Samsung Fire & Marine Insurance: From War-Torn Busan to Lloyd's of London

I. Introduction and Episode Roadmap

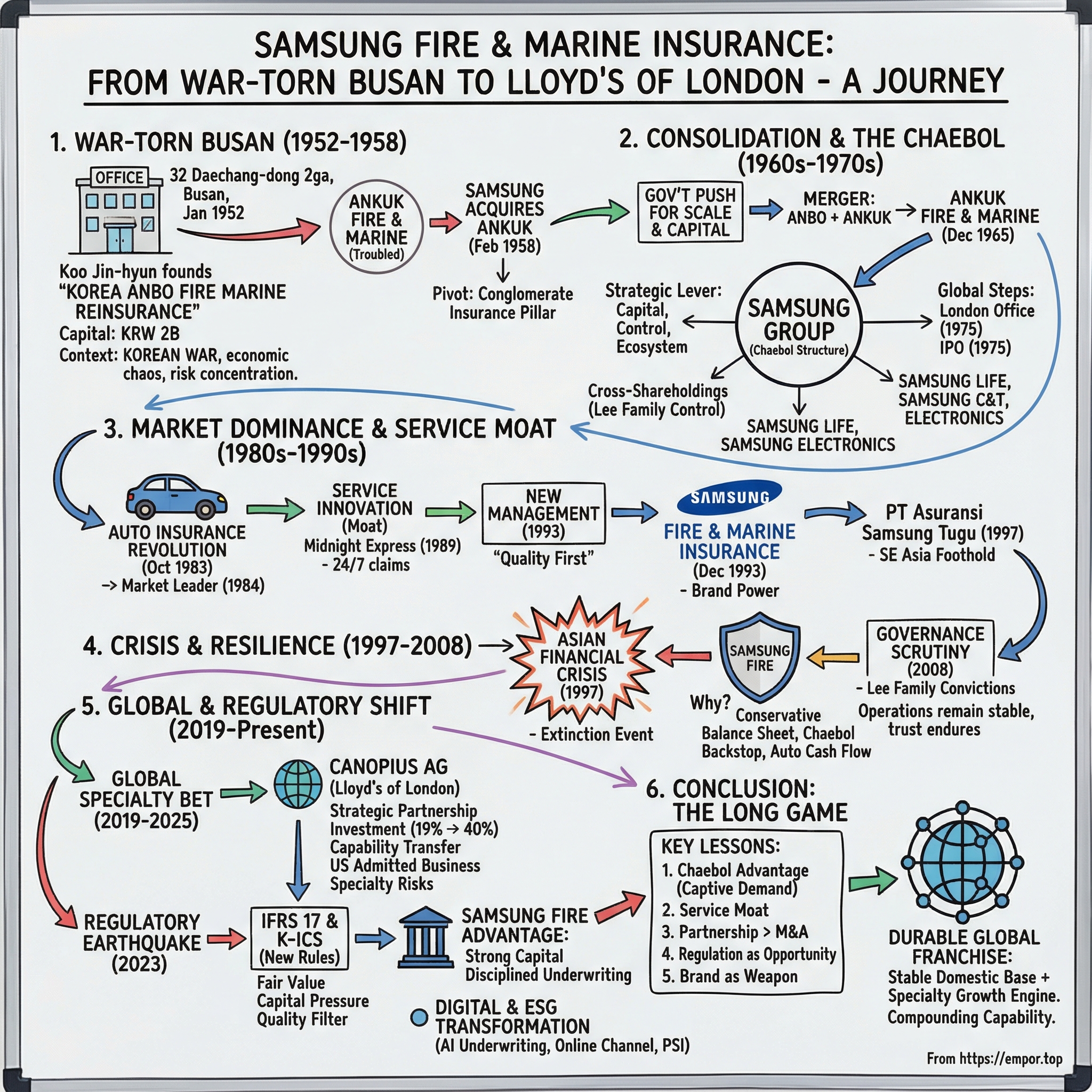

Picture this: January 1952. The Korean Peninsula is at war. The South Korean government is running the country from Busan, the southeastern port city that’s become a last refuge behind the Pusan Perimeter. Half a million people have poured in. Seoul is shattered. The economy is barely hanging on. And even in Busan, where the city has avoided the worst of the direct fighting, the sound of artillery is never far away.

In a small office at 32 Daechang-dong 2ga, a man named Koo Jin-hyun makes a bet that feels almost absurd for the moment: he decides to start an insurance company.

Koo had been struggling to manage an education group called Hunsesa after Korea’s agrarian reform beginning in 1950. So he chose a different path, committing capital of KRW 2 billion to build something new. On January 26, 1952, he convened an inaugural meeting in that Busan office and officially launched Korea Anbo Fire & Marine Reinsurance.

So here’s the question that pulls us through the next seven decades: how does an insurance company born in a wartime port city end up as a critical piece of Asia’s largest chaebol—and, eventually, a player in the world’s most storied insurance marketplace, Lloyd’s of London?

Today, Samsung Fire & Marine Insurance Co., Ltd., together with its subsidiaries, provides non-life insurance products and services across South Korea, China, Indonesia, Vietnam, Singapore, the United States, and the United Kingdom. Its lineup spans automobile insurance, long-term damage insurance, personal pensions, retirement pensions, and general coverage that can stretch from marine cargo to technology liability.

But the metrics are just the surface layer. Samsung Fire is the market leader in South Korea’s non-life sector, with roughly 22% market share by gross insurance service revenue in 2024. And it carries something most insurers can’t buy: the halo—and the strategic usefulness—of being part of the wider Samsung Group. That brand credibility shows up in places you can actually measure, too: Samsung Fire & Marine Insurance ranked #11 on Newsweek’s World’s Most Trustworthy Companies 2024 list in the Insurance category.

This is a story about how insurance—maybe the least glamorous corner of finance—turns into leverage. How cross-shareholding structures can create control without obvious ownership. How a company balances a saturated home market against the scale and profit pools of global specialty insurance. And how regulatory earthquakes can crush the undercapitalized while rewarding the disciplined.

Here’s the roadmap: we’ll start with the chaebol context that makes Samsung fundamentally different from Western conglomerates. Then we’ll go back to the founding in wartime Busan, track the consolidation that built scale, and hit the service innovations that created real moats. From there, we’ll move through the industry’s biggest inflection points—especially regulation—and end at the Canopius bet: Samsung Fire’s most ambitious global play yet.

II. The Chaebol Context: Understanding Samsung Group

Before we dive back into Samsung Fire’s own origin story, we need to understand the machine it ultimately plugs into. Because in Korea, “who owns what” isn’t a footnote. It’s the plot.

Samsung Group is a South Korean multinational conglomerate headquartered in Seoul, anchored in the Samsung Town office complex. It’s the country’s largest chaebol: a cluster of affiliated companies that mostly share the same brand, but operate across wildly different industries.

Even the word chaebol tells you what you’re dealing with. It combines the Korean words for “wealth” and “clan.” This is capitalism organized like a dynasty.

Samsung began in 1938, founded by Lee Byung-chul as a trading company. Over the next three decades it expanded into food processing, textiles, insurance, securities, and retail. Then came the big step-change: electronics in the late 1960s, followed by construction and shipbuilding in the mid-1970s—industries that would become the engines of Samsung’s global rise.

And here’s the strategic insight that matters for our story: inside a chaebol, insurance isn’t just insurance. It’s a tool for capital formation, corporate control, and ecosystem lock-in.

Today, Samsung Group includes dozens of affiliated companies. Samsung Electronics is the crown jewel. Around it sit major affiliates like Samsung Life Insurance, Samsung C&T (construction and trading), Samsung SDS (IT services), and Samsung Biologics. These companies are connected through cross-shareholdings—interlocking ownership stakes that, together, keep control concentrated with the founding Lee family.

This cross-shareholding web is complicated on purpose. The group’s executive chairman, Lee Jae-yong (known globally as Jay Y. Lee), sits at the top of an architecture where influence is amplified through layers. Samsung C&T functions as the de facto control tower, and Lee’s stake there—combined with Samsung C&T’s stakes across the rest of the group—strengthens control far beyond what any single direct holding would suggest.

Two affiliates in particular matter: Samsung Life Insurance and Samsung C&T both hold meaningful stakes in Samsung Electronics. Stack those layers and you get classic chaebol engineering—control reinforced not by one big ownership block, but by a network.

So why does this matter for Samsung Fire? Because in this structure, insurance companies aren’t just profit centers. They’re strategic levers. They generate stable float that can be invested. They can insure Samsung affiliates around the world. They can serve as talent pipelines for executives moving through the group. And, critically, they can sit inside the ownership and governance ecosystem in ways that help reinforce family control.

If you want a sense of Samsung’s scale, consider this: what started as a business trading dried fish, noodles, and other domestic goods is now so large that Samsung Group accounts for roughly 20% of South Korea’s GDP. That’s not a metaphor. It’s the kind of economic gravity that bends a country’s institutions around it.

Which brings us to the second piece of context: the long-running, deeply intertwined relationship between the chaebols and the South Korean government. Since the early 1960s, the government backed Samsung and its peers as part of a national export-driven growth push. Preferential financing, protective regulation, and major contracts helped build industrial champions; in return, the chaebols delivered jobs, exports, and rapid development.

That symbiosis created enormous advantages—and lasting complications. The same structures that made chaebols powerful also made them politically controversial. And insurance, in particular, has repeatedly ended up in the regulatory crosshairs, as reforms have tried to curb the most aggressive forms of cross-shareholding and affiliate entanglement.

With that in mind, Samsung Fire’s domestic leadership isn’t just a market-share statistic. It signals something more durable: embedded relationships with Samsung affiliates, access to large corporate insurance programs, and distribution strength that can cross-sell inside the Samsung ecosystem. The chaebol structure is a competitive advantage—and, increasingly, a regulatory target.

III. Founding in the Ashes: The Korean War Era (1952-1958)

Samsung Fire’s story begins not with Samsung, but with a man trying to survive a financial shock.

Koo Jin-hyun was an educator. He’d founded an education group called Hunsesa, and for a while it worked. Then Korea’s agrarian reform beginning in 1950 upended the country’s economy—and it hit Koo hard. Managing Hunsesa became increasingly difficult, and he needed a new engine of stability. So in the middle of a war, he made a move that sounds almost counterintuitive: he decided to start an insurance company, backed by capital of KRW 2 billion.

Why insurance? Because war doesn’t just destroy—it also concentrates risk. And where risk piles up, insurance becomes infrastructure.

Busan in 1952 was a strange kind of boomtown. It was one of only two major South Korean cities not captured by the North Korean army in the first three months of the war. People, money, goods, and government all surged south. According to The Korea Times, around 500,000 refugees were in Busan in early 1951. The port was a lifeline. And lifelines need protection: warehouses, shipments, factories, and the precious cargo moving through Busan Port.

Koo spotted the gap. The industry was young, fragmented, and short on capital—exactly the kind of environment where a disciplined operator could matter.

On January 26, 1952, his company was incorporated under the name “Korea Anbo Fire Marine Reinsurance Co.”

Even the name carried a message. “Anbo” roughly translates to “security” or “peace”—an aspirational choice for a business born with artillery in the background. And the focus on fire and marine reinsurance wasn’t random. Those were the essential risks of a country trying to rebuild commerce while the war still raged.

But the next twist in this story is that the company that becomes Samsung Fire doesn’t win by outcompeting everyone else. It wins by being absorbed into something larger.

In June 1956, another player entered the picture: Ankuk Fire & Marine Insurance Co., Ltd., founded by large shareholders of Josun Life Insurance, the first insurer in Korea. Ankuk should have been well-positioned. Instead, by the late 1950s it was struggling—sluggish sales, barely keeping the lights on with incoming premiums.

At the same time, Samsung was rising fast in the Korean economy and had growing ambitions in financial services. When Ankuk’s large shareholders looked for a way out, Samsung was offered the opportunity. In February 1958, Samsung acquired the financially troubled Ankuk.

This is the real pivot point. It’s the moment the story stops being about a scrappy wartime startup and starts being about a conglomerate building an insurance pillar.

The logic was simple and very chaebol: insurance wasn’t just another business line. It was a strategic asset—steady cash flows, investable float, and a platform to serve corporate clients as Samsung expanded. And acquiring an existing insurer meant instant presence, including the regulatory permissions that would have taken far longer to secure from scratch.

You can already see a pattern forming: Samsung didn’t enter insurance by patiently building. It entered through consolidation, during a moment of distress. That instinct—move when others are weak, buy capability instead of waiting to grow it—shows up again and again later in the company’s history.

And it explains something fundamental about Samsung Fire from day one: even as it built real underwriting capability, it was never meant to be “just” an insurer. It was designed to be useful to the wider Samsung machine—financially, strategically, and operationally.

IV. The Military Era and Industry Consolidation (1960s-1970s)

The 1960s didn’t just bring economic change to South Korea. They brought a new rulebook.

After the May 16 coup in 1961, the military regime moved quickly to reshape Korean industry around a single goal: growth. Insurance, which might sound like a sideshow, was treated as part of the national infrastructure. The government pushed reforms designed to strengthen the sector, including pressure for insurers to raise capital. For the smaller, weaker non-life carriers, that pressure was fatal. For the stronger ones, it was an opportunity. The end result was consolidation—fewer companies, bigger balance sheets, and an industry built to support industrialization.

For Anbo, this was a moment of decision. The company struggled to meet the new capital expectations. In November 1962, after weighing its options, it moved in the direction the government’s policy environment rewarded: it took over Ankuk.

The corporate family tree here gets messy fast. Samsung had acquired Ankuk back in 1958. Now Anbo was taking over Ankuk in 1962. But what matters isn’t the paperwork gymnastics—it’s the direction of travel. Korea’s non-life insurance market was being compressed into a smaller number of sturdier institutions, and this business was trying to make sure it was on the surviving side of that divide.

The consolidation culminated in December 1965, when Korea Anbo Fire & Marine Reinsurance merged with Ankuk Fire & Marine Insurance. The merged company kept the Ankuk name: Ankuk Fire & Marine Insurance.

This wasn’t just routine M&A. It was government-directed rationalization. The military regime wanted insurers that could reliably underwrite the risks of a rapidly industrializing economy, and it wanted an industry with enough scale to be managed—politically and financially. The chaebols, built to execute national plans in exchange for preferential treatment, were natural consolidators.

Then, in the 1970s, the company took its first step onto the world stage—small, but symbolic. On May 25, 1975, it opened its first overseas office in London. And London wasn’t a random choice. It was the center of global specialty insurance, orbiting Lloyd’s. Even a representative office there was a statement: we’re not just a domestic insurer; we’re studying the global apex of the business.

That same year, the company also went public on the Korea Stock Exchange, listing on June 26, 1975. This wasn’t only about raising capital. It aligned with government policy aimed at pushing reforms inside the chaebols—reducing monopolization, separating capital from management, and bringing the public into corporate ownership.

By the end of the 1970s, the insurer that would eventually become Samsung Fire had already lived through a war, a coup, and a government-led restructuring of its industry. It emerged bigger, more institutionally “official,” and—thanks to London and the IPO—more outward-facing. The groundwork was in place for the next era, when scale would turn into dominance.

V. The Auto Insurance Revolution and Market Dominance (1980s-1990s)

The 1980s were the decade this company stopped feeling like a niche insurer and started looking like a consumer brand. The trigger was auto insurance.

As South Korea industrialized and incomes rose, car ownership took off. Every new Hyundai or Daewoo rolling off the line created a new, recurring need: coverage, claims, repairs, service. In October 1983, the company launched its automobile insurance products—and stepped straight into the fastest-growing pool of premiums in the country.

What happened next was a statement of intent. By 1984, it had surpassed Hankuk Motor Insurance to take the top spot in the domestic motor insurance market. In roughly a year, it went from newcomer to leader.

But leadership in auto insurance is fragile if you’re competing on price alone. Management understood that the real battleground would be service—what happens at the worst moment of a customer’s day.

So in 1989, the company built the kind of operational infrastructure that doesn’t show up in glossy ads, but wins loyalty. In January it launched a Customer Service Center to receive accident reports and coordinate help. Then, in November, it introduced Midnight Express, Korea’s first night-time motor accident claims service. Instead of forcing customers to wait for business hours, it offered help after dark—handling night-time accidents nationwide and, in Seoul, providing emergency road service for major incidents.

Midnight Express is worth pausing on because it reveals the playbook. Overnight claims operations are expensive. They’re complicated. They require staffing, dispatch, coordination with repair shops and towing, and the discipline to make it all work when things go wrong. Samsung Fire chose to eat that cost to become the insurer that actually answered the phone.

That service mindset didn’t emerge in a vacuum. In 1993, Samsung Group Chairman Lee Geon-hee launched what became known as “New Management,” pushing the entire group to shift from quantity to quality. It was a cultural reset, captured in the message he delivered to executives that year in what’s often referred to as the Frankfurt Declaration: stop chasing volume and start building world-class quality, even if it meant sacrificing sales in the short run. That quality push later helped Samsung become the world’s largest TV manufacturer, overtaking Sony by 2006.

The ripple effect hit every affiliate—including the insurance arm. In October 1993, the company declared its own “second foundation,” aligning itself with the group’s quality-first philosophy and aiming to become a top-tier global property and casualty insurer through disciplined execution and customer experience.

Then came the visible symbol of the change. In December 1993, it dropped the Ankuk name and became Samsung Fire & Marine Insurance.

This wasn’t cosmetic. Ankuk was a solid local identity. Samsung was quickly becoming a national—and then global—synonym for trust and quality. The rebrand turned an insurance company into a brand extension of the wider Samsung promise, and it gave Samsung Fire an advantage that most insurers can’t manufacture: instant credibility at the point of purchase.

The 1990s also marked the beginning of the company’s first meaningful move into Southeast Asia. In February 1997, Samsung Fire participated in a joint venture with Tugu Insurance, majority-owned by Pertamina, to establish PT Asuransi Samsung Tugu in Indonesia. It was the first time a Korean non-life insurer set up that kind of foothold in the Indonesian market, aimed at building a broader platform across the region. The venture turned a profit in its first year and was cited as a successful overseas investment.

And the timing couldn’t have been more dramatic. February 1997 was right before the Asian Financial Crisis began tearing through the region. Indonesia would be one of the hardest-hit economies. Yet Samsung Fire’s Indonesian operation survived—and that resilience would matter, because the next phase of this story is the crisis that forced Korean finance to either harden up or disappear.

VI. Inflection Point #1: The Asian Financial Crisis and Aftermath (1997-2008)

The Asian Financial Crisis of 1997–1998 was a stress test for the entire Korean financial system. For insurers, it wasn’t a bad year. It was an extinction event. And for the chaebols, it was a moment when the things that made them powerful suddenly looked like liabilities—too much debt, too many interconnected bets, and too little transparency—right as global capital stopped being patient.

Korea got hit hard. The won fell, GDP shrank, and failures started rolling through the corporate landscape. Big names—Hanbo, Sammi, Jinro, Daewoo—either collapsed outright or were forced into painful restructuring. Insurers weren’t spared. The weaker ones failed, merged under pressure, or needed the government to step in.

Samsung Fire made it through, and the reasons are revealing. Its balance sheet had been comparatively conservative, especially next to peers that chased growth with leverage. It had the advantage of being tied to a group with real cash-generation capacity—electronics, in particular—creating a kind of implicit backstop when markets were panicking. And it had a core business line that kept the engine running: a dominant position in auto insurance, which continued to produce premium inflows even as other parts of the economy froze.

By the late 1990s, Samsung Group had navigated the crisis and entered the new century still standing tall—one of the largest conglomerates in the world.

But surviving the crisis didn’t mean returning to business as usual. The aftermath came with a new rulebook, especially around governance. Korea was democratizing, standards were rising, and the cozy, opaque relationships between politics and big business were becoming harder to defend in public.

That discomfort wasn’t theoretical. Lee was convicted in 1996 for having paid bribes to President Roh Tae-woo, and later pardoned by President Kim Young-sam. Then, in 2008, the scrutiny returned in a much bigger way. On July 16, 2008, The New York Times reported that the Seoul Central District Court found Lee guilty of financial wrongdoing and tax evasion. Prosecutors sought a seven-year prison sentence and a 350 billion won fine (about US$312 million). The court ultimately imposed a 110 billion won fine (about US$98 million) and a three-year suspended sentence. On December 29, 2009, President Lee Myung-bak pardoned him.

It was messy. It was headline-grabbing. And for Samsung Fire, it was also strangely… contained.

The governance drama didn’t meaningfully change the insurer’s position in the market. While courtrooms in Seoul generated the narrative, Samsung Fire kept running its playbook: service improvements, distribution expansion, and steady execution. That gap—between the chaos at the top and the consistency on the ground—is one of the most important tells in this whole story.

Because it suggests something investors care deeply about: Samsung Fire’s value wasn’t dependent on a single figure, or even on the mood of the political cycle. The real assets were structural—the brand trust, the distribution reach, the embedded customer relationships, and the operational machine that processed claims and renewed policies day after day. Those things persisted, even when the Samsung name was taking hits in public.

VII. Inflection Point #2: The Canopius Bet and Global Specialty Strategy (2019-2025)

For decades, Samsung Fire’s overseas playbook was deliberately conservative: representative offices, joint ventures in nearby Asian markets, and plenty of business that came from serving Samsung Group affiliates operating abroad. It was steady, low-risk, and sensible.

It also had a ceiling.

The Canopius investment was Samsung Fire doing something different. Not “international presence,” but a real attempt to become a global specialty insurer—with a seat at the most important table in the industry.

In 2019, Canopius AG announced a strategic partnership with Samsung Fire & Marine Insurance. The deal would make Samsung Fire a significant minority investor, pending regulatory approvals, with closing expected in the third quarter of 2019.

To understand why this mattered, you have to understand what Lloyd’s of London is. Lloyd’s isn’t a single insurance company. It’s a marketplace—arguably the world’s most famous one for specialty insurance and reinsurance. The risks that trade there are the ones that don’t fit neatly into standard domestic markets: offshore energy, aviation, marine hull, political risk, cyber liability, and dozens of other hard-to-price lines where expertise is the product.

Canopius, founded in 2003, had grown into a major global underwriter operating in more than 130 countries, with hubs spanning Bermuda, the Netherlands, Singapore, Switzerland, the UK, and the US. In Lloyd’s terms, it was already big: the fifth-largest syndicate in the market.

Samsung Fire’s CEO at the time, Youngmoo Choi, framed the logic plainly: “We plan to work closely with the management of Canopius and share in their in-depth knowledge of the Lloyd’s market.”

And Samsung Fire didn’t stop at a single check. The initial 2019 investment was followed by additional capital in 2020, deepening the relationship. The bet wasn’t just ownership; it was capability transfer.

Then the partnership evolved from “investor” to “operator.” Canopius later announced an agreement with Samsung Fire—its substantial minority shareholder and business partner—to underwrite US admitted business on Samsung Fire’s highly rated A++ paper. As a first step, Canopius Underwriting Agency, Inc. (CUAI) would have its Ocean Marine and Management and Professional Lines teams write admitted business using Samsung Fire’s paper.

This is the kind of strategic plumbing most people never see, but it’s where the leverage lives. Canopius gained a stronger balance-sheet wrapper for certain US business. Samsung Fire gained something even harder to buy: access to Canopius’s specialty underwriting expertise and distribution relationships, in the exact markets where Samsung Fire wanted to learn, expand, and compound.

Then came the step-change. In June 2025, Samsung Fire announced a $570 million investment in Canopius Group to increase its stake from 19% to 40%. The purchase came from existing shareholders Fidentia Fortuna Holdings, led by US private equity firm Centerbridge Partners. It was described as Samsung Fire’s third investment in the group, following the earlier 2019 and 2020 tranches.

Samsung Fire CEO Munhwa (Marvin) Lee put a strategic stamp on it: “This additional investment goes beyond a financial stake — it represents a strategic milestone toward increased collaboration and shared value creation. We remain committed to expanding our overseas footprint and driving innovation to evolve into a top-tier global insurer.” Centerbridge Partners Senior Managing Directors Ben Langworthy and Matthew Kabaker pointed to Canopius’s “outstanding growth and financial performance over the last three years.”

And Canopius’s results helped explain why Samsung Fire kept leaning in. In 2023, Canopius reported profit after tax of $363 million, up from $129 million in 2022, alongside a combined ratio of 88.7%. Written premium grew to $2.8 billion that year. In 2024, Canopius reported written premium of $3.53 billion and profit after tax of $401.3 million, with Tangible Net Asset Value rising to $1.81 billion.

Samsung Fire also started to show tangible benefits from being inside the Lloyd’s ecosystem. Over roughly six years, it built experience through board-level participation, reinsurance collaboration, and personnel exchanges. By 2024, it was pointing to real outputs: co-reinsurance sales of about 300 billion won and equity-method profits of around 88 billion won.

Zooming out, Canopius was Samsung Fire’s answer to a home-market problem: South Korea’s non-life insurance industry can be profitable, but it’s mature and competitive, with limited growth runway. Overseas expansion wasn’t optional anymore—it was becoming the path to the next chapter. Industry-wide results underscored the pressure: Korean insurers collectively earned a combined profit abroad in 2024 after losses the year before, a reminder that the domestic market was no longer enough.

For investors, that’s the cleanest way to think about the strategy. Samsung Fire’s Korean business throws off stable, high-quality cash flows. The Canopius stake provides growth optionality—and a learning curve inside the world’s most sophisticated specialty insurance marketplace.

VIII. Inflection Point #3: IFRS 17, K-ICS and The Great Regulatory Shift (2023-Present)

If the Canopius investment was Samsung Fire’s offensive play—going out to learn and win in global specialty—then 2023 brought the defensive test that would decide which Korean insurers could keep playing at all.

Korea’s insurance industry didn’t get one new rule. It got two, at the same time.

Starting January 1, 2023, insurers began implementing IFRS 17, the new international accounting standard for insurance contracts. In plain terms, IFRS 17 rewrote how insurers report profits and, more importantly, how they value the promises they’ve made to policyholders. It was designed to make insurance accounting more consistent and principle-based across countries. But for companies used to the old regime, it forced fundamental changes across accounting, actuarial work, and reporting.

The big shift is that, under IFRS 17, insurance liabilities are measured using market-consistent interest rates and updated actuarial assumptions. That means earnings can swing more with markets, and it puts a bright spotlight on something insurers have always managed, but could sometimes hide: asset-liability mismatches. If what you own doesn’t behave like what you owe, you’ll feel it.

Running in parallel was the capital standard overhaul. On the same date—January 1, 2023—Korea implemented the Korean Insurance Capital Standard, or K-ICS, replacing the old RBC system. K-ICS is a full-fledged risk-based capital regime, structured similarly to the EU’s Solvency II and aligned with the IAIS Insurance Capital Standard. The goal was to push insurers toward more consistent, economically grounded decisions by forcing a fair-value view of the balance sheet.

K-ICS calculates required capital across five major buckets of risk: life/long-term insurance risk, general P&C insurance risk, market risk (including interest-rate risk), credit risk, and operational risk. And critically, it does this using market-value assets and liabilities—no more comfort from accounting that smooths away volatility.

For the weaker insurers, this wasn’t just painful. It was destabilizing.

By the regulator’s count, 19 of the 53 insurers in the market had applied for transitional measures as of end-March 2023. Those 19 included 12 life insurers, six non-life insurers, and one reinsurer. Without those transitional measures, the average K-ICS ratio at the end of the first quarter of 2023 was about 193%, but the spread was enormous—ranging from negative territory to the mid-300s. Three life insurers would have fallen below 100%, under the regulatory minimum, without relief.

This is what consolidation looks like in an industry like insurance. Not a sudden collapse, but a slow squeeze. If you have weak capital, legacy guaranteed products, or sloppy asset-liability management, you don’t get to “wait out” a new regime. You either raise capital, merge, or retreat.

In that environment, Samsung Fire sits in a very different category.

AM Best has pointed to Samsung Fire’s balance sheet strength—assessed as strongest—alongside strong operating performance, a very favourable business profile, and very strong enterprise risk management. More practically: Samsung Fire has spent decades building the kind of underwriting discipline and capital conservatism that becomes a superpower when regulators start marking everything closer to reality.

The company’s operating performance has been anchored by stable underwriting and a combined ratio that’s low compared with domestic peers, plus robust investment income supported by a large asset base. Its profitable in-force book and its ability to generate new business contractual service margin—future profit embedded in new contracts—support its leadership in long-term insurance. And its auto line has remained profitable through underwriting initiatives, favourable regulation, and cost efficiencies tied to its online channel.

Even with exposure to affiliated equity holdings, Samsung Fire has remained insulated from market shocks through low underwriting leverage and a conservative investment posture. In other words: when accounting and capital rules stop being forgiving, the companies that already behaved conservatively don’t have to change who they are.

The twist is that these reforms create two advantages at once. Defensively, Samsung Fire’s balance sheet can absorb volatility that would knock competitors off balance. Offensively, as weaker players pull back—or get absorbed—share becomes available.

There is one catch: even strong insurers have to ration capital under a tougher regime. Korea’s rated insurers have generally been expected to avoid overly aggressive shareholder payouts, at least in the near term, as they build buffers ahead of potential declines in discount rates. Samsung Fire & Marine, like most other rated insurers, has planned to increase dividends and share buybacks gradually over the mid-to-long term—but the expectation has been that it will happen slowly, not all at once.

For investors, that’s the headline: IFRS 17 and K-ICS are turning Korea’s insurance market into a quality filter. Samsung Fire’s relative strength under the new standards isn’t a one-year advantage—it’s the accumulated compound interest of decades of underwriting discipline, capital conservatism, and operational execution.

IX. The Digital and ESG Transformation

The regulatory reset was the defensive test: prove you’re well-capitalized, well-run, and not playing accounting games. Digital is the offensive push: meet customers where they actually are now, and use technology to win on speed, price, and experience.

Samsung Fire has been leaning into AI-driven underwriting to do exactly that. One example is its partnership with Cyberwrite for cyber risk modeling, which helps it price cyber insurance faster and more accurately. That matters because cyber is one of the rare insurance categories where demand is growing, the risks evolve quickly, and underwriting skill is the product.

Distribution is shifting, too. In South Korea, the traditional agency force still held a large share of the life and non-life market in 2024, but the growth is happening online. Direct and online sales are expected to keep expanding quickly through 2030, as customers get more comfortable buying coverage the same way they buy everything else: on their phones, in minutes, without an in-person meeting.

Samsung Fire entered that world early, and it shows. It still runs a large tied-agent network for long-term insurance, but in auto—where price comparisons and frictionless claims matter—it has built a market-leading online channel with a high-quality customer base. Years of operating at scale online have also created an underappreciated asset: a deep reservoir of data and operational know-how that newer competitors can’t replicate overnight.

And that’s where the advantage starts compounding. Online distribution generates cleaner, faster feedback loops: more customers creates more driving and claims data; that data sharpens underwriting; sharper underwriting supports better pricing and better loss ratios; better outcomes attract more customers. It’s not magic, but it’s a flywheel—and it’s hard to break if you didn’t start it early.

At the same time, ESG has shifted from “nice to have” to a real filter for institutional investors and large corporate buyers. Samsung Fire’s alignment with frameworks like the Principles for Sustainable Insurance (PSI), along with its Coal Phase-out Principle, has helped position it as a more credible counterparty for clients that want their insurers to match their sustainability commitments.

Then there’s the slow-moving force that’s reshaping every insurer’s product mix: demographics. South Korea is aging fast, and over the long arc the senior population is expected to roughly double by 2050. That kind of shift changes what people buy. It pulls demand toward health coverage, long-term care, and retirement-oriented products—and it forces insurers to rethink longevity risk even as some traditional categories have weakened, including a sharp drop in whole-life policy sales between 2020 and 2024.

Health non-life insurance, in particular, is positioned for nearer-term growth as the state leans more on private carriers to help close gaps around the National Health Insurance Service (NHIS). And customer acquisition is evolving alongside it: more policies are being distributed through embedded channels on e-commerce, fintech, and mobility platforms, pushing insurers to compete on integration and convenience—not just brand.

Put it together, and you can see the shape of Samsung Fire’s next moat. An aging society increases demand for protection and retirement solutions. Digital channels change how customers choose providers. And in that environment, Samsung Fire’s combination of brand trust, distribution reach, and technology-enabled underwriting becomes a real advantage—not just a modernization project.

X. Playbook: Strategic and Business Lessons

So what should investors and business students take away from Samsung Fire’s seven-decade run?

Lesson 1: The Chaebol Advantage

Samsung Fire shows how valuable captive demand can be. Being tied to Samsung Group doesn’t just add brand credibility; it creates a built-in stream of business—both in Korea and overseas—that can be consistently profitable, especially in general insurance where loss ratios can be very favourable.

Think about what that really means in practice. Samsung Electronics operates in dozens of countries. Every one of those locations and supply chains creates insurance needs: property coverage for facilities, marine cargo for shipments, liability protection, and more. Samsung Fire can follow the group globally and write risks that competitors simply don’t get invited to quote. And with the Canopius partnership, it now has another layer of reach and capability to support that global footprint.

Lesson 2: Service Innovation as Moat

Samsung Fire didn’t build leadership by being the cheapest. It built it by being better at the moments that matter.

Midnight Express in 1989 was the early signal: make claims work when customers actually need you, not when it’s convenient for the insurer. Today, the same mindset shows up in AI-driven underwriting and faster, more accurate pricing in complex lines like cyber.

That operational edge compounds. A large, profitable in-force book creates stability, and the company’s ability to generate new business contractual service margin—future profit embedded in new contracts—supports its staying power in long-term insurance.

Lesson 3: Partnership Over Pure M&A

The Canopius deal is a reminder that “global expansion” doesn’t always mean buying something outright.

Samsung Fire took a staged approach: invest, collaborate, learn, and only then lean in harder. Over roughly six years, it used progressive investments and knowledge transfer to build familiarity with Lloyd’s market dynamics before making its largest commitment. That pacing reduced risk while building real institutional capability—something a headline-grabbing acquisition can’t guarantee on its own.

Lesson 4: Regulatory Navigation

K-ICS and IFRS 17 didn’t create new winners so much as they exposed old habits.

Samsung Fire entered the new regime with the kind of posture that suddenly matters a lot: a fortress balance sheet, low leverage, and conservative investing. When regulators push the industry toward fair-value realism, insurers that relied on aggressive leverage or riskier portfolios find themselves forced to raise capital, cut back, or consolidate. Samsung Fire, by contrast, gets to play offense while others are busy stabilizing.

Lesson 5: Brand as Competitive Weapon

The 1993 switch from Ankuk to Samsung Fire wasn’t just a name change—it was a trust transfer.

Insurance is a product where the customer is buying a promise, often one they hope they never have to test. In that world, credibility is a competitive advantage. Samsung’s reputation for quality—earned in electronics and reinforced across the group—became a shortcut to confidence in insurance, too. And once that trust is in place, it makes distribution easier, retention stronger, and expansion smoother.

XI. Porter's Five Forces and Hamilton's Seven Powers Analysis

Porter's Five Forces Analysis:

Threat of New Entrants: LOW

South Korea’s insurance market is hard to break into on purpose. The barriers aren’t just “it’s competitive.” They’re structural: you need substantial capital, a real on-the-ground presence, and regulatory approval before you can even start writing meaningful business. A good signal of how rare successful entry is: in October 2024, Starr International Insurance (Singapore) Pte. Ltd. was granted a license by South Korea’s Financial Services Commission to open a branch in Seoul and sell commercial property and casualty insurance nationwide. The fact that a single license becomes news tells you how infrequently new foreign players make it through the gate.

Bargaining Power of Buyers: MODERATE

For most individuals, insurance is a take-it-or-leave-it product. Customers can shop around, but they don’t usually have the leverage to negotiate pricing or terms. Corporates are different. Large accounts can push harder, and Samsung Group affiliates, in particular, have real influence because they buy at scale and have longstanding relationships. But those same relationships create friction in switching. When the insurer is already integrated into how a conglomerate operates, “just change providers” is rarely as simple as it sounds.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers: LOW

In insurance, the key suppliers are capital markets and reinsurers. Samsung Fire’s size and strong ratings give it leverage here, not vulnerability. With S&P and A.M. Best affirming ratings of AA- and A++ respectively, Samsung Fire can generally access reinsurance capacity and funding on attractive terms—especially compared with smaller competitors that need the same protection but can’t command the same pricing.

Threat of Substitutes: MODERATE-RISING

The substitutes aren’t other insurers; they’re other ways of getting covered. Insurtechs, embedded insurance sold at the point of purchase, and alternative risk-transfer structures are all chipping away at traditional distribution and product formats. That pressure is rising. The counterweight is that Samsung Fire has already been investing in digital, and its early scale in online auto insurance gives it a position many incumbents are still trying to build.

Competitive Rivalry: HIGH

This is a crowded market fighting over a mature opportunity set. South Korea has roughly 22 life insurers and 31 non-life insurers, and insurance penetration is about 11.1%—among the highest rates in the world. When most customers already have coverage, growth comes from taking share, squeezing costs, or finding new niche products. That’s fertile ground for intense rivalry, especially on price in commoditized lines.

Hamilton's Seven Powers Analysis:

Scale Economies: STRONG

As Korea’s largest non-life insurer, Samsung Fire benefits from real scale advantages: lower unit costs in claims operations, deeper underwriting data, and more efficient marketing and distribution. It also spreads fixed costs—regulatory compliance, tech infrastructure, and brand investment—across a larger premium base than any competitor, which matters more every year as compliance and technology get more expensive.

Network Effects: WEAK

Insurance doesn’t naturally produce classic network effects. One customer doesn’t directly make the product better for another in the way a social network does. The closest analogue is data: the bigger the book, the more underwriting and claims experience you can learn from. But that’s a softer, weaker form of network effects than true platform dynamics.

Counter-Positioning: MODERATE

Samsung Fire has positioned itself to evolve ahead of slower incumbents—particularly through digital initiatives and the Canopius partnership—but it hasn’t broken the industry’s model so much as executed it better. The differentiation is meaningful, but incremental rather than disruptive.

Switching Costs: STRONG

Insurance is sticky when it’s long-term, and even stickier when it’s embedded in corporate processes. Multi-year products create natural lock-in. Corporate programs—especially those tied to Samsung Group affiliates—can involve deep operational integration that’s costly and disruptive to unwind. Even in auto, where switching is technically easy, renewal behavior still tends to favor incumbents unless there’s a clear reason to leave.

Branding: VERY STRONG

In insurance, trust is the product. The Samsung name gives Samsung Fire instant credibility, and that credibility can translate into both customer acquisition advantages and better retention. The company’s #11 ranking on Newsweek’s World’s Most Trustworthy Companies 2024 list in the Insurance category is a modern proof point of a much older truth: when the promise matters, brand matters.

Cornered Resource: STRONG

Samsung Fire has access to something competitors can’t replicate: captive business tied to Samsung Group. That’s not just premium volume; it’s a durable pipeline of complex corporate risks that can anchor the portfolio. Layer on decades of auto insurance leadership and the underwriting data that comes with it, and you get another resource that new entrants simply can’t manufacture quickly.

Process Power: STRONG

The company’s edge isn’t only what it sells; it’s how it operates. From early service innovations like Midnight Express to modern AI-enabled underwriting, Samsung Fire has built processes over decades that create repeatable outcomes. And in insurance, where consistency is profitability, those embedded operating capabilities are one of the hardest advantages to copy.

XII. Key Performance Indicators for Investors

If you’re tracking Samsung Fire & Marine Insurance as an investment, you can boil a lot of complexity down to three numbers that tell you whether the machine is working.

1. Combined Ratio by Business Line

In property and casualty insurance, this is the scoreboard. The combined ratio—claims plus operating expenses, divided by premiums—tells you whether the company is making money on underwriting before investment income enters the picture.

Samsung Fire has historically run this well versus peers, which is another way of saying it tends to price risk correctly and operate with discipline. AM Best has pointed to that operating strength, citing a five-year average combined ratio of 28.6% from 2020 to 2024 and an average return on equity of 9.1%. Watch how this evolves by line of business. It’s the clearest read on whether Samsung Fire is winning on fundamentals or borrowing performance from the investment portfolio.

2. K-ICS Solvency Ratio

K-ICS is the post-2023 reality check. This solvency ratio measures how much capital Samsung Fire holds relative to what the regulator says it needs, after risk-weighting the whole balance sheet.

A strong K-ICS ratio gives Samsung Fire room to maneuver: it can keep writing business, absorb volatility, and still have flexibility for dividends, buybacks, or strategic moves. If this metric starts sliding meaningfully, it’s usually not noise—it’s an early warning that something is changing in the company’s underlying risk profile or capital position.

3. Canopius Contribution (Revenue and Equity-Method Profit)

Canopius is the global-growth bet, so investors need a way to separate “nice story” from “real economics.”

By 2024, Samsung Fire pointed to concrete outputs from the partnership: roughly 300 billion won (about $250 million) in co-reinsurance sales and around 88 billion won (about $73 million) in equity-method profits. As Samsung Fire moved to lift its ownership stake to 40%, this contribution became more than a footnote. It’s the metric that tells you whether the Lloyd’s-of-London strategy is actually compounding—or just consuming capital.

XIII. Bull Case, Bear Case, and Key Risks

Bull Case:

Samsung Fire offers something investors don’t get often in insurance: a dominant home-market franchise with a fortress balance sheet, plus a credible path to growth outside a mature domestic market.

The timing matters. The K-ICS and IFRS 17 transition is acting like a pressure cooker for the industry. When capital standards tighten and accounting becomes less forgiving, the strongest insurers don’t just survive—they tend to pick up share as weaker players retrench. Samsung Fire has been positioned for exactly that kind of environment.

And the company has continued to put up solid results. In Q2 2025, Samsung Fire reported net income of 638.4 billion won, up 4.2% year-on-year. In a market dealing with higher rates and inflation-driven claims pressure, that kind of steady outperformance is a signal: disciplined underwriting and cost control are doing their job.

Then there’s the upside option: Canopius. Samsung Fire gets exposure to Lloyd’s and global specialty insurance growth without taking on the full integration risk of an outright acquisition. And as the relationship deepens—more board participation, more operational collaboration—the value isn’t just in equity-method profits. It’s in institutional learning, distribution access, and building a real specialty underwriting muscle that’s hard to develop organically.

Bear Case:

The core challenge is the one Samsung Fire can’t fully escape: South Korea is a mature, highly penetrated insurance market, with demographics moving the wrong way for traditional growth. Low birth rates and rapid aging have slowed expansion in key segments, pushing the broader industry to chase “third-sector” products as a new source of demand.

There’s also structural governance risk. The chaebol model—cross-shareholdings and concentrated family control—can create a persistent concern for minority shareholders, where the incentives of the controlling group don’t always line up cleanly with outside investors. Samsung’s history of management controversies hasn’t derailed Samsung Fire’s day-to-day operations, but it does create ongoing reputational exposure and the possibility of regulatory backlash.

Finally, Canopius cuts both ways. Specialty insurance and reinsurance can look incredibly attractive—until it doesn’t. A major catastrophe, or a string of bad-loss years, can quickly erase recent gains and turn a growth engine into an earnings drag.

Key Risks:

Regulatory Risk: Korean regulators have continued to pressure chaebols to unwind cross-shareholdings. If rules change around insurers’ affiliate equity holdings, Samsung Fire could be pushed to sell valuable positions, potentially reshaping both its investment portfolio and its role inside the broader Samsung ecosystem.

Interest Rate Risk: A decline in discount rates used to value insurance liabilities over the next two years would increase reserve requirements. That can translate directly into capital volatility for Korean insurers, even for well-managed ones.

Concentration Risk: Samsung Fire’s profitable general insurance business benefits from Samsung Group affiliates, but that also creates exposure. If the broader Samsung ecosystem faces operational shocks or reputational damage, Samsung Fire can feel the second-order effects.

Execution Risk: The Canopius partnership only compounds if collaboration actually works—strategically and operationally—across different cultures, markets, and regulatory regimes. If coordination falls short, Samsung Fire could end up with a large stake that delivers weaker-than-expected strategic benefit.

XIV. Conclusion: The Long Game

Samsung Fire & Marine Insurance’s arc—from a small office in wartime Busan to a global specialty platform with a foothold in Lloyd’s of London—reads like the Korean economic miracle compressed into a single corporate life story. It was born in crisis, scaled through consolidation, sharpened by Samsung’s quality-first era, and now pushed outward through a patient partnership strategy that’s very different from the typical “buy it all and figure it out later” play.

If you strip the story down to an investment thesis, it’s this: Samsung Fire combines durable advantages in a domestic market that’s being forced to consolidate, with real upside from global specialty insurance. The K-ICS and IFRS 17 transition is acting like a stress test for the industry, and stress tests tend to widen the gap between the well-capitalized leaders and everyone else. Meanwhile, Canopius gives Samsung Fire exposure to faster-growing specialty profit pools—and the learning that comes with them—without taking on all the execution risk of a full acquisition.

The strongest signal of that posture is the balance sheet. Samsung Fire’s A++ rating sits among the highest in the industry, and AM Best has consistently tied that assessment to the same set of strengths: exceptional balance sheet strength, strong operating performance, a very favourable business profile, and very strong enterprise risk management.

For long-term investors, that’s the appeal. This is a franchise built to play the long game: stable domestic cash flows, deployed into global expansion with measured risk-taking, all backed by a capital position that’s hard for competitors to replicate quickly. The next chapter—deeper integration with Canopius, continued digital execution, and navigating Korea’s demographic shift—will determine whether Samsung Fire turns “global ambition” into a durable second engine of growth.

And zooming all the way back to the beginning, that’s what makes the story so striking. In January 1952, Koo Jin-hyun wasn’t trying to build a global insurer. He was trying to build something stable enough to survive. The fact that the company went on to endure war, political upheaval, financial crisis, and regulatory overhaul—and still find room to expand—says something important about what lasts in business.

Not hype. Not speed. Compounding capability, year after year, when the environment keeps changing. That’s how enduring franchises get written into history.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music