HD Korea Shipbuilding & Offshore Engineering: The World's Mightiest Shipyard

I. Introduction: The Empire Built on an Impossible Promise

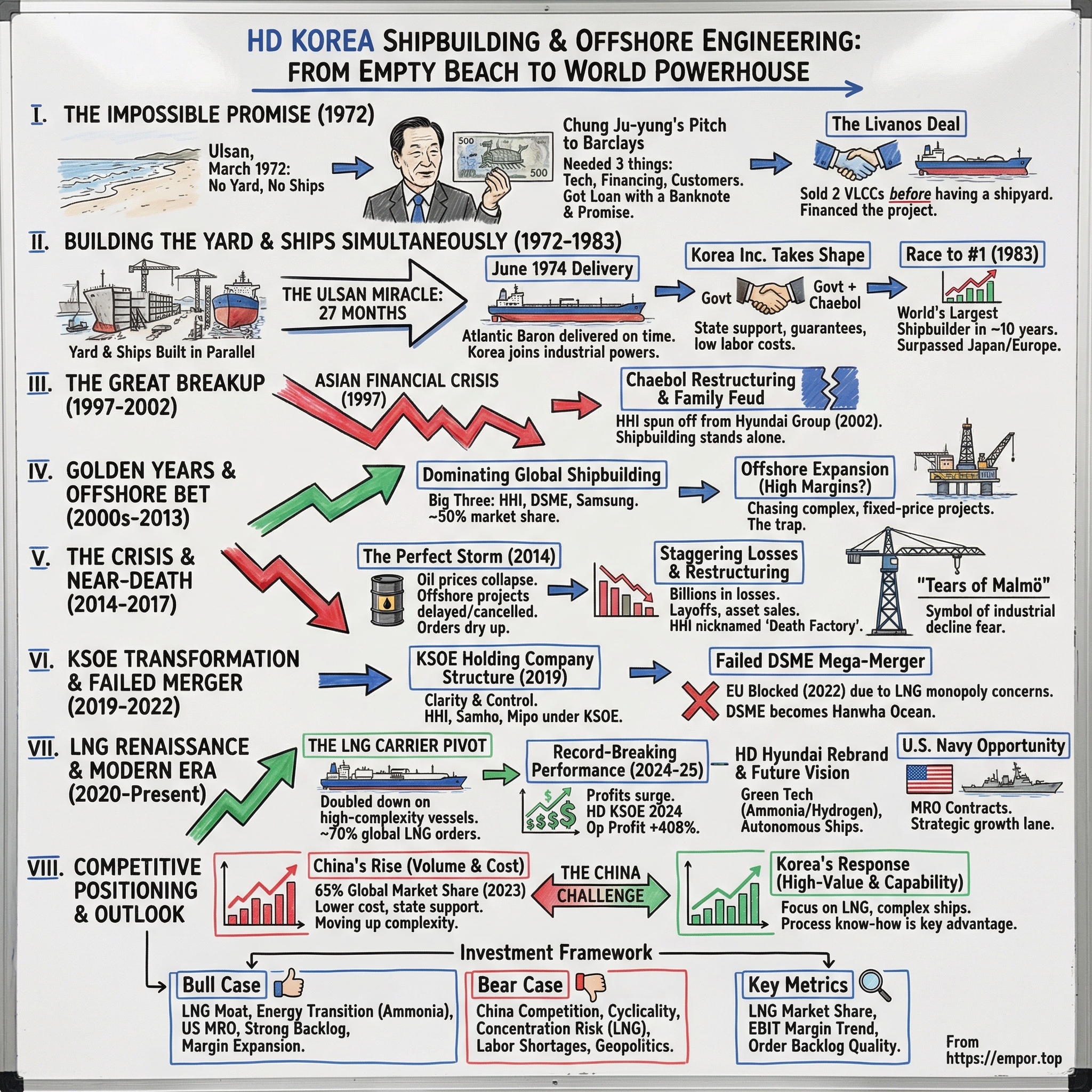

Picture a barren stretch of beach on South Korea’s southeastern coast in March 1972. No cranes. No dry docks. No power lines or workshops—just sand, mud, and the chop of the East Sea. And standing there was Chung Ju-yung: a peasant-turned-construction magnate who decided he was going to build a shipyard from scratch and, somehow, sell the world on it.

The catch was that Hyundai didn’t have shipbuilding experience, didn’t have shipbuilding technology, and didn’t have a shipyard. Chung had already persuaded British lenders to back the idea. Now he had to make the impossible real—fast. What followed didn’t just create a company. It helped redraw the map of global manufacturing, challenged the old shipbuilding powers in Japan and Europe, and set South Korea on a path toward becoming the world’s most formidable shipbuilding nation.

Jump to the present, and the scale is almost hard to reconcile with that empty shoreline. In 2024, HD Korea Shipbuilding & Offshore Engineering generated about 22.07 trillion won in revenue from its shipbuilding segment. As a key holding company within HD Hyundai, HD KSOE sits over the group’s major shipbuilders—HD Hyundai Heavy Industries, HD Hyundai Mipo, and HD Hyundai Samho—coordinating strategy across yards that collectively build some of the most complex vessels on Earth.

But this isn’t a smooth, upward-only success story. It’s a tale about founder audacity and national ambition—yes—but also about what happens when a brutally cyclical global industry turns, and when strategic bets go wrong. In 2024, HD Hyundai Heavy Industries reported a nearly 50 percent increase in operating profit alongside more than 10 percent growth in consolidated revenue. Within shipbuilding, HD KSOE’s profits surged roughly fourfold to more than $960 million. Those are numbers that signal momentum—but they also come after years when survival itself was the question.

Because today, the battleground has shifted. China has dramatically expanded its share of global shipbuilding orders, reaching 71% in 2024, while South Korea’s share fell to 17%. South Korea’s edge has increasingly narrowed to where it’s always been strongest: high-value ships, especially LNG carriers. The company that once looked untouchable has had to evolve—leaning into technical sophistication and specialization while rivals win on scale and state-backed volume.

So this is the story we’re telling: how one man, armed with a 500-won banknote and sheer force of will, sparked an industrial revolution; how his creation nearly buckled under the weight of its own ambition; and how it fought its way back. A cautionary tale, a blueprint for resilience, and one of the most consequential business stories of the modern industrial era.

II. The Founder and The Impossible Pitch

The Chung Ju-yung Origin Story: Poverty, Persistence, and Peasant Wisdom

Chung Ju-yung was born on 25 November 1915 in Tongchon County, in what is now North Korea. His father farmed for a living. The family was poor. And as the eldest of eight children, Chung grew up carrying responsibility long before he carried any kind of title.

His early life reads less like a CEO biography and more like a parable about impatience and grit. At sixteen, he and a friend tried to make their way to Seishin to find work and escape farm life. It didn’t stick. He tried again, and again—each time his father hunted him down and dragged him home.

On the third attempt, Chung made it. He sold one of his father’s cows to pay for the trip, a choice that would haunt him with guilt for the rest of his life. In Korea, that detail became legend: not because it was noble, but because it was brutally human. It captured the mix of desperation and determination that would define him.

He arrived in Seoul with almost nothing. He worked construction jobs, then found his way into an automobile repair shop, and eventually started his own. He earned his money the hard way—“born a peasant who left home to labour on building sites and then to form his own construction company.”

After Korea’s liberation from Japanese control, Chung moved fast. In 1946, he launched Hyundai and Hyundai Civil Industries, aiming squarely at the country’s coming wave of reconstruction and industrialization. He won government contracts and built his way into the center of South Korea’s industrial rise. By the late 1960s, Hyundai Engineering & Construction had become one of the country’s biggest companies, responsible for major dams and the Seoul–Busan expressway. Chung was wealthy, connected—and, as always, looking for the next mountain.

The London Gambit: Convincing Bankers with a Banknote

In 1971, Chung decided to enter shipbuilding. Inside Hyundai, it sounded like madness. The company had no shipbuilding experience, no shipbuilding technology, and no shipyard. South Korea, meanwhile, had built virtually nothing on the scale he was talking about—before the 1970s, the country had built no ships larger than 10,000 tons.

But Chung wasn’t looking for permission. He needed three things—technology, financing, and customers—and he went after all three at once.

He met Charles Longbottom of A&P Appledore, a British ship consulting firm, and secured a recommendation letter. With that in hand, he went to Barclays to pursue a $43 million loan. The bankers’ skepticism was obvious: why finance a shipyard in a country with no track record?

Here’s where the story turns into business folklore. Chung reportedly pulled out a 500-won note and pointed to the image of a 16th-century Korean ironclad warship on it. The message was simple: Korea had built ships before. Korea could build ships again.

Whether the bank was truly convinced by the history lesson or by the sheer force of the man delivering it, the pitch worked well enough to keep the process moving. But there was still a hard requirement standing between Chung and the money: Britain’s Export Credit Guarantee Department needed proof of real demand. He didn’t just need a loan. He needed an order.

The Livanos Deal: Selling Ships Before You Have a Shipyard

That created the classic chicken-and-egg problem. Chung needed financing to build a shipyard. He needed a ship order to unlock financing. So he did the only thing he could do: he sold the ships first.

Hyundai accepted an order for two 260,000-tonne oil tankers from Greek magnate George Livanos—before Hyundai even had a shipyard. The Ulsan site was still essentially a plan when the contract came through. But that order was the key that opened the Barclays loan and made the project real.

Livanos wasn’t some naïve early adopter. He was one of the most formidable shipowners of his era, known for taking calculated risks and for judging people as much as he judged balance sheets. In this case, he was betting on Chung’s character and Korea’s hunger more than on any proven capability.

The wager on both sides was enormous. Livanos was trusting a promise measured in hundreds of millions of dollars. Chung was staking Hyundai’s future on building something he had never built, in a place where nothing yet existed.

And that’s why this origin story matters. It set the template for what came next: outsized ambition, high tolerance for risk, and a willingness to execute on impossible timelines. Those traits would power Hyundai’s ascent—and, decades later, amplify the consequences when a big bet went the wrong way.

III. Building the Yard and the Ships Simultaneously (1972-1983)

The Ulsan Miracle: Twenty-Seven Months from Beach to Delivery

In March 1972, Hyundai broke ground on an empty stretch of beach in Ulsan—nothing but shoreline and ambition—and declared it would become the world’s largest shipyard.

Then came the truly audacious part: Hyundai began building the yard and the ships at the same time. While teams poured concrete and raised cranes, other teams started cutting steel for the two 260,000-DWT tankers Livanos had ordered. There was no “finish the factory, then start production” phase. The factory was the production.

Just 27 months later, in 1974, Hyundai held a ceremony that still feels like a plot twist: it named the two tankers and dedicated the shipyard in one moment. HD Hyundai Heavy Industries—founded by Chung Ju-yung on March 23, 1972—opened its shipbuilding era in June 1974 by completing the yard and delivering two VLCCs essentially in the same breath.

The logistics were brutal. Chung was running two giant projects in parallel, each one capable of ruining the other if it slipped. Work ran day and night. Problems that would normally take months to engineer away had to be solved in days—because there was no slack in the schedule and no forgiveness from the lenders.

And the early chaos was real. Because the dockyard was too small, one of the first tankers had to be built in two halves. When the pieces didn’t fit together properly, Hyundai didn’t get to pause and “do it right.” Instead, Chung had it welded anyway, set up a shipping business to use that vessel, and built another tanker that did fit for the foreign client. It’s a story that rarely shows up in polished company narratives, but it captures the underlying reality: this wasn’t a clean, linear march to greatness. It was improvisation under existential pressure.

When Hyundai delivered the Atlantic Baron to Livanos in June 1974, it landed like a thunderclap across the maritime world. South Korea—still a country that hadn’t built large ships before this decade—had delivered supertankers on time. It wasn’t just a corporate milestone. It was Korea announcing, loudly, that it had entered the ranks of serious industrial powers.

The Government-Chaebol Partnership: Korea Inc. Takes Shape

Hyundai didn’t pull off Ulsan alone. The company’s early rise was built on two forces moving in lockstep: Chung’s ability to convince partners and customers, and a South Korean government determined to push the country beyond light manufacturing and into heavy industry.

This state-chaebol partnership became a signature of Korea’s economic takeoff. The government provided guarantees for foreign loans and invested in industrial complexes. It helped with infrastructure, approvals, and the conditions needed to scale a workforce quickly. And it did this at a moment when shipbuilding in traditional strongholds—Europe and the United States—looked tired and uncompetitive. Seoul saw an opening in a capital-intensive industry and moved aggressively to seize it, keeping labor costs low and directing national resources toward building export champions.

But the support came with an implicit deal: these weren’t just corporate projects. They were national projects. For Hyundai Heavy Industries, every successful delivery burnished Korea’s reputation. Every delay or quality issue risked becoming a public embarrassment. The shipyard was a business, yes—but it was also a proving ground for the country’s industrial credibility.

The Race to Number One

Once Hyundai proved it could deliver, momentum took over. Within a decade of that first watershed delivery, the Hyundai shipyard surpassed 10 million deadweight tons in cumulative production—an extraordinary run for a company that, only years earlier, didn’t have a shipyard at all.

By 1983, Hyundai Heavy Industries had become the world’s largest shipbuilding company. In just over a decade, it had vaulted past established shipyards in Japan and Europe and turned Ulsan into a global reference point for scale and speed.

Hyundai moved quickly to deepen its capabilities. It secured orders even from Japanese competitors and signed technical cooperation deals with Kawasaki Heavy Industries in Japan and Scott Lithgow in the United Kingdom. Before a broader market collapse hit, the yards produced a wave of large tankers—evidence that the early success wasn’t a one-off stunt, but the start of a machine.

The formula, at least on paper, was clear: lower labor costs than many rivals, government backing that eased financing pressure, and aggressive pricing that brought in work even when margins were thin. In practice, it also required a punishing internal culture. Chung demanded relentless output. “Fiercely authoritarian,” he was known for striking managers and for his hostility toward unions—an approach that fueled pitched labor battles at Ulsan.

By today’s standards, parts of this era are hard to look at cleanly. Workers lived in dormitories, worked six-day weeks, and were expected to give the company not just their labor but their lives. Hyundai became more than an employer; it became an institution that shaped the rhythm of an entire city.

Still, the strategic impact was unmistakable. Hyundai’s entry into shipbuilding helped propel South Korea toward the top tier of global shipbuilding—first climbing behind Japan, and then setting the stage to go further.

IV. The Great Hyundai Breakup (1997-2002)

The Asian Financial Crisis Catalyst

By the mid-1990s, Hyundai had become less a company than a self-contained economy—autos, electronics, construction, shipbuilding, and dozens of other businesses stitched together under one name. By the time Chung stepped back in 1991, Hyundai represented an astonishing slice of the nation: about 16 percent of Korea’s GDP and 12 percent of its exports.

That scale looked like invincibility. It was also fragility in disguise.

When the Asian Financial Crisis hit in 1997, the weaknesses of the chaebol system snapped into view. Many conglomerates were highly leveraged, and their internal logic depended on profitable units quietly carrying weaker ones. As credit tightened and scrutiny intensified, the model that had powered Korea’s rise suddenly looked like a risk to the whole economy.

Hyundai didn’t just stumble—it had to be reorganized. In the wake of the 1997–1998 crisis, major units like Hyundai Motor and Hyundai Heavy Industries began operating more independently as the group was restructured. The era of sprawling cross-subsidies and one-family control over an ever-expanding empire was coming to an end. The new mandate was focus: simplify ownership, rein in debt, and concentrate on core businesses.

And inside Hyundai, one particular problem poured gasoline on the situation. The debts and turmoil at Hyundai Engineering & Construction accelerated the breakup—and ignited a family succession fight that would spill into public view.

The Brothers' War: Dynasty in Turmoil

What followed was not a tidy corporate reorganization. It was a dynasty breaking apart.

In the early 2000s, Chung Ju-yung’s sons fought over who would control which pieces of the empire. The most visible feud centered on the second son, Chung Mong-koo, and the fifth son, Chung Mong-hun. But it was the sixth son, Chung Mong-joon, who made a decisive move: he split away from the group, taking the heavy industries business arm with him.

The battles weren’t confined to backroom negotiations. They played out through boards, courts, and the press, with shifting alliances and bitter accusations. This wasn’t just about titles—it was about who would inherit the most strategically important assets in the country.

By 2002, the outcome for shipbuilding was clear. Hyundai Heavy Industries was spun off from Hyundai Group to form the Hyundai Heavy Industries Group. That same year, HHI expanded its footprint by acquiring Samho Heavy Industries from Halla Group, later renaming it Hyundai Samho Heavy Industries.

With that, the shipbuilding business entered a new phase. No longer tied to the broader Hyundai network—no longer cushioning other units or relying on them—heavy industry would stand on its own economics for the first time.

The Legacy of Chung Ju-yung

Chung Ju-yung didn’t live to see the final shape of the breakup. He died in March 2001 at the age of 85, leaving behind both a transformed nation and a family still fighting over the structure he built.

His accomplishments were undeniable. Under his leadership, Hyundai became the world’s largest shipbuilder. Hyundai Motor Group grew into Korea’s largest automaker and later a top global player.

But the legacy is complicated. To admirers, he was the architect of Korea’s industrial leap—from poverty to global competitiveness. To critics, he embodied the darker side of that growth: an autocratic management style, harsh labor relations, and deeply intertwined relationships with governments of the day.

For the shipbuilding business that would eventually sit under HD KSOE, the inheritance wasn’t just assets and yards. It was a way of operating: aggressive risk-taking, technological ambition, and relentless execution. Those traits had carried Hyundai to the top.

They were also about to be tested in a far less forgiving world.

V. The Golden Years and the Offshore Bet (2000s-2013)

Dominating Global Shipbuilding

As the newly independent Hyundai Heavy Industries Group entered the 2000s, it did so from the front of the pack. Shipbuilding wasn’t just another Korean export industry—it was a pillar of the country’s economy and its global standing. And in the early years of the decade, South Korea’s yards were producing roughly half of the world’s ships.

At the center of that surge sat the “Big Three”: Hyundai, Daewoo, and Samsung. Together, they built a reputation that was hard to match—technical capability, reliable delivery, and pricing that made owners and operators around the world comfortable placing enormous orders with Korean yards.

Hyundai kept widening what it could build. Not just the workhorse categories like VLCCs and containerships, but also the more specialized end of the market: LNG carriers, drillships, and offshore platforms. Each new class of vessel meant tougher engineering, higher contract values, and—at least in good years—better economics. The ambition was clear: don’t merely assemble ships. Control the hardest parts of the build, end to end, from the hull and machinery to the specialized systems that make high-value vessels so difficult to execute.

The Offshore Expansion: Chasing Higher Margins

Then the offshore boom arrived, and it looked like the next level.

Through the 2000s, as oil prices climbed, exploration and production companies poured money into deepwater fields and complex developments. They needed floating production platforms, drillships, and purpose-built offshore structures—projects so large and intricate that only a handful of yards in the world could credibly take them on. This was exactly the kind of work Korean shipbuilders had trained themselves to win.

Hyundai Heavy Industries leaned in. The pitch, internally and externally, was compelling: these contracts were massive, stretched over multiple years, and promised richer margins than standard commercial shipbuilding. The yard wasn’t just selling steel and labor anymore. It was selling engineering certainty—turnkey delivery of floating industrial infrastructure.

But offshore came with a different kind of risk profile. A containership is industrial repetition: proven designs, standardized production steps, and problems that can be modeled because the industry has solved them before. A first-of-its-kind floating platform designed for harsh ocean conditions is closer to a bespoke mega-project. The technical unknowns are bigger, the timelines are longer, and the cost of being wrong is far higher. And as the industry chased those bigger paydays, fixed-price, turnkey contracts became the norm—locking in revenue on paper while quietly shifting the downside onto the builder.

The Seeds of Crisis

In hindsight, the danger was baked in. Fixed-price deals on unprecedented offshore projects created a trap: if engineering complexity ballooned, or schedules slipped, the contract didn’t flex with reality. The financial model depended on a comforting assumption—that oil would stay high, and demand would stay hot—so each new offshore win looked like a smart extension of Korea’s dominance.

And it wasn’t just Hyundai making that leap. The entire Korean shipbuilding industry was reaching for offshore at the same time.

Which meant that when the cycle finally turned, it wouldn’t just sting. It would hit all of them together.

VI. The Crisis: Near-Death Experience (2014-2017)

The Perfect Storm

Then the cycle turned—and it turned hard.

In mid-2014, oil prices began collapsing, eventually falling from above $100 a barrel to below $30. For the Korean shipbuilders that had just bet big on offshore mega-projects, this wasn’t a normal downturn. It was the rug being pulled out from under the entire strategy.

Offshore plants—the very projects that were supposed to deliver higher margins and longer-term stability—became the source of the industry’s deepest wounds. The work proved more complex and more expensive than planned, and Korean yards were still building true expertise in designing and executing these offshore projects. At the same time, the economics for customers disintegrated. As oil prices plunged, clients delayed, postponed, or canceled. Losses snowballed and started showing up clearly in earnings and balance sheets in 2015 and 2016.

And while offshore was imploding, traditional ship orders dried up too. In early 2016, for the first time in history, Korean shipbuilders failed to win a single order in April. The broader collapse showed up in the data: new orders for Korean shipbuilders plunged in 2016, down 82% by estimated freight volume.

The Staggering Losses

The industry’s financial picture became almost surreal. The Big Three—Daewoo Shipbuilding & Marine Engineering, Hyundai Heavy Industries, and Samsung Heavy Industries—carried $42.1 billion in loans between them, and they ended 2015 with combined losses of more than $6 billion.

In a country where shipbuilding represented about 6.5% of GDP, this wasn’t just an industry correction. It was a national alarm bell.

The Human Cost

When orders vanish in shipbuilding, the pain is immediate and intensely local—because shipyards don’t just employ people, they anchor whole cities.

The Big Three began layoffs and pushed voluntary resignations. Hyundai Heavy Industries started restructuring in 2015 by cutting office staff, with plans to reduce factory workers as well. The mood turned so dark that HHI was even nicknamed “the death factory”—a phrase that captured both the danger of yard work and the despair of losing a livelihood in a collapsing industry.

Nationally, unemployment claims rose 1.3% year over year in the first quarter. But the real story was what happened in places built around the yards. In Ulsan, unemployment benefit claims jumped 18%. Payrolls across the shipbuilding industry were slashed as companies tried to survive the order cliff, with deep cuts in 2016 and even more a year later.

These weren’t abstract percentages. They were families and neighborhoods built around a promise—work hard, stay loyal, and the yard will take care of you—watching that promise get rewritten in real time.

The Restructuring

By 2016, survival meant breaking apart what had been built up over decades.

Hyundai Heavy Industries split into four companies as part of a creditor-backed restructuring plan to cope with the losses. Across the industry, the major shipbuilders submitted turnaround measures to creditors and the government: layoffs, asset and subsidiary sales, and a push for productivity gains.

The logic was brutal but simple. Cut to the core. HHI kept shipbuilding, offshore, and industrial plants, while spinning off businesses like electric systems, construction equipment, and robotics. It was less a strategy shift than a triage decision—stop the bleeding, protect the heart.

The "Tears of Malmö" Fear

In Korea, there was a powerful, physical symbol of what failure could look like.

In 2002, a gigantic crane from Malmö—once the pride of Sweden’s Kockums shipyard—was sold to Hyundai Heavy Industries for $1 and shipped to Ulsan. Residents reportedly wept as it was dismantled and towed away, giving rise to its nickname: “Tears of Malmö.” It embodied the story of a shipbuilding nation that lost its edge, watched its yards close, and saw its industrial landmarks sold off for scraps.

Now that crane stood in Ulsan—less as a trophy than as a warning. During the 2015–2017 crisis, Korean media invoked the “Tears of Malmö” constantly, asking the question nobody wanted to say out loud: could Ulsan be next?

The government was determined not to let that happen. Korea poured enormous sums into supporting the ailing shipbuilders, trying to avoid the fate of Europe’s shipbuilding industry in the 1980s, where rescue efforts failed to bring the sector back. The goal wasn’t just to save companies. It was to prevent a permanent collapse of capability—skills, facilities, and an industrial base that, once lost, is almost impossible to rebuild.

VII. The KSOE Transformation and The Failed DSME Mega-Merger (2019-2022)

Creating the Holding Company Structure

The crisis didn’t just force cost cuts. It forced a rethink of what Hyundai’s shipbuilding empire actually was.

In 2019, the company rebuilt its corporate architecture to separate the role of “operator” from “owner.” The shipbuilding business was spun into a new operating entity, while Korea Shipbuilding & Offshore Engineering, or KSOE, was positioned as the intermediate holding company sitting above the yards. The point was clarity and control: KSOE would coordinate strategy, capital, and big technology bets across the group, while the shipyards focused on building ships.

It also set the table for something much bigger: a proposed mega-merger with its fiercest domestic rival, Daewoo Shipbuilding & Marine Engineering.

The DSME Acquisition: A Mega-Deal for Market Dominance

The deal dated back to 2019. Hyundai Heavy Industries, staring at intensifying competition from China, sought to reinforce its position as the world’s leading shipbuilder by taking over DSME in a transaction valued around $1.8 billion.

The plan hinged on acquiring a 55.7% stake in DSME from the state-owned Korea Development Bank. Strategically, the logic was hard to miss. Hyundai and DSME weren’t just major shipbuilders; they were both among the top builders of large LNG carriers—one of the highest-value, most technically demanding categories in the industry.

Put them together, and you didn’t just get scale. You got gravitational pull in a market that was already concentrated. Regulators would later argue that the combined company’s share in large LNG carriers would be at least 60%, a level that, on its face, signaled a dominant position.

The EU Block: Energy Security Trumps Consolidation

That dominance became the deal’s undoing.

In January 2022, the European Commission prohibited the acquisition under the EU Merger Regulation. The decision landed like a shock in Korea: the merger that was supposed to cement national shipbuilding supremacy was now being framed as a threat to global competition—specifically in LNG carriers.

Executive Vice-President Margrethe Vestager, who oversaw competition policy, made the Commission’s view explicit. Large LNG carriers, she said, are essential to the liquefied natural gas supply chain, and LNG helps diversify Europe’s energy sources—meaning competition in LNG shipping directly touches energy security.

Europe also wasn’t a bystander in this market. Over the prior five years, large LNG carrier orders represented a market worth up to €40 billion, with almost half of those orders coming from European customers. To the EU, a combined Hyundai–Daewoo would reduce options and concentrate pricing power in a way it wasn’t willing to accept.

Regulators pushed a remedy: sell part of either Hyundai’s or Daewoo’s LNG carrier business to bring the combined market share below 50%. Hyundai rejected the demand. Korea Development Bank chairman Lee Dong-gull argued that Europe—home to many of the world’s biggest shipowners—was acting out of self-interest. But the Commission didn’t budge, and without EU approval, the merger couldn’t survive.

The Aftermath: DSME Becomes Hanwha Ocean

KSOE had secured approvals from China, Kazakhstan, and Singapore. It didn’t matter. The EU veto effectively ended the transaction, and the DSME mega-merger collapsed.

KSOE, however, remained what the 2019 reorganization intended it to be: the intermediate holding company overseeing Hyundai Heavy Industries, Hyundai Mipo Dockyard, and Hyundai Samho Heavy Industries.

DSME’s future took a different turn—one that created a newly energized competitor. In December 2022, Hanwha Group announced it would acquire a controlling 49.3% stake in DSME for 2 trillion won (about $1.5 billion). The acquisition was formally approved, and the rebranded company became Hanwha Ocean.

Hanwha Ocean inherited DSME’s formidable physical footprint. Its Geoje shipyard is equipped with top-tier facilities, including a 1-million-ton dock and a 900-ton Goliath crane, and it has positioned itself as a leader in eco-friendly, high-efficiency LNG carriers.

In a twist, the failed merger may have strengthened Korea’s overall competitive posture. Instead of one consolidated champion, South Korea emerged with three heavyweight shipbuilders—HD KSOE, Hanwha Ocean, and Samsung Heavy Industries—each large enough to win globally, and each forced to keep sharpening its edge.

VIII. The LNG Renaissance and Modern Era (2020-Present)

The LNG Carrier Pivot: From Crisis to Dominance

The comeback was built on one category of ship above all others: LNG carriers.

After the offshore shock nearly broke the industry, South Korea’s leading yards doubled down on what they could do better than almost anyone on Earth: high-value, high-complexity vessels where execution matters as much as price. LNG carriers sit at the top of that list. They demand sophisticated cargo containment systems, specialized propulsion, and an unforgiving level of precision on the yard floor. Korean shipbuilders had spent decades stacking up know-how here—and it wasn’t something competitors could copy overnight.

The result was a decisive swing in orders. This year, Korean shipbuilders captured about 70% of global LNG carrier orders. That wave of demand is a big part of why the country’s major shipbuilders were able to return to profitability at the same time—something that hadn’t happened in 13 years.

Record-Breaking Performance

By late 2024, the recovery started showing up in black and white.

HD Korea Shipbuilding & Offshore Engineering, Samsung Heavy Industries, and Hanwha Ocean each reported third-quarter 2024 results that reflected a healthier market and better mix. HD KSOE said on Oct. 31 that its third-quarter operating profit rose to 398.4 billion won, up 477% year-on-year.

Orders came in just as strongly. HD KSOE said it had booked 169 new vessels worth $18.84 billion for the year, well ahead of its annual order target of $13.5 billion.

For the full year, HD Korea Shipbuilding & Offshore Engineering reported operating profit of 1.4 trillion won in 2024, up 408% from 2023, on sales of 25.5 trillion won, up 19.9% year-on-year. Taken together, 2024 marked a historic turnaround for the sector, with Korea’s largest yards expected to post full-year operating profits in the same year for the first time in 13 years.

And the momentum carried into 2025. In the second quarter of 2025, HD KSOE said consolidated operating revenue reached 7.4284 trillion won, up 12.3% year-on-year, while operating profit climbed to 953.6 billion won, up 153.3%.

The HD Hyundai Rebrand and Future Vision

The transformation wasn’t only about earnings. It was also about identity.

HD Hyundai—born out of Hyundai Heavy Industries Group—has continued to broaden itself into a global heavy industries conglomerate, extending beyond shipbuilding into refining, petrochemicals, construction machinery, electrical and electronic systems, solar energy, and robotics. But in this new upswing, shipbuilding is still the engine, and the strongest tailwind has been the delivery of high-value, eco-friendly vessels—especially LNG carriers.

Strategically, the company has been pushing further into automation and “green” technology themes. The bet is that the next era of shipbuilding leadership won’t be decided by who can simply produce the most tonnage. It will be decided by who can reliably deliver the hardest ships in the world, at scale, with the systems, quality, and fuel efficiency that regulators and customers increasingly demand.

The U.S. Navy Opportunity

Another potential growth lane has opened—one with a very different customer.

HD Hyundai Heavy Industries secured the right to bid for U.S. Navy maintenance, repair and operations (MRO) projects, becoming the first South Korean shipbuilder to qualify. Under the agreement, HD HHI gained qualification to submit bids for MRO work for U.S. Navy warships as well as support ships of the U.S. Military Sealift Command.

Not long after, HD Hyundai Heavy Industries announced it had secured its first-ever MRO contract for a U.S. Navy vessel—an early milestone in South Korea’s push to deepen defense and shipbuilding cooperation with Washington.

For Korean shipbuilders, the appeal is obvious. MRO can be a lucrative, recurring business, and the U.S. military is estimated to spend more than $14 billion annually on MRO contracts. If HD Hyundai can translate its yard discipline from newbuilds into maintenance work for the world’s most demanding naval customer, it adds a new pillar of opportunity—one less exposed to the brutal cycles of commercial ship orders.

IX. Competitive Positioning: The China Challenge

The Shifting Balance of Power

If HD KSOE’s comeback story has a new antagonist, it’s China—and not in the vague, “rising competitor” sense. In shipbuilding, China has already changed the map.

By 2023, Chinese shipbuilders had captured nearly 65% of global market share, up from less than 10% in 2000. Over that same stretch, South Korea and Japan—once the unquestioned center of gravity—saw their combined share fall from 78% to 31%. The shift wasn’t gradual. It was structural.

You can see it in the most recent order flow, too. South Korean shipbuilders won orders totaling 10.98 million CGT in 2024, roughly 17% of the global market.

And the backlog picture is just as telling. China’s yards held an orderbook of 91.51 million CGT—about 58% of vessels on order by tonnage. South Korea sat at 24%, with just over 37 million CGT.

In a business where today’s orderbook becomes tomorrow’s factory utilization—and where utilization becomes pricing power—those aren’t just statistics. They’re leverage.

Korea's Strategic Response: High-Value Specialization

But “market share” in shipbuilding can be a trap metric. Not all tonnage is created equal.

China has won on volume. Korea has tried to win on difficulty.

Even as China expanded across mainstream categories, South Korea kept its edge in the ships that are hardest to build and easiest to mess up—especially LNG carriers. That’s where Korean yards’ long-built reputation for quality and execution still matters, and where owners are less willing to gamble on a lower-cost bid if it risks delays, performance issues, or costly rework.

Order cycles also show how quickly the balance can swing when the mix changes. After a weak December—when South Korea booked only a small slice of new orders while Chinese yards took the overwhelming majority—the industry snapped back in January 2025 and retook the lead. It was the first time in months Korea captured the largest share of new orders, and it underscored the logic of the strategy: don’t chase everything. Chase what pays.

So far in 2025, that approach has shown up in the numbers. Korea’s market share has doubled versus 2024 to 25.9%, while China’s has fallen from 74.5% to 58.8%.

Structural Advantages and Vulnerabilities

Korea’s most durable advantage is the one that’s hardest to copy: accumulated know-how. Building LNG carriers, drillships, and the most sophisticated containerships isn’t just about welding steel. It’s a systems game—engineering discipline, specialized suppliers, skilled trades, and institutional muscle memory built over decades. That ecosystem creates real barriers to entry.

It also explains why the South Korean government has encouraged coordination among the country’s top three builders—HD Hyundai Heavy Industries, Samsung Heavy Industries, and Hanwha Ocean—especially on the technologies likely to shape the next generation of ship orders. That includes green tech like ammonia-powered ships, hydrogen fuel cells, and carbon capture systems, as well as autonomous shipping efforts that use AI and IoT to make “smart ships” more than a brochure phrase.

Still, the vulnerabilities are just as concrete. Chinese yards benefit from lower labor costs, cheaper steel, and government support that lets them price aggressively. By some estimates, Chinese shipbuilding prices run about 10% to 15% below South Korean pricing.

Which is why Korea’s strategic box is so clear. It can’t win a race to the bottom on cost. It has to keep winning the race to the top on capability—and do it fast enough that “high value” doesn’t become a temporary moat.

X. Bull Case, Bear Case, and Investment Framework

The Bull Case

The optimistic thesis for HD KSOE is basically a bet that the comeback isn’t a one-cycle fluke. It’s a bet that the company has re-centered itself on the hardest, most defensible work in global shipbuilding—and that the macro winds are finally blowing in its favor.

Technological Moat in LNG: Korean yards have held roughly 70% of the global LNG carrier market, and that advantage isn’t just about price. LNG carriers are among the most punishing commercial ships to build: membrane containment systems, specialized propulsion, and an unforgiving tolerance for error. That complexity creates barriers that most yards can’t clear quickly, even with cheap labor and scale.

Energy Transition Tailwinds: Decarbonization is pushing the industry toward new vessel types and new fuels, and HD KSOE has been positioning for that shift. Ammonia carriers are a cornerstone of the strategy. The company booked eight ammonia carrier orders in 2025 and a 2024 order worth $245 million, aligning with the International Energy Agency’s projection that ammonia-powered ships could make up 46% of the global fleet by 2050.

U.S. Market Access: The opening into U.S. Navy MRO is small in absolute terms today, but strategically big. Combined with the possibility of tariffs on Chinese shipbuilding, it could create a new lane of demand—less tied to commercial shipping cycles. This first MRO win for HD Hyundai also sits alongside the Korean government’s proposed $150 billion South Korea–U.S. shipbuilding cooperation initiative, dubbed “Make American Shipbuilding Great Again.”

Financial Recovery: After years defined by losses and restructuring, the company’s return to profitability signals real operational improvement. Management has pointed to an $18 billion order target, and the improvement in profitability is reflected in the company’s stated EBIT margin expansion to 10.9% in 2025, up from 5.6% in 2024.

Multi-Year Order Backlog: In a cyclical industry, visibility is rare—and valuable. South Korean industry insiders have said shipyards have enough work on hand for roughly the next three years based on current orders. That backlog doesn’t eliminate cycle risk, but it can smooth the ride.

The Bear Case

The pessimistic thesis is just as clear: shipbuilding has always been a knife fight, and the strongest opponent is getting stronger.

Chinese Competition: China’s cost and capacity advantages are already reshaping the market, and the worry is that “high value” won’t stay protected forever. China has been pushing up the complexity curve. In 2024, Chinese shipyards surpassed South Korea in LPG carrier orders, winning 62 orders compared to South Korea’s 59—a signal that China isn’t content to remain the low-end factory floor.

Cyclicality: No matter how strong the backlog looks today, shipbuilding can turn brutally fast. The 2015–2017 period proved that a downturn can go from “softening demand” to “existential crisis” in a few quarters when capital spending freezes and cancellations start to stack.

Concentration Risk: The LNG focus has been a lifeline—but it also narrows the company’s exposure. If LNG demand disappoints, or if Chinese yards close the technology gap faster than expected, the current profit engine could weaken right when fixed costs remain high.

Labor Challenges: Korea’s shipyards have faced worsening manpower shortages. Many engineers laid off during the downturn found work at land plants or overseas shipbuilders with better working conditions, and a meaningful portion have been reluctant to return—creating a bottleneck that’s hard to solve quickly.

Geopolitical Risks: Trade policy shifts, regional conflicts, sanctions, and supply-chain disruptions can all reroute orders or delay deliveries. In this industry, politics doesn’t sit outside the business—it shows up in the orderbook.

Applying Porter's Five Forces

Threat of New Entrants: LOW-MODERATE. Building complex vessels demands massive capital, hard-won expertise, and a mature supplier ecosystem. But China has shown that, with enough state support and persistence, even “high barrier” markets can be entered.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers: MODERATE. Shipbuilding depends on specialized inputs—engines, containment systems, steel. Long-standing supplier relationships help, and the ability to integrate parts of the stack provides leverage, but constraints and bottlenecks can still bite.

Bargaining Power of Buyers: MODERATE-HIGH. The buyers—major shipping companies and energy players—are sophisticated and global. They can run competitive tenders. But for top-tier LNG carriers and other specialized builds, the pool of qualified yards is limited, which supports pricing power.

Threat of Substitutes: LOW. If you need to move bulk cargo across oceans, you need ships. Pipelines, rail, trucking, and air freight solve different problems.

Industry Rivalry: HIGH. Competition is intense—especially with China’s scale and pricing, and with strong domestic rivals in Korea. Segment focus can reduce head-to-head overlap at times, but the industry remains crowded where the money is.

Applying Hamilton Helmer's 7 Powers

Scale Economies: Partially present. Ulsan provides scale advantages, but Chinese yards have achieved comparable or greater scale in many segments.

Network Effects: Minimal. Traditional shipbuilding doesn’t have classic network effects, though supplier ecosystems can create switching friction.

Counter-Positioning: Strong. Korea’s concentration on high-complexity ships is a strategic position that’s difficult to match if you’re optimized for low-cost volume—at least without reshaping your entire model.

Switching Costs: Moderate. Owners build trust with yards over time, and complex technical specifications can create practical lock-in, but repeat business isn’t guaranteed.

Branding: Moderate. Korean builders have a reputation for quality and reliable delivery that can earn premium pricing, especially on complex ships where failure is expensive.

Cornered Resource: Yes—skilled workforce. Decades of accumulated human capital in complex vessel construction remains one of Korea’s hardest-to-copy advantages, even as shortages emerge.

Process Power: Strong. The yards’ experience building LNG carriers and other complex vessels has translated into execution capability—process discipline that shows up in delivery reliability and, increasingly, stronger margins.

XI. Key Metrics and Investment Considerations

Critical KPIs to Monitor

If you’re tracking HD KSOE as an investment, you don’t need to memorize every quarterly line item. You need to watch the few signals that tell you whether the story is strengthening—or quietly breaking.

-

LNG carrier order market share: This is the heartbeat of the competitive thesis. Korean yards have been taking roughly 70% of global LNG carrier orders, and for HD KSOE, this category is where reputation, process discipline, and engineering depth still translate into wins. A sustained drop below 60% would be a real warning sign that Chinese yards are closing the gap on the hardest work. Holding share, or expanding it, would reinforce the idea that Korea’s advantage here is more than historical inertia.

-

EBIT margin expansion: Shipbuilding can generate enormous revenue while destroying value if pricing or execution slips. That’s why margin trend matters more than top-line growth. HD KSOE’s margins have moved from the negative territory of 2016–2017 into the single digits—and now toward double digits. The company has guided to an EBIT margin of 10.9% in 2025, up from 5.6% in 2024, reflecting better mix and better pricing on high-spec vessels. The question is whether margins can stay above 10% through the inevitable cycle shifts.

-

Order backlog duration: In a business built on multi-year projects, backlog is your visibility. A roughly three-year backlog is unusually strong for shipbuilding. But duration alone isn’t the whole story. The mix matters: a backlog full of high-value LNG carriers and specialized vessels is fundamentally different from a backlog padded with lower-margin commodity tonnage. Watching how that backlog evolves is one of the cleanest ways to gauge future revenue quality.

Regulatory and Accounting Considerations

There’s another layer investors can’t ignore: how shipbuilders report their results.

The industry relies on percentage-of-completion accounting, which means revenue and profit are recognized as projects progress—not only when a ship is delivered. That creates room for judgment, because management has to estimate total project costs years in advance. When those estimates are wrong, the correction can be sudden and ugly. The 2015–2016 downturn wasn’t just operational; it also exposed accounting problems across the industry, including scandals at DSME tied to delayed loss recognition.

Two practical implications follow. First, when costs run over on long-term, fixed-price contracts, the financial impact can arrive later than the operational reality—until it hits all at once. Second, currency matters. Revenues are typically dollar-denominated, while a meaningful portion of costs are won-denominated, so the won/dollar exchange rate can meaningfully swing reported performance even when yard execution is steady.

The Investment Takeaway

HD Korea Shipbuilding & Offshore Engineering is a classic case of a cyclical industrial leader trying to turn a hard-earned technical edge into durable returns.

The company’s arc—from an empty beach in 1972, to global dominance, to near-death in the mid-2010s, to a modern LNG-led resurgence—proves two things at the same time: the institution is resilient, and the industry is unforgiving.

Today’s setup offers exposure to LNG demand, alternative-fuel vessel development, and an early foothold in U.S. defense-related ship work. Against that are the structural realities: China’s rise, the relentless pull of shipbuilding cycles, and the fact that even leaders can get trapped by fixed-price complexity.

For a long-term fundamental investor, the central question isn’t whether HD KSOE can win the next batch of orders. It’s whether the moat built over decades—process know-how, supplier relationships, and deep human capital in complex vessels—can keep producing premium economics as Chinese competitors climb the technology ladder.

Because in shipbuilding, history has a dark sense of humor. The same industry that once shipped a Swedish crane to Ulsan for a dollar can eventually do the reverse. Whether HD KSOE becomes another Malmö—or writes the next fifty years of this story—hinges on those few metrics, and on whether execution stays ahead of the curve.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music