MTR Corporation: The World's Most Profitable Railway and the Genius of Rail + Property

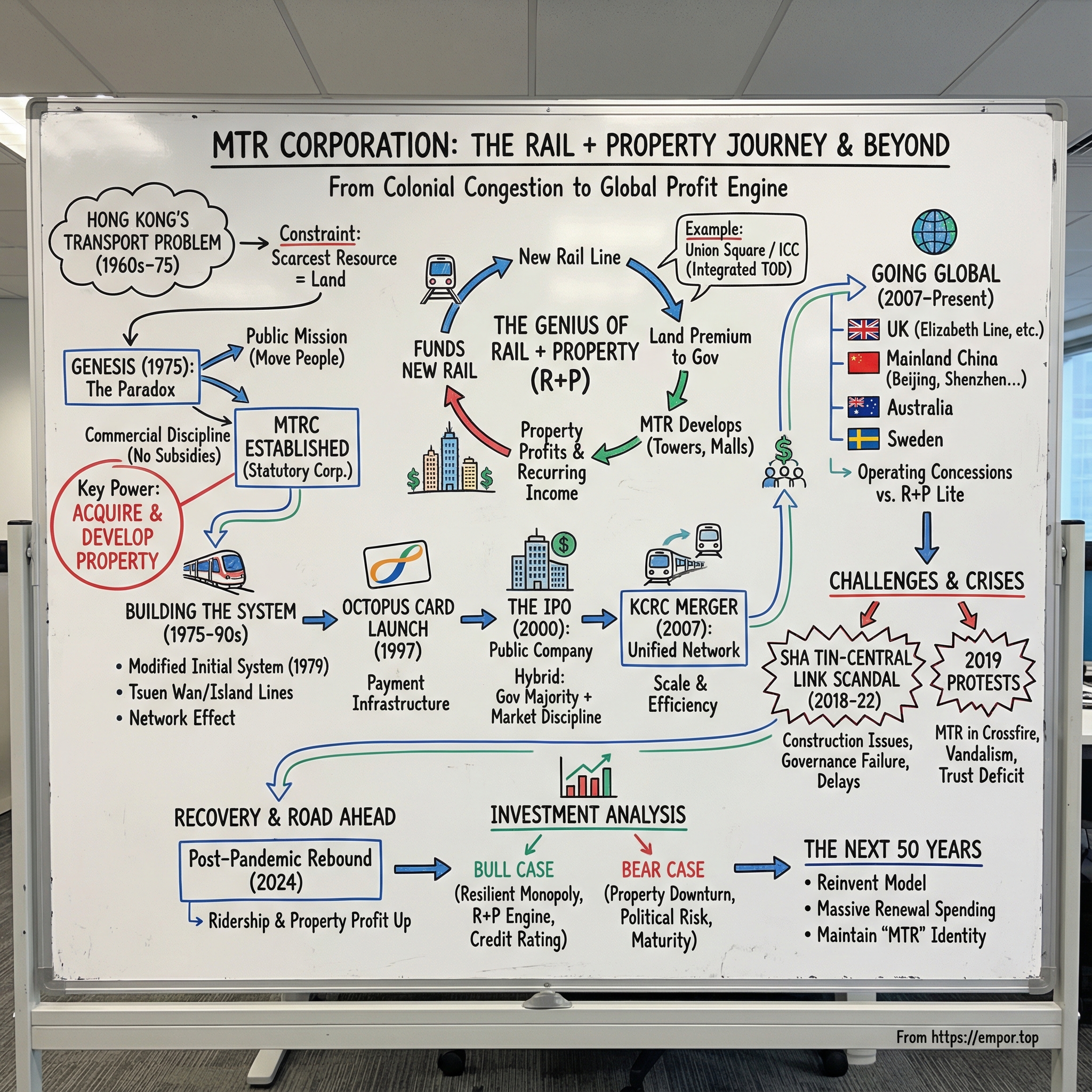

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

Picture this paradox: a metro system that actually makes money. Not a little money—a lot. In 2024, according to internal business documents, MTR posted net profit of HK$15.8 billion (about US$2 billion). Revenue rose to HK$60.01 billion, up from HK$56.98 billion the year before. Earnings more than doubled to HK$15.77 billion.

That’s not a rounding error. Around the world, big-city transit usually runs on subsidies and political triage. But Hong Kong’s MTR sits in a category of its own: a public transport operator that runs with commercial discipline, delivers elite service, and still produces real profits. MTR has remained one of the few profitable public transport systems in the world.

So what’s the trick? How did a government-built transit authority turn into a global rail operator—running trains in places like London, Stockholm, Sydney, and Beijing—while keeping the home system humming?

The answer is a business model that rewired the economics of public transportation: Rail plus Property. Instead of treating rail as a permanent loss leader, MTR found a way to capture the value its trains create—then recycle that value back into building more rail.

At its core, MTR Corporation Limited is a majority government-owned public transport operator and property developer in Hong Kong. It runs the Mass Transit Railway, the city’s dominant public transport network. It’s also a public company—listed in Hong Kong and included in the Hang Seng Index—which means it lives in two worlds at once: public mission and shareholder expectations.

And operationally, it’s a machine. Under Hong Kong’s rail-led transport policy, the MTR is the default way the city moves: over five and a half million trips on an average weekday, with 99.9% punctuality. As of 2018, it held a 49.3% share of the franchised public transport market—nearly half the city’s formal transit usage.

This is the story we’re going to tell: from colonial-era congestion and a city boxed in by geography, to a once-impossible mandate—build world-class rapid transit without public subsidies. From there: the breakthrough of Rail plus Property, the leap into the public markets, the creation of a unified rail network, and then the hard parts—scandal, social upheaval, and the moments when MTR’s reputation and governance were tested in public.

If you want a masterclass in how incentives shape infrastructure—and how a transit system can be engineered to pay for itself—this is it.

II. Hong Kong's Transport Problem & The Genesis (1960s–1975)

To understand MTR, you first have to understand Hong Kong itself: a city squeezed onto islands and a narrow strip of mainland, where mountains drop straight into the harbor and usable land is always the scarcest resource. By the 1960s, Hong Kong was rapidly industrializing, its population was surging, and the street-level transport that had always held the city together—buses, trams, ferries—was starting to buckle.

The question facing the colonial government was straightforward and brutal: how do you move millions of people every day across steep terrain, through a major harbor, and into a dense urban core that can’t simply be widened? Feasibility studies were commissioned. Plans were debated. But by the early 1970s, the conclusion was hard to escape: if Hong Kong was going to keep functioning, it needed rapid transit, and it needed it underground.

And then came the twist that makes Hong Kong’s rail story different from almost every other great metro buildout of the 20th century.

Most cities treated metros as essential public services that would, inevitably, require ongoing subsidies. The construction costs were massive. The operating costs were real. And while the social payoff was obvious, the financial payoff rarely was. London, New York, Paris—these systems became civic necessities, not commercial enterprises.

Hong Kong decided to try something else.

In 1975, the government established the Mass Transit Railway Corporation (MTRC) as a statutory corporation, wholly owned by the Hong Kong Government. Its mission sounded like the usual infrastructure boilerplate—build and operate an urban railway system—but it came with a defining qualifier: it would do so under prudent commercial principles.

That phrase wasn’t window dressing. It was the founding constraint. MTRC was expected to be financially viable and to serve the government’s transport policy without direct public subsidies. From day one, it had to think like a business while behaving like a public utility.

Sir Norman Thompson, the first chairman, led the corporation through its formative years from 1975 to 1983, presiding over the early push to get Hong Kong’s first lines out of the ground. Under his watch, the Modified Initial System opened in 1979—two months ahead of schedule and under budget—an early signal of the operating discipline that would become part of MTR’s identity.

But the most consequential decision of all wasn’t a construction milestone. It was buried in the corporation’s powers. The founding ordinance allowed MTRC to acquire, hold, and dispose of property—movable and immovable—and to improve, develop, or modify it as the corporation saw fit.

In most places, that would have been a footnote. In Hong Kong, it became the master key.

Because it meant the government wasn’t just creating a railway operator. It was creating an organization that could participate in the city’s most valuable engine: real estate. MTRC could act as developer and site manager, not merely as a transport authority that collected fares and sent the bills elsewhere.

Later chairmen carried this logic forward. Sir Wilfrid Newton, who served from 1983 to 1989, continued expanding the network while reinforcing the idea that property development wasn’t a side hustle—it was a mechanism for long-term financial sustainability.

By the time the first trains were running, the blueprint was already in place: build rail where the city needs it, and capture the value that rail creates. The Rail plus Property model hadn’t become famous yet. But its DNA was already written into MTR’s founding.

III. Building the System: From First Line to Network (1975–1990s)

Construction began on November 11, 1975. What followed was an early preview of what would become MTR’s signature: unusually sharp execution for a piece of urban infrastructure this complex.

On October 1, 1979, the Modified Initial System opened—Hong Kong’s first operational slice of underground rapid transit. It ran 10.4 kilometers from Shek Kip Mei to Kwun Tong with nine stations, effectively forming the first segment of what would become the Kwun Tong Line. The demand was immediate. More than 200,000 passengers rode on day one, even as the system dealt with early hiccups like signal failures. For a city where buses and ferries were already straining under 1970s population growth, this was less “new option” and more “new backbone.”

And MTR didn’t linger in pilot mode.

On December 16, 1979, service extended to Tsim Sha Tsui. Then, on February 12, 1980, the full 15.6-kilometer Modified Initial System went live, including the harbor-crossing tunnel under Victoria Harbour and a connection to Admiralty station. Three more stations came online, and for the first time, Hong Kong had cross-harbor connectivity by rail—an engineering achievement with immediate, everyday impact.

Even in those early years, the arc was clear: once Hong Kong got a taste of reliable rapid transit, it wanted more of it.

The system began with just 15.8 kilometers of track and 11 stations. By 1982, it had expanded to 28 kilometers. Usage didn’t merely grow—it exploded. Annual passenger journeys rose from 5 million in the first year to 1.5 billion by 1989.

That’s the kind of growth that doesn’t just reflect a bigger city. It reflects a city rewiring itself around the new network—where people live, where they work, and how they move between the two. The MTR wasn’t just keeping up with Hong Kong. It was reshaping it.

Through the 1980s and into the early 1990s, expansion accelerated with new lines, including the Tsuen Wan Line and the Island Line. The result was a network that stitched together major districts and made fast, predictable travel a default. Each extension required tunneling through challenging ground, threading stations into dense high-rise neighborhoods, and integrating with the city’s layered, vertical streetscape. And again and again, MTR delivered with a level of timeliness and budget discipline that stood out globally.

Then the 1997 handover arrived—and with it, a cloud of uncertainty. Hong Kong was shifting from British to Chinese sovereignty. Would the rules of the game change? Would property values wobble, undermining the economics behind rail expansion? Would MTR’s commercial mandate survive in a new political era?

In the middle of that uncertainty, MTR helped launch something that made the system feel even more inevitable: Octopus.

The Octopus card is a reusable contactless stored-value smart card for electronic payments across Hong Kong. It launched in September 1997 as a fare card for public transport, but quickly expanded into everyday life—retail payments, dining, access control, and even functions like recording school attendance and permitting building access.

Adoption was astonishingly broad. Octopus is used by 98 percent of Hong Kong residents aged 15 to 64. The system processes more than 15 million transactions a day, worth over HK$220 million. Internationally, it became a reference point for what contactless payments could look like at city scale, winning the Chairman’s Award at the World Information Technology and Services Alliance’s 2006 Global IT Excellence Awards for, among other things, being the world’s leading complex automatic fare collection and contactless smart card payment system.

What’s easy to forget now is how early this was. In 1993, MTR announced it would move to contactless smart cards. In 1994, it partnered with four other major transit companies to form a joint venture—then called Creative Star Limited—to build the system. After three years of trials, Octopus launched on September 1, 1997, and three million cards were issued in the first three months.

The timing mattered. A major citywide technology rollout, landing right as sovereignty changed hands, sent a message: daily life would keep moving. And MTR wasn’t just operating trains—it was building infrastructure for how Hong Kong transacted.

As the 1990s drew to a close, MTR geared up for its next showcase project: the Airport Express to Hong Kong’s new international airport at Chek Lap Kok. This wasn’t just another metro extension. It was designed as a premium link between the financial core and one of the world’s most modern airports, complete with in-town check-in—so travelers could drop luggage at Kowloon Station and ride to the airport unencumbered.

By now, the pattern had become unmistakable. MTR could build. MTR could operate. And increasingly, MTR could innovate in the layers around the railway.

The groundwork was laid for the company’s most ambitious moves yet.

IV. The Genius of Rail + Property: MTR's Secret Weapon

This is the conceptual heart of the story: the business model innovation that makes MTR genuinely different from almost every other metro on Earth. If you want to understand how MTR can run world-class service and still produce profits while most transit systems live on subsidies, you have to understand Rail plus Property—R+P.

It starts with a simple, almost unfair observation: building a rail line doesn’t just move people. It changes what land is worth.

For new lines, the Hong Kong government grants MTR development rights at and around stations or depots along the route. Then comes the crucial detail: to convert those rights into land, MTR pays the government a land premium based on the land’s market value without the railway—what that site would be worth if no station were coming.

That’s the unlock.

Before a station exists, a site has one value. After a station opens—after it becomes a place where thousands of people can arrive and leave every hour—that same site becomes vastly more valuable. In most cities, that “value uplift” flows to whoever happened to own nearby property. The public pays for the infrastructure, private landowners get the windfall, and the transit agency still has to beg for operating money.

MTR captures that uplift instead. That’s land value capture, but built into the system from the beginning.

Once the development rights are in hand, MTR builds the railway and partners with private developers to build the towers, malls, offices, and housing above and beside the stations. Developers are selected through a competitive tender process. And MTR doesn’t just collect a fee—it takes a share of the outcome. Depending on the project, that might be a percentage of development profits, a fixed lump sum, or ownership of certain commercial assets.

Created more than 40 years ago to help finance the earliest lines, R+P became the flywheel: property gains help pay for new rail; new rail makes more property possible; and the finished developments create built-in ridership by placing dense communities directly on top of the network.

The intent isn’t only to make money. It’s also to make the railway work better. Real property contributes in two ways: first, it generates income that helps fund construction; second, once the housing and offices are completed, they immediately create a population catchment area that feeds passengers into the system every day.

And in practice, it’s funded real expansion. Revenue from R+P developments above stations along the Tseung Kwan O line, for example, financed the extension of that line to serve a new town that later grew to a population of 380,000.

Over time, the compounding gets enormous. MTR applied R+P extensively across the network. Buildings sit above about half of the system’s 87 stations, representing about 13 million square meters of floor area, with millions more in the pipeline. A significant portion of MTR’s investment-property portfolio—more than 267,000 square meters—came from these shared assets.

Zoom out to the corporate picture and you can see the split personality that makes MTR so unusual: between 2000 and 2012, property development made up 38% of corporate income, related businesses like leasing and commercial management made up 28%, and railway operations contributed 34%. In the early 2000s through 2007, property development even produced more net profit than running the trains.

The flagship expression of R+P is Union Square in West Kowloon: a massive mixed-use development built on reclaimed land above major rail infrastructure. The site covers 13.54 hectares, with a gross floor area of about 1.09 million square meters—roughly comparable in scale to Canary Wharf in London. This isn’t a station with a few shops. It’s an entire neighborhood engineered around rail.

Its most visible monument is the International Commerce Centre. Completed in 2010, the ICC is a 118-floor, 484-meter commercial skyscraper, owned and jointly developed by MTR Corporation and Sun Hung Kai Properties. It is Hong Kong’s tallest commercial building, and was, at the time, among the tallest in the world.

Then there’s Elements: MTR’s upscale mall sitting directly above the transport infrastructure and connected to Kowloon Station. Opened in 2007 as part of the Kowloon Station development, it spans over one million square feet and is organized around the five classical Chinese elements—wood, fire, earth, metal, and water. It houses roughly 120 shops and a wide range of dining options, and it plugs directly into the Airport Express line and the surrounding towers.

Put it all together and you get transit-oriented development at its most ambitious: the city’s tallest commercial building, a luxury mall, and prestige residential towers offering around 5,800 apartments—built as one integrated system with the station itself. The transport and the real estate aren’t merely adjacent. They’re physically part of the same structure, designed for what planners call seamless connectivity.

This integration doesn’t just generate cash for MTR—it changes how people live. Research has shown housing price premiums in the range of 5% to 17% for units built as part of R+P projects. When those projects have a distinctly transit-oriented design, the premium can exceed 30%. In plain language: people will pay meaningfully more for the ability to walk from home to train without stepping outside.

Hong Kong’s version of R+P shows what happens when a city ties infrastructure expansion to the value it creates—making public transit more financially self-reliant while shaping dense, rail-linked urban growth. But it also raises the obvious question: can other cities copy it?

The honest answer is: only if they share some of Hong Kong’s underlying conditions. The model works in part because of Hong Kong’s extreme density and scarce land, which makes real estate unusually valuable. Residents are accustomed to living close to transit and prize the convenience of direct station access. And the government’s insistence that MTR operate under prudent commercial principles gave everyone a reason to make the economics work.

Still, over time, critics have argued the model drifted beyond its original intent. In July 2021, the NGO Liber Research Community published a report detailing the history of MTR’s revenue model, stating that R+P was originally formed to offset unexpected financial difficulties in building the first lines, with early estimates that property would represent roughly 20% of total revenue.

The Executive Council also noted that revenue from property development was not originally envisaged as a way to finance the capital cost of the railway itself, but as a contingency reserve—something to offset excessive construction costs. The same report noted that by 2017, about 40% of MTR’s revenue came from property, and that what began as contingency funding had shifted into a model where property subsidised operations and the construction of new stations—an evolution it characterized as unsustainable.

That tension—between R+P as a prudent backstop and R+P as the central pillar—became an ongoing governance challenge. What’s not in dispute is that the model helped keep MTR financially strong while delivering high-quality transit at relatively affordable fares.

For investors, R+P creates both appeal and complexity. Railway operations offer steady, recurring revenue tied to Hong Kong’s daily movement. Property development is cyclical, tied to the real estate market and the timing of project completions. That dual engine is powerful—but it also means earnings can swing with property conditions, a dynamic that became especially relevant during Hong Kong’s recent property downturn.

V. The IPO: From Government Agency to Public Company (2000)

By the turn of the millennium, MTR had done something most metro systems never get to do: it had proven the economics. The network was expanding, Rail plus Property was throwing off real returns, and Octopus had shown the company could execute city-scale innovation. The obvious next question wasn’t whether MTR could run trains. It was how to fund the next decades of growth—and what kind of institution MTR was going to become.

On 5 October 2000, the Mass Transit Railway Corporation (MTRC) became Hong Kong’s first rail company to be partially privatised. Until then, it had been wholly owned by the Hong Kong government. Now, in a broader push to reduce the government’s holdings in public utilities, MTR was being asked to step into the public markets.

The corporate reset happened just before the listing. In June 2000, the company was re-established as MTR Corporation Limited after the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region Government sold 23% of its issued share capital to private investors in an Initial Public Offering. Shares began trading on the Stock Exchange of Hong Kong on 5 October 2000.

Demand was immediate. The IPO was initially set at one billion shares, then increased to 1.15 billion due to strong interest. By listing day, the company had about 600,000 shareholders. The float raised approximately HK$23 billion, one of Hong Kong’s largest offerings at the time, and MTR listed under stock code 0066. Less than a year later, in June 2001, it joined the Hang Seng Index—cementing it as a mainstream public-market name, not just a piece of infrastructure.

What made the offering compelling wasn’t just the story. The business already looked healthy. At the time of the IPO, MTR was operating with a surplus of HK$360 million, up from HK$278 million in 1997. In other words, this wasn’t a bailout disguised as a privatisation. It was a profitable, strategically important operator inviting investors in.

But going public didn’t simplify MTR’s identity—it complicated it. Overnight, MTR had to balance two sets of expectations that don’t always align: a public service mandate of affordable fares and high service quality, and shareholder expectations for returns. The government kept majority ownership, but private investors now had real skin in the game.

That hybrid structure became a defining feature. With the Hong Kong government holding roughly three-quarters of the shares, MTR could never forget its public purpose. At the same time, being publicly traded—with a board that included independent directors—introduced a level of market discipline that a pure government department simply doesn’t face. Public ownership, commercial incentives.

And the markets rewarded that credibility in another way: financing. The company became the first Hong Kong corporate borrower to obtain internationally recognized credit ratings, and it maintained ratings on par with the Hong Kong Government—supported by strong credit fundamentals, prudent financial management, and continuous government support. That sovereign-equivalent standing lowered borrowing costs and broadened access to capital, giving MTR a powerful toolset for the next phase of expansion.

For investors, the IPO offered something rare: exposure to a monopoly transport operator with a proven profit engine, backed by majority government ownership and implicit support, but run with the constraints—and expectations—of a public company. It was a uniquely stable foundation with real upside. And MTR was about to use it.

VI. The KCRC Merger: Creating a Rail Monopoly (2007)

With the IPO behind it and credibility in the public markets, MTR’s next move was less about building new tunnels and more about fixing a structural oddity in Hong Kong’s transport map. For decades, the city had two government-owned railways running in parallel worlds: MTR in the urban core, and the Kowloon–Canton Railway Corporation (KCRC) running lines through the New Territories and up to the mainland border.

Two operators meant two management structures, two sets of incentives, and—most visible to riders—two systems that didn’t always feel like one network. That fragmentation created inefficiencies in planning, operations, and fares. If Hong Kong was going to run rail as the backbone of the city, having the backbone split in two was increasingly hard to justify.

The milestone came on 2 December 2007, when the operations of KCRC were merged into MTR, launching a new era of Hong Kong railway development.

The deal itself took shape over months of careful negotiation, because KCRC and MTR weren’t mirror images. KCRC’s lines were generally less profitable, and it had been far less active in property development—meaning it didn’t have the same built-in financial flywheel. The government also had a political problem to manage: selling a wholly government-owned asset to a partially privatised company risked accusations that public infrastructure was being handed over too cheaply.

So the merger wasn’t structured as a clean asset sale. On 11 April 2006, the Hong Kong Government officially announced the proposed framework: under a non-binding memorandum of understanding, KCRC would grant MTR Corporation Limited (MTRCL) a service concession to operate the Kowloon–Canton Railway system for an initial 50-year period. In return, KCRC would receive a one-time upfront payment of HK$4.25 billion, a fixed annual payment of HK$750 million, and a variable annual payment tied to the revenue generated from operating the KCR system.

On top of that, MTRCL would pay HK$7.79 billion to acquire property and other related commercial interests.

The logic was straightforward: KCRC would keep ownership of the infrastructure, while MTR would run the trains and integrate the customer experience. That structure avoided the optics of “selling” KCRC, while still accomplishing the operational goal—one operator, one network.

Approval came from MTR’s minority shareholders at an extraordinary general meeting on 9 October 2007. Two months later, on 2 December 2007, MTRCL formally took over operations of the KCR network and unified the fare system across both railways. On that same day, KCRC granted the 50-year service concession (with the possibility of extension) in exchange for the annual payments, effectively bringing Hong Kong’s rail operations under MTRCL’s management.

For passengers, the change was immediate and tangible. The merger created a single, integrated rail network, and Adult Octopus Card holders saw fare reductions right away. More importantly, Hong Kong finally got what it had always needed its rail system to be: seamless. Transfers that used to feel like crossing a boundary between institutions now just felt like moving through the city.

For MTR, the payoff wasn’t only scale—though the operating footprint expanded dramatically. The merged network opened up fresh territory for the Rail plus Property model along the former KCRC lines. And strategically, it proved something MTR would soon lean on heavily: it could absorb a complex railway system, integrate operations and fares, and make the whole thing work as one.

That mattered, because the next chapter wasn’t going to be written only in Hong Kong. With the home market increasingly mature, MTR needed new growth. The KCRC merger wasn’t just consolidation—it was rehearsal for going global.

VII. Going Global: Exporting the MTR Model (2007–Present)

By the late 2000s, Hong Kong’s core network was starting to look like a finished product. The obvious way to keep growing wasn’t to squeeze yet another line into an already dense city. It was to take what MTR had become—an operator known for disciplined execution and near-fanatical reliability—and see if it could work somewhere else.

That was the bet: could MTR export its operating playbook to other cities, under other governments, with other politics, other unions, and other customer expectations?

MTR’s international push started in earnest after the KCRC merger. The approach was selective. Instead of chasing every headline-grabbing project, the company went after markets and contracts where it believed it could genuinely add value—and where the rules of the game made sustainable operations possible.

The United Kingdom quickly became the flagship. In November 2007, MTR entered the London market as a joint venture partner in London Overground Rail Operations Ltd (LOROL), holding that concession through 2016.

Then came the biggest prize: Crossrail. On 30 July 2014, MTR was awarded the Crossrail Train Operating Concession by Transport for London, and it began running services in May 2015 under the TfL Rail brand—what would later become the Elizabeth line. From August 2017, MTR also began operating South Western Railway, one of the UK’s largest franchises, as a joint venture with FirstGroup.

The Elizabeth line was the crown jewel. It stitched together existing railways with a brand-new set of tunnels under central London, creating a single, high-frequency east–west artery across the city. When the long-delayed, over-budget project finally opened to passengers in May 2022, it was immediately positioned as transformational: faster journeys from the west—including Heathrow and Berkshire—through central London, and out to the east.

MTR Elizabeth line, a wholly owned subsidiary of MTR Corporation, was responsible for the day-to-day operation of that new line. And the opening wasn’t just a ribbon-cutting moment for London—it was a proof point for Hong Kong: MTR could run a world-class metro-style service in a very different environment.

Performance became the story. MTR pointed to some of the highest punctuality and lowest cancellation rates among London and South East train operators. Even before the rollout of new high-capacity trains, the operator said its performance enhancement program nearly tripled the number of miles between technical incidents on an inherited fleet of ageing, 35-year-old trains.

But the UK also highlighted the hard truth about overseas rail: you can run the trains well and still lose the contract.

MTR’s Elizabeth line concession ended in 2025 when its contract with TfL expired in May. Operations transferred to GTS Rail Operations, owned by Go-Ahead Group, Tokyo Metro, and Sumitomo Corporation.

While the UK provided a global stage, Mainland China was the other major frontier—closer to home, and enormous in scale. In the Chinese Mainland, MTR now operates Beijing Metro Line 4, the Daxing Line, Lines 14, 16, and 17, Shenzhen Metro Line 4, and Hangzhou Metro Line 1 and Line 5. Beyond Greater China, the company operates and manages Melbourne’s Metropolitan Rail Service and Sydney Metro M1 Metro North West & Bankstown Line in Australia, and Stockholm Metro in Sweden.

MTR also worked to bring a version of its Rail plus Property instincts to the mainland. Building on the Hong Kong playbook, it expanded property businesses into cities including Beijing, Shenzhen, Tianjin, and Hangzhou. The first mainland property development project, Tiara—built on a development site at the Shenzhen Metro Line 4 Depot acquired by tender in 2011 through wholly owned subsidiaries—completed in 2017, with sales reported as well received and units handed over to buyers.

By this point, MTR’s footprint had become hard to picture in a single map. One longtime insider, Kam, described watching Hong Kong’s network grow to more than 270 kilometers, covering all 18 districts and including a high-speed rail connection to mainland China. Add in the overseas systems—London, Melbourne, Sydney, Stockholm, Shenzhen, Beijing, Hangzhou, and Macao—and the combined route length totals more than 3,300 kilometers.

Strategically, though, the most important point wasn’t the headline distance. It was the economics.

Internationally, MTR mostly operates under concessions: it’s paid to run service, not to harvest the property-value uplift around stations the way it does in Hong Kong. That tends to make overseas revenue more predictable—but also structurally lower-margin, because the property flywheel usually isn’t there.

For investors, that tradeoff cuts both ways. International expansion diversifies MTR away from Hong Kong’s property cycles, but it also exposes the company to competitive rebids and political risk. The loss of the Elizabeth line contract in 2025 was a reminder that even strong performance doesn’t guarantee renewal.

And while MTR was building this global portfolio, back home it was about to face the most damaging test of its modern history—one that had nothing to do with punctuality, and everything to do with governance.

VIII. The Sha Tin-Central Link Scandal: When Things Go Wrong (2018–2022)

Every great operator eventually gets its stress test—the kind that doesn’t show up in on-time metrics or customer-satisfaction surveys, but in governance, transparency, and whether the public still trusts you to build safely. For MTR, that test arrived in 2018, wrapped around what had already become Hong Kong’s most expensive rail project: the Sha Tin to Central Link.

The spark was Hung Hom station, a major interchange being rebuilt as part of the project. In May 2018, media reports alleged that contractors had cut corners on critical steel reinforcement work—shortening steel bars used to secure platform slabs so they would fit into couplers without being properly connected. Soon after, a whistleblower leaked more details to the press, claiming the construction quality at Hung Hom was substandard and that key connections were not what the design required.

From there, the story didn’t get simpler. It got louder.

As scrutiny spread beyond Hung Hom, new revelations surfaced about issues at other construction sites, including To Kwa Wan and Exhibition Centre stations. Hong Kong’s Secretary for Transport and Housing, Frank Chan, warned publicly that the Sha Tin to Central Link—priced at HK$97.1 billion—was likely headed for further cost overruns and more delays.

Then came the paperwork problem, which for MTR’s credibility may have been even more damaging than the steel. The government, which owns 75 per cent of MTR, said it found “huge discrepancies” in two project reports MTR submitted in June and July. The implication was brutal: not only were there construction issues, but what MTR was telling the government about those issues might not line up with reality.

That combination—alleged defects plus inconsistent reporting—turned a construction controversy into a full-blown governance crisis. How could work of this importance proceed without being caught? If changes were made, why wasn’t documentation complete? And if MTR didn’t have a clear line of sight into what contractors were doing on site, what else might be slipping?

The government commissioned an independent inquiry, and its conclusions were scathing. The inquiry heavily criticised both MTR and the main contractor, Leighton Asia, for “serious deficiencies” in management and supervision. It found “unacceptable incidents of poor workmanship on site compounded by lax supervision,” and said management fell below “reasonable competence.” At the same time, the inquiry concluded that the structures at and near Hung Hom station were safe and fit for purpose—an important reassurance, but not a reputational rescue.

One of the most striking details came in the final report: the expert adviser team estimated there were hundreds of shortened reinforcement bars and a significant number of couplers left unconnected. The report noted that unconnected couplers should have been visually obvious on site—and that in a properly managed and supervised project, it would be highly unusual for so many to go unnoticed and uncorrected.

There were consequences at the top. CEO Lincoln Leong notified the company of his wish to retire early. Projects Director Dr. Philco Wong resigned with immediate effect. Other managers also departed. The message was clear: this wasn’t being treated as a minor project hiccup. It was being treated as institutional failure.

And the project timetable kept slipping. In January 2020, Frank Chan announced that “Tuen Ma Line Phase 1” would open on 14 February 2020, with the rest of the Tuen Ma Line scheduled for 27 June 2021. The East Rail Line extensions were expected by June or July 2022. MTR later confirmed the extension would open on 15 May 2022.

The enduring damage of the Sha Tin to Central Link scandal wasn’t just about concrete and steel. It was about confidence.

It showed that even an operator famous for reliability can stumble badly when construction oversight, contractor management, and internal reporting discipline break down. It also showed how quickly the problem escalates when the public believes the issue isn’t only workmanship—but whether the truth is being surfaced quickly and cleanly to the government and to riders.

For investors, it punctured one of MTR’s most valuable assets: the assumption that the company could deliver major projects with the same precision it brought to daily operations. The direct financial hit came through delays and higher costs. The bigger cost was reputational—and once a transit operator loses trust, it’s hard to buy back.

And just as MTR was absorbing that blow, Hong Kong itself was about to enter a far more chaotic period—one that would turn stations and trains into front-line political territory.

IX. The 2019 Protests: MTR Caught in the Crossfire

If the Sha Tin–Central Link scandal cracked MTR’s reputation as a builder, 2019 attacked something even harder to repair: trust. What began as protests against an extradition bill escalated into months of unrest, and Hong Kong’s transit system—normally the city’s most neutral piece of shared infrastructure—was pulled into the center of the fight.

MTR quickly became a target. Protesters accused the railway operator of bowing to pressure from pro-Beijing voices by closing stations and by refusing to release CCTV footage related to a key flashpoint: the Prince Edward station incident. On the streets, the disruption was broader too—roadblocks, damaged traffic lights, buses immobilized, and objects thrown onto railway tracks. But it was the conflict inside the stations that turned MTR into a symbol.

The pivotal moment came on the night of August 31, 2019. After a day of protest, Hong Kong police entered Prince Edward station and were filmed using batons and pepper spray inside train carriages while arresting people in the station. The images ricocheted through the city and online: an enclosed subway platform, officers moving through cars, passengers pinned in place.

The episode became known as the 31 August Prince Edward station incident. Critics described it as the police version of the 2019 Yuen Long attack, and some accused police of behaving like terrorists. Rumors circulated that protesters had been beaten to death inside the station, which police denied. Regardless of what people believed, the effect on MTR was immediate: the company was no longer seen as just the operator of the trains. In the public imagination, it was now entangled in the conflict.

The aftermath was brutal for the network. MTR faced intense demands to release CCTV footage. It declined, citing privacy concerns and legal constraints. That refusal didn’t calm the situation—it became gasoline. MTR was accused of colluding with police, and stations became targets for vandalism and calls for boycotts.

Damage spread across the system: ticket machines smashed, entry gates wrecked, station facilities destroyed. The scale forced measures that would have sounded unthinkable a year earlier. The next day, MTR shut down completely—for the first time in its 40-year history. More than half the network was still shut three days later, and for a period, stations closed as early as 6:00 p.m. so crews could repair damage and staff could operate more safely.

The violence and vandalism didn’t stay contained to one night. During the march on 8 September, at least four stations were vandalised, including Central station, which was set on fire. At Causeway Bay station, at Exit D2, police threw tear gas at journalists even though protesters had already left the scene.

As the weeks wore on, MTR implemented station closures and service suspensions to reduce the risk of further clashes. Multiple lines were affected. Ridership fell sharply—down by as much as 30 percent in August 2019 compared with prior months.

And this was the trap MTR couldn’t escape. As a government-majority-owned company, it was viewed by protesters as part of the establishment. Decisions that might normally be treated as operational—closing a station for safety, refusing to release footage—were interpreted as political acts. At the same time, MTR still had public shareholders expecting it to keep service running and protect assets. In a city where the metro is the circulatory system, either choice felt like taking a side.

The costs piled up. Repairs ran into the hundreds of millions. The reputational damage—especially among younger residents who formed the core of the protests—was harder to measure, and arguably more lasting.

Prince Edward, in particular, remained a wound. For more than a year, on the last day of each month, pro-democracy supporters left white flowers and bowed in mourning—until stricter enforcement under the national security law brought those gatherings to a stop.

In a way, 2019 exposed the limits of MTR’s hybrid model. For decades, it had thrived at the intersection of public service and private profit. But when that intersection became politically contested, the same hybrid identity turned into a vulnerability: too governmental to be trusted by protesters, too commercially oriented to be seen as purely serving the public.

For investors, the message was sobering. Operational excellence can’t fully hedge political risk. Order returned after Beijing imposed the national security law in 2020, but the environment had changed. MTR’s trains could get back to running on time. Trust—and the sense of neutrality that makes a metro system feel like common ground—was far harder to restore.

X. Recovery and the Road Ahead

After the protests—and then the shock of COVID—MTR’s next job was simpler to describe than to execute: get Hong Kong moving again, and repair a business model built on movement.

The company did, gradually, put numbers behind that recovery. For the first half of this year, MTR reported a net profit of HK$6 billion—up almost 45 percent year-on-year—driven by rising ridership and stronger property income.

That same story showed up in the full-year picture. Patronage kept climbing, with passenger journeys on MTR’s domestic operations reaching 1.95 billion in 2024, edging back toward pre-pandemic levels. The high-speed rail link also rebounded, recording more than 26.7 million journeys. In comments on the annual results, CEO Jacob Kam pointed to the same flywheel that has powered MTR for decades: a notable recovery in property development under the Rail plus Property model.

Financially, 2024 was a return to headline strength. In its earnings report for the year ending December 31, 2024, MTR said total revenue rose to HK$60,011 million, a 5.3% increase from the year before. Net profit attributable to shareholders more than doubled to HK$15,772 million, supported by stronger recurrent businesses and property development. Profit from recurrent businesses jumped 68.4%, which MTR largely attributed to recovering patronage and solid performance from the High Speed Rail service.

But even as the results improved, MTR’s leadership was explicit that the context had changed. Kam said that while operating results were satisfactory in 2024, much of those profits would be committed to the substantial funding required to upgrade and renew existing lines—and to plan and build new railway projects. His message to investors was essentially: yes, the engine is running again, but the road ahead is expensive. The focus, he said, would remain financial prudence—cost management, optimising funding arrangements, and maintaining a strong balance sheet.

That spending is not subtle. Kam said planned expenditure between 2025 and 2027 would be about HK$90.8 billion, mostly for maintenance on existing railways and for new rail projects.

This is where leadership matters, and MTR’s choice is a continuity play. Dr. Jacob Kam Chak-pui joined the company in 1995 and worked his way through roles across safety, operations, projects, and the Mainland China and International Business divisions. He served as Operations Director from 2011 to 2016, then Managing Director – Operations and Mainland Business, before being appointed CEO on 1 April 2019. He has been on the Board since then, and as CEO he is responsible for the performance of the Company and its group companies in and outside Hong Kong.

Now Kam is transitioning to become chairman—part of a succession plan designed to keep MTR steady as it enters a capital-intensive decade.

Because this next phase isn’t just about running trains on time. MTR has also acknowledged a harder, more structural issue: the model needs to evolve. As the company has put it, the business model needs to be reinvented—finding new sources of income and ways to lower costs—because the financial commitment in the coming decade is massive. MTR was founded 45 years ago and was once seen as the most profitable rail company in the world, offering relatively affordable fares and reliable service thanks to Rail plus Property. But as operating conditions shift, the pressure is on to keep that promise without relying on the same tailwinds.

Some of the levers are clear. The company could raise cash by selling minority stakes in shopping malls or other commercial properties. It could also push harder on cost reduction through technology—automating train operations and repair works, among other system upgrades.

The story of MTR’s next chapter, then, isn’t a simple comeback narrative. It’s the challenge of staying “MTR”: commercially disciplined, operationally elite, and financially self-sustaining—at a time when maintaining the machine may cost as much as building it did in the first place.

XI. Investment Analysis: Bulls, Bears, and Critical KPIs

The Bull Case

The bull case for MTR is, at its core, a story about a rare kind of infrastructure business: one that behaves like a utility when you want stability, and like a real estate platform when you want upside.

Start with the obvious advantage: MTR runs Hong Kong’s heavy rail network. There’s no direct, like-for-like competitor underground. For most cross-harbor and cross-district trips, it isn’t just the best option—it’s the default. That monopoly-like position in one of the world’s most transit-oriented cities gives MTR a resilient base of demand.

Then there’s the second engine: Rail plus Property. MTR doesn’t rely only on the lumpy, headline-grabbing profits from selling apartments. It also earns recurring income from the everyday commerce that sits on top of the railway: station retail kiosks, advertising, and investment properties like shopping malls above stations. In other words, even when development profits swing year to year, the leasing and management portfolio helps smooth the ride.

The balance sheet matters too. MTR’s sovereign-equivalent credit ratings translate into cheaper, easier access to capital—critical for a business that’s always building, renewing, and upgrading. And the ownership structure provides a unique kind of protection: the Hong Kong government’s roughly 75% stake implies support and alignment with the city’s long-term transport policy, while the public listing still imposes market discipline.

Finally, there’s diversification. International concessions don’t come with Hong Kong-style property upside, but they do broaden the earnings base and keep MTR from being purely a Hong Kong story.

Put those pieces together and you can see why investors often describe MTR as a portfolio. In a normalized environment, one way to think about the profit mix is: rail operations as the steady foundation, station commercial and property leasing as the largest recurring contributor, and property development as the swing factor that can dramatically lift results in good years. The return toward pre-pandemic ridership levels, plus the rebound in the high-speed rail connection to mainland China, reinforces the idea that the core transport engine is still intact—even if property development remains cyclical.

The Bear Case

The bear case is what happens when the flywheel slows.

The biggest risk is property. Hong Kong’s property market has weakened materially, and that pressure goes straight to the heart of Rail plus Property. The model works best when property values are stable or rising. In a downturn, development profits can evaporate, project economics get tighter, and land and property valuations come under pressure. If property can’t reliably subsidize the broader system the way it once did, MTR’s historical formula becomes harder to sustain.

Layer on the post-2019 political shift. Whether you view it as stabilizing or constraining, the environment is different now, and that has downstream implications for Hong Kong’s economic vitality, talent flows, and long-term population trends—all of which ultimately feed transit demand and real estate demand.

Internationally, the company also has less control than it does at home. The loss of the Elizabeth line contract is the reminder: concessions are competitive, and strong performance doesn’t guarantee renewal.

And then there’s maturity. Hong Kong’s network is already dense and comprehensive, which limits organic growth. Expansion is still possible, but it tends to be harder, more expensive, and more politically sensitive than earlier buildouts.

Finally, governance risk isn’t theoretical. The Sha Tin–Central Link scandal showed that even a best-in-class operator can stumble badly on major capital projects, and that contractor oversight and internal reporting can become existential issues when they fail.

MTR itself has acknowledged the need to reinvent parts of its model. The coming decade requires enormous spending on maintenance, renewal, and new projects. The central question for the bear case is simple: can MTR keep the system world-class, keep fares politically acceptable, and still generate sufficient returns if the property engine stays subdued?

Porter's Five Forces Analysis

Threat of New Entrants (Low): The barriers are enormous—capital, regulation, land access, and political alignment. The KCRC merger also eliminated the only meaningful local alternative operator.

Supplier Power (Moderate): MTR depends on major contractors and rolling-stock suppliers. Its scale gives it leverage, but the Sha Tin–Central Link experience showed how costly supplier and contractor failures can be.

Buyer Power (Low): Riders have alternatives—buses, minibuses, ferries—but not true substitutes for speed and capacity on many key corridors. The Fare Adjustment Mechanism also makes pricing more predictable than a purely commercial fare-setting regime.

Threat of Substitutes (Moderate but Increasing): For short trips, buses compete. The more structural substitute is behavioral: remote and hybrid work have reduced commuting intensity since the pandemic, and that shift hits every urban transit system.

Competitive Rivalry (Low in Hong Kong, High Internationally): At home, MTR is effectively the rail system. Abroad, concessions are contested, time-limited, and subject to rebid risk.

Hamilton Helmer's 7 Powers Framework

Network Economies: Limited in pure operations, but the Octopus ecosystem creates real convenience and some switching friction.

Scale Economies: Significant. High volume spreads fixed costs, and few systems globally operate at Hong Kong’s density and throughput.

Cornered Resource: Rail plus Property is effectively exclusive to MTR because it depends on government policy, land mechanisms, and institutional relationships built over decades.

Process Power: MTR’s operating discipline and reliability represent real accumulated know-how, even if its construction governance reputation took damage during Sha Tin–Central Link.

Counter-Positioning: Not a major factor here; MTR is the incumbent.

Switching Costs: Moderate. Octopus and habitual commuter patterns matter, and many households and businesses choose locations specifically for MTR access.

Branding: MTR remains synonymous with getting around Hong Kong. The 2019 protests weakened trust in parts of the public, but the brand’s functional importance endured.

Critical KPIs to Monitor

1. Passenger Journeys (Domestic Services): This is the heartbeat of the business. Before the pandemic, domestic journeys were above two billion a year. By 2024, the figure had climbed back to about 1.95 billion. The key is the trend line: is ridership fully normalizing, or has hybrid work permanently reset demand?

2. Property Development Profit Contribution: This is the swing factor. It’s inherently lumpy—driven by project completion timing and market conditions—but if development contributions stay depressed for an extended period, it’s a sign the traditional R+P flywheel is under structural pressure.

3. Recurrent EBIT (Hong Kong Station Commercial & Property Rental): This is the stabilizer: leasing and station commercial income. Watch it for early signs of stress—tenant weakness, rental step-downs, or softer mall performance—because it’s the recurring cash flow that underwrites the rest of the machine.

XII. Conclusion: The Next Fifty Years

MTR stands at another hinge moment. The company that pioneered Rail plus Property, took blows from the 2019 protests, rode out the pandemic, and still managed to deliver record profits in 2024 now faces a tougher set of questions than “can we run trains on time?”

Can Rail plus Property keep doing what it has always done if Hong Kong’s property market stays weaker for longer? Can MTR actually reinvent the model—finding new income streams and lower-cost ways to operate—without losing the commercial discipline that made it so unusual in the first place? And can international operations provide meaningful growth as the home network matures?

Those aren’t academic questions. They’re the ones that will shape MTR’s next decade, and likely investor returns too.

Still, it’s worth pausing on what MTR has already pulled off. From a standing start in 1975, it built one of the world’s best metro systems without direct operating subsidies—a feat almost no other major city has replicated at scale. It created wealth not only for shareholders, but also for the Hong Kong government through land premiums and dividends, and for residents through affordable, reliable transport. And it didn’t keep that expertise at home; it exported it.

CEO Jacob Kam has argued that Rail plus Property is bigger than a financing trick. “R+P forces railway development to be city-friendly,” he says. “For our projects to succeed, we have to be more concerned about ensuring their smooth integration with the surrounding areas rather than just building a railway.” MTR’s mission is to Keep Cities Moving—and, in Kam’s telling, that’s not only about mobility, but about helping a city advance.

In the end, the MTR story is about incentives that were engineered to line up. Give the railway a stake in development, and it plans stations as places people want to live and work, not just points on a map. Require commercial viability, and you get operational discipline. Keep majority government ownership, and you preserve public accountability even as private shareholders demand performance.

None of this makes MTR flawless. The Sha Tin–Central Link scandal and the trauma of 2019 were real, and the reputational damage was lasting. But the core innovation—capturing the land value that transit creates and using it to fund the transit itself—remains one of the cleanest solutions to the hardest problem in urban infrastructure: how to pay for it without permanently bleeding taxpayers.

For investors, that leaves MTR as a rare kind of asset: a monopoly-like urban rail operator with sovereign-equivalent credit support, plus a property and station-commercial engine that can be powerful when conditions cooperate. The risks are just as real—property dependence, political uncertainty, and the limits of growth in a mature network. But very few infrastructure businesses combine MTR’s operational excellence with a model that can, at least in its best years, sustain itself.

And for the rest of the world, MTR remains a case study that refuses to be ignored. Cities study it, admire it, and try to copy it. Most fail, because they don’t share Hong Kong’s unique ingredients: extreme density, scarce land, government control over land supply, and the long-term commitment to commercial discipline. But the underlying principles travel better than the exact blueprint: capture the value you create, integrate transport and development from day one, and run public infrastructure with real economic accountability.

After fifty years, MTR is still what it set out to be—just on a scale few would have dared to predict: a railway that doesn’t have to live on subsidies, a developer that builds communities around mobility, and proof that public infrastructure and commercial success can reinforce each other, rather than collide.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music