Power Assets Holdings: From Victorian-Era Hong Kong to Global Energy Empire

A deep dive into Hong Kong’s oldest electricity franchise, the quiet economics of regulated utilities, and the Li Ka-shing playbook that turned steady cashflow into an international empire.

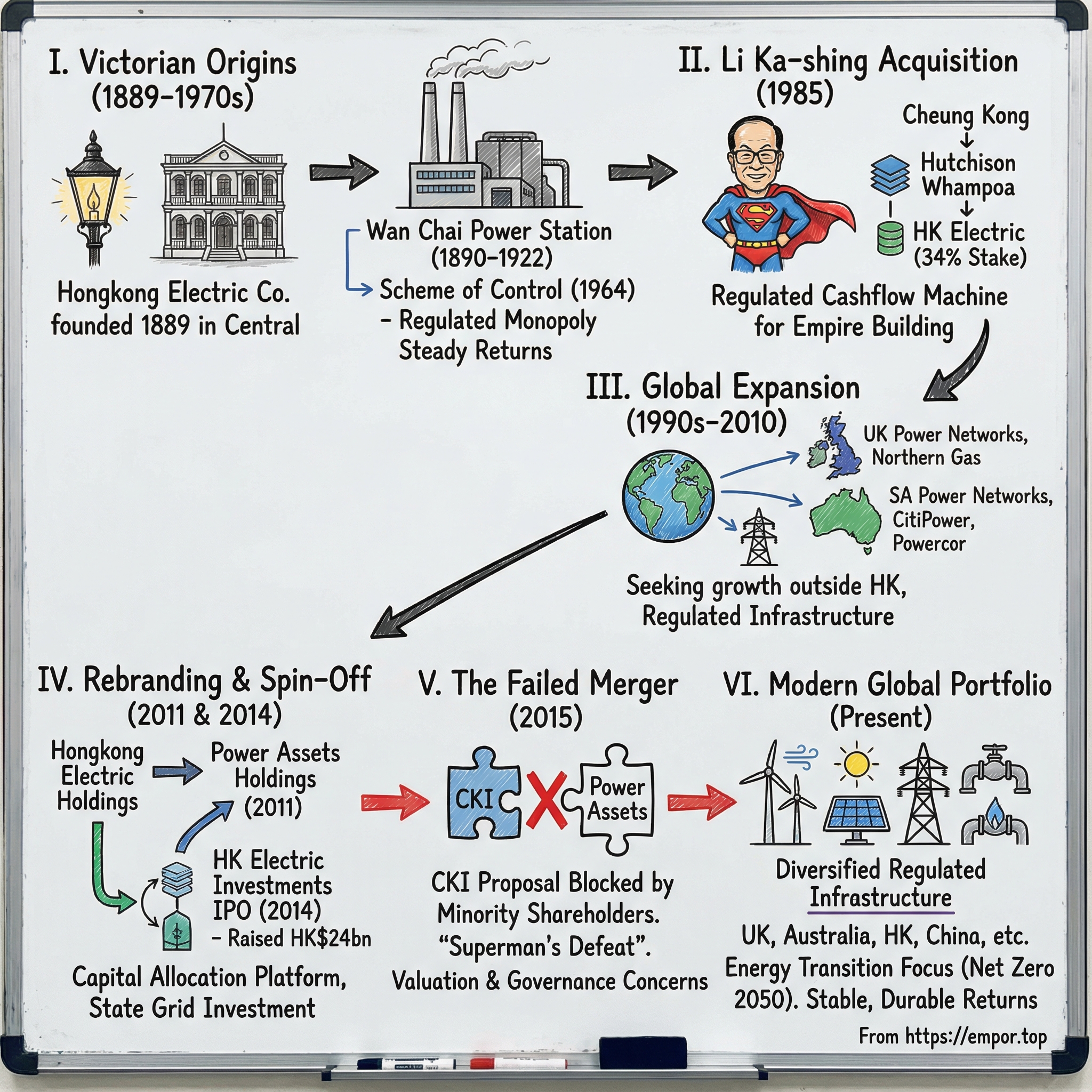

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

Picture Hong Kong Island at the tail end of Queen Victoria’s reign. Gas lamps flicker along the waterfront. Rickshaws rattle over uneven streets. Cargo moves from ship to shore under the watch of British trading houses in Central. And in 1889, in this humid, crowded outpost of the British Empire, a small group of colonial entrepreneurs floated an idea that sounded almost like science fiction: electric light.

That same year, the company that would become Power Assets was founded, headquartered in Central, Hong Kong. It started as a single-city electricity venture—one of the earliest in Asia. But the story doesn’t end as a charming tale of early electrification. Over the next century, it morphs into something much bigger: a global portfolio of regulated energy and utility assets spread across four continents, serving nearly 20 million customers.

A key turning point comes in February 2011, when Hongkong Electric Holdings Limited changes its name to Power Assets Holdings Limited. It wasn’t cosmetic. It was a signal to the market that this was no longer just “the Hong Kong power company.” It was becoming a holding company—an infrastructure investor—built to buy, own, and compound cashflows from essential networks around the world.

So here’s the question that drives everything that follows: how did a colonial-era electricity monopoly transform into a global energy infrastructure portfolio—and what happens when the empire-building instincts of Hong Kong’s most famous tycoon collide with the rights and expectations of minority shareholders?

You can see the shape of the business in the economics. Most income comes from regulated assets—steady, rule-bound returns that make utilities such powerful wealth machines. And while Hong Kong is where the story begins, the center of gravity shifts outward: the UK and Australia together contribute the majority of group profit. In 2024, Power Assets reported net profit of HK$6,119 million, up 2% from the year before—another reminder that, in regulated infrastructure, “boring” can be beautiful.

In this episode, we’ll follow the full arc: the colonial foundations of Hong Kong’s infrastructure, the Li Ka-shing acquisition playbook, the quiet power of the Scheme of Control, the push overseas through partnerships and platform deals, and then the moment it nearly all got consolidated into something even larger—until a dramatic failed merger delivered a rare, public defeat.

II. The Victorian Origins: Lighting Up Colonial Hong Kong (1889–1970s)

This story starts the way a lot of Hong Kong’s biggest businesses start: not with a visionary founder in a garage, but with a few well-connected people in the machinery of colonial government. After a meeting of the Executive Council on land reclamation, temporary councillor Bendyshe Layton floated a new idea to Sir Catchick Paul Chater: Hong Kong should generate electricity. The group moved quickly—and quietly—securing land in Wan Chai, where they would build one of the earliest power stations in the world.

Chater was the perfect person to make something like that real. He was an Armenian orphan from Calcutta who arrived in Hong Kong in 1864 as a 19-year-old bank clerk. By the time he was in his thirties, he’d become one of the colony’s most influential taipans—an operator with a nose for land, capital, and the kinds of “essential” businesses that only get more valuable as a city grows. Over the years, his name became attached to an extraordinary share of Hong Kong’s backbone institutions: Hongkong Land, Dairy Farm, the Star Ferry—and now, an electricity company that could literally change the city’s nights.

Chater took charge of financing the project, and in 1889 the company was incorporated. Its total capital was $300,000, divided into 30,000 shares, with half offered to the public. In other words: from the beginning, this wasn’t just a piece of engineering. It was also a piece of financial infrastructure—built to attract outside capital into a monopoly utility.

The first power station was modest by today’s standards: a 50-kilowatt, coal-fired plant in Wan Chai that began operating in 1890. The original facility was built in the colonial architectural style of the era and ran until 1922, when it was decommissioned. The city, of course, didn’t stop moving. In a neat little twist of Hong Kong redevelopment, the site later gave way to Art Deco residential flats.

Over the decades, ownership shifted among British hongs, but the core business barely changed. Hongkong Electric served Hong Kong Island, while China Light & Power took Kowloon and the New Territories—two investor-owned utilities, each with its own turf.

Then, in the 1960s, Hong Kong formalized what had already been true in practice: electricity wasn’t going to be a free-for-all market. The industry proposed a special regulatory framework in 1964 that became known as the Scheme of Control. This is the piece that explains why Hong Kong utilities became such formidable wealth machines.

The trade was straightforward. The power companies had an obligation to supply sufficient, reliable electricity and keep investing in infrastructure. In return, the government allowed them to earn a return that was considered reasonable relative to the capital invested. Customers got electricity that was meant to be sustainable and affordable. Investors got something even rarer: a regulated business where profitability was baked into the system.

That arrangement created a very particular kind of asset: a monopoly with a rulebook that protected long-term returns. For colonial administrators, it was stability and service without the chaos of competition. For anyone with ambitions of building an empire, it was a base layer—steady cashflow, defensible territory, and the ability to finance the next deal.

By the late 1970s and into the 1980s, the lines between Hong Kong property and Hong Kong infrastructure blurred again. Hongkong Land—founded by Chater decades earlier—reasserted its historic link to Hongkong Electric as it diversified to weather tougher conditions. It built positions in major local utilities and telecom assets, including a stake in Hongkong Electric.

And crucially, as Hong Kong’s economy surged, so did demand. By the early 1980s, Hongkong Electric was expanding generating capacity to keep up. The company wasn’t just supplying power; it was riding the city’s growth curve, protected by regulation, selling an essential product to customers who couldn’t switch even if they wanted to.

That’s the setup for what comes next. Because once you understand Hongkong Electric as a regulated, cash-generating machine—more annuity than business—the logic of the Li Ka-shing acquisition stops looking like opportunism and starts looking like inevitability.

III. The Li Ka-shing Acquisition: Superman's Power Play (1985)

By now, Hongkong Electric should look less like a “power company” and more like a machine: a regulated, cash-generating monopoly sitting right in the middle of a fast-growing city. That’s exactly the kind of asset that attracts a certain kind of buyer. And in 1985, the buyer was the most famous of them all: Li Ka-shing.

To understand why Hongkong Electric became a cornerstone inside the Li empire, you have to understand Li himself. His biography reads like a Hong Kong rags-to-riches story, but with real stakes and real consequences for how the city’s economy would be owned.

Li was born in 1928 in Chiu Chow, a coastal city in southeastern China. War and displacement pushed his family to Hong Kong. Then came the defining blow: his father fell ill with tuberculosis and died, and Li—still a boy—became responsible for keeping the family afloat. Before he was fifteen, he was working punishing sixteen-hour days at a plastics trading company, absorbing the basics of business the hard way.

In the 1950s, he found his first opening. Plastic artificial flowers were catching on in Western households, and Hong Kong could manufacture them cheaply and at scale. Li started a factory and rode that demand. But even early on, he was already looking past the product to the balance sheet. Manufacturing could make you money; land could make you rich.

Cheung Kong Industries began as a plastics manufacturer and gradually evolved into a property investment business. The bet that cemented Li’s reputation came in 1967. Riots in Hong Kong—sparked by turmoil spilling over from the Cultural Revolution in mainland China—sent property prices plunging. Many people panicked. Li bought. It was contrarian, aggressive, and, in hindsight, perfectly timed. Twelve years later, roughly one out of every seven private residences in Hong Kong had been developed by Cheung Kong.

Then came the move that announced Li’s arrival at the very top tier of Hong Kong business. In 1979, he took control of Hutchison Whampoa—one of the great British hongs—through a deal negotiated with the Hongkong and Shanghai Bank to buy its 22% stake at a price said to be less than half of book value. It wasn’t just an acquisition. It was a signal: the old colonial commercial order was no longer unchallengeable, and a new kind of local capital was now buying the crown jewels.

Hutchison became a platform: ports, retail, real estate, and a playbook of building new businesses and selling them when value could be realized. Over time that approach produced some famous exits, including the sale of its interest in Orange in 1999, and the sale of a stake in its ports business in 2006.

But the next step in empire-building wasn’t another flashy growth story. It was something quieter—and more powerful.

Six years after Hutchison, another opportunity fell into place. Hongkong Land had built a meaningful position in Hongkong Electric, but by 1985 it was under pressure. Debt from an aggressive expansion forced it to raise cash, and its 34% stake in Hongkong Electric became available for HK$3 billion. Hutchison Whampoa bought it, pulling the utility into Li Ka-shing’s orbit.

With Hutchison in 1979 and Hongkong Electric in 1985, Li was assembling a very specific kind of conglomerate. Property was cyclical. Ports were global and competitive. But a regulated electricity utility? That was different. It threw off cash with mechanical reliability, backed by a government framework, serving customers who weren’t going anywhere. As Hong Kong grew, the asset base grew. And as the asset base grew, so did the allowed return.

That’s why, for Li, Hongkong Electric wasn’t just another holding. It was an anchor: the kind of stable cashflow that can finance everything else.

By the time he took control, Li—known widely in Hong Kong as chiu yan, or “Superman”—presided over an empire measured in the hundreds of billions of Hong Kong dollars. And the logic beneath it was simple. Li believed deeply in synergy, in “combined efforts,” even down to the name Cheung Kong—after the Yangtze River, the great current built from countless tributaries. The empire would work the same way: different businesses, different risk profiles, all feeding a larger whole.

And unlike investors who needed quick exits, Li was patient. He was building for the long run. Regulated utilities, with their predictable returns and defensible market positions, were the perfect foundation for that kind of dynastic compounding—boring to outsiders, but invaluable to an empire builder.

IV. The Transformation Era: From HK Electric to Global Investor (1990s–2010)

With Hongkong Electric under Li Ka-shing’s control, the next job was straightforward: keep Hong Kong’s lights on as the city rocketed from industrial outpost to global financial center. That meant building generation and grid infrastructure at a pace that matched the economy’s ambition. The symbol of that era was the Lamma Power Station—an asset that anchored Hong Kong Island’s electricity supply and, just as importantly, the company’s regulated earnings base.

Lamma began life in 1982 as a coal-fired station built for Hongkong Electric to serve Hong Kong Island and Lamma Island. Over time it was expanded repeatedly, a physical record of the city’s surging demand. At scale, it became one of Hong Kong’s major generation facilities—second only to Castle Peak among the city’s coal-fired power stations.

What made this infrastructure so valuable wasn’t just steel and concrete. It was the regulatory bargain wrapped around it. Hong Kong’s electricity market has long been governed by Scheme of Control Agreements between the government and the two power groups: CLP on one side of the harbor, and HK Electric on the other. These agreements define what the companies must deliver, what shareholders are allowed to earn, and how the government oversees the utilities’ electricity-related finances.

The first Scheme of Control Agreement was signed in 1964 and then renewed in 1978, 1993, and 2008. Over decades, the framework evolved into something like capitalism with a rulebook: consumers were meant to be protected from abusive pricing, while utilities were given a clear path to earn dependable returns—so long as they invested and delivered reliable service. (A new agreement later came into effect on 1 October 2018.)

And HK Electric did deliver. Since 1997, it has maintained supply reliability above 99.999%—“four nines” performance that sits in the top tier globally. In a business where customers only notice you when you fail, that kind of consistency is the product.

But there was a ceiling. Hong Kong is dense, bounded, and finite. You can only build so many power stations on a territory smaller than Los Angeles. So the question for Li’s strategists became: where do you find the next decades of growth if your home market can’t physically expand?

Their answer was to take the model overseas—into jurisdictions that looked, from an investor’s perspective, comfortingly familiar: stable politics, rule of law, and regulated utility frameworks that turned essential infrastructure into long-duration cashflows.

Australia was the first real wave. In 2000 and 2002, the group acquired stakes in SA Power Networks, Powercor Australia, and CitiPower. Powercor operates across western Victoria and Melbourne’s western suburbs, running and maintaining the poles, wires, substations, and street lighting that underpin daily life. It’s 51% owned by Cheung Kong Holdings and 49% by Spark Infrastructure—an example of how these deals were often structured with partners, sharing both risk and returns.

The playbook that emerged was deceptively simple: buy regulated utilities in well-structured markets. “Regulated” was the magic word. In competitive industries, profits can vanish overnight. In regulated networks, returns may be capped—but the system is designed to make them durable.

Then came the UK—the richest hunting ground of all. On 30 July 2010, CK Infrastructure, the then-Hongkong Electric Holdings (later renamed Power Assets in 2011), and the Li Ka Shing Foundation announced the acquisition of three UK electricity networks businesses from Électricité de France.

The centerpiece was UK Power Networks, serving London and the southeast of England—some of the most valuable electricity real estate anywhere. The ownership structure captured the Li empire’s collaborative style: UK Power Networks sat jointly held by CKI and Power Assets, each with 40%, alongside CK Asset with 20%.

Electricity networks weren’t the end of it. Water and gas followed, as the group assembled stakes across the most “everyday” parts of British life—assets the public rarely thinks about until something breaks. Northumbrian Water, UK Power Networks, and later gas networks added up to a portfolio that made a company born on Hong Kong Island a major foreign owner of UK infrastructure. By the end of the decade, the transformation was already visible: this wasn’t just a Hong Kong utility anymore. It was becoming an international infrastructure investor, built to compound regulated cashflows into the next deal—and the next.

V. The Name Change & Strategic Pivot (2011): A Company Reborn

In February 2011, Power Assets did something that looked small on paper but was huge in meaning. Hongkong Electric Holdings Limited—a name that had been on the door for more than a century—became Power Assets Holdings Limited. To most people, it read like a routine rebrand. To anyone tracking Li Ka-shing’s strategy, it read like a mission statement.

The message to the market was simple: this was no longer “the Hong Kong electricity company.” It was a global infrastructure investment vehicle that happened to still own a marquee electricity business in Hong Kong. The company’s identity was moving from operating assets to owning them, from generating power to generating predictable, regulated returns.

Power Assets Holdings Limited is a global investor in energy and utility-related businesses with investments in electricity generation, transmission and distribution; renewable energy; energy from waste; gas distribution and oil transmission.

That single sentence captures the pivot. The company was evolving from an operator—running plants, serving customers, managing day-to-day reliability—into a holding company designed to own stakes, collect dividends, and keep recycling capital into the next regulated network.

That structure mattered because it unlocked three very practical advantages.

First, diversification. If the regulatory environment in Hong Kong changed, it would still sting—but it wouldn’t be existential. Earnings and cashflows were increasingly spread across currencies, regulators, and economies.

Second, scalability. A holding company can keep buying without needing to stitch every new asset into one centralized operating machine. You can own a network in the UK, a distributor in Australia, and generation elsewhere, each run locally under its own rules—while the parent focuses on capital allocation.

Third, flexibility inside the broader Li ecosystem. Different parts of the Li empire could co-invest, pool capital for large acquisitions, and share returns according to the stakes they held—an efficient way to play bigger games without forcing everything into one corporate box.

The name change also acknowledged a hard physical constraint: Hong Kong is a small place. By 2011, meaningful growth wasn’t going to come from endlessly building on a bounded island. It was going to come from deploying capital into developed markets where privatization created openings and where the rule of law made “regulated returns” feel bankable. The UK, Australia, New Zealand, and Canada would become the most natural hunting grounds.

Over time, Power Assets leaned into a deliberate approach: seek growth in stable and well-structured international markets. That phrasing wasn’t marketing fluff—it was the whole philosophy. In a world where the biggest growth rates often come with the biggest surprises, Power Assets chose the opposite trade: slower growth, lower risk, and the chance to compound steadily for decades.

For investors, it reframed what the stock represented. You could buy a single domestic utility and take one set of regulatory and currency bets. Or you could buy Power Assets and get a portfolio of regulated infrastructure exposures bundled into one listed company—diversified across geographies, built for consistency, and run with the Li playbook of patient, long-duration value creation.

VI. Inflection Point #1: The HK Electric Spin-Off (2014)

By 2014, Power Assets had a very good problem—and a very strategic one. An enormous amount of value sat inside a single crown jewel: its Hong Kong electricity business. Protected by the Scheme of Control and serving one of the wealthiest, densest markets in the world, HK Electric was a cash machine. But as a wholly owned subsidiary, it was also trapped inside Power Assets’ consolidated financials, harder for the market to value on its own terms.

So Li Ka-shing’s team engineered a move that was equal parts financial unlock and strategic pivot: spin HK Electric out, list it, and turn “the Hong Kong power company” into something closer to a capital-allocation platform.

Power Assets, controlled by Li, raised HK$24 billion by listing its Hong Kong electricity assets as HK Electric Investments. It was the biggest IPO out of Asia that year, and the largest utility and energy sector IPO from an Asia-Pacific issuer in more than a decade.

The structure was unusual for Hong Kong: a business trust, a vehicle more often seen in Singapore. HK Electric, spun out from Power Assets, priced at HK$5.45—right at the bottom of its indicated range—implying a 2014 yield of 7.24%.

In headline terms, it was still a blockbuster: about US$3.1 billion, one of Hong Kong’s largest IPOs on record. But it also came in below the company’s early ambitions. When the spin-off was first announced in mid-December, Power Assets had hoped the offering could raise as much as US$5.7 billion.

That gap tells you a lot about how investors saw the deal. Demand was steady, not euphoric. The public tranche was only covered by a single-digit multiple and never got hot enough to trigger a claw-back. And the yield investors demanded—north of 7%—was effectively the market’s way of pricing in two worries at once: rising interest rates, and uncertainty around the next renewal of Hong Kong’s Scheme of Control.

Then came the most interesting twist: who showed up as cornerstone investors.

HK Electric secured US$1.168 billion, or 37% of the float, from State Grid International Development and the Oman Investment Fund. State Grid alone took US$1.118 billion, or 35.9%—a huge commitment from the world’s largest electric utility, a state-owned enterprise that was itself hunting for overseas assets.

It was a striking moment. Hong Kong’s oldest electricity franchise—born in the Victorian era, long embedded in the colony’s British commercial architecture—now had China’s national grid as a major shareholder. Whatever you thought of the valuation, the signaling was undeniable: Beijing’s corporate reach was no longer just across the border. It now ran straight into Hong Kong’s critical infrastructure.

For Power Assets, the transaction did exactly what it was designed to do: it created a war chest. By selling a 50.1% stake in the Hong Kong operations, Power Assets received HK$31.7 billion to fund future acquisitions. It kept 49.9% of HK Electric, but the center of gravity shifted overnight. The company that once operated a local monopoly was now primarily an owner of stakes—often minority stakes—in regulated utilities around the world.

HK Electric Investments itself continued under Hong Kong’s regulatory framework. It operates under a Scheme of Control agreement with the government, designed to produce stable income based on an allowed return. Under the scheme effective from 2018, that allowed return is around 8% on the asset base.

Strategically, this new structure came with trade-offs. On the upside: diversification, steady dividends, and less direct operational exposure. On the downside: with minority positions in many investments, Power Assets often couldn’t fully control outcomes—limiting its ability to force operational changes, capture synergies, or unilaterally reshape strategy.

But for investors, the message of 2014 was unmistakable. Power Assets was no longer something you valued like a utility operator. It was a listed portfolio—its future driven less by how flawlessly it ran power stations in Hong Kong, and more by whether it could keep buying regulated assets at the right price, and harvesting the cashflows they reliably kicked back up to the holding company.

VII. Inflection Point #2: The Failed Merger – Superman's Rare Defeat (2015)

By 2015, this was supposed to be the tidy ending to a very Li Ka-shing story.

Li was 87, at the height of his reputation as “Superman,” and he’d just set in motion a sweeping reorganization of his empire. Cheung Kong Holdings and Hutchison Whampoa were combined into CK Hutchison Holdings. The property business was spun out as CK Asset Holdings. The message was clear: simplify the web, sharpen the strategy, and set the structure up for the next era under his son Victor.

But one piece still sat awkwardly on the board: Power Assets.

The obvious move—at least from headquarters—was to fold Power Assets into Cheung Kong Infrastructure, or CKI, and unify the group’s infrastructure holdings under one roof. In September 2015, CKI proposed an all-stock merger. Power Assets shareholders would have their shares cancelled and receive newly issued CKI shares in exchange. Power Assets would become a subsidiary of CKI.

On paper, the logic was easy to sell. CKI would emerge bigger, with a stronger balance sheet and more firepower to pursue global infrastructure deals. And Power Assets, freshly stocked with cash after the HK Electric spin-off, was sitting on a massive war chest—nearly HK$58 billion in net cash—earning little while management hunted for acquisitions. A merger would effectively pull that cash into CKI’s broader mandate and, in theory, put it to work faster.

The offer was pitched as close to a merger of equals: CKI proposed to buy the roughly 61% of Power Assets it didn’t already own, paying in shares and sweetening the proposal with a promised US$2.5 billion special dividend if the deal completed.

Then the part happened that the Li playbook rarely had to account for: pushback.

Power Assets had a large base of minority shareholders—investors who didn’t sit inside the Li family’s control structure. And many of them looked at the proposal and saw a familiar problem: they were being asked to trade an asset they already liked for paper in an affiliated company, at a price that felt set by the seller.

Proxy advisers moved first, and they moved loudly. Institutional Shareholder Services told minority shareholders to vote no, arguing the all-stock offer should be improved—by as much as 13%—and criticizing the fact that the special dividend would only be paid after the deal went through. Soon after, Glass Lewis also recommended investors reject the deal. Analysts piled on with a blunt conclusion: with the voting mechanics in Hong Kong, the transaction would be “almost impossible” to pass unless CKI made the terms meaningfully more attractive.

The heart of the revolt was valuation. Power Assets wasn’t some sleepy subsidiary waiting to be rescued. It had cash, it had a diversified set of regulated assets overseas, and it had a mandate the market understood: own infrastructure, collect steady returns, and compound patiently. Many minority holders didn’t see why they should swap that for CKI shares at the proposed ratio—especially when they believed Power Assets was worth more on its own.

The vote came in November 2015, and it landed like a thunderclap in Hong Kong’s business community.

Minority shareholders blocked the merger. Among independent minority votes, about 49.23% opposed the proposal and 50.77% supported it—but that wasn’t the hurdle that mattered. Under the rules, the scheme needed a 75% supermajority to pass. It didn’t get there.

For once, Superman had lost.

Power Assets’ response was restrained but unmistakably bruised. “We are disappointed at today’s voting result but respect the views expressed by shareholders,” a spokesman said, adding that the company would review next steps with the objective of delivering long-term value.

Hong Kong’s takeover rules then locked the door: CKI couldn’t make another attempt for a year. That year passed. Then another. The deal never came back. Power Assets stayed listed and separate—still part of the CK universe, but not fully absorbed into it—because minority shareholders had successfully defended the boundary.

The lessons were hard to miss. First, Hong Kong governance can bite: supermajority rules mean minority investors can stop even the most powerful sponsors if the terms don’t feel fair. Second, valuation is real power. Reputation and legacy don’t close a discount. And third, the same cross-holdings that make the Li empire so effective for doing deals can also create conflicts—and in this case, the market made clear it wasn’t willing to simply trust the center.

VIII. The Modern Power Assets: A Global Portfolio (2015–Present)

In the decade after the failed merger, Power Assets settled into the shape it had been moving toward for years: less “Hong Kong power company,” more globally diversified infrastructure portfolio—built to own regulated, essential networks and quietly collect the returns.

By now, the footprint spans Hong Kong, the United Kingdom, Australia, New Zealand, Mainland China, the United States, Canada, Thailand, and the Netherlands. Across those investments, the company helps deliver reliable energy to about 19.5 million customers. Under the hood, the portfolio is a mix of old-world utility muscle and newer transition assets: over 1,000 MW of renewable energy and energy-from-waste capacity, more than 5,200 MW of gas-fired generation, and roughly 3,800 MW of coal- and oil-fired capacity. It also reaches into the “plumbing” of modern energy: around 114,200 kilometers of gas and oil pipelines, and about 402,500 kilometers of power networks.

Look at the holdings and the pattern is clear: this is a collection of regulated assets in markets where the rules are designed to keep the lights on—and keep capital coming in. Power Assets sits alongside CK Infrastructure (CKI), another pillar of the Li Ka-shing empire, which holds a broad spread of infrastructure investments across energy, transportation, water, waste management, waste-to-energy, and other essential services in Hong Kong, Mainland China, the UK, continental Europe, Australia, New Zealand, Canada, and the United States.

In the UK, Power Assets owns 40% of UK Power Networks, the electricity distribution business serving London, the Southeast, and the East of England—some of the most densely loaded, economically critical grid territory in the country. The UK remains a major profit center. In 2024, the UK contributed HK$3,199 million to Power Assets, supported by strong operational results from UK Power Networks and other UK investments. Power Assets also holds 30% of Wales & West Utilities, a gas distribution network operating 35,000 kilometers of pipelines and serving 7.5 million people, and a 41.29% interest in Northern Gas Networks.

In Australia, the story is similar: regulated networks, long-duration cashflows. Power Assets has stakes in SA Power Networks, CitiPower, and Powercor—electricity distribution networks serving South Australia and Victoria. CitiPower and Powercor, together known as Victoria Power Networks, supply electricity to more than 1.2 million residential and commercial customers across Victoria.

But the newest chapter is about what every utility on Earth is now forced to write: the energy transition. Power Assets committed to phasing out coal-fired generation across its operations by 2035, cutting scope 1 and 2 emissions by 67% from a 2020 base, and reaching net zero by 2050. Those targets reflect regulatory pressure, investor expectations, and a practical portfolio reality: over time, capital will be priced for clean assets, and increasingly penalize the rest.

That shift shows up in deal flow too. In 2024, CKI continued buying renewables in the UK, including an acquisition of 32 onshore wind farms—its third such purchase that year—following a deal for a natural-gas network in Northern Ireland in April and the purchase of 70 UK solar, wind, and hydropower assets in May.

CKI bought UU Solar, which owns and operates 70 renewable generation assets in the UK, for £90.8 million. The acquisition was made through UK Power Networks Services, a distributor owned by CKI (40%), Power Assets (40%), and CK Asset Holdings (20%). The UU Solar portfolio includes 65 solar projects, four onshore wind farms, and one hydropower plant, with a combined installed capacity of 68.7 MW.

Outside the UK, renewables have been expanding too. In Canada, Power Assets acquired wind power facilities totaling 30 MW in 2021. Then in October 2024, Power Assets completed another renewables deal: 175 MW across 32 wind farms in the United Kingdom.

Along the way, the company expanded through acquisitions including Phoenix Energy and UK Renewables Energy, adding to the platform and deepening its position in the markets it knows best. It also emphasized balance-sheet resilience—highlighting a low net debt-to-net total capital ratio and an A/Stable credit rating—as it positioned for the next wave of opportunities.

This is the tightrope act for Power Assets going forward. The opportunity is to keep doing what it has always done well: buy long-life infrastructure in stable jurisdictions at the right price, and let regulation do the heavy lifting on returns. The challenge is to manage the decline of coal while protecting the steady, utility-like economics the entire portfolio is built on. The next decade won’t just test the company’s deal instincts. It’ll test whether “regulated and boring” can stay beautiful as the definition of a “good” energy asset changes underneath it.

IX. The Succession & Governance Structure

When Li Ka-shing retired at age 89, it wasn’t a sudden handoff. It was the last move in a transition that had been choreographed for years. On 16 March 2018, after decades at the center of CK Hutchison Holdings and CK Asset Holdings, Li announced he would step down and pass the reins of the empire to his son, Victor Li. Li didn’t disappear—he remained involved as a senior advisor—but the era of “Superman” as the active captain was over.

Li has two sons, Victor and Richard, both Canadian citizens. Victor, the elder, became Chairman of CK Hutchison Holdings and Chairman of CK Asset Holdings. Richard took a different track, serving as Chairman of PCCW, Hong Kong’s largest telecom company, along with other interests.

That split was intentional. Victor inherited the core CK machine—the infrastructure, ports, retail, and utilities businesses that formed the spine of the group. Richard’s portfolio centered on telecom. In family conglomerates, succession can be where empires crack. Here, the division was designed to avoid the kind of sibling rivalry that has destabilized other Asian dynasties.

But Power Assets’ governance story isn’t only about the Li family. The chairman of Power Assets Holdings Limited is Canning Fok Kin-ning.

Within Hong Kong business circles, Fok is widely seen as Li Ka-shing’s right-hand man—his longtime lieutenant and dealmaker. He has worked alongside Li for more than four decades, rising from an accountancy background into the inner circle that runs the group’s far-flung businesses. Over the years, he has held senior roles across the Cheung Kong and Hutchison universe, overseeing major operations from telecommunications to ports to utilities. He joined the Hutchison board in 1984 and the Cheung Kong board in 1985, later becoming managing director of Hutchison in 1993. He holds a Bachelor of Arts degree from St. John’s University in Minnesota, a diploma in financial management from the University of New England in Australia, and is a member of the Australian Institute of Chartered Accountants.

This matters because Power Assets sits inside a broader structure that is equal parts aligned and hard to parse. The CK empire is held together by cross-holdings and frequent co-investments: CK Hutchison owns 75.67% of CK Infrastructure (CKI). CKI, in turn, owns 36% of Power Assets. From there, Power Assets holds stakes in operating companies, often alongside CKI and other group entities.

In practice, many acquisitions are executed jointly. When Power Assets buys an asset, CKI and CK Asset often participate as well. The arrangements are disclosed, but the layering can be difficult for outside investors to follow—especially when trying to answer the simplest question in conglomerate investing: where, exactly, is value being created, and where does it ultimately land?

The failed 2015 merger made the tension explicit. Power Assets’ minority shareholders didn’t share the same incentives as the controlling shareholders. The center of the empire wanted simplification and consolidation. Minorities wanted full value and clean terms. When those interests collided, minority investors were able to stop the deal.

That episode still hangs over the story. Victor Li has kept Power Assets independently listed, but the strategic logic for consolidation hasn’t gone away. The open question is whether management could ever craft a structure and valuation that minority shareholders would accept—or whether Power Assets will continue to operate as a semi-independent island inside the CK archipelago.

X. Porter's Five Forces Analysis

To really understand Power Assets, you have to understand the game it’s playing. This isn’t Silicon Valley, where competitors materialize overnight and customers churn on a whim. Regulated utilities are closer to economic bedrock. If you already own the network, the structure of the industry tends to protect you.

Threat of New Entrants: VERY LOW

In most industries, competition shows up because someone can build a better product or reach customers more cheaply. In regulated utilities, competition has to show up with concrete, steel, permits, and decades of political permission.

The barriers are massive. Building generation or a distribution network requires enormous capital. Regulatory approvals are slow, complex, and often designed to prevent duplication. And the infrastructure itself is a natural monopoly: it makes no economic sense to build a second set of wires and substations to serve the same streets.

Hong Kong’s Scheme of Control Agreements don’t technically grant exclusive rights, and they aren’t formal franchises. But in practice, HK Electric has never faced a serious would-be challenger on Hong Kong Island. When the incumbent already has the grid and the regulator caps returns, a new entrant would have to spend a fortune just to earn a regulated return in someone else’s shadow. That’s not disruption; that’s self-harm.

The UK and Australia work the same way. Electricity distribution networks are regulated monopolies. A newcomer would need to build parallel infrastructure to reach the same customers. No rational investor does that.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers: LOW TO MODERATE

The key inputs are fuel and equipment: coal and natural gas on the generation side, and the physical guts of the grid—turbines, transformers, cables, control systems—on the network side.

Fuel suppliers can have moments of leverage, especially for natural gas when geopolitics tighten markets. But Power Assets operates across multiple jurisdictions with diversified supply arrangements, which limits the power any single supplier can exert.

On equipment, the advantage tends to sit with the buyer. Major hardware is sourced from global manufacturers competing for large, long-term contracts. Scale helps here: when you’re building and maintaining big networks across countries, you can negotiate from strength.

The energy transition does introduce some supplier concentration—certain turbine models, certain grid technologies—but globally the market remains competitive enough that suppliers rarely get to dictate terms for long.

Bargaining Power of Buyers: LOW

This is the heart of the utility model. In a monopoly service territory, customers don’t “choose” their electricity network the way they choose a bank or a phone plan. Households and businesses are effectively captive to the local grid.

The Scheme of Control makes the trade explicit: the utility is obligated to supply reliable, efficient electricity at a reasonable price, and in return the regulatory system provides a framework for earning a defined return. That oversight protects consumers from price abuse, but it also protects the utility from the kind of whiplash you see in competitive markets. The result is what investors crave: predictable cashflows that don’t depend on marketing brilliance or consumer sentiment.

Threat of Substitutes: LOW BUT RISING

For most of modern history, “substitute for grid electricity” was basically not a thing. Electricity is foundational, and the grid was the only realistic way to deliver it at scale.

That’s beginning to shift at the edges. Rooftop solar paired with batteries can reduce a customer’s reliance on the grid. Electric vehicle batteries, in theory, can act as distributed storage. Efficiency gains can flatten demand growth.

But this is a slow-motion change, not a sudden collapse. The grid remains essential—not just for backup, but for balancing supply and demand across entire regions. The more important strategic takeaway is that utilities can’t treat these trends as enemies. They have to modernize: invest in smarter networks, integrate distributed resources, and upgrade infrastructure so the grid stays central even as generation becomes more decentralized.

Industry Rivalry: LOW

Utilities don’t fight the way most companies fight. They don’t compete on price, and they generally don’t compete for customers within the same territory. Returns are set by regulators, and service areas are geographically defined.

Where rivalry does show up is in dealmaking—competing to buy high-quality regulated assets when they come up for sale. In that arena, Power Assets goes head-to-head with deep-pocketed rivals like pension funds, sovereign wealth funds, and infrastructure specialists. As more global capital has poured into “safe” infrastructure, acquisition prices can rise, and future returns can get squeezed.

Overall Assessment

This is one of the most incumbent-friendly industry structures in the global economy. New entrants are effectively blocked, customers have limited leverage, and day-to-day rivalry is minimal. The big variable—the one that actually matters—is regulation. Governments can change the rules, lower allowed returns, or require expensive investments.

But if you’re a patient, long-term owner, that’s the bargain: accept regulatory oversight in exchange for durability. And for Power Assets, durability is the whole point.

XI. Hamilton's 7 Powers Framework Analysis

Hamilton Helmer’s 7 Powers framework is a useful second lens here, because it forces a simple question: what, exactly, keeps Power Assets’ returns durable over time?

1. Economies of Scale: MODERATE

Scale matters in utilities, but it’s not the “winner takes all” dynamic you see in software or manufacturing. Running a grid does have fixed costs, and larger networks can spread those costs across more customers.

Power Assets gets some benefit from being a portfolio owner—shared capabilities like finance, risk management, and regulatory know-how travel well across countries. But the core operating scale advantage is mostly local. A bigger network in Australia doesn’t magically make a network in the UK cheaper to run. The real payoff from global scale is diversification, not giant operating synergies.

2. Network Effects: WEAK

Electricity networks are, physically, networks. Wires and substations connect generation to consumers. But that’s not a network effect in the Facebook or Visa sense, where every new user increases the value of the system for every other user.

What Power Assets does have is customer lock-in. If you live on a particular street, there’s only one set of wires serving you. That’s not a network effect—it’s switching costs.

3. Counter-Positioning: STRONG (Historically)

Counter-positioning is about taking a business model incumbents can’t copy without hurting themselves.

The cleanest example is 1985. When Li Ka-shing acquired Hongkong Electric, the old British hongs weren’t outmaneuvered; they were constrained. They needed cash and became forced sellers. Li could buy what they couldn’t afford to keep.

Later, the global expansion strategy was another version of the same move. Many utilities were anchored to one market and one regulator. Power Assets built a globally diversified set of regulated exposures—different regulatory cycles, different currencies, different economies—in a way a single-market utility couldn’t easily replicate.

And then there’s the decision to partner with Chinese state investors like State Grid rather than treat them purely as competitors. In infrastructure, sometimes the smartest move isn’t to fight the biggest player in the room. It’s to make them a stakeholder.

4. Switching Costs: VERY HIGH

This is the most powerful “power” in the whole story. Customers of regulated monopoly networks can’t realistically switch providers, because there usually isn’t another network.

Regulation reinforces that stickiness. Multi-year tariff structures set the economics for long stretches of time. Long-term capital plans tie utilities and governments together in ongoing, complex relationships. And the regulatory rulebook itself becomes a barrier: incumbents understand it through decades of operating history in a way outsiders don’t.

5. Branding: WEAK

Utility branding rarely drives demand. Customers don’t pick their electricity network the way they pick a phone plan; in most cases, they get whoever serves their address.

Reputation still matters at the margins—especially with regulators and in acquisitions—because it signals competence and reliability. HK Electric’s supply reliability has been above 99.999% since 1997, which is world-class. But that’s less about creating consumer love and more about proving you can meet the standard regulators and governments expect.

6. Cornered Resource: STRONG

This is the other major pillar. The infrastructure itself—Hong Kong Island’s generation and supply system, London’s distribution networks, major gas pipelines—can’t be economically duplicated. These are natural-monopoly assets embedded in the real world.

Even more valuable than the physical assets are the regulatory licenses and permissions that come with them. The right to operate a regulated utility in a specific territory, and earn a defined return on investment, is a government-granted privilege that’s extraordinarily hard to challenge.

The Hongkong Electric Company Limited mainly concentrates on the generation and supply of electricity on Hong Kong Island and Lamma Island. It isn’t a formal franchise, but in practice it functions like one—and it has persisted for more than 135 years.

7. Process Power: MODERATE

Power Assets also has something that’s less visible but very real: an accumulated playbook for buying and owning regulated infrastructure. Over decades, the broader Li ecosystem has learned how to identify the right jurisdictions, structure deals, work with regulators, and run assets to meet performance requirements.

That experience is valuable. It’s also not totally uncopyable. Deep-pocketed competitors—pension funds, sovereign wealth funds, large infrastructure managers—can build similar capabilities over time. So this is a meaningful advantage, but not an invincible one.

Overall: Strong Competitive Position

If you boil it down, Power Assets’ durability comes from two sources: extremely high switching costs and genuinely cornered resources. Counter-positioning and process power add strength around the edges, especially in dealmaking and portfolio construction. The weaker powers—network effects, branding, and global economies of scale—matter less here because regulated utilities don’t win the way consumer or tech businesses win.

The result is a business with very durable advantages, but one that will always be constrained by the same thing that makes it investable in the first place: regulation.

Key Investment Considerations and Key Performance Indicators

If you’re looking at Power Assets as an investment, the right mental model isn’t “a utility you can benchmark against other utilities.” It’s closer to “a portfolio of regulated cashflows,” spread across multiple regulators, currencies, and political climates—run by a group that has been buying this kind of infrastructure for decades.

The trick is knowing what to watch, because the headline revenue number won’t tell you much about what really drives value here.

Key Performance Indicators to Track

The most useful KPIs for tracking Power Assets’ performance are:

1. Earnings Contribution by Geography: Keep an eye on where profits are actually coming from—UK, Australia, Hong Kong, and the smaller positions elsewhere. When that mix shifts, it’s usually telling you something: either the portfolio is growing in a region through acquisitions, or one regulator’s decisions are changing the economics. In recent years, the UK and Australia together have contributed more than 65% of group profit, which is a meaningful concentration compared to the company’s earlier, more Hong Kong-centered identity.

2. Dividend Payout Ratio and Yield: Power Assets is, at its core, a holding company that lives on the dividends it receives from underlying assets. So the dividend isn’t a side benefit; it’s the product. Watch whether the dividend looks comfortably covered, and how the yield stacks up versus alternatives like government bonds and other utility stocks. When the yield moves, it’s often the market repricing regulation risk and interest-rate risk—not just day-to-day operating performance.

3. Scheme of Control Returns (Hong Kong): HK Electric’s profitability ceiling is set by Hong Kong’s Scheme of Control Agreement. Under the current agreements, the permitted rate of return was reduced to around 8%, part of the government’s effort to ease pressure on electricity bills. Any future adjustment to this framework flows straight through to the Hong Kong portion of earnings.

Regulatory and Legal Considerations

More than anything else, Power Assets is a bet on regulators behaving predictably.

In Hong Kong, the Scheme of Control Agreement runs until 2033. That long runway provides visibility, but it also means there’s a clear date on the calendar when renegotiation risk comes back to the forefront.

In the UK, the equivalent moments are Ofgem’s multi-year price reviews for electricity and gas networks. These cycles create windows where uncertainty spikes and investors have to handicap the next settlement. The UK energy crisis also put utility profits back in the political spotlight, which can matter even in a system built around rule-based regulation.

Energy Transition Risks

Power Assets has committed to phasing out coal-fired generation by 2035, cutting carbon emissions by 67% versus its 2020 baseline, and reaching net zero by 2050.

That’s a real strategic shift, and it isn’t free. Retiring coal assets and replacing capacity—whether by building, buying, or partnering—takes capital and execution. Regulated returns can soften the blow in parts of the portfolio, but they don’t eliminate the risk: the transition will still test how well the group allocates capital in a world where “good utility assets” are being redefined in real time.

Corporate Structure Considerations

Finally, there’s the CK Group factor: the structure works, but it’s complicated.

Power Assets often invests alongside CKI, CK Asset, and the Li Ka Shing Foundation through joint ventures and co-investments. That can be a feature—letting the group pool capital for large deals—but it also means outside investors have to pay attention to alignment and related-party dynamics. Minority shareholders showed in 2015 that they can draw a hard line when they think a proposal tilts too far toward the center of the empire. That protection exists. But so does the possibility that restructuring ideas return in a different form later.

Conclusion: What Power Assets Means for Long-Term Investors

Power Assets is something you don’t see often anymore: a straightforward way to own regulated infrastructure cashflows across multiple countries, run by a team that’s been doing this for decades. The company started life as a Victorian-era electricity provider, but it grew into a global holding company with the same underlying promise: earn steady returns from essential assets under a regulatory compact.

The bull case is simple and, in many ways, timeless. Regulated networks are built to be dependable. A diversified portfolio spreads exposure across different regulators and economies. And a strong balance sheet gives the company room to keep buying when the right assets come up for sale. In a market that swings wildly between “growth at any price” and “cashflow is king,” Power Assets sits firmly in the second camp—and that has real appeal when interest rates are higher and risk gets repriced.

The bear case is just as real. Regulation is the ultimate gatekeeper, and it can change. Allowed returns can be cut, investment requirements can rise, and political pressure can bleed into decisions that are supposed to be formula-driven. The energy transition adds another layer of uncertainty, especially around how legacy fossil fuel assets are valued, funded, and ultimately retired. And then there’s structure: the CK web of cross-holdings and controlling-shareholder influence isn’t inherently bad, but it does force outside investors to keep asking a practical question—when interests diverge, whose preference wins?

For investors who want infrastructure exposure, Power Assets is a distinctive proposition. It isn’t a bet on one market. It isn’t powered by breakthrough innovation. It’s a claim on the cashflows of assets modern society can’t function without: wires, pipes, networks, and the systems that deliver energy reliably, day after day.

And that’s the throughline of the whole story. From a 50-kilowatt power station in Wan Chai to a portfolio spanning continents, Power Assets has moved through more than a century of political change, financial cycles, and technological shifts—while keeping its essential role the same. It keeps the lights on. For patient investors who understand what they’re buying, that kind of continuity can be quietly, compounding-ly valuable.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music