Towngas: The 163-Year Journey of Hong Kong's First Public Utility

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

Picture Hong Kong in 1862. The island is barely two decades into British rule: a rocky trading outpost of about 123,000 people perched at the edge of a vast Chinese empire. There are no streetlights. When the sun drops behind the hills, Victoria—today’s Central—falls into darkness, lit by little more than oil lamps and candles.

Into this world walks a Scottish entrepreneur named William Glen. Here’s the twist: in 1861, Glen had no real knowledge of the gas industry. But he did have something just as valuable in a frontier economy—an eye for the missing piece. He goes to Governor Sir Hercules Robinson and secures a concession to supply gas to the city of Victoria. On May 31st, 1862, the company is incorporated.

That modest beginning becomes The Hong Kong and China Gas Company—Towngas. And from there, it’s a 163-year run that reads like a stress test for corporate survival: colonial rule, war and occupation, revolution across the border, the long shadow of 1997, and now the clean-energy transition that threatens the very idea of “gas” as we’ve known it.

The deceptively simple question at the heart of this story is: how does a gas lighting company—whose original product effectively became obsolete—manage not just to survive, but to keep finding new legs, again and again, across radically different eras?

Today, Towngas’s core business is still exactly what you’d expect from the name: producing and distributing town gas in Hong Kong. It’s a monopoly in all but legal phrasing—controlling piped gas distribution and retail—and it supplies roughly 85% of Hong Kong households through a pipeline network stretching more than 3,500 kilometres. That Hong Kong utility base is the cash engine. But it’s no longer the whole machine.

Starting in 1994, Towngas pushed onto the Chinese mainland, and it didn’t tiptoe. It built out a sprawling footprint that now spans more than 970 projects across 29 provincial regions—city-gas operations, renewable energy solutions, water supply, and urban waste utilisation. In other words, the Victorian streetlamp business has spent the last few decades quietly rewriting itself into a broader “clean energy and infrastructure” platform.

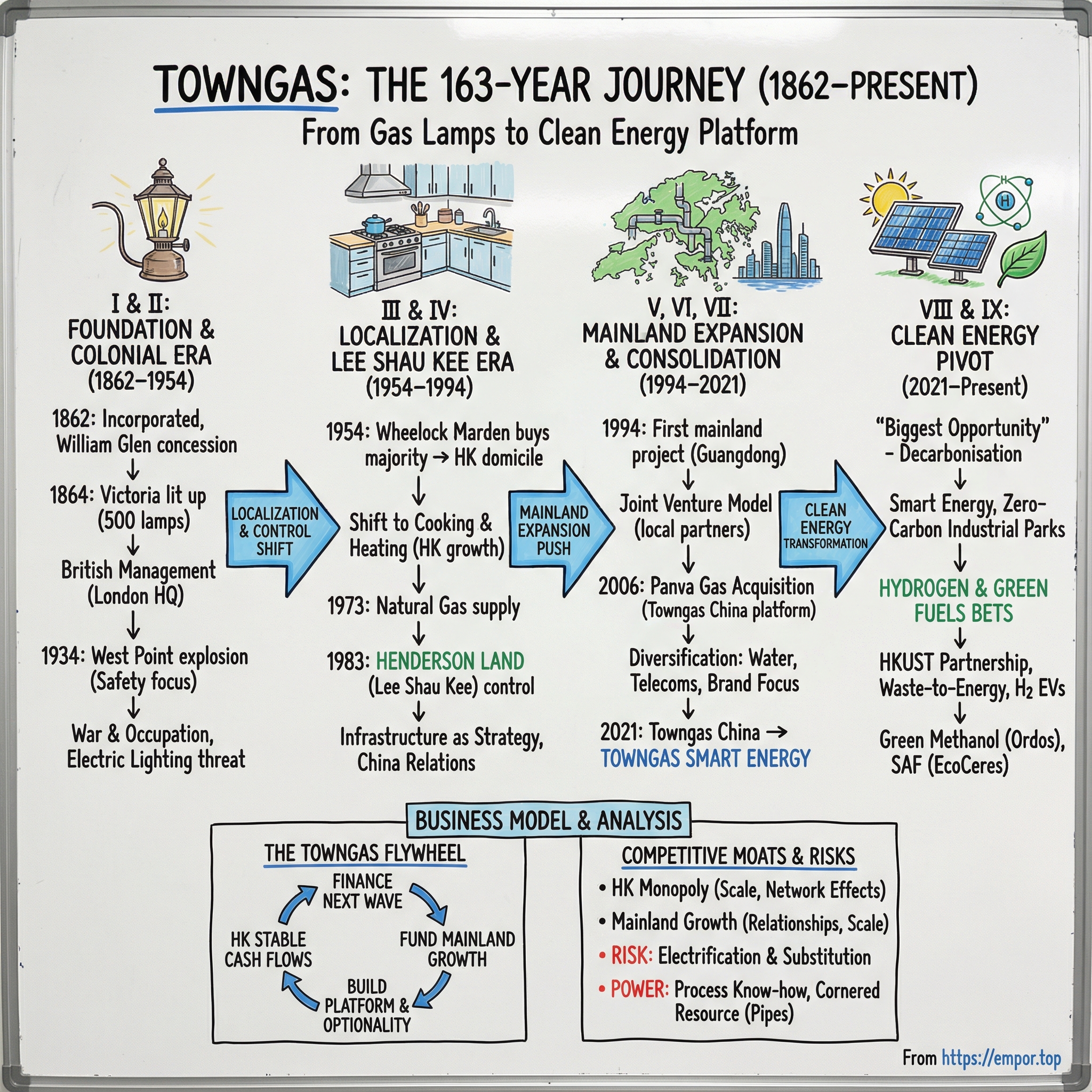

That’s the episode arc: from gas lamps on colonial streets, to a Hong Kong utility monopoly, to a mainland expansion empire, to today’s bets on the next energy stack—hydrogen, green methanol, and sustainable aviation fuel.

We’ll trace the company through four big inflection points: its founding and early years under British management, the crucial shift to local ownership in the 1950s, the aggressive mainland expansion that begins in 1994, and the current green transformation that executives have called “the biggest opportunity in our 160-year history.”

And, because no great Hong Kong business story is complete without a larger-than-life dealmaker, we’ll meet the man who more than anyone reframed Towngas as strategic infrastructure: property tycoon Lee Shau Kee. His rise to chairman in the early 1980s wasn’t just an ownership change—it was a clue to what Towngas could become when viewed not as a commodity supplier, but as a control point in a city’s growth.

This is a story about reinvention. About Hong Kong’s relationship with China. And about what it takes for a company to stay relevant not just for decades, but for centuries. So let’s begin where so many Hong Kong stories begin: on the waterfront.

II. Colonial Origins: Lighting Up Victoria (1862–1954)

The Hong Kong William Glen stepped into in 1861 was full of tension and contrast. The island had been ceded to Britain barely twenty years earlier, and Victoria City was already trying to look like a serious imperial trading hub: busy waterfront offices, government buildings, a hotel for visiting merchants—commerce on full display.

But when night fell, the city still ran on darkness. London had gas streetlighting by 1812. By the 1860s, gaslight was a symbol of modern life across Europe and North America. Hong Kong, for all its ambition, was still relying on oil lamps and candles.

Glen wasn’t a gas man. He was an opportunity man. He went to Governor Sir Hercules Robinson with a pitch: give me the right to supply manufactured gas to Victoria, and I’ll bring the colony into the modern era. The government liked the optics—and the practical benefits—of a better-lit city. The concession was granted, and on May 31, 1862, The Hong Kong and China Gas Company was incorporated.

The first generating plant went up at West Point, right on the waterfront: a coal-fired works that, for its time and place, was extraordinary. It produced 120,000 cubic feet of gas per day. By modern standards that’s tiny. In Asia in the 1860s, it was a technological leap—effectively the first manufactured gas plant on the continent.

On December 3, 1864, Hong Kong lit up. Around fifteen miles of mains fed roughly 500 lamps across Victoria City. Government offices. Army barracks. Jardine’s premises. The Hong Kong Dispensary. The Hong Kong Hotel. Places that set the rhythm of colonial life suddenly had reliable light after sunset. For residents used to tropical nights closing in fast, it must have felt like the city had extended its waking hours.

From the start, though, Towngas was Hong Kong in geography and Britain in management. The board set up in London and ran the company from there—hiring staff, making decisions, setting direction. For the next ninety years, the business was managed directly from Britain: shareholders mostly British, strategy transmitted from an office thousands of miles away, and local teams executing orders on the ground.

That model brought real benefits. Britain had deep expertise in manufactured gas, and operational know-how mattered in a business where mistakes could be catastrophic. But it also carried a cost: distance. It encouraged a kind of imperial detachment—treating Hong Kong as a faraway market to serve, rather than a community whose needs were changing fast.

Still, the company grew with the city. A major step came in 1892, when Towngas established the Jordan Road Works in Kowloon. That move didn’t just add capacity—it pushed the business across the harbour and expanded the network outward with the city’s growth. Kowloon was developing quickly, and Towngas had positioned itself to serve the whole metropolitan area, not just the colonial core on the island.

By the early 20th century, there were more than 2,000 street gas lamps in Hong Kong, and Towngas had become part of the city’s basic operating system. But even while gaslight was everywhere, its replacement had already arrived on the world stage. Electric lighting was spreading, and it was only a matter of time before it rewired Hong Kong too.

Then came a brutal reminder of what this business really was: not romantic streetlamps, but heavy industrial chemistry. On May 14, 1934, a gasometer at the West Point plant exploded. Forty-two people were killed, many more injured, and five surrounding buildings were gutted. It was one of the worst industrial disasters in Hong Kong’s history—and it landed right on Towngas’s doorstep.

The explosion forced a reckoning. Safety couldn’t be an afterthought; it was the business. The company invested in improvements and worked to rebuild trust, but the incident underlined a permanent truth about gas utilities: they demand constant vigilance, constant maintenance, and constant upgrading. The risks never go away—you just manage them, every day.

And as if the 1930s weren’t enough, the 1940s brought the Japanese occupation from 1941 to 1945, severely disrupting operations. When the war ended, Hong Kong entered a new phase of reconstruction and acceleration—and in that new Hong Kong, electric lighting wasn’t a novelty. It was becoming the default. Gas was losing the very job it had been invented to do.

So the existential question arrived, quietly but relentlessly: what happens to a gas lighting company when the city no longer needs gas for light?

The answer wouldn’t be a single invention or a sudden pivot. It would begin with something more fundamental: who controlled the company, and where the company was truly run. By the early 1950s, the limits of management-from-London were hard to ignore. Towngas needed local relationships, local knowledge, and local capital to navigate the post-war world.

The ninety-year era of British control was nearing its end.

III. Localization & the Wheelock Marden Era (1954–1982)

In 1954, Towngas’s center of gravity finally shifted to where the pipes actually were.

George Marden of Wheelock and Marden Company Limited, a locally rooted trading firm, acquired a majority stake in The Hong Kong and China Gas Company. On paper it was an ownership change. In practice, it was Hong Kong taking control of one of its most essential pieces of infrastructure.

With Wheelock Marden in charge, the company’s registered domicile moved from the United Kingdom to Hong Kong. That meant decisions no longer had to be made from an office in London by people trying to manage a city they didn’t live in. Towngas could now be run by executives who understood Hong Kong’s politics, its pace, and its very particular demands—without waiting for instructions to cross half the world.

The timing couldn’t have been better. The 1950s and 1960s were years of population surge and breakneck urban growth, fueled in large part by refugees fleeing the Communist revolution on the mainland. The colonial government responded with massive public housing programs, and the city’s needs shifted fast: not just lighting streets, but powering everyday life inside dense high-rises.

For Towngas, that was both threat and opportunity. Electric lighting had already begun to erase the business the company was born to serve. For nearly a century, gas lamps had been part of the city’s nightly rhythm—at one point, more than 2,000 of them. But Towngas didn’t cling to nostalgia. It reframed the product. Gas wasn’t just for lighting anymore; it was for cooking and heating—for how people lived.

That mattered in Hong Kong. Cantonese cooking depends on high heat and immediate control. Gas burners delivered that responsiveness in a way electric stoves couldn’t match at the time. As the city moved indoors and upward, Towngas found a new role: a utility embedded in daily habit, not public spectacle.

In 1973, the company made another strategic move and entered the natural gas supply sector. It was an early step toward cleaner feedstocks and a less coal-dependent system—an idea that would only grow more important as Hong Kong urbanized and air quality became harder to ignore.

Then came scale. In 1975, Towngas partnered with the Hong Kong Housing Authority to extend gas service into new public housing estates across the Kowloon peninsula. This wasn’t boutique expansion. It was the company wiring itself into the infrastructure of modern Hong Kong—building into the housing blocks that were reshaping the skyline and absorbing millions of new residents.

By 1980, Towngas had grown to 170,000 connections. The lighting business might have been fading, but the company had rebuilt itself into something sturdier: a household utility with real momentum.

Still, the Wheelock Marden era was nearing its end. Towngas had local control and operational competence—but the next chapter would demand more: more capital, a bolder strategy, and an ability to navigate Hong Kong’s increasingly intertwined future with mainland China.

In 1982, Towngas completed the formal transfer of its corporate registration from England to Hong Kong, becoming, in legal form as well as in reality, a Hong Kong company for the first time in its 120-year history. It wasn’t just administrative cleanup. It was a staging move.

Because the buyer who would define the next era was already circling—a property tycoon from Guangdong with a very different view of what a gas company could be.

IV. The Lee Shau Kee Era Begins: Henderson Takes Control (1982–1994)

If Towngas’s shift to local control in the 1950s was about operational reality, what happened next was about strategic imagination. To understand why Towngas changed shape in the 1980s, you have to understand the man who came to chair it: Lee Shau Kee.

Lee’s story is almost a template for modern Hong Kong. His father ran a money-changing business in Guangzhou, the commercial engine of southern China. In 1948, as the Communist revolution moved toward victory, the family made a decisive bet on uncertainty: Lee, just twenty, was sent to Hong Kong with half of the family’s assets. It wasn’t a fresh start so much as an insurance policy—make sure there’s a foothold on the other side, whatever happens on the mainland.

Lee arrived with capital, yes, but more importantly with a merchant’s instincts. By 1958 he was in real estate, reading Hong Kong the way the best entrepreneurs do: as a place where land was scarce, demand was relentless, and property would become the ultimate store of value. By 1972, he committed fully to that path. In 1973, he founded Henderson Land Development.

Henderson wasn’t built on splashy statements. Lee’s approach was methodical: accumulate land in developing areas, wait for the city to grow into it, then build for the rising middle class. He kept a low profile, avoided the social circuit, and reinvested constantly. By the early 1980s, he was firmly in the top tier of Hong Kong’s business elite.

But Lee didn’t just want to own buildings. He wanted to own the systems that made the city work.

In a dense, infrastructure-dependent place like Hong Kong, the most strategically powerful companies aren’t always the most glamorous. Utilities sit at the center of everything: every new tower needs connections, every household becomes a recurring customer, and the cash flows are steady in a way property development rarely is. Control the pipes, and you don’t just collect revenue—you see the city’s growth patterns before everyone else.

That’s why, in 1983, Henderson Land acquired the controlling stake in Towngas, and Lee became chairman. To some, it looked odd. Why would a property developer want a gas company?

Because the deal wasn’t only about selling gas. It was about sitting at the junction point of every new development in Hong Kong—Henderson’s projects, and everyone else’s. It was about being woven into the approvals, planning, and build-out that accompanied urban growth. It was also, bluntly, about assets. Towngas controlled valuable land, including major sites at Tai Po and Ma Tau Kok. As Hong Kong grew richer and denser, that kind of footprint only became more important.

And Towngas wasn’t just a passive holder. The company engaged in property development projects and built meaningful stakes in prime Hong Kong real estate—including a 15% share in the International Finance Centre and a 50% share in Grand Promenade.

Zooming out, Towngas was one piece of a broader Lee Shau Kee machine. Over time, he assembled an empire of seven Hong Kong-listed companies with a combined market value of HK$551 billion, spanning real estate, hotels, piped gas, and even a ferry operation. The connective tissue wasn’t the industry; it was Hong Kong itself—businesses that would benefit from the city’s continued expansion and rising prosperity.

But Lee’s biggest calculation wasn’t about property-cycle economics. It was about geopolitics.

By the early 1980s, the question of Hong Kong’s future had moved from background anxiety to front-page reality. Britain’s lease on the New Territories would expire in 1997, and everyone understood that the colony would return to Chinese sovereignty. The Sino-British Joint Declaration in 1984 formalized the plan: Hong Kong would become a Special Administrative Region, with its capitalist system preserved for fifty years under “one country, two systems.”

For many Hong Kong business leaders, this triggered a scramble—emigrate, diversify, get assets offshore. Lee took another path. He leaned into China. With roots in Guangdong and a deep understanding of mainland business culture, he treated relationships with Chinese officials as an advantage to cultivate, not a risk to flee.

Those relationships mattered. Henderson Investment—the subsidiary that held the Towngas stake—built strong ties with the Chinese government. And when Towngas began looking for its next growth engine, those ties would help turn a daunting frontier into an addressable market.

Because by the early 1990s, the limits of Hong Kong were already visible. Towngas could keep deepening its hold on the city, but Hong Kong had only about 1.7 million households. There’s only so far you can grow inside a mature, compact market—especially as new energy options emerge.

Across the border, though, was the opposite situation: rapidly expanding cities, massive infrastructure needs, and a country beginning a decades-long modernization sprint. The question for Towngas was no longer whether the mainland would matter.

It was when they would go—and how quickly they could scale once they arrived.

V. The Great China Expansion: From Hong Kong Monopoly to Mainland Empire (1994–2006)

In 1994, Towngas finally crossed the border.

It started modestly—one joint venture, one project at a time—but the significance was huge. For a company that had spent more than a century operating inside Hong Kong’s compact geography, this was the opening move of a new playbook: build a second engine on the mainland.

The logic was unavoidable. Back home, Towngas had already connected more than 1.5 million customers—an extraordinary footprint that made it the largest gas supplier in the region. But that same success carried a ceiling. Hong Kong had only around 1.7 million households. When you’re already serving most of the city, “growth” becomes a slow grind: a few new estates, a few new towers, the occasional building switching from LPG to piped gas.

Across the border, it was the opposite problem—infrastructure was lagging demand. The Pearl River Delta was industrializing at warp speed. Cities like Guangzhou, Shenzhen, and Dongguan were swelling into megaregions, pulling in workers and factories and building upward and outward. They needed modern urban systems, fast. And for gas, that meant moving away from scattered, higher-risk propane tanks toward citywide pipeline networks that could safely scale with density.

Towngas didn’t walk into that opportunity alone. Its entry was helped materially by Henderson Investment’s strong relationships with the Chinese government. Lee Shau Kee’s Guangdong roots, his steady cultivation of mainland ties, and his willingness to bet on Hong Kong’s future rather than flee it gave Towngas credibility in a market where credibility often determines access.

In 1996, the expansion began in earnest. Towngas signed a string of agreements across Guangdong—Guangzhou, Fangcun, Shenzhen, Shantou, Dongguan, and Zhuhai—markets chosen not just for size, but for familiarity and connectivity. Proximity to Hong Kong, shared language and culture, and deepening economic integration made Guangdong the natural first frontier. The first ventures in Guangzhou and Fangcun were up and running by the following year.

By the early 2000s, Towngas had enough momentum that it needed dedicated infrastructure just to manage the sprawl. In 2002, it set up Hong Kong & China Gas Investment Limited in Shenzhen to oversee mainland investments. This wasn’t administrative housekeeping. It was Towngas putting a flag in the ground: China was no longer an experiment. It was the strategy.

Then came an important step up in ambition. In 2003, Towngas established its first provincial-grade joint venture in Nanjing, moving beyond city-by-city deals into larger-scale partnerships. That same year, it formed a second provincial-grade joint venture in Wuhan—proof the model could travel beyond the comfortable orbit of Guangdong.

And the model mattered. In China, you couldn’t simply arrive, buy land, and lay pipes. Access required local partners—often municipal governments or state-owned entities that controlled permits, rights-of-way, and regulatory approvals. Towngas brought operating know-how, safety standards, and capital. The local partners brought legitimacy, relationships, and the keys to the market. It was cooperation by necessity—and, when it worked, a powerful scaling mechanism.

Of course, the mainland also came with a different kind of risk. Investors could see the upside instantly: enormous cities, rising living standards, and huge demand for cleaner, more convenient fuel. But they could also see the pitfalls: shifting regulations, uneven enforcement, and the complexity of managing partnerships where incentives don’t always align. Towngas was effectively wagering that its Hong Kong discipline—and its political access—would be enough to operate at scale.

By the mid-2000s, that wager was showing real traction. Towngas had assembled more than 35 mainland projects and was serving millions of connections. But organic growth wasn’t the only way to win this market, and Towngas knew it. China’s gas sector was consolidating fast, and Towngas began looking for a way to jump in size—one acquisition that could compress years of expansion into a single move.

VI. The Panva Gas Acquisition: Doubling Down on China (2006–2007)

2006 opened with a gut-punch in Hong Kong—and closed with a deal that rewired Towngas’s future on the mainland.

On April 11, a gas explosion tore through Wai King Building in Ngau Tau Kok. Two people were killed and nine were injured. For a utility that sells trust as much as fuel, it was the kind of incident that instantly becomes existential: not just a tragedy, but a public referendum on safety.

Towngas’s response showed what kind of operator it had become. The company launched a comprehensive leakage survey across its Hong Kong network. It found and fixed 51 leak sites, identified three corroded pipes, and—most importantly—pushed the fast-forward button on pipe renewal, accelerating the replacement of 150 kilometres of aging medium-pressure ductile iron pipes. It was expensive, disruptive, and unglamorous. It was also the only acceptable answer.

While Hong Kong was absorbing that shock, Towngas was simultaneously finalizing the most consequential mainland move in its history to date: the acquisition of Panva Gas Holdings Limited.

The headline was simple. In 2006, Towngas bought into Panva for about HK$3.23 billion, a transaction that nearly doubled Towngas’s mainland project footprint overnight.

The structure mattered. This wasn’t a straightforward cash buyout. Panva issued roughly 773 million new shares to Towngas at HK$4.18 per share. That gave Towngas about 45% of Panva’s enlarged share capital—enough to become the largest shareholder—while keeping Panva as a separately listed platform. Panva would later be renamed Towngas China Company Limited, but the core idea was already clear: Towngas was building a second listed vehicle purpose-built for China.

Strategically, Panva delivered something Towngas couldn’t replicate quickly through organic expansion: reach. Panva’s portfolio spanned 15 provinces—coverage that would have taken years of negotiating, partnering, and building city by city. With the deal, Towngas’s mainland projects jumped from 35 in 2005 to 60. That’s not incremental growth. That’s a step-change.

And Towngas wasn’t buying Panva just to own more pipes. It wanted Panva to become its acquisition platform going forward—a vehicle that could issue shares, raise debt, and keep consolidating a fragmented market. As more Chinese cities pushed for piped gas networks and smaller distributors looked for stronger owners, Towngas wanted to be the natural consolidator: the operator with Hong Kong-grade standards and a ready-made capital markets instrument to fund roll-ups.

The macro backdrop helped. The Chinese government was actively promoting natural gas as a cleaner alternative to coal, part of a broader campaign to tackle worsening urban air pollution. In other words, Towngas wasn’t just expanding into a big market—it was expanding into a big market with policy tailwinds.

The patience behind the move also fits the Lee Shau Kee playbook. Towngas didn’t sprint into a splashy acquisition the moment it crossed the border in 1994. It spent more than a decade learning how China actually worked—building relationships, proving itself as a partner, and waiting until a target with real scale and strategic utility was available. Panva wasn’t a detour. It was the planned acceleration lane.

Then, in 2007, the ownership picture back in Hong Kong tightened further. On October 3, Henderson Land Development proposed to pay market value to gain control of Towngas, valuing the 39.06% stake held by its subsidiary Henderson Investment at HK$42.86 billion. Whatever ambiguity remained about Towngas’s place in the Lee family constellation was gone: this was infrastructure as an empire asset—steady cash flows at home, and a newly turbocharged expansion engine across China.

VII. The Henderson Consolidation & Modern Restructuring (2007–2021)

After the Panva deal, Towngas stopped looking like a single-purpose gas utility and started to resemble something closer to a full-stack infrastructure company—still anchored by gas, but increasingly surrounded by adjacent businesses in water, telecoms, and property.

Part of that was ambition. Part of it was self-preservation. Piped gas is a great business when you’re the incumbent with the network and the trust. But the long-term direction of travel—electrification, efficiency, decarbonisation—was hard to ignore. If Towngas stayed a one-product company forever, it was signing up to get smaller with time. So it did what great infrastructure operators do: it looked at what it was already good at—building networks, managing complex projects, navigating regulation and rights-of-way—and asked, “Where else can we apply this?”

Some of the answers were almost too obvious.

Back in 2004, Towngas Telecommunications Fixed Network Limited was established, and the company moved into fibre. The trick was physical: Towngas was already opening streets to install and maintain gas mains. If you’re going to dig once, you might as well lay more than one kind of pipe. Running telecoms cables alongside gas infrastructure turned routine maintenance and expansion work into a second business line—another set of recurring revenues riding on the same disruption.

In 2005 came a different kind of utility: water. The company’s first water supply joint venture, Wujiang Hong Kong and China Water Company Limited, pushed Towngas into water treatment and distribution. The rhyme with gas was the point. Water, like gas, rewards scale and reliability. It tends to come with long-lived assets, steady demand, and an operating model built around safety, monitoring, and constant upkeep. Towngas wasn’t learning a new kind of company so much as extending its playbook into a neighboring lane.

But the biggest shift in this era didn’t show up on an org chart. It showed up in how Towngas thought about the thing it sold.

Executives described it as trying to understand the company’s “true purpose.” In plain English: Towngas didn’t want to be treated like an interchangeable commodity supplier. So it went to the people who loved it most—heavy-usage residential customers—and asked a simple question: why gas?

The answer wasn’t “because it’s cheaper” or “because it’s what we’ve always done.” It was because of the experience. Instant heat. Precise control. The confidence to pull off high-heat Chinese cooking techniques. For many households, gas wasn’t just fuel. It was better meals, faster dinners, and a certain feeling of competence in the kitchen.

Once you see that, you can’t unsee it. And Towngas leaned in.

Instead of marketing itself as a utility, it began building a brand around cooking: opening cooking centres, publishing cookbooks, sponsoring culinary programming, and offering higher-end gas appliances. The company wasn’t abandoning its monopoly economics; it was layering something on top of them. It was taking a business that could have drifted toward “lowest price wins” and trying to make it feel differentiated—more like a trusted household partner than a faceless bill.

Meanwhile, on the mainland, the chessboard kept getting bigger. In 2020, Towngas China signed a capital increase agreement with Shanghai Gas and Shenergy Group to acquire a 25 percent stake in Shanghai Gas. This wasn’t just another dot on the map. Shanghai is a marquee market: high-income consumers, sophisticated commercial demand, and enormous symbolic weight as China’s financial centre. A meaningful foothold there signaled how far Towngas’s China platform had come from its first tentative step over the border in 1994.

Then, in 2021, the name changed: Towngas China Company Limited became Towngas Smart Energy Company Limited. It read like branding, but it was also a declaration of intent. The company was telling the market—and telling itself—that “gas distributor” was no longer a sufficient description. The future it was preparing for would include solar, storage, digital energy management, and services that sat alongside pipes rather than inside them.

By the end of this period, Towngas had done two things at once: it had modernised the old business by turning it into a consumer-facing brand, and it had broadened the platform so the company could keep growing even as the world began to move beyond fossil fuels.

And that set up the next chapter—the most ambitious reinvention yet.

VIII. The Clean Energy Pivot: Smart Energy & Carbon Neutrality (2021–Present)

“The carbon neutrality initiatives are the biggest opportunities that this company has ever encountered in its 160 years of history.” When Chief Investment Officer Alan Chan put it that way, he wasn’t offering a marketing line. He was laying down a survival rule. “Our company needs to evolve,” he continued, “otherwise we will be replaced.”

For Towngas, the threat was existential—but not urgent in the way a crisis is urgent. The Hong Kong business still worked. The pipes still ran. The cash still came in. But town gas—synthetic gas produced from naphtha and natural gas—sat on the wrong side of the world’s direction of travel. As governments set tighter emissions targets and “carbon neutrality” moved from aspiration to policy, the long-term trajectory for traditional gas distribution started to look like a slow squeeze.

So the question wasn’t whether Towngas should transform. It was how fast it could do it without breaking what already worked.

The push got a jolt of credibility—and capital—from an unexpected place: private equity. Affinity Equity Partners invested HK$2.80 billion into Towngas China, taking a 13.3% stake in the enlarged company. This wasn’t the classic playbook of squeezing costs and flipping an asset. The point of the money was acceleration: helping Towngas China evolve into an integrated clean energy provider, with a particular focus on rolling out distributed solar photovoltaics.

And Towngas’s ambition here wasn’t incremental. The funding was tied to a plan to deploy HK$60 billion to build and manage 200 zero-carbon industrial parks in mainland China within five years. The bet was based on a blunt reality of how China’s economy is organized: around 2,600 national and provincial-level industrial parks account for roughly 60% of the country’s annual carbon emissions. If you want to decarbonize China at scale, you don’t start with individual households. You start with the places where the factories cluster.

Towngas Smart Energy’s target was to offer smart energy options to around 200 industrial parks by 2025. That meant showing up with an integrated toolkit—solar installations, battery storage, smart grid management, and energy efficiency solutions—and making it work reliably across an enormous, fragmented landscape. In other words: moving from “we distribute gas” to “we help run your entire energy system.”

This pivot also landed during a generational handoff at the top of the Lee empire. Lee Shau Kee stepped down as chairman and managing director of Henderson in May 2019, passing the reins to his sons, Peter Lee Ka-kit and Martin Lee Ka-shing, as joint chairmen and managing directors. Lee later died on a Monday at age 97, leaving behind one of Hong Kong’s great fortunes—and a portfolio of businesses shaped by his trademark patience.

The next generation inherited more than assets. They inherited the hardest strategic question Towngas had faced since electric lighting began killing the gaslamp business: what should a gas company become in a world moving away from fossil fuels? The answer they backed—leaning hard into clean energy, hydrogen, and sustainable fuels—was both a continuation of the family’s long-term mindset and a sharp turn in what that mindset now pointed toward.

Because this wasn’t just a technology shift. It was a business model shift.

The old Towngas world is a regulated utility: stable, predictable, and capped. The smart energy world offers growth, but it brings new risks—technology risk, execution risk, and regulatory risk that can change city by city and province by province. Towngas was betting that what it had built over 160 years—operational discipline, customer relationships, and the ability to navigate China’s on-the-ground realities—would translate into the new energy economy.

For investors, that created a familiar tension. The company was trading some near-term comfort for long-term positioning. The payoff would depend on whether Towngas could pull off a transformation of this size while keeping its core engine humming.

IX. The Hydrogen & Green Fuels Bet (2022–2025)

On paper, hydrogen looks like the kind of future-tech bet you’d expect from a startup, not a 160-year-old utility. But in 2023, in the hallways of the Hong Kong University of Science and Technology, researchers who had spent years working on hydrogen’s hard problems found a partner hiding in plain sight: Towngas.

HKUST and Towngas signed a Memorandum of Understanding to establish Hong Kong’s first hydrogen energy innovation platform—an attempt to fuse academic R&D with real-world operations, and to push hydrogen technologies out of the lab and into commercial use.

Towngas’s edge here wasn’t theoretical. It was already moving hydrogen around Hong Kong every day.

Hydrogen makes up roughly half of the town gas mix Towngas has distributed through its pipeline network for decades. That means the city already has something most places don’t: existing infrastructure, established safety protocols, and a utility with long operational experience handling hydrogen, plus proven methods for extraction and storage. Towngas’s pitch was straightforward: if hydrogen is going to become a serious energy vector, we’re starting several steps ahead.

Then it began turning that advantage into projects people could actually point to.

One early move was a pilot collaboration with Veolia to convert rubbish into energy, using biogas to produce green hydrogen. Hong Kong’s secretary for environment and ecology called it “the first local green hydrogen production demonstration project.” The wording matters: not a full rollout, but a first proof that the concept could work locally.

Towngas also announced plans to build Hong Kong’s first public electric vehicle charging station powered by hydrogen, extracting hydrogen from its existing gas network. It’s a clever bridge strategy—finding a way to deploy hydrogen fuel cell applications before the city has dedicated hydrogen production and distribution built out—and it was framed as part of Hong Kong’s 2050 peak-emissions target.

But Towngas’s boldest move in “new fuels” wasn’t in Hong Kong at all. It was on the mainland, in Ordos, Inner Mongolia—an unexpected place for a clean-fuel milestone. There, Towngas built what it says is the only facility on the Chinese mainland mass-producing ISCC EU-certified green methanol.

That certification is the key that unlocks global customers. ISCC EU is a widely recognized sustainability standard; it’s the kind of credential shippers and airlines need if they want their fuel switch to count toward real carbon reduction targets. Towngas’s Ordos plant uses biomass and municipal waste as feedstock, with an annual capacity of 100,000 tonnes of green methanol.

And methanol, as unsexy as it sounds, hits a real pain point in the energy transition: shipping. Long-haul container ships can’t simply “go battery,” and hydrogen at sea is still early. Methanol, by contrast, can be used in modified diesel engines. If you can produce it sustainably, green methanol becomes one of the most practical near-term options for cutting maritime emissions.

Towngas didn’t stop at production. It launched green methanol bunkering services in Shanghai and Singapore, and signed cooperation agreements with marine fuel traders and bunkering providers across major Asian ports. For a company born lighting Victorian-era streets, becoming part of the fuel supply chain for global shipping is an astonishing leap. But it’s also a familiar pattern: take the core competencies—fuel production, distribution, logistics—and redeploy them into the next market.

Aviation, though, is the even bigger prize.

Hong Kong & China Gas accelerated the overseas expansion of EcoCeres Inc., one of Asia’s largest producers of sustainable aviation fuel. EcoCeres explored entry into markets like the United States and the Middle East, where jet fuel demand is massive and sustainability pressure is rising.

EcoCeres’s Jiangsu plant reached a particularly important benchmark: it became the world’s first ISCC-CORSIA Plus approved SAF processing facility, meeting the International Civil Aviation Organization’s sustainability requirements. In a category where standards determine who can sell to whom, that certification is a passport to serving airlines globally.

All of this reframes the Towngas story yet again. Hydrogen platforms. Waste-to-hydrogen pilots. Hydrogen-powered EV charging. Green methanol for shipping. Sustainable aviation fuel at global certification standards.

The open question, as always, is execution. These are capital-intensive bets with long timelines and demand curves that depend heavily on regulation and corporate decarbonization commitments. Towngas is wagering that policy pressure and market pull will accelerate adoption faster than skeptics expect. If it’s right, this becomes another reinvention chapter—gas lamps to cooking fuel to hydrogen and green fuels. If it’s wrong, it’s a lot of capital chasing markets that arrive later than planned, or don’t arrive at all.

X. Business Model Deep Dive: The Towngas Flywheel

To make sense of everything Towngas is doing today—hydrogen pilots, green methanol, SAF—you have to start with the part of the company that still quietly does what it has always done: Hong Kong. This is the cash engine that funds the rest.

Towngas is the sole supplier of piped gas in Hong Kong, which in practice gives it a functional monopoly. It supplies town gas to roughly 85% of households, plus a wide base of commercial and industrial customers. The remaining homes either rely on LPG—propane cylinders delivered by competitors—or go fully electric. But for cooking, especially the high-heat, fast-control techniques that define Cantonese cuisine, piped gas has remained the default choice.

That position is defended not by clever marketing, but by steel in the ground.

Towngas runs two production plants and serves about 1.8 million households through more than 3,500 kilometres of pipelines. This is the kind of infrastructure moat that’s hard to overstate. Building a competing gas network in one of the world’s densest cities would mean years of disruptive construction, enormous capital, and a regulatory gauntlet that’s effectively insurmountable.

Then there’s supply—another layer of the moat. Towngas imports natural gas from Australia by sea and stores it at the Dapeng LNG terminal in Shenzhen under a 25-year contract. From there, a 34-kilometre submarine pipeline feeds the Tai Po plant. It’s not just a procurement arrangement; it’s cross-border infrastructure that took years to put in place, and it’s not something a would-be competitor can easily copy.

Inside the plants, the company produces town gas by synthesizing it from naphtha and natural gas, creating a hydrogen-rich fuel suited to cooking and heating. That dual-feedstock setup matters: it gives Towngas flexibility to adjust production depending on commodity pricing and availability, instead of being locked into a single input.

Around this Hong Kong core, Towngas has built a much broader portfolio. Today the group spans city gas in both Hong Kong and the mainland, renewable energy solutions, water and environmental services, telecommunications, building services engineering, and newer bets like hydrogen and sustainable fuels.

Scale, however, increasingly lives on the other side of the border. Towngas China, together with its parent Hong Kong & China Gas, serves more than 40 million customers across the mainland—dwarfing the Hong Kong base. The tradeoff is that the mainland business is a tougher arena: margins are lower, competition is heavier, and growth demands far more capital. The upside is obvious too—the addressable market is vastly larger.

Put it all together and you get what you might call the Towngas flywheel: Hong Kong’s stable cash flows fund mainland expansion; mainland scale builds operating experience and a wider platform; that stronger position generates returns and optionality; and those returns finance the next wave of growth. It’s a loop that has been spinning for roughly three decades, turning Towngas from a single-city utility into a regional energy infrastructure company.

This flywheel is the key to evaluating Towngas. Hong Kong provides stability and cash generation. The mainland provides growth. The clean-energy push is the third act—an attempt to stay relevant as the energy system changes. And each piece leans on the others: without Hong Kong, the mainland buildout would require much more external capital; without the mainland, the company’s growth would hit a wall; and without clean-energy positioning, the long-term future becomes harder to defend.

XI. Competitive Analysis: Strategic Moats and Market Position

Zoom out, and Towngas is a company living two different competitive realities at once. In Hong Kong, it’s an entrenched utility with infrastructure that’s almost impossible to copy. On the mainland, it’s a growth player in a crowded, political, and often brutal market.

You can see that clearly through Porter’s Five Forces. And if you prefer Hamilton Helmer’s language of durable “powers,” Towngas has a few that are very real—along with one big vulnerability that keeps getting louder.

Threat of New Entrants: Very Low

In Hong Kong, new entrants are basically a thought experiment. Towngas runs the only piped gas distribution network in the territory. There isn’t a competing set of pipes in the ground, and there’s no practical path for anyone to build one. Replicating more than 3,500 kilometres of pipeline under one of the densest cities on Earth would take immense capital and years of disruption. And even if someone wanted to try, gas distribution is a licensed utility. Hong Kong has little incentive to invite chaos into a system that has delivered reliably for generations.

Mainland China is different. Entry barriers still exist, but they’re not absolute. Access is controlled market by market, usually through franchises and joint ventures, with local governments effectively holding the keys. Towngas has advantages—relationships, a proven operating playbook, and capital—but it’s competing against other well-connected players, including state-owned enterprises that can be formidable in exactly the same arenas where relationships matter most.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers: Moderate

Towngas has done a lot to keep suppliers from having it over a barrel. The 25-year LNG arrangement tied to the Dapeng terminal gives the company meaningful supply security. Just as importantly, Towngas has flexibility in what it turns into town gas: it can use both naphtha and natural gas as feedstock. That optionality matters when commodity prices swing. Add in midstream investments, and the company has more control over its supply chain than a simple “buyer of gas” business would.

Bargaining Power of Buyers: Low

In Hong Kong, residential customers are essentially locked in. Once a building is connected to piped gas, switching isn’t a casual decision. It means changing appliances, reworking internal building systems, and moving to a different fuel logistics model like LPG delivery. With Towngas serving about 85% of households, most residents aren’t really choosing between competing gas providers. They’re choosing whether to stay with gas at all.

Commercial and industrial customers have more leverage, especially larger users. They can negotiate harder, invest in alternatives, or choose buildings with different energy setups. Still, for most businesses, the day-to-day reliability and convenience of piped gas tends to beat the hassle of switching.

Threat of Substitutes: Moderate and Rising

This is the one that matters most over the long run.

Electric cooking and heating have gotten meaningfully better. Induction cooktops now offer control and responsiveness that can feel surprisingly close to gas. And developers increasingly like all-electric designs: fewer moving parts, less maintenance, and simpler building systems.

Towngas has also felt substitution pressure indirectly through competing fuels. In 2015, when oil prices collapsed, LPG prices fell with them, giving propane competitors a temporary cost advantage. It was a reminder that even with a powerful convenience moat, Towngas still lives inside a broader energy market where the relative price and performance of alternatives can shift quickly.

The deeper issue is structural: electrification. As buildings become more energy efficient and electric appliances improve, the classic gas pitch—convenience and cooking performance—gets harder to defend as a default.

Competitive Rivalry: Low in Hong Kong, High on the Mainland

In Hong Kong, Towngas doesn’t face much direct head-to-head rivalry in piped gas. LPG exists, and it competes at the margins, but it can’t match the convenience of an always-on network. The more serious competition is category-level: electricity, not another gas utility.

On the mainland, rivalry is intense. Gas distribution is a contest for franchises, permits, and local partnerships—often fought city by city. Competitors include local state-owned enterprises, other Hong Kong-based operators, and international players. Winning isn’t just about operating well; it’s about relationships, pricing, service quality, and the ability to keep funding growth.

Hamilton Helmer's 7 Powers Analysis

If you translate all of that into “powers,” Towngas has several that are tangible:

Scale Economies: In Hong Kong, scale is the whole game—one network serving the vast majority of households. On the mainland, scale is meaningful too as the customer base grows beyond 40 million, though it’s spread across many markets.

Network Effects: Not in the classic social-network sense. But there’s an ecosystem effect as Towngas layers gas, telecommunications, and building services into the same physical and customer footprint—making it stickier for developers and building managers.

Switching Costs: Very high at the building infrastructure level, and lower at the appliance level—exactly where electrification is chipping away.

Counter-Positioning: The “smart energy” and clean energy push is, in part, a strategic attempt to avoid being trapped as a pure-play gas distributor while the world moves on.

Cornered Resource: In Hong Kong, the pipeline network is a cornered resource in practice: the only existing infrastructure for piped gas distribution.

Process Power: More than 160 years of operational learning in producing and distributing gas safely is real know-how—and it’s hard to copy quickly.

Put it all together, and the picture is clear: Towngas has extraordinary strength in its home market, but it’s fighting on two fronts. Mainland growth is competitive and relationship-driven. And the biggest long-term threat isn’t another gas company—it’s substitution, as electrification steadily improves.

Which brings the story to one strategic question: can Towngas build the next set of moats—through smart energy, hydrogen, and green fuels—before the old ones start to erode?

XII. Bull and Bear Cases: Investor Considerations

The Bull Case

The optimistic case for Towngas is built on three legs: a remarkably durable Hong Kong franchise, a still-growing mainland China platform, and the upside “optionality” of its clean-energy pivot.

Start with Hong Kong. Towngas’s position is about as close to a utility cash engine as you can get: stable demand, a long-established network, and deep regulatory relationships built over more than a century. And gas cooking isn’t just a fuel choice in Hong Kong—it’s a cultural habit. Try telling a Cantonese grandmother to swap her wok burner for an induction cooktop. More practically, there’s also real inertia in the installed base of gas appliances and building systems. Switching doesn’t happen overnight, and it doesn’t happen for free.

Then there’s the mainland. The growth argument is straightforward: China is still urbanizing, and city infrastructure continues to expand. Natural gas penetration remains lower than in many developed markets, and policy has often favored gas as a cleaner alternative to coal. In that context, Towngas’s scale—more than 40 million customer connections—looks less like “mature” and more like “positioned.” It’s already a meaningful player in a market that could ultimately serve vastly more households and businesses.

Finally, the energy transition bets. These initiatives are early and not without risk, but they offer asymmetric upside. If hydrogen becomes commercially important, Towngas isn’t starting from zero: it already has decades of operational experience handling hydrogen as part of its town gas mix, plus infrastructure and safety know-how. If sustainable aviation fuel becomes a true global mandate rather than a niche market, EcoCeres’s certified capacity could become far more valuable than it looks today. In the bull view, Hong Kong’s steady cash flows effectively bankroll a portfolio of transition options.

Layered over all of this is a track record that matters in infrastructure: execution over long periods of time. Towngas has navigated multiple reinventions under the Lee family’s patient, long-term orientation, and the leadership transition to the next generation has so far looked orderly, with the strategic direction intact.

The Bear Case

The bear case is about structural pressure, China risk, and the possibility that the “next Towngas” takes longer—and costs more—than expected.

The first threat is electrification. It’s not theoretical, and it’s moving steadily forward. Each new all-electric building is a customer Towngas never gets. Each retrofit that replaces a gas stove with induction is an installed-base customer quietly walking out the door. Hong Kong’s cooking culture gives Towngas protection, but culture can change. Younger households that grow up with electric appliances may not share the same preference for flame.

The mainland opportunity carries its own set of risks. China can be a fantastic growth market right up until it isn’t. Regulatory shifts can be hard to predict, currency exposure is real, and political relationships—no matter how carefully built—can change fast. The joint-venture model that enables access also adds complexity: shared economics, governance challenges, and partners whose incentives don’t always match Towngas’s. And competition can be brutal, especially from state-owned enterprises that may have advantages in access and capital.

Then there’s the transition portfolio itself. Many of these are capital-intensive bets on technologies that still face scale-up challenges. Hydrogen has worn the “fuel of the future” label for a long time without becoming the fuel of the present. Sustainable aviation fuel has a classic coordination problem: airlines hesitate to commit until supply is dependable, while suppliers hesitate to build until demand is locked in. And the planned HK$60 billion push into zero-carbon industrial parks is a huge capital commitment, with outcomes that could vary widely depending on execution and policy.

Finally, there’s perception risk. The ESG mood around gas has turned sharply negative, and some institutional investors screen out fossil-fuel exposure regardless of transition narratives. If that trend persists, Towngas could face a shrinking pool of eligible shareholders and valuation pressure that lingers even if operations remain solid.

XIII. Key Metrics for Ongoing Monitoring

If you’re tracking Towngas over time, the story isn’t hidden in any single headline. It shows up in a few simple signals that tell you whether the Hong Kong core is holding, whether the China engine is compounding, and whether the “smart energy” pivot is turning into real business.

Hong Kong Customer Connections and Average Consumption: Start with the franchise that pays for everything else. The cleanest read on its health is the number of connected households, plus how much gas those households actually use. Steady connections suggest the installed base is intact. Stable or rising usage suggests gas is still winning where it matters most—in the kitchen. But if connections start drifting down, or if consumption per customer steadily slides, that’s the substitution story in motion: electrification, changing preferences, and new buildings designed to skip gas altogether.

Mainland China Customer Growth and Margin Trends: On the mainland, growth alone isn’t the point—profitable growth is. Watch how quickly Towngas adds customer connections across its network of city projects, and then watch what happens to margins as it scales. The warning sign to look for is a gap opening between revenue growth and profit growth. If the customer count is rising fast but margins keep compressing, that’s usually competition, pricing pressure, or tougher JV economics showing through.

Clean Energy Revenue as Percentage of Total: This is the scoreboard for the reinvention narrative. Towngas can announce hydrogen pilots, green methanol capacity, and SAF certifications all day long. The real question is whether clean energy—renewables, hydrogen-related initiatives, sustainable fuels—becomes a meaningful slice of the pie. If that percentage rises steadily, the pivot is working. If it stays tiny year after year, the “future” may still be more story than substance.

XIV. Conclusion: The Reinvention Imperative

The story of The Hong Kong and China Gas Company is, in a lot of ways, the story of Hong Kong itself: a frontier port that became a global financial center; a British colony that became a Chinese Special Administrative Region; a manufacturing city that remade itself into a services economy. At each turn, the city found a new identity. Its first public utility kept pace.

Towngas has already lived through the death of its original reason to exist. Gas lighting gave way to electricity. Sovereignty shifted. Hong Kong’s household market matured and saturated. And each time, the company found a new job: from lighting streets to powering kitchens, from decisions made in London to leadership rooted in Hong Kong, from a domestic monopoly to a sprawling mainland platform.

Now comes the most fundamental disruption yet: the energy transition. This isn’t just a new competitor or a new geography. It’s a challenge to the premise of the legacy business. Town gas may be convenient and familiar, but it sits uneasily in a world aiming for net zero. In the long run, “burning hydrocarbons” isn’t a growth story. It’s a problem to be solved.

Towngas’s answer has been to push hard into what it believes the next stack will be: hydrogen, green methanol, sustainable aviation fuel, and zero-carbon industrial parks. The ambition is bigger than a portfolio of side projects. It’s an attempt to redraw the company’s identity—from a fuel distributor to an energy solutions provider. Whether it works is the difference between another century of relevance and a case study in a transition mishandled.

What makes this moment especially interesting is how familiar the pattern is. In 1954, local ownership under Wheelock Marden was a bet that Hong Kong’s growth would reward companies embedded in its infrastructure. In 1983, Lee Shau Kee’s takeover was a bet that control of essential networks would be strategically priceless. In 1994, crossing into the mainland was a bet that China’s urban buildout would dwarf anything possible at home. In 2021, accelerating the “smart energy” shift became a bet that decarbonization would reshape demand faster than utilities could ignore.

None of those bets came with certainty. They required patient capital, long time horizons, and a willingness to build for tomorrow even when today was still paying the bills. And in hindsight, they look obvious—precisely because Towngas executed them.

So for investors, and really for anyone watching legacy infrastructure companies stare down energy transition risk, the question narrows to one thing: can Towngas execute one more reinvention?

It has advantages most companies would kill for. The Hong Kong franchise buys time and throws off cash. The mainland footprint provides scale and a proving ground. The leadership handoff appears orderly, and the strategic direction is explicit.

But the hard part remains the same as it always is: turning a direction into outcomes. The energy system of mid-century will not look like today’s, and the clock is real. Towngas’s history says it can adapt. The next chapter will decide whether that history is prologue—or peak.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music