CLP Holdings: Powering Asia-Pacific for 124 Years

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

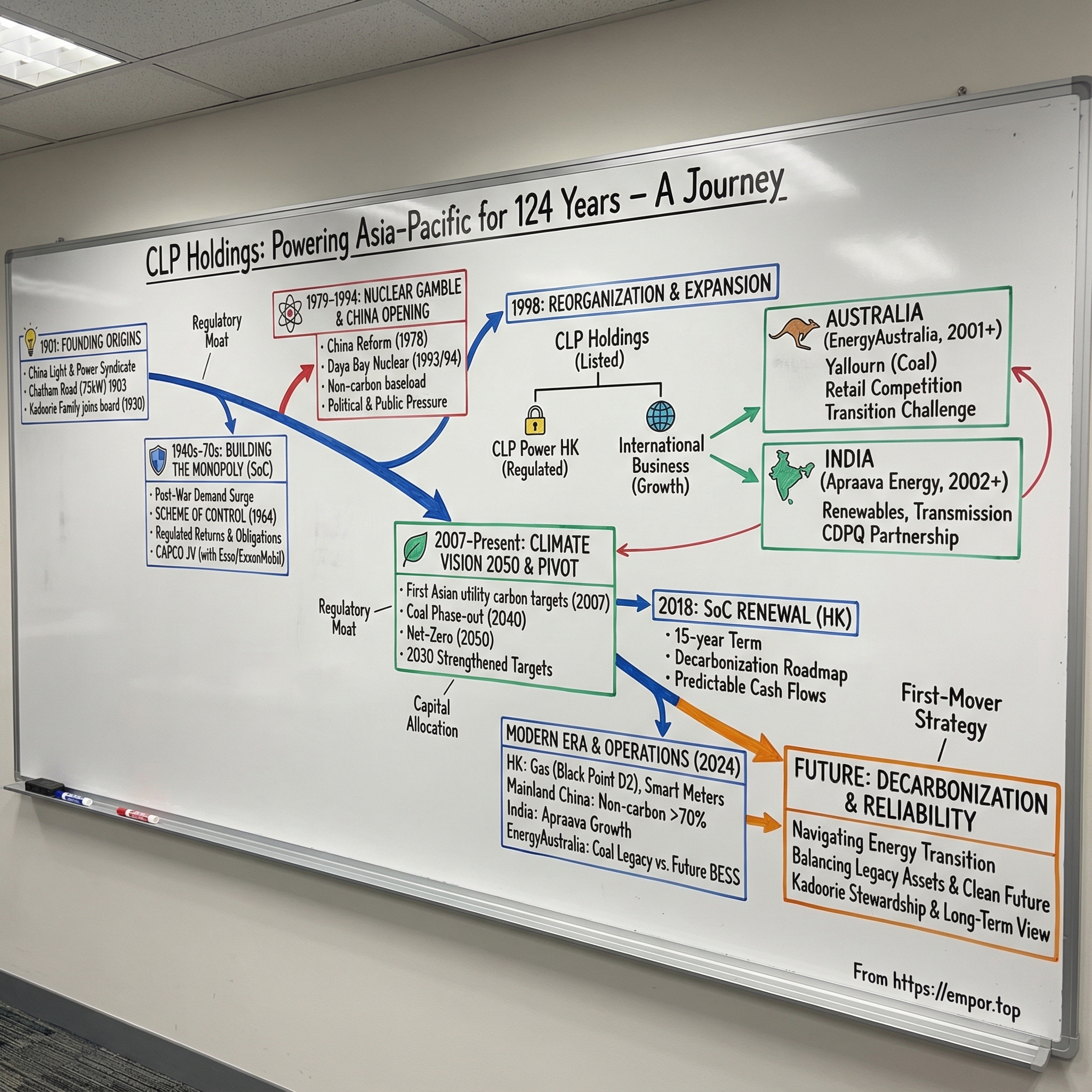

Picture Hong Kong on a humid summer evening in 2024. Kowloon’s neon bleeds into Victoria Harbour. Air conditioners thrum behind glass towers. The MTR slides through tunnels on perfect cadence. It all feels effortless—until you remember that “effortless” electricity is one of the hardest products in the world to deliver: instant, constant, and unforgiving.

Behind that everyday miracle is a company that has kept the lights on for 124 years. Through colonial rule, world wars, and Hong Kong’s handover to China, CLP has sat quietly in the background doing the one job you only notice when it fails. Now it faces the defining challenge of the century: decarbonising an essential system without breaking it.

Today, CLP is one of the largest investor-owned power businesses in Asia-Pacific, with investments across Hong Kong, Mainland China, Australia, India, Taiwan Region and Thailand. But that portfolio label doesn’t capture what’s really remarkable here: this started as a colonial-era electricity syndicate meant to serve a small patch of Kowloon, and it grew into the company that supplies power to more than 80% of Hong Kong’s seven million people.

So the question at the heart of this story is simple—and brutal: how did a turn-of-the-century utility become one of Asia-Pacific’s most significant privately owned power empires, and can it pull off the energy transition while still delivering the reliability its customers take for granted?

The answer comes down to three forces that, together, make CLP unusual.

First is Hong Kong’s regulatory framework: the Scheme of Control. Hong Kong’s electricity sector is privately owned and operated, but it isn’t a free-for-all. The government oversees performance through the Scheme of Control (SoC) Agreement, a bargain that trades strict reliability and investment obligations for a regulated, predictable return. It’s a moat—arguably one of the cleanest utility business models anywhere.

Second is the Kadoorie family. They joined CLP’s board in 1930 and have retained control ever since. That kind of continuity is rare in any industry, but it’s especially powerful in infrastructure, where decisions play out over decades, not quarters.

Third is CLP’s early—and costly—bet on decarbonisation. In 2007, it became the first Asian-based power company to set carbon-intensity reduction targets for its generation portfolio under what it called Climate Vision 2050. This wasn’t a branding exercise. It was a strategic choice that would reshape the company’s assets, its capital allocation, and its risk profile over the next twenty years.

In this article, we’ll follow CLP’s arc from a 75-kilowatt plant on Chatham Road in 1903, through its nuclear gamble at Daya Bay, into its expansion across Australia and India, and into the present-day tension of running legacy coal assets while trying to build a cleaner future. Along the way, we’ll see how regulatory moats are built and defended, how family stewardship can enable long-term value creation, and what it really takes to execute an energy transition when millions of people expect the power to work—every minute of every day.

II. Founding Origins: Electrifying a British Colony (1901–1930)

In 1901, Hong Kong was still a young British colony, still absorbing the shocks of unrest on the mainland, and still figuring out what it wanted to be. Across the world, electricity was turning into the defining infrastructure of modern life. In Hong Kong, it was still a novelty—and a business opportunity.

That year, a group of merchants led by Shewan, Tomes & Co. incorporated a new venture: China Light & Power Company Syndicate. The driving force was Robert G. Shewan, a Scottish merchant who looked across Victoria Harbour to Kowloon and saw the beginning of an industrial and commercial boom that would need power.

The ambition wasn’t just to electrify a corner of Hong Kong. The name itself—China Light & Power—hinted at something bigger: the founders initially intended to supply electricity to Guangzhou, the great trading city up the Pearl River Delta. It was the kind of plan colonial-era businessmen loved: build the wires of modernity now, and ride the growth later.

Reality, as usual, started smaller.

In 1903, the syndicate built its first power station on Chatham Road in Kowloon, with an initial generating capacity of 75 kilowatts. By modern standards, that’s tiny—enough for limited lighting and a handful of commercial loads. But it was a turning point: public electricity supply had arrived, and the idea of “always-on” power was now something Hong Kong could begin to build around.

From day one, the company looked like a miniature version of a modern utility. It generated power, moved it, and sold it—a vertically integrated system built to be reliable within its constraints. At first, those constraints were literal: the service area extended only about three kilometres from the station, focused on nearby industrial and commercial customers clustered around the Kowloon waterfront.

In those early years, electricity was still a premium product—less like a right and more like a marvel. But the shift from private convenience to public infrastructure happened faster than you might expect. By 1919, the company was supplying electricity for street lighting in Kowloon. Street lights didn’t just brighten roads; they changed what the city felt like at night. And they tied the company’s future to the city’s growth in a way that private contracts never could.

Structurally, the business was also maturing. In 1918, the company was restructured and renamed China Light & Power Co. Ltd. And in 1921, it completed the Hok Un Power Station, a bigger, more serious step up in capacity. Through the 1920s and into the 1930s, CLP continued expanding generation and its supply network in Kowloon to meet rising demand.

Then came 1930—the year CLP gained something far more durable than another piece of equipment.

That was when the Kadoorie family joined the board, beginning a stewardship that has endured ever since. Sir Elly Kadoorie, whose family roots traced back to Baghdad and whose business life had taken him through Shanghai and into Hong Kong, represented a different kind of capital. The colonial-era founders were merchants, often thinking in cycles of trade and exit. The Kadoories had built their lives in Asia and invested across finance, property, hotels, banks, and utilities. They weren’t passing through.

Over time, they accumulated a stake in China Light & Power and became its controlling shareholder. More importantly, they brought a temperament that utilities are almost built to reward: patience, discipline, and a willingness to plan for decades.

By the time the 1930s arrived, CLP was no longer just an experiment in electrifying a few blocks near Hung Hom. It was becoming a foundational piece of a growing city—now guided by an owner with the intention, and the time horizon, to build something that could last.

III. Building the Monopoly: The Scheme of Control (1940s–1970s)

On the morning of December 8, 1941, Hong Kong woke to the sound of Japanese aircraft overhead. Eighteen days later, the colony fell. For the next three years and eight months, CLP’s system was largely shut down or operated under Japanese military control. The Kadoories, like much of Hong Kong’s European and Iraqi-Jewish community, endured internment. The company survived, but the illusion of normal life didn’t.

When the war ended, “keeping the lights on” stopped being a business slogan and became a rebuilding project. CLP undertook urgent repairs just to restore supply. And almost immediately, Hong Kong’s electricity problem flipped from scarcity to surge. The post-war years brought a population boom, with refugees from the Chinese Civil War streaming in. Factories multiplied. Apartment blocks climbed. Neon signs turned whole streets into permanent daylight. Every one of those changes meant load on the grid.

CLP struggled to keep up. Industrial growth in Kowloon drove demand faster than generation and networks could expand. Blackouts became common. Tariffs went up. Public frustration spiked—and with it, calls for the government to step in and take the utility over.

That threat—expropriation—became the pressure that forged CLP’s modern identity. In most of Asia, electricity ended up as a state-run service. Hong Kong could easily have gone the same way, and a takeover would have stripped the Kadoories of control and turned CLP into just another government utility.

Instead of resisting regulation, CLP leaned into it. The company proposed limiting its own rate of return and establishing a development fund to finance expansion. It was a counterintuitive move: give up some upside to earn the right to keep operating—and to invest at the scale Hong Kong now demanded.

That idea hardened into policy in 1964, when CLP entered Hong Kong’s first Scheme of Control (SoC) Agreement. It would later be renewed in 1978, 1993, and 2008—evidence of just how well the bargain worked for both sides.

At its core, the Scheme of Control is simple. The government monitors a power company’s operating performance and electricity-related finances. In exchange, the company commits to supplying sufficient, reliable electricity to its service area and meeting required standards, including environmental performance. Customers get a supply that’s meant to be sustainable and affordable. Shareholders get a return considered reasonable relative to the capital invested.

There’s an important nuance here. The Scheme of Control does not give CLP an exclusive franchise, and it doesn’t legally block anyone else from trying to sell power in Kowloon and the New Territories. But electricity isn’t like selling soft drinks. A would-be competitor would need land for generation, rights of way for wires, and the ability to navigate Hong Kong’s regulatory and physical constraints. In theory, competition is allowed. In practice, it’s close to impossible. The outcome is what matters: a privately run, tightly regulated utility with highly predictable economics.

In the same year the first Scheme of Control Agreement was signed, CLP took another crucial step: it created Castle Peak Power Company Limited, or CAPCO. CAPCO was a joint venture that let CLP pursue the kind of large-scale generation Hong Kong now required, while sharing financing needs and risk.

CAPCO was formed with Esso, now ExxonMobil Energy Limited. Together they expanded the Hok Un oil-fired power station, and the partnership brought more than capital. It brought global energy know-how and a deep-pocketed partner willing to fund big infrastructure. Over time, CAPCO became the vehicle through which CLP would build its largest power assets, including the coal-fired Castle Peak Power Station, which opened in 1982 and remains Hong Kong’s largest power plant.

Meanwhile, CLP’s role as essential infrastructure wasn’t limited to dense urban Kowloon. In 1961, it began a Rural Electrification Scheme to bring electricity to remote villages in the New Territories and outlying islands. It was a different kind of expansion—less about immediate profits, more about stitching power into every corner of a fast-modernising society.

Put these pieces together and you get the moat. The Scheme of Control created a system where long-term investment wasn’t optional—it was required—and where the payoff for making those investments was stability. For the Kadoories, it was the perfect utility bargain: accept constraints, deliver reliability, and in return earn regulated, durable returns while staying in control.

IV. The Nuclear Gamble: Daya Bay and China's Opening (1979–1994)

In December 1978, Deng Xiaoping announced China’s “Reform and Opening Up” policy, ending Mao-era isolation and restarting the country’s economic engine. To most Western executives, China still looked distant and unknowable—huge, poor, and politically unpredictable after the Cultural Revolution. But in Hong Kong, watching from just across the border, CLP saw something else: a once-in-a-century opening.

The first move was practical. Following the Open Door Policy, CLP began supplying electricity to Guangdong Province in 1979, after reaching a power interconnection agreement with the Guangdong power grid. It was modest in hardware, enormous in symbolism: CLP was back on the mainland for the first time since the Communist revolution had cut short its early dreams of electrifying Guangzhou.

But Lord Lawrence Kadoorie—CLP’s chairman at the time—wasn’t interested in a small reconnection. He wanted a long-term anchor.

Kadoorie conceived a plan to build a nuclear power station in Guangdong that could supply both Hong Kong and Southern China. In his mind, this wasn’t just an infrastructure project; it was a geopolitical bridge. The plant would deepen economic links with Mainland China, strengthen Hong Kong’s energy security, and—according to Kadoorie’s own “grand strategy”—help preserve British administration of Hong Kong by binding the territory’s prosperity more tightly to stable cross-border cooperation.

The bet was audacious. No foreign company had ever invested in China’s energy sector. Nuclear power, even in developed markets, was politically radioactive—especially after the 1979 Three Mile Island accident in the United States. And the scale was breathtaking: the project carried a US$4 billion price tag, roughly equal to one-third of China’s foreign exchange reserves at the time.

CLP pressed ahead anyway. In 1983, it established a joint venture with Guangdong Nuclear Power for the construction and operation of what became the Daya Bay Nuclear Power Plant. In January 1985, the Guangdong Nuclear Power Joint Venture Co., Ltd. was formed to own and operate the station. CLP created HKNIC as a wholly owned subsidiary to make the investment—giving the Hong Kong company a dedicated vehicle for what was, by any standard, a high-stakes foreign commitment.

Even the financing model had to be invented. CLP and its mainland partner, Guangdong Nuclear Investment Co Ltd. (a subsidiary of China General Nuclear Power Corporation), developed a structure described as “construction through borrowing, repayment through power sales, and operation through joint ownership.” In plain terms: borrow big, sell power to repay, and share long-term ownership so both sides stayed aligned.

The project had political backing at the very top. When Deng Xiaoping met Lord Lawrence Kadoorie the day after the 1985 signing ceremony, Deng called it “a truly remarkable project.”

Then, in 1986, the world changed.

On April 26, Reactor No. 4 at the Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant in Soviet Ukraine exploded. The disaster sent radioactive contamination across Europe and shattered public confidence in nuclear safety worldwide. In Hong Kong, the reaction was immediate and intense. After Chernobyl, concerns surged over building a nuclear plant that many residents considered uncomfortably close to the city.

Opposition organised fast. A petition against Daya Bay gathered one million signatures—about one-fifth of Hong Kong’s population at the time. Prominent politicians including Martin Lee and Szeto Wah voiced objections. More than a hundred community groups pushed the issue into public debate, with criticism focused on environmental risk and on whether Hong Kong residents had any real say in a project whose consequences they would live with.

CLP and its partners didn’t stop. But they understood that engineering alone wouldn’t win legitimacy. The company invested heavily in public communication, launching extensive outreach—seminars, exhibitions, and community education programmes—aimed at explaining nuclear energy and addressing safety concerns.

After nearly a decade of planning, financing, construction, and controversy, the plant began operating. Unit 1 started power operations on August 31, 1993. Unit 2 followed on February 2, 1994. The timeline said as much about the complexity of nuclear as it did about CLP’s endurance.

From the start of operations in 1994, Daya Bay supplied non-carbon electricity to Hong Kong at scale—around a quarter of the city’s needs. The station generates roughly 15 billion kWh a year, with about 80% exported to Hong Kong. Over the past three decades, it has cumulatively supplied more than 320 billion kWh of non-carbon electricity to the city, meeting roughly a quarter of demand and accounting for about one-third of CLP’s fuel mix.

And crucially, the station built a track record that mattered as much as megawatt-hours. In more than 30 years of operation, Daya Bay recorded no level 2 or above Licensing Operational Events (LOEs), and no level 1 LOEs in the past 14 years—an operating record that helped rebuild confidence in nuclear power’s role in a lower-carbon system.

In the end, Daya Bay delivered the full bundle of outcomes Lawrence Kadoorie had been aiming for. It gave Hong Kong stable baseload power that didn’t come with smokestacks. It made CLP a pioneering foreign partner in China’s energy sector. And it proved—public pressure, political complexity, and decade-long timelines included—that CLP could execute the kind of high-consequence infrastructure project that only works when an owner is willing to think in generations, not quarters.

V. The 1998 Reorganization: Creating the Modern CLP Holdings

As the British flag came down over Hong Kong on June 30, 1997, CLP was already working on its next move. The handover closed one chapter, but it clarified the next: under “one country, two systems,” the Scheme of Control would continue. So the real question wasn’t whether CLP could operate in post-1997 Hong Kong. It was whether it could become something bigger than Hong Kong.

The answer required a structural reset.

In 1998, CLP carried out a reorganisation designed for overseas expansion. CLP Holdings Limited was formed and became the new listed company on the Stock Exchange of Hong Kong, replacing China Light and Power Company Limited. The Hong Kong regulated business was placed under CLP Power Hong Kong Limited, a wholly owned subsidiary of CLP Holdings.

The change became official on January 6, 1998, when CLP Holdings Limited was established as the top-tier holding company through a Scheme of Arrangement.

It can sound like corporate housekeeping. It wasn’t. The old China Light & Power Company was effectively welded to Hong Kong’s Scheme of Control—its regulated assets, obligations, and finances sat in one tight bundle. If CLP wanted to invest abroad in competitive, higher-volatility markets, it needed a way to do that without putting its Hong Kong franchise in the line of fire.

The new structure solved that. CLP Power Hong Kong remained the ring-fenced, regulated utility under the Scheme of Control, with clear boundaries for regulators and customers. Above it, CLP Holdings became the platform for everything else—able to buy overseas assets, raise capital, and take on risk without contaminating the core. For investors, it created real optionality. For the Kadoorie family, it kept control cleanly at the top, flowing through to every subsidiary beneath.

Leadership also signaled continuity. The Hon Sir Michael Kadoorie was appointed Chairman of the Board of CLP Holdings on 31 October 1997. With him, the third generation of family stewardship was in place—now with a vehicle built not just to defend a monopoly at home, but to assemble a portfolio across the region.

And the timing couldn’t have been better. The Asian Financial Crisis had just ripped through markets, dragging down asset prices across the region. Utilities and power plants that would have been expensive a year earlier were suddenly available at distressed valuations. CLP, backed by stable Hong Kong cash flows and a conservative balance sheet, was positioned to do what strong operators do in a downturn: buy when others can’t.

VI. Regional Expansion: Australia, India, and the Asia-Pacific Footprint (1996–2014)

CLP didn’t become “Asia-Pacific” overnight. It did it the way utilities usually do when they leave home: one project at a time, one market at a time, stacking capabilities and risk tolerance as it went.

From the late 1990s into the early 2000s, CLP began a deliberate run of deals that pushed it beyond Hong Kong. It entered joint ventures with Taiwan Cement Corporation in 1996, took part ownership of Electricity Generating Public Co Ltd in Thailand in 1998, and then made the move that would define its non-Hong Kong portfolio for the next two decades: Australia, starting with Yallourn Energy in 2001.

Australia: Building EnergyAustralia

Australia was CLP’s biggest leap outside Greater China—and it came with a very different set of rules. Unlike Hong Kong, where the Scheme of Control traded obligations for predictability, Australia ran on competition: generators bid into a wholesale market, and retailers fought for customers.

CLP’s entry point was Yallourn Energy, anchored by the Yallourn Power Station in Victoria’s Latrobe Valley—one of Australia’s largest brown coal generators, and exactly the sort of baseload asset that made sense in a coal-heavy system.

The ownership path was staged. In 2001, PowerGen sold its stake into a joint venture structure that left CLP 80% owner and PowerGen 20%, with the JV holding 90.5% of Yallourn Energy. CLP then moved to full control: it acquired the remaining shares in the Yallourn JV in 2003, and by 2004 it had bought out the minority shareholders and owned 100% of Yallourn.

Then came the next step change. In 2005, TXU Corp sold its Australian assets to Singapore Power, which kept the distribution businesses and on-sold the retail and generation businesses to CLP. In Australia, CLP operated under the name TRUenergy—and quickly became the country’s fifth-largest energy retailer.

The capstone was branding and scale. In 2011, TRUenergy acquired the New South Wales Government’s electricity retail business and the EnergyAustralia name. A year later, TRUenergy rebranded to EnergyAustralia.

This was more than a name change. It signaled CLP’s commitment to being a full participant in a competitive national market—one where returns weren’t regulated into existence, but earned through operations, pricing, and customer growth. From its Melbourne base, EnergyAustralia went on to supply electricity and gas to about 2.44 million customers across the country.

India: A Strategic Frontier

If Australia was CLP’s biggest swing, India was its long game.

In 2002, CLP acquired Gujarat Paguthan Energy Corporation Private Limited. It was a single foothold, but it became the foundation for what would grow into a major foreign-invested power business in India.

Over time, that platform evolved into Apraava Energy: a diversified power company jointly owned by CLP and Caisse de dépôt et placement du Québec (CDPQ), a global investment group. In 2018, CDPQ became a strategic shareholder by acquiring a 40% stake—bringing not just capital, but a powerful external vote of confidence in CLP’s India strategy.

Later, CLP agreed to sell an additional 10% stake in Apraava Energy to CDPQ, taking the partnership to an even 50/50 split. The message was clear: the next phase of growth—especially in low-carbon investment—would be pursued with a long-term, deep-pocketed co-owner.

Apraava expanded from a single-asset company into a business spanning 13 Indian states, with a portfolio of around 3.4 GW of installed capacity across wind and solar projects, a coal-fired supercritical power plant, and power transmission assets.

Consolidating the Hong Kong Position

While CLP was building outward, it was also tightening its grip at home—especially around generation.

In 2014, CLP collaborated with China Southern Power Grid to acquire ExxonMobil’s 60% interest in the generation business. The deal had been announced the year prior: on 19 November 2013, CLP Group and China Southern Power Grid Company (CSG) said they would acquire ExxonMobil’s 60% stake in CAPCO for HK$24 billion. After the transaction, CLP held 70% and CSG held 30%.

CLP also acquired ExxonMobil’s 51% interest in Hong Kong Pumped Storage Development Co. for HK$2 billion, taking CLP to 100% ownership of PSDC, which has contractual rights to use the Guangzhou Pumped Storage Power Station.

Strategically, this did a few things at once. It simplified ownership of critical generation assets, brought a major mainland state-owned enterprise into the partnership structure, and strengthened CLP’s ties into China’s power system. CLP also said the transaction would help it lower emissions toward its 2020 target by enabling more renewable energy imports through CSG’s grid.

VII. The 2018 Scheme of Control Renegotiation: A Pivotal Moment

About once every fifteen years, CLP and the Hong Kong government sit back down at the same table and renegotiate the bargain that underpins the entire system. The Scheme of Control isn’t just a contract. It sets the basic economics of electricity in Hong Kong: what returns the power companies are allowed to earn, what reliability they must deliver, what they’re required to build, and increasingly, how fast they must cut emissions. And because every household and business feels the outcome in its monthly bill, these renewals draw intense scrutiny from consumers, politicians, and environmental groups.

This particular renewal arrived with a ticking clock. Most of Hong Kong’s coal-fired generating units were expected to reach the end of their useful lives over the following decade. At the same time, the Government was committed to improving air quality and combating climate change. Against that backdrop, the new Scheme of Control Agreements were set for 15 years, rather than the previous structure of a 10-year term with a 5-year optional extension. The logic was straightforward: if you’re asking utilities to rebuild the heart of the system—moving from coal toward natural gas and non-fossil fuel sources—you need to give them a long enough runway to plan, invest, and finance it.

The current SoC Agreement came into effect on 1 October 2018, and it runs through 31 December 2033. In practice, it marked a turning point in Hong Kong’s energy policy. CLP was committing to a major transition—retiring coal units, developing gas-fired generation, and increasing imports of cleaner energy from the Mainland—while the Government was providing the regulatory certainty needed to make those investments bankable.

The promise to the public was continuity on the thing that matters most: reliable power. The idea was that Hong Kong’s residents—and its commercial, industrial, and services sectors—could keep counting on stable electricity supply, even as the system changed underneath them. The broader policy goal was also clear. The framework supported Hong Kong’s Climate Action Plan 2030+ (announced in January 2017), which set out a 65% to 70% reduction in carbon intensity by 2030.

And the core feature that makes Hong Kong so unusual remained intact: regulated returns in exchange for regulated obligations. Under the agreement, the permitted return on average net fixed assets in Hong Kong sustains a stable annual cash flow base of roughly HK$8–9 billion. For CLP, that predictable cash flow is more than comfort—it’s the foundation that helps fund investment, not just in Hong Kong, but across the broader portfolio.

That investment requirement is not theoretical. CLP’s Development Plans for 2024–28 included estimated capital expenditure of HK$52.9 billion. It was a reminder of what the Scheme of Control really buys: not just profits, but an enforceable commitment to keep building and upgrading essential infrastructure while maintaining the reliability Hong Kong expects.

Then, even within this long-term framework, the rules continued to evolve. In the 2023 Interim Review, the Government proposed modifications to the SCAs across several areas. After rounds of negotiation, the two power companies agreed to changes including a new Special Tariff Relief Mechanism during an energy crisis, a penalty scheme for large-scale electricity supply interruptions, and greater transparency through enhanced public information disclosure.

For investors, the 2018 renewal did what it needed to do: it reaffirmed the durability of CLP’s regulatory moat. Even with a permitted return that was lower than historical levels, the longer term and clearer investment roadmap offered the kind of visibility that competitive power markets rarely provide. Six decades in, the Scheme of Control still stands as one of the cleanest examples anywhere of privately owned, tightly regulated critical infrastructure—and the system Hong Kong relies on to keep the city running while it decarbonises.

VIII. Climate Vision 2050: The Defining Strategic Pivot (2007–Present)

In 2007, when most Asian power companies were still racing to build coal as fast as permits would allow, CLP chose a different path. It launched Climate Vision 2050 and, in doing so, became the first Asian-based power company to set carbon-intensity reduction targets for its generation portfolio.

This wasn’t a press-release makeover. It was a strategic pivot that forced trade-offs most public-market utilities spend their lives avoiding.

To execute it, CLP’s Board had to take a genuinely long-term view. Early renewable investments weren’t especially attractive on paper. Even with government incentives, the economics often didn’t compete with simply putting more capital into CLP’s existing fossil-fuel fleet. And there was a harder question underneath the spreadsheets: in developing markets where affordability is everything, should a power company prioritise low-cost energy even if that meant leaning on fossil fuels for longer, or push renewables that could initially raise costs for end users?

CLP chose to push forward anyway. The Board affirmed the need to invest in renewable energy and began aligning the business with the priorities laid out in Climate Vision 2050—positioning decarbonisation as part of long-term financial stability, not something separate from it.

The Strategic Evolution

After releasing its first Climate Vision 2050 in 2007, CLP met its decarbonisation targets in both 2010 and 2020, reducing the carbon intensity of its generation portfolio to below 0.8 kg CO2/kWh and 0.6 kg CO2/kWh respectively.

Then came the Paris Agreement, and with it a faster-moving transition than most utilities had planned for. In 2017, CLP conducted a comprehensive review of its targets and committed to an 80% reduction in the Group’s carbon intensity by 2050, compared with 2007 levels.

The 2019 Coal Pledge

In December 2019, CLP announced new actions under its updated Climate Vision 2050 and made its most definitive promise yet: it would not invest in any additional coal-fired generation capacity, and it would progressively phase out all remaining coal assets by 2050.

This wasn’t a marginal reduction plan. It was a commitment to exit coal entirely—an announcement with real consequences for major assets across the portfolio.

The 2021 Acceleration

Next, CLP committed to achieving net-zero greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions across the value chain by 2050. And it brought its coal timetable forward: CLP said it would accelerate plans to phase out coal-fired generation assets by 2040, a decade earlier than previously pledged.

That tightening reflected the direction of travel in the market and in policy. As renewable costs fell and carbon rules hardened, the case for running coal longer became harder to justify.

The 2024 Strengthening

In 2024, CLP strengthened its near-term ambition again. It committed to reducing the GHG emissions intensity of electricity sold to 0.26 kg CO₂e/kWh by 2030, down from the previous target of 0.3 kg CO₂e/kWh. CLP said this would reduce the company’s implied temperature rise from 1.81°C to 1.73°C.

Following an extensive review that concluded in early 2024, CLP published a new edition of Climate Vision 2050 setting out the strengthened 2030 target, along with the key actions it planned to take to decarbonise the business while maintaining an orderly energy transition.

For investors, Climate Vision 2050 is a rare thing in utilities: a voluntary commitment to retire profitable assets and redirect capital into technologies and pathways that, especially in the early years, weren’t the easy financial choice. Whether it ends up looking visionary or expensive will play out over time—but the strategic direction is clear, and CLP has been willing to bind itself to it publicly.

IX. The EnergyAustralia Challenge: Coal Legacy Meets Energy Transition

If Climate Vision 2050 is CLP’s north star, EnergyAustralia is where the map gets muddy. CLP built its Australian platform over two decades, deal by deal. But what it ended up owning was also one of the hardest kinds of assets to decarbonise: a major coal-fired generator in a fully competitive electricity market. EnergyAustralia became both CLP’s most visible headache and its clearest real-world test of whether an orderly transition is possible.

The Yallourn Decision

In 2021, EnergyAustralia announced it would close the Yallourn Power Station in mid-2028—four years earlier than previously indicated—and build a 350 megawatt battery in the Latrobe Valley by the end of 2026. At the time, Yallourn supplied about 20% of Victoria’s electricity.

The decision was framed as a response to two converging realities: falling wholesale electricity prices, and the growing cost and difficulty of keeping ageing coal infrastructure running safely and reliably. In effect, the economics were no longer just about fuel. They were about time—how long you could keep pushing an old machine before it pushes back.

EnergyAustralia also did something unusual: it gave the market seven years’ notice, far more than required. That kind of lead time matters. It gives policy makers, grid planners, and other generators room to prepare for the loss of dispatchable capacity and reduces the risk of sudden shocks.

But the announcement also put a spotlight on the operational challenge of “running it to the finish line.” A study by clean energy consultants Nexa Advisory found that at least one of Yallourn’s four generators was unexpectedly offline 32% of the time. And while Yallourn remained Victoria’s second-biggest source of power—providing nearly a quarter of the state’s electricity—maintenance and safety concerns since 2021 raised pointed questions about reliability. EnergyAustralia was forced to bring forward A$400 million in repairs just to keep the plant operating until its planned closure in 2028.

The Strategic Dilemma

Against that backdrop, CLP began weighing a move that would have been unthinkable when it first expanded into Australia: selling EnergyAustralia.

CLP Holdings has been considering a divestment and has worked with a financial adviser on the proposal. Reports suggested the wholly owned unit could be valued at about US$2 billion.

The context here matters. In 2023, EnergyAustralia was loss-making. CLP also said it was looking for partners to invest in renewable energy, and at the time it had no plans to build new renewable generation itself. That combination—legacy coal exposure, competitive-market volatility, and heavy capital requirements to transition—raises a blunt question for a Hong Kong-regulated utility group: is Australia still the right place to deploy capital?

A sale would look like a retreat, and an implicit admission that CLP’s Australian ambitions didn’t translate into the kind of durable advantage it enjoys in Hong Kong. But it would also release capital and management attention for markets where CLP’s position is structurally stronger.

The Reinvention Plan

Still, EnergyAustralia wasn’t standing still. It made tangible progress on its own transition and operating performance.

EnergyAustralia reported 2024 full-year results of A$115 million NPATF, driven by improved availability and performance from its generation fleet—an increase from a 2023 NPATF of -A$35 million.

On the buildout side, in September 2024, EnergyAustralia secured support under the Federal Government’s Capacity Investment Scheme for the 350MW/1,400MWh Wooreen BESS in Victoria, and it reached financial close in February 2025. In the same month, it also won support under the scheme for the 50MW/200MWh Hallett BESS in South Australia.

So the EnergyAustralia story is still in motion. If CLP can manage Yallourn’s final years, close it on schedule, and replace that capacity while keeping customers and regulators onside, it becomes a proof point that coal-heavy utilities can execute an orderly transition. If it can’t, the likely outcome is divestment—and a reminder that geographic diversification looks very different when you step outside a regulatory moat and into a competitive power market.

X. The Modern Era: 2024 Results and Current Operations

By the time 2024 wrapped, CLP’s story wasn’t just about promises and pilots anymore. The numbers showed a company that had managed to modernise, keep its core stable, and still grow.

CLP Holdings reported strong annual results for 2024, with operating earnings before fair value movements up 8.1% to HK$10,949 million, and total earnings rising to HK$11,742 million after accounting for one-off items that affected comparability.

Revenue for the full year came in at HK$91.0 billion, up 4.4% from 2023. CLP also increased total dividends for 2024 to HK$3.15 per share.

Hong Kong: The Reliable Foundation

Hong Kong is still the anchor. The Scheme of Control continues to do what it was designed to do: produce steady, predictable returns while forcing the company to keep investing in a system that can’t fail.

A visible sign of that transition is the new CCGT D2 gas-fired generation unit at Black Point Power Station. It’s part of the practical work of swapping out retiring coal units for cleaner natural gas, without sacrificing the reliability that Hong Kong customers expect as table stakes.

CLP also finished one of the most important “quiet” upgrades a modern utility can make: data. By the end of 2024, it had deployed more than 1.8 million smart meters, reaching 100% penetration across Hong Kong. The rollout, costing about HK$2 billion over seven years, set CLP up for more sophisticated grid management, future demand-response programs, and a more direct relationship with customers.

Mainland China: The Growth Engine

On the Mainland, CLP has moved far beyond its original bridgehead at Daya Bay. Today it operates a diversified portfolio of more than 50 power generation projects across 15 provinces, autonomous regions, and municipalities.

Just as importantly, the mix has shifted. Non-carbon assets accounted for over 70% of CLP’s equity generation and energy storage capacity on the Mainland as of mid-2025, within a total equity generation and energy storage capacity of 7,978MW. That aligns with the role CLP has positioned itself to play in China’s “dual carbon” trajectory: peak emissions by 2030 and carbon neutrality by 2060.

Nuclear remains part of that toolkit. In 2017, CLP took a 17% stake in Yangjiang Nuclear Power Company Limited, extending the bet it first made with Daya Bay into one of China’s newer nuclear facilities.

India: The Emerging Opportunity

In India, the foothold CLP bought in 2002 has grown into Apraava Energy, now ranked among the country’s top-10 private power producers.

Its portfolio includes around 3.4 GW of installed capacity spanning wind and solar projects, a coal-fired supercritical power plant, and power transmission assets. Beyond what’s operating today, Apraava also had 850 MW of renewable projects (solar and wind) and four greenfield transmission projects under construction.

Structurally, the big enabler is the ownership model: Apraava is a 50/50 joint venture with CDPQ. That partnership brings both capital and long-term alignment as India pushes toward its stated goal of 450 GW of renewable energy by 2030.

XI. Playbook: Business & Investing Lessons

CLP’s 124-year journey isn’t just a history lesson. It’s a playbook for how to build an enduring business in an industry where the product is invisible—right up until it isn’t.

The Power of Regulatory Moats

The Scheme of Control is the clearest expression of this. On paper, it looks like a constraint: CLP’s return is capped at a permitted rate, calculated as a percentage of its fixed assets. But in practice, that cap is the deal. It trades upside for something most businesses would kill for: predictability.

That predictability is what enables long-term planning and investment. You can commit to multi-year grid upgrades and generation replacements because you’re not guessing what next year’s market price will be.

The deeper lesson is how CLP got here. When nationalisation loomed in the 1960s, CLP didn’t just lobby against it. It proposed limiting its own returns and helped shape the framework that would govern it—turning a potentially adversarial relationship into a working partnership with the government.

Family Stewardship at Scale

The Kadoorie family has been CLP’s constant through regimes, wars, and market cycles. Michael Kadoorie, the most prominent current figure, has served as chairman of CLP for decades. Under his leadership, CLP has held onto a rare combination: institutional-grade corporate professionalism with the stability of long-term family stewardship, with a market capitalisation often exceeding $20 billion USD.

Their influence doesn’t show up in splashy headlines. It shows up in steady leadership, careful diversification, and the choice to own assets that are mission-critical to how Hong Kong—and much of the region—functions.

In a world built around quarterly results, the Kadoories represent an older model: build essential infrastructure, protect trust, and optimise for endurance. Their legacy isn’t just measured in balance sheets, but in whether people believe the lights will stay on.

First-Mover Climate Strategy

CLP’s Climate Vision 2050 shows how sustainability can be more than values—it can be strategy. The hard conversations didn’t end with the first set of targets. They’ve continued, driven by a board-level ambition to accelerate decarbonisation and strengthen targets under Climate Vision 2050 at least every five years.

The real takeaway is the willingness to act early, even when it hurt. Investing in renewables when the economics didn’t stack up against existing fossil-fuel stations required conviction that near-term returns were less important than long-term positioning.

Capital Allocation Discipline

Finally, there’s capital allocation—where CLP has quietly been at its best. It used Hong Kong’s predictable cash flows to fund expansion in Australia, India, and China. It brought in partners like CDPQ and China Southern Power Grid when additional capital or capabilities mattered. And it has shown a willingness to consider divestment, like EnergyAustralia, when the strategic fit starts to weaken.

In other words: protect the base, take calculated swings, and don’t let yesterday’s expansion story become tomorrow’s anchor.

XII. Porter's Five Forces & Hamilton's 7 Powers Analysis

After 124 years, CLP’s story can feel like a blur of power stations, joint ventures, and regulatory acronyms. So let’s pull the camera back and ask the simplest business question: what forces shape CLP’s economics, and what durable advantages does it actually have?

Porter's Five Forces:

1. Threat of New Entrants: VERY LOW in Hong Kong / MODERATE-HIGH elsewhere

In Hong Kong, new competition is basically a thought experiment. Electricity supply is dominated by two companies operating under the Scheme of Control with the Hong Kong Government. Between the need for massive capital, scarce land for generation sites, rights-of-way for networks, and the sheer complexity of building critical infrastructure in one of the world’s densest cities, a new entrant can’t realistically show up and take share.

Outside Hong Kong, the guardrails come off. In Australia and India, markets are far more open. New players can build generation, develop renewables, and compete for customers. The threat is still moderated by the advantage incumbents have in scale, operations, and market access—but CLP can’t rely on a regulatory moat the way it can at home.

2. Bargaining Power of Suppliers: MODERATE

CLP is ultimately in the business of converting inputs into reliable electrons—so suppliers matter. Fuel providers (natural gas, coal, uranium) and major equipment manufacturers can influence costs and timelines, especially in periods of tight global supply.

And the transition adds a new layer: batteries, renewable components, and grid technology create different dependencies than traditional thermal plants. Diversification helps, but supplier power doesn’t disappear—it just changes shape.

3. Bargaining Power of Buyers: LOW in Hong Kong / MODERATE elsewhere

In Hong Kong, end customers don’t have a practical alternative provider in CLP’s service territory. That keeps buyer power low.

In Australia, customers can choose among retailers, which increases buyer power. That said, it’s not pure price shopping: switching still takes effort, contracts can be confusing, and many customers simply don’t move unless something forces the issue. So buyer power is real, but it’s not absolute.

4. Threat of Substitutes: LOW (but rising)

For most people and businesses, there’s no real substitute for electricity. But there is a substitute for buying all of it from the grid. Over time, rooftop solar paired with battery storage can reduce dependence on traditional supply, and that’s the long-term substitution threat utilities can’t ignore.

It’s not an overnight disruption—but it’s a slow shift that changes demand patterns, peak load, and how grids are managed.

5. Competitive Rivalry: LOW in Hong Kong / HIGH in Australia

In Hong Kong, the Scheme of Control eliminates the kind of rivalry you see in normal markets. CLP and HEC operate in separate geographic territories, and the business is regulated around performance and investment rather than competitive tactics.

In Australia, rivalry is intense. EnergyAustralia competes with large incumbents like AGL and Origin in both retail and wholesale markets, where margins can swing sharply and operational execution matters every day.

Hamilton's 7 Powers:

1. Scale Economies: STRONG

Electricity is a scale game. Building generation, transmission, and distribution requires huge upfront investment, and the cost per unit improves with size and utilisation. CLP’s Hong Kong system runs at a scale a newcomer simply couldn’t replicate.

2. Network Economies: LIMITED

Electricity networks don’t behave like social networks or software platforms. Each additional customer helps through scale, not because the product becomes meaningfully more valuable to other users. So network effects, in the classic sense, are limited.

3. Counter-Positioning: MODERATE

CLP’s early move into decarbonisation—setting targets in 2007 and shifting capital before it was fashionable—did create an advantage in experience and positioning. But counter-positioning fades as the rest of the industry catches up, and by now most large utilities have some form of transition plan.

4. Switching Costs: VERY HIGH in Hong Kong / MODERATE in Australia

In Hong Kong, switching isn’t really an option within CLP’s service area, so customer switching costs are effectively infinite.

In Australia, customers can switch, but there’s still friction: contracts, billing changes, and the general hassle factor. It’s not prohibitive, but it’s meaningful.

5. Branding: LIMITED

Utilities aren’t luxury goods. Reliability and price do most of the talking, and customers rarely feel “loyal” in the way they might to a consumer brand. Branding can help at the margins—especially in retail competition—but it’s not the core advantage.

6. Cornered Resource: STRONG

CLP’s most defensible assets in Hong Kong are physical and structural: its transmission and distribution network, generation sites, and its access to non-carbon supply through Daya Bay. These aren’t resources you can reproduce quickly, cheaply, or at all given Hong Kong’s constraints.

7. Process Power: MODERATE

Running critical infrastructure well is a craft built over decades—maintenance discipline, grid operations, safety systems, regulatory navigation, and crisis response. CLP has that muscle memory. It’s an advantage, but not an untouchable one: well-capitalised competitors can build similar capabilities over time, especially in markets that allow entry.

Competitive Position Summary

CLP’s competitive position is almost unbeatable in Hong Kong, where the Scheme of Control anchors predictable returns and the infrastructure footprint is effectively irreplaceable. Outside Hong Kong, the game is harder. Australia exposes CLP to full-market competition and the brutal realities of transitioning legacy assets. India and Mainland China offer growth, but require partnerships, local execution, and the patience to operate within complex regulatory environments.

That brings us back to the central tension of the next decade: can CLP decarbonise across a diverse portfolio without losing the reliability, legitimacy, and stable economics that made it one of the region’s premier utility businesses in the first place?

XIII. Key Performance Indicators for Investors

If you’re watching CLP as an investment, it’s easy to get lost in the geography and the acronyms. But most of the story collapses into three investor KPIs—one that tells you how strong the Hong Kong engine is, one that tells you whether the transition is actually happening, and one that tells you how much noise the rest of the portfolio might create.

1. Hong Kong Permitted Return Achievement

In Hong Kong, the Scheme of Control sets the math. CLP is permitted to earn an 8% return on its average net fixed assets. So the questions are straightforward: does CLP consistently achieve that permitted return, and is the asset base expanding?

Because under the SoC, growth in the regulated asset base—largely driven by the Development Plan cycle—doesn’t just represent “spending.” It’s what turns reliability upgrades and decarbonisation capex into higher absolute earnings over time.

2. Carbon Intensity Trajectory

CLP’s transition plan isn’t measured in slogans. It’s measured in carbon intensity. The company has committed to reducing GHG emissions intensity of electricity sold to 0.26 kg CO₂e/kWh by 2030.

This single metric is a reality check on the entire Climate Vision 2050 roadmap. It tells you whether CLP is truly moving toward its coal phase-out by 2040 and its net-zero goal by 2050, or whether progress is slipping. If the trajectory bends the wrong way, it doesn’t just signal operational issues—it raises the risk of tougher regulation and the possibility of stranded assets.

3. EnergyAustralia Profitability

EnergyAustralia is the portfolio’s swing factor. It operates in a competitive market, carries legacy coal exposure, and has historically been a source of volatility.

For investors, the key is whether EnergyAustralia can produce sustained positive earnings through the transition. And if it can’t, the other critical outcome is execution: whether CLP can complete a strategic exit on reasonable terms. Either way, this is the metric that most directly shapes the group’s overall earnings quality—and how credible its capital allocation discipline really is.

XIV. Conclusion: Powering the Next Century

As CLP Holdings nears its 125th anniversary, it’s staring down a challenge more fundamental than any it has faced before. Not war. Not a handover. Not even the nuclear gamble at Daya Bay. This time, it’s the physics and economics of the entire industry shifting at once: from large, centralised fossil-fuel plants toward cleaner and more distributed generation; from customers who simply consume power to customers who can also produce it; from selling a commodity to orchestrating a system.

CLP doesn’t walk into that transition empty-handed. Few companies do.

It has Hong Kong’s Scheme of Control: a rare regulatory bargain that turns reliability and investment obligations into predictable returns and cash flows. It has the Kadoories: patient, long-horizon stewards who can tolerate decisions that don’t look brilliant in the next quarter but matter over the next decade. And it has Climate Vision 2050: not a late pivot, but a strategy CLP put on the table back in 2007, then tightened repeatedly as the world’s expectations moved faster.

But the hard parts don’t go away just because the foundation is strong.

EnergyAustralia remains the clearest stress test: a competitive market, a legacy coal fleet, and an expensive path to reinvention where reliability, customer trust, and capital discipline all have to hold at the same time. On the Mainland, scale brings opportunity, but also the policy and currency risks that come with any long-term infrastructure exposure. And in Hong Kong itself, even the world-class stability of the Scheme of Control lives inside a changing policy reality—one where increased non-carbon imports from the Mainland may reshape how the city thinks about generation, investment, and security of supply.

For long-term investors, that’s what makes CLP so compelling: it’s a company with century-long continuity, durable cash flows, and a publicly stated plan for decarbonisation that it has actually been executing for years. The industry is going to transform either way. The only real question is whether CLP can keep earning the right to be the trusted provider of reliable, affordable, and increasingly clean power—one generation after another.

The Kadoories have effectively tied their family legacy to that outcome. The next decade will show whether CLP can do what it has done for more than a century: adapt, invest, and keep the lights on while the world changes underneath it.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music