Sun Hung Kai Properties: Hong Kong's Property Empire

I. Introduction: A Skyline Built on Ambition and Controversy

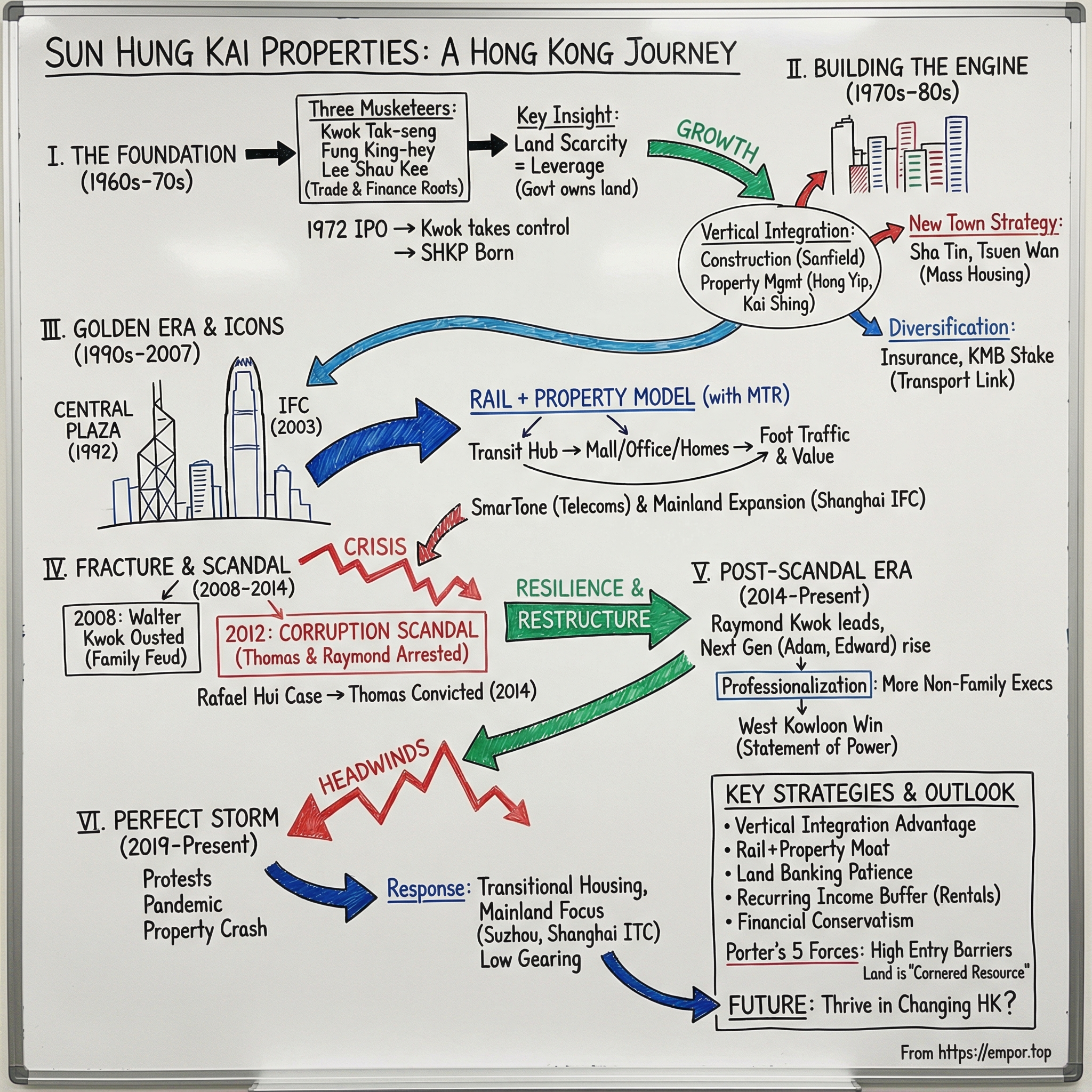

Stand along Victoria Harbour on a clear Hong Kong evening and your eyes almost can’t help themselves: they climb.

On one side, the International Finance Centre on Hong Kong Island. On the other, across the water in Kowloon, the International Commerce Centre. These aren’t just landmarks. They’re signatures—of the same controlling family, the Kwoks, and the company at the center of this story: Sun Hung Kai Properties.

The ICC, jointly developed with the MTR Corporation, is the tallest building in Hong Kong. It’s a statement in glass and steel about what SHKP became: not just a builder of housing estates, but a shaper of how the city moves, works, shops, and lives.

And yet, behind that gleaming skyline is a saga that reads like prime-time Hong Kong drama. Immigrant founders arriving from a China in upheaval. A partnership so successful it eventually seeded multiple property dynasties. A kidnapping that demanded a rumored nine-figure ransom. A family rupture fueled by internal power struggles and tabloid scandal. And then the moment the whole model was dragged into the light: a corruption case that sent one Kwok brother to prison while another walked free—exposing just how intertwined developers and government could be in a city where the government controls all land.

SHKP is a listed company and one of Hong Kong’s biggest developers, but “developer” almost undersells it. The business spans property sales and rental, telecommunications through SmarTone and SUNeVision, hotel operations, transport and logistics, and more. The Kwok family remains the controlling shareholder, and in Bloomberg’s 2025 ranking they were rated Hong Kong’s richest, with an estimated net worth of US$35.6 billion.

So here’s the deceptively simple question that powers everything that follows: how did three friends in 1960s Hong Kong build a company that helped define the city’s skyline—up to and including its tallest building—only to be rocked by a scandal that threatened the family, the firm, and the public’s faith in the system that made both so powerful?

Because this isn’t just a company story. It’s a Hong Kong story. Land scarcity as the ultimate source of leverage. Dynasty building—and what happens when a founding family splinters. The “Rail plus Property” model that turned transit infrastructure into an urban-development machine the world studied and copied. And the reality that in this market, the rules of the game start with a single, defining fact: all land is owned by the government and leased to developers, creating scarcity by design.

Understand SHKP, and you start to understand how modern Hong Kong was built—and why it has been so hard to change.

II. Hong Kong in the 1960s: The Crucible of Creation

Picture Hong Kong in the early 1960s: a British crown colony bursting at the seams. In just a couple of decades it had gone from a gritty trading port to a humming manufacturing hub, powered by wave after wave of immigrants fleeing communist rule on the mainland. The numbers tell the story: between 1945 and 1960, the population jumped from about 600,000 to more than 3 million. Homes didn’t.

The colonial government couldn’t build housing fast enough. So ordinary life became a daily improvisation—families stacked into tenements, subdivided rooms, makeshift additions. And in a city boxed in by mountains and water, every patch of buildable ground started to feel like its own currency.

Then there was the rule that quietly shaped everything: Hong Kong’s land wasn’t privately owned. It belonged to the government, which leased it out to developers through auctions and tenders. In practice, that meant supply was never just about geography. It was about timing, access, and patience. Land scarcity wasn’t merely a fact of life; it was designed into the system—and anyone who learned how to navigate it could turn square footage into leverage.

At the same time, the post-war boom was creating a new customer. Factory jobs in textiles, plastics, and electronics offered steady wages to people who’d arrived with almost nothing. A middle class began to form—and with it, a new expectation: apartments with running water, electricity, and the feeling of a future. Kowloon’s overcrowded tenements couldn’t deliver that. Developers could.

This was the crucible that would produce Hong Kong’s property dynasties: intense population pressure, constrained land supply, rising incomes, and the steadiness of British administration. For a developer with the ability to acquire land, build quickly, and sell to the mass market, the opportunity wasn’t just big. It was structural.

Years later, Sun Hung Kai’s first major multi-block residential estate, Tsuen Wan Centre, would go on sale in 1978—an early signal of the approach that would define the company: scale, speed, and housing aimed at the middle class.

And as the city kept growing, it did what Hong Kong always does when it runs out of room: it went up. Hong Kong would become famous for vertical living—more people in high floors, more tall buildings, more density than almost anywhere else. What looked like constraint from the outside became, for the right builders, the ultimate opportunity.

The stage was set for three men to turn a housing crisis into an empire.

III. The Three Founders: An Unlikely Partnership (1963-1972)

Kwok Tak-seng didn’t begin in property. He began in trade.

Born into a family from Shiqi in Zhongshan, Guangdong, he went to work young, helping his father run a small trading business. After a stint in Macau during the Second World War, he moved to Hong Kong and set up an import-export firm called Hung Cheong in Sheung Wan. And then he found his wedge into the post-war boom: he secured the Hong Kong distributorship for YKK zips.

It sounds like a footnote. It wasn’t. In the 1950s and early 1960s, Hong Kong’s garment industry was exploding, shipping clothing to markets around the world. And every factory churning out trousers and jackets needed one thing, over and over: zippers. An exclusive pipeline into that demand meant reliable cash flow—exactly the kind of steady, compounding capital that could be turned into something bigger.

In 1963, Kwok teamed up with two men who were already orbiting the same opportunity. Alongside Fung King-hey and Lee Shau Kee, he founded Sun Hung Kai Enterprises Co., Ltd., the predecessor of what would become Sun Hung Kai Properties. The trio earned the nickname “the three musketeers,” and in hindsight it fits: three very different skill sets, moving in formation.

Kwok brought an operator’s instincts from textiles and trading, and a clear read on what Hong Kong’s rising middle class actually needed: attainable homes, built fast and sold at scale. Lee was already a successful property dealer, fluent in the mechanics of real estate and finance. Fung, the financier, brought capital and the bank connections that mattered in a system where land and funding were everything. Together, they weren’t just betting on the property market—they were building a machine to navigate it.

The corporate form caught up with the ambition in 1972. Sun Hung Kai Properties Limited was incorporated on 14 July 1972 and listed on the Hong Kong Stock Exchange on 23 August 1972. By the time it went public, the group had already sold a substantial volume of properties, and the partnership was starting to change shape. That same year, the other two partners began to go their own way. Kwok acquired a controlling share and took over the company, which would be known from then on as Sun Hung Kai Properties.

What happened next reshaped Hong Kong’s business landscape. Lee Shau Kee later left to found Henderson Land in 1976—eventually becoming a billionaire rival, while still remaining connected to SHKP as a board member for years. He stepped down as chairman and managing director of Henderson Land in 2019, handing the roles to his sons, Peter and Martin. He later died at 97.

Fung King-hey would also eventually sell his stake. And confusingly, the “Sun Hung Kai” name would live on in another direction, too: Sun Hung Kai & Co. traces its roots to the same founding figures and was established in 1969, later listing in 1983. It shares the heritage—and the name—but it is a separate company, with different shareholders and management.

The origin story is classic Hong Kong: complementary partners, perfectly matched to a moment, using early cash flows from trade and finance to buy into the city’s scarcest resource—land. But it’s also a reminder of a more universal truth. Partnerships can create empires. They rarely survive them. And when the stakes become dynastic, control stops being a detail. It becomes the story.

IV. Building Hong Kong's Skyline (1972-1990)

Going public in 1972 didn’t turn Sun Hung Kai into a different company. It simply gave Kwok Tak-seng more fuel to build the version he’d been aiming at all along: not a developer that flipped buildings, but an integrated property machine that could make money before, during, and long after a project was finished.

Kwok’s insight was straightforward: if you only build, you live and die by the cycle. But if you also manage what you build, you get paid every month—boom or bust.

So SHKP started buying the “boring” parts of the business that most developers outsourced. In 1973, it acquired Hong Yip Service Company Limited. In 1978, it established Kai Shing Management Services Limited. Those two companies became SHKP’s core property-management arms in Hong Kong, taking care of the estates and towers the group developed. That meant every new project didn’t just produce a one-time sales profit; it also created a long tail of recurring management income.

Then came the product strategy—and the scale.

In 1978, SHKP launched Tsuen Wan Centre (first phase), its first multi-block residential estate. That same year, SHKP joined the Hang Seng Index as one of its 33 constituent stocks—an early marker that the market had started to see what Hong Kong would soon feel on the ground: this company wasn’t just participating in the city’s growth, it was industrializing it.

Tsuen Wan Centre captured the playbook. It was a multi-tower complex that combined thousands of homes with retail and transport links—an integrated, high-density answer to a city running out of space. In the 1970s and 1980s, SHKP would keep leaning into that formula, building large-scale, multi-block estates in the New Territories that helped power Hong Kong’s rapid urbanization.

That geography was the other big bet. While much of the industry stayed focused on the traditional urban cores of Hong Kong Island and Kowloon, Kwok was looking north. After a hotel project in Sha Tin in the 1960s, he began to see the New Territories not as “rural,” but as Hong Kong’s next chapter. During the 1970s, he started buying large tracts of land there in anticipation of urbanisation. When demand and infrastructure followed in the 1980s, that patience paid off—in projects like New Town Plaza in Sha Tin in 1984, and major residential and commercial complexes in places like Tai Po, Tsuen Wan, and Sha Tin.

This “New Town” strategy worked because it matched Hong Kong’s reality. The population kept rising, the government needed satellite cities, and land—always the limiting factor—was controlled through a system that rewarded those who could wait. SHKP had bought early, and at scale.

Kwok’s push for integration didn’t stop at management and land. In 1974, SHKP established Sanfield (Management) Limited, which became the group’s major construction project management company for its real estate development. With construction brought closer to home, SHKP could better control timelines and execution across private residential buildings, commercial office towers, and large mixed-use projects.

In 1979, it established Sun Hung Kai Properties Insurance Limited, adding another layer: insurance for buildings, construction projects, and more—business that would otherwise flow to outsiders.

And in 1981, SHKP acquired an interest in Kowloon Motor Bus. It was a telling move. Property value isn’t only about what you build; it’s about how people get there. Transportation access shapes demand, foot traffic, and ultimately pricing. A stake in a major public transport provider wasn’t just diversification—it was another way to understand, and influence, the city’s flows.

By the end of the 1980s, the picture was clear. SHKP wasn’t merely developing housing. It was assembling a system: acquire land, build, insure, manage, and connect the places it created to the rest of Hong Kong. The company was becoming less like a project-by-project builder and more like an enduring institution.

Then, in 1990, the era of the founder ended. On 30 October 1990, Kwok Tak-seng died of a heart attack. He was 79. Control passed to the next generation: his eldest son, Walter, succeeded him as chairman, and Walter—alongside his brothers Thomas and Raymond—would inherit the business their father had built.

Kwok Tak-seng left behind far more than a portfolio. He left a template his sons could extend: build for the long term, integrate the value chain, and above all, treat land not as inventory, but as destiny.

V. The Golden Era: Iconic Towers and Diversification (1990-2007)

The 1990s were when SHKP stopped being merely huge in Hong Kong and started looking inevitable.

Walter Kwok took the chairman’s seat after his father’s death, while his brothers Thomas and Raymond ran much of the day-to-day. Together they pushed the company into a new phase: landmark towers that would brand the skyline, and new businesses that could earn money even when property markets cooled.

The breakout symbol was Central Plaza.

Completed in 1992 in Wan Chai, it briefly made SHKP the builder of the tallest building in Asia. Central Plaza stood at 18 Harbour Road and rose to a pinnacle height of 373.9 meters. It was the tallest building in Hong Kong from its completion until 2003, when Two International Finance Centre overtook it. Beyond the height, the building’s angular form and its LIGHTIME lighting system turned it into a nighttime billboard for SHKP’s ambitions.

That same year, SHKP made a move that looked strange for a property developer—and turned out to be unusually sharp. It established SmarTone, stepping into mobile telecommunications just as the technology was about to explode across the region. SmarTone offered SHKP something no tower could: a technology-driven revenue stream separate from Hong Kong’s property cycle. The subsidiary was listed in Hong Kong in 1996.

But the defining play of this era wasn’t a single building or a single investment. It was a model—Rail plus Property—and SHKP mastered it.

In 1996, SHKP led a consortium that bid HK$5.5 billion for the rights to develop the International Finance Centre, with the MTR Corporation as a partner. SHKP took 47.5 per cent of the development, while Henderson Land—run by former co-founder Lee Shau Kee, who still sat on SHKP’s board—held 32.5 per cent.

Rail plus Property had started decades earlier as a way to finance MTR’s first railway line, using development rights around stations to fund construction and operations. Over time it became something bigger: an urban-development engine. Build transit, then build homes, offices, shops, and public space on top of it and around it. The railway gets riders and revenue. The developer gets world-class sites with guaranteed connectivity and foot traffic. The government gets infrastructure, economic activity, and land premiums. In Hong Kong’s land-constrained system, it was a rare alignment where everyone’s incentives pointed in the same direction.

The results were the kind of projects cities use to market themselves.

Two International Finance Centre, delivered as the second phase of the IFC development, became the tallest building in Hong Kong when it was completed in 2003, holding the title until it was surpassed by the ICC in 2009.

And the arc of the decade pointed toward an even bigger statement across the harbour. The International Commerce Centre, developed by SHKP alongside MTR, ultimately reached an official height of 484 meters, including the roof parapets. When it was completed in 2010, it ranked as the fourth tallest building in Asia and the fourth tallest in the world. From its south side, it stares straight across Victoria Harbour at the IFC—two towers in dialogue, both carrying SHKP’s fingerprints.

SHKP wasn’t only building upward. It was also getting better at reading how Hong Kong actually lived.

In 2005, it opened APM, Hong Kong’s first late-night retail centre, designed to stay open until midnight. The idea was simple: if the city worked late, shopping should too. It was a small change in hours, but a big statement about how SHKP thought—less like a landlord collecting rent, more like an operator designing for the rhythms of the customer.

Meanwhile, the company began planting a flag on the mainland. In 2003, SHKP signed a land-use transfer agreement with Shanghai Lujiazui Finance and Trade Zone Development Company for the Shanghai IFC project. It would become one of Shanghai’s premier office addresses—and SHKP’s anchor presence in China’s fastest-growing commercial hub.

Not all of the era’s projects fit the standard developer playbook. In 2009, Ma Wan Park Noah’s Ark opened as Hong Kong’s first Christian theme park. The project reflected Thomas Kwok’s Christian faith; during the 1990s, he had even set up a church in the pyramid atrium on the 75th floor atop Central Plaza.

By the mid-2000s, SHKP had the kind of footprint that makes a company feel less like a firm and more like part of the city’s operating system: signature skyscrapers, a major mobile carrier, vast investment properties, and a growing presence in mainland China. To many investors, it was the bluest of blue chips—almost a proxy for Hong Kong itself.

But family businesses have their own weather. And under all that glass and granite, pressure was building inside the Kwok dynasty that would soon break into public view.

VI. Inflection Point #1: The Walter Kwok Ouster (2008)

To understand the family rupture of 2008, you have to go back to a week in September 1997 that never really ended for Walter Kwok.

On 30 September 1997, Walter—then chairman of Sun Hung Kai Properties—was kidnapped by Cheung Tze-keung, the notorious gangster known as “Big Spender.” He was held for seven days and released without police intervention. Negotiations were fronted by Walter’s wife, Wendy, and the ransom was widely reported to be a nine-figure sum.

Cheung wasn’t a one-off kidnapper. The year before, on 23 May 1996, he abducted Victor Li Tzar-kuoi, the son of Li Ka-shing. Reports later claimed Cheung extracted HK$1.038 billion from Li Ka-shing’s family and HK$600 million for Walter.

Accounts of Walter’s captivity were brutal: beaten, stripped to his underwear, and held for a week in a wooden box. There were also reports that the family’s matriarch, Kwong Siu-hing, met Cheung privately in a luxury Central apartment while her eldest son was still being held in a village house in the New Territories. However the negotiations happened, the outcome was the same: the biggest ransom Hong Kong had ever seen, and a trauma that followed Walter home.

Cheung didn’t get to enjoy the money for long. He was later sentenced to death by a court in Guangzhou and executed by firing squad on 5 December 1998.

Walter would later say he suffered depression and post-traumatic stress disorder after the kidnapping. Over time, his brothers increasingly took on the company’s day-to-day operations. And then, in 2008, the private strain inside Hong Kong’s most powerful property family burst into public view.

On 18 February 2008, SHKP announced that Walter would take a “temporary leave of absence for personal reasons with immediate effect.” Walter described it as a “personal holiday,” with his duties handed to his two younger brothers.

The press saw something sharper. The Standard reported that Walter had been removed by his mother—still the controlling shareholder—to protect the family’s interests. The paper also reported that Walter’s mistress of four years had become increasingly influential in the business, deepening friction with his brothers. Under Walter’s later chairmanship, press reports similarly described a former girlfriend, Ida Tong, as increasingly influential in decision-making—an influence that was said to push SHKP away from its traditionally conservative approach, and toward decisions made without brotherly consensus.

The conflict quickly turned legal. On 16 May 2008, Walter filed a writ in the High Court claiming he had reached an agreement with his mother and two brothers in February: if certain conditions were met, he would return to his duties. Walter alleged his brothers violated that agreement even after he fulfilled the criteria, including obtaining at least two medical opinions stating he was fit to return.

His brothers fought back hard. In court filings, they asserted Walter had bipolar affective disorder and argued the condition should disqualify him from running the conglomerate.

Less than two weeks later, the boardroom door closed for good. On 27 May, Walter was formally removed as chairman, and Kwong Siu-hing—then nearly 80—stepped in as chairperson, effectively buying time while her younger sons consolidated control.

Walter went on to start over outside the empire. In 2010, he founded Empire Group Holdings.

For SHKP, the ouster wasn’t just family drama. It was a governance crisis and a warning sign. The spectacle of billionaire brothers fighting in court raised uncomfortable questions about leadership, stability, and what actually governed the company: professional management, or personal relationships inside a controlling family trust.

And in hindsight, the rupture carried a darker implication. For years, Hong Kong has speculated about whether the bitterness of Walter’s removal helped set the stage for what came next. Walter wasn’t arrested in the corruption case that would later engulf his brothers. But it has been suggested he provided information to the authorities in retaliation.

At the time, it sounded like tabloid fuel.

Four years later, it wouldn’t.

VII. Inflection Point #2: The Corruption Scandal (2012-2014)

For SHKP, the family fight of 2008 was ugly. But what happened in March 2012 was existential.

On 29 March 2012, Hong Kong’s Independent Commission Against Corruption moved on the company at the very top. Co-chairmen Thomas and Raymond Kwok were arrested. So was Rafael Hui—until then, one of the most recognizable names in government, a former chief secretary and effectively Hong Kong’s No. 2 official. The market reacted instantly. SHKP’s shares fell hard, wiping out billions in value in a single day.

The ICAC called it the biggest case it had launched since the agency was founded in 1974. And the reason was simple: this wasn’t about a petty backroom favor. It was about the alleged wiring between Hong Kong’s two most powerful systems—property and government—in a city where the government controls all land and developers live or die by access, timing, and policy.

The net widened beyond the brothers. An executive director at SHKP and a former senior executive at the Hong Kong Stock Exchange were also charged, along with others connected to the case. Hui’s career path only sharpened the public discomfort: he had served as a consultant to SHKP before entering government, and he had later worked as a special adviser to Sun Hung Kai after leaving office. That revolving door raised the central question at the heart of the scandal: were the payments to Hui legitimate consulting arrangements—or were they bribes dressed up as “fees,” “loans,” and corporate formalities?

Prosecutors alleged that between 2005 and 2007, Hui received millions from figures tied to SHKP, and that the purpose was influence—access to inside information, favorable treatment, and a clearer view into how land policy and land sales might unfold. In a market where land is the prize and the government is the seller, even the suspicion of that kind of advantage was combustible.

And it landed at a moment when Hong Kong was already on edge. Property prices had pushed home ownership out of reach for huge swaths of the middle class. The rich-poor gap was widening. Tycoons who had once been treated as near-untouchable pillars of the economy were now viewed with growing mistrust. To many residents, this case wasn’t just about whether a few men broke rules—it looked like evidence of a system designed to keep ordinary people out.

The trial that followed lasted more than 100 days. In December 2014, the verdict arrived: Thomas Kwok was convicted of conspiracy to commit misconduct in public office, while Raymond Kwok was cleared of all charges. Thomas received a five-year prison sentence and a HK$500,000 fine. Rafael Hui, SHKP executive Thomas Chan, and businessman Francis Kwan were also jailed.

Thomas resigned his roles at the company and appealed. The appeals were ultimately dismissed, and in June 2017 he was returned to prison. In March 2018, the Hong Kong government revoked the Silver Bauhinia Star it had awarded him in 2007.

For the Kwok family, it was a public humiliation—an open crack in an image they had spent decades curating: discreet, respectable, in control. But for SHKP as a business, the shock revealed something else: the empire didn’t crumble. SHKP said its day-to-day operations were not affected and would not be affected by the leadership changes.

That resilience was the real twist. In Hong Kong property, reputation matters—but so do land, assets, execution, and recurring income. The scandal damaged the family brand and forced questions about governance. Yet the machine the founders built, and the city SHKP helped shape, kept running.

And from that point on, the story of SHKP shifted. It was no longer just about building the skyline. It was about whether the company—and the family behind it—could rebuild trust, tighten control, and prove that the next era would be run differently than the last.

VIII. Post-Scandal Restructuring and the Raymond Era (2014-Present)

After Thomas Kwok’s conviction, SHKP faced a problem bigger than any one trial: how does a family-controlled empire convince investors, regulators, and the public that it can be run like a modern institution?

The answer was to make the company look, and operate, less like “two co-chairmen at the top” and more like a professionalized organization. In July 2012—while the investigation was still unfolding—SHKP expanded its executive committee from seven to 12 members, and every new seat went to a non-family executive. The company told the Financial Times that two of those executives were promoted into newly created roles as joint deputy managing directors, specifically to help Thomas and Raymond Kwok “discharge their duties.” As Ben Kwong of KGI Asia put it to the FT at the time, “The company is trying to dilute the importance of the two co-chairmen.”

At the same time, SHKP began quietly laying the next set of tracks for succession. The FT reported that Thomas’s son, Adam, and Raymond’s son, Edward, were named as alternate directors to their fathers. Kwong’s read was blunt: they were too inexperienced to run anything immediately, but the long-term plan was obvious—eventually, the next generation would take over.

When the verdict came down, Thomas resigned as chairman and managing director and was disqualified from serving as a director for five years. In the reshuffling that followed, his son Adam—then 31—was appointed an executive director.

For a company that had always been defined by family control, these changes were a real evolution. Expanding the executive committee and elevating non-family professionals wasn’t just optics; it was SHKP signaling that it was building more internal checks and balances than it had in the past.

And yet the core reality didn’t change. As of July 2025, the Kwok family remained the controlling shareholder, keeping a stake of more than 40% through a family trust. Other reporting has described Kwok Tak-seng’s heirs as controlling 28% through trusts created by his widow, Kwong Siu-hing. Either way, the message was the same: SHKP could professionalize around the edges, but the center of gravity was still the family.

One lingering thread of the dynasty story closed in 2018. Walter Kwok died on 20 October 2018 at age 68, after suffering a stroke in August and spending nearly two months in Hong Kong Adventist Hospital. In the days before he died, his younger brothers—including Thomas—visited him. Walter’s wife said the family was by his bedside when he passed away peacefully on a Saturday morning.

Then, in another turn that would have been hard to imagine during the darkest days of the scandal, Thomas began to re-enter the orbit of the empire after serving his sentence. He was appointed a senior director at Sun Hung Kai Real Estate Agency, a unit of SHKP. The company said he would focus on long-term strategy in land planning and project development, and would not be involved in daily operations.

Whatever was happening inside the family, SHKP’s external posture remained clear: keep building. In 2019, the company won the tender for the commercial site atop the West Kowloon High-Speed Rail Terminus—widely described as the biggest parcel of commercial land ever sold in the city. SHKP’s bid of HK$42.23 billion secured a roughly 60,000 square metre site intended for office, shopping, and hotel development. Reporting also noted that the Kwok family invested HK$9.4 billion for a 25% stake in the office towers.

West Kowloon was more than a trophy purchase. It was SHKP reminding the market that even after the arrests, the trial, the conviction, and the family turmoil, the fundamentals of its power hadn’t disappeared: access to capital, the patience to take on landmark sites, and the ability to place huge bets on where Hong Kong was headed next.

IX. Perfect Storm: Protests, Pandemic & Property Crash (2019-Present)

West Kowloon was supposed to be a statement about the future. Instead, it became the opening scene of a rough new chapter for Hong Kong property—and for the company most associated with the old one.

From 2019 onward, the hits didn’t come one at a time. They stacked. The protests shook confidence and disrupted daily commerce. Then COVID-19 froze travel, emptied offices, and rewired retail. Interest rates surged, making mortgages and developer financing more expensive. And on the other side of the border, mainland China’s property slump crushed sentiment across the region. Together, it was a stress test of the entire Hong Kong property model that had made SHKP’s fortune.

By the mid-2020s, the downturn had lasted close to five years—often described as the longest retreat since the SARS era more than two decades earlier. Bloomberg Intelligence estimated that since 2019, at least HK$2.1 trillion (US$270 billion) had been wiped from the city’s real estate values. In a market built on the belief that land only goes one direction, that kind of number doesn’t just describe losses. It describes a shift in psychology.

SHKP’s response wasn’t only financial. During the social pressure of the 2019 protests, it took a step that would have been hard to imagine in its earlier, more insulated era: it offered up parts of its land bank for transitional housing. The company proposed making land available for about 2,000 homes to help ease the city’s housing crunch. Executive director Adam Kwok said SHKP volunteered three sites totaling roughly 400,000 square feet. The largest—a roughly 300,000 square foot lot about a ten-minute walk from Yuen Long MTR station—was to be handed over for HK$1 for eight years to an NGO, Hong Kong Sheng Kung Hui, which would develop transitional housing for occupancy.

That partnership expanded into a concrete project. The Hong Kong Sheng Kung Hui Welfare Council and SHKP collaborated on the “United Court” Transitional Housing Project in Tung Tau, Yuen Long, supported by government funding. The project provides 1,800 units aimed at improving living conditions for grassroots families, pairing housing with social services intended to build a more supportive community.

But goodwill couldn’t stop gravity in the market.

By early 2025, Hong Kong’s residential property price index was still falling year-on-year—thirteen consecutive quarters of declines, according to the Ratings and Valuation Department. Other reporting put the cumulative drop at close to 30% from the 2021 peak. In practical terms, that meant a city where buyers waited, sellers discounted, and “property always goes up” no longer sounded like a law of nature.

SHKP’s results showed the same split the company had spent decades engineering. For the year ended 30 June 2025, underlying profit was broadly flat year-on-year, and the company recorded a net decrease in the fair value of its investment properties. The more important story was where the earnings came from: property development contributed HK$8,290 million, while property rental contributed HK$18,392 million. In a period when home sales were under pressure, recurring rental income wasn’t a nice-to-have. It was the stabilizer.

Even so, the headwinds were everywhere you’d expect in a stressed property system. There were signs of policy and market support—lower HIBOR, rising stock prices, and reduced stamp duty for certain mid-priced homes helped sentiment at the margin. But they collided with a harsher reality: geopolitical uncertainty, negative equity levels reported to be the highest in 22 years, deep developer discounts, and growing fears around commercial real estate.

The office market was particularly bruised. Capital values of Grade A offices had fallen nearly half from their late-2018 peak. And with more supply coming and demand still soft, forecasts pointed to rents declining further in 2025, with landlords forced to offer incentives just to hold occupancy.

In that environment, the government began pulling levers more aggressively. On 28 February 2024, it announced that all three stamp duties would be scrapped in an effort to support a recovery. Later, in October 2024, Hong Kong Free Press reported that mortgage loan-to-value limits would be relaxed: the maximum would be set at 70% regardless of property value, occupancy intentions, or whether the buyer was a first-time purchaser.

None of that guaranteed a rebound. But it did signal something important: when Hong Kong property is under real stress, the response isn’t just market-driven. It becomes a city-level priority. And for SHKP—so intertwined with Hong Kong’s built environment—that meant the next era wouldn’t be defined only by what it could build, but by how it could endure.

X. Mainland China Strategy: The Diversification Play

As Hong Kong’s property market stalled, SHKP’s mainland China business started to matter in a different way. Not as a replacement for Hong Kong—nothing really replaces Hong Kong for SHKP—but as a second engine with its own demand drivers and its own timetable.

The near-term signal was Suzhou. On the mainland, the detached houses in Phase 2 of the joint-venture project Lake Genève in Suzhou recorded an encouraging sales response. By the end of June, SHKP said its contracted sales on the mainland that had not yet been recognized totaled about RMB8.1 billion, with most of that expected to flow through in the 2025/26 financial year.

Momentum continued into 2025. In January, SHKP launched the first batch of the second phase of Lake Genève and again reported an encouraging response. Over the following 10 months, the group planned to roll out additional batches across joint-venture developments including Lake Genève in Suzhou, Hangzhou IFC, and Oriental Bund in Foshan.

What’s striking is how different SHKP’s approach is from the playbook that blew up so many mainland developers. Rather than chasing volume with heavy leverage, SHKP has leaned into premium projects in stronger markets—places like Shanghai, Hangzhou, and Suzhou—where demand tends to be more resilient and higher price points can support higher build quality.

On the investment-property side, the message is equally consistent: operate, curate, and protect the asset. SHKP said it took proactive steps to optimize mall services and tenant mix, lifting footfall and consumption and helping major malls maintain high occupancy. Its office portfolio, meanwhile, benefits from the same integrated-complex logic SHKP perfected in Hong Kong: strong building standards, accessibility, professional management, and the spillover advantages of having malls and hotels in the same ecosystem.

That ecosystem in Shanghai is still being built out. The remaining portion of Three ITC—including office Tower B, the flagship mall ITC Maison, and Andaz Shanghai ITC—is scheduled to complete in phases starting in the second half of 2025.

This mainland footprint is anchored by a huge long-term bet. In 2013, SHKP acquired a commercial site in Shanghai’s Xujiahui district with 7.6 million square feet of gross floor area. The Shanghai Xujiahui project is one of SHKP’s largest mainland investments: a sprawling, integrated development that will take years to finish, but places the company in one of China’s premier commercial districts.

And then there’s the balance sheet—where SHKP’s strategy becomes clearest. While distressed mainland developers like Evergrande and Country Garden defaulted and scrambled to sell assets, SHKP kept leverage low. Its gearing ratio was 17.8% as of December 31, 2024, and had improved to 15.1% by June 30, 2025.

That isn’t an accident. It’s a choice. The Kwok family has long favored financial conservatism over aggressive expansion. In a cycle where debt-heavy competitors collapsed, that conservatism didn’t just look cautious. It looked like survival strategy.

XI. Playbook: Business & Strategic Lessons

Sun Hung Kai Properties’ six-decade run is, in many ways, a case study in how you build a durable advantage in a business as cyclical and capital-intensive as real estate. The themes repeat—across booms, busts, scandals, and leadership changes—and together they explain how SHKP kept compounding when others couldn’t.

The Vertical Integration Advantage: SHKP didn’t just develop buildings. It built an ecosystem that captures value before, during, and long after construction is finished—construction project management through Sanfield, property management through Hong Yip and Kai Shing, parking through Wilson, telecoms through SmarTone, and even a strategic foothold in transport through its stake in Kowloon Motor Bus. Sanfield (Management) Limited, founded in 1974 and based at Sun Hung Kai Centre, became the group’s core construction project manager, overseeing the delivery of SHKP’s residential projects, office towers, and large mixed-use developments. That integration improved control over timelines and quality—and reduced reliance on outsiders at the most critical moments.

The Rail+Property Model: The MTR partnership unlocked something competitors can’t easily copy: premium, transit-anchored sites with built-in foot traffic, connectivity, and long-term relevance. Over time, the R+P model proved its financial logic. The government didn’t have to shoulder railway construction risk the same way it would under a fully public works model; instead, it collected land premiums and benefited as a shareholder—through its roughly 76% stake in MTR and dividends such as the $590 million paid in the 2014 financial year. And because MTR didn’t have to fight for public funding in the same way, projects could move faster. SHKP’s edge was knowing how to turn that infrastructure spine into destinations: offices, malls, homes, and hotels that felt inevitable once they were built.

Land Banking as a Core Competency: In Hong Kong, the most valuable “skill” isn’t design—it’s patience. SHKP repeatedly showed a willingness to buy land well before it was fashionable, then wait for infrastructure and demand to catch up. Kwok Tak-seng’s New Territories land purchases in the 1970s became the archetype: accumulate when others hesitate, and you don’t just earn returns—you earn options.

Recurring Income as a Buffer: SHKP engineered stability into a volatile business by building a large rental portfolio. In FY2025, property rental brought in HK$18,392 million, compared with HK$8,290 million from property development. That mix matters. Offices, malls, and other investment properties don’t eliminate cycle risk, but they soften it—giving SHKP the ability to endure downturns without becoming a forced seller, and to keep investing when competitors are scrambling for liquidity.

Financial Conservatism: SHKP’s long-term posture has been simple: stay prudent, keep gearing low, and rely on a diversified investment portfolio and sizeable recurring income to avoid being trapped by the cycle. Even while staying confident in Hong Kong and the mainland over the long run, the company framed its approach as steady rather than aggressive—built to last, not just to win the next upturn.

The Family Control Trade-off: Family control let SHKP plan in decades, not quarters—and that long horizon is part of why it could assemble land banks, build integrated mega-projects, and patiently grow a rental base. But the downside is real: when family dynamics go wrong, governance can become personal, and personal problems can become corporate crises. The Walter Kwok ouster and the corruption scandal exposed those risks. The post-scandal shift toward a larger, more professional executive bench was an attempt to keep the benefits of family stewardship while putting guardrails around its worst impulses.

XII. Analysis: Competitive Positioning and Future Outlook

Porter's Five Forces Assessment

Threat of New Entrants: LOW. In Hong Kong, “starting a new developer” isn’t like starting a new software company. The government owns all land, releases it on its own schedule, and sells it through auctions and tenders that demand serious capital. Just as importantly, the relationships that matter—especially with the MTR and government bodies—are built over decades. Layer on SHKP’s vertical integration, from construction project management to property management, and you’re looking at an incumbent advantage that’s extremely hard to recreate from scratch.

Supplier Power: LOW-MODERATE. Construction materials and labor are broadly commoditized, which keeps supplier power in check. SHKP also buffers itself by relying on its own Sanfield subsidiary for construction project management, reducing dependence on external contractors. And scale matters: when you build as much as SHKP does, you generally negotiate from a position of strength.

Buyer Power: MODERATE. For individual homebuyers, bargaining power is limited in a city defined by chronic housing pressure. But on the commercial side, the balance can shift. In an office market facing oversupply, large corporate tenants—especially multinationals—can negotiate hard on rents, incentives, and lease terms.

Substitute Threats: LOW. There’s no true substitute for land in Hong Kong. The city’s physical constraints are real, and its role as a gateway between mainland China and global capital has historically created demand that doesn’t simply “move” elsewhere overnight.

Competitive Rivalry: MODERATE. SHKP operates in an oligopoly alongside other heavyweight developers like Henderson Land, New World Development, and Cheung Kong. Competition is intense, but it’s rarely suicidal. The big players tend to have different strengths and land positions, and they’re all disciplined by the same reality: the land system rewards patience, not price wars.

Hamilton's 7 Powers Framework

Scale Economies: SHKP’s scale lets it play a different game—one where it can finance, build, and hold projects that would overwhelm smaller competitors. The West Kowloon site win is a reminder: not many companies can make that kind of commitment.

Network Effects: There aren’t classic network effects here in the social-media sense. But there is a softer version: an ecosystem of malls, offices, and residential properties that can reinforce each other through foot traffic, tenant demand, and destination value.

Counter-Positioning: SHKP’s integrated model is hard to match if you’re a pure-play developer. To copy it, competitors would have to rethink what they outsource, how they finance, and how they manage assets after completion—changes that can clash with their existing operating models.

Switching Costs: Moderate. For tenants, moving is expensive and disruptive, and lease structures add friction. That doesn’t make switching impossible, but it does give landlords with strong assets some staying power.

Branding: In Hong Kong, SHKP is one of the best-known names in property. The brand is meaningful locally, even if it’s less distinctive outside the city.

Cornered Resource: Land is the ultimate cornered resource in Hong Kong—and SHKP’s land bank, accumulated over decades, is a competitive asset that rivals can’t simply buy their way into quickly.

Process Power: SHKP’s learned capabilities—especially around transit-linked, mixed-use mega-projects and the execution required to deliver them—are not a set of documents you can download. They’re institutional know-how, built project by project, relationship by relationship.

Key Performance Indicators for Monitoring

For anyone trying to understand how SHKP is really doing, three indicators tend to tell the story faster than headlines:

-

Rental Income Growth: Recurring rental income is the stabilizer in a cyclical business. Watch occupancy and rent trends across offices and retail, as well as tenant retention.

-

Net Gearing Ratio: SHKP’s conservatism has been a competitive advantage. If leverage rises meaningfully, the obvious question is why—and whether the company is drifting from its long-held discipline.

-

Contracted Sales Recognition: The difference between contracted sales and recognized revenue offers a window into future earnings. Changes in timing—accelerations or delays—often signal how smooth (or strained) the development engine really is.

Risk Factors

Even an empire built on scarcity and patience has real risks:

Political Risk: Hong Kong’s evolving relationship with mainland China can affect demand through corporate decisions, emigration patterns, and policy shifts.

Interest Rate Sensitivity: SHKP may run a conservative balance sheet, but the broader Hong Kong property market is sensitive to rates, especially under the linked exchange rate system.

Mainland China Exposure: SHKP has been more conservative than many mainland peers, but China’s property sector remains fragile and can produce surprises.

Family Governance: The Kwok family controls more than 40% through trusts. Succession, health issues, or renewed family conflict can create uncertainty—even if day-to-day operations are professionalized.

Regulatory Changes: Public pressure can reshape policy. If Hong Kong’s government shifts toward constraints on land strategy or pricing power, developers’ economics can change quickly.

Sun Hung Kai Properties’ story is, in a very real way, Hong Kong’s story: immigrants who arrived with little, built a fortune by mastering the city’s scarcest resource, and helped define the physical shape of a global financial center.

The milestones read like a timeline of the city’s rise. Kwok Tak-seng building early capital through trade. SHKP industrializing mass-market housing. Then the era of skyline statements—Central Plaza, IFC, and later the ICC. And woven through it, the darker thread: a kidnapping, a public family rupture, and a corruption case that cracked open the relationship between tycoon power and government power.

Now the company is navigating a tougher environment. The market has been in a multi-year downturn, offices are under pressure, and sentiment is no longer buoyed by the old assumption that property prices only move in one direction. But SHKP also has what many competitors lack: diversified earnings, a deep asset base, and the kind of institutional experience that helps companies outlast cycles.

Bloomberg captured the family’s reputation with a line that fits their history: the Kwoks have a record of defying skeptics. During the long property bear market from 1998 to 2003—when the Asian financial crisis and SARS hit Hong Kong hard—they leaned in and invested heavily, including in projects that would later become some of the city’s defining towers.

Whether today’s leadership can recreate that kind of countercyclical success is the question that hangs over the next chapter: Raymond at the helm, Thomas back in the orbit after prison, and the next generation—Adam and Edward—taking on greater responsibility.

They’ve already proved the empire can survive kidnapping, scandal, and market shocks.

What they haven’t proved yet is whether it can thrive in a Hong Kong that’s changing underneath it.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music