LS Electric: The Bottleneck of the AI Revolution

I. Introduction: The "Picks and Shovels" of the AI Era

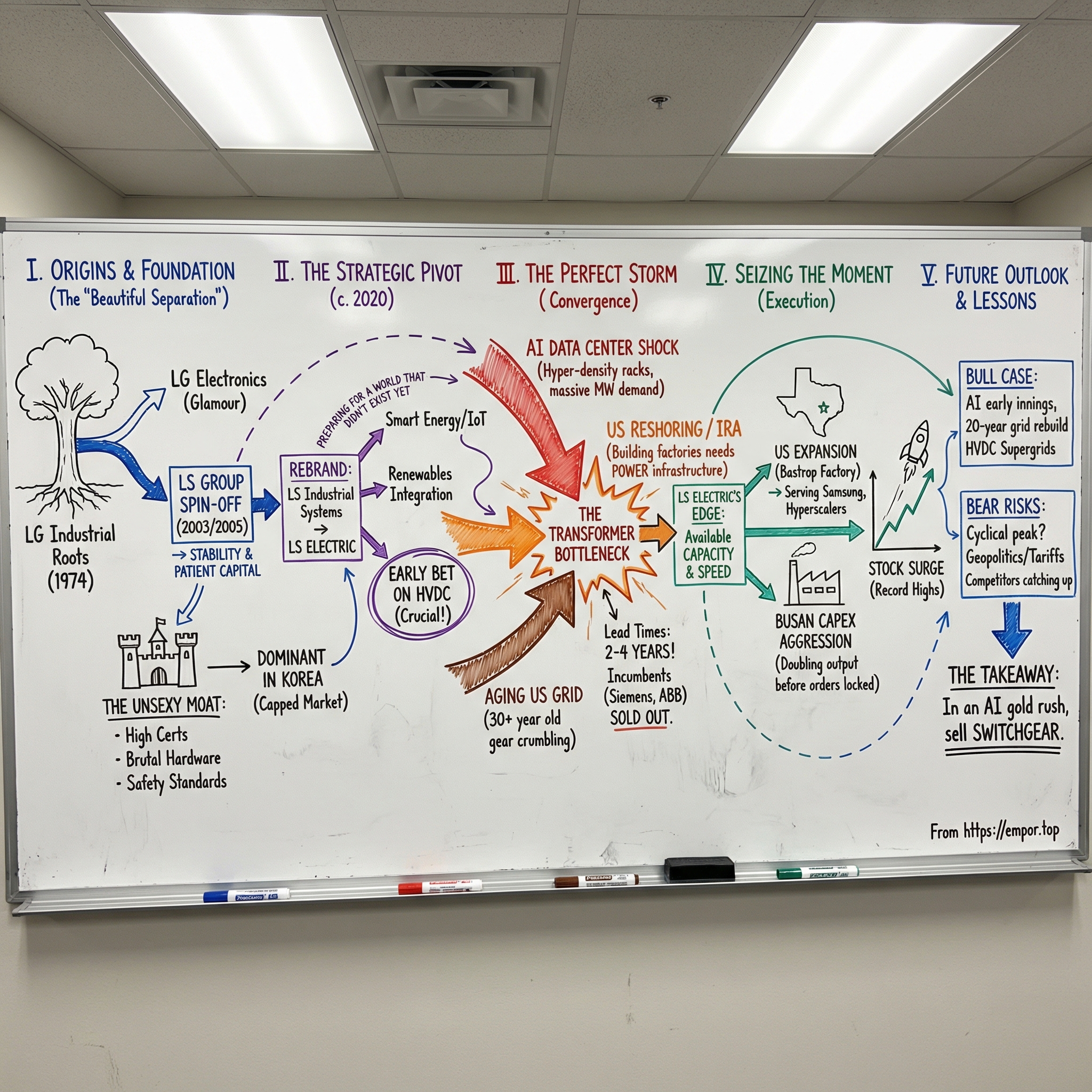

There’s a quiet irony unfolding in tech right now. Inside gleaming glass towers, executives debate the next wave of AI chips—NVIDIA’s newest releases, AMD’s push, custom silicon from Google and Microsoft. They argue over benchmarks and training runs like it’s scripture. And yet, some of the most ambitious data centers in America are stuck in limbo.

Not because the servers aren’t ready. Not because the real estate isn’t built. But because the power can’t be delivered.

In Silicon Valley, two newly built data centers reportedly couldn’t begin processing information because the electrical equipment needed to feed them simply wasn’t available. It’s a small anecdote with a huge implication: this bottleneck doesn’t get solved just by approving more generation, stringing more lines, or deploying smarter grid software. At some point, you still need physical hardware that can safely take high-voltage power and step it down, switch it, protect it, and route it—reliably, at scale, and on time.

Welcome to the Electrification Supercycle. Everyone talks about the software layer. The real constraint is lower down: in the transformers, switchgear, and circuit breakers that actually connect the grid to the machines.

And that brings us to LS Electric—a Korean industrial company most American investors have never heard of, but one that is increasingly sitting in the critical path of whether the AI buildout can happen on schedule. As one LS Electric official put it, “Being selected as the power infrastructure supplier for such a huge AI data center project proves our technological credibility in the global market.” In South Korea, LS Electric is already the dominant player in commercial data center power infrastructure, with around a 60 percent share.

The market has noticed. LS Electric’s stock hit an all-time high on July 24, 2024 at 274,500 KRW. For context, its all-time low was 8,000 KRW back on October 10, 2003—roughly a 34x move off the post-spinoff bottom. And the big surge came recently, as the transformer shortage went from industry headache to front-page problem. The shares last closed at KR₩460,000, up about 220% over the prior year, and they outperformed the FTSE Developed Asia Pacific Index by about 164 percentage points over that same period.

But this isn’t just a story about copper, steel, and a hot stock chart. It’s the story of a corporate spinoff that spent two decades building expertise the world didn’t fully appreciate—until suddenly it couldn’t get enough of it. It’s a story about patient, unusually stable family governance in a country where chaebol succession battles have destroyed fortunes. And it’s about what happens when an “unsexy” industrial manufacturer becomes one of the most strategic chokepoints in the global economy.

II. Pre-History: The LG Roots & The "Beautiful Separation"

To understand LS Electric, you first have to understand where it came from—and, more importantly, how it got out.

The roots run straight into one of Korea’s defining postwar stories: the rise of the chaebol. In 1958, Koo In-hwoi founded GoldStar, an early building block of what became LG Group. The pitch wasn’t glamour. It was rebuilding. Consumer electronics—radios, televisions, appliances—were practical symbols of a country climbing out of the wreckage of the Korean War and racing toward modernity.

And in a detail that says a lot about how industrial Korea was stitched together, LG’s origin story wasn’t even electronics-first. Its brand history points to “Lucky Cream,” often described as Korea’s first makeup cream, alongside early household staples like toothpaste and cosmetics. Before the nation could dream about semiconductors and shipbuilding, it needed everyday goods. The same families that sold those basics expanded outward—product by product, factory by factory—until they’d assembled industrial empires.

While GoldStar—later LG Electronics—captured the public imagination, a less celebrated operation was doing the heavy lifting. In 1974, Lucky Packing Co., Ltd. was established, laying groundwork in Korea’s power and automation industries. This was the industrial arm: the part of the family that built the equipment that built everything else. Switchgear, transformers, automation systems—the unglamorous infrastructure that lets a manufacturing economy run without blinking.

Over the next three decades, that industrial division—eventually known as LG Industrial Systems—grew beyond Korea, finding work across Asia and the Middle East. It quietly racked up experience in the kind of high-stakes electrical hardware where “good enough” is never good enough. If a consumer gadget fails, it’s annoying. If grid equipment fails, it’s catastrophic.

Then came the split.

In the early 2000s, LG began an unusually orderly breakup. LS Group was spun off from LG in 2003, with the separation formalizing in 2005 as the new group took shape under the broader Koo family. Around the same period, other branches of the extended family established their own lanes—most notably the Huh family’s departure to form GS Group, taking affiliates in energy, retail, and construction. Another branch later took over LG Fashion and rebranded it as LF.

What made all of this stand out wasn’t the corporate mechanics. It was the tone. Korean conglomerate history is full of succession fights—public feuds, courtroom battles, even prison sentences. LG’s reorganization, by contrast, earned a nickname: the “Beautiful Separation.” LS was co-founded by three younger brothers of LG founder Koo In-hwoi—Koo Tae-hwoi, Koo Pyong-hwoi, and Koo Doo-hwoi—who jointly stepped away, in part to avoid burdening their eldest brother with disputes over managerial control.

That ethos shaped how LS governed itself afterward. The conglomerate adopted a nine-year rotating chairmanship among cousins. Since 2004, leadership has passed through Koo Ja-yeol and Koo Ja-hong, with Koo set to take the helm in January as the next turn in the cycle.

And crucially, LS didn’t leave empty-handed. The new group took the industrial backbone businesses—cables, copper smelting, machinery—and the electrical equipment operation that would become LS Electric. In 2005, that business was renamed LSIS under the LS umbrella.

For investors, it’s tempting to treat the whole episode as corporate housekeeping. But the real legacy was cultural: stability. No scorched-earth succession war. No management reset every time family politics shifted. LS could plan like an industrial manufacturer has to plan—years ahead, sometimes decades ahead. That patience mattered, because LS Electric would spend almost 20 years building toward a moment the world didn’t know it would need—until, suddenly, it did.

III. The Quiet Years: Dominating the Peninsula

Once LS Electric was on its own, it ran into a very normal industrial problem: it was a big fish in a pond that had already been built.

By the mid-2000s, South Korea’s electrification miracle was largely complete. The grid had been expanded, modernized, and hardened over decades of breakneck industrialization. For an electrical equipment manufacturer, that’s both a compliment and a ceiling. There are only so many substations and transformers a country of roughly 51 million people needs—and once they’re in, replacement cycles can stretch for years.

Inside that capped market, though, LS Electric did something incredibly valuable: it became the default choice. It grew into Korea’s leading supplier of industrial power and automation equipment, building an installed base that functioned like a compounding advantage. When your gear is already everywhere, you tend to be the first call for the next project, the next expansion, and the next maintenance contract.

By 2016, the company employed about 3,500 people and operated seven production plants. Its lineup spanned the nuts and bolts of industrial electricity and factory automation: frequency inverters, low-, medium-, and high-voltage equipment, PLCs, HMI panels, and full production control systems.

So what does that actually mean in plain English?

Picture the electrical grid as a highway system. Power plants are the origins—where the “traffic” is generated. High-voltage transmission lines are the interstates, moving huge loads over long distances. Distribution is the local road network that finally brings electricity to buildings, factories, and homes.

LS Electric makes the on-ramps and the guardrails—and a lot of the traffic control. Switchgear directs and protects electrical flow: it decides when power moves and when it shuts off. Transformers step voltage up or down as electricity travels across the system. Circuit breakers are the fail-safes, cutting power when something goes wrong.

Over time, LS also pushed up the stack into “smarter” systems: energy management, supervisory control and data acquisition, distribution management and control, microgrid systems, and diagnostic tools. On the heavy-infrastructure side, it offered transmission systems that included substations, flexible AC transmission solutions, HVDC solutions, gas-insulated switchgear, and power transformers.

This can sound mundane—until you realize what makes this category different.

Grid hardware is brutally hard to build, and even harder to certify. You can’t ship a patch on Tuesday and hope it’s stable by Friday. This equipment runs at voltages that don’t forgive mistakes. When something fails, the downside isn’t a bad user review. It’s fires, blackouts, and real physical danger.

And contrary to what people assume, much of this gear isn’t “mass produced” in the way consumer electronics are. Major pieces are engineered to spec, tested, and certified in ways that take time. Then you have to transport and install them—often at critical sites where schedules are already tight.

All of that creates natural barriers to entry. There are no “two guys in a garage” disrupting high-voltage switchgear. The capital requirements are high, the regulatory hurdles are punishing, and the safety standards are non-negotiable. And once a utility or industrial customer commits to a vendor, switching is painful: crews get trained on that platform, spare parts are stocked for years, and maintenance workflows are built around it.

But even with a dominant home base, growth was the unsolved riddle. To break out of the domestic ceiling, LS Electric had to take on the global incumbents—ABB, Siemens, Schneider Electric, Eaton—companies with decades of customer relationships and manufacturing footprints already in place. As Koo said in a group interview, “Compared to the Big Four power system suppliers in the US — Schneider Electric, Siemens Energy, Eaton Corporation and ABB — LS Electric delivers to clients more than twice as fast and at more competitive prices.”

That value proposition opened doors in places like Southeast Asia and the Middle East. But the biggest prize stayed stubbornly out of reach. In the United States, the market ran on entrenched relationships and local production. LS Electric could compete. It just wasn’t yet considered essential.

The stock told the same story. Through most of the 2010s, LS Industrial Systems—as it was then known—traded sideways, priced like what it appeared to be: a steady, “boring” industrial manufacturer with limited growth and limited pricing power.

Investors weren’t wrong about what LS Electric was at the time.

They were wrong about what the world was about to demand from it.

IV. Inflection Point 1: The "Smart" Pivot & The Rebrand

In March 2020, while the world was shutting down for COVID-19, LS Industrial Systems made a move that looked—at first glance—like pure optics: it changed its name.

“The proud name of LS Industrial Systems, which had been used during the company's growth into a leading company in the fields of industrial power and automation, has completed its mission,” Koo said at the time. “With the new name of LS Electric, we must make new history with a strong sense of responsibility and duty. Let's take off to be a global electric power equipment company.”

But this wasn’t just a fresh coat of paint. The company’s own explanation was blunt: “Industrial Systems” sounded like a business boxed into factory power and automation. LS wanted to be seen as something bigger—an energy company built for an era of digital transformation and artificial intelligence.

That push came from Chairman Koo Ja-kyun. Born in Seoul in 1957, he’s the third son of Koo Pyeong-hoe, the younger brother of LG founder Koo In-hoe. He earned a doctorate in business administration—focused on corporate finance—from the University of Texas at Austin in 1990.

And unlike the typical chaebol heir story, Koo didn’t start out sprinting toward the executive suite. He went academic first: appointed a professor at Kookmin University in 1993, then moving to Korea University’s Graduate School of International Studies in 1997. Scholar before operator.

He eventually moved into the business, serving as President of LS Industrial Systems in 2008, then becoming Chairman and CEO in 2014. He developed a reputation as a principled leader with a calm, understated charisma—exactly the kind of temperament you want running a company that can’t afford mistakes.

Under Koo, LS Electric wasn’t trying to become “smarter” in a press-release sense. The shift was structural. The company set out to evolve from selling discrete pieces of hardware into delivering broader solution platforms—built on the convergence of manufacturing technology, ICT, and IoT. The goal wasn’t just better devices; it was smarter transmission and distribution networks, Industry 4.0-style factory systems, and end-to-end offerings that bundled equipment with software and services.

Concretely, LS began leaning hard into three areas: renewable energy integration (solar and wind inverters), IoT-enabled smart equipment, and—most consequentially—DC technology.

That last bet matters. The modern grid runs on AC, the winner of the War of Currents. But DC has real advantages in the places the future is heading: long-distance transmission, renewable integration, and data centers. HVDC systems convert AC into DC to move power efficiently over long distances, then convert it back near where electricity is consumed.

LS Electric is Korea’s sole supplier of HVDC high-voltage transformers. And crucially, this wasn’t a “someday” ambition. The company built an HVDC transformer factory in Busan in 2011—the first of its kind in Korea.

Back in 2020, though, none of this got much credit. “Smart energy.” “Digital transformation.” It sounded like buzzwords stapled onto a mature industrial business, and the stock reflected that skepticism. Investors largely saw trend-chasing, not conviction.

What they missed was that LS wasn’t only talking. It had been placing bets with real money for years. The company described the shift this way: “While managing LS ELECTRIC, we reorganized the business structure centered on the single device business that supplies power facilities for factories to a total solution center that supplies devices as well as solutions en bloc, pioneering overseas power automation infrastructure markets and expanding the smart energy business, the next-generation business.” And starting in 2009, it pursued a series of mergers and acquisitions in automation equipment and power parts to support that direction.

So the 2020 name change wasn’t the strategy.

It was the signal that the strategy was already in motion—and that LS was building for a world that, very soon, would stop treating power infrastructure as background noise.

V. Inflection Point 2: The Perfect Storm

From 2022 through 2024, LS Electric caught the kind of tailwind industrial companies spend decades waiting for. Three forces hit at once—and instead of canceling each other out, they compounded.

First, the U.S. decided it wanted to build things at home again. Second, it realized the grid holding the whole economy together was aging out. And third, AI arrived with power demands that made yesterday’s forecasts look quaint.

Put together, it turned a Korean switchgear and transformer specialist into something far rarer: a company with available capacity, at the exact moment capacity became the scarce resource.

The Inflation Reduction Act and U.S. reshoring

In August 2022, President Biden signed the Inflation Reduction Act, the biggest climate bill in U.S. history. But to the electrical equipment world, the IRA was also an industrial policy bill. Tax credits came with domestic content strings attached. If manufacturers wanted incentives, they needed to build in America.

And when you build factories—especially semiconductors, automobiles, batteries, and appliances—you don’t just need land and labor. You need serious power infrastructure. Distribution systems, substations, switchgear: the unglamorous hardware that turns “a factory in Texas” from a press release into something that can actually run.

That demand surge wasn’t theoretical. Korean manufacturers, navigating rising U.S.–China tensions, began building more production capacity in the U.S. And every new plant pulled more demand through the same supply chain LS Electric lived in.

The aging grid

At the same time, the U.S. grid was entering a replacement cycle it had delayed for years. More than a third of industrial transformers in the U.S. had already been in service for over 30 years—right at the edge of their typical 30-to-40-year life. On the distribution side, more than half of transformers, an installed base measured in the tens of millions, were estimated to be past their expected service life. And by some estimates, over 70% of U.S. grid infrastructure was more than 25 years old.

This wasn’t a failure of engineering. It was a failure of timing and investment. During years of energy abundance, utilities underinvested in maintenance and replacement. Manufacturing capacity didn’t just fail to keep up—it withered. So when the replacement wave arrived, there wasn’t enough factory output waiting on the other side.

The AI data center shock

Then AI kicked the door in.

Electricity demand projections started getting rewritten upward, fast. Data centers, electrification, and reshored manufacturing were expected to push U.S. grid-based electricity consumption meaningfully higher by the end of the decade, with even higher scenarios depending on how aggressively data center operators expanded.

Globally, data centers’ energy footprint was forecast to more than double by 2030, climbing from roughly 415 terawatt-hours in 2024 to nearly 945 terawatt-hours. That jump doesn’t happen on software alone. It happens through transformers—at the campus level, and all the way down to the distribution feeding the racks.

And the racks themselves were changing. Traditional deployments might sit around 10 to 15 kW per rack. AI-focused builds were crossing 100 kW per rack, with some hyperscale designs pushing beyond a megawatt per pod. That kind of density doesn’t just strain the grid. It changes what “normal” power equipment demand looks like.

The transformer shortage

Once those three trends converged, the industry got its own version of a pandemic-era supply shock—what some started calling the “toilet paper crisis of the utility world.”

Lead times stretched into the multi-year range. In 2024, the North American Electric Reliability Corp. put average lead time at roughly 120 weeks—more than two years—with large power transformers taking as long as 210 weeks, or up to four years. Wood Mackenzie estimated that since 2019, demand had surged—up 116% for power transformers and 41% for distribution transformers—and modeled persistent deficits into 2025, including an estimated 30% shortfall for power transformers and 10% for distribution units.

Prices followed predictably. Utilities reported transformers costing several times what they did before 2022, on top of the wait.

In other words: even if you had the budget, you might not be able to get a manufacturing slot.

LS Electric’s moment

This is where LS Electric’s long, patient build suddenly mattered.

While incumbents like Siemens and ABB were effectively sold out with backlogs stretching years ahead, LS Electric had capacity—and it moved.

The company’s U.S. push centered on Texas. LS Electric bought a factory site in Bastrop, and the location was strategically convenient: about 55 kilometers from Samsung Electronics’ foundry project in Taylor. LS Electric had already signed a contract in November to supply a distribution system worth 174.6 billion won (US$134.0 million) to that Taylor facility.

And Samsung wasn’t the only target. LS Electric expected major demand from Korean manufacturers with North American footprints, including LG Energy Solution, SK on, and POSCO Chemtech. It was already supplying distribution systems to the EV battery joint factory SK on and Ford were building in Kentucky, and to joint factories LG Energy Solution and GM were building in Ohio, Tennessee, and Michigan. With that order momentum, the company reported North American sales in the first quarter rising sharply year-on-year to 923 billion won.

In 2023, LS Electric acquired a roughly 46,000-square-meter site in Bastrop to build out manufacturing, R&D, and design capabilities. Then, on April 14, 2025, it held the grand opening of its new Bastrop Campus at 409 Technology Drive. The new 58,925-square-foot facility was positioned as a technical center to support expanding U.S. operations, including what LS described as a recent $150 million contract with Samsung.

The point wasn’t symbolism. It was leverage. Bastrop was meant to be a base for serving local data centers and the wider surge in U.S. power infrastructure demand. By manufacturing locally, LS Electric aimed to cut tariff exposure, reduce supply-chain risk, and meet the reality of “Buy American” procurement.

And it wasn’t stopping there. LS Electric also planned to invest an additional $240 million by 2030 to expand the site, hire locally, and scale.

The logic was straightforward: in a world where power equipment lead times had become a multi-year bottleneck, being able to build inside the U.S. wasn’t a nice-to-have.

It was the product.

VI. The Power Systems: Tech & Strategy

To understand why LS Electric is showing up in so many “must-have” conversations right now, you have to zoom out from the company itself and look at two things: the ecosystem it lives inside, and the way it’s reshaping its product strategy for the new grid.

The K-Electric Alliance

LS Electric doesn’t operate in isolation. Inside LS Group, it has a powerful sibling: LS Cable & System—the company that makes the literal arteries of the grid, the cables that carry electricity across land and sea.

LS Cable & System is one of the largest cable manufacturers in the world, with a product lineup spanning power and telecommunications cables, integrated modules, and industrial materials. It also goes beyond manufacturing, providing engineering services and handling installation, commissioning, and full turnkey delivery for high-voltage and extra-high-voltage projects, including submarine cabling.

The partnership becomes especially potent in HVDC. LS Cable & System is the only company in South Korea with experience executing both submarine and underground HVDC projects, and it has carried out all domestic HVDC cable projects—Jeju–Jindo, Jeju–Wando, and Bukdangjin–Godeok—serving as the sole supplier across the full length of the current project.

Put simply: LS Cable can deliver the highway. LS Electric delivers the interchanges—transformers and the conversion equipment that makes HVDC work in the real world. Together, that turns them into a one-stop shop for major grid infrastructure builds.

The EV Strategy

LS Electric also isn’t betting only on substations and data centers. It’s pushing into the electric vehicle value chain through its subsidiary, LS e-Mobility Solutions.

As of April 1, 2022, LS e-Mobility Solutions relaunched with a stated mission: provide innovative solutions for the global eco-friendly EV industry. The focus is very LS Electric in spirit—high-reliability electrical switching, just moved from the grid into the car. The unit specializes in EV relays and complete battery disconnect units (BDUs).

Manufacturing is centered on the Durango plant, with a gross floor area of about 35,000 square meters. At full run-rate, the facility is designed to produce up to 5 million EV relays and 4 million BDUs per year. Since a typical EV can require 20 relays or more, that output translates to relay capacity for roughly 250,000 vehicles annually.

This is diversification, but not a random one. Relays and disconnect units are, at their core, the same promise LS has always sold: when electricity is flowing at high stakes, you need something that switches instantly, predictably, and safely. LS e-Mobility Solutions has also secured a supply contract valued at 250 billion won (about $187 million) to provide relays for electric vehicles from Hyundai Motor and Kia.

The Capacity Expansion

Underneath all the positioning and new markets, the most important thing LS Electric is doing is the least glamorous: building more capacity. And specifically, building more transformer capacity—where the global bottleneck is tightest, and where ultra-high voltage and HVDC capability is hardest to replicate.

LS Electric announced plans to double production capacity for high-voltage transformers at its Busan plant, backed by an 80.3 billion won (about $58.9 million) investment. The goal is straightforward: strengthen its foothold in both distribution and transmission, and be able to say “yes” to global demand when others are forced to say “get in line.”

Alongside that, the company invested 100.8 billion won (about $68.5 million) in a new 18,059-square-meter facility—about 1.3 times larger than the existing one—which expands total output capacity by three times. The practical implication is scale: annual production of ultrahigh-voltage transformers is set to rise from 200 billion won to 600 billion won, and the Busan site is targeting more than 1 trillion won in standalone sales next year. The facility currently produces transformers with annual capacity valued around $150 million, with expectations to increase to roughly $525 million by 2027 as expansion comes online.

In a shortage market, this is what market power looks like: not a clever slogan, but a bigger factory with the right equipment.

The "Chasm" Strategy

All of this ladders into LS Electric’s most consequential strategic shift: how it positions itself against the Western incumbents.

Koo has been unusually direct about the pitch. “Compared to the Big Four power system suppliers in the US — Schneider Electric, Siemens Energy, Eaton Corporation and ABB — LS Electric delivers to clients more than twice as fast and at more competitive prices,” he said. He pointed to a specific pressure point: U.S. demand for high power-density distribution systems for server racks—exactly the kind of equipment data center builds now require, and exactly where legacy suppliers have struggled to keep up.

The company’s edge, in its own words, is “fast and precise” customization, to the point that Koo says some U.S. clients have asked for exclusive supply agreements. LS Electric is also the first Korean company to complete UL certification for its power distribution panels, a key requirement for meeting U.S. safety and performance standards.

This is the chasm-crossing move in real time. LS Electric is trying to evolve from being the cheaper alternative to Siemens into being the partner you choose because they can deliver—period. When competitors are quoting lead times measured in years, speed stops being a nice feature.

It becomes the brand.

VII. The Playbook: Lessons for Builders

LS Electric’s rise looks sudden on a stock chart. In reality, it’s the payoff from a set of decisions that rarely get celebrated—because they’re slow, operational, and unglamorous. If you’re a builder, a strategist, or a long-term investor, there’s a lot to steal here.

The "Turtle" Strategy

LS Electric didn’t chase the dot-com boom. It didn’t try to reinvent itself as a crypto play. It didn’t slap “software” onto its name and hope the market rerated it.

For decades, it stayed in heavy industrial manufacturing—exactly the part of the economy that felt out of style while “software is eating the world” became the dominant narrative.

But this wasn’t stubbornness. It was deliberate compounding. LS kept investing in R&D, stacking up certifications, and expanding capacity in increments that looked boring in the moment. Then the cycle snapped back. Suddenly, hardware wasn’t a commodity—it was the constraint. And LS Electric already had the installed base, the engineering muscle, and the manufacturing footprint to deliver when delivery became the whole game.

Spin-off Success

LS Electric is also a clean example of why spinning out divisions can unlock value that conglomerates leave trapped.

Inside LG, the industrial systems business lived in the shadow of consumer electronics. It wasn’t the headline act, and it didn’t get treated like one. Once it became its own company under LS, the incentives changed. Management attention sharpened. Capital allocation started reflecting the realities of electrical equipment markets, not the priorities of a sprawling group.

Independence didn’t magically make LS Electric better at making switchgear and transformers. It let the company run its own race—and invest on its own timelines.

CapEx Timing

LS Electric’s expansion decisions were, in a quiet way, the boldest part of the whole story.

Building out Texas and expanding Busan meant committing capital before the full order book was locked in. Most industrial companies do the opposite: they wait for contracts, then they build, then they deliver—late.

LS Electric leaned forward. It has already secured orders for high-voltage transformers through 2026, and the Busan plant was running at a 95.6 percent operational rate in the first quarter of 2024. In other words, the bet wasn’t reckless—it was informed.

But the deeper point is strategic: in a supply-constrained market, capacity isn’t just an operating metric. It’s a weapon. The companies that can say “yes” win the contracts. LS Electric bet demand would show up, built for it, and earned the right to be the alternative when everyone else was quoting lead times measured in years.

The "Unsexy" Moat

There’s a reason you don’t see startups “disrupting” high-voltage transformers.

Building hardware is hard. Building high-voltage hardware that has to work every time, in every condition, without failure is brutally hard. The supply chain is tight, the testing is unforgiving, and certifications take years.

Transformer production also depends on specialized inputs. In the U.S., most transformer cores use grain-oriented electrical steel, a material with specific magnetic properties that’s produced domestically only by Cleveland-Cliffs at plants in Pennsylvania and Ohio.

When your materials are concentrated, your qualification cycles are long, and the cost of failure is catastrophic, the barriers to entry aren’t marketing slogans—they’re physics, regulation, and time. It’s not sexy. But it’s durable. And in moments like this, it becomes priceless.

VIII. Analysis: Powers & Forces

If you run LS Electric through the classic strategy frameworks, you start to see why this moment may be less “hot cycle” and more “structural advantage” than it looks at first glance.

Porter's 5 Forces

Threat of New Entrants: Low

Electrical equipment manufacturing has brutal barriers to entry. This isn’t consumer hardware where you spin up a contract manufacturer and iterate. Much of the gear has to be designed to spec, then tested and certified to demanding standards, unit by unit. A new entrant would need years to build factories, qualify processes, win certifications, and—most importantly—earn trust with utilities that can’t afford failures. You cannot “move fast and break things” with 345kV power lines.

Supplier Power: Medium

Inputs like copper and steel swing in price, and they matter. But LS Electric has shown it can pass those costs through, especially in today’s supply-demand imbalance. Since 2019, unit costs have climbed meaningfully across transformer categories—generation step-up, power, and distribution. In a market where customers are fighting for delivery slots, “cost-plus” becomes less a negotiation and more the price of staying on schedule.

Buyer Power: Shifted

This is the big change. Historically, utilities and large industrial buyers had leverage: competitive bidding, long vendor lists, and the ability to squeeze margins. Today, the leverage has moved up the supply chain. As one industry official put it, “The situation has shifted to a supplier's market.” Even with tariffs, buyers are willing to pay more because the real risk isn’t price—it’s not getting the equipment at all.

Hamilton's 7 Powers

Scale Economies

Scale matters here in the most literal way: specialized factories, specialized tooling, and specialized testing. Expanding high-voltage transformer output requires serious fixed investment—foundries, test labs, and production lines built around equipment that can’t be improvised. LS Electric’s upgraded plant includes high-end process infrastructure like vacuum drying ovens, dedicated assembly areas, test rooms, and welding shops—everything needed to run the full transformer production chain.

Those vacuum drying ovens are a good example of why this is hard to replicate quickly. They improve insulation performance and cut failure risk by pulling moisture out under deep vacuum at around 120 degrees Celsius for more than 72 hours. That’s not “nice to have.” That’s what separates reliable grid equipment from expensive scrap.

Switching Costs

Once a utility standardizes on a vendor’s switchgear, it doesn’t casually swap. Crews are trained, spare parts are stocked, maintenance routines are written, and operating procedures are built around the installed base. Changing suppliers is costly, time-consuming, and—because failure is catastrophic—psychologically hard. Even if a competitor offers a discount, the risk-adjusted cost can be higher.

Cornered Resource

In 2024 and 2025, the cornered resource isn’t a patent or a distribution channel. It’s manufacturing slot availability.

Companies like HD Hyundai Electric, LS Electric, and Hyosung Heavy Industries have secured transformer contracts stretching years into the future, with some order books extending as far as 2031. When the market is effectively sold out, the firms that can still say “we can build it” are holding something incredibly scarce—and incredibly valuable.

Competition Landscape

LS Electric plays in a global arena with heavyweight incumbents. In switchgear, the usual names dominate the conversation—ABB, Schneider Electric, Siemens, Eaton, Hitachi. It’s a crowded field at the top, with the leading players collectively holding only a minority share of the overall market, which tells you two things at once: the category is competitive, and it’s fragmented enough that execution and delivery can still create real openings.

Back home in Korea, the fight has intensified because North American transformer demand has become a once-in-a-generation pull. More demand offshore means more Korean suppliers chasing global customers—and more competition for who becomes the default partner as U.S. utilities and hyperscalers scramble to secure equipment.

The most direct domestic rival is HD Hyundai Electric, a major Korean producer of power transformers and related electrical equipment. By 2017, it had supplied a cumulative total of over 1.2 million kWA transformers to 70 countries. In recent quarters, it’s posted strong growth, reached a double-digit operating margin for the first time since its 2017 separation, and landed major orders—including a record transformer deal in the U.S. with Xcel Energy.

Against that backdrop, LS Electric’s differentiation is clear and specific: it is Korea’s sole supplier of HVDC high-voltage transformers, it claims materially faster delivery than Western incumbents, and it moved early to establish a U.S. manufacturing foothold while demand was becoming a national constraint—not just a customer problem.

IX. The Bear & Bull Case

Every great run creates its own story. For LS Electric, that story is the electrification supercycle: AI, data centers, grid replacement, reshoring—everything hitting at once. The real question is whether this is a durable shift, or a moment in time that looks permanent only because it feels urgent right now.

The Bear Case

Cyclical Peak Risk

Electrical equipment has always been a cyclical business, even if it doesn’t feel like it when lead times stretch into years. If AI capex cools, reshoring loses momentum, or utilities push upgrades down the road again, demand could snap back toward normal faster than the market expects. And when the bottleneck loosens, the “must-have supplier” narrative can soften quickly.

Geopolitics

LS Electric sits in a market where policy is part of the competitive landscape. U.S.–Korea trade dynamics can change with elections. If the IRA is revised, if tariffs expand, or if “Buy American” rules tighten, LS could find itself disadvantaged versus domestic manufacturers—especially in the very projects it’s been building its U.S. footprint to win.

Competition

Today, Chinese giants like TBEA and XD Electric are largely boxed out of the U.S. market. That protection isn’t guaranteed forever. At the same time, Korean rivals aren’t standing still. HD Hyundai Electric and Hyosung are pushing into the same demand wave, and Hyundai Electric has said it plans to expand its Alabama plant by 2027 to increase 765 kV transformer output.

Margin Pressure

Right now, suppliers have leverage because capacity is scarce. But scarcity invites investment. Since 2023, many large OEMs have announced North America-focused capacity expansions totaling $1.8 billion. As more production comes online, today’s pricing power could fade. The market may still need additional investment to fully rebalance, but the direction of travel matters: more capacity usually means less margin.

The Bull Case

AI Is Just Getting Started

The power behind AI isn’t metaphorical. Global data center power demand is projected to climb at a double-digit annual pace from 2023 to 2028, and AI-heavy deployments could drive growth much faster. The bigger idea is simple: the AI race is a compute race, and compute is an electricity race. If the current buildout is early innings, the grid equipment backlog isn’t a spike—it’s the start of a long pull.

The 20-Year Rebuild

Even without AI, the U.S. grid has replacement written all over it. This is not a two-year patch job. The transformer market alone is forecast to more than double between 2023 and 2034, growing from $12.2 billion to $25.7 billion. That’s the kind of horizon where “cyclical” starts to look more like “secular.”

Geographic Diversification

LS Electric’s opportunity isn’t limited to the U.S. The company is expanding across Vietnam, Europe, and Southeast Asia. That matters because it reduces the risk of being overly exposed to one policy regime, one customer set, or one boom-and-bust cycle.

Backlog Visibility

At a time when many industrial companies live quarter to quarter, LS Electric has something closer to a roadmap. Its backlog exceeds 3.9 trillion won. That doesn’t eliminate risk, but it does mean a meaningful portion of future revenue is already spoken for. This isn’t just optimism about demand—it’s contracts.

Valuation Gap

Even after the stock’s run, there’s an argument that LS Electric still trades below Western peers once you adjust for growth and opportunity. If the company continues moving from “value option” to “preferred partner,” that gap may not hold.

Key KPIs to Watch

For investors tracking LS Electric, three numbers matter more than the headlines:

-

North American Revenue Mix: How much of revenue is coming from North America. It’s the best single signal of whether LS Electric is truly breaking into the highest-stakes, highest-value market—and whether it’s doing so with pricing power, not just volume.

-

Order Backlog Ratio: Backlog relative to the last twelve months of revenue. If that ratio keeps rising, demand is still outrunning supply. If it starts falling, the market may be normalizing.

-

Gross Margin Trend: Margins are the tell. Expansion suggests scarcity and pricing power are holding. Compression suggests competitors are catching up, customers are regaining leverage, or both.

X. Epilogue & Future Outlook

The next frontier for LS Electric—and for the electrical equipment industry more broadly—runs through two ideas that sound futuristic until you realize they’re already being built: supergrids and HVDC.

Consider Korea’s West Coast Energy Highway Project. The plan is a 620-kilometer string of undersea transmission links running up the west coast, moving renewable-heavy power from Honam toward the metropolitan load centers. It was originally slated to finish in 2036. The government later pulled the target forward to 2030, and set aside about $8 billion (₩11.5 trillion) to make it happen.

This is exactly the kind of project HVDC was made for. Global demand for HVDC systems—estimated at 1.8 trillion won in 2018—is expected to balloon to 41 trillion won by 2030. The appeal is straightforward: HVDC can transmit up to three times more power than traditional high-voltage alternating current cables, with lower losses over long distances.

LS Electric has been planting flags here for years. Since becoming Korea’s sole HVDC converter supplier in 2013, it has secured four major projects worth nearly $700 million (₩1 trillion). It’s also working to localize HVDC valve technology through a partnership with GE Vernova, supporting Korea’s push for self-reliance in core grid infrastructure.

And the logic extends far beyond Korea. As countries sprint toward renewables, they keep running into the same physical constraint: the best solar and wind resources are rarely near the cities that need the electricity. The fix isn’t only more generation. It’s moving power efficiently across distance—often across water, mountains, or national borders. That’s where HVDC becomes the backbone of the next grid.

LS Electric’s bet—manufacturing experience, domestic reference projects, and partnerships with global leaders—sets it up for that next phase of grid evolution.

There’s something quietly poetic about it. A company born out of Korea’s postwar industrial scramble is now helping power the most advanced computation on earth. The “Lucky Packing” factory of 1974, turning out basic electrical equipment for a developing nation, has evolved into a supplier of ultra-high-voltage transformers and power systems for hyperscale data centers.

The path wasn’t glamorous. For decades, LS Electric did the kind of work that rarely makes headlines. Its stock sat still while software companies earned premium valuations. Management kept investing in heavy industrial manufacturing while the world acted like everything important had gone digital.

Then the world flipped. The AI revolution didn’t just need smarter models; it needed more megawatts. The energy transition didn’t just need solar panels; it needed rebuilt transmission networks. Reshoring didn’t just need political speeches; it needed factories that could actually turn on.

And in that moment, a company that had spent half a century mastering electrical hardware turned out to be exactly what the world was missing.

In a gold rush, sell shovels. In an AI rush, sell switchgear.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music