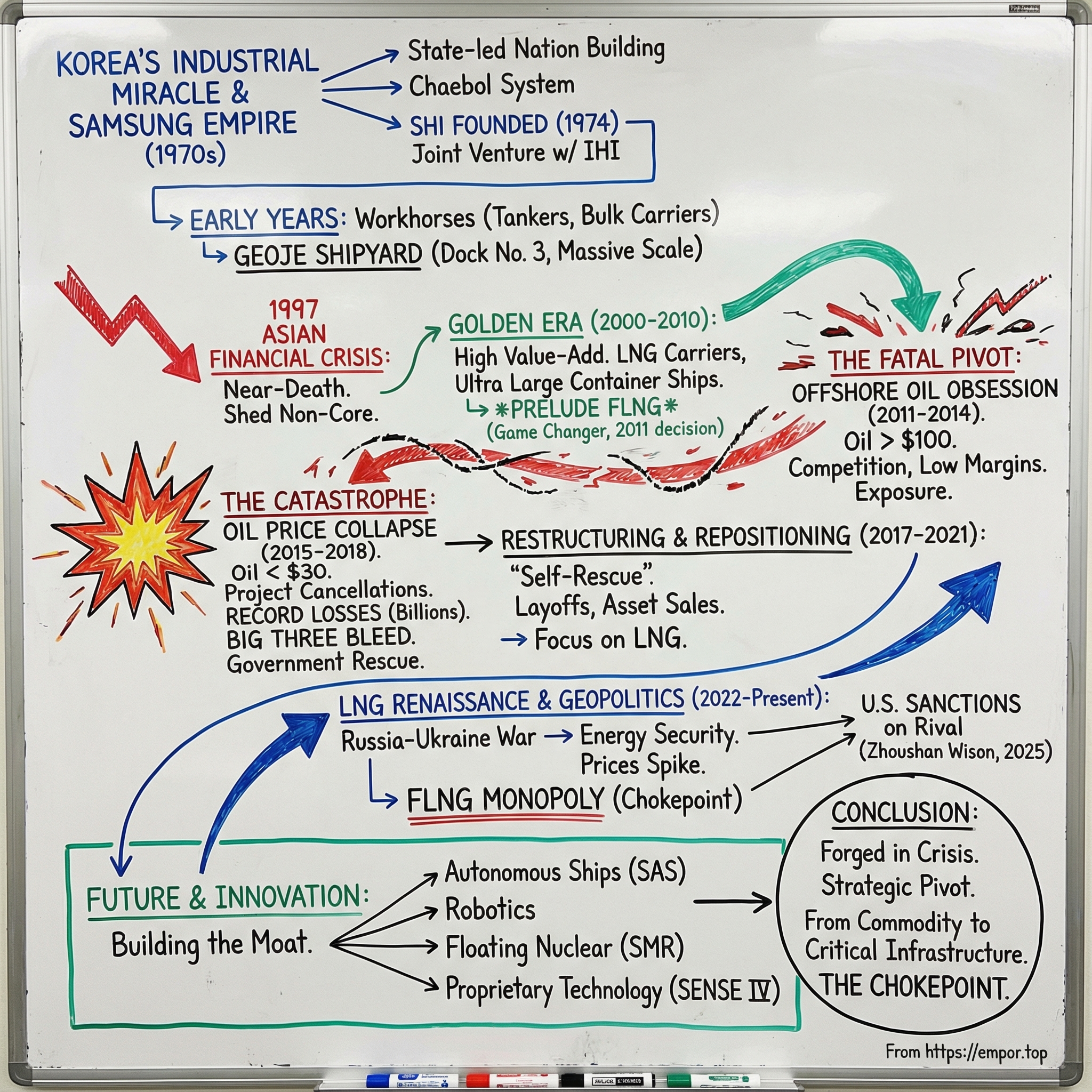

This is the story of a company forged in Korea’s nation-building era, nearly broken by an offshore oil obsession, and reborn as a critical supplier for the world’s LNG future. It’s a story of brutal cycles, strategic pivots, and how technology and geopolitics can turn yesterday’s near-disaster into tomorrow’s advantage.

II. Korea's Industrial Miracle & The Samsung Empire

To understand Samsung Heavy Industries, you first have to understand the speed and scale of South Korea’s transformation in the twentieth century. In 1960, South Korea’s per capita income was roughly on par with Ghana’s. The country had been flattened by war, split by ideology, and left with little industrial base to speak of. And then, in the span of a generation, it pulled off one of the most dramatic economic turnarounds in modern history.

Shipbuilding was a centerpiece of that plan. Beginning in the early 1970s, South Korea didn’t so much “enter” the global shipbuilding market as engineer its way in. The government treated shipbuilding like strategic infrastructure: it directed capital, organized industrial capacity, and pushed exports—while keeping labor costs internationally competitive. This wasn’t a gentle, organic rise. It was industrial policy with the volume turned all the way up.

That machinery ran through the chaebol system: giant, family-controlled conglomerates that blurred the line between private enterprise and national development. Samsung was the archetype. Founded in 1938 by Lee Byung-chul as a trading company, it steadily expanded into food processing, textiles, insurance, securities, and retail. Then came the moves that would define the modern Samsung: electronics in the late 1960s, and in the mid-1970s, construction and shipbuilding—the heavy-industry bets that could scale with the country’s ambition.

The timing wasn’t an accident. In the 1970s, sea-based North Korean provocations pushed South Korea to build maritime strength, including the Patrol Boat Acquisition and Domestic Building Policy. At the same time, the government’s Third Five-Year Economic Development Plan (1972–1977) put heavy and chemical industries at the top of the national priority list—explicitly aimed at self-sufficiency and export power. Samsung Heavy Industries would be born right in the middle of that national push.

The chaebol model also shaped how these companies behaved. Cross-shareholdings helped them survive shocks. Family control encouraged long-term commitments. And government backing didn’t just provide capital—it signaled that certain industries mattered enough that the country would not easily let them fail. Meanwhile, traditional shipbuilding powerhouses in Europe and the United States looked tired, expensive, and politically constrained. Korea saw a gap—and moved fast to fill it.

So Samsung Heavy didn’t start life as just another manufacturer hunting for margins. It emerged as a tool of nation-building. And that origin story matters, because it set the company’s default settings: a higher tolerance for risk, a closer relationship with the state, and—when things went wrong—the institutional gravity to survive crises that would have wiped out a more purely market-driven rival.

III. Birth of a Shipbuilder: The Founding Years (1974–1990)

In 1974, Samsung’s founder Lee Byung-chul made the move that would turn Samsung into a player on the world’s oceans. He signed a joint venture with Japan’s IHI and formally launched Samsung Heavy Industries. The partner choice wasn’t symbolic. IHI was one of Japan’s top shipbuilders, and the deal gave Samsung what it needed most at the starting line: proven shipbuilding know-how, training, and instant credibility with global buyers.

The physical footprint followed quickly. The Changwon plant was completed in 1978, and the first dock came online in 1979. Orders for crude oil carriers arrived that same year. These weren’t exotic ships. They were the workhorses of global trade—bulk carriers and tankers—exactly the kind of “build it, learn it, build it better” product that lets a new yard climb the curve fast. The point wasn’t sophistication. It was repetition, execution, and the accumulation of hard-won experience.

Then came a defining consolidation. In 1983, Samsung Shipbuilding and Daesung Heavy Industries were merged into Samsung Heavy Industries. The merger streamlined operations and expanded the company’s capacity to build larger vessels. That same year, SHI delivered its first 100,000 DWT tanker—a milestone that signaled it was moving beyond starter projects and into the realm of serious commercial shipbuilding.

Samsung Heavy also didn’t stay in a single lane. In the late 1980s, it began producing forklifts and heavy equipment, mainly excavators, at Changwon. Forklift production was set up through agreements with Clark Material Handling Company. Heavy equipment manufacturing came from the construction equipment division of Korea Heavy Industries and Construction, which Samsung had acquired in 1983. Like much of Korea’s industrial playbook at the time, this was about building a broader base of manufacturing capability, not just a single product line.

All of this was building toward the company’s real centerpiece: Geoje. In South Gyeongsang Province, Samsung Heavy was assembling one of the largest shipyards on Earth, with three dry docks and five floating docks. The scale is hard to visualize until you look at Dock No. 3—640 meters long and nearly 100 meters wide. This is where the yard would eventually specialize in the ships that define modern high-end shipbuilding: ultra-large container ships, LNG carriers, and LNG-FPSOs. The yard runs at an unusually high tempo, turning docks over repeatedly and launching dozens of ships a year.

By the end of the 1980s, SHI was no longer just a domestic industrial project. It had begun winning orders from Japanese and European clients and was evolving from a technology recipient into a credible competitor—still chasing Japan at the top end of the market, but no longer a newcomer trying to prove it belonged.

IV. The 1997 Asian Financial Crisis: Samsung's First Near-Death Experience

The Asian financial crisis of 1997 and 1998 was a full-system stress test for South Korea’s economic model. Conglomerates had piled up leverage, much of it short-term and denominated in foreign currency. When the won collapsed, the math stopped working almost overnight. The fallout was brutal enough that Korea needed an IMF rescue, and even household-name chaebol didn’t make it. Daewoo, once the country’s second-largest conglomerate, would ultimately be broken apart.

For shipbuilders, though, the wreckage came with an unexpected tailwind. A weaker won made Korean yards dramatically cheaper in global terms. In the same moment that credit tightened at home, Korea’s shipbuilders became more attractive abroad—able to quote prices that Japanese and European competitors struggled to match.

Samsung, compared to many peers, came through relatively intact. That doesn’t mean it escaped unscathed. Samsung Motor was sold to Renault at a significant loss—an unmistakable sign that even Samsung had to pay the price of the IMF-era cleanup.

At Samsung Heavy Industries, the crisis did what crises often do: it forced clarity. The company shed businesses that weren’t central to building ships. After the foreign exchange crisis, Volvo Trucks of Sweden took over SHI’s heavy equipment production division in Changwon. The forklift division was then merged with Clark USA, and the business was renamed Clark Material Handling Asia.

In practical terms, the core move was simple: sell the construction equipment division to Volvo in 1998—an asset that would become part of today’s Volvo Construction Equipment—and keep the shipbuilding and offshore operations under Samsung Group control. The result was a leaner Samsung Heavy, more tightly aligned to what it could plausibly be world-class at.

The takeaway seemed obvious. Stick to the core. Keep the balance sheet survivable. Use downturns to cut distractions before they cut you. It was a lesson Samsung Heavy learned early—then, in the euphoria of the offshore oil boom years later, would drift away from, and have to relearn the hard way.

V. The Golden Era: Rise to Global Leadership (2000–2010)

The 2000s opened with a quiet changing of the guard. Japan—once the unquestioned heavyweight of global shipbuilding—was getting squeezed on cost. By the mid-1990s, building a ship in Japan cost roughly a quarter more than in South Korea. In 2000, the inevitable happened: Japan lost the number one global ranking position to South Korea.

Samsung Heavy Industries rode that wave, but it didn’t try to win by simply building more hulls. Its strategy was sharper: move up the value chain. Instead of chasing commodity vessels where price is everything, SHI increasingly aimed for the ships that were harder to design, harder to build, and harder to replace. It leaned into high added-value and special purpose vessels—LNG carriers, offshore-related vessels, oil drilling ships, FPSO/FSO’s, ultra large container ships, and Arctic shuttle tankers.

In other words: if it was complex and high-stakes, Samsung wanted to be in the room.

And you can see that ambition in the milestones that followed. In 2008, SHI built 266,000-cbm LNG carriers—enormous, technically demanding ships at the very top end of commercial shipbuilding. In later years it would notch other “firsts” and “biggests,” including the world’s first very large ethane carriers (VLECs) in 2014 and 23,000-teu container ships in 2017—each one a reminder of where the company believed the real defensibility lay: at the frontier.

Geoje became the engine of that positioning. From this island yard, Samsung Heavy built a formidable presence in the premium categories, including drillships and LNG carriers—segments where capability, not just price, decides who wins and who gets shut out.

But a decade like this doesn’t come without scars. On December 7, 2007, the offshore crane Samsung No. 1, owned by Samsung Heavy Industries, collided with the Hong Kong oil tanker Hebei Spirit. The result was the worst oil spill in Korean history. It was a harsh reminder that in heavy industry, operational failure isn’t just expensive—it’s public, permanent, and tied to your name.

Still, the defining achievement of this era wasn’t a conventional ship at all. It was floating LNG.

In July 2009, Shell awarded a contract for the design, construction, and installation of multiple FLNG facilities over as long as 15 years to a consortium of Technip and Samsung Heavy Industries, based on Shell’s proprietary design. Shell then approved Prelude FLNG for funding in 2011.

This was Samsung Heavy taking the lead in a new category—developing new ship concepts like FLNG, where “shipyard” starts to look more like “megaproject factory.” Prelude, the world’s first LNG-FPSO commissioned by Royal Dutch Shell in 2011 and capable of producing 3.6 million tons per annum of LNG, was delivered in 2017.

It wasn’t just a marquee order. It was Samsung making a statement: we’re not here to build what everyone else can build. We’re here to build what almost nobody can.

VI. The Fatal Pivot: Offshore Oil & The Seeds of Destruction (2011–2014)

Then the floor dropped out.

The 2008 global financial crisis didn’t just slow commercial shipping; it froze it. In 2007, more than 5,000 ships were ordered worldwide. A year later that fell to roughly 3,400, and by 2009 it was down around 1,200. For shipbuilders, that kind of collapse isn’t abstract. These are businesses built on massive fixed costs—yards, cranes, dry docks, specialized labor—that don’t shrink just because the orderbook does. When the pipeline dries up, you either find work or you start dismantling your company.

So the industry did what it thought it had to do: it went looking for a new ocean to sail on, and offshore oil looked like the answer.

At the time, the logic felt bulletproof. Oil was trading above $100 a barrel. Energy companies were spending aggressively on offshore exploration and production. Offshore platforms, drillships, and related facilities carried premium price tags. If container ships and bulk carriers were suddenly a dead end, why not pivot from building vessels that move commodities to building floating infrastructure that produces them?

In 2011, South Korea’s Big Three—Samsung Heavy Industries, Hyundai Heavy Industries, and Daewoo Shipbuilding & Marine Engineering—pushed hard into offshore. But the move came with a poison pill: competition was fierce, and everyone was trying to replace lost ship orders at the same time. That turned into a race to the bottom. Korean yards slashed prices on offshore plant projects to win deals and keep their docks occupied, even if the profitability wasn’t there.

Samsung Heavy, in particular, became heavily exposed. For a stretch, offshore plants and related facilities made up about two-thirds of its revenue, with the remaining third coming largely from sophisticated ships like LNG carriers. It looked like diversification. In reality, it was concentration—just in a business that would punish mistakes far more brutally.

Because offshore construction isn’t shipbuilding with extra pipes bolted on. The risk profile is fundamentally different. Korean shipbuilders largely had the capacity to assemble marine engineering equipment, but many critical components had to be purchased from foreign suppliers. And in offshore, “components” can mean single pieces of equipment that cost hundreds of millions of dollars. If one of those items shows up late—or doesn’t work as promised—the entire project schedule slips. Then labor costs keep running, financing costs keep compounding, and the losses don’t arrive gradually. They snowball.

On top of that, the yards didn’t have deep experience in offshore plant design. This wasn’t building a bigger version of something they’d built a hundred times before. It was stepping into a new category with different engineering demands, a different supplier ecosystem, and contract structures that could turn small delays into enormous liabilities.

And already, you can see how precarious it was becoming inside Samsung Group. In 2014, Samsung Heavy Industries was reportedly on the list of assets the group considered selling to Hanwha Group as part of a package deal. But the shipbuilder was ultimately excluded from the so-called “big deal” worth 2 trillion won between Samsung and Hanwha in 2015, for reasons that were never publicly explained. Later, market talk spread that Samsung executives regretted not selling Samsung Heavy when they had the chance.

At the time, that sounded like gossip. Soon, it would read like prophecy.

VII. The Catastrophe: Oil Price Collapse & Industry Meltdown (2015–2018)

In mid-2014, oil prices started sliding from over $100 a barrel. By early 2016, they had crashed below $30. And that single chart drove a wrecking ball through offshore shipbuilding.

At $100 oil, deepwater projects penciled out. At $50, they didn’t. Energy companies froze spending, then began cancelling projects outright or pushing deliveries into an indefinite “later.” For yards that had stuffed their orderbooks with offshore work—often on aggressive pricing—those delays weren’t just inconvenient. They were lethal. Costs kept accruing while revenue slipped, and the losses that had been hiding inside optimistic project schedules suddenly surfaced all at once.

By the first half of 2015, the scale of the damage was already showing. Hyundai Heavy Industries, Samsung Heavy Industries, and Daewoo Shipbuilding & Marine Engineering—Korea’s Big Three and, at the time, the world’s three biggest shipbuilders—posted a record combined loss of $4.4 billion.

And it didn’t stop. South Korea’s Big Three were set to rack up more than 8 trillion won in operating losses for 2015, with the same offshore pain continuing to hit earnings through 2016. The industry was trying to stabilize, but the math wasn’t improving fast enough.

Samsung Heavy’s response was survival mode. It raised cash through equity: a $1 billion new share issue in 2016, followed by another $1.4 billion issue later. The stated goal was straightforward—pay down debt and avoid a scenario where banks tightened lending just as losses widened. Investors didn’t exactly applaud. Samsung Heavy’s stock plunged after it forecast surprise losses and announced the share sale plan. At the time, it was also carrying roughly 3.3 trillion won in short-term debt, and management expected demand for new vessels and offshore projects to keep shrinking.

Out in the real economy, the damage was even harder to ignore. The shipbuilding hubs—Geoje and Ulsan most of all—felt like company towns in a downturn. In Ulsan, unemployment benefit claims jumped 18%. For a country that had treated shipbuilding as strategic infrastructure, watching those communities hollow out was a political problem as much as an economic one.

The low point came in April 2016. With crude oil still depressed and global trade weak, the Korean shipbuilding industry hit an unimaginable milestone: for the first time in history, none of the Korean shipbuilders won a single order that month.

Meanwhile, the balance-sheet pressure kept building. The Big Three collectively carried $42.1 billion in loans, and they closed out 2015 with combined losses of more than $6 billion.

At that point, a government response wasn’t a question of if, but how. South Korea announced plans to spend about 11 trillion won by 2020 to support the industry—ordering more than 250 vessels and providing roughly 6.5 trillion won in financing support. The logic was as cold as it was compelling: shipbuilding has massive barriers to entry. You can’t replace it quickly, and you can’t rebuild it easily once it’s gone. So the state stepped in to keep the ship of state afloat.

VIII. The Long Road to Recovery: Restructuring & Repositioning (2017–2021)

After the government lifeline came the hard part: proving the yards could survive without it.

Creditors pushed Korea’s Big Three—Hyundai Heavy Industries, Samsung Heavy Industries, and Daewoo Shipbuilding & Marine Engineering—into “self-rescue” mode. That meant austerity with real consequences: large-scale layoffs, executive pay cuts, and the sale of non-core assets and subsidiaries. In 2016, all three submitted turnaround plans to their lenders and the government. The message was clear: shrink to something that can actually make money again.

For Samsung Heavy, the ugliest bill came due in drillships. It had built five of them for a total contract price of $2.99 billion, but as the offshore drilling market collapsed, those assets simply weren’t worth what they had been worth on paper. By the end of 2019, their book value had fallen to $1.59 billion—an almost 50% haircut, and a painful reminder of how fast “high-value” becomes “stranded” when oil companies stop spending.

Out of that wreckage, Samsung Heavy’s strategy finally snapped into focus around a single bet: LNG. LNG was increasingly seen as the most realistic alternative to high-sulfur fuel oil under the IMO’s sulfur oxide emissions regulations. And unlike offshore megaprojects—where delays, supplier problems, and contract structures could blow up a balance sheet—advanced gas carriers and LNG-related ships played to Samsung’s strengths: repeatable engineering, high complexity, and a clearer path to execution.

As the industry began shifting toward environmentally friendlier vessels, the order cycle started to turn. In 2021, South Korean shipbuilders received their largest number of orders in eight years for high value-added ships—exactly the categories Samsung Heavy wanted to own.

Then came the real inflection point. In 2021, with post-pandemic recovery expectations rising and global trade picking back up, Samsung Heavy booked $12.2 billion in new orders for 80 vessels, beating its annual target by 34%. Prices were improving, too. The company suddenly had roughly two years of work in hand—a dramatic contrast to the darkest moments of the slump, when Korea’s shipbuilders couldn’t win a single order for an entire month.

The turnaround wasn’t just about orders and margins. It also reshaped leadership. In December 2022, Choi Seong-an—then CEO of Samsung Engineering—was appointed Vice Chairman and CEO of Samsung Heavy Industries at the group level. It drew attention because it was the first time in 12 years that a vice-chairman-level co-CEO had been installed.

Choi’s background was telling. He graduated from Masan High School, earned a mechanical engineering degree from Seoul National University, and started his career at Samsung Engineering. Within the group, he was seen as a trusted operator—one of only four Vice Chairmen in Samsung Group, and the first promoted to that rank under Chairman Lee Jae-yong. He has described engineering as his lifelong calling and places heavy emphasis on technology.

The appointment was, in effect, Samsung Group saying the quiet part out loud: shipbuilding still mattered—and the future of Samsung Heavy would look less like commodity ship production and more like the integration of energy-plant expertise with world-class yard execution.

IX. The LNG Renaissance & Geopolitical Tailwinds (2022–Present)

On February 24, 2022, Russia invaded Ukraine. And almost overnight, the global energy system started rewiring itself. Europe needed to wean off Russian pipeline gas. Asian buyers needed supply security. Everyone needed more LNG—and fast.

Prices had already been moving up before the war, climbing from around $2 per million BTUs toward $6. Then the crisis hit and the market ripped higher. Europeans were paying around $25. Asians were paying around $30. The exact numbers mattered less than the message they sent: LNG was no longer a niche fuel or a “bridge.” It was the emergency plan. And an emergency plan needs infrastructure—liquefaction, shipping, regasification—the whole chain.

For Samsung Heavy, this was the moment their LNG bet stopped looking like a pivot and started looking like positioning.

By late 2023, the company was sitting on an orderbook that effectively functioned like a multi-year production schedule: 132 vessels, valued at roughly $28.2 billion.

You can see that shift show up in the financials. In 2024, Samsung Heavy Industries posted operating revenue of 9.9 trillion won (about US $7.615 billion), up 23.6% year-on-year, and operating profit of 50.27 billion won, up 115.4% year-on-year. For the fiscal year ending December 31, 2024, SHI reported sales of KRW 9,903.08 billion, up from KRW 8,009.43 billion in 2023, and net income of KRW 63.88 billion—swinging back from the prior year’s net loss.

But the biggest change wasn’t just a recovery. It was a moat.

In January 2025, the Trump administration imposed sanctions on China’s Zhoushan Wison shipyard—Samsung Heavy’s only serious competitor in FLNG facility construction. U.S. authorities targeted the yard for continued delivery of LNG technology to the blocked Arctic LNG 2 project. Not long after, Zhoushan Wison Offshore & Marine was taken over by the Nantong Tongzhou Enterprise Management Partnership, a newly established entity affiliated with the Nantong City government.

The practical consequence was simple: if you were an energy major that wanted an FLNG built, your list of capable yards got dramatically shorter—right as the world’s appetite for LNG infrastructure was exploding.

Industry sources reported that four energy firms—Italy’s Eni S.p.A, U.S.-based Delfin LNG, Canada’s Western LNG, and Norway’s Golar LNG—were preparing to finalize FLNG construction contracts with Samsung Heavy. Samsung Heavy had already begun work on Eni’s Mozambique FLNG project, with the signing of an official contract described as a formality.

Delfin Midstream, meanwhile, awarded Samsung Heavy Industries an exclusive EPCI contract for its first floating LNG vessel under the Delfin LNG project offshore Louisiana. The LOA set the stage for a 2025 final investment decision, with a second vessel FID expected in early 2026.

That LNG pull has fed into broader commercial momentum, too. With its most recent contract, Samsung Heavy Industries said it had secured $7.4 billion in orders this year, including 9 LNG carriers, 9 shuttle tankers, 9 container ships, 2 ethane carriers, 11 crude oil carriers, and 1 preliminary work contract for offshore production facilities.

As of December 23, 2025, Samsung Heavy Industries still had 132 vessels on its order book, with an order backlog valued at approximately $28.3 billion. As one company representative put it: “Our profit-driven order strategy, based on a strong order backlog, has proven highly effective.”

X. Technology & Innovation: Building the Ships of the Future

If Samsung Heavy’s comeback has been powered by LNG and geopolitics, its next chapter is about something even more durable: building capabilities that are hard to copy. The company has been pushing on multiple fronts—automation, robotics, new energy systems, and the core technologies inside FLNG itself—on the theory that the next advantage in shipbuilding won’t come from cheaper steel, but from smarter ships and better execution.

The most headline-grabbing bet is autonomous navigation. In 2025, Samsung Heavy successfully completed a transpacific voyage using its in-house system, a tangible proof point in the race among Korean shipyards to lead AI-driven shipping. The Samsung Autonomous Ship (SAS) system was fitted to an Evergreen Marine 15,000 teu containership, which sailed from Oakland to Kaohsiung between August 25 and September 6, 2025.

Over the roughly 10,000-kilometer route, SAS executed 104 optimal guidance operations and 224 automated control interventions. It fused radar, GPS, and camera inputs to manage engines and rudders without crew involvement. Samsung Heavy said the system analyzed weather every three hours, then automatically adjusted route and speed to hit its schedule while reducing fuel burn.

SAS itself dates back to 2019. Samsung Heavy designed it as a full-stack autonomous navigation solution: situation awareness through sensor fusion, plus automated engine and rudder control aimed at collision avoidance. The point isn’t just a flashy demo voyage—it’s a claim that Samsung can ship not only hulls, but intelligence.

Inside the yard, that same mindset shows up as robotics. At Geoje, Samsung Heavy has rolled out specialized systems like a spider-style automatic welding robot for LNG cargo tanks, a wall-climbing vacuum-blasting robot, and a pipe inspection and cleaning robot. The company says these systems have helped it reach a 68% production automation rate—improving quality while also reducing risk for workers.

Then there’s the most futuristic swing of all: floating nuclear power. Samsung Heavy received Approval in Principle from the American Bureau of Shipping for a floating marine nuclear power platform that would feature two SMART100 small modular reactors developed by the Korea Atomic Energy Research Institute.

ABS’s approval covered a platform incorporating two SMART100 reactors, but Samsung Heavy emphasized the design’s flexibility—its concept can be adapted to accommodate different SMR types. As the company put it, the FSMR is intended to be a universal floating nuclear power facility model that can be equipped with various SMR designs.

Samsung Heavy has also developed a nuclear-powered gas carrier design. In that concept, an SMR—jointly developed at the conceptual level by Samsung Heavy and the Korea Atomic Energy Research Institute—would serve as the ship’s propulsion system. The design incorporates molten salt reactor (MSR) technology, where nuclear fuel and coolant exist in liquid form.

While those projects point to the future, Samsung Heavy has also been working on something much more immediate: tightening its grip on FLNG. The company reported a breakthrough in liquefaction technology for floating LNG production facilities, challenging a space long dominated by U.S. rivals. The system is known as SENSE IV, and in FLNG terms it’s the core—the part often described as the “heart” of the unit.

The stakes are enormous. An FLNG unit typically costs between 2 trillion and 4 trillion won to build, and liquefaction equipment can account for as much as 35% of that. Even as Korea became a shipbuilding powerhouse, the most critical FLNG components—especially liquefaction systems—have often been sourced from U.S. and European suppliers.

So proprietary liquefaction technology isn’t just an engineering trophy. It’s a direct attempt to expand margins and reduce dependence on foreign suppliers—exactly the kind of structural vulnerability that made the offshore-plant era so financially dangerous in the first place.

XI. Competitive Analysis: Strategic Positioning & Investment Framework

The FLNG Monopoly Thesis

Samsung Heavy Industries’ position today is a rare thing in global manufacturing: something close to a choke point. It holds roughly 55% of the FLNG construction market. And after U.S. sanctions sidelined its only serious rival, Samsung increasingly became the default yard for any energy major that wants offshore LNG liquefaction built at all.

That position is protected by real-world barriers, not just branding. FLNG units are some of the most complex offshore structures humans build—closer to an industrial plant bolted onto a ship than a “vessel” in the usual sense. They require capabilities accumulated over decades, plus a supplier network that can actually deliver the right equipment, on time, at the right quality. FLNG construction can require roughly three times the workforce per hour compared with conventional ships. For a newcomer, the entry ticket is brutal: billions in capital, years of experience, and credibility with customers who don’t get a second chance if a multibillion-dollar project slips.

But even protected monopolies attract attention. In the U.S., policy efforts like the proposed SHIPS for America Act—and broader talk of targeting Chinese-built vessels—reflect a renewed appetite to rebuild American shipbuilding capability. The U.S. hasn’t produced ocean-going commercial ships in meaningful numbers since the 1970s. Meanwhile, China’s scale advantage today is so large that even established shipbuilding nations like South Korea are feeling the pressure.

Porter's Five Forces Analysis

Threat of New Entrants: LOW

The barriers to entry are so high that they help explain why Korea’s government has historically been willing to support shipbuilding through downturns. A yard capable of building FLNGs isn’t something you spin up in a couple of years. It takes massive capital, specialized infrastructure, and hard-earned process knowledge. Geoje’s physical footprint—those giant docks and cranes—functions like a moat you can’t quickly replicate.

The caveat is China. Chinese shipbuilding capacity keeps expanding, and Chinese yards are pushing into higher-end segments, including LNG carriers. In 2024, China captured the majority of global shipbuilding orders and produced more than 1,000 ships. FLNG remains beyond what they can reliably execute today, but the direction of travel matters.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers: MEDIUM

The offshore boom-and-bust exposed a structural weakness for Korean yards: they were excellent at assembling, but many critical offshore components still had to be sourced abroad. Even now, while Korea has localized up to 70% of the lower hull structures on FLNGs, the topside—where much of the value sits, including liquefaction equipment—remains only about 30% to 40% localized.

Samsung’s SENSE IV liquefaction technology is aimed directly at that dependency. But the reality is that FLNG construction still runs through global supply chains, and the most critical parts can still become schedule—and margin—killers if suppliers slip.

Bargaining Power of Customers: MEDIUM

Energy majors like Shell, Eni, and QatarEnergy are sophisticated buyers. In conventional ship categories, they can play yards against each other. FLNG is different. With so few credible builders, Samsung’s near-monopoly gives it real pricing power. And for shipbuilders, the appeal is obvious: a single FLNG unit can approach 2 trillion won, and the economics can be meaningfully better than commodity ship types.

Threat of Substitutes: LOW

For LNG transportation, there’s no substitute: if the gas is liquefied and exported by sea, it needs specialized carriers.

For LNG production, the alternative to FLNG is onshore liquefaction—an option that comes with different regulatory hurdles, long construction timelines, and its own political and logistical challenges. The broader move toward floating facilities has looked more secular than cyclical.

Competitive Rivalry: HIGH

Even with an FLNG edge, Samsung operates inside one of the most competitive industrial clusters on Earth. HD Hyundai and Hanwha Ocean remain formidable, and all three chase high-value orders like LNG carriers and next-gen container ships.

There is some specialization—HD Hyundai tends to lead in container ships, while Samsung is strongest in LNG carriers and FLNG. That segmentation helps. But it doesn’t remove the knife fight for talent, capacity, and premium orders.

Hamilton Helmer's 7 Powers Framework

Scale Economies: Geoje gives Samsung meaningful scale advantages. SHI attributes part of its productivity to a more “scientific and fundamental” approach—building larger ship blocks, shortening the main engine loading period, and using ultra large cranes to maximize facility utilization. The result is unusually high throughput at massive scale.

Network Effects: There aren’t classic network effects here, but long relationships with energy majors do create advantages—better information, smoother execution, and higher switching friction.

Counter-Positioning: Samsung’s push into FLNG created a position competitors can’t easily copy. Replicating it would require similar infrastructure, know-how, and years of expensive learning.

Switching Costs: Once an FLNG project is underway, switching builders is close to unthinkable. The financial cost is enormous, but the bigger risk is schedule and technical uncertainty.

Branding: The Samsung name carries weight, even if branding matters less in industrial B2B than in consumer markets. In megaprojects, trust still has value.

Cornered Resource: Geoje itself is a cornered resource—its physical characteristics, accumulated workforce, and embedded process knowledge aren’t something a rival can reproduce quickly.

Process Power: Decades of building complex ships and offshore EPC projects translate into repeatable execution advantages. Samsung has delivered many “firsts” and “largest” projects, and that track record feeds directly into its leadership in high-tech, high-value shipbuilding.

Key Performance Indicators

If you’re tracking Samsung Heavy Industries as a business, three indicators do most of the work:

-

Order backlog and time visibility: As of June 2025, the order backlog stood at $26.5 billion, implying roughly three years of capacity visibility. This is the closest thing shipbuilding has to revenue clarity.

-

FLNG/LNG mix of orders: The more the mix tilts toward FLNG, the more profitability can improve. The expected rise in EBIT margin from 4.56% in 2024 to 6.71% in 2025 reflects that mix shift toward higher-margin floating LNG work.

-

Operating margin trajectory: In 2024, operating profit rose to 50.27 billion won, up 115.4% year-on-year. Sustained improvement here would be the clearest confirmation that the “profit-first orders” strategy is actually sticking.

Bull Case

The bull case is essentially three bets stacked together.

First, that Samsung’s near-monopoly in FLNG translates into pricing power in a market that’s still expanding. Rystad Energy expects global FLNG annual production capacity to triple from 14.1 MTPA to 42 MTPA by 2030. If that happens, Samsung is positioned to take an outsized share.

Second, that LNG remains structurally important in the energy transition. Samsung’s LNG carrier business could also benefit from U.S. policy pressure on China’s shipbuilding industry. And if export approvals expand to non-free trade agreement countries, that could unlock more final investment decisions—supporting higher vessel order prices.

Third, that Samsung’s technology investments—autonomous navigation, floating nuclear power, hydrogen carriers—create credible option value beyond today’s LNG cycle.

Bear Case

The bear case starts with concentration and cyclicality. Samsung’s recovery has been powered by LNG. If natural gas demand disappoints—or if the transition accelerates faster than expected toward renewables—order momentum and pricing could fade.

There’s also the reality of relentless domestic competition and constant regulatory change. Samsung’s reliance on a handful of high-value segments, like LNG carriers, creates real exposure if demand shifts or if a competitor closes the technology gap.

Capacity could become its own constraint, too. Korea’s shipbuilding workforce shrank sharply after the 2015–2016 crisis, and rebuilding skilled labor pools takes years. If orders surge faster than labor can return, execution risk rises.

And geopolitics can still flip the table. The Russia contract cancellation is a reminder: two orders from Russia’s Zvezda, worth a combined 4.85 trillion won ($3.54 billion), were cancelled due to what Samsung described as “illegal termination by the shipowner.”

Material Risks and Regulatory Considerations

Labor and reputation remain live risks. A union of subcontracted shipyard workers said Samsung Heavy Industries forced three migrant employees to resign despite having two-year contracts. Even when such issues don’t hit production directly, they can invite scrutiny and escalate disputes.

Safety is the constant shadow of heavy industry. On December 23, 2025, CEO Choi Sung-an apologized for a fatal accident at the Geoje Shipyard involving a subcontractor in his 50s who fell to his death. And the industry has a painful history: in May 2017, a crane collapse killed six workers, all subcontractors. These incidents aren’t just tragic—they carry operational, legal, and reputational consequences.

Finally, there’s accounting risk. Shipbuilders rely on percentage-of-completion accounting, which depends on cost estimates and assumptions about project progress. The offshore crisis showed how fast “reasonable” estimates can become wildly optimistic when delays hit and costs compound.

Conclusion: A Company Forged in Crisis

Samsung Heavy Industries’ journey—from near-collapse to something close to an FLNG chokepoint—has been one of the more dramatic turnarounds in modern heavy industry. The same company that piled up enormous losses chasing offshore oil has re-emerged as a key builder of the infrastructure now reshaping global energy.

Under CEO Choi Sung-an, Samsung Heavy set 2025 targets of KRW 10.5 trillion in sales and KRW 630 billion in operating profit. To get there, Choi has emphasized building a “future-oriented shipyard” that can run 24 hours a day—because in shipbuilding, throughput and execution discipline are often the difference between profit and pain.

Choi has also been explicit about where Samsung Heavy wants to play next. “To secure leadership in eco-friendly ships and autonomous navigation technology, we will expedite the application of ships equipped with carbon capture facilities and the commercialization of fully autonomous navigation solutions,” he said. And in the longer view: “We will prepare to become a ‘technology-centered company for the next 100 years.’”

If there’s a through-line in this whole story, it’s that Samsung Heavy’s resurrection wasn’t luck. It was learning—slowly, expensively, and in public—three lessons that shipbuilders tend to learn the hard way.

First: focus matters. The pivot from chasing every offshore opportunity to specializing in LNG and FLNG created real, defensible advantage. Second: survival in an industry with giant fixed costs and violent cycles requires both financial flexibility and, at times, government support—because when a strategic industrial base collapses, it doesn’t restart on command. Third: in a business that usually commoditizes, technological difficulty is one of the few things that can still create a moat.

For investors, Samsung Heavy is a lever on LNG infrastructure—an investment cycle that, if the world’s energy security priorities hold, could run for years. The near-monopoly in FLNG, paired with strong positioning in LNG carriers, offers exposure to that buildout. The risks are real—cyclicality, concentration, geopolitics—but so is the company’s renewed relevance.

Samsung Heavy Industries is still what it has been for decades: one of the world’s largest shipbuilders, and one of South Korea’s Big Three. But fifty years after it was created as an instrument of national development, it has become something else, too—an industrial node the global energy system increasingly routes through.

And that’s the final irony. The company was forged in one era’s national project, nearly broken by another era’s commodity boom, and rescued by a third era’s demand for complexity. Samsung Heavy didn’t just survive the cycle. It found the part of shipbuilding the world can’t easily replace—and built its future there.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music