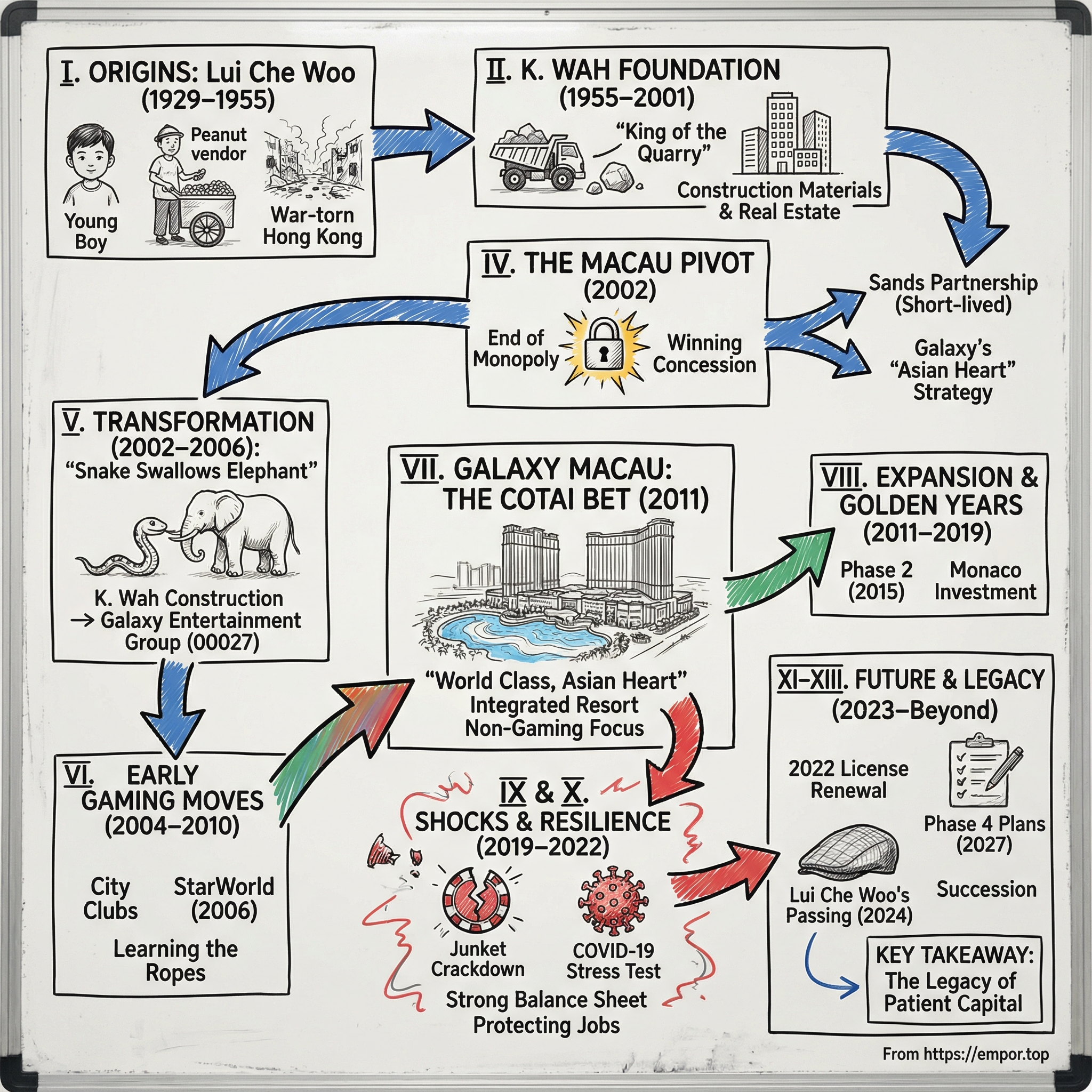

Galaxy Entertainment Group: The Story of Asia's Gaming Empire

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

Picture the scene: December 2024, a formal gathering in Hong Kong. Mourners in dark suits file past, paying tribute to a man in his trademark flat cap—Lui Che Woo, who has just died at 95. Tributes arrive from government leaders, business titans, and casino executives around the world.

And yet, for most of his career, Lui wasn’t a casino tycoon at all. He was a quarry owner. A construction materials operator. A property developer. A hotel builder. Unlike the two late “Kings of Gambling,” Stanley Ho and Sheldon Adelson, Lui didn’t enter gaming until he was 73—an industry he’d had nothing to do with for the first three quarters of his life.

That’s the hook. Because this isn’t just a Macau story. It’s one of the most audacious late-career reinventions in modern business.

How does a Hong Kong construction materials company become one of the world’s largest casino operators? And why would a self-made tycoon—already wealthy, already established—decide to bet on an industry he didn’t grow up in, at an age when most people are stepping away from the arena, not charging into it?

Today, Galaxy Entertainment Group is one of the world’s leading resorts, hospitality, and gaming companies. In Macau, it develops and operates a portfolio that spans casinos, hotels, dining, retail, and entertainment. Galaxy Macau alone offers around 5,000 rooms, suites, and villas across eight luxury hotels. And it anchors the city’s live-events scene too: Galaxy Arena is Macau’s largest indoor venue, with 16,000 seats.

The business is enormous. In 2024, Galaxy reported 22 percent growth in revenue to HK$43.4 billion. EBITDA rose 22 percent to HK$12.2 billion, and profit attributable to shareholders climbed 28 percent to HK$8.8 billion. By year-end, it held HK$31.3 billion in cash and liquid investments, and after accounting for HK$4.2 billion of debt, sat on a net cash position of HK$27.1 billion.

But the most interesting part isn’t the scale—it’s what Galaxy represents. A company built on strategic patience. On threading the needle of Chinese politics and regulation. And, crucially, on building for the mass market while so many competitors built their fortunes around VIP high rollers.

This is the story of Galaxy Entertainment Group.

II. Origins: The Making of Lui Che Woo (1929–1955)

Galaxy’s story doesn’t begin under chandeliers on Cotai. It begins in wartime southern China.

Lui Che Woo was born on August 9, 1929, in Jiangmen, Guangdong—just across the border from Hong Kong. In 1934, his family moved into the then-British colony. They weren’t poor. Lui grew up around commerce: his father had spent years traveling with his own father, then went back to the mainland to build ventures of his own, including a winery. In those early years, the Lius lived comfortably.

Then history intervened. War shattered that stability, and when Japan invaded Hong Kong in 1941, the family’s fortunes were wiped out. The businesses that had supported them disappeared almost overnight.

For Lui, the rupture was permanent. He finished primary school in Kowloon’s Yau Ma Tei area, but in a 2019 interview he said he quit in the first year of secondary school because he didn’t want to study Japanese. It reads like a small decision, but it changed everything: no diploma, no safety net, and no clear path forward.

So he worked.

As a teenager, Lui sold peanuts and peanut brittle to people lining up to leave Hong Kong’s turmoil. Later, he recalled a Cantonese phrase—“sam nin ling bat goh yuet,” literally “three years and eight months”—a reference to the 44-month occupation. His point wasn’t poetic. It was practical: the family survived. “During those sam nin ling bat goh yuet, we didn't go hungry.”

What matters is what he took from it. In later years, Lui would say those hard stretches trained him to weigh risk, to stay alert for opportunity when others only saw chaos, and to maintain what he called “positive energy.” In his case, it wasn’t motivational talk. It was a method.

After the war, he followed his uncle into a car parts trading company, starting as a stock keeper. By around 20, he had already branched out—buying another firm and pushing into trading on his own. And then he heard about something that would prove decisive: surplus U.S. military equipment being auctioned off in Okinawa.

In the early 1950s, he traveled to Okinawa to approach the U.S. Army and the Consulate about buying heavy equipment left behind after the Korean War—heavy goods vehicles, drilling machines, the kind of industrial muscle a rebuilding city suddenly can’t get enough of. He shipped it back to Hong Kong, where it could be put to work immediately on infrastructure and construction.

While others saw leftover machinery, Lui saw leverage.

Hong Kong was on the edge of a construction surge—reclamation, new districts, and a city racing to modernize. In 1955, he founded K. Wah Company in Hong Kong and joined the wave, supplying materials for large-scale land reclamation projects around Kwun Tong, including Sau Mau Ping, Lok Fu, Lam Tin, and Yau Tong. Over time, K. Wah became a leader in construction materials, and Lui earned a nickname that captured exactly where he’d positioned himself: the “King of the Quarry.”

By 26, with only a primary school education and a life shaped by occupation and loss, Lui Che Woo had planted himself at the center of Hong Kong’s economic transformation. The teenager who sold peanuts to get through the war was now supplying the raw inputs of a growing city.

III. Building the K. Wah Empire: Quarries, Real Estate & Hotels (1955–2001)

The four decades between founding K. Wah and entering gaming read like a masterclass in patient compounding. The young Lui had shown flashes of opportunism in Okinawa. The older Lui proved he could do something even harder: stack small advantages for years, then decades, without losing focus.

In the 1960s, he secured the right to quarry at the Anderson Road Quarry Site—Hong Kong’s first rock quarry site. And he didn’t run it the way everyone else did. Lui pushed mechanization early, using automated equipment to replace the manual mining that dominated the industry at the time.

That shift wasn’t just about working faster. It created a moat. Mechanization meant lower unit costs, steadier output, and more consistent quality—exactly what a city pouring concrete at breakneck speed needed. K. Wah’s construction materials ended up shaping huge swaths of Hong Kong’s built environment, while the company positioned itself at the vanguard of efficient and safe quarrying.

In 1991, K. Wah Construction Materials Limited listed in Hong Kong under stock code 00027. At the time, it was simply the public face of a quarry-and-materials business. But that listing would matter later, because the corporate vehicle behind 00027 would eventually become something no one would have predicted: Galaxy Entertainment Group.

Even as the materials business scaled, Lui kept widening the base. Starting in the 1960s, he began investing in property development—first in Hong Kong, then steadily outward into Mainland China, Macau, Southeast Asia, and beyond. In 1987, he listed K. Wah International Holdings in Hong Kong. And when Mainland China began its reform and opening up, Lui was among the early Hong Kong construction materials entrepreneurs to enter the market, taking his playbook north just as the next construction boom was getting started.

The move into property made intuitive sense. If you supply the raw inputs for the city, the next step up the value chain is to help build the city itself.

Hotels were different. Hotels weren’t vertical integration; they were a bet on a consumer future. Lui began investing the profits from construction into residential development and then hospitality in Hong Kong. In 1979, he began building his first major hotel—originally a Holiday Inn, later rebranded as the InterContinental Grand Stanford. Built for HK$300 million, it was valued at more than HK$1 billion by the 1990s and became the group’s flagship.

That deal helped validate something important: Lui wasn’t only a supplier to developers—he could be a destination builder. Over time, he amassed hotel and serviced apartment assets around the world, earning him a “Hotel Tycoon” reputation in Chinese-language business circles.

By the late 1990s, K. Wah had become a true conglomerate: two listed flagships—K. Wah International Holdings and what would eventually become Galaxy Entertainment Group—along with major operating companies like K. Wah Construction Materials and Stanford Hotels International, and hundreds of subsidiaries spanning property, hospitality, construction materials, and leisure across Greater China and abroad.

And yet, the man at the center of it stayed famously low-key. Lui was one of Hong Kong’s most discreet tycoons—an executive who’d rather talk about golf and mahjong than personal wealth. At public events, he was often seen in his distinctive flat cap, a visual shorthand for his modest, unshowy persona.

The cap became a kind of signature: a billionaire who collected hats instead of headlines, who built through patience rather than spectacle. That temperament matters, because it sets up the twist in the story.

When Lui Che Woo eventually stepped into gaming at 73, it wasn’t a late-life thrill ride. It was the same thing he’d been doing for forty years—quietly identifying where the world was going next, and placing a disciplined, calculated bet.

IV. The Macau Opportunity: End of the Stanley Ho Monopoly (1999–2002)

To understand why 2002 was such a hinge point, you first have to understand what Macau had been for the previous forty years: a one-company town.

In 1962, the Macau government granted a monopoly on casino gambling to Sociedade de Turismo e Diversões de Macau, better known as STDM. The man behind it was Stanley Ho—the Hong Kong–Macau billionaire who became synonymous with the business. Ho would later found and chair SJM Holdings, the operator behind a sprawling stable of properties, including the Grand Lisboa. In an industry built on spectacle, his nickname said it all: the “King of Gambling.”

For decades, STDM effectively was the market. The monopoly meant one dominant operator controlling the industry’s destiny—who could open, where, and under what rules. But by the end of the 1990s, that structure was becoming increasingly hard to justify. Macau was changing, and its politics were about to change with it.

On December 20, 1999, Macau transferred from Portuguese administration to China. The new era came with a new mandate: modernize, diversify, and bring in outside capital and expertise. Ending the concentration of power in one concessionaire wasn’t just an economic decision; it was a governance decision.

By 2000, the government had begun laying the groundwork to liberalize the industry, proposing a structure that would open parts of Macau’s casino business to bidding. Then, in 2002, it made the break official. After legal reforms and a public tender, STDM’s monopoly—running from January 1, 1962—ended on March 31, 2002, clearing the way for three new gaming concessions.

The tender instantly became a global event. Las Vegas giants like Las Vegas Sands and Wynn saw Macau as the ultimate growth market: China-adjacent, newly open, and positioned to become the region’s tourism magnet.

And that’s when one of the strangest winners on paper walked away with a license.

In 2002, Macau opened up its gaming market and issued three concessions through a competitive bidding process. Eighteen bidders went after them—many with deep casino resumes. Among them, Lui Che Woo’s Galaxy Entertainment Group, a company whose roots were in quarries and construction materials, won one of the three.

How did that happen?

Part of the answer ran through Las Vegas Sands. Just two days before the Macau government announced the tender results, the Venetian Macau abruptly pulled out of its partnership with a Taiwan-based firm, Asian American Entertainment Corp. Las Vegas Sands, led by Sheldon Adelson, suddenly needed a new local partner—and needed one fast.

It found one in Galaxy. Las Vegas Sands and Galaxy teamed up, and that pairing proved powerful in the eyes of regulators. Former gaming commission member Maria Nazaré Saias Portela later described how the commission believed Las Vegas Sands could bring the Las Vegas Strip’s integrated resort and MICE model to Macau. In that environment, a credible partnership with the Venetian raised a bidder’s odds.

There was also a second layer to the story, discussed more quietly at the time: politics. Lui was widely recognized in Hong Kong and Macau as an influential businessman with connections in Beijing, including his role as a member of the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference. In a tender where political comfort mattered alongside the business plan, those relationships didn’t hurt.

Adelson himself later praised Galaxy, saying that under Lui’s leadership the company had “significant strength in both management and construction,” and would help lead Macau’s development into a global gaming, tourism, and MICE destination.

But even in the glow of a shared victory, the partnership was unstable. People described what followed as “a snake trying to swallow an elephant”—a mismatch in size, influence, and ambition. Galaxy and the Venetian had initially planned to operate the concession together. Within a year, they split the license and decided to run separately after clashing over strategy.

At the heart of the breakup was a simple disagreement about what Macau should become. Adelson wanted to recreate Las Vegas in China. Lui wanted something built for Asian guests. That meant everything from food to wayfinding—Chinese restaurants, clearer entrances and exits, and a layout that didn’t feel like a maze. Francis Lui recalled in a 2006 interview with Next Magazine that his father compared American casinos to labyrinths.

That split didn’t just end a partnership. It set Galaxy’s identity. And in hindsight, it also set up the company’s biggest advantage: an “Asian Heart” approach that would later prove far more durable when the VIP-heavy model that powered Macau’s boom came under pressure from Beijing.

V. The Snake Swallowing the Elephant: Corporate Restructuring (2002–2006)

The partnership split with the Venetian solved one problem—strategy. But it left Galaxy with a bigger one: structure.

Because what Macau had handed out in 2002 wasn’t a casino. It was permission. A gaming concession is only valuable if you can finance it, scale it, and convince the market you’re a serious operator. And for a company whose public face was still “K. Wah Construction Materials,” that required a corporate metamorphosis.

Here’s the move. The Hong Kong-listed construction materials company—formerly K. Wah Construction Materials—shed its legacy business and, in 2005, acquired a 97.9% stake in Galaxy Casino S.A. Overnight, the listed vehicle that investors associated with quarries and aggregates became the only Hong Kong-listed company that held a Macau gaming operating license.

It was as radical as it sounds. The shell stayed the same. The destination changed completely.

People at the time reached for a vivid metaphor: “a snake trying to swallow an elephant.” A mid-cap construction materials business was attempting to absorb an asset class that could be worth billions, in an industry it had never operated before.

But the brilliance of the restructuring wasn’t just that it worked. It created something strategically unusual in Macau: a major concessionaire that was already public, already liquid, and already easy for global investors to access through the Hong Kong Stock Exchange—while foreign competitors still had to figure out how to marry Macau ambitions with market structure.

Control stayed firmly with the founder. Contemporary reports put the Lui family’s stake at about 73.6%. And the economics of the whole transformation were staggering: over roughly three years, Lui had invested about HK$612 million, yet through the restructuring he received stocks and interest-bearing bonds valued at HK$13.8 billion—implying a paper gain of around HK$13.2 billion.

Those figures mattered for more than bragging rights. They created the financial foundation that, years later, would help Galaxy endure shocks that wrecked weaker players—when travel collapsed during COVID, and when Beijing’s crackdown on junkets hollowed out VIP-driven revenues.

Then came the regulatory fine print that reshaped the whole market. In late 2002, negotiations with the Macau government led to each of the three new concessions being “sub-concessioned” once—turning three licenses into six operators. After Galaxy and Las Vegas Sands went their separate ways, they ended up operating independently within that framework: Galaxy retained the gaming concession, while LVS received Macau’s first sub-concession.

By October 26, 2005, the rebranding caught up with reality. The company formally changed its name to Galaxy Entertainment Group Limited.

On paper, the quarry king had become a casino mogul. Now he had to prove it in the only place that counts: on the gaming floor, competing against operators who’d been running casinos for decades.

VI. First Moves: City Clubs & StarWorld (2004–2010)

Galaxy had a concession on paper in 2002. What it needed next was operating experience—fast.

So instead of leaping straight into a billion-dollar monument on Cotai, Galaxy entered Macau the way a quarry-and-construction entrepreneur would: start with manageable sites, learn the trade, and scale only once the fundamentals are proven. In 2004, through Galaxy Casino S.A., the group opened the first of what would become four “City Club” casinos—smaller venues built into existing properties. They were a practical training ground: build a customer base, hire the right people, get a feel for regulators, and learn what actually drives traffic on a Macau gaming floor.

The first real test came on July 4, 2004, with the opening of the Galaxy Waldo Hotel. Galaxy invested MOP$500 million to revive an unfinished commercial building and turn it into a working casino hotel. The Waldo was a 16-story property with a three-story underground car park, and in its first phase it ran 23 gaming tables and 83 slot machines. It wasn’t meant to be glamorous. It was meant to work.

Then Galaxy made its first big statement.

On October 19, 2006, StarWorld Macau opened on the Macau Peninsula, right in the heart of the city’s traditional gaming district. This was no longer a “learn the ropes” venue. StarWorld was a 500-room luxury hotel and casino built to compete head-to-head with the established giants, pairing high-stakes gaming with entertainment and a more premium feel. If the City Clubs were Galaxy proving it could operate, StarWorld was Galaxy announcing it intended to win.

The market responded immediately. Net gaming revenue jumped from HK$1.3 billion in 2005 to HK$4.7 billion in 2006, propelled by StarWorld’s launch and the broader Macau boom.

Over the next few years, Galaxy became a major force in the VIP segment—exactly where the money was in the mid-2000s. Macau was rapidly becoming the world’s single biggest gaming market, and VIP baccarat was its engine. High rollers from Mainland China arrived in waves, and the junket operators who brought them in—recruiting players, extending credit, handling collections—became the ecosystem’s kingmakers.

It’s worth pausing on the irony: the VIP model that helped power Galaxy’s early rise would later become one of the industry’s greatest liabilities. But in that moment, it looked like a one-way bet.

And even here, Galaxy showed a trait that would matter later: discipline. While some competitors stretched themselves chasing growth, Galaxy kept a more conservative financial posture. It was the same mindset Lui had practiced for decades in construction—assume cycles are inevitable, and make sure you’re still standing when they arrive.

VII. Galaxy Macau: The Big Bet on Cotai (2011)

Cotai changed the rules of the game. If the Macau Peninsula was the industry’s historic heart, Cotai—reclaimed land between Taipa and Coloane—was its future. Las Vegas Sands got there first, opening The Venetian Macao in 2007 and instantly redefining what “Macau casino” could mean. Galaxy watched that shift closely. Then it decided not to copy it. It decided to beat it in a different way.

Galaxy’s Cotai project had been in the works for years. Construction began back in 2002, but the opening date slipped multiple times as the company refined what it wanted to build. Finally, on March 10, 2011, Galaxy announced that its HKD 14.9 billion resort—designed by Gary Goddard—would open on May 15.

When the doors opened that day, Galaxy Macau didn’t feel like a Vegas transplant. Phase 1 debuted with three Asian-led hotel brands under one roof: Banyan Tree Macau, Galaxy Hotel™, and Hotel Okura Macau. Banyan Tree and Okura were entering Macau for the first time, and the message was deliberate. This was positioned as an integrated resort built around Asian hospitality, Asian service instincts, and Asian guest expectations—not a Western template dropped onto Chinese soil.

That choice traced directly back to Lui Che Woo’s split with Sheldon Adelson. Galaxy’s identity had hardened into a thesis: “World Class, Asian Heart.” Not labyrinthine casino floors meant to trap you inside, but a property designed to be navigable. Not a dining lineup anchored in steakhouse tropes, but Chinese cuisine given pride of place. Not just gaming, but a full resort experience that could pull in families, groups, and mass-market visitors—not only VIPs.

As Francis Lui, Galaxy’s Vice Chairman, put it at the time: “We believe Galaxy Macau will help lead this development by introducing impeccable service delivered with ‘World Class, Asian Heart’ along with industry-leading amenities and true resort features.” He called the opening “the biggest event in Macau this year,” and emphasized it marked five years of design, planning, and construction.

And Galaxy backed that talk with spectacle. The resort’s signature was its Grand Resort Deck: 75,000 square meters of over-the-top leisure infrastructure, including a 150-meter white sand beach, the Skytop Adventure Rapids stretching 575 meters, and what the company billed as the largest skytop wave pool. This was the point: to be a resort you’d visit even if you didn’t care about gambling. To create reasons to come—and reasons to stay.

Inside, the scale matched the ambition. When the first phase opened in 2011, the property spanned roughly 550,000 square meters and offered around 2,200 hotel rooms, alongside casino and entertainment areas. It was Galaxy’s leap from operating strong individual properties to building a destination.

In the integrated resort industry, Lui would always be remembered as the man who founded the company that created what is very arguably the greatest single integrated resort the planet has ever seen: Galaxy Macau.

The opening ceremony drew high-ranking officials and industry leaders, a reminder that in Macau, gaming is never just business. Speaking hours before the launch, Lui framed it as something bigger than a new casino: “The opening of Galaxy Macau signals a new era for Macau as a world-class leisure destination.” He stressed Galaxy’s role “as part of the fabric of Macau and an employer of thousands of Macanese,” and said the company attached “great importance to the growth and evolution of the local tourism industry.”

For investors, though, the moment carried a simpler meaning. Galaxy had spent years pouring concrete, managing delays, and building the physical proof of its strategy. Now it had to do the only thing that ultimately matters in Macau: make it work, day after day, on the floor.

VIII. The Golden Years & Expansion (2011–2019)

In the years after Galaxy Macau opened, Macau went on a run that’s hard to overstate. Gaming revenue surged to a record around 2013, hitting roughly US$45 billion—about seven times the Las Vegas Strip—and it remained enormous in 2014 as well. At the peak, gambling wasn’t just an industry in Macau; it was the economy, contributing the vast majority of GDP.

Galaxy rode that wave—but it also used it.

Even before the market topped out, the company was already planning its next step on Cotai. In investor materials, Galaxy pegged the cost of Phase 2 at about HK$16 billion, with completion targeted for mid-2015. The plan was to add roughly 450,000 square meters of new resort space, expand room capacity across more hotels, and scale up gaming.

Phase 2 opened on May 27, 2015—and it was a statement. Galaxy Macau and the new Broadway Macau development effectively doubled the footprint of the original resort to more than 1.1 million square meters. Three new hotels anchored the expansion: The Ritz-Carlton, Macau—built as the brand’s first all-suite hotel globally—plus JW Marriott Macau, billed as the largest JW Marriott in Asia, and the Broadway Hotel, a smaller boutique-style property.

The ambition came with a price tag. Galaxy described the Phase 2 build-out as part of a much larger capital commitment to Macau—more than HK$43 billion invested as a step toward a planned HK$100 billion.

Then Galaxy did something else that mattered: it started looking beyond Macau.

In July 2015, Galaxy made its first strategic investment outside the city, buying a 5% stake in Monaco’s Société Anonyme des Bains de Mer et du Cercle des Étrangers à Monaco—better known as Monte-Carlo SBM. It was a portfolio that read like a luxury travel bucket list: the Casino de Monte-Carlo, Café de Paris, and other casino properties, plus landmark hotels like Hôtel de Paris Monte-Carlo and Hôtel Hermitage Monte-Carlo, alongside resort assets such as Monte-Carlo Beach and Monte-Carlo Bay Hotel & Resort.

The message was clear. Galaxy didn’t want to be seen as only a Macau casino operator. It wanted the global halo of a luxury resort group. Lui Che Woo framed it that way, calling SBM “one of the most iconic, luxury, hospitality brands in the world,” and pointing to Galaxy Macau’s post-2011 reputation for building and operating “some of the most spectacular integrated resorts” anywhere.

But even in the middle of the boom, the foundations of Macau’s old model were starting to crack.

For years, VIP baccarat had been the engine—powered by junket operators who recruited mainland gamblers, extended credit, and helped move money across borders. Over time, that ecosystem became politically fragile. Beijing’s anti-corruption push deterred high-stakes play, and the impact showed up quickly in the numbers: Macau’s gross gaming revenue fell sharply in 2015, and the VIP segment took the hardest hit.

Galaxy got bruised too. But the company’s “Asian Heart” strategy—leaning more toward mass-market visitors—and its balance sheet strength helped it hold up better than rivals that were more exposed to VIP. And when the market recovered to near-peak levels by 2018, Galaxy came out of the downcycle not weakened, but better positioned.

IX. The Junket Crackdown: A Fundamental Industry Shift (2019–2022)

The arrest of Alvin Chau on November 27, 2021 didn’t just take down a single executive. It effectively pulled the plug on an entire era of Macau.

Chau was the founder of Suncity Group and, for years, the face of the junket system that powered the city’s VIP boom. The model was as lucrative as it was fragile: junket operators brought high rollers from Mainland China—where marketing or soliciting gambling is illegal—to Macau, the only place in China where casino gambling is legal. They handled the hard parts too: extending credit to wealthy gamblers, then collecting debts on behalf of the casinos.

By the time Chau was arrested, Suncity was widely seen as the biggest junket in Macau. Even as COVID-19 strangled travel through 2021, it remained the go-to operator in the VIP ecosystem, a central artery in the way money and players flowed through the market. Observers routinely described the scale in blunt terms: if Suncity controlled a majority share of junket revenue, and junkets drove a huge portion of gaming revenue, then the company’s collapse was never going to be contained. The message was unmistakable: Suncity was no longer too big to fail.

The Suncity story also tied directly back to Galaxy. The company was founded in 2007, and its first VIP room was at StarWorld on the Macau Peninsula—Galaxy’s own flagship property at the time. Over a 14-year run, Suncity expanded aggressively, operating as many as 17 VIP rooms in Macau at its peak, plus rooms in the Philippines, Cambodia, and as far away as Australia.

Then the legal details came out—and they were damning. The trial found that Chau began operating VIP rooms in Macau in 2007, and from 2015 set up online gambling platforms in the Philippines and other countries. Prosecutors alleged that to maximize profits, he recruited agents with commissions and dividends, using them to attract Chinese nationals to gamble in Suncity-run rooms or to participate in cross-border online gambling.

The fallout was immediate. Suncity Group Holdings closed all of its VIP gaming rooms in Macau and reportedly stopped paying some staff, with the shutdown expected to cut a significant portion of its local headcount. Later, Chau—once nicknamed Macau’s “junket king”—was sentenced to 18 years in prison for running an illegal gambling empire.

Regulators and casino operators moved fast to distance themselves from the model. Caixin reported that four of the six casino license holders stopped working with junkets, while Macau’s gaming regulator sharply reduced the number of licensed junket operators to 46—roughly half the prior level. The direction of travel was clear: less reliance on VIP intermediaries, more pressure to reinvent Macau around leisure, entertainment, and mass-market tourism rather than cross-border capital flows.

For Galaxy, the crackdown validated a strategy that had been years in the making. Analysts at Bernstein put it plainly: Macau’s future was in mass and premium mass, and a shrinking junket business—especially one tied to overseas and illicit online gambling—was ultimately healthier for the industry’s long-term stability.

This is where Galaxy’s “World Class, Asian Heart” positioning started to look less like branding, and more like insulation. The company had built a resort designed to pull in broad-based visitation—families, groups, premium mass players, diners, shoppers, event-goers. In the post-junket world, that mix mattered. While more VIP-dependent competitors watched their legacy engine stall out, Galaxy’s model was simply better aligned with where Beijing was pushing Macau to go.

X. COVID-19: The Ultimate Stress Test (2020–2022)

If the junket crackdown tested Macau’s business model, COVID-19 tested whether the whole system could stay standing.

Macau ended 2020 with its lowest gaming revenue in 14 years. Total gaming revenue collapsed to about US$7.6 billion—down roughly 79% from 2019’s US$36.6 billion. In local terms, gross gaming revenue fell from MOP$292 billion in 2019 to around MOP$60 billion in 2020, an 80% year-on-year plunge. There was a modest rebound in 2021 to about MOP$87 billion, but that was still only around 30% of pre-pandemic levels.

Those annual totals are brutal. The month-to-month picture was even worse. In April 2020, Macau’s gross gaming revenue dropped 97% year over year—the sharpest monthly decline in the city’s history. The industry’s lost revenue over the period ran into the tens of billions of dollars, but what mattered on the ground was simpler: empty hotels, quiet casino floors, and a business built on cross-border travel suddenly cut off at the knees.

Galaxy was not immune. As the pandemic hit in the first quarter of 2020, tourist arrivals and gaming revenue cratered. Galaxy’s net revenue fell 61% year on year to HK$5.1 billion. At its two core properties, the impact was stark: revenue at Galaxy Macau fell 62%, and StarWorld fell 66%.

And the costs didn’t go away just because the customers did. Operators still had to staff properties, maintain systems, and meet regulatory requirements. Estimates at the time put Galaxy’s daily operating expenses at roughly US$2.9 million—money spent simply to keep doors open in a market where demand had evaporated.

Galaxy was burning close to US$3 million a day just to keep the lights on. Yet it didn’t respond by hollowing out the business. The company held the line on retaining employees and continued construction. That wasn’t charity; it was positioning. Macau’s government would remember which concessionaires protected local jobs and kept investing through the downturn—and that goodwill would matter when the next round of license decisions arrived.

Macau itself had the balance sheet to endure the storm. The city had built substantial fiscal and foreign reserves through decades of casino taxes, carried zero public debt, and entered the crisis with financial reserves reported at about US$72.3 billion in 2019. That public-sector strength mattered because it reduced the risk of panic policy, and it signaled that the government could support the broader economy while waiting for travel to restart.

In a strange way, the city’s resilience mirrored Galaxy’s. Years of conservative financial management gave the company room to absorb a shock that would have wiped out a more leveraged operator. While others scrambled for emergency capital, Galaxy could afford to think a step ahead: protect the franchise, keep building, and be ready to accelerate the moment Macau reopened.

XI. The 2022 License Renewal: Securing the Next Decade

With COVID still raging and revenues near historic lows, Galaxy faced its most important corporate moment since winning the original concession: license renewal.

Macau’s gaming market was built around six operators, the so-called “big six”: Sands China, Wynn Macau, Galaxy Entertainment, MGM China, Melco Resorts, and SJM Holdings. And in 2022, the government set out to decide who would be allowed to run the city’s casinos for the next decade.

First came a stopgap. The Macau SAR Government granted a six-month extension to Galaxy’s gaming concession, with an amended contract signed to push the expiration date to December 31, 2022. It was a bridge to the real decision: the new international tender.

Seven entities competed for six concessions. In the end, Macau renewed the incumbents: Wynn Resorts (Macau) SA, MGM Grand Paradise, SA, Galaxy Casino, SA, SJM Resorts, SA, Venetian Macau, SA, and Melco Resorts (Macau), SA. The new ten-year contracts took effect on January 1, 2023, and run through December 31, 2033.

All six incumbents survived. But this wasn’t a rubber stamp. The terms signaled a clear shift in what Macau wanted its operators to be. Executives from each concessionaire were expected to publicly lay out ten-year investment plans centered on maintaining jobs, promoting tourism, and expanding entertainment and conferences—explicitly pushing the city to diversify beyond gambling. Non-gaming was no longer a nice-to-have. It was the point.

Collectively, the operators committed to invest 118.8 billion patacas under their contractual obligations, with Venetian Macau planning the largest share at 30.24 billion patacas.

For Galaxy, the renewal read like validation of the bet it had been placing for years. Under the new concession, GEG committed more than MOP$33 billion in non-gaming investment to further diversify Macau’s tourism appeal—supporting the government’s vision to develop Macau into the World Centre of Tourism and Leisure.

That commitment fit Galaxy’s existing playbook. While other operators were still working to pivot away from the old VIP-driven era, Galaxy had already been building for the broader market: entertainment, events, meetings and conventions, and resort amenities designed to bring in visitors who weren’t flying in just to gamble.

And it reinforced the company’s core positioning. GEG pointed to its track record of delivering innovative and award-winning properties and services—anchored by the same “World Class, Asian Heart” philosophy that had shaped Galaxy Macau from day one.

XII. The Road Ahead: Phase 4 and Beyond

By late 2025, Galaxy was back at a familiar place in its history: staring at another inflection point, with the confidence—and the balance sheet—to lean in. Galaxy Macau was now the engine of the company, contributing more than 80 percent of group EBITDA. That concentration is both a strength and a challenge. The next step is to make the flagship even bigger, and even harder to compete with.

That’s what Phase 4 is designed to do. The plan is massive: roughly 600,000 square meters of new development, scheduled for completion in 2027. It’s set to bring multiple high-end hotel brands that will be new to Macau, along with a major theater, extensive food and beverage, retail, non-gaming amenities, large-scale landscaping, a water resort deck—and, importantly, a casino.

Management has been explicit about the timing. CFO Ted Chan confirmed Phase 4 is expected to open in 2027, and that the development will include a casino. He also pointed to the scale of what Galaxy has already delivered on Cotai in Phase 3: three buildings anchored by the 700-room Andaz, the 450-suite Raffles, and the 40,000-square-meter Galaxy International Convention Centre.

The strategic backdrop here matters: Galaxy says it holds the largest undeveloped landbank of any concessionaire in Macau. And when the next chapter of its Cotai buildout is finished, the company expects its footprint there to double to more than 2 million square meters—enough to make the overall resorts, entertainment, and MICE precinct one of the world’s largest and most diverse integrated destinations.

While Phase 4 is the headline, there’s also a nearer-term spark. The Capella at Galaxy Macau opened in August 2025 as a 93-room luxury hotel, with plans for roughly 100 ultra-luxury sky villas and suites. It’s a signal of where Galaxy wants to sit in the market: not just bigger, but higher-end—premium mass, premium experiences, and premium pricing power.

At the same time, entertainment has shifted from “nice add-on” to core strategy. In 2024, Galaxy hosted around 460 shows and events, spanning major acts and global sports properties including Andy Lau’s World Tour, UFC, the ITTF World Cup, and the Women’s Volleyball Nations League.

That calendar kept building into 2025. Galaxy Arena was slated to host Andrea Bocelli in March and the ITTF World Cup 2025 in April. And in June, Jacky Cheung was scheduled to bring his 10th concert tour to the venue—exactly the kind of programming that fills hotel rooms, drives dining and retail, and makes Macau feel like more than a gaming trip.

All of this is happening as access to Macau gradually loosens again. In May 2024, the Central Government expanded the Individual Visit Scheme to 59 eligible cities, representing a combined population of about 500 million people. Starting in 2025, Zhuhai residents became able to apply for a one-trip-per-week visa to Macau, while Hengqin residents became eligible for multiple entries.

Then the physical infrastructure began catching up with policy. In December 2024, Macau’s light rail transit system opened a new line connecting the Hengqin port to Cotai—another small-sounding change that, over time, can meaningfully reduce friction for the exact visitors Galaxy is building for.

XIII. Leadership Transition: After Lui Che Woo

When Lui Che Woo died on November 7, 2024, it closed the book on one of the more unlikely founder arcs in modern business: a quarry operator who, in his seventies, helped build the integrated resort that defined Cotai—and in the process helped propel Macau past Las Vegas as the world’s biggest gambling market.

Galaxy announced that Lui had died in Hong Kong, calling his “vision, tremendous leadership and guidance” the foundation of the group’s development and its continued success.

By Bloomberg’s estimate, Lui’s net worth stood at about US$14.5 billion, putting him among Hong Kong’s richest people. But the more immediate question for investors and for Macau was simpler: what happens to Galaxy without Lui?

The company tried to take that off the table quickly. A new chairman would be announced “in due course,” it said, and the death would not affect the group’s operations.

On the face of it, the succession looked unusually clean. Francis Lui—Lui Che Woo’s son and Galaxy’s vice chairman—had effectively been the operating leader for years. Still, founder transitions are never just ceremonial, especially at companies where the founder’s instincts shaped everything from strategy to culture.

Lui himself seemed to have thought about continuity the way he thought about everything else: quietly, early, and with control. By 86, he had written instructions into his will aimed at ensuring his children carried forward his philanthropic vision through his various foundations. “My children are all filial,” he said. “I have already laid down my plans in my will and there’s nowhere they can escape.”

In Hong Kong, family-empire handovers often come with tabloids and courtroom filings. Stanley Ho’s succession saga played out for years in public, a slow-motion reminder that even vast fortunes can fracture families. The Lui family, at least from the outside, projected the opposite: disciplined unity. Lui kept his personal life intensely private, and there were few negative rumors or public disputes around the family.

And then there’s the legacy beyond casinos.

In 2015, Lui launched what he called a “prize for world civilization,” carrying a cash award of HK$20 million—reported to be roughly double a Nobel Prize. “To some extent, it is a bit similar to the Nobel Peace Prize but the concept of our prize is broader,” he said. The prize recognized contributions tied to sustainable development, improving human welfare, and promoting positive attitudes.

For the man who built Galaxy by thinking in decades, it was a fitting coda: a founder who didn’t just design resorts to outlast cycles, but tried to design his giving—and his values—to outlast him, too.

XIV. Bull Case, Bear Case & Investment Considerations

The Bull Case

Galaxy’s competitive position looked unusually strong heading into the next phase of Macau’s reinvention. Galaxy Macau™ continued to rack up recognition as a top-tier integrated resort, including being cited for having the most Five-Star hotels under one roof among luxury resort companies worldwide for the third consecutive year. It was also named Best Integrated Resort in Asia Pacific for consecutive years by Inside Asian Gaming.

Then there’s the balance sheet—Galaxy’s quiet superpower. As of June 2025, the company held about HK$29 billion in cash and liquid investments, and after roughly HK$3.8 billion of debt, sat on net cash of about HK$25.2 billion. In a business where policy can change quickly and demand can evaporate overnight, that kind of liquidity isn’t just comfort. It’s optionality: the ability to keep investing, keep building, and keep pivoting when others have to retrench.

The regulatory picture also felt more settled than it had in years. Gaming was still the engine, but the direction of travel was clear: Macau wanted broader tourism, and Galaxy had already built toward that. Non-gaming revenue grew 19% year on year since 2024, and management expected that momentum to continue. The big catalyst is Cotai Phase 4, which could add around US$1–1.5 billion in annual non-gaming revenue by 2027.

Finally, there’s the real estate. Galaxy holds the largest land bank among Macau concessionaires. In a market where new concessions are capped and physical space is scarce, that’s not just an asset—it’s time, flexibility, and growth capacity all wrapped into one.

The Bear Case

Macau is inseparable from China, and that cuts both ways. The same dynamic that makes it valuable—exclusive access to Chinese demand—also makes it uniquely exposed to policy risk. Beijing’s tolerance for gambling is conditional, and operators ultimately have to align with broader political and social objectives.

The VIP collapse also appears structural, not cyclical. Mass-market play has grown, but the industry still hasn’t returned to 2019 levels. That matters because it reframes expectations: the old era of seemingly endless, VIP-fueled expansion may simply be over.

Diversification comes with its own trade-offs. Entertainment, conventions, retail, and hospitality are strategically aligned with what regulators want—but they typically earn lower margins than gaming. So even if revenue grows, the mix shift could compress profitability unless Galaxy executes exceptionally well.

And Macau no longer competes only with itself. Singapore remains formidable, the Philippines and Vietnam continue to expand, and potential future markets like Japan and Thailand sit on the horizon. Macau’s proximity to Mainland China is a major advantage, but the broader regional landscape is more competitive than it was a decade ago.

Porter's Five Forces Analysis

Threat of New Entry: Extremely low. The Macau government capped concessions at six through 2033. That said, new integrated resort-style development on Hengqin or elsewhere could create indirect competition.

Supplier Power: Moderate. Much of the casino and hospitality supply chain is commoditized, but premium hotel flags like Ritz-Carlton, Raffles, and Capella have meaningful negotiating leverage.

Buyer Power: High, and rising. Mass-market visitors can choose among six operators, and many can easily visit multiple properties on a single trip. That makes differentiation—especially through non-gaming—more important.

Threat of Substitutes: Increasing. Online gaming, other regional casino hubs, and alternative entertainment options all compete for discretionary spending. The VIP segment also faced the most direct substitute of all: Beijing effectively making the recruitment of mainland gamblers illegal.

Competitive Rivalry: Intense. All six concessionaires are now investing heavily in non-gaming, creating something like an arms race in entertainment, hospitality, and events.

Hamilton Helmer's 7 Powers Framework

Scale Economies: Galaxy Macau’s integrated footprint creates scale in operations, procurement, and marketing. More guests across more venues tends to mean better unit economics.

Network Effects: Limited in core gaming, but stronger in events. Big concerts and sporting events can pull in visitors who then spill over into hotels, dining, retail, and gaming.

Switching Costs: Moderate. Loyalty programs help, but Macau is compact and visitors can easily sample multiple operators.

Counter-Positioning: Galaxy’s “World Class, Asian Heart” approach functioned as counter-positioning against American-style operators that couldn’t as credibly pivot to Asian-centric hospitality and design.

Cornered Resource: The Cotai land bank. Scarce, strategically located, and hard to replicate—especially with concessions capped.

Process Power: The K. Wah construction heritage matters here. Galaxy has deep in-house experience executing large-scale builds and expansions.

Branding: Increasingly real. Over time, Galaxy Macau has become associated with a particular flavor of Asian luxury hospitality.

Key KPIs to Monitor

For long-term investors, three metrics tell most of the story:

-

Mass Gaming Revenue Market Share: In a post-junket Macau, this is a cleaner signal of competitive strength than total gross gaming revenue.

-

Hotel Occupancy and Average Daily Rate (ADR): With more than 5,000 rooms and more coming, hotel performance is a direct read on demand for the broader resort offering.

-

Adjusted EBITDA Margin: As non-gaming grows, margins will naturally face pressure. Holding margins steady is a strong indicator that diversification is being executed well.

XV. Myth vs. Reality

Myth: Galaxy was always a gaming company

Reality: For most of its life, it wasn’t. Galaxy Entertainment Group began as K. Wah Construction Materials—a quarrying and building materials business. The pivot from rock and concrete to casinos is one of the most dramatic corporate transformations in modern Asian business. In 2005, the company disposed of its construction materials business, acquired a stake in Galaxy Casino S.A., and became the only Hong Kong-listed company to hold an operating license in Macau.

Myth: Lui Che Woo was a gaming industry veteran

Reality: Lui didn’t grow up in casinos, and he didn’t spend his career in them. Unlike Stanley Ho and Sheldon Adelson, he entered the gaming industry at 73—after decades building expertise in construction, property development, and hotels. He arrived with a builder’s instincts and a developer’s patience, not a gambler’s résumé.

Myth: Galaxy won its license purely on political connections

Reality: Politics always mattered in Macau, but it wasn’t the whole story. The partnership with Las Vegas Sands was a major advantage. Former gaming commission member Maria Nazaré Saias Portela later said that “any entities partnering with Venetian [LVS] would have a higher chance of getting the license at the time,” because LVS brought deep experience running integrated resorts on the Las Vegas Strip.

Myth: The VIP crackdown devastated Galaxy

Reality: The crackdown hurt the whole market, but it didn’t hit everyone equally. Galaxy had spent years building for mass and premium mass customers, and it had the balance sheet to absorb a shock. As Bernstein analysts put it, “For Macau, the future remains in mass and premium mass recovery.” That shift was painful for VIP-dependent operators. For Galaxy, it was closer to a forced acceleration of the direction it was already heading.

Myth: Macau gaming has returned to pre-COVID levels

Reality: The comeback has been real—but not complete. DICJ reporting showed Macau’s gross gaming revenue for full-year 2024 rose 24% year on year to 220.2 billion patacas, reaching about 78% of 2019 levels. In other words: recovery, not a return to the old peak.

XVI. Conclusion: The Legacy of Patient Capital

The story of Galaxy Entertainment Group is, at its core, a story about patience.

Lui Che Woo spent decades laying foundations—first in quarries, then in property, then in hotels—before he ever made his audacious bet on gaming. And when he finally moved, at 73, he didn’t behave like a newcomer trying to win with bravado. He brought the same discipline and long-term thinking that had made K. Wah work in industries where cycles are brutal and execution is everything.

“Don’t just think, ‘Oh, he’s got so rich!’” Lui once said in an interview. “You don’t know how many obstacles he’s had to go through.”

Those obstacles were real: wartime displacement, starting over with little, building a business in Hong Kong’s unforgiving economy, then stepping into Macau against operators with decades of casino experience. Later came the stress tests no one could model—financial crises, a pandemic that shut the border, and a regulatory crackdown that rewired the industry. Each time, Galaxy survived by doing something unsexy and rare: keeping its footing when the ground moved.

By 2024, Macau’s recovery was clearly underway. International visitor arrivals rose sharply year over year, and the operators started talking again about confidence in the longer-term outlook for the market and for their businesses.

Galaxy entered this next chapter with a set of advantages that look a lot like Lui’s life philosophy turned into corporate strategy: the largest land bank among concessionaires, one of the strongest balance sheets in the industry, and a resort model built around Asian-centric hospitality. Phase 4 is set to push Cotai even further, while entertainment, conventions, and non-gaming keep moving from “add-on” to essential.

And there’s one final irony that captures the whole arc. Lui—the man nearly always seen in a flat cap—was more passionate about golf and Chinese calligraphy than he ever was about gambling. The founder behind one of the world’s great casino empires wasn’t, by temperament, a casino guy.

Maybe that’s the point. Galaxy didn’t succeed in spite of Lui’s outsider perspective, but because of it. He saw what many longtime gaming operators missed: that Macau’s durable future wouldn’t be built only in VIP baccarat rooms, but in integrated resorts that could attract families, tourists, and business travelers—built for the mass market, with an “Asian Heart.”

The flat-cap-wearing quarry king who became a casino tycoon at 73 left behind something rarer than a winning property: a company designed to endure. Whether that legacy holds now depends on the same thing it always has—whether the next generation can match his strategic patience, and the balance sheet discipline that made the patience possible.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music